Abstract

Introduction: Developing and retaining a high quality medical workforce, especially within low-resource countries has been a world-wide challenge exacerbated by a lack of medical schools, the maldistribution of doctors towards urban practice, health system inequities, and training doctors in tertiary centers rather than in rural communities.

Aim: To describe the impact of socially-accountable health professional education on graduates; specifically: their motivation towards community-based service, preparation for addressing local priority health issues, career choices, and practice location.

Methods: Cross-sectional survey of graduates from two medical schools in the Philippines: the University of Manila-School of Health Sciences (SHS-Palo) and a medical school with a more conventional curriculum.

Results: SHS-Palo graduates had significantly (p < 0.05) more positive attitudes to community service. SHS-Palo graduates were also more likely to work in rural and remote areas (p < 0.001) either at district or provincial hospitals (p = 0.032) or in rural government health services (p < 0.001) as Municipal or Public Health Officers (p < 0.001). Graduates also stayed longer in both their first medical position (p = 0.028) and their current position (p < 0.001).

Conclusions: SHS-Palo medical graduates fulfilled a key aim of their socially-accountable institution to develop a health professional workforce willing and able, and have a commitment to work in underserved rural communties.

Introduction

There is currently a severe global health workforce crisis, with many countries experiencing a critical shortage of health professionals, and/or having a health workforce with an imbalanced skill mix and uneven geographical distribution away from rural and remote areas (WHO Citation2013). Rural populations often face additional health service access barriers due to low socio-economic status or potential ethnic/cultural disadvantage further aggravating the issue (Larkins et al. Citation2013). Developing and retaining an appropriately trained rural medical workforce to overcome this crisis has been a long-standing, world-wide challenge, exacerbated by a lack of medical schools in areas of greatest need and the maldistribution of doctors towards urban practice (WHO Citation2010a).

It has been stated that “in almost all countries, the education of health professionals has failed to overcome dysfunctional and inequitable health systems because of curriculum rigidities, professional silos, static pedagogy, and insufficient adaptation to local contexts…” (Frenk et al. Citation2010). There is evidence that the medical workforce must be trained in public health, community development, and the prevention and treatment of priority local health issues in order to meet context specific health needs and improve population health outcomes (Boelen and Heck Citation1995; WHO Citation2010b; Frenk et al. Citation2010; Talaat and Ladhani Citation2014). The Frenk et al. (Citation2010) and WHO papers further stress that health professional education and health systems reform, driven by evidence acquired through community engagement, is required to ensure the quantity, quality and relevance of health professionals meets local rural health needs.

The Philippines is facing all of these health workforce challenges. The number of medical schools is low per head of population: as of 2016, there were 44 accredited Philippine medical schools and colleges for a population of 102 million. While the Professional Regulation Commission (PRC) licenses an average of 3000 new doctors per year across the Philippines, there is a problem of maldistribution as most physicians prefer to practice in urbanized areas. Forty percent (40%) of the country’s doctors practice in three of the most affluent regions while only 8% practice in regions where the largest proportion of the lowest wealth quintile are living (Domingo Citation2010). Historical statistics of the University of Philippines Manila Alumni Association (UPMAS) in Manila show that 51% of the graduates of the University Philippines College of Medicine chose to practice abroad between 1954 and 1989, and of those who stayed, three quarters of the medical graduates practiced in Metro Manila, leaving only one quarter to practice in the province (Galvez-Tan Citation2013).

In addition, the education of health professionals has historically used conventional Western medicinal curriculae, producing graduates that have been taught and trained to be competent in the health problems of more industrialized countries (Estrada, 1978). One result is that medical and nursing graduates have become so accustomed to using hospital-based, sophisticated health care during their training that they end up being frustrated by the lack of resources in the barrios (villages) (Galvez-Tan Citation2013). The undue emphasis on technical knowledge, proficiency of skills, literacy in technology and narrow specialization prepare students for practice in first world countries rather than in developing countries like the Philippines. Nowhere in the education and training of health professionals by academic institutions in the country is there a deliberate and conscious effort to emphasize public service (Domingo Citation2010).

The study setting

The University of the Philippines Manila-School of Health Sciences (SHS-Palo), a founding member of the Training for Health Equity Network (THEnet) (www.thenetcommunity.org), is located in Leyte, and was established in the Eastern Visayas in 1976 with a ‘social accountability’ mission to help solve the health problems of the local region and to serve the needs of the poorest and most isolated communities where there is a dearth of health manpower. The Eastern Visayas is a Philippines region associated with very poor child, infant and maternal mortality indicators (Philippines Statistic Authority, 1993–1998) compared to most other regions. Graduate tracking records from SHS-Palo show that in the 27 years since the school graduated its first cohort of medical graduates (in 1985), 90% of its medical graduates continue to serve in areas of dire need in the Philippines (SHS Graduate Tracking Data, Office of the College Secretary Citation2012), but there is no other good-quality evidence of the actual impact of SHS-Palo graduates on the local medical workforce, and limited published evidence of the impact of socially accountable training globally (Reeve et al. Citation2016).

Student selection at SHS-Palo preferentially selects students from the lower socio-economic strata and from rural and remote communities as a means for achieving equity in access to health and health professional education in the Eastern Visayas region. Scholarships are provided to students who are nominated by rural communities in need of health workers, and linked to a social contract for recipients to serve that community upon completion of their training. In turn, the community pledges a measure of support for their scholar during training. In accordance with the SHS-Palo philosophy on universal educability, the selection of students has a greater emphasis placed on students’ commitment to serve the community rather than on their previous academic achievement. Likewise, the school waived the National Medical Admission Test (NMAT) as an admission requirement into the medical program. In the Philippines, the NMAT which tests general knowledge and basic sciences is an eligibility requirement for admission to medical school (having a specific cutoff value). However, in 2006, it was adopted as a requirement for scholars nominated by the Department of Health. In 2013, being a regulatory requirement to enroll in a medical school it became a requirement for all students including those from the SHS-Palo program.

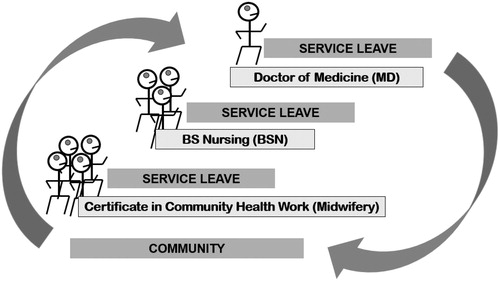

Relevance of training to population and health system needs is an important principle in the development of the SHS-Palo curricula. The context of its curriculum is the Philippine rural community. SHS-Palo health students are trained via an innovative competency-based and community-engaged curriculum that integrates the training of the midwife, nurse and physician in one continuous and sequential step-ladder curriculum (). Throughout the step ladder curriculum at SHS-Palo, from midwifery to nursing and then medicine, students are exposed to a competency-based curriculum focused on the development of knowledge, skills and attitudes appropriate for their future roles and functions in the health care system. Many of the enrollees into the medical program at SHS-Palo are nurse-midwife graduates from the first two levels of the step-ladder curriculum.

To better prepare students for future community practice, a key focus of the SHS-Palo course is to train students in provision of health care, patient communication skills, community planning, community organizing, community development, health education and training skills, health service management, and research. In addition, more than 50% of the students’ learning experience is immersed in service learning – living in and working with communities. Medical students at SHS-Palo spend six months in the community during their 2nd year junior clerkship, and 12 months of community internship in their final year.

During community placements, students live with foster families and work with the community to address health and development challenges. This enables students to develop competencies as health care providers, community development mobilizers, public health program/services managers, researchers, and trainers within the actual context and dynamics of the community. It also fosters community empowerment through students working with the community for the community. For most medical students, this community internship builds on their prior community experiences from midwifery and nursing levels of the step-ladder curriculum.

This is in contrast with conventional medical schools where admission is open and based on previous academic achievement and not linked to community nominations and return service obligations. Training is discipline-based, tertiary hospital based and includes less than a year of community internship.

This study investigates graduate motivation towards community-based service, preparation for addressing local priority health issues, career choices and practice location from SHS-Palo medical school and another Philippines medical school with a more conventional educational approach. Specifically, the study describes the impact of socially-accountable, community-engaged, health professional education (SAHPE) and conventional Western tertiary hospital based curriculum on medical graduates.

This study is part of a series of multi-institutional collaborative research carried out by THEnet and its institutional partners to gather evidence on the outcomes and impact of SAHPE, using THEnet Framework for Social Accountability in Health Workforce Education (http://thenetcommunity.org/social-accountability-framework/; Palsdottir et al. Citation2008; Larkins et al. Citation2013; Ross et al. Citation2014) as a logic model.

Methodology

Study design and protocol

Cross-sectional, self-administered survey of graduates from a SAHPE medical school, the SHS-Palo (13 cohorts from 1989 to 2013), and a medical school with a more conventional curriculum. Inclusion criteria were graduates who had been employed for six or more months since graduation. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the University of the Philippines - Manila Research Ethics Committee (approval number RGAO-REG-2015-CM-F/C021(MED021), the Flinders University Human Research Ethics Committee (number 7042), and the respective Ethics Review Committee of the conventional school included in the study.

Graduates of both schools were identified from graduate records, personal contact, alumni networking between graduates (snowballing), social media, and the Department of Health physician placement data. A variety of methods were then used for survey distribution and completion. Due to geographical and technological barriers, some surveys were administered face-to-face, while some surveys were sent electronically via internet based google forms and Facebook ().

Table 1. Strategies used by the medical schools for contacting their graduates, showing the number of surveys collected via each method.

For each method, an information sheet was provided which included the options for recipients to decline participation or a consent form if they wished to participate in the study. Similarly, follow up and survey collection occurred via phone calls, social media, return post, and personal visits.

Survey questions

The survey sought information on graduates’: background (age, gender, gross family income, schooling), undergraduate NMAT score, financial support during medical school, motivation for studying medicine, motivation for selecting their respective school, intentions at time of graduation (career, rural/urban practice), practice history (attitude to community service, preparedness for practice, current practice discipline, current practice location, current practice facility, length of employment, and specialization). A complete list of the variables as they were considered for statistical analysis is given in and .

Table 2. Undergraduate comparisons for medical schools located in the central Philippines.

Table 3. Postgraduate comparisons for medical schools located in the central Philippines.

Data analysis

A coding template was developed in Microsoft Excel, and all survey data was entered in a uniform format using the coding guide. For the bivariate analysis, the data were later imported into SPSS, release 19. Bivariate relationships between the dependent variable (‘medical graduate’ – conventional school/SHS-Palo school) were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, Pearson’s χ2 tests, and χ2 tests for trend, as appropriate. Throughout the study, a statistical test was considered significant with a p-value <0.05.

Results

For SHS-Palo, a total of 72 out of a possible 121 graduates who met the inclusion criteria, completed the graduate survey, an overall response rate of 59%. For the conventional school, a total of 80 out of a possible 264 graduates completed the graduate survey, an overall response rate of 30%.

Retrospective undergraduate demographics

As students, SHS-Palo medical graduates had significantly lower gross family incomes (p < 0.001), and were more likely to have been supported at medical school by scholarships (57%, p < 0.001), the conventional school graduates were supported by parents (63%) or their partner (35%). The number of graduates at SHS-Palo who were educated in public high schools compared to private high schools was significantly higher (p = 0.044). Entry NMAT scores were lower for SHS-Palo graduates than from the conventional school (p = 0.014), but no difference was found in the post-graduation physician national licensure exam outcomes (p = 0.377) (see and ).

Medical school characteristics

Resounding themes from the questionnaire include selection of the school based on the model of training offered and the commitment to serve in areas of need. For the graduates from the conventional school, the major reason for selecting their school was its close proximity to where they lived (p < 0.001). In contrast, medical graduates from SHS-Palo selected their school based on being awarded a scholarship (p < 0.001), its community-oriented curriculum (p < 0.001), being nominated and supported by their community (p < 0.001) and SHS-Palo’s national and international prestige (p < 0.001).

Intentions at graduation

SHS-Palo medical graduates were more likely to be working in remote villages and small rural towns (p < 0.001) and to undertake primary care disciplines like Family Medicine/General Practice (p = 0.022) and Public Health (p < 0.001) at graduation, while graduates from the more conventional school were more likely to be planning to specialize in Surgery (p = 0.015), Obstetrics and Gynecology (p = 0.034), and Adult Internal Medicine (p < 0.001).

Attitudes to community service and preparedness for practice

Medical graduates from SHS-Palo were more likely to ‘strongly agree’ that: community physicians should cater holistically for the needs of the community (p < 0.001); community healthcare entails partnership with other stakeholders (p < 0.001); community service is both a duty and an obligation for health professionals (p < 0.001); healthcare requires prioritizing community health needs (p < 0.001); community healthcare should promote health equity (p < 0.001); community work provides clinicians the opportunity to perform important healthcare skills (p < 0.001); community work provides clinicians the opportunity to perform varied skills (p < 0.001); rural communities need more help from clinicians than urban (p = 0.002); and, working in the community can make an impact on population health outcomes (p = 0.001).

SHS-Palo medical graduates were more likely to ‘strongly agree’ that their training prepared them well to practice with the following skills: clinical (p = 0.020); readiness to work in first week of internship (p = 0.005); communication (p = 0.002); critical thinking/clinical decision-making (p = 0.006); problem-solving (p < 0.001); health education and training (p < 0.001); community planning (p < 0.001); and health service management (p = 0.001).

Postgraduate career and location

Conventional medical school graduates were more likely than SHS-Palo graduates to pursue advanced studies (p = 0.009) and practicing in Adult Internal Medicine (p < 0.001) while SHS-Palo medical graduates were more likely to be currently practicing in Public Health (p < 0.001) and Family Medicine/General Practice.

SHS-Palo graduates were more likely than conventional school graduates to be working in remote villages or small rural towns (p < 0.001) at Government Rural Health Units (p < 0.001) or Health Offices (p = 0.009) as Municipal Health Officers (p < 0.001), and in Government District or Provincial hospitals (p = 0.032), but less likely to be working as Medical Officers (MO level 1–4, Residents or Consultants) (p < 0.001) in Government Regional hospitals (p < 0.001).

Discussion

The SHS-Palo philosophy is that health and education are a universal birthright regardless of economic or ethnic strata, that training in health needs to be relevant to community needs and that communities are capable of developing their own health manpower. The graduates in this study appear to reflect their school philosophy. Study findings show differences in family economic status, high school background, NMAT scores, underlying reasons for choice of medical school and pursuit of medicine, financial support while studying medicine, practice intentions at time of graduation, attitude to community service, preparedness for practice, and practice in rural and public health – all of which fulfill the key social accountable aims and vision of SHS-Palo.

SHS-Palo has been pioneering a model for producing a fit-for-purpose health workforce since its inception in 1976. The model includes equitable student selection from areas of need through community nominations, social contracts for communities to provide support to their scholars and the obligation of the latter to render return service and extensive community engagement. This philosophy, and strategies such as equitable student selection and extended community-based training has resulted in producing a local health workforce with an unmatched retention rate of midwives, nurses and doctors in areas of unmet need.

The equitable student selection with active community involvement, and the social contract with the community ensures student and school values align with community needs, and also confirms the school’s philosophy of universal educability and health as a universal birthright. The comparable performance in the licensure examinations between graduates of the two schools despite lower NMAT scores upon entry for SHS-Palo graduates may be attributed to self-directed learning, planning and organizing skills developed as they progressed through the step-ladder curriculum. Furthermore, the school’s qualitative grading system of passed (P) and needs tutorial (NT) enabled them to focus on learning rather than competing with each other for grades. The constant exposure to the realities of community life develops a certain degree of independence and maturity. Having midwifery and nursing as their undergraduate preparation also helps the medical students develop skills and achieve content mastery.

Differences in practice intention to serve in smaller and more remote communities, as well as actual practice behavior favoring rural and public health, can probably be attributed to several factors: graduates’ rural origin, the strong community orientation during university-based training; the bonds generated at the time of nomination when the community pledges to support their scholar and in turn the scholar commits to render return service; and, the extensive experiential learning that occurs while students are based in communities.

These factors affirm the policy recommendations of the WHO on recruitment of rural origin, orientation to community health needs during training and scholarships for return service as strategies for retention of health workers in rural areas (WHO Citation2010a), while many studies show rural upbringing of physicians to be associated with willingness to engage in rural practice (Grobler et al. Citation2009). The prolonged and extensive experiential community-engaged learning, mostly in students’ internship year, also contribute to why SHS-Palo graduates showed more positive attitudes to community service and health equity, and believe that doctors can improve the population health outcomes of the communities they serve.

Interestingly, SHS-Palo graduates were also more likely to strongly agree that their course prepared them well for clinical practice in their communities. Many studies have found community-based students do at least as well and may develop better clinical skills than students learning in more metropolitan, hospital-based training sites (Satran et al. Citation1993; Worley et al. Citation2000; Esterman et al. Citation2004; Worley et al. Citation2004; Iputo and Kwizera Citation2005; Power et al. Citation2006; Lyon et al. Citation2008; Wilson and Cleland Citation2008; Lenthall et al. Citation2009; McLean et al. Citation2010; Sen Gupta et al. Citation2011). The experiential, community-engaged learning may also account for graduates of SHS-Palo being more likely to be practising in Public Health and in Family Medicine/General Practice.

The underlying foundation to the success of SHS-Palo is strong engagement and participation with the communities it serves, leading to alignment with local health systems that are the largest employer of graduates. This is combined with SHS-Palo’s ability to translate its social accountability mandate into effective educational strategies through developing a value based curriculum aligned with community needs, and a service learning curriculum delivery model embedded in the communities. This appears to result in graduates from SHS-Palo working longer in both their first medical position and their current position, even after their return of service commitments were met.

Retaining doctors in rural communities remains an intractable problem that poses a serious challenge to equitable healthcare delivery both in developed and developing countries (WHO Citation2003; Vanasse et al. Citation2007; Lehmann et al. Citation2008). There are a multiplicity of factors contributing to the challenge of keeping doctors in the community including: personal origin, family and community factors, financial considerations, career development, working and living conditions and a mandatory service requirement (Leonardia et al. Citation2012).

The Philippines has faced similar problems with keeping doctors in under-served areas. As an initial strategy, the Philippines Department of Health (DoH) launched the ‘Doctor to the Barrios’ program in 1993 (Leonardia et al. Citation2012) in response to the shortage of doctors in remote communities by aiming to retain physicians through healthy financial benefits. However, monitoring found only 18% remained after the two years prescribed period of service. The failure of return-to-service programs that rely on financial incentives alone to achieve health worker targets in under-served areas is well recognized internationally (WHO Citation2000; Thaker et al. Citation2008). As a potential educational solution to the problem, the DoH later launched the ‘Pinoy MD’ program in 2006 (The Philippine Star Citation2006).

The Pinoy MD program provides medical students with scholarships with a return-of-service contract for two years for every year of study; the first two years of which are to be spent in remote doctorless municipalities as ‘doctors to the barrios’ (paid by the DoH). After two years, graduates may continue as rural health physicians employed by the local government units or move to become medical officers in district or provincial hospitals. However, retention is not the sole function of healthy financial benefits and scholarship contractual obligations – the willingness of local government units to provide placements and shoulder their salaries, and the skill mix that graduates were trained to perform while in medical school, are also important factors.

This may at least partly explain the success of SHS-Palo in producing graduates for rural and remote community practise, as their graduates are often from lower socio-economic backgrounds and many would require a scholarship to support them through medical school, and are then trained and motivated to work in the community, with the community. It is not known how many SHS-Palo medical graduates have taken up the option of a Pinoy MD scholarship, but as these scholarships are available to all Philippines medical students, the high percentage of SHS-Palo graduates later practising in rural and remote communities would likely be more attributable to their undergraduate skills training and extensive rural community placements. Thus, the SHS-Palo training program’s success and impact is an important finding given the world-wide difficulties in retaining medical staff in rural areas.

Limitations

The major limitation to this study is that it is a single school comparison of the graduate outcomes of the SHS-Palo with that of only one other medical school. The interpretation is therefore limited to the two schools and cannot be used to generalize the graduate outcomes of all other medical schools offering the conventional curricula. Both schools however, have had similar performance and have achieved consistently high scores in the National licensure examinations over recent years.

The alumni tracking and networking process of the SHS-Palo allowed a high proportion of graduate locations to be identified; however, retrieval of completed surveys was difficult because of geographical barriers and poor internet connectivity in rural areas of Eastern Visayas, resulting in only a 59% response rate. The response rate for graduates of the conventional medical school was even lower at 30%, the lack of an established alumni tracking system may have contributed to the low response rate.

Conclusions

This study suggests that SAHPE institutions can produce graduates who have the potential to positively impact the health of the communities they serve through appropriate graduate selection, a curriculum that is designed to achieve the school vision, matching curricular content with population and health system needs, extensive experiential learning opportunities in communities and community support throughout the selection, training and deployment process. The SHS-Palo step ladder is unique in producing a balanced mix of skilled clinicians for their local health system, in addition to addressing retention and the uneven geographical distribution of health workers – all key strategies recommended by the WHO’s Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health.

This study also highlights the importance of evaluating whether SAHPE institutions serve community needs in order to improve the match between health professional education and health service delivery. Subsequent studies in this series will look at the impact of SAHPE graduates on their communities and health services.

This success has significant implications globally for health system development and for SAHPE institutions as agents of innovation and reform. SAHPE institutions can shape and influence their graduates with potentially wide-ranging effects throughout the health system. Lessons learned from the SHS-Palo graduates are important not only for the region but the rest of the world, and provide empirical evidence that health professional education must be informed by community health needs through stronger collaboration between health education, health sectors and local communities.

Notes on contributors

Jusie Lydia J. Siega-Sur, RN, MHPEd, is an Associate Professor and was Dean of the University of the Philippines Manila – School of Health Sciences from 2006 to 2012.

Dr. Torres Woolley, PhD, is the Evaluation Coordinator for the JCU College of Medicine and Dentistry. Torres has been an active researcher for 20 years using both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, and is experienced in a range of research and evaluation methods, analyses and software.

Simone J Ross, MDR, is the Project Manager for the Training for Health Equity Network, and Lecturer in General Practice and Rural Medicine, College of Medicine and Dentistry, James Cook University.

Dr. Carole Reeve, PhD, previously of Flinders University, now at James Cook University, is a rural general practitioner and public health physician involved in health service and education research in rural and remote areas. Her research and teaching interests are around research translation to improve health equity in disadvantaged populations.

Dr. A-J Neusy, DTM&H, is a retired Professor of Medicine at New York University School of Medicine. He cofounded the Training for Health Equity Network (THEnet) in 2008. He is the Senior Director, Research and Programs and a visiting professor in several universities around the world. His work focuses on health workforce and institutional development.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank graduates, colleagues, and community members who participated in this study. Specific thank you to Prof. Helen Gumba, Dr. Rolando Borrinaga, Prof. Angie Camposano, Prof. Evangeline Culas-Pasagui, Dr. Charlie Labarda, Dr. Herman Nicolas and Victor Matthew Sur. Atlantic Philanthopies have funded THEnet for this study through Resources for Health Equity.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Boelen C, Heck J. Defining and Measuring the Social Accountability of Medical Schools 1995; No. WHO/HRH/95.7 Unpublished; Geneva: World Health Organisation; [accessed 2015 Oct 22]. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/59441.

- Domingo E. 2010. Reforms in the health human resource sector in the context of universal health care. ACTA Medica Philippina. 44:43–57.

- Esterman A, Prideaux D, Worley P. 2004. Cohort study of examination performance of undergraduate medical students learning in community settings. BMJ. 328:207–209.

- Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, Fineberg H, Garcia P, Ke Y, Kelley P, et al. 2010. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 376:1923–1958.

- Galvez-Tan JZ. MD, MPH. 2013. Health in the hands of the people: framework and action. Marie Christine G, Semira, MD, editors. Quezon City, Philippines: JZGALVEZTAN Health Associates Inc.

- Grobler L, Marais BJ, Mabunda SA, Marindi PN, Reuter H, Volmink J. 2009. Interventions for increasing the proportion of health professionals practicing in rural and other underserved areas. Cochrane Database Syst Dev. 1:CD005314.

- Iputo JE, Kwizera E. 2005. Problem-based learning improves the academic performance of medical students in South Africa. Med Educ. 39:388–393.

- Larkins S, Preston R, Matte M, Lindemann IC, Samson R, Tandinco FD, Buso D, Ross SJ, Palsdottir B, Neusy AJ, et al. 2013. Measuring social accountability in health professional education: development and international pilot testing of an evaluation framework. Med Teach. 35:32–45.

- Lehmann U, Dieleman M, Martineau T. 2008. Staffing remote rural areas in middle-and-low-income countries: a literature review of attraction and retention. BMC Health Serv Res. 8:19.

- Lenthall S, Wakerman J, Knight S. 2009. The frontline and the ivory tower: a case study of service and professional-driven curriculum. Aust J Rural Health. 17:129–133.

- Leonardia JA, Prytherch H, Ronquillo K, Nodoro RG, Ruppel A. 2012. Assessment of factors influencing retention in the Philippine national rural physicians deployment program. BMC Health Serv Res. 12:41.

- Lyon PM, McLean R, Hyde S, Hendry G. 2008. Students’ perceptions of clinical attachments across rural and metropolitan settings. Assess Eval High Educ. 33:63–73.

- McLean RG, Pallant J, Cunningham C, DeWitt DE. 2010. A multiuniversity evaluation of the rural clinical school experience of Australian medical students. Rural Remote Health. 10:1492.

- Palsdottir B, Neusy A, Reed G. 2008. Building the evidence base: networking innovative socially accountable medical education programs. Educ Health. 8:177.

- Philippine Statistics Authority, Republic of the Philippines. National Demographic and Health Survey. 2013. https://psa.gov.ph/content/national-demographic-and-health-survey-ndhs.

- Power DV, Harris IB, Swentko W, Halaas GW, Benson BJ. 2006. Comparing rural-trained medical students with their peers: performance in a primary care OSCE. Teach Learn Med. 18:196–202.

- Reeve C, Woolley T, Ross SJ, Mohammadi L, Halili S, Cristobal F, Siega-Sur JL, Neusy A-J. 2016. The impact of socially-accountable health professional education: a systematic review of the literature. Med Teach. 39:67–73.

- Ross S, Preston R, Lindemann I, Matte M, Samson R, Tandinco F, Larkins S, Palsdottir B, Neusy A. 2014. The training for health equity network evaluation framework: a pilot study at five health professional schools. Educ Health. 27:116–126.

- Satran L, Harris IB, Allen S, Anderson DC, Poland GA, Miller WL. 1993. Hospital-based versus community-based clinical education: comparing performances and course evaluations by students in their 2nd year paediatrics location. Acad Med. 68:380–382.

- Sen Gupta TK, Hays RB, Kelly G, Buettner P. 2011. Are medical student results affected by allocation to different sites in a dispersed rural medical school? Rural Remote Health. 11:1511.

- SHS Graduate Tracking Data. 2012. Office of the College Secretary. Leyte: SHS-Palo.

- Talaat W, Ladhani Z. 2014. Community based education in health professions: global perspectives. Geneva: WHO.

- Thaker SI, Pathman DE, Mark BA, Ricketts TC. 2008. Service-linked scholarships, loans, and loan repayment programs for nurses in the southeast. J Prof Nurs. 24:122–130.

- The Philippine Star. 2006. 100 med students to compose first batch of 145 “Pinoy MD Wanted” scholars. [accessed 2017 Feb 2]. http://www.philstar.com/headlines/330637/100-med-students-compose-first-batch-%C2%91pinoy-md-wanted%C2%92-scholars.

- The Training for Health Equity Network. Social Accountability Framework. [accessed 2016 Oct 10]. http://thenetcommunity.org/social-accountability-framework/.

- Vanasse A, Ricketts TC, Courteau J, Orzance MG, Ranfolph R, Asghari S. 2007. Long term regional migration patterns of physicians over the course of their active practice careers. Rural Remote Health. 7:812.

- WHO. 2010a. Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention: global policy recommendations. Geneva: WHO.

- WHO. 2010b. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. Geneva: WHO.

- WHO. 2013. Transforming and scaling up health professioanls’ education and training. Geneva: World Health Organisation. [accessed 2017 Feb 2]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/93635/1/9789241506502_eng.pdf.

- WHO. 2003. World Health Report: Shaping the future. [accessed 2017 Feb 2]. http://www.who.int/whr/2003/en/whr03_en.pdf.

- WHO. 2000. World Health Report: Health systems: improving performance. [accessed 2017 Jun 28]. http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/whr00_en.pdf?ua=1.

- Wilson M, Cleland J. 2008. Evidence for the acceptability and academic success of an innovative remote and rural extended placement. Rural Remote Health. 8:960.

- Worley P, Esterman A, Prideaux D. 2004. Cohort study of examination performance of undergraduate medical students learning in community settings. BMJ. 328:207–209.

- Worley P, Silagy C, Prideaux D, Newble D, Jones A. 2000. The parallel rural community curriculum: an integrated clinical curriculum based in rural general practice. Med Educ. 34:558–565.