Abstract

Purpose: Interprofessional Education (IPE) may depend for its success not only on cognitive gains of learners, but also on affective and motivational benefits. According to Self-Determination Theory (SDT), a major motivation theory, autonomy (feeling of choice), competence (feeling of capability), and relatedness (feeling of belonging) drive motivation in a way that can improve performance. We investigated which elements of IPE in a clinical ward potentially influence students’ feelings in these three areas.

Methods: We conducted semi-structured interviews with 21 students from medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and physical therapy attending a three-week IPE ward and analyzed the data using a realist approach. Two researchers independently identified meaning units using open coding. Thirteen themes were synthesized. Next, meaning units, expressing autonomy, competence, or relatedness were discerned.

Results: Students appeared motivated for an IPE ward, with its authentic situations making them feel responsible to actively contribute to care plans, by understanding how professions differ in their contributions and analytic approach and by informal contact with other professions, enhanced by a dedicated physical space for team meetings.

Conclusion: Students valued the IPE ward experience and autonomous motivation for IPE was triggered. They mentioned practical ways to incorporate what they learned in future interprofessional collaboration, e.g. in next placements.

Introduction

Interprofessional collaboration is considered necessary for quality of patient care (WHO Citation2010) However, students from several professions in a concurrent placement do not spontaneously learn the perspective, roles and responsibilities of others during regular rotations on a clinical ward. This requires deliberate Interprofessional Education (IPE). Pedagogies and organization of IPE wards (Jakobsen Citation2016) as well as factors hindering and facilitating IPE have been described (Visser et al. Citation2017). How an IPE ward influences students motivation for interprofessional learning and future interprofessional collaboration (IPC), which is relevant to sustain interprofessional collaboration is not known. Our study aimed to investigate whether IPE ward experiences motivate students for (future) interprofessional collaboration.

At University Medical Center Utrecht, an IPE ward was initiated, modeled after an orthopedics IPE ward in Stockholm (Ponzer et al. Citation2004). A key feature of the Stockholm model is a closely supervised team of students with responsibility for the care of preselected patients. These elements generally differ from a regular clerkship, where students are more opportunistically involved with the patients who are assigned to their supervisor. In our setting, medical, nursing, pharmacy, dietetics, and physical therapy students worked with their supervisors on mono-professional and interprofessional learning goals. In such a learning environment, socio-cultural differences as well as individual factors play a role. Our interest was in the motivation of students.

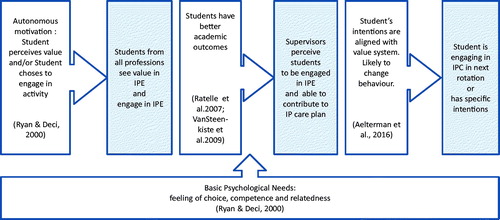

To explore motivational aspects we used Self-Determination Theory (SDT). SDT distinguishes a range of motivation states: from fully extrinsic motivation (doing something because one feels obliged, without alignment with one’s own value system) through partly external and partly internal behavioral regulation (perceiving the value and relevance of the activity, but not finding the activity engaging) to fully intrinsic (doing something because one wants to do it, in full alignment with one’s value system). SDT refers to the latter two states as “autonomous motivation”. Autonomous motivation is increasingly manifested when something (1) has personal value, or (2) is an integral part of the person’s value system, or (3) is in itself engaging. Perceiving value, i.e. integrating an activity into one’s values leads to behavior that aligns with intentions (Ryan and Deci Citation2000). Perceiving value of the activity during the IPE ward experience could lead to intentions to engage in interprofessional collaborations in the future, especially when this value becomes part of one’s self. For autonomous motivation to be present, fulfillment of autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs is required. Aelterman et al. (Citation2016) found an association between perceived value and fulfillment of the basic psychological needs leading to intentions to change behavior. Autonomous motivation, as a dependent variable, is considered to be caused by adequate supervision, curriculum type (e.g. problem based learning), direct patient responsibility, high task value, high perceived competence, and feeling relatedness with peers, teachers, and patients, (Vansteenkiste et al. Citation2005; Kusurkar et al. Citation2011). This is important to realize, because as an independent variable, autonomous motivation is suggested to cause higher study effort, deep learning, better academic performance, and the intention to continue medical studies (Ratelle et al., Citation2007, Vansteenkiste et al. Citation2009). This leads to the hypothesis that if an IPE ward includes elements that support autonomy, competence and relatedness, it can stimulate autonomous motivation among students for IPE, and eventually IPC.

This study has two research questions: Which elements of the IPE ward experience affect feelings of autonomy, competence, and/or relatedness? Which elements hold value for the students, thus influencing their motivation for interprofessional collaboration or interprofessional practice in the future?

Methods

Design

In this exploratory study we interviewed students and supervisors about their experience on an IPE ward. The focus of this paper is on the interviews with the students, using the data from the supervisor interviews for triangulation. Our stance was a realist approach, meaning that we were interested in how participants reacted to the opportunities provided by this IPE ward in this context. Our interest was in their perceptions “of their reality” and next we also looked through the lens of SDT at the potential mechanisms for the change in their behavior (Wong et al. Citation2012).

The study was conducted at University Medical Center Utrecht by researchers with various backgrounds. HEW, RAK, GC, and OTC have medical and educational backgrounds. CLFV has a background in dietetics and nursing education. None of the researchers were involved in the assessment of the students. One of the researchers (HEW) was the project coordinator of the IPE ward program.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO-ERB File number 420).

Setting

From 2015 onwards, final year or near final year students from five professions participated in a three-week full time IPE ward program. A student team comprised of two medical, three nursing, a dietetics, a physical therapy, and a pharmacy student. Students work and meet in a designated meeting room. The student team, under close supervision, are “responsible” for planning, delivering, and evaluating the care for four (preferably low-complexity) patients in one Internal Medicine ward during the day shift. All students have a supervisor from their own profession. Medical and nursing supervisors participate in the interprofessional patientcare meeting and ward rounds each morning. Furthermore, they attend the interprofessional afternoon meeting. Supervisors from other professions attend the interprofessional patient care morning meetings three times a week. In addition, all supervisors can be consulted throughout the day. The medical and nursing students are fulltime on the IPE ward during their shift, the other students combine the IPE ward with assignments at other hospital wards. At the end of each week, the students attend a reflection meeting to discuss team processes, work processes, and practical issues. For medical and nursing students who are on an Internal Medicine rotation in this hospital, the IPE ward is obligatory. Students from other professions are selected by their respective schools on a voluntary basis. The first day of the IPE ward program consists of an IPE team training.

Data collection

All students who spent a clinical placement in the IPE ward between February and July 2015 were invited for an interview at the end of the third week or after their placement. The interviews were semi-structured, based on an interview protocol, developed using the literature and the research aims. It contained questions about the IPE-experience in general, about the learning goals, SDT components, future IPC, and IPE components, respectively which they considered essential. Between March and July 2015, after having supervised an IPE ward, all supervisors were invited for a semi structured interview using a protocol aligned with the students interview protocol.

The first three interviews were conducted and evaluated by HEW and CLFV together to establish alignment. The remaining were conducted by HEW or CLFV individually. The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

We expected saturation of codes after 20 student-interviews using an interview protocol (Guest et al. Citation2006). For practical reasons and transparency, we determined that saturation would be reached when no new information came up in three consecutive interviews (O'Reilly and Parker Citation2013).

We chose Excel® (version 2010) instead of a qualitative data analysis software tool, because this program could be used more easily within our hospital’s IT firewall and also could be used to facilitate exchanges between the two institutions involved. Excel® allowed us to manage the meaning units, themes and categorization needed for thematic analysis, and for text condensation.

Data analysis

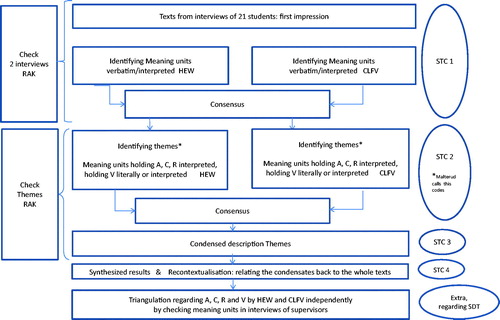

Analysis of the interviews with the students as well as the supervisors was based on systematic text condensation (STC; Malterud Citation2012), which is a pragmatic, systematic, and thematic procedure for cross-case analysis in four steps.

In Step1 text fragments containing relevant information were identified in the interview transcripts by HEW and CLFV independently. These fragments were either used verbatim – if they were clear and concise - or interpreted and summarized by the researchers as literally as possible. This yielded distinct meaning units that were as close to the original interview text as possible (Malterud Citation2012).

In Step 2, meaning units were categorized into themes. In addition, for each meaning unit the researchers independently determined whether it could be interpreted as holding aspects of autonomy, competence, relatedness, and/or value. We defined “value” as having relevance for future practice, derived directly from the interviews in words that displayed personal feelings or from interpretations of the researchers that it held value for the students. Statements, where students referred to organizational aspects or general remarks without expressing their own feelings were not labeled as having value or autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

To enhance the rigor of the study, we sought evidence to support our interpretation of the interviews from different sources (Cook et al. Citation2016). One researcher (RAK) reviewed the coding of two student-interviews and provided input. Secondly, after several student-interviews, two researchers (HEW and CLFV) analyzed what supervisors had observed in students and mentioned in their interviews. This was done to corroborate or contrast information from the students.

In Step 3 the experiences recorded in the meaning units were condensed into a description for each theme by looking at themes and meaning units to find patterns in the data, by a procedure called decontextualization. This step was discussed with the third researcher (RAK) and results were finalized through consensus in the full research team.

Step 4 was recontextualization, checking the fit of the theme description with the complete set of data.

shows a flowchart of the steps in the analysis.

Figure 1. Flowchart analysis and four steps systematic text condensation (STC; Malterud Citation2012). CLFV, HEW, and RAK are the researchers who were involved in this process. On the left hand side and at the bottom the steps to advance the rigor of the study is mentioned. A: autonomy; C: competence; R: relatedness; SDT: Self-Determination Theory.

To seek correspondence with relevant international frameworks, the self-reported IPE results of students are compared with the competency domains defined by the US Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel (IPEC Citation2016).

Results

Demographic characteristics of the participants

Interviews were conducted between February and July 2015. Twenty one students from six teams and 11 supervisors participated in the interviews; see for specifics. Not all student teams had members of all participating professions. Dietetic students participated in only one group, physical therapy students in five groups, and pharmacy students in four groups. One nursing, one pharmacy and one physical therapy student were in an IPE ward team twice on their own initiative and two medical students were in an IPE ward team twice due to a different planning. Some supervisors were involved in two or more IPE ward teams.

Table 1. Demographic distribution of the interview participants.

We followed the four steps of Malterud (Citation2012), in our summary of the results from the analysis of the interview data (see also ).

Step 1 – Despite the different professional perspectives they represent, both researchers (CLFV, HEW), working independently, identified 514 similar meaning units and 170 different ones. Consensus was reached, after discussion, over all 684 units.

Step 2 – The meaning units could be categorized into 13 themes. (See ). Themes found in the interviews with the supervisors were the same as those found in the student interviews, with “Training of supervisors” and “Workload” emerging as additional themes among the supervisors.

Table 2. Systematic text condensation of the student interviewsTable Footnotea.

Step 3 – A condensed text for each theme is given in .

Step 4 – Checking the recontextualization by the two researchers (CLFV, HEW) revealed that the essence of the interviews was represented well in the condensation. This was confirmed by a third researcher (RAK).

Extra step regarding SDT – Meaning units indicating characteristics of the IPE ward that represented autonomy, competence, and relatedness (A, C, R, and also the opposite: neg-ACR) were distinguished in all themes. “Value” was found within all themes and among all professions in roughly the same numbers, except in the theme “Mono-professional”, which we defined as “focus on profession-specific learning goals”.

The 13 themes are reported in . Relating our themes and the learning outcomes to an existing framework, showed that most could be categorized within one of the four competency domains defined by the US Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel (IPEC Citation2016): Values and Ethics, Roles and Responsibilities, and Interprofessional Communication and Team and Teamwork. For example providing students with the structure for patientcare meetings served as a tool to “engage other health professionals - appropriate to the specific care situation - in shared patient-centered problem-solving” (IPEC TT3). However, some of our themes were not explicitly mentioned by the IPEC domains. Therefore, we choose to expand on these themes below, the illustrative meaning units are represented in an quotation style.

Learning environment – We found indications that autonomous motivation was enhanced because the students, as a team, had to come up with a care plan for real patients. “My self-confidence has grown because we made the patient care plans and we talked to patients and their family” (MS7) “… Feeling responsible for the patient care enhanced our clinical reasoning skills and our collaboration” (PT6). Secondly, the coaching style of supervision encouraged students to feel responsibility and perceive autonomy. “This IPE setting stimulated our autonomy – should a supervisor provide a lot of guidance, I would feel I would learn less” (NS9); “The medical and nursing supervisor let us sort out the patient problems ourselves …and provided some guidance - they were coaching, so we really could solve the problems by ourselves” (MS1).

Clinical reasoning – Students from all professions mentioned clinical reasoning. “The IPE ward meant that we could see the clinical reasoning of other disciplines and know what they take into account.” (NS22). The non-medical students experienced that their contributions were valued by the others. “Nurses know more about the patients: MS18; PhaS10; PT20;… so I trusted the nursing student to give me information.” (MS3). To be familiar with the clinical reasoning of other professions helped students to put together “the pieces of the puzzle”. “Now it is easier for me to see their line of thinking and how they come to these interventions” (PhaS24) and influenced the teamwork processes e.g. the realization of nursing students about what timely information medical students needed from them. This insight enabled the nursing students to pro-actively have the appropriate information at hand. “We developed a mutual understanding of the work, work processes, and time pressure” (NS14). Students also learned the aspects physical therapists consider before patients can be discharged from the hospital. “I now realize that we can consult a physical therapist before we decide about a discharge – does the patient need oxygen during physical effort?” (MS18). Sharing clinical reasoning within one’s profession is a practical way to express the perspective of that profession and can bring about a feeling of competence: “I’m capable of thinking in a professional way and I experience competence in the professional content”. Students also experienced that others acknowledged their competence.

Mono-professional learning – One nursing and two medical students indicated that the obligatory IPE experience disadvantaged them in their mono-professional learning.

Structure in the Interprofessional Patientcare meeting – The need for structure was mentioned by most students; finding a good structure was time consuming and thus beyond the competence of most teams in the first week. Therefore, after getting experience of working with three teams, we introduced a framework based on the clinical reasoning steps: current situation →problem inventory → differential diagnosis → care plan → interventions → follow up and summary. Non-medical students preferred to “get a turn” in bringing forward their perception of the problems and solutions in the patient’s situation, because they were hesitant to “interfere with the thinking process of others” (NS22, MS17, PT6). Students from all professions considered clinical reasoning an extra element while learning the “roles and responsibilities” from other professions.

Hierarchy – was experienced by nursing, physical therapy, and pharmacy students in connection to the interaction with medical students. Several times a supervisor was able to morally support the students who perceived lower power and status, resulting in more fruitful communication with the medical students, which can be viewed as creating an autonomy-supportive social environment (Kusurkar and Croiset Citation2015). “I really needed the medical supervisor’s help to challenge the opinion of the medical student” (NS16).

Future IPC – The findings above raise the question if the autonomous motivation, developed during the IPE ward, will affect future practices of the students. Ten participants mentioned how they had either already integrated interprofessional aspects in their performance on the next ward rotation or planned to do so, for example by intending to consult other professions more often, explaining things to other professions, or expressing a lower threshold for doing so. “On my next ward rotation, I will ask a nurse to participate in decision making, to improve the quality of care”(MS13). “By getting acquainted with other professions in a safe learning environment, I perceive less effort to ask questions or to attune the care plan” (NS9). Nurses indicated that they were less hesitant in taking initiatives and contributing to interprofessional communications. Several medical and nursing students expressed a drive to improve interprofessional collaboration. “On the next ward rotation I will suggest to use the IPE ward structure for the patientcare meeting” (MS1) “….[I will] use the structure to give turns to all professions” (NS9). These intentions can be interpreted as an indication of readiness to change the present culture towards a more interprofessional practice. Overall, these explicitly mentioned outcomes of the IPE ward, together with the interpreted meaning units for autonomy, competence, relatedness, and value can be viewed as intermediate endpoints for interprofessional collaboration.

Lens of SDT

Feeling competent was derived from students own professional contributions to the care, as well as from creating care plans interprofessionally. Through the structure for the patientcare meeting, students knew what information to bring, and this fostered “competence and relatedness”. Nursing students were motivated to have the right information at hand. “We have to ask for roles, responsibilities, and perspectives actively to benefit from each other’s observations and anticipate their need for information.”(NS9)

Relating to relevant others was stimulated by the team training (day one), the supervisors from other professions provided help in the team communication and also helped to arrange a weekly team meeting. “Being able to meet informally in our room facilitated our team functioning and getting to know each other personally” (MS18); “Sharing the room meant we could exchange information easier and we became aware of the work and thinking processes of other professions” (PT20); The power of the availability of a meeting room was to foster “informal exchange of information” among students which had a great impact on relatedness.

Corroborating information

From what supervisors stated in the interviews we conclude that: (i) students interacted frequently and had lunch together (R); (ii) students had or developed enough skills to collaborate and displayed these skills (C); (iii) teams were able to apply a given structure for their patientcare meetings and come to in patient care plans (C); (iv) within three weeks the meetings resulted in good consultations within the team (C,R); and (v) students felt a low threshold to ask each other questions (R). In two meaning units a perceived lack of competence was mentioned. A medical supervisor noticed that his students could not pursue interprofessional learning goals when patient care required all their skills and attention (C negative). With these references to the autonomy, competence, and relatedness of students, the supervisors inferred that the IPE ward had offered conditions apparently conducive to the development of autonomous motivation for IPE and interprofessional collaboration in most students.

Discussion

This qualitative study exploring clinical interprofessional education (IPE) from a motivational perspective using SDT suggests that IPE ward experiences (as described in the Section “Setting”) enhance students’ autonomous motivation for interprofessional collaboration (IPC). From the analysis of the interviews with the students and the supervisors, we conclude that it was the overall set-up of the IPE ward that enhanced the autonomy, not simply the responsibility or type of supervision. Within this, different features in the set-up of the IPE ward were more important for different professions. For medical students: the direct supervision, the responsibility that was given, and feedback the students received from supervisors from other professions; For nursing students: the patientcare meeting helped them to clearly understand what information other professions need timely from the nursing profession, which enabled the nursing students to pro-actively have the appropriate information at hand; For the physical therapy students and the pharmacy students: their professional perspective was relatively unknown to the other students. Being able to add their professional insights in the patientcare meeting added to their feeling of competence and autonomy, because they could offer information rather than wait for the question or consultation.

In a recent study on clinical reasoning of nurses and residents, Blondon et al. (Citation2016) identified five dimensions of interprofessional clinical reasoning: diagnostic reasoning, patient management, patient monitoring, communication with patient, and team communication. These dimensions are not unlike the structure introduced in the patientcare meeting in this study. Students from all professions perceived that having to bring their insights in the problems and devise a care plan together was a valuable element in the IPE ward.

In alignment with Aelterman et al. (Citation2016), our findings of elements that caused feelings of choice, competence, and relatedness indicate that students have perceived value in this IPE ward. Supervisors who were able to let the students be in the lead and to stimulate the discussion between the students, created an autonomy-supportive learning environment (Vansteenkiste et al. Citation2005; Kusurkar et al. Citation2011; see for the implications of the IPE ward in the light of SDT).

Figure 2. Implications of the IPE ward. In this figure, the literature regarding Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is depicted in the boxes with an arrow and our finding of this study are given in the boxes without arrows. Fulfilment of the basis psychological needs is pivotal for autonomous motivation, academic outcomes, and intentions leading to behavioral change.

Compared to reports on the Scandinavian IPE wards (e.g. Ericson et al. Citation2012), the effect of our meeting room was more explicitly mentioned by the participants. This created conditions for fulfillment of the basic need of relatedness.

Recommendations

Translating our findings into an advice for an SDT-based design of an IPE ward, we recommend giving students the feeling of responsibility for real patients, within their own profession with authentic assignments and combining professional learning goals with IPE goals. This requires strict supervision from trained supervisors. Students with limited ward experiences will initially focus on mono-professional skills; over time they will feel comfortable training for other competencies, like interprofessional communication. We also recommend a meeting room, where students can work and meet. They can see and hear about the work of other professions and they can also talk about more personal and informal subjects. Learning about the roles and responsibilities of other professions and about their clinical reasoning “to get a complete picture” of a patient is a prominent feature of the IPE ward. Structured interprofessional patientcare meetings, aimed at having all professions contribute and give their perspectives without being afraid to interrupt the thinking processes of other team members, is another key factor for success. A coaching style of supervision encourages students to become active.

Can our findings be of use in designing IPE for larger groups of students? To accommodate more students, the IPE ward design could be multiplied to others disciplines and the duration of the ward could be shortened to one or two weeks which can still provide the most significant experiences. Another option is to apply crucial components of this IPE ward in the general workplace, for example by having students from different professions who are co-located on a ward work together with explicit attention for each other’s perspectives and contributions in addressing patient problems with as much responsibility as possible.

We acknowledge that our recommendations are based on only one center, 21 students and low numbers of students from physical therapy and pharmacy, and none from dietetics. Comparison of our study with those in the review from Jakobsen (Citation2016) seems to indicate that this IPE ward experience achieved similar goals as the Scandinavian initiatives and added new insights into the mechanisms of IPE. The mechanisms found in the student-interviews were corroborated by information from the supervisors, justifying our interpretations (Lincoln and Guba Citation1990). Another limitation concerning the impact of the IPE ward experience is that we only investigated student intentions. That does not necessarily mean they will act accordingly in the future but at present we have no objective data.

Conclusions

Our data seem to indicate that several characteristics of an IPE ward support the fulfillment of needs (autonomy, competence, and relatedness) and the integration of value, thereby promoting autonomous motivation, which results in an intention of several students to seek interprofessional collaboration in the future. This apparent integration of the value that IPC holds for students experiencing an IPE ward, can be perceived as an intermediate learning outcome complementing self-reported outcomes. Viewing an IPE ward from the SDT perspective offers opportunities to strengthen the learning and to generate ideas for new IPE initiatives.

Notes on contributors

Cora L. F. Visser, Msc, is a curriculum developer at VUmc Academy Amsterdam, as well as a PhD student on Interprofessional Education, with a special interest in the affective component of learning.

Rashmi A. Kusurkar, MD, PhD, is an Associate Professor and Head of Research in Education at VUmc School of Medical Sciences, Amsterdam.

Gerda Croiset, MD, PhD, is a Professor of Medical Education and Director of VUmc School of Medical Sciences, Amsterdam.

Olle ten Cate, PhD, is a Professor of Medical Education and Scientific Director Education and Senior Scientist at the Center for Research and Development of Education at University Medical Center Utrecht.

Hendrika E. Westerveld, MD, PhD, is an Associate Professor of Medical Education at University Medical Center Utrecht. Her focus is on IPE. Information about the IPE ward can be obtained from her via [email protected]

Glossary

Self-determination theory of motivation (SDT): Distinguishes a range of motivation states: from fully extrinsic motivation (doing something because one feels obliged, without alignment with one’s own value system) through partly external and partly internal behavioral regulation (perceiving the value and relevance of the activity, but not finding the activity engaging) to fully intrinsic (doing something because one wants to do it, in full alignment with one’s value system). SDT refers to the latter two states as “autonomous motivation”. Autonomous motivation is increasingly manifest when something (1) has personal value, or (2) is an integral part of the person’s value system, or (3) is in itself engaging. Perceiving value, i.e. integrating an activity into one’s values leads to behavior that aligns with intentions.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. 2000. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 55:68–78.

Autonomous motivation: see Self-determination theory of motivation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all the students and supervisors who participated in the interviews and Dr Mathilde Nijkeuter, “Chief of Medicine”, Department of Internal Medicine.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Aelterman N, Vansteenkiste M, Van Keer H, Haerens L. 2016. Changing teachers beliefs regarding autonomy support and structure: the role of experienced psychological need satisfaction in teacher training. Psychol Sport Exerc. 23:64–72.

- Blondon KS, Maître F, Muller-Juge V, Bochatay Cullati SN, Hudelson P, Vu NV, Savoldelli GL, Nendaz MR. 2016. Interprofessional collaborative reasoning by residents and nurses in internal medicine: Evidence from a simulation study. Med Teach. 39:360–367.

- Cook DA, Kuper A, Hatala R, Ginsburg S. 2016. When assessment data are words: validity evidence for qualitative educational assessments. Acad Med. 91:1359–1369.

- Ericson A, Masiello I, Bolinder G. 2012. Interprofessional clinical training for undergraduate students in an emergency department setting. J Interprof Care. 26:319–325.

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. 2006. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 18:59–82.

- IPEC. 2016. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 update. Washington (DC): Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

- Jakobsen F. 2016. An overview of pedagogy and organisation in clinical interprofessional training units in Sweden and Denmark. J Interprof Care. 30:156–164.

- Kusurkar RA, Croiset G. 2015. Autonomy support for autonomous motivation in medical education. Med Educ Online. 20:27951.

- Kusurkar RA, Ten Cate TJ, Van Asperen M, Croiset G. 2011. Motivation as an independent and a dependent variable in medical education: a review of the literature. Med Teach. 33:e242–e262.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. 1990. Judging the quality of case study reports. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 3:53–59.

- Malterud K. 2012. Systematic text condensation: a strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand J Public Health. 40:795–805.

- O’Reilly M, Parker N. 2013. 'Unsatisfactory saturation': a critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qual Res. 13:190–197.

- Ponzer S, Hylin U, Kusoffsky A, Lauffs M, Lonka K, Mattiasson AC, Nordstrom G. 2004. Interprofessional training in the context of clinical practice: goals and students' perceptions on clinical education wards. Med Educ. 38:727–736.

- Ratelle CF, Guay F, Vallerand RJ, Larose S, Senecal C. 2007. Autonomous, controlled, and amotivated types of academic motivation: a person-oriented analysis. J Educ Psychol. 99:734–746.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. 2000. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 55:68–78.

- Thistlethwaite J, Moran M. World Health Organization Study Group on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. 2010. Learning outcomes for interprofessional education (IPE): Literature review and synthesis. J Interprof Care. 24:503–513.

- Vansteenkiste M, Sierens E, Soenens B, Luyckx K, Lens W. 2009. Motivational profiles from a self-determination perspective: the quality of motivation matters. J Educ Psychol. 101:671–688.

- Vansteenkiste M, Zhou MM, Lens W, Soenens B. 2005. Experiences of autonomy and control among Chinese learners: vitalizing or immobilizing? J Educ Psychol. 97:468–483.

- Visser CLF, Ket JCF, Croiset G, Kusurkar RA. 2017. Perceptions of residents, medical and nursing students about interprofessional education: a systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative literature. BMC Med Educ. 17:77.

- WHO. 2010. Framework for actions on interprofessional education and collaborative practice World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/index.html

- Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Pawson R. 2012. Realist methods in medical education research: what are they and what can they contribute? Med Educ. 46:89–96.