Abstract

Background

Students perceive reflective writing as difficult. Concept mapping may be an alternative format for reflection, which provides support while allowing students to freely shape their thoughts. We examined (1) the quality of reflection in reflective concept maps created by first-year medical students and (2) students’ perceptions about concept mapping as a tool for reflection.

Methods

Mixed-method study conducted within the medical curriculum of Maastricht University, The Netherlands, consisting of: (1) Analysis of the quality of reflection in 245 reflective concept maps created by 40 first-year students. Reflection quality was analysed by assessing focus of reflection (technical/practical/sensitising) and depth of reflection (description/justification/critique/discussion). (2) Semi-structured interviews with 22 students to explore perceived effectiveness of reflective concept mapping.

Results

Depth of reflection reached at least the level of critique in 82% of maps. Three factors appeared to affect the perceived effectiveness of concept mapping for reflection: (1) reflective concept map structure; (2) alertness to meaningful experiences in practice and (3) learning by doing.

Conclusion

These results yielded supportive evidence for concept mapping as a useful technique to teach novice learners the basics of effective reflection. Meaningful implementation requires a delicate balance between providing a supportive structure and allowing flexibility for the student.

Introduction

For students to become ‘fit for the future’ medical professionals, it is important that becoming reflective, life-long learners is part of their training. To stimulate the development of reflective skills, many undergraduate programs contain some kind of reflective writing assignments, often as part of a portfolio and combined with a mentoring system (van Tartwijk and Driessen Citation2009; van der Vleuten et al. Citation2014; Chertoff et al. Citation2016). Two major problems arise with this approach (Buckley et al. Citation2009; Belcher et al. Citation2014; Driessen Citation2017; de la Croix and Veen Citation2018): Firstly, students generally perceive reflective writing as very difficult. Reflection is a complex skill, and the requirement to ‘just write it down’ may be too difficult, at least for novice learners. Secondly, obligatory reflection assignments, with rigid content prescriptions and format requirements, are counterproductive as these limit the learners’ opportunities to make their reflections authentic (de la Croix and Veen Citation2018).

Practice points

When accompanied by clear instructions, concept mapping can support novice learners in engaging with reflection.

Allowing and encouraging students to develop their own design for their reflective concept maps may improve the quality and meaningfulness of the reflections.

Effectiveness of concept mapping for reflection depends on the context (portfolio system, mentor support, instructions, topics) in which it is implemented.

When implementing portfolios with concept maps, a balance must be found between directivity and support versus flexibility and autonomy for students.

Therefore, alternative formats to draw up reflections should be considered. These alternatives must provide support and at the same time provide flexibility to the students in the process of shaping and developing their reflections. Concept mapping (Ausubel Citation1968; Novak and Cañas Citation2008) may be an option that meets both these needs. Rooted in Ausubel’s work on meaningful learning (Ausubel Citation1968), in concept mapping, knowledge is organised and presented in a schematic diagram, consisting of boxes or circles containing concepts and arrows indicating relationships between concepts (Novak and Cañas Citation2008). Creating a concept map involves several deep reflective processes, such as discovering connections between events (Gray Citation2007; Daley Citation2010; Daley and Torre Citation2010). In addition, concept mapping offers opportunities to freely shape the line of reasoning to personal needs and preference (Torre et al. Citation2007).

The beneficial effects of using concept maps as a learning and teaching tool have been well established for the knowledge domain of education, for example in studies performed in (patho)physiology or clinical reasoning courses (Daley and Torre Citation2010). To our knowledge, studies on the use of concept maps for the purpose of reflection within the context of a portfolio are still scarce. A recent paper by Heeneman et al. (Citation2019) reports on the design and use of an e-portfolio mapping tool, however its effectiveness was not yet analysed.

Building on the assumption that concept mapping may provide support in reflection and flexibility in creating meaningful portfolios, we examined the effect of concept mapping on the quality of reflections made by undergraduate medical students. Specific research questions were:

What is the quality of reflection in reflective concept maps of first year undergraduate medical students, created in an eportfolio using concept mapping techniques?

How do students perceive concept mapping as a technique for reflection?

Methods

Study design

This research was designed as a sequential mixed methods study. In the first part the quality of reflection in reflective concept maps was studied using a combination of qualitative coding methods and descriptive statistics. The second part consisted of a series of individual interviews with students whose concept maps were analysed. The interviews were informed by the findings from the content analysis.

Setting

This study was performed within the undergraduate medical curriculum of Maastricht University, The Netherlands. This 6-year problem-based learning (PBL) (Dolmans et al. Citation2005) curriculum includes an integrated portfolio and mentoring system. For the portfolio an electronic web-based platform (EPASS, by Mateum BV, Maastricht, The Netherlands; www.epass.eu), including a concept mapping module (Heeneman et al. Citation2019), was used. The portfolio contains a collection of exam results and feedback, reflective concept maps on learning experiences and development of competences, personal learning goals, action plans and evaluations and reports of meetings with the mentor.

Each student is guided by a mentor. During the bachelor stage (years 1–3) this mentor is a faculty member involved in the curriculum. Student and mentor work together for the duration of the first three curriculum years and meet 3–5 times a year. Early in the curriculum the portfolio is primarily used as an instrument for guidance and to stimulate self-directedness and reflection.

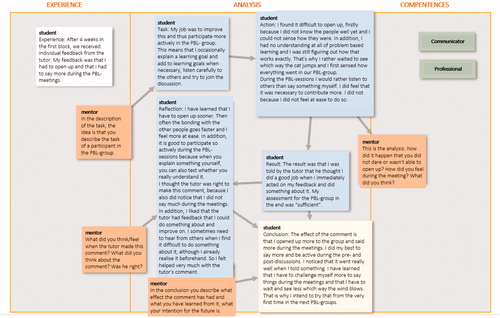

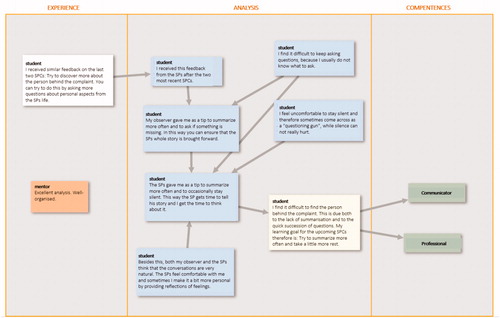

The current study focusses on reflections produced during year 1, when emphasis is on learning to recognise relevant learning situations and how to analyse these. Students are encouraged to actively identify experiences that made a (positive or negative) meaningful contribution to their learning and to analyse these in reflective concept maps. They are free to choose whatever experiences and occasions they think were relevant, within or outside their study setting. The year-1 portfolio is awarded with 6 out of the annual 60 credit points. Among other criteria, the year-1 portfolio is judged ‘sufficient’ if it contains at least 5 reflective concept maps. As a start-up guideline for structuring the reflective concept maps, students are informed about the STARR (Situation, Task, Action, Result, Reflection) method for analysis of critical situations, however they are free to design their concept maps differently according to their own views. Two examples of STARR and non-STARR constructed reflective concept maps are presented in and . In years 2 and 3 students continue expanding their collection of reflective concept maps.

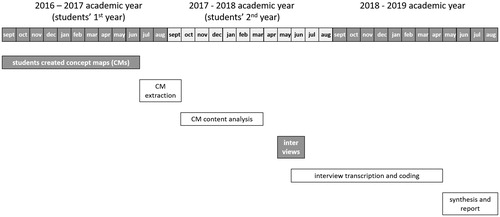

Subjects, sampling and timeline

An overview of the project timeline is presented in . Data from the 2016 cohort (n = 255 eligible students) were used. Sampling was random yet stratified per mentor (n = 57) in order to include no more than two students from the same mentor. E-mails inviting students to participate were sent to 150 students, which yielded a total number of 40 volunteers granting access to their portfolios. The reflective concept maps created by these students during the first year of their study were analysed. In addition, the following descriptive information was recorded: age, gender, mentor (coded) and number of reflective concept maps.

A purposive sample of 22 out of these 40 participants were approached for the interviews. Based on the analysis of reflection quality in the concept maps, students were selectively invited in order to represent the range of variations found in the concept maps. Sixteen students agreed to participate. Interviews took place in May and June 2018, when the students were in the second semester of their second year.

Analysis of quality of reflection in reflective concept maps

For the analysis of the quality of reflection in the concept maps, we used a framework previously developed by Leijen et al. (Citation2012) as a starting point.

Quality of reflection framework

Leijen et al. (Citation2012) combined Tsangaridou and O’Sullivan’s (Citation1994) view on type of reflection with Moon’s (Citation2004) ideas about reflection quality, which resulted in a two-dimensional matrix:

On one axis, focus or breadth of reflection is described using three categories: (1) technical reflection, which addresses procedural and management issues of an experience; (2) situational reflection, which focusses on the contextual issues and (3) sensitising reflection, which deals with the social, moral and ethical aspects of the experience. These categories are considered equivalent, not hierarchical.

On the other axis level of argumentation or depth of reflection is described using four, hierarchical, categories: (1) The lowest level is description, when the reflection consists of descriptive information only. (2) The second level of argumentation is justification, when a rationale or logic is included. (3) The third level is labelled critique, when the reflection contains aspects of explanation or evaluation. (4) The highest level of argumentation is discussion, which includes suggestions for alternative solutions.

Analysis

The initial code scheme was based on Leijen et al.’s three categories of focus and four levels of argumentation. Each separate text box on a reflective concept map was assigned one code for focus category (F1/F2/F3) and one for level of argumentation (A1/A2/A3/A4). The code scheme was further developed and tuned to the specific context during the analysis process; criteria regarding the contents of the texts were developed and specific language/phrasing criteria for each category (‘signal-words’) were distinguished. See and for the final coding schemes regarding focus of reflection and level of argumentation.

Table 1. Final coding scheme for focus of reflection.

Table 2. Final coding scheme for level of argumentation.

All coding was performed independently by JS & MV, following an iterative process with constant comparison. The reflective concept maps of three students were used to calibrate codes. Both assessors coded these sets of concept maps together, discussing boundaries of the different focus categories and argumentation levels. After the next five portfolios had been coded by both assessors independently, another consensus meeting took place in which code schemes were further fine-tuned, after which previous sets were recoded (iteration). Another consensus meeting took place after all reflective concept maps had been coded to resolve remaining discrepancies.

Interviews: procedure and analysis

Semi-structured interviews (lasting ca. 30 minutes) with individual students were conducted by SH. All sessions were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews were conducted iteratively; an interview guide containing open-ended questions was constructed a priori, based on the research question and the findings from the content analysis. This guide was adjusted after the first four interviews to better address emerging and previously unexplored themes in subsequent interviews. Participants in the interviews received a 10 euro gift voucher.

Interview transcripts were analysed conform a template analysis approach (King Citation2004). An a priori code template was defined based on the research questions, findings of the content analysis and the interview guide. The initial template was developed through independent coding (performed by JS and SH) of the first three interviews. The template was further developed through coding of subsequent interviews. At version 3 of the template, after coding of 6 interviews, it was agreed that the template adequately covered all texts so far. The remaining transcripts were coded by JS individually using this template version. At this stage, whenever JS thought further changes or additions to the template were indicated, she discussed with SH until agreement. After coding of 11 interviews, no more changes to the template were made. This final code template was further confirmed by analysis of the remaining 5 transcripts, which can be interpreted as a sign that code saturation (Hennink et al. Citation2017) was reached.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO file number 947). Since JS and MV are also involved in curriculum management, several measures were taken in order to avoid potential power issues. A research assistant, who did not know the students, initially accessed the portfolios of the selected students to extract the reflective concept maps. Extracted maps were converted to Powerpoint-slides and all names were removed. These anonymised concept maps were made available to the researchers. Regarding the interviews, transcription was outsourced and only coded transcripts (study ID-number) were used in analysis.

Results

Descriptives

Mean age of the sample of 40 students whose portfolios were analysed was 18.9 years (SD 1.0); 31 participants (77.5%) were female. They were supervised by 33 different mentors. For comparison: of the total cohort (n = 255), 70.5% was female and mean age was 18.8 years. The 40 portfolios contained a total number of 245 reflective concept maps (range 5–8). Seventy-five percent of the maps was STARR structured; 25% was structured differently. The subsample of students who were interviewed consisted of 3 males and 13 females.

Quality of reflection

In the paragraphs below, findings will be presented for focus of reflection and level of argumentation separately. However, overall all possible combinations of category of focus and level of argumentation were found in our sample.

Focus of reflection

Overall, a technical focus was evident in 910 text boxes (65.9%), a practical focus in 432 text boxes (31.3%) and a sensitising focus in a minority of 39 text boxes (2.8%). Students switched focus within a single reflective concept map, generalising from a technical towards a practical perspective. For example, dealing with group interactions (a topic often addressed in reflective concept maps, as in our PBL curriculum students frequently work together in small groups) was often addressed from the perspective of a single experience (= technical focus):

I was the discussion leader […], but I did not dare enough to take the lead and that's why everyone talked at the same time. (PF21/CM02/TB01; explanation of quote identifiers: PF = portfolio number; CM = concept map number; TB = text box number).

However, comparable issues were also addressed in a more general sense (= practical focus):

I am not used to taking the lead in [group] assignments. (PF25/CM02/TB4)

Finally, a few students looked at it from an even broader perspective (= sensitising focus):

[On working with many new people in PBL-groups:] This skill is one that must become automatic. As a doctor it is important to see each individual as equal to yourself. You also have to take into account that everyone is different. (PF19/CM01/TB05)

Comparable variations across types of focus were found concerning other topics, like patient communication and time-management.

Level of argumentation

Descriptions, the lowest level of argumentation, were found in all reflective concept maps and were used to inform the reader about situations, task aspects, actions and feelings related to the experience being analysed. Students typically used justification-level texts to explain underlying backgrounds and choices underpinning their actions. They also explained consequences of their own and other people’s actions at this level.

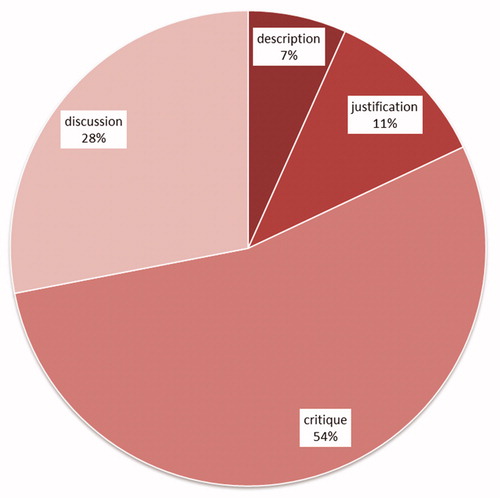

As can be seen in , in the majority (54%) of reflective concept maps, the level of critique was the highest level of argumentation reached. At this level, some degree of evaluation took place, expressing the ‘lessons learned’ from the experience that was analysed. These lessons and conclusions, although relevant, were not yet translated into real practical action plans for future occasions:

Figure 4. Pie chart showing the maximum level of argumentation reached per reflective concept map in the overall sample (n = 245 concept maps).

[On simulated patient contacts:] I still have to try to cut down drawing conclusions for the patient, less filling in for him or her. At the same time, I want to try to keep the natural aspect of a conversation and to improve it further. So that I can get along with every kind of patient later on. (PF12/CM02/TB05)

Many reflective concept maps did not go beyond this level. The level of discussion, in which the student clearly expressed intentions to really change behaviours, together with a concrete plan how to achieve this, was found in 28% of concept maps. Such plans mostly involved modest steps forward in personal development and study behaviour:

In the next course where I have many deadlines, I will make a comprehensive paper schedule. (PF33/CM05/TB06)

While shows the distribution of maximum levels of argumentation reached in the overall sample of reflective concept maps, considerable differences were noted between students. In 22 cases (55%) students reached a maximum level of critique in more than half of their concept maps. In 9 portfolios (22.5%) the majority of concept maps was at the level of discussion. In contrast, we encountered 3 portfolios (7.5%) that did not go beyond the level of justification in any reflective concept map.

Interviews

From the students’ perceptions a nuanced image about the merits of concept mapping for reflection became evident. On the one hand, students acknowledged that creating reflective concept maps, under the right circumstances, helped them in structuring their thoughts and reaching a certain level in reflection. On the other hand, they were critical about the conditions that had to be met for this practice to be effective. From our analysis three factors determining the effectiveness of concept mapping for reflection as perceived by the students, emerged: (1) structuring reflective concept maps; (2) alertness to meaningful experiences and (3) (not) learning by doing.

Structuring reflective concept maps

Students mostly applied the STARR structure as instructed, and indicated that this gave them a concise scaffold how to build up their reflection, which led to an engagement with the process and reflective activity:

You can address things in a structured way. So it's not a long confused story, but you can say, okay, this is the experience, and this is what I had to do, and this is what I thought of it, and this is what I could have done better, or this is going to be a lesson or something. So I think it's good that you can break it down. And then you can think about it a little more consciously, I think. Yes. (S13)

However, the STARR structure was also criticized to be forced and artificial. Students clearly expressed a dilemma between the need for scaffolding and grip on the one hand and flexibility in map structure on the other hand:

Well, that structure is at the same time an advantage and a disadvantage. Because you have to stick to it, it is a sort of straitjacket. So on the one hand it forces you to structure and on the other hand it restricts you to let your thoughts run free. (S8)

Interestingly, although the STARR structure was not mandatory, students were hesitant to structure their reflective concept maps differently. Feeling insecure about assessment criteria and without examples of differently structured reflective concept maps that were judged as adequate, they chose to stick with the safety of the given structure.

I started doing it this way so that my mentor would be okay with it…(S2)

Alertness to meaningful experiences

Another factor influencing effectiveness was the selection of suitable experiences as topics for the reflective concept maps. Students were free to choose their own, personal experiences to reflect on. Most students could describe one of the concept maps when asked in the interview, and indicated that these maps were valued positively. Maps were perceived valuable if these helped dealing with situations with a relevant impact for the student. Reflective concept maps that were retrospectively identified by the students as effective helped them to deal with heavy emotions, elicited an eye-opening personal or professional insight or were connected with an effective learning goal:

I made a map about the progress test. I learned a lot from that, because I recognized that I really had a lot of stress for exams and even if you didn't have to prepare at all that the stress can be very high. And I recognize that in several other situations, that you think… oops… I think this map has been a huge eye-opener for me. (S16)

However, students also indicated that being alert to meaningful experiences was not part of their daily routine. Reflective concept maps often were created just before the deadline. This led to maps related to more general or futile subjects. Since these maps did not arise from personally impactful situations, reflection effectiveness and learning value was perceived as limited:

Well, usually one map is always, I know, that has impressed me, and I want to make a map about that, and it's very easy. But usually the second, or, and or the third, then I'm really wondering, what am I going to think of to make a map about? And I think that's a bit of a pity about the maps. […] Well, with such an experience that you remember right away, and that has impressed you a lot, and so you just take some time to think about it, I think I'm sure I'll learn something from it. But with those maps that I ask others for ideas to make a map about, I don't learn anything from those. (S13)

(Not) learning by doing

Although students disliked the minimum required numbers of reflective concept maps, they generally did acknowledge that having to create a number of maps triggered them to reflect and made them see the purpose (‘learning by doing’). Also, frequent practice improved their quality of reflection:

And I get it why you want us to do that. Yes, it's very difficult that early. Especially when you're so fresh out of high school I think that's still, yes, suddenly something very strange that you have to do. […] And now I understand, now that I've been working a bit longer, I understand better when I'm going through something, so I can put it in a map to get some things out of it. (S5)

However, some students after a year of practice did not see the benefit of reflection:

I think that in real life if you experience something then it is not necessary to analyze […] You don't really see, maybe it helps if I reflect on how I've done something. (S8)

A few felt that it was too early in their undergraduate trajectory to engage in reflection:

‘I'm a student, I'm not a medical expert yet. That is something very… I think too broad or something, too far-fetched yet.’ (S5)

Other students preferred to reflect in other ways, for example ‘on the spot’ immediately after an experience, or in discussions with friends. This too led to a perception of limited learning value of concept mapping for reflection and maps were made only to pass the requirements:

If I also write it in the map, I don't feel like I'm doing a lot more with it. Then I have more of a feeling that I'm putting this in the map because I have to make maps than that I'm actually learning something from it. (S4)

Discussion

The findings from this study indicate that concept mapping may be a useful approach to teach first-year medical students the basics of reflection. The analysis of actual maps showed that most students were able to produce reflections of appropriate quality through concept mapping (research question 1). The students’ perceptions of the value of concept mapping for reflection depended on finding an effective map structure, their alertness to meaningful experiences and learning by doing (research question 2).

The results of our ‘per textbox’ analysis of reflective concept maps showed that concept mapping helped building a step-by-step line of reasoning, from description of the situation, through justification-level elaborations, to reflections at the level of critique or discussion. The final levels of reflection quality reached through this stepwise reasoning approach may be interpreted as an indication that first-year students are able to produce adequate reflections through concept mapping. In the interviews, students acknowledged the supportive features of the mapping approach. Although, it did not agree with every student’s personal learning or reflection preferences. The interviews offered several explanations for these differences. Students argued that effective and meaningful reflection was only reached if they learned to recognise and note relevant experiences as topics for their reflective concept maps and when practising with the first few maps helped them overcome an indiscernible ‘threshold’ to engage in genuine reflection.

In light of the ‘reflective zombies’ discussion triggered by de la Croix and Veen (Citation2018), this finding might support the notion that we should embrace and respect the diversity of ways students use to reflect. As such the results of this study might serve as an argument in the plea for more flexibility for students to work out their own reflective practice format. At the same time, and although intuitively contradictionary with the previous, the students confirmed that a mandatory start, following a superimposed systematic approach, might be helpful to grow from fulfilling assignment criteria to the first sparks of genuine reflection.

In the interviews students clearly pointed out the dilemma between the need for support in structuring their reflections and the need for flexibility to freely shape their own lines of thoughts and to select their own occasions for reflection. It seems hard to strike the balance right. Our approach to let students self-select experiences to reflect on, was perceived as positive in the sense that students mentioned examples of actual reflective concept maps that made an impact on their learning. On the other hand, the majority of students created the five reflective concept maps that were required to pass the year-1 portfolio assessment, and not more. This may imply that students, despite being encouraged to create reflective concept maps when and as many as they judge relevant, they did not do more than expected. Students reported that being alert to meaningful experiences was not part of their daily routine, which illustrates once more how difficult it is to successfully embed reflective activities within a curriculum (Sandars Citation2009; Aronson Citation2011).

Regarding reflective concept map structure, students hardly deviated from the STARR structure, which was meant to be just a guideline. Apparently the safe choice outweighed the need for flexibility which could have had enriched their reflections. This once more illustrates how (students’ perceptions of) assessment criteria steer students’ study behaviours (Heeneman et al. Citation2015; Schut et al. Citation2018). At this point the mentor must also maintain a balance, on the one hand supporting novice learners with clear scaffolding on reflection, but on the other hand giving room to let the student experiment to structure their reflections differently (Meeuwissen et al. Citation2019; Loosveld et al. Citation2020). More experimenting and alternative map structuring may be stimulated by providing students with multiple examples of differently structured reflective concept maps to compare. Ideally, offering a spectrum of several options, ranging from highly directed approaches, like prestructured concept maps combined with instructive mentor support, to low-directed options (using personal concept map design and a mentor who acts as sparring partner and coach), from which to choose and switch between, might be beneficial to capture, scaffold and enhance the reflective process and meet different students’ needs.

A limitation of this study is the fact that the influence of the mentor was not included. The feedback from the mentor (or the absence thereof) may have strongly determined reflective concept map quality (Driessen et al. Citation2007). Also, a mentor may potentially have a substantial influence on what topics students choose to address and the way they structured their concept maps.

Another point to keep in mind is that our sample may have been biased to some degree. We cannot rule out that students who felt less confident about the quality of their portfolios decided not to volunteer for this study. This may have biased our findings towards the positive.

Finally, we need to stress that this was an exploratory and descriptive study on the potential of using concept mapping for reflective purposes in a portfolio. The nature of the design does not allow any comparison with other methods for reflection and thus no inferences can be made whether concept mapping yields better results than other formats to develop reflective skills.

This was, to our knowledge, one of the first studies exploring the potential of concept mapping as a tool to train reflective skills within the context of a portfolio. A topic to further explore would be the influence of the mentor and his/her feedback on the level of support and flexibility as perceived by students. Furthermore, it would be interesting to examine the learning processes related to reflective concept maps that students consider to be effective, as these might indicate transformational learning to take place. How do these maps trigger new insights, and what role does reflective concept mapping play in personal knowledge restructuring? Finally, it would be worthwhile to extend this research to subsequent study years to see how students’ reflective concept maps develop.

Conclusions

Concept mapping is a promising tool to develop reflective skills in undergraduate medical students. Students reflecting on self-selected experiences, the supportive features of the concept mapping approach and the mainly adequate reflection quality were considered as positive signs. However, instead of suggesting just another mandatory format for reflection, our findings also highlighted the need for flexibility to shape reflective practice to personal need and preferences. An important next step would be to strike the right balance between providing scaffolding on the one hand and giving agency to students on the other.

Glossary

Concept mapping: In concept mapping, knowledge is organised and presented in a schematic diagram, consisting of boxes or circles containing concepts and arrows indicating relationships between concepts (Novak and Cañas Citation2008). In creating a concept map, several cognitive processes are stimulated, such as distinguishing main issues from side-issues, breaking down concepts into smaller components through analysis, and linking components to synthesise meaningful relationships (adapted from Daley Citation2010).

References

Novak JD, Cañas AJ. 2008. The theory underlying concept maps and how to construct and use them. Technical Report IHMC CmapTools 2006-01 Rev 01-2008. Institute for Human and Machine Cognition.

Daley BJ. 2010. Concept maps: practice applications in adult education and human resource development. New Horizons Adult Educ Hum Resour Dev. 244(2–4):31–37.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Judith M. Sieben

Judith M. Sieben, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the Department of Anatomy & Embryology and the Care and Public Health Research Institute, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Sylvia Heeneman

Sylvia Heeneman, PhD, is a Professor of Medical Education at the School of Health Professions Education, Department of Pathology, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Mascha M. Verheggen

Mascha M. Verheggen, PhD, is a senior lecturer at the School of Health Professions Education, Department of Educational Development and Research, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Erik W. Driessen

Erik W. Driessen, PhD, is a Professor of Medical Education at the School of Health Professions Education, Department of Educational Development and Research, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

References

- Aronson L. 2011. Twelve tips for teaching reflection at all levels of medical education. Med Teach. 33(3):200–205.

- Ausubel DP. 1968. Educational psychology: a cognitive view. New York (NY): Holt, Reinhart & Winston.

- Belcher R, Jones A, Smith LJ, Vincent T, Naidu SB, Montgomery J, Haq I, Gill D. 2014. Qualitative study of the impact of an authentic electronic portfolio in undergraduate medical education. BMC Med Educ. 14:265.

- Buckley S, Coleman J, Davison I, Khan KS, Zamora J, Malick S, Morley D, Pollard D, Ashcroft T, Popovic C, et al. 2009. The educational effects of portfolios on undergraduate student learning: a Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide No. 11. Med Teach. 31(4):282–298.

- Chertoff J, Wright A, Novak M, Fantone J, Fleming A, Ahmed T, Green MM, Kalet A, Linsenmeyer M, Jacobs J, et al. 2016. Status of portfolios in undergraduate medical education in the LCME accredited US medical school. Med Teach. 38(9):886–896.

- Daley BJ. 2010. Concept maps: practice applications in adult education and human resource development. New Horizons Adult Educ Hum Resour Dev. 24(2–4):31–37.

- Daley BJ, Torre DM. 2010. Concept maps in medical education: an analytical literature review. Med Educ. 44(5):440–448.

- de la Croix A, Veen M. 2018. The reflective zombie: problematizing the conceptual framework of reflection in medical education. Perspect Med Educ. 7(6):394–400.

- Dolmans DH, De Grave W, Wolfhagen IH, van der Vleuten CP. 2005. Problem-based learning: future challenges for educational practice and research. Med Educ. 39(7):732–741.

- Driessen E. 2017. Do portfolios have a future? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 22(1):221–228.

- Driessen E, Muijtjens AM, Van Tartwijk J, Van der Vleuten CP. 2007. Web- or paper-based portfolios: is there a difference? Med Educ. 41(11):1067–1073.

- Gray DE. 2007. Facilitating management learning: developing critical reflection through reflective tools. Manag Learn. 38(5):495–517.

- Heeneman S, Driessen E, Durning SJ, Torre D. 2019. Use of an e-portfolio mapping tool: connecting experiences, analysis and action by learners. Perspect Med Educ. 8(3):197–200.

- Heeneman S, Oudkerk Pool A, Schuwirth LW, van der Vleuten CP, Driessen EW. 2015. The impact of programmatic assessment on student learning: theory versus practice. Med Educ. 49(5):487–498.

- Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. 2017. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough? Qual Health Res. 27(4):591–608.

- King N. 2004. Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In: Cassel C, Symon G, editors. Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research. London: Sage; p. 256–270.

- Leijen A, Valtna K, Leijen DAJ, Pedaste M. 2012. How to determine the quality of students' reflections? Stud High Educ. 37(2):203–217.

- Loosveld LM, Van Gerven PWM, Vanassche E, Driessen EW. 2020. Mentors' beliefs about their roles in health care education: a qualitative study of mentors' personal interpretative framework. Acad Med. 95(10):1600–1606.

- Meeuwissen SNE, Stalmeijer RE, Govaerts M. 2019. Multiple-role mentoring: mentors' conceptualisations, enactments and role conflicts. Med Educ. 53(6):605–615.

- Moon JA. 2004. Reflection in learning and professional development. New York (NY): Routledge.

- Novak JD, Cañas AJ. 2008. The theory underlying concept maps and how to construct and use them. Technical Report IHMC CmapTools 2006-01 Rev 01-2008. Institute for Human and Machine Cognition.

- Sandars J. 2009. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Med Teach. 31(8):685–695.

- Schut S, Driessen E, van Tartwijk J, van der Vleuten C, Heeneman S. 2018. Stakes in the eye of the beholder: an international study of learners' perceptions within programmatic assessment. Med Educ. 52(6):654–663.

- Torre DM, Daley B, Stark-Schweitzer T, Siddartha S, Petkova J, Ziebert M. 2007. A qualitative evaluation of medical student learning with concept maps. Med Teach. 29(9):949–955.

- Tsangaridou N, O’Sullivan M. 1994. Using pedagogical reflective strategies to enhance reflection among preservice physical education teachers. J Teach Phys Educ. 14(1):13–33.

- van der Vleuten CP, Schuwirth LW, Driessen EW, Govaerts MJ, Heeneman S. 2015. 12 Tips for programmatic assessment. Med Teach. 37(7):641–646.

- van Tartwijk J, Driessen EW. 2009. Portfolios for assessment and learning: AMEE Guide no. 45. Med Teach. 31(9):790–801.