Abstract

Background

Stereotypes are oversimplified beliefs about groups of people. Social psychology concepts and theories describing ethnicity-related stereotypes are well reported in non-medical educational settings. In contrast, the full impact of stereotyping on medical students, and the extent to which they were represented in health professions education (HPE) is less well-described. Using the lens of social psychological theory, this review aimed to describe ethnicity-related stereotypes about medical students portrayed in HPE literature and the impacts of those stereotypes.

Methods

A critical narrative approach was undertaken. Social psychology concepts and theories were used as a framework through which to review the impacts of ethnicity-related stereotypes on medical students as described in HPE literature. A database search of Ovid MEDLINE, JSTOR, Project Muse, and PsychINFO was conducted to identify both theoretical and empirical articles relating to this topic in the HPE literature. Data was synthesised using thematic analysis, giving particular care to appraise the evidence from perspectives in social psychology.

Findings

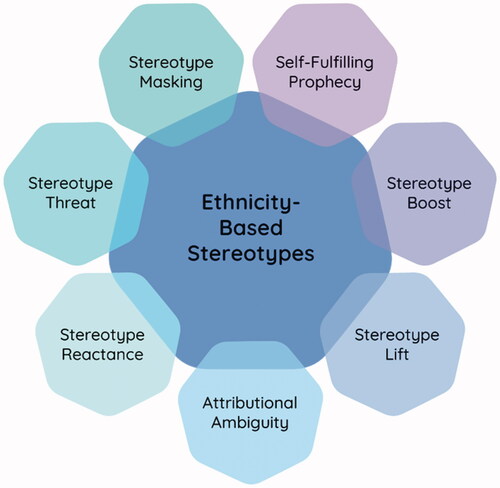

In HPE, the experiences and impact of stereotyping on learners from minority ethnic groups was explained by social psychology concepts such as stereotype threat, stereotype reactance, attributional ambiguity, self-fulfilling prophecy, stereotype boost, stereotype lift, and stereotype masking. Stereotype boost and stereotype lift were particularly described among students who identified as White, whereas stereotype threat was described more commonly among students from minority ethnics groups. The impact of stereotyping is not just on assessment, but may be across all teaching and learning activities at medical school.

Interpretation

Social psychology concepts and theories can be used to describe the experience and impact of ethnicity-related stereotypes in HPE. Educators can better support learners from minority ethnic groups by self-reflecting over assumptions about individuals from minority ethnic groups, as well as minimise the impact of stereotyping and bias to create more inclusive learning environments.

Introduction

Assumptions are made about patients from minority ethnic backgrounds based on stereotyped opinions rather than evidence-based medicine (Van Ryn and Burke Citation2000; Lim et al. Citation2021). There is a growing recognition that a similar phenomenon is likely happening in medical education to minority ethnic students (Woolf et al. Citation2013). Minority ethnic students here refers to students from a different ethnic group to the dominant ethnic group in the country in which they live, for the example individuals who are White British form the dominant ethnic group in the United Kingdom (UK) (Bravata et al. Citation2020). Aside from stereotyping affecting the lived experience of these students, there is evidence that stereotyping may be contributing to the achievement or attainment gap in medical education as well (Woolf et al. Citation2013). Stereotypes are oversimplified beliefs that homogenise all persons in a group into a single characteristic or descriptor (Mcgarty et al. Citation2002). Given stereotypes are socially constructed and operate on an intergroup level (Haslam et al. Citation2009), insights about their nature can be gained from integrating perspectives from social psychology and cognitive science.

Practice points

The impact of stereotyping on medical students can be explained by several well-described phenomena in social psychology research: stereotype threat, stereotype reactance, attributional ambiguity, self-fulfilling prophecy, stereotype boost, stereotype lift and stereotype masking.

Stereotypes that group individuals that are highly heterogeneous based on one shared ethnic characteristic inevitably leads to stereotypes that neglect individual values that are critical for effective medical education and the development of clinical reasoning skills.

Stereotypes do not exist solely for one specific group in health professions education literature.

Positive stereotypes may in their own way be contributing to the differential attainment among students of various ethnicities at medical school.

There are strategies that can reduce the adverse impacts from stereotypes on medical students.

Data suggest stereotypes function to emphasise a person’s similarities with others in their ‘in’-group and accentuate differences of those who are not (Haslam et al. Citation2009). This social impact of stereotyping may be better understood in relation to cognitive processes, specifically those related to unconscious information-processing (McGarty et al. Citation2009). Humans instinctively stereotype and categorise individuals on the basis of demographic characteristics (Jacoby et al. Citation1992; Bargh and Chartrand Citation1999; Wheeler and Fiske Citation2005) since these provide the mental shortcuts (heuristics) that help individuals manage the significant cognitive effort and time required to assimilate and process constant streams of information around them (Macrae et al. Citation1994). Whilst heuristics can be helpful for reducing the complexity of that information, stereotypes about individuals prioritise generalisation over individualisation (Wheeler and Fiske Citation2005), and therefore can lead to bias.

There has been research into bias, stereotypes, and prejudice in the field of social psychology (Watson et al. Citation2011; Hall et al. Citation2015; Charlesworth and Banaji Citation2019), particularly investigating the impact of these phenomena on minority ethnic groups (Watson et al. Citation2011; Hall et al. Citation2015). For instance, when students who self-identified as African American were given a task framed as an intelligence test, they performed worse than individuals who self-identified as White (C. M. Steele and Aronson Citation1995). However, when the same task was framed as non-diagnostic of intelligence, no difference in performance was observed between individuals from different ethnic groups (C. M. Steele and Aronson Citation1995). In other words, performance was negatively impacted by a stereotyped identity (e.g., intelligence) being activated prior to a test being touted to measure something linked to said stereotype. Such phenomena may exist in medical education (Burgess et al. Citation2010), and could play a role in the differential attainment among students of various ethnicities at medical school (Woolf et al. Citation2013). Even before arriving at university, bias is demonstratable and an explanatory variable for the differential admission of minority ethnic candidates into medical school (Esmail et al. Citation1995; McManus et al. Citation1995).

However, it was unclear as to whether social psychological concepts and theories developed in other educational settings are transferrable to explain lived experiences in medical education (Given Citation2012), and if so, the extent to which they were represented in health professions education (HPE) literature. To fill this gap, we conducted a critical narrative review that primarily aimed to describe the ethnicity-related stereotypes about medical students that were portrayed in HPE literature and the impacts that those stereotypes were described to have on individuals. This review aimed to make sense of these impacts through the lens of various social psychological theories. Given medical educators have a social responsibility to ensure inclusive learning environments (Razack and Philibert Citation2019), this review facilitates this by raising awareness of ethnicity-related stereotypes, their impacts on medical students, and gaps in the extant literature.

Methods

Organisational framework

Given the interpretivist nature of this research, and limited number of empirical studies within healthcare professions that have drawn on social psychology concepts for investigating in this area, a critical narrative approach was used to explore ethnicity-related stereotypes about medical students in HPE literature and the impacts of those stereotypes. In completing our critical narrative review, we followed the frameworks laid out by Grant and Booth (Citation2009) and Dixon-Woods et al. (Citation2005) This involved identifying a selection of relevant articles on this topic, evaluating them according to their judged contributions (i.e., an article detailing the impact of an ethnicity related stereotype on medical students) – rather than their methodological quality –, and offering a reflexive interpretation of their content. This inductive approach to analysing the results of the knowledge synthesis enabled a social psychological lens to be used to evaluate the impact of ethnicity-related stereotypes on medicals students.

Stereotype threat (Steele and Aronson Citation1995), stereotype reactance (Kray et al. Citation2001), attributive ambiguity (Crocker et al. Citation1991), identity threat (Derks et al. Citation2016), self-stereotyping (Kaldis Citation2013), self-fulfilling prophecy (Kaldis Citation2013), stereotype boost (Shih et al. Citation2012), and stereotype lift (Walton and Cohen Citation2003) are well-described social psychological theories that occur secondary to stereotypes. These social psychological concepts and theories were used as a framework through which to review the impacts of ethnicity-related stereotypes on medical students as described in HPE literature. It should be noted that while each phenomenon is mentioned as a discrete concept in this review, they are generally linked and should ideally be viewed as overlapping in practice. To better learning environments, it is critical that the impacts of a stereotype on individuals are considered.

Given the focus of the review was on ethnicity related stereotypes, it was also essential that the significant heterogeneity in the terms used to describe medical students of various ethnicities was addressed before the review was conducted. The fact that the term ‘African American’ is used in the United States of America (USA), whilst terms such as BME (Black or Minority Ethnic) or BAME (Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic) are more prevalent in the UK likely derive from the social histories of these countries (Eligon Citation2020). Devising new categorisations that truly represented the geographical, behavioural, social, and cultural diversity of individuals would not only be challenging but could lead to misclassification and mischaracterisation. Therefore, for the purposes of this review the choice was made to continue using the terms cited in the original article when describing ethnicity-related stereotypes and their impacts, also allowing for a more granular description of the demographic group affected by a stereotype.

Selection and search criteria

There were no restrictions on language or article type. Articles were included if they described [1] an ethnicity-related stereotype on medical students AND its impact, OR [2] a social psychological theory that explained the impact of an ethnicity-related stereotype on medical students. Although culture, ethnicity, and race are not merely synonyms for one another – they point to vastly different dimensions of social order –, there is extensive evidence that researchers often use the terms interchangeably (Hamer et al. Citation2020). Therefore, articles describing stereotypes attributed to race and culture were included too. Articles that were not related to HPE were excluded. Prior to the commencement of this study, all reviewers attended an online training and support session to ensure an accurate and standardised approach to the overall methodological process. The search strategy, data synthesis and synthesis of results described below were formulated based on frameworks for conducting critical narrative reviews (Dixon-Woods et al. Citation2005; Eva Citation2008; Grant and Booth Citation2009; Norman and Eva Citation2018).

Two parallel searches of academic bibliographic databases and grey literature were undertaken. This ensured the search returns were large enough to be a representative sample of the health professions education (HPE) literature.

Bibliographic search: the search strategy for this review was executed in Ovid MEDLINE, JSTOR, Project Muse, and PsychINFO, covering the period from each database inception to November 26th, 2020. The search strategy used variants and combinations of search terms related to stereotypes, ethnicity, education, and health professions. A sample database search strategy is provided in Supplementary Appendix S1. The retrieved studies were exported, and duplicate articles were discarded. Three reviewers (three of CTB, YGB, AC, AA, HK, or NB) independently screened the titles and abstracts of identified records based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed above. The full texts of the remaining articles were retrieved and screened by two reviewers independently (SB and one of CTB, YGB, AC, AA, or HK). Disagreements were resolved by mutual agreement. The reference lists of all included articles and previously excluded review articles were scrutinised to locate additional relevant publications not identified during the database searches. The reviewers also consulted with senior medical educators and social psychologists to identify additional publications.

Grey literature search: a grey literature search was performed to include additional sources that described either [1] an ethnicity-related stereotype on medical students AND its impact, OR [2] a social psychological theory that explained the impact of an ethnicity-related stereotype on medical students. These sources included articles not indexed in the databases searched above, educational reports, and books. Snowball searching using a web-based search engine (Google) was used to find these additional sources. A pragmatic approach was taken for the grey literature search, where only results from the first 3 pages of hits were definitively examined. The reference list of all included documents identified through the grey literature search was examined to identify any further relevant documents missed through the above search strategy, until a saturation point was reached where no new sources were identified.

All searches were completed in duplicate by two reviewers independently. A third reviewer validated these searches and resolved any disparities when they arose.

Data extraction

Data extraction was completed in duplicate by two reviewers independently (SB and one of CTB, YGB, AC, AA, or HK). A third reviewer validated the data extracted and resolved any disagreements. Several data points were extracted, including publication characteristics, article type, ethnicity-related stereotypes about medical students, and the impacts that those stereotypes were described to have.

Synthesis of results

The ethnicity-related stereotypes about medical students that were reported to have an impact were descriptively presented. Thematic synthesis was used to explain the impact of an ethnicity-related stereotype on medical students through the lens of a social psychological theory, as this allowed for common elements from the different articles to be brought together via an inductive process. Thematic synthesis is a pragmatic approach to qualitative analysis that involves searching for patterns or themes across an entire dataset. Critically for the purposes of this review, thematic analysis facilitates both inductive and deductive strategies (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), enabling the analysis of HPE literature to be explicitly informed by pre‐existing theories in social psychology.

During the inductive process of coding the data points and generating themes, priority was given to fairly representing all the different perspectives about the phenomena under investigation to produce a respectful and balanced judgment of the assumptions and the associated evidence reported in the included studies. To appraise the evidence from multiple perspectives, the research team consisted of individuals that represented a spectrum of social psychology thought, from biopsychosocial to social-learning to social-cognitive to humanistic. The research team consisted of authors from a wide spectrum of ethnicities that were representative of the groups being discussed. Regular team discussions were had to discuss divergent opinions and refine the synthesis of the results.

Results

Ethnicity-related stereotypes are portrayed in HPE literature

Following the process described above, 14 articles were included for the purposes of this review (). There were several unique stereotypes specific to minority ethnic groups in healthcare professions education (). Distinct and different stereotypes were reported to exist of ‘Asian,’ ‘Black,’ ‘African-American,’ ‘Latinx,’ ‘Native-American’ and ‘White’ medical students. Two of the included texts grouped all non-White health professions students together when discussing stereotypes about minority ethnic students and did not account for the different stereotypes that exist for individuals from each minority ethnic sub-group (Burgess et al. Citation2010; Kupiri Ackerman-Barger et al., Citation2015).

Figure 1. Phenomena that will be used as a framework through which to review the impacts of ethnicity-related stereotype in medical education.

Figure 2. Flowchart of the literature search and study selection process for the critical narrative review. Articles were included if they described [1] an ethnicity-related stereotype on medical students AND its impact, OR [2] a social psychological theory that explained the impact of an ethnicity-related stereotype on medical students. Articles that were not related to HPE were excluded.

![Figure 2. Flowchart of the literature search and study selection process for the critical narrative review. Articles were included if they described [1] an ethnicity-related stereotype on medical students AND its impact, OR [2] a social psychological theory that explained the impact of an ethnicity-related stereotype on medical students. Articles that were not related to HPE were excluded.](/cms/asset/c3db5e2f-5106-4c81-839b-14297f50bb65/imte_a_2051464_f0002_c.jpg)

Table 1. An alphabetical list of the studies that described ethnicity-related stereotypes about medical students in health professions education literature.

Stereotype threat

Steele and Aronson (Citation1995) defined stereotype threat as being ‘at risk of confirming, as self-characteristic, a negative stereotype about one’s group.’ In this review, stereotype threat was described in 8 out of 14 articles in HPE literature (Bullock et al. Citation2020; Bullock and Houston Citation1987; Erwin et al. Citation2002; Kupiri Ackerman-Barger et al., Citation2016; Lempp and Seale Citation2006; Liebschutz et al. Citation2006; Morrison et al. Citation2019; Woolf et al. Citation2008). The impact of stereotype threat on medical students included stress, anxiety, self-doubt and fear. With respect to the impact of learning, the consequent stress arousal limited the cognitive resources that individuals could allocate to a given task:

A white boy goes into class to take a test and he just has to worry and concentrate on the test. Every time a black boy goes into the class he has to try hard to stay focused on the work, on the content, because he's worrying about what the professor thinks of him, what the other students think of him, whether or not he has on the right clothes, or is acting the right way, or what his mother will do if he doesn't do well on this test. (Erwin et al. Citation2002)

This stress arousal also increased stereotyped individuals’ sense of self-consciousness about performance and self-worth (Bullock et al. Citation2020; Kupiri Ackerman-Barger et al., Citation2016; Liebschutz et al. Citation2006). Black medical students described how anxious they became when they did not do well in exams as they felt they had lived up to the stereotype of not being intelligent and reinforced beliefs that others held about Black people (Kupiri Ackerman-Barger et al., Citation2016). Black (Liebschutz et al. Citation2006; Kupiri Ackerman-Barger et al., Citation2016) and Latinx students (J. L. Bullock et al. Citation2020) also had self-doubts about whether they deserved to be in medical school due to the stereotype of being intellectually inferior. They expressed feelings of wondering whether they were just admitted because of affirmative action; in other words medical schools wanting ‘to recruit more people of color’ (Liebschutz et al. Citation2006). Stereotypes about confrontation affected Black medical students (Bullock et al. Citation2020; Claridge et al. Citation2018; Morrison et al. Citation2019). The existence of these particular stereotypes hindered Black students from continuing in HPE (Dana L. Carthron, Citation2007), especially if they felt they could not oppose perceived structural issues to their progression for fear of being labelled as confrontational and living up to the stereotype.

Different stereotypes resulted in stereotype threat among different groups of medical students. For instance, the stereotypes of medical students pursuing medicine to conform to their parents’ wishes rather than an intrinsic motivation (Woolf et al. Citation2008; Morrison et al. Citation2019) affected Asian students. Whereas stereotypes about individuals not being as intelligent as their contemporaries of other skin colours affected Black and African American students (Bullock and Houston Citation1987; Erwin et al. Citation2002; Kupiri Ackerman-Barger et al., Citation2016; Lempp and Seale Citation2006; Liebschutz et al. Citation2006; Woolf et al. Citation2008). Furthermore, actual stereotyping did not need to have occurred in order for stereotype threat to occur; it was sufficient for an individual to merely have knowledge that a negative stereotype existed about a demographic group they belonged to (Claridge et al. Citation2018).

Attributive ambiguity and self-fulfilling prophecy

Crocker et al. (Citation1991) defined attributive ambiguity as individuals questioning the validity of any judgment about their competency or performance as a consequence of stereotyping. The ambiguity results in individuals being uncertain as to whether the feedback they are being given is genuine and based on actual performance, or whether feedback has been biased by stereotyping. In this review, attributive ambiguity was described in 2 articles. Black students reported feeling uncertain as to whether negative feedback was due to an evaluator’s stereotypes about Black people rather than due to actual shortcomings in performance (J. L. Bullock et al. Citation2020). The same logic was applied to their feelings about positive feedback (Kupiri Ackerman-Barger et al., Citation2015).

A self-fulfilling prophecy is described as a phenomenon where beliefs or expectations – whether correct or not – can become perceived to be true because of people’s behaviours aligning to fulfil a particular stereotype (Kaldis Citation2013). In this review, self-fulfilling prophecy was described in 6 articles. At an individual level, stereotypes that depicted minority ethnic students as less capable, less valuable, and less successful contributed to minority ethnic individuals changing the way they perceived themselves, acting in a stereotype-consistent way, and confirming to their own erroneous expectations (Kupiri Ackerman-Barger et al., Citation2015):

I am not going to study because, you know, students like me don’t do well on these tests anyway, so why should I even try? (Kupiri Ackerman-Barger et al., Citation2015)

At a social level, stereotypes were also reinforced as peers from other ethnic groups changed their behaviour in response to prevailing stereotypes. Minority ethnic students were perceived to be less sociable (Beagan Citation2003) or less likely to join team bonding activities (Roberts et al. Citation2008). These beliefs were then further reinforced through planning social activities that were exclusionary of certain minority ethnic students, such as ‘drinking games’ (Roberts et al. Citation2008; Claridge et al. Citation2018).

At an institutional level, health professions educators holding stereotypes of minority ethnic students also resulted in them changing their behaviours in a stereotype-consistent manner. Health professions educators stereotyping Asian medical students as ‘reserved,’ were subsequently ‘antagonistic’ towards them during teaching sessions in order to just elicit an active response (Woolf et al. Citation2008). This change in behaviour resulted in these students feeling less able to interact with their health professions educator (Woolf et al. Citation2008), further perpetuating the original stereotype. Similar stereotypical beliefs held by health professions educators about the intelligence of African American students being insufficient for them to become doctors resulted in advice that prevented African American students from accessing enhanced educational opportunities and progression towards applying to medical school (Erwin et al. Citation2002).

Stereotype lift and stereotype boost

Stereotypes do not solely have a negative impact on individuals. Walton and Cohen (Citation2003) described Stereotype lift: a phenomenon where stereotypes of people who are not members of the ‘in’-group results in a positive impact on an individual. In this review, stereotype lift was described in 1 article: white medical students reported feeling that they were better communicators than Asian medical students because of the stereotype of Asian medical students being poor communicators (Woolf et al. Citation2008). In contrast to stereotype lift, Shih et al. (Citation2012) described stereotype boost as an individual receiving a positive motivational arousal from a stereotype of people who were members of the ‘in’-group. In this review, stereotype boost was described in 2 articles. White medical students were positively impacted when exposed to socio-cultural cues that invoked positive stereotypes about demographic groups that they self-identified with (Beagan Citation2003; Woolf et al. Citation2008):

Perhaps I bond better with the students and the residents and the staff members just because I come from the same background as the other doctors do.… I’ve often felt – because I fit like a stereotyped white male – that patients might see me as a bit more trustworthy. A bit more what they'd like to see. Who they want to see. (Beagan Citation2003)

The basic premise of stereotype boost – an individual receiving a performance boost from a stereotype about a social group they identify with – was also described to occur among Asian medical students. The stereotype of ‘conscientious, hard-working, and bright’ was a driver for some Asian students to work harder than others around them (Woolf et al. Citation2008). The motivating factor for these Asian students was a pressure to avoid being labelled as an under-achiever (Woolf et al. Citation2008). Therefore, this stereotype invoked unpleasant motivational arousal.

Stereotype reactance

Kray et al. (Citation2001) described stereotype reactance as the phenomenon of individuals adopting or strengthening an attitude contrary to a stereotype. In this review, stereotype reactance was described in 3 articles (Bullock and Houston Citation1987; Erwin et al. Citation2002; Liebschutz et al. Citation2006). In these articles unpleasant motivational arousal was described to occur when individuals were exposed to stereotypes that denigrated a demographic group that they self-identified with. For example, Black and African American medical students felt motivated to work harder because they were explicitly aware that they were perceived to be intellectually inferior (Bullock and Houston Citation1987), and they did not want to settle for being average:

have to be 10 times better to get the same respect [as a White student] (Erwin et al. Citation2002)

The motivation to work hard was due to a pressure to prove to themselves that they belonged but was also fuelled by a distrust of the system surrounding them. There was also a resultant belief that they needed to ensure their own success and to protect themselves as best they could from punishment or reprisal (Liebschutz et al. Citation2006).

Stereotype masking

In this review, 5 articles described some minority ethnic medical students attempting to distance themselves from a given stereotype. They did this by either disconnecting from the identity linked to that stereotype (Bullock and Houston Citation1987; Roberts et al. Citation2008) or hiding the facets of their identity linked to that stereotype (Woolf et al. Citation2008; Claridge et al. Citation2018; Morrison et al. Citation2019). This phenomenon has been described to be akin to the identity threat described in the Queen B phenomenon related to gender stereotypes by Derks et al. (Citation2016). Appearing to be a form of stereotype masking, minority ethnic student felt as though they needed to be someone other than who they were:

felt pressure to become like [White medical students], to mingle in … to stop frequenting the minority office, to speak like them, act like them, play rugby. (Bullock and Houston Citation1987)

Minority ethnic students were also negatively impacted by trying to change how they spoke in order to try and seem more ‘like a [stereotypical White] doctor’ (Claridge et al. Citation2018). This pressure to fit in was linked to minority ethnic students feeling like they were not part of the accepted majority group, whether this was due to the clothes they wore (Woolf et al. Citation2008), their physical characteristics (Roberts et al. Citation2008), or a perception of appearing ‘foreign’ (Morrison et al. Citation2019).

Practical implications of this review

Adverse impacts from stereotyping may be reduced by training individuals in cultural humility (Tervalon and Murray-García Citation1998). The training of health professions learners to develop cultural humility across an undergraduate curriculum is challenging given all the other demands competing for their time and attention. Nevertheless, medical schools should ensure curricula are sufficiently diverse in terms of content – reflecting the identities of minority ethnic students when appropriate to do so – and create early opportunities for students from different groups to integrate in meaningful ways (Incision UK Collaborative, Citation2020). Structured dialogue groups involve individuals – health professions educators and learners – formally coming together, divulging information about themselves, and reflecting on their educational experiences in a non-judgmental setting (Burgess et al. Citation2010). Hearing from other individuals who are experience similar issues could also reduce an individual’s feeling of social isolation (Ma et al. Citation2020) and tackle the impact of stereotype masking which seems to be primarily driven by the feeling of being ‘the odd one out.’ Likewise, structured dialogue groups may also reduce stereotype threat experienced by minority ethnic students if similar stories of hardship are heard from individuals who do not belong to the group being stereotyped (Burgess et al. Citation2010). Structured dialogue groups may also facilitate the creation of allies from non-stereotyped groups, who empower stereotyped individuals to challenge misrepresentation or mischaracterisation (Beagan Citation2003). Demonstrating these behaviours among health professions educators is important for building trust with students from minority ethnic groups and decreasing both the adverse impacts of stereotypes and student’ pressure to disprove them (J. L. Bullock et al. Citation2020). Alongside creating this shared space, educators acting with integrity and in a manner that inspires the confidence of minority ethnic students to trust faculty and the wider system in general is also essential. This specific type of role-modelling remains one of the few interventions that reduces attributive ambiguity (Cohen et al. Citation1999).

Discussion

The findings from this review confirm that ethnicity-related stereotypes are portrayed in HPE literature () and the impact of stereotyping on medical students can be explained by several well-described phenomena in social psychology research: stereotype threat, stereotype reactance, attributional ambiguity, self-fulfilling prophecy, stereotype boost, stereotype lift and stereotype masking (). The review also highlights the profound impact of stereotypes resulted in individuals perceiving the need to change their thoughts, feelings, and behaviour when in social situations; in some cases, having to disidentify with themselves to maintain self-esteem in the face of judgement (J. Steele et al. Citation2002). The findings have implications for HPE, especially given that the curriculum is experienced differently by minority ethnic students, and educational outcomes also are significantly different compared to other groups of students (Woolf et al. Citation2013).

A number of ethnicity-related stereotypes were identified within HPE literature, both within and across different groups of students from Asian to Latinx to White individuals (). Some of these stereotypes – for example those surrounding communication and motivation to study the degree (Woolf et al. Citation2008; Morrison et al. Citation2019) – were centred around the context of medical education. These stereotypes aimed to group individuals that are highly heterogeneous based on one shared ethnic characteristic. This inevitably leads to stereotypes that neglect individual values that are critical for effective medical education and the development of clinical reasoning skills (Moyo et al. Citation2019). In contrast to the HPE specific stereotypes mentioned above, we also identified stereotypes for minority ethnic students (Bullock and Houston Citation1987; Lempp and Seale Citation2006) that have been applied to minority ethnic patients in the context of healthcare too (Van Ryn and Burke Citation2000). The context and culture of healthcare and education are different. There is no reason why ethnicity-related stereotypes about patients and students from minority ethnic groups would or should be the same. It is likely individuals were grouped together on their physical characteristic of skin colour – rather than the shared culture behind having that skin colour – and a generalisation was made that all individuals in this group shared a biological characteristic: a degree of intelligence. These stereotypes were therefore more likely to be race-based rather than ethnicity-related. Continuing to perpetuate stereotypes centred around race being a biological concept in HPE (Bullock and Houston Citation1987; Lempp and Seale Citation2006) risks medical students internalising these stereotypes and utilising them in their professional practice (Van Ryn and Burke Citation2000), which can lead to serious medical errors (Braun et al. Citation2007).

The findings in also underscore stereotypes do not exist solely for specific groups in HPE. This has implications beyond ethnicity. Stereotypes exist in HPE literature for other demographic characteristics, such as age (Jauregui et al. Citation2020), gender (Bleakley Citation2013), disability (Takakuwa Citation1998), and sexual orientation (Burke et al. Citation2015). However, it is unclear what the impacts of these non-ethnicity-related stereotypes are and how they interplay with the impacts of the stereotypes described in this review. A woman Asian medical student would be impacted by stereotypes about Asians and women depicted in HPE. However, these stereotypes could be contradictory: ‘poor communicator’(Woolf et al. Citation2008) versus ‘better communicator’(Tanne Citation2002) respectively. The combined effect of both stereotypes on the individual may be vastly different from the impact of each stereotype in isolation. Therefore, the current studies investigating the impact of ethnicity-related stereotypes on medical students have been insufficient. To continue with the example of gender, all individuals simultaneously belong to a gender and ethnic group. In non-HPE literature, the intersection of these categories has been shown not only to alter the impact of an ethnicity-related stereotype (Ghavami and Peplau Citation2013), but change the content of the stereotype itself (Eagly and Kite Citation1987; Schneider and Bos Citation2011). Future studies that investigate the impacts of ethnicity-related stereotypes in HPE through the lens of intersectionality theory (Cole and Zucker Citation2007) and social dominance theory (Sidanius and Pratto Citation1999) – both of which take into account that individuals belong to multiple demographic groups – are needed, and may yield vastly different results to that described in this review.

The above example involving gender also highlights positive stereotypes exist. As shows, positive ethnicity-related stereotypes are present in HPE literature (Beagan Citation2003; Woolf et al. Citation2008). Whilst positive stereotypes about White medical students were described to result in stereotype boost (Beagan Citation2003; Woolf et al. Citation2008), the same was not true for Asian medical students. This demonstrates the inherent issue with all stereotypes – even those that are seemingly complementary in their portrayal of members of a social group –, they rely on a categorisation process that inherently limits the ability to consider the distinctive individual being stereotyped (Wheeler and Fiske Citation2005). A growing body of evidence within non-HPE literature suggests that positive stereotypes can lead to harmful impacts for stereotyped individuals’ interpersonal and intergroup relationships (Czopp et al. Citation2015). Indeed, the stereotype of Asian medical students being ‘conscientious, hard-working, and bright’ placed stress on Asian medical students (Woolf et al. Citation2008). Such stereotypes have been found to negatively affect the ability of Asian students to ask for help from others (Gupta et al. Citation2011), and have been linked to students feeling angry or annoyed during group work (Siy and Cheryan Citation2013). Therefore, positive stereotypes may in their own way be contributing to the differential attainment among students of various ethnicities at medical school (Woolf et al. Citation2013). Undue pressure to perform could place students at risk of underperforming: ‘choking under pressure’(Wilkinson et al. Citation2016); unwillingness to seek help could be impeding the formation of peer support networks that are essential for optimising academic achievement (Tinto Citation1997); and being frustrated during group work could lead to behaviours that are not conducive to effective learning (Iqbal et al. Citation2016).

A limitation of this review is that it may not only describe ethnicity-related stereotypes, but stereotypes rooted in race. The framing of race-based stereotypes as ethnicity-related stereotypes risks removing some of the truth from the situation. This can only be tackled effectively by future research being more mindful of the distinctions between culture, ethnicity and race (Hamer et al. Citation2020). For example, the USA articles that used ‘Black’ as a term tended to contain stereotypes that were highly suggestive of being linked to race (Bullock et al. Citation2020; Bullock and Houston Citation1987), but there were exceptions to this rule (Liebschutz et al. Citation2006). Another limitation of this review is that the various impacts described may not be solely due to the ethnicity-related stereotypes. For example, ethnic minority students not studying for exams (Kupiri Ackerman-Barger et al., Citation2015) could be driven by structural inequity in how exams are conducted (Wass et al. Citation2003). Similarly, ethnic minority students feeling a pressure to fit in could be due to the structural factors that have contributed to high levels of imposter syndrome among this demographic group (Bravata et al. Citation2020). A further limitation of this review is that the majority of HPE literature around ethnicity-related stereotypes and their impact on medical students is based on work conducted in the USA or the UK. Stereotypes exist in other non-USA and UK HPE contexts, for example Dutch versus Turkish/Moroccan stereotypes that are much more prevalent in the Netherlands (Padgett Citation2010) were not explored in this review. This review also did not identify social psychology concepts for explaining performance gains in Asian students due to stereotypes, given the underlying psychological phenomenon responsible for these gains were negative and linked to pressure, rather than due to positive feelings linked to stereotype boost (Shih et al. Citation2012). Finally, this review only identified 14 articles for inclusion. This paucity of literature seems reflective of there not being much published on this topic. There is a need for additional primary research to be conducted in this area.

Conclusion

One of the drivers for undertaking this review was the evidence suggesting stereotyping was likely contributing to the achievement or attainment gap affecting minority ethnic students. The findings from this research confirm that the impact from stereotyping may not just be on assessment, but across all teaching and learning activities at medical school. Although stereotype threat has long been reported (Woolf et al. Citation2008), the other consequences of stereotyping described in also affect the lived experiences of minority ethnic students on a daily basis. By understanding the types of stereotypes that exist and making sense of their impacts through the lens of various social psychological theories, educators can ameliorate negative outcomes. A key recommendation is for educators to be allies to their learners. This requires researchers and educators – who hold influence in setting agendas and developing recommendations – to continuously evaluate the assumptions, including ethnicity-related stereotypes, they possess about learners, and appropriately amend their attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours towards them.

Authors’ contributions

SB and RP contributed to the conceptualising of this review. SB, CTB, YGB, AC, AA, HK, and NB conducted the review of the literature. SB wrote the first draft of this paper. RP, CTB, YGB, AC, AA, and NB made critical revisions of this paper. All authors have approved the final manuscript and are willing to take responsibility for the content.

Glossary

Minority ethnic students: Here refers to students from a different ethnic group to the dominant ethnic group in the country in which they live, for the example individuals who are White British form the dominant ethnic group in the United Kingdom (UK).

Stereotypes: Are oversimplified beliefs that homogenise all persons in a group into a single characteristic or descriptor.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.7 KB)Additional information

Notes on contributors

Soham Bandyopadhyay

Soham Bandyopadhyay, MA, BM BCh, Oxford University Global Surgery Group, Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Oxford, UK.

Conor T. Boylan

Conor T Boylan, MBChB, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK.

Yousif G. Baho

Yousif G Baho, MSc, Hull York Medical School, University of Hull, Kingston Upon Hull, UK & University of York, York, UK.

Anna Casey

Anna Casey, MSc, Brighton and Sussex Medical School, Brighton, UK.

Aqua Asif

Aqua Asif, BSc (Hons), Leicester Medical School, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK.

Halimah Khalil

Halimah Khalil, BMedSci, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK.

Nermin Badwi

Nermin Badwi, MBBS, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt.

Rakesh Patel

Rakesh Patel, MBChB, MMEd, MD, Medical Education Centre, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK.

References

- Bargh JA, Chartrand TL. 1999. The unbearable automaticity of being. Am Psychol. 54(7):462–479.

- Beagan BL. 2003. Is this worth getting into a big fuss over? Everyday racism in medical school? Med Educ. 37(10):852–860.

- Bleakley A. 2013. Gender matters in medical education. Med Educ. 47(1):59–70.

- Braun L, Fausto-Sterling A, Fullwiley D, Hammonds EM, Nelson A, Quivers W, Reverby SM, Shields AE. 2007. Racial categories in medical practice: How useful are they? PLoS Med. 4(9):e271.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3(2):77–101.

- Bravata DM, Watts SA, Keefer AL, Madhusudhan DK, Taylor KT, Clark DM, Nelson RS, Cokley KO, Hagg HK. 2020. Prevalence, predictors, and treatment of impostor syndrome: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 35(4):1252–1275.

- Bullock JL, Lockspeiser T, Del Pino-Jones A, Richards R, Teherani A, Hauer KE. 2020. They don’t see a lot of people my color: a mixed methods study of racial/ethnic stereotype threat among medical students on core clerkships. Acad Med. 95(11S):S58–S66.

- Bullock SC, Houston E. 1987. Perceptions of racism by black medical students attending white medical schools. J Natl Med Assoc. 79(6):601–608.

- Burgess DJ, Warren J, Phelan S, Dovidio J, van Ryn M. 2010. Stereotype threat and health disparities: what medical educators and future physicians need to know. J Gen Intern Med. 25 (S2):169–177.

- Burke SE, Dovidio JF, Przedworski JM, Hardeman RR, Perry SP, Phelan SM, Nelson DB, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, Van Ryn M. 2015. Do contact and empathy mitigate bias against gay and lesbian people among heterosexual first-year medical students? A report from the medical student change study. Acad Med. 90(5):645–651.

- Charlesworth TES, Banaji MR. 2019. Patterns of implicit and explicit attitudes: I. long-term change and stability from 2007 to 2016. Psychol Sci. 30(2):174–192.

- Claridge H, Stone K, Ussher M. 2018. The ethnicity attainment gap among medical and biomedical science students: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 18(1):325.

- Cohen GL, Steele CM, Ross LD. 1999. The Mentor’s dilemma: providing critical feedback across the racial divide. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 25(10):1302–1318.

- Cole ER, Zucker AN. 2007. Black and white women’s perspectives on femininity. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 13(1):1–9.

- Crocker J, Voelkl K, Testa M, Major B. 1991. Social stigma: the affective consequences of attributional ambiguity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 60(2):218–228.

- Czopp AM, Kay AC, Cheryan S. 2015. Positive stereotypes are pervasive and powerful. Perspect Psychol Sci. 10(4):451–463.

- Carthron DL. 2007. A splash of color: increasing diversity among nursing students and faculty. J Best Pract Health Prof Divers. 1(1):13–23.

- Derks B, Van Laar C, Ellemers N. 2016. The queen bee phenomenon: Why women leaders distance themselves from junior women. Leadership Quar. 27(3):456–469.

- Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. 2005. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 10(1):45–53.

- Eagly AH, Kite ME. 1987. Are stereotypes of nationalities applied to both women and men? J Pers Soc Psychol. 53(3):451–462.

- Erwin DO, Henry-Tillman RS, Thomas BR. 2002. A qualitative study of the experiences of one group of African Americans in pursuit of a career in academic medicine. J Natl Med Assoc. 94(9):802–812.

- Esmail A, Nelson P, Primarolo D, Torna T. 1995. Acceptance into medical school and racial discrimination. BMJ. 310(6978):501–502.

- Eva KW. 2008. On the limits of systematicity. Med Educ. 42(9):852–853.

- Ghavami N, Peplau LA. 2013. An intersectional analysis of gender and ethnic stereotypes. Psychol Women Quart. 37(1):113–127.

- Given L. 2012. The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Transferability. 2012:N464.

- Grant MJ, Booth A. 2009. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 26(2):91–108.

- Gupta A, Szymanski DM, Leong FTL. 2011. The “model minority myth”: internalized racialism of positive stereotypes as correlates of psychological distress, and attitudes toward help-seeking. Asian Am J Psychol. 2(2):101–114.

- Padgett G. 2010. Culture clash: Moroccan and Turkish Muslim Populations in the Netherlands. https://www.beyondintractability.org/casestudy/culture-clash-moroccan-and-turkish-muslim-populations-netherlands.

- Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, Eng E, Day SH, Coyne-Beasley T. 2015. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review Yo Veo and Yo Veo Salud View project Migrant Mothers in Shanghai View project. Am J Public Health. 105(12):2588–2588.

- Hamer K, McFarland S, Czarnecka B, Golińska A, Cadena LM, Łużniak-Piecha M, Jułkowski T. 2020. What is an “Ethnic Group” in ordinary people’s eyes? Different ways of understanding it among American, British, Mexican, and Polish Respondents. Cross-Cultural Res. 54(1):28–72.

- Haslam SA, Turner JC, Oakes PJ, Reynolds KJ, Doosje B. 2009. From personal pictures in the head to collective tools in the world: how shared stereotypes allow groups to represent and change social reality. Stereotypes as Explanations. 2009:157–185.

- Incision UK Collaborative. 2020. Global health education in medical schools (GHEMS): a national, collaborative study of medical curricula. BMC Med Educ. 20(1):389.

- Iqbal M, Velan GM, O’Sullivan AJ, Balasooriya C. 2016. Differential impact of student behaviours on group interaction and collaborative learning: medical students’ and tutors’ perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 16(1):217.

- Jacoby LL, Lindsay DS, Toth JP. 1992. Unconscious influences revealed: attention, awareness, and control. Am Psychol. 47(6):802–809.

- Jauregui J, Watsjold B, Welsh L, Ilgen JS, Robins L. 2020. Generational ‘othering’: the myth of the Millennial learner. Med Educ. 54(1):60–65.

- Eligon J. 2020. A debate over identity and race asks, are African-Americans ‘Black’ or ‘black’? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/26/us/black-african-american-style-debate.html.

- Kaldis B. 2013. Encyclopedia of philosophy and the social sciences. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications.

- Isaac K. 2019. Lifting as we climb: the development of a support group for underrepresented minority medical students. Group. 43:101–112.

- Kray LJ, Thompson L, Galinsky A. 2001. Battle of the sexes: gender stereotype confirmation and reactance in negotiations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 80(6):942–958.

- Ackerman-Barger K, Valderama-Wallace C, Latimore D, Drake C. 2016. Stereotype threat susceptibility among minority health professions students. J Best Pract Health Prof Divers. 9(2):1232–1246.

- Ackerman-Barger K, Bakerjian D, Latimore D. 2015. How health professions educators can mitigate underrepresented students’ experiences of marginalization: stereotype threat, internalized bias, and microaggressions. J Best Pract Health Prof Divers. 8(2):1060–1070.

- Lempp H, Seale C. 2006. Medical students’ perceptions in relation to ethnicity and gender: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 6:17.

- Liebschutz JM, Darko GO, Finley EP, Cawse JM, Bharel M, Orlander JD. 2006. In the minority: black physicians in residency and their experiences. J Natl Med Assoc. 98(9):1441–1448.

- Lim GHT, Sibanda Z, Erhabor J, Bandyopadhyay S. 2021. Students’ perceptions on race in medical education and healthcare. Perspect Med Educ. 10(2):130–134.

- Ma R, Mann F, Wang J, Lloyd-Evans B, Terhune J, Al-Shihabi A, Johnson S. 2020. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing subjective and objective social isolation among people with mental health problems: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 55(7):839–876.

- Macrae CN, Milne AB, Bodenhausen GV. 1994. Stereotypes as energy-saving devices: a peek inside the cognitive toolbox. J Pers Soc Psychol. 66(1):37–47.

- Wheeler ME, Fiske ST. 2005. Controlling racial prejudice: social-cognitive goals affect amygdala and stereotype activation. Psychol Sci. 16(1):56–63.

- McGarty C, Spears R, Yzerbyt VY. 2009. Conclusion: stereotypes are selective, variable and contested explanations. In Stereotypes as Explanations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; p. 186–199.

- Mcgarty C, Yzerbyt VY, Spears R. 2002. Stereotypes as explanations: the formation of meaningful beliefs about social groups. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McManus IC, Richards P, Winder BC, Sproston KA, Styles V. 1995. Medical school applicants from ethnic minority groups: identifying if and when they are disadvantaged. BMJ. 310(6978):496–500.

- Morrison N, Machado M, Blackburn C. 2019. Student perspectives on barriers to performance for black and minority ethnic graduate-entry medical students: a qualitative study in a West Midlands medical school. BMJ Open. 9(11):e032493.

- Moyo M, Shulruf B, Weller J, Goodyear-Smith F. 2019. Effect of medical students’ values on their clinical decision-making. J Prim Health Care. 11(1):64–74.

- Norman G, Eva KW. 2018. Quantitative research methods in medical education. In Understanding Medical Education. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; p. 405–425.

- Razack S, Philibert I. 2019. Inclusion in the clinical learning environment: building the conditions for diverse human flourishing. Med Teach. 41(4):380–384.

- Roberts JH, Sanders T, Wass V. 2008. Students’ perceptions of race, ethnicity and culture at two UK medical schools: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 42(1):45–52.

- Schneider MC, Bos AL. 2011. An exploration of the content of stereotypes of black politicians. Polit Psychol. 32(2):205–233.

- Shih MJ, Pittinsky TL, Ho GC. 2012. Stereotype boost: positive outcomes from the activation of positive stereotypes. – PsycNET. In: Oxford University Press, editors. Stereotype threat: theory, process, and application. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 141–156.

- Sidanius J, Pratto F. 1999. Social dominance an intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. http://www.cup.cam.ac.ukhttp//www.cup.org.

- Siy JO, Cheryan S. 2013. When compliments fail to flatter: American individualism and responses to positive stereotypes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 104(1):87–102.

- Steele CM, Aronson J. 1995. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J Pers Soc Psychol. 69(5):797–811.

- Steele J, James JB, Barnett RC. 2002. Learning in a man’s world: examining the perceptions of undergraduate women in male-dominated academic areas. Psychol Women Quart. 26(1):46–50.

- Takakuwa KM. 1998. Coping with a learning disability in medical school. JAMA. 279(1):81.

- Tanne JH. 2002. Women doctors are better communicators. BMJ. 325(7361):408–408.

- Tervalon M, Murray-García J. 1998. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 9(2):117–125.

- Tinto V. 1997. Classrooms as communities. J Higher Educ. 68(6):599–623.

- Van Ryn M, Burke J. 2000. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 50(6):813–828.

- Walton GM, Cohen GL. 2003. Stereotype lift. J Exp Soc Psychol. 39(5):456–467.

- Wass V, Roberts C, Hoogenboom R, Jones R, Vleuten C. V d. 2003. Effect of ethnicity on performance in a final objective structured clinical examination: qualitative and quantitative study. BMJ. 326(7393):800–803.

- Watson S, Appiah O, Thornton CG. 2011. The effect of name on pre-interview impressions and occupational stereotypes: the case of black sales job applicants. J Appl Soc Psychol. 41(10):2405–2420.

- Wilkinson TJ, McKenzie JM, Ali AN, Rudland J, Carter FA, Bell CJ. 2016. Identifying medical students at risk of underperformance from significant stressors. BMC Med Educ. 16(1):9.

- Woolf K, Cave J, Greenhalgh T, Dacre J. 2008. Ethnic stereotypes and the underachievement of UK medical students from ethnic minorities: qualitative study. BMJ. 337(7670):a1220–615.

- Woolf K, Mcmanus IC, Potts HWWW, Dacre J. 2013. The mediators of minority ethnic underperformance in final medical school examinations. Br J Educ Psychol. 83(Pt 1):135–159.