Abstract

Background

A rigorous learning needs assessment (LNA) is a crucial initial step in the Continuing Professional Development (CPD) process. This scoping review aimed to collate, summarize, and categorize the reported LNA approaches adopted to inform healthcare professional CPD and highlight the gaps for further research.

Method

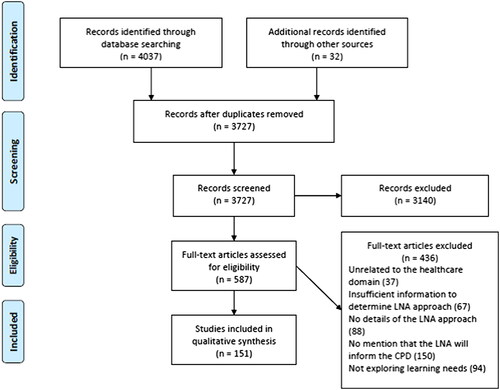

In August 2020, nine bibliographic databases were searched for studies conducted with any health professional grouping, reporting the utilized LNA to inform CPD activities. Two reviewers independently screened the articles for eligibility and charted the data. A descriptive analytical approach was employed to collate, summarize, and categorize the literature.

Results

151 studies were included in the review; the majority adopted quantitative methods in the form of self-assessment surveys. Mixed-methods approaches were reported in only 35 studies. Descriptions of LNA development lacked detail of measures taken to enhance their rigor or robustness.

Discussion

These findings do not reflect recommendations offered by the CPD literature. Further investigations are required to evaluate more recently advocated LNA approaches and add to their limited evidence-base. Similarly, the existing support afforded to CPD developers warrants further study in order to identify the necessary resource, infrastructure and expertise essential to design and deliver effective CPD programs.

Introduction

Within the healthcare professions, the need for Continuing Professional Development (CPD) is well-established (Sargeant et al. Citation2018; Sherman and Chappell Citation2018; Ramani et al. Citation2019). CPD is defined as any learning outside of undergraduate education or postgraduate training that helps you maintain and improve your performance. It covers the development of your knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviours across all areas of your professional practice. It includes both formal (e.g. workshops) and informal learning activities (e.g. workplace learning) (Council Citation2012). The literature discusses the importance of CPD to support professional competence, remains updated with advances in practice, and addresses priorities identified through health need assessments (HNA) (Filipe et al. Citation2014; Gazzard Citation2016; Filipe et al. Citation2018; Sargeant et al. Citation2018). Further, the professional requirement to complete CPD supports the notion that improving healthcare practice is underpinned by continuing education and encourages the workforce to access developmental opportunities and address personal professional development as well as local health care needs (Gazzard Citation2016; Albarqouni et al. Citation2018; Filipe et al. Citation2018; Ramani et al. Citation2019).

Practice points

CPD developers are encouraged to review existing recommendations in the CPD literature to determine the optimal approach for constructing an effective learning needs assessment.

CPD developers are encouraged to seek the involvement of practice-based colleagues including senior management and line managers to access and incorporate practice-based data that can be utilized to assess competence, performance, and practice outcomes.

CPD developers should seek engagement opportunities with health care professionals who may champion the need for CPD activities that are specifically targeted to improving patient care and health outcomes.

Recent systematic reviews in the field of CPD have focused on the content (Albarqouni et al. Citation2018; Micallef and Kayyali Citation2019), specific delivery approaches and perceived effectiveness (Berndt et al. Citation2017; Phillips et al. Citation2019), and participants’ experiences (Allen et al. Citation2019; Vázquez-Calatayud et al. Citation2021). An area of CPD that has received less attention is strategies to comprehensively identify CPD needs. This is in contrast to the well-defined approaches adopted in conducting HNA whereby health priorities are determined and evaluated through systematic and comprehensive analysis of available data (Tobi Citation2016; East et al. Citation2018).

A rigorous learning needs assessment (LNA) is a crucial step in the educational and training process (Thampy Citation2013; Pilcher Citation2016). It can be planned or opportunistic and it could be done through formal or informal methods (Grant Citation2002). LNA is defined as a systematic approach to examine what is needed to be learned by either individuals or a group. It involves defining the purpose, design and dissemination, and the use that will be made of the findings for any formal or informal educational activity (Hauer and Quill Citation2011; Thampy Citation2013; Pilcher Citation2016). A LNA driven approach is more likely to lead to a change in practice (Grant and Stanton Citation1999), largely as a result of the learning being directly linked to personal and practice needs (Gupta Citation2011; Hauer and Quill Citation2011).

Diverse LNAs approaches have been advocated for the purpose of informing healthcare CPD activities (Gupta Citation2011; Hauer and Quill Citation2011; Pilcher Citation2016; Grant Citation2017). Grant et al. attempted to elucidate this issue in classifying potential methods for conducting both formal and informal CPD needs assessment that may be either planned or opportunistic. The authors recommended that a combination of methods should be adopted. They advised that the informal and opportunistic approaches such as self-reflection, peer-observation, and critical incident review should be used as the basis for ongoing planning and action. Thereafter, these findings should be integrated with more formal approaches including audit, surveys, morbidity patterns, to inform structured and planned education and training programs aimed at improving clinical practice and meeting organizational goals (Grant Citation2017).

Despite the relative importance placed upon LNAs to assist with and enhance planning of educational activities, a search of the peer-reviewed literature and indeed guidance provided by CPD accrediting bodies fails to provide explicit guidance on how the recommended practices can be translated into practical steps to optimally conduct LNAs (Van Hoof et al. Citation2015; Pocock and Rezaeian Citation2016). In light of this, the purpose of this review was to collate, summarize, and categorize the reported LNA approaches adopted to inform healthcare professional CPD and highlight the gaps for further research.

Methods

This review was conducted systematically and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Shamseer et al. Citation2015) and Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewers’ Manual (Peters et al. Citation2015). The protocol was registered online on the OSF website (registration number: 97g4w) (Zachariah Nazar et al.).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Primary research studies of any design conducted with any health professional grouping which reported details of the approach employed for conducting a LNA to inform CPD activities, were included. Studies had to be published in English and published from database inception until the end of August 2020. Opinion pieces, commentaries, editorials, perspectives, calls for changes, and other studies where no actual LNA was developed or administered were excluded; as were studies where the LNA was not designed for the purpose of informing healthcare professional CPD.

Search strategy

The following databases and search engines were included in the review: PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (IPA), APA PsycArticles, and Google Scholar. Studies published in grey literature were retrieved through OpenGrey and Grey Literature Report. Databases were searched for title and abstract using the Boolean operators AND OR combined with truncation and phrase searches, as follows (PubMed).

(Professional education [MeSH] OR “continuing professional development” OR “professional development” OR “continued professional development”) AND (Needs assessment [MeSH] OR “training needs assessment” OR “learning needs assessment” OR “needs analysis”) AND (Health personnel [MeSH] OR clinician OR “healthcare practitioner”).

Reference lists of articles included in full text screening were manually searched to locate additional relevant articles that were not identified through the database search.

Study selection

Results were exported to EndNote X8® (2019 Clarivate), duplicates removed, and the remaining articles imported to Rayyan Qatar Computing Research Institute (QCRI) web application (Ouzzani et al. Citation2016). Two reviewers (L. N. and T. H.) independently screened the titles, abstracts and full papers according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, with a third reviewer (Z. N.) consulted in cases of non-agreement.

Data extraction and synthesis

A data extraction tool was developed through consensus of the research team where the key study characteristics and variables that aligned to the research question were discussed and agreed upon. Six of the authors then independently worked in three teams (each with two researchers) to independently extract the information from the first 10 included studies, thereafter, a meeting was conducted to ensure their approach was consistent, and the data extraction tool was refined through further consensus. The remaining studies were evenly allocated amongst the three groups to extract the relevant information. Data extraction of each article was performed independently by both researchers in each group, who met regularly to discuss their findings and attempt to reach consensus. In cases where consensus could not be reached, a second group of researchers were included in the discussions. Final data that were extracted from each study included key characteristics (year of publication, location, setting, study participants), methods adopted to perform LNA (qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods), and domains assessed in the LNA (knowledge, skill, competency, attitude).

A descriptive analytical approach was employed to collate, summarize, and categorize the literature, including a numerical count of study characteristics (quantitative) and thematic analysis (qualitative). In the first step of this process, studies were grouped according to the method adopted to perform the LNA and separate Excel® spreadsheets and tables produced. The tabulated data were subjected to content analysis according to the steps as described by Erlingsson and Brysiewicz. This involved initially familiarizing oneself with the data and the hermeneutic spiral; then dividing up the text into meaning units and subsequently condensing these meaning units. Thereafter, codes were formulated including, the geographical distribution of articles, study participants; and research methods adopted. Finally, categories and themes were developed including: methods for conducting LNA; the reported robustness/rigor of LNAs; the domains assessed using the LNA and their subsequent analysis, interpretation and utility (Erlingsson and Brysiewicz Citation2017).

Results

The presentation of the results is as follows: initially, an overview and descriptive summary of the included studies is presented. Thereafter, the identified themes are presented, including: (1) methods adopted for conducting LNA; (2) the reported robustness/rigor of LNAs; (3) the domains assessed using the LNA and their subsequent analysis, interpretation and utility.

Descriptive summary of the included studies

This review included 151 studies (). Studies were published between 1984 and 2020 with an even distribution of publication frequency. The majority of the studies were conducted in North America (63, 41.7%) and Europe (51 studies 33.7%).

Secondary care settings (39 studies, 25.8%), home and community care (28 studies 18.5%) and primary care settings (26 studies 17.2%) were the most common settings in which the LNA was conducted.

Studies investigated the learning needs of a wide range of healthcare professionals and other stakeholders, with less than half of the studies investigating perspectives from more than one stakeholder (62 studies, 41.1%). In most cases, multi-stakeholder investigations were conducted by administering an adapted version of the original LNA instrument to either line managers, directors, or supervisors. Few studies (2 studies; 1.32%) described the use of objective and structured peer-evaluations. However, where discrepancies between stakeholders were recorded in the data, the ensuing discussion failed to comment on how they were managed.

The majority of studies reported the need assessment from the perspective of clinicians (either alone or in a multi-stakeholder study) (144 studies 95.4%), and few studies examined the perspectives of patients or caregivers (9 studies 6.0%). Further, several tools were specifically designed to capture the needs of clinicians as reported by managers or other senior staff.

The sample size and response rate varied considerably in the included studies. Sample size was highly variable and was influenced by the setting in which the needs assessment was conducted. Settings ranged from single center settings consisting of as few as 11 participants to nationwide investigations of multiple clinicians with a potential sample size of 14,000 participants.

A summary of the characteristics of the included studies are presented in .

Table 1. Summary of the characteristics of the included studies (n = 151).

Methods adopted for conducting LNA

provides an overview of the reported methods adopted for conducting the LNA. The majority adopted quantitative methods (92 studies; 60.9%), with mixed-methods (35 studies; 23.2%) and qualitative methods (16 studies, 10.6%) used less frequently. The remaining 8 studies used various data sources as the basis of the LNAs, these included analysis of questions from routine practice, artificial intelligence, and clinicians’ reflections.

Table 2. Methods adopted for conducting LNA.

The most commonly used methods to investigate learning needs were surveys alone (89 studies; 58.9%). Moreover, of the 35 studies, which sought to investigate the learning needs using mixed-methods, the most frequent approach was the use of surveys and a second method (individual interviews, focus group or modified Delphi technique).

The majority of mixed-methods studies were performed in an exploratory sequential manner, where the initial method required subject experts to identify measurable variables that could be measured quantitatively in the survey phase. A smaller number of studies adopted a sequential explanatory design, which recruited survey respondents to interpret and examine in more detail survey findings.

The reported robustness/rigor of LNAs

A large number of studies (63 studies; 41.7%) provided some detail regarding the development and design of the LNA tool, however, in most cases, descriptions lacked adequate detail to appraise the scientific rigor or robustness adopted.

Studies utilizing a questionnaire mentioned that questionnaire items were derived from consultation with subject experts, or a review of the literature, or adapting a previously published tool. However, little description of these processes was provided. For example, the number and background of included subject experts; the extent of the literature review performed; and steps taken to enhance questionnaire rigor or robustness were rarely reported.

Similarly, studies adopting qualitative interviews (either individual or focus groups) often mentioned the employment of thematic analysis to analyze transcriptions, yet it was very rare that description beyond this was included, for example details of the process followed to code interviews, generate themes, and steps taken to enhance the trustworthiness of the derived data.

Further details of data extracted, including the described process of all reported LNA development, which was notable by the apparent lack of detail, are included in the Online Appendices.

Domains assessed using the LNA and their subsequent analysis, interpretation, and utility

LNAs included assessment of various domains in their target audience. Self-reported domains such as knowledge, skill, competence, performance, attitude, and confidence were most frequently assessed. provides a full list of the domains that were assessed.

Table 3. The reported domains assessed in the needs assessment tools.

Studies were of four types: (1) one method used to assess a single domain; (2) mixed-methods used to assess a single domain; (3) one method was used to assess multiple domains (e.g. a survey to assess knowledge and attitude); (4) mixed-methods were used to assess multiple domains (e.g. a survey and interviews to assess both knowledge and attitude).

Among survey studies, the vast majority were self-reporting assessments of perceived knowledge, skill, attitude, or performance (69 studies; 77.5%), followed by self-administered objective knowledge-based assessment (13 studies; 14.6%). Self-assessment of the aforementioned domains was consistently the most common perspective captured throughout all methods except chart audits.

Few studies attempted to incorporate other sources of data into the LNA, examples included: audit-derived data, analysis of questions from routine practice, artificial intelligence, and personal reflections (further details may be found in the Online Appendices).

Across all the domains that were assessed, it became evident that there was an inconsistent understanding of reporting the data attained from the LNA. ‘Interest’ or ‘confidence’ in educational topics, and ‘gaps’ in knowledge were used interchangeably in the discussion of LNA results.

Furthermore, studies reported that LNA data would subsequently be analyzed and used to inform future CPD content and delivery. However, only a minority of studies provided any detail of how the LNA data had been utilized in such a way to inform subsequent activities.

Discussion

This review successfully provides insight into the landscape of how LNAs for healthcare CPD are designed, administered, and utilized.

The 151 studies included is indicative of the extensive level of interest and research in the CPD domain. The key findings of this review are as follows:

diverse methods are adopted in conducting LNAs, however surveys are by far the most utilized, with mixed-methods approaches less frequently adopted;

there is a high prevalence of LNAs that are self-administered providing self-reported information;

there is considerable diversity of domains assessed in the LNAs, and a notable inconsistency in their interpretation and reporting;

deficiencies in the reporting of the development and administration of LNAs made determining the robustness or rigor of the subsequent data challenging.

Overall, these findings indicated a lack of studies attempting to adopt the recommended approaches stipulated in the CPD literature in conducting and/or reporting LNAs.

The ensuing paragraphs attempt to interpret each of the above findings in the context of the existing literature.

Methods adopted for conducting LNA

LNA surveys offer advantages with the potential to reach a large group of learners and gain a wider perspective (Grant Citation2017), however, the use of multiple methods to fully identify LNA have been advocated in the literature.

As far back as 1998, Lockyer (Citation1998) recommended the use of multiple techniques to provide further clarification and confirmation of LNA data, subsequent studies have made consistent recommendations (Amery and Lapwood Citation2004; Colthart et al. Citation2008; Grant Citation2017). Mixed-method approaches, although more time-consuming and logistically challenging to administer, offer greater breadth and depth of understanding and corroboration, whilst also facilitating the opportunity to clarify potential contradictions (Lockyer Citation1998; Grant Citation2017).

Moreover, Grant (Citation2017) offers recommendations describing the LNA methods that complement one another when applied in a mixed-method design, yet this review yielded very few studies following these recommendations.

The findings from this review are also notable for the lack of reported studies that detailed LNAs delivered through peer-evaluation, in which a colleague or mentor observes and evaluates the individual performing in their job. This is despite advocacy for this approach (Evans et al. Citation2004; Grant Citation2017) and emerging evidence of its potential benefit in recognizing gaps in skills and professional behaviors (Wenghofer et al. Citation2006; Engelmann Citation2016; Tai and Adachi Citation2017). Even though this approach was not captured, it is likely that the approach is used in some form in health systems that conduct periodic performance appraisals of healthcare staff.

Self-administered and self-reporting LNA

In the most part, the reported LNAs largely relied upon the learner’s ability to accurately judge their own needs. For example, some questionnaires included items to measure perceived importance of competencies, others assessed relevancy of skills, need for training, or confidence in applying skills.

Self-assessment is an integral approach to most appraisal systems (Association Citation2004) and it is advocated as an important aspect of personal professional behavior by many regulatory bodies (American Medical Association, United Kingdom Nursing and Midwifery Council, The European Council of Medical Orders) and those developing outcomes for healthcare students (UK General Pharmaceutical Council, General Medical Council). However, it may not reflect the actual unmet learning and practice needs nor align to organizational goals (Kruger and Dunning Citation1999; Davis et al. Citation2006).

According to Gaspard and Yang, several factors influence how healthcare professionals perceive their performance of a specific task and prioritize their learning gaps. These influences may include a special interest in a particular task, motivation to undertake CPD, and satisfaction with the unit management (Gaspard and Yang Citation2016). Likewise, Kruger and Dunning postulate that self-assessment and self-evaluation of competency often results in an overestimation of their skills (Kruger and Dunning Citation1999).

It has been advocated that LNAs utilizing self-assessments, should seek a second perspective to enhance the validity of the data by cross-checking findings (Hicks and Hennessy Citation1997; Colthart et al. Citation2008). The review identified only 62 studies which sought to investigate the learning needs from the perspective of more than one stakeholder. Second, there is evidence that accuracy of self-assessment can be enhanced through benchmarking and increasing the learners’ awareness of what constitutes best practice to facilitate a comparison (Bachman Citation2000; Colthart et al. Citation2008). The review identified only a small number of studies to adopt this approach.

Diversity of domains

This review showed a significant diversity in the domains being assessed (including knowledge, skill, competency, performance, attitude, and confidence), where self-reporting questions were predominantly utilized. A minority of studies described the employment of LNA constructed of objective items. The CPD literature advocates for inclusion of objective measures, so that the LNAs may be re-administered periodically to evaluate participants’ learning and refine learning activities (Norman et al. Citation2004; De Lusignan et al. Citation2005; Davis et al. Citation2006; Colthart et al. Citation2008).

A 2018 study by Sargeant et al. argues that competency-based CPD provides greater focus on health needs and patient outcomes. Thus, LNAs should utilize multiple data sources to assess competence, performance and practice outcomes as well as integrating peer feedback. The authors suggest that such an approach will reflect the health needs of the patients or communities that are relevant to the healthcare professional’s scope of practice, and are more likely to identify and address areas for improvement (Sargeant et al. Citation2018).

The inconsistent way in which LNA data were interpreted suggested that authors held a poor understanding of the differences between domains and how each can be optimally assessed. This trend has been reported elsewhere in the literature, whereby authors have inaccurately discussed self-reported measures, as actual measures, for example self-perceived competence versus actual competence (Colthart et al. Citation2008; Berger Citation2019).

The reason for this confusion is unclear; the literature proposes a comprehensive framework of possible outcome measures of CPD activities to guide CPD developers (Wallace and May Citation2016) but similar comprehensive frameworks to inform the development of LNAs is lacking. offers a summary of the specific domains that were assessed in the included studies. The table may provide useful insight for further research.

Reporting of LNA development and administration

The reporting deficiencies which made the robustness or rigor of the LNA data collection tools challenging to determine is not a novel finding. In a 2008 systematic review investigating self-assessment in healthcare profession education; methodological issues including inadequate information on sampling strategies and insufficient reporting of methods and analysis were highlighted (Colthart et al. Citation2008). This review found that surveys were the most frequently utilized LNA, however, designing an effective survey tool requires expertise and testing to assure validity and reliability; additionally, reporting on such studies should include detail of specific items in order to draw accurate conclusions.

This review also reveals that self-assessment was commonly used, however, developing a set of self-assessment questions that contributes valid and practical data requires careful planning, psychometric tests and cognitive interviews may be necessary, as well as stakeholder consensus (Woolley et al. Citation2006; Karabenick et al. Citation2007; Joly et al. Citation2018). Such steps were not reported in most studies included in the review. Indeed, Berger et al. argued that cognitive interviewing can help determine the degree to which self-report items are interpreted as needed, and thus the degree to which scale items contribute to evidence of construct validity (Berger and Karabenick Citation2016).

The consequences of these issues can be speculated, however, it is well documented that well designed and executed LNAs can provide rich insight of the learning and practice gaps of targeted learners to develop focused education and training programs (Gupta Citation2011; Hauer and Quill Citation2011; Grant Citation2017). Cook et al. offer a practical introduction to the validation of assessments in medical education and may be a valuable guide for CPD developers (Cook et al. Citation2015).

It is likely that the additional resource, time, and higher level of complexity associated with designing and executing LNAs that are multifaceted and underpinned with scientific rigor/robustness deterred CPD developers.

Strengths & weaknesses

To our knowledge, this is the first review that includes LNA studies for all healthcare professionals and encompasses all LNA approaches; other reviews have targeted a single healthcare profession or a specific LNA approach.

It is important to note that the majority of studies were conducted in Europe and North America, where health systems and supporting infrastructure are likely to be significantly different to other settings. Thus, the potential generalizability and transferability of the findings may be considered a limitation of this study. It is possible that limiting the search to studies available in the English language and only primary research studies may have excluded relevant studies including those from other geographical regions.

Further research and recommendations

Despite the recent CPD literature offering recommendations for LNA development, this review has demonstrated few studies in which proposed strategies for LNA design have been fully adopted.

This raises the important question as to why there appear to be limited studies reporting on and evaluating the more recently advocated LNA approaches. In order to accurately and comprehensively answer this question, further investigation into the contributory factors is necessary.

Based on the findings of this study, the authors propose the following recommendations. In order to further develop the evidence-base for LNAs, CPD developers may seek to leverage the support and collaboration of multiple stakeholders including but not limited to:

regulatory bodies who mandate the completion of stipulated annual CPD activities, for necessary resource and access to professional registers;

the academic community who holds the expertise in study design, administration and evaluation;

practice-based colleagues including senior management and line managers who act as gatekeepers of multiple data sources that can be utilized to assess competence, performance, and practice outcomes;

health care professionals who may champion the need for CPD activities that are specifically targeted to improving patient care and health outcomes.

Such involvement and engagement with stakeholders has been reported to be successful in the development of educational interventions for healthcare professionals outside the domain of CPD (Latif et al. Citation2016; Benson et al. Citation2020; Morris et al. Citation2021; Theobald et al. Citation2021).

Conclusion

This study provides CPD educators and program designers an opportunity to gauge current practices and propose strategies for further investigation.

Among other variations reported in the studies, LNA approaches utilized diverse methods, and assessed various domains. Notably, it was unclear why specific approaches were selected over others, and the inconsistent reporting of LNA development, data analysis and subsequent translation, does not reflect the growing body of literature that offers recommendations for LNA design.

Therefore, this review provides the foundations for further research that should include investigation as to how best support CPD developers to adopt the recommended approaches and develop effective LNAs. The accumulation of well-reported research on LNA will pave the road for developing evidence-based approaches for conducting LNA.

Author contributions

M. A. and Z. N. are joint senior authors. L. N., T. H., H. R., A. D., D. A., A. P., and D. S. contributed to data analysis, interpretation and manuscript preparation.

Glossary

Learning Needs Assessment (LNA): A systematic approach to examine what is needed to be learned by either individuals or a group. It involves defining the purpose, design and dissemination, and the use that will be made of the findings for any formal or informal educational activity.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (114.4 KB)Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Muna Said Al-Ismail

Muna Said Al-Ismail, BScPharm, PharmD, is working at Clinical Pharmacy and Practice Department, College of Pharmacy, QU Health, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar.

Lina Mohammad Naseralallah

Lina Mohammad Naseralallah, BScPharm, PharmD, is working at Pharmacy Department, Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar; School of Pharmacy, Institute of Clinical Sciences, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, UK.

Tarteel Ali Hussain

Tarteel Ali Hussain, BScPharm, PharmD, is working at Clinical Pharmacy and Practice Department, College of Pharmacy, QU Health, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar.

Derek Stewart

Derek Stewart, PgCert, BSc, MSc, PhD, is working at Clinical Pharmacy and Practice Department, College of Pharmacy, QU Health, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar.

Dania Alkhiyami

Dania Alkhiyami, BScPharm, PharmD, is working at Pharmacy Department, Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar.

Hadi Mohamad Abu Rasheed

Hadi Mohamad Abu Rasheed, MD, is working at Qatar Cancer Society, Doha, Qatar.

Alaa Daud

Alaa Daud, PgCert, BDS, MSc, is working at College of Dental Medicine, QU Health, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar.

Abdulrouf Pallivalapila

Abdulrouf Pallivalapila, BscPharm, MPharm, MSc, PhD, is working at Pharmacy Department, Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar.

Zachariah Nazar

Zachariah Nazar, PgCert, MRPharmS, PhD, is working at Clinical Pharmacy and Practice Department, College of Pharmacy, QU Health, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar.

References

- Albarqouni L, Hoffmann T, Straus S, Olsen NR, Young T, Ilic D, Shaneyfelt T, Haynes RB, Guyatt G, Glasziou P. 2018. Core competencies in evidence-based practice for health professionals: consensus statement based on a systematic review and Delphi survey. JAMA Netw Open. 1(2):e180281-e180281.

- Allen LM, Palermo C, Armstrong E, Hay M. 2019. Categorising the broad impacts of continuing professional development: a scoping review. Med Educ. 53(11):1087–1099.

- Amery J, Lapwood S. 2004. A study into the educational needs of children’s hospice doctors: a descriptive quantitative and qualitative survey. Palliat Med. 18(8):727–733.

- Association BM 2004. Appraisal: a guide for medical practitioners. London: British Medical Association (BMA).

- Bachman L. 2000. Learner directed assessment. New Jersey: Lawerance Erlbaum Associates.

- Benson H, Lucas C, Williams KA. 2020. Establishing consensus for general practice pharmacist education: a Delphi study. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 12(1):8–13.

- Berger G. 2019. Needs assessment lessons learned in Qatar: a flipped classroom approach. MedEdPublish. 8:48.

- Berger J-L, Karabenick SA. 2016. Construct validity of self-reported metacognitive learning strategies. Educ Assess. 21(1):19–33.

- Berndt A, Murray CM, Kennedy K, Stanley MJ, Gilbert-Hunt S. 2017. Effectiveness of distance learning strategies for continuing professional development (CPD) for rural allied health practitioners: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 17(1):1–13.

- Colthart I, Bagnall G, Evans A, Allbutt H, Haig A, Illing J, McKinstry B. 2008. The effectiveness of self-assessment on the identification of learner needs, learner activity, and impact on clinical practice: BEME Guide no. 10. Med Teach. 30(2):124–145.

- Cook DA, Brydges R, Ginsburg S, Hatala R. 2015. A contemporary approach to validity arguments: a practical guide to Kane’s framework. Med Educ. 49(6):560–575.

- Council GM. 2012. Continuing professional development: guidance for all doctors. Abingdon: GMC.

- Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. 2006. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 296(9):1094–1102.

- De Lusignan S, Wells S, Shaw A, Rowlands G, Crilly T. 2005. A knowledge audit of the managers of primary care organizations: top priority is how to use routinely collected clinical data for quality improvement. Med Inform Internet Med. 30(1):69–80.

- East L, Hammersley V, Hancock B. 2018. Health needs assessment. In: Saks M, Hancock B, Williams M, eds. Developing research in primary care. London: CRC Press; p. 71–105.

- Engelmann JM. 2016. Peer assessment of clinical skills and professional behaviors among undergraduate athletic training students. Athletic Train Educ J. 11(2):95–102.

- Erlingsson C, Brysiewicz P. 2017. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr J Emerg Med. 7(3):93–99.

- Evans R, Elwyn G, Edwards A. 2004. Review of instruments for peer assessment of physicians. BMJ. 328(7450):1240.

- Filipe HP, Mack HG, Golnik KC. 2018. Continuing professional development: progress beyond continuing medical education. Ann Eye Sci. 2(7):46–46.

- Filipe HP, Silva ED, Stulting AA, Golnik KC. 2014. Continuing professional development: Best practices. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 21(2):134–141.

- Gaspard J, Yang C-M. 2016. Training needs assessment of health care professionals in a developing country: the example of Saint Lucia. BMC Med Educ. 16(1):1–6.

- Gazzard J. 2016. Continuing professional development (CPD): a guide to employability and professional development. In: Taylor L, ed. How to develop your healthcare career. New York (NY): Springer; p. 54.

- Grant J. 2002. Learning needs assessment: assessing the need. BMJ. 324(7330):156–159.

- Grant J. 2017. The good CPD guide: a practical guide to managed continuing professional development in medicine. London: CRC Press.

- Grant J, Stanton F. 1999. The effectiveness of continuing professional development: a report for the Chief Medical Officer’s review of continuing professional development in practice. New York (NY): Association for the Study of Medical Education.

- Gupta K. 2011. A practical guide to needs assessment. New York (NY): John Wiley & Sons.

- Hauer J, Quill T. 2011. Educational needs assessment, development of learning objectives, and choosing a teaching approach. J Palliat Med. 14(4):503–508.

- Hicks C, Hennessy D. 1997. Identifying training objectives: the role of negotiation. J Nurs Manag. 5(5):263–265.

- Joly BM, Coronado F, Bickford BC, Leider JP, Alford A, McKeever J, Harper E. 2018. A review of public health training needs assessment approaches: opportunities to move forward. J Public Health Manag Pract. 24(6):571–577.

- Karabenick SA, Woolley ME, Friedel JM, Ammon BV, Blazevski J, Bonney CR, Groot ED, Gilbert MC, Musu L, Kempler TM, et al. 2007. Cognitive processing of self-report items in educational research: do they think what we mean? Educ Psychol. 42(3):139–151.

- Kruger J, Dunning D. 1999. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 77(6):1121–1134.

- Latif A, Pollock K, Anderson C, Waring J, Solomon J, Chen L-C, Anderson E, Gulzar S, Abbasi N, Wharrad H. 2016. Supporting underserved patients with their medicines: a study protocol for a patient/professional coproduced education intervention for community pharmacy staff to improve the provision and delivery of Medicine Use Reviews (MURs). BMJ Open. 6(12):e013500.

- Lockyer J. 1998. Needs assessment: lessons learned. New York (NY): Wiley Online Library.

- Micallef R, Kayyali R. 2019. A systematic review of models used and preferences for continuing education and continuing professional development of pharmacists. Pharmacy. 7(4):154.

- Morris RL, Ruddock A, Gallacher K, Rolfe C, Giles S, Campbell S. 2021. Developing a patient safety guide for primary care: a co‐design approach involving patients, carers and clinicians. Health Expect. 24(1):42–52.

- Norman GR, Shannon SI, Marrin ML. 2004. The need for needs assessment in continuing medical education. BMJ. 328(7446):999–1001.

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. 2016. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 5(1):1–10.

- Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. 2015. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute.

- Phillips JL, Heneka N, Bhattarai P, Fraser C, Shaw T. 2019. Effectiveness of the spaced education pedagogy for clinicians’ continuing professional development: a systematic review. Med Educ. 53(9):886–902.

- Pilcher J. 2016. Learning needs assessment: not only for continuing education. J Nurses Prof Dev. 32(4):185–191.

- Pocock L, Rezaeian M. 2016. Medical education and the practice of medicine in the Muslim countries of the Middle East. ME-JFM. 14(7):28–38.

- Ramani S, McMahon GT, Armstrong EG. 2019. Continuing professional development to foster behaviour change: from principles to practice in health professions education. Med Teach. 41(9):1045–1052.

- Sargeant J, Wong BM, Campbell CM. 2018. CPD of the future: a partnership between quality improvement and competency‐based education. Med Educ. 52(1):125–135.

- Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, the PRISMA-P Group 2015. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 349(1):g7647–g7647.

- Sherman LT, Chappell KB. 2018. Global perspective on continuing professional development. TAPS. 3(2):1–5.

- Tai J, Adachi C. 2017. Peer assessment and professional behaviours: what should we be assessing, how, and why? Med Educ. 51(4):346–347.

- Thampy H. 2013. Identify learning needs. Educ Prim Care. 24(2):138–140.

- Theobald KA, Coyer FM, Henderson AJ, Fox R, Thomson BF, McCarthy AL. 2021. Developing a postgraduate professional education framework for emergency nursing: a co-design approach. BMC Nurs. 20(1):1–10.

- Tobi P. 2016. Health needs assessment. In: Regmi K, Gee I, eds. Public health intelligence. New York (NY): Springer International Publishing; pp. 169–186.

- Van Hoof TJ, Grant RE, Miller NE, Bell M, Campbell C, Colburn L, Davis D, Dorman T, Horsley T, Jacobs-Halsey V, et al. 2015. Society for academic continuing medical education intervention guideline series: guideline 1, performance measurement and feedback. J Contin Educ Health Professions. 35(Suppl 2):S51–S54.

- Vázquez-Calatayud M, Errasti-Ibarrondo B, Choperena A. 2021. Nurses’ continuing professional development: a systematic literature review. Nurse Educ Practice. 50:102963.

- Wallace S, May S. 2016. Assessing and enhancing quality through outcomes‐based continuing professional development (CPD): a review of current practice. Vet Rec. 179(20):515–520.

- Wenghofer EF, Way D, Moxam RS, Wu H, Faulkner D, Klass DJ. 2006. Effectiveness of an enhanced peer assessment program: introducing education into regulatory assessment. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 26(3):199–208.

- Woolley ME, Bowen GL, Bowen NK. 2006. The development and evaluation of procedures to assess child self-report item validity educational and psychological measurement. Educ Psychol Meas. 66(4):687–700.