Abstract

Background

Evidence suggests physicians have higher rates of mental distress than other professionals. Although multiple studies have been conducted among Saudi medical trainees to address this issue, no reviews assessed multiple psychological problems simultaneously. We aimed to examine the prevalence and trends of depression, anxiety, burnout and stress among Saudi medical trainees.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted searching PubMed/Medline, OVID, Scopus, PsychInfo, EBSCOhost and the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) for studies addressing depression, burnout, stress and anxiety among Saudi medical trainees, in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA). Joanna Briggs Critical Appraisal Checklist was used to evaluate quality. The main findings were summarised in tables.

Results

We identified 57 records from 2001 to 2020. Overall (mild, moderate or severe) depression ranged from 28% to 70.6%, while stress ranged from 30.5% to 90.7%. Burnout was primarily assessed among residents with an overall prevalence reaching 85.5%. Overall anxiety ranged from 52.7% to 67%, and was only assessed among undergraduates. Higher levels of all four mental conditions were reported among females.

Conclusion

This review suggests high prevalence of depression, stress, burnout and anxiety among medical trainees, with higher estimates for females compared to males.

Introduction

Physicians’ mental health and psychological well-being have been areas of interest in global literature for several years (Rotenstein et al. Citation2016; Quek et al. Citation2019). There has been recurring evidence of physicians having higher rates of mental distress, suicidal thoughts and burnout in comparison to other professionals (Shanafelt et al. Citation2012; Dyrbye et al. Citation2014; Gerada Citation2018). These issues appear to be particularly prominent during medical school and residency training (Dyrbye et al. Citation2014; Shanafelt et al. Citation2015).

Practice points

remove the line space after practice points and the first bullet point

Higher prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress and burnout is suggested in this region compared to Western populations, yet similar to Asian and Middle Eastern populations.

Consistently higher estimates are reported for women compared to men.

Screening for these health conditions is important for the mental wellbeing of students.

Medical programmes should test and assess interventions that can ameliorate these conditions among medical trainees.

Fostering an educational environment that minimizes mental health problems among these professionals is important, as the status of their well-being is bound to have an impact on their performance. For example, the literature has shown an association between the degree of mental distress and the frequency of medical errors (Fahrenkopf et al. Citation2008; Prins et al. Citation2009; West et al. Citation2012), and other undesirable effects on the healthcare system like reduction in work effort, loss of empathy towards patients and personal harm (West et al. Citation2009; Shanafelt et al. Citation2016).

Worldwide estimates for depression and anxiety among medical trainees range from 27.5% to 35.2% (West et al. Citation2012; Quek et al. Citation2019). The range is even higher in reports from studies conducted on Middle Eastern populations (41.1–42.4%) (Gold et al. Citation2019; Quek et al. Citation2019). For example, 50.8% of medical students in the Middle East report unmet mental health needs in comparison to 32.8% and 34.8% in the USA and China, respectively (Quek et al. Citation2019). Prevalence of burnout among medical trainees in international literature ranged from 7% to 75.2% (Erschens et al. Citation2019; Kaggwa et al. Citation2021; Almutairi et al. Citation2022). As with depression and anxiety, the highest reported prevalence seemed to be in Middle Eastern countries, in which burnout was as high as 75% and 80%, in Lebanon and Egypt, respectively (Kaggwa et al. Citation2021). Thus, the literature suggests possibly higher unmet mental health needs among medical students in the Middle East compared to their counterparts in other areas of the world (West et al. Citation2012; Quek et al. Citation2019).

Although multiple studies addressing depression, anxiety, stress and burnout have been conducted among medical trainees in Saudi Arabia, only one provided a comprehensive review of the Saudi literature (AlJaber Citation2020). This study assessed depression among undergraduate medical students, reporting an overall prevalence ranging from 30.9% to 77.6%, without addressing this condition among residents in training (AlJaber Citation2020). Furthermore, to our knowledge, no other local reviews were conducted to assess these four psychological problems to better understand the scope of these issues among the medical trainee population in Saudi Arabia.

Medical school training in Saudi Arabia is offered at the undergraduate level, and lasts for 6 years, followed by an internship year for practicum training. Specialization in one of the medical disciplines is carried out through postgraduate residency training that may range from 3 to 5 years, depending on the medical specialty. Subspecialisation can be continued after that, through enrolment in a fellowship programme that involves focused training in one of the subspecialties of the medical disciplines. These postgraduate programmes are offered at several training centres, many of which are affiliated with higher education institutions, and are governed and accredited by the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties.

This systematic review aimed to review the prevalence and trends of depression, anxiety, burnout and stress, among medical trainees of all levels; medical students, residents and fellows, in Saudi Arabia. We also summarized the features of these studies in terms of sample size, study setting, tools used for measuring the prevalence, and cut-off points used for identifying these mental health conditions, highlighting the discrepancies in these features across the studies. We believe that shedding light on the health problems at hand can help direct educational institutions, as well as undergraduate and postgraduate programmes in developing interventions that can aid these trainees in the mitigation and coping processes.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We searched PubMed/Medline, OVID, Scopus, PsychInfo, EBSCOhost and the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) for any observational studies addressing the topics of depression, burnout, stress, anxiety or suicidal ideation among Saudi medical students or trainees. The search used Boolean operators, with all possible combinations of the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms provided in Supplementary Appendix 1.

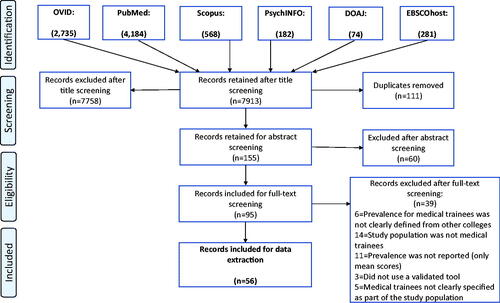

The search strategy followed two stages and was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guidelines (Liberati et al. Citation2009). In the first stage, two investigators (R.D. and L.A.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all articles retrieved from the searched databases separately. Whenever sufficient information was available in the abstract to decide on retaining or excluding the article, the decision was made for articles that would be excluded from the full-text screening stage. Otherwise, articles with titles relevant to the topic of interest, in which abstracts did not provide sufficient information for exclusion, were included in the full-text screening stage.

During the second stage, the ‘full-text screening stage,’ the full texts of all articles retained from the first stage were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria. When in doubt, a third investigator was asked to decide about the inclusion or exclusion of the article. At this stage, duplicate articles retained from different databases were removed using bibliographic managers (Endnote and RefWorks). Studies were identified by searching electronic databases and looking at reference lists for the articles. The search was conducted during the first week of September 2020. A publicly available protocol was submitted for registration prior to conducting the review (PROSPERO, registration number: CRD42021227006, http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We searched for any observational studies that were ever conducted about depression, burnout, anxiety or stress among medical trainees in Saudi Arabia, without year limits or language restrictions. ‘Medical trainees’ were defined as undergraduate, or postgraduate students (residents and fellows) who were studying in the field of medicine.

Inclusion was restricted to articles that met the following criteria: (1) the article was published in a peer-reviewed journal, (2) the sample was clearly defined and included medical trainees, (3) validated tools were used to measure these psychological conditions, (4) the prevalence for either depression (or depressive symptoms), suicidal ideation, burnout, stress or anxiety was clearly reported in the results for medical trainees, and (5) the study design was clearly stated and was either a cross-sectional, cohort or longitudinal design. We excluded any study that did not sample trainees studying in the field of medicine, was conducted outside of Saudi Arabia, or was a review, qualitative or experimental study. The specified study measures of interest were depression, anxiety, stress or burnout, and suicidal ideation as measured by a validated tool. Thus, any study that did not use a validated tool for the measures of interest was excluded. Furthermore, any study that did not report a ‘prevalence’ for any of these measures, or did not report the measure for medical trainees alone was also excluded.

The included study populations were: (1) undergraduate medical students, (2) postgraduate medical students (residents in training or fellows), and (3) both men and women. Included students needed to be trained at one of the Saudi universities or healthcare facilities. The excluded populations were: (1) students from other health-related fields (e.g. dentistry, pharmacy, nursing, allied health sciences), (2) doctors or physicians who were consultants and no longer in training, and (3) other healthcare professionals. Any discrepancies during the study selection phase were resolved by two authors (R.D. and L.A.) through discussion and adjudication.

Data collection process

Every two authors (N.A., M.T.A., S.E.A., S.M.A., M.A.A., and R.A.) extracted the required data points for the same article, independently. To ensure consistency between the authors, a calibration exercise was conducted. Any discrepancies or disagreements were resolved by two other authors (R.D. and L.A.). The extracted data items included the first author’s surname, year of publication, study population (e.g. medical student or resident in training), the study design, the sample size, the response rate, the measure of interest, the tool used for identifying the measure of interest, and the reported prevalence of the measure of interest. If the prevalence was reported by subgroups (e.g. sex, year of training or specialty) this was also included in the table summaries.

Quality evaluation assessment

For this study, we used the Joanna Briggs (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data (Munn et al. Citation2015). This tool was selected because the main estimate of interest in the current study was ‘prevalence.’ It has also been considered to be a good instrument for assessment of validity, when compared to other critical appraisal tools for systematic reviews of epidemiologic studies (Hannes et al. Citation2010). This instrument evaluates the fulfilment of nine study quality items using one of four responses (yes, no, unclear, not applicable). Each ‘yes’ receives one point. For each study, these points are summed to form a composite JBI score out of nine. A previous systematic review has considered a cut-off of 5/9 for each study as an indicator for inclusion (Kaggwa et al. Citation2021). The quality assessment for each study was conducted by paired authors (N.A., M.T.A., S.E.A., S.M.A., M.A.A., and R.A.) independently, after which disagreements were resolved by the other two authors (R.D. and L.A.).

Data synthesis

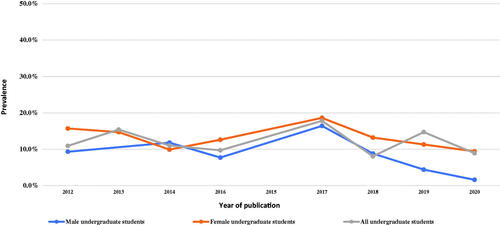

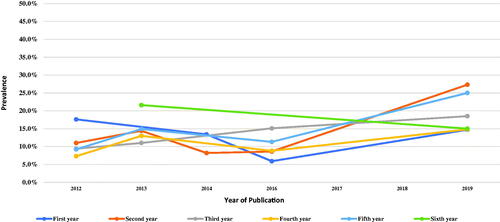

We tabulated the retrieved studies and their main findings. When sufficient data points were available, we plotted the ‘severe level’ measures of interest to show the trend over time, and to show variations in these estimates across sexes and years of training. When more than one estimate was published in the same year, we plotted the average estimate for that year. As this was a systematic review and not a meta-analysis, we did not synthesise pooled estimates. Furthermore, there was great variation in tools used for the same estimate across studies. There was also variability in cut-off points used for defining estimates for the same tools, in addition to the heterogeneity of samples and their sizes.

Results

Study selection

A total of 8024 records were retrieved from the search (). Of these, only 95 were included for full-text screening. During this stage, 39 articles were excluded, resulting in 56 records that were finally included for data extraction.

Characteristics of selected studies

Despite not limiting the search to a specific year range, the 56 articles were only published from 2001 to 2020. Moreover, 64.1% of these studies were conducted between 2017 and 2020. Only one study was a longitudinal assessment of anxiety, depression and stress among undergraduate medical students (pre- and post- final exams) (Kulsoom and Afsar Citation2015), while the rest were cross-sectional studies.

The range of sample sizes for the included studies was 34–318 for residents in training, and 77 to 2562 for undergraduate medical students. Overall, depression and stress were most frequently assessed (39.3% for each). The response rates varied (from 26.3% to 100%), and 11 studies did not report them altogether. Burnout was assessed in 21.4% of the studies, while anxiety was assessed in 14.3%. However, none of the retrieved studies assessed suicidal ideation. The majority of the studies were conducted among participants training in Riyadh (51.8%). Additionally, the target population for most of the studies was undergraduate medical students (66.1%). Out of the studies conducted among residents in training (18), 50% assessed burnout.

Prevalence and trends of depression

A total of 22 of the retrieved studies reported the prevalence of depression for either undergraduate medical students or residents in training. The overall prevalence of depression (mild, moderate or severe) ranged from 28% to 67.4% for undergraduate students, and from 30.2% to 70.6% for residents in training (Supplementary Table 1). However, the study samples were variable, as were the tools used for calculating these estimates. The most frequently used tools were the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (40.9%), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (31.7%).

When inspecting ‘severe depression,’ the studies showed a slightly wider range in estimates for undergraduate students (from 2.2% to as high as 17.8%) compared to residents in training (from 4.7% to 11.8%). When severe depression was plotted against sex, there seemed to be consistently higher frequencies of depression reported among female undergraduate students as compared to males, with the exception of the estimate reported in 2014 (). This gender gap was also observed when comparing severe estimates reported for residents in training (only reported in two studies) (Supplementary Table 1). When observing the trends of severe depression across academic levels, no clear pattern was identified, as some studies reported higher frequencies for earlier years (first, second and third years), while others reported higher frequencies for later years ().

Prevalence and trends of stress

A total of 22 studies were identified for assessing stress (Supplementary Table 2). In these studies, stress and psychological distress seemed to be used interchangeably. As in the case of depression, the reported overall prevalence (mild, moderate or severe stress) varied across studies, ranging from 30.5% to 63.8% for undergraduate students, and ranging from 58.8% to 90.7% for residents in training. The most frequently used tool for assessment of stress was the 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K-10) (36.4%), followed by the Perceived Stress Scale (27.3%). It is important to note that none of the studies had a clear definition for ‘stress,’ although all had used a validated tool for measuring distress or stress in order to calculate the prevalence.

Severe stress among medical students ranged from 12.6% to 35.8%, while it ranged from 49.6% to 59.4% among residents in training. Moreover, the studies reported higher stress levels among females compared to males. Most of the studies suggested that severe stress was experienced at greater frequency during the earlier levels of academic training (first, second and third years) and decreased in later years. On the other hand, two studies suggested that severe stress peaked during the third (Alturkistani et al. Citation2020) and fifth years (Saif et al. Citation2018) of undergraduate training (Supplementary Table 2).

Prevalence and trends of burnout

A total of 12 studies were identified addressing burnout. Of these, only three sampled undergraduate students, while the remainder assessed burnout among residents in training (75%). All but one study used the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) or some variation of it (Supplementary Table 3).

Although most of the studies used this tool, the criteria used for classification of ‘overall burnout’ level varied across studies. For example, some studies defined this estimate among those who had at least one of the following: (1) high levels of emotional exhaustion, (2) high levels of depersonalization or (3) low levels of personal accomplishment (Abdulaziz et al. Citation2009; Aldrees et al. Citation2017; Jamjoom and Park Citation2018). Other studies identified overall burnout among those reporting high levels of all the three constructs simultaneously (Aldrees et al. Citation2013; Altannir et al. Citation2019; Bin Dahmash et al. Citation2019, Citation2020). One study only focused on the levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization for identification of burnout (Hameed et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, discrepancies in this definition were found among the studies for the same author (Aldrees et al. Citation2013, Citation2017). As a result, there was a wide range of reported overall burnout prevalence for residents in training across the studies; from 24.1% to 85.5%. The wide range was also observed for studies that sampled undergraduate medical students (13.4% to 67.1%).

As with the other conditions, overall burnout was higher among females compared to males, with the exception of two studies reporting the contrary (Hameed et al. Citation2018; Bin Dahmash et al. Citation2019). With respect to academic levels, conflicting findings were reported. Two studies suggested greater burnout among earlier years of both undergraduate and postgraduate medical training (Hameed et al. Citation2018; Altannir et al. Citation2019), while another suggested the peak of burnout at the fourth year of undergraduate medical training (Almalki et al. Citation2017; Supplementary Table 3).

Prevalence and trends of anxiety

Only eight of the retrieved studies measured the prevalence of anxiety, all of which sampled medical students (). As with other measures in our current review, the tools of choice varied across the studies, where the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) was used the most. In one study that used the Aga Khan University Anxiety and Depression Scale, the prevalence of anxiety could not be distinguished from that of depression (Inam Citation2007). Among undergraduate medical students, overall anxiety (mild, moderate to severe) ranged from 52.7% to 67%, while moderate to severe ranged from 13.7% to 47%, and severe anxiety ranged from 14.3% to 27.6%. For any study that reported the prevalence by sex, anxiety proportions were higher among females compared to males. Among the four studies reporting anxiety estimates by academic level, two suggested that it peaked in the fourth year (Alshamlan, Alomar, et al. Citation2020; Lateef Junaid et al. Citation2020), one suggested it peaked in the sixth year (Ibrahim N, Al-Kharboush, et al. Citation2013), and one suggested it peaked during the first year of undergraduate training (Inam Citation2007; ).

Table 1. Prevalence of anxiety among medical trainees in Saudi Arabia from the studies conducted from 2000 to 2020.

Quality assessment

All of the assessed studies scored 5/9 or more on the JBI score. Thus, we included all the evaluated studies. However, the sample sizes varied considerably across the studies, which may partly be related to the limited number of individuals available for sampling at the different training centres. This was especially the case for studies that only sampled the few residents who were training at one centre. One concern that should be noted is that many studies conducted census sampling, without a priori sample size calculation or providing evidence of sufficient power for the study. Therefore, it was difficult to evaluate the adequacy of their sample sizes and the response rates. The detailed quality assessment results are supplemented in Supplementary Appendix 2.

Discussion

This systematic review explored and summarized the literature related to addressing depression, stress, anxiety and burnout among Saudi medical trainees, that was published in the past two decades. The main findings from our review can be highlighted in the following points. First, most of the studies addressed these topics among undergraduate medical students, in which depression and stress were the most studied psychological issues, while the literature addressing residents in training mostly assessed burnout. Second, the prevalence of severe depression reported in these studies ranged from 2.2% to 17.8% among undergraduate students, and from 4.7% to 11.8% among residents in training. Third, the prevalence of severe stress ranged from 12.6% to 35.8% for undergraduate students, and from 46.6% to 59.4% for residents in training, suggesting that residents in training may be experiencing greater levels of stress. Fourth, severe anxiety for undergraduate medical students ranged from 14.3% to 27.6%, while none of the retrieved studies addressed anxiety among residents in training. Fifth, the studies suggest a higher overall burnout prevalence among residents in training (24.1–85.5%) compared to undergraduate medical students (13.4–67.1%). Sixth, there was no standard approach for identifying cut-off points for each of the tools used in these studies, which may have resulted in showing a wide range for the same psychological estimate across the studies, even among those using the same instrument. Finally, consistently higher estimates for depression, stress, anxiety and burnout were reported for women compared to men in most of the studies. However, the trends of these conditions in relation to academic training level seemed to be inconsistent.

Our review suggests that there might be a greater focus on the assessment of depression, anxiety, and stress among undergraduate medical students in the Saudi literature, which was reflected by the fewer available studies directed towards residents in training. This comes in agreement with what is observed in similar previous systematic reviews, which also mainly address these conditions among undergraduates (Cuttilan et al. Citation2016; Chunming et al. Citation2017; AlJaber Citation2020; Mirza et al. Citation2021). One of the reasons for this might be related to the feasibility of reaching undergraduate students compared to residents. Unlike medical students, residents usually rotate at different healthcare centres throughout the year, which may make them harder to reach and survey.

The maximum point for the range for mild, moderate or severe depression for undergraduate students identified in our current systematic review (83%) seems to be higher than what has been reported in a previous Saudi systematic review (77.6%) (AlJaber Citation2020). Additionally, the prevalence was greater than 40% in the majority of the retrieved studies addressing depression. This estimate is considered much higher than what is reported for the medical trainee population worldwide (Cuttilan et al. Citation2016), yet comparable to what has been reported in Spain (41%) (Capdevila-Gaudens et al. Citation2021), and Ireland (39%) (Fitzpatrick et al. Citation2019).

Not only does the current study suggest a strikingly high prevalence of depression among undergraduate students, but it also shows high prevalence in depression and burnout among residents in training when compared to international studies. A worldwide systematic review reported the prevalence of depression among residents at 20% (Mata et al. Citation2015), in a study that did not include any Arab populations. Similarly, burnout among residents in training has been estimated at 50% worldwide (Low et al. Citation2019), whereas our study identified a prevalence higher than 70% in five of the retrieved studies. Reported estimates from Saudi studies seem to be the closest to those reported among Chinese residents (Chunming et al. Citation2017; Low et al. Citation2019; Mao et al. Citation2019). This regional variation has been addressed by international studies with the conclusion that higher rates of depression, burnout and anxiety are reported among Asian and Middle Eastern trainee populations compared to others (Ishak et al. Citation2013; Gold et al. Citation2019; Mao et al. Citation2019; Mirza et al. Citation2021; Naji et al. Citation2021). Moreover, when comparing Middle Eastern residents to those from other parts of the world, they seem to report the highest levels of burnout worldwide (Nimer et al. Citation2021).

In our study, we could not observe a clear pattern for change in prevalence of these mental health conditions across academic years. This issue has been debated in the literature with inconclusive evidence. For example, one Irish study reports a steady incrementation of burnout with academic progression, with a steady decrease in depression (Fitzpatrick et al. Citation2019). On the other hand, a Spanish study reports that depression peaks at the fourth, fifth and sixth years of training, while anxiety and burnout peak at the final year (Capdevila-Gaudens et al. Citation2021). To make matters even more confusing, an international meta-analysis suggests that depression peaks during the third year of medical school, when students are first introduced to clinical and bedside training (Mirza et al. Citation2021).

Another observation from our study that is consistent with the international literature, is the higher prevalence of these mental health conditions among women compared to men (AlJaber Citation2020; Jordan et al. Citation2020; Liasi et al. Citation2021; Mirza et al. Citation2021; Thun-Hohenstein et al. Citation2021). Some researchers argue that men may generally have higher resilience than women (Jordan et al. Citation2020). However, this gender discrepancy does not hold among Chinese populations (Cuttilan et al. Citation2016; Chunming et al. Citation2017). In fact, one Chinese study found a higher rate of burnout among male residents compared to females (Chunming et al. Citation2017). Therefore, medical training programmes should develop interventions for mental health support for all genders, to reduce disparities.

One of the strengths of this study is that it provided a comprehensive update about the reported prevalence of important mental health conditions that have been repeatedly studied in the Saudi literature over the past two decades, but have rarely been assessed collectively. Our study reports these estimates in detail, and can serve as a good resource for researchers who would like to follow the trends of these conditions over time. However, this study is not free of limitations. First, although we retrieved a large number of articles from our initial search stages, we did not use an exhaustive list of search engines. Thus, we cannot rule out missing articles not included in these engines or those not captured altogether due to publication bias. Second, our search was restricted to studies published up to September 2020. None of the studies retrieved at any search stage were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, we cannot draw conclusions on how the trends changed during that critical period. Third, the variability in measurement tools and cut-off points used for the same instruments make it difficult to synthesize a single pooled estimate for each of the targeted conditions. The issue with heterogeneity has been especially problematic in systematic reviews and meta-analyses that reported similar variations in their extracted studies (Koutsimani et al. Citation2019; Li et al. Citation2021). We recommend that future researchers who intend to synthesise pooled estimates do so separately by each scale, instead of pooling the rates reported by different scales into one estimate.

Finally, most of the studies did not report the validity and reliability of the used tools. The most frequently used tools for depression, anxiety, burnout and stress were the BDI, DASS-21, MBI and K-10, respectively. However, this seems to be in agreement with the worldwide trends of screening for these health conditions. For example, the literature describes the BDI as ‘a popular tool for screening of depression severity,’ with high content validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability (Dalley et al. Citation2019). The DASS-21 is considered a reliable tool for screening for depression and anxiety and has been tested in 42 languages (Bibi et al. Citation2020). The MBI is considered the most commonly used tool for screening for burnout among medical students (Erschens et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, The K-10 is a widely used tool for screening of stress and showed high validity when tested on Arab populations (Easton et al. Citation2017). Thus, the choice and selection of tools in the retrieved studies seem to be appropriate.

Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive summary about the reported prevalence of important mental health conditions including depression, stress, anxiety and burnout among Saudi medical trainees over the past two decades. The main results demonstrate a strikingly high prevalence of depression among undergraduate students as well as a high prevalence of depression and burnout among residents in training. Furthermore, for all four mental health conditions, the reported prevalence is higher among women (both undergraduate students and residents) compared to men. These results are similar to reports among Asian and Middle Eastern trainee populations. However, they are significantly higher than other international regions. This study has also highlighted the greater focus on the assessment of mental health conditions among undergraduate medical students rather than residents in training.

Decision makers in training programmes and health care authorities worldwide should consider promoting both undergraduate and resident trainee well-being as part of formal medial education training. Educators and medical trainers should be aware of the vulnerability of their students to mental distress and are encouraged to read into the early signs of such conditions in order to help students overcome these problems at an early stage. Training courses in student mental health and wellbeing can be helpful for both undergraduate and postgraduate medical trainers. Further research is still needed on exploring postgraduate medical trainee mental health issues. We also recommend focusing future research on identifying preventable risk factors for these health conditions among the medical trainees, examining the reasons for gender variations, and exploring the best strategies for detecting and managing trainee mental health conditions. Comparative studies across different countries are also encouraged in order to understand the variations in precipitating factors for these conditions, as well as the successful interventions that have been applied for amelioration. Evaluating the impact of such strategies on the future prevalence of these conditions is pertinent to improving the wellbeing and training experience of future physicians.

Authors contributions

L.A. and R.D. contributed equally to this study and are considered both as first authors. Both R.D. and L.A. performed the proposal preparation and registration, data search, review of data extraction, review of bias assessment, and the write up and review of the manuscript. S.M.A. and M.T.A. contributed to data extraction and bias assessment, as well as drafting the manuscript. N.A., M.A.A., R.A. and S.E.A. all contributed equally to preparing the literature review, data extraction and bias assessment. Finally, all authors read, revised and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (66.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download Zip (44.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the King Saud University library for providing access to the scientific databases and their research support.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Data availability statement

All data generated or analysed during this systematic review are included in this published article and its supplementary files.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rufaidah Dabbagh

Rufaidah Dabbagh, MBBS, MPH, DrPH, is an assistant professor and consultant of public health at the Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Lemmese Alwatban

Lemmese Alwatban, MBBS, CCFP, FCFP, MCISc, is an assistant professor and consultant of family medicine at the Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Mohammed Alrubaiaan

Mohammed Alrubaiaan is a medical student at Alfaisal University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Sultan Alharbi

Sultan Alharbi is a medical student at Alfaisal University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Shahad Aldahkil

Shahad Aldakhil is a medical intern student at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Mona AlMuteb

Mona AlMuteb is a medical intern student at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Nora Alsahli

Nora Alsahli is a medical intern student at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Rahaf Almutairi

Rahaf Almutairi is a medical intern student at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

References

- Abdulaziz S, Baharoon S, Al Sayyari A. 2009. Medical residents’ burnout and its impact on quality of care. Clin Teach. 6(4):218–224.

- Abdulghani HM. 2008. Stress and depression among medical students: a cross sectional study at a Medical College in Saudi Aarabia. Pak J Med Sci. 24(1):12–17.

- Abdulghani HM, AlKanhal AA, Mahmoud ES, Ponnamperuma GG, Alfaris EA. 2011. Stress and its effects on medical students: a cross-sectional study at a college of medicine in Saudi Arabia. J Health Popul Nutr. 29(5):516–522.

- Abdulghani HM, Irshad M, Al Zunitan MA, Al Sulihem AA, Al Dehaim MA, Al Esefir WA, Al Rabiah AM, Kameshki RN, Alrowais NA, Sebiany A, et al. 2014. Prevalence of stress in junior doctors during their internship training: a cross-sectional study of three Saudi medical colleges’ hospitals. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 10:1870–1886.

- Abdulghani HM, Al-Harbi MM, Irshad M. 2015. Stress and its association with working efficiency of junior doctors during three postgraduate residency training programs. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 11:3023–3029.

- Agha A, Mordy A, Anwar E, Saleh N, Rashid I, Saeed M. 2015. Burnout among middle-grade doctors of tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Work. 51(4):839–847.

- Al Bedaiwi W, Driver B, Ashton C. 2001. Recognizing stress in postgraduate medical trainees. Ann Saudi Med. 21(1–2):106–109.

- Al-Faris EA, Irfan F, Van der Vleuten CPM, Naeem N, Alsalem A, Alamiri N, Alraiyes T, Alfowzan M, Alabdulsalam A, Ababtain A, et al. 2012. The prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms from an Arabian setting: a wake up call. Med Teach. 34(Suppl 1):S32–S36.

- Al-Khani AM, Sarhandi MI, Zaghloul MS, Ewid M, Saquib N. 2019. A cross-sectional survey on sleep quality, mental health, and academic performance among medical students in Saudi Arabia. BMC Res Notes. 12(1):665.

- Al-Maddah EM, Bk A-D, Khalil MS. 2015. Prevalence of sleep deprivation and relation with depressive symptoms among medical residents in King Fahd University Hospital, Saudi Arabia. Sultan Qaboos Uni Med J. 15(1):78.

- Al-Shagawi MA, Ahmad R, Naqvi AA, Ahmad N. 2018. Determinants of academic stress and stress-related self-medication practice among undergraduate male pharmacy and medical students of a tertiary educational institution in Saudi Arabia. Trop J Pharm Res. 16(12):2997–3003.

- Alaqeel MK, Alowaimer NA, Alonezan AF, Almegbel NY, Alaujan FY. 2017. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome and its association with anxiety among medical students at King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for health sciences in Riyadh. Pak J Med Sci. 33(1):33–36.

- Albajjar MA, Bakarman MA. 2019. Prevalence and correlates of depression among male medical students and interns in Albaha University, Saudi Arabia. J Family Med Prim Care. 8(6):1889–1894.

- Aldrees TM, Aleissa S, Zamakhshary M, Badri M, Sadat-Ali M. 2013. Physician well-being: prevalence of burnout and associated risk factors in a tertiary hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 33(5):451–456.

- Aldrees T, Badri M, Islam T, Alqahtani K. 2015. Burnout among otolaryngology residents in Saudi Arabia: a multicenter study. J Surg Educ. 72(5):844–848.

- Aldrees T, Hassouneh B, Alabdulkarim A, Asad L, Alqaryan S, Aljohani E, Alqahtani K. 2017. Burnout among plastic surgery residents: national survey in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 38(8):832–836.

- AlFaris EA, Naeem N, Irfan F, Qureshi R, van der Vleuten C. 2014. Student centered curricular elements are associated with a healthier educational environment and lower depressive symptoms in medical students. BMC Med Educ. 14:192.

- AlFaris E, Irfan F, Qureshi R, Naeem N, Alshomrani A, Ponnamperuma G, Al Yousufi N, Al Maflehi N, Al Naami M, Jamal A, et al. 2016. Health professions’ students have an alarming prevalence of depressive symptoms: exploration of the associated factors. BMC Med Educ. 16(1):279–278.

- AlFaris E, Irfan F, AlSayyari S, AlDahlawi W, Almuhaideb S, Almehaidib A, Almoqati S, Ahmed AMA, Ponnamperuma G, AlMughthim M, et al. 2018. Validation of a new study skills scale to provide an explanation for depressive symptoms among medical students. PLoS One. 13(6):e0199037.

- AlFaris E, AlMughthim M, Irfan F, Al Maflehi N, Ponnamperuma G, AlFaris HE, Ahmed AMA, van der Vleuten C. 2019. The relationship between study skills and depressive symptoms among medical residents. BMC Med Educ. 19(1):435.

- Alfayez DI, AlShehri NA. 2020. Perceived stigma towards psychological illness in relation to psychological distress among medical students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Acad Psychiatry. 44(5):538–544.

- Alharbi H, Almalki A, Alabdan F, Haddad B. 2018. Depression among medical students in Saudi medical colleges: a cross-sectional study. Adv Med Educ Pract. 9:887–891.

- AlJaber MI. 2020. The prevalence and associated factors of depression among medical students of Saudi Arabia: a systematic review. J Family Med Prim Care. 9(6):2608–2614.

- Almailabi MM, Alajmi RS, Balkhy AL, Khalifa MJ, Mikwar ZA, Khan MA. 2019. Quality of life among surgical residents at King Abdulaziz Medical City in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 7(23):4163–4167.

- Almalki SA, Almojali AI, Alothman AS, Masuadi EM, Alaqeel MK. 2017. Burnout and its association with extracurricular activities among medical students in Saudi Arabia. Int J Med Educ. 8:144–150.

- Almojali AI, Almalki SA, Alothman AS, Masuadi EM, Alaqeel MK. 2017. The prevalence and association of stress with sleep quality among medical students. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 7(3):169–174.

- Almutairi H, Alsubaiei A, Abduljawad S, Alshatti A, Fekih-Romdhane F, Husni M, Jahrami H. 2022. Prevalence of burnout in medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 68(6):1157–1170.

- Alotaibi AD, Alosaimi FM, Alajlan AA, Bin Abdulrahman KA. 2020. The relationship between sleep quality, stress, and academic performance among medical students. J Family Community Med. 27(1):23–28.

- Alothman OM, Alotaibi YM, Alayed SI, Aldakhil SK, Alshehri MA. 2020. Prevalence of depression among resident doctors in King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Pharm Res Allied Sci. 9(3):81–86.

- Alqahtani N, Abdulaziz A, Hendi O, Mahfouz MM. 2020. Prevalence of burnout syndrome among students of health care colleges and its correlation to musculoskeletal disorders in Saudi Arabia. Int J Prev Med. 11:38.

- Alsabaani A, Alshahrani AA, Abukaftah AS, Abdullah SF. 2018. Association between over-use of social media and depression among medical students, King Khalid University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine. 70(8):1305–1311.

- Alsalameh NS, Alkhalifah AK, Alkhaldi NK, Alkulaib AA. 2017. Depression among medical students in Saudi Arabia. EJHM. 68(1):974–981.

- Alsalhi AH, Almigbal TH, Alsalhi HH, Batais MA. 2018. The relationship between stress and academic achievement of medical students in King Saud University: a cross-sectional study. Kuwait Med J. 50(1):60–65.

- Alshamlan NA, Alomar RS, Shammari MAA, Alshamlan RA, Alshamlan AA, Sebiany AM. 2020. Anxiety and its association with preparation for future specialty: a cross-sectional study among medical students, Saudi Arabia. J Multidiscip Healthc. 13:581–591.

- AlShamlan NA, AlShamlan RA, AlShamlan AA, AlOmar RS, AlAmer NA, Darwish MA, Sebiany AM. 2020. Prevalence of depression and its associated factors among clinical-year medical students in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. Postgrad Med J. 96(1136):343–348.

- Alshardi A, Farahat F. 2020. Prevalence and predictors of depression among medical residents in Western Saudi Arabia. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 27(4):746–752.

- Altannir Y, Alnajjar W, Ahmad SO, Altannir M, Yousuf F, Obeidat A, Al-Tannir M. 2019. Assessment of burnout in medical undergraduate students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. BMC Med Educ. 19(1):34.

- Alturkistani LH, Hendi OM, Bajaber AS, Alhamoud MA, Althobaiti SS, Alharthi TA, Atallah AA. 2020. Prevalence of lower back pain and its relation to stress among medical students in Taif University, Saudi Arabia. Int J Prev Med. 11:35.

- Alzahrani AM, Hakami A, AlHadi A, Batais MA, Alrasheed AA, Almigbal TH. 2020. The interplay between mindfulness, depression, stress and academic performance in medical students: a Saudi perspective. PLoS One. 15(4):e0231088.

- Andejani DF, Al-Issa SI, Al-Qattan MM. 2017. Depressive symptoms among plastic surgery residents. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 5(10):e1516.

- Bahnassy AA, Saeed AA, Almatham KI, Moazen MA, Al Abdulkarim YA. 2018. Stress among residents in a tertiary care center, Riyadh, Saudi. Arabia: Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors. Presna Med Argent. 104(6):1000317.

- Bibi A, Lin M, Zhang XC, Margraf J. 2020. Psychometric properties and measurement invariance of Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21) across cultures. Int J Psychol. 55(6):916–925.

- Bin Dahmash A, Alhadlaq AS, Alhujayri AK, Alkholaiwi F, Alosaimi NA. 2019. Emotional intelligence and burnout in plastic surgery residents: is there a relationship? Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 7(5):e2057.

- Bin Dahmash A, Alorfi FK, Alharbi A, Aldayel A, Kamel AM, Almoaiqel M. 2020. Burnout phenomenon and its predictors in radiology residents. Acad Radiol. 27(7):1033–1039.

- Capdevila-Gaudens P, García-Abajo JM, Flores-Funes D, García-Barbero M, García-Estañ J. 2021. Depression, anxiety, burnout and empathy among Spanish medical students. PLoS One. 16(12):e0260359.

- Chunming WM, Harrison R, MacIntyre R, Travaglia J, Balasooriya C. 2017. Burnout in medical students: a systematic review of experiences in Chinese medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 17(1):217.

- Cuttilan AN, Sayampanathan AA, Ho RC. 2016. Mental health issues amongst medical students in Asia: a systematic review [2000-2015]. Ann Transl Med. 4(4):72.

- Dagistani A, Al Hejaili F, Binsalih S, Al Jahdali H, Al Sayyari A. 2016. Stress in medical students in a problem-based learning curriculum. Int J High Educ. 5(3):12–19.

- Dalley BJ, Ciriako JK, Zimmerman K, Stubbs K, Warne RT. 2019. Reviewing the Beck Depression Inventory on its psychometric properties. J Utah Acad Sci Art Letters. 96:285–308.

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Boone S, Tan L, Sloan J, Shanafelt TD. 2014. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 89(3):443–451.

- Easton SD, Safadi NS, Wang Y, Hasson IR. 2017. The Kessler psychological distress scale: translation and validation of an Arabic version. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 15(1):215.

- El-Gilany AH, Amr M, Hammad S. 2008. Perceived stress among male medical students in Egypt and Saudi Arabia: effect of sociodemographic factors. Ann Saudi Med. 28(6):442–448.

- Erschens R, Keifenheim KE, Herrmann-Werner A, Loda T, Schwille-Kiuntke J, Bugaj TJ, Nikendei C, Huhn D, Zipfel S, Junne F. 2019. Professional burnout among medical students: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Med Teach. 41(2):172–183.

- Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, Sharek PJ, Lewin D, Chiang VW, Edwards S, Wiedermann BL, Landrigan CP. 2008. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 336(7642):488–491.

- Fitzpatrick O, Biesma R, Conroy RM, McGarvey A. 2019. Prevalence and relationship between burnout and depression in our future doctors: a cross-sectional study in a cohort of preclinical and clinical medical students in Ireland. BMJ Open. 9(4):e023297.

- Gazzaz ZJ, Baig M, Al Alhendi BSM, Al Suliman MMO, Al Alhendi AS, Al-Grad MSH, Qurayshah MAA. 2018. Perceived stress, reasons for and sources of stress among medical students at Rabigh Medical College, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. BMC Med Educ. 18(1):29.

- Gerada C. 2018. Doctors, suicide and mental illness. BJPsych Bull. 42(4):165–168.

- Gold JA, Hu X, Huang G, Li W-Z, Wu Y-F, Gao S, Liu Z-N, Trockel M, Li W-Z, Wu Y-F, et al. 2019. Medical student depression and its correlates across three international medical schools. World J Psychiatry. 9(4):65–77.

- Hamasha AA, Kareem YM, Alghamdi MS, Algarni MS, Alahedib KS, Alharbi FA. 2019. Risk indicators of depression among medical, dental, nursing, pharmacology, and other medical science students in Saudi Arabia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 31(7-8):646–652.

- Hameed TK, Masuadi E, Al Asmary NA, Al-Anzi FG, Al Dubayee MS. 2018. A study of resident duty hours and burnout in a sample of Saudi residents. BMC Med Educ. 18(1):180.

- Hannes K, Lockwood C, Pearson A. 2010. A comparative analysis of three online appraisal instruments’ ability to assess validity in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 20(12):1736–1743.

- Ibrahim N, Al-Kharboush D, El-Khatib L, Al Habib A, Asali D. 2013. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression among female medical students in King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Iranian J Public Health. 42(7):726–736.

- Ibrahim NK, Battarjee WF, Almehmadi SA. 2013. Prevalence and predictors of irritable bowel syndrome among medical students and interns in King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah. Libyan J Med. 8(1):21287.

- Inam SB. 2007. Anxiety and depression among students of a Medical College in Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Sci. 1(2):295–300.

- Ishak W, Nikravesh R, Lederer S, Perry R, Ogunyemi D, Bernstein C. 2013. Burnout in medical students: a systematic review. Clin Teach. 10(4):242–245.

- Jamjoom RS, Park YS. 2018. Assessment of pediatric residents burnout in a tertiary academic centre. Saudi Med J. 39(3):296–300.

- Jordan RK, Shah SS, Desai H, Tripi J, Mitchell A, Worth RG. 2020. Variation of stress levels, burnout, and resilience throughout the academic year in first-year medical students. PLoS One. 15(10):e0240667.

- Kaggwa MM, Kajjimu J, Sserunkuma J, Najjuka SM, Atim LM, Olum R, Tagg A, Bongomin F. 2021. Prevalence of burnout among university students in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 16(8):e0256402.

- Koutsimani P, Montgomery A, Georganta K. 2019. The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 10:284.

- Kulsoom B, Afsar NA. 2015. Stress, anxiety, and depression among medical students in a multiethnic setting. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 11:1713–1722.

- Lateef Junaid MA, Auf AI, Shaikh K, Khan N, Abdelrahim SA. 2020. Correlation between academic performance and anxiety in medical students of Majmaah University - KSA. J Pak Med Assoc. 70(5):865–868.

- Li Y, Cao L, Mo C, Tan D, Mai T, Zhang Z. 2021. Prevalence of burnout in medical students in China: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Medicine (Baltimore). 100(26):e26329.

- Liasi GA, Nejad SM, Sami N, Khakpour S, Yekta BG. 2021. The prevalence of educational burnout, depression, anxiety, and stress among medical students of the Islamic Azad University in Tehran, Iran. BMC Med Educ. 21(1):471.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. 2009. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 339:b2700.

- Low ZX, Yeo KA, Sharma VK, Leung GK, McIntyre RS, Guerrero A, Lu B, Sin Fai Lam CC, Tran BX, Nguyen LH, et al. 2019. Prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: a meta-analysis. IJERPH. 16(9):1479.

- Mao Y, Zhang N, Liu J, Zhu B, He R, Wang X. 2019. A systematic review of depression and anxiety in medical students in China. BMC Med Educ. 19(1):327.

- Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, Khan R, Guille C, Di Angelantonio E, Sen S. 2015. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 314(22):2373–2383.

- Mirza AA, Baig M, Beyari GM, Halawani MA, Mirza AA. 2021. Depression and anxiety among medical students: a brief overview. Adv Med Educ Pract. 12:393–398.

- Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. 2015. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 13(3):147–153.

- Naji L, Singh B, Shah A, Naji F, Dennis B, Kavanagh O, Banfield L, Alyass A, Razak F, Samaan Z, et al. 2021. Global prevalence of burnout among postgraduate medical trainees: a systematic review and meta-regression. CMAJ Open. 9(1):E189–e200.

- Nimer A, Naser S, Sultan N, Alasad RS, Rabadi A, Abu-Jubba M, Sabbagh Al, Jaradat MQ, AlKayed KM, Aborajooh Z, et al. 2021. Burnout syndrome during residency training in Jordan: prevalence, risk factors, and implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(4):1557.

- Prins JT, van der Heijden FM, Hoekstra-Weebers JE, Bakker AB, van de Wiel HB, Jacobs B, Gazendam-Donofrio SM. 2009. Burnout, engagement and resident physicians’ self-reported errors. Psychol Health Med. 14(6):654–666.

- Quek TT, Tam WW, Tran BX, Zhang M, Zhang Z, Ho CS, Ho RC. 2019. The global prevalence of anxiety among medical students: a meta-analysis. IJERPH. 16(15):2735.

- Rafique N, Al-Asoom LI, Latif R, Al Sunni A, Wasi S. 2019. Comparing levels of psychological stress and its inducing factors among medical students. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 14(6):488–494.

- Rasheed FA, Naqvi AA, Ahmad R, Ahmad N. 2017. Academic stress and prevalence of stress-related self-medication among undergraduate female students of health and non-health cluster colleges of a public sector University in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 9(4):251–258.

- Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, Sen S, Mata DA. 2016. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 316(21):2214–2236.

- Saif GAB, Alotaibi HM, Alzolibani AA, Almodihesh NA, Albraidi HF, Alotaibi NM, Yosipovitch G. 2018. Association of psychological stress with skin symptoms among medical students. Saudi Med J. 39(1):59–66.

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, West CP, Sloan J, Oreskovich MR. 2012. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 172(18):1377–1385.

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Satele D, Sloan J, West CP. 2015. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 90(12):1600–1613.

- Shanafelt TD, Mungo M, Schmitgen J, Storz KA, Reeves D, Hayes SN, Sloan JA, Swensen SJ, Buskirk SJ. 2016. Longitudinal study evaluating the association between physician burnout and changes in professional work effort. Mayo Clin Proc. 91(4):422–431.

- Sultan SA, Alhosaini AA, Sheerah SA , Alrohaily AA, Saeed HM, Al-Raddadi NM, Halawani MS, Shaheen MA, Turkistani AY, Taha H, et al. 2016. Prevalence of depression among medical students at Taibah University, Madinah, Saudi Arabia. In J Acad Sci Res. 4(1):93–102.

- Thun-Hohenstein L, Höbinger-Ablasser C, Geyerhofer S, Lampert K, Schreuer M, Fritz C. 2021. Burnout in medical students. Neuropsychiatr. 35(1):17–27.

- West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. 2009. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA. 302(12):1294–1300.

- West CP, Tan AD, Shanafelt TD. 2012. Association of resident fatigue and distress with occupational blood and body fluid exposures and motor vehicle incidents. Mayo Clin Proc. 87(12):1138–1144.