Abstract

There is increasing interest in how student engagement can be enhanced in medical schools: not just engagement with learning but with broader academic practices such as curriculum development, research, organisational leadership, and community involvement. To foster evidence-based practice, it is important to understand how institutions from diverse sociocultural contexts achieve excellence in student engagement.

We analysed 11 successful applications for an international award in student engagement and interviewed nine key informants from five medical schools across four continents, characterising how and why student engagement was fostered at these institutions.

Document analysis revealed considerable consensus on the core practices of student engagement, as well as innovative and creative practices often in response to local strengths and challenges. The interviews uncovered the importance of an authentic partnership culture between students and faculty which sustained mutually beneficial enhancements across multiple domains. Faculty promoted, welcomed, and acted on student inputs, and students reported greater willingness to participate if they could see the benefits. These combined to create self-perpetuating virtuous cycles of academic endeavour. Successful strategies included having participatory values actively reinforced by senior leadership, engagement activities that are driven by both students and staff, and focusing on strategies with reciprocal benefits for all stakeholders.

Introduction

Student engagement is conceptualised and defined in multiple ways (Appleton et al. Citation2008), and there are a variety of understandings about what it is, and how it can be achieved across cultural and institutional contexts (Tanaka Citation2019). Kahu presents a framework for understanding engagement through the lens of academic success: engagement with learning (Kahu Citation2013). Others conceptualise it through a participatory lens: students as partners with faculty across all domains of academic work including research, teaching, governance and within their local community (Peters et al. Citation2019). The latter aligns with the concept that student engagement develops from a reciprocal investment between students and institutions, with mutual benefits (Trowler Citation2010). Students become engaged through non-linear processes and are influenced by the meanings they make of their experiences and interactions (Bryson Citation2014). The involvement of students in their learning experiences, and the critical relevance of institutional culture, are anchoring elements to an overarching conception of student engagement.

Practice points

Student engagement can enhance medical education, improve institutional governance, support research activities, and enable community connections.

Engagement succeeds through authentic participatory values, broad bilateral commitment, and reciprocal benefits; else it can become a bureaucratic exercise.

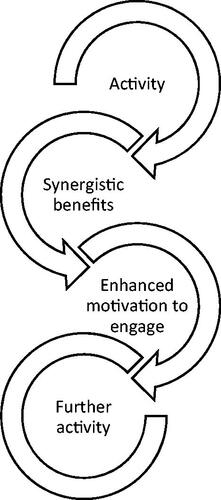

When done successfully, it drives self-sustaining virtuous cycles of activity and a supportive institutional culture.

There are commonalities and differentiating practices across international award-winning institutions.

There is growing interest in engagement as an indicator of quality for medical schools (Milles et al. Citation2019; Peters et al. Citation2019). The Association for Medical Education in Europe (AMEE) has established the ASPIRE-to-Excellence Awards to recognise institutional excellence in medical education across several categories (Hunt et al. Citation2018). There were 16 ASPIRE awards for excellence in student engagement between 2013 and 2018. The criteria require medical schools to evidence student engagement in policy and decision-making activities; in the provision and evaluation of the school’s education programme; in its academic community; and in the local community through extra-curricular activities and service delivery (Aspire Academy Citation2022).

Although the award criteria are defined, the processes that medical schools adopt to achieve excellence are not prescribed. Award-winning medical schools have therefore developed locally congruent ways of optimising student engagement within their own institutions and contexts. To create an evidence-base, it is important to understand what different institutions have done to achieve excellence, how and why they were able to create participatory institutional cultures within their local contexts, and whether they were able to attain the mutual benefits for students and institutions described by Trowler (Trowler Citation2010). ASPIRE award winners might offer important clues about potentially successful activities and drivers. The objective of this study was therefore to characterise student engagement through an analysis of what happened and why at these award-winning medical schools, so that others can identify effective strategies that could be adapted to their own institutional environments.

Methods

Aim

Our aim was to explore how and why excellence in student engagement is conceptualised and achieved internationally in undergraduate medical education.

Design

We adopted a multiple case study design (Greene and David Citation1984) with the ‘unit of study’ being a medical school that had been awarded Excellence in Student Engagement by the ASPIRE Academy. We used a combination of key stakeholder interviews and document analysis of successful ASPIRE award applications to explore both generalisable and contextual factors.

Researcher characteristics and reflexivity

The research team comprised a medical student (FF), a senior education research fellow (KLG) and two professors of medical education (MJC and SFS). Three authors had been involved in two successful ASPIRE awards; to avoid any potential conflicts, these schools were excluded from the study. Our positionality is that student engagement is an important aspiration for medical schools which influenced our approach to inquiry.

Context

This is an international study, involving medical schools from North America, Asia, Central and Western Europe, and Australia.

Ethics

Approvals were obtained from the ethics review committee of the University of Minho Ethics Commission (Application number: CEICSH 030/2019). Submission of documentation was deemed consent for analysis. We obtained informed written consent from interview participants. Identifying data relating to people or institutions were redacted.

Participants and sampling

Sixteen schools were awarded ASPIRE-to-Excellence awards for student engagement between 2013 and 2018. Two were excluded as related to the research team, three declined to participate and the remaining 11 applications (10 medical schools and one veterinary school) were analysed for engagement activities (see below).

Five case-study schools were purposefully sampled for interviews based on the following criteria:

Medicine as principal subject of study

Diversity of institutional and cultural contexts

Application rich in detailed examples of engagement activities

Staff involved in the ASPIRE application available for interview.

We asked to interview a faculty member responsible for the application and one actively engaged medical student at each institution.

Interview strategy

The interviews were designed to explore factors not included in the award applications. The interview schedule was informed by the literature and piloted and refined by KLG and SFS. Interviews were conducted online by FF. We explored interviewees’ personal perspectives on the meaning of student engagement; how engagement is conceptualised within their institution; their personal and institutional motivations for becoming involved in student engagement and applying for the award; and their perceptions of the drivers, optimal processes, challenges, and outcomes of excellence in student engagement across the four main areas of the ASPIRE award (governance, curriculum, academic practices, societal engagement).

Interview data processing

Recordings were professionally transcribed by a native English speaker and checked back against the original recordings. Qualitative coding was facilitated by NVivo 12 software.

Document analysis

The engagement strategies detailed in the ASPIRE applications were listed independently by SFS and FF and discrepancies resolved through discussion. The strategies adopted by each school were classified as ‘core’ if they were common to at least 8 schools, and ‘differentiating’ if they were specific to fewer schools. Differentiating strategies were selected for inclusion in the results table based on how interesting or innovative they were through a process of consensual discussion.

Interview analysis

Interviews were coded line-by-line by FF, supported by KLG. Codes were grouped together collaboratively into an axial coding structure of drivers, activities and outcomes (Allen 2017). The drivers and outcomes were subcategorised into student factors, faculty factors, organisational factors, and societal factors. Activities were subcategorised according to the four areas of the ASPIRE award (governance, curriculum, academic practice and societal engagement). Similar content codes were inductively grouped into themes within each axial code by FF who also identified associations, synergies, and positive and negative feedback loops between themes. Categories, themes and associations were audited by KLG.

Results

The document analysis included 11 successful ASPIRE applications from six European, two Asian, two North American and one Australian school. We interviewed five key faculty and four students from five institutions. Interviews lasted between 24 and 63 min, median 48 min. summarises interviewee characteristics.

Table 1. Interview participants.

Document analysis () revealed a high degree of congruence in the strategies used by schools to achieve the ASPIRE criteria, despite diverse sociocultural contexts. Student engagement with faculty development and in the development of educational resources were the only areas with no common approaches. There were also divergent strategies, some of which were clearly context-dependent, for example, in response to requirements from the national regulator. Interview themes are presented in . Associations, synergies, and feedback loops are presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 2. Document analysis of successful ASPIRE applications for excellence in student engagement.

Table 3. Thematic analysis.

Interpretation

Our interpretation explores the interrelationship between factors and themes; therefore, we present an integrated interpretation rather than a theme-by-theme approach. Quotes are given without linguistic correction, clarifications are indicated by square brackets, and omissions by ellipses.

How did participants conceptualise student engagement?

As expected, interviewees confirmed the conceptions of student engagement across all four ASPIRE categories but mostly discussed ‘engagement with the curriculum’ as their core activity, focusing on partnership approaches to designing, delivering and quality assuring students’ educational experiences.

Student engagement as a values-driven practice

Faculty described being driven by democratic, collaborative, and ethical values, which underpinned their efforts to promote student engagement and mitigate barriers. If values weren’t the primary underpinning reason, engagement risked becoming inauthentic:

So, I do think the senior staff really need to buy into it and believe in it, otherwise they’ll just do it tokenistically… I think the more inexperienced staff are, the more resistant they are to it and nervous of it. And so, you need really strong leadership and support for people, to encourage them to take that leap of faith. (Faculty, European school 3)

They are really intrinsically motivated doing this. And there is always a good atmosphere between the students. Really constructive. Really open-minded. Really great. (Faculty, European school 1)

One school described student engagement as an intrinsic institutional quality that was built into the school’s mission which facilitated student-faculty partnership approaches.

Well, I think right from the very beginning, the mission of our medical school is to help the people [in the community] to achieve the best health they can get through education. (Faculty, North American school)

Many of the differentiating practices listed in go beyond tokenistic engagement and further evidence the authentic commitment of participating institutions to their students, as well as students to their institutions. Some differentiating practices addressed local challenges, but many were aspirational. Examples included enablement, empowerment, and inclusion strategies such as leadership and mentorship courses, educational development opportunities, student-led quality improvement, as well as protected time and financial support for engagement activities.

Organisational culture as a collective endeavour

Interviewees described the essential need to build a broad acceptance of a culture of student agency, so that students’ views were acted on and students were accepted as equal partners in the activities of the school. Faculty described the importance of creating opportunities to engage, whilst also encouraging student-led initiatives. Students tended to focus on the importance of making engagement opportunities visible to all students and demonstrating that student suggestions and feedback would be acted on. Both faculty and students described the importance of giving students an active role in creating and managing their own learning environment.

I think they’re [faculty] the most important people in getting us engaged only because they’re the ones that give us the opportunities… (Student, North American school)

Faculty described how a sustainable culture of engagement required broad commitment and was most successful when driven from multiple directions, describing the influence of teaching faculty, leadership, administration and students as promoters, models, and advisors in the development of student engagement.

It’s not just about professors, and it’s not just about students. It’s about how those two can live or work together. (Faculty, European school 2)

From the bottom up, they [the students] are always asking for it, and they’re empowered to try and do it. And then, top down, the very senior staff I think need to believe in it. And then, the two hopefully will meet in the middle… It does need to be everyone that buys into it (Faculty, European school 3)

One school cited a scaffolding strategy to support students in leadership and negotiation skills, to mitigate the power imbalance implicit between student and teacher.

(…) we meet with them and start to teach about leadership skills, so how to give feedback (…). They get a lot of one-on-one time with leaders in the institution as they help them grow as leaders. (Faculty, North American school)

Sustainable student engagement is supported by reciprocal benefits

Despite describing student engagement primarily as an intrinsic organisational value, interviewees also described multiple co-benefits to institutions, students, and faculty. Students described learning transferrable skills relating to leadership and collaborative practices, which improved their curriculum vitae, as well as increased satisfaction and cohort morale.

When I tell [friends] about what my school has, they are amazed… and they want that to happen in their university as well. I think it’s the fact that the teachers listen to us and if we say something, they value our concerns. (Student, Asian school)

Faculty described how student engagement created tangible curricular improvements and shifted the identity of students from consumers to co-participants in educational endeavour. One student described how the ASPIRE award had influenced their decision to become a student representative, and a faculty member described how preparing the ASPIRE application had prompted greater acceptance of partnership approaches at an organisational level.

…the ASPIRE Award can make the process of the student engagement more acceptable and [create] more understanding among the faculty. (Faculty, Asian school).

Participants described how the positive impacts of student engagement needed be felt by both students and faculty to maintain this collaborative culture. Negative impacts, such as additional time commitment or work, were mitigated by these reciprocal benefits. Students described feeling more inclined to engage if they felt supported and listened to. They described the positive influence of faculty that pro-actively elicited and acted on their feedback.

… because it’s beneficial to the faculty to have students to get out there and to work and it’s beneficial to the students to be able to give these kinds of experiences while in medical school. (Student, North American school)

I think the reason why [students might not engage] is if they don’t really believe their views are going to be taken into account. (Faculty, European school 3)

Faculty described how they valued the support, feedback, and guidance of students, effectively placing them as partners in educational innovation and quality improvement.

Student engagement means that students… have a loud voice, and the other faculty members, like the professors, really appreciate what they are saying. (Faculty, European school 2)

The benefit is that you end up having a curriculum that is really fit for purpose. (Faculty, European school 3)

I think our students are really proud of the curriculum. (Faculty, European school 1)

Both students and faculty described several synergies whereby activities enhanced outcomes, which increased their motivation to engage further (). These virtuous circles of student engagement led to sustained enhancements across multiple areas. Conversely, where these synergies were not in place, student engagement was seen as less sustainable. Participants described several activities with synergistic benefits including: acting on student feedback, valuing and show-casing student-led initiatives, role-modelling collaborative values, supporting authentic student representation in governance, and creating engagement activities that are genuinely enriching.

Figure 1. The virtuous cycle of student engagement. Student participation and engagement is sustained through practices that create synergistic benefits for all stakeholders.

I don’t feel well in an environment that does not support me… and when it all happened, I got so motivated… and together I would say that teachers and students became one structure. And we use this structure to change, to make a movement that promotes a more positive way of student-teacher understanding. (Student, Asian school)

And there is a problem that student engagement becomes just another form of a rigid structure which doesn’t really bring change, but it just is there for the sake of being there…. It can’t be just a bureaucratic form of cohabitating… [students] have to have the idea that they are listened to and there is some change done. (Faculty, European school 2)

Challenges

When asked about equitable participation in engagement, including whether any sub-groups within their student population were more engaged than others, participants described direct and indirect challenges that were not universal but mirrored their sociocultural and institutional contexts. Engagement with non-core activities was partly attributed to personal characteristics such as extroversion, aptitude, and confidence, but mostly to whether the student had the capacity and opportunity to take on extra work. Students were wary of ‘tick box’ engagement activities or of faculty using keen students as free labour. Faculty were wary of being expected to act on student-led initiatives that were not based on a mature understanding of the issues. These highlight the need for bilateral reciprocal benefits as well as enablement strategies. Local challenges and modulating factors are listed in .

Table 4. School characteristics and modulating factors to student engagement.

Discussion

We have identified a range of institutional conditions that lead to student engagement at ASPIRE award-winning medical schools, highlighting core evidence-based practices as well as exceptional or innovative practices. Core drivers include a collaborative organisational culture that values students as equals and creates authentic and visible student engagement opportunities. We have found that student engagement is perpetuated at these schools through virtuous circles where participatory practices result in synergistic benefits for students, faculty, and institutions. We identified contextual modulating factors that impact on engagement on personal- and cohort-levels. These were dominated by the capacity of students to take on extra-curricular opportunities, but also reflected the contexts in which the school was situated. Importantly, the values that these schools described helped many to work innovatively to mitigate barriers to engagement.

Our findings support previous research that emphasises how the organisation, faculty, and students all need to be committed (Coates Citation2005; Umbach and Wawrzynski Citation2005; Trowler Citation2010; Hu et al. Citation2012). Our findings, however, contrast to research that emphasises the role of targets and incentivisation structures (Umbach and Wawrzynski Citation2005; Trowler Citation2010): we have found that organisational values and intrinsic motivations are also key drivers of participatory activities. Our findings corroborate the need for institutions to make engagement strategies visible and accessible for students, thereby re-enforcing these values (Coates Citation2005; Fredricks et al. Citation2016; Zdravković et al. Citation2018). Whilst the support of academic staff has been described as one of the more recognizable drivers of student engagement (Umbach and Wawrzynski Citation2005; Hu et al. Citation2012), our study suggests that engagement becomes more successful when championed by both students and staff. In two of our case studies, students had driven local or national curricular change themselves. This confirms Zdravković and colleagues’ observations that, when given agency, students have the capacity to enhance their own learning environment (Zdravković et al. Citation2018). Our findings are consistent with other research that highlights that students who are valued as partners by staff develop self-confidence, motivation to contribute to their school, and commitment to institutional and individual success (Umbach and Wawrzynski Citation2005; Hu et al. Citation2012; Lyness et al. Citation2013; Bryson Citation2014). Whilst several studies suggest that students have unique characteristics and interests that influence the way they engage individually and collectively (Trowler Citation2010; Bryson Citation2014), our research indicates that it is how these student characteristics intersect with broader institutional and sociocultural contexts that matters. This implies that active inclusion strategies might be helpful.

Although the ASPIRE application asked for evidence across four prescribed domains, our document analysis of applications highlighted the relative importance of engagement in governance and curriculum. This weighting was confirmed in our interviews where participants tended to focus on curricular engagement, and governance principally where it facilitated student engagement in the curriculum. Bryson found student engagement in this area had important benefits for both the curriculum and the learning process (Bryson Citation2014), reinforcing our theory of reciprocal benefits. There are unresolved tensions between ensuring the ASPIRE criteria match student engagement as experienced, which appears to centre around the curriculum, and retaining aspirational criteria across broader domains that have the potential to drive engagement in previously unimagined areas.

Limitations

Our approach focused on depth rather than breadth, but we cannot exclude the possibility that expanding the geographical or cultural reach of the case studies might have provided greater depth in some areas. The interviewer and most interviewees were non-native English speakers, raising the risk of misinterpretation. Our structured approach may have given undue prominence to the domains of the ASPIRE award criteria that are not necessarily core to the phenomenon of student engagement and/or caused us to miss domains that are beyond its scope. A more phenomenographic study is warranted.

Conclusions

Student engagement appears to be conceptualised principally around the development, production and evaluation of the curriculum and the management structures that shape it, although students also engage across broader academic domains such as research and community. Our findings suggest that the ingredients, benefits, and challenges of successful student engagement are surprisingly similar across institutions in diverse sociocultural contexts. We suggest that student engagement is enhanced by: (1) participatory values that are made explicit to stakeholders and actively reinforced by senior leadership, (2) engagement activities that are driven by both students and staff, (3) engagement strategies that provide reciprocal benefits for all stakeholders, and (4) contextualised strategies that enable, empower and include.

Authors’ contributions

At the time of writing, FF was a medical student, KLG a senior educational researcher, and SS and MJC professors of medical education. FF and KLG are joint first authors. All authors contributed substantially to the project and agree to be held accountable for it.

Glossary

Student engagement: Is an active process of enablement, empowerment, and inclusion that results in student participation across diverse areas of academic practice including education, research, organisational governance, and community involvement.

Geolocation information

Europe, Asia, North America, Australia

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (579.5 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Harm Peters and the ASPIRE Academy for inspiring and supporting this study. We also thank all participants and participating schools.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Data availability statement

Our raw data is qualitative and may contain personally identifying information. We do not have permission to share this publicly.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Flávia Freitas

Flávia Freitas, MD, Medical student, Escola de Medicina, Universidade Do Minho, Braga, Portugal.

Kathleen E. Leedham-Green

Kathleen E. Leedham-Green, MBBS, BSc, MA ClinEd, Senior Education Fellow (Research), Medical Education Research Unit, Imperial College London, London, UK.

Susan F. Smith

Susan F. Smith, BSc, PhD, Emeritus Professor of Medical Education, Medical Education Research Unit, Imperial College London, UK.

Manuel João Costa

Manuel João Costa, BSc, PhD, Associate Professor of Medical Education, Escola de Medicina, Universidade Do Minho, Braga, Portugal.

References

- Appleton JJ, Christenson SL, Furlong MJ. 2008. Student engagement with school: critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychol Schs. 45(5):369–386.

- Aspire Academy. 2022. Areas of excellence to be recognised. [accessed 2022 Jan 3]. https://www.aspire-to-excellence.org/Areas+of+Excellence/.

- Bryson C. 2014. Clarifying the concept of student engagement. In: Bryson C, editor. Understanding and developing student engagement. Boca Raton (FL): Routledge; p. 21–42.

- Coates H. 2005. The value of student engagement for higher education quality assurance. Qual Higher Educ. 11(1):25–36.

- Fredricks JA, Filsecker M, Lawson MA. 2016. Student engagement, context, and adjustment: addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learn Instruct. 43:1–4.

- Greene D, David JL. 1984. A research design for generalizing from multiple case studies. Eval Program Plann. 7(1):73–85.

- Hu YL, Ching GS, Chao PC. 2012. Taiwan student engagement model: conceptual framework and overview of psychometric properties. Int J Res Stud Educ. 1(1):69–90.

- Hunt D, Klamen D, Harden RM, Ali F. 2018. The ASPIRE-to-Excellence program: a global effort to improve the quality of medical education. Acad Med. 93(8):1117–1119.

- Kahu ER. 2013. Framing student engagement in higher education. Stud High Educ. 38(5):758–773.

- Lyness JM, Lurie SJ, Ward DS, Mooney CJ, Lambert DR. 2013. Engaging students and faculty: implications of self-determination theory for teachers and leaders in academic medicine. BMC Med Educ. 13(1):1–7.

- Milles LS, Hitzblech T, Drees S, Wurl W, Arends P, Peters H. 2019. Student engagement in medical education: a mixed-method study on medical students as module co-directors in curriculum development. Med Teach. 41(10):1143–1150.

- Peters H, Zdravkovic M, João Costa M, Celenza A, Ghias K, Klamen D, Mossop L, Rieder M, Devi Nadarajah V, Wangsaturaka D, et al. 2019. Twelve tips for enhancing student engagement. Med Teach. 41(6):632–637.

- Tanaka M. 2019. The international diversity of student engagement. In: Tanaka M, editor. Student engagement and quality assurance in higher education. Boca Raton (FL): Routledge; p. 1–8.

- Trowler V. 2010. Student engagement literature review. High Edu Acad. 11(1):1–15.

- Umbach PD, Wawrzynski MR. 2005. Faculty do matter: the role of college faculty in student learning and engagement. Res High Educ. 46(2):153–184.

- Zdravković M, Serdinšek T, Sobočan M, Bevc S, Hojs R, Krajnc I. 2018. Students as partners: our experience of setting up and working in a student engagement friendly framework. Med Teach. 40(6):589–594.