Abstract

Purpose

Medical students providing support to clinical teams during Covid-19 may have been an opportunity for service and learning. We aimed to understand why the reported educational impact has been mixed to inform future placements.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of medical students at UK medical schools during the first Covid-19 ‘lockdown’ period in the UK (March–July 2020). Analysis was informed by the conceptual framework of service and learning.

Results

1245 medical students from 37 UK medical schools responded. 57% of respondents provided clinical support across a variety of roles and reported benefits including increased preparedness for foundation year one compared to those who did not (p < 0.0001). However, not every individual’s experience was equal. For some, roles complemented the curriculum and provided opportunities for clinical skill development, reflection, and meaningful contribution to the health service. For others, the relevance of their role to their education was limited; these roles typically focused on service provision, with few opportunities to develop.

Conclusion

The conceptual framework of service and learning can help explain why student experiences have been heterogeneous. We highlight how this conceptual framework can be used to inform clinical placements in the future, in particular the risks, benefits, and structures.

Practice points

There was a benefit for most students who provided clinical support compared to those who did not during Covid-19.

Most students found clinical support roles more beneficial than clinical placements and most final years wanted their final year clinical placements replaced by a formal role within a clinical team.

Not every student’s experience of clinical support was equal. The conceptual framework of service and learning can help explain this heterogeneity.

The most beneficial roles for students complemented the curriculum and provided opportunities for clinical skill development, reflective practice, and meaningful contribution to the health service.

There is an added benefit of combining service and learning if done correctly, and we can use this to inform the structure of clinical placements going forwards. However, there are risks, and we discuss principles of good practice and provide our own considerations.

Introduction

The impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (Covid-19) on medical education has been well described; however, associated sequelae such as medical students providing voluntary clinical support remain under-studied (Arora et al. Citation2020; Lucey and Johnston Citation2020; Macdougall et al. Citation2020). These roles were created around the world for medical students in early 2020, during the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic (Allan et al. Citation2020; Iacobucci Citation2020; Kinder and Harvey Citation2020; Rasmussen et al. Citation2020; Soled et al. Citation2020; The General Medical Council Citation2020; Schuiteman et al. Citation2021). Providing clinical support may have represented a unique learning opportunity for medical students, whose studies had been disrupted. However, research into medical student support has tended to focus on uptake, rather than educational benefit (Astorp et al. Citation2020; Drexler et al. Citation2020; Patel et al. Citation2020). This has also been the case in other pandemics and disasters (Byrne et al. Citation2021).

Literature exploring the educational benefit of clinical support during Covid-19 has yielded mixed findings. In a survey of 1448 final year UK medical students, the introduction of an interim foundation year one (FiY1) program improved perceived preparedness for practice (Burford et al. Citation2021). However, a study of 137 German medical students found that most final year students felt their help was unappreciated and of little value for their skill development, and it was the more junior students who generally felt appreciated and valued the experience (Drexler et al. Citation2020). In a survey of 158 students in Poland, most students felt they developed social, organizational, and stress management skills, yet only 40.5% reported development of their medical skills (Chawłowska et al. Citation2021).

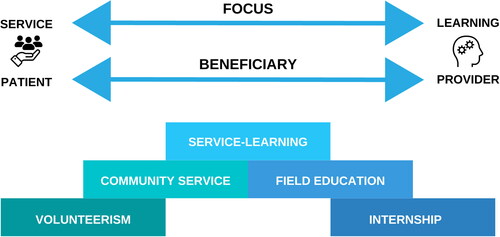

Service and learning

Student learning while also providing a useful service relates to existing theories of service and learning. Sigmon describes service and learning as a spectrum () (Sigmon Citation1997). At one end, service takes precedent over learning – examples of this include conventional volunteerism and community service, where students provide a service without the expectation of educational benefit. At this end of the spectrum, learning concerns how the service works or benefits others. At the other end of the spectrum, learning takes precedent over service – examples include field education and internships, where students are exposed to experiences relevant to their curriculum but without necessarily providing a service to others (Furco Citation1996). Service-learning exists in the middle of this spectrum, where service provision and learning are balanced (Sigmon Citation1997). While there are many varying definitions of service-learning (Felten and Clayton Citation2011), it is broadly considered a pedagogical method through which students perform and reflect on roles that both address community needs and intersect with their academic curricula (Stewart and Wubbena Citation2015). In particular, service-learning in medical education and other fields have shown benefits to students for their academic and professional skills, intra- and inter-personal skills, and social and civic responsibility (Speck Citation2001; Stewart and Wubbena Citation2015).

Figure 1. The spectrum of service and learning, adapted from Furco Furco (Citation1996).

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, there is renewed interest in learning that can also provide a service, and some authors have called for the introduction of service roles within the normal medical school curriculum (Ralston and Walsh Citation2017; Davison and Lindqvist Citation2020; Cowley and White Citation2021; Clelland and Byrne Citation2022). However, these roles are not a common part of the medical curricula, and the best structure for implementation is not known. Moreover, previous studies of service roles involving medical students have tended to focus on the educational benefits (Stewart and Wubbena Citation2015), although some studies in other disciplines have reported negative outcomes such as student disempowerment and exclusion (Speck Citation2001).

Aims and objectives

Here we explore the educational value of clinical support during the Covid-19 pandemic through the lens of service and learning. We aimed to answer the research question ‘Was provision of clinical support during the pandemic a positive learning experience for medical students and what were the reasons for this?’ By exploring why clinical support programs have been educationally beneficial (or not), we seek to explain why student experiences have been mixed, and use this to inform how service and learning could be integrated into non-pandemic curricula such as clinical placements, internships, and electives.

Methods

Research approach

We conducted this study within the paradigm of pragmatism. Pragmatism is the view that researchers should use whatever methodological approach works best for their research questions (Tashakkori and Teddlie Citation2008). The focus of pragmatic research is on answering questions and the consequences of research, rather than philosophical questions relating to the nature of reality or knowledge (Cresswell and Plano Clark Citation2011). Thus, we considered what methods would best help us answer our question regarding the educational value of clinical support during Covid-19 and the variations in experience. We designed a questionnaire to capture both quantitative and qualitative data in order to generate rich, panoramic data (Schifferdecker and Reed Citation2009) regarding experiences of clinical support during Covid-19.

Survey

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of medical students who were studying at UK medical schools during the first Covid-19 lockdown in the UK (23 March to 4 July 2020). Medical schools were identified through the UK Medical Schools Council website (Medical Schools Council Citation2020).

The link to the survey was distributed via social media, medical schools, and a collaborator at each medical school from 21 February 2021, and kept open for 6 weeks. The STROBE guideline for cross-sectional studies was followed (STROBE Initiative Citation2007), as were guidelines on collaborative research (Dowswell et al. Citation2014; Blencowe et al. Citation2018). Our study protocol was published prior to the study commencing (Byrne et al. Citation2021).

The survey was hosted on Qualtrics XM (USA) (Qualtrics Citation2021), and consisted of 55 questions for those who provided clinical support (including 10 free text questions) and 21 questions for those who did not (including 5 free text questions) (Supplemental Appendix B). The questionnaire contained items asking about demographics, clinical skills performed and opinions on education, preparedness for FY1, clinical placements, and support received. Those who provided clinical support were asked additional questions about the role they performed, opportunities for reflective practice, issues encountered and opinions on how providing clinical support: positively and/or negatively impacted learning; compared to being a medical student on a clinical placement in a similar setting; and influenced their approach to patients and views on how healthcare systems work.

Questionnaire development

Our survey was developed following the principles outlined in the Association for Medical Education in Europe guidance for developing questionnaires for educational research (Artino et al. Citation2014).

To inform the development of survey items, we reviewed relevant literature and formed a survey development group including 11 medical students, six medical education specialists, and five foundation year one (FY1) doctors.

The clinical skills were derived from General Medical Council requirements for newly qualified doctors which all UK medical schools follow (General Medical Council Citation2019), and a study of the activities that FY1 doctors routinely perform (Vance et al. Citation2019), and then prioritized in discussion within the survey development group. These skills included practical skills such as venepuncture, history and examination, communication with patients and healthcare professionals, formulating management plans, and prescription (supplemental Appendix B).

We piloted the questionnaire with 21 students, and discussed the questions with those participants to establish face and response process validity. For the pilot study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85 for questions relating to opinions on education and 0.93 for clinical skills, and was 0.86 and 0.93 for questions asked of those who did not provide clinical support and those who did, respectively. Expert validation was performed through an independent review of the study protocol and survey instrument by the UK Medical Schools Council Education Lead Advisory Group.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Oxford Interdivisional Medical Sciences Research Ethics Committee (Reference: R74003/RE001).

Quantitative analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as percentages in each category of the 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Statistical analysis was performed by JW using R (version 4.0.1) (R Core Team Citation2017). For comparisons of Likert questionnaire responses, Wilcoxon tests were performed to study differences in perceived educational benefit and skills performed between those who provided clinical support and those who did not, by year group.

To quantitatively explore the relationship between students’ views on clinical support and whether they had provided clinical support, a multiple linear regression was performed to assess the predictors of students’ perceived benefits of clinical support on their medical education/career. Regression was performed in R using lm(). Three analyses were carried out, with ‘perceived preparedness for FY1’, ‘perceived medical education benefit’ and ‘the number of clinical skills performed’. For each, initial predictors were whether the student provided clinical support or not. Covariates included: year of study, age, gender, hours spent providing clinical support per week, role (roles with <10 respondents were excluded), existing role held previously (Y/N), whether the student was a graduate entry medical student (Y/N), and whether a named supervisor was allocated.

Qualitative analysis

We used Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis to analyse qualitative responses (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, Citation2019). Six authors (LA, MELB, RF, AL, SP and RA) familiarized themselves with all data, creating initial inductive, descriptive codes. To identify themes, we used a semantic approach, analysing initial codes for patterns, then grouping, summarizing, and interpreting themes. LA checked themes and subthemes against initial codes and data, presenting any interpretative discrepancies to the group. All authors then discussed and agreed themes and subthemes.

Applying service and learning as a theoretical lens

To explore how the conceptual framework of service and learning applied to clinical support, we used a theory-informing inductive analytical approach (Varpio et al. Citation2020). To align with this approach, we first inductively analysed all data without imposing theoretical insights. Once quantitative data were analysed, and qualitative data had been grouped into preliminary categories as described above, we then applied the conceptual framework of service and learning as a ‘sensitizing concept’ (R. Patel et al. Citation2015). MHVB, MELB, LA and JCMW reviewed all original data, codes, and themes alongside this framework, exploring and discussing areas of concordance and conflict. This contributed to the definition of our themes, and the discussion of this study.

Reflexivity statement

The author team includes medical students who did and did not provide clinical support, trainee physicians, medical education researchers, and attending physicians across multiple institutions and from a wide range of backgrounds. This diversity allowed for careful consideration of different perspectives in our analysis, and this was discussed at regular meetings throughout the project.

Results

Demographics

We received responses from 1245 medical students covering 37 UK medical schools (supplemental Figure S1). 814 out of 1245 (65.3%) of participants were female and 678 out of 1146 (59.1%) of respondents identified as ‘White – British’. The modal age was 22, and modal year group was the third year of a the 5-year medical degree (n = 286, 23.0%, supplemental Figure S1).

658 out of 1148 (57.3%) of students provided clinical support. The proportion of students providing clinical support was highest among final year students (109 out of 143, 76.2%), and lowest in first year students (114 out of 224, 50.9%, supplemental Figure S1). As a consequence, there was a small difference in mean age between those who provided clinical support and those who did not (23.2 years vs. 22.4 years, respectively, p < 0.001). There was no difference in the gender distribution between those who provided clinical support and those who did not (female = 71.8% vs. 70.0%, respectively, p = 0.68). Notably, there were significantly fewer non-white students who provided clinical support compared to those who did not (21.5% vs. 33.1%, respectively, p < 0.001, supplemental Figure S1).

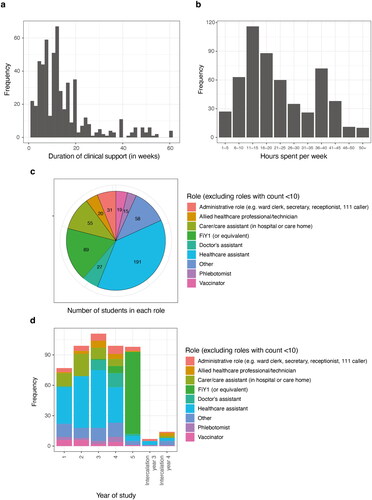

Students provided clinical support for a median of 12 weeks (IQR = 7.0-18.0 weeks), and the modal time spent per week was 11-15 h; with a second peak occurring at 36-40 h (). 89.4% (487 out of 545) of students were paid. Students performed a variety of roles. Across all year groups, the most common role was healthcare assistant (191 out of 537, 35.6%). Of final year medical students only, the most common role was interim foundation year doctor (81 out of 98, 81.8%).

Did students feel clinical support was beneficial?

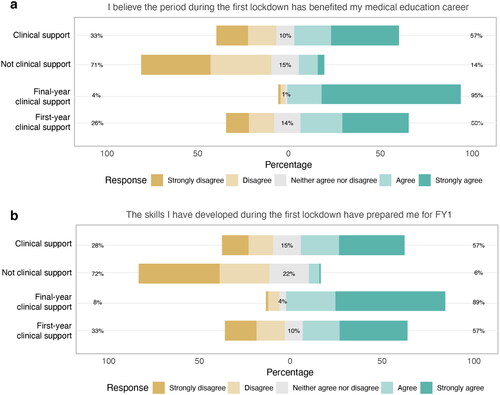

Students were asked to rate their agreement with the statement ‘I believe the period from the start of the first lockdown 23 March 2020 to 4 July 2020 has benefited my medical education/career’ and ‘the skills I have developed during the first lockdown 23 March 2020 to 4 July 2020 have prepared me for FY1’.

Students who provided clinical support found the period of the first lockdown in 2020 significantly more beneficial than those who did not (median response Likert score = 4 vs. 2, p < 0.001, Wilcoxon test, ) and felt significantly more prepared for FY1 (median Likert score = 4 vs. 2, respectively, p < 0.0001, Wilcoxon test, ). Final year students who provided clinical support found it significantly more beneficial compared to first year medical students (p < 0.0001, ).

Figure 3. Opinions on the benefit of the first lockdown period on medical education and preparedness for FY1 across all students who provided clinical support, students who did not, final-year students who provided clinical support and first-year who provided clinical support for (A) perceived benefit for medical education career, and (B) perceived preparedness for FY1.

Who benefited most from providing clinical support?

We performed a multiple linear regression to assess predictors of perceived benefit, preparedness for FY1 and number of clinical skills performed (). After controlling for confounders, we found that FiY1 was significantly beneficial for perceived benefit, preparedness, and clinical skills performed (p < 0.01), as was the duration of clinical support (p < 0.001), and having a named supervisor (p < 0.05). The Doctor’s assistant role was the only other role that was positively associated with perceived preparedness for FY1, and number of skills performed (p < 0.05).

Table 1. Multiple regression analysis of predictors of benefit for students’ medical education or career; preparedness for FY1; and aggregate clinical skills performed.

Did students find clinical support more useful than clinical placements?

55% of students found their clinical support role more useful than their role as a medical student on a clinical placement in a similar setting. There was a significant difference when comparing final and first year students (84% of final year students versus 52% of first year students, p < 0.001). 88% of final year students agreed with the statement ‘I feel final year clinical placements should be replaced with formal roles on a clinical team’. The reasons for these opinions are reflected within our qualitative data below.

How did providing clinical support influence learning?

To assess how providing clinical support influenced learning we evaluated quantitative and qualitative data through the lens of service and learning. Our quantitative data assessed whether clinical support provided opportunities to reflect and perform clinical skills. Our qualitative data aimed to understand how providing clinical support influenced students’ learning more broadly.

Opportunities to reflect

180 out of 475 (37.9%) of students who performed clinical support were provided with opportunities for reflective practice. 156 students reported the type of opportunity for reflective practice: in-person reflective discussions and portfolio logs comprised 90.0% of the reported opportunities. Students who had the opportunity to carry out reflective practice felt that it had been useful (median Likert score of 4 out of 5, n = 165). Multiple regression, controlling for year group, showed a significant association between the availability of opportunities for reflective practice and students’ perceived benefit for their medical education/career (p = 0.0001) and preparedness for FY1 (p < 0.0001).

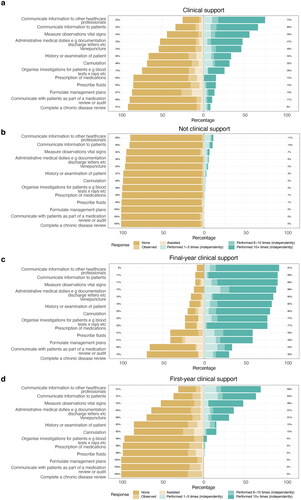

Opportunities to develop clinical skills

Medical students were asked how many times they performed various clinical skills during the first lockdown period (). Students who performed clinical support performed significantly more of every clinical skill listed on the survey than those who did not (p < 0.0001, Wilcoxon test, ), with final year students who performed clinical support performing the most clinical skills ().

Figure 4. Number of times clinical skills were performed during the first lockdown for: (A) students who provided clinical support (all year groups); (B) students who did not (all year groups); (C) Final year who provided clinical support; D) First year who provided clinical support. Data is presented as the percentage of students who performed each skill on a scale of: None, Observed, Assisted, Performed one to five times (independently), Performed six to ten times (independently), Performed 10+ times (independently).

Analysis of qualitative data through the lens of service and learning

We analysed our qualitative data using a theory-informing inductive analytical approach with service and learning as a sensitizing concept. We developed three themes for how clinical support influenced students’ learning both positively and negatively. provides illustrative quotes for these themes.

Table 2. Themes identified from qualitative analysis relating to how clinical support influenced learning.

Complementing the medical school curriculum focused on how students’ experiences positively or negatively supported the explicit and implicit learning during their medical degrees. Positive subthemes included the development of knowledge and skills such as history and examination skills, clinical and communication skills, clinical knowledge, and management of unwell patients; changing approaches to patients through an improved understanding of patients’ perspectives and a greater appreciation of holistic care; and developing personal attributes relevant to developing as a doctor, such as adaptability and confidence. Negative impacts related to a lack of support for development, such as limited educational opportunities, and less motivation or energy to study.

Impact of role on preparation for practice focused on students’ perceptions of how their clinical support role benefitted and complemented their perceived future roles. Roles were perceived to have a positive impact on learning when the role provided an authentic experience by encouraging clinical autonomy, responsibility, and team integration, while also aiding the transition to FY1 and increasing the awareness of a doctor’s role on the ward. Roles were perceived as having a negative impact on preparation for practice when the role was poorly aligned to students’ ideas of their future work as a FY1; when roles were poorly defined; or when roles had excessive physical or emotional demands.

Understanding how health systems work describes how students’ clinical support developed their understanding of how the health systems function. Respondents positively described how their practical experience of the system led to a better appreciation and respect for other health professionals and the role of the MDT approach to patient care. Students described an improved understanding of how hospital departments work on a day-to-day basis, but also as a recognition of the challenges faced by health systems such as the NHS. However, for some the perception of these challenges was pessimistic regarding the current state of the NHS – highlighting systemic underfunding and poor organization.

Discussion

During the period following the first UK lockdown due to Covid-19 in March 2020, scheduled teaching and clinical placements were suspended across all UK medical schools, and similar disruptions of studies occurred internationally (Ahmed et al. Citation2020; Rose Citation2020). While the primary intent of those offering clinical support opportunities across the world may have been service provision, in some studies, these were used to replace clinical placements (Byrne et al. Citation2021; Harvey Citation2020; Iacobucci Citation2020; Rasmussen et al. Citation2020), and for many students the motivating factor to sign up was to learn (Burford et al. Citation2021; Byrne et al. Citation2021). In our survey, students who performed clinical support reported benefits for their education and increased preparedness for FY1 compared to students who did not. While UK medical schools made alternative teaching provisions for students who did not perform clinical support roles (Arora et al. Citation2020; Dost et al. Citation2020), our findings indicate that students generally did not find these as useful compared to providing clinical support.

Despite the general benefit of clinical support, not every student’s experience was equal. The conceptual framework of service and learning can help explain this discrepancy. For some students, they provided a service and there were benefits for that student – their roles complemented the medical school curriculum, developed their understanding of the health system, provided opportunities for clinical skill development and reflective practice, and better prepared them for FY1. However, for others their role did not – although they provided a service, the relevance of the role to their education was limited, and there were few opportunities to develop. This may explain the discrepancy in experiences of clinical support seen internationally (Drexler et al. Citation2020; Burford et al. Citation2021; Chawłowska et al. Citation2021).

Final year students appeared to derive the most benefit from providing clinical support in our study. However, regression analysis showed that the driving factor was not the year of study but whether students performed the FiY1 role. This role had clear relevance to preparation for practice, a set of intended work activities defined by the UK Foundation Programme Office, and opportunities to reflect using an e-portfolio (UK Foundation Programme Citation2020). Burford et al. suggest FiY1 led to greater autonomy, perceived competence, and a sense of belonging; with students performing activities that would usually be expected during their first year as a doctor while working in similar clinical teams (Burford et al. Citation2021). The only other role that was associated with a positive impact on perceived preparedness for FY1 and number of skills performed was the Doctor’s assistant. Outside of these two roles we found students were provided with fewer opportunities to perform key skills and derived less benefit. These opportunities were often more service than learning, and may have only offered incidental learning opportunities, such as understanding how healthcare systems work (Furco Citation1996).

Some authors have suggested introducing clinical support roles as a standard component of the medical curricula as a consequence of experiences during the pandemic; and there were calls for introducing clinical support roles prior to the pandemic (such as medical students acting as healthcare assistants) (Ralston and Walsh Citation2017; Davison and Lindqvist Citation2020; Cowley and White Citation2021; Clelland and Byrne Citation2022). Indeed, our data demonstrate that most students (55%) found clinical support roles more useful than their role as a medical student on a clinical placement in a similar setting; and 88% of final year students wanted their final year clinical placements replaced by a formal role within a clinical team. However, introducing clinical support as an opportunity for service and learning in its current form may not be suitable for all students. In our study, some students experienced unfavourable outcomes – through conflict with existing educational opportunities, reduced motivation, development of negative perceptions of the health system, and negative physical and emotional experiences. There was also reduced uptake of opportunities amongst students from non-white ethnic backgrounds.

Instead, if we wish to introduce roles that combine service with learning more widely, both in the UK and internationally, there needs to be some refinement. Honnet and Poulsen describe several principles of good practice for programs that combine service and learning (Honnet and Poulsen Citation1989). These include clear responsibilities for all parties; sustained organizational commitment; provision of appropriate ‘training, supervision, monitoring, support, recognition, and evaluation to meet service and learning goals’; opportunities for reflective practice, flexible time commitment; and ensuring representation of diversity (Honnet and Poulsen Citation1989).

In addition to these recommendations, our findings suggest the importance of some additional considerations. We propose there should be careful consideration of roles offered to students within service and learning innovations, as we found students who performed roles more closely aligned with future practice reported increased benefit. Our data also support longer durations of service and learning placements as this improved perceived benefit, preparedness, and number of clinical skills performed. However, it may be challenging to integrate continuous roles into existing curricula post-pandemic, when there are competing demands for time (Stewart and Wubbena Citation2015; Wells et al. Citation2019). As such, it may be easier to implement successful service and learning interventions among senior medical students, as these students can be assigned tasks traditionally associated with the role of a first-year doctor, and often have longer clinical attachments.

The unique circumstances of medical student clinical support during Covid-19 may not represent future service and learning opportunities. However, there is an ongoing global need to implement changes that tackle the backlog in care caused by Covid-19 (van Ginneken et al. Citation2022). In the UK, the NHS as a service remains stressed – the number of doctors leaving the NHS is increasing, and there is ongoing disruption to routine and emergency care (Alderwick Citation2023). While services remain disrupted, service and learning programmes will likely be implemented within stressed healthcare systems, and student experiences of unfavourable outcomes in these programmes may persist if they are not considered. Many of the final year medical students in our study would have been about to embark on an ‘assistantship’, which is a clinical placement where final year medical students in the UK shadow junior doctors and complete most tasks expected of an FY1 doctor (Crossley and Vivekananda-Schmidt Citation2015). Yet previous studies have shown that responsibility for patient care and exposure to patients may be limited in some assistantships (Crossley and Vivekananda-Schmidt Citation2015; Jones et al. Citation2016). Following the Covid-19 pandemic, reforms of the UK undergraduate medical curriculum are expected, and these include a ‘final year six-month placement or ‘internship’’ to prepare students for foundation years (Health Education England Citation2022). As these internships will be overseen by medical schools, educators may wish to consider our recommendations alongside these reforms to optimise students’ roles, responsibilities, and patient exposure.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study are that we assessed both the positive and negative effects of clinical support and generated a rich description of both perceived and actual impact from a large cohort across all years and a wide range of UK universities.

As our study was a cross-sectional survey and asked questions about previously held clinical support roles, we cannot comment on longitudinal impact, and there is a risk that response and recall bias may have influenced our results (Sudman and Bradburn Citation1973). Future research could compare our findings with objective data from databases which track postgraduate progression – such as the UK Medical Education Database (UKMED Citation2022). Our response rate was approximately 3% of all enrolled UK medical students, and 2% for final year students (Office for Students Citation2018). As such, our sample may not be wholly representative of the UK medical student cohort as we used a convenience sampling approach, and there may also be self-selection bias. We aimed to mitigate this through anonymous responses and distributing the survey through multiple channels. The demographics of our sample appear broadly similar to the wider demographic of UK medical students (57% female and 41% non-white) (Medical Schools Council Citation2018).

There were times where we consciously deviated from Artino et al.’s survey development guidance (Artino et al. Citation2014). When this was the case, it was discussed among the survey development group and consensus was achieved. Some of our survey items used Likert scales of agreement; this may mean that items were at risk of acquiescence (Artino et al. Citation2014). We chose to do this so that direct comparisons could be made between survey items and to our previous research into medical student willingness to perform clinical support roles during Covid-19 (M. H. V Byrne et al. Citation2021). Our survey was long, therefore, there was a risk of satisficing (Artino et al. Citation2014). However, at the time of designing the survey, little was known about clinical support during Covid-19 beyond willingness to perform these roles. As clinical support is a complex topic and there was a rapidly changing environment caused by Covid-19, we felt we needed a higher level of granularity to answer our pre-defined research questions (M. H. V. Byrne et al. Citation2021). After consultations with medical schools, it was not possible to distribute multiple shorter surveys due to survey fatigue; and the single survey was of acceptable length to participants during pilot testing. We chose to make some questions double-barrelled such as ‘I believe the period during the first lockdown (23 March 2020 to 4 July 2020) has benefited my medical education/career’, as we wanted to focus on benefit for education in the most general sense. Indeed, we have shown in this study that the educational benefit of clinical support was not only limited to curricular learning.

Conclusion

There was a benefit for most students who provided clinical support compared to those who did not. However, not every student’s experience was equal. Using the conceptual framework of service and learning can help explain why there has been heterogeneity in experiences. To transform clinical support into a sustainable educational opportunity after the pandemic, medical schools should consider the risks and benefits of these opportunities, their duration, how roles can be aligned to the complement the curriculum, and structures that support service and learning.

Author contributions

The writing group (supplemental Appendix A) contributed to study conception, protocol development, data collection, data interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript. The survey development group (supplemental Appendix A) contributed to protocol development, survey development, and critical revision. The Dissemination group (supplemental Appendix A) contributed to data collection and critical revision. All authors (supplemental Appendix A) have read and approved the manuscript. RA is the guarantor.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Oxford Medical Science Interdivisional Research Ethics Committee (Reference: R74003/RE001).

Supplemental Material

Download JPEG Image (207.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (63.4 KB)Acknowledgements

PubMed citable MedEd Collaborative authors can be found in supplemental Appendix A. We would like to thank the UK Medical Schools Council, the Royal Society of Medicine Student Members Group, IncisionUK, and the ADAPT Consortium for their support in developing this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matthew H. V. Byrne

Matthew H. V. Byrne is an NIHR Academic Clinical Fellow in Urology at the Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Oxford, UK.

Laith Alexander

Laith Alexander is an Academic Foundation Doctor at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital London, UK.

Jonathan C. M. Wan

Jonathan C. M. Wan is an Academic Foundation Doctor at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital London, UK.

Megan E. L. Brown

Megan E. L. Brown is a post-doctoral researcher in medical education at the Medical Education Innovation and Research Centre, Imperial College London, UK and Senior Lecturer in Medical Education at the University of Buckingham.

Anmol Arora

Mr Anmol Arora is a final year medical student at the University of Cambridge, UK.

Anna Harvey

Anna Harvey Bluemel is an Academic Foundation Doctor at The Cumberland Infirmary, UK.

James Ashcroft

James Ashcroft is an NIHR Academic Clinical Fellow in General Surgery at Cambridge University Hospitals Trust, UK.

Andrew D. Clelland

Andrew D. Clelland is an Academic Foundation Year two doctor at Cambridge University Hospitals Trust, UK.

Siena Hayes

Siena Hayes is an intercalating year medical student at Cardiff University School of Medicine, Cardiff University, UK

Florence Kinder

Florence Kinder is a 5th year medical at Leeds University, UK

Catherine Dominic

Catherine Dominic is a 4th year medical student at Barts and the London, UK.

Aqua Asif

Aqua Asif is a 5th year medical student at the University of Leicester, UK.

Jasper Mogg

Jasper Mogg is an Internal Medical Trainee at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, UK.

Rosie Freer

Rosie Freer is a junior doctor at the Royal Free Hospital, London, UK.

Arjun Lakhani

Arjun Lakhani is a junior doctor at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London, UK.

Samuel Pace

Samuel Pace is a junior doctor at Newham University Hospital, London, UK.

Soham Bandyopadhyay

Soham Bandyopadhyay is an Academic Foundation Year two doctor at the Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Oxford, UK.

Nicholas Schindler

Nicholas Schindler is a tutor at the Institute of Continuing Education at the University of Cambridge and a consultant paediatrician at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals Foundation Trust, UK.

Cecilia Brassett

Professor Cecilia Brassett is the Teaching Professor of Human Anatomy, Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience, University of Cambridge.

Bryan Burford

Bryan Burford is a Lecturer in Medical Education at Newcastle University, UK.

Gillian Vance

Professor Gillian Vance is Professor of Medical Education at Newcastle University, UK.

Rachel Allan

Rachel Allan is Deputy academic lead for undergraduate primary care teaching, MedEd Collaborative is a trainee and student led medical education research collaborative.

References

- AhmedH, AllafM, ElghazalyH. 2020. COVID-19 and medical education. Lancet Infect Dis. 20(7):777–778.

- AlderwickH. 2023. Rhetoric about NHS reform is misplaced. BMJ. 380:54.

- AllanR, PaceS, FreerR, EasdaleM. 2020. Primary care student volunteering: lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Brit J Gen Pract. https://bjgp.org/content/primary-care-student-volunteering-lessons-learned-covid-19-pandemic

- AroraA, SolomouG, BandyopadhyayS, SimonsJ, OsborneA, GeorgiouI, DominicC, MahmoodS, BadhrinarayananS, AhmedSR, et al. 2020. Adjusting to Disrupted Assessments, Placements and Teaching (ADAPT): a snapshot of the early response by UK medical schools to COVID-19. MedRxiv.

- ArtinoAR, La RochelleJS, DezeeKJ, GehlbachH. 2014. Developing questionnaires for educational research: AMEE Guide No. 87. Med Teach. 36(6):463–474.

- AstorpMS, SørensenGVB, RasmussenS, EmmersenJ, ErbsAW, AndersenS. 2020. Support for mobilising medical students to join the covid-19 pandemic emergency healthcare workforce: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMJ Open. 10(9):e039082.

- BlencoweN, GlasbeyJ, HeywoodN, KasivisvanathanV, LeeM, NepogodievD, WilkinR, AllenS, BorakatiA, BosanquetD, et al. 2018. Recognising contributions to work in research collaboratives: guidelines for standardising reporting of authorship in collaborative research. Int J Surg. 52:355–360.

- BraunV, ClarkeV. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3(2):77–101.

- BraunV, ClarkeV. 2019. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 11(4):589–597.

- BurfordB, VanceG, GouldingA, MattickK, CarrieriD, GaleT, BrennanN. 2021. 2020 Medical Graduates: the work and wellbeing of interim Foundation Year 1 doctors during COVID-19 Final report. London (UK) General Medical Council.https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/fiy1-final-signed-off-report_pdf-86836799.pdf

- ByrneMHV, AshcroftJ, AlexanderL, WanJCM, AroraA, BrownMEL, HarveyA, ClellandA, SchindlerN, BrassettC. 2021. COVIDReady2 study protocol: cross-sectional survey of medical student volunteering and education during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom. BMC Med Educ. 21(1):211.

- ByrneMHV, AshcroftJ, AlexanderL, WanJ, HarveyA. 2021. A systematic review of medical student willingness to volunteer and preparedness for pandemics and disasters. Emerg Med J. 39: e6.

- ByrneMHV, AshcroftJ, WanJCM, AlexanderL, HarveyA, SchindlerN, BrownMEL, BrassettC. 2021. Examining medical student volunteering during the COVID-19 pandemic as a prosocial behavior during an emergency. MedRxiv. DOI:10.1101/2021.07.06.21260058.

- ChawłowskaE, StaszewskiR, LipiakA, GiernaśB, KarasiewiczM, BazanD, NowosadkoM, CoftaM, WysockiJ. 2021. Student volunteering as a solution for undergraduate health professions education: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 8:1100.

- ClellandAD, ByrneMHV. 2022. The educational impact and necessary supporting structures should be understood before mandating healthcare support worker roles for medical undergraduates. Med Teach. 44(12):1425–1426.

- CowleyS, WhiteG. 2021. Healthcare support worker assistantships should form a mandatory part of medical school curricula: a perspective from UK medical students. Med Teach. 43(9):1092–1093.

- CresswellJ, Plano ClarkV. 2011. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd ed.. Thousand Oaks (CA): sage Publications.

- CrossleyJGM, Vivekananda-SchmidtP. 2015. Student assistantships: bridging the gap between student and doctor. Adv Med Educ Pract. 6:447–457.

- DavisonE, LindqvistS. 2020. Medical students working as health care assistants: an evaluation. Clin Teach. 17(4):382–388.

- DostS, HossainA, ShehabM, AbdelwahedA, Al-NusairL. 2020. Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. BMJ Open. 10(11):e042378.

- DowswellG, BartlettDC, FutabaK, WhiskerL, PinkneyTD. 2014. How to set up and manage a trainee-led research collaborative. BMC Med Educ. 14(1):1–6.

- DrexlerR, HambrechtJM, OldhaferKJ. 2020. Involvement of medical students during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey study. Cureus. 12(8):e10147.

- FeltenP, ClaytonPH. 2011. Service-learning. New Dir Teach Learn. 128:75–84.

- FurcoA. 1996. Service-learning: a balanced approach to experiential education the service-learning struggle. In: TaylorB, editor. Expanding boundaries: serving and learning. Washington (DC): Cooperative Education Association. p. 2–6.

- General Medical Council. 2019. Practical skills and procedures. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/practical-skills-and-procedures-a4_pdf-78058950.pdf

- General Medical Council. 2020. The state of medical education and practice in the UK 2020. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/somep-2020_pdf-84684244.pdf?la=en&hash=F68243A899E21859AB1D31866CC54A0119E60291

- HarveyA. 2020. Covid-19: medical schools given powers to graduate final year students early to help NHS. BMJ. 368:m1227.

- Health Education England. 2022. Future workforce goal. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.hee.nhs.uk/about/work-us/hee-business-plan-202223/our-goals-objectives/future-workforce-goal.

- HonnetEP, PoulsenSJ. 1989. Principles of good practice for combining service and learning: a wingspread special report. https://nsee.memberclicks.net/assets/docs/KnowledgeCenter/EnsuringQuality/BooksReports/183. principles_of_good_practice_for_combining_service_and_learning.pdf.

- IacobucciG. 2020. Covid-19: medical schools are urged to fast-track final year students. BMJ. 368:m1064.

- JonesOM, OkekeC, BullockA, WellsSE, MonrouxeLV. 2016. ‘He’s going to be a doctor in August’: a narrative interview study of medical students’ and their educators’ experiences of aligned and misaligned assistantships. BMJ Open. 6(6):e011817.

- KinderF, HarveyA. 2020. Covid-19: the medical students responding to the pandemic. BMJ. 369:m2160.

- LuceyCR, JohnstonSC. 2020. The transformational effects of COVID-19 on medical education. JAMA. 324(11):1033–1034.

- MacdougallC, DangerfieldP, KatzD, StrainWD. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on medical education and medical students. How and when can they return to placements? MedEdPublish. 9:159.

- Medical Schools Council. 2018. Selection alliance 2018 report an update on the Medical Schools Council’s work in selection and widening participation. https://www.medschools.ac.uk/media/2536/selection-alliance-2018-report.pdf

- Medical Schools Council. 2020. Medical schools. https://www.medschools.ac.uk/studying-medicine/medical-schools

- Office for Students. 2018. Medical and dental target intakes.[accessed 2023 Jan 21] https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/funding-for-providers/health-education-funding/medical-and-dental-target-intakes/

- PatelJ, RobbinsT, RandevaH, de BoerR, SankarS, BrakeS, PatelK. 2020. Rising to the challenge: qualitative assessment of medical student perceptions responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Med (Lond). 20(6):E244–E247.

- PatelR, TarrantC, BonasS, YatesJ, SandarsJ. 2015. The struggling student: a thematic analysis from the self-regulated learning perspective. Med Educ. 49(4):417–426.

- Qualtrics. 2021. Qualtrics. [accessed 2022 Jan 6] https://www.qualtrics.com/

- R Core Team. 2017. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/

- RalstonC, WalshC. 2017. Medical students would benefit from working as healthcare assistants. [accessed 2022 Mar 2]. BMJ Opinion website. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2017/08/18/charlotte-ralston-medical-students-would-benefit-from-working-as-healthcare-assistants/

- RasmussenS, SperlingP, PoulsenMS, EmmersenJ, AndersenS. 2020. Medical students for health-care staff shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 395(10234):e79–e80.

- RoseS. 2020. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA. 323(21):2131–2132.

- SchifferdeckerKE, ReedVA. 2009. Using mixed methods research in medical education: basic guidelines for researchers. Med Educ. 43(7):637–644.

- SchuitemanS, IbrahimNI, HammoudA, KrugerL, MangrulkarRS, DanielM. 2021. The role of medical student government in responding to COVID-19. Acad Med. 96(1):62–67.

- SigmonRL. 1997. Linking service with learning in liberal arts education. http://www.cic.edu/newspubs/pubs/sigmon94/sigmon94.shtml

- SoledD, GoelS, BarryD, ErfaniP, JosephN, KochisM, UppalN, VelasquezD, VoraK, ScottKW. 2020. Medical student mobilization during a crisis: lessons from a COVID-19 medical student response team. Acad Med. 95(9):1384–1387.

- SpeckBW. 2001. Why service-learning? Why service-learning? New Direct Higher Educ. 2001(114):3–13.

- StewartT, WubbenaZC. 2015. A systematic review of service-learning in medical education: 1998–2012. Teach Learn Med. 27(2):115–122.

- STROBE Initiative. 2007. STROBE checklist for cross-sectional studies. [accessed 2022 Mar 17]. https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/strobe/

- SudmanS, BradburnNM. 1973. Effects of time and memory factors on response in surveys. J Am Stat Assoc. 68(344):805–815.

- TashakkoriA, TeddlieC. 2008. Mixed methodology: combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications.

- UK Foundation Programme. 2020. Foundation interim year 1 (FiY1) training operational guide. https://london.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/ukfpo_fiy1_training_operational_guide_2020.pdf

- UKMED. 2022. UK medical education database. [accessed 2022 Jan 6]. https://www.ukmed.ac.uk/

- van GinnekenE, ReedS, SicilianiL, EriksenA, SchlepperL, TilleF, ZapataT. 2022. Addressing backlogs and managing waiting lists during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/addressing-backlogs-and-managing-waiting-lists-during-and-beyond-the-covid-19-pandemic

- VanceG, JandialS, ScottJ, BurfordB. 2019. What are junior doctors for? The work of Foundation doctors in the UK: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 9(4):e027522.

- VarpioL, ParadisE, UijtdehaageS, YoungM. 2020. The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. Acad Med. 95(7):989–994.

- WellsSE, BullockA, MonrouxeLV. 2019. Newly qualified doctors’ perceived effects of assistantship alignment with first post: a longitudinal questionnaire study. BMJ Open. 9(3):e023992.

Appendix A.

MedEd Collaborative Authorship (all co-authors PubMed citable):

Writing group

Matthew H V Byrne, Laith Alexander, Jonathan C M Wan, Megan E L Brown, Anmol Arora, Anna Harvey, James Ashcroft, Andrew Clelland, Siena Hayes, Florence Kinder, Catherine Dominic, Aqua Asif, Jasper Mogg, Rosemary Freer, Arjun Lakhani, Samuel Pace, Soham Bandyopadhyay, Nicholas Schindler, Cecilia Brassett, Bryan Burford, Gillian Vance, Rachel Allan (Overall guarantor).

Quantitative analysis

Jonathan C M Wan (Lead statistician)

Qualitative analysis

Laith Alexander (Lead qualitative analyst), Rosemary Freer, Arjun Lakhani, Samuel Pace, Megan E L Brown, Rachel Allan.

Survey development group

Matthew H V Byrne (Chair), Gillian Vance, Bryan Burford, Cecilia Brassett, Vigneshwar Raj, Soham Bandyopadhyay, Catherine Dominic, Siena Hayes, Aleksander Dawidziuk, Florence Kinder, Sanskrithi Sravanam, Michal Kawka, Adam Vaughan, Oliver P Devine, Aqua Asif, Jasper Mogg, Megan E L Brown, Laith Alexander, Jonathan C M Wan, Anna Harvey, James Ashcroft, Andrew Clelland, Anmol Arora, Nicholas Schindler, Rachel Allan.

Dissemination group

Andrew Clelland (Chair), Matthew H V Byrne, Catherine Dominic, Florence Kinder, Siena Hayes, Aqua Asif, Jasper Mogg, Soham Bandyopadhyay. Medical student collaborators: Ailsa McKinlay, Aimee Wilkinson, Amy X Li, Anna Harvey, Aqua Asif, Beth Jones, Beth Selwyn, Catherine Dominic, Dania Badran, Éabha Lynn, Eleanor Deane, Elif Gecer, Emily Murphy, Florence Kinder, Francis Beynon, Jane Harding, Khadeeja Mustafa, Lukschana Senathirajah, Malvika Subramaniam, Marina Politis, Martin Carr, Megan O'Doherty, Naomi Slater, Nicholas Kelly, On Yu Lee, Paaras Doshi, Rebecca S Bates, Robyn Spibey, Samantha Green, Siena Hayes, Simon Rey, Srishti Sarkar, Thomas Franchi, William A Cambridge. Postgraduate year one collaborators: Abu Sufian, Adam Vaughan, Akosua Ofosu-Asiedu, Benjamin J Fox, Christopher Gilmartin, Eka Melson, Fatemeh Nokhbatolfoghahai, Filip Brzeszczynski, Jack Jameson, Jessica Pieri, Laith Alexander, Nithesh Ranasinha, Sachin Ananth, Shamus Butt, Srishti Sarkar, Stephanie D'Costa, Ziyan Kassam.