Abstract

Healthcare experiences of mistreatment are long standing issues, with many not knowing how to recognise it and respond appropriately. Active bystander intervention (ABI) training prepares individuals with tools and strategies to challenge incidences of discrimination and harassment that they may witness. This type of training shares a philosophy that all members of the healthcare community have a role to play in tackling discrimination and healthcare inequalities. We developed an ABI training programme for undergraduate medical students, after recognising the need for this given the students’ adverse experiences on clinical placements. From longitudinal feedback and robust observations of this programme, this paper intends to provide key learning lessons and guidance on how to develop, deliver and support faculty in facilitating these types of trainings. These tips are also accompanied by recommended resources and suggested examples.

Introduction

‘I didn’t know what to say’ is an all-too-common response when considering how to challenge incidences of discrimination and harassment in the clinical environment, particularly for medical students (Sotto-Santiago et al. Citation2020). Little guidance exists as to how faculty should best equip students to effectively challenge these situations (Fnais et al. Citation2014; Acholonu et al. Citation2020). A bystander is an individual who observes when an incident such as discrimination, harassment, bullying, or microaggression occurs, but is not involved the situation (Lansbury Citation2014). Conversely, an active bystander participates in a discriminatory incident by assessing the situation, considering what help might be appropriate and intervenes to challenge unacceptable behaviour (Wilkins et al. Citation2019). The degree of activeness a bystander may assert will be influenced by contextual factors such hierarchy, power dynamics, notions of professionalism and conformity and the perceived time available (Scully and Rowe Citation2009; Altabbaa et al. Citation2021). Following the success of Norwich Medical Schools’ implementation of ABI training, the Universities UK advisory group proposed the use of ABI training to better equip students with the skills and confidence required to make a positive impact in the medical field and improve future attitudes (Universities UK Citation2020). Furthermore, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education in the United States of America was instructed to address experiences of mistreatment and abuse in healthcare by developing and delivering appropriate faculty development trainings (Schenning and Tseng Citation2013).

Previous research on ABI training has focussed on preventing and reducing sexual violence (Banyard Citation2011; Vukotich Citation2013; Fenton et al. Citation2015; Coker et al. Citation2017; Powers and Leili Citation2018; Mujal et al. Citation2021). Bystander intervention campaigns, rather than explicit training, have been suggested to reduce sexual attacks, as students who saw the campaign reported that they would be more likely to intervene (Sundstrom et al. Citation2018). Additionally, ABI training has been proposed to reduce victimisation and passive bystander behaviours when used to minimise aggression in schools (Pfetsch et al. Citation2011) and improves student understanding of reporting incidents (Brokenshire Citation2015). ABI training is also suggested to have positive short-term outcomes for health care staff in the military, with participants reporting an increased self-efficacy and intentions to be active bystanders in the future (Relyea et al. Citation2020). Whilst the benefits of ABI training are clear (Bell et al. Citation2019), there are continued uncertainties as to how to develop, deliver and support faculty in facilitating training for medical students in all clinical settings (e.g. hospitals and general practice surgeries).

At the University of Edinburgh, we developed a bespoke ABI training programme for undergraduate medical students, with regular involvement and engagement with students and faculty throughout the planning process; details of this programme are shown in . Student feedback identified two primary reasons for not being an active bystander, these were: (1) the perceived lack of empowerment and responsibility in challenging unprofessional behaviour and (2) the apparent absence of skills to appropriately challenge discriminatory incidences. This programme intended to enable medical students to recognise, respond, and reflect upon unacceptable and discriminatory behaviours they may observe. Additionally, this programme continues to be developed, delivered, and adapted for use at the University of Edinburgh and also the University of Oxford. The twelve tips that follow aim to support and guide educators in developing, delivering, and supporting faculty involved in ABI trainings.

Tip 1

Critically self-reflect on what motivates and prevents active bystander interventions

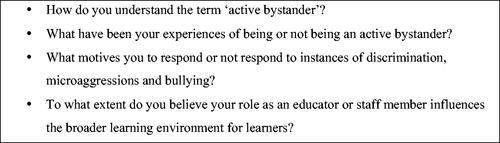

A pre-requisite for empowering and supporting faculty involves first acknowledging and critically reflecting upon their own experiences in being (or not being) an active bystander; in particular what motivates and prevents them to respond to incidents of discrimination. This aligns with bystander literature which highlights that there are often five key motivators, namely the interpretation of harm in the situation, emotional reactions, social evaluating (considering the context and the social dynamics at play), moral evaluating (reflecting on what is perceived as the ‘right thing to do’), and intervention self-efficacy (Kristoffersson and Hamberg Citation2022). Additionally, the literature illustrates reasons for not intervening include power positioning and dynamic, lack of knowledge or personal experiences with the issue and battle fatigue (the stress associated with microaggressions that cause various forms of emotional and physical strain) (Smith Citation2004). Supporting faculty in regularly undertaking self-reflective exercises may help in highlighting any assumptions or unconscious biases they may have in how to be an active bystander. Such reflection does not occur in a vacuum and should be stimulated by discussions as part of a faculty team as well. provides an example of self-reflective questions that can be used.

Tip 2

Actively engage faculty and students from under-represented and marginalised groups

Meaningfully involving and engaging faculty and students from under-represented and marginalised backgrounds provides valuable insights into personal lived experiences, relevant and current issues, strategies, support networks, and contributes to providing a sense of authenticity to the discussions. Underrepresented and marginalised groups can share issues they have personally been affected by and this can help guide the session towards the necessary learning intentions. We suggest a collaborative approach that does not overburden members of these groups with responsibility but rather aims to actively learn from their experiences and insights. Involving students in the development and facilitating of these trainings can be beneficial because they are likely to offer different perspectives to faculty. They may also have more relatable lived experiences which can enhance group discussions and empower their peers; thereby encouraging group dialogue. In the trainings we delivered, we made an active effort to involve students from ethnic minority and LGBT+ student societies. Additionally, we invited minority group members to comment on designed materials, observe pilot sessions and provide feedback.

Tip 3

Foster a safe and supportive environment for each training session

Discussing differences can be both enriching and conflicting. Creating a safe and supportive learning environment is essential for capitalising on the diversity of students’ experiences and perspectives. Learners are more willing to engage in the sessions if they feel safe and comfortable in the teaching environment (Relyea et al. Citation2020). A supportive environment also promotes wellbeing in challenging discussions, particularly for those with lived experience of prejudice and discrimination. Nonconformity, in this case through becoming an active rather than a passive bystander, is uncomfortable (Altabbaa et al. Citation2021); therefore, the acknowledgment and validation of such uncomfortable emotions must be explicitly discussed throughout ABI training sessions to enhance student empowerment. In the following discussion, we suggest several measures that can help facilitators to foster a safe and supportive environment during ABI training sessions.

During the pre-brief, facilitators should reassure learners that all contributions will be appreciated and received in good judgement. Spending time before the session to clarify the workshop expectations is beneficial because it enables the facilitators to establish the session tone, which is more likely to result in constructive open discussions. Highlighting confidentiality standards and that all views can be expressed without fear of repercussions can be helpful in encouraging every student to participate, thereby encouraging more diverse and enriched discussions. It is also important to clarify what behaviours will not be tolerated. For example, participants should be informed that the use of slurs or derogatory language – even in talking about scenarios – is not acceptable. Furthermore, facilitators should explicitly state that participants can leave the session at any point and support should be offered to any students who do so. Facilitators were also careful to point out that the scenarios were real and may seem shocking, but they were all based on the recent experiences of students and clinicians. Conducting a brief before the session is a good opportunity for facilitators to be perceived by students as open and non-judgmental. The relationship between learner and facilitator can also be strengthened by facilitators sharing their own experiences and outlook. Facilitators who are approachable, non-threatening, encouraging and open-minded are suggested to be received best by students (Boscardin Citation2015). Subsequently, students are likely to be more willing to participate and thus benefit from the session (Boscardin Citation2015).

Participation may also be enhanced through organising an informal activity before the training begins, whereby participants and facilitators have a chance to interact without pressure. The hierarchical structure of medical contexts often prevents a two-way conversation between faculty and students (Krackov Citation2011); therefore, removing this structure at the beginning of the session is important to ensure effective discussions can occur. The activity can be a simple introduction such as asking participants to share their name and pronouns (if they so wish) but could also include other neutral information such as an interesting fact about themselves or their favourite animal or food. Discussion starters and ice-breaker activities may be helpful in encouraging initial conversations on diversity; the University of Lausanne, Switzerland provides some helpful example exercises (Fenley and Daele Citation2011).

Tip 4

Develop scenarios based on real life examples

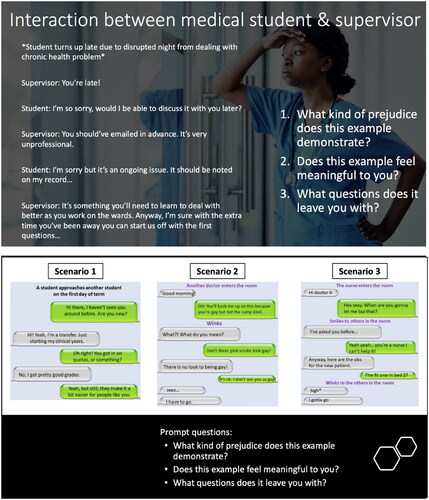

Actively involving a variety of stakeholders in the ABI training process can also help to provide a wide range of personal experiences that can be used as case studies in training sessions. ABI training can be more relatable and realistic through case studies and scenarios from real experiences adapted to the learning setting. Learners may find that adopting the perspective of the victim, perpetrator or bystander provides greater understanding of discrimination and discrimination denial (Todd et al. Citation2012). Analysis of the events may also become more pertinent and discussion more engaging when addressing real cases. Furthermore, whilst students often blame passive bystanders for inaction, this blame is suggested to be dependent on the bystander’s knowledge of the offender’s intentions, the degree to which the students identify with the bystander, and the possible alternative behaviours that the bystander could have decided upon (Holtzman Citation2021). Thus, using real life examples can facilitate and enrich discussions, as different students may place varying degrees of blame on the bystander. Exploring why people perceive scenarios differently may support the effectiveness of the ABI training, as students can reflect and develop greater understanding of bystander behaviour. shows examples of some of the real-life case studies and scenarios that were created for use in the ABI sessions delivered at Edinburgh and Oxford. It is interesting to note that the first time we used these scenarios, some students, often those who were not from marginalised groups, commented that the scenarios seemed ‘dramatic’ even though they were based on medical students’ and staff real life experiences, including the language used in real life. In more advanced follow-up sessions, we also made use of open access case studies created by Sandoval et al. (Citation2020).

Tip 5

Consider including scenarios and activities on various forms of discriminations

Scenarios and case studies which are presented during ABI training should include learning points about a variety of forms of discrimination and prejudice such as racism, homophobia, transphobia, sexism, ableism, and body shaming. The discussions and sharing of experiences that can arise from these scenarios can help to cultivate the tools and strategies (e.g. establishing professional boundaries, being aware of reporting structures or platforms to raise concerns or considering how to ask questions in a way that supports an individual to reflect upon their own behaviour) students require to challenge unprofessional behaviour. It is important to understand that some forms of unprofessional behaviour are subtle and hence might not be as easily recognisable as others. Raising awareness of different forms of discrimination will enable the students to better notice and act upon incidents they experience in their own life. Sotto-Santiago et al. (Citation2020), Acholonu et al. (Citation2020), and Wilkins et al. (Citation2019) papers (in their supplementary appendices) provide a range of case scenarios and workshop activities that can be used to diversify the content of ABI trainings. Furthermore, the Whitgob et al. (Citation2016) paper exploring strategies to address discrimination towards trainees includes a variety of case scenarios (table 1, page s65) and recommended strategies for trainees and faculty development (chart 1, page s68).

Tip 6

Design sessions that are highly interactive

Establishing a safe and welcoming environment during the ABI training sessions also encourages participation (Relyea et al. Citation2020). Participation can empower and help students to perceive themselves as equipped and capable of active bystander behaviours. It is therefore important to make sessions interactive, especially if they are conducted online, as group discussions and personal interactions are some of the most useful elements of ABI training (Relyea et al. Citation2020). Ensuring that the sessions are highly interactive thus becomes paramount in delivering effective training, as the quality of ABI training is directly correlated with the outcomes (Pfetsch et al. Citation2011).

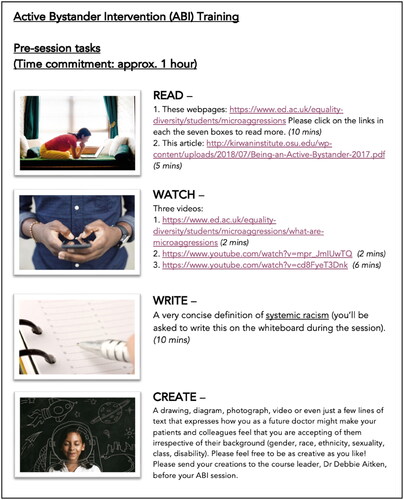

One way of increasing participation during ABI training sessions is through ensuring that time for discussions and questions is prioritised. Interactive sessions can also be promoted through providing students with pre-session materials on the subjects that will be discussed. Adopting a flipped classroom approach and advocating that learners review essential knowledge and learning intentions should be a part of the pre-session materials (an example is shown in ) so it is clear to learners what they should be gaining from the session. Background knowledge enables learners to have more confident and insightful conversations about the topics and have a better overview of what to expect from the session.

If training is conducted online through platforms such as Microsoft Teams, Blackboard, or Zoom, participants should be encouraged by the facilitators to use a ‘gallery view’ which displays all the participants in a grid pattern on the screen. This can help to increase engagement and allows the facilitator to gain a better understanding of the group.

Tip 7

Facilitate small group sessions

To maximise interaction and discussion, the number of participants should be limited, as it has been suggested that smaller groups facilitate more meaningful discussions (Pollock et al. Citation2011). Ideally, around 20 students should be present for each session, allowing for five breakout groups with four students in each. The smaller groups can then nominate a spokesperson to feed-back a summary of the discussion to the whole group.

Ensuring that groups are not too big is conducive to creating an atmosphere where students are comfortable enough to participate and share their thoughts, as well as providing more opportunities for all students to be empowered and voice their opinions. Logistically, this practice can also be beneficial for completing interactive workshops in the allotted time.

Tip 8

Encourage a reflective environment

Reflection is an essential part of consolidating knowledge and new understanding (Mann et al. Citation2009). Providing dedicated time for participants to reflect on the workshop and the new skills and principles they have been exposed to can be helpful in equipping students to target discrimination and bias. Tools such as reflective journaling, storytelling and creative enquiry can help encourage meaningful reflection (Sandars Citation2009). Participants could also be encouraged to link what they have learnt to their portfolios and use it as part of their professional development. Having documented reflection will also aid in recognising and acknowledging the students’ personal development and whether they now feel equipped to be an active bystander. It is also useful to signpost local support networks that can continue supporting the students in managing and challenging these issues. The University of San Francisco produced ‘expert resources and a guide to LGBT inclusivity in the classroom’ (Greggory Citation2008) which can be a helpful resource when considering how to be supporting conversations on this topic. Additionally, the University of Toronto, Centre for Teaching Support and Innovation developed several resources for educators who wish to ensure that their courses and classrooms are inclusive to as many students as possible. Available at: https://teaching.utoronto.ca/communities-and-conversations-series/

Tip 9

Share lessons learned

At the end of the session, time should be allocated for sharing lessons learned; some questions could include: (a) What are you taking away from this session? (b) How has this session changed your understanding of what it means to be an active bystander? This can involve summarising the topics discussed, the active bystander skills taught, and inviting participants to share any questions or concerns. Additionally, this part of the session should acknowledge any challenging areas of discussion and affirm that there is no one way to be an active bystander; it is a long-term process of development and learning. It is also relevant to have a safeguarding mechanism to ensure that the learners have appropriate support after the session. Providing information about reporting structures and signposting to contact information for helplines or websites can help to create this sense of support. Furthermore, one of the most important parts of the end of the session is to allow time for educators/faculty to talk to each other about their own experiences and stories of prejudice and its personal impact. These sessions can be both emotional and empowering because faculty may be sharing so much more about themselves than they would in other teaching sessions. For some LGBTQ+ educators/faculty, it felt risky (but often at the same time empowering) to say to a room full of medical students: ‘I am an LGBTQ+ person’ or to talk about their experiences of microaggressions in order to help the students to feel that they too could open up about their experiences. Ultimately, most of the educators/faculty felt it was worth it in order to get such rich discussion going, but there was still an emotional toll that other ‘non minority/marginalised group’ colleagues do not have to experience. These discussions should be reflective and analytical, rather than simply describing what happened in the session (Altabbaa et al. Citation2021). Challenges/barriers to being active bystanders should be discussed, as well as taking the opportunity to think about the psychological and maybe even ‘physical’ calculated risks (perceived and potentially unperceived). We found that by discussing these issues as facilitators/faculty, we were better equipped to deal with these discussions with students in future sessions.

Tip 10

Embed continuity in the delivery of ABI training

The process of implementing a change in behaviour and empowering medical students to become active bystanders is complex and requires time. One-off sessions of ABI training for the prevention of sexual violence have been shown to be ineffective at changing behaviour in the long term (Fenton et al. Citation2016). Furthermore, short-term ABI training is suggested to be no more effective than not providing any training (Pfetsch et al. Citation2011). Instead, teaching students to respond to discrimination and bias over several sessions, ideally over their medical education, can be more effective (The Behavioural Insights Team Citation2020).

Consistent exposure to the ideas and principles behind active bystander intervention (ABI) can help cement understanding and skills. Regular workshops also offer students the opportunity to share any current issues that they have seen or experienced as part of their medical training so that they can gain insight into relevant strategies and tools (Meyer and Zelin Citation2019). Subsequent sessions should build on previous knowledge and the scenarios discussed should increase in complexity so that the ABI training coincides with the students’ development (Dong et al. Citation2018).

Tip 11

Evaluate the sessions, listen to feedback, and make dynamic changes

Course evaluation is a crucial part of programme development. We found that developing a system of consistent evaluation and adaptation was central to creating an effective ABI training plan. We provided opportunities for students and faculty to share their feedback and opinions, through anonymous surveys and sharing the course leader’s contact details for feedback, which helped us refine the content of sessions, and ensure that the intended aims of the programme were reached. Session facilitators also took responsibility for monitoring the sessions and debriefing after sessions to communicate areas for improvement. For example, after noticing that the allotted time did not allow for students to sufficiently discuss all the scenarios, facilitators in our programme decided to adapt the sessions so that each group only discussed one scenario at a time and then presented the key points to the whole group. One of the key examples of changes we as authors made in response to feedback was trying to ensure that we had a diverse representation amongst the two lead educators/faculty. Students of colour felt that (and fed back to us that) it was important to have educators/faculty members of colour leading the discussions around race. We were reluctant to put pressure on the people of colour in the faculty, which is why we started to develop a student faculty (many of whom were recruited from Edinburgh’s BAME Medics and LGBTQ+ Medics societies) to address this issue.

Tip 12

Keep up to date with the current cultural, political, and social climate

Keeping up to date with current cultural, political, and social issues ensures ABI trainings are current and inclusive (Dutta et al. Citation2021). Recent social movement such as Black Lives Matter, the MeToo campaigns, and COVID-19 pandemic have drastically shaped and resurfaced critical issues for medical schools to address. ABI training necessitates faculty to remain up to date on current cultural, political, and social changes that may influence discussions on when and how to be an active bystander and the degree of activeness one may assert. Medical students traditionally inhabit a social space governed by hierarchies, power dynamics and entrenched social norms and expectations which all influence their notions of active bystander behaviours. Often minimal attempt has been made to acknowledge the way students have been influenced by the social context in which they are embedded. A student’s intersecting identities and social contexts may also afford them differing levels of privileges in a bystander situation which may influence reluctance to intervene. Training all students and harnessing lived experiences in teaching materials helps the more privileged to identify forms of discrimination, preventing an overburdening of minorities.

Conclusions

Being an active bystander is part of every healthcare professional’s role. Developing, delivering, and supporting faculty in facilitating discussions on ABI is a major step towards tackling discrimination and prejudice in the medical and healthcare field. The twelve tips in this article are designed to support educators and facilitators in empowering their students to reduce and challenge discrimination in the clinical settings, which will subsequently have a positive impact on all healthcare professional members and the treatment of their patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following contributors who developed and delivered the ABI training: Dr Elizabeth Andargachew, Dr Kate Macfarlane, Dr Marie Mathers, Dr Charu Chopra, Dr Ingrid Young, Mr Azeem Merchant, Dr Thom O’Neill, Dr Agata Dunsmore, Mrs Phillipa Burns, Dr Callum Cruickshank, Ms Lorraine Close, Dr Ailsa Hamilton, Dr Chenai Mautsi, Ms Elsbeth Dewhirst, Dr Callum Mutch, Dr James Millar, and Dr Zain Hussain.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Debbie Aitken

Debbie Aitken (she/her), BA, MA, PGCE, MSc, PGCAP, PhD, PFHEA, is the Director of the MSc in Medical Education and a Fellow of Harris Manchester College at the University of Oxford. She was previously a Senior Lecturer in Medical Education, Director of Clinical Educator Programme (CEP), and Lead for MBChB Bystander & Diversity training at the University of Edinburgh Medical School.

Heen Shamaz

Heen Shamaz (she/her), is a third year medical student at The University of Edinburgh intercalating in Surgical Sciences. Currently, she is the President of Edinburgh University’s Black Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) Medics Society.

Abha Panchdhari

Abha Panchdhari (she/her), is a third year medical student at the University of Edinburgh intercalating in immunology. She is the Secretary of Edinburgh University’s BAME Medics Society.

Sonia Afonso de Barros

Sonia Afonso de Barros (she/her), MBChB, MA, MRCP, is a Acute Medicine doctor and Senior Wellbeing Tutor at the University of Edinburgh.

Grace Hodge

Grace Hodge (she/her), is a second year Education (with Psychology) student at the University of Cambridge.

Zac Finch

Zac Finch (he/him), BSc (Hons), is a fifth year medical student at the University of Edinburgh and is Secretary of the University’s Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT+) Medics’ Society.

Riya Elizabeth George

Riya Elizabeth George (she/her), PhD, SFHEA, is a Associate Professor/Reader in Clinical Communication Skills & Diversity Education. Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Institute of Health Sciences Education, Queen Mary University of London.

References

- Acholonu RG, Cook TE, Roswell RO, Greene RE. 2020. Interrupting microaggressions in health care settings: a guide for teaching medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 16:10969.

- Altabbaa G, Beran T, Arlene Drefs M, Oddone Paolucci E. 2021. Twelve tips for using simulation to teach about conformity behaviors in medical education. Med Teach. 43(12):1360–1367.

- Banyard VL. 2011. Who will help prevent sexual violence: creating an ecological model of bystander intervention. Psychol Violence. 1(3):216–229.

- Bell SC, Coker AL, Clear ER. 2019. Bystander program effectiveness: a review of the evidence in educational settings (2007–2018). In: O’Donohu, WT, Schewe PA, editors. Handbook of sexual assault and sexual assault prevention. Cham: Springer; p. 433–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23645-8_26

- Boscardin CK. 2015. Reducing implicit bias through curricular interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 30(12):1726–1728.

- Brokenshire SJ. 2015. Evaluating bystander intervention training: creating awareness on college campuses. Ann Arbor: Northern Arizona University.

- Coker AL, Bush HM, Cook-Craig PG, DeGue SA, Clear ER, Brancato CJ, Fisher BS, Recktenwald EA. 2017. RCT testing bystander effectiveness to reduce violence. Am J Prev Med. 52(5):566–578.

- Dong H, Sherer R, Lio J, Jiang I, Cooper B. 2018. Twelve tips for using clinical cases to teach medical ethics. Med Teach. 40(6):633–638.

- Dutta N, Maini A, Afolabi F, Forrest D, Golding B, Salami RK, Kumar S. 2021. Promoting cultural diversity and inclusion in undergraduate primary care education. Educ Prim Care. 32(4):192–197.

- Fnais N, Soobiah C, Chen MH, Lillie E, Perrier L, Tashkhandi M, Straus SE, Mamdani M, Al-Omran M, Tricco AC. 2014. Harassment and discrimination in medical training. Acad Med. 89(5):817–827.

- Fenley M, Daele A. 2011. Increase inclusion in higher education: tips and tools for teachers. Universite de Lausanne; [accessed 2022 Sep 05]. https://www.unil.ch/cse/files/live/sites/cse/files/shared/brochures/Diversity_Toolbox_June2014.pdf.

- Fenton R, Mott H, McCartan K, Rumney P. 2015. A review of evidence for bystander intervention to prevent sexual and domestic violence in universities Commissioned by Public Health England Centre for Legal Research Working Paper No. 62. A review of evidence for bystander intervention to prevent sexual and domestic violence in universities. https://www2.uwe.ac.uk/faculties/BBS/BUS/law/Law%20docs/dvlitreviewproof0.6.forCLR.pdf.

- Fenton RA, Mott Hl McCartan K, Rumney PNS. 2016. A review of evidence for bystander intervention to prevent sexual and domestic violence in universities. London: Public Health England.

- Greggory R. 2008. Expert resources and guide to LGBT inclusivity in the classroom; [accessed 2022 Sep 05]. https://onlinempadegree.usfca.edu/expert-guide-to-classroom-lgbt-inclusivity/.

- Holtzman M. 2021. Bystander intervention training: does it increase perceptions of blame for non‐intervention? Sociol Inq. 91(4):914–939.

- Krackov SK. 2011. Expanding the horizon for feedback. Med Teach. 33(11):873–874.

- Kristoffersson E, Hamberg K. 2022. “I have to do twice as well” – managing everyday racism in a Swedish Medical School. BMC Med Educ. 22(1):235.

- Lansbury L. 2014. The development, measurement and implementation of a bystander intervention strategy: a field study on workplace verbal bullying in a large UK organisation; [accessed 2022 Jul 18]. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-development%2C-measurement-and-implementation-of-Lansbury/cc150a8f2c22c10f940d6f1ad6766ac2c6dfb6d5.

- Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. 2009. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 14(4):595–621.

- Meyer C, Zelin AI. 2019. Bystander as a band-aid: how organization leaders as active bystanders can influence culture change. Ind Organ Psychol. 12(3):342–344.

- Mujal GN, Taylor ME, Fry JL, Gochez-Kerr TH, Weaver NL. 2021. A systematic review of bystander interventions for the prevention of sexual violence. Trauma Violence Abuse. 22(2):381–396.

- Pfetsch J, Steffgen G, Gollwitzer M, Ittel A. 2011. Prevention of aggression in schools through a bystander intervention training. Int J Dev Sci. 5(1–2):139–149.

- Pollock P, Hamann K, Wilson B. 2011. Learning through discussions: comparing the benefits of small-group and large-class settings. J Polit Sci Educ. 7(1):48–64.

- Powers RA, Leili J. 2018. Bar training for active bystanders: evaluation of a community-based bystander intervention program. Violence Against Women. 24(13):1614–1634.

- Relyea MR, Portnoy GA, Klap R, Yano EM, Fodor A, Keith JA, Driver JA, Brandt CA, Haskell SG, Adams L. 2020. Evaluating bystander intervention training to address patient harassment at the veterans health administration. Womens Health Issues. 30(5):320–329.

- Sandars J. 2009. The use of reflection in medical education. Med Teach. 31(8):685–695.

- Sandoval RS, Afolabi T, Said J, Dunleavy S, Chatterjee A, Ölveczky D. 2020. Building a tool kit for medical and dental students: addressing microaggressions and discrimination on the wards. MedEdPORTAL. 16:10893.

- Schenning KJ, Tseng J. 2013. Toward a humanistic learning environment: addressing resident mistreatment. J Grad Med Educ. 5(2):344.

- Scully M, Rowe M. 2009. Bystander training within organizations. J Int Ombudsman Assoc. 2(1):1.

- Smith W. 2004. Black faculty coping with racial battle fatigue: the campus racial climate in a post-civil rights era. In: Cleveland D, editor. A long way to go: conversations about race by African American faculty and graduate students. New York: Peter Lang; p. 171–190.

- Sotto-Santiago S, Mac J, Duncan F, Smith J. 2020. “I Didn’t Know What to Say”: responding to racism, discrimination, and microaggressions with the OWTFD approach. MedEdPORTAL. 16(1):10971.

- Sundstrom B, Ferrara M, DeMaria AL, Gabel C, Booth K, Cabot J. 2018. It’s your place: development and evaluation of an evidence-based bystander intervention campaign. Health Commun. 33(9):1141–1150.

- The Behavioural Insights Team. 2020. Unconscious bias and diversity training – what the evidence says. England: Civil Service HR.

- Todd AR, Bodenhausen GV, Galinsky AD. 2012. Perspective taking combats the denial of intergroup discrimination. J Exp Soc Psychol. 48(3):738–745.

- Universities UK. 2020. Tackling racial harassment in higher education. London: Universities UK.

- Vukotich G. 2013. Military sexual assault prevention and response: the bystander intervention training approach. J Organ Cult Commun Confl. 17(1):19–34.

- Whitgob EE, Blankenburg RL, Bogetz AL. 2016. The discriminatory patient and family: strategies to address discrimination towards trainees. Acad Med. 91(11):S64–S69.

- Wilkins KM, Goldenberg MN, Cyrus KD. 2019. ERASE-ing patient mistreatment of trainees: faculty workshop. MedEdPORTAL. 15(1):10865.