Abstract

Purpose

Self-regulated learning (SRL) can enhance students’ learning process. Students need support to effectively regulate their learning. However, the effect of learning climate on SRL behavior, its ultimate effect on learning and the underlying mechanisms have not yet been established. We explored these relationships using self-determination theory.

Materials and methods

Nursing students (N = 244) filled in questionnaires about SRL behavior, perceived learning, perceived pedagogical atmosphere and Basic Psychological Needs (BPN) satisfaction after their clinical placement. Structural equation modelling was used to test a model in which perceived pedagogical atmosphere affects SRL behavior and subsequent perceived learning through BPN satisfaction.

Results

The tested model had an adequate fit (RMSEA = 0.080, SRMR = 0.051; CFI = 0.972; TLI = 0.950). A positively perceived pedagogical atmosphere contributed to SRL behavior, which was fully explained by BPN satisfaction. SRL partially mediated the contribution of pedagogical atmosphere/BPN to perceived learning.

Conclusions

A learning climate that satisfies students’ BPN contributes to their SRL behavior. SRL behavior plays a positive but modest role in the relationship between climate and perceived learning. Without a culture that is supportive of learning, implementation of tools to apply SRL behavior may not be effective. Study limitations include reliance on self-report scales and the inclusion of a single discipline.

1. Introduction

In health professions education (HPE), self-regulated learning (SRL) has been increasingly acknowledged as a means to create learning opportunities while delivering patient care (van Houten-Schat et al. Citation2018). Taking control of one’s learning can also be burdensome, when this is not adequately supported by the environment (Watling et al. Citation2021). Previous studies suggest that when students feel they are of little added value to the team, they may feel less motivated to self-regulate their learning (Brydges and Butler Citation2012; Berkhout et al. Citation2017; Bransen et al. Citation2022). However, the effect of the quality of the learning climate on whether students engage in SRL behavior has not been established quantitatively. Moreover, little is known about whether SRL behavior indeed leads to more learning. The present study aimed to investigate these relationships in the context of clinical nursing education from a self-determination theory perspective (Ryan and Deci Citation2000). Understanding these relationships can create the conditions for successful clinical learning.

Practice points

Basic psychological needs satisfaction is an important mechanism underlying the relationship between a positive clinical learning climate and self-regulated learning behavior.

Self-regulated learning behavior plays a modest role in the relationship between clinical learning climate and perceived learning outcomes.

Clinical staff can promote students’ current and future learning behavior through offering a sense of competence, relatedness and autonomy.

SRL is a process of seeking to accomplish goals through the self-directed use and modification of strategies, such as time-management, self-evaluation, and help-seeking behavior. SRL is a dynamic and cyclical process, in which the sub-processes forethought, performance and self-reflection can be distinguished (Zimmerman Citation2013). Learners apply different SRL strategies across contexts and tasks (Rovers et al. Citation2019). SRL is essential for life-long learning (Berkhout et al. Citation2018) and is associated with academic performance (Sitzmann and Ely Citation2011). Recent studies suggest that in informal (workplace) settings the same SRL phases can be distinguished as in academic settings (Cuyvers et al. Citation2020). The same studies report that specific learning strategies as well as the order and interrelatedness of the phases of SRL may be different.

In clinical healthcare education, the relevance of SRL for creating and utilizing learning opportunities has been increasingly acknowledged (van Houten-Schat et al. Citation2018). Indeed, SRL is associated with positive outcomes such as clinical competence, skills performance as well as lifelong learning in medical and nursing education (Berkhout et al. Citation2018; van Houten-Schat et al. Citation2018; Chen et al. Citation2020). However, many studies fail to report the (desired) outcomes of SRL behavior, leaving questions about its added value in the clinical context unanswered (van der Gulden et al. Citation2022).

Research in academic settings suggests a reciprocal relationship between SRL and the learning environment. SRL can enable students to deal with stressful situations and reduce their vulnerability in the academic setting (Van Nguyen et al. Citation2015). At the same time, a positive environment, in which students experience a sense of belonging, is essential for SRL behavior (Won et al. Citation2018). In medicine, the application of SRL in the clinical context is affected by environmental factors, such as help from supervisors or peers, feedback, and goal orientation (Berkhout et al. Citation2015; Brydges et al. Citation2020). A previous quantitative study about the relationship between clinical environment and self-regulated learning in nursing used an incomplete perspective on SRL (Chen et al. Citation2020), and another quantitative study in medicine did not measure learning climate (Artino et al. Citation2012). More insight into the nature of this relationship as well as underlying factors may contribute to our design of the clinical learning environment.

A theoretical framework that has contributed to our understanding of how the environment contributes to learning behavior and actual learning is Self-determination Theory (SDT) (Ryan and Deci Citation2000). According to SDT, human beings have three innate basic psychological needs (BPN) which have to be fulfilled for autonomous self-regulation and well-being: autonomy (feeling choice in the when, what and how of learning) competence (feeling able to effectively accomplish tasks), and relatedness (feeling connected with others). In academic settings, BPN satisfaction can be a linking pin between environment and (self-regulated) learning: Environments that contribute to the fulfillment of these needs help students to fully immerse in learning, engage in SRL, pursue their own goals, and apply adequate learning strategies (Reeve et al. Citation2008; Babenko and Oswald Citation2019). In the clinical setting, an association between autonomy support and SRL (Berkhout et al. Citation2015), and between the fulfillment of the need for competence and SRL have been reported (Mukhtar et al. Citation2018). The role that needs satisfaction plays in the relationship between learning climate and self-regulated learning behavior has not been established in clinical HPE.

This study aimed to investigate whether a safer learning climate leads to more SRL behavior, and whether students’ fulfillment of BPN plays a role in this relationship. Next, to assess whether SRL behavior indeed enhances learning, we aimed to investigate the role of SRL in the relationship between a safe learning climate and students’ perceived learning. Although both SRL behavior and BPN Satisfaction consist of sub-processes that may contribute differently to the relationships we aimed to study, we focused on the relationships between the core variables in this study, which can be unraveled in more detail in further studies.

We choose nursing education as a study context. In Europe, nursing students spend around 50% of their four year program in various clinical placements, in which they work towards independent patient care (Lahtinen et al. Citation2014). An environment that creates a sense of belonging helps nursing students to learn within their temporal, subordinate position on the ward (Stoffels et al. Citation2022). Although the relevance of SRL in nursing education is widely acknowledged (Irvine et al. Citation2021), the role SRL plays in clinical nursing education is under-investigated in the literature (Stoffels et al. Citation2019).

Based on the literature, the hypotheses for this study were as follows:

Hypothesis 1

– A positive pedagogical atmosphere in the clinical setting contributes to more self-regulated learning behavior (i.e. forethought, performance and self-reflection) mediated through the fulfilment of basic psychological needs.

Hypothesis 2

– A positive pedagogical atmosphere in the clinical setting contributes to perceived learning, mediated through more self-regulated learning behavior (i.e. forethought, performance and self-reflection).

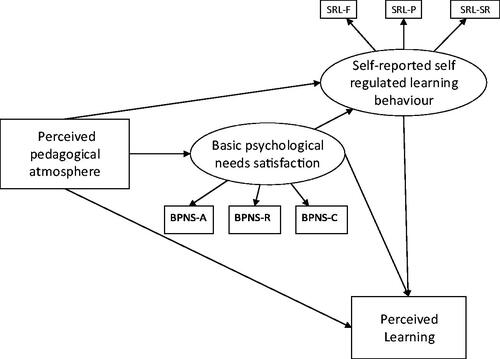

See for a graphical representation of the hypothesized model.

Figure 1. Hypothesized relationships between pedagogical atmosphere, basic psychological needs satisfaction, self-reported self-regulated learning behavior and perceived learning. Self-reported self-regulated learning behavior and basic psychological needs satisfaction are measured by their sub-processes. SRL-F: SRL forethought; SRL-P: SRL performance; SRL-SR: SRL self-reflection; BPNS-a: BPN autonomy satisfaction; BPNS-R: BPN relatedness satisfaction; BPNS-C: BPN competence satisfaction.

2. Methods

2.1. Setting

We conducted this study in a University of Applied Sciences (UAS) offering nursing education in the Netherlands, with different allied practice partners offering clinical placements (such as hospital, nursing home, mental health care clinic).

Students are supported by the UAS to structure their own learning process in the clinical setting. Before each clinical placement, students get instructions from the UAS about to write a plan with learning goals and activities for this placement. The UAS offers tools such as feedback and reflection forms. The extent to which students are indeed allowed to actively take control of their learning varies across settings (Flott and Linden Citation2016).

2.2. Participants and data collection

We collected cross-sectional data from second to fourth year undergraduate nursing students between February and July 2020. We recruited a convenience sample of all 690 students that finished a clinical placement in the spring of 2020 through email and the electronic learning environment to fill out an online survey about their clinical placement. First-year students were excluded because their clinical placements are too short and elementary to allow for true SRL. The Ethical Review Board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education approved this study (refile no. 2019.8.4).

2.3. Variables and instruments

The original instruments were translated and modified to fit the Dutch nursing context using the adaptation guidelines for questionnaires (Beaton et al. Citation2000). The survey was piloted with three nurse educators and three nursing students. Feedback was incorporated by the main researcher to finalize the survey. All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale. See Supplementary file 1 for the survey items.

2.3.1. Perceived learning

Grasping the full complexity of clinical learning into objective, quantifiable outcomes is challenging (Morris Citation2018). Recently, EPA- or milestone based assessments have been introduced to better capture the actual clinical learning process. However, objectively assessing these processes requires multiple informants (Schumacher et al. Citation2022). Learning is individual, context-dependent, and spans more than clinical competence. Moreover, not only current competence, but also the ability to respond to future situations are important in HPE (Kua et al. Citation2021). Therefore, we chose students’ perception of how the clinical placement contributed to their development on different aspects of the nursing profession as an indicator of learning (Löfmark et al. Citation2012). The overall learning outcomes scale was originally developed as a subscale to the self-report Nursing Clinical Facilitators Questionnaire (NCFQ) (Kristofferzon et al. Citation2013). The scale consists of 8 items on a single dimension and covers the intended outcomes of learning in clinical practice (independence, responsibility, confidence, ethical awareness, critical thinking, use of nursing research in patient care, systematic way of working, planning and decision-making according to patient needs) and can be used for different levels of nursing education. The subscale has been used separately from the original questionnaire as an outcome of peer learning interventions and preceptorship programs and measurement with this subscale has showed high internal consistency in earlier studies (Löfmark et al. Citation2012; Kristofferzon et al. Citation2013; Palsson et al. Citation2017; Rambod et al. Citation2018).

2.3.2. Pedagogical atmosphere

As an indicator of learning climate, the pedagogical atmosphere subscale of the clinical learning environment, supervision and nurse teacher scale (CLES + T) was used (Saarikoski et al. Citation2008). The subscale measures the ward climate (in addition to a separate subscale about the supervisory relationship) and consists of 8 items that include atmosphere, approachability of staff, staff’s interest in supervision, as well as availability of learning opportunities. The content validity, structural validity and internal consistency of the measurement of the learning environment quality using the Cles + T have been reported to be adequate in several contexts (Mansutti et al. Citation2017). One item of the original questionnaire was erroneously not included in all online questionnaires and could therefore not be included in the analysis (Supplementary File 1).

2.3.3. SRL behavior

As most SRL questionnaires target learning in the academic context (e.g. reading, classroom preparation), we used The Self-regulated Learning at Work Questionnaire (SRLWQ) to measure SRL behavior in the workplace (Fontana et al. Citation2015). This questionnaire is developed based on the work of Zimmerman and on questionnaires that measure SRL in the academic setting. It was used before to address learning in the clinical context (Bransen et al. Citation2022). The questionnaire consist of three subscales reflecting the phases of SRL: forethought (17 items), performance (19 items) and self-reflection (6 items). As learning may be context-dependent, the questionnaire targets actual (or past) behavior instead of SRL ability. Measurement with this scale as well as the subscales have shown high reliability and the factor structure was replicated (Fontana et al. Citation2015; Lourenco and Ferreira Citation2019). Based on feedback and discussion in the pilot phase, eleven items which were perceived as ambiguous were omitted (Supplementary File 1).

2.3.4. Basic psychological needs satisfaction

To measure basic psychological needs satisfaction (BPN), the BPN needs satisfaction and frustration scale work domain was used, which has previously been used in studies about clinical learning (Mukhtar et al. Citation2018). Need satisfaction and need frustration are separate constructs, with distinct antecedents as well as outcomes (Vansteenkiste et al. Citation2020). Given the widespread use of the satisfaction component in previous research, only this scale was used. This scale consists of 12 items, on the subscales autonomy, relatedness, and competence. The scale as well as the subscales have shown acceptable reliability and the factor structure was replicated in validation studies (Olafsen et al. Citation2021). A previous Dutch translation of the questionnaire showed acceptable reliability (van der Burgt et al. Citation2019).

2.4. Analysis

We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to study structural relationships between latent variables, correcting for measurement error within observed variables (Violato and Hecker Citation2007).

For the descriptive statistics and primary analyses we used SPSS Version 28.0.1. After checking for normal distribution of the data and missing data, Pearson’s correlations were computed to explore relationships between variables. The reliability of the measurements was tested by calculating their Cronbach’s alphas. As SRL behavior may change with study year (Bransen et al. Citation2022) differences between different study years on all variables were analyzed using ANOVA. Gender differences were not analyzed because of the low representation of male students in nursing education.

Next, the hypothesized model was tested with Structural Equation Model using R version 3.6.1 Lavaan package (Rosseel Citation2012). Including all items of lengthy scales in a SEM model with relatively small sample sizes reduces statistical power to detect relationships between variables. To obtain more stable parameter estimates and better model fit, item parceling was used by averaging item scores into scale or subscale scores (Bandalos and Finney Citation2001). This resulted in two variables (SRL behavior and BPN Satisfaction) that were included in the SEM model as latent variables with their subscales as indicators, and two variables (Perceived pedagogical atmosphere and Perceived learning) that were included in the model as observed variables. The sample size was too small to establish measurement invariance across study years, so the model was tested only for the entire sample.

The SEM fit criteria used were: Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) and comparative fit index (CFI) ≧0.90; Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) scores ≦0.08 as indicators of an adequate fit, and TLI and CFI > 0.95, RMSEA < 0.06, SRMR < 0.08 as evidence of a good fit (Hu and Bentler Citation1999). The direct and indirect effects of the latent variables were examined concurrently. Fit parameters were estimated with the help of robust maximum likelihood (MLM) estimation with standard errors and tests of fit that were robust to non-normality of observations.

3. Results

Two hundred and forty four nursing students completed the questionnaires, resulting in a response rate of 35%. See for demographic characteristics of the study sample. Results indicate that clinical placement setting is not equally distributed over study years.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the study sample.

Our sample is comparable to the total population of students finishing a clinical placement in the relevant time period in terms of gender and clinical placement type. However, 3rd year students are relatively overrepresented in our sample.

3.1. Descriptive statistics and primary analyses

Percentage of missing data was 0.3% (54 items). Missing data was missing complete at random (MCAR) as indicated by the results of Little’s MCAR test (p = 0.142) (Little Citation1988). Therefore, no imputation was made for missing data. Data were not normally distributed. However, when using estimators robust to non-normality in SEM, reliable fit indices can still be obtained (Kline Citation2015).

Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.653 (BPN-CS) to .889 (BPN-RS). The correlational analysis showed that all correlations were statistically significant at p = 0.05 with exception of the correlation between SRL-reflection and Perceived pedagogical atmosphere. See Supplementary File 2 for the Pearson’s correlations between different study variables as well as the reliability of each variable.

The ANOVA revealed that all variables showed a significant overall increase across study years. See Supplementary file 3 for descriptive statistics of study variables and ANOVA results of differences between study years.

3.2. Structural equation model

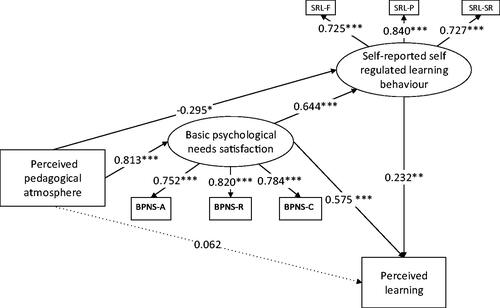

presents the structural relationships of the final model with standardized estimates among the path relationships and factor loadings. The model showed adequate fit (RMSEA =0.080 (0.047–0.0114), SRMR= 0.051; CFI = 0.972; TLI = 0.950. See Supplementary 4 for the regression coefficients and factor loadings of the fitted model.

Figure 2. Structural relationships between pedagogical atmosphere, basic psychological needs satisfaction, self-reported self-regulated learning behavior and perceived clinical learning of the final model with standardized estimates among the path relationships and factor loadings (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, dotted line = non-significant).

In line with our first hypothesis, there was a significant indirect positive contribution of Perceived pedagogical atmosphere on SRL behavior, via BPN satisfaction (β = 0.523, p < 0.001). The direct contribution of pedagogical atmosphere on SRL behavior again showed a slight negative, but marginally significant effect (β = −0.295, p = 0.034).

To understand the negative direct contribution of pedagogical atmosphere on SRL behavior and positive indirect contribution on SRL behavior via BPN satisfaction, we examined bivariate correlations between variables. The positive bivariate correlation between Perceived pedagogical atmosphere and Perceived learning as well as the high positive correlation between BPN satisfaction and Perceived pedagogical atmosphere suggest that the negative direct contribution of Perceived pedagogical atmosphere on SRL behavior in the SEM model is an artefact of the fitted model. The presence of BPN satisfaction in the models appears to suppress the direct positive contribution of pedagogical atmosphere on SRL behavior and Perceived learning.

Contrary to our second hypothesis, the indirect contribution of Perceived pedagogical atmosphere on Perceived learning via SRL behavior was slightly negative (β= −0.069, p = 0.039). Perceived pedagogical atmosphere did not contribute directly to Perceived learning (β = 0.062, p=.684). Given the significant role of BPN satisfaction in the relationship between Perceived pedagogical atmosphere and SRL behavior, we tested our second hypotheses again, but this time including BPN satisfaction. We did find that a positive Perceived pedagogical atmosphere contributed to Perceived learning indirectly via BPN satisfaction and SRL behavior subsequently (β = 0.121, p = 0.004). This supports our hypotheses about the mediating role of SRL in the relationship between pedagogical atmosphere and perceived learning. However, the significant contribution of Perceived pedagogical atmosphere via BPN satisfaction on Perceived learning without SRL behavior as a mediator (β = 0.467, p < 0.000) indicates that SRL only partially mediates the (indirect) effect of Perceived pedagogical atmosphere on Perceived learning.

4. Discussion

We found that in the context of clinical nursing placements, a safe learning climate contributes to exhibited SRL behavior and higher perceived learning which is fully mediated by the satisfaction of BPN. SRL behavior partly explains the effect of pedagogical atmosphere (via BPN satisfaction) on perceived learning. These findings add to the broader HPE literature by providing quantitative support for the notion that a supportive clinical learning environment can lead to more SRL behavior, which in turn leads to more perceived learning. By exploring the mediating roles of SRL and BPN satisfaction between environment and learning, we build on separate bodies of literature describing these individual relationships.

Our hypothesis that BPN can be considered a linking pin between positive learning climate and SRL behavior was supported. The strong contribution of BPN satisfaction adds to the HPE literature by suggesting psychological mechanisms through which the environment affects SRL. That is, not only is the quality of students’ SRL behavior affected by the support they receive, they may not feel safe or intrinsically motivated to initiate this behavior without a certain level of needs satisfaction (Neufeld and Malin Citation2019; Kusurkar Citation2023). This builds on previous work exemplifying (meta)cognitive mechanisms (support to understand how to apply SRL) (Brydges et al. Citation2020) and social mechanisms (collaboration around SRL) (Bransen et al. Citation2022) that underlie the effect of environment on SRL behavior. These findings underscore how the organization of the ward and the attitude and the behavior of those involved in clinical learning affect students’ learning behavior, not only through direct supervision, but possibly also more subtly through their attitude towards students and learning (Orsini et al. Citation2018).

The positive contribution of SRL to perceived learning is in line with previous work in HPE about the relationship between SRL and skills or competence development (Cho et al. Citation2017). The partial support for the hypothesis that SRL was the mediating factor in the relation between the environment and perceived learning is in line with previous work in the nursing context showing that SRL only partly mediates the relationship between learning environment and actual learning, whereas it fully mediates the relation between teaching competence and students’ competence (Chen et al. Citation2020). One explanation for the modest explanatory power of SRL behavior is that individual differences in SRL outweigh the effect the environment has on SRL (Berkhout et al. Citation2015). Another explanation lies in the fact that clinical learning happens in a complex environment in which outcomes are hard to control or predict (Clarke Citation2005). The large and direct contribution of BPN satisfaction on perceived earning suggests that SRL might be only one way to bring about positive learning outcomes. Future work using measures that are sensitive to event-related SRL behavior should explore when and how SRL behavior can add to other factors that affect clinical learning, and whether it can compensate for the negative effects of unfavorable learning environments. Presumably, SRL behavior also results in future positive learning, as developing SRL strategies can prepare students for lifelong learning (Mylopoulos et al. Citation2016; Berkhout et al. Citation2018). Longitudinal studies are required to examine the effect of SRL behavior in the clinical setting on learning and performance throughout the career in different disciplines.

Previous studies in the context of nursing education suggest that students feel that self-regulated learning, may evoke a more passive attitude of supervisors (Stoffels et al. Citation2021). The HPE literature has offered recommendations about how supervisors can help students with formulating learning goals or seeking feedback for effective SRL (Bransen et al. Citation2022). The current findings point towards the more fundamental requirements for learning that the ward should offer to allow for SRL. Clinical settings should critically discuss in which stage of a placement SRL behavior can be expected and how these preconditions can be monitored. All ward staff should be involved in establishing a culture that supports active learning behavior, to make sure students feel they are well allowed to do so (Watling et al. Citation2021). Individual supervisors as well as ward management should repeatedly discuss with students whether they feel they have the right level of choice (autonomy), whether they feel confident enough to actively structure their learning, and whether their relationships are safe enough to experiment with self-regulated learning behavior (relatedness). Addressing these needs will foster students’ intrinsic motivation to invest in active learning behavior, which will ultimately affect the quality of the learning behavior as well (Orsini et al. Citation2015). Future work is needed to explore the quality of different SRL behaviors within clinical practice periods and the preparation and guidance these require. To provide more directed recommendations for practice, the effects of the three different psychological needs on sub-processes of SRL behavior should be examined separately, in different types of disciplines and placement organizations.

This study has several limitations. We looked for general patterns within a group with wide variety (e.g. study year, placement type) thus limiting the interpretation of findings and formulation of targeted implications. However, the significant effects we found in spite of the diversity in study year and setting, will contribute to this emerging field. Undergraduate nursing education may place different demands on students in the clinical setting compared to (post graduate) medical education, in terms of independent patient care, (meta) cognition, and professional behavior (Liljedahl et al. Citation2015). For example, the relevance of a safe learning climate and sense of belonging may be more pronounced in nursing care. On the other hand, the relatively long practice periods allow students to gain independence in working and learning. Future studies should address how the relationships found are affected by characteristics of programs and disciplines. Using cross-sectional data, causal inferences could not be made on the basis of statistical significance alone. However, using a well-founded theoretical basis legitimized the relationships within our model (Kline Citation2015). We relied on self-report measures which are subject to response biases, which may have inflated correlations between different variables. This deserves further validation in the nursing context. Questionnaires to measure SRL in the clinical setting are at their infancy and generally are unable to capture qualitative individual or task-related differences. However, using self-report for SRL is common in this type of research and has proven to give a relatively accurate insight into students’ global self-regulation (Rovers et al. Citation2019). With respect to perceived learning, instruments that objectively measure individual growth across all domains of workplace learning are lacking (Clarke Citation2005). The literature reports mixed findings about students’ accuracy in self-assessing their competence (Gabbard and Romanelli Citation2021). However, to acknowledge the complex dynamic of workplace learning, a self-report instrument to capture a broad set of learning outcomes that can be achieved in different study years and contexts best matched our study objectives. The associations found can be further understood and validated through measures such as competency assessments and behavioral observations. Previous work as well as the correlational analysis suggested that sub-processes of SRL and BPN as well as study year may have their unique contribution to the found associations. However, correlations between subscales of each scale would have hampered the interpretation of subscale scores within a single model (Mukhtar et al. Citation2018).

5. Conclusions

Students’ SRL behavior in clinical nursing education is affected by a safe learning climate on the clinical ward, which is fully mediated by the satisfaction of BPN. The effect of the perceived environment on perceived learning is partly mediated by SRL behavior. Ward staff and management play an important role in creating and monitoring the preconditions for students’ SRL: they should make students feel they have choices, given them confidence, and make them feel included in the team. Without a supportive culture, implementation of tools and training to apply SRL behavior may not be effective. Even if SRL behavior does not directly result in better outcomes, supporting students in this process might increase their motivation for learning in the short as well as long term.

Author contributions

MS, ABHB, SMEB, HED, SMP, and RAK contributed to the research idea and study design and participated in group discussions in the analysis phase. MS conducted data collection and wrote the manuscript. MS, ASK and SMEB conducted statistical analyses. All authors edited and revised the paper. RAK led the supervision of the project.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (49.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Michiel Luijten, MSc, Amsterdam UMC Section Pediatric Psychology Research for his statistical advice. We would like to thank Anne Ausema, MSc, Hogeschool van Amsterdam Department of Nursing Education for her assistance in data collection. We would like to thank everyone involved in piloting the interviews as well as all study participants.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [MS], upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Malou Stoffels

Malou Stoffels, MSc, is trained in psychology and education and works as an educational consultant and PhD student in clinical nursing education.

Andries S. Koster

Andries S. Koster, PhD, is trained as a pharmacologist and has been working as a researcher and teacher in Pharmacological Sciences until his retirement.

Stephanie M. E. van der Burgt

Stephanie M. E. van der Burgt, PhD, is trained in sociology and works as a researcher in postgraduate medical education.

Anique B. H. de Bruin

Anique B. H. de Bruin, PhD, is trained as a psychologist and works as a professor on Self-regulated learning in Higher education.

Hester E. M. Daelmans

Hester E. M. Daelmans, MD, PhD, is trained in medicine and works as a head of the master’s program in medicine.

Saskia M. Peerdeman

Saskia M. Peerdeman, MD, PhD, works as a neurosurgeon, professor in education and vice dean.

Rashmi A. Kusurkar

Rashmi A. Kusurkar, MD, PhD, is trained as a medical doctor and works as a professor in medical education.

References

- Artino AR, Jr., Dong T, DeZee KJ, Gilliland WR, Waechter DM, Cruess D, Durning SJ. 2012. Achievement goal structures and self-regulated learning: relationships and changes in medical school. Acad Med. 87(10):1375–1381. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182676b55.

- Babenko O, Oswald A. 2019. The roles of basic psychological needs, self-compassion, and self-efficacy in the development of mastery goals among medical students. Med Teach. 41(4):478–481. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1442564.

- Bandalos DL, Finney SJ. 2001. Item parceling issues in structural equation modeling. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. New developments and techniques in structural equation modeling. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; p. 269–296.

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. 2000. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 25(24):3186–3191. doi:10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014.

- Berkhout J, Helmich E, Teunissen P, van der Vleuten C, Jaarsma A. 2017. How clinical medical students perceive others to influence their self-regulated learning. Med Educ. 51(3):269–279. doi:10.1111/medu.13131.

- Berkhout J, Helmich E, Teunissen P, van der Vleuten C, Jaarsma A. 2018. Context matters when striving to promote active and lifelong learning in medical education. Med Educ. 52(1):34–44. doi:10.1111/medu.13463.

- Berkhout J, Helmich E, Teunissen PW, van den Berg JW, van der Vleuten CP, Jaarsma AD. 2015. Exploring the factors influencing clinical students’ self-regulated learning. Med Educ. 49(6):589–600. doi:10.1111/medu.12671.

- Bransen D, Govaerts MJB, Panadero E, Sluijsmans DMA, Driessen EW. 2022. Putting self-regulated learning in context: integrating self-, co-, and socially shared regulation of learning. Med Educ. 56(1):29–36. doi:10.1111/medu.14566.

- Bransen D, Govaerts MJB, Sluijsmans DMA, Donkers J, Van den Bossche PGC, Driessen EW. 2022. Relationships between medical students’ co-regulatory network characteristics and self-regulated learning: a social network study. Perspect Med Educ. 11(1):28–35. doi:10.1007/s40037-021-00664-x.

- Brydges R, Butler D. 2012. A reflective analysis of medical education research on self-regulation in learning and practice. Med Educ. 46(1):71–79. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04100.x.

- Brydges R, Tran J, Goffi A, Lee C, Miller D, Mylopoulos M. 2020. Resident learning trajectories in the workplace: a self-regulated learning analysis. Med Educ. 54(12):1120–1128. doi:10.1111/medu.14288.

- Chen S-L, Sun J-L, Jao J-Y. 2020. A predictive model of student nursing competency in clinical practicum: a structural equation modelling approach. Nurse Educ Today. 95:104579. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104579.

- Cho KK, Marjadi B, Langendyk V, Hu W. 2017. The self-regulated learning of medical students in the clinical environment–a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 17(1):112. doi:10.1186/s12909-017-0956-6.

- Clarke N. 2005. Workplace learning environment and its relationship with learning outcomes in healthcare organizations. Human Resour Develop Int. 8(2):185–205. doi:10.1080/13678860500100228.

- Cuyvers K, Van den Bossche P, Donche V. 2020. Self-regulation of professional learning in the workplace: a state of the art and future perspectives. Vocat Learn. 13(2):281–312. doi:10.1007/s12186-019-09236-x.

- Flott EA, Linden L. 2016. The clinical learning environment in nursing education: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 72(3):501–513. doi:10.1111/jan.12861.

- Fontana RP, Milligan C, Littlejohn A, Margaryan A. 2015. Measuring self-regulated learning in the workplace. Int J Train Develop. 19(1):32–52. doi:10.1111/ijtd.12046.

- Gabbard T, Romanelli F. 2021. The accuracy of health professions students’ self-assessments compared to objective measures of competence. Am J Pharm Educ. 85(4):8405. doi:10.5688/ajpe8405.

- Hu L, Bentler PM. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equat Model. 6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Irvine S, Williams B, Smallridge A, Solomonides I, Gong YH, Andrew S. 2021. The self-regulated learner, entry characteristics and academic performance of undergraduate nursing students transitioning to University. Nurse Educ Today. 105:105041. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105041.

- Kline RB. 2015. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Kristofferzon M-L, Mårtensson G, Mamhidir A-G, Löfmark A. 2013. Nursing students’ perceptions of clinical supervision: the contributions of preceptors, head preceptors and clinical lecturers. Nurse Educ Today. 33(10):1252–1257. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2012.08.017.

- Kua J, Lim WS, Teo W, Edwards RA. 2021. A scoping review of adaptive expertise in education. Med Teach. 43(3):347–355. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1851020.

- Kusurkar RA. 2023. Self-determination theory in health professions education research and practice. In: Ryan RM, editor. The Oxford handbook of self-determination theory. New York: Oxford University Press; p. 665–683.

- Lahtinen P, Leino-Kilpi H, Salminen L. 2014. Nursing education in the European higher education area - variations in implementation. Nurse Educ Today. 34(6):1040–1047. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2013.09.011.

- Liljedahl M, Boman LE, Falt CP, Bolander Laksov K. 2015. What students really learn: contrasting medical and nursing students’ experiences of the clinical learning environment. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 20(3):765–779. doi:10.1007/s10459-014-9564-y.

- Little RJ. 1988. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc. 83(404):1198–1202. doi:10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722.

- Löfmark A, Thorkildsen K, Råholm M-B, Natvig GK. 2012. Nursing students’ satisfaction with supervision from preceptors and teachers during clinical practice. Nurse Educ Pract. 12(3):164–169. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2011.12.005.

- Lourenco D, Ferreira AI. 2019. Self-regulated learning and training effectiveness. International Journal of Training and Development. 23(2):117–134. doi:10.1111/ijtd.12149.

- Mansutti I, Saiani L, Grassetti L, Palese A. 2017. Instruments evaluating the quality of the clinical learning environment in nursing education: a systematic review of psychometric properties. Int J Nurs Stud. 68:60–72. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.001.

- Morris C. 2018. Work‐based learning. Understanding medical education: evidence, theory, and practice. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley-Blackwell; p. 163–177.

- Mukhtar F, Muis K, Elizov M. 2018. Relations between psychological needs satisfaction, motivation, and self-regulated learning strategies in medical residents: a cross-sectional study. MedEdPublish. 7:87. doi:10.15694/mep.2018.0000087.1.

- Mylopoulos M, Brydges R, Woods NN, Manzone J, Schwartz DL. 2016. Preparation for future learning: a missing competency in health professions education? Med Educ. 50(1):115–123. doi:10.1111/medu.12893.

- Neufeld A, Malin G. 2019. Exploring the relationship between medical student basic psychological need satisfaction, resilience, and well-being: a quantitative study. BMC Med Educ. 19(1):405. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1847-9.

- Olafsen AH, Halvari H, Frølund CW. 2021. The basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration at work scale: a validation study. Front Psychol. 12:697306. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.697306.

- Orsini C, Binnie V, Wilson S, Villegas M. 2018. Learning climate and feedback as predictors of dental students’ self‐determined motivation: the mediating role of basic psychological needs satisfaction. Eur J Dent Educ. 22(2):e228–e236. doi:10.1111/eje.12277.

- Orsini C, Evans P, Jerez O. 2015. How to encourage intrinsic motivation in the clinical teaching environment?: a systematic review from the self-determination theory. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 12:8–8. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2015.12.8.

- Palsson Y, Martensson G, Swenne CL, Adel E, Engstrom M. 2017. A peer learning intervention for nursing students in clinical practice education: a quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today. 51:81–87. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2017.01.011.

- Rambod M, Sharif F, Khademian Z. 2018. The impact of the preceptorship program on self-efficacy and learning outcomes in nursing students. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 23(6):444–449. doi:10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_67_17.

- Reeve J, Ryan R, Deci EL, Jang H. 2008. Understanding and promoting autonomous self-regulation: a self-determination theory perspective. In: Schunk DH, Zimmerman BJ, editors. Motivation and self-regulated learning: theory, research and applications. New York (NY): Lawrence Erlbaum; p. 223–244..

- Rosseel Y. 2012. lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Statisit Software. 48:1–36.

- Rovers SF, Clarebout G, Savelberg HH, de Bruin AB, van Merriënboer JJ. 2019. Granularity matters: comparing different ways of measuring self-regulated learning. Metacognit Learn. 14(1):1–19. doi:10.1007/s11409-019-09188-6.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. 2000. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 25(1):54–67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020.

- Saarikoski M, Isoaho H, Warne T, Leino-Kilpi H. 2008. The nurse teacher in clinical practice: developing the new sub-dimension to the clinical learning environment and supervision (CLES) scale. Int J Nurs Stud. 45(8):1233–1237. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.07.009.

- Schumacher DJ, Teunissen PW, Kinnear B, Driessen EW. 2022. Assessing trainee performance: ensuring learner control, supporting development, and maximizing assessment moments. Eur J Pediatr. 181(2):435–439. doi:10.1007/s00431-021-04182-0.

- Sitzmann T, Ely K. 2011. A meta-analysis of self-regulated learning in work-related training and educational attainment: what we know and where we need to go. Psychol Bull. 137(3):421–442. doi:10.1037/a0022777.

- Stoffels M, Peerdeman SM, Daelmans HE, Ket JC, Kusurkar RA. 2019. How do undergraduate nursing students learn in the hospital setting? A scoping review of conceptualisations, operationalisations and learning activities. BMJ Open. 9(12):e029397. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029397.

- Stoffels M, van der Burgt SM, Stenfors T, Daelmans HE, Peerdeman SM, Kusurkar RA. 2021. Conceptions of clinical learning among stakeholders involved in undergraduate nursing education: a phenomenographic study. BMC Med Educ. 21(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02939-7.

- Stoffels M, van der Burgt SME, Bronkhorst LH, Daelmans HEM, Peerdeman SM, Kusurkar RA. 2022. Learning in and across communities of practice: health professions education students’ learning from boundary crossing. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 27:1423–1441.

- van der Burgt SM, Kusurkar RA, Wilschut JA, Tsoi SLTA, Croiset G, Peerdeman SM. 2019. Medical specialists’ basic psychological needs, and motivation for work and lifelong learning: a two-step factor score path analysis. BMC Med Educ. 19(1):339. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1754-0.

- van der Gulden R, Timmerman A, Muris JWM, Thoonen BPA, Heeneman S, Scherpbier-de Haan ND. 2022. How does portfolio use affect self-regulated learning in clinical workplace learning: what works, for whom, and in what contexts? Perspect Med Educ. 11(5):1–11. doi:10.1007/S40037-022-00727-7.

- van Houten-Schat MA, Berkhout JJ, van Dijk N, Endedijk MD, Jaarsma ADC, Diemers AD. 2018. Self-regulated learning in the clinical context: a systematic review. Med Educ. 52(10):1008–1015. doi:10.1111/medu.13615.

- Van Nguyen H, Laohasiriwong W, Saengsuwan J, Thinkhamrop B, Wright P. 2015. The relationships between the use of self-regulated learning strategies and depression among medical students: an accelerated prospective cohort study. Psychol Health Med. 20(1):59–70. doi:10.1080/13548506.2014.894640.

- Vansteenkiste M, Ryan RM, Soenens B. 2020. Basic psychological need theory: advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motiv Emot. 44(1):1–31. doi:10.1007/s11031-019-09818-1.

- Violato C, Hecker KG. 2007. How to use structural equation modeling in medical education research: a brief guide. Teach Learn Med. 19(4):362–371. doi:10.1080/10401330701542685.

- Watling C, Ginsburg S, LaDonna K, Lingard L, Field E. 2021. Going against the grain: an exploration of agency in medical learning. Med Educ. 55(8):942–950. doi:10.1111/medu.14532.

- Won S, Wolters CA, Mueller SA. 2018. Sense of belonging and self-regulated learning: testing achievement goals as mediators. J Exp Educ. 86(3):402–418. doi:10.1080/00220973.2016.1277337.

- Zimmerman BJ. 2013. Theories of self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview and analysis. In: Zimmerman BJ, Schunk DH, editors. Self-regulated learning and academic achievement. London: Routledge; p. 10–45.