Abstract

Background

Play can help paediatric patients cope with hospitalisation. Education on the use of play for healthcare professionals (HCPs) is lacking, with playful interactions often occurring unsystematically without formal training. This scoping review systematically describe the frameworks, design, and evaluation methods of educational programmes for HCPs on the use of play in paediatric clinical practice.

Methods

We conducted the scoping review by searching nine databases for white literature and websites for grey literature. Two reviewers independently screened titles/abstracts and reviewed full texts. Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model was applied to report the evaluation methods of educational programmes.

Results

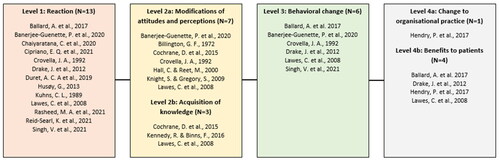

After identifying 16534 white and 955 grey items we included twenty articles but no grey literature. The educational programmes vaguely defined play for procedural and normalising purposes and mostly targeted mono-professional groups, mainly nurses. The evaluation methods identified in the articles were reported in accordance with Kirkpatrick levels 1: reaction (n = 13); 2a: attitude (n = 7); 2b: knowledge (n = 3); 3: behaviour (n = 6); 4a: organisational practice (n = 1) and 4b: patient outcomes (n = 4).

Conclusion

The few educational programmes available on the use of play for HCPs are not uniformly described. Future educational programmes would benefit from integrating the needs of HCPs, patients and parents, and using a theoretical framework and systematic evaluation.

Introduction

The use of play is important for children to cope with the stress of hospitalisation and to ensure positive development despite illness (Nijhof et al. Citation2018; Williams et al. Citation2019). Play can be used to prepare children for procedures and treatments, and some healthcare professionals (HCPs) use play as a safe and recognisable way to collaborate and communicate appropriately with children and adolescents (Haiat et al. Citation2003; Koukourikos et al. Citation2015; Godino-Iáñez et al. Citation2020).

In a recently published review we found that HCPs use play interventions in four clinical contexts: 1) to prepare or distract the patient during procedures and diagnostic tests, 2) to educate the patient on their disease, 3) to supplement treatment and rehabilitation and 4) to help the patient adapt and cope with their hospitalisation or disease (Gjærde et al. Citation2021). These play interventions frequently occur unsystematically and without formal training. Play interventions are also often carried out by extraordinarily dedicated HCPs, implying that these activities are most often restricted to specific situations or specific hours of the day, which may lead to inconsistent use and integration of play into the practice of children’s healthcare.

Few countries (e.g. Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the USA) offer postgraduate programmes to become a child life or hospital play specialist. Hospital play specialists possess a unique skill set that allows them to facilitate difficult procedures and examinations more positively. However, in Scandinavia, other European countries and most other parts of the world, child life or hospital play specialists are not professional roles within paediatric departments. Despite the World Health Organization’s (2017) recommendation that doctors and nurses working with children use play in treatment and care, it has not been consistently adopted by these programmes and professions (WHO Citation2017). As such, only few formal multi-professional postgraduate education programmes exist in using play in clinical paediatric practice (Stenman et al. Citation2019).

Educating HCPs in using play to collaborate and communicate age appropriately with hospitalised children is an emerging field (Gjærde et al. Citation2021). According to Harden (Citation1986) and Thomas et al. (Citation2016) educational interventions in medical education need to be evidence-based and developed based on an educational framework. However, no systematic mapping currently exists in educational programmes for HCPs in using play in clinical practice.

The aim of this review is to systematically identify and describe existing frameworks, design, and evaluation methods of educational programmes for HCPs on the use of play in paediatric clinical practice. The protocol for this study is registered at the Best Evidence Medical Education Collaboration and is available at Open Science Framework (Krebs et al. Citation2022).

Materials and methods

We conducted a scoping review in accordance with the updated Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual (Peters et al. Citation2020), as well as guidance (Arksey and O'Malley Citation2005; Levac et al. Citation2010). We evaluated both white and grey literature to be able to report on results in heterogeneous study designs, interventions, and evaluation methods (Tricco et al. Citation2018). A scoping review approach was chosen to identify the available evidence on educational programmes for HCPs on the use of play, describe the characteristics of educational programmes on the use of play in paediatric clinical practice, and highlight areas that would benefit from future evaluation and exploration.

We present the results of our review using a six-step approach to curriculum development (Thomas et al. Citation2016), originally designed by Kern et al. as a framework for curriculum development in medical education. This approach includes six iterative steps: 1) Problem Identification and General Needs Assessment, 2) Targeted Needs Assessment, 3) Goals and Objectives, 4) Educational Strategies, 5) Implementation, 6) Evaluation and Feedback.

Eligibility criteria

After establishing the eligibility criteria based on the population, concept and context framework () (Peters et al. Citation2020) we searched for intervention studies and case reports on educational programmes for HCPs in using play in clinical practice with no language restrictions. The search string was not limited by study design, publication data or country of origin. We also screened the reference lists of the included sources of evidence for additional studies. Studies were excluded that did not have an intervention, did not target HCPs or that took place in a psychiatric setting due to the therapeutic and diagnostic significance of play within psychiatry (Lender Citation1998; Guralnick and Hammond Citation1999).

Table 1. Eligibility criteria for inclusion of white and grey literature based on the population, concept and context framework.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We developed our search strategy iteratively in collaboration with an information specialist (AL) and based on a pilot search undertaken in PubMed (MEDLINE). An adjusted search strategy was adapted to each database on 14 May 2021 to search PubMed (MEDLINE), PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), ERIC, Scopus, PEDro, Web of Science, Embase and ProQuest for dissertation and theses worldwide. We updated the search from 4–7 April 2022. Supplementary Appendix Alists the full search string for all databases.

To aid in screening the articles all eligible references were stored in EndNote X9 and duplicates removed before being subsequently imported to the web-based software programme Covidence. Two reviewers (CLK, JH, KG, JT or ETN) independently screened titles and abstracts. CLK and JH retrieved relevant sources in full before including them.

In the event of differences, the reviewers discussed any discrepancies and then consulted LKG and/or JLS if unable to resolve them to reach consensus.

Grey literature

We included first-tier grey literature, e.g. books, book chapters, a broad range of journals, government reports and think tank publications, in addition to white literature (Adams et al. Citation2017). CLK and JH developed our search strategy based on Fuller and Lenton’s adaptation of Stapleton’s two-step Grey Literature Search Plan Template (Godin et al. Citation2015), the search terms listed in our protocol (Krebs et al. Citation2022).

Data extraction

We developed a data extraction template in Covidence based on the findings from the pilot study, the six-step approach to curriculum development (Thomas et al. Citation2016), and Barr et al.’s (Barr et al. Citation2005) modified version of Kirkpatrick’s goal-based training evaluation model (Kirkpatrick W. K., Citation2016). in Appendix B contain the data extraction templates, which covered study details, the intervention and learner feedback.

Table 2. Characteristics of the 20 studies.

Table 3. Theoretical frameworks reported in 7 of the 20 articles.

CLK extracted data and conducted a descriptive, narrative analysis of the content and evaluation methods that included a presentation of descriptive data that were discussed in the author group. Uncertainties were discussed with JH, LKG, and/or JLS. Descriptive statistics were conducted in Excel (V.2016, Microsoft, Redmond, Washington DC, USA), but we did not conduct an optional critical appraisal of the included studies (Tricco et al. Citation2018). However, Kirkpatrick’s goal-based training evaluation model was applied to report the evaluation methods in the included studies (Barr et al. Citation2005). Supplementary Appendix Bcontains the extracted data.

Results

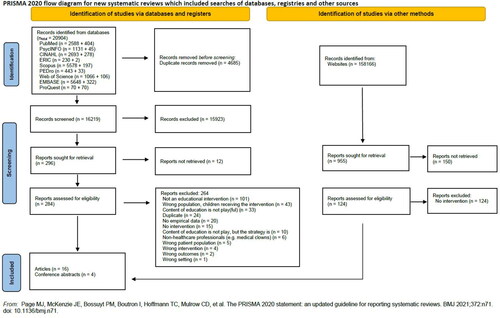

Initially our searches identified 16219 records from the white literature and 955 from the grey literature, resulting in the inclusion of 20 studies ().

Study characteristics

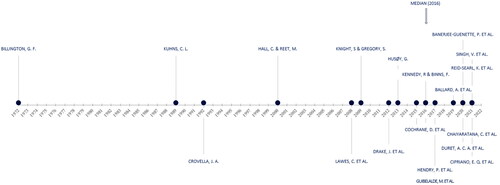

The included studies were published between 1972 and 2021 (). Most studies were intervention studies with a post-test design only () and were conducted in high-income countries, particularly in England (23%), USA (24%) and Canada (14%) ().

The number of participants varied from 1 to 202, with a median of 28. Eight of the 20 studies did not report the number of participants. Nursing staff and nursing students were the primary participants, followed by medical doctors, medical students, and psychology students ( and Supplemental Table S1).

Problem identification and needs assessment

The use of play varied among the twenty studies. Only five studies provided a definition for play, which varied among studies (Supplemental Table S2). Broadly speaking, the use of play was described as a need the child had irrespective of setting (Billington Citation1972), a changeable concept according to circumstances (Hall and Reet Citation2000) or a language in which to communicate age appropriately and effectively with a child in healthcare settings (Reid-Searl et al. Citation2021).

Seven of the 20 studies reported the theoretical framework used (). Drake et al. (Citation2012) used Bandura’s self-efficacy theory (Bandura Citation1977), not to directly frame the development process of the educational programme, but to encourage nurses to perceive the items in a coping kit (communication cards, social script book, and toys) as useful for communication and distraction.

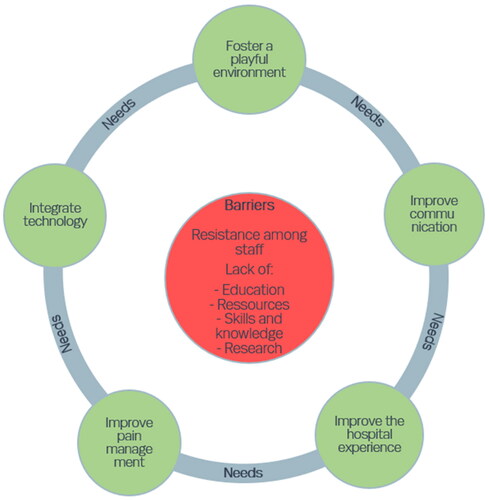

We identified five different categories of general needs in paediatric clinical practice that play would help to provide: foster a playful environment, improve communication, improve the patients’ hospital experience, improve pain management, and integrate technology. Moreover, five barriers associated with needs not being met were identified: resistance among staff, lack of education, lack of resources, lack of skills and knowledge, and lack of research ().

Educational strategies

Content

The educational programmes targeted three different purposes of using play in clinical practice ().

Table 4. Roles of play in the studies.Table Footnote*

Most of the studies took place in emergency departments and paediatric wards, with no further specification of setting (). Three studies took place at nursing schools, one of which included mock facilities (Reid-Searl et al. Citation2021). Two studies did not report any details on the intervention setting (Supplemental Table S1).

Table 5. Content and setting of educational programmes in the 20 studies.

In training of HCP’s in using play, distraction/coping kits were often seen as useful strategies. Items such as bubble blowing, light-up propellers, playing cards, chewable toys and the principal of five (five laminated cartoon characteristics, knowing how to produce five cartoon/animal sounds, knowing five rhymes, knowing how to make five faces, knowing how to play five hand games) were reported (Ballard et al. Citation2017; Singh et al. Citation2021).

To help HCPs support adolescents, a variety of playful tools were reported as means in the educational content, e.g. agenda cards, get-to-know-each-other cards, and scenario cards.

Methods of educational strategy

The twenty studies used a variety of educational strategies to teach participants about using play in clinical practice (, Supplemental Table S1).

Table 6. Educational strategies reported in 15 of the 20 studies.Table Footnote*.

The duration of the programmes varied widely, ranging from a brief notification about the availability of the kit (Drake et al. Citation2012) to minutes or hours (Supplemental Table S2), while other studies contained training sessions lasting one to several days. Some studies had follow-up sessions that used a stepwise approach comprising three implementation cycles (Singh et al. Citation2021), and implementation phases of six weeks to five months with ongoing supervision (Rasheed et al. Citation2021).

Those who taught the educational programmes also varied substantially, including nurses, physicians, paediatricians, physiotherapists, play school consultants, play specialists, youth workers and psychologists. Three studies mentioned that the instructors had received prior training in executing the programme (Drake et al. Citation2012; Banerjee-Guenette et al. Citation2020). Many studies (N = 7) did not provide any information about the instructor’s occupational background or qualifications (Supplemental Table S2).

Methods of measuring outcomes

Nineteen studies were single-group studies, and one study did not mention its design. Fifteen used a post-test only design, while five used a combined pre- and post-test design. None of the studies had a comparator group ().

Table 7. Study designs and measurements applied in the 20 studies.

Nine studies measured the programme outcomes qualitatively based on learner comments, semi-structured interviews, essays, reflection reports and debriefing sessions (Billington Citation1972; Kuhns Citation1989; Hall and Reet Citation2000; Knight and Gregory Citation2009; Husøy Citation2013; Cochrane Citation2015; Cipriano et al. Citation2021; Rasheed et al. Citation2021; Reid-Searl et al. Citation2021; Singh et al. Citation2021). Eight studies used either established or modified questionnaires, both open-ended and Likert scale. Four studies conducted observations (Kuhns Citation1989; Crovella Citation1992; Husøy Citation2013; Rasheed et al. Citation2021), and two studies included feedback from a third party assessing the transfer of learning on how to use play (Husøy Citation2013; Rasheed et al. Citation2021). Only one study assessed parental feedback related to HCP behaviours (Rasheed et al. Citation2021).

Three studies used scales validated in previous articles (Supplemental Table S3). One study used the Assessing Determinants of Prospective Take-up of Virtual Reality instrument (Levac et al. Citation2017), which measures twelve relevant aspects, such as attitude, superior influence and facilitating conditions for the adoption of virtual reality/active video gaming as a treatment modality (Banerjee-Guénette et al. 2020). One study used a scale called ‘a performa’ to record the time spent on daily screen time and play activities (Singh et al. Citation2021). Two of the studies applied the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (FLACC) scale and the Faces Pain Scale to evaluate the educational programme (Lawes et al. Citation2008; Ballard et al. Citation2017). Only one study made use of an objective, quantitative method of measurement via a virtual reality usage data collection form (Banerjee-Guénette et al. 2020). Two studies did not report the method of measurement (Supplemental Table S3).

Evaluation and feedback

Evaluation of programmes

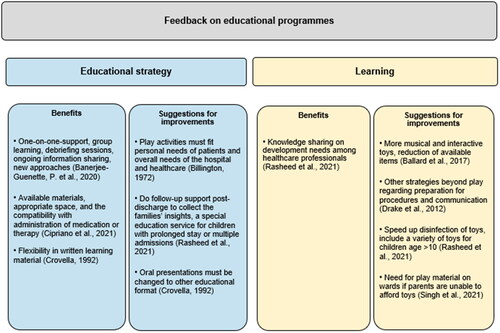

Many studies reported beneficial outcomes following the interventions and provided suggestions for the educational framework and content of the intervention (). Eighteen of 20 studies contained information on feedback on educational strategy and/or content (Supplemental Table S2).

Evaluation based on Kirkpatrick’s model

Kirkpatrick’s extended model, which is divided into six main levels (Barr et al. Citation2005), was applied to describe the evaluation methodologies of these educational programmes for HCPs on the use of play in paediatric clinical practice ( and Supplemental Table S3). Thirteen studies reported participant reactions (level 1), while seven evaluated changes in attitude among participants (level 2a) and three evaluated the acquisition of knowledge and skills on the use of play (level 2b). Six studies assessed a behavioural change among the HCPs (level 3) after participation in an educational programme about the use of play. One study reported outcomes on how training for HCPs about play affected organisational practice, such as the need for pharmacologic interventions, length of patients’ hospital stays, and impact on HCP behaviour (level 4a). Four studies assessed clinical outcomes following an educational programme about play, measuring factors such as children’s reactions to distress, and patient and family satisfaction throughout a hospital stay (level 4b). One study provided no information on the evaluation.

Discussion

The 20 articles in this scoping review provide insight into the state of educational programmes for HCPs on the use of play. We found that the main general needs of these educational programmes were fostering a playful environment, improving communication, improving pain management, and integrating technology into care. Based on these needs, we identified three different concepts of play that could be relevant to HCP education: 1) normalising play to cope and adapt, 2) procedural play, and 3) interventions to improve communication.

In the next section we discuss the articles organised within Kern’s six-step approach to curriculum development (Thomas et al. Citation2016).

Problem identification and needs assessment

A heterogeneous field

The educational programmes in play for HCPs are small and heterogenous. Despite a thorough literature search, this review was unable to identify an entire interprofessional educational programme for HCPs in the use of play in clinical paediatric practice. One reason might be that the practice of play is broader than the literature indicates. Play can be integrated into children’s healthcare experiences in many ways, for instance when HCPs engage with paediatric patients in hallways on paediatric wards using an invisible, experience-based toolbox of playful approaches that were not learned as part of a programme-based intervention. Another reason might be that a lack of transparency and the diffuse nature of the theoretical framework may complicate the exchange of experience, hampering the sharing of learning.

Implications across countries

The studies in this scoping review largely came from high-income countries, where play is already somewhat valued and included in healthcare environments (Corlett and Whitson Citation1999). Most paediatric hospitals and departments worldwide – even though some have health play specialists – will likely encounter the need to engage with children and young people in playful ways during the delivery of healthcare, which underpins the multidisciplinary need to utilise and understand the importance of children’s play (WHO Citation2017). As Rasheed et al. (Citation2021) emphasise, low- and middle-income countries are especially short of specialised HCPs equipped to help children cope with hospitalisation through play due to untrained staff and financial limitations. Thus, the need for qualified HCPs with knowledge about the therapeutic use of play exists everywhere, which is why play can and should play a role in children’s healthcare, health awareness and understanding.

Significance of needs assessment

Based on the articles in our review we found that performing a targeted needs assessment when designing an intervention on how to use play in paediatric clinical practice is advantageous. Some of the studies showed that HCPs had a need for programmes centred on how to incorporate play when meeting the child and performing procedures (). However, this review identified a lack of systematic preliminary assessments done to ascertain user needs (Billington Citation1972; Cipriano et al. Citation2021).

The study from Banerjee-Guénette (2020) used a questionnaire at baseline that provided a better understanding of the didactic preferences of learners, which influenced the subsequent educational strategy and implementation. In Lawes et al. (Citation2008, p. 35) study, one clinician showed a one-point decrease in confidence working with children undergoing painful procedures and in terms of performing painful procedures. The participants identify dealing with child distress and parents’ anxiety as difficult factors. This decrease could possibly have been targeted with inspiration from Fahnre et al. (Fahner et al. Citation2020). In Fahner et al.’s study, the participants (paediatricians) described the need for education on the implementation approach in a targeted needs assessment. The participants also emphasized the necessity of feeling confident when approaching and communicating with children.

Evaluation of programme development

The educational programmes were primarily evaluated as post-test design studies using convenience sampling and did not include comparator groups. We found that the studies also lacked needs assessments, primarily to design the intervention for a desired outcome based on the participants’ needs (Thomas et al. Citation2016). Other educational programmes succeeded in conducting more structured programmes, e.g. Wilkinson et al. (Wilkinson et al. Citation2021), which examined communication with disabled children who were hospitalised. Intervention planning benefitted from co-developing the programme jointly with HCPs and parents, with the subsequent implementation process based on Damschroder’s Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (Damschroder et al. Citation2009). Despite the lack of explicit play in Wilkinson et al.’s study, the methodical framework can serve as inspiration when designing future curricula.

Effect and involvement of healthcare professionals

We found that education regarding play for HCPs is typically delivered to mono-professional occupational groups, particularly nurses and nursing students. The programmes are mostly taught using workshops, sometimes supplemented by written or virtual educational material. The programmes last from hours to days, with sessions repeated weekly for a few months in some cases. When using play to help prepare children and adolescents for their care and treatment in hospital, the sustainability of the interventions must be considered in terms of the needs of HCPs. To understand and accommodate those needs, co-creation involving clinicians and management teams may be beneficial and improve the transferability of the intervention. Maintaining educational programmes on how to use play to an interprofessional group the use of play may be challenging due to the busy, variable, and high-pressure working environments of HCPs, as well as a potential lack of comfort in using play in clinical practice (Crovella Citation1992). Moreover, growing specialisation in medical environments can be a challenge to patient-centred care, perhaps making it difficult for clinicians to communicate the importance of play across the board (Hasnain-Wynia Citation2006). Singh et al. (Citation2021) emphasise that learners need to feel a sense of responsibility for the nature of an educational intervention and become an authority on the subject matter to integrate play in the daily practice. Feeling a sense of responsibility for the integration of play into one’s delivery of healthcare, on top of other critical clinical responsibilities, may be challenging to instigate.

Pre- and postgraduate learners

Pre- and postgraduate learners were represented in the studies in our scoping review. According to Crovella (Citation1992) conducting educational interventions for postgraduate learners in a clinical setting is difficult due to their work schedule and the unpredictability of emergencies. Thus, the framework and results of the interventions with pre-graduate students might be difficult to apply or repeat among postgraduate learners without modifications. On the other hand, early implementation of educational programmes that provide basic skills in communication and relationship building are likely beneficial for all healthcare students (Gilligan et al. Citation2021). Since HCPs encounter children as both patients and relatives in hospital settings, it is beneficial for HCPs to ensure their preparedness to ensure and support all aspects of patient safety in the future (Reid-Searl et al. Citation2021).

Patient involvement

Customised patient-reported questionnaires can provide an overview of user perspectives. Drawing on Lundy’s (Citation2007) model of child participation, for example, educational programmes and interventions can incorporate patients and parents as teachers of future practice (Lundy Citation2007; Gordon et al. Citation2020). A needs assessment would help to provide clarification of parents’ roles and current knowledge to ensure proper cooperation (Melo et al. Citation2014; Vasli and Salsali Citation2014). Parental involvement in play interventions is crucial to achieving child compliance as it makes children feel secure and helps guide their behaviour (Hill Citation2006).

One of the studies, which looked at the importance of parental interaction for strengthening parent-child interactions to reduce stress during hospitalisation for both parents and children (Rasheed et al. Citation2021), reflects that patient involvement is a growing trend. For instance, Cochrane (Citation2015) conducted a study where adolescent and young adults 16–25 years of age were invited to develop a youth engagement toolkit and co-deliver workshops with HCPs, an endeavour that was mutually appreciated. Patient involvement has important educational benefits for learners in the development of educational programmes (Jha et al. Citation2009; Towle et al. Citation2010; Gordon et al. Citation2020), just as their participation as teachers enhances the acquisition of knowledge and changes attitudes, adding value for themselves and the other learners (Wykurz and Kelly Citation2002).

To ensure that education in play becomes commonplace and accepted, it is important that HCPs are informed about play and experience the benefits of participating in an educational programme. One possible way to encourage educational programmes is to describe the play behaviour of patients in their medical records, as was the case in Rasheed’s (2021) study. Doing so gives HCPs access to information on successful icebreakers and play that can help facilitate a trusting relationship with the child that can be exceptionally valuable upon initial encounters, during complicated admissions involving several departments and in emergency departments, where the HCPs on duty frequently change.

Evaluation of and feedback on educational programmes

The educational frameworks of the programmes in play were characterised by a lack of transparency and systematisation. The definition of play varies, and it is notoriously difficult to define. The sparse literature is widely heterogenous: play is examined in different settings and various methods of evaluation are used, e.g. with a preponderance of qualitative questionnaires and only three studies reporting results using validated scales (Supplemental Table S3). When evaluating an educational programme at the organisation or hospital level, only including the participants’ reactions to the programme, i.e. Kirkpatrick level 1, is insufficient for substantial adherence or change.

Strengths and limitations

Applying the scoping review methodology proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute, combined with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA–ScR) checklist, ensured systematisation and transparency. The broad search strategy executed in collaboration with an information specialist also implied an inclusive approach to the subject. We chose the six-step approach to curriculum development and Kirkpatrick’s model to present the studies, which also helped to provide an even more structured approach. Finally, the systematic grey literature search we conducted based on Stapleton’s Grey Literature Search Plan Template further enhanced the strength of the review.

We used two independent reviewers to perform screening of title/abstracts, full texts, and grey literature, and any differences between reviewers were resolved through extensive discussions with the author group to reach consensus. One limitation is that only one reviewer (CLK) performed the final data extraction and synthesis. However, all the included studies were read by multiple authors, who carefully discussed the study characteristics, findings, and content of each educational intervention. In addition, this review is limited by the lack of transparency and low quality of the methods used in the included studies, which created a challenge in terms of drawing comprehensive conclusions about the educational programmes used. This issue can be ameliorated with increased awareness about the value of play in healthcare and further research in this area.

Conclusion and perspectives

This review highlights the lack of a structured, theoretical educational approach for HCPs to obtain competencies on how to use play in paediatric clinical practice. With this information, there is room for substantial further research regarding the integration of play in paediatric healthcare delivery and development of future systematic educational programmes that appropriately include the needs of HCPs, patients, and parents. Box 1 presents ideas for future educational programmes.

Box 1. Suggestions for future educational programmes

Clarify the needs of paediatric healthcare professionals (HCPs), patients (children and adolescents), and parents to ensure sustainable and transferable interventions

Use a theoretical framework in the study design to develop a relevant educational programme addressing the needs of paediatric HCPs and patients

Include a larger sample to provide a more precise estimate of the effect of the educational programme and consider which evaluation methods to use

Include various occupational groups and, if possible, multiple healthcare settings

Document the results of each play intervention in the patient’s medical record so other HCPs are aware of the child’s preferences

Use blind assessors to minimise the risk of bias when interpreting results

Use validated measurements to do systematic evaluations when possible. Kirkpatrick’s model is a good starting point

Conducting longitudinal studies with validated scales would make it possible to show the benefits of educational programmes in play, for example in terms of improved compliance and cooperation during physical examinations and treatment, giving children and young adults the opportunity to manage their illness more appropriately, decreasing traumatisation and making strategic use of critical resources and time.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (104.8 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest. The work is partly funded by the LEGO Foundation, which did not play any role in the study design, preparation of the protocol, or in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Christine Louise Krebs

Christine Louise Krebs, MD, has an interest in paediatrics and experience in conducting scoping reviews.

Jakob Thestrup

Jakob Thestrup, MSc, is a PhD fellow and has experience in research methodologies.

Jane Hybschmann

Jane Hybschmann is a PhD fellow experienced in review methodologies and conducting systematic searches in paediatrics. She is particularly interested in evaluating hospital experiences including play in hospital.

Kelsey Graber

Kelsey Graber is a PhD fellow with a psychological background and a particular focus on the role of play in affecting quality of life during paediatric care for children with chronic or severe illness.

Line Klingen Gjærde

Line Klingen Gjærde, PhD, MD, is a paediatric registrar with experience in paediatrics and using registry linkages, statistical programming, and big data. She is particularly interested in improving hospital experiences for children and adolescents.

Martha Krogh Topperzer

Martha Krogh Topperzer, MSc, PhD, is a clinical nursing specialist with experience in designing, conducting, and implementing mono- and interprofessional postgraduate education in childhood cancer. She also has extensive educational experience in pre-graduate nursing education in the clinical setting.

Emilie Tange Nielsen

Emilie Tange Nielsen, BSc, is a master’s student in public health science at the University of Copenhagen and has experience in review methodologies.

Anders Larsen

Anders Larsen, MLIS, is an information specialist experienced in designing and conducting systematic literature searches.

Paul Ramchandani

Paul Ramchandani is a child and adolescent psychiatrist, LEGO Professor of Play in Education, Development and Learning (PEDAL) at Cambridge University, United Kingdom and the director of the PEDAL Research Centre.

Thomas Leth Frandsen

Thomas Leth Frandsen is a paediatrician specialised in paediatric haematology and oncology. He is the Chief Medical Project Officer at Mary Elizabeth’s Hospital, University of Copenhagen – Rigshospitalet and previously team leader of the Haematology/Oncology ward at the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine at Rigshospitalet.

Jette Led Sørensen

Jette Led Sørensen specialises in obstetrics and gynaecology and is a professor of interprofessional education. Experienced in medical education, including research in curriculum development, implementation, and evaluation of educational programmes for various healthcare professionals and specialities, she has conducted numerous research and development projects, including assessment and implementation of simulation-based training.

References

- Adams RJ, Smart P, Huff AS. 2017. Shades of grey: guidelines for working with the grey literature in systematic reviews for management and organizational studies. Int J Manage Rev. 19(4):432–454. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12102.[Mismatch]

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. 2005. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Ballard A, Le May S, Khadra C, Lachance Fiola J, Charette S, Charest MC, Gagnon H, Bailey B, Villeneuve E, Tsimicalis A. 2017. Distraction kits for pain management of children undergoing painful procedures in the emergency department: a pilot study. Pain Manag Nurs. 18(6):418–426. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2017.08.001.

- Bandura A. 1977. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol Rev. 84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191.

- Banerjee-Guenette P, Bigford S, Glegg SMN. 2020. Facilitating the implementation of virtual reality-based therapies in pediatric rehabilitation. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 40(2):201–216. doi: 10.1080/01942638.2019.1650867.

- Barr H, Koppel I, Reeves S, Hammick M, Freeth D. 2005. Effective interprofessional education: argument, assumption, and evidence. Vol. xxiv. Oxford: Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education in Primary Health and Community C.

- Billington GF. 1972. Play program reduces children’s anxiety, speeds recoveries. Mod Hosp. 118(4):90–92.

- Bloch YH, Toker A. 2008. Doctor, is my teddy bear okay? The “Teddy Bear Hospital” as a method to reduce children’s fear of hospitalization. Isr Med Assoc J. 10(8-9):597–599.

- Chaiyaratana, et al. 2020. Integrating child life program into pediatric training course for nursing students, the effective way to provide child life service in resource limited country Pediatric Blood and Cancer. Conference: 52th Congress of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology. SIOP Virtual. 67(SUPPL 4):2020.

- Cipriano EQ, Laignier MR, Júnior JF, Da Silva LF, Bastos Depianti JR, Nunes Nascimento LdC 2021. Experimenting to play with hospitalized child: perception of nursing student [Experimentando o brincar junto a criança hospitalizada: percepção do acadêmico de enfermagem]. RPCF. 13:1329–1335. doi: 10.9789/2175-5361.rpcfo.v13.10018.

- Cochrane D. 2015. Youth Engagement Toolkit for healthcare professionals how do we engage better with young people with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Nurs. 19:228–232.

- Corlett S, Whitson A. 1999. Play and culture. Paediatr Nurs. 11(7):28–29. (doi: 10.7748/paed.11.7.28.s17.

- Crovella JA. 1992. Development of an inservice training program for health care professionals working with pediatric patients to increase awareness of needs and concern.

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. 2009. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 4(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

- Drake J, Johnson N, Stoneck AV, Martinez DM, Massey M. 2012. Evaluation of a coping kit for children with challenging behaviors in a pediatric hospital. Pediatr Nurs. 38(4):215–221.

- Duret ACA, Johnson RA, Zhang C, Sim MYL, Wren FE. 2019. Evaluation of project play, a student-led volunteering scheme. Arch Dis Childhood. 104(Suppl. 2):A257–A258. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2019-rcpch.615.

- Fahner J, Rietjens J, van der Heide A, Milota M, van Delden J, Kars M. 2020. Evaluation showed that stakeholders valued the support provided by the Implementing Pediatric Advance Care Planning Toolkit. Acta Paediatr. 110(1):237–246. doi: 10.1111/apa.15370.

- Gilligan C, Powell M, Lynagh MC, Ward BM, Lonsdale C, Harvey P, James EL, Rich D, Dewi SP, Nepal S, et al. 2021. Interventions for improving medical students’ interpersonal communication in medical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2(2):CD012418. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012418.pub2.

- Gjærde LK, Hybschmann J, Dybdal D, Topperzer MK, Schroder MA, Gibson JL, Ramchandani P, Ginsberg EI, Ottesen B, Frandsen TL, et al. 2021. Play interventions for paediatric patients in hospital: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 11(7):e051957. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051957.

- Godin K, Stapleton J, Kirkpatrick SI, Hanning RM, Leatherdale ST. 2015. Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: a case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Syst Rev. 4(1):138. doi: 10.1186/s13643-015-0125-0.

- Godino-Iáñez MJ, Martos-Cabrera MB, Suleiman-Martos N, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Vargas-Román K, Membrive-Jiménez MJ, Albendín-García L. 2020. Play therapy as an intervention in hospitalized children: a systematic review. Healthcare (Basel). 8(3):1–12. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8030239.

- Gordon M, Gupta S, Thornton D, Reid M, Mallen E, Melling A. 2020. Patient/service user involvement in medical education: a best evidence medical education (BEME) systematic review: BEME Guide No. 58. Med Teach. 42(1):4–16. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1652731.

- Gaynard L. 1990. Psychosocial care of children in hospitals: a clinical practice manual. Bethesda, MD: Association for the Care of Children’s Health.

- Guibelalde, et al. 2016. Working without words: where music, theater, meditation, laugher and magic can reach Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 63:S280.

- Guralnick MJ, Hammond MA. 1999. Sequential analysis of the social play of young children with mild developmental delays. JEarly Interv. 22(3):243–256. doi: 10.1177/105381519902200307.

- Haiat H, Bar-Mor G, Shochat M. 2003. The world of the child: a world of play even in the hospital. J Pediatr Nurs. 18(3):209–214. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2003.28.

- Hall C, Reet M. 2000. Enhancing the state of play in children’s nursing. J Child Health Care. 4(2):49–54. doi: 10.1177/136749350000400201.

- Harden RM. 1986. Ten questions to ask when planning a course or curriculum. Med Educ. 20(4):356–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1986.tb01379.x.

- Hasnain-Wynia R. 2006. Is evidence-based medicine patient-centered and is patient-centered care evidence-based? Health Serv Res. 41(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00504.x.

- Hendry P, Hernandez DE, Kalynych C. 2017. Child life 101 for emergency departments and emergency care providers: using non-pharmacologic methods and a distraction “toolbox” to relieve and manage pain and anxiety. Acad Emerg Med. 24(Suppl 1): s 295.

- Hill A. 2006. Play therapy with sexually abused children: including parents in therapeutic play. Child Family Social Work. 11(4):316–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00411.x.

- Husøy G. 2013. Teddy Bear Hospital – students’ learning in the field of practice with children. Vaard i Norden. 32:51–55.

- Jha V, Quinton ND, Bekker HL, Roberts TE. 2009. Strategies and interventions for the involvement of real patients in medical education: a systematic review. Med Educ. 43(1):10–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03244.x.

- Kirkpatrick WK, D KJ. 2016. Evaluating training programs: the four levels. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Knight S, Gregory S. 2009. Specialising in play. Emerg Nurse. 16(10):16–19. doi: 10.7748/en2009.03.16.10.16.c6849.

- Koukourikos K, Tzeha L, Pantelidou P, Tsaloglidou A. 2015. The importance of play during hospitalization of children. Mater Sociomed. 27(6):438–441. doi: 10.5455/msm.2015.27.438-441.

- Krebs CL, Hybschmann J, Graber K, Gjærde LK, Topperzer MK, Hansen JT, Nielsen ET, Larsen A, Ramchandani P, Sørensen JL. 2022. A BEME scoping review of educational programmes on how to use play in paediatric clinical practice for healthcare professionals. https://osf.io/j38tk/.

- Kuhns CL. 1989. The hospital playroom an enriching clinical experience for nursing students. Child Health Care. 18(3):153–156. doi: 10.1207/s15326888chc1803_5.

- Lawes C, Sawyer L, Amos S, Kandiah M, Pearce L, Symons J. 2008. Impact of an education programme for staff working with children undergoing painful procedures. Paediatr Nurs. 20(2):33–37. doi: 10.7748/paed2008.03.20.2.33.c6528.

- Lender WLea. 1998. Repetetive activity in the play of children with mental retardation. J Early Learn Interv. 21(4):208–322.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. 2010. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Sci. 5(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Levac D, Glegg S, Colquhoun H, Miller P, Noubary F. 2017. Virtual reality and active videogame-based practice, learning needs, and preferences: a cross-canada survey of physical therapists and occupational therapists. Games Health J. 6(4):217–228. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2016.0089.

- Lundy L. 2007. ‘Voice’ is not enough: conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Br Educ Res J. 33(6):927–942. doi: 10.1080/01411920701657033.

- Melo EM, Ferreira PL, Lima RA, Mello DF. 2014. The involvement of parents in the healthcare provided to hospitalzed children. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 22(3):432–439. doi: 10.1590/0104-1169.3308.2434.

- Nijhof SL, Vinkers CH, van Geelen SM, Duijff SN, Achterberg EJM, van der Net J, Veltkamp RC, Grootenhuis MA, van de Putte EM, Hillegers MHJ, et al. 2018. Healthy play, better coping: the importance of play for the development of children in health and disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 95:421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.09.024.

- Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. 2020. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Edited by MZ Aromataris. University of Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. doi: 10.46658/JBIMES-20-12.

- Rasheed MA, Bharuchi V, Mughis W, Hussain A. 2021. Development and feasibility testing of a play-based psychosocial intervention for reduced patient stress in a pediatric care setting: experiences from Pakistan. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 7(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s40814-021-00781-8.

- Reid-Searl K, Crowley K, Anderson C, Blunt N, Cole R, Suraweera D. 2021. A medical play experience: preparing undergraduate nursing students for clinical practice. Nurse Educ Today. 100:104821. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104821.

- Singh V, Kalyan G, Saini SK, Bharti B, Malhi P. 2021. A quality improvement initiative to increase the opportunity of play activities and reduce the screen time among children admitted in hospital setting of a tertiary care centre, North India. Indian J Pediatr. 88(1):9–15. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03249-4.

- Stenman K, Christofferson J, Alderfer MA, Pierce J, Kelly C, Schifano E, Klaff S, Sciolla J, Deatrick J, Kazak AE. 2019. Integrating play in trauma-informed care: multidisciplinary pediatric healthcare provider perspectives. Psychol Serv. 16(1):7–15. doi: 10.1037/ser0000294.

- Thomas PA, Kern DE, Hughes T, Chen BY. 2016. Curriculum development for medical education – a six step approach. Baltimore (MD): John Hopkins University Press.

- Towle A, Bainbridge L, Godolphin W, Katz A, Kline C, Lown B, Madularu I, Solomon P, Thistlethwaite J. 2010. Active patient involvement in the education of health professionals. Med Educ. 44(1):64–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03530.x.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, et al. 2018. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850.

- Vasli P, Salsali M. 2014. Parents’ participation in taking care of hospitalized children: a concept analysis with hybrid model. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 19(2):139–144. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4020022/.

- WHO. 2017. Children’s rights in hospital: rapid-assessment checklists. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/342769/Check-list-Child-rights-in-hospital_layoutOPE.pdf.

- Wilkinson K, Gumm R, Hambly H, Logan S, Morris C. 2021. Implementation of training to improve communication with disabled children on the ward: a feasibility study. Health Expect. 24(4):1433–1442. doi: 10.1111/hex.13283.

- Williams NA, Ben Brik A, Petkus JM, Clark H. 2019. Importance of play for young children facing illness and hospitalization: rationale, opportunities, and a case study illustration. Early Child Dev Care. 191(1):58–67. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2019.1601088.

- Wykurz G, Kelly D. 2002. Developing the role of patients as teachers: literature review. BMJ. 325(7368):818–821. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7368.818.