Abstract

Purpose

In simulation-based education (SBE), educators integrate their professional experiences to prepare learners for real world practice and may embed unproductive stereotypical biases. Although learning culture influences educational practices, the interactions between professional culture and SBE remain less clear. This study explores how professional learning culture informs simulation practices in healthcare, law, teacher training and paramedicine.

Methods

Using constructivist grounded theory, we interviewed 19 educators about their experiences in designing and delivering simulation-based communication training. Data collection and analysis occurred iteratively via constant comparison, memo-writing and reflexive analytical discussions to identify themes and explore their relationships.

Results

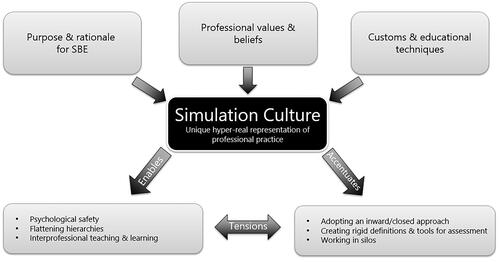

Varied conceptualizations and enactments of SBE contributed to distinct professional learning cultures. We identified a unique ‘simulation culture’ in each profession, which reflected a hyper-real representation of professional practice shaped by three interrelated elements: purpose and rationale for SBE, professional values and beliefs, and educational customs and techniques. Dynamic simulation cultures created tensions that may help or hinder learning for later interprofessional practice.

Conclusion

The concept of simulation culture enhances our understanding of SBE. Simulation educators must be mindful of their uni-professional learning culture and its impacts. Sharing knowledge about simulation practices across professional boundaries may enhance interprofessional education and learners’ professional practice.

Practice points

A practice-based approach views simulation as a microculture.

‘Simulation culture’ describes the unique hyper-real representation of professional practice.

Simulation educators should be aware of how their unique simulation culture may embed implicit or hidden biases that impact learning.

The concept of simulation culture may foster knowledge sharing across professional boundaries.

Introduction

Healthcare simulation has revolutionised health professions education (HPE). Educators in other sectors have also adopted simulation-based education (SBE) to prepare competent professionals to manage workplace challenges. However, conceptualisations of simulation vary widely across sectors, exemplified by a litany of terms to describe these practices (Strevens et al. Citation2014), limiting knowledge exchange from educators in other professions. For example, simulation means technology in some sectors, with virtual reality and artificial intelligence featuring heavily (Bligh and Bleakley Citation2006). In contrast, simulation also engages humans, namely simulated participants, in recreating specific scenarios to train individual or team-based behavioural skills (Issenberg et al. Citation2005; Al-Elq Citation2010).

Professionals require more than individual knowledge and skills to work in teams, yet educational efforts in healthcare often remain siloed and reinforce entrenched uni-professional norms (Stalmeijer and Varpio Citation2021). These persistent uni-professional learning cultures may inadvertently perpetuate professional stereotypes (Nestel et al. Citation2014). For example, SBE for doctors-in-training often includes an embedded simulated participant as a nurse, who only acts on direct instructions so educators may identify learners’ knowledge and skill gaps, in line with pre-defined learning objectives (Somerville et al. Citation2023). Indeed, experienced nurses bring extensive professional agency to their clinical practice, often guiding early career doctors (Stalmeijer and Varpio Citation2021). Thus, well-meaning educational choices in simulation that misrepresent nurses’ contribution may have unintended and potentially negative consequences by amplifying power dynamics and reinforcing counterproductive communication patterns. Therefore, healthcare simulation educators must remain mindful about the potential for perpetuating a physician-dominant culture that directly shapes interprofessional communication practices.

In HPE research, culture is recognised as complex, ill-defined and confusing (Bearman et al. Citation2021). Most scholarly work refers to culture in an organisational context, with little focus on microculture at profession and practice levels. Early findings suggest that culture is transmitted during educational events such as simulation (Purdy et al. Citation2019). These implicit messages, or hidden curriculum (Mulder et al. Citation2019) may shape learning with potentially unintended consequences. For our study, we take a predominantly practice-based approach to culture; indeed, microcultures during SBE may not represent professional workplace practice (Bligh and Bleakley Citation2006). This practice-based approach focuses on what happens in the activity between people and things and how their interactions shape our work over time (Watling et al. Citation2020). We need to better understand how these microcultures potentially influence learning.

Communication represents one domain of professional practice, cutting across disciplines and also reflecting culture. In healthcare, communication failures lead to most patient safety errors (Helmreich and Merritt Citation1998; Kohn et al. Citation2000). In court, lawyers persuade based on their ability to construct clear concise arguments (Strevens et al. Citation2014), and teachers convey important lessons by engaging pupils in storytelling and other interactions (Grossman et al. Citation2009). The ability to communicate effectively, both within professional groups and across professional boundaries, represents a vital skill across domains. This capability shapes individual effectiveness, fosters favourable team dynamics, and influences organisational culture (Motola et al. Citation2013). Given its importance, SBE for communication training has expanded, affording opportunities to gain broader perspectives by comparing and contrasting simulation practices for communication training across sectors. A better understanding of SBE in these professional domains would enable: (a) insights into how learning cultures develop and perpetuate unhelpful stereotypes and (b) opportunities to improve SBE to foster skill transfer to workplace environments.

This paper explores how simulation practices are understood and enacted across four professional domains (healthcare, law, teacher training and paramedicine) in which communication training features in educational practice. Through comparative analysis we aim to uncover how these practices influence learning culture.

Methods

We used a sociocultural theory lens since it emphasises human interactions and broader social, cultural, and historical contexts of human activity (Vygotsky Citation1978; Lave and Wenger Citation1991; Wenger Citation1998). Thus, sociocultural perspectives highlight the learning culture that fosters meaningful interactions that drive learning (Lave and Wenger Citation1991; Eppich et al. Citation2016). Learning culture refers to the shared attitudes, beliefs, practices, and values that underpin how an institution or a profession designs the education of its learners (Watling Citation2015). A sociocultural lens has been used previously to compare learning cultures in medicine and music (Watling et al. Citation2013).

Using constructivist grounded theory (CGT), we explored participants’ experiences in using SBE for communication skills training. CGT recognises the role of the researchers, as well as the participants in research processes, which requires reflexivity (Watling and Lingard Citation2012; Eppich et al. Citation2019). The study’s lead author (MOT) is a firefighter/advanced paramedic and health professions educator. Other collaborators are experienced simulation educators with varied backgrounds, including, medical physics (AJD), education (NC), engineering (CS), geology (CM), biology (CC), clinical psychology (ED), and paediatric emergency medicine (WJE). Three researchers have ‘insider status’ in the studied domains (MOT, NC and WJE) and we reflected on our positionality during analytical meetings.

All participants were based in Ireland and were invited to participate via e-mail. Through purposive sampling, we identified experienced participants from healthcare, law, teacher training, and paramedicine, who then recommended others in their fields. Professionals from these domains are involved in child safeguarding, a particular research interest in our group. Specifically, child safeguarding issues demand effective interprofessional and cross-disciplinary communication across these domains to protect children at risk of abuse and neglect. As our sampling strategy evolved, we identified several participants with professional experiences in multiple domains, which informed our analysis and theoretical sampling in latter stages. The RCSI research ethics committee approved the study (REC 202103017). All participants provided informed consent.

MOT and NC conducted individual semi-structured interviews (see Suppplementary Appendix 1), between June 2021 and June 2022 (Eppich et al. Citation2019). All interviews took place through video conferencing software (Microsoft Teams), lasted 45-60 min, were recorded, transcribed, checked for accuracy and de-identified. We analysed data iteratively using constant comparison consistent with CGT (Charmaz Citation2014). MOT and NC identified initial codes and discussed them at team analytical meetings. Our iterative analytical process shaped our sampling strategy and approach to interviews. Focused coding enabled us to explore the relationships between categories and elevated our analysis from descriptive to conceptual (Charmaz & Thornberg; Citation2021; Charmaz Citation2014). Data analysis concluded when we reached theoretical sufficiency (Varpio et al. Citation2017), achieving enhanced conceptual understanding. NVivo qualitative analysis software (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2018, Version 12) supported our data analysis.

Results

We recruited 19 communication skills educators across healthcare, law, teacher training and emergency services (See for participant demographics). Of note, six participants identified with more than one professional domain. We described these participants using their primary profession, followed by an asterisk to preserve their anonymity given their highly unique professional backgrounds. For example, Participant 1, Doctor* denotes that this participant is primarily a doctor with experience in another professional field.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

We identified synergies between how educators characterised their professional learning culture and how they engineered a bespoke learning culture for SBE. These synergies between simulation activities and professional culture imbued simulation practices with their own distinct learning culture, or simulation culture, in each professional domain. This constructed hyper-real simulation culture, transmitted an overarching professional ethos that often remained implicit, given its embedded nature within educational activities.

Three main interrelated elements contributed to the development and perpetuation of these distinct simulation cultures: a) rationale and purpose of SBE; b) professional values and beliefs, and c) customs and educational techniques (see ). These unique simulation cultures both shaped and facilitated educational practices, exerting potentially both powerful benefits and unintended consequences. We now describe our main findings by expanding on elements that contribute to simulation culture, providing examples across professional domains.

Purpose of and rationale for SBE

All participants provided nuanced justifications for SBE across domains. For some, error reduction and safety concerns loomed large. Healthcare educators reported exposing students to real world problems in a safe environment without risk to patients: ‘I will get 300 students to see…conflict between a relative and a staff member and to deal with that… the harsh reality is that will happen possibly within the first hour when they start working’ (P8, Doctor).

To minimise error, allied healthcare educators developed their simulation-based communication curricula using patient feedback comments… ‘all the time [as a] driver for the (communication simulation) work’ (P1, Allied Healthcare Professional). Error reduction was echoed with greater urgency across other fields in which professionals themselves were also placed in harm’s way. This potential threat for one’s own safety greatly influenced the perceived need for training and perceptions of hierarchy: ‘They talk about there being no rank in the cockpit…. And I think part of that is the culture of it… if we crash the plane, we both die. I'm not saying that the healthcare people don’t care about their patients, but I think it’s not quite the same’ (P16, Allied Healthcare Professional*).

Educators described optimal simulation practices differently. Even the term ‘practice’ varied across domains, with diverse terminologies describing similar activities e.g. teacher trainers used the term practice to highlight that ‘every job has certain practices that are key to it…some use words like ‘skill’…this is a little bit too narrow because you might have a skill and not know when to apply it. So, a ‘practice’ is knowing how to do something well and when it’s appropriate to do it’ (P2, Teacher). In paramedicine, deliberate practice is used to teach ‘skills’; hence experiential practice is skills-based learning. ‘Our focus has always been on skills, competencies and being proficient and able to do that skill’ (P19, Paramedic).

These notions of practice influenced how training was conceptualised. Educating ‘ideal teachers’ who applied the best possible communication techniques was the purpose of training for teachers to interact authentically with students’ parents. ‘We identify ten practices in the research…that make for a good parent-teacher meeting….then we ask observers to say whether each of these was done or was not done’ (P2, Teacher). In contrast, paramedic educators valued strict adherence over idealism, focusing on training algorithms, using tools and mnemonics. For example, paramedic students were trained to deliver standardised and concise patient handovers: ‘…at the start they’re using [the mnemonic] rigidly and. …it’s almost like a prayer (P19, Paramedic). In time, paramedic students fostered their own communicative styles, but only after conforming to highly prescriptive memory aids.

Conversely, allied health and legal educators sought to foster empathy and understanding for clients and patients as the fundamental aim for their communication training. ‘You’re learning how to establish a rapport, how to explore issues with families, how to manage conflict… resistance, how to mirror empathy …, all the basic kind of communication skills’ (P12, Allied Healthcare Professional). This common thread featured among many other patient or client facing professions. One legal educator raised provocative ethical considerations in communication training. ‘We talk about empathy…it’s all very well that you’d be able to empathise with the victim… but the challenge is how do you empathise with a suspect?’ (P9, Legal Professional).

Finally, how educators framed the purpose of training promoted buy-in and learner engagement’…it’s not packaged as communication skills, it’s packaged as preparation for practice’ (P12, Allied Healthcare Professional). Communication skills training was traditionally perceived as less important than their professional, clinical or technical skills, sometimes causing ‘eye-rolls’ (P16, Allied Healthcare Professional*) among students and professionals alike. Educators across professions recommended integrating communication skills training in the curriculum rather than as a standalone module: ‘…Communication always has to be taught in context…not on its own, where you tell the students, hey, look, we have a communication class… come over here. That doesn’t work’ (P17, Teacher).

Professional values and beliefs

Values embodied the professionals’ core beliefs in each domain and, accordingly, informed what they prioritised for SBE. Some values transcended domains such as professionalism, respect and integrity. Across all professions, educators appeared to embed their dominant values into their simulation activities, which influenced learner professional identity formation. However, other values were emphasised differently according to professional context, such as collegiality in teaching and equity and empathy in law (see ).

Table 2. Disparate cultural priorities across professions.

Legal educators valued effective self-presentation to manage impressions of their capabilities. ‘…We have voice coaches and actors for the first few workshops, rather than lawyers to get them thinking about how they speak, how they come across and how they sound’ (P4, Legal Professional). Legal educators revered the ability to perform under pressure and to maintain their professional status: ‘We also have them handling questions from the audience. …when you’re in a courtroom…you need to be able to hold your own’ (P4, Legal Professional). Thus, lawyers in training engaged in ‘practical sessions’ (P11, Legal Professional) to practise handling difficult questions in a safe, yet pressurised environment.

Educators foregrounded notions of ‘safety’ in nuanced and divergent ways. Some emphasised personal safety, such as preparing for litigious situations in a safe simulated environment. In contrast, results driven, patient-centred care was essential in healthcare: ‘It all comes back to patient safety. You go into your discipline…to make people feel better, to impact positively on their hospital journey, their illness….your goal is to do no harm…’ (P3, Nurse). Healthcare Professionals (HPs) also perceived psychological safety as a key feature of SBE. Negative learning experiences threatened psychological safety through blaming or shaming in response to suboptimal performance, with detrimental effects on student wellbeing and learning. ‘There’s the mindset that simulation is safe…that we can push people to the edge [but] you can actually have a negative impact on their learning and…they never do simulation again… [as in] “You’re looking at me through one-way mirrors and it’s like interrogation”’ (P8, Doctor).

Rather than notions of ‘safety’, teacher educators valued ‘quality’ interactions with both children and families as well as professional colleagues. This notion of ‘quality’ was linked to professionalisation of teachers: ‘There’s quite a body of writing around professionalisation of teaching and, it’s almost like ‘don’t be telling them that’s [simulation] what we get up to’… that we actually train these people to do the practical side of their job…’ (P10, Teacher). Thus, for teachers their interactions needed to embody genuine empathy and respect: ‘…They need to be able to…let the parents know that the student [teacher] knows their child well’ (P2, Teacher). Teachers highly valued positive relationships with teaching colleagues, making critical feedback and peer observation of learning quite challenging. ‘Teachers tend to have…cordial relationships…they’re very friendly and very affirming of each other. It’s very rare… for a teacher to challenge a colleague’ (P2, Teacher).

Notions of challenging colleagues also surfaced in healthcare; one educator highlighted how speaking up against a colleague could impact future career prospects. ‘…Consultants [are] still not called by their first names, there’s a steeper hierarchy; …Ireland is a very small country. People are scared to [speak up] and… don’t want to get a bad reputation’ (P16, Allied Healthcare Professional*). This hierarchical struggle also raised barriers to speaking up between paramedic students and clinical leaders: ‘We need to do work on the perception of the god-like figure, particularly of the [Advanced Paramedic] coming in saying ‘I'm in charge’…. the students should still be able to communicate with them… We’re working together, not this, “I'm in charge now…I have arrived, take my cloak”!’ (P19, Paramedic).

In paramedicine, unit pride was a unique core value embodied in simulation activities. Camaraderie shaped paramedic unit culture, leading to a sense of shared goals, mutual understanding, and deep respect. ‘[Paramedics] are very proud of the unit they’re from. I don’t hear anybody saying I'm so proud to be at [Hospital]…it’s not the same…there’s not the same sense of pride or cohesiveness’ (P16, Allied Healthcare Professional*). This unit culture also fostered a positive sense of teamwork and a collegial competitiveness: ‘I don’t feel that [positive unit culture] happens in healthcare, there’s a lot of competition and “dog-eat-dog,” and “what’s good for me might be bad for you”’ (P16, Allied Healthcare Professional*). These professional values shaped the learning culture of professions, teams and organisations, with downstream impacts on simulation training and its unique ‘simulation culture’.

Customs and educational techniques

Customs referred to how simulation was designed and implemented, based on the background, history and professional identity of that particular profession. Based on our analysis, the four domains varied widely in terms of how they embedded SBE and how their educational practices aligned with professional culture. Some sectors outlined theory-based stages of experiential learning, while others drew primarily on authentic examples from professional practice to inform simulation activities and prepare students for workplace realities.

Our participants described concrete educational techniques they used that reflected simulation practices in their respective domain. Across healthcare more broadly, the term ‘simulation’ had an agreed upon meaning and a well-accepted and established methodology. SBE was designed and implemented widely for undergraduate education, ‘simulation is assessing their ability to address situations that are changing, …where there’s a (patient) deterioration, identifying that, responding appropriately and knowing what to do in those situations’ (P6, Nurse). Teachers greatly emphasised theoretical and social understanding in line with the professional roots of education, using a three-stage process for SBE curriculum design, namely ‘representing, deconstructing and approximating practice’ (P2, Teacher). These three theoretically grounded stages exemplified the stark differences between experiential practice sessions and real-life tasks; teachers deemphasized realism compared with healthcare educators. One participant noted that ‘“approximating” is where the student teacher acts in the role of a teacher, because it’s close to practice, but it’s not actual practice… it doesn’t have the high stakes. If they do or say something insensitive, they’re [only] speaking to one of their peers or an actor’ (P2, Teacher). While rehearsing, student teachers were stopped mid-scenario to discuss potential challenges and then repeat the practice to apply a newly learned technique. ‘We see rehearsing as being a step down [from approximating] because during a rehearsal you might actually say ‘okay, we’re going to take that again from X line’ (P2, Teacher).

While healthcare and teacher educators intentionally modulated simulation realism up or down, this deliberate deviation from real life was not explicit in other domains e.g. legal educators used a ‘moot court’ (P11, Legal Professional) to simulate a courtroom. These sessions were not framed in terms of realism but more in terms of ‘very practical… to prepare [law students] for…practice’ (P11, Legal Professional). In paramedicine, educators lacked formal training in SBE and improvised by drawing heavily on life experiences. ‘Some of the stuff we actually use is real stuff… because of the job we do, we all know the big incidents that have happened’ (P7, Paramedic). This reliance on educators’ own professional experience suffused these SBE encounters with practical knowledge that was highly situated in the educator’s recollection of specific workplace contexts.

Irish paramedic educators highlighted the relative lack of professionalisation since paramedicine was not a fully established allied health profession. As a result, even university based training focused on vocational and apprenticeship styles of learning, integrating workplace and simulation-based learning with mentorship: ‘I don’t believe that we get great education in terms of communication [in simulation]…this was very much learned by examples from your colleagues when you went [to the] station and you went on calls’ (P5, Paramedic). Paramedic educators also discussed constraints related to funding and training time, and how they had to ‘make do [with what they had] …it’s very difficult because in higher education, it tends to be a lean operation (P5, Paramedic).

Post-simulation debriefings occurred regularly across domains with varying focus. In healthcare, debriefing was praised for promoting shared reflective practice: ‘the best debriefs…they just debrief each other, they do 90% of the talking…lots of self-realisation, self-discussion, peer debrief …[I’m] not preaching at them’ (P14, Doctor). The legal sector encouraged reflection by ‘let [them] take a breath…start out with very clear questions and give more space to talk. Limit feedback to two pieces of information…also use their own words back’ (P4 Legal Professional). In paramedicine, however, debriefings focused more on instructor-led directive feedback based on adherence to practise guidelines and necessary changes for next time. ‘The focus is always on the clinical performance, did they perform in accordance to the standard and the [Clinical Practice Guidelines] and then it stops’ (P19, Paramedic). This approach was comparable to teacher training, where they used a ‘holistic observation record’ (P2, Teacher), peer feedback often became ‘a checkbox exercise… some students are better at giving feedback to peers than others’ (P2, Teacher).

Influence of simulation culture on education

In addition to these three core interactive elements that establish the simulation culture, we also identified how the simulation culture itself actually caused educational tensions, by both enabling positive factors while simultaneously highlighting less favourable factors (). These factors accentuated the hyper-real nature of the simulation culture, which both reinforced and hampered the uptake of new ideas or change to systems. Thus, the simulation culture influenced how learning through simulation transferred to professional practice, both to support and hinder it ‘While it’s a very false and simulated situation, the emotions are real…you can’t learn it in a book’ (P15, Allied Healthcare Professional).

We previously described how healthcare educators highly valued psychological safety, placing great emphasis on establishing and maintaining it. However, healthcare educators also felt that establishing corresponding robust workplace psychological safety was difficult under the current professional workplace culture: ‘There’s no point teaching the juniors to speak up, if you don’t teach the seniors to listen. Doesn’t matter how brilliant your assertiveness training is, if the first time I try it out you tell me to hum off, it’s not gonna work. So then that reinforces to the juniors that this is the wrong thing to do. And in fact, it’s the right thing to do. It’s just that the seniors aren’t ready to accept that yet’ (P16, Allied Healthcare Professional*). Thus, educators described their explicit approaches to flatten hierarchical structures in support of psychological safety in their simulation microcultures. ‘I say to that [student], I'm doing this [many] years… I'm gonna make five procedural errors minimum per hour. ….Your job is to call me out on those errors—and that sets the tone for the day’ (P18, Doctor*).

Conversely, when students took risks and made judgement calls, educators or senior colleagues needed to be supportive and constructive in their feedback to maintain the working relationship. ‘That senior needs to be able to say, look, that’s a good call but, actually, this is what we do. This is where that information is coming from…You need to be able to back it up… It’s an educational point, not something to damage your fragile ego’ (P18, Doctor*). Also, there was an onus on early career professionals to advise their seniors with respect to professional boundaries ‘if they’re very senior and nobody’s ever told them, you’re really unprofessional the way you interact with people…then they find it hard to believe that there is a problem’ (P14, Doctor).

Simulation culture also perpetuated professional workplace barriers to effective interprofessional and cross-disciplinary collaboration. These barriers included working in silos and looking inwardly, neglecting other professional practices, and creating strict definitions and standardised tools to assess ‘correct’ performance that fostered black and white thinking. In healthcare ‘we are really teaching students in silos, but expecting them to work in lovely horizontally coordinated, integrated teams where understanding your own identity and the identity of others is hugely important’ (P12, Allied Healthcare Professional). This impact was also evident in the legal sector, identified through role-modelling behaviour; ‘they mirror what they see…so that maintains a particular culture’ (P11, Legal Professional).

Discussion

We identified a novel concept, simulation culture, within professional groups that develops due to synergistic interplay between three elements: (a) the educational purpose of SBE in that group that establishes the rationale for simulation, (b) professional values and beliefs that shape educational priorities, and (c) customs and educational techniques for simulation design and implementation. Educational practices in a given profession shape these unique and hyper-real simulation cultures. Simulation culture, in turn, enables some aspects that promote learning, such as techniques to enhance levels of psychological safety (Somerville et al. Citation2023), sometimes absent in workplaces, but also accentuates barriers to learning transfer such as perpetuation of siloed learning and working in uni-professional contexts (See ). Our practice-based approach to culture focuses not just on actions, but also how practices shape individuals and individuals shape practices (Watling et al. Citation2020) in professional microcultures (Bearman et al. Citation2021).

The hyper-real nature of the simulation by itself is not a novel idea. Bligh and Bleakley (Citation2006) critiqued the inauthentic aspects of learning by simulation. Johnston et al. (Citation2020) also raise concerns about the potential hyper-real nature of simulation in their conceptual piece about simulation vs. simulacrum, highlighting how the representation or copy of a reality can become a new reality. Our empirically-derived notion of simulation culture provides a more fine grained understanding of these ideas to meaningfully inform simulation practice. Thus, our findings extend our conceptualisation of how SBE works and under what conditions by adding to a growing body of literature on the importance of learning culture in educational and workplace settings. Simulation educators should be aware of how their unique simulation culture may embed implicit or hidden biases that impact learning. Further, our findings provide key insights into fostering future simulation training for interprofessional and cross-disciplinary groups.

Interprofessional and cross-disciplinary learning and knowledge exchange requires effort. Healthcare adopts an inward-looking approach, often operating in silos (Stalmeijer and Varpio Citation2021). Breaking down these siloes needs effortful collaborative intentionality (Morris and Eppich Citation2021), including diverse professional perspectives early in simulation design. These siloes align with the ‘dominant epistemic doxa’ of HPE researchers, who mostly draw on research from their own fields, creating an insular view, which limits learning from other disciplines (Albert et al. Citation2022 p.153). Our findings illustrate this insular view and potential unintended consequence of simulation cultures especially for uni-professional groups. This siloed approach to education elevates the threshold to generate new ideas or change systems that do not reflect a professional group’s own purposes, values and customs related to SBE. Professional learning culture is highly complex, a perspective missing from the literature to date (Bearman et al. Citation2021). Thus, our findings from each professional sector have important implications for simulation practice: three key questions can shape dialogue around knowledge sharing during collaborative educational design (see Box 1). In our view, this dialogue will strengthen the design and implementation of future interprofessional simulation practice.

Box 1 Three key questions for simulation educators

In addition to the implications for simulation practice, our study has other strengths related to the professional diversity of our participants and our research team. This diversity of perspective during our research process itself exemplifies the collaborative approach we take to our work. We recruited simulation educators across four disparate professions, in higher education institutions covering the north and south of Ireland. Participants described differences in how simulation is both described and enacted, across different contexts, which led to a deeper understanding of their simulation culture. While the research team are all experienced in HPE, three team members were specifically trained in the professions we studied (paramedicine, teacher, and healthcare) providing critical insight into the application of SBE in their previous roles. We reflected on our positionality during research meetings and view our lived experiences as contributing positively to this work. Further work might include observational studies to examine these simulation cultures in the simulated learning environment and workplace setting to determine the transferability of our findings. Admittedly, our work did not include all potential sectors that have integrated SBE approaches. We focused on professions situated in the chain of child safeguarding and future studies will derive additional learnings about SBE design and implementation through comparative analyses between other sectors.

Conclusion

Our findings extend our understanding of learning culture by applying a practice-based approach and contextualising microcultures in SBE. In doing so, we identify a novel concept of simulation culture. Simulation cultures develop both as an expression of educational practices but also as an enabler and barrier of them. Our concept incorporates elements of the hidden curriculum, which influences the transfer for learnings from educational settings to workplaces. The simulation culture concept will provide nuance to the dialogue necessary to facilitate knowledge sharing across professional and disciplinary boundaries.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the participants for their time and expertise, the reviewers for their insightful feedback, along with Professor Marcy Rosenbaum and Professor Margaret Bearman for their informal advice and guidance early in the process. Sincere thanks to the Garda Research Unit for their assistance in recruitment and ethical approval.

Disclosure statement

No conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michelle O’Toole

Michelle O’Toole, BSc, MA, PGDipHPE, is a Teacher Practitioner and Researcher at RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin, Ireland. @mrsot13, https://www.linkedin.com/in/michelle-o-toole-00623319a/

Andrea Doyle

Andrea Doyle, PhD, PGDip MedPhys, PGDip MedEd, BSc(Hons), is a Senior Post-Doctoral Fellow at RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin Ireland. @andreajanedoyle, https://www.linkedin.com/in/andreajanedoyle/

Naoise Collins

Naoise Collins, PhD, is a Lecturer in the Department of Visual and Human Computing in Dundalk Institute of Technology, Dundalk Ireland.

Clare Sullivan

Clare Sullivan, BE MSc, is a Researcher and Senior Simulation Technician at RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin Ireland. @ccsull1, https://www.linkedin.com/in/clarecsullivan/

Claire Mulhall

Claire Mulhall, BA, DMS, PhD, is a Lecturer in Simulation at RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin Ireland. https://ie.linkedin.com/in/clairemulhall

Claire Condron

Claire Condron, BSc, PhD, MBA, is Director of Simulation Education at RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin Ireland. https://www.rcsi.com/people/profile/ccondron

Eva Doherty

Eva Doherty, DClinPsych., CClinPsychol.,(AFPsI), CPsychol(AFBPsS), PFHEA, FEACH., is a Clinical Psychologist, Associate Professor and Director of Human Factors in Patient Safety in the Department of Surgical Affairs, RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences. https://ie.linkedin.com/in/eva-doherty-a3252518

Walter Eppich

Walter Eppich, MD, PhD, FSSH, is Professor of Simulation Education and Research at RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin Ireland. @WalterEppich, https://www.linkedin.com/in/walter-eppich-md-phd-601aba17/

References

- Al-Elq AH. 2010. Simulation-based medical teaching and learning. J Family Community Med. 17(1):35–40. doi:10.4103/1319-1683.68787.

- Albert M, Rowland P, Friesen F, Laberge S. 2022. Barriers to cross-disciplinary knowledge flow: the case of medical education research. Perspect Med Educ. 11(3):149–155. doi:10.1007/s40037-021-00685-6.

- Bearman M, Mahoney P, Tai J, Castanelli D, Watling C. 2021. Invoking culture in medical education research: a critical review and metaphor analysis. Med Educ. 55(8):903–911. doi:10.1111/medu.14464.

- Bearman M, Ajjawi R, O’Donnell M. 2022. Life-on-campus or my-time-and-screen:21 identity and agency in online postgraduate courses. Teach Higher Educ. doi:10.1080/13562517.2022.2109014.

- Bligh J, Bleakley A. 2006. Distributing menus to hungry learners: can learning by simulation become simulation of learning? Med Teach. 28(7):606–613. doi:10.1080/01421590601042335.

- Charmaz K. 2014. Constructing grounded theory. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

- Charmaz K, Thornberg R. 2021. The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qual Res Psychol. 18(3):305–327. doi:10.1080/14780887.2020.1780357.

- Eppich W, et al. 2016. Learning to work together through talk: Continuing professional development in medicine. In Supporting learning across working life: Models, processes and practices.Cham: Springer. p. 47–73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-29019-5.

- Eppich WJ, Olmos-Vega FM, Watling CJ. 2019. Grounded theory methodology: key principles. Healthcare simulation research. Cham: Springer. p. 127–133.

- Eppich W., Gormley G., Teunissen P, et al. 2019. In-depth interviews. In: Nestel D., Hui J., Kunkler Keditors. Healthcare simulation research: a practical guide. Cham: Springer International Publishing; p. 85–91.

- Grossman P, Hammerness K, McDonald M. 2009. Redefining teaching, re-imagining teacher education. Teachers and Teaching: theory and Practice. 15(2):273–289. doi:10.1080/13540600902875340.

- Helmreich RL, Merritt AC. 1998. Culture at work: national, organizational, and professional influences. London: Ashgate.

- Issenberg SB, et al. 2005. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teacher. 27(1):10–28.

- Johnston JL, Kearney GP, Gormley GJ, Reid H. 2020. Into the uncanny valley: simulation versus simulacrum? Med Educ. 54(10):903–907. doi:10.1111/medu.14184.

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. 2000. To err is human. Build Safer Health Syst. 9:0–309. www.nap.edu/readingroom.

- Lave J, Wenger E. 1991. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Morris M, Eppich WJ. 2021. Changing workplace-based education norms through “collaborative intentionality. Med Educ. 55(8):885–887. doi:10.1111/medu.14564.

- Motola I, Devine LA, Chung HS, Sullivan JE, Issenberg SB. 2013. Simulation in healthcare education: a best evidence practical guide. AMEE Guide No. 82. Med Teach. 35(10):e1511–e1530. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.818632.

- Mulder H, Ter Braak E, Chen HC, Ten Cate O. 2019. Addressing the hidden curriculum in the clinical workplace: A practical tool for trainees and faculty. Med Teach. 41(1):36–43. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1436760.

- Nestel D, Mobley BL, Hunt EA, Eppich WJ. 2014. Confederates in health care simulations: not as simple as it seems. Clin Simul Nurs. 10(12):611–616. doi:10.1016/j.ecns.2014.09.007.

- Purdy E, Alexander C, Caughley M, Bassett S, Brazil V. 2019. Identifying and transmitting the culture of emergency medicine through simulation. AEM Educ Train. 3(2):118–128. doi:10.1002/aet2.10325.

- Somerville SG, Harrison NM, Lewis SA. 2023. Twelve tips for the pre-brief to promote psychological safety in simulation-based education. Med Teach. 45(12):1349–1356. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2023.2214305.

- Stalmeijer RE, Varpio L. 2021. The wolf you feed: challenging intraprofessional workplace-based education norms. Med Educ. 55(8):894–902. doi:10.1111/medu.14520.

- Strevens, C., Grimes, R., & Phillips, E, editors. 2014. Legal education: simulation in theory and practice. 1st ed. London. Routledge.

- Varpio L, Ajjawi R, Monrouxe LV, O'Brien BC, Rees CE. 2017. Shedding the cobra effect: problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Med Educ. 51(1):40–50. doi:10.1111/medu.13124.

- Vygotsky LS. 1978. Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Watling C, Driessen E, van der Vleuten CPM, Vanstone M, Lingard L. 2013. Music lessons: revealing medicine’s learning culture through comparison with that of music. Med Educ. 47(8):842–850. doi:10.1111/medu.12235.

- Watling C. 2015. When I say … learning culture. Med Educ. 49(6):556–557. doi:10.1111/medu.12657.

- Watling CJ, Ajjawi R, Bearman M. 2020. Approaching culture in medical education: three perspectives. Med Educ. 54(4):289–295. doi:10.1111/medu.14037.

- Watling CJ, Lingard L. 2012. Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. Med Teach. 34(10):850–861. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.704439.

- Wenger E. 1998. Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press