Abstract

Background

The medical education system in mainland China faces numerous challenges and the lack of learner-centered approaches may contribute to passive learning and reduced student engagement. While problem-based learning (PBL) is common in Western medical schools, its feasibility in China is questioned due to cultural differences. This systematic review aims to summarize the application of PBL in medical education in mainland China based on existing literature, as well as to identify the challenges and opportunities encountered in its implementation.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted using electronic databases, including MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science, Wan fang and CNKI databases. Grey literature sources were explored using Google Scholar. The search was limited to articles that include at least one English abstract up to May 1st, 2023. The inclusion criteria were studies that reported the use of PBL in medical education in mainland China.

Results

A total of 21 articles were included in the final analysis. The findings indicate that PBL is a well-adopted and effective learning method in most medical education, especially for developing critical thinking, problem-solving, and teamwork skills. However, the application of PBL in mainland China is limited due to various challenges, including faculty resistance, inadequate resources and cultural barriers. To effectively address these challenges, it is essential to provide faculty training, develop appropriate assessment methods to evaluate student progress within the PBL framework and create conducive spaces and resources that support collaborative learning and critical thinking.

Conclusion

The utilization of PBL in mainland China holds potential for enhancing medical education. However, its successful implementation requires significant efforts to address the identified challenges. It is crucial to engage stakeholders in a collaborative effort to promote the application of PBL and ultimately improve the quality of medical education in mainland China.

1. Introduction

For a long period of time, the Chinese medical education system was relied on apprenticeship and family heritage. In the early nineteenth century, Western medicine was introduced to China, and in 1866, the first westernized medical school was founded in Guangzhou [Citation1], which inevitably changed the Chinese medical education system. In the following years, there was a rise in the popularity of primary and secondary medical schools, as well as tertiary institutions, across China [Citation2]. The curricula and teaching methods have been primarily based on the traditional Western model, which is typically a teacher-centered, discipline-specific, lecture-based approach, where the progress of learning is examination-driven [Citation3]. Problem-based learning (PBL) represents a shift away from the traditional lecture-based didactic approach towards a student-centered approach. This approach is theorized to foster a constructive attitude towards learning for students, creating frameworks to organize and retrieve appropriate information [Citation4].

PBL has rapidly expanded in mainland China’s medical colleges. The 7th Asia-Pacific Problem-Based Learning Conference in Shenyang (2008), hosted by China Medical University, with its theme of 'The Internationalization and Localization of PBL, and the establishment of the Chinese PBL Education Alliance (2015) have been instrumental in promoting this model. In 2018, the third Chinese Health and Medical Education PBL Alliance Conference in Shanghai, attended by international experts and representatives from over 30 Chinese medical institutions, signified the standardization of PBL in Chinese medical education. The innovative combination of simulation teaching and PBL is expected to drive medical education reform and improve teaching quality and standards in China

1.1. Challenges and social backgrounds of medical education innovation in mainland China

Mainland China is home to approximately one-fifth of the world’s population [Citation5]. The aging population has increased the demand for healthcare services [Citation6]. According to The World Directory of Medical Schools, a website that lists all medical schools worldwide and provides accurate, up-to-date, and comprehensive information for each institution, China has 191 medical colleges and universities as of 2023. Despite a balanced supply and demand for doctors during the ‘14th Five-Year Plan’ period [Citation7], challenges remain in attracting and retaining medical talent [Citation8].

The 21st-century information explosion has expanded medical education content, yet credit hours for courses are diminishing [Citation9]. This necessitates skills in self-directed and lifelong learning for students. Historically, China’s One-Child Policy and cultural traditions influenced perceptions of compassion, impacting medical education [Citation10]. Additionally, there’s a tendency among medical students to overlook humanistic education [Citation10].

Most modern medical instructors are clinicians sharing their own learning experiences, but the novelty of PBL presents challenges as some clinicians are not fully acquainted with it. High computer ownership reflects socio-economic and technological development [Citation11]. At Tongji Medical College, computer ownership among students increased from 66% in 2000 to nearly 100% by 2012 [Citation12]. Emerging technologies like ChatGPT are being integrated into PBL, creating opportunities for innovative medical education in China [Citation13], thus preparing students for a knowledge-based global economy [Citation14].

1.2. PBL in mainland China

PBL is a student-centered pedagogy that was pioneered in the medical school program at McMaster University in the late 1960s by Howard Barrows and his colleagues [Citation15]. Since then, it has gained popularity worldwide in the field of medical education. PBL has been advocated as a means of increasing student involvement and retention, as well as the capacity to apply knowledge and skills gained in tertiary education programs [Citation16]. In mainland China, PBL was first introduced for medical education in 1956 by Shanghai Second Medical University and Xi’an Medical University [Citation17]. The concept of PBL was further accelerated in mainland China through the ‘Medical Education Innovation: Hong Kong’s Experience’ symposium held in 2000 at the Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong. The conference hosted the presidents of most of mainland China’s medical colleges, who brought back the conception of PBL and contributed to its development in medical education. However, despite the widespread adoption of PBL, questions regarding its feasibility, applicability, practicality, and benefits remain unanswered.

In Tongji Medical College, we first adopted PBL in medical undergraduates from the Seven-Year Medicine Programme as a small-scale randomized controlled trial in 2004 [Citation12]. As PBL gained popularity, it was expanded to undergraduates from the Five-, Seven-, and Eight-Year Medicine Programmes [Citation18]. In 2006, Tongji constructed a PBL teaching building with 20 modernized classrooms. Our efforts in implementing PBL were recognized with two favorable academic awards: the Teaching Achievement Award of Hubei Province and the National Teaching Achievement Award. A survey conducted among students who received PBL showed that more than 85% of them demonstrated significant improvement in their self-learning and analytical skills (‘Practice and exploration of problem-based learning methods in Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology,’ 2008). However, 74% of the PBL instructors indicated that further improvements are needed in our PBL courses.

However, despite recent reviews on PBL in non-Western contexts, such as those in Southeast Asia or Latin America [Citation19], the synthesis of studies highlights that the PBL experiences of students and teachers are intricately tied to their mutual commitment to the approach and the level of institutional support in these regions. It is worth noting that while there are systematic reviews addressing the implementation and effectiveness of PBL in mainland China, they are not published in English, making them less accessible to a global readership. Given the unique cultural and educational context in China, it is crucial to understand how PBL is applied in this setting and evaluate its effectiveness. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to address this gap by summarizing and synthesizing the existing literature on the use of PBL in mainland China.

The systematic review is guided by the following questions:

What are the current applications of PBL in medical education in mainland China?

How effective is PBL in improving learning outcomes in medical education?

What are the challenges faced in implementing PBL in undergraduate medical programs in mainland China?

By answering these questions, the systematic review aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current state of PBL in mainland China and identify areas for improvement and further research.

2. Methods

2.1. Sources and search strategies

We conducted online searches of four traditional medical databases: MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and Web of Science. We also included two non-traditional databases, Wan fang and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), which feature many Chinese journals not indexed by the traditional databases. The searches were limited to articles that include at least one English abstract and were conducted from April 2023 to December 2023. Typically, journals indexed in Chinese core databases require papers to have English abstracts. Additionally, we reviewed the reference lists of the retrieved papers and utilized Google Scholar to explore grey literature sources. We also consulted experts in the field. The search terms used were ‘problem-based learning’ or ‘self-directed learning’ or ‘inquiry learning,’ cross-referenced against ‘medical education,’ with the author address restricted to ‘China’.

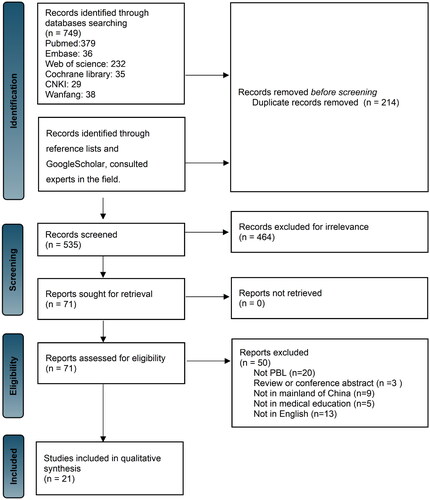

A total of 21 articles that met the defined inclusion criteria were included in the systematic analysis. provides a flowchart summarizing the systematic review process, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The Supplementary Table provides details of the 21 articles included in the synthesis. The evaluation included data from over 50,000 students and instructors in mainland China, covering various types of PBL courses, including anatomy, ophthalmology, and dentistry.

2.2. Selection of studies for inclusion

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Studies published with at least an English abstract; (2) Studies conducted in mainland China; (3) Studies focused on PBL as a learning method, including hybrid and web-based PBL; (4) Studies involving medical students include nursing students.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Systematic reviews, conference abstracts, and books; (2) Due to differences in degree conferment, education duration, and curriculum design between mainland China and Hong Kong, Taiwan, or other countries [Citation20], we chose not to include them in our considerations.

2.3. Quality assessment

This study employed a two-reviewer approach for article screening. The reviewers independently screened all articles identified through electronic searches. Irrelevant articles were discarded based on their titles. The abstracts of potentially relevant articles were then screened for relevance to the study design and reported intervention. Articles that met the inclusion criteria were read in full. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers and consultation with a supervisor to reach a consensus.

The included studies underwent quality assessment using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies, which was developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP). This tool is recognized as suitable for systematic reviews of effectiveness and can evaluate various intervention designs, including randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies, and uncontrolled studies [Citation21]. The EPHPP tool, developed by the Canadian Effective Public Health Practice Project, is commonly used in the fields of health promotion and public health interventions. The results of previous studies indicate that the tool demonstrates content validity, structural validity, and robust inter-rater reliability [Citation22–24]. The tool consists of six criteria: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection method, and withdrawals/dropouts. Each criterion is rated as strong, moderate, or weak. The overall assessment of a study is determined by evaluating these ratings. Studies with no weak rating and four strong ratings are classified as ‘strong,’ those with fewer than four strong ratings and one weak rating are classified as ‘moderate,’ and those with two or more weak ratings are classified as ‘weak’. The quality assessment of the included studies was performed independently by two reviewers, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus with a supervisor.

Additionally, conducting a meta-analysis was deemed inappropriate due to the observed heterogeneity across the included studies in terms of design, intervention type, study population, and outcome variables.

3. Results

3.1. Selected studies and their characteristics

As shown in , we identified 749 records from the MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science, Wan fang, and CNKI databases. The results involve more than 300 medical educational institutions in China. These papers discuss various aspects of PBL, including its conception, theory, philosophy, principle, approach, effectiveness, evaluation, cases, tutoring techniques, and application issues. Specifically, PBL has been implemented in almost all courses of medical education in mainland China. This includes 31 different disciplines of Basic Medicine such as Histology and Embryology, Physiology, Pathology, Pharmacology, Biology, Anatomy, Immunology, Epidemiology, and more. It also includes 15 different disciplines of Clinical Medicine such as Stomatology, Surgery, Internal Medicine, Docimasiology, Ophthalmology, Otorhinolaryngology, and more. Additionally, PBL has been applied in Chinese traditional medicine and nursing.

Through a rigorous process of screening for duplicates and irrelevant studies based on their titles and abstracts, we identified 71 articles that required further analysis of the full text to identify relevant data. After excluding an additional 50 articles, we finally included 21 studies in this systematic review. presents the characteristics of these studies, with nine of them assessing the effectiveness of PBL in a single course context [Citation25, Citation27, Citation30, Citation33, Citation34, Citation38, Citation40, Citation43, Citation45]. Among these nine studies, seven employed a randomized controlled trial design, while the remaining study did not randomize participants [Citation25, Citation27, Citation30, Citation32–34, Citation38, Citation40, Citation45]. provides a summary of the evaluation tools, outcome variables, results, and quality assessment of these nine studies. Additionally, twelve studies have been conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of PBL at the whole curriculum level [Citation26, Citation28, Citation29, Citation31, Citation32, Citation35–37, Citation39, Citation41, Citation42, Citation44]. Ten of these studies used randomized controlled trial designs to compare PBL with lecture-based approaches [Citation26, Citation28, Citation29, Citation32, Citation35, Citation37, Citation39, Citation41, Citation42, Citation44]. Ten of these studies used randomized controlled trial designs to compare PBL with lecture-based approaches, while one non-randomized study only included a PBL group [Citation31, Citation36]. presents the evaluation tools, outcome variables, results, and quality assessment of the studies evaluating the effectiveness of PBL at the whole curriculum level.

Table 1. Main characteristics extracted from the included 21 studies.

Table 2. Summary of outcome variables, results, and quality assessment of included studies (single course intervention).

Table 3. Summary of outcome variables, results, and quality assessment of included studies (whole course intervention).

3.2. Current PBL applications

3.2.1. Traditional PBL

In mainland China’s medical education, traditional PBL courses aim to develop students’ critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaboration skills, preparing them for medical practice complexities [Citation46]. PBL sessions typically begin with a patient case, guiding students to identify knowledge gaps and set learning objectives. Students then self-study assigned tasks, followed by group discussions to foster cooperation and communication. A facilitator guides these discussions, focusing on stimulating critical thinking. Students address knowledge gaps through independent research, and the session concludes with group presentations and feedback, promoting continuous educational growth.

The implementation of PBL in curricula varied among different schools in mainland China. PBL was either applied to single-subject learning or the overall application of PBL in the course [Citation47]. Additionally, PBL typically encompasses various types of cases to address different aspects of medical practice. These cases may include current medical history, personal history or complex medical issues, aimed at exposing students to a range of situations they may encounter in their future medical careers. The cases often integrate basic and clinical sciences, encouraging students to apply theoretical knowledge to real-life situations. PBL typically encompassed various types of cases to address different aspects of medical practice. These cases included clinical scenarios, or complex medical issues, aimed at exposing students to a range of situations they might encounter in their future. The cases often required students to apply theoretical knowledge to real-life situations, promoting the integration of basic and clinical sciences.

However, in some courses, the design of cases was not aimed at conveying a specific diagnosis but rather at presenting complex situations to trigger sequential issues, guiding students to think critically. For instance, in the context of ophthalmology, a case involved a patient with hypertension and eye hemorrhage, but without significant impairment of vision, creating a complex scenario for discussion [Citation44]. Another study indicated that the positive impact on student self-assessment scores was greater when common diseases with typical symptoms were interspersed with cases featuring atypical symptoms and scenarios involving rare diseases [Citation25].

3.2.2. Hybrid models

Integrating PBL with other indtructional methods, such as simulation education, or didactic lectures, has shown promise in fostering a comprehensive educational experience. For instance, incorporating simulation sessions within PBL sessions provided students with practical, hands-on experiences, bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. In one study, the virtual simulation was a practical approach in which students assumed roles to simulate specific work scenarios. In one study, the PBL learning group comprised three to four teachers with extensive clinical experience and high proficiency [Citation28]. The teachers established PBL learning objectives to ensure students’ comprehension of pediatric patients’ characteristics, clinical symptoms, foundational knowledge, and the dosage and methods of common pediatric drugs. Each student received an admission goal document, with teachers addressing common student challenges, consolidating specialized knowledge, and enhancing operational skills. Ultimately, the integration of PBL learning with virtual simulation effectively enhances students’ academic performance, proficiency in pediatric knowledge, self assessment of comprehensive abilities, and overall learning satisfaction.

Combining PBL with didactic lectures offered a balanced approach that allowed students to acquire foundational information through lectures and then apply and reinforce that knowledge in PBL scenarios. Lian et al. found that the hybrid-PBL course demonstrated increased attraction for students, with participants expressing a more positive attitude towards additional study time compared with traditional lectures [Citation39]. Relying solely on cased-based lectures (CBL) could lead students to lose interest in learning. In recent years, various new learning methods have emerged aimed at stimulating students’ interest in learning and enhancing their problem-solving and innovative thinking abilities, starting from authentic clinical problems. Combining PBL with other learning methods supplements traditional teaching models and shows promising application prospects.

3.2.3. Online PBL

The emergence of the Internet education model has led to the rise of online PBL, marking a significant shift from traditional formats. Online PBL harnesses the power of digital platforms to facilitate collaborative learning experiences. One key distinction is the virtual nature of the cases and discussions, allowing participants to engage remotely and transcending geographical constraints. In online PBL, students often access cases and relevant materials through online platforms, enabling asynchronous participation and flexibility in learning schedules. Virtual discussions, facilitated through forums or video conferencing tools, replaced face-to-face interactions. This shift allowed students from various locations and backgrounds to actively contribute, leading to better results for written examination, clinical examination, and overall performance of pediatric knowledge [Citation28]. Moreover, the use of multimedia elements, interactive simulations, and virtual patient encounters in online PBL enhanced the richness of the learning experience. These digital tools enabled a more dynamic exploration of cases, providing students with immersive and engaging scenarios that may not be feasible in traditional settings, ultimately enhancing overall student performance [Citation40].

However, challenges such as technological barriers, the need for effective online communication, and the potential for reduced social interaction must be considered in the transition to online PBL. Striking a balance between leveraging digital innovations and preserving the collaborative essence of PBL is crucial for the success of online formats in delivering effective and engaging educational experiences.

3.3. Effectiveness of PBL

3.3.1. Student satisfaction

In recent years, numerous studies have highlighted the efficacy of PBL in enhancing student engagement, fostering critical thinking, and bolstering learning autonomy. Specifically, findings from this systematic review indicated a positive impact of PBL on students’ learning initiative, motivation, and interest. The cases presented in PBL sessions, characterized by novelty and real-world relevance, stimulate students’ curiosity and active participation in the learning process. Experimental groups employing PBL demonstrated greater motivation, planning, implementation, and self-monitoring compared to those exposed to traditional lecture-based courses [Citation32]. Furthermore, the integration of PBL into anatomy learning was associated with increased student interest, study efficiency, and the development of independent learning capabilities. PBL proved superior to conventional study methods in enhancing students’ interest, influencing their learning approach, and activating enthusiasm when compared to LBL methods [Citation40, Citation41]. Additionally, teachers reported that residents in the PBL group exhibited improved pre-operative preparedness and greater enthusiasm during the practice process [Citation45].

3.3.2. Learning outcomes

Summarizing research consistently indicates that PBL positively impacts various measurable outcomes, including academic performance and skills acquisition. Studies have demonstrated that students engaged in PBL exhibit enhanced academic performance, showcasing improved understanding and application of subject matter. Moreover, PBL had been associated with increased knowledge retention, highlighting its efficacy in facilitating long-term learning. Specifically, PBL with rare disease case scenarios promoted the integration of knowledge, improved critical thinking abilities, and enhanced the ability to collect, reorganize, and analyze information [Citation25]. Under the PBL learning mode, medical students’ theoretical knowledge and clinical operation skills improved by 13%, and there was relative improvements in autonomous learning ability, communication ability, and creative thinking ability [Citation26]. PBL also developed students’ learning autonomy, emphasizes self-guidance, and stimulates the desire for knowledge [Citation27]. Academic performance, including theoretical knowledge, practical skills, and case analysis, was considerably higher in the PBL study group than in the control group [Citation28]. Students in PBL actively and critically learn, referencing substantial evidence and employing innovative thinking. Compared to the control group, those in the PBL group had significantly higher mean theory test scores, student feedback scores, and clinical performance scores [Citation30, Citation32]. PBL also enhanced analytical and problem-solving skills and promotes self-directed learning. The hybrid-PBL group, which combines PBL and didactic lectures, showed significantly higher scores on short-essay questions and case-analysis questions. In conclusion, PBL improved problem analysis, enhances independent study abilities, comprehensive analysis, and learning efficiency, and performs well in clinical skill tests, especially for ‘case analysis’[Citation42]. Furthermore, PBL played a beneficial role in regional anatomy education, with higher written examination scores in the PBL group [Citation44].

3.3.3. Long-term benefits

PBL has the potential for a long-term impact on enhancing problem-solving abilities and learner progression by improving skills such as communication and collaboration [Citation43]. It is widely recognized as a highly effective learning method across various disciplines, particularly in anatomy education. PBL promoted active student engagement, enhances communication and collaboration skills within groups, and emphasizes teamwork, participation, and leveraging prior knowledge in small-group settings. Numerous studies have consistently demonstrated the multifaceted benefits of the PBL learning mode. It not only enhanced teamwork but also cultivated comprehensive thinking, language organization, logical reasoning, self-learning abilities, communication skills, and team cooperation skills among students [Citation25]. Furthermore, the enduring impact of PBL extends beyond the academic realm into the professional landscape. Graduates from PBL groups highly valued communication skills and express confidence in effectively communicating with professionals and colleagues, contributing to their professional success [Citation26]. The experience with PBL instilled an increased appreciation for team consciousness and humanistic knowledge, shaping well-rounded individuals with a holistic approach to problem-solving [Citation30]. This aligned with the continuous emphasis on student engagement and the application of prior knowledge within the collaborative and interactive small-group settings characteristic of PBL [Citation29].

In addition, the cultivation of critical thinking disposition emerges as a key long-term benefit of PBL. Studies have established a positive correlation between students’ critical thinking dispositions and their performance in the PBL process, with those possessing enhanced critical thinking demonstrating superior outcomes [Citation38]. Notably, open-mindedness within the critical thinking disposition emerges as a primary factor determining improvement in the preparation dimensions of the PBL process, particularly in fostering open-mindedness and inquisitiveness [Citation29]. In essence, the enduring impact of PBL transcends academic boundaries, shaping students into adept, collaborative thinkers equipped with the essential skills and dispositions necessary for success in both their academic and professional journeys.

Overall, the amalgamation of evidence supports PBL not only as a pedagogical tool for immediate academic gains but also as a catalyst for long-term cognitive development and a positive learning experience.

3.4. The challenges of implementing PBL in mainland China

3.4.1. Resource constraints

While PBL introduces a dynamic educational approach, it is not without its share of challenges, specifically revolving around faculty requirements, classroom space, and learning materials. The implementation of PBL presents notable hurdles, demanding a substantial investment of time, funding, and labor. Some studies have suggested that traditional didactic methods might be more efficient in delivering critical information within a shorter timeframe [Citation33]. Additionally, PBL necessitated collaboration among different departments and the effective utilization of resources within educational institutions [Citation35]. Nevertheless, Zhang et al. argued that the extended study time in PBL can be viewed as ‘active learning,’ given the corresponding improvement in study interest [Citation42]. Despite these advantages, Rui et al. discovered that PBL could result in fragmented and superficial knowledge acquisition, along with an increased academic burden [Citation37]. Furthermore, their study indicated that the time commitment for PBL was approximately three times more than that required for traditional learning methods [Citation37].

Besides, the implementation of PBL requires teachers to possess a range of skills and qualities. According to Du et al. teachers needed to pay attention to their own quality culture as PBL places high demands on their learning skills [Citation35]. In addition, Rui et al. suggested that PBL learning required teachers with extensive interdisciplinary knowledge, strong leadership and communication skills, and the ability to learn and replenish a large amount of subject-specific knowledge [Citation37]. Wang et al. emphasized that successful PBL also requires instructors who were knowledgeable in multiple disciplines and were able to direct students to appropriate presentation topics and methods [Citation43]. Thus, teachers who use the PBL method must be knowledgeable, responsible, and trained in multidimensional approaches to the curricular topics.

3.4.2. Cultural barriers

Implementing PBL in cultural contexts, such as mainland China, brings forth unique challenges related to communication styles and the promotion of self-directed learning. Addressing these cultural nuances is pivotal for successful PBL adoption. The reserved nature of Chinese communication styles may impede the essential open dialogue and spontaneous interaction required by PBL, leading students to experience psychological burdens and difficulties in adaptation. Students might find PBL unfamiliar and time-consuming, and they might experience stress, an increased workload, and a lack of confidence during the initial states of implementation [Citation27, Citation38]. Furthermore, some students might struggle to adjust to the self-directed learning style of PBL and might find the learning process fragmentary and lacking in systematic structure, which could increase the already heavy academic burden on medical students [Citation35]. Traditional Chinese educational values often emphasized authority figures, potentially discouraging self-directed learning. Thus, even students who expressed interest in PBL may not be accustomed to the self-education process and may find it too time-consuming [Citation44]. Xu et al. found that students in the experimental group had a certain degree of rejection to the difficulty of adapting to the PBL than students in the control group with traditional learning methods [Citation26]. These findings suggest that the application of PBL in medical education programs in mainland China may be limited, and further research is needed to explore ways to improve its implementation.

3.4.3. Inadequate assessment framework

Assessing PBL presents distinct challenges that arise from the limitations of traditional assessment methods. As a self-directed learning method, the learning outcomes of PBL evaluation systems should not only focus on the acquisition of knowledge and skills among students. PBL's emphasis on holistic skill development requires assessments that go beyond traditional metrics. Incorporating assessments that gauge critical thinking, problem-solving, communication, and teamwork ensures a more accurate representation of PBL outcomes. Several studies have raised concerns about the effectiveness of PBL as a standalone learning method [Citation30, Citation37]. Li et al. recommended establishing a systematic and standardized evaluation system to assess the effects of alternative learning methods. Rui et al. suggested that the PBL learning method requires a combination of self-assessment, mutual assessment, and the teacher’s evaluation of various nondominant qualities through knowledge point examination to develop a mature, applicable scientific evaluation system. These studies highlighted the need for improved evaluation methods to accurately assess the impact of PBL in medical education programs in mainland China.

4. Discussion

In this study, we examined three main aspects of PBL in undergraduate medical education in mainland China. Firstly, we explored the current applications of PBL, including traditional approaches, hybrid models, and online PBL. Secondly, we investigated the effectiveness of PBL, looking at its impact on student satisfaction, learning outcomes, and long-term cognitive development. Lastly, we examined the challenges of implementing PBL in undergraduate medical programs, such as resource constraints, cultural barriers, and assessment limitations. These interconnected focal points offer valuable insights to improve the utilization of PBL by providing a comprehensive understand of PBL in the unique context of medical education in mainland China.

4.1. The unresolved problems in the application of PBL in mainland China

The positive outcomes associated with PBL, particularly its impact on long-term cognitive development and holistic learning, highlight its value in medical education. To address the challenges, a paradigm shift in assessment methodologies is crucial. Implementing comprehensive evaluation systems that encompass diverse skills ensures a nuanced understanding of the educational impact of PBL. Striking a balance between traditional and innovative learning methods, such as hybrid models, can enhance engagement and effectiveness. However, contrary to previous research, we identified a greater number of challenges and issues.

There are still unresolved application issues for both tutors and students when it comes to adapting to this resource-intensive pedagogy. For tutors, there are several difficulties: (1) PBL requires group discussions with 6–7 people, which is different from the traditional model with 30 students in a class. This demands an increased faculty capacity to ensure the quality of learning. However, there is a shortage of tutors with the necessary professional skills and rich medical knowledge in domestic medical schools; (2) Character-shifting difficulties and inexperience contribute to major problems, as tutors tend to lead the learning process and may be impatient with less excellent students, even criticizing them for their disadvantages. This can lead to negative emotions and resistance from these students; and (3) Mentors have misunderstood the concept of self-directed learning, wrongly perceiving PBL as a tutor-free process. As a result, they may show inadequate preparation and attentiveness towards PBL curricula. These behaviors can diminish students’ positive motivation for PBL and decrease its effectiveness. These behaviors usually diminish students’ positive motivation for PBL and decrease its effectiveness. For students, there are several challenges: (1) PBL tutorials require open discussions, which may conflict with the more reserved Chinese communication style characterized as ‘unwilling to speak, not expressing as much as is known or felt’ [Citation48]; (2) Different students have varying levels of preference for PBL. While students with a high level of preference enjoy and benefit from PBL, those with a low level of preference may completely reject it; and (3) PBL emphasizes self-learning ability to some extent. However, students are often unwilling to participate due to their fear of complications and their perception of PBL as a ‘time-killer,’ despite criticizing the drawbacks of traditional medical curriculum. Therefore, the issues faced by students can be attributed to unclear learning objectives and a lack of motivation.

Furthermore, there are problems related to limited study resources, lack of teaching materials, and inadequate classrooms. These issues can be addressed through the modernization of science, progress in information technology, and the creation of web-based PBL platforms. Lastly, the assessment system for PBL is not comprehensive. To address this, we can change traditional assessment methods and encourage students to prioritize problem-solving and self-directed learning. By doing so, we must assess students’ learning performance more comprehensively and objectively, considering various aspects beyond mere reliance on scores.

4.2. The direction of PBL development in mainland China

The findings of this study have significant implications for the field of medical education. While PBL is gradually being adopted globally, there is a need for specific efforts to improve its effectiveness in mainland China, as some students lack motivation and some tutors experience a lack of interest, similar to other Asian countries. There is even debate among educators about whether PBL is suitable for Asian students, suggesting that Asian students may not be well-suited for PBL [Citation49].

For educators in mainland China, several questions need to be addressed: (1) Does China need a major shift in the medical educational paradigm? (2) Does China need PBL? (3) What factors contribute to the ineffectiveness of PBL curricula in mainland China? (4) Are there any educational methods that may be more suitable for China than PBL? (5) How can we learn from advanced foreign teaching experiences? It is clear that a major paradigm shift in medical education is necessary for students to meet the demands of the ‘knowledge big bang’ in this century. PBL represents a student-centered learning paradigm that has demonstrated significant efficiency globally. The fluctuating availability of PBL in mainland China may be attributed to the country’s history of examination-oriented education, passive acceptance of learning, unclear learning objectives, a lack of student motivation, and the relatively reserved Chinese communication culture.

When interpreting the literature on the effectiveness of PBL, it is important to consider the level of implementation of this intervention. Our review identified nine studies that evaluated the effectiveness of PBL in a single course context, most of which reported positive results for the PBL intervention. This finding is consistent with the results of a systematic review by Bassir et al. which investigated the effectiveness of PBL in dental education and found that a single PBL intervention in a traditional curriculum almost supported the effectiveness of PBL intervention [Citation47]. Evaluating PBL at the level of a single course may also allow for a more targeted assessment of specific learning outcomes, as well as a better understanding of the potential challenges and benefits of PBL implementation in a particular topic or subject area. Furthermore, twelve studies included in our review evaluated the effectiveness of PBL at the whole curriculum level, with most comparing PBL to traditional LBL and finding PBL to be beneficial. However, a recent cross-sectional study revealed that the overall quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on PBL learning in medical education was not satisfactory [Citation50]. Therefore, editors and peer reviewers are encouraged to engage in a more rigorous assessment of pertinent RCTs compared to the current standards.

Moreover, this study has theoretical implications that extend to existing frameworks in medical education. The challenges identified shed light on the intricate interplay between cultural factors, resource limitations, and pedagogical methods. This study contributes to a nuanced understanding of how cultural nuances impact the implementation of educational models, providing theoretical insights into the intersection of learning methodologies and cultural contexts. The identified challenges challenge traditional perspectives on the universality of educational approaches, emphasizing the importance of considering context-specific factors in designing effective medical education programs.

4.3. Unlocking the significance of PBL for global students

Observations indicate that although PBL was introduced relatively late in China, research on its adaptation remains limited [Citation51]. Both domestic and international PBL models in medical education commonly use classic clinical cases and emphasize collaborative and self-directed learning. However, there are notable differences in research focus and PBL development between China and other countries. Mainland China primarily concentrates on confirming PBL's implementation procedures and promoting its application in medical education, while foreign contexts are focused on innovation and extending PBL's influence [Citation52].

Our findings align with recent Chinese-language systematic reviews, indicating PBL's advantages over LBL in enhancing medical students’ knowledge and satisfaction with learning [Citation53–55]. However, challenges accompany PBL implementation in China, including a lack of qualified instructors, insufficient resources, and difficulties in adapting to large student numbers [Citation56]. Inadequate evaluation systems for PBL also pose challenges [Citation57].

Finally, we have summarized potential learning materials or online tools that may aid PBL, allowing accessibility and utilization across different cultures. In China, innovative teaching tools such as the ‘WeChat’, ‘MOOCs’, ‘Chaoxing’, the ‘flipped classroom’, and ‘scenario simulation’ have demonstrated unique advantages when combined with PBL in both classroom teaching and residency training. The use of the WeChat platform in residency-assisted teaching improves teacher-student evaluation modes, enhancing the overall quality of teaching assessments. The flipped classroom, emphasizing ‘learning before teaching’ through digital platforms, fosters self-directed learning, improving students’ clinical thinking, teamwork, and emergency response capabilities. Scenario simulation, which replicates real working situations, contributes significantly to skill mastery, overall student qualities, critical thinking, and learning satisfaction. Mind maps are also widely used by students as learning and analytical tools, facilitating both horizontal and vertical thinking [Citation58]. Nowadays, there are computer-based mind-mapping software options such as MindManager, Mindmap, as well as online tools like PersonalBrain and XMind that make it convenient to create mind maps, enhancing both teaching and learning efficiency. Additionally, research has explored professionally developed online diagramming tools and sharing platforms, such as Process on, which have been successfully integrated into PBL in the learning of emergency medicine research in mainland China [Citation59]. This integration has proven to help emergency medicine graduate students more easily grasp professional knowledge.

5. Conclusions and future perspective

The literature on the effectiveness of PBL in medical education presents mixed findings. This systematic review highlights the varying evidence regarding the effectiveness of PBL in medical education. However, it is important to transparently acknowledge the limitations in this study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of this review may limit the generalizability of the research results, such as the exclusion of literature from regions like Taiwan and China. Nonetheless, this approach serves the purpose of conducting a cross-cultural study on PBL. Additionally, the assessment criteria in the article, apart from academic performance and practical examination scores, are predominantly subjective, which may introduce bias. Furthermore, a quality assessment was conducted using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies developed by the EPHPP. It should be noted that excluding qualitative data may limit insights into the successful implementation of PBL in different contexts. However, among the assessment criteria included in the literature, besides objective indicators such as scores, the majority consist of subjective evaluations like student and teacher satisfaction, making qualitative assessment challenging.

For future research, it is crucial to consider several avenues that can enhance our understanding of PBL in medical education. Firstly, future studies could delve into cross-cultural analyses, encompassing diverse regions like Taiwan and China, to offer a more globally informed perspective on the effectiveness of PBL. Additionally, there is a need for the development and exploration of objective assessment measures, mitigating subjectivity in evaluating PBL outcomes. Longitudinal studies can provide insights into the lasting impact of PBL on critical skills, while investigations into hybrid models and their optimal combinations may further refine learning methodologies. Finally, research addressing cultural adaptation strategies can contribute to overcoming communication barriers in PBL implementation. These avenues collectively aim to enrich our comprehension of PBL's effectiveness, fostering improvements in medical education practices.

In summary, PBL serves as a more holistic and quality education to motivate student learning in the modern medical professions. PBL has been demonstrated to successfully shape ‘competent, caring, and ethical healthcare’ professionals by instilling desired ‘habits of mind, behavior, and action’. Currently, individuals who have recently graduated from college face challenges in accessing job opportunities due to their lack of experience and still-developing abilities. Compared with traditional graduates, PBL students have certain advantages in professional ethics, professional ability, humanitarian spirit, individual psychological quality, and lifelong learning ability. PBL enables medical students to successfully transition to the role of a doctor and effectively navigate the complex and ever-changing medical field, thereby strengthening the pool of candidates fit for employment [Citation47]. PBL can make curriculum content relevant to practical contexts by building learning around clinical, community, or scientific problems. It focuses on core information that is relevant to real scenarios, reducing information overload. Additionally, PBL fosters the development of valuable transferable skills, such as leadership, teamwork, communication, and problem-learning, which are useful throughout lifelong learning [Citation50]. However, further research is needed to understand the theoretical concepts underlying PBL and to gain a clearer understanding of how PBL works or does not work under different circumstances. It is also important to bridge the gap between theory and practice and expand knowledge on developing and improving PBL in everyday educational settings.

To effectively implement PBL and fully grasp the concept of the PBL process, we recommend that mainland Chinese medical educators prioritize both principles and practice. This approach will help derive optimal educational outcomes from PBL curricula.

Acknowledgments

All individuals included in this section have consented to the acknowledgment.

Disclosure statement

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines. None of the authors have any conflict of interest to disclose.

Data availability statement

All data supporting the reported results are available in the original studies included in the systematic review and were showed in figures and tables included in the present manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Xinyu Hu

Xinyu Hu, is a medical postgraduate at the Department of Neurology, Union hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China.

Jingwen Li

Jingwen Li, is a medical postgraduate at the Department of Neurology, Union hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China.

Xinyi Wang

Xinyi Wang, is a medical postgraduate at the Department of Neurology, Union hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China.

Kexin Guo

Kexin Guo, is a chief physician at the Department of Neurology, Union hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China.

Hanshu Liu

Hanshu Liu, is a medical postgraduate at the Department of Neurology, Union hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China.

Qinwei Yu

Qinwei Yu, is a resident physician in the Cardiology Department at Wuhan Red Cross Hospital, China.

Guiying Kuang

Guiying Kuang, is a resident physician in the Neurology Department at Wuhan Red Cross Hospital, China.

Shurui Zhang

Shurui Zhang, is a researcher in Medical Education and Research Institute, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Hubei, China.

Long Liu

Long Liu, is a researcher in Office of Academic Affairs, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Hubei, China.

Zhicheng Lin

Zhicheng Lin, is a member of the Oligonucleotide Therapeutics Society, current research interests are precision medicine and development of treatment for brain disorders.

Yaling Huang

Yaling Huang, is a professor in the Department of Pediatrics, First Clinical College, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Nian Xiong

Nian Xiong, is a Researcher at the Department of Neurology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

References

- Hong FF. History of medicine in China when medicine took an alternative path. McGill J Med. 2020;8:79–84. doi: 10.26443/mjm.v8i1.381

- Xu D, Sun B, Wan X, et al. Reformation of medical education in China. Lancet. 2010;375(9725):1502–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60241-3

- Lam TP, Lam YYB. Medical education reform: the Asian experience. Acad Med. 2009;84(9):1313–1317. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b18189

- Wood DF. Problem based learning. BMJ. 2008;336(7651):971–971. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39546.716053.80

- Zheng Y, Stein R, Kwan T, et al. Evolving cardiovascular disease prevalence, mortality, risk factors, and the metabolic syndrome in China. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32(9):491–497. doi: 10.1002/clc.20605

- Zhao P, Dai M, Chen W, et al. Cancer trends in China. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40(4):281–285. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp187

- Wang Q. Forecast analysis of health service demand and supply in China during the 14th Five-Year Plan period. 2023. Shandong university, 2023;02:79. doi: 10.27272 /, dc nki. Gshdu. 2022.002548.

- Kang W. Thinking on the introduction of high-level talents in medical colleges and universities. Med Educ Adm. 2022;8:202–204 + 208.

- Hoy RR. Quantitative skills in undergraduate neuroscience education in the age of big data. Neurosci Lett. 2021;759:136074. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2021.136074

- Cui Z, Li S, Gao H, et al. Analysis of the status quo and countermeasures of clinical medical graduate humanities education under the background of great ideological and political affairs. Chin Med Humanit. 2023;9:8–11.

- Ran H. Study on the promoting effect of computer science and technology on economic development. Digit World. 2019;01:70.

- Huang Y, Zheng X, Jin R, et al. Exploration of PBL teaching mode. Med Soc. 2005;06:56–57.

- Divito CB, Katchikian BM, Gruenwald JE, et al. The tools of the future are the challenges of today: the use of ChatGPT in problem-based learning medical education. Med Teach. 2023;46:320–322.

- Wei W. Discussion on the path of entrepreneurship awareness and ability education for medical students under the background of Healthy China strategy. J Jiamusi Vocat Coll. 2019; 09:67–68.

- Polyzois I, Claffey N, Mattheos N. Problem-based learning in academic health education. A systematic literature review. Eur J Dent Educ. 2010;14(1):55–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2009.00593.x

- Lam T-P, Wan X-H, Ip MS. Current perspectives on medical education in China. Med Educ. 2006;40(10):940–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02552.x

- Field M, Geffen L, Walters T. Current perspectives on medical education in China. Med Educ. 2006;40(10):938–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02604.x

- Huang Y, Zheng X, Jin R, et al. Study on adaptability of seven-year medical students to problem-based teaching model. Chin J Med Educ. 2006;4:45–46.

- Chan SCC, Gondhalekar AR, Choa G, et al. Adoption of problem-based learning in medical schools in Non-Western Countries: a systematic review. Teach Learn Med. 2022;36:111–122.

- Park YL, Huang CW, Sasaki Y, et al. Comparative study on the education system of traditional medicine in China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. Explore. 2016;12(5):375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2016.06.004

- Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D’Amico R, et al. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7(27):1–173.

- Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, et al. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(1):12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x

- Jackson N, Waters E. Criteria for the systematic review of health promotion and public health interventions. Health Promot Int. 2005;20(4):367–374. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dai022

- Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, et al. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x

- Bai S, Zhang L, Ye Z, et al. The benefits of using atypical presentations and rare diseases in problem-based learning in undergraduate medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04079-6

- Xu X, Wang Y, Zhang S, et al. Performance of problem-based learning based image teaching in clinical emergency teaching. Front Genet. 2022;13:931640. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.931640

- Wang H, Xuan J, Liu L, et al. Problem-based learning and case-based learning in dental education. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(14):1137–1137. doi: 10.21037/atm-21-165

- Peng W-S, Wang L, Zhang H, et al. Application of virtual scenario simulation combined with problem-based learning for paediatric medical students. J Int Med Res. 2021;49(2):300060520979210. doi: 10.1177/0300060520979210

- Zheng S, Zhang M, Zhao C, et al. The effect of PBL combined with comparative nursing rounds on the teaching of nursing for traumatology. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13(4):3618–3625.

- Li X, Xie F, Li X, et al. Development, application, and evaluation of a problem-based learning method in clinical laboratory education. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;510:681–684. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.08.037

- Pu D, Ni J, Song D, et al. Influence of critical thinking disposition on the learning efficiency of problem-based learning in undergraduate medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:1.

- Ding Y, Zhang P. Practice and effectiveness of web-based problem-based learning approach in a large class-size system: a comparative study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2018;31:161–164. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2018.06.009

- Cong L, Yan Q, Sun C, et al. Effect of problem and scripting-based learning on spine surgical trainees’ learning outcomes. Eur Spine J. 2017;26(12):3068–3074. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5135-2

- Bai X, Zhang X, Wang X, et al. Follow-up assessment of problem-based learning in dental alveolar surgery education: a pilot trial. Int Dent J. 2017;67(3):180–185. doi: 10.1111/idj.12275

- Du Y. 2017. The application of PBL teaching method in the teaching of traditional chinese medicine nursing. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Education, Management, Information and Mechanical Engineering (EMIM 2017). Shenyang, China: Atlantis Press. doi: 10.2991/emim-17.2017.296

- Li H, Wang C, Zhang C, et al. Application of PBL method in the experimental teaching of clinical pharmacology. Atlantis Press; 2016; p. 57–60. doi: 10.2991/sshme-16.2016.11

- Rui Z, Rong-Zheng Y, Hong-Yu Q, et al. Preliminary investigation into application of problem-based learning in the practical teaching of diagnostics. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:223–229. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S78893

- Yu D, Zhang Y, Xu Y, et al. Improvement in critical thinking dispositions of undergraduate nursing students through problem-based learning: a crossover-experimental study. J Nurs Educ. 2013;52(10):574–581. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20130924-02

- Lian J, He F. Improved performance of students instructed in a hybrid PBL format. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2013;41(1):5–10. doi: 10.1002/bmb.20666

- Li J, Li QL, Li J, et al. Comparison of three problem-based learning conditions (real patients, digital and paper) with lecture-based learning in a dermatology course: a prospective randomized study from China. Med Teach. 2013;35(2):e963–970. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.719651

- Tian J-H, Yang K-H, Liu A-P. Problem-based learning in evidence-based medicine courses at Lanzhou University. Med Teach. 2012;34(4):341–341. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.531169

- Zhang Y, Chen G, Fang X, et al. Problem-based learning in oral and maxillofacial surgery education: the shanghai hybrid. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(1):e7–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.03.038

- Wang J, Zhang W, Qin L, et al. Problem-based learning in regional anatomy education at Peking University. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3(3):121–126. doi: 10.1002/ase.151

- Kong J, Li X, Wang Y, et al. Effect of digital problem-based learning cases on student learning outcomes in ophthalmology courses. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(9):1211–1214. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.110

- Ma J. Long-term effect of a web-based problem-based learning in medical statistics in China. Conf. Creat. Educ. 2012:18–21.

- Luo L, Yang X, Gao X, et al. Application of problem-based learning (PBL) in higher medical education. Educ Teach Forum. 2017;15:170–171.

- Bassir SH, Sadr-Eshkevari P, Amirikhorheh S, et al. Problem-based learning in dental education: a systematic review of the literature. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(1):98–109.

- Choon-Eng Gwee M. Globalization of problem-based learning (PBL): cross-cultural implications. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2008;24(3 Suppl):S14–S22. doi: 10.1016/s1607-551x(08)70089-5

- Khoo HE. Implementation of problem-based learning in Asian medical schools and students’ perceptions of their experience. Med Educ. 2003;37(5):401–409. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01489.x

- Zhang X, Zhang G, Liu J, et al. Cross-sectional study of the quality of randomized control trials on problem-based learning in medical education. Clin Anat. 2023;36(1):151–160. doi: 10.1002/ca.23977

- Wang C. Comparison of PBL studies at home and abroad and its implications. Text Garment Educ. 2013;28:84–86.

- Ding X. Foreign research on ‘problem-based learning’ and its implications for “research-based learning."Capital Normal University, 2009;10:68.

- Cao H, Yan Y, Yu C, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the evaluation of acupuncture teaching effect in Chinese medical colleges with PBL teaching mode. TCM Educ. 2020;39:41–49.

- Lang G, Han Y. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of PBL teaching method applied in pharmacology teaching. Contin Med Educ China. 2023;15:89–94.

- Sheng G, Dong R, Zhou Y, et al. Meta-analysis of the effect of online PBL teaching on the effectiveness of medical teaching. Med Educ Zhejiang. 2023;22:147–154.

- Zhang Y. Application of PBL teaching model in medical education in China. Worlds Latest Med Inf Dig. 2018;18:280–281.

- Zhou B, Yuan H. Application progress and enlightenment of PBL in medical education. China Med Guide. 2017;14:120–123.

- D’Antoni AV, Zipp GP, Olson VG, et al. Does the mind map learning strategy facilitate information retrieval and critical thinking in medical students? BMC Med Educ. 2010;10(1):61. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-61

- Zhang G, Wang W, Xu F, et al. Application of Internet platform tools to assist PBL in teaching of medical students. Contin Med Educ China. 2022;14:77–81.