Abstract

This article advances current conceptions of teacher activism through an exploration of the social justice dispositions of teachers in advantaged and disadvantaged contexts of schooling. We interrogate the practices of teachers in a government school, with a high proportion of refugee students and students from low socio-economic backgrounds, in a high-fees, multi-campus independent school, and in a disadvantaged Systemic Catholic school to illustrate how Bourdieu’s notion of dispositions (which are constitutive of the habitus) and Fraser’s distinction between affirmative and transformative justice are together productive of four types of teacher activism. Specifically, we show that activist dispositions can be characterised as either affirmative or transformative in stance and as either internally or externally focused in relation to the education field. We argue that the social, cultural and material conditions of schools are linked to teachers’ activist dispositions and conclude with the challenge for redressing educational inequalities by fostering a transformative activism in teachers’ practices.

Introduction

Despite the best efforts of policy-makers and teachers to address educational inequality, the research evidence (Dorling Citation2011; Gonski et al. Citation2011; Piketty Citation2014; Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2009) finds that the educational attainment gap between students from high and low socio-economic backgrounds continues to grow. Like in many Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) nations (ETUC and ETUI 2012; Le Donné Citation2014; NESSE Citation2012; OECD Citation2010; UNICEF Citation2010), the most disadvantaged students in Australia have diminished opportunities to gain from education (Connors and McMorrow Citation2015; Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2009). There is an urgent need for new ways to understand how these inequalities are being enacted in and through educational practices, and to identify how more socially just outcomes might be achieved. The challenges in achieving this are numerous and complex, given that the gap between those at the highest and lowest ends of attainment is increasingly widening. Yet many policy-makers, school leaders and classroom practitioners claim that they are committed to a fair, equitable and socially just system of schooling. We see educational inequalities being addressed through a reconfiguration of systems producing inequitable practices, but also through the practices of teachers – and particularly those that exemplify transformative activism, which pursue a politics and practice of transformation by engaging with the deep structures that generate injustice – to produce alternate outcomes.

In this article, we utilise the analytical category of ‘social justice dispositions’ (Mills et al. Citation2017; Gale and Molla Citation2017) as this applies to teachers, to better understand how educational inequalities are perpetuated in advanced market-driven democracies. In particular, we focus on the disposition of some teachers to be social justice activists in their teacher practice. We begin with a short account of how we understand ‘disposition’ as a concept and of our approach to researching it in schools. This provides the starting point for our theorising of activism as a social justice disposition, informed by the interplay between the work of Judith Sachs (Citation2001) and Nancy Fraser (Citation1997) and by our data. Drawing on this conceptual work, we then illustrate how teachers’ practices can be conceived within a four-quadrant schema of activism for social justice, distinguishable by their affirmative or transformative stance and by their internal or external orientations. We use this analysis to show that teacher activism, and social justice dispositions more broadly, are contextually contingent. We conclude that the challenge for redressing educational inequalities is how to foster a transformative activism in teachers’ practices, particularly (but not only) by those who work in schools that are educationally and materially advantaged.

A conceptual and methodological approach to researching educational inequality

Our analysis draws on data from a large Australian Research Council project, focused on the social justice dispositions of teachers in schools. The project took a multi-layered, qualitative case-study approach to investigate teachers’ pedagogic work in 10 secondary school sites – six advantaged and four disadvantaged – in two Australian cities. The number of participants was intentionally contained to enable in-depth and intense examination of the social justice dispositions evident in their practice.

Disposition is often understood in the education research literature as a largely psychological construct (Conderman and Walker Citation2015; Englehart et al. Citation2012; Wadlington and Wadlington Citation2011). In contrast, we employ a Bourdieuian framing of disposition: as the tendencies, inclinations and leanings that provide un-thought or pre-thought guidance for social practices (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). In our view, this helps reconcile the dissonance sometimes observed between what teachers believe and what they do (their practice); for example, belief in gender equality and yet practices that are patriarchal (Sadker and Sadker Citation1995). From a Bourdieuian perspective, practice is an expression of the habitus: an internalised system of ‘durable, transposable dispositions, structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures, that is, as principles which generate and organize practices and representations’ (Bourdieu Citation1990b, 53; emphasis added). As a set of generative dispositions, the habitus guides actions and interactions in a field of practice (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). These tendencies, inclinations and leanings provide un-thought or pre-thought guidance for practice, which orients actions without strictly determining them. They operate as a ‘strategy-generating principle enabling agents to cope with unforeseen and ever-changing situations’ (Bourdieu Citation1977, 72). In practice, dispositions signal an unthinking-ness in action or a ‘feel for the game’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992), representing subjectively internalised social structures. Extrapolating from this, we theorise the social justice dispositions of teachers to be the un-thought or pre-thought yet enduring, recurring and repetitious patterns of social interactions that play out in teachers’ engagement with students, in ways that they sense as being socially just, equitable or fair.

Dispositions are difficult to research using conventional methodological techniques, such as traditional interviews (which focus on what is said) or observations (what is done), because they operate in the unconscious realm between belief and practice. Bourdieu and Wacquant (Citation1992) note that dispositions are revealed in actions, which provides a way forward but still necessitates a technique that enables participants to ‘speak to practice’: data are not produced by simply asking participants to discuss their commitments to or values in practice, but through provocations that require them to reflect on and search internally for explanations for their actions in which those dispositions are manifest. Rather than interpret dispositions from observations of teachers’ practice, we took the view that, with provocation, teachers are able to speak their own dispositions, albeit through our interpretation of what they say about their practice.

Thus informed, the research was conducted over three stages of ‘stimulation’ (Gass and Mackey Citation2000) designed to provoke participants into speaking their habitus, to speak the unconscious; specifically, ‘stimulated consciousness awakening’ (Bourdieu Citation1990b), ‘stimulated recall’ (Calderhead Citation1981) and ‘stimulated critique’ (Gale and Molla Citation2017). Provocation in the first stage came from the juxtaposition of potentially contradictory or inconsistent remarks in the context of in-depth semi-structured interviews with school principals. In the second stage, provocation was in the context of in-depth semi-structured interviews with teachers responding to video clips of their own teaching. In the final stage, provocation occurred in the context of in-depth semi-structured interviews with teachers responding to video clips of the teaching of other teachers in the study. (See Gale and Molla [Citation2017] for a more in-depth account of this methodology.) Although we videoed teachers’ practice, we did not regard these videos as data for analysis but as stimulation in the context of interviewing teachers.

Our conversations with principals and teachers focused on the social interactions and social arrangements that characterise what it means to teach in that particular setting, with special attention in our analysis on the emphases and repetitions that they provided in their account of teaching. For participants, these extended interviews provided a forum to reflect on their actions and to ‘speak’ their social justice dispositions. These conversations also helped us to understand how various contexts interact with teachers’ dispositions to influence practices in ways that either help or hinder the realisation of more socially just outcomes in differently positioned sites of schooling.

The data we use in this article come from three schools, selected because activism was particularly evident among their teachers. They are also contrasting schools: one (Heyington College)1 is an elite, high fees, multi-campus, private school; while another (Marrangba High School) is a government school, in an inner suburban area, with a high proportion of refugee students and students from low socio-economic backgrounds; and the third (St Leo’s College) is a disadvantaged Systemic Catholic school. The schools are also located in the suburbs of two large cities on Australia’s east coast.

Activism as a disposition productive of social justice practice

While the interest of the broader research project was on social justice dispositions, in this article we focus on one aspect of these dispositions that became prominent from our analysis; that is, activist dispositions, or more precisely activism directed at achieving socially just ends.

Judyth Sachs describes an activist teacher identity as having clear emancipatory aims, ‘concerned to reduce or eliminate exploitation, inequality and oppression’ (2001, 157). Its development is ‘deeply rooted in principles of equity and social justice’ (2001, 157). Similarly, we understand activism-as-disposition as the tendency or inclination to struggle against the social order or doxa (Bourdieu Citation1977). Evident in the subtleties of everyday practice, activism-as-disposition also reveals itself in ‘the immediate adjustment of the habitus to the field’ (Bourdieu Citation1990a, 108), emerging in times of crisis as a ‘radical critique’ of doxa. Sachs (Citation2001, Citation2003) uses the terms ‘activist’ and ‘transformative’ interchangeably to describe teachers with emancipatory professional identities. However, drawing on Fraser (Citation1997), we characterise social justice practice produced by an activist disposition as either affirmative or transformative. An affirmative activist disposition relies on what Fraser refers to as affirmative justice – an approach to ameliorating the effects of injustice and disadvantage. This view of social justice entails actions or ‘remedies aimed at correcting inequitable outcomes of social arrangements without disturbing the underlying framework that generates them’ (Fraser Citation1997, 23; emphases added). Affirmative remedies, Fraser notes:

have been associated historically with the liberal welfare state. They seek to redress end-state maldistribution, while leaving intact much of the underlying political-economic structure. Thus they would increase the consumption share of economically disadvantaged groups, without otherwise restructuring the system of production. (1997, 24)

This ‘top-up’ activism is reminiscent of a liberal-democratic form of redistributive justice. Also known as ‘simple equality’ (Walzer Citation1983), it regards all individuals as having the same basic needs. Advocates of simple equality are tied to principles of redistribution such that where inequality exists, their concern is primarily with shifting enough resources or opportunities from advantaged to disadvantaged groups in order to compensate the disadvantaged for their perceived deficits and meet their (dominantly determined) needs (Gale and Densmore Citation2000). While well intentioned, such accounts fall short of delivering social justice, as they affirm unjust social arrangements.

In contrast, we understand transformative activism as responding to Fraser’s challenge to move beyond recognition and pursue a politics and practice of transformation by engaging with deep structures that generate injustice. Fraser refers particularly to ‘transformative remedies’ as those ‘remedies aimed at correcting inequitable outcomes precisely by restructuring the underlying generative framework’ (1997, 23). Historically associated with socialism, transformative practices or remedies:

redress unjust distribution by transforming the underlying political-economic structure. By restructuring the relations of production, these remedies would not only alter the end-state distribution of consumption shares; they would also change the social division of labor and thus the conditions of existence for everyone. (Fraser Citation1997, 24–25)

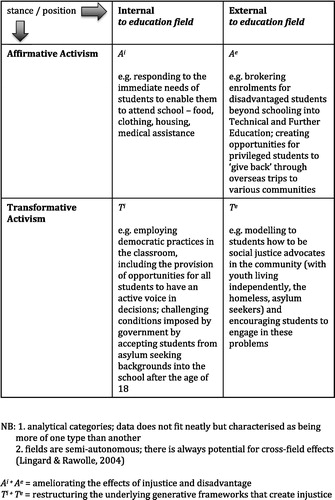

As our research illustrates in the following, these two types of activism – affirmative and transformative – can each be differently orientated: towards change internal to the education field, in innovations such as inclusive pedagogies and curricula; or towards external change, focused on practices, policies and social structures that exist outside the domain of schools. Relating these two activist dispositions with the different foci of the practice they generate, the resulting four-quadrant schema is represented in . In the figure, both Aiand Ae represent affirmative activist dispositions (with a focus on ameliorating the effects of injustice and disadvantage), while Ti and Te are transformative (concerned with restructuring the underlying generative frameworks that create injustice). Forms of activism represented in our data do not always fall easily into one type or another, although we have included examples of the kinds of practices that might best fit into each category. At times, teacher practice can be seen to encompass more than one type of activism, or involve actions that move from one type towards another. For example, affirmative strategies can exhibit some aspects of transformative activism when they begin to transcend the internal boundaries of school. While our intent is to build a deeper theoretical account of teacher activism, in our analysis of the data we also acknowledge these overlaps and intersections.

Figure 1. Forms of activist social justice dispositions. Note: Analytical categories; data do not fit neatly but are characterised as being more of one type than another. Fields are semi-autonomous; there is always potential for cross-field effects (Lingard and Rawolle Citation2004). Ai + Ae = ameliorating the effects of injustice and disadvantage. Ti + Te = restructuring the underlying generative frameworks that create injustice.

This schema of activist disposition and practice orientation also drew our attention to the implications for teacher activism within schools of different social, cultural and material conditions; that is, whether different activist dispositions are evident in teachers differently positioned. In particular, we were interested to explore the contribution of context to the development of activism as either affirmative or transformative in stance, or with an orientation internal or external to the education field. These are issues taken up more fully in the Conclusion, following our account of the data illustrative of each quadrant.

Affirmative activist disposition generative of internally focused practices (Ai)

In our schema, one form of affirmative activism is oriented towards matters internal to fields, such as schools. While this disposition is identifiable in teachers’ efforts to correct inequitable outcomes (Fraser Citation1997), it is work typically focused on and from within the local context.

This was evident at one of the sites in our study, Marrangba High School, a co-educational government secondary school located in a metropolitan area of a major city on Australia’s eastern coast. The school serves a socio-economically disadvantaged population and is frequently identified within the broader community as a ‘refugee’ school, given its high proportion of students who arrive in Australia on humanitarian visas. According to the principal, the school caters for about one-quarter of all refugee students in the city area. Many of the school’s students do not live with their parents. Instead, they rely on government-based family services agencies and, due to their refugee backgrounds, many have experienced long gaps in their formal education. As Dean (the principal) explains, ‘two out of every three kids out there in every classroom need some sort of support … We’ve got disadvantage everywhere’. The school seeks to address this by providing:

opportunities for all. Not necessarily equal opportunities, but the opportunities for everyone to move forward. And some people have to move a further distance than others, and there’s certain levels of support that we need to put in place to support those kids in moving forward. (Dean, principal, Marrangba High School)

To be able to provide these ‘opportunities for everyone to move forward’, Marrangba seeks to create a school environment ‘that is like a family, a second home for kids [where] they feel safe’ and can ‘focus on the business of learning’ (Dean). Many staff in the school ‘spend a lot of time making sure that’s right’, that the environment is conducive to learning, including ensuring students have enough food and a secure place to sleep, because there is ‘no way in the world they are going to focus on learning if they’re worrying about their next feed or … where they’re sleeping tonight’ (Dean).

A similar disposition was evident at St Leo’s College, a co-educational secondary school established in the Catholic tradition. Part of a larger network of schools, St Leo’s serves a socio-economically disadvantaged population and shares a mission with other schools in the network to educate the poor. As Kathleen (a member of the School’s Executive team) shares, the founder of the network:

set up a number of … schools … for kids who couldn’t afford to go to the school … So we follow on from that call to offer an inclusive education to a range of students regardless of their background or their race, or their financial situation … We have a number of non-paying school students simply because they can’t afford to [pay]. (Kathleen, executive team member, St Leo’s College)

Indeed, St Leo’s is committed to ‘enrol[ling] everybody and accept[ing] and include[ing] everybody’ (Wendy, teacher at St Leo’s College), regardless of their financial circumstances. ‘We’ve got parents who pay maybe a fiver [five dollars] a week out of their [government assistance payments] … But we would never ever turn a kid away because of money’ (Wendy, Teacher, St Leo’s College).

Wendy, a teacher within the school, discussed attempts at St Leo’s to ameliorate the effects of injustice and disadvantage as necessarily encompassing ‘the step before’ learning:

In this school, before you can even start doing assignments … [Students] can’t get here … They don’t have enough to eat … They’re sick and they haven’t been able to go to a doctor … They haven’t got a uniform. Just the million small things that would stop a child from getting to school, or functioning at school … So it’s a matter of enabling them to come to school as opposed to just doing the curriculum … It’s the step before. (Wendy, Teacher, St Leo’s College)

This concern with addressing the immediate material needs of students is, by necessity, an affirmative approach to social justice. It is also locally focused. As Dean explains, for other schools:

in a high socioeconomic area … the number of issues that would hit me [if I was the principal] each day would be significantly less and as a result of that it’s not on your immediate radar … [But] in a school like this … because of the nature of disadvantage it’s on your radar every day, every minute … [It’s] our core business. (Dean, principal, Marrangba High School)

Teachers at both Marrangba and St Leo’s are ‘immersed in disadvantage … every day’ (Dean), consumed by the immediacy of their students’ needs. Issues external to the school are ‘on the radar’ to the extent that they directly involve their students’ welfare or interests. Hence, the affirmative activist dispositions of some teachers translate into brokering enrolments for their students into post-school vocational colleges as viable alternatives to futures of unemployment and under-employment.

It is difficult to say whether these teachers have activist dispositions generative of practices focused on internal school affairs because they work at schools like Marrangba or St Leo’s, or they work at these schools because they are that way inclined. According to Dean, ‘we’d like to say we live and breathe it every day, but if we weren’t here would we breathe it every day? The answer is yes, we would.’ This suggests no role for the school in formation of teachers’ social justice dispositions, although the immediacy of local needs would appear to frame their activism within the confines of their immediate context.

Affirmative activist disposition generative of externally focused practices (Ae)

An affirmative activist disposition can also be externally focused. While efforts aimed at ameliorating the effects of injustice and disadvantage outside the field of schooling are evident, the remedies leave intact much of the underlying political-economic structure (Fraser Citation1997).

As already implied, affirmative activism directed at sites beyond the school was evident in the practices of teachers at Marrangba, who engaged their students in ‘practical’ or ‘applied’ work in the belief that many of them ‘can’t go to Uni, they’re not ready … to take that challenge’ (Dean, principal, Marrangba High School). As Dean explains:

We broker enrolments into TAFE [technical and further education] … We work our butts off to make sure our kids have some sort of success in their lives … It’s like our contribution to the public community. Because … we’re taking these refugees in, and if we … don’t provide opportunities for them they’re going to be … unemployed. (Emphasis added)

While brokering enrolments for students into further education exemplifies the school’s appreciation of the urgency of correcting inequitable outcomes of social arrangements, this work does not involve changing the conditions that generate inequitable outcomes. Indeed, they reinforce them.

This disposition was also discernible at Heyington College, a school in a markedly different socio-economic context. Despite the school’s affluence, Glenn, the principal, describes himself as having a strong social justice agenda. He recognises the school’s students as privileged and feels that it is his responsibility as the school leader to ensure that the school creates opportunities for the students to ‘give back’. Glenn describes the school’s mission as developing:

high achieving students who are connected globally to each other and to the communities in which they live, and which they will serve. So, within that mission statement is that component of service, and that component of connection to communities, and that component of justice. (Glenn, principal, Heyington College)

Associated with this mission are many opportunities for students to be involved in overseas trips to places like Sri Lanka and East Timor. As Glenn explains, there are up to ‘15 or 16 different trips around the world each year … and every one of those trips has a component … [of] engaging with a community in a different area’.

An affirmative activist social justice disposition could be said to be apparent in Glenn’s commitment to encouraging students to engage and connect with communities in socially just ways. But it might also be possible that mobilising students to ‘give back’ could simultaneously be compatible with a restructuring of the underlying framework that generates disadvantage, albeit that the students’ activism is from a position of privilege.

Transformative activist disposition generative of internally focused practices (Ti)

An activist social justice disposition can also be transformative in stance and internally oriented in relation to the education field. Evident in this disposition is the pursuit of transformation through an engagement within the schooling context with the deep structures that generate injustice.

At Marrangba, this disposition was evident in the work of Michael, a teacher of English as an additional language or dialect, who aims for ‘democracy in a classroom, and ensuring that all students are heard, and have a voice’. In explaining his evoking of democracy, Michael said: ‘I view [the classroom] as a democratic place … It should be a place where people can voice their opinions about things and it should be a fair place where everyone gets a say.’

Michael’s focus here is on political injustice, which is informed by the principle of representative justice (Fraser Citation1997). Representative justice goes beyond an affirmative politics and is centrally concerned with whether or not individuals or groups have an equal right to be heard and accorded a voice. In an educational context, a focus on representative justice can be transformative in nature through its insistence on opportunities for students to have an active and attended voice in decisions that matter to them – for example, in relation to what they learn, how they learn and when they learn. Transformation in this context has much in common with self-determination: the participation of groups in making decisions that directly concern them, through their representation on determining bodies (Gale and Densmore Citation2000).

At St Leo’s, transformative internally focused activist dispositions are evident in the commitment of staff to students who are from asylum-seeking backgrounds. As Greg explains:

There’s no support for kids who are children of asylum seekers if they’re living in community detention … There’s no funding for those kids. So if those kids want to go to a normal school, the school actually has to support it themselves … We picked up a young asylum seeker this term … He did six months at a [government secondary school] which specifically deals with new arrivals. He turned 18 in … September, and the school had to throw him out … They were getting minimal [government] funding for him. So [the school] approached us and said, ‘Would you take him?’ (Greg, principal, St Leo’s College)

Kathleen continued:

He was a young man desperate for an education … And he had nowhere to go … And we know that he won’t be able to contribute to his education … But part of our mission is, of course; of course we will take him! (Kathleen, executive team member, St Leo’s College)

St Leo’s is well known within the community as being the school of the second chance. As Greg explains, if you look at the story of the founder, schools were set up for kids ‘who had nowhere else to go because they’d been booted out of everywhere else; both homes and society … So that’s basically what [St Leo’s is] all about’.

These practices exemplify attempts to transform rather than support the inequitable structures and practices of schooling (Luke Citation2003). The school pursues a politics of transformation in this example by engaging with structures that generate injustice within the field of schooling – challenging conditions imposed by the government by accepting students from asylum-seeking backgrounds into the school after the age of 18 years. The staff recognise that turning students away from the school who have ‘nowhere else to go’ is likely to compound disadvantage for already marginalised students and contribute to what Fraser (Citation1997, 13) describes as economic marginalisation – ‘being confined to undesirable or poorly paid work or being denied access to income-generating labor altogether’ – or deprivation – ‘being denied an adequate material standard of living’. These examples of socio-economic injustice play a part in widening the gap between those at the highest and lowest ends of attainment (Dorling Citation2011). As a school, the staff take collective action within the education field to instead pursue strategies to retain students in schooling and ‘undo the vicious circle of economic … subordination’ (Fraser Citation1997, 29).

Transformative activist dispositions generative of externally focused practices (Te)

While our schema includes an activist disposition that can be transformative and externally oriented in relation to the education field, in practice this was not readily evident in two of the schools we researched. What did seem possible in these schools, however, was a sense that Ti could move towards Te through the pedagogic work of teachers; addressing issues outside the school from within, in ways that challenge the underlying generative frameworks which create injustice.

For example, Thomas, a history teacher at Marrangba, shared with us a lesson he taught with an explicit focus on female empowerment:

We’re doing suffragettes … in modern history and I’ve shown [the students] … stuff from the 1950s and what it means to be a good woman … When your man comes home, be quiet and let him relax and make sure the kids are clean … So I’m actively challenging this in our curriculum and it’s really important because … we have a lot of students from a Muslim background where there’s a cultural misogyny … where in many ways the girls are like a servant … whereas the boys can do no wrong … So it’s great to challenge that and to discuss it and to empower not just for girls but also … for the boys to understand that it is about equality. (Thomas, teacher, Marrangba High School)

In Thomas’ view, this kind of work is required within schools to enable:

social cohesion and harmony and moving forward together. And it’s not just multiculturalism but it breaks up class barriers as well and it breaks down all the ‘isms’, we’re dealing with sexism, we’re dealing with racism, we’re dealing with homophobia and we’re working towards … the utopian ideal.

Thomas’ disposition towards social justice is demonstrated in his overt teaching about oppression and empowerment to enable students to understand and, in time, change their situation. The practices that evidence this type of activist disposition pursue transformation through exposing students, within the context of schooling, to situations of disadvantage and marginalisation, encouraging them to reflect on and engage with the deep structures that generate injustice. While this does not constitute externally focused transformative pedagogy as such, the way in which Thomas brings into the classroom issues of inequality ostensibly occurring outside the classroom is suggestive of the possibility of moving beyond Ti to Te.

Other examples in our research were suggestive of a potentially alternative route to Te from Ae. For example, at Heyington College there is a strong tradition of fundraising, with each of the pastoral care groups required to commit to a philanthropic activity. Both of the teachers interviewed at Heyington spoke of their frustration at fundraising being the major focus of social justice work in the school context. Glenn said: ‘people just feel like there’s too much raising money for charities … and I agree with that. We are trying to shift that’ (principal, Heyington College). Angela, too, said: ‘What we’re really trying to move away from is having fundraising, give a gold coin kind of event and really be about awareness raising and making connections with people’ (teacher, Heyington College; emphasis added).

Recognition of the need to move beyond compensatory remedies – such as fundraising and doing good works – to address the issues more fundamentally is really only hinted at here, but it is suggestive of the possibility. More transformative activism in advantaged school contexts might involve volunteering and active engagement in local contexts, in ways that are informed and/or determined by outside agencies.

Progression from affirmation to transformation can also be seen in attempts to position students at Heyington as future leaders of social justice activity who are being prepared to contribute to society in transformative ways beyond the education field. As the principal commented:

As a wealthy and elite institution, [we have an obligation] to provide some level of opportunity in society. The best thing we can do, I think, is to have our students aware of their own good fortune, to be a part of the sort of families that they are a part of, to get the education that they have got to be a part of and within that to recognise that a vast significant number of our students are going to enjoy great success in their life and set them up in a way that they understand the breadth that is out there in society and have some notion of then being able to contribute, serve, give back, build structures that will actually build a stronger society overall. (Glenn, principal, Heyington College)

Under Glenn’s leadership, education at this elite institution is viewed as having the potential to ‘build a stronger society’ through developing students who have an understanding of what it means to ‘contribute, serve, give back’. Yet this development also needs to include a commitment to transforming conditions of injustice and subordination. In short, mobilising students to ‘give back’ needs to simultaneously develop tendencies to ‘resist, dissent, rebel, subvert, possess oppositional imaginations and [commit] to transforming oppressive and exploitative social relations in and out of schools’ (Rapp Citation2002, 226) to be truly representative of transformative activist dispositions generative of externally focused practices.

However, at St Leo’s, an activist disposition that is transformative and externally oriented was evident. Teachers from the school are committed to running a classroom in a Youth Outreach Service in one of the neighbouring suburbs: ‘We staff that. And it’s there for kids, many of those kids are on the street, or are living independently … This is their last-ditch effort at an education’ (Kathleen, executive team member, St Leo’s College). Kathleen explains that:

we wouldn’t expect those kids to be able to afford to pay fees, but nor would we also expect for those kids to be able to buy school uniforms. So that would be our job to make sure that when that student came, to what for them would be quite an unfamiliar setting, because many of them have been disengaged from schooling for a long period of time … that they felt absolutely no different from any other member of the student population as they went in the gates.

Externally focused transformative activist dispositions were also evident in St Leo’s staff modelling activism to the school’s students:

We model social justice with activities … [Staff and students regularly volunteer at a] homeless van … We … have a group that goes to [a non-profit organisation that helps seriously ill children and their families] once a week … We’ve got a group that does some work with [a charity that helps young people with high care needs] … So we’re teaching kids how to be advocates for social justice issues. The one that they have been really involved in is looking at the issues of asylum seekers … Students … staged what was called detention for detention, where we probably had … half of the school turn up on a lunch hour with … their lips taped and their hands tied behind their backs … and they stood silently in solidarity with those young people who were in detention centres. (Kathleen, executive team member, St Leo’s College)

What is common to these examples is the commitment of teachers to engaging with structures, policies and practices that generate injustice and subordination outside the domain of schooling. This commitment extends to modelling to their own students what a transformative activist disposition generative of externally focused practices looks like; ‘teaching kids how to be advocates for social justice’ through exposing students to situations of disadvantage and marginalisation and encouraging them to reflect on and engage in the problem. In doing so, students themselves become part of the circle of recognition of undesirable conditions of inequality but, importantly, develop appreciation of the urgency of being part of the work of changing these conditions.

Context and the enactment of activist social justice dispositions

Evident in our research is that the social, cultural and material conditions of schools are linked to different types of activist social justice dispositions evident in the work of individual teachers. That is, the context of a school is a particularly important factor contributing to the expression of activism as either affirmative or transformative in stance, and internally or externally oriented to the education field.

The view that social justice dispositions are shaped by school contexts is shared by Dean, who suggests that:

every one of us has got some sort of social justice seed within us and circumstances make that seed grow. And as a teacher it depends upon the circumstances in the schools and the environment, in the community that you work in. (Principal, Marrangba High School)

Echoing the insights of Bourdieu and Passeron (Citation1990), Dean is suggesting here that the formation of social justice dispositions, and activist dispositions in particular, requires the secondary pedagogic work of institutions.

However, it could also be the case that teachers have a tendency to apply for positions in school contexts that they believe will align with their social justice dispositions. At Heyington, for example, Glenn’s (principal, Heyington College) main focus when recruiting staff is that every one of them is ‘capable of delivering academically, because that is still the first priority of the school. We don’t have a school if we don’t deliver academic results that are really at the top level’.

Glenn does, however, reference the final interview he conducts with all teacher applicants, pointing out that he looks for ‘people who are engaged with broader society’:

All the new staff are very, very clear on what our three priorities are: academic, international, and social justice … So, as a part of that discussion I have with them, I do like to explore a little bit about whether they are capable of … looking outward about society and the world. (Principal, Heyington College)

Glenn’s view about what matters in the Heyington context aligns closely with the types of activities that were evident in the work of teachers in the school. Whether affirmative or moving towards being transformative, this activism was externally focused. Providing opportunities for the privileged students of Heyington to develop local and global connections to the communities in which they will live and/or serve; encouraging commitment to philanthropic activity; and developing students who have an understanding of what it means to ‘contribute, serve, give back, build structures that will actually build a stronger society overall’ are all examples of externally focused activism. Perhaps the reduced incidence of material disadvantage within the immediate context of Heyington College contributes to a shift in the gaze of staff to assume a more pressing need for social justice work outside schooling, and the subsequent development of activist social justice dispositions that are externally focused.

While there was evidence of a variety of activist dispositions at St Leo’s, the transformative activist disposition generative of externally focused practices is of particular interest given its lack of prevalence in the other two school contexts. Kathleen (executive team member, St Leo’s College) suggests that ‘when you walk into this community there is a spirit amongst the staff and the kids that you can taste. There’s something different about this place’. In Greg’s (principal, St Leo’s College) view, what is different is the fact that teachers ‘see their whole calling here [is] not only to be a “you-beaut” English teacher … but to make a difference in a kid’s life’. Teaching is described by Kathleen as ‘a calling’, and Greg similarly suggests that ‘people become teachers because … they see a need in people that they think they might be able to make that difference’. There is a strong suggestion that context plays an important role here, although it is unclear whether specific types of teachers are attracted to the school, or whether the school context itself provides opportunities for the development and expression of transformative dispositions.

A Bourdieuian explanation for the alignment that we see in these examples between context and disposition would emphasise that the fields within which teachers’ practice are structured social spaces where complex relationships exist between the field’s objective conditions and subjective individual dispositions (Bourdieu Citation1977). Specifically, ‘the constraints and opportunities imposed by fields’ are mediated through dispositions (Swartz Citation2002, 66S). The dispositions of staff in school contexts appear to be influenced by the structures and norms of the field, disposing them to do what they ‘have to do’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992, 127) without any conscious calculation. Like ‘fish in water’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992, 127), the staff of Marrangba and St Leo’s find themselves ‘immersed in social justice issues’ and are disposed to do what they ‘have to do’. In both of these contexts, their core business is responding to the immediate needs of their students, and at St Leo’s there is an additional focus on engaging with structures that generate injustice for members of the community beyond the school, including youth living independently, the homeless and asylum seekers. At Heyington, where they are further removed from material disadvantage, the impetus for social justice work within schooling is not recognised to the same extent. However, and as articulated previously, it could also be the case that Heyington, Marrangba and St Leo’s, as contexts of employment, appeal to teachers with very different types of social justice dispositions.

While it is tempting to locate analysis at the level of individual teacher activism, it is important that we do not overlook broader and often structural influences, given their complex relationship. That is, the context or institution impacts on possibilities and constraints for individual teachers and their capacity for agency for expression of their activist social justice disposition. Opportunities for transformative activism may be constrained or nurtured by the school in which a teacher is located.

Conclusion: transforming the logic of the field

As Fraser (Citation1997) has indicated, transformative approaches to social justice seek to challenge and reconfigure the underlying social structures that re/produce disadvantage in society. Most of the activism identified in this article tends not to be of this order, or at least not in its fullest sense. Our analysis suggests that much teacher activism is in the form of Ai (affirmative, internal), Ae (affirmative, external) and Ti (transformative, internal) rather than Te (transformative, external). In some cases, there is overlap in the character and foci of the teacher activism identified in our schools. For example, teacher activism at Marrangba tended to be internally focused, often affirmative but also transformative. At Heyington, teacher activism tended to focus on disadvantaged groups external to the school. Yet the aims of these activities seemed to be about ameliorating disadvantage and poverty (through fundraising, for example), rather than addressing the conditions that create them.

As more socio-economically disadvantaged schools, teachers at Marrangba and St Leo’s have to contend with the day-to-day realities of their students living in poverty; much of their work is dedicated to dealing with its effects. As much as we might recognise the need to transform social structures that generate these disadvantages, it is perhaps too much to expect teachers to single-handedly challenge the conditions of disadvantage beyond the school, although we do see this work evident at St Leo’s. As Bernstein (Citation1970) has noted, education cannot compensate for society. That is, while teachers can and do make a difference, there are structural challenges and barriers in doing so. In addition, an analysis of what can and cannot be achieved by teacher activism through a school system in isolation of broader factors (outside of schools) can only ever be a partial one. Nonetheless, the prevalence of material advantage and disadvantage means that teacher activism looks very different at Heyington than at Marrangba and St Leo’s. That is, activism in each context is closely aligned with the particular circumstances of schooling. In other words, certain forms of activism are more possible or appropriate in some contexts than in others. In our research, each school provides a different enabling environment for social justice activism. At Marrangba, teacher activism is both affirmative and transformative but tends to be internally focused. At Heyington, it tends to be more affirmative and externally focused. At St Leo’s, while there is a focus on internal activist work within their own school (both affirmative and transformative), transformative work extends beyond the confines of the school to external contexts.

If then, as we propose, there is a relationship between context and the activist stance of teachers, how can we facilitate movement between forms of activism? Particularly in question here are the problematics of moving from an affirmative to a transformative stance, irrespective of whether that is internally or externally focused.

If social justice dispositions are shaped by school context, or if teachers have a tendency to apply for positions in school contexts that they believe will align with their social justice dispositions, changing or challenging social justice dispositions may require teachers spending periods of time in contrasting school contexts. Key also to this transformation is altering the ‘terms of recognition’ (Taylor Citation1994) in at least two ways. First, we suggest that curricular justice, or a counter-hegemonic curriculum logic (Connell Citation1993), is required. This approach ‘attempts to generalise the point of view of the disadvantaged rather than separate it off. There is an attempt to generalise an egalitarian notion of the good society across the mainstream’ (1993, 52). Second, there is a need for epistemological justice (Dei Citation2010): the recognition of marginalised groups as legitimate authors of knowledge (Harding Citation2004) by ‘paying due attention’ (Dei Citation2008, 8) to what marginalised groups advance as their own knowledge claims. This is in contrast to the current relegation of such knowledge to the academic periphery (Connell Citation2007; Dei Citation2008; Said Citation2000).

In saying this, we do not seek to argue that high-status ‘educational knowledge’ or ‘school knowledge’ should be replaced. However, to have a more transformative effect in schools, pedagogies need to be informed by the belief that all students bring something of value to the learning environment (see Gale, Mills, and Cross Citation2017). That is, students and families should be regarded as vibrant and richly resourced, rather than as bundles of pathologies to be remedied or rectified (Smyth Citation2012). Moll et al. (Citation1992) and Moll and Greenberg (Citation1990) refer to students’ assets as ‘funds of knowledge’, which are ‘historically accumulated and culturally developed bodies of knowledge and skills essential for household or individual functioning and well-being’ (Moll et al. Citation1992, 133). The proposition that these other knowledges need to be mobilised:

runs counter to standard educational processes whereby working-class and Indigenous cultures are misrecognised and excluded, and only professional and higher class cultures and knowledges are ratified and become ‘cultural, social and symbolic capital’ that advantages some and disadvantages others (Bourdieu Citation2004). (Wrigley, Lingard, and Thomson Citation2012, 99)

Attempts to pursue a politics of transformation by encouraging a critical gaze on assumptions and norms, and fostering students’ reflection on, and engagement in, the problem of disadvantage and marginalisation within and beyond schools, is the first step for activist teachers who appreciate the urgency of changing conditions of injustice and subordination within society.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Australian Research Council for financial support and acknowledge the generous participation of teachers and principals. The research team included Trevor Gale (Chief Investigator), Russell Cross (Chief Investigator), Carmen Mills (Chief Investigator), Stephen Parker (Research Fellow), Tebeje Molla (Research Fellow) and Catherine Smith (PhD candidate).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The names of schools, places and people used in this article are pseudonyms.

References

- Bernstein, B. 1970. “Education Cannot Compensate for Society.” New Society 26 Feb: 344–347.

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1990a. In Other Words: Essays towards a Reflexive Sociology. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1990b. The Logic of Practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 2004. “The forms of capital.” In The RoutledgeFalmer Reader in Sociology of Education., edited by S. Ball, 15–29. London, England: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P., and J.-C. Passeron. 1990. Reproduction in Education, society and Culture. 2nd ed. Translated by R. Nice. London, England: SAGE.

- Bourdieu, P., and L. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Calderhead, J. 1981. “Stimulated Recall: A Method for Research on Teaching.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 51 (2): 211–217. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.1981.tb02474.x.

- Conderman, G., and D. A. Walker. 2015. “Assessing Dispositions in Teacher Preparation Programs: Are Candidates and Faculty Seeing the Same Thing?” Teacher Educator 50 (3): 215–231. doi: 10.1080/08878730.2015.1010053.

- Connell, R. W. 1993. Schools and Social Justice. Leichhardt, Australia: Pluto.

- Connell, R. 2007. Southern Theory: The Global Dynamics of Knowledge in Social Science. Cambridge, MA: Polity.

- Connors, L., and J. McMorrow. 2015. Imperatives in Schools Funding: Equity, Sustainability and Achievement. Melbourne: Australian Centre for Educational Research.

- Dei, G. J. S. 2008. “Indigenous Knowledge Studies and the Next Generation: Pedagogical Possibilities for anti-colonial Education.” The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 37 (S1): 5–13. doi: 10.1375/S1326011100000326.

- Dei, G. J. S. 2010. Teaching Africa: Towards a Transgressive Pedagogy. Dordrecht, The Netherlands. New York: Springer.

- Dorling, D. 2011. Injustice: Why Social Inequalities Persist. Bristol, England: The Policy Press.

- ETUC and ETUI 2012. Benchmarking Working Europe 2012. Brussels: ETUI.

- Englehart, D. S., H. L. Batchelder, K. L. Jennings, J. R. Wilkerson, W. S. Lang, and D. Quinn. 2012. “Teacher Dispositions: Moving from Assessment to Improvement.” International Journal of Educational and Psychological Assessment 9 (2): 26–44.

- Fraser, N. 1997. Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the ‘postsocialist’ Condition. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Gale, T., and K. Densmore. 2000. Just Schooling: Explorations in the Cultural Politics of Teaching. Buckingham., England: Open University Press.

- Gale, T., C. Mills, and R. Cross. 2017. “Socially Inclusive Teaching: Belief, design, action as Pedagogic Work.” Journal of Teacher Education 68 (3): 345–356. doi: 10.1177/0022487116685754.

- Gale, T., and T. Molla. 2017. “Deliberations on the deliberative professional: thought-action, provocations.” In Practice Theory and Education: Diffractive Readings in Professional Practice., edited by J. Lynch, J. Rowlands, T. Gale and A. Skourdoumbis, 247–262. London, England: Routledge.

- Gass, S., and A. Mackey. 2000. Stimulated Recall Methodology in Second Language Research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Gonski, D., K. Boston, K. Greiner, C. Lawrence, B. Scales, and P. Tannock. 2011. Review of Funding for Schooling: Final Report. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Harding, S. 2004. “A Socially Relevant Philosophy of Science? Resources from Standpoint Theory’s Controversiality.” Hypatia 19 (1): 25–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-2001.2004.tb01267.x.

- Le Donné, N. 2014. “ “European Variations in Socioeconomic Inequalities in Students’ Cognitive Achievement.” European Sociological Review 30 (3): 329–343.

- Lingard, B., and S. Rawolle. 2004. “Mediatizing Educational Policy: The Journalistic Field, science Policy, and Cross-field Effects.” Journal of Education Policy 19 (3): 361–380. doi: 10.1080/0268093042000207665.

- Luke, A. 2003. “After the Marketplace: Evidence, Social Science and Educational Research.” Australian Educational Researcher 30 (2): 87–107.

- Mills, C., T. Molla, T. Gale, R. Cross, S. Parker, and C. Smith. 2017. “Metaphor as a Methodological Tool: Identifying Teachers’ Social Justice Dispositions across Diverse Secondary School Settings.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 38 (6): 856–871. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2016.1182009.

- Moll, L. C., C. Amanti, D. Neff, and N. Gonzalez. 1992. “Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using a Qualitative Approach to Connect Homes and Classrooms.” Theory into Practice 31 (2): 132–141. doi: 10.1080/00405849209543534.

- Moll, L. C., and J. Greenberg. 1990. “Creating zones of possibilities: Combining social contexts for Instruction.” In Vygotsky and Education., edited by L. Moll, 319–348. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- NESSE 2012. Mind the Gap: Education Inequality across EU Regions. Brussels: European Commission.

- OECD 2010. PISA 2009 Results – Overcoming Social Background: Equity in Learning Opportunities and Outcomes. (Vol. II). Paris: OECD.

- Piketty, T. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-first Century. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

- Rapp, D. 2002. “Social Justice and the Importance of Rebellious Imaginations.” Journal of School Leadership 12 (3): 226–245. doi: 10.1177/105268460201200301.

- Sachs, J. 2001. “Teacher Professional Identity: Competing Discourses, competing Outcomes.” Journal of Education Policy 16 (2): 149–161. doi: 10.1080/02680930116819.

- Sachs, J. 2003. The Activist Teaching Profession. Buckingham, England: Open University Press.

- Sadker, M., and D. Sadker. 1995. Failing at Fairness. New York, NY: Touchstone.

- Said, E. 2000. Reflections on Exile and Other Essays. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Smyth, J. 2012. “The Socially Just School and Critical Pedagogies in Communities Put at a Disadvantage.” Critical Studies in Education 53 (1): 9–18. doi: 10.1080/17508487.2012.635671.

- Swartz, D. 2002. “The Sociology of Habit: The Perspective of Pierre Bourdieu.” The Occupational Therapy Journal of Research 22 (1 suppl): 61S–69S. doi: 10.1177/15394492020220S108.

- Taylor, C. 1994. “The politics of recognition.” In Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition., edited by A. Gutman, 25–73. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- UNICEF 2010. The Children Left behind, Innocenti Report Card 9. Florence, Italy: UNICEF.

- Wadlington, E., and P. Wadlington. 2011. “Teacher Dispositions: Implications for Teacher Education.” Childhood Education 87 (5): 323–326. doi: 10.1080/00094056.2011.10523206.

- Walzer, M. 1983. Spheres of Justice. Oxford, England: Blackwell.

- Wilkinson, R., and K. Pickett. 2009. The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. London, England: Allen Lane.

- Wrigley, T., B. Lingard, and P. Thomson. 2012. “Pedagogies of Transformation: Keeping Hope Alive in Troubled Times.” Critical Studies in Education 53 (1): 95–108. doi: 10.1080/17508487.2011.637570.