Abstract

Over the last 30 years higher education has seen a rise in new managerialism across all its activity, driven by neoliberal economic policy. Professional doctorates (PDs) have been part of this rise, increasing in number considerably and spawning a related interest in researching doctoral work. However, there have been few studies focused on how students develop an understanding of theory/theorisation and how supervision supports it. This paper reports on a research project involving interviews with supervisors from professional doctorate in education programmes in the UK, as a particular example of PDs in general, to explore the process of theorisation. Drawing on Bernstein, it shows how supervision, and wider programme design, are mediated by the increasingly managerial context of doctoral study. The study raises questions about the ways in which students and supervisors engage with both methodology and theory/theorisation in working together and subsequent implications for the quality of doctoral work.

Over the last three decades, higher education (HE) globally has experienced a radical change in the relationship between universities and state, driven by a tendency towards neoliberal economic policy (Lynch Citation2015). Neoliberalism invokes the notion of meritocracy with the related requirement for credentials to raise one’s social position (Marginson Citation2016) and has been accompanied by the rise of ‘new managerialism’ (Deem Citation1998), what Lynch (Citation2014) refers to as ‘the organisational arm of neoliberalism’. Deem defines new managerialism in broad terms as

attempts to impose managerial techniques, more usually associated with medium and large ‘for profit’ businesses, onto public sector and voluntary organisations … [including] … the marketisation of public sector services and the monitoring of efficiency and effectiveness through measurement of outcomes and individual staff performances. (Deem Citation1998, 49/50)

We see these changes to HE as ideological, in that they ‘serve to promote interests and maintain relations of power and domination’ (Deem and Brehony Citation2005, 218), especially the dominance of management over research and teaching and the control of working practices through performance management. Such practices are rooted in market-oriented business models and aimed at economic efficiency, using targets and auditing and because of this ideological perspective we adopt the term ‘new managerialism’ over the related concept of ‘new public management’ (Lynch Citation2014; Shepherd Citation2018). However, in practice the terms are probably interchangeable for our purposes, which is to provoke thinking about the way in which the organisation, management and implementation of professional doctorates (PDs) might affect candidates’ theorisation through supervisory processes.

PDs have been part of this change to HE in general, showing a rapid increase in numbers around the world, particularly in the UK, US and Australia. For example, Mellors-Bourne, Robinson, and Metcalfe (Citation2016) report that in England during the academic year 2015–16 there were approximately 8300 students on PDs of one sort or another, representing around 9% of all doctoral candidates at the time. Similar expansion of PDs has been seen elsewhere, Kot and Hendel (Citation2012) reporting that in the US, by 2005, 9.7% of all doctoral degrees were PDs with similar trends in Australia; though Malloch (Citation2016) notes a subsequent retraction in the range and number of programmes.

Not surprisingly, given these numbers, increasing emphasis has been placed on how the pedagogy of doctoral programmes should be operationalised and one might imagine that two elements are central to this, namely supervision and theorisation. Supervision forms the dominant pedagogical process for nearly all doctoral degrees; though PDs and, increasingly, PhDs tend to have modular elements with taught classes too. Meanwhile, theorisation is the process through which new ideas are both developed and then organised, as theory. Swedberg (Citation2012, Citation2016) refers to this theorisation as contexts of discovery and of justification, noting that the latter will depend on disciplinary knowledge and is relatively easy to learn. On the other hand, discovering theory is a messy, personal and less formalised process involving practical and personal knowledge leading to ‘inspiration’ to ‘produce something interesting and novel’ (Swedberg Citation2012, 6). Hence, metaphorically, ‘the context of discovery is where you have to figure out who the murderer is, while the context of justification is where you have to prove your case in court’ (ibid.).

Given the importance of supervision and theorisation, it is perhaps surprising that in their recent systematic review of literature on professional doctorate programmes Hawkes and Yerrabati (Citation2018) noted a relative paucity of work on the specifics of both. Despite this, some research has certainly tried to address these issues for doctorates in general. For example, Lee (Citation2008), Halse and Malfroy (Citation2010), Halse (Citation2011), McCallin and Nayar (Citation2012) and Fenge (Citation2012) have all focused on the characteristics of good supervision. Supervisory practices themselves have been the focus of other researchers, most notably Kiley and Wisker (Kiley Citation2015; Wisker Citation2015; Kiley and Wisker Citation2009) who have focused on theorising doctoral learning in terms of threshold concepts, seeing supervisory practices in terms of supporting students in the liminal state that they claim precedes the crossing of a conceptual threshold.

In exploring doctoral research, Hawkes and Yerrabati (Citation2018, 15) suggest that ‘over time, a focus on research methods and professionalism as the core content for a doctorate in education [has] become largely agreed upon in the literature’. However, in this article we illustrate that what is agreed on paper is not so straightforward in practice. Rather than trying to research effective practices per se, and using a sociological analysis rather than a psychological one, we show how supervision is mediated by, and reflects back on, the contemporary context of doctoral study. Because doctoral programmes are multifarious meaning that we cannot generalise to all of them, we focus here only on professional doctorates which are rooted in the social sciences. Furthermore, we take the Professional Doctorate in Education (EdD) programme as a specific example of these, which might, however, also include PDs in health and social care, social science and law, humanities/theology and generic professional practice (see Robinson Citation2018). Our choice of the EdD to illustrate these ideas is largely because of our own professional experience, but we note that EdDs are by some way the most common PDs, representing around 20% of all programmes in the UK and 7% in the US (Mellors-Bourne, Robinson, and Metcalfe Citation2016; Kot and Hendel Citation2012). We therefore ask what effect managerialism might be having, specifically for EdD students’ theorising and the forms of originality that they can develop for their theses, but aim to raise questions which we hope might form part of an ongoing debate about the process of doctoral learning in general; not least since Mellors-Bourne, Robinson, and Metcalfe (Citation2016, 14) have observed that any ‘structural distinction [from PDs] was reducing with the development of “new” forms of more structured doctoral programmes leading to PhD’.

The challenge of the EdD

For all doctoral routes, the decisive challenge for students is to produce a piece of research that is original. To be successful therefore, candidates, and their supervisors, need to understand the nature of originality in the context of the field in which their studies are set, something that is not as easy as it might sound and partially dependent on the discipline (Clarke and Lunt Citation2014). In the case of EdDs (and other professional areas too) there is the added complication that education can be seen as a field that encompasses a number of disciplines including sociology, psychology and philosophy, all of which provide a myriad of methods and ideas from which theorising is undertaken (Swedberg Citation2015). We detail our empirical study (interviews with EdD supervisors) below but, by way of introduction, one of our respondents, Gina, exemplifies this complexity as follows:

I mean, social relations and social actions and social practices and social theory are all so complex. It’s difficult to know whether one has found something or gained an insight that’s truly innovative … I think that’s quite difficult. So, it’s much more about how you do it and how you express it than about what it was that you actually did. (Gina)

One point here is how different this feels to the opposing and, we think, common notion that originality simply addresses a gap in the literature. The metaphor of a gap seems to work well in natural sciences where the focus is on identifying what is not known about an aspect of the physical world. Because of the realist ontological and (post-) positivist theoretical starting points of the scientific method, the focus of the research already exists – in the sense that there is some pre-existing aspect of this world that is being sought out for better understanding. However, in social sciences, when being examined using perspectives from sociology or sociocultural theory, research is often working with meaning – i.e. with the way in which people interpret social phenomena, what these mean to them and how this meaning affords social action – with the philosophical starting point usually rooted in constructionism, or critical realism. The job of the researcher is to rethink meaning in order to see aspects of this social world differently. There is no ‘gap’ to fill. Rather, as Swedberg (Citation2016) captures nicely in discussing Charles Sanders Pierce’s notion of abduction, ‘what you are after, he [Pierce] says, is something new, something that does not yet exist’ (p. 14, emphasis in original). Note that this does not mean that its existence simply has not yet been uncovered but that, ontologically, it is through the process of theorisation in the research, involving a ‘complex three-way transaction between teacher, text and student’ (Grant 2008, cited in Adkins Citation2009, 172) that the phenomenon is brought into existence. Thus, research in social sciences might better be understood as ‘Re-Search’; a combination of re-thinking meaning (theorising) through a process of searching (methodology). The latter is by no means easy, but the former often involves the generation of new ideas, a process which, arguably, presents the greater difficulty for students (Kiley Citation2015).

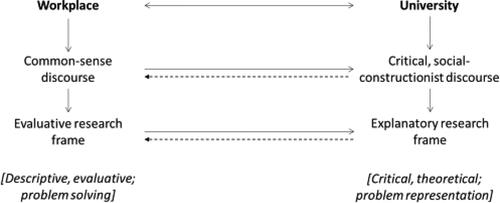

If this challenge presents itself to all doctoral students working in social fields, PD students face a second challenge rooted in the fact that they are usually well established professionals of some sort. Their workplaces do not share the same practices as the academic workplace – itself a professional field, but with very particular and strongly framed discourses – and hence students must navigate this transition from one to the other (Pratt et al. Citation2015; Pratt and Shaughnessy Citation2018). illustrates how we understand this challenge.

Workplaces are focused on action. As the left hand side of the diagram indicates, they operate on discourses which are common-sense in the manner described by Lave (Citation2011); that is, founded on meaning that is common to those in the workplace, being functional for professional activity. Research in this context usually aims to solve the kinds of practical problems that workplaces are involved in. We stress that describing professional practices this way is not to devalue such work. It is, rightly, what employees are paid to do, often for the public good. However, in the academic workplace of social sciences on the right hand side of our diagram, research is critical in nature and aims to explain social phenomena, not just to solve problems (though it may, of course). As Swedberg argues, to do so requires theory since research ‘should not reproduce the categories that people use in their everyday lives [common-sense thinking] but go beyond these and try to locate social facts’ (Swedberg Citation2016, 10, emphasis in original). The above argument is nicely captured in this quote from Diane:

It’s like they’ve [candidates] forgotten that intellectual debate is precisely that. It’s not about you as a teacher, it’s about how good you are at understanding and defending this idea and then how can you apply it to your practice. So I think if you can’t make that conceptual shift, you’re going to struggle doctorally because you’re always just going to be churning out your version of the world, without any kind of [pause] theorising. (Diane, interviewee)

Whilst Diane uses the word ‘conceptual’ we think of this as an epistemological shift, since the adjustment is in the epistemological stance towards the ideas that candidates are working with (Pratt and Shaughnessy Citation2018). The ‘struggle’ Diane describes is also why the right to left arrows in our diagram are dotted.

Thus, any doctorate in the social sciences requires theory to generate its originality, but more importantly requires a process of theorising through which one’s theory comes about – perhaps based on that already produced by others. Swedberg (Citation2016) notes that this process of theorising is not well-established in everyday practices and needs to be learnt. Moreover, it involves the analysis of one’s own observations within a disciplinary framework, including a sound knowledge of both how to think in the discipline and what one can think with; the theoretical ideas that are available to the researcher. As he makes clear in the context of sociology (though it applies beyond this too),

By theorizing I mean the process that comes before a theory is presented in its final form … [however] … in order to avoid a common misunderstanding, it should immediately be added that it is impossible to theorize without a sound knowledge of sociology. (Swedberg Citation2016, 7, emphasis added)

In developing this discussion we are aware that we are working with a particular version of theorising which some might disagree with in at least two respects. First, that it privileges the mind over other ways of coming to know the world such as embodied action in, say, dance or music. Second, it could be seen to assume the superiority of the particular form of knowledge associated with academia on the right hand side of our diagram rather than the kinds of professional knowledge on the left (Scott et al. Citation2004). Indeed, the relative appropriateness of different knowledge forms for a professional doctorate is well-rehearsed (see, for example, Costley Citation2013; Armsby, Costley, and Cranfield Citation2018). These are arguments that we cannot address in the space here, other than to say that we acknowledge them and hope their differences encourage the discussion that we are aiming to prompt through this paper.

Finally, in terms of the challenge of the PD, we return to the point at the start of this section, that doctoral study is carried out in an academic and professional world largely dominated by managerialism, features of which include (Lynch Citation2014; Deem and Brehony Citation2005): prioritization of private sector values of efficiency and productivity in the running of public bodies; focusing on product and output over process and input; importance of targets measured through audit and quality of service delivery; the widespread use of performance indicators and benchmarking; emphasising management above other activity; and, the use of quasi markets with students envisaged as customers. Moreover, as Deem and Brehony (Citation2005) point out, managerialism ‘emphasis[es] the primacy of management above all other activities’ leading to ‘the legitimation of management for its own sake’ – a point which Pollitt (1993, cited in Deem and Brehony Citation2005) claims entitles it to the prefix ‘new’.

In the UK HE context, these features of new managerialism can been seen in the drive for efficiency and casualized contracts leading to increasing pressure on staff (Morrish Citation2019), and increased accountability and ‘customer’ focus which have led to rising numbers of student appeals (Office of the Independent Adjudicator Citation2018), although specific numbers for PGR candidates are less clear. In such circumstances, where product dominates process and outcomes are measured and benchmarked, doctoral students’ success has increasingly been constructed as a ‘problem’ of supervision which can be solved through better management (Bastalich Citation2017).

The empirical study

The field work reported here is part of a research project funded by the Society for Research into Higher Education (SRHE) (Pratt and Shaughnessy Citation2018), the overarching focus of which was to understand more fully doctoral supervisory processes; specifically, how supervisors can support the development of critical voice and theorisation with EdD students.

The study was framed in a social constructionist epistemology and data were generated by both authors from three sources, namely supervisor interviews, student interviews and documentary analysis from the hosting universities. Here, we draw on the first and, briefly, the last of these only.

Data sources

Through our contacts in the UK EdD Directors’ National Network we found five institutions, purposively chosen to represent a range of EdD programmes – see for type/geographical details. Supervisors were contacted via their programme directors and took part on a voluntary basis, resulting in seventeen participants across 5 universities. We undertook an individual, face-to-face, semi-structured interview with each of them aiming to discuss the ways in which they work as supervisors with EdD students. These took between 60 and 90 minutes each, meaning that we had a total of approximately 20 hours of recording which was then professionally transcribed.

Table 1. Participant pseudonyms and university types/geographies.

To try to mitigate for the difficulty of articulating one’s own practice, much of which is implicit, we used a pre-interview task where we encouraged supervisors to reflect on recent discussions with students and used the early questions in the interview to help them articulate this. By first gaining an account ‘of’ practice we were then better able to ask participants to account ‘for’ it (Mason Citation2002).

In addition to the interview data we also undertook an analysis of programme materials and websites. We requested documentation – EdD programme specifications, student handbooks and research development programmes – to allow us to understand the parameters within which participants work. We also examined websites to get a sense of the content and process for each programme and how it promoted research development.

Analysis

We undertook an inductive, thematic analysis (after Miles, Huberman, and Saldana Citation2013) of all the data, informed by our reading of the literature, to examine supervisory practices, the development of critical voice and processes of theorisation. Interviews were analysed through repeated readings and discussion between the authors in order to construct themes (Charmaz Citation2006) that were considered relevant to the research questions and which were important to the participants. nVivo (v11) was used to manage the data and to conduct text searches. The use of Bernstein as a theoretical frame – see below – was brought to the data retrospectively and not used for initial coding and theme development.

The research was guided by the BERA Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research (British Educational Research Association Citation2018), and consent was gained from both authors’ employing universities. In particular, participants were made aware that whilst we could anonymise them in our writing, the relatively close-knit world of EdD programmes meant that others might recognise their voice in the data.

Responses to the challenges of the EdD

How, then, have the programmes we worked with responded to the challenges of originality and epistemological shift in an increasingly managerial HE world, and what effects have these had on supervision and the support for students’ theorisation? Our analysis focuses on three ideas, efficiency, expertise and marketability, which grew reciprocally alongside our interest in managerialism as we tried to understand and interpret the interview data. It also draws theoretically on Bernstein’s (Citation1990, Citation2000, Citation2003) ideas about pedagogic relations; that is the formation of relationships that ‘shape pedagogic communications and their relevant contexts’ (Bernstein and Solomon Citation1999, 267). In the spirit of Swedberg’s (Citation2016) context of discovery we use Bernstein’s ideas selectively and heuristically, alongside our data, to theorise EdD supervision; rather than seeing his theorisation as any kind of static mechanism for analysis. In particular we focus on his (Bernstein Citation2003) ideas about two types of pedagogic practice – invisible and visible – and three rules of pedagogic approach – hierarchical, sequencing and criterial rules. In all these, classification and framing are key ideas; framing referring to the agency of different actors acting within the programme structures and classification referring to the relations between different knowledge categories. We assume that readers of this journal will be broadly familiar with Bernstein’s ideas and note that this approach follows in the footsteps of others interested in theorising doctoral study (Singh, Atweh, and Shield Citation2002; Crossouard Citation2013; Adkins Citation2009), referring the reader to Singh (Citation2002, Citation2017) for a more general exposition.

Managerialism and efficiency

The managerial imperative of efficiency has contributed to Robinson (Citation2018, 100) noting, in relation to professional doctorates, that

Within some HEIs, attempts are being made to counteract the financial implications of small cohorts by, for example, combining the teaching of candidates in such cohorts with teaching on other programmes. While this helps to address the financial burden of small cohorts, it also reduces the known benefits of face-to-face cohort programme delivery …

This drive for efficiency was explicitly evident in the responses from our participants. For example,

over time on our EdD the taught aspect has got increasingly packed into the smaller, smaller space to give as much space as we can for the thesis. So, at most three years on the thesis, by packing everything up. But then the question is have we lost the theory in the process? We definitely have by packing it up to be worried about the completion times, we’ve dropped bits. (Ingrid)

The aim here is, in Bernstein’s terms, to more strongly classify the taught content by delineating specific topics, but particularly to strengthen the framing through making choices about sequencing and tightening the pacing – the rate at which the sequentially organised material of the programme is completed. An increasingly efficient, visible pedagogy is brought about through timetabling groups together to generate larger cohorts focused on specific topics. Importantly, these are not simply changes to ‘what’ is experienced ‘when’, but to the nature of that experience since, as Adkins (Citation2009, 171) notes, ‘framing focuses attention on the internal logic of this practice’ and thus alters the pedagogical relationships. As Ingrid makes clear above, the motive is ‘completion rates’; getting students through the programme in a timely, cost-efficient manner. In her interview, Amy argues that marching students through time/status like this leads to supervision that is

not flexible, wanting to apply the same approach to every single student. I’m aware that has an efficiency to it but only if it’s suitable, which given what we said at the beginning about the context of EdD students’ lives, I just don’t think that’s appropriate.

Similarly, Kath suggests that

I think [students] want this magical book and they always say, “How did you find your theorist?”. I’m like “what do you mean?”. “Did you just pick one?” and I’m like “no!”. And there’s this notion of “I’ve got to pick a theorist, I’ve got to pick a theory, I’ve got to choose something and if I do it in my first assignment, I can then, whether it’s right or not …”

Interviewer: Then it’s linear and that it’s uncomplicated …

K: It’s really not, it’s a messy process

What these comments seem to point to is a tension for supervisors. The internal logic of tightly framed, explicit, institutional time structures, for doctoral completion to drive outcomes, seem at odds with their own experience and their knowledge of what it takes to theorise social practice. Though they are required to operate within their university frameworks, they seem aware that in an ideal world it might be better to work with a less visible pedagogy which, rather than placing the emphasis on external performance, product and time-checks,

presupposes a long pedagogic life. Its relaxed rhythm, its less specialized acquisitions, its system of control entail a different temporal projection relative to a visible pedagogy … (Bernstein Citation2003, 81)

Indeed, in summarising the difference between these pedagogies Bernstein argues that they ‘construct different concepts of the [student’s] development in time which may or may not be consonant with the concept of development held by the [institution]’ (ibid.), a claim clearly illustrated in Kath’s interview as she talked about her supervision and her recent experiences of completing her own doctorate:

It’s a lot of uncovering, discovering, trying things, ideas, connecting things and I don’t think you can have positionality necessarily from day one. Professionally you can know who you are and what you do but I think that’s a longer journey than we make it. … personally, I was playing catch up with theory compared to where I was in practice, and I needed longer before I could arrive at my positionality. I couldn’t just do it in a first year module and “oh my position is this” … I think that takes a while. (Kath)

Note how Kath’s comments illustrate the challenge of the epistemological shift that we drew out at the start of this paper. She points to the challenge of catching up theoretically with where her professional practice is, as well as pointing to the need for taking one’s time, and the potential danger of the increasingly visible – more explicitly framed – pedagogy required by universities of their staff in order to get students through in a timely manner (Bastalich Citation2017). In ‘packing it up’ and ‘dropping bits [of theory]’ (Ingrid), ‘applying the same approach to every student’ (Amy), and having to ‘do it in a first year module’ (Kath) we raise a question for our concluding section about the effects of efficiency on students in terms of working with theory, and hence on forms of originality.

Managerialism and expertise

Considering the effects of efficiency leads to a second outcome from the data relating to the expertise of supervisors in relation to managerialism. Gina notes that:

I’m supervising people whose work interests me, but I’m not an expert in the topic. So, I’m supervising somebody who’s in a social work team and who’s done some research with gypsy people who are in a settled community. It’s quite interesting, but it’s not my area of expertise. (Gina)

We wonder what the effect of this lack of expertise is on student supervision and in particular on the ability of supervisors to support and promote theorising. One response to this question is provided by Larry, who makes a virtue of the eclectic nature of his supervisions, stating that:

when I look at my completion record and I look down the list of topics that are represented within that completion record, it’s eclectic to say the least! And I look at it and I think okay, how the hell did I ever get anybody through, about leadership training, I’ve had one go through around nursing, I’m about to have one hopefully submit around occupational therapy, somebody who’s done leadership training for businesses. It’s not my field at all … I look at things like that and think my supervision record is really good but it’s very eclectic. (Larry)

Larry’s position, characterised by Franke and Arvidsson (Citation2011) as a ‘research relation-orientation’, is one in which the supervisory focus is on ‘the doctoral student’s learning process, the supervisor’s different activities and participation in the supervisor–doctoral student relationship’ (ibid., p. 14), but not on a shared project of research itself. Larry accounts for the validity of this position as follows:

I may not be the expert in that area, what I am good at is guiding people to writing a good thesis and I’m good at questioning them about the quality of their data or the methodology they’re choosing or raising those questions with them, almost as if I was an examiner of their work. Not in an aggressive way that examiners are, but that critical disposition, and it’s modelling, I think it’s really important. (Larry)

We agree that expertise in guiding process is important, but strong theoretical expertise implies strong disciplinary classification – in the form of what Bernstein (Citation1999) refers to as vertical knowledge structures – allowing supervisors to identify subtle distinctions in ideas, and hence to support students in seeing originalities. Without this the danger is that such fine-grained distinctions in the ideas of the subject are not understood sufficiently to allow students to see these opportunities and the work remains theoretically naive. As Adkins (Citation2009) notes, this is particularly challenging in projects which are cross-disciplinary (as PDs in social fields often are). Whilst strong disciplinary expertise allows supervisors to distinguish originality, the need to work across disciplines implies a weakening of classification horizontally; that is in breaking down the barriers between disciplines and working between them (Adkins Citation2009). Moreover, it is not simply an issue of classification but of framing too, noting that ‘the relationships [between teacher, text and student] must take their cue from the nature of the knowledge required rather than those prescribed through strong disciplinary identities’ (ibid. 173). Thus the forms of communication used between participants, the pace at which it moves and the criteria used to judge students’ thinking all need to be handled sensitively.

In identifying the complexity of supervision like this, one thing we think it points to is the relative comfort of working with methodology, familiar terrain for most supervisors, regardless of expertise in specific social theories. Similarly, whilst students enter doctoral study from many different disciplinary backgrounds and may be experiencing social theory for the first time, all will be familiar with working methodologically to some extent through previous degrees. Thus, whilst the social theories most commonly used in the particular field of study may be unfamiliar to both parties, the shared idea that methodology is a key component of research provides common ground for supervision. This raises a second question regarding the effects of managerialism: might it foreground methodological thinking over social theorising and, hence, encourage doctoral work which lacks the kinds of explanatory ideas needed to avoid simply reproducing the categories that students already use in everyday practice?

Managerialism and marketability

Not only does the comfortable familiarity of methodology over social theory lead us to examine the balance between each, it also leads us to think about what is marketable in the contemporary climate of the HE sector to a customer base of professional educators. As Debbie notes:

What we get is people doing the EdD who have done a lot of reports for governors and they may have done their Masters through bits and pieces of SENCo [Special Educational Needs Coordinators] courses or the Masters scheme when that was running and so on and so forth. Even PGCE credits of course have crept through into Masters and then forward in terms of EdD. So, they’re building on work that doesn’t necessarily, easily lead them into the nature of theorising that’s required at doctoral level. (Debbie)

As Watts (Citation2009) has pointed out, for professionals, working with theory can be threatening in potentially denying ‘the validity of their own experience-based professional craft knowledge’ (p. 689). This point is captured neatly by Amy, who states that:

I think theory really terrifies a lot of Prof Docs that I’ve worked with because it’s something that’s quite new … there is a sense that practical and professional practice is where I’m comfortable and “oh yes, to work at Level 8 and to get a doctorate, I’d better do this thing called theory”. And it’s met with some fear in some respects because it might be something so different to and new to what they do on a day to day basis, which is probably the real motivation why they’ve come to the doctorate, for some. (Amy)

As a result, for some institutions a decision has clearly been made that what is attractive to students is something that maintains the familiarity of their professional work, clearly starting, and perhaps forever remaining, on the left-hand side of to delay, or avoid, any epistemological shift. This can be seen in the emphasis of the text of programme websites where, for example, the key points of the course areFootnote1:

Focusing on an independent study aimed at both personal and professional development;

Gaining skills in research in order to understand work more clearly, benefiting the organisation and the wider community in which they work.

Having real impact through a programme that is challenging intellectually and which supports thinking about professional practice through doing a major and robust research project in the practice setting.

In contrast we see other programmes foregrounding theorisation as the key element of doctoral work, for example:

We will make sure you get taught the skills you will need to articulate and cross-examine the key issues of education policy, the way social institutions change, and implications for multiple and fluid professional identities on practice in a global context.

The programme focuses on the relationship between knowledge, theory and practice and you will be able to show how it is possible to make and influence change.

Indeed, Gina described how she rewrote her EdD programme, framing it more strongly to produce a greater focus on theorising because ‘I thought we actually need modules that push people into engaging with theoretical positions’. This appears challenging for her in terms of the criterial rules governing doctoral programmes laid down by the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA Citation2014) because:

the criteria are not articulated in the way that foregrounds theoretical engagement at all. But I just think how do you think about some of those things in a really robust and well-articulated way, unless you can rely on the underpinning of whatever it is that you’re working with? (Gina)

However, whilst some programmes and their staff present this argument for more explicit reference to theory, as we argued above it follows that such practices are likely to make the pedagogy more visible through invoking issues of sequencing and pacing and imposing time frames on students. This might be why Kath is moved to say that:

we’ve talked quite a lot here in our teams around this idea of the tail wagging the dog with theory on professional doctoral students, because there is a sense that the theory they’re using and wanting to engage in is just the theory we’ve presented them with, rather than really having time to explore what’s appropriate for them to make sense of and unpick the professional stuff [with].

I understand why that would happen because it’s quite a big, scary thing to go and do, is to enter this world where there’s so much [theory] and it’s challenging and it’s difficult and you’ve got to go through stuff and reject it and make sense of it and then maybe not even use it. How do we get that right … are we then just going to read assignments and then start to look at transition vivas where people are forcing theory in their work? (Kath)

Her comment on the need to reject ideas and having the courage to experiment and fail is, we think, interesting in terms of a visible pedagogy which ‘will always place the emphasis on the performance of the [student], upon the text the [student] is creating and the extent to which that text is meeting the criteria’ (Bernstein Citation2003, 70 emphasis in original). Taking backwards steps is much easier where work is private and low-stakes; and correspondingly more difficult when public and high-stakes. Moreover, as Shahjahan (Citation2020, 5) makes clear, in the constant ticking of

clock time (e.g. scheduled time, contract time, project time), structured temporal constraints become temporal norms, shaping ways of knowing/being. More specifically, temporality is experienced as both an inwardly ‘gaze of Other’ and/or outwardly existing ‘Being for others’.

Students who must succeed in the gaze of Other at a particular moment in time might be unwise to publicly illustrate any failure and hence to experiment at all. Better, perhaps, to simply ‘force theory into their work’ particularly if they can rely on it being appropriate because it was the ‘theory we presented them with’ (Kath).

All this raises a third question for us; namely, how the need to market EdD programmes to professional educators and retain them thereafter affects the shape of programmes and of pedagogy.

Time to think?

In each of the three analytic sections above we have raised a question which gives us cause to think about the shape of the programmes we worked with. New managerialism produces actual effects on people and programmes, and is hard to resist (Shahjahan Citation2020; Deuchar Citation2008); notwithstanding the fact that it may, of course, also be beneficial in many respects too. We deliberately therefore hold back from judging programmes, though we do note the caution of Mellors-Bourne, Robinson, and Metcalfe (Citation2016, 65) who suggest that ‘perceptions of quality [with PDs] remain an issue, particularly within HE (where the PhD tends to be seen as the ‘gold standard’ doctoral qualification), although this may vary by subject’.

To some extent, programme designs and the regulatory frameworks around programmes are matters of choice, as too are the aims and expected outcomes – at least within an interpretation of the QAA guidance. However, one advantage of a Bernsteinian analysis is that it exposes some of the structural issues that underpin such choices and, in this case, the potential effects of managerialism and increasing efficiency on the nature of supervision and support for students in theorising their work.

One such issue is that in modular components the need to consolidate programmes and increase efficiency has meant a tendency for teaching to become more strongly framed so that it can be credentialised and explicitly timed; a course to pass (through) rather than a transformational experience. At the thesis stage too, programmes are under pressure to become increasingly fast-paced and for this pacing to be made explicit through structured time-checks, imposed and monitored centrally by the university and often common to all doctoral programmes regardless of type. This ‘gaze’ from the centre holds supervisors to account, ensuring they are made responsible in terms of ‘their’ students’ success (Rose Citation1999), but with little or no space to argue about the legitimacy of the process. In making these time structures more explicit and imposing responsibility for them on supervisors, pedagogy becomes more visible such that:

Time is symbolically marked as the [student] progresses through a series of statuses which define her/his relation not only to [supervisors] but also to other [students]. The implicit theory of instruction held by [supervisors] which regulates their practice constructs age-specific communications/acquisitions. The [student] is developed in, and by, a particular construction of time. (Bernstein Citation2003, 81, emphasis added)

The illustrations from our data have given a glimpse of this construction and have suggested that students might be less likely to have the ‘long pedagogic life’ with its more ‘relaxed rhythm’ that Bernstein (ibid.) ascribes to an invisible pedagogy and which, arguable, are necessary to allow students the time to theorise in ways which are most appropriate for their work.

At the same time, whilst we saw that Gina had tried to focus more on social theory through stronger framing and classification, elsewhere this has been lost,

… and the bits that have hit the floor are the bits that most of us as academics acknowledge as being part of doctorate-ness. Because the methods we could teach anywhere, I mean I really believe that. I’d quite like them to be challenged a little bit more with some more theory. (Ingrid)

This selective loss is perhaps no surprise since methodology courses have two advantages over those relating to theory. First, they are more readily packaged up into neat parcels: methodological approach; ethical issues; methods themselves etc. Second, as Ingrid baldly states, it is easier to find supervisors with the expertise to teach on them and to find students from ‘anywhere’ in terms of different programmes, operating under a common language of methodology, even if different outcomes are expected. As staffing is thinned out and theoretical expertise is scarcer, so methodology becomes the one area that it remains possible for all supervisors to work with across the entire student body.

We acknowledge, of course, the vital role of methodological understanding in a doctoral programme. However, as Swedberg pointed out at the start of this paper, originality depends on having a strong theoretical framework through which one’s observations can be filtered in order to bring fresh explanatory insights into practice. The results of our study suggest that theorisation is placed under pressure by the ideological demands of managerialism, which emphasise the need to make doctorates attractive to their customer base whilst utilising more efficient delivery. It therefore illustrates a connection between managerialist control of doctoral programmes and the potential quality of theorisation, and thus a potential threat to criticality and originality.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the help of our colleague Peter Kelly in developing the idea of an epistemological shift in doctoral students’ thinking. We also thank Gill Crozier for providing helpful feedback on an earlier draft of the paper and the two blind reviewers who provided excellent advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For ethical reasons, avoiding an online search that would identify the institution, we have re-phrased the text in both this quote and the one that follows, staying as close as possible to the original meaning.

References

- Adkins, B. 2009. “PhD Pedagogy and the Changing Knowledge Landscapes of Universities.” Higher Education Research & Development 28 (2): 165–177. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360902725041.

- Armsby, P., C. Costley, and S. Cranfield. 2018. “The Design of Doctorate Curricula for Practising Professionals.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (12): 2226–2237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1318365.

- Bastalich, W. 2017. “Content and Context in Knowledge Production: A Critical Review of Doctoral Supervision Literature.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (7): 1145–1157. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1079702.

- Bernstein, B. B. 1990. The Structure of Pedagogic Discourse. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Bernstein, B. B. 1999. “Vertical and Horizontal Discourse: An Essay.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 20 (2): 157–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01425699995380.

- Bernstein, B. B. 2000. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: Theory, Research, Critique. Rev. ed. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Bernstein, B. B. 2003. Class, Codes and Control. The Structuring of Pedagogic Discourse. Vol. IV. London: Routledge.

- Bernstein, B. B., and J. Solomon. 1999. “‘Pedagogy, Identity and the Construction of a Theory of Symbolic Control’: Basil Bernstein Questioned by Joseph Solomon.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 20 (2): 265–279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01425699995443.

- British Educational Research Association. 2018. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. 4th ed. London: BERA.

- Charmaz, K. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London, UK: Sage.

- Clarke, G., and I. Lunt. 2014. “The Concept of ‘Originality’ in the Ph.D.: How is It Interpreted by Examiners?” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 39 (7): 803–820. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.870970.

- Costley, C. 2013. “Evaluation of the Current Status and Knowledge Contributions of Professional Doctorates.” Quality in Higher Education 19 (1): 7–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2013.772465.

- Crossouard, B. 2013. “Conceptualising Doctoral Researcher Training through Bernstein’s Theoretical Frameworks.” International Journal for Researcher Development 4 (2): 72–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRD-05-2013-0007.

- Deem, R. 1998. “New Managerialism’ and Higher Education: The Management of Performances and Cultures in Universities in the United Kingdom.” International Studies in Sociology of Education 8 (1): 47–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0962021980020014.

- Deem, R., and K. J. Brehony. 2005. “Management as Ideology: The Case of ‘New Managerialism’ in Higher Education.” Oxford Review of Education 31 (2): 217–235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980500117827.

- Deuchar, R. 2008. “Facilitator, Director or Critical Friend?: Contradiction and Congruence in Doctoral Supervision Styles.” Teaching in Higher Education 13 (4): 489–500. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510802193905.

- Fenge, L. 2012. “Enhancing the Doctoral Journey: The Role of Group Supervision in Supporting Collaborative Learning and Creativity.” Studies in Higher Education 37 (4): 401–414. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.520697.

- Franke, A., and B. Arvidsson. 2011. “Research Supervisors’ Different Ways of Experiencing Supervision of Doctoral Students.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (1): 7–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903402151.

- Halse, C. 2011. “Becoming a Supervisor’: The Impact of Doctoral Supervision on Supervisors’ Learning.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (5): 557–570. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.594593.

- Halse, C., and J. Malfroy. 2010. “Retheorizing Doctoral Supervision as Professional Work.” Studies in Higher Education 35 (1): 79–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902906798.

- Hawkes, D., and S. Yerrabati. 2018. “A Systematic Review of Research on Professional Doctorates.” London Review of Education 16 (1): 10–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.16.1.03.

- Kiley, M. 2015. “I Didn’t Have a Clue What They Were Talking About’: PhD Candidates and Theory.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 52 (1): 52–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2014.981835.

- Kiley, M., and G. Wisker. 2009. “Threshold Concepts in Research Education and Evidence of Threshold Crossing.” Higher Education Research & Development 28 (4): 431–441. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360903067930.

- Kot, F. C., and D. D. Hendel. 2012. “Emergence and Growth of Professional Doctorates in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Australia: A Comparative Analysis.” Studies in Higher Education 37 (3): 345–364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.516356.

- Lave, J. 2011. Apprenticeship in Critical Ethnographic Practice. London: University of Chicago Press.

- Lee, A. 2008. “How Are Doctoral Students Supervised? Concepts of Doctoral Research Supervision.” Studies in Higher Education 33 (3): 267–281. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802049202.

- Lynch, K. 2014. “New Managerialism: The Impact on Education.” Concept 5 (3): 11.

- Lynch, K. 2015. “Control by Numbers: New Managerialism and Ranking in Higher Education.” Critical Studies in Education 56 (2): 190–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2014.949811.

- Malloch, M. 2016. “Trends in Doctoral Education in Australia.” In International Perspectives on Designing Professional Practice Doctorates: Applying the Critical Friends Approach to the EdD and Beyond, edited by V. A. Storey, 63–78. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Marginson, S. 2016. “High Participation Systems of Higher Education.” The Journal of Higher Education 87 (2): 243– 271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2016.11777401.

- Mason, J. 2002. Researching Your Own Practice. The Discipline of Noticing. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- McCallin, A., and S. Nayar. 2012. “Postgraduate Research Supervision: A Critical Review of Current Practice.” Teaching in Higher Education 17 (1): 63–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2011.590979.

- Mellors-Bourne, R., C. Robinson, and J. Metcalfe. 2016. Provision of Professional Doctorates in English HE Institutions. Cambridge: Careers Research & Advisory Centre (CRAC) Ltd.

- Miles, M. B., A. M. Huberman, and J. Saldana. 2013. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Morrish, L. 2019. Pressure Vessels: The Epidemic of Poor Mental Health among Higher Education Staff. Oxford, UK: Higher Education Policy Institute.

- Office of the Independent Adjudicator. 2018. Annual Report 2018. Reading, UK: Office of the Independent Adjudicator. https://www.oiahe.org.uk/media/2315/annual-report-2018.pdf.

- Pratt, N., M. Tedder, R. Boyask, and P. Kelly. 2015. “Pedagogic Relations and Professional Change: A Sociocultural Analysis of Students’ Learning in a Professional Doctorate.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (1): 43–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.818640.

- Pratt, N., and J. Shaughnessy. 2018. “Supervision of Professional Doctoral Students: Investigating Pedagogy for Supporting Critical Voice and Theorisation.” Society for Research into Higher Education (SRHE). http://www.srhe.ac.uk/downloads/reports-2016/Pratt-Shaughnessy-Research-Report.pdf.

- QAA. 2014. UK Quality Code for Higher Education. The Frameworks for Higher Education Qualifications of UK Degree-Awarding Bodies. Gloucester: Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA).

- Robinson, C. 2018. “The Landscape of Professional Doctorate Provision in English Higher Education Institutions: Inconsistencies, Tensions and Unsustainability.” London Review of Education 16 (1): 90–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.16.1.09.

- Rose, N. 1999. Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Scott, D., A. Brown, I. Lunt, and L. Thorne. 2004. Professional Doctorates, Society for Research into Higher Education. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Shahjahan, R. A. 2020. “On ‘Being for Others’: Time and Shame in the Neoliberal Academy.” Journal of Education Policy 35 (6): 785–811. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1629027.

- Shepherd, S. 2018. “Managerialism: An Ideal Type.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (9): 1668–1678. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1281239.

- Singh, P. 2002. “Pedagogising Knowledge: Bernstein’s Theory of the Pedagogic Device.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 23 (4): 571–582. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0142569022000038422.

- Singh, P. 2017. “Pedagogic Governance: Theorising with/after Bernstein.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 38 (2): 144–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1081052.

- Singh, P., B. Atweh, and P. Shield. 2002. “Designing Postgraduate Pedagogies Connecting Internal and External Learners.” In Australian Association for Research in Education Conference. ‘Creative Dissent: Constructive Solutions.’ Parramatta, Australia.

- Swedberg, R. 2012. “Theorizing in Sociology and Social Science: Turning to the Context of Discovery.” Theory and Society 41 (1): 1–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-011-9161-5.

- Swedberg, R. 2015. The Art of Social Theory. Woodstock, UK: Princeton University Press.

- Swedberg, R. 2016. “Before Theory Comes Theorizing or How to Make Social Science More Interesting.” The British Journal of Sociology 67 (1): 5–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12184.

- Watts, J. H. 2009. “From Professional to PhD Student: Challenges of Status Transition.” Teaching in Higher Education 14 (6): 687–691. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510903315357.

- Wisker, G. 2015. “Developing Doctoral Authors: Engaging with Theoretical Perspectives through the Literature Review.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 52 (1): 64–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2014.981841.