Abstract

In this paper, we show how mobile drawing methodologies can bring the dynamic, relational and non-representational qualities of landscape encounters to the foreground. The research paper discusses a mobile drawing project that took place in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. The project entitled ‘Taxi Guff-Gaff’ invited participants to undertake a collaborative drawing and conversational journey. Mobile drawing together on a bumpy taxi journey required artist participants to move together and literally ‘pay attention to the moment at hand’. In so doing it produced imagery that foregrounds the inherent dynamic quality of all our landscape encounters. We propose that mobile drawing offers an immersive way to relate to the urban landscape and each other and can open up spaces of landscape research that centre on speculative forms of thinking, being, drawing and conversation.

Introduction

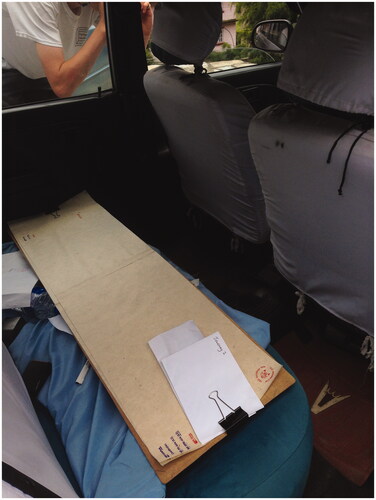

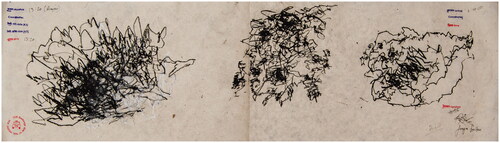

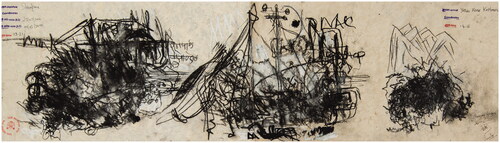

This research paper reflects on the process and outcomes of a mobile drawing project that took place in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Originally this project was conceived as an inclusive arts intervention for the Kathmandu Triennale 2017. Yet it is increasingly evident that the practice and findings of inclusive, participatory and performance artists are of relevance to experimental forms of landscape research (see also Frederick, Citation2021; Hogg, Citation2018). Prior research has proposed that artist-driven work should be understood as a ‘potential ingredient’ of landscape planning (Crawshaw, Citation2018) and it has been suggested that drawing outdoors and allowing the elements to take some control can be a way of opening up a dialogue with landscape (Bullen, Fox, & Lyon, Citation2017). However, such insights have not been explored within a global south context in landscape research. With this in mind, this paper explores the relevance of an artist-driven project entitled ‘Taxi Guff-Gaff’. The project invited Nepali artist participants to undertake a drawing and conversational journey. ‘Guff-Gaff’ in Nepali can mean stories and things that you share. A series of motion drawings using pen and charcoal were made on local handmade Lokta paper, collaboratively in the back seats of four taxis (). Further details of the approach this project took are outlined in the method section below.

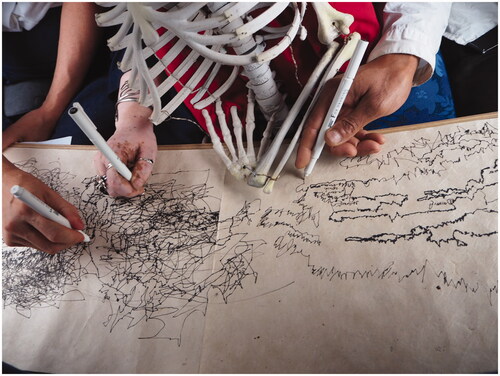

Figure 2. Three hands drawing in the back of the taxi, note that artist Ashmina Ranjit is carrying a skeleton as part of another project on the ever-present nature of death in Nepal.

Drawing on the move: an introduction

“A drawing is simply a line going for a walk.” Paul Klee

Drawing in landscape research has a long important history with accurate drawing a fundamental necessity in landscape planning and design (Boults & Sullivan, Citation2020). Forms of hand drawing are also recognised as important for initial site assessment and for drawing attention to aesthetic and dynamic aspects of the landscape that are hard to capture through purely representational approaches (Hutchisom, Citation2019). Meanwhile, prior interdisciplinary reviews of drawing as a social research method recognise that drawing has a number of advantages over purely verbal techniques of research. Thus drawing is increasingly being used as a research method across a wide array of disciplines and settings, for a diversity of outcomes (Causey, Citation2016; Hawkins, Citation2021; Leavy, Citation2018; Lyon, Citation2020; Macpherson et al., Citation2016; Mitchell, Theron, Stuart, Smith, & Campbell, Citation2011; Roberts & Riley, Citation2014; Rogers, Citation2010).

Drawing can be used as a mode of enquiry, a method of learning and as a tool of thought (Kantrowitz, Fava, & Brew, Citation2017). Drawing together can also enhance rapport, open up new conversations, enhance the expression of tacit knowledge, help explore issues that are difficult to speak about, access those people with low verbal literacy and encourage shared spaces of reflection (Lyon, Citation2020; Prosser & Loxley, Citation2008). Drawing together has been shown to help researchers and participants transgress convention, produce intersubjective knowledge and navigate multiple and contradictory identities (Bochner & Ellis, Citation2003). Drawing, compared to other visual methods, has the added benefit of being relatively low-tech, requiring only a paper and pencil.

Drawing has a long history in landscape research and is now also a commonly used method in social research. However, prior work on drawing on the move as a research method is very limited. It has been proposed that drawing outdoors with the elements can be a way of opening up a creative dialogue with landscape (Bullen et al., Citation2017) and that collective drawing with other people promotes novel dialogic forms (Clarke & Foster, Citation2012; Rogers, Citation2010). Recognised barriers and limitations to drawing as a collaborative method include: participants’ preconceived ideas about ‘what drawing is’ and fears around the representational abilities of the drawer (Lyon, Citation2020). There are also significant issues regarding how drawing can be used and interpreted within any project, with a variety of competing paradigms and interpretation frameworks being proposed (Mair & Kierans, Citation2007; Mitchell et al., Citation2011).

Drawings can be treated as clues that guide us on a journey of understanding. However, not all drawing as a research method needs to be interpreted as representational (Bullen et al., Citation2017). For example, thinking with images has been shown to aid consideration of the affective, embodied and non-human elements of urban landscapes (Latham & McCormack, Citation2009). This project builds on this observation and the non-representational qualities of mobile drawing. Non-representational theory is an umbrella term under which sit an array of theoretical ideas borrowed from fields as diverse as performance studies, cultural geography, the sociology and anthropology of the body, emotion, affect and the senses. Non-representational theories are relevant to landscape research because they draw our attention to the body and to the present moment (Macpherson, Citation2010). They help illustrate the fact that events and encounters in the world are constituted through forms of relational-materialism (for there is no pre-formed individual human subject that sits outside its relations with the earth and each other). Thus as embodied subjects we are ‘…constituted at the interface with objects and environments rather than existing in separation from them’ (Macpherson, Citation2010, p. 4). This complicates humanistic and individual notions of subjectivity in landscape research which often stem from Western traditions of thought. For Vannini:

“….what truly distinguishes non-representational research from others is a different orientation to the temporality of knowledge, for non representationalists are much less interested in representing an empirical reality that has taken place before the act of representation than they are in enacting multiple and diverse potentials of what knowledge can become afterwards.” (2015, p. 12)

This is important, in relation to understanding the methodological potential of forms of mobile drawing in landscape research. Drawing in an uncontrollable environment with a variety of other human and non-human forces (the road, the car, the participants, the bumps, the hills) all impact the nature of the conversation, the drawings and the forms of subjectivity that are brought into being. This is not a problem with the method that is to be overcome. Rather drawing on the move in a bumpy context may help produce new forms of knowledge and dialogue about the past, present and future, with each other and the landscape. It is a method that allows landscape agency to ‘surface’ through the drawing in a way that other representational drawing methods or conversations would not. Thus from the outset, the road, the car and the landscape were all recognised as ‘participants’ in this project. In this way drawing on the move was recognised as a method that had the potential for involving the ‘opening of subject positions to nonhuman and inhuman forces’ (Yusoff, Citation2015 p. 1).

This research paper, with a focus on drawing on the move in a taxi journey setting, builds on these initial theoretical observations. It also expands upon explorations of drawing as a research method (Lyon, Citation2020); mobilities research that explores the nature of dialogue on the move (Laurier et al., Citation2008) and on creative landscape research that engages with the non-human agency (Hawkins, Citation2021; Macpherson, Citation2010). There is now significant literature about mobile methods and praise for their ability to capture the fleeting, distributed, multi-sensory, emotional and kinaesthetic (Büscher, Urry, & Witchger, Citation2010). In particular, there has been a rise in the popularity of walking methods (Edensor, Citation2010; Macpherson, Citation2016b) and some in-depth consideration of the nature of dialogue on a car journey (Laurier et al., Citation2008). The Taxi project recognises these insights into the potential benefits of mobile methods. Discussion of the particular power relations involved in this project is to be found in the final section ‘Western perspectives and validation of process’ and the conclusion to this paper.

Taxi Guff-Gaff project methods

‘Taxi Guff-Gaff’ was originally produced as an art intervention for the Kathmandu Triennale. Twelve artists, poets and writers that were invited to participate were mostly at the start of their careers and were from Kathmandu Valley. The artists were selected by Niscal Oli (Nepali, co-producer) to travel in the taxis. They had all covered topics of urbanisation in their art forms and it was felt that this offered a novel way for them to reflect on their landscape experiences and open up a conversation between them about their future role as contemporary artists in the city. The theme of the Triennale was ‘The City My Studio/The City My Life’. Originally this international art event was supposed to happen in 2015. However, two devastating earthquakes and over 400 aftershocks rocked Nepal in 2015.

The Triennale and Taxi Guff-Gaff project occurred in 2017 when the city was still severely earthquake damaged. Many pavements were still very damaged and it was hard to move through the city easily on foot - working with a mobile drawing method within the taxi space was a choice made partially out of necessity in this post-disaster context. Furthermore, many lives were lost and homes and livelihoods were damaged during the earthquakes and artists had begun to question the value of their practice in this context. Through the Triennale theme and the taxi project, they explored what the city meant after that incident (many artists became increasingly participatory and outward-looking in their practice after the earthquakes). Participants in the Taxi journeys were asked to discuss How does the city contribute to our work as artists, writers and thinkers? And What have we seen change?

The loose frame of the questions in the taxi was deliberate because it allowed us to meander and arrive at something chosen (whether or not consciously) by the participants. See Helguera (Citation2011, pp. 43–44) for a longer discussion of the relative merits of clear structures or informal conversational exchanges in participatory arts projects. The ambition of the artist director, Alice Fox, was to develop a safe yet uncertain conversational and drawing space, that would help others get out of their own mindset. In order to do this and cultivate visual answers to the questions above it was proposed that a series of motion drawings using pen and charcoal were to be made collaboratively together on one long piece of paper across the back seat of the taxis.

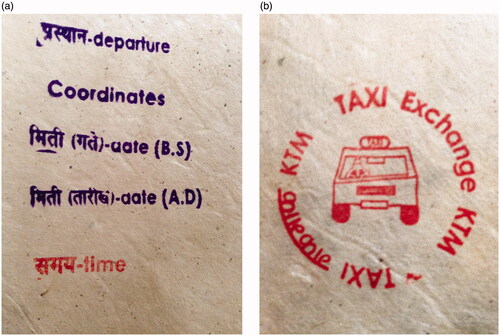

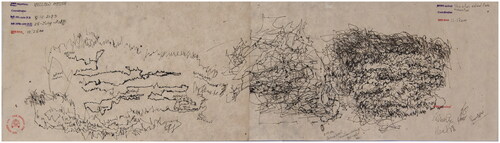

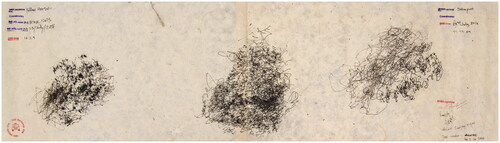

The four small taxis (Maruti Suzuki Alto 800 s) travelled in convoy, with the outbound journey the same as the return journey. This was about two hours each way across the Kathmandu Valley and up into the foothills of the Himalayas to Shivapuri National Park. We chose this route to the north so that we got to the limit of the city. We went from immersion in the city to an overview of the Kathmandu Valley landscape on a hill in the National park above the city. Participants were asked to discuss the questions while ‘drawing’ (relaxing their hand and letting the journey make the marks) on locally Handmade Nepali ‘Lokta’ paper. This is paper made from the bark of the bush Daphne Papyrus which grows at altitudes in the Himalayas. It is a sustainable material (the inner bark is stripped away to make the paper but the root remains intact for regrowth) that connected participants more literally to the wider environment. Alice Fox prepared the paper using ribbon and handmade stamps to add further value to the process (). This approach to collective drawing was useful for collecting visual information regarding terrain surfaces, but also the way in which these surfaces sensually affect those who pass over them in vehicles. Because the human hand is not mere support for the pen or charcoal that records this information, it adds to the process a will to express itself.

The mobile conversational-drawing experience was captured within the drawings themselves () and through Go Pro film recordings (http://arts.brighton.ac.uk/staff/alice-fox/taxi-guff-gaffexchange-ktm). The project was filmed in order to develop an edited version for display with the final drawings (although ultimately a curatorial decision was made to leave the drawings more open to interpretation and the film was made available on the project web page only). There were 4 taxi tours of the city with 3–4 people in each taxi 16 people in total participated in the project including the drivers (Babu Ram Bastakoti, Sanjay Pujari, Pramod Puri, Dhan Kumar Tandukar) the artist and director (Alice Fox) co-producers (Niscal Oli and Siân Aggett). There was a plush dash cam and some filming took place on the back of a motorbike for external shots. The outbound and return journeys involved separate drawings (See ).

In 2021, unable to conduct further empirical research as a result of the Covid 19 pandemic, we returned to this project, revisited the original pictures and listened to the original recordings and films to help reflect on the possible research value of this experimental work. We also conducted zoom conversations with our co-authors and six follow-up qualitative zoom interviews with Nepali artist-participants from the original project, during these interviews we sought to reflect on what they recalled from it and its possible value in a Nepalese context. Together we sought to answer the questions: What can this sort of mobile drawing make present? What spaces of landscape did drawing on the move open up? What are the perceived benefits and limitations of such practice? In so doing we have helped advance our collective awareness of both mobile drawing as a landscape research practice and the context of art practice in Nepal. The focus of this paper is primarily on the process and experience of mobile drawing rather than analysing in detail the precise content of the conversations in the Taxis.

Research findings

Drawing after the earthquake: reflecting on changing values

By 2017 Nepal was in the recovery and rebuilding phase of the earthquakes, so it was a good time to reflect on both the city and the role of the artist in the city, with artists who had lived through the earthquake. As Sangeeta, Head of Siddartha Arts (a large arts foundation in Nepal and co-organiser of the Triennale) explains:

“…it is very important to note that the theme of the Triennale that year …so many houses were damaged and so many lives were lost [in the earthquakes] and the artists rose up to these challenges and began to help people in remote areas who were affected” Sangeeta Thapa, Siddartha Arts

The earthquakes were a shared experience of many of those artists invited to contribute to the project. It was also noted how there was an uncontrollability to the approach of drawing in taxis which echoed what was found in the experience of Kathmandu post-earthquake. This can also be seen and felt in the aesthetic affect of the final drawings (). It was one important context for the drawings and how they were made, discussed and interpreted. It is also worth noting that Nepal ‘art scene’ itself has changed significantly over the past decade, partly as a result of the earthquake and partly as a result of social media influence and a rise in forms of identity politics, that impact what the population is seeking from contemporary art. This new Nepali arts discourse fed into the themes found in the Triennale and what was valued in these taxi drawings:

“The population is very young in Nepal and they are no longer satisfied with just beautiful paintings. They want art to ask questions that are reflective of the social and political time that we are now in…. We have a young population that will not be seduced by beauty alone, they want art that awakens thoughts” Sangeeta Thapa, Siddartha Arts

Drawing and talking on the move: shifting lines and conversations

The process of mobile drawing within the taxi space created conversations and lines that often shifted along with the movements of the charcoal, the taxi, the road and each other. What we see in the final drawings is not only the movement of the taxi and the road. It is also the movement of the person next to you – so there is a coming together of all sorts of movements in the drawings which makes them interesting ‘research objects’ to look at and provoke further discussion. As Kiran explains:

“While we were drawing in the taxi the movement of the taxi made the lines but also the movement of the person next to you, bumping into you, created these lines.” Kiran Maharjan, Street Artist

So the pictures we see () represent a collective mobile landscape aesthetic. Furthermore, the enforced situation of being in a car, both ‘side-by-side’ but also moving forwards offers a new and re-organised situation through which drawing and conversations can take place. Experiences of drawing and features of the final drawings produced through the taxi project were also linked imaginatively to the original motion of the earthquake and the forces that are ‘beyond your control’:

“Our roads in Nepal are so bumpy you simply couldn’t control the line and sometimes it would even go out of the drawing. So for many artists in Nepal this is a new thing to accept that this can be a drawing and it isn’t doodling. But the motion of the taxi and the bumps in the road being a driving force that you can’t control and you can connect this to the earthquake in a way because what time it jumps you never know.” Ashmina Ranjit

For some it was as if the road was ‘mapping itself’. As Samip explained to us:

“The road was sort of mapping itself on the paper through us and the taxi, so we were aware of the jolts and bumps in the road and that would creep into the conversation as well and sometimes we would look at the drawing and the shape it was taking.” Samip Dhungel

The sense of risk experienced on the Kathmandu roads also added a distinct component to this experience for some participants:

“Well in those Taxis in Nepal your heart is in your mouth a lot of the time. But maybe that was just the Westerners who felt that rather than the Nepalis. But I guess it did create a sense of danger that was making things more exciting…more buoyant. Not desperately scared or white knuckled. But I do think that opened us up to drawing and talking in a way that a static conversation wouldn’t” Siân Aggett

“In the religious paintings and in the Sand Mandalas made by monks in Nepal everything is very controlled and prescribed, you can’t stray from the narrative. If you are making a sand mandala the measurements are just so. Now in the Taxi project artists couldn’t do that, every bump was a line” Sangeeta Thapa, Siddartha Arts

There was a variably shared excitement on the Kathmandu roads, journeying together and making a drawing together as three people with a longboard and shared a piece of paper across the back of the taxi. The novelty of the process made it a memorable project that participants could recall to us three years later. Thus mobile drawing and talking within the confined space of a taxi has the potential to reveal the dynamism and relational nature of landscape experience by ‘inviting in’ multiple non-human participants (the road, the car, the charcoal) it encompasses multiple sensory and affective non-representational registers. Furthermore, participants literally and metaphorically ‘drew connections’ between different kinds of risk and different kinds of motion including verbally reflecting on the risks and challenges of the earthquakes and the risks and challenges of the monsoon potholed busy Kathmandu roads.

Drawing on the move: ‘lets see what it becomes’

The resulting artwork in this project can be viewed as part of a process, a way of knowing, a manner of speaking or an encounter that promotes dialogue and opens up new ideas and conversations. In the Taxi Guff-Gaff project, the drawings were exhibited as stand-alone pieces to the visiting public at the Kathmandu Triennale. The sort of drawing that occurred in the back of the taxi was very different from the representational drawing that you often see in work that uses drawing as a landscape research method. As Ashmina observes:

“You are not using your conscious brain, rather the movement of the taxi moves the charcoal and makes the drawing so it wasn’t really head-hand drawing but still this movement was guiding the drawing…. It was out of control, but we were enjoying that movement of the line whilst we were also talking, including with the taxi driver. So I think that ‘taxi-turns into studio thing’ was something very interesting about this project. It brings something alive, it very much brings life to the space “Ashmina Ranjit, Nepali Feminist Artist

Samip (a Nepali poet and participant), explained to us how he felt comfortable using this technique of drawing precisely because it required no particular drawing skill or conscious representational abilities:

“I felt comfortable because we were interested in ‘let see what it becomes’ rather than trying to make it something – so there wasn’t a lot of pressure to try and get your line right or whatever” Samip Dhungel, Poet and Kathmandu college lecturer

The Taxi drivers spoke of how they were proud of the less bumpy drawings because they represented better driving with fewer potholes, however, in this project the drawings are also significant because they are part of a process and an experience (see also Bullen et al., Citation2017). Some of the artist participants felt the city was ‘mapping itself’ through them. This resulted in a different sense of themselves as artists, it involved a displacement of the individual artistic ego in favour of an understanding of the collective of human and non-human agents involved in the mark-making. Such novel creative approaches open up particular relational spaces of people-spaces-taxis-roads-landscapes and art materials. In so doing they create ‘openings’ – that is new emergent forms of subjectivity. They also bring into awareness the generative nature of any encounter through participatory arts practice or through social research. This sort of approach to mobile drawing as a landscape research method is an “imprecise science concerned more with hope for politico-epistemic renewal than validity.” (Vannini, Citation2015, p. 3) it is anchored not in telling coherent stories but rather in the presence of practice.

It is an approach to documenting landscape encounters that diverges from both Western individualist histories of representational landscape art and Nepali traditions of religious art. For example, in Kathmandu Valley, Newar traditional religious art (which is now highly acclaimed by international art lovers) requires a deeply-disciplined approach with specific rules and rituals that stem from both Buddhist and Hindu religious texts and other cultural influences from Tibet, China and India. However, in the last two centuries, neither Britain or Nepals’ traditions of Landscape art can be viewed as entirely independent from the other. For example, there have been British cultural and political influence in Nepal to secure trade routes since the 1800 s and this is reflected in the evolution of Nepalese artistic traditions which began to also be associated with aesthetic pleasure and personal uplift rather than being primarily religious documents (for a more comprehensive account of the evolution of Nepalese traditions of art see Van Der Heide, Citation1988).

Western perspectives and validation of process

All research is immersed within complex sets of power relations. However, co-producing arts interventions in the global south is particularly fraught with inequalities in power, status and resource (Cooke & Soria-Donlan, Citation2019). Therefore, when we think about the dynamics within the drawings and within the taxis, we must also have some appreciation of these power differentials, how they shaped the final outputs and how they might shape audience encounters with the outputs.

For example, in adopting mobile drawing methods we must be wary of our own, or others’ ‘romantic reading of mobility’ (Hannam, Sheller, & Urry, Citation2006) or of giving privilege to certain ways of seeing the city that only arise through certain cosmopolitan mobility. Mobility is an asset that is unequally distributed and any researcher who adopts mobile drawing methods need to reflect on this simple fact (Merriman, Citation2014). In Nepal, for example, a taxi is an elite luxury and there is a gendered dynamic to mobility and (im)mobility, with migration and international mobility predominantly the preserve of men and relatively few Nepali women (Zharkevich, Citation2019). Furthermore, the fact that the art director came from a British University via the British Council gave the project status and value. It helped artists and art organisations in Nepal to coalesce around it and for the project to happen within a relatively short timescale, as Ashmina, Sangeeta and Siân explain:

“I was trying to establish this participatory collaborative art project from 2000 in Nepal. But then someone from outside, coming and giving it status and saying that this sort of work is better, that is important.” Ashmina Ranjit

“When (the UK based artist –academic) came here …it was like ‘hey Nepal exists, let’s make things happen’, and getting people to wake up to the fact there is a vibrant art scene in Nepal is something that we (at Siddartha Arts) have always been passionate about” Sangeeta Thapa

“Now there is difficulty around the fact that it wasn’t a Nepali born project. But the fact that it was a Westerner, with status, held value that allowed people to coalesce around it and value it and want to be involved with it….status means a lot in Nepal.” Siân Aggett

We can see from the comments above the project would not have happened in the way it did without certain relationships and understandings of western expertise being in place. The budget for the project also went a long way in that context - so we acknowledge that there is an opportunity created by inequity that shaped the project and its outcomes. The project would also not necessarily have unfolded in the way that it did in another country from the global south, it is hugely aspirational for many Nepali artists to be connected to a global art context and be seen on that stage and a particular receptiveness in Nepal for Westerners to be there. However, it is possible that there would be a learnt mistrust of such ‘creative interventions’ in some other places (Cooke & Soria-Donlan, Citation2019). It is also interesting to note that the inclusive, participatory approach to mobile drawing in the taxi project finds resonance within earlier collective traditions of Nepali art making and respect for the non-human agency.

“In a way a participatory aspect has always been there in our culture. Festivals and farming are all participatory activities. People gather to do rice planting. For example, the community gather together to help each other in each others’ fields. And in other festivals there are people that come together to build and pull the chariots. But contemporary art has, until recently been viewed as a solo practice” Sanjeev Maharjan, Visual artist

“Historically art and life have been intermeshed (entwines her fingers) and every household would make art and community would come together to make paintings but nobody would sign it. The individualist thing is actually from a western perspective of what art is.” Ashmina Ranjit

Nepal has its own traditions of art, performance and embodied storytelling and histories of thinking about the non-human and inhuman agency that we have only begun to touch on in this paper (Torri, Citation2021; Van Der Heide, Citation1988). Respectful awareness of the sorts of materials and approaches that are appropriate to the setting is key here, as is the facilitation of local participatory artists. For example, the involvement of Nepali artists and co-producer Niscal Oli from the outset grounded this project and the writing of this article and the use of long pieces of locally handmade Lokta paper and charcoal were valued by local artist participants. They situated us in the time and context differently than if we had just used biros and A4 paper. The facilitation mattered, the local materials mattered as did the spatial arrangement of boards, laps and journeys across the city.

Conclusions: mobile drawing as landscape research method

Taxi Guff-Gaff was a co-produced arts project that took place in Nepal but contains insights that are relevant to a much wider community interested in both drawing methods and creative forms of landscape research. Through retrospective research interviews with participants and reflective discussions with our co-authors the potential importance and drawbacks of the approach were explored and four key conclusions emerge from our findings.

Firstly we think the process and the drawings themselves are the most interesting outcomes of the project. The project shows how drawing in unpredictable environments impacts the line and the drawing outcome leads us to reflect on what can be ‘made present’ through drawing. The drawings are important precisely because they are indeterminate objects that remain open to new forms of interpretation in exhibition settings. In the paper, we show how the drawing together on a shared piece of locally made Lokta paper cultivated the presence of a Kathmandu Valley landscape ‘in becoming’ through human and non-human agents (the materials, the car, the road, the vehicle). The drawing element of this project can be understood as ‘non-representational’ research because” It is no longer what happened that matters so much but rather what is happening now and what can happen next. It is no longer depiction, reporting, or representation…. Rather, it is enactment, rupture, and actualisation that engage your attention.” (Vanini, 2015, p. 12). In this way, mobile drawing is could be used as a powerful research tool that helps build rapport and stimulate conversation.

Secondly, the impossibility of representational drawing on a bumpy taxi journey ensures that participants can only let the charcoal or pen ‘go for a walk’. This may help participants let go of representational ambitions for drawing and other preconceived ideas about what drawing is that may be barriers to full participation (see also Lyon, Citation2020). It also offered an immersive way to relate to the urban landscape and each other and could be a useful ‘ice-breaker’ technique when working with open-minded research subjects or university students. Thirdly, drawing together, collaboratively on one long piece of paper in the back of the taxi also made the project a fun, playful and engaging ‘ramillio’ activity that built rapport, triggered dialogue and created an innovative drawing outcome. Participants bounced about together, drew together and came to know each other in new ways. New forms of fleeting emergent subjectivity emerged here through this non-normative arrangement of human and non-human actors.

Fourthly, we found that drawing on the move as a mobile method that involves both activity and conversation builds on the recognised strengths of other mobile research methods. For example, it uses the environment and the activity as conversational prompts (Macpherson, Citation2016b) and it can use the advantages of video and GoPro cameras to capture responses and movements on the move (see also Bates, Citation2013; Spinney, Citation2015) Furthermore, the enforced situation of being in a car side-by-side, but also facing forwards offers a re-organised research situation, within which both new drawing and new conversations can take place (see also Laurier et al., Citation2008). Whilst the primary focus of this paper was on the drawing the taxi project participants also spoke of the changing nature of the city, of urban expansion, of gender relations, of their evolving sense of themselves as artists in the city and their particular experiences of the Kathmandu Valley post-earthquake.

In conclusion, collaborative drawing together on shared paper in a bumpy taxi journey opened up spaces of landscape research that centred on speculative forms of thinking, being and conversation. It is ethical, for it promoted rapport building and enhanced the capacity to think with practices of novel togetherness. It did not produce easy-to-interpret images, rather it could be understood as a form of ‘inefficient mapping’ (Knight, Citation2021) and a key component of wider research efforts to develop techniques for thinking through and with the non-representational, mobile and multi-sensory nature of human experience (see also Latham & McCormack, Citation2009). The approach helped to generate a certain communal spirit (including pushing the taxis up the hill together!) and very close attention to bumps on the road and the literal ‘moment at hand’ through the movements of the taxi and its impact on the line of the person drawing. Thus, in common with other mobile methods, drawing on the move helped to cultivate new empirical sensitivities and analytical orientations (see Büscher et al., Citation2010). This experimental project was conducted with Nepali artists, writers and poets who were likely to be open to such a novel creative research approach. Careful consideration would need to be given to how such a process might translate into other contexts (Aggett, Citation2018). That said drawing on the move has the potential to be mobilised as a creative landscape research method amongst open-minded research subjects that may facilitate rapport building and trigger discussions around the dynamic, relational and non-representational qualities of our landscape encounters.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all of our partners and friends who supported this work in Nepal, including taxi drivers, Babu Ram Bastakoti, Sanjay Pujari, Pramod Puri and Dhan Kumar Tandukar; participants, Sujan G Amatya, Samip Dhungel, Kiran Maharjan, Sanjeev Maharjan, Sunita Maharjan, Gopal Kalipremi Shrestha, Rabin Shrestha and Archana Thapa; film crew, Freya Bolton, Prashant Das, Suresh Lyonjan and Felix Sagar; and co-producers, Siân Aggett and Niscal Oli. We also wish to thank Nayantara Gurung at The Yellow House, and Triennale director Philippe van Cauteren.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alice Fox

Alice Fox is Principle Lecturer in The School of Art and Media at the University of Brighton where she founded the pioneering MA Inclusive Arts Practice. In 2003, Alice founded the Rocket Artists’ Studios for artists with learning disabilities and their non-disabled collaborators. She has worked for many years in participatory performance and visual arts alongside some of the world’s most socially excluded groups, in particular people with learning disabilities, elders and women. Alice often applies her research whilst training NGOs, museum, health & education workers. Alice has delivered inclusive arts projects for Tate Exchange, The National Gallery and The British Council in Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Vietnam, South Korea and Nepal. Alice is currently working with the British Council and 15 arts organisations across Myanmar to increase their inclusive arts capacity. Alice, alongside Hannah Macpherson, co-authored the subject defining book Inclusive Arts Practice and research: a critical manifesto (2015, Routledge). In recognition of her ground breaking Inclusive Arts work, Alice won the Times Higher Education Award 2017 for Excellence and Innovation in the Arts. Alice was also a Trustee for Epic Arts in Cambodia and is a special advisor for SuperHero Me, Singapore and Gentle Giants, Philippines.

Hannah Macpherson

Hannah Macpherson is a freelance leader in creative co-production. She is co-author of the Arts Council funded title ‘Inclusive Arts Practice and Research: a critical manifesto’ with Alice Fox (Routledge 2015) and was Principal Investigator on the Arts and Humanities Research Council funded multi-partner project ‘Building resilience through collaborative community arts practice’. Her internationally recognised research addresses arts and health; geographies of the senses; landscape; creative methods and practice; debility and D/disability; research impact and public engagement. She is an accomplished senior lecturer, research project manager, creative workshop facilitator and grant writer. Twitter: @DrHMac

Nischal Oli

Nischal Oli is a Kathmandu-based arts professional who has worked in capacity of manager, curator, writer and project lead for artform-based and cross-disciplinary projects and organisations. He currently heads the Arts department for the British Council in Nepal.

Ashmina Ranjit

Ashmina Ranjit is one of Nepal’s leading conceptual artists. She has been a key leader in the movement for artivism (art + activism). Her art is an expression of her commitment as an ‘Artivist.’ She positions herself consciously as an artist from the Global South and is influenced to a certain degree by the cultural ‘otherness’ that is embedded in her works. Her artworks interrogate, challenge and confront the status quo. Subversion of stereotypes, politics of gender and human rights are critical to her process driven work. With her performances, during the 10 years of insurgency, Ashmina brought together armed forces, Maoists, politicians, civilians, and students to raise voices against violence, and for democracy. Today, Ashmina performs, creates, curates, leads workshops, and connects communities. She creates an environment of collaboration and innovation for artists at her art-hub LASANAA/NexUs Culture Nepal. Ashmina, a two-time Fulbright Scholar, has earned many international scholarships and awards, participated in various residencies, and delivered lectures. She received her MFA from Columbia University, NYC, and her BFA from University of Tasmania, Australia, as well as from Tribhuvan University, Nepal. The National Daily ‘The Kathmandu Post’ featured her as one of 25 individuals who shaped Nepal in 2018.

Sangeeta Thapa

Sangeeta Thapa is the Founder and Director of the Siddhartha Art Gallery and Siddhartha Arts Foundation. In 2009, she also co-founded the Kathmandu Contemporary Art Centre. The KCAC serves as a residency space and is located within the historic Patan Museum. Thapa is a board member of the Patan Museum Development Committee. She is also a contributing author for the Pakistani art journal, Nukta, and is the publisher of three volumes of poetry by Nepali poets. In her vibrant 32 year career, Thapa has been felicitated and honoured with several awards, and is celebrated by the arts community in Nepal and abroad. She works closely with the Australian Himalayan Foundation in providing bursaries to young artists. She has curated over 300 art shows of both Nepali and international artists at Siddhartha Art Gallery.

Siân Aggett

Siân Aggett is a participatory arts and engagement producer/practitioner, researcher and evaluator. She has worked in the field of public engagement with research for over 20 years both within the United Kingdom’s museum and higher education sector. Siân has worked extensively in the context of engagement with medical research with an emphasis on global health research. She was manager of the International Engagement Programme at the Wellcome Trust until 2013 and now works for the National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement based that the University of the West of England and is director of Hilo engagement consultants. She is a PhD candidate in Global Studies at Sussex University. Her academic background transgresses borders spanning science, social science and the humanities. Twitter: @Siânaggett

Andrew Church

Professor Andrew Church is Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Research and Innovation) at the University of Bedfordshire. Andrew has over 25 years of experience in linking his research in human geography, environmental planning and ecosystem services to the work of artists and arts researchers to understand the environmental concerns of a wide range of public, private and community sector stakeholders. He is currently working with inclusive arts practitioners, social scientists and natural scientists on the Economic and Social Research Council funded project Towards Brown Gold?: Reimagining off grid sanitation in rapidly urbanising areas in Asia and Africa. Andrew also works on international collaborative research projects and between 2016 and 2020 was a Coordinating Lead Author on the UN Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). The findings have been published in international journals and reveal the cultural, social and economic dimensions of ecosystem integrity and vulnerability. Andrew has a track record of publishing research on the social, environmental and cultural aspects of outdoor recreation including a recent 2020 book English Wetlands Spaces of Nature, Culture, Imagination (Palgrave Macmillan).

References

- Aggett, S. (2018). Turning the gaze: Challenges of involving biomedical researchers in community engagement with research in Patan, Nepal. Critical Public Health, 28(3), 306–317. doi:10.1080/09581596.2018.1443203

- Bates, C. (2013). Video diaries: Audio-visual research methods and the elusive body. Visual Studies, 28(1), 29–37. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2013.765203

- Bochner, A. P., & Ellis, C. (2003). An introduction to the arts and narrative research: Art as inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 9(4), 506–514. doi:10.1177/1077800403254394

- Boults, E., & Sullivan, C. (2020). Illustrated history of landscape design. New Jersey: Wiley Publishing

- Bullen, D., Fox, J., & Lyon, P. (2017). Practice-infused drawing research: 'Being present' and 'making present. Drawing: Research, Theory, Practice, 2(1), 129–142. doi:10.1386/drtp.2.1.129_1

- Büscher, M., Urry, J., & Witchger, K. (2010). Mobile methods. London: Routledge.

- Causey, A. (2016). Drawn to see: Drawing as an ethnographic method. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Clarke, J., & Foster, K. (2012). Field drawing as dialogue and form of making knowledge. Tracey: Journal of Drawing and Visualisation Research, 1–19.

- Cooke, P., & Soria-Donlan, I. (2019). Participatory arts in international development. London: Routledge.

- Crawshaw, J. (2018). Island making: Planning artistic collaboration. Landscape Research, 43(2), 211–221. doi:10.1080/01426397.2017.1291922

- Edensor, T. (2010). Walking in rhythms: Place, regulation, style and the flow of experience. Visual Studies, 25(1), 69–79. doi:10.1080/14725861003606902

- Franklin, M. (2010). Global recovery and the culturally/socially engaged artist. In Peoples, D. (Ed.), Buddhism and ethics (pp. 309–320). Ayuthaya, Thailand: Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University.

- Frederick, U. K. (2021). The bad and the beautiful: An artist’s encounter with the image of Port Arthur, Tasmania. Landscape Research, 46(3), 341–361. doi:10.1080/01426397.2020.1837090

- Hannam, K., Sheller, M., & Urry, J. (2006). Editorial: Mobilities, immobilities and moorings. Mobilities, 1(1), 1–22. doi:10.1080/17450100500489189

- Hawkins, H. (2021). Geography, art, research: Artistic research in the geohumanities. London: Routledge.

- Helguera, P. (2011). Education for socially engaged art: A materials and techniques handbook. New York: Jorge Pinto Books.

- Hogg, B. (2018). Weathering: Perspectives on the Northumbrian landscape through sound art and musical improvisation. Landscape Research, 43(2), 237–247. doi:10.1080/01426397.2016.1267719

- Hutchisom, E. (2019). Drawing for landscape architecture sketch to screen to site. United Kingdom: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

- Kantrowitz, A., Fava, M., & Brew, A. (2017). Drawing together research and pedagogy. Art Education, 70(3), 50–60. doi:10.1080/00043125.2017.1286863

- Knight, L. (2021). Inefficient mapping: A protocol for attuning to phenomena Santa Barbara, California: Punctum Books. doi:10.21983/P3.0336.1.00

- Latham, A., & McCormack, D. P. (2009). Thinking with images in non-representational cities: Vignettes from Berlin. Area, 41(3), 252–262. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.2008.00868.x

- Laurier, E., Lorimer, H., Brown, B., Jones, O., Juhlin, O., Noble, A., Perry, M., … Weilenmann, L. (2008). Driving and ‘passengering’: Notes on the ordinary organization of car travel. Mobilities, 3(1), 1–23. doi:10.1080/17450100701797273

- Leavy, P. (2018). Introduction to arts based research. In P. Leavy (Eds.) Handbook of arts-based research. New York: Guilford Press.

- Lyon, P. (2020). Using drawing in visual research: Materializing the invisible. In L. Pauwels, & D. Mannay (Eds.), The sage handbook of visual research methods (pp. 297–308 (2nd ed.)). London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Macpherson, H. (2010). Non-representational approaches to body-landscape relations. Geography Compass, 4(1), 1–13. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00276.x

- Macpherson, H. (2016). Walking methods in landscape research: Moving bodies, spaces of disclosure and rapport. Landscape Research, 41(4), 425–432. doi:10.1080/01426397.2016.1156065

- Macpherson, H., Fox, A., Street, S., Cull, J., Jenner, T., Lake, D., … Hart, S. (2016). Listening space: Lessons from artists with and without learning disabilities. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 34(2), 371–389. doi:10.1177/0263775815613093

- Mair, M., & Kierans, C. (2007). Descriptions as data: Developing techniques to elicit descriptive materials in social research. Visual Studies, 22(2), 120–136. doi:10.1080/14725860701507057

- Merriman, P. (2014). Rethinking mobile methods. Mobilities, 9(2), 167–187. doi:10.1080/17450101.2013.784540

- Mitchell, C., Theron, L., Stuart, J., Smith, A., & Campbell, Z. (2011). Drawings as research method. In L. Theron, C. Mitchell, A. Smith & J. Stuart (Eds.) Picturing research. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Prosser, J., & Loxley, A. (2008). ESRC National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper: Introducing visual methods. ESRC National Centre for Research Methods. http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/420/1/MethodsReviewPaperNCRM-010.pdf.

- Roberts, A., & Riley, H. (2014). Drawing and emerging research: The acquisition of experiential knowledge through drawing as a methodological strategy. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 13(3), 292–302. doi:10.1177/1474022213514559

- Rogers, A. (2010). Drawing the spaces between us: Using drawing encounters to explore social interaction. In P. Martin (Ed.) Making space for creativity. Brighton: University of Brighton.

- Spinney, J. (2015). Close encounters? Mobile methods, (post)phenomenology and affect. Cultural Geographies, 22(2), 231–246. doi:10.1177/1474474014558988

- Torri, D. (2021). Sacred, alive, dangerous, and endangered: Humans, non-humans, and landscape in the Himalayas. In S. Riboli, A. Strathern, & D. Torri (Eds.) Dealing with disasters. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Van Der Heide, S. (1988). Traditional art in upheaval: The development of Modern Contemporary art in Nepal. Kailash—Journal of Himalayan Studies, 14(3), 227–239.http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/kailash/pdf/kailash_14_0304_04.pdf

- Vannini, P. (2015). Non-representational methodologies: Re-envisioning research. New York: Routledge.

- Yusoff, K. (2015). Geologic subjects: Nonhuman origins, geomorphic aesthetics and the art of becoming inhuman. Cultural Geographies, 22(3), 383–407. doi:10.1177/1474474014545301

- Zharkevich, I. (2019). Gender, marriage, and the dynamic of (im)mobility in the mid-Western hills of Nepal. Mobilities, 14(5), 681–695. doi:10.1080/17450101.2019.1611026