ABSTRACT

The educational disparities that can be found in the English language learning outcomes of middle school students in Austria have gone relatively unexplored in international research. National studies have tended to attribute lower educational outcomes either to students’ socioeconomic status or their multilingual background. In this article, we use the theory of intersectionality to shed new light on how educational disparities that run along socioeconomic lines are tightly entangled with beliefs about students’ multilingualism, arguing that these two factors must be explored in tandem to understand educational disadvantage in this context. Our study brings together a rich description of the educational context with a quantitative exploration via questionnaire of the beliefs and classroom practices of 56 English teachers at Austrian middle schools. Analyses of the data allow insight into how teachers’ beliefs about their students’ abilities, motivations and access to English outside of school and teachers’ language use in the classroom all relate to the lower outcomes in English at Austrian middle schools. The article closes by considering the importance of the findings for policy and practice in English language education in Austria, including ideas for the transformation of these.

Introduction

Austria is one of the countries in Europe with the shortest span of comprehensive schooling. After Grade 4 in primary school, when students are around ten years old, they are tracked into one of two different school types: General academic secondary schools steer students towards university, while middle schools aim to equip students for starting professional life and/or moving on to upper secondary levels of education (BMBWF Citation2018). Research reveals that this dual-track education system perpetuates disadvantage: Middle schools attract a higher number of students from families of lower socioeconomic status where students’ parents often have less experience of formal education than those of students who attend the more academic track of schooling (Bruneforth et al. Citation2016; Bruneforth, Weber, and Bacher Citation2012; Fend Citation2009; Herzog-Punzenberger Citation2017; Luciak Citation2008; Schreiner, Suchań, and Salchegger Citation2020). In urban areas, middle schools are also known for having high numbers of students from a migration background and who speak languages other than German at home (Statistik Austria Citation2019).

In standardised national assessments, middle school students typically perform below the national average (Schreiner, Suchań, and Salchegger Citation2020). This is also the case with regard to learning outcomes for English, one of the three core subjects in Austrian education. In 2019, Austria’s Federal Institute for Educational Research, Innovation and Development administered the second cycle of testing English (BIFIE Citation2020a) within the Austrian Standards-Based Tests (BiST), the nation-wide testing of standards during the last year of lower secondary school, i.e. the penultimate year of compulsory schooling. The results of this assessment, discussed in more detail below, show that middle school students performed below the national average and much below their peers in general academic secondary schools. Educational outcomes in urban middle schools with high numbers of students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and who speak languages other than German at home tend to be the lowest (BIFIE Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Moreover, students who speak languages other than German at home had lower learning outcomes when compared with those who speak German as a home language. This is not what one would expect given research that has established benefits of multilingualism with regard to additional language learning (Cenoz, Hufeisen, and Jessner Citation2001; Conteh and Meier Citation2014; De Angelis Citation2007; Jessner Citation2006): the English language classroom should be a place where students who speak other languages than German at home thrive. Indeed, when controlling for socioeconomic status in analysing these learning outcomes, the difference between these two groups is substantially reduced, and speaking languages other than German at home no longer results in a disadvantage (BIFIE Citation2020a). Coming from a lower socioeconomic status thus seems to counteract any benefits of multilingualism on learning outcomes in English for middle school students. Despite this, public discourses commonly position emerging knowledge of German as the main obstacle to school achievement in Austria, while leaving the issue of socioeconomic status unaddressed (cf. Expertenrat für Integration Citation2019). Studies undertaken in comparable European contexts have also found teachers’ beliefs about students’ language abilities and motivations, and their classroom practices informed by these beliefs, to be important in the perpetuation of disadvantage (e.g. Hall and Cunningham Citation2020; Heyder and Schädlich Citation2014; Lundberg Citation2019; Young, Citation2014). These studies, however, neglect to explore factors of socioeconomic status that shape teachers’ beliefs and practices with regard to their students. In this article, we use the theoretical lens of intersectionality (Crenshaw Citation1989) to shed new light on how educational disparities that run along socioeconomic lines are tightly entangled with beliefs about students’ multilingualism, arguing that these factors must be explored in tandem to understand educational disadvantage in this context.

Intersectionality theory and educational inequalities in the Austrian educational context

Intersectionality theory is a framework that emerged from the racialized experiences of minority ethnic women in the United States (Crenshaw Citation1989), which is increasingly used in the field of education to examine interconnections and interdependencies between the range of structural and social factors affecting advantage and disadvantage (cf. Hempel-Jorgensen and Cremin Citationforthcoming). It offers opportunities to enhance critical analysis of educational contexts and provide theoretical explanations of the ways in which institutional structures, beliefs and practices intersect to yield disparities (Atewologun Citation2018). For example, intersectionality theory can help us to understand the ways in which members of a particular group (such as ‘students from a migration background’) experience education differently depending on factors like ethnicity, gender, linguistic background, and/or socioeconomic class. Sensitivity to such disparities is essential for going beyond simplistic, static, one-dimensional understandings of people’s circumstances, enhancing our abilities to respond to disparities in education, and maximising possibilities for transformation (Tefera, Powers, and Fischman Citation2018).

The educational disparities that can be found in the English language learning outcomes of middle school students in Austria have gone relatively unexplored in international research. National studies have tended to attribute lower educational outcomes either to students’ socioeconomic status as the main factor affecting achievement (Oberwimmer et al. Citation2016) or to the large number of students who speak other languages than German at home (Expertenrat für Integration Citation2019). We draw on the theory of intersectionality to explore the combined effects of having lower socioeconomic status and speaking other languages than German at home. We see these factors as tightly intertwined and argue that they must be explored in tandem to understand educational disadvantage in this context and how it might be redressed.

An important structural and institutional factor affecting disadvantage in Austria is the dual-track education system. After completing four years of primary school, at around the age of ten, students are tracked into one of two different school types: Allgemeinbildende Höhere Schulen (AHS), general academic secondary schools that are academically oriented and steer students towards university, or Neue Mittelschule (NMS, soon to be renamed Mittelschule) or middle schools, which seek to provide the necessary ground for moving on to further education and vocational education and training (BMBWF Citation2018). After four years of middle school, there is an option for students to move to any form of higher secondary education; however, only one out of ten students transfers to the academic track, and the dropout rate in the first year for those who manage this transition is high (Beer Citation2019). Thus, the majority of middle school students either only complete compulsory schooling or continue with vocational education (Statistik Austria Citation2019).

As one of the few OECD countries that has not converted to a more comprehensive system, Austria has an established tendency towards social segregation in education, and of being less effective regarding social mobility and integration than countries in which there is a longer comprehensive system (Bruneforth et al. Citation2016; Fend Citation2009; Herzog-Punzenberger Citation2017; Schreiner, Suchań, and Salchegger Citation2020). This has been argued to be partly related to a historical allocation of upper classes to general academic secondary schools, which were originally not designed for ‘the masses’ (Gruber Citation2015). Still today nearly double the number of Austria’s students attend middle school compared to general academic secondary schools (210,000 vs. 115,000; Statistik Austria Citation2019). Middle school is often considered a school type of lower quality and prestige, which leads to what has been referred to as the ‘creaming effect’ – the tendency of academically socialised and ambitious parents to steer their children towards a more academic school type (Gruber Citation2015, 70). While on the surface, student performance is the main criterion for school choice, studies have shown that the performance indicators used cannot be taken as independent from socioeconomic status (Bruneforth, Weber, and Bacher Citation2012; Fend Citation2009; Schreiner, Suchań, and Salchegger Citation2020). The association between social background and performance in Austria has been established as ‘one of the highest among OECD/EU countries’ (Schreiner, Suchań, and Salchegger Citation2020, 71), with PISA findings emphasising a need to make ‘student performance less dependent on students’ socio-economic status, and more on students’ own efforts and talents’ (OECD Citation2018, 104).

The inequalities resulting from the dual-track system have been recurrent educational and political issues demanding reform since the early twentieth century (Beranek Citation2000). The most recent reform, introduced in 2008, sought to enhance equity in education by adding four more years of comprehensive schooling following primary school for all students (Rechnungshof Citation2013). Instead, a political compromise was implemented, in which the new middle school model has essentially replaced its predecessor, Hauptschule, and the vast majority of general academic secondary schools have been untouched (Rechnungshof Citation2013). The most recent statistics reveal that the reform had a limited impact in terms of reducing social inequality: Students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are still overrepresented in middle school and are more likely to have parents with less experience of formal education, implying less academic parental support and less access to extracurricular learning opportunities (Oberwimmer et al. Citation2018; Schreiner, Suchań, and Salchegger Citation2020). As Beer (Citation2018) points out, however, despite such evidence, the political situation makes it unlikely that greater changes will be made in the near future.

Multilingualism in the Austrian education system

To better understand educational challenges of students who have other languages than German at home, we draw on contemporary conceptions of multilingualism, which we understand as the complex and fluid language practices commonly found amongst individuals, societies and institutions (cf. May Citation2019). Our position has been informed by a wealth of research that has regularly confirmed its cognitive, social, personal, academic and professional benefits for individuals (Conteh and Meier Citation2014; Herzog-Punzenberger, Le Pichon-Vorstman, and Siarova Citation2017). This research has also demonstrated positive effects of multilingual education, with explicit benefits for learning school languages (Cenoz, Hufeisen, and Jessner Citation2001; De Angelis Citation2007; Jessner Citation2006) and boosting self-confidence and self-esteem (García and Kleifgen Citation2018; García-Mateus and Palmer Citation2017). Contemporary investigations of multilingualism have drawn attention to the inadequacy of the vocabulary available to describe multilingual language use (Dewaele Citation2018). In Austrian educational studies, students who have German as the sole language of the home and those who have German as one of their home languages were measured together and compared to those who were classified as primarily speaking languages other than German at home (BIFIE Citation2020a, 30). While reliant on this data, we maintain that this categorisation does not capture the complex language repertoires of many multilingual students, particularly since competence in the language of education can be greater than the languages spoken at home. Moreover, multilingual students often learn languages simultaneously, with varying degrees of proficiency not necessarily related to the order in which the languages were introduced at school. For this reason, we use the terms L1 and LX user, recommended by Dewaele (Citation2018), in which L2, L3, L4, etc., users are captured under the LX user label.

Multilingualism is promoted and positioned as a resource in official language education policies across Europe: In addition to the national language, individuals are encouraged to learn another language, while also maintaining their home language if different from the national language (European Commission Citation2002). In Austria, ‘foreign languages’ are taught as a core curricular element from the first year of primary school until the end of compulsory schooling as a minimum. While other languages are offered in a minority of cases, nearly all of the students (99.9%) who study languages at lower secondary level learn English as what is termed the ‘first foreign language’ (Eurostat Citation2020). However, for students who are LX German users, English may actually be an L3 or L4, and the order in which languages are learned is unlikely to reflect the idealised sequential learning of a ‘first’ or ‘second’ foreign language.

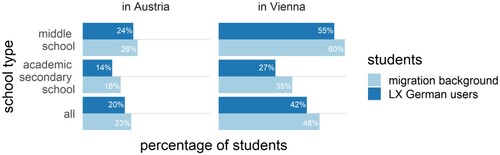

The Austrian curriculum states that all languages should be recognised and valued at school as a foundation for a democratic society (Rechtsinformationssystem des Bundes Citation2020b, Citation2020a). Particular emphasis is placed on the role that educators play in encouraging the use of students’ language repertoires as resources for learning and the development of plurilingualism and intercultural competence (BMUKK Citation2012; see also Krumm and Reich Citation2013, and the Austrian Centre for Language Competence at http://www.oesz.at/ for other Austrian initiatives promoting multilingualism in the classroom). The national curricula also encourage exchange and communication about different forms of diversity (linguistic, social, geographic, and other types of cultural background) as a means of fostering competences that enhance integration, cohesion, and socioeconomic advancement (BMUKK Citation2012). Such policies reinforce the aim for educational equity enshrined in Austrian federal law, which states that the institution of the school is to secure each citizen access to the best educational level, regardless of their origin, social status and financial background (B-VG Citation2019, §5a, Art. 14). Despite these policies, inequalities can be detected in the learning outcomes of students from migration backgrounds and who are LX German users. National statistics indicate that middle schools have a larger than average percentage of LX German users, particularly in urban areas: In the 2018/19 school year in Austria, about 20% of all students in all schools across Austria are German LX users and 24% of those in middle schools (see ). In the cities of Graz, Linz and Vienna, middle school students who were LX German users often outnumbered L1 German users (BIFIE Citation2020a; cf. Statistik Austria Citation2019). The reported number of ‘students from a migration background’ are also provided in , following the BIFIE definition of having both parents born outside of Austria and Germany (BIFIE Citation2020a, 30). These numbers are higher, showing that there is not always overlap between coming from a migration background and being a LX German user.

Figure 1. Percentages of students from a migration background according to the BIFIE definition and students who are LX German users in middle school, academic secondary schools and averaged across school types (adapted from BIFIE Citation2020a).

That many middle school students may be learning German and English simultaneously, and learning English as a third or fourth language, is often assumed to play a role in the resulting disparity of outcomes in education in general and English language education in particular. Indeed, public discourses and media discourses around the 2019 PISA results often blame lower outcomes on the high number of students who are LX German users, positioning their emergent competence in German as the main obstacle to school achievement (cf. Expertenrat für Integration Citation2019). This has been increasingly the case since what has been called ‘the refugee crisis’ in 2015 and the ensuing increase in migration, with some schools in urban areas being labelled Brennpunktschulen, which could be translated as ‘schools in a social hot spot’ or ‘toxic schools’ (cf. Mohrenberger Citation2015; Nimmervoll Citation2014; Wiesinger Citation2018). A closer look at the findings of such studies, however, reveals a more complex picture. The 2019 BiST assessments found that 73% of middle school students do not meet the desired learning outcomes set in the curriculum of CEFR level B1 or above in all areas of competence for English, compared to 31% of students at general academic secondary schools (see ).

Table 1. Rounded percentages of students in Austria with CEFR-level B1 or above in English in all, two, one or none of the areas of competence (BIFIE Citation2020a, 75).

Moreover, L1 German students outperformed their peers in English by 22–35 points. When controlling for socioeconomic status – an indexical measure derived from parents’ educational and professional status and the reported number of educational resources like books at home – the difference between these two groups was substantially reduced to 5 points for reading, 3 points for listening and –2 points for writing, with LX German users numerically outperforming L1 German students in this case (BIFIE Citation2020a).

Thus, the complexity of influences on students’ learning outcomes is widely ignored, particularly the fact that being an LX German user only manifests as a barrier to success in English language learning for students who also have lower socioeconomic status (Oberwimmer et al. Citation2018; Schreiner, Suchań, and Salchegger Citation2020). As we have seen, these socioeconomic barriers to learning are particularly present at middle school. The question thus arises why students’ multilingual resources are not able to be converted into advantages in the English language classroom in middle school. As we will argue in the following, not only the institutional context but also teacher beliefs may play a role.

Teachers’ beliefs about students’ multilingualism and abilities

In this research, we focus on teachers’ beliefs about their students’ language learning abilities and motivations to learn English. Beliefs constitute the complex cluster of intuitive, subjective knowledge about the nature of language, language use and language learning, considering cognitive, emotional and social dimensions, as well as cultural assumptions (Barcelos Citation2003; Pajares Citation1992). Previous research has shown that negative beliefs about multilingualism are common amongst teachers and other stakeholders across educational contexts (García and Kleyn Citation2016; Lundberg Citation2019; Rios-Aguilar et al. Citation2011; Walker, Shafer, and Iiams Citation2004; Young, Citation2014). Teachers’ expectations concerning the academic achievement of students has also been demonstrated to be influenced by factors such as students’ socioeconomic backgrounds and whether or not they come from a migration background (e.g. Glock et al. Citation2020; Pit-ten Cate and Glock Citation2018; Tobisch and Dresel Citation2020). Teachers’ beliefs have been shown to influence their pedagogical decisions and the strategies that teachers adopt for coping with challenges; they also strongly impact their students’ beliefs, shape their learning environment, and influence their motivation and language ability (Borg Citation2018; Gilakjani and Sabouri Citation2017; Gruber Citation2015; Haukås Citation2016; Lundberg Citation2019; Tsiplakides and Keramida Citation2010; Young, Citation2014). Teachers’ negative beliefs about multilingualism, students’ backgrounds and their socioeconomic status can therefore reinforce disparities in education, inadvertently shaping students’ attitudes towards their own capabilities and contributing to lower educational outcomes.

A comparative study with school teachers in Italy, Austria, and Great Britain found that while teachers recognise benefits of multilingualism and take a positive stance towards it in general, multilingualism is believed to be a hindrance in direct association with language learning and classroom interactions (De Angelis Citation2011). In the context of Germany, Heyder and Schädlich (Citation2014) found that foreign language teachers had overwhelmingly positive attitudes towards multilingualism; this, however, did not mean that they used it as a resource in their teaching. Gogolin (Citation2013) found that even when confronted with the reality of teaching multilingual students, teachers in Germany still tended to reconstruct the classroom as a monolingual space. Young (Citation2014) shows how teachers’ classroom practices in France are strongly influenced by their beliefs, which related to dominant monolingual ideologies of language. She thus emphasises that the beliefs teachers hold ‘will inevitably influence the language policies which they adopt at school and consequently impact on children’s learning’ (Young Citation2014, 157–158). We thus see researching beliefs of teachers as an important additional aspect to better understand how students’ abilities and their multilingualism is understood and considered in English language education, and what role this might play in teachers’ practices and the construction of educational disadvantage for students learning English in Austrian middle schools.

The current study

In this study, we present a quantitative exploration via questionnaire of the beliefs and classroom practices of English teachers at Austrian middle schools, focusing on the following research questions:

What are teachers’ beliefs about their students’ abilities to learn English?

What are teachers’ beliefs about their students’ motivations to learn English?

What are teachers’ beliefs about students’ access to English outside of school?

What are teachers’ reported language practices in the classroom?

We present descriptive and inferential analyses of the data to add depth to the contextual description that we have presented above, by revealing how teachers’ beliefs about their students’ abilities, motivations and access to English outside of school and teachers’ language use in the classroom all relate to the lower outcomes in English at Austrian middle schools.

Methodology

The methodological design of the quantitative aspect of our study draws on the contextual description above to explore the beliefs of Austrian middle school English teachers about their students’ abilities and motivations in English language learning, their beliefs about students’ access to English outside of school; and their reported language practices in the English language classroom. This research was undertaken in March-May Citation2019. Drawing on previous work that investigated teachers’ attitudes to multilingualism (e.g. Young, Citation2014) and beliefs about and attitudes towards English (Erling Citation2007), we developed an 88-item questionnaire. Questions – the majority of which required 5-point Likert-scale responses – were grouped thematically and covered topics such as teachers’ personal and educational background, their school environment, their beliefs about their students’ language backgrounds and abilities, motivations for learning English, access to English outside of school, as well as their own reported language practices in the classroom. All questionnaire items relevant for the current paper are presented in Appendix A. Fifty-six middle school teachers of English (93% female), recruited through various professional networks, volunteered to participate in this study. The data were collected anonymously, and the teachers’ identities and the schools in which they teach have been protected. All teachers were L1 German users, with 68% under 44 years old and with around 50% having six or fewer years of experience. Most (77%) work in schools in the federal state of Styria, 11% in Vienna, and only a few in Upper Austria (4%), Lower Austria (5%), Carinthia (2%) and Burgenland (2%). 45% of the teachers reported teaching in an urban area (which is likely to be more diverse and multilingual), 18% in a sub-urban area and 38% in a rural area.

We present both descriptive and inferential statistics. For the inferential statistics, we ran multiple linear regression analyses. The dependent variable in all analyses was the proportion of students that teachers believe to be achieving the learning outcomes for English (true for all/most/about half/some/none of my students), as we were particularly interested in which factors influenced teachers’ beliefs about their students’ English language achievements. As Likert-scale data is categorical (ordinal), we assumed that the distance between the categories for the dependent variable in our analyses is roughly equal. We believe that this is a reasonable assumption to make for 5-point Likert scales with a neutral midpoint. For each analysis, all independent variables were centred prior to analysis to minimise collinearity (Belsley, Kuh, and Welsch Citation2005). We then conducted systematic model comparisons, such that independent variables that did not contribute significantly to model fit were removed in a stepwise procedure (Baayen Citation2008). This yielded the final analysis models, for which we report results throughout. The complete questionnaire as well as the anonymised data and analysis scripts for the current study can be found on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/z53f9/).

Results

Overall, the questionnaire revealed that only 30% of the teachers (n=17) responded that their students are achieving the learning outcomes in English that they should at their level of schooling, which roughly equates to the findings of the 2019 BiST assessment (BIFIE Citation2020a). presents the percentage of students that teachers in rural, sub-urban and urban areas estimate as being LX German users. The majority of teachers (52%) indicated that 10% or less of their middle school students fall into this category. This percentage is relatively low when compared to the national statistics reported in . This discrepancy is likely due to the large number of teachers working in rural areas who participated in the study, where there is less (perceived) linguistic diversity. It could, however, also be attributed to teachers not being fully aware of their students’ language repertoires (as was found by Brummer Citation2019). Still, around a quarter of the teachers (23%) reported that 75% percent or more of their students are LX German users, and these were mostly teachers working in urban areas. The teachers reported a broad variety of languages spoken by their students, the most common of which were Arabic, Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian (BCS), Turkish, Kurdish and Slovene.

Table 2. Teachers’ (n = 56) estimates of the percentage of their students who are German LX users by area. Numbers represent numbers of teachers, with select percentages in parentheses

A multiple regression analysis explored whether the percentage of German LX users at the school (10% or less, roughly 25%, roughly 50%, roughly 75%, 90% or more) and the location of the school (urban, sub-urban, rural) relates to the percentage of students that teachers believed to be achieving the learning outcomes for English. The results revealed a main effect of percentage of German LX users (β = 0.20, SE = 0.07, t = 3.01, p = 0.004), showing that the larger the reported percentage of German LX users, the fewer students were reportedly achieving the learning outcomes for English, irrespective of school location.

We now present the results of investigating the following factors and their potential relationship to these low outcomes of English learning in middle school: teachers’ beliefs about their students’ language abilities and motivations to learn English; their beliefs about their students’ access to English outside school; and their own reported language practices in the classroom. and summarise teachers’ responses to the questionnaire items relevant for the following results sections.

Table 3. Teachers’ (n = 56) beliefs about their students’ English language learning. Numbers represent numbers of teachers, with percentages in parentheses.

Table 4. Teachers’ (n = 56) agreement with statements relating to their students’ English language learning and their own teaching practices. Numbers represent numbers of teachers, with percentages in parentheses.

Teachers’ beliefs about their students’ language learning abilities

Most of the teachers held fairly positive beliefs about their students’ abilities to learn languages, with 68% replying that at least half of them were good language learners. However, only 14% of teachers believe that most of their students are good at learning languages, and no teachers reported that all of their students are good at learning languages. This low confidence in students’ abilities is reflected in students’ above-mentioned low learning outcomes. While students may not be achieving their learning outcomes, a large number of teachers believe that English language education is helping their students to develop a better sense of language, with 93% (n=52) agreeing with this statement and 48% (n=27) even strongly agreeing. The teachers were less convinced that learning English supports learning German for LX German users: Less than half of the respondents (48%, n=27) agreed with this statement, with 43% (n=25) being uncertain and 9% (n=5) disagreeing.

A multiple regression analysis further investigated whether teachers’ beliefs about (a) whether learning English helps their students to develop a better sense of language in general, (b) learning English supports learning German for their LX German students (both: strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree) and (c) whether their students are good language learners (true for none/some/about half/most/all of my students) relate to learning outcomes. There was a significant main effect for (a) and (c), such that the more teachers agreed with the statements that learning English helps their students develop a better sense of language (β = 0.40, SE = 0.15, t = 2.76, p = 0.008) and that their students are good language learners (β = 0.34, SE = 0.13, t = 2.61, p = 0.012), the more students were reportedly achieving the learning outcomes for English, irrespective of teachers’ beliefs about the statement that learning English supports learning German for students with German as LX. Overall, these findings suggest relationships between teachers’ beliefs about their students’ abilities and students’ learning that warrant further investigation.

Teachers’ beliefs about their students’ motivations to learn English

The following analysis explores whether perceived variation in motivation can explain the disparity in learning outcomes between school types. Teachers indicate that middle school students like learning English, with 60% (n=34) agreeing that most or all of their students like English. The number who reported that most or all of their students were motivated to learn English was lower, at 45% (n=22), with a slight majority (52%, n=29) reporting that about half of their students were motivated to learn English.

A multiple regression analysis further investigated whether teachers’ beliefs about students liking English and being motivated to learn English (both: true for all/most/about half/some/none of my students) relate to learning outcomes. A significant main effect of motivation to learn English (β = 0.38, SE = 0.14, t = 2.70, p = 0.009) suggests that the more teachers believed that their students are motivated to learn English, the more students were reportedly achieving the learning outcomes for English, irrespective of teachers’ beliefs about how much their students liked English. Importantly, the findings do not provide insight into causation: It cannot be determined whether teachers’ beliefs about their students’ higher motivation leads to higher learning outcomes or whether lower learning outcomes in English means that the teachers believe their students to be less motivated.

Teachers’ beliefs about students’ access to English outside of school

We also explored whether the disparity in English language learning outcomes could be connected to teachers’ beliefs about students’ access to English outside of school. Only 7% of teachers (n=4) believed that most of their students regularly use English outside the classroom, and 16% (n=9) indicated that none of their students regularly used English outside the classroom. More than a quarter of the teachers (29%, n=16) believed that none of their students engaged in hobbies and extracurricular activities in English, and 16% (n=9) that none of their students regularly used English for travelling and holidays. Only three teachers (5%) believed that their students engaged in hobbies in English and regularly used English for travelling and holidays.

A multiple regression analysis further investigated whether teachers’ beliefs about their students (a) regularly using English outside of the classroom, (b) engaging in hobbies and extracurricular activities in which English is used, and (c) regularly using English for travelling or holidays (all: true for all/most/about half/some/none of my students) relate to learning outcomes. The analysis found that the more teachers believed students to be using English outside of the classroom (β = 0.28, SE = 0.12, t = 2.32, p = 0.024) and for travelling and holidays (β = 0.38, SE = 0.12, t = 3.34, p = 0.002), the more students were reportedly achieving the learning outcomes for English. Again, the analysis does not give insight into causation: It could be that teachers’ beliefs that students rarely engage with English outside of school are correct, and this is a reason for their students’ lower learning outcomes. It could, however, also be that students are discouraged from engaging with English outside the classroom because of their low learning outcomes. An additional option might be that teachers have misinformed beliefs or a lack of awareness of students’ out-of-school language practices in English. In any case, that so many teachers believe that their students do not regularly engage in hobbies and extracurricular activities in English or use English for travelling and holidays indicates that they view them as having fewer resources and opportunities to use English in this way.

Teachers’ reported language practices in the classroom

Our analysis of reported language practices in the classroom focuses on whether teachers use the target language only in the English language classroom, or whether they use German and/or any other languages as resources for teaching and learning. 43% of teachers (n=24) agreed that they do not use German in the classroom, with 23% (n=13) neither agreeing nor disagreeing, and 34% (n=19) agreeing that they use German in the classroom. Only 18% (n=10) of teachers agreed or strongly agreed that they encouraged students to use their first language(s) in the classroom, with substantially more teachers (43%, n=24) disagreeing or strongly disagreeing. The large number of teachers reporting that they only use English in the classroom is not surprising, given that their teacher education is likely to have promoted the idea that use of the target language only will have the maximum effect in language learning (cf. Sampson Citation2012).

A multiple linear regression analysis investigated whether teachers’ reported use of German in the classroom and of encouraging first language use in the classroom (both: strongly agree/agree/neither agree nor disagree/disagree/strongly disagree) relate to learning outcomes. The results show that the more teachers reported that they use German in the classroom (β = −0.25, SE = 0.09, t = −2.76, p = 0.008), the fewer students were believed to be achieving the learning outcomes for English, irrespective of teachers’ agreement with the statement that they encouraged students to use their first language(s) in the classroom. This finding could either indicate that more English input during class supports achievement in English, or that when teachers believe that their learners are struggling, they use more German to support them. Interestingly, the extent to which teachers reported that they encourage L1 use in the English classroom does not correlate with the percentage of LX German users in the classroom (β = −0.09, SE = 0.22, t = −0.39, p = 0.702). Finally, the fact that a relatively large number of teachers (39%, n=22) neither agreed nor disagreed with this statement suggests that teachers may not be sure whether or not first language use should be encouraged in the classroom and that, as a result, many teachers may not actively engage with students’ other languages.

Discussion

Our article closes by considering the significance of the findings for educational policy and practice in English language education in Austria, including ideas for the transformation of these. Applying an intersectionality lens in this study allows a deeper understanding of the complex range of factors contributing to middle school students’ lower levels of achievement in English, including teachers’ beliefs. Further research is clearly needed in this area, but the findings so far indicate that teachers believe their students are not achieving learning outcomes, particularly in cases where there are higher numbers of multilingual students in the classroom. Given that research has consistently confirmed the benefits of multilingualism with regard to additional language learning (Cenoz, Hufeisen, and Jessner Citation2001; Conteh and Meier Citation2014; De Angelis Citation2007; Jessner Citation2006), the question arises why middle school English teachers do not believe that this ‘multilingual advantage’ can be realised for their students who are LX German users. While teachers in this context believe that their students are good language learners and express the view that English language education can help them develop their sense of language awareness, they are less sure about the value of English language learning for supporting German learning. Teachers may therefore welcome further guidance about supporting simultaneous language learning, developing language awareness (cf. Hawkins Citation1984) and fostering cross-linguistic transfer in the English language classroom through translanguaging pedagogies (cf. Cenoz and Gorter Citation2020). Several approaches have been developed which can be drawn on in English language education that allow for the exploration of all existing languages and dialects in the classroom, in the surroundings and in society (including language of schooling, foreign languages, migration and heritage languages) and develop sensitivity to language(s) to increase confidence, motivation and ability in learning (Duarte and Günther-van der Meij Citation2018; Herzog-Punzenberger, Le Pichon-Vorstman, and Siarova Citation2017; Hélot et al. Citation2018).

Other factors which come up in this study as being potentially important are teachers’ beliefs about students’ motivations for learning English. Overall, teachers reported that their students liked learning English, though they do not believe that their students are highly motivated to learn it. The data reflected a relationship between teachers’ beliefs about their students’ motivation to learn English and their achievement. It cannot be determined from the data whether teachers’ beliefs about students’ language abilities and students’ lower learning outcomes are the cause or the result of the lower levels of motivation that teachers believe to exist, and more research needs to be conducted in this area. However, the findings indicate that leveraging and enhancing students’ motivations to learn English might be an important aspect of improving achievement in middle school. Related to this is the finding that teachers believe that students are rarely using English outside of school, not for hobbies and extracurricular activities, nor for travelling and holidays (cf. Gerdl Citation2019). The Austrian Standards-Based Test for English also found that middle school students and those from a migration background are less likely to engage with English media in their free time (BIFIE Citation2020a). Considering the prominent role that English plays in many European youths’ lives (Berns, de Bot, and Hasebrink Citation2007; Erling Citation2007) and in Austrian society (Smit and Schwarz Citation2019), these findings are surprising and clearly warrant further research. However, studies conducted in other contexts propose that students use English outside of school more than they and their teachers realise, and that their practices could be made more visible or be enhanced through school activities that explore the linguistic landscape (Sayer Citation2010), and students’ ‘funds of identity’ and out-of-school language practices (cf. Esteban-Guitart Citation2016; Rios-Aguilar et al. Citation2011). Such activities have been found to change teachers’ beliefs about students’ multilingualism and their out-of-school language practices, in that they come to better understand their students and their communities and appreciate the complexity of their language practices. Moreover, such activities develop students’ awareness of their own language practices, their confidence as successful multilinguals, and their awareness of how English might be beneficial in their communities and their futures, enhancing their motivations to learn it.

This study suggests that teachers’ language practices in the classroom, based on their beliefs about their students’ abilities and motivations, may also be contributing to lower outcomes: Many reportedly primarily use English as the language of the classroom, which is unsurprising given that their teacher education is likely to have promoted the use of target language only to enhance language learning (cf. Sampson Citation2012). However, more teachers responded that they draw on German in contexts where learning outcomes are reportedly lower. Whether the increased use of German might be a cause of or a response to the lower outcomes in English cannot be determined from the data and requires further investigation. However, the range in reported practice suggests that teachers would benefit from additional guidance about language use in the classroom and whether or not the use of the language of education (German) can be facilitative or disadvantageous for students who are LX users. Research conducted in a similar context, for example, found that students who are LX users reported to not be able to understand instructions in German, so using German to explain might not always be helpful (Brummer Citation2019). The current study also indicated that teachers do not seem to be engaging with students’ entire language repertoire to consolidate learning. These findings reflect that – despite multilingualism being a common feature of classrooms across Europe – multilingual education strategies are not yet a reality in most European classrooms (Herzog-Punzenberger Citation2017). Overall, our results are in line with previous studies showing that language teachers in German speaking contexts ‘advocate a multilingual pedagogical approach’, but ‘treat their multilingual classes like homogeneous monolinguals ones’ (Bredthauer and Engfer Citation2016, 104). Lohse (Citation2017) further argues that LX German users are disadvantaged in ‘foreign language’ education, since pedagogies were conceptualised for a homogenous German-speaking group of students: Teachers build on implicit knowledge about the German language and discussions about transfer issues take place solely in German. Language teachers across Europe are unlikely to have received much education on multilingualism as part of their teacher education nor any type of specialised training on multilingual education strategies (De Angelis Citation2011). Teachers’ insecurities about using German and other languages in the English language classroom might also be reinforced by misinformed beliefs, e.g. that the presence of other languages in the classroom interferes with successful language learning, that mixing languages indicates that a speaker is ‘confused’ and/or that language teachers should behave like monolingual native speakers who do not move across and between languages, as was found in other contexts (cf. Meier Citation2018).

The findings of this study indicate that teachers’ beliefs about their middle school students’ language abilities and motivation play a role in the disparity of outcomes in English language education in Austria. Adopting an intersectionality lens can help teachers and other stakeholders in education in this and similar contexts better understand the complex range of dynamics that influence their students’ learning, as well as a fuller awareness of the importance of their beliefs and practices in this (Atewologun Citation2018). This study indicates that English language teachers of students from multilingual, low SES backgrounds need further strategies for developing students’ motivation and confidence, developing their abilities to support simultaneous language learning, promote language awareness that can be applied across languages and foster cross-linguistic transfer in the English language classroom, drawing on students’ full language repertoire and out-of-school language practices. Changes in teachers’ practice go hand in hand with a shift in beliefs (OECD Citation2009), and could go some way in enhancing language education in Austrian middle schools and beyond, so that students at the intersection of disadvantage are not further disadvantaged by limited opportunities resulting from restricted access to English.

Conclusion

In this article, we have explored some of the factors contributing to lower outcomes in English language learning in Austrian middle schools, and whether, and if so how, lower socioeconomic status and students’ multilingualism plays a role in this. The lens of intersectionality provides novel insights into how the dual-track nature of the Austrian secondary education system contributes to the perpetuation of negative beliefs about multilingualism as an obstacle to academic achievement, while also masking the continued force of socioeconomic status in hindering upward mobility. Further, the quantitative findings from this study show how teachers’ beliefs about their students’ abilities, motivations and out-of-school language uses, as well as their language use in the classroom relate to lower outcomes in English at Austrian middle schools. Once positioned as low-status, low-achieving students by educational structures and teachers’ beliefs and practices, learners can find it very difficult to reject such positionings (see also Hempel-Jorgensen and Cremin Citationforthcoming). Intersectionality theory, however, can offer researchers and teachers sensitivity to the multiple factors affecting disadvantage and can thus maximise the chance of redressing them (Atewologun Citation2018). Our study adds weight to the research arguing that redressing educational disparities in Austrian education requires an overhaul of the dual-track system, as was the original intention of the 2008 reform. This would also provide more scope for the intentions stated in Austrian and European educational and language policies that promote equality, diversity and multilingualism to become a reality. As the structural change required does not seem likely to be enacted in the immediate future, in the meantime shifts are needed within pre- and in-service teacher education in Austria that better prepare English language teachers for teaching students of varied socioeconomic and language backgrounds. There is a need to further explore and transform teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism and how they intersect with socioeconomic status and their students’ uses of and needs for English in Austria and beyond. With English playing a central role in economic and social development globally (cf. Erling and Seargeant Citation2013), lack of equity in English language education is otherwise likely to continue to broaden socioeconomic disparities.

Supplemental Material

Download MP4 Video (26.9 MB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the teachers who participated in the questionnaire and Melanie Wiener for her support with the data processing and analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Atewologun, D. 2018. Intersectionality Theory and Practice. Oxford Research Excyclopedia of Business and Management. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Baayen, R. H. 2008. Analyzing Linguistic Data: A Practical Introduction to Statistics Using R. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Barcelos, A. M. 2003. “Researching Beliefs about SLA: A Critical Review.” In Beliefs about SLA. Educational Linguistics, vol 2, edited by P. Kalaja, and A. A. M. Barcelos, 7–33. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Beer, R. 2018. “Gabelung auf dem Bildungsweg.” ORF, January 22. https://orf.at/v2/stories/2427024/2422834/.

- Beer, R. 2019. “NMS vs. AHS: Wenn sich der Bildungsweg trennt.” ORF, February 11. https://orf.at/stories/3109447/.

- Belsley, D. A., E. Kuh, and R. E. Welsch. 2005. Regression Diagnostics: Identifying Influential Data and Sources of Collinearity, vol. 571. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Beranek, W. 2000. “Historische Aspekte zur Problemgeschichte der Hauptschule im österreichischen Schulwesen.” In Wieso “Haupt“-Schule? Zur Situation der Sekundarstufe I in Ballungszentren, edited by W. Weidinger, 34–57. Wien: öbv & hpt VerlagsgesmbH & Co KG.

- Berns, M., K. de Bot, and U. Hasebrink. 2007. In the Presence of English: Media and European Youth. Dordrecht: Springer.

- BIFIE. 2020a. Standardüberprüfung 2019. Englisch, 8. Schulstufe Bundesergebnisbericht. Salzburg. https://www.bifie.at/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/BiSt_UE_E8_2019_Bundesergebnisbericht.pdf.

- BIFIE. 2020b. Indikatorendatenbank des BIFIE. https://indikatoren.bifie.at/components/idb-form.

- BMBWF. 2018. Mittelschule. https://bildung.bmbwf.gv.at/schulen/bw/nms/index.html#heading_Aufgabe_der_Neuen_Mittelschule.

- BMUKK. 2012. NMS-Umsetzungspaket. BGBl. II. Nr. 185/2012. https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/eli/bgbl/II/2012/185.

- Borg, S. 2018. “Teachers’ Beliefs and Classroom Practices.” In The Routledge Handbook of Language Awareness, edited by P. Garrett, and J. M. Cots, 75–91. London: Routledge.

- Bredthauer, S., and H. Engfer. 2016. “Multilingualism is Great – but is it Really my Business? – Teachers’ Approaches to Multilingual Didactics in Austria and Germany.” Sustainable Multilingualism 9: 104–121.

- Brummer, M. 2019. “English Teachers’ Beliefs About Bi- and Multilingualism and How They Affect Their Language Learners.” Diploma thesis, University of Graz.

- Bruneforth, M., S. Vogtenhuber, L. Lassnigg, K. Oberwimmer, H. Gumpoldsberger, E. Feyerer, and B. Herzog-Punzenberger. 2016. “Indikatoren C: Prozessfaktoren.” In Nationaler Bildungsbericht Österreich 2015, Band 1: Das Schulsystem im Spiegel von Daten und Indikatoren, edited by M. Bruneforth, L. Lassnigg, S. Vogtenhuber, C. Schreiner, and S. Breit, 71–128. Graz: Leykam.

- Bruneforth, M., C. Weber, and J. Bacher. 2012. “Chancengleichheit und garantiertes Bildungsminimum in Österreich.” In Nationaler Bildungsbericht Österreich 2012. Band 2: Fokussierte Analysen bildungspolitischer Schwerpunktthemen, edited by B. Herzog-Punzenberger, 189–227. Graz: Leykam.

- B-VG. 2019. Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz. https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=10000138.

- Cenoz, J., and D. Gorter. 2020. “Teaching English Through Pedagogical Translanguaging.” World Englishes 39 (2): 300–311.

- Cenoz, J., B. Hufeisen, and U. Jessner. 2001. Cross-linguistic Influence in Third Language Acquisition: Psycholinguistic Perspectives. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Conteh, J., and G. Meier, eds. 2014. The Multilingual Turn in Languages Education. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Crenshaw, K. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1 (8): 139–167.

- De Angelis, G. 2007. Third or Additional Language Acquisition. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- De Angelis, G. 2011. “Teachers ‘ Beliefs About the Role of Prior Language Knowledge in Learning and How These Influence Teaching Practices.” International Journal of Multilingualism 8 (3): 216–234.

- Dewaele, J.-M. 2018. “Why the Dichotomy ‘L1 Versus LX User’ is Better Than ‘Native Versus Non-Native Speaker’.” Applied Linguistics 39 (2): 236–240.

- Duarte, J., and M. Günther-van der Meij. 2018. “A Holistic Model for Multilingualism in Education.” EuroAmerican Journal of Applied Linguistics and Languages 5 (2): 24–43.

- Erling, E. J. 2007. “Local Identities, Global Connections: Affinities to English among Students at the Freie Universität Berlin.” World Englishes 26 (2): 111–130.

- Erling, E. J., and P. Seargeant. 2013. English and Development: Policy, Pedagogy and Globalization. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Esteban-Guitart, M. 2016. Funds of Identity. Connecting Meaningful Learning Experiences in and out of School. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- European Commission. 2002. About Multilingualism Policy. https://ec.europa.eu/education/policies/multilingualism/about-multilingualism-policy_en.

- Eurostat. 2020. Data Explorer. Pupils by Education Level and Number of Modern Foreign Languages Studied - Absolute Numbers and % of Pupils by Number of Languages Studied (educ_uoe_lang02). https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=educ_uoe_lang02&lang=en.

- Expertenrat für Integration. 2019. Integrationsbericht: Integration in Österreich – Zahlen, Entwicklungen, Schwerpunkte. Vienna. https://www.bmeia.gv.at/integration/integrationsbericht/.

- Fend, H. 2009. “Chancengleichheit im Lebenslauf - Kurz- und Langzeitfolgen von Schulstrukturen.” In Lebensläufe, Lebensbewältigung, Lebensglück: Ergebnisse der LifE-Studie, edited by H. Fend, F. Berger, and U. Grob, 37–72. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

- García-Mateus, S., and D. Palmer. 2017. “Translanguaging Pedagogies for Positive Identities in Two-Way Dual Language Bilingual Education.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education 16 (4): 245–255.

- García, O., and J. A. Kleifgen. 2018. Educating Emergent Bilinguals: Policies, Programs, and Practices for English Learners. 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press.

- García, O., and T. Kleyn, eds. 2016. Translanguaging with Multilingual Students: Learning from Classroom Moments. London: Routledge.

- Gerdl, N. 2019. “Multilingualism in Austrian Secondary English Language Learning: Advantage or Obstacle?” Diploma thesis, University of Graz.

- Gilakjani, A. P., and N. B. Sabouri. 2017. “Teachers’ Beliefs in English Language Teaching and Learning: A Review of the Literature.” English Language Teaching 10 (4): 78–86.

- Glock, S., H. Kleen, M. Krischler, and I. Pit-ten Cate. 2020. “Die Einstellungen von Lehrpersonen gegenüber Schüler*innen ethnischer Minoritäten und Schüler*innen mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf: Ein Forschungsüberblick.” In Stereotype in der Schule, edited by S. Glock, and H. Kleen, 225–279. Amsterdam: Springer.

- Gogolin, I. 2013. “The “Monolingual Habitus” as the Common Feature in Teaching in the Language of the Majority in Different Countries.” Per Linguam: A Journal of Language Learning 13 (2): 38–49.

- Gruber, K. H. 2015. “Die Neue Mittelschule: Bildungs-Politologische und International Vergleichende Anmerkungen.” In Evaluation der Neuen Mittelschule (NMS). Befunde aus den Anfangskohorten, edited by F. Eder, H. Altrichter, J. Bacher, F. Hofmann, and C. Weber, 57–74. Graz: Leykam.

- Hall, C. J., and C. Cunningham. 2020. “Educators’ Beliefs About English and Languages Beyond English: From Ideology to Ontology and Back Again.” Linguistics and Education 57: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2020.100817.

- Haukås, Å. 2016. “Teachers ‘ Beliefs about Multilingualism and a Multilingual Pedagogical Approach.” International Journal of Multilingualism 13 (1): 1–18.

- Hawkins, E. 1984. Awareness of Language: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hélot, C., K. Van Gorp, C. Frijns, and S. Sierens. 2018. “Introduction: Towards Critical Multilingual Language Awareness for 21st Century Schools.” In Language Awareness and Multilingualism: Encyclopedia of Language and Education,edited by J. Cenoz, D. Gorter, and S. May, 1–20. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Hempel-Jorgensen, A., and T. Cremin. forthcoming. “An Intersectionality Approach to Understanding ‘Boys’ Engagement with Reading.”

- Herzog-Punzenberger, B. 2017. Migration und Mehrsprachigkeit – Wie fit sind wir für die Vielfalt? Vienna: AK Wien.

- Herzog-Punzenberger, B., E. Le Pichon-Vorstman, and H. Siarova. 2017. Multilingual Education in the Light of Diversity: Lessons Learned. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/404b34d1-ef63-11e6-8a35-01aa75ed71a1.

- Heyder, K., and B. Schädlich. 2014. “Mehrsprachigkeit und Mehrkulturalität – Eine Umfrage unter Fremdsprachenlehrkräften in Niedersachsen.” Zeitschrift für Interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht 19 (1): 183–201.

- Jessner, U. 2006. Linguistic Awareness in Multilinguals: English as a Third Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Krumm, H.-J., and H. H. Reich. 2013. Multilingualism Curriculum. Perceiving and Managing Linguistic Diversity in Education. Graz. http://oesz.at/download/Attachments/CM+English.pdf.

- Lohse, A. 2017. “Deutsch als Zweitsprache - (k)ein Fall für den Fremdsprachenunterricht?” In Fachintegrierte Sprachbildung. Forschung, Theoriebildung und Konzepte für die Unterrichtspraxis, edited by B. Lütke, I. Petersen, and T. Tajmel, 185–207. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Luciak, M. 2008. “Education of Ethnic Minorities and Migrants in Austria.” In The Education of Diverse Student Populations. Explorations of Educational Purpose, vol 2, edited by G. Wan, 45–64. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Lundberg, A. 2019. “Teachers’ Beliefs About Multilingualism: Findings from Q Method Research.” Current Issues in Language Planning 20 (3): 266–283.

- May, S. 2019. “Negotiating the Multilingual Turn in SLA.” The Modern Language Journal 103: 122–129.

- Meier, G. 2018. “Multilingual Socialisation in Education: Introducing the M-SOC Approach.” Language Education and Multilingualism 1: 103–125.

- Mohrenberger, R. 2015. “Die NMS Wird Schlechtgeredet, dabei hat die AHS Reformbedarf. Userkommentar vom 10. März 2015.” Der Standard. https://derstandard.at/2000012722321/Die-NMS-wird-schlechtgeredet-dabei-haette-die-AHS-Unterstufe.

- Nimmervoll, L. 2014. “Es war nicht zur erwarten, dass die Neuen Mittelschulen alle anderen überflügeln.” Der Standard. https://derstandard.at/1389859603035/Dass-Neue-Mittelschulen-alle-anderen-ueberfluegeln-war-nicht-zu-erwarten.

- Oberwimmer, K., M. Bruneforth, T. Siegle, S. Vogtenhuber, L. Lassnigg, J. Schmich, and K. Trenkwalder. 2016. “Indikatoren D: Output – Ergebnisse des Schulsystems.” In Nationaler Bildungsbericht Österreich 2015, Band 1: Das Schulsystem im Spiegel von Daten und Indikatoren, edited by M. Bruneforth, L. Lassnigg, S. Vogtenhuber, C. Schreiner, and S. Breit, 129–194. Graz: Leykam.

- Oberwimmer, K., S. Vogtenhuber, L. Lassnigg, and C. Schreiner. 2018. Nationaler Bildungsbericht Österreich 2018, Band 1. Das Schulsystem in Spiegel von Daten und Indikatoren. Graz: Leykam.

- OECD. 2009. Creating Effective Teaching and Learning Environments: First Results from TALIS. Paris: OECD. http://www.oecd.org/education/school/43023606.pdf.

- OECD. 2018. PISA. Equity in Education: Breaking Down Barriers to Social Mobility. Paris: OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264073234-en.

- Pajares, M. F. 1992. “Teachers’ Beliefs and Educational Research: Cleaning Up a Messy Construct.” Review of Educational Research 62 (3): 307–332.

- Pit-ten Cate, I. M., and S. Glock. 2018. “Teacher Expectations Concerning Students with Immigrant Backgrounds or Special Educational Needs.” Educational Research and Evaluation 24 (3-5): 277–294. doi:10.1080/13803611.2018.1550839.

- Rechnungshof. 2013. Bericht des Rechnungshofes. Modellversuche Neue Mittelschule. https://www.rechnungshof.gv.at/rh/home/home/Modellversuche_Neue_Mittelschule.pdf.

- Rechtsinformationssystem des Bundes. 2020a. Gesamte Rechtsvorschrift für Lehrpläne - Neue Mittelschulen. https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=20007850.

- Rechtsinformationssystem des Bundes. 2020b. Gesamte Rechtsvorschrift für Lehrpläne – allgemeinbildende höhere Schulen. https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=10008568.

- Rios-Aguilar, C., J. M. Kiyama, M. Gravitt, and L. C. Moll. 2011. “Funds of Knowledge for the Poor and Forms of Capital for the Rich? A Capital Approach to Examining Funds of Knowledge.” Theory and Research in Education 9 (2): 163–184.

- Sampson, A. 2012. “Learner Code-Switching Versus English Only.” ELT Journal 66 (3): 293–303. doi:10.1093/elt/ccr067.

- Sayer, P. 2010. “Using the Linguistic Landscape as a Pedagogical Resource.” ELT Journal 64 (2): 143–154.

- Schreiner, C., B. Suchań, and S. Salchegger. 2020. “Monitoring Student Achievement in Austria: Implementation, Results and Political Reactions.” In Monitoring Student Achievement in the Twenty-first Century, edited by H. Harju-Luukkainen, N. McElvany, and J. Stang, 65–77. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Smit, U., and M. Schwarz. 2019. “English in Austria: Policies and Practices.” In English in the German-Speaking World, edited by R. Hickey, 294–314. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Statistik Austria. 2019. Schulstatistik. Schülerinnen und Schüler mit nicht-deutscher Umgangssprache im Schuljahr 2018/19. https://www.statistik.at/wcm/idc/idcplg?IdcService=GET_PDF_FILE&RevisionSelectionMethod=LatestReleased&dDocName=029650.

- Tefera, A. A., M. M. Powers, and G. E. Fischman. 2018. “Intersectionality in Education: A Conceptual Aspiration and Research Imperative.” Review of Research in Education 42 (1): vii–xvii.

- Tobisch, A., and M. Dresel. 2020. “Fleißig oder faul? Welche Einstellungen und Stereotype haben angehende Lehrkräfte gegenüber Schüler*innen aus unterschiedlichen sozialen Schichten?” In Stereotype in der Schule, edited by S. Glock, and H. Kleen, 133–158. Amsterdam: Springer.

- Tsiplakides, I., and A. Keramida. 2010. “The Relationship between Teacher Expectations and Student Achievement in the Teaching of English as a Foreign Language.” English Language Teaching 3 (2): 22–26.

- Walker, A., J. Shafer, and M. Iiams. 2004. “‘Not In My Classroom’: Teacher Attitudes Towards English Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom.” NABE Journal of Research and Practice 2 (1): 130–160.

- Wiesinger, S. 2018. Kulturkampf im Klassenzimmer: Wie der Islam die Schulen verändert. Vienna: Edition QVV.

- Young, A. S. 2014. “Unpacking Teachers’ Language Ideologies: Attitudes, Beliefs, and Practiced Language Policies in Schools in Alsace, France.”Language Awareness 23 (1–2): 157–171.

Appendix A

Questionnaire items analysed in the current study.

Biodata section:

6. My school is in:

▢ A rural area

▢ An urban area

▢ A sub-urban area

7. What percentage of your students would you estimate as having German as a second language?

▢ 10% or less

▢ Roughly 25%

▢ Roughly 50%

▢ Roughly 75%

▢ 90% or more

English teaching & learning section:

13. Your students’ English learning:

Below are statements about your students’ English learning. Please indicate whether these statements are:

▢ 1 = true for all of your students

▢ 2 = true for most of your students

▢ 3 = true for about half of your students

▢ 4 = true for some of your students

▢ 5 = true for none of your students

13.1. My students are good language learners.

13.2. My students like English.

13.3. My students are motivated to learn English.

13.4. My students are achieving the learning outcomes in English that they should at their

level of schooling.

14. Your students’ needs for English:

Below are statements about your students’ needs for English that you may agree or disagree with.

Using the 1–5 scale, indicate your agreement with each item:

▢ 1 = strongly agree

▢ 2 = agree

▢ 3 = neither agree nor disagree

▢ 4 = disagree

▢ 5 = strongly disagree

14.7. Learning English helps my students to develop a better sense of language in general.

14.8. Learning English supports learning German for my students with German as a

second language.

15. Your students’ practices outside of school:

Below are statements about your students’ practices outside of school. Please indicate whether these statements are:

▢ 1 = true for all of your students

▢ 2 = true for most of your students

▢ 3 = true for about half of your students

▢ 4 = true for some of your students

▢ 5 = true for none of your students

15.1. My students regularly use English outside of the classroom.

15.2. My students engage in hobbies and extracurricular activities in which English is

used.

15.3. My students regularly use English for travelling and holidays.

16. Your students’ beliefs and mindsets:

No items from this subsection are analysed in the current paper.

17. Your students’ parents:

No items from this subsection are analysed in the current paper.

18. Your school environment:

No items from this subsection are analysed in the current paper.

19. Your English language teaching practices:

Below are statements about your English language teaching practices that you may agree or disagree with. Using the 1–5 scale, indicate your agreement with each item:

▢ 1 = strongly agree

▢ 2 = agree

▢ 3 = neither agree nor disagree

▢ 4 = disagree

▢ 5 = strongly disagree

19.1. I regularly use German in the English language classroom.

19.9. I encourage students to use their first language(s) in the classroom.

20. Your needs:

No items from this subsection are analysed in the current paper.

21. Other

No items from this subsection are analysed in the current paper.