ABSTRACT

From January 2017 until January 2020, the Stormont assembly in Northern Ireland was suspended, with the Irish language being cited as the main stumbling block to the restoration of government. The continued debate around the necessity of an Irish Language Act (ILA) for Northern Ireland is bound up with more general divisions in society surrounding national identity, and as such, it divided political parties and the nationalist and unionist communities from which they draw their support. Through the analysis of ethnographic interviews conducted in various language learning centres across Belfast, I explore how this debate around legislating for the language impacted on the engagement of learners with the language in the city. By considering the role played by the media in the engagement of interview participants with the Irish language in Belfast, I aim to examine how the policy delay and political discourse affects those engaging with the language. This paper aims to address changing attitudes to the Irish language in Belfast in a period of political crisis, and what it means for those who use the language.

Introduction

From January 2017 until January 2020, the Stormont assembly in Northern Ireland was suspended, with the Irish language being cited as the main stumbling block to the restoration of government. The debate around the necessity of an Irish Language Act (ILA) for Northern Ireland is bound up with more general divisions in society surrounding national identity, and as such, it has divided political parties and the nationalist and unionist communities from which they draw their support.

Through the analysis of ethnographic interviews conducted in various language learning centres across Belfast, I will explore how this debate around legislating for the language has impacted on the engagement of learners with the language in the city. By considering the role played by the media in the engagement of interview participants with the Irish language in Belfast, I aim to examine how the policy delay and political discourse affects those engaging with the language.

This paper considers how those learning Irish feel about a language act, and questions how the language is being used as a tool in developing social cohesion in Northern Ireland.

The background

The state of Northern Ireland was formed in 1922 when the Republic of Ireland gained independence from Britain. The six north-easterly counties remained part of the union, thus forming the state of Northern Ireland (Mulholland Citation2002). At the establishment of the State, there was a majority Protestant population, who were largely loyal to Britain, and a minority Catholic population, who mainly wanted to be reunified with the Republic of Ireland. This sectarian divide along religious lines has resulted in tension and conflict in the area since the formation of Northern Ireland (Darby Citation1976). The divisions came to a head in 1968 with the civil rights movement, and the beginning of the period known as the Troubles.Footnote1 The Troubles was a 30-year civil conflict marked by extreme violence between the Catholic and Protestant communities in the area, that resulted in the deaths of more than 3,500 people and many more injured. It marked a period of deep social divisions across Northern Ireland that resulted in religious segregation at all levels of society. The effects of the divisive society and trauma associated with the violence of the conflict are still being dealt with today.

In 1998, the Good Friday Agreement was signed, restoring peace in Northern Ireland. The agreement was built on a foundation of parity of esteem with the progress towards reconciliation mapped out (see Coulter and Murray Citation2008). The agreement introduced a power-sharing system government, based on a consociational mode of democracy with both of the main parties from each community sharing power. The DUP, representing the Protestant, Unionist, Loyalist (PUL) community, and Sinn Féin, representing the Catholic, Nationalist, Republican (CNR) community form the largest parties representing each community.

The Good Friday Agreement has resulted in a relatively stable peace in the area for twenty years. However, as a society emerging from conflict, many of the issues between the two main communities have not been fully addressed or resolved, and underlying tensions remain between the two communities. This has become particularly evident over the past three years, as in January 2017 the Assembly (local government) collapsed. The power-sharing model failed due to disagreements over a number of factors, most notably sparked by a renewable heating incentive scandal, and the failure to address issues of equality, including the status of the Irish language (The Irish Times Citation2017). The failure to restore government however has been cited as being caused primarily by failure to meet demands for an Irish Language Act. The Irish language is still associated with, and perceived to ‘belong to’ the Nationalist community, and has become a proxy for other cultural issues that have not been dealt with since the peace agreement.

It is in this context that we look at the implications that the discourse around the implementation of an Irish language act has had on those wishing to engage with the language.

Languages in Northern Ireland today

According to census data from 2011 (NISRA Citation2011, Citation2014), 10.65% of the population report to have some ability in Irish, with 8.08% reporting to have some ability in Ulster Scots.Footnote2 Focusing on the languages of Northern Ireland, the community divisions are still reflected in the perceptions around language (Mac Póilín Citation1997). Generally, Irish has long been perceived to ‘belong’ to the Nationalist community, and some members of the Protestant Unionist Loyalist (PUL) community identify with Ulster Scots, where it is used mainly along the northern coast of Antrim and the Ards peninsula (Mac an Bhreithiún and Burke Citation2014). Both languages have been used in the politicking as cultural symbols of particular communities. As such, language is still seen to be divisive, and identity claims along sectarian lines still mark the languages of Northern Ireland (Crowley Citation2016).

While the Irish language thrived among enclaves of the Republican and Nationalist community in prisons during the Troubles and after (Mac Giolla Chríost Citation2012; Mac Ionnrachtaigh Citation2013), others worked towards increasing the presence of Irish in community life. Many grassroots initiatives contributed to raising the profile of Irish in the North, and encouraging speakers and learners to use the language. The Shaws Road Gaeltacht was established in 1969 by local families as a means of raising their families through Irish (Nig Uidhir Citation2006), leading to further developments for the language including the opening of schools, leading to mainstream Irish immersion schools (Maguire Citation1991; Ó Baoill Citation2007). The founding of Irish cultural centres in Belfast and Derry and the emergence of various community organisations (Mitchell and Miller Citation2019) with a focus on Irish language and culture sought to reclaim the place of Irish in society and its role in everyday life. The legacy of the conflict has placed the language in a politically precarious position where it has been used as a proxy for other issues tied to identity and sectarian divisions. The learning of Irish has traditionally remained within the enclave of the Nationalist heartland of the Falls Road in west Belfast. However, as we explore in this study, such a stereotypical assumption of the Irish language learner in Belfast is outdated and can be harmful to the progress of the language and society more broadly (Pritchard Citation2004).

In 2001, the UK ratified the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages with regard to Irish and also to Ulster Scots, but in a limited capacity; Ulster Scots is only ratified under Part II (article 7) of the Charter, in which it is recognised as a regional minority language within Northern Ireland, granting it the same level of recognition as Scots in Scotland, and sets out objectives for the facilitating of the language in public life and respect for the language.

Irish is ratified under Part II and Part III, which in addition to the recognition of the language, outlines measures by which the use of the language must be promoted in public life, including education, judicial authorities, administrative and public authorities, media, economic, cultural and social life, and transfrontier exchanges (including cross-border relations) (ECRML Citation1992).

Northern Ireland was without a functioning Assembly for three years from 2017 until 2020, with the failure to reach an agreement across parties in Stormont largely blamed on the inability among the politicians to agree on an Irish Language Act or Cultures Act, along with disagreement over the reform of the petition of concern mechanism and addressing the legacy of the Troubles. Some parties, the Nationalist Sinn Féin in particular, claimed that an Irish Language Act is necessary to support and protect the language in Northern Ireland, and that the provision for such an Act was established in the St. Andrews Act (Ní Chuilín Citation2017). Other parties claim the Irish language already receives sufficient funding and support from government, and that legislation for the language is unnecessary and divisive. The division falls mainly along sectarian lines; the unionist parties, namely DUP, has been reluctant to support an Act and have actively implemented regressive policies with regard to the language, such as removing funding from the Líofa scheme (The Detail Citation2017). The nationalist parties, Sinn Féin and the Social Democratic and Labour Party, have traditionally been in favour of legislation, with the former Sinn Féin leader Martin McGuinness citing the failure to legislate for the language among the reasons for his resignation as Deputy First Minister (The Irish Times, January Citation2017).

In January 2020, government was restored in Northern Ireland with all parties agreeing to the New Decade, New Approach strategy (Citation2020). The document outlines a commitment to legislation to promote ‘parity of esteem, mutual respect, understanding and cooperation’ of different national and cultural identities in Northern Ireland. This new proposed framework establishes an Office of Identity and Cultural Expression, with the responsibility to promote cultural pluralism and respect for diversity, build social cohesion and reconciliation and to celebrate and support all aspects of Northern Ireland’s cultural and linguistic heritage. It paves the way for legislating for official status for Irish and Ulster Scots for the first time in Northern Ireland, and the establishment of two commissioners, one for Irish and one for Ulster Scots. The duty of the Irish commissioner includes the protection and enhancement of the development of the use of Irish by public authorities, while the commissioner for Ulster Scots will be tasked to enhance and develop language, arts and literature associated with Ulster Sots and Ulster British tradition in Northern Ireland, thus ambiguating the terms used to refer to that culture, while expanding the concept beyond language. Although the deal does not address many of the issues put forward by those who advocated for an Irish Language Act, including the issue of signage, it does for the first time provide for official status for the language, legal protection and an Office of the Irish Language Commissioner, and repeals the 1737 Act which made it illegal to use Irish in the Courts.

The New Decade, New Approach does not fulfil the commitments to the Irish language that were outlined in the St. Andrew’s Agreement (Citation2006) (see Ó Mainnín Citationforthcoming). During the three-year period of government stalemate, there were no clear indications as to what an Act may entail. There were leaked documents (Mallie Citation2018), and proposals for an Act put forward by Irish language organisations (Conradh na Gaeilge Citation2017; DCAL Citation2015; Pobal Citation2012), but overall, the details of what the parties were negotiating was unknown to the general public. As such, it was the idea of a Language Act, as opposed to specific elements of an Act, that was the centre of debate.

Based on the language acts and legislation that are in place in other jurisdictions of the United Kingdom, the main tenet of legislation for Northern Ireland would be that the language would have recognised, official status, which would mean the language could be used in spheres of public life where it currently is excluded, such as the courts, in communication with public services and further support and promotion in education. For speakers of the language, this would enable them to use Irish in more aspects of their lives, and feel that the language is more supported. It has been said by some who do not speak Irish, and may not identify with it, that an Act would disadvantage them, particularly from the point of view of getting jobs in the public sector should a quota of Irish speakers be enforced. There is also a fear of feeling alien in your home, with a major emphasis in the media discourse placed on signs and the languages included on signage. The long-term goal of those advocating for a language act for Irish would be that such legislation would contribute to the normalisation of the minoritised language and to multilingualism as a whole, while also helping to advance the party political depoliticisation of the language.

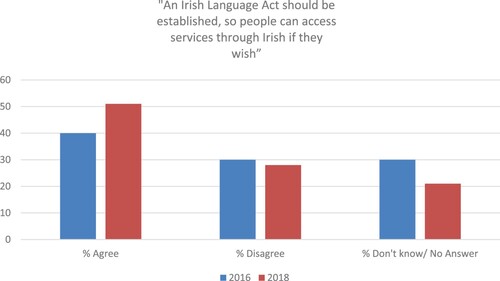

The provision for a language act has proven to be a divisive topic and attitudes towards it differ broadly. In a survey conducted for Conradh na Gaeilge (Céard é an Scéal) in 2018 (Conradh na Gaeilge Citation2018), using a representative sample of 2000 people as determined by age, gender, geographical location, social class and, in the North, religious beliefs, 51% of participants in Northern Ireland believed there should be an Irish Language Act to make services available through Irish for those who wish to use them, 28% disagreed and 21% did not know or did not answer (see ). 47% of participants in Northern Ireland believe that the State should do more to support the Irish language, with 55% also of the opinion that public services should be made available through Irish for those who wish to avail of them. 67% of participants in Northern Ireland support that Irish medium education should be available to every child, if that is their choice. The same question was asked about a language act in the 2016 survey (Conradh na Gaeilge Citation2016), with 40% responding in favour of an Act then, 30% against and Act and 30% did not know or did not answer (see ). As such, in the two-year span between surveys, we see that although the number of those who disagree with there being a need for an Irish Language Act has remained relatively stable, those in favour of an Act has increased by over 10%, and those with no opinion or choosing not to answer decreased by a similar amount. This reduction in those not answering or without an opinion may be partly attributed to the intense media debate and focus around the Irish Language Act discussions, resulting in more people forming an opinion or at least being aware of the issues at hand.

Methodology

The research presented in this present study emerged while the researcher was involved in a larger project exploring attitudes and perceptions to multilingualism as a tool for social cohesion in Northern Ireland more generally. However, the debate around the Irish Language Act emerged as what Agar (Citation1995) terms a ‘rich point’ in ethnography. As observations for the project progressed, it became clear that the issue of legislating for the Irish language was having an impact not only on the level of press coverage the language was receiving, but also on how and if people were engaging with the language. In order to explore factors affecting attitudes towards an act more thoroughly, interviews were conducted with adults attending Irish language classes in Belfast. Ethical approval was granted by the researcher’s institution through the formal research ethics procedure in advance of the commencement of data collection phase of the research.

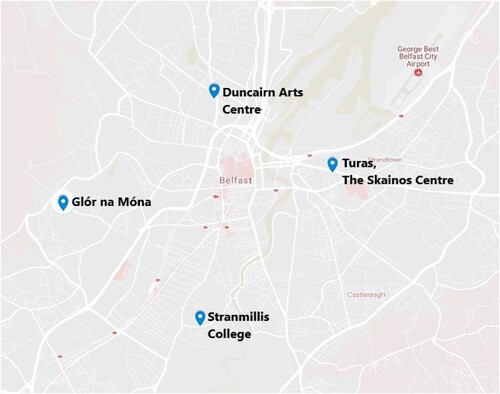

The language class providers that participated in the study were spread across the city, as seen in . In north Belfast, the most mixed neighbourhood in the city, classes run in Duncairn Arts Centre on a donation basis. In west Belfast, a largely nationalist area where the Gaeltacht quarter is located, the classes were provided by Glór na Móna, the Irish language and community organisation, and were based in their community centre, Gael-Ionad Mhic Ghoill on Whiterock Road during the day, and at the nearby gaelscoil, Gaelscoil na Móna, in the evenings. The classes run by Ian Malcolm in south Belfast based in Stranmillis College participated in this research as did Turas, the Irish language organisation based in the Skainos centre in the loyalist Newtownards road in east Belfast, which has previously been the focus of research (Mitchell and Miller Citation2019). Ian Malcolm is a well-known local musician and radio DJ from the PUL community. He is also an academic who has written a book focussing on Protestants and the Irish language in Northern Ireland (Malcolm Citation2009). Linda Ervine established Turas, the Irish language class provider and community organisation based at the East Belfast Mission on the Newtownards Road. She comes from a well-known Unionist family, her husband and brother in law having both been leaders of the Progressive Unionist Party with family connections to the loyalist paramilitary UVF (Ulster Volunteer Force), so she is closely associated with unionist politics. Linda herself has become a spokesperson for the promotion of the Irish language and rights of Irish language speakers among the PUL community. Although she is deeply rooted in the unionist community, she has become a prominent advocate for the Irish language in Northern Ireland and for promoting the language as a tool for social cohesion across communities (see Ervine Citation2019).

The classes chosen for the study tended to be based in community centres and not solely educational institutions. In north, west and east Belfast, the language groups that participated in the study were based in multipurpose community centres. Although in south Belfast the classes are based at an educational institution, they are not affiliated or organised by the college. In the local community, the college is used for other purposes and rooms are rented and made available to community groups. Classes offered by these providers are inexpensive, varying from donation only at two venues (Dun Cairn and Skainos) to nominal charges of £25–£30 for a term at Glór na Móna and the most expensive being the courses in south Belfast at approximately £60 a course. However, overall the classes are accessible to the majority of the local communities. In each case, the classes run concurrent with school terms for ten to twelve weeks with classes one evening per week, and a learner can register a term at a time, minimising the required commitment.

An ethnographic approach was taken to the fieldwork, as at a time of increased attention and tensions around Irish and its role in society, a degree of sensitivity and understanding was vital so as to be able to conduct deep, semi-structured interviews with the adult learners of Irish attending these classes in Belfast. Ethnography promotes a greater reflection on the world around us (Wells et al. Citation2019), and in the context of this research, it also contributes to a decentring of conventional stereotypes around languages in Northern Ireland. Through the building of accounts around the emic perspectives of participants (Da Costa Cabral Citation2018, 280) the researcher was able to construct a deeper understanding of such a politically sensitive context. An ethnographic approach was deemed most appropriate so that, as someone who is not from Northern Ireland, I could gain a better understanding of the communities and the nuanced perceptions around the language. By taking a slower approach to the fieldwork, over the period of over one year and a half, I gained a more acute understanding, through extensive observation of and participation in the language classes, of the socio-political situation in the field and the sensitivities that needed to be considered around approaching some learners who have been directly affected by the violence of the Troubles, including ex-prisoners. This approach also enabled me to gain the trust of participants and build a rapport so that our conversations could delve beyond the superficial. An ethnographic approach emphasises the importance of the triangulation of emic and etic perspectives (Duff Citation2008, 113) and of including the local voice in our interpretation of what is going on in a community (Goffman Citation1974).

After gaining familiarity with the learners through my involvement in classes and the community centres in general, I developed a level of trust and interviews were conducted with those willing to participate in the research. Having gained permission from each of the course providers to attend the classes and engage with their learners for my study, I began attending the classes and observing. All learners were given an information sheet about the research at the first class I attended so that they were aware from the start of my main motivation for being there, and they were able to speak to me in an informal setting before deciding if they wished to be involved in the study. All participants gave informed oral consent prior to the commencement of interviews and were free to withdraw at any time should they wish. The nature of the conversations and speech data collected were at times of a sensitive or private nature and so it was important to ensure the confidentiality of all who participated. As such, all personal information and interview transcriptions were recorded confidentially, and conducted in a manner that the identity of the speaker cannot be linked to his/her recording.

Interview topics were informed by the extensive observations that had been carried out. By observing the classes over prolonged period (returning weekly to the groups over the course of the fieldwork) participants became familiar with me and grew more comfortable with the idea of a researcher being present as I participated as a student in the classes, despite having proficiency in the language. As an outsider to the community, I was in a position to place myself as a student rather than be viewed as a person with authority in the class. The participants understood I had some proficiency in Irish, but recognised the different dialect that I had to Ulster Irish. All participants knew I was not from the area, and accepted me as another student and participant in the class without difficulty.

It was through the observation that I formed ideas of what to ask and importantly, in how to ask them. As someone not from the North, I was unfamiliar with the nuances and political sensitivities in lexical choice, such as terms to use with particular individuals and terms to avoid (e.g. The North v. Northern Ireland; words used to allude to aspects of life such as prison, each of the communities etc). The importance of this knowledge of the sensitivities around language should not be underestimated as the use of the wrong term could have resulted in a less successful interview, or indeed in participants no longer wishing to be involved.

The interviews were of approximately an hour in length and were conducted at places that were convenient to the participant, usually in a café connected to or near to the venue where they attended the language classes. The interviews consisted of discussions around the language, experiences with Irish and other languages growing up and how the participant sees the community change in relation to language attitudes and opinions. Here, I was interested in understanding the role the language plays in concepts of identity for learners from different backgrounds in Belfast. Often the issue of an Irish Language Act emerged organically in the conversation, and I was particularly interested in how the debate around legislating for the Irish language impacted public opinions of the language and how the policy delay and political discourse affected them personally as someone who was engaging with the language.

Accessing the language

In the following sections I will explore how the discourse around, and attention to, a possible language act impacted the motivations of learners of Irish in Belfast. Through a thematic analysis of the interviews conducted, I explore how the media attention given to the language and the increased awareness of the availability of language classes has motivated people to learn more about the language, to self-reflexively explore their own relationship with the language and its role in their identity, and how those learning Irish wish their engagement with the language to influence social cohesion in their society.

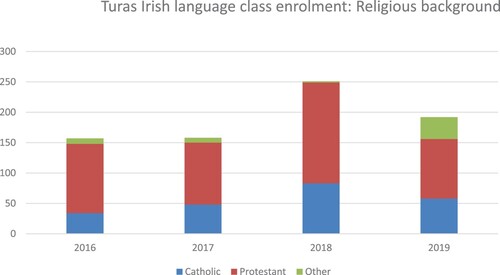

I will focus on enrolment patterns at one of the participating centres in order to hypothesise that the increased attention to the Irish language has resulted in an uptake of people learning Irish. As the largest provider of Irish language classes in Belfast, the information on enrolments at Turas can be indicative of engagement across communities.

As is evident in , there has been a clear increase in enrolment at Turas. This centre is of particular interest because it is based in a predominantly loyalist, working class area, which would traditionally be considered to be hostile towards the Irish language. However, since the collapse of Stormont, and the increased debate about the role of Irish in public life, the enrolment numbers have increased significantly. In 2018, enrolment numbers were at a high of over 250 people. Although numbers dropped in 2019 to192, there is a stark increase in the number of learners identifying as ‘other’ religious background. In the course of three years, those reporting to be ‘other’ increased from 5.7% to 18.75% of the total number of enrolled learners. Although the number of learners from the Catholic community saw an increase in 2017 from 22% to 30% of learners enrolled at Turas, the number remains around a third of the total learners from 2017 to 2019. Member of the Protestant Unionist Loyalist community are the biggest group attending Turas, which would be expected due to its location in a loyalist area in east Belfast, in a building shared with a Methodist church. However, the numbers of learners reporting to be from the PUL community in 2019 was 51% of the total number of learners, due to the increased numbers of those reporting to be ‘other’, i.e. not belonging to either the CNR or PUL communities.

These statistics are supplied by the language class provider based on a self-reporting registration form that includes explicit demographic questions regarding religious background, social class, gender, and education level. Although retention numbers of learners are not recorded by the language class provider, based on my involvement with the classes and attendance at the centre over the course of a year and a half, the retention numbers are high, with low dropout rates at beginners’ level and almost full retention at higher levels.

Most of those from the PUL community are engaging with the Irish language for the first time. In Catholic-maintained schools, Irish is normally included in the curriculum, however it is very rare that it is accessible to students outside of the Catholic-maintained education system (Mercator Education Citation2004). The figures in are indicative of engagement with the language across communities and a changing society. Despite the preconception that Irish is a language used and spoken by the CNR community, we see there is a level of interest among members of the PUL community.

It can be hypothesised that the media attention surrounding the Irish language during the political stalemate in 2017 and 2018 in particular led to an increased awareness among the general public about language classes and the possibility of learning Irish. Although some of those who accessed classes may have been interested in or curious about Irish before, the increased attention in public discourse around the Act and the status of the language in society led to the learner pursuing this undeveloped interest. For others, the debate around the language sparked an interest in finding out more about the language and its role in society. It is due to the attention given to the variety of language classes running across the city, and especially the media focus on Linda Irvine and classes in east Belfast, that many participants became aware of the possibility of attending classes all over the city. Learners were able to actively pursue learning the language because of this, whereas previously that information may have been more difficult to access. When asked why he decided to learn Irish, one participant attending classes in south Belfast stated

Probably a lot of it could be down to the publicity. It’s on TV at the minute, probably the front of your mind, so you think ‘right, I want to give this a go’.

So, all this publicity, as you put it, hasn’t put you off Irish?

No, actually it probably put it to the forefront, it made me decide to do it. You know, like anything I think, it’s something in the media a lot and has you thinking about it, then you’re more interested in it and ya end up deciding, you know, what’s all the fuss about, I want to look at it more.

I want to, by osmosis almost, to create in my kids’ minds the fact that something like that [Irish] wasn’t bad or good … They’re starting to use the odd word or phrase now. So rather than seeing it as something alien, they see it just as part of the island’s rich tapestry.

Linda, I think she’s is the best person to [be at] Skainos. I don’t know whether it would work as well with anybody else because of her sort of background and things, you know, she’s got credentials in the local community, so she can get away with teaching Irish and all the stuff she does.

Following Gardner and Lambert (Citation1972), language and language learning in divided communities can improve intercultural communication and affiliation. This is evident in the case of Irish learners in Belfast as participants refer to opening their minds to the ‘other’ and travelling to parts of the city that they would never have gone to before, mainly arising from a fear of the other community. Learning Irish has opened the possibility of connecting with people with different beliefs to them, and in widening their social network in ways that, to them, would have previously seemed implausible.

Learners spoke about teachers travelling from west Belfast being the first people that they have met from the area (and thus inferring the only Catholic Nationalists they have met), despite living in the same city. Thus, the cross-community interaction of the classes is important on a broader social level as it breaks down barriers between communities through engagement with the shared heritage of the Irish language. Likewise, learners spoke about the importance of having accessible classes in a location where they feel comfortable, rather than crossing the city into a different community, which for a lot of people is still something they would not habitually do. Prior to information being widely available regarding Irish language classes in other parts of the city, many learners assumed that if they wanted to learn Irish they would have to travel to west Belfast and to the Gaeltacht quarter to attend classes, and associated those classes with a Republican persuasion. However, having the possibility to attend classes in many parts of the city has encouraged people to engage with the language and to see it more as a part of their shared heritage among the communities.

Well I could have done it for example in the Falls Road in the Culturlann or something. And I thought, I know a lot of people that do it there. And then I seen Stranmillis and I thought I’ll do it there, there’ll be a mixed crowd, be a bit different, and the guy, then I looked in to Ian as well who takes the course and I thought interesting background and like you’d never expect someone like, with his background, to be teaching Irish. So, I suppose that’s what drove me to that particular class

ILA impact on learners

The increased attention given to the Irish language in the media and in wider public discourse on an Irish language act did not negatively affect the majority of participants decision to attend classes. However, some participants reported that they still did not feel comfortable publicising their attendance at Irish classes among their neighbours, family and friends. This secrecy around engaging with the language was also observed by the researcher at classes, as a number of learners would opt out of being part of any class photographs or choose not to engage with any media outlets or publicity, so as to not be identified as attending classes. Despite coming to classes, and participating in all aspects of the class, some participants expressed a cautious approach about attending:

I mean I wouldn’t broadcast it all down our street, we still put the flags up for the 12th you seeFootnote5 so no, one or two people would know but I wouldn’t tell everyone because you’re never quite sure here what way the tide is going to flow or when it’d come back to bite you.

And would that be a worry for you, for a lot of people then?

I think that’s always at the back of people’s minds because there was a policeman that lived down the road from us but there was a certain time when the tide turned against them and they got put out of their houses, so you know [uncomfortable laughter] you just, it’s a bit mad.

For others, the attention given to the Irish language and the Act, and the debate around ‘who’ is an Irish speaker encouraged them to confront the traditional stereotypes of the Irish speaker in Northern Ireland. As with the participant below, it made them more intent on confronting traditional stereotypes of ‘who’ is an Irish speaker.

All the debate and media attention around the Act, did it make you hesitant to come to classes?

It made me more determined!

It made you more determined?

Yes. Because I thought, I thought ‘no, politicians don’t get to do that. Politicians don’t get to tell me what’s good and what’s bad’. Hence the two passports.Footnote6 You don’t get to tell me what to be scared of […] now I’m over 50 I find I’m more set in my ways and more opinionated and I just thought ‘no, you don’t get to do that. You don’t get to tell me it’s good or it’s bad’. That’s how conflicts arise.

Changing attitudes towards the language

Across all interviews, a clear pattern emerged, with participants often seeing their engagement with Irish and their involvement in classes as a way that they could contribute to the development of social cohesion across the communities and understanding the idea of a shared heritage in the North. In their study of adult learners of Irish in Belfast, Wright and McGrory (Citation2005) found that 58% were intrinsically motivated, seeing language learning as an opportunity to reaffirm their sense of identity and culture. Such intrinsic motivation was noted in the present study also, both by those who had previously learned Irish, and wanted to return to it, and those who had not previously had the opportunity to learn it. Moreover, all saw it as a chance to try to bridge the differences of the past and to learn more about their identity.

The introduction of a language act is cited by some participants as an influence on instrumental factors of motivation. Many referred to the pragmatic gains of being an Irish speaker if an ILA is introduced, with responses echoing what was being suggested in the media and by some politicians regarding the cost implications of a language act, and the job opportunities for Irish speakers. There was a belief that Irish speakers would have an advantage in public service jobs due to an introduction of an obligation by public services to have a certain percentage of workers in each unit who are competent in Irish.

For Irish speakers there are. If the Irish Language Act goes ahead, they’re all going to get jobs! … if you look at say in Canada you can’t get a job in a public sector unless you speak French and English. Is it going to be the same situation here? If that happens, are we gonna have a positive discrimination in employment?

Overall, there was an acknowledgement that although there was so much talk about it, the public still did not know neither what an Act might involve nor how it could impact their daily lives.

Yeah so, they’re going on about this Irish language act, that’s why I feel that it’s really, uhm, you know, it’s like used as this political tool rather than actually, you know, no one actually knows what this Irish Language Act is so we don’t know. It’s quite similar to Brexit, no one really knew what Brexit was like either! [laughter] And now, you know, we have no idea!

Towards an ILA?

Mitchell and Miller (Citation2019) found that language learning, particularly Irish among the PUL community, can be a vehicle for reconciliation, offering opportunities to revise destructive understandings of history, challenge exclusivist territorialisation of group memory and to facilitate critical reflection on self, and empathy for the other. Their study, focussing on language learners at Turas, was conducted in 2015 before the ILA debate intensified due to the collapse of the Assembly. However, the authors note that ‘the prospect of an Irish Language Act to protect and promote the language has been a subject of long-running political dispute, being blocked by unionists’ (p.7). This illustrates that the notion of an ILA is indeed a long-standing issue, and one that has been on the minds of those from across the communities in Belfast who are engaging with the Irish language long before the collapse of the Assembly and subsequent political deadlock.

Although all the participants in this study are actively engaging with the Irish language, there were mixed opinions with regards to the need for an Irish language act. Among the 23 people interviewed, fourteen were in favour of an act of some form, four did not believe there was a need for an act and five were still unsure if they agreed with implementing legislation for the language. This group correlates to the Conradh na Gaeilge ‘Céard é an scéal’ survey findings in 2018 mentioned earlier, where 51% were in favour, 28% against an act and 21% were undecided on the need for an Irish Language Act.

I think all this thing with the Irish Language Act at the minute is putting people off.

Do you reckon so?

Well, it has even put me off a bit. Because well I think if you want to learn Irish it’s there, you can go and you can learn it. I don’t need an Act to tell me I can … I don’t know that we need to go that far.

I do think that talk around the Act is useful, I would just worry that the buzz, you know, at some point, would become like a barrier for people or it nearly you know stops people from wanting to eh, investigate it. Because, you know, it’s there to be investigated and how far you go is up to you.

Interview participants referred to pragmatic gains as motivation, particularly if an act is established, as well as emotional and integrative factors. However, there were also fears that at such a volatile time (Brexit etc.) the continued stalemate and role of the language in the stalemate could lead to increased tensions among communities, and further polarise the society.

It’s just pure politics and the sooner it gets out of that arena one way or another the better and I don’t think it makes a difference which way. People are hanging their hats on an Irish Language Act but it seems to me that’s more about eh, a symbol of respect than I understand what’s in the Irish Language and why this can improve things. And I’m not saying that there shouldn’t be more respect and we shouldn’t have that, it’s not for me to comment, they’re my own personal views, but I’m not sure an Irish Language Act is going to encourage anyone else to learn the language.

Conclusion

The interviews conducted in this study demonstrate the important role played by the media in disseminating not only information about proposed legislation for the Irish language in Northern Ireland, and what that may or may not mean for people, but also the role in raising awareness of the accessibility to Irish across Belfast and in all communities, therefore facilitating more people to get involved in learning the language.

For initial engagement with the language, the main motivating factors are intrinsic, as participants wish to learn Irish to reaffirm their sense of identity and culture. Learners engage with the language also out of curiosity; due to the increased attention in the media and in public discourse, many decided to attend classes to gain a deeper understanding of both the language and the issues being attributed to it.

Some of those learning Irish are affected by the policy delay as they remain conscious of the sensitivities and traditional ideologies associated with the language, and therefore remain reluctant to publicly engage with Irish or to tell family and friends that they are learning Irish because of this perceived tension. However, the political, media and public discourse that surrounds the language in the past number of years has led to a heightened awareness of the accessibility to the language across the city. Some participants reported to feeling encouraged to engage at some level with the language due to their curiosity spurred by this attention, and so wanted to learn more about the language and understand it more themselves in order to form their own opinion. For others, the increased frustration with the sustained divisions and use of the language as a political tool emboldened them to engage with Irish in order to change perceptions of who an Irish speaker is, and to be an example for their children and future generations so that they could see Irish as an element of the shared heritage in Northern Ireland, with the aspiration of leading to a more socially cohesive society.

It is salient that although questions around the role and status of Irish remains a somewhat contentious debate and often a divisive issue, the media attention and discussion around legislating for the Irish language and introducing a language act in the North has resulted in a more widespread and diverse community of language learners in Belfast.

Acknowledgements

This research, part of the Multilingualism: Empowering Individuals, Transforming Societies research project, was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) (grant number AH/N004671/1) under its Open World Research Initiative. The author is grateful the AHRC for its support. She is also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Deirdre A. Dunlevy

Deirdre A. Dunlevy is a research fellow on the AHRC-funded project ‘Multilingualism: Empowering Individuals, Transforming Societies' at Queen’s University Belfast. Her research interests focus on Linguistic Landscapes, language and identity and language policy in minoritised language settings, particularly in Spain and Ireland.

Notes

1 The conflict pre-dates 1968, but the civil rights marches are usually cited as the beginning of the period. For more on The Troubles, see Coogan Citation1996; Hennessey (Citation1997); English (Citation2006); McKitterick and McVea (Citation2012); Wichert (Citation1999).

2 Data based on all residents over the age of three self-reporting on knowledge of Irish and/or Ulster Scots. Total population at time of census 1.735 million.

3 All names used for participants are pseudonyms to ensure their confidentiality.

4 An Cultúrlann McAdam Ó Fiaich, known locally as an Cultúrlann, is an Irish language, arts and cultural centre on the Falls Road in Belfast.

5 The 12th of July is an Ulster Protestant celebration, marking the victory of the Protestant King William of Orange over the Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. The day is marked across Ulster with parades and bonfires and many towns and villages in Northern Ireland are adorned with British flags and bunting.

6 Chris spoke earlier in the interview about having acquired an Irish passport recently, motivated initially by his concerns about Brexit. Citizens of Northern Ireland are entitled to hold either, or both, an Irish and a British passport, as per their own decision.

References

- Agar, Michael. 1995. Language Shock: Understanding the Culture of Conversation. New York: William Morrow.

- Conradh na Gaeilge. 2016. Céard é an Scéal? Public Opinions on the Irish Language. Accessed 12/03/2019. https://cnag.ie/en/news/761-céard-é-an-scéal-independent-research-commissioned-by-conradh-na-gaeilge-tells-positive-story-of-majority-supporting-irish-language.html.

- Conradh na Gaeilge. 2017. Irish Language Act: Discussion Document, Version 1.0. Accessed 12/03/2019. https://cnag.ie/en/get-involved/current-campaigns/irish-language-act.html.

- Conradh na Gaeilge. 2018. Céard é an Scéal? Public Opinions on the Irish Language. Accessed 12/03/2019. https://drive.google.com/file/d/17n3PcumgcWzvJFkk0ZjyzONI_RKZpCZQ/view.

- Coogan, Tim Pat. 1996. The Troubles: Ireland’s Ordeal 1966–1995 and the Search for Peace. Boulder, CO: Roberts Rhinehart.

- Coulter, Colin, and Michael Murray. 2008. “Introduction.” In Northern Ireland after The Troubles: A Society in Transition, edited by Colin Coulter, and Michael Murray, 1–26. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Council of Europe (COE). 1992. European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Accessed 12/03/2019. https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/rms/0900001680695175.

- Crowley, Tony. 2016. “Language, Politics and Identity in Ireland: A Historical Overview.” In Sociolinguistics in Ireland, edited by Ray Hickey, 198–217. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Da Costa Cabral, Idegrada. 2018. “From Dili to Dungannon: An Ethnographic Study of Two Multilingual Migrant Families from Timor-Leste.” International Journal of Multilingualism 15 (3): 276–290.

- Darby, John. 1976. Conflict in Northern Ireland: The Development of a Polarised Community. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

- Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure (DCAL). 2015. Proposals for an Irish Language Bill (February 2015). Accessed 12/03/2019. https://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/consultations/proposals-irish-language-bill.

- The Detail. 27 January 2017. Files link Arlene Foster to Irish language row and show DUP failed to equality test Líofa cut. Accessed 29/09/2020. https://www.thedetail.tv/articles/files-link-arlene-foster-to-irish-language-row-and-show-dup-failed-to-equality-test-liofa-cut.

- Duff, Patricia. 2008. “Language Socialization, Participation and Identity: Ethnographic Approaches.” In Encyclopedia of Language and Education. Vol.3: Discourse and Education, edited by M. Martin-Jones, A.-M. de Mejia, and Nancy Hornberger, 107–119. New York: Springer.

- English, Richard. 2006. Irish Freedom: The History of Nationalism in Ireland. London: Macmillan.

- Ervine, Linda. 2019. “Linda Ervine: A Language of Healing.” In How Languages Changed my Life, edited by H. Martin, and W. Ayres-Bennett, 155–159. Archway Publishing: Bloomington.

- Flynn, Colin J., and John Harris. 2016. “Motivational Diversity among Adult Minority Language Learners: Are Current Theoretical Constructs Adequate?” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37 (4): 371–384.

- Gardner, Robert C., and Wallace E. Lambert. 1972. Attitudes and Motivation in Second-Language Learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

- Goffman, E. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Middlesex: Penguin Books.

- Hennessey, Thomas. 1997. A History of Northern Ireland, 1920–1996. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

- The Irish Times. 2017. Full Text of Martin McGuinness’s Resignation Letter. Accessed 29/09/2020. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/full-text-of-martin-mcguinness-s-resignation-letter-1.2930429.

- Mac an Bhreithiún, Bharain, and Anne Burke. 2014. “Language, Typography and Place-Making: Walking the Irish and Ulster-Scots Linguistic Landscape.” The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies 38 (1/2): 84–125.

- Mac Giolla Chríost, Diarmait. 2012. Jailtacht: The Irish Languages, Symbolic Power and Political Violence in Northern Ireland 1972–2008. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Mac Ionnrachtaigh, Feargal. 2013. Language, Resistance and Revival: Republican Prisoners and the Irish Language in the North of Ireland. London: Pluto Press.

- Mac Póilín, Aodhán. 1997. The Irish Language in Northern Ireland. Belfast: Ultach Trust.

- Maguire, Gabrielle. 1991. Our Own Language, An Irish Initiative. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Malcolm, Ian. 2009. Towards Inclusion: Protestants and the Irish Language. Belfast: Blackstaff Press.

- Mallie, Eamonn. 20 February 2018. Full ‘Draft Agreement Text. Accessed 8/10/2020. https://eamonnmallie.com/2018/02/full-draft-agreement-text/.

- McKitterick, David, and David McVea. 2012. Making Sense of the Troubles. Belfast: Viking.

- Mercator Education. 2004. Irish: The Irish Language in Education in Northern Ireland. 2nd ed. Accessed 8/10/2020. https://www.mercator-research.eu/fileadmin/mercator/documents/regional_dossiers/irish_in_northernireland_2nd.pdf.

- Mitchell, David, and Megan Miller. 2019. “Reconciliation Through Language Learning? A Case Study of the Turas Irish Language Project in East Belfast.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (2): 235–253. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1414278.

- Mulholland, Marc. 2002. Northern Ireland: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ní Chuilín, Carál. 21 February 2017. Sinn Féin Committed to Securing Irish Language Act. Accessed 29/09/2020. https://www.sinnfein.ie/contents/43585.

- Nig Uidhir, Gabrielle. 2006. “The Shaw’s Road Urban Gaeltacht: Role and Impact.” In Belfast and the Irish Language, edited by Fionntán de Brún, 136–146. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

- Northern Ireland Office. 2006. Northern Ireland (St Andrews Agreement) Act 2006. Accessed 12/03/2019. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/53/contents.

- Northern Ireland Office. 2020. New Decade, New Approach. January 2020. Accessed 8/10/2020.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/856998/2020-01-08_a_new_decade__a_new_approach.pdf.

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). 2011. Results of Census 2011. Accessed 19/11/2018. https://www.nisra.gov.uk/statistics/2011-census/results.

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). 2014. Northern Ireland Census 2011 Key Statistics Summary Report. Accessed 12/03/2019. http://www.nisra.gov.uk/archive/census/2011/results/key-statistics/summary-report.pdf.

- Ó Baoill, Dónall. 2007. “Origins of Irish-Medium Education: The Dynamic Core of Language Revitalisation in Northern Ireland.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 10 (4): 410–427.

- Ó Mainnín, Mícheál. forthcoming. “Empowering Multilingualism? Provisions for Place-Names in Northern Ireland and the Political and Legislative Context.” In Multilingualism in the Public Space: Empowering and Transforming Communities, edited by Robert Blackwood, and Deirdre Dunlevy. London: Bloomsbury.

- Pobal. 2012. Acht na Gaeilge do TÉ. The Irish Language Act NI. Second Issue 2012. [First issue 2006]. Accessed 12/03/2019. http://pobal.org/uploads/images/Acht%20na%20Gaeilge%202012.pdf.

- Pritchard, Rosalind M.O. 2004. “Protestants and the Irish Language: Historical Heritage and Current Attitudes in Northern Ireland.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 25 (1): 62–82. doi:10.1080/01434630408666520.

- Wells, Naomi, Charles Forsdick, Jessica Bradley, Charles Burdett, Jennifer Burns, Marion Demossier, Margaret Hills de Zárate, et al. 2019. “Ethnography and Modern Languages.” Modern Languages Open 1 (1): 1–16.

- Wichert, Sabine. 1999. Northern Ireland Since 1945. 2nd ed. London: Longman.

- Wright, Margaret, and Orla McGrory. 2005. “Motivation and the Adult Irish Language Learner.” Educational Research 47 (2): 191–204.