ABSTRACT

This paper describes the process of developing classroom culture that promotes reciprocal intercultural encountering in the primary school. Storycrafting, an oral storytelling method used for democratic encounters between participants, was used to connect classes in Scotland, Finland and Belgium over three cycles of design-based research. Abductive analysis produced a theoretical framework of seven key dimensions that influence the learning space for reciprocal encounters: power, knowledge, relatedness, purpose, structure, continuity and meaningfulness. These dimensions were used to identify four kinds of learning spaces that occurred during the implementation of the story exchange: the ambivalent space, the space of information, the transitional space and the space of reciprocal encountering. The intervention created a platform for children’s encounters that reinforced mutuality and reciprocal interactions rather than Othering the exchange partners.

Introduction

Classroom culture influences how children engage in intercultural encountering and whether they encounter with reciprocity and openness. This article describes insights from empirical work that will help primary school teachers and researchers to understand how classroom culture can be developed together with students so that it supports encountering. We analyse empirical data from an intercultural exchange of stories, and develop theory about what constitutes a learning space of reciprocal encountering.

Classroom culture consists of a shared understanding of social norms and knowledge repertoires between the members of a classroom community, including the teacher(s) and the students (Kumpulainen and Renshaw Citation2007; Marton and Tsui Citation2004). It evolves over time as the community creates new shared experiences that replace previous ways of doing, thinking and knowing. Therefore, we understand classroom culture as a continuum of learning spaces, which are situations where the conditions allow a particular kind of learning to occur (Dewey Citation1938/Citation2015; Marton and Tsui Citation2004).

We define intercultural learning as educative growth towards understanding, encountering and conflict resolution between individuals from two or more distinct communities (adapted from Dewey Citation1938/Citation2015; Kaikkonen Citation2004). One area of intercultural learning is reciprocal intercultural encountering, which means mutual, dialogic interaction between people from distinct communities. The communities can be national communities, but they could equally be communities based on locality, organisation, language, religion, interest, or any other commonality shared by group members. In this paper, when we say ‘encountering’, ‘intercultural encountering’ or ‘reciprocal encountering’, we are referring to reciprocal intercultural encountering.

The aim of this study is to identify how classroom culture can be developed so that it supports reciprocal intercultural encountering. Empirical data will be analysed to answer the following research questions:

What are the qualities of a space of reciprocal encountering?

How did teachers and students co-create a learning space of reciprocal encountering during an intercultural story exchange?

What other kinds of learning spaces were co-created by teachers and students during the development of an intercultural story exchange?

Reciprocal intercultural encountering is necessary for peaceful cooperation between local as well as global communities. Intercultural learning is incorporated into recommendations of intergovernmental organisations such as UNESCO (Citation2013, Citation2014), the OECD (Citation2018), and the Council of Europe (Citation2001, Citation2016, Citation2018), as well as into the national curricula of countries such as Finland and Scotland, and international curricula such as the International Baccalaureate. However, despite the prolific occurrence of the concept in educational policies and curricula, more work is needed to develop curricula and teaching practices that promote viewing cultural Others as neighbours and engage students in joint, transformative processes (McCandless et al. Citation2020). We need to better understand the challenges that schools and teachers face in implementing these types of practices, so that educational structures and school cultures can be developed to support intercultural learning.

There is evidence that international exchange projects which highlight cultural differences can unintentionally reinforce stereotypes and lead to a static view of culture (Gorski Citation2008; Lau Citation2015; MacKenzie, Enslin, and Hedge Citation2016; Royds Citation2015). To achieve the goal of reciprocal encountering, a story exchange project was developed through design-based research, where the focus shifted away from culture as a static entity to viewing culture dynamically as a process (Piipponen and Karlsson Citation2019). Three iterations took place so that the design and theory could be developed over time (Anderson and Shattuck Citation2012). The qualitative data were produced through narrative and ethnographic methods, to allow us to investigate the contextual nature of the learning spaces in detail. During the project, the children exchanged stories that were told using the Storycrafting method, where children freely tell oral stories to an interested scribe (Karlsson Citation2013). Through telling and listening to each other’s stories, the children learned how to connect to their exchange partners experientially. Although the groups never met face to face, they could imagine each other through the stories (Piipponen and Karlsson Citation2021).

Method

Contrary to the usual convention, the research methods are discussed prior to the theoretical framework because the framework was produced following the data analysis. The methodology adheres to the principles of design-based research, which involves a cyclical process of alternately developing practice and theory (Anderson and Shattuck Citation2012).

Research context and participants

Three cycles of a story exchange project were organised between partner classes in primary schools. The first author conducted the first cycle of data production in School A in Scotland in spring 2015, where she was teaching full-time as Teacher 1. Her class exchanged stories with two partner classes in Finland (from Schools B and C), which were selected due to the teachers’ expertise in the Storycrafting method and willingness to participate.

During the second cycle in spring 2016 and the third cycle in the academic year 2016–2017, the first author continued the classroom-based research while working in an international school in Belgium (School D). There the fifth grade teachers (1, 4 and 5) decided to co-teach the three classes together, with the first author coordinating the project. One of the partner class teachers in Finland (Teacher 2) and her next class continued in the exchange project for the second and third cycles. The research participants are described in . All the participants were selected based on convenience.

Table 1. Description of schools and participants for each research cycle.

Ethics

This research has followed the ethical recommendations established by the Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity (Citation2009, Citation2012), which were in force at the time of the data production. This includes acquiring informed consent from the relevant municipalities, head teachers, children, parents of participating children, and the participating teachers. The research process was integrated into the daily school routines and caused minimal additional exertion to the teachers and children. The design, data production, analysis of data and reporting of the research has been conducted by paying special attention to the child perspective to ensure the child participants are valued and treated with dignity. All names have been replaced with pseudonyms.

Data production

In the first cycle of research, Class A exchanged stories with Classes B and C. The children told oral stories using the Storycrafting method, where an attentive scribe writes down the teller’s oral story exactly as it is told (Karlsson Citation2013). Once a story is finished, the scribe reads it aloud and the teller can make changes or corrections (Karlsson Citation2013). Sometimes the whole class told a story by taking turns to tell and the teacher scribed. At other times, the children worked in pairs or small groups, where the children scribed for each other. Occasionally the teachers scribed for an individual student or a small group. The project developed organically to fit into the everyday life of the classrooms.

The stories were translated into Finnish or English by the first author and sent to the partner class via email. Sometimes more than one story was sent at a time. They were read out in the school language of the partner class, then in the original language. To provide the children with an opportunity to respond to each story sent by the partner class, the first author arranged open-ended class discussions, which were audio-recorded in School A. In School B, the class teacher recorded individual students’ comments, and in School C, no commentary was produced. The partner classes continued the exchange in this manner for 7 weeks. The first author kept a researcher diary to record contextual information about the sessions. To further triangulate the data, consent was also granted to collect the email correspondence between the first author (Teacher 1) and Teacher 2.

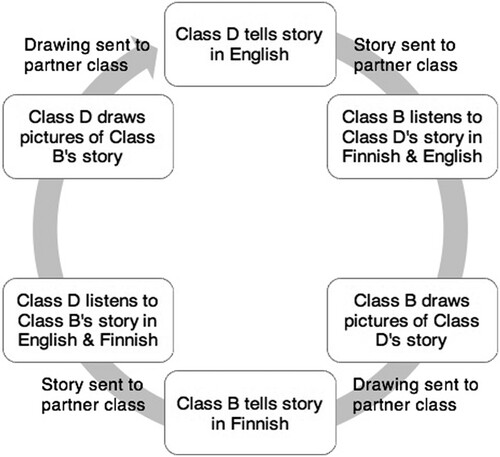

After the first cycle, the design of the story exchange was reviewed by the first and second authors and by getting written feedback from Teachers 2 and 3. For the second and third cycles in Schools B and D, the class discussions and children’s recorded comments were discontinued and replaced with a drawing activity, where the children were told to draw a picture about the story they had just heard (see ). These drawings were photographed or scanned and sent back to the partner class along with a new story. At the end of the third cycle of research, upon hearing that the exchange was coming to an end, the children in the teacher-researcher’s class of School D sent a thank you letter and class photo to the partner class. This was reciprocated by the class in School B. Teacher 5 in School D was also interviewed following a semi-structured interview schedule after two years of participating in the project. The data produced are further described in .

Figure 1. Classes from Schools B and D exchanged stories and drawings in the second and third cycles of research. The stories were translated by Teacher 1.

Table 2. Data produced over three cycles of research between 2015 and 2017.

Analysis method

The analysis process has been developed from the frameworks of design-based research and abductive analysis. Design-based research not only develops new practices, but also generates new theory over several iterative cycles of research: during a cycle, initial theoretical ideas are tested by designing an intervention in the classroom, and the theory is revised based on empirical findings (Anderson and Shattuck Citation2012). According to Timmermans and Tavory (Citation2012), abductive analysis is a suitable approach when the researcher has a sufficiently broad knowledge of theories that can be used to produce new theory, where existing theories are unable to explain an observation. Abduction involves going back-and-forth between the theory and data to refine the theory and close the gap between the theory and empirical evidence (Timmermans and Tavory Citation2012).

Initially, a general coding framework was created, which was based on a breadth of theoretical literature on how teachers create conditions for student engagement (e.g. Daniels Citation2016, Citation2017; Dewey Citation1916/Citation1997, Citation1938/Citation2015; George and Richardson Citation2019; Kelly et al. Citation2014; Kumpulainen and Renshaw Citation2007; Marton and Tsui Citation2004; Mercer and Littleton Citation2007; Reeve Citation2013; Ryan and Deci Citation2000, Citation2017; Turner et al. Citation2014). The data were organised into primary as well as secondary data (see ), which were cross-referenced with the primary data to identify more latent content (Graneheim, Lindgren, and Lundman Citation2017). Atlas.ti software was used to code the data extracts into general categories, including student engagement, student initiatives, teaching practices, educational structures, meaningfulness, relationality, pedagogical discourses. Then sub-codes were created to specify how each general category was constituted in the data: for example, student engagement included sub-codes such as ‘listening attentively’ and ‘agreeing with someone’.

The first author was responsible for the bulk of the data analysis. As the teacher-researcher, she had specific contextual knowledge about the situations that took place during the data collection, which allowed her to identify latent content in the data. To triangulate the analysis process and supply further interpretive perspectives, the second and third authors reviewed a representative cross-section of the first cycle of data using the coding framework provided by the first author. Based on the discussion, code categories were revised and added to so that they formed a coherent system. This system was used to review and recode all three cycles of data. Where necessary, some new codes were introduced at this stage as well.

The goal of the second phase of analysis was to identify patterns and relationships in the coded data that explained how the teachers created conditions for student engagement. These were dubbed pedagogies and first organised as a table by describing how each of the coded categories (e.g. educational structures, teacher beliefs, teacher practices, student beliefs, student engagement) manifested themselves in the data patterns. The table of pedagogies and the related data extracts were used to write up a description of the following pedagogies: ambivalent approach, pedagogy of information, and pedagogy of reciprocal encountering. At this stage, all three authors came together to review the table and descriptions. The discussion concluded that the code categories used in the analysis used were not fully capturing the dynamic nature of the classroom interactions that produced the learning space, where both teacher and students had agency.

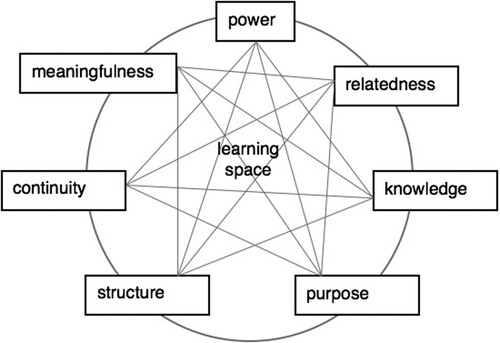

In the final phase, the first author returned to the descriptions and the related coded extracts, and recategorised them into seven dynamic, process-based dimensions (see ) that influenced how the students and teachers together co-created a learning space. For example, the codes under teacher and student beliefs were restructured under the dimensions of knowledge and purpose. Furthermore, codes related to power were collated under one dimension, as they had been scattered across various code categories. This illustrates how one code could be included under two or more dimensions, as the dimensions interacted in the learning space. Further theoretical reading on the dimensions took place at this point (e.g. Aro, Citation2012; Foucault Citation1977/Citation1995; Freire Citation1970/Citation1996; Hännikäinen and Rasku-Puttonen Citation2010; Kaikkonen Citation2004; Lanas Citation2017; Layne, Trémion, and Dervin Citation2015; Tornberg Citation2013). Their theoretical strength was tested by returning to the data to reanalyse the coded patterns, which were renamed learning spaces, and by revising the findings table and the written descriptions. The transitional space was identified at this stage. All three authors met again to evaluate how well the proposed theoretical framework fit with the empirical data, and further adapted it into the context of intercultural encountering in the classroom. In this way, the abductive analysis process produced both a suitable theoretical framework and a related set of findings to answer the research questions.

Theory

A theoretical model was created in an abductive analysis process (see previous section). It describes the formation of a classroom culture over time and learning spaces in the moment, showing how power, knowledge, relatedness, purpose, structure, continuity and meaningfulness influence the teachers’ and students’ co-creation process.

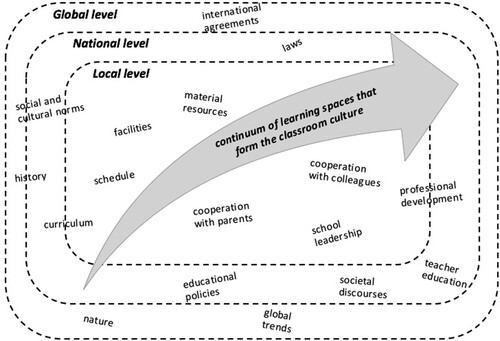

Continuity of classroom culture: bounded by extrinsic conditions

Classroom culture changes over time as new experiences in each learning space lead to new shared understandings and norms within the class community (adapted from Dewey Citation1938/Citation2015). A learning space is a single situation, whereas classroom culture exists as a continuum of situations (see ). Extrinsic conditions, such as school culture, national legislation or global trends, create boundaries for a classroom culture’s development (Dewey Citation1938/Citation2015). These extrinsic conditions play a part in explaining why teachers can find it challenging to create spaces of reciprocal encountering with their students.

Figure 2. Development of classroom culture over time as a continuum of learning spaces, influenced by extrinsic conditions on global, national and local levels.

Many societal, cultural and institutional forces affect the day-to-day life of the classroom. Laws establish a teacher’s and students’ basic rights and responsibilities within an education system, national and regional curricula influence the content of learning, and initial teacher education and continuing professional development opportunities set the bar for teachers’ pedagogical abilities. The physical school environment and the available material resources can support or hinder particular types of learning, as can scheduling and time constraints (Connors Citation2016; Daniels Citation2016). School leaders, teacher colleagues and parents may also have certain expectations that guide how teachers and students enact teaching and learning in the classroom (Connors Citation2016; Daniels and Pirayoff Citation2015). Although this article focuses on life inside the classroom, the impact of extrinsic conditions on intercultural learning should not be underestimated. They contribute to the dimensions of power, knowledge, relatedness, purpose, structure, continuity and meaningfulness, which in turn create the learning space.

Learning spaces: promoting intercultural encountering

A learning space is a situation which enables a particular type of learning to occur (Marton and Tsui Citation2004), involving the social, cultural and physical environment. Teachers and students are considered active agents in its co-creation. This understanding is derived from an amalgamation of theoretical perspectives, including Dewey’s (Citation1938/Citation2015) concept of a situation, Vygotsky’s (Citation1986) zone of proximal development and Marton and Tsui's (Citation2004) space of learning, as well as drawing from self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci Citation2017, Citation2000). Following abductive data analysis (Timmermans and Tavory Citation2012), we have formed a theoretical framework that describes a learning space through seven key dimensions: power, relatedness, knowledge, purpose, structure, continuity and meaningfulness. They can be used as analytical tools to explain why a learning space unfolds the way it does. illustrates how the dimensions not only influence the learning space, but also interact with each other. For example, if power is distributed democratically in a classroom, it will likely have an influence on how the class members relate to one another and how the learning space is structured, and vice versa.

Figure 3. Dimensions of power, relatedness, knowledge, purpose, structure, continuity, and meaningfulness interact with each other to form a learning space.

The next section will describe how each theoretical dimension contributes to creating a learning space that promotes intercultural encountering in the primary school classroom.

Power

Power in a learning space can range from authoritative to democratic, and this influences whether reciprocal encountering can take place. Authoritative power, derived from the educational institution, enables teachers to control who speaks and what can be said (Aro, Citation2012; Foucault Citation1977/Citation1995; Mercer and Littleton Citation2007). In contrast, power is distributed more democratically when children are seen as agentic (Karlsson Citation2020) and can shape encounters by drawing from their own cultural repertoires (Gutiérrez and Rogoff Citation2003; Piipponen and Karlsson Citation2021). A democratic learning space enables children to voice their thoughts and take action in transformative ways (Freire Citation1970/Citation1996). In practice, teachers distribute power by supporting students’ autonomy (Ryan and Deci Citation2017; Turner et al. Citation2014) and social participation (Karlsson Citation2020), and students use agentic engagement to proactively influence the teacher and their learning environment (Reeve Citation2013).

Knowledge

The way knowledge is conceived in broader educational structures and discourses affects what kinds of knowledge are privileged in schools (e.g. Gorski Citation2009; Portera Citation2008; Tornberg Citation2013). Knowledge is defined on a continuum as dynamic, experiential and situated at one end and static, cognitive and universal at the other (Dewey Citation1938/Citation2015). Understanding culture as a static, unchanging entity will likely lead to designing learning experiences that focus on concrete aspects, such as dress, food and festivals, which tend to reinforce cultural stereotypes and essentialism (Alvaré Citation2017; Piller Citation2017). However, if culture is understood as dynamic, layered and actively created by its members, there is more room for a nuanced understanding to develop (Dervin Citation2011; Layne, Trémion, and Dervin Citation2015; Piipponen and Karlsson Citation2019; Piller Citation2017).

Relatedness

Relatedness is a basic need, which means ‘feeling connected and involved with others’ (Ryan and Deci Citation2017, 87). The lack of relatedness produces fear, suspicion and a relational hierarchy. Intercultural encounters are characterised by feeling connected to one’s own community as well as finding a way to relate to the other (Jaatinen Citation2015). A warm, inclusive classroom culture is thus necessary for students to feel heard when engaging in intercultural encountering (Karlsson Citation2020; Lanas Citation2017). Teachers promote relatedness in practice by modelling and encouraging mutual respect and by creating conditions for students to collaborate productively (Turner et al. Citation2014).

Purpose

The purpose of intercultural education historically began as developing sojourners’ (e.g. diplomats, business and military personnel) communicative competence in preparation for going abroad (Piller Citation2017), but alongside this instrumental view has developed the more holistic purpose of understanding and acting in a diverse society (Abdallah-Pretceille Citation2006; Layne, Trémion, and Dervin Citation2015). Viewing intercultural learning as simply an instrumental tool that ‘helps us to get along’ ignores the complex sociohistorical contexts that have an impact on intercultural encounters, so we argue that learning should not be limited to decontextualised skills and knowledge, but aim for holistic growth of the learners (Dewey Citation1938/Citation2015; Lanas Citation2017; McCandless et al. Citation2020; Tornberg Citation2013).

Structure

Structure refers to supports and opportunities in a learning space that enable learning to take place (George and Richardson Citation2019). Language is a key tool for structuring learning (Kumpulainen and Renshaw Citation2007; Marton and Tsui Citation2004; Mercer and Littleton Citation2007). Language is not a neutral communication device; instead, it focuses attention on certain perspectives and transmits certain ideological discourses (Freire Citation1970/Citation1996). A structure that supports reciprocal encountering enables students to personally experience encountering someone from another culture, with learning taking place if the students engage dialogically with each other (Kaikkonen Citation2004). More commonly, intercultural learning is structured for students to learn facts about another culture, perhaps because imparting knowledge through class discussions is so habitual to teachers (Howe and Abedin Citation2013; Kaikkonen Citation2004). However, learning information is different to engaging in reciprocal encountering, because it imparts a static, objectifying understanding of cultural Others (McCandless et al. Citation2020).

Continuity

Dewey (Citation1938/Citation2015, 35) describes the connectedness of situations in different points in time as ‘continuity of experience’, because our experiences flow into one another as we interpret new situations through the tinted glasses of memory, prior knowledge and future expectations. Thus, students’ and teachers’ previous experiences of similar situations define how they frame a new learning situation (Dewey Citation1938/Citation2015; Marton and Tsui Citation2004). Children’s personal experiences and familiarity with different languages and cultures promote openness to encountering in the future (Ben Maad Citation2016). Not all children have opportunities to experience cultural diversity in their own environment; therefore, intercultural learning should be integrated into school curricula and everyday practices, so that students have repeated opportunities over time to develop their abilities (Ragnarsdóttir and Blöndal Citation2015). Encountering others with reciprocity cannot be learned during a one-off lesson, but develops gradually as children’s experiences of encountering accumulate.

Meaningfulness

Meaningfulness explains the value of or interest towards a task, and supports intrinsic motivation (Turner et al. Citation2014). Learning is experienced as meaningful when it authentically connects to children’s lives. It is particularly important to make intercultural encounters feel meaningful for children – encountering is a deeply personal endeavour, because it involves experiencing the other side as well as opening up the self (Buber Citation1947/Citation2002). Participatory practices are a way for teachers to learn what children think, how they learn and what is meaningful to them (Hännikäinen and Rasku-Puttonen Citation2010). This involves developing the classroom culture so that it values and supports children’s contributions and initiatives (Karlsson Citation2020).

Findings

Four types of learning spaces were identified over the course of the three cycles of design-based research: an ambivalent space, a space of information, a transitional space and a space of reciprocal encountering. The spaces followed a rough progression so that cases of the ambivalent space were most common during the first cycle of research and the space of reciprocal encountering was most common during the last cycle. With growing experience, the teachers were able to guide the learning spaces more effectively towards reciprocal encountering. However, if the key dimensions of power, relatedness, knowledge, purpose, structure, continuity or meaningfulness were not well aligned for encountering, sometimes classes reverted to one of the other three spaces.

Ambivalent space

An ambivalent space was formed particularly when the exchange was new to both the teacher and children, so that power, knowledge, purpose and structure fluctuated. The ambivalent space featured most prominently in the beginning of the first research cycle during class discussions in School A. The following extract took place after the teacher-researcher read aloud a story from a partner class.

Any reactions, what would you like to say about the story? Jimmy?

That was a very, very unbelievably short story.

It was very short. What was it about?

(Child without research consent makes a comment)

It was very short, so you’re all in agreement. It’s about?

CCTVFootnote1!

About CCTV. What d’you think about CCTV? Was it a school?

It’s very useful.

But they didn’t really explain much, they just says there’s a CCTV camera that’s seen good and bad things: boys playing rough and the girls screaming in the corridor. That’s all!

Would that happen in (name of school), d’you think?

Critiquing the story did not support reciprocally encountering the exchange partners, because the children’s responses were actually intended for their teacher. They demonstrated that they have the right knowledge that the teacher typically assesses for in the context of language arts (Aro, Citation2012). It was unproductive to document the children’s responses to the partner’s stories through a class discussion, because talking about experiences is a meaningful method for an (adult) teacher, but it does not account for the breadth of ways in which children express their experiences.

Space of information

Like the ambivalent space, the space of information typically occurred during the class discussions in the first cycle of research in School A. The space was created when the children grew curious of their exchange partners after hearing a story in Finnish. The questions they asked ranged from language, clothes, make-up, sweets and sports to school, currency, wildlife and uniquely Finnish words, drawing from the children’s interests and cultural repertoires. In other words, they connected the questions to their personal experiences and knowledge, which made the discussion meaningful.

However, by answering the children’s questions, the teacher-researcher positioned herself as a knowledgeable expert and thus implicitly communicated to the children that the purpose of the lesson was to increase their knowledge about Finland. The discussion became a question-and-answer session where the students were positioned as apprentices learning from the expert teacher. This structure did not support encountering between the exchange partners, but rather objectified, even essentialised them. The question-and-answer sessions upheld a static conception of culture, as the teacher-researcher described in the researcher diary:

Overall, the questions were very concrete, based on superficial observations. What they [the students] got out of the conversation was a list of facts, rather than a deep understanding. (Researcher diary, 18/10/2015)

Transitional space

The transitional space occurred usually at the beginning of each research cycle. The children wanted to test the limits of the new space: how far is it possible to go in telling about taboo topics before someone objects? Is the power to tell really with the storyteller? Rebellious or taboo content appeared in the very first story of a class in School D in the second cycle of research. A child began the story with the taboo of death: ‘Once there was a guy named Bob and he died’. Several children then during their turns proceeded to challenge the classroom norms of appropriateness by mentioning drunkenness, excrement, vomiting, infidelity and killing. Similar taboo topics emerged in a few stories in each participating class, but the example above was the most poignant for incorporating so many different taboos in one tale. The teachers did not comment or flinch at these, but simply wrote down each story as it was told. In traditional school culture, taboo topics are typically reprimanded, but the teachers and children were able to negotiate an exception to this rule, as Teacher 2 explains:

One child said that poop stories are not allowed in school because there is an agreement not to tell stories with poop or guns, but now this story [from School D] DID mention poop. I said that when Storycrafting, you can say whatever comes to mind, that’s the rule of Storycrafting. So this time we must deviate from that school rule. After that [the child] happily drew a picture of the bird that POOPED on Bob. (Teacher email, 7/4/2016)

Many of the children want to have a turn, but get bored listening to others and start chatting with the people close to them. On the other hand, often they are so involved in the story that they shout out suggestions even when it is not their turn. (Researcher diary, 29/3/2015)

Space of reciprocal encountering

The space of reciprocal encountering is created when children can playfully encounter each other through the partner’s stories and drawings. The teacher assists in structuring the space so that it is democratic and inclusive, but resists being the recipient of the children’s creations. She accepts the stories and drawings without attempting to correct or evaluate them. The authorship and power over the stories and drawings rests with the children, so the breadth of children’s knowledge becomes visible and valued. Over time, the exchange partner classes can create a shared narrative culture (Piipponen and Karlsson Citation2021).

The children felt warmth and interest towards their exchange partners, as illustrated in the following teacher email:

One of the children said that we should definitely travel to Belgium to see the storytellers. And that you should travel to Finland to visit our class. But in our school, grade 3 doesn’t yet go on long trips. The tradition is that in grade 6 we could go, if the parents have collected money. (Teacher email, 1/4/2016)

In the second and third cycles of research at School D, the teacher-researcher (Teacher 1) supported relatedness and a democratic power structure in the class community more explicitly than in the first cycle. After she taught the Storycrafting method to the children, she asked them for suggestions on how to equally include everyone in the activity. The students’ suggestions were discussed, and through a whole-class negotiation, some ground rules were agreed.

We agreed on some key rules: (…) The teacher chooses the person who starts. Each storyteller then chooses someone to follow. The children decided it should be boy–girl-boy–girl, so that boys and girls have an equal chance of being chosen. (Researcher diary, 31/1/2016)

The teacher’s role was significant in introducing the expectations of the story exchange, but with time the children became more autonomous and introduced new initiatives in the second and third cycles of research. After becoming familiar with the Storycrafting method, the children often worked in small groups and scribed each other’s stories. Many children in School D had enjoyed telling the class stories together, so they invented an alternating scribe role to allow each group member to tell a part of the story. Furthermore, often groups requested if they could read their finished story out to the entire class before sending it to their partners in Finland. The suggestion to write a thank you letter also came from the children. The children really enjoyed the sense of togetherness that permeated the exchange project, and so their initiatives further supported reciprocity and mutual respect within and between the class communities. The same is true of School B in Finland. Teacher 2 explained that Storycrafting became particularly important for children on the verges of the class community:

In our class, a couple of artistic students withdraw from the so-called inside group of students. Additionally, a few are otherwise just left on the outside. It is these students who love telling and drawing during Storycrafting. Everyone was curious to hear and see your creations. (Teacher email, 7/6/2017)

Table 3. Learning spaces co-created by teachers and students during an intercultural story exchange.

Discussion

This study has found that reciprocal intercultural encountering in the primary school classroom happens best when the classroom culture supports a democratic, experiential and inclusive approach, where learning is understood as holistic, exploratory, contextualised and cumulative. In the beginning, the learning spaces of the story exchange were often ambivalent or transitional, or focused on learning information rather than encountering. As the children’s – and especially the teachers’ – experiences of the exchange grew, the classroom culture shifted so that reciprocal encountering could be achieved. The theoretic framework developed in this study provides an analytic tool for teachers to use when designing spaces for reciprocal encountering.

Developing the story exchange produced important insights for the teachers. It turned out that shifting the focus from the product of learning (the stories) to the process of learning (engaging in a space for reciprocal encountering) required resisting some of the norms of traditional school culture, where the teacher controls discourses. Changing existing cultural practices may also require the teacher to engage in critical, reflexive action, as the teacher may be unintentionally upholding the very structures she is attempting to change (Bash Citation2014). In this study, the dual role of the teacher-researcher supported the transformation of practice, but also led to a professional transformation. Insights from theory and empirical work motivate the teacher-researcher to involve the students more actively in the co-creation of learning spaces (Niemi Citation2019). For example, not judging or evaluating the content of the student’s stories was transformative action, because it shifted the purpose of the learning space from performative to relational.

The findings lead to important implications for teacher educators, policy-makers and administrators: if we are to fully embrace intercultural education, educational structures should encourage and enable teachers to develop a warm, participatory, democratic classroom culture (Hännikäinen and Rasku-Puttonen Citation2010; Karlsson Citation2020; Lanas Citation2017). Children should be seen as agents who participate in (re)creating classroom culture together with the teacher, and capable of transformative action (Freire Citation1970/Citation1996; McCandless et al. Citation2020). Instrumental, performative teaching practices can work for learning that is narrowly defined as knowledge-acquisition, but this style of teaching in the field of intercultural education is at best superficial and at worst counterproductive, even harmful (Gorski Citation2008; Lanas Citation2017; McCandless et al. Citation2020). Our study reconfirmed a frequent finding in the literature that good intentions do not always lead to good outcomes (Alvaré Citation2017; Gorski Citation2008; Lau Citation2015). Knowing ‘facts’ about a culture is not sufficient to help children develop empathy, reciprocal encountering skills or critical action (McCandless et al. Citation2020).

In the same vein, we would like to question authoritative assessment practices that are a tool to control students (Foucault Citation1977/Citation1995). Should intercultural encountering be assessed formally? Our findings indicate that when the teachers resisted evaluating the children’s stories and drawings and instead showed they valued the children’s contributions, the focus of the exchange shifted away from analysing the learning products towards the process of encountering. However, we acknowledge that teachers may not have control over assessment practices, especially if a school system practises recurrent, high-stakes testing. High-stakes testing, a hierarchical management structure and instrumental goals in education systems are derived from the ideology of neoliberalism; we concur with prior research that this kind of focus on school performance narrows the purpose of education and the opportunities for intercultural learning (Gorski Citation2008; Lanas Citation2017; Portera Citation2008).

This study focused on developing a space for reciprocal intercultural encountering, but intercultural learning also includes conflict resolution (Gorski Citation2009; Kaikkonen Citation2004). Once the shared narrative culture and a sense of mutuality were established with the partner class, the teachers could have further created opportunities for children to engage with conflicts, such as dealing with stereotypes, and how to discuss differing beliefs. It would be worthwhile to conduct further research on how children can start developing critical self-awareness of their own beliefs and prejudices, and whether the Storycrafting exchange method could be further developed to address critical or decolonising interculturality (Gorski Citation2008, Citation2009).

Some limitations have been identified. Given that this was a small-scale, qualitative, development research project, the theory and findings pertain to this specific research context only, and large-scale, longitudinal research is warranted to make any generalisations. Furthermore, it would be valuable to do research on the intercultural story exchange in other parts of the world, in different school systems and cultures, especially between the Global North and South, as previous research points to particular challenges in projects that cross this divide (Dervin Citation2011; Gorski Citation2008; Lau Citation2015; MacKenzie, Enslin, and Hedge Citation2016; Royds Citation2015).

The participant (auto-)ethnographic approach posed some challenges for data collection. Working simultaneously as teacher and researcher meant that sometimes observation notes were fragmented, written up after a time delay, or just missing. However, the gaps can be filled by the multiple methods of data production as well as the teacher-researcher’s intimate contextual knowledge of the research setting. The data may also be partially skewed in School A, because only 13 out of 27 students returned the consent form, whereas in the other schools, consent was received from the majority of students and their parents. Finally, the researchers’ interpretations dominate the data analysis process. In upcoming research, interviews with the students will address this shortcoming. Future research will also give consideration to children’s experiences of intercultural encountering between different micro-cultures, such as friendship, gender, interest, age or language groups.

Conclusion

Reciprocal intercultural encountering is more than simply being in contact with someone from a different cultural background; it requires deliberate effort from teachers to develop a constructive classroom culture over time, which fosters reciprocal encountering even between distant exchange partners. Although at first the children’s learning from the story exchange seemed superficial, the ambivalent spaces and spaces of information that occurred in the classroom helped the researchers to become aware of how dimensions such as power, relatedness and continuity influence learning spaces. Using the resulting theoretic framework will hopefully help other educators to develop learning spaces that promote reciprocal intercultural encountering.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere thanks to all the children, parents, teachers, and schools who have made this research possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Closed-circuit television = security camera system.

References

- Abdallah-Pretceille, M. 2006. “Interculturalism as a Paradigm for Thinking About Diversity.” Intercultural Education 17 (5): 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675980601065764.

- Alvaré, B. T. 2017. “‘Do They Think We Live in Huts?’ – Cultural Essentialism and the Challenges of Facilitating Professional Development in Cross-Cultural Settings.” Ethnography and Education 12 (1): 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2015.1109466.

- Anderson, T., and J. Shattuck. 2012. “Design-Based Research: A Decade of Progress in Education Research?” Educational Researcher 41 (1): 16–25. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X11428813.

- Aro, M. 2012. “Effects of authority: voicescapes in children's beliefs about the learning of English.” International Journal of Applied Linguistics 22 (3): 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2012.00314.x.

- Bash, L. 2014. “The Globalisation of Fear and the Construction of the Intercultural Imagination.” Intercultural Education 25 (2): 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2014.885223.

- Ben Maad, M. R. 2016. “Awakening Young Children to Foreign Languages: Openness to Diversity Highlighted. Language.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 29 (3): 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2016.1184679.

- Buber, M. 1947/2002. Between Man and Man. London: Routledge.

- Connors, M. 2016. “Creating Cultures of Learning: A Theoretical Model of Effective Early Care and Education Policy.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 36: 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.12.005.

- Council of Europe. 2001. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching and Assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Council of Europe. 2016. Competences for Democratic Culture: Living Together as Equals in Culturally Diverse Democratic Societies. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Council of Europe. 2018. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching and Assessment. Companion Volume with New Descriptors. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Daniels, E. 2016. “Logistical Factors in Teachers’ Motivation.” The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas 89 (2): 61–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2016.1165166.

- Daniels, E. 2017. “Curricular Factors in Middle School Teachers’ Motivation to Become and Remain Effective.” RMLE Online: Research in Middle Level Education 40 (5): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2017.1300854.

- Daniels, E., and R. Pirayoff. 2015. “Relationships Matter: Fostering Motivation Through Interactions.” Voices from the Middle 23 (1): 19–23.

- Dervin, F. 2011. “A Plea for Change in Research on Intercultural Discourses: A ‘Liquid’ Approach to the Study of the Acculturation of Chinese Students.” Journal of Multicultural Discourses 6 (1): 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2010.532218.

- Dewey, J. 1916/1997. Democracy and Education. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Dewey, J. 1938/2015. Experience and Education. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity. 2009. Ethical Principles of Research in the Humanities and Social and Behavioural Sciences and Proposals for Ethical Review. Helsinki: Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity.

- Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity. 2012. Responsible Conduct of Research and Procedures for Handling Allegations of Misconduct in Finland. Helsinki: Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity.

- Foucault, M. 1977/1995. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Freire, P. 1970/1996. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin Books.

- George, S. V., and P. W. Richardson. 2019. “Teachers’ Goal Orientations as Predictors of Their Self-Reported Classroom Behaviours: An Achievement Goal Theoretical Perspective.” International Journal of Educational Research 98: 345–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.09.011.

- Gorski, P. C. 2008. “Good Intentions are Not Enough: A Decolonizing Intercultural Education.” Intercultural Education 19 (6): 515–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675980802568319.

- Gorski, P. C. 2009. “What We’re Teaching Teachers: An Analysis of Multicultural Teacher Education Coursework Syllabi.” Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (2): 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.07.008.

- Graneheim, U. H., B.-M. Lindgren, and B. Lundman. 2017. “Methodological Challenges in Qualitative Content Analysis: A Discussion Paper.” Nurse Education Today 56: 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002.

- Gutiérrez, K. D., and B. Rogoff. 2003. “Cultural Ways of Learning: Individual Traits or Repertoires of Practice.” Educational Researcher 32 (5): 19–25. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032005019.

- Hännikäinen, M., and H. Rasku-Puttonen. 2010. “Promoting Children’s Participation: The Role of Teachers in Preschool and Primary School Learning Sessions.” Early Years: An International Journal of Research and Development 30 (2): 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2010.485555.

- Howe, C., and M. Abedin. 2013. “Classroom Dialogue: A Systematic Review Across Four Decades of Research.” Cambridge Journal of Education 43 (3): 325–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2013.786024.

- Jaatinen, R. E. 2015. “Promoting Interculturalism in Primary School Children Through the Development of Encountering Skills: A Case Study in Two Finnish Schools.” Education 3–13 43 (6): 731–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2013.877951.

- Kaikkonen, P. 2004. Vierauden keskellä: Vierauden, monikulttuurisuuden ja kulttuurienvälisen kasvatuksen aineksia [Amidst Foreignness: Ingredients for Educating about the Foreign, Multicultural and Intercultural]. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä University Press.

- Karlsson, L. 2013. “Storycrafting Method – to Share, Participate, Tell and Listen in Practice and Research.” European Journal of Social & Behavioural Sciences 6 (3 special issue): 1109–1117. https://doi.org/10.15405/ejsbs.88.

- Karlsson, L. 2020. “Studies of Child Perspective in Methodology and Practice with ‘Osallisuus’ as a Finnish Approach to Children’s Cultural Participation.” In Childhood Cultures in Transformation: 30 Years of the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child in Action, edited by J. S. Borgen and E. E. Ødegaard, 246–273. Leiden: Brill/Sense Publisher.

- Kelly, P., H. Dorf, N. Pratt, and U. Hohmann. 2014. “Comparing Teacher Roles in Denmark and England.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 44 (4): 566–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2013.800786.

- Kumpulainen, K., and P. Renshaw. 2007. “Cultures of Learning.” International Journal of Educational Research 46: 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2007.09.009.

- Lanas, M. 2017. “An Argument for Love in Intercultural Education for Teacher Education.” Intercultural Education 28 (6): 557–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2017.1389541.

- Lau, S. M. C. 2015. “Intercultural Education Through a Bilingual Children’s Rights Project: Reflections on its Possibilities and Challenges with Young Learners.” Intercultural Education 26 (6): 469–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2015.1109774.

- Layne, H., V. Trémion, and F. Dervin. 2015. “Introduction.” In Making the Most of Intercultural Education, edited by H. Layne, V. Trémion, and F. Dervin, 1–15. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- MacKenzie, A., P. Enslin, and N. Hedge. 2016. “Education for Global Citizenship in Scotland: Reciprocal Partnership or Politics of Benevolence?” International Journal of Educational Research 77: 128–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2016.03.007.

- Marton, F., and A. B. M. Tsui. 2004. Classroom Discourse and the Space of Learning. London: Laurence Erlbaum Associates.

- McCandless, T., B. Fox, J. Moss, and H. Chandir. 2020. “Assessing Intercultural Understanding: The Facts About Strangers.” Educational Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2020.1825336.

- Mercer, N., and K. Littleton. 2007. Dialogue and the Development of Children’s Thinking: A Sociocultural Approach. Oxon: Routledge.

- Niemi, R. 2019. “Five Approaches to Pedagogical Action Research.” Educational Action Research 27 (5): 651–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2018.1528876.

- OECD. 2018. Preparing Our Youth for an Inclusive and Sustainable World: The OECD PISA Global Competence Framework. Paris: OECD.

- Piipponen, O., and L. Karlsson. 2019. “Children Encountering Each Other Through Storytelling: Promoting Intercultural Learning in Schools.” The Journal of Educational Research 112 (5): 590–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2019.1614514.

- Piipponen, O., and L. Karlsson. 2021. “‘Our Stories Were Pretty Weird Too’ – Children as Creators of a Shared Narrative Culture in an Intercultural Story and Drawing Exchange.” International Journal of Educational Research 106: 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101720.

- Piller, I. 2017. Intercultural Communication: A Critical Introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Portera, A. 2008. “Intercultural Education in Europe: Epistemological and Semantic Aspects.” Intercultural Education 19 (6): 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675980802568277.

- Ragnarsdóttir, H., and H. Blöndal. 2015. “Multicultural and Inclusive Education in Two Icelandic Schools.” In Making the Most of Intercultural Education, edited by H. Layne, V. Trémion, and F. Dervin, 35–57. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Reeve, J. 2013. “How Students Create Motivationally Supportive Learning Environments for Themselves: The Concept of Agentic Engagement.” Journal of Educational Psychology 105 (3): 579–595. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032690.

- Royds, K. 2015. “Listening to Learn: Children’s Experiences of Participatory Video for Global Education in Australia and Timor-Leste.” Media International Australia 154 (1): 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X1515400110.

- Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2000. “Self-determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” American Psychologist 55: 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68.

- Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2017. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development and Wellness. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

- Timmermans, S., and I. Tavory. 2012. “Theory Construction in Qualitative Research: From Grounded Theory to Abductive Analysis.” Sociological Theory 30 (3): 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275112457914.

- Tornberg, U. 2013. “What Counts as “Knowledge” in Foreign Language Teaching and Learning Practices Today? Foreign Language Pedagogy as a Mirror of its Time.” Nordic Journal of Modern Language Methodology 2 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.46364/njmlm.v2i1.77.

- Turner, J. C., H. Z. Kackar-Cam, M. Trucano, and S. M. Fulmer. 2014. “Enhancing Students’ Engagement: Report of a 3-Year Intervention with Middle School Teachers.” American Educational Research Journal 51 (6): 1195–1226. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214532515.

- UNESCO. 2013. Intercultural Competences: Conceptual and Operational Framework. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2014. Global Citizenship Education: Preparing Learners for the Challenges of the Twenty-First Century. Paris: UNESCO.

- Vygotsky, L. 1986. Thought and Language. 4th ed. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.