ABSTRACT

Zambia is home to a complex set of language practices, which involve languages being used in different ways across social contexts. Historically written communication has typically been associated with English with African languages mainly associated with used spoken contexts. Recently, however, there has been a shift in this pattern with African languages being used more frequently in and across the linguistic landscape of Zambia in public writing [Banda, F., and H. Jimaima. 2017. “Linguistic Landscapes and the Sociolinguistics of Language Vitality in Multilingual Contexts of Zambia.” Multilingua 36 (5): 595–625; Simungala, G. 2020. “The Linguistic Landscape of the University of Zambia: A Social Semiotic Perspective.” Unpublished MA Thesis, University of Zambia; Simungala, G., and H. Jimaima. 2020. “Multilingual Realities of Language Contact at the University of Zambia.” Journal of African and Asian Studies, 1–14]. In this paper, we add to the growing body of work within linguistic landscape research that draws on a translanguaging perspective to understand the ways in which language is used as a resource for meaning making in the social world [Wei, Li. 2011. "Moment Analysis and Translanguaging Space: Discursive Construction of Identities by Multilingual Chinese Youth in Britain." Journal of Pragmatics 43 (5): 1222–1235; Wei, Li. 2018. “Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language.” Applied Linguistics 39 (1): 9–30; García, O., and T. Kleyn. 2016. Translanguaging with Multilingual Students: Learning from Classroom Moments. Routledge; MacSwan, J. 2017. “A Multilingual Perspective on Translanguaging.” American Educational Research Journal 54 (1): 167–201; Jaspers, J. 2018. “The Transformative Limits of Translanguaging.” Language & Communication 58: 1–10]. More specifically, we adopt the concept of translanguaging spaces [Wei, Li. 2011. "Moment Analysis and Translanguaging Space: Discursive Construction of Identities by Multilingual Chinese Youth in Britain." Journal of Pragmatics 43 (5): 1222–1235; Wei, Li. 2018. “Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language.” Applied Linguistics 39 (1): 9–30; Reilly, C. 2021. 3 Malawian Universities as Translanguaging Spaces. In English-Medium Instruction and Translanguaging, 29–42. Multilingual Matters] to explore the ways in which language is used in billboards and advertising spaces and propose that important shifts in language uses are observable. We discuss the changing status and uses of local African languages and why this is important in understanding language use in post-colonial contexts such as Zambia.

Introduction

Linguistic landscape analysis is a powerful lens through which we can come to understand the ways in which our social worlds (material or online) are constituted in and through language (for example, Landry and Bourhis Citation1997; Piller Citation2001, Citation2003; Cenoz and Gorter Citation2006; Gorter Citation2018). Work in this area has been particularly effective at highlighting the ways in which the diversity that characterises many urban centres is reflected in and through language use within and across different social settings. As Barni and Bagna (Citation2010, 5) state ‘urban spaces are, therefore, increasing in importance as “showcases” and, above all, environments where languages weave together and linguistic destinies and expectations are “played out”’. Such a perspective provides a way of ‘reading’ language practices in socially situated contexts. It provides, amongst other things, a helpful mechanism for cataloguing changes in language use and insights into the dynamic and complex ways in which language is deployed in multilingual contexts (Blommaert Citation2013).

Linguistic landscapes are comprised of public writing such as public signage, advertising billboards or product and shop names (e.g. Coupland Citation2003; Alexander Citation2009; Spolsky Citation2009) with research interested in ‘the visibility and salience of languages on public and commercial signs in a given territory or region’ (Landry and Bourhis Citation1997, 23). In this paper, we use the concept of linguistic landscapes to focus on the ways language is used on billboards and advertising spaces in the city of Ndola in Zambia’s Copperbelt province. Zambia’s third-largest city Ndola is a vibrant, multilingual urban space which provides a rich context to not only explore local language use and practices but those of Zambia more broadly. Focussing on these billboards also allows us to concentrate on the ways in which space is used to reflect, create and establish meaning and to understand how language use is embedded in material culture and the socio-economic context.

Our discussion adds to the growing body of work within linguistic landscape research that draws on a translanguaging perspective to understand the ways in which language is used as a resource for meaning making (Wei Citation2011, Citation2018; García and Kleyn Citation2016; MacSwan Citation2017; Jaspers Citation2018). Translanguaging starts from the view that rather than seeing languages as bounded entities they ‘ought to be conceived as semiotic materialities whose resources can be drawn upon by social actors’ (Simungala and Jimaima Citation2021, 12). Adopting translanguaging as a conceptual tool allows us to explore how language is used fluidly, dynamically and locally to make meaning. More specifically in this paper, we adopt the concept of translanguaging spaces (Wei Citation2011, Citation2018; Reilly Citation2021) to explore the ways in which language is used in billboards and what this tells us about day-to-day language practices in Ndola. Conceptualising billboards as a translanguaging space means understanding how the space ‘allows language users to integrate social spaces (and thus ‘linguistic codes’) that have been formerly separated through different practices in different places’ (Wei Citation2018, 23).

As we show, these billboards are important translanguaging spaces within which we can observe the change in the way that language is being used and argue that this is an indication of a shift in the status of Zambian languages in the public sphere. Such an analysis is important in terms understanding current practices in the context of Zambia as well as offering novel understandings of language use in post-colonial contexts more broadly. In the paper, we make use of billboards that have been erected in and around the city but particularly in common advertising spots on roadsides. Following Reilly (Citation2021, 35) we make use of ‘translanguaging spaces as a conceptual tool for understanding the spaces / … / which highlights the ways in which individuals’ linguistic practices are related to wider social structures’. We discuss a sample of 15 billboards/signs collected from different areas within the boundaries of Ndola collected between 2011 and 2021. Drawing from these samples we address the following interrelated research questions:

What language/s are being used and how is meaning being made in advertising signs?

What insight do these signs provide into current language practices in Ndola and what changes, if any, do they reflect?

How is the language use of these signs related to the wider material culture and socio-economic contexts?

The paper begins with a discussion of some recent work documenting linguistic landscapes across Africa highlighting broader trends and patterns. We then shift our focus to the specific context of Zambia providing an overview of the linguistic landscape in which our work is located. Next, we present examples of advertisements we have collected and discuss the different uses and roles of language in these spaces. From our analysis and findings, we draw conclusions about the current language practices we have identified, about how they are linked to the specific Zambian material culture in which they are embedded, and about the implications they may have for future policy and practices.

Studies of linguistic landscapes in Africa

The majority of studies of multilingualism in Africa focus on spoken multilingualism, or on wider sociolinguistic aspects of multilingual societies in Africa. Only more recently has written multilingualism in African contexts been discussed, often in relation to linguistic landscapes. Such work includes analyses of multilingual writing in Eritrea (Lanza and Woldemariam Citation2009), Nigeria (Okanlawon and Oluga Citation2008), Rwanda (Rosendal Citation2009, Citation2010), South Africa (Alexander Citation2009; Stroud and Mpendukana Citation2009; Ngwenya Citation2011) and Uganda (Reh Citation2004; Nakayiza Citation2012). The linguistic landscape of Zambia has also been discussed in a number of recent works, such as Banda and Jimaima (Citation2015, Citation2017), Jimaima (Citation2016), Simungala (Citation2020) and Simungala and Jimaima (Citation2021).

Reh (Citation2004), based on a study of the linguistic landscape of Lira municipality in northern Uganda, where English and Luo are used in writing, develops a typology of written multilingualism within which the role of the respective languages can be described and analysed. The typology includes ‘duplicating multilingual writing’, where exactly the same text is presented in more than one language, ‘fragmentary/overlapping multilingual writing’, where the full information is given only in one language, with selected parts translated into an additional language/s, and ‘complementary multilingual writing’, where some information is given in one language, and other information is given in an additional language/s, so that knowledge of all languages involved is required to understand the whole message. Reh notes that the relationship between the different languages is often asymmetric, and reflects a hierarchy of languages.

A different situation is described for Mekele in Ethiopia (Lanza and Woldemariam Citation2009), which is characterised by the use of Amharic, Tigrinya and English. Amharic has a long tradition as official and national language in Ethiopia, while Tigrinya is a regional lingua franca. Since 1991 Ethiopia has followed a policy of ethnic federalism which has accorded more prominence to regional languages and the use of Tigrinya in public domains has increased since then. Both Amharic and Tigrinya have a long tradition of writing in contrast to many other African languages, and so written communication is not strongly associated with English.

Lanza and Woldemariam (Citation2009, 201/2) comment that English does not fulfil an important communicative function, but rather English ‘serves a symbolic function as a marker of modernity for the language users in this remote city of Ethiopia’. As in many other global contexts, English often serves to index modernity and is associated with a progressive, international, global outlook (e.g. Piller Citation2003; Wei-Yu Chen Citation2006). It seems that this function is related to the fact that both Amharic and Tigrinya are fulfilling national functions in Ethiopia. Similarly, in Rwanda, where French and Kinyarwanda fulfil many national linguistic functions, English in multilingual advertising functions to index modernity, progress and globalisation (Rosendal Citation2009). In contrast, in African countries where English fulfils more functions as a national language of wider communication, the use of English as primarily indexing internationalism and modernity is less pronounced.

South Africa is probably the African country for which multilingual writing and multilingual landscapes have been described in most detail (e.g. Kamwangamalu Citation2008; Stroud and Mpendukana Citation2009; Ngwenya Citation2011). While during apartheid Afrikaans and English were the only two official languages of South Africa, in the post-apartheid 1996 constitution, eleven languages are designated official languages. Ngwenya (Citation2011) notes that in advertising, African languages came to be used only after the end of apartheid, and that this reflects the rising economic importance of the black middle class. Since African languages are an important factor for ethnic and political identity in South Africa, their use in advertising is meant to attract speakers of African languages through evoking this identity: ‘Many black people regard a robust use of their indigenous languages as one of the core elements of being a South African and they have asserted this viewpoint in language domains such as advertising’ (Ngwenya Citation2011, 4).

Focussing on the use of multilingual writing in Nigeria, Okanlawon and Oluga (Citation2008) note that the use of African languages such as Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba in advertising and other public writing in Nigeria has significantly increased in the first decade of the 2000s:

For a long period, English, because of its official status as the major language of the press/mass media, dominated Nigerian advertisement as most adverts especially poster, handbill, billboard, newspaper or magazine adverts were mainly in English. […] However, a wind of change is blowing in the field of advertisement in Nigeria which is evident in the preponderance of contemporary adverts with their copy messages communicated in indigenous Nigerian languages, especially the major ones. (Okanlawon and Oluga Citation2008, 42)

In the Zambian context, Jimaima (Citation2016) and Banda and Jimaima (Citation2017) show that there is often a mismatch between the visibility of languages in signage and the actual language practices of communities. For example, in the Livingstone central business district, signage tends to be monolingual English whilst the actual language practices of the community obtained through observations and interviews, reveal that Tonga, Bemba, Lozi and Nyanja, and importantly, combinations of these languages are the most commonly used languages in everyday interactions. They also observed signs in both Nyanja and Bemba in a predominantly Tonga speaking area in Livingstone, also pointing to the fact that at least some of the local language use in the community is being reflected in signs even though many other languages are not represented. A similar situation was reported for the city of Lusaka where Nyanja is the legislated official regional language. The signs dealt with in this case are predominantly names of shops, restaurants and bars and Banda and Jimaima (Citation2017) report that while the choice of language may have personal connotations they are also more broadly reflective of a multilingual space and the freedom to name business outlets with no regard to what may be deemed the official language of the region. This directly correlates to the mobility of populations in the communities – speakers are considered to have a Zambian national repertoire of languages that they manipulate in naming businesses irrespective of location. This then allows even languages with fewer speakers to claim some of this space and in this sense provide a vehicle for their valorisation.

This situation in Zambia, with the use of multiple languages for shop signs, the description of Nigeria and South Africa, all reflect the fact that the use of African languages in advertising has increased over the last decade. The ‘wind of change’ which Okanlawon and Oluga note is blowing across the sociolinguistic landscape of Nigeria is a wider, continent-wide phenomena, which can be seen as part of an ‘African language renaissance’: the increased use of African languages in a variety of domains, functions and public discourses, including media, music, film and education, in the twenty-first century, brought about through a mixture of advocacy, regionalisation, technology development and changing attitudes.

The language situation and linguistic practices in Zambia

Although the number of languages spoken in Zambia varies according to different sources, the most recent official census (Zambia Census Citation2010) identifies 73 different ethnic groups, a distinction which to some extent correlates with linguistic differences. Lewis (Citation2009) lists 43 living languages, whereas Ohannessian and Kashoki (Citation1978), identified 73 different language varieties which they grouped into 26 dialect clusters.

The main Zambian languages in terms of number of speakers are Bemba, Nyanja, Tonga and Lozi, each spoken predominantly in different parts of the country (see ). Bemba is spoken by 33.5% of the 13 million inhabitants as either a first or a second language, and Nyanja is spoken by about 14.8%. The number of speakers is distributed unevenly between rural and urban populations as shown in . Bemba and Nyanja are widely spoken in the capital Lusaka and the Copperbelt province, which includes major mining and administrative centres such as Ndola and Kitwe (cf. Chisanga Citation2002; Spitulnik Citation1998).

Table 1. Main languages of Zambia by number of speakers (Zambia Census, CSO 2010).

English is spoken by fewer than 2% of the population as a first language, but is a dominant second language, at a similar level as Bemba, particularly in urban areas. At independence in 1964, despite the limited knowledge of English across the country, Zambia adopted a strongly English-based language policy, with African languages playing a restricted role in public discourse. English remains the official language of the country, playing a major role in public administration, the legal system and government. The constitution, for example, states that in order to be elected to parliament, candidates have to be over 18 years old and proficient in English. The dominant function of English in government is matched by its function in business and industry, particularly in the formal sector. Here, English is used pervasively, and is closely linked with economic success.

English is also the main language of the media, and the majority of newspapers, magazines and television programmes available in Zambia, as well as the majority of internet sites and computer applications, are in English, with only the radio having a slightly higher proportion of use of African languages. In education, African languages were used in colonial times to some extent, and have recently been re-introduced in state schools. However, the use of African languages as a medium of instruction (MOI) is restricted to the primary level, with the current 2013 Language in Education Policy requiring that teaching should start in a familiar language, interpreted as one of the seven regional languages, although this has scope for the inclusion of other languages. Learners then transition into English as an MOI in the 4th year of primary school.Footnote1 This new legislation also applies to private schools, which have traditionally been entirely English language based, without any recognised role for African languages in the classroom. Overall, English is thus the major language of official and formal domains of language use.

African languages have typically served two central functions in Zambia. On the one hand, they are languages spoken by the vast majority of the population, and are thus the main languages of day-to-day communication. They are lingua francas widely used in spoken interactions, in private and local settings, including in markets, shops and other domains of the ‘informal’ economy, in banks or government offices, as well as more formally in (traditional) ceremonies or church services. By contrast, the use of local African languages in writing is comparatively restricted. There are a few regular magazines published in African languages, such as the Bemba magazine Icengelo, some school primers, readers and a few novels and non-fiction texts. African languages are also found in religious contexts, such as in hymns or Church decorations.

The second central function of Zambian African languages is fulfilling symbolic functions. Seven African languages are designated ‘national languages’: The four languages with the largest numbers of speakers, as noted above, Bemba, Nyanja, Tonga and Lozi, as well as three languages spoken in the Northwestern province, where there is no one dominant language: Kaonde, Lunda and Luvale. The national languages thus represent the majority of speakers, as well as the main languages from all regions of the country. However, the status as national language does not imply any practical function. Rather, the adoption of national African languages can be seen as symbolic, in counter-distinction to the pragmatically based English language policy.

While, at least at the inception of the post-independence language policy, English was seen as the most practical and politically parsimonious choice as official language, the national languages served as a symbol of Zambian and African cultural identity. For example, several English-based place names were replaced by African language-based ones (e.g. Mbala for Abercorn, Chipata for Fort Jameson), and the symbolic choice of new African language currency terms (ngwee and kwacha) after independence contrasts with the practical dominance of English in financial and economic domains (Marten and Kula Citation2008a).

The Zambian language situation is comparable to other African countries that have adopted an exoglossic language policy, such as Nigeria or Ghana, or many ‘francophone’ African countries. English was adopted as an official language in Zambia as it was perceived as a ‘neutral’ language without any substantive associated ethnic or linguistic groups. This was meant to help the development of national identity and unity, which was perceived as being threatened by a multilingual language policy. However, Kashoki (Citation1990), as others, has argued that the perceived neutrality of English does not extend to social domains, where knowledge of English is often restricted to the political, economic and social elite, who thus may employ English as part of a strategy of linguistic exclusion. In addition, national identity does not have to be based on monolingualism, and the specific Zambian multilingual patterns may in fact provide a better foundation for Zambian national identity (see Marten and Kula Citation2008b). Furthermore, in day-to-day practice, boundaries between the different languages are fluid, and many speakers have access to a range of different linguistic repertoires. Because of this translanguaging is common and constitutes an integral part of Zambian linguistic identity and language practice (Mambwe Citation2014).

As mentioned above, Zambian languages have been introduced into state and private schools, and have attained a very high profile in locally produced, contemporary popular music, where a number of Zambian artists use – often a mix of – African languages (Banda Citation2019). Part of this renaissance is the increased visibility and use of Zambian languages in the linguistic landscape as we discuss below.

Billboards, advertisements and translanguaging spaces

Ndola is the third-largest city of Zambia and the administrative capital of the Copperbelt province, close to the border with the DRC. Although historically a Lamba speaking area, the main language of Ndola is now Bemba, due to large numbers of Bemba speakers who moved from the Northern Province to work in the copper mines over the last 100 years, and the subsequent use of Bemba as lingua franca of the region.

The linguistic landscape of the city is constituted mainly by names and other signs on shop fronts and public buildings. There are street names (mainly in the city centre) and public signs from the municipal government with texts such as Welcome to Ndola – the Friendly City or Keep Ndola Clean. There is also a long tradition of commercial advertising, originally consisting of hand-written/painted advertisements on walls of commercial property. These were professionally and artistically produced, and were predominantly in English, the main exception being names of businesses and shops, such as the Mukuba Hotel. This use of English was in keeping with the role of English as the main language of writing, and the main language of formal business and commercial activity.

Over the last two decades, the form and production of public advertising has changed, in particular through the introduction of large billboards on roadsides. Initially, these billboards were rust-red-painted, large steel structures (), while more recently billboards of different sizes have been added, built from aluminium, plastic, PVC or acrylic, and some boards are fixed to existing structures like poles or lamp posts ().

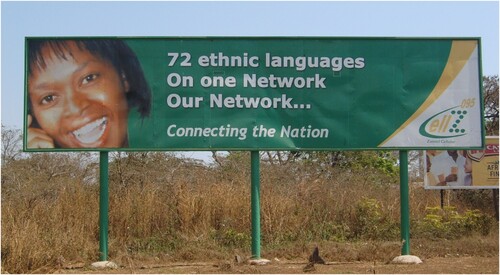

These billboards had a profound impact on the urban space, as well as on the visual and linguistic landscape of Ndola. The most prominent commercial users of the new advertising space are mobile phone companies and banks.Footnote2 In particular mobile phone companies, possibly because of their relation to spoken language, have played an important role in endorsing Zambian languages and multilingualism. This is so even where no actual local languages are used in the advertisement, as seen in an early, 2007 advert by the now defunct CellZ network ():

shows that initially the dominance of English as the language of advertising did not change with the advent of designated advertising billboards, even when the reference was made to language diversity as in this case. More recently, however, African languages have come to be used more often and are increasingly playing a more prominent role. The main African languages used in the Zambian context, particularly on the Copperbelt, are Bemba and Nyanja, the two largest Zambian languages in terms of numbers of speakers.

In the early 2010s African languages were mainly used as ‘fragments’, that is, as words, or phrases which did not constitute a meaningful, complete text in themselves, and which typically did not contribute to the core propositional meaning of English-based texts. They were thus often used more as a strap line. The main information (and propositional meaning) was typically given in English, while the African languages typically contributed a heading or theme of the particular advertisement campaign but were often displayed more prominently than surrounding text in terms of font size or colour. However, we can see here the beginning of a shift to reflecting in writing multilingual practices and translanguaging common in spoken discourse. This is, for example, seen in and below where chezelela and mahala are Nyanja catch words meaning ‘talk continuously’ and ‘for free’ but which occur as themes whose main message is then subsequently explained and developed in English.

Although the two languages are unbalanced, the whole text is only fully accessible through both languages, constituting an instance of complementary multilingual writing. In addition, even the English text uses local colloquialisms and specific Zambian usage. In the text ‘get 30 days of free calling, for only a pin’, pin is a colloquial reference to one thousand Zambian Kwacha.Footnote3 We can thus see that the writing reflects the lived experiences of the community it serves. The language use in this case serves to localise a global message in the particular Zambian context, and demonstrates understanding of and identification with the local context.

What we observe is that these billboards have increasingly become home to more complex and dynamic language use and as such represent interesting translanguaging spaces. Where the initial use of African languages tended to be manifest as fragments in an English language base, this soon saw shifts that even more closely reflect the translanguaging practices of speakers, where meaning-making exploits all resources available to speakers and where more fluid language practices do not always mirror expectations based on traditional notions of language as bounded entities (Makoni and Pennycook Citation2007, Wei Citation2011, Citation2018; García and Kleyn Citation2016). In the adverts in and , we see the presentation of language mirroring language use where English and the African language are used together to create meaning. In , the main text Tuesday Njikata meaning ‘Tuesday be mine’, literally ‘Tuesday hold me’, is important to express the central message that there is an offer that only applies on Tuesdays.

Similarly, in , which is an advert for a smartphone, the central message about the phone is expressed both in English and Bemba with the seamless interweaving of the two languages in similar fashion as in spoken language: 3G Rio Smartphone ya Chikata ‘A powerful/strong 3G Rio smartphone’. The signage in this case directly reflects local language use patterns.

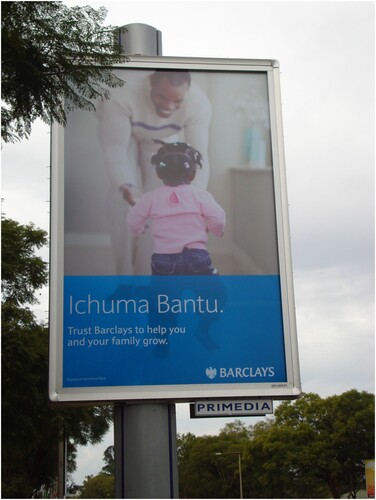

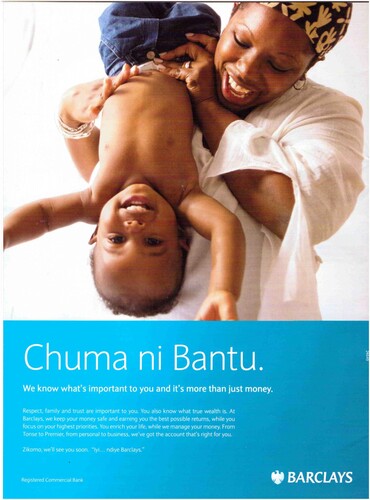

A more complex example of the use of African languages in Zambian advertising is a series of advertisements run by Barclays bank, one of the largest global banking enterprises with a strong market presence in Zambia. The adverts span both print media and public displays, and although not strictly speaking part of the linguistic landscape, we will look at the print version in addition to the display version, as it is illuminating to compare the two, and to look at the use of language in both. The adverts use either a combination of English and Bemba or English and Nyanja, although given that the adverts are both in Ndola, an otherwise predominantly Bemba speaking area, it is assumed that all three languages are accessible and part of the linguistic repertoires of the community. This thus constitutes examples of overt and visible multilingual writing (Reh Citation2004). The main heading of the advertisement series is Ichuma Bantu (‘Wealth is people’) in Bemba and the corresponding Nyanja Chuma ni Bantu. In the display version (), a baby girl is running towards the welcoming arms of (presumably) her father. The Bemba text is given in larger font size as a heading, and a smaller English text is found below: Trust Barclays to help your family grow. The themes ‘trust’ and ‘family’ are central to the advertisement, and are more elaborately developed in the print advert, which allows more space for text ():

Chuma ni Bantu.

We know what’s important to you and it’s more than just money.

Respect, family and trust are important to you. You also know what true wealth is. At Barclays, we keep your money safe and earning you the best possible returns, while you focus on your highest priorities. You enrich your life, while we manage your money. From TonseFootnote4 to Premier, from personal to business, we’ve got the account that’s right for you.

Zikomo, we’ll see you soon. ‘Iyi … ndiye Barclays.’

The use of Nyanja in this example serves to localise the message both in drawing on the social setting and values of the community but also on the patterns of language in which the culture is practiced. Chuma ni Bantu, as noted above, provides the theme of the advert, and through the use of an idiomatic expression as the central theme harnesses cultural wisdom and knowledge transmitted through African languages – creating a link to ‘tradition’ and rootedness in culture. The theme developed is that true wealth is the love and safety of the people that surround us, in particular the family – as is emphasised by the images of both the display and the print version. Note here that the central message is given wholly in the local language reflecting the shift from a more fragment role as seen earlier in and . Within the print advert Zikomo, a well-known Nyanja politeness form, ranging in meaning from ‘Thank you’ to ‘You’re welcome’, is used to express respect, resonating with the earlier prominent use of ‘respect’ at the beginning of the paragraph, and also signals knowledge of and affiliation to Nyanja culture (and Zambian/African culture more widely), where the linguistic expression of respect is often regarded as important. And because there is no good English equivalent of zikomo, i.e. one that would also carry the cultural connotations, this is also the point at which speakers would translanguage into the local language when speaking English and thus the text directly captures spoken linguistic practices. The final statement in Nyanja ‘Iyi … ndiye Barclays’. (‘This … is Barclays’), also expresses confidence in a brand in the local language which is more likely to be perceived as more real and closer to the people as is also seen in spoken language. The advert text tries to capture this by the use of quotation marks to express that it is no longer the bank’s narrator talking, but a fellow customer or a friend – aiming to reflect how the community would converse on the matter.

The points at which translanguaging occurs reflects some of the different ways that English and Nyanja are manipulated by speakers: Nyanja is associated with informal contexts and carries higher solidarity value, while English can be associated with business, modernity and social aspiration. Through the use of Nyanja, the advert claims this informal, personal space for Barclays as well, and, consistent with the main theme of the advert, makes Barclays part of the circle of friends and family. The use of Nyanja in this text thus plays different roles. On the one hand, it aims to make the advert more authentically Zambian, adding a local dimension to a global financial operator by reflecting the multilingual setting and language use. On the other hand, it aims to invoke cultural and social spaces typically reserved for African languages – respect, informality, the personal. The fact that the advertisements are produced using two different Zambian languages (Nyanja and Bemba), similar to the language choice in mobile phone adverts, supports a trilingual Zambia linguistic identity of English, Bemba and Nyanja, the three languages which are the three main languages in terms of number of first and second language speakers.Footnote5

One area in which African languages have tended to be used in writing for a longer time is in health contexts where outbreaks of Malaria or dysentery would have information distributed by the Ministry of Health to communities in the regional languages. This was generally found more in leaflets but with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, this practice has been transferred also to billboard advertising where text is almost exclusively in an African language. In Ndola, we again see the use of Bemba () and Nyanja ( – poster signage) as well as also exclusive uses of English seen as part of .

It is striking that the very detailed explanation of the sign in on Uku ichingilila ‘Protecting yourself’ is exclusively in Bemba and reflects the emerging significant position of African languages in the linguistic landscape. The gradual increase from fragments to a more translanguaged text is, we argue, what has made this possible. A similar dominance of Nyanja is also seen in the bottom poster of which although starting with an English caption, provides all the detailed explanation of how the virus develops in an African language. This is almost a mirror image of what we saw previously in early adverts as in and , for example, where the African language provides the strap line and everything else is in English. Here, however, it is more an instance of translanguaging, starting with the English text ‘Be alert!’ written in larger font, with a smaller font sub-title ‘Corona virus is here’, and then continuing in Nyanja in large uppercase text in the centre of the poster saying Zisungeni ndi mita ‘keep yourselves safe with one meter (social distancing)’. In this text mita is a loanword from English meter and also an instance of translanguaging. This text is then followed by further detailed explanation in Nyanja but both English and Nyanja – indeed their translanguaged use – is needed to understand the whole message. This is very reflective of the kinds of language use that takes place in conversations within the community on the best approaches to adopt with regard to the pandemic. The top poster in where English is used reflects that there is a comfortable co-existence of multiple languages that are understood as being a part of the language repertoires of the community and which are equally represented in the linguistic landscape.

A final area we briefly look at is education, which is an area, particularly in urban areas like Ndola, where multilingual practices have been less seen, with most educational adverts, e.g. nursery/pre-school and primary school traditionally being in English, perhaps because of the private nature of some of this provision. However, even in government schools, which tend to have a motto displayed at the school entrance, messages would generally be in English, despite the pupils naturally being multilingual.

But even in this domain, we can see a change in attitude. A current campaign to boost early childhood development and to increase awareness of the importance of play for young children harnesses African languages. The campaign is developed by UNICEF Zambia and the Zambian Early Childhood Development Action Network (ZECDAN) with support from the LEGO Foundation. The billboard includes the strapline ‘I play, I learn, I thrive’ translated into different Zambian languages (see for the Bemba version in Ndola). Furthermore, the campaign is supported by proverbs from different Zambian languages:

The Playful Parenting campaign, launched today in Zambia, will highlight local proverbs that encourage nurturing care towards children. These Zambian proverbs including ‘Imiti ikula empanga’ (Bemba), ‘Ng’ombe ni matole’ (Nyanja) and ‘Mabiya afwida kumubumbi’ (Tonga) will be used on billboards across 20 cities and towns in Zambia, as well as on social media. (UNICEF Zambia Citation2020)

In , we see multilingual writing where the advert is led by a Bemba proverb imiti ikula e mpanga ‘trees that grow make the forest’ appealing to the idea that investing in children will secure our future as they will be the leaders/breadwinners of the future. There is then parallel text in both English and Bemba presenting an identical message and again reflecting that the local African languages have entered the linguistic landscape and are central to the message as the languages are central to the day-to-day experiences of the community. The adverts in this way acknowledge that play will take place in the local language or at least that they will be part of the repertoires of languages that the community exploits.

Language and material culture

Previous studies of the linguistic landscape have drawn attention to the fact that language use is embedded in the material culture and specific socio-economic conditions in which it is used. Stroud and Mpendukana (Citation2009), for example, suggest that the signage in the Cape Town township of Khayelitsha mirror the socio-economic status of individual inhabitants and that the specific linguistic landscape they study shows the interaction between language and other material culture in place (see also Banda Citationforthcoming). This perspective lends another dimension to our analysis of the linguistic landscape of Ndola. Here, too, language interacts in different, and quite direct ways with social and economic dynamics in contemporary Zambia.

The language used in the examples we have discussed reflect the contemporary and changing language situation in Zambia, and the increased use of African languages for writing in public spaces. However, language use in these advertisements is also interactional and strategic. Designers and copy editors of advertising campaigns will assume that the specific use of different languages to convey different meanings will ultimately convince more people to buy the product advertised. In order to achieve this aim, the adverts create narratives and images which are constructed to appeal to the target audience.

The most striking example of this in our data is the Barclays campaign which we introduced above. As noted above, the advert uses an African language such as Bemba or Nyanja to establish a link to African knowledge (through the use of the proverb which gives the advert its overall theme) and values (such as politeness), while providing the relevant financial information in English. This is paired with images of a nuclear family – mother, father, child – dressed in light colours: pink for the child, white for the parents, with an African-style head dress for the woman. The image potential customers are invited to identify with is of an affluent, urban, multilingual, middle-class lifestyle. The advert partly reflects cultural stereotypes, and partly reinforces them, harnessing a chronotope of social life (Agha Citation2011). We see a similar imagery in the UNICEF/LEGO advert – the leading Bemba proverb, the use of both Bemba and English, and the images of a nuclear family.

It is noteworthy that the strong imagery around nuclear families stands in contrast with ‘traditional’ conceptions of family, which would typically be larger, and involve multiple generations. In particular, the prominence of the father image conveys a ‘modern’ conception of male gender roles and active engagement in parenting. It is worth noting in this context the strong role of Christianity in the socio-cultural make-up of Zambia. Zambia is officially a Christian country, with over 90% of the population identifying as Christian, with Christianity explicitly mentioned in the constitution. The middle-class image of the nuclear family thus also indexes Christian motifs and conceptions of familyhood.

A different strategy can be seen in the public health adverts. Here, the aim is not to attract customers, but to ensure that the relevant information is available as widely as possible and to change public behaviour, and so there is a much higher reliance on African languages, which, as we noted at the beginning, are much more widely used in everyday spoken interactions than English. Also, rather than images, the public health adverts use graphics which emphasise the didactic nature of the text.

Starting from the use of language and the multilingual nature of the adverts and signs discussed here, we can then take into account the images and messages they intend to convey, and through this develop an understanding of their interactional and strategic-communicative function. We have seen that both the commercial Barclays advert and the third-sector UNICEF/LEGO advert portray a particular lifestyle centred around a middle-class nuclear family which addresses a particular part of society, and to some extent also resonates with Christian values. In contrast, the public health adverts about COVID-19 use graphics, rather than images, are largely in African languages and have more text, reflecting their different function and perceived audiences. These examples show how the linguistic landscape in Ndola is embedded in and relates to the wider socio-economic and cultural contexts in which this landscape is located.

Understanding the changing linguistic landscape of Ndola

As stated above, this paper has engaged with three interrelated research questions and these are (1) what language/s are being used and how is meaning being made in advertising signs?, (2) what insight do these signs provide into current language practices in Ndola and what changes, if any, do they reflect? and (3) how is the language use of these signs related to the wider material culture and socio-economic contexts? With regard to the first question what we are able to see increasingly in the linguistic landscape of Ndola is that there has been a shift from what we might describe as English dominant, or monolingual language use to the use of more multilingual advertising and changing patterns in the use of a wider variety of Zambian languages such as Bemba and Nyanja. A significant point to note is the shift in the languages of wider communication used in Ndola, and by extension the Copperbelt. These areas were previously mainly Bemba speaking but the very wide use of Nyanja in the linguistic landscape shows a shift in perceived regional languages and the overall more multilingual practices as also Banda and Jimaima (Citation2017) and Simungala and Jimaima (Citation2021) note.

Importantly, when viewed from a translanguaging perspective, or as a set of translanguaging spaces (Wei Citation2011, Citation2018; Reilly Citation2021), what we see are not signs that are composed of separate and bounded languages but rather we see language practices that are more fluid and dynamic. Such practices, we argue, more closely reflect the complex ways in which language is used locally in everyday interaction to make meaning. As suggested by Wei (Citation2018, 23) translanguaging spaces represent ‘a space where language users break down the ideologically laden dichotomies between the macro and the micro, the societal and the individual and the social and the psychological through interaction’. The changes in practice that we have charted represent important shifts in the ways in which the wider population of Ndola are invited to engage with and take meaning from the signs.

With respect to the second and third questions, we believe that exploring the linguistic landscape as we have in this case study offers us many insights into the use of language. Through the data we have collected and discussed here we have been able to show that over the last 10–20 years the use of Bemba and Nyanja in advertising and public displays has significantly increased the presence of African languages in the linguistic landscape of Ndola. Prior to this, uses of written African languages in the public space were much more limited, and mainly found in isolated words such as place names, the names of shops and businesses or the currency terms kwacha and ngwee.

Apart from the health sector, the particular industries making use of these displays are mainly banks and mobile phone companies, which are associated with globalisation, communication, technology, innovation and modernity, for example. This indicates that African languages, or at least Bemba and Nyanja, have entered new domains of public discourse, in addition to more traditional domains of personal or local life, spoken, more direct – and hence spatially more restricted – language use and ‘traditional’ culture. In the widely used UNESCO (Citation2003) descriptors of language vitality, shifts in the domain of language use, as well as response to new domains and media, are important criteria for measuring language vitality and endangerment.

The increased use of African languages and translanguaging practices in public writing and contemporary advertising are important and intentional changes in the linguistic landscape that indicate a strengthening of African languages overall and increased parity in the use and status of Bemba, Nyanja and English. These shifts in practices are particularly significant in that the linguistic landscape ‘reflects the relative power and status of the different languages in a specific sociolinguistic context’ (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2006, 67–68) as well as the changing socio-economic context. With specific reference to Ndola, and Zambia more broadly, these are very positive developments both in terms of language vitality but also in terms of ensuring that language practices in the public domain are more inclusive and representative of people’s day-to-day lives.

Concluding comments

In this paper, we have explored the linguistic landscape in Ndola, a major urban space in Zambia. In order to better understand language use and multilingual practices in the linguistic landscape of Ndola, we have adopted three different analytical approaches. First, we looked at the chronology of multilingual signage in Ndola, and noted that there has been an increase in the use of African languages. Second, we proposed that this increase is linked to translanguaging, and that established oral practices of translanguaging are being increasingly reflected in public written language. Third, we have discussed multilingual signage in the context of the relevant material culture and specific Zambian socio-economic discourses which frame and feed into the linguistic landscape.

We have shown how the use of African languages has increased and that African languages are becoming more valorised, for example as indices of cultural knowledge. We also noted that African languages are part of the chronotope of the raising and aspirational middle class, that is also linked to nuclear familyhood. Through these dynamics, African languages have secured important spaces in contemporary discourse.

Further study of other instances of multilingual writing – such as in creative writing, newspapers, writing in music and TV – and of other Zambian contexts is necessary to develop a fuller understanding of the state and development of written multilingualism in Zambia, and how this impacts on the overall linguistic situation. If African languages are to be used as fully functional languages in their countries of use – and many scholars have argued that this is essential for the development of African nations (Kashoki Citation1990; Webb Citation2002; Alexander Citation2009) – they have to develop a strong presence in public discourses, including written discourses. Further study will show whether the case study discussed in this paper is part of a more fundamental revalorisation of African languages and a wider African language renaissance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The problems associated with the use of English in education and the advantages of L1 education in Zambia and other African countries have long been recognized (e.g. Tambulukani and Bus Citation2012; UNESCO Citation1953, Citation2010; Williams Citation1996).

2 Mobile phone companies in particular have been instrumental in changing outdoor advertising in many African countries in addition to Zambia; see e.g. Rosendal (Citation2009) for Rwanda, Annette Islei (p.c.) for Uganda.

3 Pin to refer to K1000 derives from a time when banknotes of the value of K1000 were customarily held/pinned together by a paper clip.

4 Tonse (‘everything/all’) is the name of one of Barclays’ Zambian account schemes, reflecting the use of African languages in branding, as was also seen above in the names for different marketing campaigns of mobile phone companies.

5 This also reflects what Banda and Jimaima (Citation2017) and Simungala and Jimaima (Citation2021) describe as a shift in the use of regional languages from their designated areas showing that in particular Bemba and Nyanja are becoming more widely used in areas away from where they are the designated lingua francas, discussing in particular how Bemba is much more widely used in Lusaka, which was previously a predominantly Nyanja area. Here we see Nyanja being used in a previously designated Bemba speaking area.

References

- Agha, Asif. 2011. “Commodity Registers.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 21 (1): 22–53.

- Alexander, N. 2009. “Evolving African Approaches to the Management of Linguistic Diversity: The ACALAN Project.” Language Matters 40 (2): 117–132.

- Banda, F. 2019. “Beyond Language Crossing: Exploring Multilingualism and Multicultural Identities Through Popular Music Lyrics.” Journal of Multicultural Discourses 14 (4): 373–389.

- Banda, F. forthcoming. “Sociolinguistics and Applied Linguistics.” In The Oxford Guide to the Bantu Languages, edited by L. Marten, E. Hurst, N. C. Kula, and J. Zeller. Oxford: OUP.

- Banda, F., and H. Jimaima. 2015. “The Semiotic Ecology of Linguistic Landscapes in Rural Zambia.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 19 (5): 643–670.

- Banda, F., and H. Jimaima. 2017. “Linguistic Landscapes and the Sociolinguistics of Language Vitality in Multilingual Contexts of Zambia.” Multilingua 36 (5): 595–625.

- Barni, M., and C. Bagna. 2010. “Linguistic Landscape and Language Vitality.” In Linguistic Landscape in the City, edited by E. Shohamy, E. Ben-Rafael, and M. Barni, 3–18. Bristol: Blue Ridge Summit, Multilingual Matters. doi:10.21832/9781847692993-003.

- Blommaert, J. 2013. Ethnography, Superdiversity and Linguistic Landscapes: Chronicles of Complexity. UK: Channel View Publications.

- Cenoz, J., and D. Gorter. 2006. “Linguistic Landscape and Minority Languages.” In Linguistic Landscape: A New Approach to Multilingualism, edited by Durk Gorter, 67–80. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Chisanga, T. 2002. “Lusaka Chinyanja and Icibemba.” In Prah Speaking in Unison: The Harmonisation of Southern African Languages, edited by Kwesi Kwaa, 103–116. Cape Town, South Africa: CASAS.

- Coupland, N. 2003. “Introduction: Sociolinguistics and Globalisation.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 7 (4): 465–472.

- García, O., and T. Kleyn. 2016. Translanguaging with Multilingual Students: Learning from Classroom Moments. London: Routledge.

- Gorter, D. 2018. “Linguistic Landscapes and Trends in the Study of Schoolscapes.” Linguistics and Education 44: 80–85.

- Jaspers, J. 2018. “The Transformative Limits of Translanguaging.” Language & Communication 58: 1–10.

- Jimaima, H. 2016. Social Structuring of Language and the Mobility of Semiotic Resources across the Linguistic Landscapes of Zambia: A Multimodal Analysis. PhD dissertation, University of the Western Cape.

- Kamwangamalu, N. M. 2008. “From Linguistic Apartheid to Linguistic co-Habitation: Codeswitching in Print Advertising in Post-Apartheid South Africa.” Journal of Creative Communications 3 (1): 99–113.

- Kashoki, M. E. 1990. The Factor of Language in Zambia. Lusaka, Zambia: Kenneth Kaunda Foundation.

- Landry, R., and R. Bourhis. 1997. “Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality: An Empirical Study.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16: 23–49.

- Lanza, E., and H. Woldemariam. 2009. “Language Ideology and Linguistic Landscape: Language Policy and Globalization in a Regional Capital of Ethiopia.” In Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery, edited by E. G. Shohamy and D. Gorter, 189–205. New York: Routledge.

- Lewis, M. P. 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. 16th ed. Dallas, TX: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/.

- MacSwan, J. 2017. “A Multilingual Perspective on Translanguaging.” American Educational Research Journal 54 (1): 167–201. doi: 10.3102/0002831216683935

- Makoni, S., and A. Pennycook (eds.). 2007. Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages (Vol. 62). Multilingual Matters.

- Mambwe, Kelvin. 2014. Mobility, identity and localization of language in multilingual contexts of urban Lusaka. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of the Western Cape.

- Marten, L., and N. C. Kula. 2008a. “Meanings of Money: National Identity and the Semantics of Currencies in Zambia and Tanzania.” Journal of African Cultural Studies 20: 183–199.

- Marten, L., and N. C. Kula. 2008b. “One Zambia, one Nation, Many Languages.” In Language and National Identity in Africa, edited by Andrew Simpson, 291–313. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Nakayiza, J. 2012. The sociolinguistics of multilingualism in Uganda: A case study of the official and non-official language policy, planning and management of Luruuri-Lunyara and Luganda. Unpublished PhD dissertation. London, UK: SOAS, University of London.

- Ngwenya, T. 2011. “Social Identity and Linguistic Creativity: Manifestations of the use of Multilingualism in South African Advertising.” Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 29: 1–16.

- Ohannessian, S., and M. E. Kashoki (eds.). 1978. Language in Zambia. London: International African Institute.

- Okanlawon, B. O., and S. O. Oluga. 2008. “An Examination of Language Use in Contemporary Nigerian Advertisement Copy Messages.” Marang: Journal of Language and Literature 18: 37–48.

- Piller, I. 2001. “Identity Constructions in Multilingual Advertising.” Language in Society 30: 153–186.

- Piller, I. 2003. “Advertising as a Site of Language Contact.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 23: 170–183.

- Reh, M. 2004. “Multilingual Writing: A Reader-Oriented Typology – with Examples from Lira Municipality (Uganda).” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 170: 1–41.

- Reilly, C.. 2021. Malawian Universities as Translanguaging Spaces. English-Medium Instruction and Translanguaging. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Rosendal, T. 2009. “Linguistic Markets in Rwanda.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 30 (1): 19–39.

- Rosendal, T. 2010. Linguistic Landshapes: A Comparison of Official and Non-official Language Management in Rwanda and Uganda, Focusing on the Position of African languages. Unpublished PhD diss., University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden.

- Simungala, G. 2020. “The Linguistic Landscape of the University of Zambia: A Social Semiotic Perspective.” Unpublished MA Thesis, University of Zambia.

- Simungala, G., and H. Jimaima. 2021. “Multilingual Realities of Language Contact at the University of Zambia.” Journal of African and Asian Studies 56 (7): 1644–1657. doi:10.1177/0021909620980038.

- Spitulnik, D. 1998. “The Language of the City: Town Bemba as Urban Hybridity.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 8: 30–59.

- Spolsky, B. 2009. “Prolegomena to a Sociolinguistic Theory of Public Signage.” In Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery, edited by Elana Shohamy, and Durk Gorter, 25–39. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Stroud, C., and S. Mpendukana. 2009. “Towards a Material Ethnography of Linguistic Landscape: Multilingualism, Mobility and Space in a South African Township.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 13: 363–386.

- Tambulukani, G., and A. G. Bus. 2012. “Linguistic Diversity: A Contributory Factor to Reading Problems in Zambian Schools.” Applied Linguistics 33 (2): 141–160.

- UNESCO. 1953. The Use of Vernacular Languages in Education. Paris, France: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2003. Language Vitality and Endangerment. Document adopted by the International Expert Meeting on UNESCO Programme Safeguarding of Endangered Languages, Paris 10-12 March 2003. Paris, France: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2010. Why and How Africa Should Invest in African Languages and Multilingual Education: An Evidence- and Practice-Based Policy Advocacy Brief. UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning: Hamburg.

- UNICEF Zambia. 2020. Coinciding with Father's Day, the Government of the Republic of Zambia, UNICEF and the LEGO Foundation launch campaign to highlight the benefits of play for children in Zambia. Press release, 21 June 2021. https://www.unicef.org/zambia/press-releases/coinciding-fathers-day-government-republic-zambia-unicef-and-lego-foundation-launch

- Webb, V. 2002. Language in South Africa: The Role of Language in National Transformation, Reconstruction and Development. Amsterdam, theNetherlands and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Benjamins.

- Wei-Yu Chen, C. 2006. “The Mixing of English in Magazine Advertisements in Taiwan.” World Englishes 25 (3/4): 467–478.

- Wei, L. 2011. “Moment Analysis and Translanguaging Space: Discursive Construction of Identities by Multilingual Chinese Youth in Britain.” Journal of Pragmatics 43 (5): 1222–1235.

- Wei, Li. 2018. “Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language.” Applied Linguistics 39 (1): 9–30.

- Williams, E. 1996. “Reading in two Languages at Year Five in African Primary Schools.” Applied Linguistics 17 (2): 182–209.

- Zambia Census. 2010. Zambia 2010 Census of Population and Housing. National Analytical Report. Lusaka: Central Statistical Office.