ABSTRACT

In recent (socio)linguistic research there is a growing awareness that rural, small-scale multilingualism as the most widespread communicative setting across the globe. Yet, literacy programmes accepting and incorporating this diversity are non-existent. LILIEMA is a unique educational programme currently based in Senegal that addresses the need for enabling learners to use their entire repertoire, nurturing, and validating local knowledges and sustainable multilingualism. This article focuses on the participatory methodologies at the heart of LILIEMA (Language-independent literacies for inclusive education in multilingual areas), born from a collaboration between professional linguists and local teachers, transcribers, research assistants and community members. We explore how the cultural knowledge of local participants and ethnographic and qualitative sociolinguistic data jointly contributes to our thick understanding of the social environment for literacy and how it can make African languages and multilingualism more visible. Furthermore, used methods allow to describe fluid and potentially ambivalent multilingual speech events based on different perspectives motivating choices both in terms of languages ideologies and linguistic practice. LILIEMA pursues the objectives to support and enhance the use of (multilingual) literacy, strengthens languages and linguistic awareness and fosters self-confidence in all sectors of life by creating innovative spaces for small and locally confined languages.

Introduction

In this article, the authors, a group of activists and researchers based in the Global North and in the Global South report on our experiences in jointly developing and running a repertoire-based literacy programme in the Casamance, Senegal’s’ southernmost region. The project emphasises speakers actual, often multilingual language use in written and spoken settings. In the process, African languages and multilingualism become more visible on various levels, supporting socio-cultural identities that do not always fit into fixed constructions or norms. Longstanding mobility and social exchange have shaped and continue to influence the social identities and linguistic repertoires of the inhabitants of this area and of West Africa more generally (Cobbinah Citation2010; Cobbinah et al. Citation2016; Lüpke Citation2018b; Lüpke and Watson Citation2020) and turn this area into a microcosm of local multilingual configurations in which wider areal patterns and place-specific patterns interweave, and in which people’s repertoires are multidimensional and in constant flux. Multilingual societies such as the Casamance defy widely held assumptions of multilingualism as a recent phenomenon associated with urbanisation and migration in late globalisation (Blommaert and Rampton Citation2011). Multilingualism in Casamance can be traced back to the first available written records, created by Portuguese travellers at the end of the fifteenth century (Brooks Citation1993; Green Citation2019). The Casamance can thus be regarded as an area in which rural, small-scale multilingual societies predate European expansion and early globalisation, just as has been shown for a growing number of settings in the Global South, lending plausibility to the assertion that rural, small-scale multilingualism (rather than monolingualism in homogeneous societies) is the oldest and most widespread communicative setting across the globe (Lüpke Citation2016b; Singer and Harris Citation2016; Léglise Citation2017; Evans Citation2018).

In Senegal societal and individual multilingualism remain omnipresent in everyday life. However, the region’s multilingualism is not at all reflected in the official educational system. The project LILIEMA (Language-independent literacies for inclusive education in multilingual areas) counteracts linguistic exclusion created through standard-based monolingual policies in education by not selecting languages but making visible whole repertoires of multilingual speakers. As in the vast majority of African countries, formal education, institutions and the formal economic sector rely on one ex-colonial language, excluding most Africans from full participation in these central areas of public life (Djité Citation2008; Skattum Citation2020; Mufwene Citation2021; Ndhlovu and Makalela Citation2021). Only members of the socioeconomic elite master French, the official language; other learners experience school as an alienating space in which literacy and numeracy are taught in official languages that are not taught as a subject. Local or translocal languages of Senegal are not present in formal education but relegated to sporadic adult literacy campaigns. These campaigns rely on language selection, resulting in the exclusion of most languages of multilingual areas (Lüpke Citation2018a). Broader language and literacy programmes accepting and incorporating the diversity representative for the area are non-existent. As a consequence, the languages most important for people’s identities are systematically undervalued, and only the former colonial languages and additionally languages of religion are valorised and serve as instruments of social mobility (Ngom Citation2010; Ouane and Glanz Citation2010).

Bilingual and multilingual educational programmes have been promoted by UNESCO (Citation2016) in order to create more inclusive literacy environments. Yet, until now, they are based on the selection of a small number of languages of wider communication or languages with large speaker bases. In addition, educational material is often either non-existent or pedagogically poor, since teachers are not trained in the languages they are asked to teach (Heugh Citation2015; Makalela Citation2015; Mufwene Citation2021). The LILIEMA programme has been created against this backdrop.

Our project has created a unique educational programme enabling learners to use their entire repertoire in a written form, adapted to their individual requirements and allowing the transfer of literacy skills to changing contexts and repertoires. Through the implementation of a sustainable literacy programme taught by local teachers and trainers, all languages in speakers’ repertoires, including small languages with low speaker numbers are nurtured, while local knowledges and multilingualisms are validated (Weidl Citation2022). Our model is inspired by longstanding and recent grassroots literacy practices across West Africa (Lüpke Citation2004, Citation2018a, Citation2020, Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Lüpke and Bao-Diop Citation2014) and presents the first formal pedagogical alternative to language-based literacy methods, introducing (trans)languaging pedagogy into the written domain (see also Garcia and Wei Citation2014). While supporting fluid written language use, LILIEMA is also compatible with standard language-based literacies and can be taught independently of and alongside such literacies (Lüpke et al. Citation2021).

The article is structured as follows: In section 2, we provide a brief sociolinguistic profile of Senegal and the Casamance region. Section 3 introduces our team, courses and research, section 4 focuses on the LILIEMA method showing empirical data. Our vision, outlined in section 5, ends the article.

A sociolinguistic overview of Senegal

In this section, we provide an overview of the sociolinguistic setting of Senegal, focusing on factors leading to the limited use and concomitant invisibility of local languages in written form. Senegal hosts a high number both of closely related and unrelated languages; Diallo (Citation2009) counts 25 languages, whereas the Ethnologue mentions 38 living languages (Eberhard, Simons, and Fennig Citation2021). Since languages are socio-political constructs, in the absence of standard varieties for the vast majority of languages, lects and languages are reified to differing extents, depending on scale and perspective (Goodchild Citation2016, Citation2018; Lüpke Citation2021a). Until recently, sociolinguistic research has focused on Dakar, Ziguinchor and other big cities (Juillard Citation1995; McLaughlin Citation2001; Ngom Citation2003; Dreyfus and Juillard Citation2005; Sall Citation2009; Nunez Citation2015), and only very little data are available on rural multilingualism and small languages. Therefore, the number of named languages provides a particular perspective but should not be expected to capture the full linguistic diversity of this country (or of any other for that matter).

As a typical postcolonial state, Senegal retained the colonial language French as the only official language, thereby forcing monolingual language policies inspired by Global North ethnonationalism upon a population that lives different multilingual realities. It is estimated that over 80% of the Senegalese population are highly proficient in Wolof, an Atlantic language of the Niger-Congo language family, the de-facto most spoken language of Senegal. Only around 20% use French in private settings and are able to read and write it. Despite its quasi monopoly in formal contexts, including formal education, use of French has not increased over time (Swigart Citation2000; RTI International & USAID Citation2015). Wolof spread in the wake of French colonisation and with the postcolonial Northern elites and can be now found all over the country and in neighbouring states. Additional mutually unintelligible languages of wider communication are used regionally (mainly from the Atlantic and Mande families, e.g., Seereer, Pular, Mandinka, Joola) and depending on their origin and mobility, people are frequently able to communicate in several of them (McLaughlin Citation2008). Speakers often count one or several smaller identity languages as part of their repertoires, which could be the mother’s/father’s language of (primary) identity, with the father’s focal identity languagesFootnote1 often taking the status of ethnic language, regardless of actual fluency in this language. Repertoires also often comprise additional languages used by family members and neighbours plus the patrimonial language(s) – the founders’ language(s) – of places lived in. The astonishing array of linguistic repertoires is represented in fluid everyday conversation, where language use is dependent on context and interlocutors (Lüpke Citation2016a; Goodchild Citation2018; Weidl Citation2018; Cobbinah Citation2019).

In addition to the sole official language French, an uncertain number of Senegalese languages have acquired the status of national language. This status relies on prior standardisation and in principle means that they can be used in mother tongue-based bilingual education, university language teaching and media. However, even large languages such as Wolof, Seereer or Pular,Footnote2 which have been equipped with standard forms, remain largely untaught and unused in public institutions and media in written form and therefore, their standardisations are inaccessible to most Senegalese. The only accessible written statement of the Senegalese government concerning the official status of languages is as follows:

La langue officielle de la République du Sénégal est le français. Les langues nationales sont le Diola, le Malinké, le Pular, le Sérère, le Soninké, le Wolof et toute autre langue nationale qui sera codifiée.

[The official language of the Republic of Senegal is French. The national languages are Joola, Mandinka, Pular, Seereer, Soninké Wolof and all the other national languages that will be codified.]

In addition to the official and national languages, Arabic, as the language associated with Islam, adhered to by over 90% of Senegal’s, enjoys a particular prestige in religious settings and in Arabic private schools (Camara and Mitsch Citation1997; Ngom Citation2003, Citation2010; Humery Citation2010). Both Arabic and French are perceived as languages with high prestige and lead to social and economic advantages beyond national borders. These languages dominate writing, both in terms of writing in them and in terms of serving as models for the writing of other languages (Lüpke Citation2018a, Citation2020, Citation2021b; Lüpke and Bao-Diop Citation2014; Lüpke and Watson Citation2020; McLaughlin Citationforthcoming). Their sound-grapheme associations are transferred to the writing of entire repertoires in grassroots literacy practices.

While the bulk of writing in local languages is confined to the informal sphere, some national languages, most noteworthy Wolof (Ndione Citation2021) and Seereer (Darby and Dijkstra Citation2021) are occasionally employed in a selected number of primary schools. This so-called ‘mother tongue- based bilingual education’ (MTBE) is problematic even in the north of Senegal, where repertoires tend to be smaller, but where pupils often do not master their presumed mother tongues (languages dominant in particular areas or particular varieties of language clusters) prior to starting school (Ndione Citation2021). In areas like the Casamance, where many small languages are spoken only by a few hundred speakers, this educational model is inconceivable. Any language selection would exclude high numbers of learners.

The languages used in formal schooling are introduced in their official, codified orthographies. Just like the grassroots literacies (Blommaert Citation2008) that emerged surrounding French, Arabic and Wolof as local languages in Senegal, these orthographies are based on a lead language (Lüpke and Bao-Diop Citation2014) and its spelling norms. In neighbouring countries, however, the same local languages are written based on orthographies of other ex-colonial languages like English or Portuguese, making written mutual intelligibility increasingly difficult and unnecessarily complex. The model for the official alphabet of the languages of Senegal (also used by LILIEMA) is the orthography for Wolof, created by the Senegalese linguist Arame Fall. Apart from the mentioned occasional uses of national languages in MTBE, the Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar offers courses in a small selection of Senegalese languages, which are compulsory for students of linguistics over 1–2 terms. Several NGOs, missionary and faith-based organisations, most prominently SIL International, are active in the codification of and/or creation of educational materials for a number of languages of Senegal, with occasional literacy programmes being delivered for these languages. Faced with the complex multilingual profile of rural Casamance, SIL has recently stopped offering literacy teaching in local languages and has focussed its activities on the linguistically slightly less heterogeneous north of the country (Lüpke Citation2018a).

Because of the linguistic obstacles present in the school context, be it in a French-medium or an MTBE school, pupils’ negative learning experiences lead to low learning outcomes, repetition of school years, high dropout rates and functional illiteracy even for those who manage to attend school beyond the primary cycle (Skattum Citation2020; Juillard Citation2021).

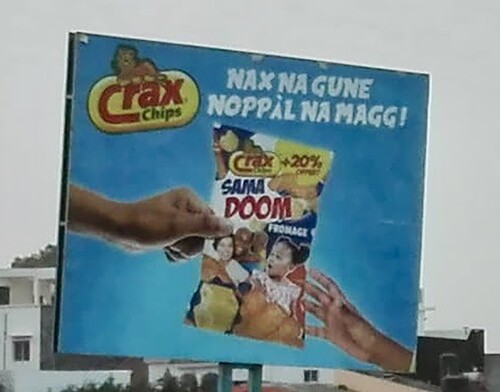

Literacy uses in the linguistic landscape illustrate the multiplicity and fluidity of practices, testifying of the absence of robust standards for Wolof and in extension other languages of Senegal. Consider the advertisements in and :

Both advertisements use Wolof as the main language. In the phrase Nax na gune, noppal na magg! ‘Fools the child, makes things easier for the adults!’ is used to advertise the snack product SAMA DOOM ‘my child’ in the official Wolof orthography, with two French insertions, fromage ‘cheese’ and chips ‘crisps’ in the official French orthography. An alternative would have been to use the phonetically integrated loanword fromas. The brand name CRAX chips is ambivalent (Woolard Citation1998), since the sound symbolic form crax could be read in either French or Wolof orthography, yielding the pronounciation [kRax] in Wolof, and [kRaks] in French. The latter option is used in radio publicity.

The advertisement for Séo, a filtered water in also features Wolof and French but displays French lead-language writing introduced above. The Wolof text is written in French orthography: ndokh mou neekh te oyof ‘water that tastes good and is light’, which would be ndox mu neex te oyof in standard Wolof orthography. The French text bonne & heureuse année 2021 ‘happy new year 2021’, likewise appears in French orthography. Whereas might seem to be more suitable to promote Wolof, is more accessible to those readers who received their education exclusively in French education and have no knowledge of Wolof orthography. However, learners who dropped out of school early seem to comprehend better. This was mentioned to/by the authors and confirmed in a short interview via WhatsApp when these two examples were shown to Senegalese LILIEMA members in February 2021. In social media and texting, grassroots literacy practices coexist with standard-based spellings. Fluid mixing of languages and spelling conventions is widespread, whereas heterography and the use of non-standard variants of languages are often rejected in more normative spaces of writing.

The following section 3 further elaborates the structure of the LILIEMA project, addresses previously mentioned issues to then discuss more of the project’s implementation and data in section 4.

LILIEMA team and courses

LILIEMA encourages people to write and read in the languages they feel most comfortable with and which they use most in their daily lives, which in turn supports the visibility of even small local languages and their use in multilingual constellations. The LILIEMA method was developed based on the team’s transcription experiences and piloted in 2017 with positive results; since then, we successfully expanded culture-specific teaching materials, course syllabi for different levels of learning and trained teachers with various linguistic repertoires. The project regularly organises multilingual courses, cultural days and social gatherings to disseminate and improve the LILIEMA method.

One our strengths is the composition of our team, including members with very different academic, professional, linguistic and cultural backgrounds and experiences spanning Senegal and Europe. Currently, the team consists of ten teachers who are active in different villages, Senegalese and European supervisors, organisers, and researchers. The division of roles is flexible, and a hierarchical system is not in place; especially the position of the teacher imparting multilingual knowledge can be occupied by anybody with relevant knowledge, including course participants.

Differently to many development organisations, who employ staff in cities but work with unpaid volunteers in rural communities, all our team members are either formally employed at universities in Europe or are paid a fair wage. Since 2017, we have successfully taught the LILIEMA method in 7 villages and worked with over 250 learners. During the courses, we encourage speakers to write words and phrases based on LILIEMA as they would express them orally (see examples below).

Currently the LILIEMA courses are organised in two levels comprising 10 units each, without a set number of contact-teaching hours as they are adapted individually to learners’ progress. In general, anybody interested is welcome to take part in our courses. However, we particularly encourage adults who do not practise literacy in their daily lives and people who are interested in learning to read and write all languages in their repertoires to attend. Minors are not excluded; however, we do reflect on their interest to participate LILIEMA courses to avoid interfering with their formal education or overburdening them in case they are still in school. Level 1 is aimed at participants with only little previous exposure to literacy and targets the considerably large yet marginalised group of learners who can write and read letters but do not feel proficient and confident enough in French to use it in a written form, often linked to negative experiences they have had in school.

Level 2 is geared towards more advanced writers or learners and participants who have completed our level 1 course. The groups are small and individual support is offered. A third level that teaches pedagogical skills to graduates of level 2 is envisaged and has the aim to train LILIEMA teachers for new regions, since LILIEMA teachers always teach in language ecologies in which they live and hence need very site-specific language and social skills. Since 2021, LILIEMA offers an online level 2 course via Zoom, which gathers people with Senegalese origin from all over the world. This course has been very positively received so far and results in rapid dissemination and greater reach of the method.

All our courses end with a celebration which local dignitaries as well as invitees of the course members are welcome to join. In a closing ceremony, the participants are awarded an official LILIEMA certificate, provided they have attended 80% of classes, participated actively and reached the learning goals for their level. Additionally, every participant is invited to demonstrate their newly learned skills to the guests and depending on the village, short theatre plays, and lectures are organised. It is encouraging to note that our enrolment data from 2020 show that LILIEMA had a relatively low dropout rate: only about 9% of learners who attended the first session did not complete the course. The high number of regular participants can be ascribed to the rapid learning success in the courses and to the positively reinforcing communal course environments created by our local teachers.

Participatory development of teaching materials and classroom activities

LILIEMA uses its own and individualised teaching materials and exercises aligned with the socio-cultural realities of course participants. These are jointly developed by our team and constantly improved and expanded through experiences and with the input of our participants and members; for instance, we collect phrases and texts that are then used in subsequent teaching sessions. Reading and writing tasks are complemented by listening and speaking exercises with culturally appropriate illustrations. Since the teachers are co-authors of all exercises and activities provided, they are familiar with them or receive pedagogical training prior to the courses. All tasks are designed in a way that is adaptable to the multilingual repertoire of the course participants and without any linguistic restrictions (apart from the obviously limited number of examples on work sheets). To attend a course, no supplies are needed, as the teachers provide printed work sheets, pen and paper, a blackboard and other visual and audio-visual materials. The teachers and students are free to use their entire repetoires in different language modes, ranging from monolingual modes to fluid translangaging ones, matching their spoken linguistic practices. The implementation of free writing practices is effortless and participants report that writing feels more natural and straightforward to them.

In every village, teachers and supervisors engage with learners and local audiences and take up projects that originate from participants’ motivations and literacy needs. In the village of Darsalam for example, this resulted in revising a local calendar printed in Bayot which had previously criticised for ‘the wrong use of their language’ (course participant, 2020). After the words and phrases in the calendar had been revised in a way that was accepted by all LILIEMA participants in Darsalam, it was printed again and distributed to the local community, which in turn generated much interest in LILIEMA. In Sindone, several participants were eager to write texts for the church in local languages, a project that was jointly implemented. In Agnack Grand, a participant advertised the sale of his chickens in several local languages, which motivated others to write various multilingual messages (e.g., ‘keep the streets clean’), resulting in a multilingual hand-written poster project. In Medina, where many women who work as market gardeners joined the course, several classes were used to develop a system for documenting their cultivation strategies, acquisitions, and sales best in local languages. In this village, the teachers realised that there was a need to teach how to use the space on an empty page adequately and how structure, headings and tables can aid a better composition of the text. Following this experience, text composition and layout was added as an exercise task to all our courses.

In 2020, with the outbreak of Covid-19, we had to interrupt our courses. Instead, we used our method and the capacities of the LILIEMA team to contribute to the fight against spread of the virus. Within a short period of time, we were able to develop 12 posters representing the official information on the Corona virus published by the Senegalese government in 12 local languages (with customised mixes of languages for different multilingual language ecologies) in an easily accessible way. Over 2000 posters and leaflets were distributed. We selected strategically important spaces like bus stops and local shops to reach a maximal number of recipients and estimate that we have reached far over 5000 people with our campaign. We chose to provide written health information in our campaign despite the preference for oral media, because many of the villages in the area we cover are not on the electricity grid, so radio and TV are only available on a very limited basis, and because internet access or communication via smart phones is costly and therefore out of reach for many villagers.

To measure the accessibility and impact of our materials independent of the participation in a LILIEMA courses, we conducted quantitative and qualitative surveys with respondents from 16 villages. The survey results confirm the comprehension of the content, the positive impact on peoples’ knowledge and the great relevance of receiving multilingual information. In a multilingual survey that was conducted by LILIEMA teachers and supervisors with over 700 randomly selected participants, 82.1% stated that they read and understood the information on the posters in one or several languages. Out of these survey participants, 99.7% stated that our multilingual Covid-19 health campaign clearly increased their knowledge on the pandemic and prevention measures. Most participants accessed the information in more than one language, often in French out of habit but additionally in a language of identity as long as it was one of the languages they use regularly in their daily lives. Participants elaborated that the possibility to access the same information in various languages was a sufficient way for better comprehension. Overall, the materials enjoyed great popularity and more multilingual information (also on other topics) was requestedFootnote3.

Embeddedness in research

All our teaching activities are informed by and embedded into research. Prior to the implementation of a LILIEMA course, our team visits the location of prospective classes and contacts the village chief, local dignitaries, and leaders in order to receive consent for the running of classes. This visit is also an occasion for the collection of first historical and ethnographic data. LILIEMA courses are flanked by data collection and research. The course participants are aware of our research activities from the outset, and they give explicit consent at the beginning of courses to have their spoken and written multilingual language use and information on their repertoires and trajectories recorded in anonymised fashion. Our research, some of which is presented in section 4, is inscribed into the transdisciplinary field of small-scale multilingualism studies, and our theoretical framework combines central concepts from anthropological linguistics, such as scale, perspective, and fractal recursivity (Irvine and Gal Citation2000; Gal Citation2016; Irvine Citation2016) in a holistic conceptual framework (Goodchild Citation2018; Weidl Citation2018; Lüpke Citation2020). We use qualitative (applied) sociolinguistic research methods allowing the description of fluid and potentially ambivalent multilingual speech events based on different perspectives motivating linguistic choices both in terms of languages ideologies and linguistic practice. The cultural and linguistic knowledge of local participants and ethnographic and qualitative sociolinguistic data jointly contributes to our thick understanding (Geertz Citation1973) of the social environment for literacy. How course participants describe their linguistic repertoires, which writing choices they make and how they categorise different spoken and written forms gives us a deep understanding of multilingual practices and grounds our description in them (Djité Citation2009; Di Carlo, Good, and Diba Citation2019). Without the LILIEMA context, this insight would not be available. We analyse learners’ writing samples which, enhanced by our understanding of the situations and social environments, provide insights into different linguistic environments and literacy strategies employed by teachers and learners. Our exercises also provide a context for discussing participants linguistic ideologies and attitudes. Writing exercises on issues relevant to the learners and socio-cultural context, as well as the discussions around them, show us domains of language associated with specific languages, etc. Through their writing, course participants give us direct access to their conceptualisation of linguistic spaces and the language regimes governing them.

The written data is complemented by ethnographic data collected through classroom observations of a researcher, supervisor, or the teachers and with analyses of video recordings of classroom interactions, provided all attendees’ consent. Furthermore, we conduct in-depth (socio)linguistic and ethnographic data with volunteers among the course participants. The interviewees are free to choose the place and method of data collection. This participant-led approached proved very popular, and more course attendees volunteered to take part than we could accommodate with our capacities.

Our data is analysed in a triangulated fashion, integrating different perspectives, including the views of course participants, LILIEMA teachers and coordinators as well as trained researchers (Goodchild Citation2018; Weidl Citation2018; Goodchild and Weidl Citation2019). All teachers and coordinators contribute at the same time as research assistants and informants as all repertoire users’ feedback on analysis is crucial to gain various interpretations of linguistic practices and helps to get more in-depth insights of fluidity and boundary marking in writing.

LILIEMA: Development and implementation

In the LILIEMA programme, we instrumentalise existing grassroots writing practices as an inspiration for an inclusive multilingual literacy model. The idea for the LILIEMA method developed out of a collaborative research project on small-scale multilingualism in a number of villages in the Casamance. In the project, European and Senegalese researchers and transcribers worked on multilingual data exhibiting great variation. In previous research projects, the researchers had already decided, in consultation with research participants and main transcribers, to use the official alphabet of Senegal for the transcription of language dataFootnote4. The alphabet is adaptable to all Senegalese languages and can be extended if the need arises (see section 4.1). Based on the orthography developed for standard Wolof, this official alphabet of Senegal has provided the sound-grapheme associations for the codification of other languages of Senegal. Thus, it functions already as a lead language literacy, exactly as the widely used grassroots literacies based on French and Arabic in the Latin and Arabic scripts. The innovation in the Crossroads project, the research project from which LILIEMA stems, consisted in using it language-independently and as a transcription system. The alphabet is based on clear and consistent letter-sound correlations and mainly uses basic characters of the Latin alphabet, which makes it easy to read and use, even on electronic devices.

Senegalese Crossroads team members soon began to use the official alphabet of Senegal for personal literacy and commented on the empowerment they felt being able to write their entire repertoire. Thus, the idea of developing an inclusive literacy programme out of Crossroads transcription practices was born. It coincided with two other concerns of the Crossroads project: that of making the research relevant for local research participants and of creating career options for Senegalese project members beyond the duration of the research project. With the LILIEMA programme, we have realised a model for repertoire-based reading and writing that relies on the expertise of local team members and valorises all languages of Casamance, with the potential to add any (Senegalese) language. We created the method in January 2017 at a workshop that brought together members of the Crossroads project and local voluntary teachers and community members. A year of pilot teaching and teaching material development followed (Lüpke et al. Citation2021). In 2018 and 2019, we consolidated the method and decided to create the LILIEMA association dedicated to teaching, training, fundraising and advocacy.

The LILIEMA spelling conventions

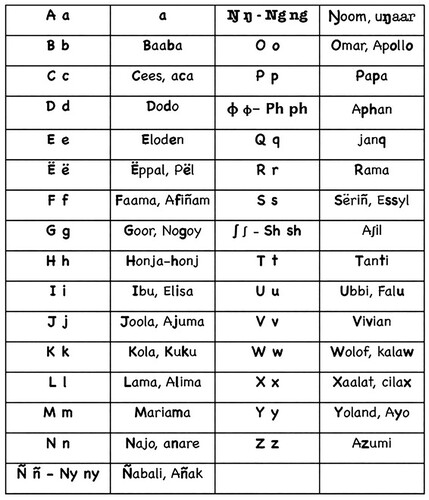

LILIEMA teaching is based on the official alphabet of Senegal but is open to additions and alternative spellings stemming from readers’ and writers’ literacy experiences. shows this alphabet with examples from our courses, where it was so far mainly used for the languages Baïnounk Gubëeher, Baïnounk Gujaher, Bayot, Joola Eegima, Joola Buluf, Joola Fogny, Joola Kujireray, Mandinka, Pular, Seereer and Wolof. In addition to basic characters of the Latin script, the alphabet also contains some special characters such as <ë>[ə], <ñ> [ɲ], and <ŋ> [ŋ]. Upon the request of course participants who are speakers of Bayot, <ɸ> [ɸ] was added. Whereas /ë/ is well-established in Senegal and available on all mobile devices, <ñ>, <ŋ> and <ɸ> are not easy to find on computer and phone keyboards. They are often replaced by writers with the digraphs <ny>, <ng> and <ph>, an alternative that we introduce in LILIEMA classes.

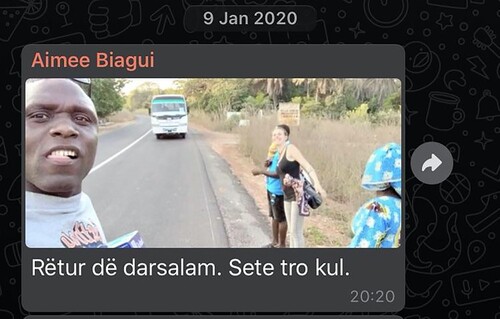

presents a screenshot of a message the teacher and supervisor Aimé Biagui sent to the LILIEMA WhatsApp group to report back after a successful course in the village of Darsalam. His multilingual text illustrates that he decided to use LILIEMA to write French, with an etymologically English word: Rëtur dë dasalam. Sete tro kul ‘Back from Darsalam. It was too cool’. For LILIEMA participants with only basic mainly orally acquired knowledge in French, this text proved to be easier to read during our LILIEMA classes than a text using French as the lead orthography, for example the advertisement in using the French orthography to write Wolof.

Language use in Senegal is characterised by fluid (trans)languaging (Li Wei Citation2018) and inclusion of words which are etymologically Arabic and French (and more recently, also English) with local languages. This phenomenon is variously described as code-switching or borrowing (see e.g. Heath Citation1989; or Auer Citation1999). In particular the status of speech forms of French origin is often ambivalent (Lexander, Lüpke, and Chambers Citation2010; Lexander and López Citationforthcoming; McLaughlin Citation2014; Swigart Citation1992). presents the spelling of potentially ambivalent words during LILIEMA courses; the notations of the participants show varying local phonetic realisations, which are used alongside standardised French/English spellings. The LILIEMA method is accessible to everybody who can read the Latin script. Even participants from The Gambia or Guinea Bissau (where different norms exist) can read LILIEMA texts, although they were educated in English (orthography) or Portuguese (orthography).

Table 1. Variation in participants’ and teachers’ spelling of ambivalent words during LILIEMA courses in 2020.

In LILIEMA teaching, all spelling variations as well as the standard spelling in the language of origin of the lexemes are fully accepted. It is expected that conventions will emerge through shared practice, as observed for digital literacy practices in Africa (Deumert and Lexander Citation2013).

Attitude to variation

One of LILIEMA’s strengths is the acceptance of variation and heterography, as long as it is in accordance with the actual pronunciation of sounds and therefore readable and comprehensible for the participants. There are three main sources of spelling variation: differences in grapheme choices, phonetic variation of speech forms and different established orthographic forms. Examples (1)–(5) below, which feature the greeting ‘peace’ used in many Joola and Baïnounk languages illustrate both types. The diphthong [aɪ̯] is represented with <ai>, as in (1) and (3) or with <ay>, as in (2), (4) and (5), illustrating different graphemic choices. The differences in vowel length and voicedness or voicelessness of the initial consonant reflect variation in pronunciation. In some cases, these differences are enregistered for different Joola languages. In Joola Eegimaa/Banjal, for instance, the velar plosive is realised voiced, as [g], and hence rendered as <g>, in contrast to other Joola varieties where it is realised as voiceless [k], <k> (Bassène Citation2007; Sagna Citation2008). Geminate consonants and vowels are often in complementary distribution in different Joola lects; among our examples, only the long vowel [aː], <aa> is present. Free variation and enregistered variation co-exist, and which forms are known and used to writers depends on their individual repertoire. These instances of variation therefore led to vivid discussions among learners sometimes initially focused on the question which of the variants represents a ‘purer’ Joola. The increased awareness and recognition of variation as part of multilingual language ecologies increased participants’ metalinguistic awareness of local linguistic diversity.

kasumai

kasumay

kaasumai

kasumaay

gasumay

Similar discussions occurred in the village of Darsalam on the use of the bilabial plosive <p> [p], the fricative, labiodental <f> [f] and the voiceless bilabial fricative [ɸ] which apparently stand in free variation in Bayot, a fact that neither the teachers nor the speakers themselves had realised before.

As illustrated in , different orthographic conventions coexist for words which can be categorised as belonging to different languages (Goodchild Citation2018; Weidl Citation2018). This variation also extends to toponyms and personal names, which occur in versions based on French orthography and various other spellings. For example, the name <Boubacar Diallo> would correspond to <Bubaka Jallo> in the official alphabet; similarly, the spelling of the village <Niaguiss> would change to <Ñagis>. Participants were very aware of the different contexts in which the different spellings could be used, with French orthographic forms required in official contexts, for example when filling in a form. In their personal writing practice, participants use orthographies in a mixed fashion. For example, in 2021, a shopkeeper who attended the LILIEMA courses used French and LILIEMA orthography for his inventory lists, depending on his etymological knowledge, categorisation of the word and familiarity with other orthographic forms.

LILIEMA in application

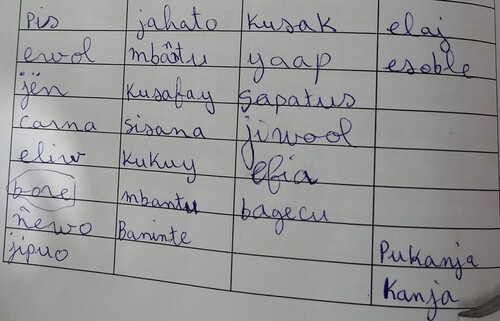

The following example of a shopping list compiled during a LILIEMA course, gives an insight into uses of literacy created by our learners ().

The author (P12dar) of this document is female, highly multilingual and was at the time of the recording in her early 30s. In an interview she reported Joola Kasa to be her language of identity; however, within her family and close environment she also regularly speaks other Joola languages and Joola FognyFootnote5 when she sells crops. Through regional travelling and working experiences she also acquired Wolof and a Portuguese based Creole in the border regions to Guinea Bissau and in Guinea Bissau. Additionally she speaks Mandinka, which she learned from friends. P12dar mentioned that she attended school for some years but had to drop out and look after younger relatives and help with farm work. She does not report French in her repertoire and did not use literacy actively in her personal life after leaving school, apart from operating her mobile phone (mainly saving contacts) or reading destinations on buses and isolated words on advertisements.

In this task, she chose to write a shopping list in several of the languages that are part of her linguistic repertoires. According to her own report some of the items listed are repeated in different languages such as ‘meat’ (Creole: carna; Joola Fogny: eliw; Mandinka: ñewo; Bayot: efia; Wolof: yaap) or fish (Creole: pis; Joola Kasa: ewol; Wolof: jën; Bayot: jipuo; Foola Fogny: jiiwol). Others are mentioned once, such as jahato ‘bitter aubergine’ in Wolof or bagecu ‘guinea sorrel’, which she classifies as Bayot. In fact, many of the words in question are potentially polyvalent or occur in closely related forms in other languages of the area. That P12dar categorises the form bagecu as Bayot illustrates that her categorisation of language is based on her personal repertoire and thus a question of perspective, since the word also occurs in Baïnounk languages and might thus be categorised as such as well. The lexeme bore which was encircled by P12dar, signalling the special status this item has for her. The word refers to leek (poireau in French) which she spelled phonetically. P12dar seems to be aware of the existence of a standard spelling but does not use it, perhaps because she does not know it. Spelling convention can differ even within the same language based on the existence of different spelling options: the velar plosive [k] was written as <k> following the LILIEMA sound-grapheme associations several times, but also represented with <c> in carna, influenced by the official Portuguese orthography. These variations are accepted and explained in our courses and all the other participants and course teachers were able to read what the author was writing.

A method adapted to local language ecologies and to language-based and (trans)languaging regimes of writing

Because of its tolerance of variation, LILIEMA fully integrates all speakers and repertoires. Our programme retains the adaptability and fluidity of existing grassroots literacy practices and supports both language-based and (trans)languaging writing practices. Besides thickly multilingual exchanges on social media (Lexander Citation2010; Lexander & López, Citationforthcoming) which constitute a translanguaging space, most writers also adhere to language-based ideas of literacy and report to either write in French or Arabic or not at all, since they feel that their fluid and non-standard written language use, often interpreted as ‘incorrect’, is not worth mentioning. Language-based literacy for other languages, which is sometimes offered to adults (see section 2), is in principle welcomed because of its cultural relevance but hardly ever taken up. For one, writing local languages is seen as interfering with the writing of French. This perception reflects teaching methods and language ideologies conveyed from preschool onwards, where the use of local languages is often officially still prohibited or discouraged. Since the general perceptions of local languages being less useful than European languages prevail, efforts in writing then seem pointless. Additionally, in the Casamance area, as in many other regions of Senegal, active literacy use is not an integral part of peoples’ daily lives; books are rare and in most of the villages where LILIEMA is active, print media are not easily available. In a survey conducted in 2020 we found that radio and television are the most popular media in places with access to the electricity grid. The preference for oral media also holds online: our observations are that people would rather listen to an audio file or watch a video than read an article, an observation also supported by the dominance of video media in the biggest Senegalese online platforms such as senenews.com or seneweb.com.

To summarise, language-based literacy is focused on large and prestigious languages, lending confidence and spaces to practise their skills to readers and writers proficient in French or Arabic. In particular for French, proficiency in spoken and written standard French is positively correlated with trust in one’s reading and writing skills, whereas people who have some knowledge of French and literacy, but do not self-assess as proficient enough tend to just give up on reading and writing. For most, literacy is inextricably linked to a high level of ‘correct, standard’ of metropolitan French, triggered by the post-colonial realities in a country where French holds exclusive (and elusive) cultural capital. Through LILIEMA, we cannot change socioeconomic realities. We can, however, take inspiration from the grassroots literacies that have been developed by readers and writers themselves for exactly these literacy contexts. Where there is no space for the development of robust language-based literacy skills for most languages, either because these languages are marginalised and invisibilised or because they have very low speaker numbers, West African writers have responded by creating lead-language literacies (Souag Citation2010; Lüpke and Bao-Diop Citation2014) that create transferrable literacy skills and do not rely on standardisation or language-specific sound-grapheme association rules. By basing LILIEMA on this literacy model, yet also welcoming spellings associated with other literacy regimes, we overcome the above-mentioned obstacles to literacy though empowerment of multilingual speakers and collective learning and teaching practices that are inclusive, flexible and open. Since writers do not need to rely on language selection, externally set standards or teaching materials developed elsewhere, they are empowered to self-reinforce their literacy and spread it through their usage. This turns LILIEMA into a sustainable programme that does not require constant external intervention.

Conclusion: LILIEMA: more than a literacy programme

LILIEMA pursues several objectives: first and foremost, the programme creates, supports, and enhances personal (multilingual) literacy, strengthens linguistic awareness, fosters self-confidence of marginalised learners and creates spaces for the writing of small and locally confined languages. This empowerment contributes to a greater visibility and valorisation of African languages as they are practised by multilingual individuals, thus raising status and prestige of multilingual practice in ways that are desired by the speakers themselves.

Additionally, LILIEMA courses are important sources of linguistic and ethnographic data that contribute to a better understanding of the linguistic constellations in the areas where we work, of patterns of multilingualism and of multilingual writing and education.

One of the major criticisms our project has faced so far, not by learners and team members, but by outsiders engaged in literacy work is that it is not based on literacy in particular languages and on standard representations of forms, arguably creating confusion and written forms that cannot be widely read. However, our preliminary observations align with Deumert and Lexander’s (Citation2013) findings in their work on multilingual texting performance in Africa: if enough people use a (multilingual) literacy practice, then social surroundings and interactions will naturally set conventions and rules for socially appropriate styles established in and acquired through networks.

Every kind of support for local Senegalese languages, including standard-based projects to promote languages of wider communication, are desirable in our view. However, it is widely accepted by socio- and applied linguists (Ouane and Glanz Citation2010; Heugh Citation2015; Makalela Citation2015; Lüpke Citation2018a, Citation2018c, Citation2020, Citation2021a) that the implementation of language- and literacy programmes in multilingual areas where standard varieties are not widely spoken (Anderson and Ansah Citation2015; Barasa Citation2015) generate multiple problems, ranging from excluding the vast majority of learners and teaching them in forms of language that are alienating and result in the invisibility of full lived practice.

While embedded in a (trans)languaging vision, LILIEMA is complementary to language-focused and standard-based programmes. We believe that these programmes can have important functions in formal, standard-based spaces but crucially need to be flanked by truly inclusive programmes such as LILIEMA in order to avoid marginalisation and minoritisation of large parts of the population of multilingual places. For most of the locally confined languages that turn Africa into a hotspot of linguistic diversity, official standards have not been established and if they were, they would result in the destruction of exactly the linguistic variation that makes these languages important markers of identity and gives them the important role in speakers’ social lives that motivates them to uphold small-scale multilingual repertoires. But even if there were to be a standard variety, grammar and dictionary developed for each language in small-scale multilingual speakers’ repertoire, what would be their interest in putting in the effort into acquiring all of them? Multilinguals’ literacy needs are varied and hugely different from literacy in the standard language cultures in the ethnolinguistic nation states of the Global North, yet too often, these models are taken as the global model for literacy. At the same time, established standard literacies play important roles for language-focused identities, and therefore need to be acknowledged as well.

Our experiences show that people who are often classified as illiterate or doubt their own literacy skills turn into confident readers and writers in a huge number of languages after a few weeks of LILIEMA training. This positive experience of learners who have been traumatised by the formal school context and who have never seen any positive educational value associated with the languages that have the most affective roles in their lives results in a substantial positive transformation, as many of our formerly non-writing participants acknowledge. This validation of local knowledge and local languages has reached a wide range of people, even if they did not attend LILIEMA training but have witnessed our courses, the Covid-19 health campaign, have seen our multilingual materials or have been told about the method by learners.

By boosting diverse multilingual literacy practices and nurturing local small-scale language ecologies, the LILIEMA project covers the actual literacy needs of local, often marginalised, individuals, while not excluding anybody who would like to be part of it. Without local team members who contribute their unparalleled linguistic and cultural knowledge, LILIEMA would not exist. As such, speakers, readers, and writers of small languages are valorised from the outset, through being recognised as paid experts rather than as beneficiaries of external development initiatives. Our Senegalese teachers and supervisors guarantee that materials, interactions, and teaching strategies are culturally and linguistically appropriate. Simultaneously, LILIEMA enables the collection of rich and nuanced ethnographic data, with active involvement and under leadership of local research participants. Thereby even the smallest locally confined languages become more visible and respected. LILIEMA empowers all participants through fostering equitable exchange, valorising all language practices and using them for the sustainable sharing of and dissemination of knowledge in a truly virtuous cycle.

Notes

1 Primary ethnic and linguistic identity are generally based on patrilineal descent. However, knowledge of the affiliated culture and/or language are not an absolute necessity (see also Weidl Citation2018, 303).

2 Language names are given in their English versions but names do vary widely in local interpretations and appellations.

3 For more information on our Covid-19 campaign see https://liliema.com/liliema-covid-19-campaign/.

4 These projects were the VW Foundation DoBeS grant project “Pots, plants and people – a documentation of Baïnounk knowledges systems” led by author Friederike Lüpke, with Alexander Cobbinah, as PhD researchers and an ELDP pilot grant and AHRC doctoral fellowship held by Rachel Watson. Both later joined Crossroads project “At the Crossroads – investigating the unexplored side of multilingualism” funded by the Leverhulme trust and led by Friederike Lüpke. Author Miriam Weidl joined the research team at the beginning of the Crossroads project. In these projects, the European researchers worked with transcribers and community researchers, among them the authors or the present paper Alpha Mané, the former president of the LILIEMA association who sadly deceased in 2021, and Jérémi Sagna.

5 Joola languages are mutually intelligible to different degrees, the allocation of speakers or lexemes to one Joola language is often a matter of scale and perspective.

References

- Anderson, J. A., and G. N. Ansah. 2015. “A Sociolinguistic Mosaic of West Africa: Challenges and Prospects.” In Globalising Sociolinguistics. Challenging and Expanding Theory, edited by D. Smakman, and P. Heinrich, 54–65. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Auer, P. 1999. “From Codeswitching via Language Mixing to Fused Lects: Toward a Dynamic Typology of Bilingual Speech.” International Journal of Bilingualism, 3: 309–332.

- Barasa, S. N. 2015. “Ala! Kumbe? “Oh my! Ist it So?”: Multilingualism Controversies in East Africa.” In Globalising Sociolinguistics. Challenging and Expanding Theory, edited by D. Smakman, and P. Heinrich, 39–65. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Bassène, A.-C. 2007. Morphosyntaxe du joola banjal. Langue atlantique du Senegal. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.

- Blommaert, J. 2008. Grassroots Literacy: Writing, Identity and Voice in Central Africa. London: Routledge.

- Blommaert, J., and B. Rampton. 2011. “Language and Superdiversity.” Diversities 13 (2): 1–22.

- Brooks, G. 1993. Landlords and Strangers: Ecology, Society, and Trade in Western Africa, 1000–1630. Boulder/San Francisco: Westview Press (African states and societies in history).

- Camara, S., and R. H. Mitsch. 1997. “Ajami Literature in Senegal: The Example of Seriin Muusaa Ka, Poet and Biographer.” Research in African Literatures 28 (3): 163–182.

- Cobbinah, A. Y. 2010. “The Casamance as an Area of Intense Language Contact: The Case of Baïnounk Gubaher.” Journal of Language Contact. Evolution of Languages, Contact and Discourse 3 (1): 175–201.

- Cobbinah, A. Y. 2019. “An Ecological Approach to Ethnic Identity and Language Dynamics in a Multilingual Area (Lower Casamance, Senegal).” In African MultilingualismS. Selected Proceedings from the International Conference, Yaounde 12 August 2017, edited by J. Good, and P. Di Carlo, 71–105. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Cobbinah, A. Y., A. Hantgan, F. Lüpke, and R. Watson. 2016. “Carrefour des Langues, carrefour des paradigmes.” Espaces, Mobilités et Éducation Plurilingues: Éclairages d’Afrique Ou d’ailleurs, 79–96.

- Darby, C., and J. Dijkstra. 2021. “Applying Theory Successfully: The Early Impact of L1 Instruction on L2 Literacy Confirms Cummins’ Interdependence Hypothesis in Senegalese Primary Schools.” In Language and the Sustainable Development Goals. Selected Papers from the 12th Language and Development Conference. 12th Language and Development Conference, November 27–29 2017, edited by P. Harding-Esch, and H. Coleman, 79–87. Dakar: The British Council.

- Deumert, A., and K. V. Lexander. 2013. “Texting Africa: Writing as Performance.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 17 (4): 522–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12043.

- Diallo, I. 2009. “Attitudes Toward Speech Communities in Senegal: A Cross-sectional Study.” Nordic Journal of African Studies 18 (3): 196–214.

- Di Carlo, P., J. Good, and R. O. Diba. 2019. “Multilingualism in Rural Africa.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics: 1–47.

- Djité, P. G. 2008. The Sociolinguistics of Development in Africa. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters (Multilingual matters, 139).

- Djité, P. 2009. “Multilingualism: The Case for a New Research Focus.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2009: 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJSL.2009.032.

- Dreyfus, M., and C. Juillard. 2005. Le plurilinguisme au Sénégal. Langues et identités en devenir. Paris: Karthala.

- Eberhard, D. M., G. F. Simons, and C. D. Fennig. 2021. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Twenty-fourth Edition. Dallas, TX: SIL International. http://www.ethnologue.com.

- Evans, N. 2018. “Did Language Evolve in Multilingual Settings?” Biology & Philosophy 32 (2): 905–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-018-9609-3.

- Gal, S. 2016. “Scale-Making: Comparison and Perspective as Ideological Projects.” In Scale: Discourse and Dimensions of Social Life, edited by S. E. Carr, and M. Lempert, 91–112. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Garcia, O., and Li Wei. 2014. Translanguaging. Language, Bilingualism and Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Geertz, C. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

- Goodchild, S. 2016. ““Which Language(s) are You for?” “I am for All the Languages.” Reflections on Breaking through the Ancestral Code: Trials of Sociolinguistic Documentation.” SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics 18: 75–91.

- Goodchild, S. 2018. “Sociolinguistic Spaces and Multilingualism: Practices and Perceptions in Essyl, Senegal.” SOAS, University of London PhD.

- Goodchild, S., and M. Weidl. 2019. “Translanguaging Practices in the Casamance. Senegal Similar but Different: Two Case Studies.” In Making Signs, Translanguaging Ethnographies: Exploring Urban, Rural, and Educational Spaces, edited by A. Sherris, and E. Adami, 133–151. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Green, T. 2019. A Fistful of Shells. West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution. London: Allen Lane.

- Heath, J. 1989. “From Code-switching to Borrowing: Foreign and Diglossic Mixing in Moroccan Arabic.” Library of Arabic Linguistics: 326–328.

- Heugh, K. 2015. “Epistemologies in Multilingual Education: Translanguaging and Genre – Companions in Conversation with Policy and Practice.” Language and Education 29 (3): 280–285.

- Humery, M.-E. 2010. “Multilinguisme et plurigraphie dans le Fuuta Sénégalais: quelques outils d’analyse.” Journal of Language Contact, THEMA 3: 205–227.

- Irvine, J. T. 2016. “Going Upscale: Scales and Scale Climbing as Ideological Projects.” In Scale: Discourse and Dimensions of Social Life, edited by S. E. Carr, and M. Lempert, 213–233. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Irvine, J. T., and S. Gal. 2000. “Language Ideology and Linguistic Differention.” In Language Ideology and Linguistic Differentiation, 35–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- Juillard, C. 1995. Sociolinguistique urbaine. La vie des langues à Ziguinchor (Sé- négal). Paris: Presses du CNRS.

- Juillard, C. 2021. “The impact of Senegalese primary school teachers’ trajectories and language profiles on bilingual education.” In Language and the Sustainable Development Goals. Selected Papers from the 12th Language and Development Conference. 12th Language and Development Conference, November 27–29 2017, edited by P. Harding-Esch, and H. Coleman, 107–114. Dakar: The British Council.

- Léglise, I. 2017. “Multilinguisme et hétérogénéité des pratiques langagières. Nouveaux chantiers et enjeux du Global South.” Langage et Société N° 160-161: 251–266.

- Lexander, K. V. 2010. Pratiques plurilingues de l’écrit électronique : alternances codiques et choix de langue dans les SMS, les courriels et les conversations de la messagerie instantanée des étudiants de Dakar, Sénégal. University of Oslo: PhD Thesis.

- Lexander, K. V., and D. A. López. forthcoming. “Digital Language and New Configurations of Multilingualism: Language Use in a Senegal-based Discussion Forum.” In Oxford Guide to the World’s Languages: Atlantic, edited by F. Lüpke, 1–37. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lexander, K. V., Lüpke, F., & Chambers, M. (2010). Vœux électroniques plurilingues : nouvelles pratiques, nouvelles fonctions pour les langues africaines ? Journal of Language Contact 3: 228–246.

- Lüpke, F. 2004. “Language Planning in West Africa – Who Writes the Script?” Language Documentation and Description 2 (January 2004): 90–107.

- Lüpke, F. 2016a. “Pure Fiction – The Interplay of Indexical and Essentialist Language Ideologies and Heterogeneous Practices A View from Agnack.” African Language Documentation: New Data, Methods and Approaches 10 (10): 8–39.

- Lüpke, F. 2016b. “Uncovering Small-scale Multilingualism.” Critical Multilingualism Studies 4 (2): 35–74.

- Lüpke, F. 2018a. “Escaping the Tyranny of Writing. West African Regimes of Writing as a Model for Multilingual Literacy.” In The Tyranny of Writing Revisited. Ideologies of the Written Word, edited by K. Juffermans, and C. Weth, 129–148. London: Bloomsbury.

- Lüpke, F. 2018b. “Multiple Choice: Language Use and Cultural Practice in Rural Casamance between Convergence and Divergence.” In Creolization and Pidginization in Contexts of Postcolonial Diversity, edited by J. Knörr, and W. T. Filho, 181–208. Leiden: Brill.

- Lüpke, F. 2018c. “Supporting Vital Repertoires, not Revitalizing Languages.” In The Routledge Handbook of Language Revitalization, edited by L. Hinton, L. Huss, and G. Roche, 473–484. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lüpke, F. 2020. “The Writing’s on the Wall: Spaces for Language-independent and Language-based Literacies.” International Journal of Multilingualism 17 (3): 382–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2020.1766466.

- Lüpke, F. 2021a. “Patterns and Perspectives Shape Perception: Epistemological and Methodological Reflections on the Study of Small-scale Multilingualism.” International Journal of Bilingualism 25 (4): 878–900.

- Lüpke, F. 2021b. “Standardization in Highly Multilingual Contexts: The Shifting Interpretations, Limited Reach, and Great Symbolic Power of Ethnonationalist Visions.” The Cambridge Handbook of Standard Languages: 139–169.

- Lüpke, F., and S. Bao-Diop. 2014. “Beneath the Surface? Contemporary Ajami Writing in West Africa, Exemplified through Wolofal.” In African Literacies: Ideologies, Scripts, Education, edited by K. Juffermans, Y. M. Asfaha, and A. Abdelhay, 86–114. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Lüpke, F., A. C. Biagui, L. Biai, J. Diatta, A. N. Mané, J. F. Sagna, and M. Weidl. 2021. “LILIEMA: Language-independent Literacies for Inclusive Education in Multilingual Areas.” In Language and the Sustainable Development Goals. Selected Papers from the 12th Language and Development Conference. 12th Language and Development Conference, edited by P. Harding-Esch, and H. Coleman, 79–87. Dakar: The British Council.

- Lüpke, F., and R. Watson. 2020. “Language Contact in West Africa.” In The Routledge Handbook of Language contact, edited by E. Adamou, and Y. Matras, 528–549. London: Routledge.

- Makalela, L. 2015. “Moving Out of Linguistic Boxes: The Effects of Translanguaging Strategies for Multilingual Classrooms.” Language and Education 29 (3): 200–217.

- McLaughlin, F. forthcoming. “Ajami Writing Practices in Atlatantic-speaking Africa.” In The Oxford Guide to the Atlantic Languages of West Africa, edited by F. Lüpke, 1–30. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McLaughlin, F. 2001. “Dakar Wolof and the Configuration of an Urban Identity.” Journal of African Cultural Studies 14: 153–172.

- McLaughlin, F. 2008. “Senegal: The Emergence of a National Lingua Franca.” In Language and National Identity in Africa, edited by A. Simpson, 79–98. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McLaughlin, F. 2014. “Senegalese Digital Repertoires in Superdiversity: A Case Study from Seneweb.” Discourse, Context and Media 4-5 (4): 29–37.

- Mufwene, S. S. 2021. “Linguistic Diversity, Formal Education and Economic Development: The Sub-Saharan African Chicken-and-egg Dilemma?” In Language and the Sustainable Development Goals. Selected Papers from the 12th Language and Development Conference. 12th Language and Development Conference. November 27–29 2017, edited by Philip Harding-Esch, and H. Coleman, 153–164. Dakar, NI: The British Council.

- Ndhlovu, F., and L. Makalela. 2021. Decolonising Multilingualism in Africa. Recentering Silenced Voices from the Global South. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Ndione, A. 2021. “Introducing Wolof in Senegalese Schools: A Case Study.” In Language and the Sustainable Development Goals. Selected Papers from the 12th Language and Development Conference, November 27–29 2017, edited by Philip Harding-Esch, and H. Coleman, 97–106. Dakar: The British Council.

- Ngom, F. 2003. Wolof. Languages of the World. Muenchen: LINCOM.

- Ngom, F. 2010. “Ajami Scripts in the Senegalese Speech Community.” Journal of Islamic and Arabic Studies 10 (1): 1–23.

- Nunez, J.-F. 2015. L’alternance entre créole afro-portugais de Casamance, français et wolof au Sénégal : une contribution trilingue à l’étude du contact de langues. Paris: INALCO.

- Ouane, A., and C. Glanz. 2010. Why and How Africa Should Invest in African Languages and Multilingual Education. An Evidence- and Practice-based Policy Advocacy Brief. Hamburg: UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning.

- RTI International, & USAID. 2015. Report on Language of Instruction in Senegal (19).

- Sagna, S. 2008. Formal and Semantic Properties of the Gújjolaay Eegimaa: (A.k.a Banjal) Nominal Classification System. SOAS, University of London PhD, London.

- Sall, A. O. 2009. “Multilinguism, Linguistic Policy, and Endangered Languages in Senegal.” Journal of Multicultural Discourses 4 (3): 313–330.

- Singer, R., and S. Harris. 2016. “What Practices and Ideologies Support Small-scale Multilingualism? A Case Study of Warruwi Community, Northern Australia.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 204: 163–208.

- Skattum, I. 2020. “Language and Education.” In Handbook of African Languages, edited by R. Vossen, and G. Dimmendaal, 1–39. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Souag, L. 2010. “Ajami in West Africa.” Afrikanistik Online 1–11. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/13429/.

- Swigart, L. 1992. “Two Codes or One? The Insiders’ View and the Description of Codeswitching in Dakar.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 13 (1–2): 83–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.1992.9994485.

- Swigart, L. 2000. “The Limits of Legitimacy: Language Ideology and Shift in Contemporary Senegal.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 10 (1): 90–130.

- UNESCO. 2016. Global Monitoring Report. Education for People and Planet: Creating Sustainable Futures for All. Paris: UNESCO.

- Wei, Li. 2018. “Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language.” Applied Linguistics 39 (1): 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx039.

- Weidl, M. 2018. The Role of Wolof in Multilingual Conversations in the Casamance: Fluidity of Linguistic Repertoires. SOAS, University of London, PhD.

- Weidl, M. 2022. “Which Multilingualism Do You Speak? Translanguaging as an Integral Part of Individuals’ Lives in the Casamance, Senegal.” Journal of the British Academy. Rethinking Multilingualism: Education, Policy and Practice in Africa 10 (2): 41–67. https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/010s4.041.

- Woolard, K. A. (1998). Simultaneity and bivalency as strategies in bilingualism. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 8: 3–29.