ABSTRACT

This paper engages with the negotiation of insider and outsider researcher identities in the context of Welsh-English bilingualism in Wales. It aims to develop a reflexive approach to researching bilingualism, foregrounding the actions and experiences of doing bilingual research in a minority language context. Taking data from education and business as our starting point, we present two self-reflexive accounts of how our research identities, specifically our language profiles, (as an L1 British English speaker and an LX English user, both of whom have only limited understanding of Welsh), and positionalities are questioned, (de)legitimised and assessed in our research projects. In light of this, we reflect also on the methodological consequences and decisions that were taken during the research process. Taken together, these two reflective perspectives allow us to generate new theoretical, methodical and analytic understandings of language within the bilingual Welsh-English context specifically and researcher reflexivity more broadly.

Trafoda'r papur hwn hunaniaethau mewnol ac allanol ymchwilwyr yng nghyd-destun dwyieithrwydd Cymraeg-Saesneg yng Nghymru. Ei nod yw datblygu dull adfyfyriol o ymchwilio i ddwyieithrwydd, gan adeiladau ar gamau gweithredu a’r profiadau o wneud ymchwil dwyieithog mewn cyd-destun ieithoedd lleiafrifol. Gan gymryd data o addysg a busnes fel ein man cychwyn, rydym yn cyflwyno dau ddadansoddiad hunan-fyfyriol ar y ffordd y mae ein hunaniaethau ymchwil, ac yn benodol ein proffiliau iaith (fel siaradwr Saesneg Prydeinig iaith gyntaf a siaradwr Saesneg fel iaith ychwanegol; y ddwy ohonom â dealltwriaeth gyfyngedig yn unig o’r Gymraeg) a safleoldeb [positionality] yn cael eu cwestiynu, eu (dad)gyfreithloni a'u hasesu yn ein prosiectau ymchwil. Yn sgil hyn, rydym hefyd yn myfyrio ar y canlyniadau methodolegol a'r penderfyniadau a wnaethpwyd yn ystod y broses ymchwil. Gyda’i gilydd, mae’r ddau safbwynt adfyfyriol hyn yn ein galluogi i greu dealltwriaeth ddamcaniaethol, drefnus a dadansoddol newydd am iaith o fewn y cyd-destun dwyieithog Cymraeg-Saesneg yn benodol, ac adweithedd ymchwilwyr yn arbennig.

GEIRIAU ALLWEDDOL:

Introduction

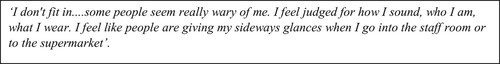

This researcher vignette (Creese, Takhi, and Blackledge Citation2016) captures a moment at the start of Charlotte's PhD (see section researcher positionality for further detail). It highlights the uncertainty and the discomfort felt by a new and inexperienced researcher carrying out ethnographic research in the context of bilingual Wales .

Here, we engage with the negotiation of insider/outsider researcher identities in the context of bilingual Wales. We present self-reflexive accounts of our research experiences with two distinct, yet familiar, projects conducted in Wales, one in the field of education and another in the field of business.Footnote1 Our point of departure for this inquiry is that research is an experience and a mutual dialogue between the researcher and participants and that reflexivity is not just an additional contextual level in research but rather a dialectical, transformative process between the researcher and the participants (see section theoretical premises for an account of how reflexivity is conceptualised in this paper). Taking the lens of reflexivity (see Day Citation2012 for ‘reflective lens’ in qualitative research), we argue that a reflexive approach generates questions concerning the motivation for research, as well as its research design and methods, the data collection, analysis, interpretation and presentation. It allows for a richer understanding of complex social phenomena such as bilingualism in minority language contexts and debates over the legitimacy, value and challenges of language and insider/outsiderness in research practice. Until recently, too little attention has been paid to auto-biographical reflexive approaches in research methodology in the context of minority languages. We wish to address this paucity of research.

The epistemological premise of this article is grounded in a critical-sociolinguistic understanding of language in society (e.g. Blackledge and Creese Citation2010; Heller Citation2002) and the reflexive turn in (critical) applied linguistics that calls for the need to systematically and coherently explore reflexivity in researching language and society (e.g. Clark and Dervin Citation2014; De Costa Citation2014; Sarangi and Candlin Citation2003; Pérez-Milans Citation2017; Plöger and Barakos Citation2021; Sharma Citation2021). Following Freeman et al. (Citation2007, 27), we consider the role of researchers as one that is ‘always positioned culturally, historically, and theoretically’. So, it is to these positionalities in the bilingual context of Wales to which we would like to turn here. Accordingly, we address the following questions relevant to the context of our two projects:

What social identities do we as researchers and our participants occupy and in what way do these affect how our studies were conducted and perceived?

How are we as researchers constructed by our study participants?

In what ways are our research identities questioned, evaluated and criticized?

In putting such questions up for debate, we hope that a window can be provided as to who we are as researchers, how our identity is connected with the object of analysis, and what implications this has on the research process and outcome. On the one hand, this window may allow others to better understand our own situated research practices and the specific findings produced; on the other, it may provide an avenue for other researchers to highlight the importance of critically interrogating one’s own positionality and its consequences for any type of sociolinguistic inquiry. With this knowledge, we argue that study findings can be better understood in the context of who has produced and co-produced them, under which circumstances and to which ends. It also provides an insight into how the research process has been received and experienced by the study participants.

Theoretical premises

Reflexivity

In the sociology of knowledge, reflexivity has been discussed from a theoretical standpoint as socially determined self-awareness through which the individual determines their actions. In Archer’s (Citation2012) or Giddens’ (Citation1984) work, for example, attention is paid to people’s local practices as embedded in broader processes of social change, that is, as caught up between structure and agency. With the so-called reflexive turn in the humanities, the research process and the ‘researcher self’ have gained momentum. This reflexive turn highlights the need to systematically and coherently explore reflexivity in researching language in society and attendant dimensions of power, positionality, and legitimation in terms of the researcher self, the participants and the process, as the bulk of critical applied and sociolinguistic scholarship demonstrates (e.g. Blackledge and Creese Citation2010; Clark and Dervin Citation2014; Giampapa and Lamoureux Citation2011; Norton and Early Citation2011; Pérez-Milans Citation2017).

Pérez-Milans (Citation2017) argues that perspectives from social theory, and in particular meta-pragmatics, do not only bring reflexivity into dialogue with the research process and the researcher self but also open up the possibility to move beyond the traditional ‘researcher-centred angle to reflexivity’ (Pérez-Milans Citation2017, 5) and to consider the mutually constitutive and discursive relation between actions and the social conditions in which these are embedded. Plöger and Barakos (Citation2021, 4) also foreground the social element in debates over reflexivity and argue that ‘reflexivity includes self-reflection but also social reflection’.

How, then, do researchers position themselves? How are others positioned? How are researchers positioned by others? Such questions raise broader concerns over language, identity and power that condition the research process and its outcome, as discussed by Giampapa and Lamoureux (Citation2011, 127) and by Day (Citation2012, 60) who relates reflexivity to ‘complex issues of power, knowledge production and subjectivity’. In terms of the researcher self, Heller, Pietikäinen, and Pujolar (Citation2018, 10) further emphasise that ‘[r]eflexivity requires that we be the first to examine and explain the position from which we speak both as social scientists and as persons of our times and places and histories’. Based on these premises, we treat reflexivity not as a mere additional contextual level that is assumed but rather as a dialectical, transformative process between the researcher and the research subjects (Barakos and Selleck Citation2018). Research is an experience and dialogue that requires critical (auto-)reflection in research theory and practice. We need to ask not only what matters to our participants and audiences but also what matters to us. Why did we conduct our research the way we did, with which consequences and effects? How do we position ourselves and how are we positioned to ask and answer questions via our research methods, our own trajectories and linguistic repertoires as well as our social relationship with study participants? Such questions lead us to problematise our own insider/outsider roles and locations in the field.

Insider/outsiderness

Sociologists have long debated the merits and payoffs of field research conducted by both outsiders and insiders (see Merton Citation1972; Zinn Citation1979) where insiderness is taken to mean a shared cultural, linguistic, ethnic, national and religious heritage. However, as early as the 1960s, a critique of these roles has developed, at least in part, from a greater awareness of ‘situational identities and to the perception of relative power’ (Angrosino Citation2005, 734). Junker (Citation1960), Spradley (Citation1980), Corbin-Dwyer and Buckle (Citation2009) and others, problematise the strict dualism between an insider and an outsider, and question this over-simplistic distinction. Can you ever be fully participatory? Or a complete insider? If possible, is this desirable? In many respects, the role of a researcher is a paradoxical one; apparently needing to be an insider to gain depth and breadth of understanding whilst simultaneously needing to remain objective and analytical (and in this sense be an outsider) – with these positioned as mutually exclusive. Mullings (Citation1999) took this debate further, questioning the fixed and static positioning given to researchers in the field, arguing that researchers can be ‘insiders, outsiders, both and neither’ (Mullings Citation1999, 337). Corbin-Dwyer and Buckle (Citation2009) explore the notion of the space between (the insider/outsider positions) in that it allows, they argue, researchers to occupy the position of both insider and outsider rather than insider or outsider. They claim that the only position researchers should occupy is this space between. As researchers we cannot separate ourselves from our research and from those involved in it. The experiences of the participants are carried with us, and their words can have a lasting impact. Consequently, there is a certain intimacy to the research process – we cannot be complete outsiders but equally, as researchers, we cannot qualify as complete insiders. We therefore occupy a space between.

What this all misses, however, is the inherent ‘fluidity of the fieldwork roles’ (Bruskin Citation2019, 162). Researcher identity is a product of social interaction grounded in specific contexts and at specific moments in time. How the researcher is positioned is therefore emergent and fluid. Researcher identity is not always pre-determined a priori, based on a pre-existing sense of who they are or the organisation that they represent. Rather, the context and interactions with research participants can also shape the researcher and those who are researched. Therefore, it is the perception of the researcher’s social position relative to the participant group from the point of view of the observed as well as the observer that can raise objections or concerns (Serrant-Green Citation2002). These perceptions develop and evolve through interaction, experience and over time.

A central question remains: How does fluidity enable or constrain the researcher in that particular situation? What are the practical implications? This paper seeks to move beyond the process of categorisation and instead unpack the labelling by investigating how the role as insider or outsider is being assigned to the researcher in situ as influenced by context and interaction with organisational members. In what ways were we considered (by our research participants) as insiders/outsiders? What personal attributes were magnified by our research participants, why and to what effect? What characteristics were made relevant and what decisions did we take as a result? In other words, how can we explain the experiences and perceptions captured in the opening vignette?

The Welsh context

Wales is a devolved nation characterised by a strong sense of bilingualism and where the Welsh language is an important part of its national identity and legislative framework (see Jones and Lewis Citation2019). There is a strong association between language and identity with an image of Wales and of Welshness often mediated through Welsh as opposed to through English and or bilingually. The Welsh language and its role in a ‘truly bilingual nation’ (Welsh Assembly Government Citation2003, 1) have long occupied the ‘foreground of linguistic and sociolinguistic research’ (Coupland and Thomas Citation1989, 1), following the political rhetoric of an officially bilingual Wales. Despite the de facto linguistic reality of ‘unofficial multilingualism’ (Barakos Citation2020, 22), the official language policy discourse has prioritised a Welsh-English rather than multilingual agenda. It is only recently that there has been a more dedicated scholarly focus on Wales as a multilingual and multicultural nation, which complexifies the power struggles between Welsh and English and issues of identity and belonging within a multilingual Welsh society. Bermingham and Higham’s (Citation2018) study on immigrants as new speakers of Welsh or Hornsby and Vigers’ (Citation2018) study of new speakers of Welsh in the heartlands are telling examples of how different types of speakers and learners, alongside traditional minority language speakers, negotiate different senses of speakerhood and co-occupy different claims for speaker legitimacy. In this study, however, we take the lead from our participants in focusing only on Welsh-English bilingualism – it was bilingualism which resonated with our participants, which was discursively constructed by various players and within various sites and which was performed in everyday practice.

The Welsh language and its cultural milieu have been instrumental to its distinctive national existence, despite its decline throughout the twentieth century. Described as the ‘most material of all differences’ (Johnes Citation2016, 683), the Welsh language is a concrete and undeniable marker of Welsh identity, difference and distinctiveness. For this reason, it plays an important role in how Wales and Welshness is imagined, for Welsh speakers and non-Welsh speakers alike. Yet, the Welsh language can be seen as contentious and a problematic basis for Welsh national identities due to its minority position. Welsh is spoken by less than a fifth of the Welsh population (17.8%), a drop from 19% in 2011 (Office for National Statistics Citation2022). Its ‘otherness’ to much of the Welsh population means that its role in people’s sense of Welshness is not straightforward. It can represent ‘another’ Wales, one from which people and communities can feel excluded (Roberts Citation1999, 123).

There is a long history of antagonism between the English and Welsh languages and its speakers in Wales (see Coupland and Thomas Citation1989; Mann Citation2007, Citation2011), vested in a discourse of a ‘truly bilingual Wales’ and the concept of language choice between Welsh and English. These historical power struggles remain unresolved in many areas of social life despite policy and legislative interventions and government support for Welsh. The primary ethnic divide in Wales remains that between the Welsh and the English (Williams, Evans, and O’Leary Citation2003, 11). English has, historically at least, been seen as the ‘language of the oppressor, the language of the overseer’ (Williams Citation2002, 173). As Jones and Martin-Jones (Citation2004, 44) add, English has served as ‘the language with the greatest power and authority’ in Wales and therefore, in some instances, speaking English will be conceptualised as a form of symbolic violence (Bourdieu and Passeron Citation2013). This unequal relationship between the two languages marks claims over language choice, authority, identity, legitimacy and nationhood that keep being re-negotiated (Barakos Citation2020, 20). Perhaps it is for this reason that the majority of researchers working within the Welsh context choose to ignore the potentially contentious issue of whether and to what extent they can use the Welsh language. To date (with the notable exception of Hodges (Citation2021) who acknowledges her position as a ‘new speaker’ of Welsh) researchers in the Welsh context have not approached or represented their identities when researching bilingualism in Wales. Greater transparency in this regard could be beneficial.

Representations of the English (in Wales) conform to a pattern whereby incomers are ‘overwhelmingly constructed as a negative influence or threat’ (Burnett Citation1998, 208) and identified as a source of unintended generalised harm (Jedrej and Nuttall Citation1996, 95). However, the future vitality of Welsh is, in part, ‘contingent upon the nature, use and institutional support and social significance of English’ (Coupland and Thomas Citation1989, 1). It is neither possible nor desirable to consider either language in isolation. Instead, our intention here is to reflect on the use and presence of the two languages throughout the research process. The complexities of the Welsh language context provide a valuable access point for exploring the notion of insider/outsider in minority language research. We can relate the intricacies and challenges inherent in the sociolinguistic context of Wales to an early and frequently cited question posed by Fishman, namely ‘who speaks (or writes) what language (or what language variety) to whom and when and to what end?’ (Fishman Citation1972, 46). Bearing this question in mind, the next section introduces our own empirical projects, inherent language choices and our identities and positionalities as researchers therein via a reflexive and narrative account.

Researcher positionality

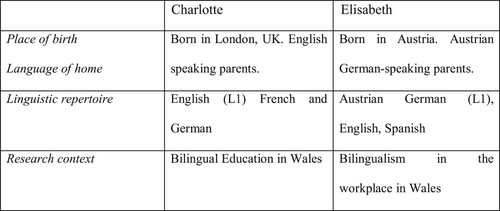

provides a summary of our research backgrounds and our own linguistic repertoires.

Charlotte

Charlotte was born to English-speaking parents and grew up near London. She always felt some connection with Wales owing to strong family ties – her father spent most of his formative years in North Wales. Though much of her father’s family (including both his parents) were first language Welsh speakers, they deliberately chose not to impart the language to their children because English was seen as the language of the future, Welsh as a sign of regional backwardness. Charlotte’s mother grew up on the Welsh/English border in south-east Wales but was educated in England. Two of her four siblings later moved to live in west-Wales, where they remain to this day. Consequently, throughout Charlotte’s childhood she spent many happy weeks in Wales, visiting aunts, uncles and cousins. Despite this strong connection with Wales, Charlotte grew up with little awareness of the Welsh language, choosing instead to study French and German until A-level (18 years old).Footnote2 It was not until she embarked on her undergraduate degree at a Welsh University that she started to discover Welsh and to identify with some of her cultural and linguistic heritage. This interest intensified during her postgraduate years and culminated in her PhD research project which forms the basis of this reflective account.

Charlotte’s PhD research investigated the interplay of linguistic practices, linguistic representations, language ideologies and social inclusion between students at three related research sites in south-west Wales; a designated English-medium school, a designated Bilingual school and a Youth Club, acting as a point of contact between students from both schools. The study set out to investigate how the young people at these two contrasting (and ideologically polarised) secondary schools in a ‘community’ traditionally thought of as a heartland area understand and orient to the language ideological content of their education. Three methods characterised this research; ethnographic observational fieldwork, ethnographic chats (Selleck Citation2018a), and audio recordings of spontaneous interaction (for a discussion of some of the findings, see Selleck, Citation2013, Citation2016, Citation2018b).

As mentioned, Charlotte has family living in the area under scrutiny in this research and had spent time in the area throughout her childhood. From the outset, many community members knew of her or her family connection. Charlotte was often recognised by people who either knew her as a child or who perceived a strong family resemblance. Additionally, Charlotte met many research participants through family connections. Accordingly, she was afforded partial insider status and accepted much more readily by the community in question. The partial insider status also afforded access to groups which may otherwise have been more difficult to secure. Charlotte was, however, simultaneously considered an outsider principally in terms of her own linguistic repertoire (Busch Citation2012) as a largely monolingual English speaker, recognised as originating in the south of England but also in terms of her affiliation with an elite university.

Elisabeth

Elisabeth was born in Austria and grew up speaking Austrian German. At school, she learnt English, French and Italian. Elisabeth studied English and Spanish Linguistics and Literature. Her ‘linguistic repertoire’ (Busch Citation2012) is multilingual, so she also identifies as a multilingual speaker who mobilises this repertoire to differing degrees in a flexible, context – and skills-dependent manner. Having spent extensive periods in English-speaking environments, Elisabeth has repeatedly been taken as a ‘native speaker’ of English (mostly classified as a ‘British English’ or ‘South African English’ speaker), with people having made assumptions and positive appraisals about her linguistic identity, based on her apparent fluency and her ‘authentic’ accent. They have been perplexed whenever she had to rupture such ideological assumptions.

Elisabeth’s decision to start a research project on language policy and bilingualism in businesses in Wales was motivated by an internship at the Council of Europe’s European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages back in 2008 and a genuine interest in minority language policy processes. The motivation for examining language promotion in professional sites and workplaces stems mainly from the then limited data about the role of the Welsh language in business, and her own institutional embedding as a linguist at a business university in Vienna at the time of research. Via extended fieldtrips to Wales, Elisabeth was able to examine Welsh-English bilingualism in private sector businesses and the circulating discourses, ideologies and practices of promoting bilingualism as a sociocultural and economic resource. The study includes an empirical survey with businesses throughout Wales about the perceived role, relevance and visibility of Welsh vis-a-vis English, based on an online questionnaire and qualitative in-depth interviews with managerial staff and a close textual analysis of various political and corporate language policy documents produced in connection with promoting corporate bilingualism (see Barakos Citation2012, Citation2016, Citation2020).

Elisabeth largely adopts a position from both the ‘inside’ and the ‘outside’ in her research on Wales (see also Blackledge and Creese Citation2010; Sallabank Citation2013 for inside/outside perspectives). She takes an ‘inside’ perspective in terms of directly engaging with Welsh businesses in the field through survey and in-depth interview data as someone who works at a business university, who teaches about the role of language in the workplace and who has had experience with minority language policy processes. That is, this ‘inside’ view mainly relates to her expertise as a sociolinguist and language policy scholar examining the role of minority languages in business contexts. The ‘outside’ perspective relates to her linguistic repertoire (Busch Citation2012) as a multilingual but a non-Welsh speaker, and the fact that she is neither a citizen nor a resident of Wales and carried out her research mainly from outside of Wales and through the medium of the dominant language in Wales, English. As argued in Barakos (Citation2020, 3), this ‘“outsiderness” has inherently raised questions over the legitimacy of a multilingual, yet not Welsh-English bilingual, scholar who examines a Welsh-English business community through the shared language of English’.

Analysis: the negotiation of researcher positionality and insider/outsiderness

Inspired by the theoretical considerations introduced earlier, we illustrate the ‘methodological dilemmas’ (Day Citation2012, 61), that is, the challenges and implications, for carrying out both our projects through the shared and yet socio-politically powerful medium of English via the discussion of thematic examples from our data sets. Both projects were carried out through the medium of English, which was a deliberate methodological choice. Guided by research questions, the first aim of the analysis is to understand how we, as researchers, are positioned by our study participants in terms of language competency (in our case, the role of English as the medium of communication and the missing Welsh language option in our research); the second aim is to examine how English is positioned in terms of insider/outsiderness. In what follows, we offer thematic examples from our research that illuminate the interconnects of language, legitimacy and positionality within the two projects. We identified these thematic examples retrospectively by going back to our data and pinning down those themes from our data sets (interviews, survey data and ethnographic chats) that specifically question and problematise our research persona and language competency, insider/outsider status and attendant processes of legitimacy in producing knowledge about the Welsh language through participants’ metapragmatic discourse on language practices and language choice.

How were we, as researchers, positioned by our study participants in terms of language competencyFootnote3?

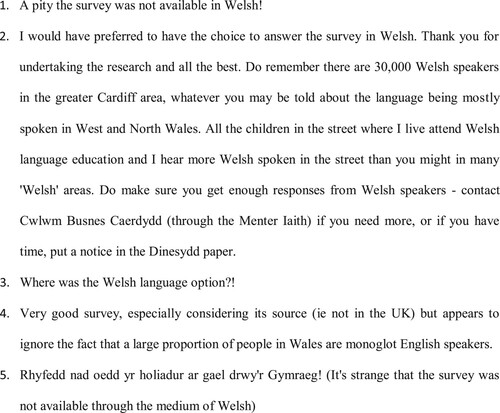

In , we illustrate data that serves as a source of reflexive debate about Elisabeth’s insider/outsider positionality in terms of participants’ metapragmatic discourse on language use and language choice.

Figure 3. A sample of comments from the end of an online questionnaire about bilingualism in the workplace. Taken from the research of Elisabeth.

The thematic examples presented here are taken from an open-ended comments section at the end of an online-questionnaire, administered by Elisabeth. The questionnaire was targeted at a wide range of private sector businesses throughout Wales (see Barakos, Citation2020). The survey was available in English-only for various methodological reasons: at the time of data collection, Elisabeth was a sole researcher pursuing a PhD from outside of Wales who negotiated her way into the Welsh research landscape via extended field trips. Elisabeth was also a non-Welsh speaker so she would have had to rely on and pay for a translator to make the survey available through the medium of Welsh and also for the survey data to be translated and interpreted through Welsh. These personal and methodological decisions are situated within the political and legal positioning of Welsh as an official language in Wales and the right to use the language in the delivery of public (and some private) services in Wales. In what ways, then, does such an existing framework influence participants’ assumptions about (and potentially preferences for) a Welsh-English bilingual option for research surveys about the Welsh language? After all, with this survey, Elisabeth did not facilitate such an option. The comments above mirror an underlying expectation for a Welsh-English language choice.

In Elisabeth’s case, the choice of the research design through the shared language of English, which is also the dominant and more powerful language against which Welsh speakers have been historically struggling, has had implications on the type of data collected, the data collection process, the type of participants in the research (in view of the English nature of the study) and, as we will illustrate, how this was received by the participants.

As we see here, positioning always goes hand in hand with evaluation processes. In the examples, we see a range of evaluative comments on the quality of the survey and the missing Welsh language option: from appraisal in example 4 (‘very good survey’) and articulating preferences in example 2 (‘I would have preferred … to answer in Welsh’) to questions and evaluations in example 3 (‘where was the Welsh language option’) and 5 (‘it’s strange … ’). The choice of emphatic punctuation in example 2, a question mark combined with an exclamation mark (‘!?’), serves a pragmatic function: it highlights a level of affective surprise (about the missing Welsh language option) and an underlying expectation to be offered a language choice.

Example 2 is a poignant case of making Elisabeth’s own ‘outsider’ status in terms of her apparent lack of knowledge on the sociolinguistics of Wales relevant. Here, the participant uses the imperative (‘do remember’; ‘do make sure’) to convey a sense of insider knowledge about the Welsh language and reinforce Elisabeth’s outsider status as someone who apparently lacks this type of knowledge. So Elisabeth’s integrity as a researcher appears to be questioned, based on her apparent missing linguistic competencies and knowledge about Wales.

Example 5 illustrates a case of lived out language choice, with the participant’s choice for providing their open-ended comment in Welsh first, followed by English. This deliberate choice problematises Elisabeth’s own Welsh language competency (not knowing Welsh). The essence of the respondent’s argument here rests on the assumption that since Wales is bilingual, a choice should also be offered when conducting research about bilingualism. Such assumptions tie to broader ideologies about choice that rest on a ‘‘truly bilingual’ ideal’ (Coupland and Bishop Citation2006, 47) and a parallel bilingualism which gives Welsh and English ‘equal weighting and prominence, so that the same access is afforded to each language’ (Coupland Citation2010, 87).

These examples above demonstrate the ways Elisabeth’s methodological decision for not providing a Welsh language option has created tensions and contradictions over her social positioning as a researcher. How, then, can such tensions be reconciled? Elisabeth was aware of the limitations of an English-only survey and acknowledged that many more participants could have filled in the survey or could have felt more at ease if it was bilingual and if they had been offered a language choice. This dilemma gives rise to a range of pertinent questions and points out the polarisation of the notion of a ‘full language choice’ in bilingual Wales (as documented and critically discussed in e.g. Selleck Citation2013; Barakos Citation2020; Coupland and Bishop Citation2006). Does the lack of choice reproduce a monolingual paradigm and contribute to the production of linguistic inequality? Likewise, does the lack of choice provided in the survey warrant the judgmental comments received? Such questions relate to bigger issues over how a bilingual and linguistically equal Wales is imagined, and who gets to make this decision in the first place. So, when Blackledge and Creese (Citation2010, 220) ask, ‘[w]hich linguistic practices are authorized, by whom, and why?’, we need to ask which language is legitimate to produce knowledge in minority language contexts (see Heller and Martin-Jones Citation2001).

In addressing some of these questions, we need to orient to studies in multilingual team-based ethnography (e.g. Blackledge and Creese Citation2010; see also Reilly et al., this issue) that highlight the advantages of conducting multilingual research in linguistically diverse educational contexts for the meaning-making process of multilingual data, for the research participants and researchers involved as well as for combating the reproduction of a monolingual mindset. Offering a language choice helps ‘gaining the trust of research participants’ and helps ‘shaping relations with those in the field’ (Blackledge and Creese Citation2010, 105). In Elisabeth’s research, the question was, however, not necessarily about gaining trust via language. The language question was not perceived as a barrier to entering the field because of English as the shared medium of communication. This may be due to the fact that Elisabeth conducts research as a perceived outsider to Wales and the UK more broadly, as one participant acknowledges in their comment on the quality of the survey (‘Very good survey, especially considering its source (i.e. not in the UK’)). In hindsight, we need to acknowledge that working in a multilingual team offers a much wider range of methodological opportunities for allowing language choices than working as a lone researcher, as the two projects in this paper illustrate.

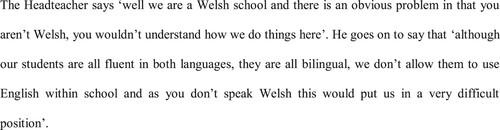

In , we discuss another example, this time from Charlotte’s research, that shows how researcher identities are made relevant during the research process.

Here, Charlotte’s position as a non-Welsh speaking researcher was made relevant by the Headteacher at the Welsh-medium school, reflecting the argument put forward by Martin, Stuart-Smith, and Dhesi (Citation1997), in which language competency was explicitly mentioned as a marker of insiderness. The Headteacher suggested that because Charlotte didn’t speak Welsh, she ‘wouldn’t understand how they do things’. Charlotte is being positioned not only as an outsider, ‘we’ (Welsh speaking) vs. ‘you’ (English speaking), but as unable to understand how they ‘do things’, their approach and ideology. Whilst Welsh language competence was, for the Headteacher at the Welsh school, integral to insider status (both for Charlotte as a researcher and, for the students who attend the school – see Selleck Citation2013), sharing a language doesn’t fully guarantee any sort of insiderness in itself. That said, their initial unwillingness to grant Charlotte (as a linguistic outsider) access to classrooms is indicative of a protectionist ideology towards the Welsh language and we see this extended towards the students in their care. As a Welsh only space, characterised by an ideology of ‘separate bilingualism’ (Blackledge and Creese Citation2010; see also Selleck Citation2013) the presence of an outside and presumably undesirable influence posed an obvious challenge to the school – one that challenged their authority over the space and those working and studying within it. The Headteacher indicates in the above extract, that the construction of this monolingual Welsh only enclave requires a considerable amount of management, control and intervention which seemingly involves limiting and controlling who is allowed access to the school. In this sense, Charlotte’s identity as an English speaker was problematised – English was delegitimized in this context and it was clear that language politics was entangled with how she was positioned. The perception of a language barrier seemed to pose an obstacle to trust formation, at least on the part of the Headteacher. Kasper-Fuehrer and Ashkanasy (Citation2001, 236) argue that trust is ‘the basic ingredient of collaboration’. Several scholars have noted that language-related issues can significantly impact trust formation (Feely and Harzing Citation2003; Jonsen, Maznevski, and Schneider Citation2011; Neeley Citation2013; Piekkari Citation2006). Language barriers (or perceived language barriers) can distort and damage relationships and give rise to insecurity and distrust.

There was an obvious and understandable reluctance on the part of the Headteacher to work through the medium of a shared language, where this shared language was English (see discussion above for a more detailed discussion of the long history of antagonism between the English and Welsh languages and their speakers in Wales). Considerable time and effort was needed to work at relationship and trust building in order to negotiate perceived linguistic boundaries. The situation was partially resolved by working with a confederateFootnote4 to ensure that Charlotte was able to offer the participants a choice as to which language(s) to use during the research process.Footnote5 Her confederate was a twenty-one-year-old undergraduate student who had herself attended a Welsh-medium school near to the sites involved in this project. She was therefore familiar with the west Wales educational context and able, where necessary, to provide additional commentary. In this way, she played an active role in the research process, acting as a research broker, a mediator, extending her role from data collection to analysis for purposes of safeguarding validity (Tsai et al. Citation2004). This allowed Charlotte to counter the notion that research findings may be affected by the researcher’s limited knowledge of the participants’ language or the lingua franca (Pavlenko Citation2005).

Charlotte wanted to ensure that she was able to offer the participants a choice as to which language(s) to use during the research process. Given her limited competency in Welsh, this would have been impossible to achieve with a researcher-facilitated approach such as an interview or a focus group. This required some methodological innovation, giving rise to what became known as an ‘ethnographic chat’ (Selleck Citation2018a). In short, the ethnographic chat saw groups of research participants join together, without the researcher, to discuss a set of prompts, which were pragmatically realised as open-ended ‘topics’ rather than specific questions. The prompts were written in both Welsh and English and participants were given the choice as to which language(s) to use and were explicitly told they could use both. It has been argued elsewhere (Selleck Citation2018a) that the ethnographic chat allowed for an element of structure without compromising participants’ freedom to elaborate on topics of interest to them. Students were free to talk openly and free from any constraints on their choice of language (or indeed the choice to code-switch). Developing the ethnographic chat enabled Charlotte to find new spaces to experiment in, to allow new insights to arise; and it is possible that the same approach could allow other researchers similar new perspectives.

In summary, whilst the situation was partially resolved, the experience was useful in understanding ‘indexes of the norms, frames of reference, ideologies, positionings, and interests that are such important dimensions of sociolinguistic research’ (Heller Citation2011: 45). In other words, whilst social relationships in the research field needed to be smoothed out and negotiated as access to data depended on these relationships, rich data was also acquired through being reflective when resistance was encountered.

How is English positioned in terms of insider/outsiderness?

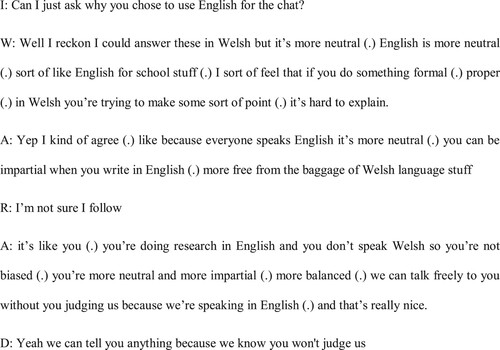

Up to this point we have problematised our non-Welsh speaking position. We now turn to how we were positioned by our participants in terms of the role of English. As we will see, our ‘outsider’ position is seen as a positive attribute by some .

Figure 5. Ethnographic Chat with students from ‘Welsh’ stream of the English medium school as part of Charlotte’s research.

This extract comes from the end of an ethnographic chats, carried out with students from the Welsh stream of the English medium school as part of Charlotte’s research.Footnote6 All students in the Welsh stream have competency in Welsh equivalent to that of an L1 speaker. It is therefore worth noting that these students could easily have chosen to conduct the ethnographic chat through the medium of Welsh but didn't. We can see the students discussing their reason for choosing English as the medium of communication. Here the students position English as an apparent ‘neutral’ language for shared communication, a Lingua Franca. This apparent neutrality also emerged elsewhere in Charlotte’s project with students claiming that English was ‘open to everyone’ and therefore ‘less judgmental’. This is extended to Charlotte (I), with the students articulating a perception of her as a neutral outsider, someone who can remain impartial, unbiased and they say more balanced.

Whilst English, ideologically, is anything but neutral in the Welsh context, particularly in relation to education, for these young people, it would seem that English is the language of choice, the unmarked linguistic variety for this type of interaction (see Myers-Scotton Citation1983). The students seem to position it as more professional, more suitable for a formal or as they say ‘proper’ genre. Had they chosen to do this chat in Welsh this would have, for them at least, been a marked choice. English is for these students free from the ideological ‘baggage of Welsh’ (See Selleck Citation2013, Citation2016 and 2018a for insight into what ideological baggage may mean for these students).

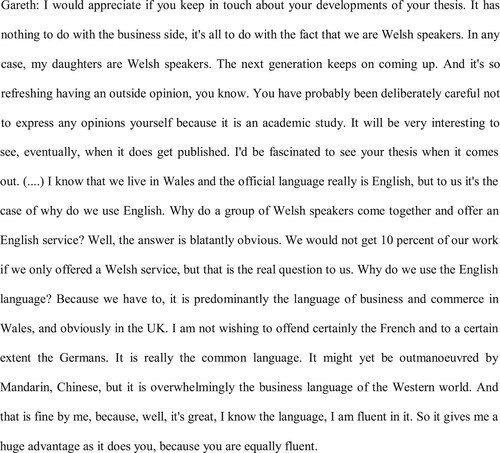

illustrates an extract from an interview, as part of Elisabeth’s study, with GarethFootnote7, a Welsh-speaking business representative of a consultancy firm, based in North-Western Wales that sees a large concentration of Welsh speakers.

Towards the end of the interview, Gareth shows great interest in being kept informed about the results of the study. He clearly distinguishes his personal interest in Welsh language matters from the interests of the business (‘It’s nothing to do with the business side’) and justifies his interest by mobilising ideologies of belonging, togetherness and membership by repeatedly drawing on the use of pronominal ‘we’ (‘we are Welsh speakers’; ‘we use’; ‘we have to’) to enact Welsh identity and signal group membership. He goes on to draw on the notion of researcher outsiderness, which he positively constructs as something ‘refreshing’ that allows having ‘outside opinions’. Gareth positions Elisabeth’s researcher self as an academic who wouldn’t ‘express any opinions’, here alluding to the assumed ‘neutrality’ of academic research.

At a later stage, Gareth acknowledges the role of English as the dominant business language in the UK and, as he argues, ‘the Western world’. At the same time, he problematises the use of English in a largely Welsh-speaking context. He asks a rhetorical question about the role of English in Wales (‘why do we use the English language’), with ‘we’ demarcating Welsh-speaking group membership and considers the use of English as an obligation (‘because we have to’). He also acknowledges the role of English as a language with a de facto official status, despite Welsh holding official status in Wales since the new language law, the Welsh Language Measure (2011)Footnote8, was passed. In fact, Gareth considers the use of English as a business obligation in order to secure transactions (‘we would not get 10 percent of our work’), although the consulting firm is located in a Welsh-speaking heartland and its employees share Welsh as the language of the majority.

Underlying Gareth’s discourse are issues of linguistic dominance and power that point to the existing inequality arising from the lack of parity in status and usage of Welsh and English. And yet, Gareth emphasises the advantage of being a fluent English speaker himself (‘it’s great, I know the language’). He then comments on Elisabeth’s own English language skills and appraises it as ‘equally fluent’. Fluency is used here as a marker for creating advantage in the language market, making Elisabeth an insider of the group of people who can speak the dominant language, English, fluently, just like Gareth. Insider/outsiderness, and its attendant advantages on the language market, is thus negotiated on the terrain of language competencies and skills via a ‘political economy of linguistic resources’ (Blackledge and Creese Citation2010, 2018). Gareth has appreciated Elisabeth’s outsiderness, with someone ‘from outside the Welsh bubble’ conducting a study on bilingualism: someone with no ethnic or national ties to Wales, with an analytic distance to the data and research process (cf. Barakos Citation2020, 4). At the same time, he constructs Elisabeth as an insider in terms of the shared medium of communication – English – which affords her crucial field access.

Discussion

This article has discussed, retrospectively, the negotiation of our insider/outsider research identities in the context of two projects conducted in Wales, with the aim of developing a reflexive approach to researching bilingualism. With declining numbers of Welsh speakers, there is a pressing need for further qualitative research that captures the reality on the ground. Crucially, such research should allow multiple voices into the discussion. This somewhat idealistic aim, however, fails to fully account for the various judgments that were made and the obstacles we faced as part of our own research on Welsh. We, as researchers, found ourselves falling foul of language attitudes – our status, legitimacy, intelligence and competency were, at times, judged based on the way we used language (see Garrett Citation2010). Perhaps this was to be expected, given the troubled history of language contact and a sharp differentiation of the symbolic values of the languages involved in the Welsh context. That said, the sometimes negative evaluations are ongoing – they are not just isolated to the research field but reappear in the peer-review process and at conferences. Comments such as ‘should you really be researching the Welsh context when you’re not Welsh’ are all too common. So, we wonder whether our lack of competency in Welsh discounts us from doing this type of research? Is it acceptable for us to engage in research that grapples with a sociolinguistic issue where we don’t share the language that sits at the centre of debate (here Welsh), but where we do share another language, the English language? We also question whether a renewed focus on multilingual Wales – ‘a Wales that juggles a multitude of languages and language varieties’ (Barakos Citation2020, 154) – would in turn create a more inclusive research environment, one that is open to diverse and sometimes conflicting research perspectives?

These questions give rise to more significant concerns. Sociolinguistics is committed to equality and inclusivity, but here we see that certain researchers feel shut out from certain research contexts because of a lack of knowledge of the local language. This is ultimately a question of legitimacy and whose ‘voice of authority’ is heard (Heller and Martin-Jones Citation2001). Giampapa (Citation2019) extends the discussion on researcher identities and field relationships further by critically asking about ‘revaluing what knowledge and whose knowledge counts’ in the context of democratic knowledge production processes and field relationships.

In grappling with the notion of insider/outsiderness, we align with Sharma’s (Citation2021, 249) argument that we should ‘move away from issues of the researcher effect as a methodological limitation and should investigate opportunities for an understanding of the researcher and the participants alike in relation to epistemological and ontological questions’. In this sense, we could argue that our so-called outsider status afforded us analytic distance on the research and on the emergent data and therefore the ability to reflect on and critique the Welsh context. We didn’t feel weighed down by a desire to protect the minority language nor to play our part in the revitalisation effort as such – so we were under no pressure to produce findings that conformed to institutional, cultural or social expectations. Of course, we equally would not want to play any role in the hastening of language decline.

Our partial outsider status resulted in participants feeling the need to fully explain and justify their experiences and views as opposed to implying and assuming knowledge on our part. Participants would pre-empt their contributions with comments such as ‘you’re not from around here so I’ll explain it as best I can’. This was of course invaluable in the research context. Caution is still needed in making a distinction between so called insiders and outsiders. In line with Merton (Citation1972) we would call for researchers to ‘unite’, instead of focusing on how inter-subjectivity or ‘presumed’ objectivity leads to greater insights. Whilst researchers are different, bringing different perspectives and experiences, we ultimately have the same job: to shed light on the experiences of those with whom we research.

Fundamentally, the issues we experienced in researching within the bilingual community of Wales seem to relate to trust. Most often, it was participants’ assumptions about who we were that had the biggest effect, not least in the extent to which they trusted us. For Charlotte, people were more trusting when they found that she had family living in the community whereas for Elisabeth, people were trusting when they knew she came from a business university. This trust helped greatly in terms of securing interviews and building a relationship, regardless of perceived language barriers. As practical advice, researchers can at best understand how the community perceives itself and how it perceives the research, the researchers, and the institutions it represents. Honesty with subjects is key, and researchers must be willing to address with the community any area that may cause distrust.

In short, research of the nature presented here demands a level of ‘mindfulness’ and a critical perspective about language, identity and relational meanings in an intercultural setting, which raises questions, tensions and dilemmas over the roles, statuses and positionalities of the multilingual researcher and subject. With this paper, we have initiated an important conversation on such dilemmas and tensions.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank our special issue editors for their continuing support, patience and guidance on this publication project throughout the challenging times of a pandemic. We are also grateful to our reviewers’ insightful feedback on earlier versions of this paper and to Michael Hornsby for translating our abstract into Welsh – diolch! All remaining shortcomings of this article are entirely ours.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Both of these projects were carried out between 2007 and 2013. By conventional standards this data may be considered dated. However, this article is of a reflective nature and it is this very gap between when the data was collected and now that we will address.

2 Participants were not explicitly made aware that Charlotte did not speak Welsh. Many of the participants assumed that Welsh was not part of Charlotte’s linguistic repertoire. A smaller number explicitly asked.

3 It should be noted that this question is retrospective in nature. Whilst we, as researchers, continuously reflected on our position in the field, this question was not directly posed to participants.

4 A confederate is best thought of as a person recruited by the lead researcher to play a role in the research process.

5 It should be acknowledged that there were a unique set of challenges facing us during the course of these projects. Both were generated as part of the PhD process. PhDs are almost unanimously thought of as independent research projects carried out by a lone researcher and ours were no different. Whilst the benefits of conducting research in teams are well established (see, for example Blackledge and Creese (Citation2010), in that they allow for ‘plural gazes’ (Erickson and Stull Citation1998), this remains off limits given the constraints of the assessment process. If we are to equip students with the skills they require for their future careers – be that in academia or in industry, then there is a need for a long overdue disruption of the current PhD model – ‘the needs of contemporary graduates no longer fit traditional institutional structures’ (Higher Education Academy Citation2015).

6 Note that the researcher, having not been present for the ethnographic chat, had returned to collect the recording equipment. contains a follow up exchange that was captured on the recorder.

7 All names of study participants have been pseudonymized.

8 As a legal framework, the Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011 establishes Welsh as an official language in Wales; as such, the Welsh language must be treated no less favourably than the English language. See Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011 (legislation.gov.uk).

References

- Angrosino, M. V. 2005. “Recontextualizing Observation: Ethnography, Pedagogy, and the Prospects for a Progressive Political Agenda.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research (3rd ed), edited by N. K. Denzin, and Y. S. Lincoln, 729–745. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Archer, M. 2012. The Reflexive Imperative in Late Modernity. Cambridge: CUP.

- Barakos, E. 2012. “Language Policy and Planning in Urban Professional Settings: Bilingualism in Cardiff Businesses.” In Current Issues in Language Planning 13 (3): 167–186.

- Barakos, E. 2016. “Language Policy and Governmentality in Businesses in Wales: a Continuum of Empowerment and Regulation.” Multilingua, Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication 35 (4): 361–391.

- Barakos, E. 2020. Language Policy in Business: Discourse, Ideology and Practice. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Barakos, E., and C. Selleck. 2018. “A Reflexive Approach to Researching Bilingualism.” Paper presented at the TLANG Conference Communicating in the Multilingual City, University of Birmingham, March 28–29.

- Bermingham, N., and G. Higham. 2018. “Immigrants as New Speakers in Galicia and Wales: Issues of Integration, Belonging and Legitimacy.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 39 (5): 394–406. doi:10.1080/01434632.2018.1429454.

- Blackledge, A., and A. Creese. 2010. Multilingualism: A Critical Perspective. London: Continuum.

- Bourdieu, P. and J. C. Passeron. 2013. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. London: Sage.

- Bruskin, S. 2019. “Insider or Outsider? Exploring the Fluidity of the Roles Through Social Identity Theory.” Journal of Organizational Ethnography 8 (2): 159–170. doi:10.1108/JOE-09-2017-0039

- Burnett, K. 1998. “Local Heroics: Reflecting on Incomers and Local Rural Development Discourses in Scotland.” Sociologia Ruralis 38 (2): 20423. doi:10.1111/1467-9523.00072

- Busch, B. 2012. “The Linguistic Repertoire Revisited.” Applied Linguistics 33 (5): 503–523. doi:10.1093/applin/ams056

- Clark, J. Byrd, and F. Dervin, eds. 2014. Reflexivity in Language and Intercultural Education: Rethinking Multilingualism and Interculturality. New York: Routledge.

- Corbin-Dwyer, S., and J. Buckle. 2009. “The Space Between: On Being an Insider-Outsider in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8 (1): 54–63. doi:10.1177/160940690900800105

- Coupland, N. 2010. “Welsh Linguistic Landscapes ‘from Above’ and ‘from Below’.” In Semiotic Landscapes: Language, Image, Space, edited by A. Jaworski, and C. Thurlow, 77–101. London: Continuum.

- Coupland, N., and H. Bishop. 2006. “Ideologies of Language and Community in Post-Devolution Wales.” In Devolution and Identity, edited by J. Wilson, and K. Stapleton, 33–50. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Coupland, N., and A. Thomas. 1989. “Introduction: Social and Linguistic Perspectives on English in Wales.” In English in Wales. Diversity, Conflict, and Change, edited by N. Coupland, 1–19. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Creese, A., J. K. Takhi, and A. Blackledge. 2016. “Reflexivity in Team Ethnography: Using Researcher Vignettes.” In Researching Multilingualism: Critical and Ethnographic Perspectives, edited by M. Martin-Jones, and D. Martin, 203–214. London: Routledge.

- Day, S. 2012. “A Reflexive Lens: Exploring Dilemmas of Qualitative Methodology Through the Concept of Reflexivity.” Qualitative Sociology Review 8 (1): 60–85. doi:10.18778/1733-8077.8.1.04

- De Costa, P. I. 2014. “Making Ethical Decisions in an Ethnographic Study.” TESOL Quarterly 48: 413–422. doi:10.1002/tesq.163

- Erickson, K., and D. Stull. 1998. Doing Team Ethnography: Warnings and Advice. London: Sage.

- Feely, A. J., and A. W. Harzing. 2003. “Language Management in Multinational Companies.” Cross-Cultural Management: An International Journal 10 (2): 37–52. ISSN: 1352-7606.

- Fishman, J. A. 1972. “The Sociology of Language.” In Language and Social Context: Selected Readings, edited by P. Giglioli, 49–59. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books.

- Freeman, M., K. deMarrais, J. Preissle, K. Roulston, and E. A. St. Pierre. 2007. “Standards of Evidence in Qualitative Research: An Incitement to Discourse.” Educational Researcher 36 (1): 25–33. doi:10.3102/0013189X06298009

- Garrett, P. 2010. Attitudes to Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Giampapa, F. 2019. Researcher identities. The (re)negotiation of field identities, power and knowledge. Presentation at Linguistic Ethnography Forum, University of the West of England (UWE), 3 June 2019.

- Giampapa, F., and S. Lamoureux. 2011. “Voices from the Field: Identity, Language, and Power in Multilingual Research Settings.” Language, Identity & Education 10 (3): 127–131. doi:10.1080/15348458.2011.585301

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society. Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Heller, M. 2002. Éléments D'une Sociolinguistique Critique. Paris: Didier.

- Heller, M. 2011. Paths to Post-nationalism: A Critical Ethnography of Language and Identity. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Heller, M., and M. Martin-Jones, eds. 2001. Voices of Authority: Education and Linguistic Difference. Westport: Ablex Publishers.

- Heller, M., S. Pietikäinen, and J. Pujolar. 2018. Critical Sociolinguistic Research Methods: Studying Language Issues That Matter. New York: Routledge.

- Higher Education Academy. 2015. Interdisciplinary provision in higher education Current and future challenges. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/interdisciplinary-provision-higher-education-current-and-future-challenges (Last accessed on 11th May 2021).

- Hodges, R. 2021. “Defiance Within the Decline? Revisiting new Welsh Speakers’ Language Journeys.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, doi:10.1080/01434632.2021.1880416.

- Hornsby, M., and D. Vigers. 2018. “‘New’ Speakers in the Heartlands: Struggles for Speaker Legitimacy in Wales.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 39 (5): 419–430. doi:10.1080/01434632.2018.1429452

- Jedrej, C., and M. Nuttall. 1996. White Settlers: The Impact of Rural Repopulation in Scotland. Luxembourg: Harwood Academic Publishers.

- Johnes, M. 2016. “History and the Making and Remaking of Wales.” History: The Journal of the Historical Association 100 (343): 667–684. doi:10.1111/1468-229X.12141.

- Jones, R., and H. Lewis. 2019. “Wales and the Welsh Language: Setting the Context.” In New Geographies of Language, edited by R. Jones and H. Lewis, 95–45. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Jones, Dylan V., and M. Martin-Jones. 2004. “Bilingual Education and Language Revitalisation in Wales: Past Achievements and Current Issues.” In Medium of Instruction Policies: Which Agenda? Whose Agenda?, edited by J. Tollefson, and A. B. M. Tsui, 43–70. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Jonsen, K., M. L. Maznevski, and S. C. Schneider. 2011. “Diversity and its not so Diverse Literature: An International Perspective.” International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 11 (1): 35–62. doi:10.1177/1470595811398798

- Junker, B. 1960. Field Work: An Introduction to the Social Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kasper-Fuehrer, E., and N. Ashkanasy. 2001. “Communicating Trustworthiness and Building Trust in Interorganizational Virtual Organizations.” Journal of Management 27 (3): 235–254. doi:10.1016/S0149-2063(01)00090-3

- Mann, R. 2007. “Negotiating the Politics of Language.” Ethnicities 7 (2): 208–224. doi:10.1177/1468796807076845.

- Mann, R. 2011. “‘It Just Feels English Rather than Multicultural’: Local Interpretations of Englishness and Non-Englishness.” The Sociological Review 59 (1): 109–128. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2010.01995.x.

- Martin, D., J. Stuart-Smith, and K. K. Dhesi. 1997. “Insiders and Outsiders: Translating a Bilingual Research Project.” Paper presented at the British Association of Applied Linguistics Annual Conference.

- Merton, R. 1972. “Insiders and Outsiders: A Chapter in the Sociology of Knowledge.” American Journal of Sociology 78: 9–47. doi:10.1086/225294

- Mullings, B. 1999. “Insider or Outsider, Both or Neither: Some Dilemmas of Interviewing in Cross-Cultural Settings.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 30 (4): 337–350. doi:10.1016/S0016-7185(99)00025-1

- Myers-Scotton, C. 1983. “The Negotiation of Identities in Conversation: A Theory of Markedness and Code Choice.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 44: 115–136. doi:10.1515/ijsl.1983.44.115.

- Neeley, T. B. 2013. “Language Matters: Status Loss and Achieved Status Distinctions in Global Organizations.” Organization Science 24 (2): 476–497. doi:10.1287/orsc.1120.0739

- Norton, B., and M. Early. 2011. “Researcher Identity, Narrative Inquiry, and Language Teaching Research.” Tesol Quarterly 45 (3): 415–439. doi:10.5054/tq.2011.261161

- Office for National Statistics. 2022. Welsh Language, Wales: Census 2021. December 2022. Newport: Office for National Statistics.

- Pavlenko, A. 2005. Emotions and Multilingualism. Cambridge: CUP.

- Pérez-Milans, M. 2017. “Reflexivity in Late Modernity: Accounts from Linguistic Ethnographies of Youth.” AILA Review 29 (1): 1–213. doi:10.1075/aila.29.01per.

- Piekkari, R. 2006. “Language Effects in Multinational Corporations: A Review from an International Human Resource Management Perspective.” In Handbook of Research in International Human Resource Management, edited by G. Stahl, and I. Björkman, 536–550. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Plöger, S., and E. Barakos. 2021. “Researching Linguistic Transitions of Newly-arrived Students in Germany: Insights from Institutional Ethnography and Reflexive Grounded Theory.” Ethnography and Education 16 (4): 402–419. doi:10.1080/17457823.2021.1922928.

- Roberts, B. 1999. “Welsh Identity in a Former Mining Valley: Social Images and Imagined Communities.” In Nation, Identity and Social Theory: Perspectives from Wales, edited by R. Fevre, and A. Thompson, 111–128. Cardiff: University of Cardiff Press.

- Sallabank, J. 2013. Attitudes to Endangered Languages: Identities and Policies. Cambridge: CUP.

- Sarangi, S., and C. N. Candlin. 2003. “Trading Between Reflexivity and Relevance: New Challenges for Applied Linguistics.” Applied Linguistics 24 (3): 271–285. doi:10.1093/applin/24.3.271

- Selleck, C. 2013. “Inclusive Policy and Exclusionary Practice in Secondary Education in Wales.” International Journal of Bilingualism and Bilingual Education 16 (1): 20–41. doi:10.1080/01434632.2015.1093494.

- Selleck, C. 2016. “Re-negotiating Ideologies of Bilingualism on the Margins of Education.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37 (6): 551–563. doi:10.1080/01434632.2015.1093494.

- Selleck, C. 2018a. “Ethnographic Chats: a Best of Both Method for Ethnography.” Sky Journal of Linguistics 30: 151–162.

- Selleck, C. 2018b. “'We're Not Fully Welsh': Hierarchies of Belonging amongst 'New' Speakers of Welsh.” In New Speakers of Minority Languages: Linguistic Ideologies and Practices, edited by C. Smith-Christmas, N. Murchada, M. Hornsby, and M. Moriarty. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Serrant-Green, L. 2002. “Black on Black: Methodological Issues for Black Researchers Working in Minority Ethnic Communities.” Nurse Researcher 9 (4): 30–44. doi:10.7748/nr2002.07.9.4.30.c6196

- Sharma, B. K. 2021. “Reflexivity in Applied Linguistics Research in the Tourism Workplace.” Applied Linguistics 42 (2): 230–251. doi:10.1093/applin/amz067

- Spradley, J. 1980. Participant Observation. United States of America, Holt, Rinehartand Winston.

- Tsai, J., J. Choe, J. Lim, E. Acorda, N. Chan, V. Taylor, and S. Tu. 2004. “Developing Culturally Competent Health Knowledge: Issues of Data Analysis of Cross-Cultural, Cross-Language Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 3 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1177/160940690400300101

- Welsh Assembly Government. 2003. Iaith Pawb: A National Action Plan for a BilingualWales.

- Williams, C. 2002. Sugar and Slate. Llandysul, Ceredigion: Dwasg Gomer.

- Williams, C., N. Evans, and P. O’Leary, eds. 2003. A Tolerant Nation? Exploring Ethnic Diversity in Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Zinn, M. 1979. “Field Research in Minority Communities: Ethical, Methodological and Political Observations by an Insider.” Social Problems 27 (2): 209–219. doi:10.2307/800369