ABSTRACT

Parents who raise their children multilingually use various strategies to do so. Folk wisdom has it that the one-parent-one-language (OPOL) approach is the gold standard. However, there is no convincing evidence that OPOL is more beneficial for children’s language outcomes than strategies in which parents mix languages. This study explored potential differences between the beliefs and experiences of parents who used OPOL and parents who mixed languages, using questionnaire data from 134 multilingual families in the Netherlands. Three main questions were addressed: (1) Do OPOL and Mixing parents prepare differently for raising their children multilingually? (2) Do OPOL and Mixing parents express different attitudes towards multilingual upbringing? and (3) Do OPOL and Mixing parents report different experiences with multilingual upbringing? The results showed several differences between the groups. OPOL parents generally started preparing earlier for raising their children multilingually, for example, and were more likely to have made a conscious choice for a multilingual upbringing. Parents who mixed languages were more likely to consider a multilingual upbringing as more difficult than a monolingual upbringing and rate their own experience with multilingual parenting as ‘challenging’. Further research is needed to explain why these differences exist.

Many parents raise their children with multiple languages and they do so for various reasons (Grosjean Citation2012). There are several different strategies they may use to do this. Many different categorizations have been put forth (e.g. Romaine Citation1995), but a distinction is often made between families that adopt the well-known one-person-one-language (OPOL) strategy, in which each parent speaks a different language to the child (Barron-Hauwaert Citation2004), the Mixing approach, in which both parents speak multiple languages to the child (Blom, Oudgenoeg-Paz, and Verhagen Citation2018; Slavkov Citation2017; Verhagen, Kuiken, and Andringa Citation2022), the Time and Place strategy in which parents separate the use of two languages by time or location (or both) (Döpke, Citation1992; Tokuhama-Espinosa Citation2001), and the Minority Language at Home (ML@H) strategy, in which both parents speak a minority language to their child (Blom, Oudgenoeg-Paz, and Verhagen Citation2018; Slavkov Citation2017).

The relative merits of these strategies have been the subject of debate, especially regarding children’s language proficiency (Blom, Oudgenoeg-Paz, and Verhagen Citation2018; De Houwer Citation2007; Verhagen, Kuiken, and Andringa Citation2022). Other research has focused on the attitudes towards and experiences of parents with raising their children multilingually (Curdt-Christiansen Citation2016; Hoevenaars Citation2021; King Citation2016; Tsushima and Guardado Citation2019; Wilson Citation2021), looking in particular at parental beliefs about multilingualism, why parents chose a particular approach, how language choice and family dynamics may interact, and the challenges that multilingual families may experience. The present study adopts a similar perspective, and focuses on comparing attitudes and experiences between parents who use OPOL or a Mixing strategy. To this aim, questionnaire data from 134 multilingual families in the Netherlands were analyzed. Multilingual families in our study are defined as families in which more than one language is spoken, regardless of how many languages were used, how often, and when these languages were used. Thus, ‘multilingual’ is used as an umbrella term that includes bilingual families. Note, however, that in our literature review below, we use the term ‘bilingual’ when describing studies that used this term.

Language mixing and code-switching

Many parents in multilingual families regularly engage in language mixing (Bail, Morini, and Newman Citation2015; Byers-Heinlein Citation2013). Byers-Heinlein (Citation2013) found that over 90% of bilingual parents in their study self-reported to regularly mix languages when speaking to their child. Bail and colleagues (Citation2015) observed bilingual parents’ language use during short play sessions and found that all parents, including those who self-reported not to mix, code-switched at least once in the session and in 16% of their utterances on average. In contrast, results from De Houwer and Bornstein (Citation2016), obtained through parental report and observations at 5, 20 and 53 months, showed that bilingual mothers largely reported speaking only one language to their child, in line with the observation data showing that only some mothers produced some codeswitches, mostly at 20 months.

Parents are sometimes advised to avoid language mixing, for example by speech and language therapists or teachers, because it is believed that mixed language input is harmful for children’s language development (Blom, Oudgenoeg-Paz, and Verhagen Citation2018). Currently, the evidence on this issue is weak at best. In the above-mentioned study by Byers-Heinlein (Citation2013), a significant negative association was found between parents’ self-reported language mixing and children's receptive vocabulary at 1.5 years, but not at 2 years. However, Bail and colleagues (Citation2015) did not find that the degree of parents’ language mixing was correlated with vocabulary knowledge in 17- to 24-month-olds. In fact, in this study, a positive correlation was observed between the degree of parents’ code-switching and children’s vocabulary knowledge. Finally, Verhagen, Kuiken, and Andringa (Citation2022) found no significant relationships between the degree to which parents mixed languages and language proficiency in 2- and 3-year-olds who learned Dutch and another language, in neither of children’s languages. Thus, the existing evidence is mixed, with most studies showing no significant relationships between the degree to which parents mix languages and their children’s language outcomes, even though negative (Byers-Heinlein Citation2013) and positive (Bail, Morini, and Newman Citation2015) relationships have been reported.

Family language strategies

As noted above, three main strategies have been identified in multilingual families: OPOL, ML@H and Mixing approaches (Blom, Oudgenoeg-Paz, and Verhagen Citation2018; Slavkov Citation2017; Verhagen, Kuiken, and Andringa Citation2022). The present study will concentrate on OPOL and Mixing families – two types of families who speak multiple languages at home, and investigate how whether parents separate these languages relates to their beliefs and experiences. Previous research has shown that both strategies are used by parents in the Dutch (and Flemish) context, along with ML@H. Blom and colleagues (Citation2018), for example, looked at a diverse sample of multilingual families in the Netherlands and found that approximately two-thirds used a Mixing strategy, almost a quarter ML@H and a small proportion the OPOL pattern. Similarly, in a survey study among bilingual families in Flanders, De Houwer (Citation2007) found that in 65% families one or both parents used both languages, 24% used ML@H and 11% used OPOL (but note that parents were asked which languages they spoke at home, not which languages they spoke to their children). Finally, Verhagen, Kuiken, and Andringa (Citation2022) found in their sample of bilingual families in the Netherlands who spoke Dutch and another language that 36% used a Mixing strategy, 39% used ML@H, and 25% used OPOL.

Across studies, OPOL has been advocated as an appropriate strategy (Curdt-Christiansen, Citation2013; De Houwer Citation2009; Lanza Citation2007), partly because of earlier research showing that it can foster bilingual proficiency (Döpke Citation1992; Paradis and Genesee Citation1996; Romaine Citation1995). Barron-Hauwaert (Citation2004) notes that guidance for parents often suggests that OPOL is the ‘best’ strategy and that it must be strictly adhered to, but she acknowledges that OPOL is not the only possible approach to (successfully) raising bilingual children. Very few studies to date have assessed whether OPOL or more flexible strategies are more effective for stimulating children’s development in two languages. The existing studies suggest that there is no evidence that OPOL is more effective. Blom and colleagues (Citation2018) compared children from OPOL and Mixing families in the Netherlands and found that the groups did not differ significantly in Dutch productive and receptive vocabulary. Verhagen, Kuiken, and Andringa (Citation2022) found no significant differences in Dutch receptive vocabulary or general Dutch language proficiency (as rated by parents) between children from OPOL and Mixing families, although both outscored the ML@H group, and there were no differences in proficiency in the minority language between children from OPOL and Mixing families either. De Houwer (Citation2007) noted that ‘children growing up with two languages invariably learn to speak the majority language’, but that the main question is under which conditions they will also speak the minority language (419). This author found that the most successful parental language strategies, with more than 90% of families reporting at least one child to speak the minority language were ML@H as well as Mixing families where one parent spoke only the minority language and the other spoke both the minority language and Dutch. As for Mixing families in which both parents used both languages and OPOL families, 74-79% had one or more children speaking the minority language. Mixing families in which one parent only spoke Dutch and the other spoke both languages had only 36% of the children speaking the minority language (cf. De Houwer Citation2009). Taken together, these studies indicate that, despite popular ideas that OPOL is most beneficial for children to become proficient bilinguals (e.g. Piller and Gerber Citation2021), there is little evidence to back up this claim.

Parents’ attitudes and experiences

De Houwer (Citation1999) was one of the first to argue that parental beliefs and attitudes constitute an important factor influencing whether children grow up to be active bilinguals. She suggested that a supportive environment includes positive parental attitudes towards the languages involved and towards early childhood bilingualism, as well as ‘impact belief’: the belief that parents have at least some control over their child’s linguistic functioning. These attitudes and beliefs may contribute to parents’ language planning and linguistic behaviours, which, in turn, may influence children’s linguistic outcomes (Curdt-Christiansen Citation2016; De Houwer Citation1999; Roeleveld Citation2016). In recent years, the field of family language policy has moved from looking at relationships between parents’ beliefs and child language outcomes to questions about multilingual families’ experiences and identity construction (King Citation2016).

A few earlier studies have investigated parents’ attitudes, beliefs and practices concerning language mixing versus language separation. Wilson (Citation2021), for example, investigated parental language beliefs and management among French-English bilingual families through questionnaires among 164 families and 2 in-depth case studies involving interviews and observations. The study showed that parents generally reported positive attitudes towards language mixing, but believed they should avoid language mixing at home. Specifically, whereas 65% of the parents stated in the questionnaire that mixing practices were natural for bilinguals, 92% of the parents declared that speaking only French would be the best strategy for their families. Likewise, Piller and Gerber (Citation2021), in an analysis of posts on an Australian parenting forum, observed that posters almost unanimously recommended OPOL as the ‘best’ strategy and the one they used, or planned to use themselves, while language mixing was regarded negatively. Finally, in a study by Ballinger et al. (Citation2022) in which 27 multilingual families in Quebec were interviewed, most parents believed that language mixing was permissible and that parental mixing would not cause difficulties for children. However, the authors observed that parents transmitting heritage languages were more concerned about their child mixing languages than parents in French/English bilingual families. Taken together, these studies show that reported attitudes and beliefs can be conflicting and do not always align with reported practices.

Furthermore, research shows that positive attitudes towards child multilingualism do not always translate into positive experiences with raising children multilingually. In Piller and Gerber (Citation2021), forum posters thought bilingualism would be valuable for a child, but many were concerned that acquiring a minority language would jeopardise the child’s development in the majority language. Also, while many parents on the forum were committed to using the OPOL strategy, they often reported what the authors call ‘implementation problems’, such as the other parent not consistently speaking their language. Curdt-Christiansen (Citation2016) investigated language ideologies and practices of multilingual families in Singapore and found that these families struggled with contradictory expectations: while they placed cultural value on minority languages, the instrumental value associated with the dominant language (English) led children to receive very little input in their other (non-English) languages. Tsushima and Guardado (Citation2019) found similar results in interviews with Japanese mothers in families in Montreal. Most of the mothers felt conflicted because they wanted to speak Japanese with their child and their child to become proficient in this language, but they sometimes chose to stop prioritising Japanese to promote the development of other languages, because they recognised that French and English were valued much more highly outside the home. Some mothers expressed specific concerns regarding the OPOL approach, being worried whether their child could acquire ‘authentic fluency’ in Japanese when hearing it only from his mother (320).

Multiple parents in de Hoo’s (Citation2014) study on Frisian-Dutch bilingual families expressed in interviews that OPOL was a natural choice for them, because one of the parents was not a native speaker of Frisian and did not feel comfortable using this language with the children. Barron-Hauwaert (Citation2004) reported similar considerations among the OPOL families she surveyed. She also shared some case studies of parents who found it challenging to stick to the OPOL approach, for example, because they felt uncomfortable speaking the minority language to their child outside the home, found it difficult to avoid mixing languages or keep speaking their native language to their child when the child only responded in the other language, or because they felt left out when the other parent and the child had conversations in a language they did not understand. Braun and Cline (Citation2010) in their study of language practices and attitudes of trilingual families in England and Germany found that parents’ choices were influenced by linguistic background: parents who spoke one minority language other than the community language were more motivated to transmit their native languages than parents who spoke two minority languages.

Thus, earlier studies indicate that whether OPOL parents have positive attitudes and experiences hinges on a variety of factors including parents’ proficiency levels in the home languages, whether the parents themselves are bilingual, as well as children’s behaviours and attitudes towards the home languages. In line with these findings, Hoevenaars (Citation2021) observed, based on questionnaire data from 215 multilingual parents in the Netherlands, that parents were positive towards multilingualism, but at the same time considered raising children multilingually a challenging task. However, Hoevenaars (Citation2021) did not distinguish between families adopting different strategies, and neither did the earlier studies on parents’ attitudes and experiences reviewed above. In the current study, therefore, we further examined the questionnaire data by Hoevenaars (Citation2021) to see if parents’ attitudes and experiences differed between OPOL and Mixing families. We focused on families adopting these strategies because – in both types of family – multiple languages are spoken (unlike in ML@H families). This allowed us to compare parents in families in which languages were either or not separated by person. Given the previous mixed findings on parents’ attitudes towards language mixing (Ballinger et al. Citation2022; Piller and Gerber Citation2021), we aimed to see how attitudes and experiences may differ depending on the strategies adopted. We targeted the following three questions:

Do OPOL and Mixing parents prepare differently for raising their children multilingually?

Do OPOL and Mixing parents express different attitudes towards multilingual upbringing?

Do OPOL and Mixing parents report different experiences with multilingual upbringing?

Even though earlier literature did compare language transmission patterns and children’s language proficiency between OPOL and Mixing families (De Houwer Citation2007; Verhagen, Kuiken, and Andringa Citation2022) and looked at parents’ attitudes towards child multilingualism (Ballinger et al. Citation2022; Kircher et al. Citation2022; Piller and Gerber Citation2021), to the best of our knowledge, no earlier studies have compared attitudes towards multilingual child rearing between OPOL and Mixing families. Furthermore, parents’ experiences with language separation or mixing strategies might crucially depend on their own and their partner’s bilingual proficiency and their children’s behaviours (Barron-Hauwaert Citation2004; de Hoo Citation2014) and vary across countries or language communities (Braun and Cline Citation2010). For these reasons, we did not formulate hypotheses for the above questions, but considered them exploratory.

Method

Participants

The data for this study were originally gathered by Hoevenaars (Citation2021), using an online questionnaire targeted at parents and caregiversFootnote1 living in the Netherlands who raised children who were acquiring more than one language. A total of 333 participants started the questionnaire, and 204 of them completed it. Responses of 36 participants who partially completed the survey were included because they answered at least the questions about language use in the family; the remaining 93 participants were excluded because of insufficient data.Footnote2

Since the aim of our study was to compare families using an OPOL strategy and families using a Mixing strategy, each family’s reported language use was analyzed to identify whether they could be categorised as belonging to one of these groups. This categorisation was based on a set of questions in which participants were asked which languages each parent spoke to their children at home, and – if they reported speaking multiple languages – how often they spoke each language in percentages. To illustrate this, a family was considered as using an OPOL strategy if one parent spoke one language for 95% of the time or more and the other parent spoke another language for 95% or more. 73 families were included in the OPOL group. A family was considered as using a Mixing strategy if one or more parents reported speaking two or more languages to the children, with no language taking up more than 80%. The Mixing group consisted of 69 families. While these cutoff values are somewhat arbitrary, the cutoff of at least 95% used for the OPOL group was based on Verhagen, Kuiken, and Andringa (Citation2022). The cutoff of 80% for the Mixing group was more stringent than in that earlier study (where a cutoff of < 95% was used), so that the current groups were clearly different in terms of whether languages were separated or not, but still sufficiently large. An even lower cutoff (e.g. 60%) was not adopted for the Mixing group, as this would have reduced this group to 34 families. Due to the relatively high cutoff of 80% for the Mixing group, there was considerable variation across families in this group in the extent to which parents spoke each of the home languages. Additionally, in 30 of the Mixing families, only one parent reported speaking multiple languages. Out of these 30 families, there were seven single-parent families, eight families in which the non-mixing parent only spoke Dutch, and 15 families in which the non-mixing parent only spoke another language. Families with other language use patterns were excluded from the analysis. Of these, 24 used ML@H (both parents speaking a minority language for 95% or more of the time), 32 reported only speaking Dutch, and 42 were labelled as ‘Other’ because they reported large differences in language use between their individual children (N = 7) or did not fit the criteria for any other group (N = 35).

Of the 142 families in the sample, 8 participants (5 OPOL; 3 Mixing) commented in one of their responses that they did not live in the Netherlands or had not lived there (for some time) in the past. Specifically, 5 reported that they had moved to or away from the Netherlands, 1 that they had never lived in the Netherlands, and 2 that they were not living there when filling out the questionnaire. These families were excluded, because their social context may differ in unknown ways from the other families, which might affect their attitudes and experiences. The final sample included 134 families: 68 in the OPOL group and 66 in the Mixing group. Demographic information for these groups is shown in .

Table 1. Demographic Information for Participants in the OPOL and Mixing Families.

Materials

The questionnaire assessed parents’ experiences and attitudes towards raising their children multilingually. It contained multiple choice questions (including statements with Likert scales), as well as open-ended questions to allow participants to motivate their answers or elaborate on them. The questionnaire addressed various topics. First, participants were asked about the linguistic situation of their family (including the languages spoken by the parents to the children, and the languages spoken by the children). Then, they were asked to rate statements comparing a monolingual and multilingual upbringing, and answer multiple-choice and open-ended questions about their reasons for a multilingual upbringing, how they had prepared, and about various aspects of their experiences with multilingual upbringing. Finally, the questionnaire asked about any support and advice that parents might have received from different sources, such as children’s schools. For the current study, these final questions about external support and advice were not included because they were not relevant for our research questions. The full questionnaire is available through https://osf.io/dvmjw/.

Analysis

To address our research questions, various analyses were performed, depending on the type of data available. For multiple-choice questions for which multiple answers per participant were possible, frequencies were calculated and analyzed descriptively. Responses to open-ended questions were analyzed qualitatively. Questions with rating scales were analyzed through non-parametric tests (e.g. Wilcoxon rank sum test), using the package psych (Revelle Citation2019) in R version 3.6.2 (R Core Team Citation2019). Wilcoxon effect size r was calculated using the package rstatix (Kassambara Citation2021). Finally, for one of our research questions for which a large set of questionnaire items was relevant, we reduced our data through a factor analysis, the details of which will be described below.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through social media and personal contacts. Data collection took place between January and March of 2021. For each participating family, one parent completed the questionnaire, which was built through the software Qualtrics. Parents filled out the questionnaire in Dutch or English, and took on average 20 min to complete it. Participants received no compensation. Informed consent was obtained from each participant, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Amsterdam (number 2020-FGW_SLA-12332).

Results

In this section, results are reported for our three research questions in turn: Do OPOL and Mixing parents prepare differently for raising their children multilingually? Do OPOL and Mixing parents express different attitudes towards multilingual upbringing? And finally, do OPOL and Mixing parents report different experiences with multilingual upbringing?

Parents’ preparation for raising their children multilingually

Parents rated the following statements on a five-point scale (from ‘Not true at all’ to ‘Very much true’):

A.1: I made a conscious choice for a multilingual upbringing.

A.2: I prepared myself for my child(ren)’s language upbringing.

A.3: I made a plan for my child(ren)’s language upbringing.

Descriptive statistics are reported in . Note that in this table, and throughout the results section, the number of responses varies across questions because not all participants completed the full questionnaire, and because certain questions were conditional on participants’ previous answers (for example, only parents who stated they were concerned about their child’s development were asked to elaborate on their concerns).

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for Statements on Preparation (scale range 1-5) for the OPOL and Mixing Families.

Wilcoxon tests revealed that parents using OPOL assigned significantly higher ratings than parents who mixed languages to statement A.1, about their conscious choices for a multilingual upbringing (W = 1630, p < .001, r = .30). Note that the effect size r, which ranges between 0 and 1, is typically interpreted as follows: .10 – .30 indicates a small effect, .30 – .50 a moderate effect, and > .50 a large effect (Kassambara Citation2021). No significant differences between the groups were found for statements A.2 (W = 2258, p = .706, r = .03) and A.3 (W = 2326.50, p = .486, r = .06).

Furthermore, parents who reported having prepared for the upbringing or made a plan were asked when they had started doing this (question A.4). Responses to this question are shown in . After the responses were collapsed into two categories, ‘before birth of the first child’ and ‘after birth of the first child’, a chi-square test showed a significant association between parents’ language strategy and whether they had started planning early (χ²(1) = 6.24, p = .012). OPOL parents reported more often that they had started planning before the birth of their first child than Mixing parents.

Table 3. Moment at which Parents Started Preparing or Planning for the OPOL and Mixing Families.

Finally, parents were asked which methods or resources they had used to prepare (question A.5). shows the responses to this question. No clear differences between the groups appeared, although this could not be tested statistically, because participants could select multiple answers, yielding data that were not independent. Most commonly, participants had read information on the internet and/or relied on their own prior knowledge and experiences. Parents who answered ‘Other’ largely reported the ways in which they had used their own experiences or got advice from other parents (e.g. through a Facebook group).

Table 4. Methods and Resources for Preparation for the OPOL and Mixing Families.

Parents’ attitudes towards multilingual upbringing

Participants rated ten statements regarding their attitudes towards a multilingual upbringing on a five-point scale (from ‘Not true at all’ to ‘Very much true’, with a ‘No opinion’ option). These statements are listed in , along with descriptive statistics for the two groups. ‘No opinion’ answers were treated as missing data.

Table 5. Descriptive Statistics for Parent’s Ratings of Statements on Attitudes for the OPOL and Mixing Families (Scale Range 1-5).

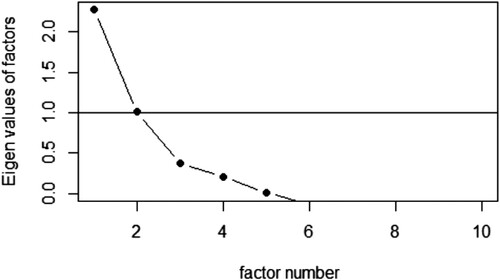

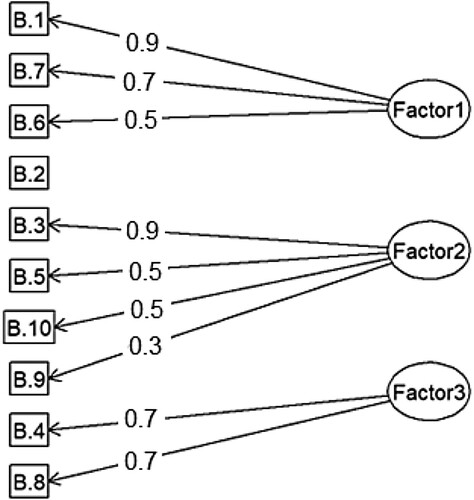

An exploratory factor analysis was performed on this data in promaxFootnote3 (Murphy Citation2021; R Core Team Citation2019) to identify any underlying structure in these statements and see whether the large number of statements could be reduced to a small number of dimensions, to allow for a smaller number of statistical tests (rather than comparing the groups on all ten statements separately). Eigenvalues extracted from the data, as well as a scree plot (see ), suggested that two or three factors could be identified. The three-factor solution outperformed the two-factor solution, based on the cumulative variance explained (0.46 for the three-factor model, 0.36 for the two-factor model). shows the results of the three-factor solution, including the factor loadings.Footnote4

When we related these factors to the statements in above, it appeared that the three factors each were associated with a different construct. Factor 1, based on B.1, B.6 and B.7, represented the amount of effort or difficulty associated with multilingual parenting that parents expressed; Factor 2, based on B.3, B.5, B.9 and B.10, reflected parents’ attitudes towards the value of multilingualism and a multilingual upbringing; and Factor 3, based on B.4 and B.8, reflected parents’ ideas about the degree of difficulty or risk of a multilingual upbringing for the child. B.2 did not distinctly correlate with any of the factors, and thus was not included in our further analysis.

Using the loadings from the factor analysis as weights, weighted averages were calculated for each factor for all participants. That is, a participant’s score on each statement associated with a factor was multiplied by its loading. The resulting scores for each statement of a factor were then summed and divided by the sum of the loadings to obtain the weighted average for that factor. Descriptive statistics for these scores are reported in .

Table 6. Descriptive Statistics for Weighted Averages on Attitude Factors for the OPOL and Mixing Groups (Scale Range 1-5).

Overall, scores were highest on the second factor, indicating that participants in general were positive towards multilingualism and multilingual upbringing. Wilcoxon tests demonstrated that parents who mixed languages scored significantly higher on the first factor than parents who used OPOL (W = 2531, p = .021, r = .20); they felt more strongly that a multilingual upbringing is difficult for parents and requires more attention and preparation than a monolingual upbringing. Parents who mixed languages also scored significantly higher on the second factor than parents who used OPOL (W = 2493.50, p = .033, r = .19): they felt more strongly that speaking multiple languages is important and that a multilingual upbringing is advantageous for a child. No significant difference was found for the third factor (W = 2132.5, p = .683, r = .04) concerning parents’ beliefs that a multilingual upbringing is more difficult for the child and increases the risk of language delays.

Parents’ experiences

Participants were asked whether, if they could redo their child’s upbringing, they would take the same approach again (question C.1). Total frequencies for ‘yes’ and ‘no’ answers were then calculated (see ). Note that the ‘yes but with changes’ option was left out, because this option could be interpreted as either a yes or a no.

Table 7. Frequencies of Responses About Using the Same Approach Again.

Although OPOL parents reported more often that they would take the same approach again than Mixing parents, a chi-square test based on the total yes and no responses showed no significant association (χ²(1) = 3.63, p = .057).

In an open question (C.2), parents were asked to explain their answer: specifically, if they could redo their child's upbringing, what would they want to change about their approach? Responses were analyzed qualitatively, in two steps. First, common or especially relevant themes were identified inductively, by inspecting participants’ responses. Subsequently, responses that included these themes were grouped. When one response included multiple themes, it was counted in each of these themes’ totals. For example, one parent responded ‘provide more opportunities to speak the minority language (Spanish); encourage my partner to be more consistent’, which was included under ‘More attention to a specific language’ and ‘More consistent’. Frequencies for each theme are shown in .

Table 8. Themes in Responses to Open Question About What Parents Would Want to Change.

Overall, the proportion of parents expressing that they would want to change certain things was larger in the Mixing group (58%, 38/66) than in the OPOL group (37%, 25/68). Many of the Mixing parents reported they would like to be more consistent and set clear rules: one parent, for example, indicated they would want ‘the father to speak only Italian, but discipline is lacking’. Another indicated: ‘I would raise [my children] bilingually in a more conscious way and don’t leave it so much to the children themselves’. This was often coupled with a wish to have dedicated more time and attention to a specific language: ‘[I would] be more consistent in speaking Swedish with the kids’; or ‘I would make a clear plan and speak no other language except the native language to the children’. Both themes were also expressed by parents in the OPOL group, though less frequently. For example, one of the OPOL parents said ‘I am too easily accepting a non-Dutch answer’, and another wished they could offer their children ‘even more Frisian, including reading, but unfortunately availability for that is limited’. This latter response suggested another theme: the desire for more resources such as books, schooling, and attention to literacy in a specific (non-majority) language. A few participants noted that they would have liked to include an additional language for their children. Only one participant from the OPOL group expressed a desire for more flexibility: they wished their partner would allow the children to occasionally address him in the other language.

For another aspect of parents’ experiences, participants rated, on a five-point scale from ‘Not true at all’ to ‘Very much true’, whether they felt concerned about the language development of their child (question C.3) and whether they felt confident when it comes to their child’s language upbringing (question C.4). Descriptive statistics are given in .

Table 9. Descriptive Statistics for Statements About Concern and Self-Confidence (scored 1-5) for the OPOL and Mixing Families.

Wilcoxon tests showed that OPOL parents were significantly more likely to report that they were self-confident about the linguistic upbringing of their children than parents who mixed languages (W = 1596, p = .027, r = .20). No significant difference between the groups was found regarding parents’ worries about their children’s language development (W = 2059, p = .956, r = .01). If parents reported that they were neutral, concerned or very concerned about their child’s language development (N = 15 OPOL; N = 17 Mixing), they were asked to further describe their worries in an open question (C.5). Responses to this question were qualitatively coded. Overall, numbers for all themes were low (between 0 and 5 responses per group for each theme), and no clear pattern emerged. Some parents were concerned about an actual language delay or disorder (N = 3 OPOL, N = 5 Mixing), others reported concerns about a possible future delay (N = 1 OPOL, N = 3 Mixing), or specific concerns about a smaller vocabulary (N = 3 OPOL, N = 1 Mixing), speaking and pronunciation (N = 2 OPOL, N = 3 Mixing), or reading and writing (N = 2 OPOL, N = 2 Mixing). Two themes were mentioned by OPOL parents only: the idea that learning multiple languages may be ‘too much’ for their children (N = 3) and the fear that children's proficiency in the two languages will not be balanced (N = 2).

Finally, parents were asked to indicate how they experienced multilingual parenting on 3 seven-point scales: from ‘not challenging’ to ‘challenging’ (question C.6), ‘not interesting’ to ‘interesting’ (C.7), and ‘not easy’ to ‘very easy’ (C.8). Descriptive statistics are reported in .

Table 10. Descriptive Statistics for Scales on Experience of Multilingual Parenting (scale range 1-7) for the OPOL and Mixing Groups.

Wilcoxon tests showed that Mixing parents rated a multilingual upbringing as significantly more challenging than OPOL parents (W = 2457, p = .029, r = .19). However, ratings on the ‘easy’ dimension did not differ significantly between the groups (W = 1630, p = .059, r = .17). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in how interesting parents found multilingual parenting (W = 1865.50, p = .453, r = .07), but note that both groups scored highest on this scale.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore whether parents who adopt a one-parent-one-language (OPOL) approach and parents who mix languages have different experiences with and different attitudes towards multilingual parenting. Questionnaire data from 134 multilingual families in the Netherlands were analyzed to address three questions: (1) Do OPOL and Mixing parents prepare differently for raising their children multilingually? (2) Do OPOL and Mixing parents express different attitudes towards multilingual upbringing? and (3) Do OPOL and Mixing parents report different experiences with multilingual upbringing?

Regarding the first question, the results showed that OPOL parents made a conscious choice to raise their children multilingually more often than parents from the Mixing group, although there was no significant difference between the groups on whether they reported having prepared or made a plan. OPOL parents were also more likely than Mixing parents to have started preparing for a multilingual upbringing before the birth of their first child. The findings that OPOL parents had more often made a conscious choice but did not prepare more might seem somewhat contradictory at first sight. However, a closer look at the data showed that parents in both groups reported to be rather neutral on the question of whether they had prepared or planned the multilingual upbringing of their child (i.e. mean values were close to 3 on a 1–5 scale). A possible explanation for the lack of a significant difference therefore is that there was simply not much to plan or prepare for parents.

As for the second question, results from a factor analysis showed that parents from the Mixing group believed more strongly than parents from the OPOL group that multilingual parenting is more difficult than monolingual parenting and requires additional effort from parents. Mixing parents also agreed more strongly than OPOL parents that multilingualism is valuable and important, although both groups considered multilingualism to be valuable overall. Generally, both groups did not believe that a multilingual upbringing imposes difficulty and risk on the child compared to a monolingual upbringing, and no significant difference between the groups was found on this factor.

Finally, regarding the third question, the results showed a clear (albeit not significant) difference such that 71% of the OPOL parents would take the same approach if they were to raise bilingual children again, while only 56% of the Mixing parents would. Also, almost two thirds of the Mixing parents reported a wish to change certain aspects, such as being more consistent and paying more attention to one of the languages. OPOL parents largely mentioned the same themes, but less commonly. OPOL parents were also significantly more self-confident about the linguistic upbringing of their children than Mixing parents, while Mixing parents indicated more often than the OPOL parents that they found multilingual parenting ‘challenging’.

The findings from the second and third research question that Mixing parents were more likely than OPOL parents to believe that multilingual parenting is difficult and to experience challenges may be surprising. After all, case studies of parents using OPOL have reported various challenges and difficulties that arise for these parents, such as trouble adhering to a rigid separation of languages and concern about insufficient quantity or richness of input in one of the languages (Barron-Hauwaert Citation2004; Tsushima and Guardado Citation2019). Experiences of parents using a Mixing strategy have not featured as much in previous research, but the results of the present study suggest that mixing languages does not reduce the challenges and difficulties that parents may experience when raising their children with multiple languages. While parents did not express specifically that they regretted mixing languages, many said they would want to give more attention to a certain language and be more consistent if they could repeat the process. This wish to be more consistent may be related to the popular idea that OPOL is ‘better’ than mixing languages (cf. Piller and Gerber Citation2021). The finding that many parents would want to emphasise particular languages more is reminiscent of Curdt-Christiansen’s (Citation2016) observation that parents in multilingual families often did not succeed in providing sufficient input in their minority languages, even though they wanted to pass these languages on to their children, because they ended up prioritising the majority language(s). Tsushima and Guardado’s (Citation2019) titular observation that multilingual parents wished for clear rules was also echoed in this study, especially – although not exclusively – by parents in the Mixing group who indicated that, if they could redo their child’s linguistic upbringing, they would want to set and adhere to rules and be more consistent.

A possible explanation of why OPOL parents were more confident and considered the multilingual upbringing of their children as less challenging than Mixing parents relates to the number of languages spoken in the two groups in our study: while all the OPOL families spoke two languages, about one third of the Mixing families reported three or more languages. Earlier research by Braun and Cline (Citation2010) has shown that parents in families where one minority language was spoken next to the community language considered themselves more effective in their efforts to bring up multilingual children than parents in families where more than two languages were spoken. Another factor that may have played a role is children’s age: the proportion of children who were below or just above school age (i.e. 0–5 years) was larger in the OPOL (50%) than in the Mixing group (35%). Earlier research has shown that parents often struggle more with raising their children multilingually after children have entered school and the community language becomes more important in the family (Anderson Citation2004; Braun and Cline Citation2010; Sheng, Lu, and Kan Citation2011).

This study has several limitations. First, the majority of parents in our sample were highly educated and thus did not accurately represent the population. The same applies to the fact that the most common languages in this study (aside from Dutch) were English, Spanish, French and Italian, whereas Turkish, Berber, Arabic and Polish are relatively common minority languages in the Netherlands (Schmeets and Cornips Citation2021). Thus, participants in this study spoke mainly higher-prestige languages to their children. Earlier research by Kircher et al. (Citation2022) has shown that parents’ attitudes towards child multilingualism differ between parents who speak a heritage language at home and parents who speak two community languages (e.g. French and English in Canada). The heritage language group held more positive attitudes related to social group identity, but less positive attitudes towards the value of multilingualism for status and economic opportunity. The association between heritage language status and parents’ attitudes may be due to differences in language prestige. However, the exact effects of (perceived) prestige on parents’ attitudes towards multilingual upbringing could differ depending on social and linguistic context, and on the type of attitudes studied. Future studies should include more families who speak lower-prestige languages, to see whether language prestige mediates any relationships between the strategies adopted and parents’ beliefs, attitudes and experiences.

A second limitation of our study relates to specific properties of the groups. The division of participants into groups was not based on parents’ reported language strategy (because they were not explicitly asked whether they used OPOL, etc.), but on their reported language use. While reported language use likely leads to more uniform groups than reported language strategy, because a term such as OPOL can mean different things to different people, we must still be cautious in trusting the accuracy of this language use data. De Houwer and Bornstein (Citation2016) found that in their sample of bilingual mothers, self-reported language use mostly matched observed language use, although some mothers were observed to mix languages occasionally when they had claimed not to do so. In our study, one may wonder whether parents’ estimates of language use might have been more reliable at the higher or lower ends of the scales than closer to the middle, such that a difference between 95% and 100% is more likely to reflect an actual difference in language use than a difference between 75% and 80%. If this were true, parent's estimates were generally more accurate in the OPOL group as opposed to the Mixing group. Another difference between the two groups that might have affected the results in unknown ways is that the Mixing group in this study was relatively heterogeneous because it included families in which both parents used multiple languages and families in which only one parent did, and the total number of languages used in the Mixing families also ranged from two to as many as five. These differences likely correlated with differences in the amount of language input children were exposed to, and since these, in turn, relate to children’s language development, they may have impacted on parents’ attitudes and experiences. Future research should consider such within-group differences in degree of mixing and amount of input to gain a more complete picture of how such factors might mediate any associations between family language strategies and parental attitudes and experiences.

Third, and as noted in the Participants section, 8 participants (5 in the OPOL group and 3 in the Mixing group) noted in one of their responses that they currently did not live in the Netherlands, or had not always lived there in the past. Since their social context probably differed from that of participants who raised their children in the Netherlands, which might affect their attitudes and experiences, they were excluded. However, participants were not explicitly asked in the questionnaire whether they lived in the Netherlands with their children, and it is possible that the sample contained other participants who did not incidentally reveal this.

A final limitation is that we did not assess parents’ proficiency levels in the home languages, and thus do not know whether parental proficiency differed between the groups. It is possible that some of our findings, for example with respect to whether parents made a conscious choice for a multilingual upbringing, were due to parents not being proficient in a language. Future work could assess the extent to which parents are proficient in the languages spoken at home. Such work could also investigate how the degree to which parents themselves are multilingual relates to their attitudes and experiences, as earlier research has proposed that parents who are multilingual tend to view child multilingualism more positively (Surrain and Luk Citation2019).

In conclusion, this exploratory study showed that there are differences between parents who use OPOL and parents who mix languages regarding their experiences with and attitudes towards raising children multilingually. Whether these differences are the result of their choice of family language strategy – or the other way around – is not clear. Future research could investigate the relationships between language strategy, attitudes and experiences more deeply, for example by following families over time, or exploring more subtle attitudes, beliefs and behaviours within OPOL and Mixing families.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Sible Andringa for his contributions to the initial version of our questionnaire. We thank all participants for sharing their ideas and experiences, as well as for spreading the questionnaire within their networks.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The dataset associated with this study is available at https://osf.io/dvmjw/ (doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/DVMJW).

Notes

1 Throughout this paper, the term ‘parents’ is used to refer to parents and other caregivers. Participants were asked to choose a label for each of the family’s parents or caregivers. Out of the 134 families in the sample, 3 families selected labels other than ‘mother’ or ‘father’. One of these families used first names as labels; the others included one or two grandparent labels alongside a mother and father.

2 Specifically, for the responses that were discarded, respondents had not fully filled out the questions about language use in the family, and could therefore not be included in one of the groups; or they had answered these questions but not others, such that their inclusion would not add any data.

3 Promax was used as the rotation because it is well-suited to datasets in which the factors are not independent from one another (Murphy Citation2021). There were indeed correlations between the factors in our data (in the three-factor model): r = -.44 for factors 1 and 2 and r = -.36 for factors 1 and 3.

4 In the results of the two-factor analysis, which fitted the data slightly less well, factor 1 and 3 were combined into a single factor which thus expressed difficulties/downsides more generally, and factor 2 stayed the same.

References

- Anderson, R. 2004. “First Language Loss in Spanish-Speaking Children: Patterns of Loss and Implications for Clinical Practice.” In Bilingual Language Development and Disorders in Spanish–English Speakers, edited by B. Goldstein, 187–212. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

- Bail, A., G. Morini, and R. S. Newman. 2015. “Look at the Gato! Code-Switching in Speech to Toddlers.” Journal of Child Language 42 (5): 1073–1101. doi:10.1017/S0305000914000695.

- Ballinger, S., M. Brouillard, A. Ahooja, R. Kircher, L. Polka, and K. Byers-Heinlein. 2022. “Intersections of Official and Family Language Policy in Quebec.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 43: 614–628. doi:10.1080/01434632.2020.1752699.

- Barron-Hauwaert, S. 2004. Language Strategies for Bilingual Families: The one-Parent-one-Language Approach. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Blom, E., O. Oudgenoeg-Paz, and J. Verhagen. 2018. “Wat als ouders talen mixen? Een onderzoek naar de relatie tussen mixen van talen door ouders en de taalvaardigheid van meertalige kinderen [What if parents mix languages? A Study Into the Relation Between Parental Mixing and Multilingual Children’s Language Proficiency].” Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Logopedie 90: 18–25.

- Braun, A., and T. Cline. 2010. “Trilingual Families in Mainly Monolingual Societies: Working Towards a Typology.” International Journal of Multilingualism 7: 110–127. doi:10.1080/14790710903414323.

- Byers-Heinlein, K. 2013. “Parental Language Mixing: Its Measurement and the Relation of Mixed Input to Young Bilingual Children’s Vocabulary Size.” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 16: 32–48. doi:10.1017/S1366728912000120.

- Curdt-Christiansen, X.L.. 2013. “Negotiating Family Language Policy: Doing Homework.” In Successful Family Language Policy: Parents, Children and Educators in Interaction, edited by M. Schwartz and A. Verschik. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Curdt-Christiansen, X. L. 2016. “Conflicting Language Ideologies and Contradictory Language Practices in Singaporean Multilingual Families.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37: 694–709. doi:10.1080/01434632.2015.1127926.

- de Hoo, M. L. 2014. Taalbeleid binnen het gezin in Friesland. Onderzoek naar de keuzes en ideeën van ouders over de talige opvoeding [MA thesis] [Language policy within the family in Frisia. Research into parents’ choices and ideas about linguistic upbringing]. University of Amsterdam.

- De Houwer, A. 1999. “Environmental Factors in Early Bilingual Development: The Role of Parental Beliefs and Attitudes.” In Bilingualism and Migration, edited by G. Extra, and L. Verhoeven, 75–96. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- De Houwer, A. 2007. “Parental Language Input Patterns and Children’s Bilingual use.” Applied Psycholinguistics 28: 411–424. doi:10.1017/S0142716407070221.

- De Houwer, A. 2009. “Bilingual First Language Acquisition, Bristol.” Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters 2009, doi:10.21832/9781847691507.

- De Houwer, A., and M. H. Bornstein. 2016. “Bilingual Mothers’ Language Choice in Child-Directed Speech: Continuity and Change.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37: 680–693. doi:10.1080/01434632.2015.1127929.

- Döpke, S. 1992. One Parent - one Language: An Interactional Approach. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Grosjean, F. 2012. Bilingual: Life and Reality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hoevenaars, E. F. 2021. Meertalig opvoeden: Ideeën en ervaringen van ouders [MA thesis] [Multilingual parenting: Ideas and experiences of parents]. University of Amsterdam.

- Kassambara, A. 2021. rstatix: Pipe-Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests [version 0.7.0]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rstatix.

- King, K. A. 2016. “Language Policy, Multilingual Encounters, and Transnational Families.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37: 726–733. doi:10.1080/01434632.2015.1127927.

- Kircher, R., E. Quirk, M. Brouillard, A. Ahooja, S. Ballinger, L. Polka, and K. Byers-Heinlein. 2022. “Quebec-based Parents’ Attitudes Towards Childhood Multilingualism: Evaluative Dimensions and Potential Predictors.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 41: 527–552. doi:10.1177/0261927X221078853.

- Lanza, E. 2007. “Multilingualism and the Family.” In Handbook of Multilingualism and Multilingual Communication, edited by P. Auer, and L. Wei, 45–68. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Murphy, P. J. 2021. Exploratory factor analysis in R. https://rpubs.com/pjmurphy/758265.

- Paradis, J., and F. Genesee. 1996. “Syntactic Acquisition in Bilingual Children: Autonomous or Interdependent?” Studies in Second Language Acquisition 18: 1–25. doi:10.1017/S0272263100014662.

- Piller, I., and L. Gerber. 2021. “Family Language Policy Between the Bilingual Advantage and the Monolingual Mindset.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 24: 622–635. doi:10.1080/13670050.2018.1503227.

- R Core Team. 2019. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [version 3.6.2]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Revelle, W. 2019. psych: Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research [version 1.9.12]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych.

- Roeleveld, A. 2016. Lekentheorieën en taalideologieën bij meertalig opvoeden [MA thesis] [Lay theories and language ideologies in multilingual upbringing]. University of Amsterdam.

- Romaine, S. 1995. Bilingualism (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Schmeets, H., and L. Cornips. 2021. Talen en dialecten in Nederland: Wat spreken we thuis en wat schrijven we op sociale media? [Languages and Dialects in the Netherlands: What Languages do we Speak at Home and What Languages do we use on Social Media?] Centraal Bureau Voor de Statistiek. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/longread/statistische-trends/2021/talen-en-dialecten-in-nederland.

- Sheng, L. I., Y. Lu, and P. F. Kan. 2011. “Lexical Development in Mandarin–English Bilingual Children.” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 14: 579–587. doi:10.1017/S1366728910000647.

- Slavkov, N. 2017. “Family Language Policy and School Language Choice: Pathways to Bilingualism and Multilingualism in a Canadian Context.” International Journal of Multilingualism 14 (4): 378–400. doi:10.1080/14790718.2016.1229319.

- Surrain, S., and G. Luk. 2019. “The Perceptions of Bilingualism Scales: Development and Validation Using Item Response Theory.” PsyArXiv, doi:10.31234/osf.io/s32zb.

- Tokuhama-Espinosa, T. 2001. Raising Multilingual Children: Foreign Language Acquisition and Children. Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey.

- Tsushima, R., and M. Guardado. 2019. ““Rules … I Want Someone to Make Them Clear”: Japanese Mothers in Montreal Talk About Multilingual Parenting.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education 18 (5): 311–328. doi:10.1080/15348458.2019.1645017.

- Verhagen, J., F. Kuiken, and S. Andringa. 2022. “Family Language Patterns in Bilingual Families and Relationships with Children’s Language Outcomes.” Applied Psycholinguistics 43: 1109–1139. doi:10.1017/S0142716422000297.

- Wilson, S. 2021. “To Mix or Not to Mix: Parental Attitudes Towards Translanguaging and Language Management Choices.” International Journal of Bilingualism 25: 58–76. doi:10.1177/1367006920909902.