ABSTRACT

Hearing parents who endeavour to learn American Sign Language (ASL) to communicate with their deaf children are a unique but understudied population of adult language learners. In this study, we assessed the expressive and receptive ASL skills of hearing parents of deaf children (n = 55). Expressive ASL skills were evaluated through elicited language samples, and scored using adapted rubrics from the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. For a subset of participants (n = 20), an additional language sample was obtained and coded for lexical and grammatical features of ASL. Receptive ASL skills were measured using the ASL-Comprehension Test. Across measures, participants demonstrated language skills in the beginner to intermediate range. Parents’ signing samples showed a range of ASL linguistic features including classifier constructions. Our findings suggest that hearing parents can learn ASL and should be encouraged to do so to support language development in their deaf children.

Introduction

Most deaf children are born to hearing parents with no prior knowledge of a sign language. There are many benefits to hearing parents learning American Sign Language (ASL) for their deaf children, which is a fully accessible language for sightedFootnote1 deafFootnote2 children. Families who learn sign language with their deaf child report increased communication between the deaf child and their family (Calderon Citation2000; Oyserman and de Geus Citation2021). Although the benefits to improved overall communication are documented, there has been some concern that hearing parents, as adult second-language (L2) learners, cannot learn ASL to a degree of fluency that will benefit their child's language development (e.g. Knoors and Marschark Citation2012). However, recent evidence suggests hearing parents who are learning to sign can support their child's ASL development (Berger et al. Citation2024; Caselli, Pyers, and Lieberman Citation2021). Parents who have learned ASL highly value ASL as one of their family's and child's languages, and they report a range of experiences learning from feeling challenged and under-resourced to finding it relatively easy and feeling supported (Chen Pichler Citation2021; Lieberman, Mitchiner, and Pontecorvo Citation2024). Hearing parents differ from other L2 learners in their reasons and motivation for learning ASL (Chen Pichler Citation2021; Snoddon Citation2014), and their access to classes and other resources for learning. As a result, there is likely wide variation in the ASL skills of hearing parents, but this has rarely been studied systematically. In the current paper, we aim to characterise the receptive and expressive ASL skills of a group of hearing parents who have committed to learning ASL to communicate with their deaf child.

Literature review

L2M2 adult language acquisition

Hearing parents who learn ASL for their deaf child take on a challenging task of learning a new language in adulthood. Decades of research on adult second-language learning have established that several elements of linguistic proficiency, such as phonology and grammar (Birdsong Citation2006; Hartshorne, Tenenbaum, and Pinker Citation2018), decline with age of acquisition in adulthood. Adult second-language acquisition is influenced by many factors, and the outcomes are highly variable both in learning trajectory and in ultimate attainment (Sanz Citation2005). Furthermore, hearing adults learning ASL are learning a language in a new modality. They can be classified as L2M2 learners as they are learning a second language (L2, Ln) in a second modality (M2), signed rather than spoken, which poses additional challenges to the second-language acquisition process.

Typically, second-language learners transfer knowledge from the languages they know to the new language, and this transfer can facilitate learning in languages that share similar phonology or grammatical patterns (Ringbom Citation2007). Thus it is easier to learn a language that is more similar to one's previously acquired language than one that is more distantly related. The signed modality reduces the opportunity for transfer across phonological and grammatical structures. Sign languages use different articulators than spoken languages (hands and face) so there is no opportunity for transfer of phonological patterns from the first language (see Chen Pichler & Koulidobrova, Citation2016 for a discussion). The use of three-dimensional space for grammatical purposes differs from spoken languages as well, so learners also may not be able to draw on the grammatical features of their first language (Boers-Visker and Pfau Citation2020; Schönström and Holmström Citation2022). Fingerspelling (the spelling of an English word using the manual alphabet in ASL) can be difficult for L2 learners (Geer and Keane Citation2018) as well. In interviews with parents learning ASL, Chen Pichler (Citation2021) found that parents reported grammatical elements of sign language such as word order and classifier constructionsFootnote3 to be the most challenging to learn. Several elements of learning a language in a new modality pose unique challenges to hearing learners of sign languages.

Hearing parents as a unique population of L2M2 learners

While all hearing adult learners of ASL face a similar task of learning a language in a new modality in adulthood, hearing parents differ from typical students of ASL. The majority of hearing adults who learn sign language do so for personal growth or pre-professional purposes (e.g. future teachers of the deaf or sign language interpreters) (e.g. Beal Citation2020). ASL is the fourth most studied language in the US, with 100,000–200,000 learners in high schools, colleges and universities (Looney & Lusin, Citation2018). In contrast, parents often do not learn through formal means in college or university classes. Parents use a variety of resources to learn, including classes offered for parents and families through their child's school or early intervention programme, Deaf Mentoring programmes, informal interaction with deaf adults, online or internet resources, and other sources (Lieberman, Mitchiner, and Pontecorvo Citation2024).

Part of the reason parents don't primarily learn through college-level courses is due to limited resources (i.e. time, money, and access to classes) (Lieberman, Mitchiner, and Pontecorvo Citation2024), but another reason is that college courses do not necessarily meet their needs (Oyserman and de Geus Citation2021; Snoddon Citation2015; Zarchy and Geer Citation2023). Hearing parents who learn ASL for their deaf child have unique communicative needs relative to other hearing adult ASL students. Most college-level courses focus on conversational ASL vocabulary and grammar that supports adult interaction. In contrast, the vocabulary and communicative interactions most urgent for hearing parents are related to young children's daily routines and environments. Parents also need instruction in early interactional strategies such as how to provide choices, or how to engage in shared book reading (see Lillo-Martin, Gale, and Chen Pichler Citation2023; Napier, Leigh, and Nann Citation2007; Zarchy and Geer Citation2023 for further discussion), as well as visual communication strategies such as how to get their deaf child's attention (Napier et al., Citation2007). Importantly, these communicative needs are urgent, as parents seek to provide immediate and accessible input to their deaf child and attain successful communication with their child on a daily basis (Oyserman and de Geus Citation2021; Snoddon Citation2014) Parents’ unique communicative needs and varied learning mechanisms mean that their language learning trajectories and outcomes might differ from the more widely studied population of hearing learners of sign languages.

Measuring signing skills in hearing parents

Because many hearing parents learn ASL in non-traditional settings (e.g. early childhood classes, tutoring, mentor programmes, online classes), these classes typically do not include assessment or grading, thus the ASL skills of hearing parents remain largely unassessed. Only a few studies have measured the signing skills of hearing parents. Oyserman and de Geus (Citation2021) report the signing skills from a parent sign language class teaching Sign Language of the Netherlands (SLN). This class was taught and evaluated in alignment with the Common European Framework of References (CEFR) and was targeted at parents who had already completed several SLN courses. The parents in their sample achieved high beginner to low intermediate skills. In the United States, Berger et al. (Citation2024) assessed hearing parents’ ASL skills by eliciting a language sample, which they scored using a rubric designed for placing hearing L2 ASL students into ASL courses. The majority of the hearing parents, who varied widely in their length and amount of ASL instruction, had expressive language samples that were equivalent to L2 college students with two to four semesters of ASL. Measuring parent ASL skills contributes to our understanding of how parent skills impact deaf children's language development. In addition, understanding L2 skills in this population with unique motivation and access to resources can broaden our understanding of the factors that contribute to L2 learning outcomes.

Goals of the current study

In the current study, we assessed ASL receptive and expressive skills in a sample of hearing parents of deaf children. We had two main research goals. One was to provide a high-level description of the receptive and expressive ASL skills of hearing parents who are learning ASL. To this end, we analysed performance on a normed ASL receptive test (the ASL Comprehension Test; ASL-CT, Hauser et al. Citation2016), and elicited a language sample consisting of a video retelling of a wordless cartoon, which we scored using a set of modified CEFR rubrics. With the expressive and receptive measures, we investigated whether expressive and receptive skills were correlated, and we determined whether the length of time that parents had been learning ASL predicted their receptive or expressive skills. The second research goal was to characterise the expressive skills of hearing parent ASL learners. To achieve this, we conducted an in-depth analysis of parent expressive skills using the video retelling as well as an additional expressive language sample, in a subset of the original sample. Our in-depth analysis allowed us to identify specific features of parent expressive ASL skills in detail, including vocabulary diversity, classifier constructions, fingerspelling, and errors. We also compared the two language sample prompts (video retelling and family narrative) to see whether there were differences in CEFR scores or linguistic features based on the prompt.

Methods

Data collection

All study materials and recruitment materials were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Boston University protocol 4482E. Participants were drawn from two larger studies: one group (n = 20) was originally recruited for a survey of attitudes and experiences among hearing parents who were learning ASL to communicate with their deaf child (Lieberman, Mitchiner, and Pontecorvo Citation2024). Participants in that study completed an online survey about their experiences learning ASL. All participants were invited to complete additional study tasks measuring expressive and receptive ASL skills, which we report in this paper. The children in that study were between 3 and 21 years old. The second group (n = 35) was drawn from a study of vocabulary development in deaf children of hearing parents (Berger et al. Citation2024). Participants recruited for that study completed a demographic survey and vocabulary report for their deaf child, and opted to complete the additional ASL expressive and receptive measures. The children in that study were between birth and 5 years old.

Recruitment for both of the larger studies was conducted through social media and snowball sampling (see Lieberman, Mitchiner, and Pontecorvo Citation2024 and Berger et al. Citation2024 for more details). Data was collected over multiple rounds of recruitment over a period of three years. Participants completed the consent and study tasks online at their own pace and were given an Amazon gift card to thank them for participation.

Participants

Participants were 55 hearing parents who had a deaf or hard of hearing child between the ages of 0–21 years (Median = 3.75; M = 5.45, SD = 5.80). The parents all reported that they were learning ASL to communicate with their children. We included one participant whose adult child was outside of the study age range (32yo), as their results did not differ from the group.

Parents had been learning ASL for 0.25–34.0 years (M = 4.42, SD = 5.34). Participants were predominantly White (parents = 100% of those who reported race; children = 97% of those who reported race); had a college degree, and lived across the US.

Participants recruited from two different studies completed two different demographic questionnaires (full questionnaires can be found in the appendix of Lieberman, Mitchiner, and Pontecorvo Citation2024 and Berger et al. Citation2024). There were subtle differences in the demographic surveys. Regarding race and ethnicity, one demographic survey asked parents to report their own identity, while the other survey asked parents to report their child's identity. Participants in Lieberman, Mitchiner, and Pontecorvo (Citation2024) reported how long they had been learning ASL. Participants in Berger et al. (Citation2024) did not provide this information. However, parents did report how long their child had been learning ASL. For the current analysis, we use the length of time that the child has been learning ASL as a proxy for the length of time parents have been learning ASL. Demographic information about the participants is provided in .

Table 1. Demographic information.

Study tasks

All parents (n = 55) submitted a short video of themselves retelling a 45 s segment of the wordless Pixar cartoon, ‘Lifted,’ using ASL. All videos were scored using rubrics from the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). Most participants (n = 52) also completed an ASL receptive skills task, the American Sign Language Comprehension Test (ASL-CT; Hauser et al. Citation2016). A subset of parents (n = 20) also submitted a second expressive language sample consisting of a 1–2 min video of themselves signing about a favourite family memory. For this subset of participants, both the video retelling and the family narrative prompts were coded in ELAN for a range of linguistic features. The measures are described below.

Receptive ASL measure

Participants completed the American Sign Language Comprehension Test (ASL-CT) (Hauser et al. Citation2016), a standardised 30-question multiple-choice test that is completed online. Scores were calculated as the number of questions correct out of 30 questions. The ASL-CT assesses comprehension of complex morphology, referential shift, facial expressions, and referents in signing space. It has been normed on hearing L2 signers as well as deaf signers with early ASL exposure and later ASL exposure (Hauser et al. Citation2016). While the ASL-CT was designed for highly proficient ASL signers, Hall and Reidies (Citation2021) found that it still detected variation among more novice L2 signers. Participants completed the ASL-CT online at their own pace. ASL-CT scores were converted to a percent correct for analysis.

Expressive language samples

For the video retelling, all participants were provided with a 45-second clip from the Pixar short Lifted, and asked to describe the clip in ASL. Participants filmed themselves at home using a smartphone, computer, or camera, and uploaded their video to a secure website. The video retelling prompt was designed to elicit features of ASL including classifiers, constructed action and role shift, in order to determine the extent to which parents incorporated grammatical features of ASL. For the family narrative, a subset of participants was asked to describe a favourite family memory using ASL. The family narrative prompt was designed to elicit narrative storytelling in ASL drawing on people, places, and activities in participants’ lives.

Expressive language sample scoring

The Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) is a tool used to teach and evaluate second-language learners.Footnote4 It was developed with a plurilingualism framework, which centres the individual as a multilingual who makes use of all their languages to have productive communicative interactions. The CEFR has been specifically adapted to the evaluation of sign languages (Leeson et al. Citation2016), with the descriptions of competencies specific to language in the visual modality. The CEFR has also been implemented in curriculum design for sign language classes designed for parents with deaf children (Snoddon Citation2015). Oyserman and de Geus (Citation2021) used the CEFR to evaluate hearing parents who were learning sign language in a classroom setting. The theoretical framework of plurilingualism, the existence of specific reference levels for sign languages, and its previous use with hearing parents who were learning a sign language informed our choice of the CEFR for the evaluation of expressive skills, while acknowledging that the limited length and scope of our language samples leads us to interpret the results cautiously.

The CEFR groups language learners into three general levels: A (novice users), B (independent users), and C (proficient users). Each level has two steps, so the 6 levels of the CEFR are A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, and C2. Evaluation rubrics describe competencies written as ‘can do statements’ for each level. The CEFR is typically used in a classroom setting, implemented by a teacher familiar with the student's language skills.

For our analysis, we selected specific rubrics from the CEFR, and adapted them to the type of expressive language samples we obtained. We applied a subset of the CEFR rubrics to the language samples provided by the participants. Specifically, we applied four rubrics to each of the two expressive samples: Overall Production, Vocabulary Control, Grammatical Accuracy, and Fluency. Each video was scored on these four rubrics separately, with a score from A1 to C2. A single score was then derived for each video by taking the most common score out of the four rubrics, or the lower score if the rubrics were evenly split between two scores (for example, if a parent scored A2/A2/B1/B1, that parent was assigned an overall score of A2). For statistical analysis, the CEFR scores were converted from the 6-tier scale (A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2) to a numerical scale of 1–6.

All videos were scored by deaf, ASL-signing research assistants. They were provided with the original CEFR rubrics (Leeson et al. Citation2016), as well as rubrics that we adapted to the video retelling prompt used in this study (see the adapted rubrics at https://osf.io/qjmek/).

A subset (25%, n = 14) of the video retelling samples was scored by a second research assistant to assess reliability. There was a high degree of inter-rater reliability: in nearly all cases (13 out of 14), the videos were scored with either the same overall score, or an overall score that differed by one CEFR level (e.g. A1 vs A2). The original score was maintained in these situations. One video score differed by two levels, and the original score was also maintained based on the judgment of a third viewer (the first author). The 20 family narrative videos were also scored by two research assistants and they met the same criteria (i.e. scores were within one CEFR level) in 19/20 of the videos, and the original score was maintained.

Linguistic analysis

We also were interested in a more fine-grained description of the ASL usage of hearing parents. To approach this question, we coded a subset of videos (n = 20 video retelling, n = 20 family narrative) for linguistic features using the video annotation system ELAN (Crasborn and Sloetjes Citation2008). Videos were coded by deaf or hearing research assistants fluent in ASL.

Signs were noted by providing one gloss for each individual sign, using the SignBank glossing system (Hochgesang, Crasborn, and Lillo-Martin Citation2018). SignBank includes lexical signs, depicting signs (handshapes used in classifier constructions), and conventions for unintelligible signs and common gestures. When the SignBank gloss differed from the meaning of the sign in context, then we wrote a gloss with the intended meaning to better represent the signer's intended meaning. An approximate English translation was provided on a separate tier in ELAN at the utterance level to facilitate written comprehension of the transcripts. Following the ASL gloss and English translation, we coded for salient grammatical features of ASL including classifier constructions, referential shift, and spatial verb agreement. For example, we identified each time a classifier was used to depict an event. As another example, when a participant briefly took on the character of an alien moving a control by showing both the facial expression and miming the action of moving the control, this action was labelled as a Referential Shift. These grammatical features were coded regardless of whether or not they were used correctly. Finally, we coded all errors in sign production and categorised them as either phonological or lexical. Phonological errors consisted of signs that were produced with significant variation in one or more parameters from the citation form in SignBank (Hochgesang, Crasborn, and Lillo-Martin Citation2018) based on the judgment of the coder. Lexical errors occurred when signs with an incorrect meaning were produced, which was determined from the context or the participant's mouthing. Unintelligible signs were marked as lexical errors.

Results

We first present scores on the receptive and expressive ASL tasks for the full participant sample. Next, we determine whether receptive and expressive skills were correlated, and investigate which demographic variables predicted parent ASL skills. Finally, we present an in-depth analysis of productive ASL skills for the subset of participants who completed two expressive samples.

Receptive ASL scores

Most participants (n = 52) completed the ASL-CT. Raw scores were calculated as the total number of correct items out of a possible 30 items, and then converted to percent correct. Participants’ scores ranged from 20% to 80% (mean = 56.90%, SD = 14.34%).

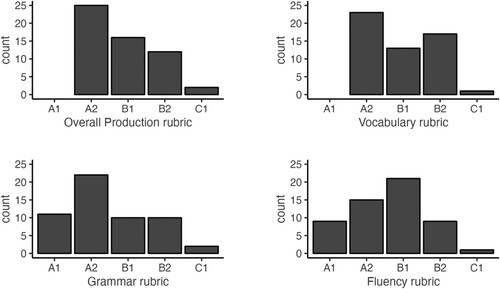

We compared the mean score from the current sample to two previously reported samples of hearing ASL students reported in Hauser et al. (Citation2016) and Hall and Reidies (Citation2021) (). Mean scores among the current sample were numerically lower than those in the original norming sample, but higher than those in Hall and Reidies's recent sample.

Figure 1. ASL Comprehension test (ASL-CT) Scores.

Note: This figure shows the mean and distribution of ASL-CT scores in the current sample, alongside hearing ASL student group means of the ASL-CT norming study (Hauser et al. Citation2016), and another study of ASL L2 learners (Hall and Reidies Citation2021).

Expressive ASL scores

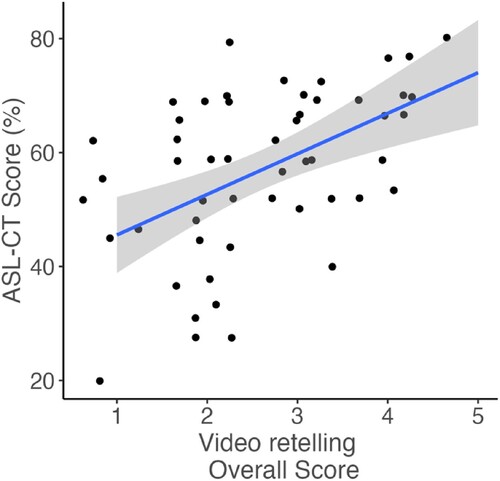

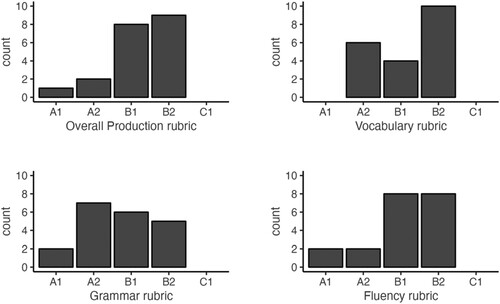

We scored all participants using four CEFR rubrics on the video retelling expressive language sample. Each participant received four individual scores, which were then used to derive an overall score. Across all participants, overall CEFR scores ranged from A1 through C1 (no participants scored at the C2 level) (). Twenty-eight participants were in the A level (Basic users), twenty-six were in the B level (Independent users), and 1 was in the C level (Proficient users).

Figure 2. Expressive language sample: Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) Scores.

The CEFR scores were then converted from the 6-tier scale (A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, and C2) to a numerical scale of 1-6. We calculated numerical scores for each of the individual rubrics to use for statistical analysis. Scores on each of the rubrics were as follows: Overall Production (M = 2.84, SD = 0.90), Vocabulary (M = 2.93, SD = 0.91), Grammar (M = 2.46, SD = 1.12), and Fluency (M = 2.60, SD = 1.01). The distribution of individual scores on these rubrics is displayed in .

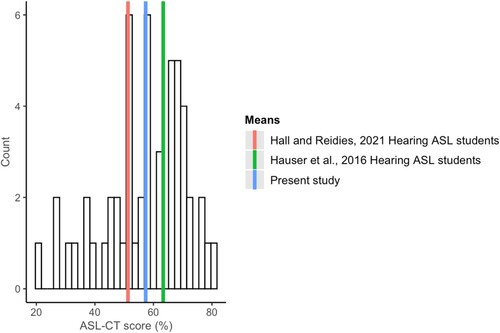

Relationship between expressive and receptive scores

To determine whether participants’ expressive and receptive scores were correlated, we calculated a Spearman's rank correlation between ASL-CT score (percent correct) and overall CEFR score (ranging from 1 to 6) (). As expected, participants’ scores on the ASL-CT were positively correlated with CEFR rubric expressive scores (r = 0.49, p < 0.01); participants with higher receptive skills also had higher expressive skills.

Predictors of ASL skill

Scores on the receptive and expressive ASL tasks varied widely among individual parents. We predicted that the length of time the parent had been learning ASL would correlate with their scores. Surprisingly, the length of time the parent had been learning ASL did not predict either their expressive score on the CEFR (Spearman's rho = 0.27; p = 0.06), or their receptive score on the ASL-CT (Spearman's rho = 0.14; p = 0.35). We repeated the correlations using the child's current age. We predicted that parents of older children would have more language experience and hence higher scores. A Spearman's rank correlation between the child's age and the parent's CEFR score of the expressive video was significant: (r = 0.32; p = 0.02), but Spearman's rank correlation between the child's age and the parent's ASL-CT score (r = 0.08, p = 0.56) was not significant.

Second video prompt

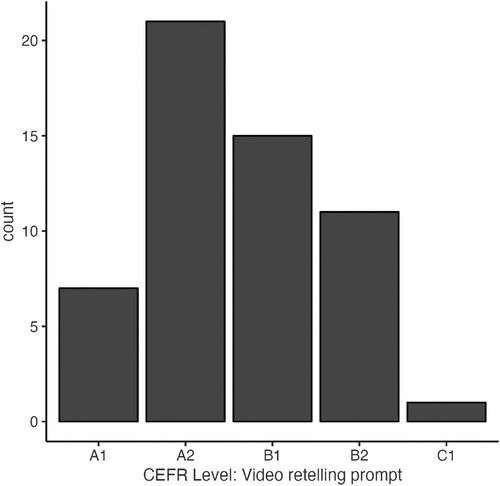

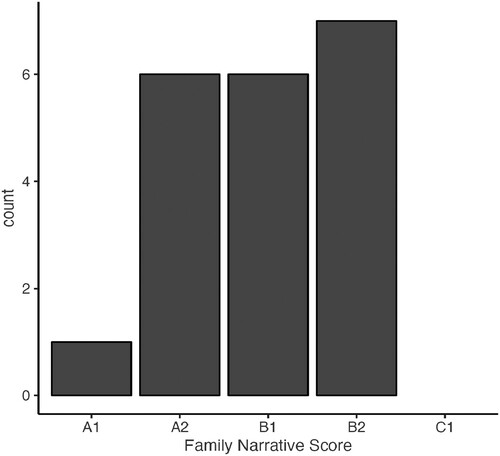

A family narrative was obtained as a second expressive sample from a subset of participants (n = 20). We first evaluated these videos by applying the same approach as we did with the video retelling: we scored them on four individual rubrics from the CEFR and then used those to generate an overall CEFR score.

Overall CEFR scores for the family narrative ranged from A1 to B2 (). Seven participants were in the A level (Basic users), and 13 were in the B level (Independent users). We converted the CEFR score to a numerical value and determined the mean score on each individual rubric. The average score for each rubric was: Overall Production (M = 3.25, SD = 0.85), Vocabulary (M = 3.2, SD = 0.89), Grammar (M = 2.7, SD = 0.98), Fluency (M = 3.1, SD = 0.97). shows the distribution of scores for each of the individual rubrics.

Figure 5. Second expressive language sample: common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) Scores (n = 20).

Figure 6. Expressive language sample: CEFR scores across four rubrics in family narrative prompt (n = 20).

We compared participants’ scores for the video retelling and family narrative for those who completed both (n = 20). As expected, participant's scores on the two videos were highly correlated with a Spearman's rank correlation (r = 0.69, p = 0.002).

Linguistic analysis

Expressive language samples from a subset of parents (n = 20) were coded for linguistic features in ELAN. Data from ELAN was exported and analysed in R for several summary measures. For each video, we calculated the following: the total number of signs used, the number of unique signs, the ratio of lexical signs to classifiers, degree to which parents used fingerspelling, and the number and frequency of phonological and lexical errors. We calculated a mean score on all measures for each sample to enable comparison across samples.

Types of signs

Participants used lexical signs, classifiers, and finger-spelled words in their signing samples, predominantly using lexical signs. The two prompts elicited different proportions of classifiers and fingerspelling. The video retelling elicited more fingerspelling and classifiers than the family narrative: The video retelling elicited an average of 9.55% finger-spelled words, while the family narrative elicited 5.99% finger-spelled words (see ).

Table 2. Summary of sign type in expressive language sample

Table 3. Summary of errors in expressive language sample.

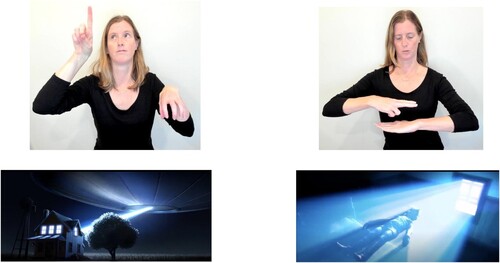

With regard to classifiers, the video retelling elicited classifiers for an average of 19.2% of the signs, compared to 2.44% of the signs in the family narrative. Although we did not attempt to analyse the classifiers for morphological complexity, we did note parents’ use of classifiers depicting multiple entities in specific spatial relationships to one another (see examples in ), suggesting that at least some parents had a solid grasp of the use of complex classifiers in ASL.

Figure 7. Classifier constructions.

Note: These images are reproduced by the authors to maintain participant anonymity. Left panel shows a classifier construction depicting the house and the location of the spaceship relative to the house. Right panel shows a classifier construction depicting the bed and the boy hovering above the bed. Still frames from Klokline Cinema (Citation2019).

Lexical diversity

We calculated the number of unique lexical signs that participants used in each video by dividing the number of unique glosses by the number of total signs produced. The mean percent of unique lexical signs was similar across samples; 63.34% (SD = 12.44%) for the video retelling and 62.68% (SD = 8.87%) for the family narrative.

Errors

We analysed phonological and lexical errors in participants’ sign productions. Both prompts elicited a similar number of errors, and phonological errors were more frequent overall than lexical errors. In the video retelling, participants made an average of 1.50 lexical errors (SD = 2.19, range = 0.9), and 4.6 phonological errors (SD = 2.72, range = 0.11). In the family narrative, participants made an average of 1.25 lexical errors (SD = 1.71, range = 0.7) and 6.4 phonological errors (SD = 4.9, range = 0.19) (see ).

Discussion

In this study, we sought to directly evaluate the receptive and expressive ASL skills of a group of hearing parents who identified as ASL learners. We aimed to provide a high-level snapshot of hearing parent ASL skills among a larger sample, and an in-depth analysis of expressive ASL skills in a subset of participants. The results of our assessment revealed that the hearing parents in this sample have ASL skills which fall in the beginning and intermediate range, with vocabulary being the strongest domain of ASL production. Their expressive and receptive skills were highly correlated. A surprising finding was that parents' skills did not improve with the duration of signing experience, and only expressive skills correlated with the child's age. In general, the parents' scores on these measures parallel other populations of hearing L2 ASL students reported in the literature. A closer examination of the features of ASL production in hearing parents indicated that parents used diverse vocabulary, used classifier constructions in appropriate contexts, and incorporated fingerspelling in their stories. They produced errors that were mostly phonological in nature. Our analysis suggests that hearing parents are acquiring many features of ASL and implementing them albeit with errors typical for L2 learners.

ASL receptive skills among hearing parents

Parents' receptive ASL skills were assessed using the ASL-CT. Parents in our sample scored similarly to the hearing ASL students in the norming sample for the ASL-CT (Hauser et al. Citation2016), but slightly higher than college ASL students in a recent study (Hall and Reidies Citation2021). However, our sample is a self-selected one that may be higher scoring than the average parent learner: recall that parents were recruited as part of two larger studies where parents were asked to submit both the ASL-CT and the expressive sample. Some parents opted to complete the ASL-CT and did not submit a video. Berger et al. (2024) found that parents who submitted a video had higher average ASL comprehension scores than those that did not. The current sample included only parents who submitted a video. This suggests that parents who submitted videos were potentially more advanced and therefore more comfortable with their signing.

The hearing parents in our sample appear to be developing their receptive ASL skills similarly to other adult L2 ASL learners. This is particularly interesting considering the differences in the two populations. ASL students in college settings have a more uniform learning setting, while parents learn from a variety of sources including classes through their child's school, mentors or tutors, and university classes (Lieberman, Mitchiner, and Pontecorvo Citation2024). College students have varied motivations for learning, and are often motivated by personal interest or to pursue a career (Beal Citation2020). On the other hand, hearing parents have a time-sensitive and important motivation to learn to facilitate communication with their child (Chen Pichler Citation2021; Oyserman and de Geus Citation2021; Snoddon Citation2014). It is possible that there are item-level differences in the performance of hearing parents and that of other L2 learners; an assessment more sensitive than the ASL-CT would be needed to explore this possibility. Nevertheless, the fact that parents with a range of types of exposure are able to comprehend ASL at an intermediate level suggests that the motivation and urgency that hearing parents bring to the task serve as a positive influence on their learning.

ASL expressive skills among hearing parents

The parents in our sample possessed beginner to high intermediate ASL expressive skills. These results are similar to those reported by Oyserman and de Geus (Citation2021) who studied hearing parents who participated in parent sign language classes with a CEFR-aligned curriculum. Those parents attained low A2 to low B1 skills, with the majority being high A2. The comparison between the scores in the two samples should be interpreted with caution, because the parents were evaluated on different tasks (∼2 min video sample in the current study vs. a 40 min in-class assessment by Oyserman & de Geus), by different evaluators, and the parents in Oyserman & de Geus were evaluated on their expressive, receptive, and interaction skills not solely their expressive skills. However, a broad comparison shows that parents in both samples were in the beginning and intermediate range. Oyserman & de Geus suggest that it is important for parents of deaf children to reach the level of an autonomous, independent (B1/B2) sign language user. Many parents in our sample reached a B1 or B2 level which may allow parents to be independent communicators with their children.

We further evaluated parents’ expressive skills in specific areas including vocabulary, grammar, fluency, and overall production. Although there was variation both within and across individuals, vocabulary scores were slightly higher than scores in the other domains. This pattern aligns with reports from hearing parents interviewed by Chen Pichler (Citation2021) who found ASL vocabulary easier to learn than grammar. It is also possible that this discrepancy reflects a pedagogical focus on vocabulary in the types of sign language classes in which hearing parents participate.

Parent ASL skills and child age

Parents demonstrated a range of ASL skills on the receptive and expressive measures from beginning to intermediate. Expressive and receptive measures were highly correlated with expressive skills sometimes lagging behind receptive, as is typical for L2 learners. Contrary to our predictions, we found that the length of time that parents had been learning ASL did not predict their scores on receptive or expressive measures. The child's age predicted parent expressive but not receptive scores. We consider several possible explanations for this surprising set of findings. It could be that parents’ language skills plateau after an initial period of intensive learning, such that parents of older children maintain the proficiency they obtained in their child's first few years of life. Parents in Lieberman, Mitchiner, and Pontecorvo (Citation2024) reported difficulty finding continued support for learning sign language after their child aged out of early intervention services and parents in Oyserman and de Geus (Citation2021) also reported difficulty finding more advanced sign language classes. It is also possible that our sample was too small to detect true age-related differences in ASL receptive skills. Or perhaps, given that our task only involved a single assessment representing a snapshot in time, we could not capture growth over time within individual parents.

Linguistic analysis of ASL production

We analysed the linguistic features of hearing parents’ ASL use in the domains of vocabulary, grammar, classifier use, fingerspelling, and errors. This analysis revealed that parents used a moderately diverse vocabulary, and incorporated grammatical features of ASL, including classifier constructions and fingerspelling. The samples had relatively few errors, and tended to be phonological production errors, which are common for L2 learners of spoken languages (Birdsong Citation2006). We found that the context (i.e. a video retelling vs. a family narrative) influenced parents’ use of classifiers and other aspects of ASL.

Vocabulary and errors

We analysed both the diversity and accuracy of parent ASL signs. Across the two expressive language samples, parents had moderately diverse vocabularies. Some repetition occurred in both prompts, but this was likely due to the limited context (e.g. parents describing the Pixar video often referred to the alien and the sleeping man multiple times to convey the narrative). While we did not analyse which words parents used, we note that although parents were learning ASL to communicate with their children, they were able to convey concepts beyond early routines. Further, scores on the vocabulary rubrics were higher than those on other rubrics, suggesting that vocabulary may be somewhat easier to acquire than grammatical aspects of ASL. We propose that parents are resourceful in seeking out ASL vocabulary and in conveying their ideas despite the fact that most acquire ASL outside of formal classroom settings. The pattern of phonological errors suggests that parents were more likely to choose a correct sign but articulate it incorrectly than to choose an incorrect or inappropriate sign.

Fingerspelling

Fingerspelling is a feature of signed languages in which the manual alphabet is used to spell out full words in the dominant spoken/written language. It is an aspect of ASL that does not have a direct parallel in spoken English. Fingerspelling is often used for names of people and places, as well as for lexical borrowing from English. Because fingerspelling occurs rapidly, it is often difficult for L2 ASL students to become adept at perceiving (Geer and Keane Citation2018). Another use for fingerspelling for L2 users is to spell a word for which they do not yet know the sign, relying on their interlocutor's knowledge of written English. Parents in our sample fingerspelled more in the video retelling than in the family narrative, which likely corresponds to the presence of the concepts ‘alien’ and ‘UFO’ which were often produced with fingerspelling in ASL. Participants used fingerspelling appropriately for uncommon words and acronyms (e.g. UFO), and did not rely heavily on fingerspelling to compensate for unknown vocabulary.

Classifier constructions

Classifier constructions have been proposed to be a difficult element of ASL grammar for L2 learners to master (Boers-Visker Citation2024; Boers-Visker and Van Den Bogaerde Citation2019; Ferrara and Nilsson Citation2017), and a survey of hearing parents learning ASL found that parents reported classifiers among the most difficult aspects of ASL to learn (Chen Pichler Citation2021). We were particularly interested in classifier usage, since this is a grammatical feature that is not very salient in the participants’ L1 (most commonly English), and because the use of classifier constructions requires the use of three-dimensional space which is unique to sign languages.

The video retelling was designed to elicit description skills best conveyed in ASL through the use of classifier constructions. Participants used classifiers for 19.2% of their signs in this prompt. We found that parents were capable of using classifier constructions, and constructions that convey several pieces of information at once. In contrast, parents used very few classifiers in the family narrative (on average 2.4%). These results are similar to a large corpus study of ASL (Morford and MacFarlane Citation2003) which found significant variation in the frequency of classifier use across genres. Across their corpus, classifiers represented an average of 4.2% of the signs, ranging from 17.7% of signs during narrative stories, to only 0.9% of the time in formal register. We propose that this reflects an appropriate adaptation of sign usage to the context. Even as L2 learners, the parents in our study modulated their classifier use depending on the necessity of classifiers in each communicative context.

Summary

Parents’ L2 ASL shares features of L2 ASL and general L2 acquisition that have been reported in the literature. Specifically, we see that they are learning advanced features of ASL such as classifier constructions, and find this encouraging evidence that parents are capable of learning ASL as an L2 and need not be steered to a more simplified version of sign language learning. Parents demonstrated an ability to adapt their language usage to different situations, producing more classifiers in a prompt requiring visual description. Furthermore, their patterns of errors, which are dominated by phonological errors, and their relative strength in using a diverse vocabulary parallel typical adult L2 acquisition.

Parents as L2 ASL signers

The parents in our sample achieved beginner to intermediate skills in ASL. What does this mean for parents’ ability to communicate with their deaf children? As adult L2 learners, sign language proficiency akin to people who learned a sign language from birth is not the appropriate goalpost for hearing parents who are learning to sign. The concept of plurilingualism helps clarify why that need not be the goal. Plurilingualism rejects the fluency standards associated with the ‘ideal’ monolingual speaker. From a plurilingual framework, languages are productive, and people use multiple languages in their lives to meet their communicative needs. The communicative needs of hearing parents are unique and important (Chen Pichler Citation2021), and parents in our sample demonstrate receptive and expressive use of ASL at varying levels, indicating that they may be able to meet their family's communicative needs to different degrees. Oyserman and de Geus (Citation2021) posit that in the CEFR scoring system, parents who can sign at a B2 level will be autonomous communicators with their deaf children, and some parents in our sample demonstrated ASL skills at that level. Previous research has found the plurilingualism framework to be empowering to parents as they learn to navigate important communicative contexts in their own life using a sign language, such as the ability to resolve conflict between siblings (Oyserman and de Geus Citation2021; Snoddon Citation2015). Furthermore, recent work suggests that hearing parents with a range of ASL skills can support age-expected ASL development in their young deaf children (Berger et al. Citation2024; Caselli, Pyers, and Lieberman Citation2021).

Limitations and future directions

This study adds to our understanding of parent ASL knowledge; however, there are some characteristics in the composition of our sample and in the nature of the elicited language samples that may limit our ability to generalise to a larger and more diverse population. Our sample is not reflective of the demographics of parent ASL learners across the US, in that it lacks racial and ethnic diversity and the education level is higher than the national average. As such, our sample may not be reflective of the ASL learning experience of parents across the US, as these factors can affect the educational resources parents have access to and the time available to support their language learning. Our sample may have also been skewed towards individuals with enough ASL proficiency that they were willing to submit a video of themselves signing, and willing to comple a receptive ASL assessment task.

The elicited language samples also have limitations as a measure of overall ASL skills. They are a snapshot in time, so we cannot investigate parents’ learning curve, or ultimate attainment of ASL skills. Longitudinal data would better help us understand whether there is a relationship between the child's age or number of years learning ASL with parent skills. Additionally, the CEFR has three communicative competency strands: production, reception, and interaction. Because we did not analyse the interaction skills of our participants, we are not able to estimate skills the parents have developed for interacting with both adults and children in ASL. It is possible that participants would perform better on the expressive task than during live conversation as participants might have practised their responses. Conversely, it is possible that their communicative competence with their own children may be higher than what is reflected in our methods of evaluation given familiarity and shared context.

While we documented a range of ASL skills among parents learning ASL, more research is needed to pinpoint the factors that enable some parents to achieve higher ASL skills. Parents in our sample learned from a range of sources, including ASL classes through early intervention and at the college level, individual instruction with tutors and deaf mentors, and self-teaching through online materials (Lieberman, Mitchiner, and Pontecorvo Citation2024). The findings of our study could pave the way for action research situated within classes designed for parents who are learning ASL. For example, an assessment provided as part of an ongoing beginner-level course might better capture the full range of emerging ASL skills among hearing parents. A classroom setting would also be an ideal place to study parent sign skills in the context of an interaction. Additionally, implementing the CEFR rubrics with parents in a class setting could lead to future classes that are designed specifically around the skills parents need to become independent communicators with their children (see Oyserman and de Geus Citation2021; Snoddon Citation2015; Zarchy and Geer Citation2023). Finally, some of the questions generated in this study could be addressed by surveying parents further about where and how they are learning ASL.

Conclusion

This paper is a novel contribution to the literature on L2M2 ASL learners by focusing on a unique group of learners, hearing parents with deaf children. Understanding how best to support parent ASL learning is critical for designing instructional methods and classes that would most benefit hearing parents. Additionally, it is critical to tie parent ASL skills, as we have documented here, with ASL outcomes among their deaf children (Berger et al. Citation2024).

We found that parents who were committed to learning ASL were able to achieve beginning to intermediate ASL skills, using a range of linguistic features in their production including a diverse vocabulary, fingerspelling, and classifier constructions. These findings counter dominant narratives that learning ASL is too difficult for hearing parents with deaf children (e.g. Knoors and Marschark Citation2012; Snoddon Citation2020). This study is one of few studies to evaluate hearing parents’ signing (Berger et al. Citation2024; Oyserman and de Geus Citation2021). The framework for evaluating linguistic competence is important for considering L2 outcomes. Instead of expecting ASL learners to achieve fluency measured against L1 language users, a pluralistic competency model, as outlined in the CEFR, allows learners and evaluators to view language learners as functional language users who develop competencies in multiple languages that meet their communicative needs. In this framework, parents in our sample, particularly those who reached the intermediate level in the CEFR (B1, B2) demonstrated independent expressive competencies that they can use to communicate in ASL with their deaf child, and deaf people in their child's life.

Our findings can support practitioners and educators in counselling families with deaf children towards learning ASL. Currently, many parents are not directed towards ASL based on the assumption that parents who are new signers will not be able to achieve a level of proficiency to support the documented benefits of ASL for deaf children. Encouraging families with deaf children to embrace multilingualism by learning a sign language provides a visually accessible language for deaf children, which supports deaf children's linguistic development (Berger et al. Citation2024), and can increase family communication (Oyserman and de Geus Citation2021). We hope that the current study spurs further inquiries into the ways in which hearing parents can support ASL development among their deaf children.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to Kerianna Chamberlain, Hannah Goldblatt, Adele Daniels, Ruth Ferster, and Erin Spurgeon for their help with data collection and coding. We express gratitude to the parents who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available at https://osf.io/qjmek/.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The term ‘sighted’ refers to children with normal or corrected to normal vision. For Deafblind or low vision children, ASL may not be a fully accessible language. Pro-Tactile ASL is a tactile language that would be perceptually accessible for children who are Deafblind or low vision.

2 We use the terms ‘deaf’ and ‘deaf and hard of hearing’ as inclusive terms for children with a range of hearing levels who may describe themselves as deaf, hard of hearing, deafblind, and deafdisabled.

3 Classifier constructions, sometimes called ‘depicting signs,’ are handshapes that can be manipulated flexibly to depict actions, locations, and descriptions.

4 The CEFR also informs the development of popular language learning applications (Blanco Citation2020).

References

- Beal, J. 2020. “University American Sign Language (ASL) Second Language Learners: Receptive and Expressive ASL Performance.” Journal of Interpretation 28 (1): 1–27.

- Berger, L., J. Pyers, A. Lieberman, and N. Caselli. 2024. “Parent American Sign Language Skills Correlate With Child–But Not Toddler–ASL Vocabulary Size.” Language Acquisition 31 (2): 85–89.

- Birdsong, D. 2006. “Age and Second Language Acquisition and Processing: A Selective Overview.” Language Learning 56 (s1): 9–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2006.00353.x.

- Blanco, C. 2020, February 27. “Goldilocks and the CEFR levels: Which proficiency level is just right?” Duolingo Blog. https://blog.duolingo.com/goldilocks-and-the-cefr-levels-which-proficiency-level-is-just-right/

- Boers-Visker, E. 2024. “On the Acquisition of Complex Classifier Constructions by L2 Learners of a Sign Language.” Language Teaching Research 28 (2): 749–785. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168821990968.

- Boers-Visker, E., and R. Pfau. 2020. “Space Oddities: The Acquisition of Agreement Verbs by L2 Learners of Sign Language of the Netherlands.” The Modern Language Journal 104 (4): 757–780. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12676.

- Boers-Visker, E., and B. Van Den Bogaerde. 2019. “Learning to Use Space in the L2 Acquisition of a Signed Language: Two Case Studies.” Sign Language Studies 19 (3): 410–452. https://doi.org/10.1353/sls.2019.0003.

- Calderon, R. 2000. “Parental Involvement in Deaf Children's Education Programs as a Predictor of Child's Language, Early Reading, and Social-Emotional Development.” Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 5 (2): 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/5.2.140.

- Caselli, N., J. Pyers, and A. M. Lieberman. 2021. “Deaf Children of Hearing Parents Have Age-Level Vocabulary Growth When Exposed to American Sign Language by 6 Months of Age.” The Journal of Pediatrics 232: 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.01.029.

- Chen Pichler, D. 2021. “Constructing a Profile of Successful L2 Signer Hearing Parents of Deaf Children.” In Minpaku Sign Language Studies 2, edited by R. Kikusawa, and F. Sano, 115–131. Osaka: Senri Ethnological Studies.

- Chen Pichler, D., and E. Koulidobrova. 2016. “Acquisition of Sign Language as a Second Language.” In The Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies in Language, edited by M. Marschark, and P. E. Spencer, 218–230. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Crasborn, O., and H. Sloetjes. 2008. “Enhanced ELAN Functionality for Sign Language Corpora.” In 6th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2008). 3rd Workshop on the Representation and Processing of Sign Languages: Construction and Exploitation of Sign Language Corpora, pp. 39-43.

- Ferrara, L., and A. L. Nilsson. 2017. “Describing Spatial Layouts as an L2M2 Signed Language Learner.” Sign Language & Linguistics 20 (1): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1075/sll.20.1.01fer.

- Geer, L. C., and J. Keane. 2018. “Improving ASL Fingerspelling Comprehension in L2 Learners With Explicit Phonetic Instruction.” Language Teaching Research 22 (4): 439–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168816686988.

- Hall, M. L., and J. A. Reidies. 2021. “Measuring Receptive ASL Skills in Novice Signers and Nonsigners.” The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 26 (4): 501–510. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enab024

- Hartshorne, J. K., J. B. Tenenbaum, and S. Pinker. 2018. “A Critical Period for Second Language Acquisition: Evidence From 2/3 Million English Speakers.” Cognition 177: 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.04.007.

- Hauser, P. C., R. Paludneviciene, W. Riddle, K. B. Kurz, K. Emmorey, and J. Contreras. 2016. “American Sign Language Comprehension Test: A Tool for Sign Language Researchers.” Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 21 (1): 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/env051.

- Hochgesang, J. A., O. Crasborn, and D. Lillo-Martin. 2018. “Building the ASL Signbank: Lemmatization Principles for ASL.” Poster presented at the 8th Workshop on the Representation and Processing of Sign Languages. 11th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, LREC 2018, Miyazaki, Japan. May 12, 2018.

- Klokline Cinema. 2019, Feb 19. “2006 Lifted Official Trailer 1 HD Pixar Animation Studios [Video].” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = 3937g8vL4fg.

- Knoors, H., and M. Marschark. 2012. “Language Planning for the 21st Century: Revisiting Bilingual Language Policy for Deaf Children.” Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 17 (3): 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/ens018.

- Leeson, L., B. van den Bogaerde, C. Rathmann, and T. Haug. 2016. Sign Languages and the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. Common Reference Level Descriptors. Graz: European Centre for Modern Languages.

- Lieberman, A., J. Mitchiner, and E. Pontecorvo. 2024. “Hearing Parents Learning American Sign Language with Their Deaf Children: A Mixed-Methods Survey.” Applied Linguistics Review 15 (1): 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2021-0120.

- Lillo-Martin, D. C., E. Gale, and D. Chen Pichler. 2023. “Family ASL: An Early Start to Equitable Education for Deaf Children.” Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 43 (2): 156–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/02711214211031307.

- Looney, D., and N. Lusin. 2018. “Enrollments in Language Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Summer 2016 and fall 2016: Preliminary Report.” Retrieved from https://www.mla.org/content/ download/83540/2197676/2016-Enrollments-Short-Report.pdf.

- Morford, J. P., and J. MacFarlane. 2003. “Frequency Characteristics of American Sign Language.” Sign Language Studies 3 (2): 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1353/sls.2003.0003.

- Napier, J., Leigh, G., & Nann, S. (2007). “Teaching Sign Language to Hearing Parents of Deaf Children: An Action Research Process.” Deafness & Education International 9(2). 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1179/146431507790560020

- Oyserman, J., and M. de Geus. 2021. “Implementing a New Design in Parent Sign Language Teaching: The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR).” In Critical Perspectives on Plurilingualism in Deaf Education, edited by K. Snoddon, and J. C. Weber, 173–194. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Ringbom, H. 2007. Cross-Linguistic Similarity in Foreign Language Learning (Vol. 21). Tonawanda, NY: Multilingual Matters.

- Sanz, C. 2005. Mind and Context in Adult Second Language Acquisition: Methods, Theory, and Practice. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Schönström, K., and I. Holmström. 2022. “L2M1 and L2M2 Acquisition of Sign Lexicon: The Impact of Multimodality on the Sign Second Language Acquisition.” Frontiers in Psychology 13: 896254. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.896254.

- Snoddon, K. 2014. “Hearing Parents as Plurilingual Learners of ASL.” In Teaching and Learning Signed Languages: International Perspectives and Practices, edited by D. McKee, R. S. Rosen, and R. McKee, 175–196. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Snoddon, K. 2015. “Using the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages to Teach Sign Language to Parents of Deaf Children.” The Canadian Modern Language Review 71 (3): 270–287. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.2602.

- Snoddon, K. 2020. “Teaching Sign Language to Parents of Deaf Children in the Name of the CEFR: Exploring Tensions Between Plurilingual Ideologies and ASL Pedagogical Ideologies.” In Sign Language Ideologies in Practice, edited by A. Kusters, M. Green, E. Moriarty, and K. Snoddon, 145–164. Boston/Berlin: Walter de Gruyter Inc.

- Zarchy, R. M., and L. C. Geer. 2023. A Family-Centered Signed Language Curriculum to Support Deaf Children’s Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.