ABSTRACT

Drawing on the Language Mindset Meaning System (LMMS) framework, the study investigated how language mindsets (growth vs. fixed) influence the adoption of the four achievement goals, and how they subsequently shape second/foreign language (L2) learners’ emotions (i.e. enjoyment and anxiety) in the process of learning English as a foreign language (EFL) in China. A total of 413 Chinese university students participated in a questionnaire survey. Path analyses showed that a growth language mindset had a strong positive impact on enjoyment and a moderate negative impact on anxiety. Conversely, a fixed language mindset had a moderate positive effect on anxiety. Results also showed that mastery-approach, mastery-avoidance and performance-avoidance goals mediated the relationship between language mindsets and the two L2 emotions. These findings offer profound insights into the intricate web of relationships among language mindsets, achievement goals and L2 emotions, instantiating the LMMS framework in the specific EFL context. These insights hold practical implications for educational practitioners seeking to enhance learners’ emotional well-being.

Introduction

Aligned with the positive shift in psychology and general education (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi Citation2000), numerous empirical studies in second language acquisition (SLA) have taken a holistic approach to examining the emotions experienced during second/foreign language (L2) learning (Wang, Derakhshan, and Zhang Citation2021). Among these, enjoyment and anxiety are the most commonly reported emotions in L2 classes (Dewaele and MacIntyre Citation2014). At the same time, extensive studies underscored their significant influence on motivational and cognitive processes, well-being, and achievement in L2 learning (Derakhshan and Yin Citation2024; Dewaele and MacIntyre Citation2016; Li, Dewaele, and Jiang Citation2020; Teimouri, Goetze, and Plonsky Citation2019). However, consensus concerning the mechanism underlying these emotions remains elusive (Dewaele, Botes, and Greiff Citation2023).

According to the Language Mindset Meaning System (LMMS) (Lou and Noels Citation2020), language mindsets are fundamental to meaning-making in learners’ L2 experience. Language mindsets reflect learners’ beliefs about whether language learning ability is malleable or fixed (growth vs. fixed) (Lou and Noels Citation2016, Citation2017). These beliefs are systematically linked to motivational beliefs and learning behaviours, such as effort beliefs, achievement goals, and emotional tendencies (Derakhshan and Fathi Citation2024; Lou and Noels Citation2020). Achievement goals, defined as cognitive representations of competence-focused aims that guide behaviour in a particular direction (Elliot and McGregor Citation2001), are integrated into this comprehensive framework as an important mediating motivational factor. Lou and Noels (Citation2016; Citation2017) tested a ‘mindsets-goals-responses’ model and verified that language mindsets influence the adoption of the three achievement goals (mastery-approach, performance-approach, and performance-avoidance), which, in turn, affects their emotions such as anxiety in challenging situations. Notably, the mastery-avoidance goal, representing the striving to avoid demonstrating personal incompetence (Elliot and McGregor Citation2001), is overlooked in the LMMS and empirical studies in language learning (e.g. Lou and Noels Citation2016, Citation2017; Yao et al. Citation2021). However, it is a distinctive achievement goal commonly adopted by language learners and should be examined for a more comprehensive understanding of achievement goals (Li and Li Citation2024).

Aligned with LMMS, anxiety is commonly observed as a response associated with fixed language mindset and performance goals in challenging situations (Lou and Noels Citation2016, Citation2017). Enjoyment typically emerges in challenging language learning scenarios (Csikszentmihalhi Citation1997; Dewaele and MacIntyre Citation2014). Previous L2 studies have suggested that enjoyment may be predicted by a growth language mindset (Li et al. Citation2023) or a mastery-approach goal (Li and Li Citation2024). However, how language mindsets interact with achievement goals to affect L2 enjoyment, as posited by LMMS, remains unexplored, justifying this study. This exploration is particularly valuable for understanding Chinese university EFL students, who regularly experience academic emotions in their daily tasks. Furthermore, the role of mastery-avoidance goal has been largely ignored in LMMS and L2 studies (e.g. Lou and Noels Citation2016, Citation2017; Yao et al. Citation2021). Thus, this study aims to address these gaps from a new angle by taking into account all these variables, trying to elucidate the interplay between language mindsets, four types of achievement goals, and their influence on L2 enjoyment and anxiety. These findings could expand LMMS by incorporating the mastery-avoidance goal and validating its application among Chinese university students. Moreover, the study seeks to illuminate the complex mechanisms underlying L2 enjoyment and anxiety in the Chinese EFL context.

Literature review

Language mindset meaning system (LMMS)

According to the LMMS framework (Lou and Noels Citation2019, 543), language mindsets (growth vs. fixed) are core beliefs that significantly influence learners’ motivation and behaviorus in L2 learning. Students with a language growth mindset see language learning ability as a malleable capacity that can be developed, while a language-fixed mindset entails that one’s language learning ability is unalterable (Lou and Noels Citation2019). Achievement goals, including mastery-approach goals (focusing on mastery and learning process), performance-approach goals (focusing on demonstrating competence or outperforming others) and performance-avoidance goals (focusing on avoiding the display of incompetence) (Elliot and Church Citation1997), are integrated into LMMS as important mediating motivational factors. According to the LMMS framework, learners with a growth language mindset, on average, tend to endorse mastery-approach goals. Subsequently, this goal would lead to better academic achievement. Conversely, learners with a fixed language mindset are likely to adopt performance-approach or performance-avoidance goals (Elliot and Harackiewicz Citation1996), contingent on learners’ perception of their language competence. These learners would engage in self-defensive behaviors and exhibit worse performance over time (Dweck and Molden Citation2017; Lou and Noels Citation2019).

Studies in SLA generally support the view that a growth language mindset predicts a mastery-approach goal (e.g. Lou and Noels Citation2017; Papi et al. Citation2019). However, the relationship between language mindsets and performance goals remains elusive. For example, Lou and Noels (Citation2017) tested the ‘mindsets-goals-responses’ path model within the context of tertiary education in North America. They found that a fixed language mindset led to performance-approach goals and heightened anxiety (Lou and Noels Citation2017, 218), but performance-avoidance goals were not associated with either growth or fixed mindsets significantly. Yao et al. (Citation2021) also found no mediation by performance goals between a fixed language mindset and helpless responses. In contrast, Papi et al. (Citation2019) found that the performance-approach goal was positively predicted by both fixed and growth language mindsets. These inconsistencies suggest that the link between language mindsets and performance goals is complex and warrants further investigation.

It is important to note that researchers in educational psychology argued for a more nuanced view of mindsets and achievement goals. For example, a meta-analysis revealed that a growth mindset is not only positively associated with mastery goals but also negatively predicted performance goals (Burnette et al. Citation2013). Additionally, Yu and McLellan (Citation2020) proposed that learners with the same mindset may endorse different achievement goal patterns. For example, learners with a growth mindset might pursue strong performance goals alongside mastery goals (Dweck Citation1999). Conversely, students with a fixed mindset may fail to find meaning in engaging in either mastery or performance-related activities, if they perceive their ability as low, resulting in a lower level of mastery and performance goals (Yu and McLellan Citation2020). Therefore, in the present study, beyond the distinctive motivation patterns predicted by growth and fixed language mindsets in accordance with the LMMS framework, we also hypothesise that a growth language mindset would positively predict the performance-approach goal, whereas a fixed language mindset would negatively predict the mastery-approach goal.

Additionally, the mastery-avoidance goal has yet to be integrated into the LMMS or examined in SLA studies (e.g. Lou and Noels Citation2017; Yao et al. Citation2021). The mastery-avoidance goal differs from the mastery-approach goal by focusing on avoiding incompetence rather than achieving competence. It also differs from performance-avoidance goals by using a relatively stable referent intrinsic to the task or personal attainment trajectory rather than a normative referent tied to others (Elliot and McGregor Citation2001). An inclusion of the mastery-avoidance goal is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of achievement goals (Li and Li Citation2024; Baranik et al. Citation2010). Thus, this study intends to further investigate the link between language mindsets and four types of achievement goals, as well as their joint impact on learners’ emotions in language learning.

L2 enjoyment and anxiety

Language learning is inherently challenging, especially for learners without an immersive environment (Peng Citation2014). Among the spectrum of emotions that arise in the process of language learning, enjoyment and anxiety are the most commonly experienced and extensively studied in SLA (Zhang Citation2001; MacIntyre Citation2017). L2 anxiety is defined as ‘the worry and negative emotional reaction aroused when learning or using a second language’ (MacIntyre Citation1999, 27). As a counterpart to L2 anxiety, Dewaele and MacIntyre (Citation2014) introduced L2 enjoyment to highlight the role of positive emotions in language development (MacIntyre and Gregersen Citation2012). L2 enjoyment refers to a positive emotional state experienced by L2 learners when their psychological needs are fulfilled, encompassing feelings of fun, interest and happiness (Li and Li Citation2024). It has gained recognition as a central positive emotion in SLA research (e.g. Li, Jiang, and Dewaele Citation2018).

Numerous studies have reported that L2 enjoyment is positively linked to language achievement, engagement, L2 speech performance, willingness to communicate and motivation (Dewaele and Li Citation2022; Li, Dewaele, and Jiang Citation2020). Conversely, L2 anxiety has consistently shown negative effects on academic, cognitive and social aspects of language learning (Dewaele and MacIntyre Citation2016; MacIntyre Citation2017). Meta-analyses substantiate a moderate negative association between L2 anxiety and language performance (Botes, Dewaele, and Greiff Citation2020; Teimouri, Goetze, and Plonsky Citation2019). Given the prevalence and significant role of the two emotions on language learners’ motivation, engagement and achievement, the present study focused on L2 anxiety and L2 enjoyment as outcome variables.

Language mindset and L2 enjoyment and anxiety

Recent forays into the interplay between language mindset and L2 emotions within SLA have illuminated intriguing connections, with most studies focusing on anxiety. Studies indicated that a fixed language mindset was positively linked to anxiety in L2 speaking, whereas a growth mindset predicted increased self-confidence (Lou and Noels Citation2020; Ozdemir and Papi Citation2021). Similarly, in online FL classes among 640 Chinese young FL learners, Dong (Citation2022) discovered that a fixed language mindset significantly predicted anxiety, whereas a growth language mindset did not.

Some studies investigated the relationship of language mindset with both anxiety and enjoyment. For example, Li et al. (Citation2023) employed latent profile analysis to categorise Chinese EFL learners into four profiles: growth, high-mixed, low-mixed, and fixed. The growth profile experienced the highest enjoyment and the lowest anxiety, while the fixed profile exhibited the lowest enjoyment and the highest anxiety. Similarly, Wang, Peng, and Patterson (Citation2021) found that a growth language mindset predicted higher enjoyment but had no significant association with anxiety. Additionally, Khajavy, Pourtahmasb, and Li (Citation2022) revealed that a fixed L2 reading mindset correlated with higher L2 reading anxiety and lower L2 reading enjoyment, whereas a growth L2 reading mindset positively predicted L2 reading enjoyment, but not L2 reading anxiety.

These intricate relationships suggest the presence of potential mediating or moderating factors in the mindset-emotion connection (Lou and Noels Citation2017). For instance, Dong (Citation2022) identified emotion regulation as a mediator for the negative effect of growth mindset on emotions like boredom and anger. Similarly, Zarrinabadi et al. (Citation2022) highlighted the mediating effect of adaptation between mindset and emotions. Given the regulatory effect of achievement goals on language learners’ emotional responses as proposed in LMMS framework, this study examines the possible mediating role of the four types of achievement goals between language mindset and L2 enjoyment and anxiety.

Achievement goals and L2 enjoyment and anxiety

Achievement goals are central to achievement motivation and significantly influence achievement emotions (Pekrun, Elliot, and Maier Citation2006, Citation2009). However, their application in SLA is limited (Li et al. Citation2022). Recent SLA studies have shown positive effects of the mastery-approach goal and negative effects of the performance-avoidance goal on various aspects, including language learning strategies, self-regulation, self-efficacy, academic achievement, and reduction of anxiety (Li and Xu Citation2014; Turner, Li, and Wei Citation2021). However, mixed findings exist for the relationship between the performance-approach goal and L2 emotions, and the mastery-avoidance goal remained underexplored (Feng, Wang, and King Citation2023). For example, in the Chinese tertiary-level EFL learning context, Li and Li (Citation2024) found no significant association between the performance-approach goal and enjoyment or anxiety and that the mastery-avoidance goal was positively associated with anxiety but not enjoyment. However, Feng, Wang, and King (Citation2023) found that both mastery and performance-approach goals positively correlated with enjoyment and negatively to anxiety, while the performance-avoidance goal correlated positively with anxiety and negatively with enjoyment. Notably, the mastery-avoidance goal was not examined.

In general education, more studies examined the relationship between achievement goals and emotions (see Huang Citation2011 and Linnenbrink-Garcia and Barger Citation2014 for a review). Generally, studies revealed the mastery-approach goal promoted enjoyment and reduced anxiety (e.g. Hall et al. Citation2016; Pekrun, Elliot, and Maier Citation2006, Citation2009). Conversely, the performance-avoidance goal was positively correlated with anxiety and negatively (or not significantly) linked to enjoyment (Hall et al. Citation2016; Huang Citation2011; Pekrun, Elliot, and Maier Citation2006, Citation2009). However, previous studies have exhibited divergent results concerning the relationship between the performance-approach goal and anxiety (positive, insignificant and negative association; e.g. Elliot and McGregor Citation2001; Harackiewicz et al. Citation2002) and enjoyment (positive or insignificant, e.g. Daniels et al. Citation2009; Putwain, Sander, and Larkin Citation2013). Similar to the L2 context, less attention has been paid to the mastery-avoidance goal. A few research studies showed that the mastery-avoidance goal was positively correlated with anxiety (e.g. Elliot and McGregor Citation2001) and positive emotions such as interest (e.g. Deemer, Martens, and Podchaski Citation2007). The mastery-avoidance goal was assumed to have a negative impact on enjoyment (Elliot and Pekrun Citation2007), but empirical evidence is still lacking. In an effort to expand on existing research in both general education and SLA, the present study aims to explore how language mindsets and achievement goals contribute to the experiences of L2 enjoyment and anxiety in language learning.

Present study

As highlighted in previous sections, the LMMS framework (Lou and Noels Citation2019), along with previous empirical studies, have underscored the intricate connections among (a) language mindsets and achievement goals (e.g. Lou and Noels Citation2017; Papi et al. Citation2019); (b) language mindset and L2 emotions (e.g. Khajavy, Pourtahmasb, and Li Citation2022); and (c) achievement goals and L2 emotions (e.g. Feng, Wang, and King Citation2023). However, certain gaps persist in the framework and empirical studies. Primarily, the LMMS framework did not include a mastery-avoidance goal, a distinctive goal orientation that warrants integration into the achievement goal framework (Baranik et al. Citation2010; Li and Li Citation2024). Additionally, scant research has examined how language mindset in combination with achievement goals would affect L2 enjoyment and anxiety; Furthermore, inconsistencies abound in findings pertaining to both the relationship between language mindsets and achievement goals, especially performance goals (Burnette et al. Citation2013; Yao et al. Citation2021), as well as the relationship between the performance-approach goal and achievement emotions (Li et al. Citation2022; Feng, Wang, and King Citation2023).

Contextual features unique to the present study further enhance the significance of the present study. Specifically, the study focuses on EFL learning in the Chinese tertiary education system. The rich Confucian tradition in China places a strong emphasis on achievement through diligent effort (Stankov Citation2010), which naturally encourages the development of a growth mindset among language learners. Concurrently, the Chinese education system is characterised by pronounced competitiveness and achievement orientations (Cai and Liem Citation2017). The salience of academic grades and the pursuit of distinction within the eyes of influential figures, such as teachers and parents, fosters the adoption of performance-related goals among students (Li et al. Citation2022). These unique contextual features would yield a nuanced interplay of language mindset and achievement goals as well as their influence on Chinese EFL learners’ emotional experience in L2 learning.

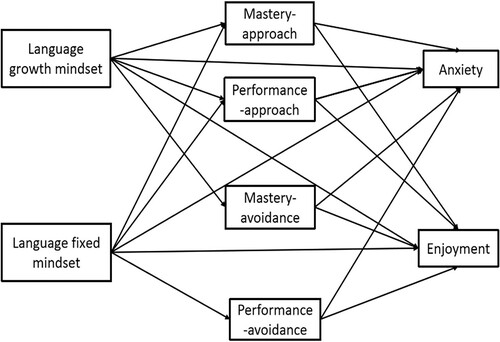

Drawing upon the LMMS framework and relevant literature in both SLA and educational psychology, we formulated a mediation model (see ) that hypothesises relationships in the Chinese EFL context. Specifically, for the relationship between language mindset and achievement goals, we propose that

H1a. Growth language mindset would lead to higher level of mastery-approach goal;

H1b. Growth language mindset would lead to higher level of mastery-avoidance goal;

H1c. Growth language mindset would lead to higher level of performance-approach goal;

H1d. Fixed language mindset would lead to higher level of performance-approach;

H1e. Fixed language mindset would lead to higher level of performance-avoidance goal;

H1f. Fixed language mindset would lead to lower level of mastery-approach goal.

Regarding the relationship between language mindsets and L2 emotions, we propose that

H2a. Growth language mindset would be directly linked to heightened enjoyment;

H2b. Growth language mindset would be directly linked to reduced anxiety;

H2c. Fixed language mindset would be directly linked to reduced enjoyment;

H2d. Fixed language mindset would be directly linked to heightened anxiety.

Regarding the mediating role of achievement goals, generally, we propose that

H3a. Mastery-approach goal would mediate the relationship between growth language mindset and L2 enjoyment and anxiety;

H3b. Mastery-avoidance goal would mediate the relationship between growth language mindset and L2 enjoyment and anxiety;

H3c. Performance-approach goal would mediate the relationship between growth language mindset and L2 enjoyment and anxiety;

H3d. Performance-avoidance goal would mediate the relationship between fixed language mindset and L2 enjoyment and anxiety;

H3e. Performance-approach goalwould mediate the relationship between fixed language mindset and L2 enjoyment and anxiety;

H3f. Mastery-approach goal would mediate the relationship between fixed language mindset and L2 enjoyment and anxiety;

Method

Participants

A total of 392 freshmen (231 males, 141 females, and 20 unidentified) who were non-English majors from a comprehensive university in Beijing China participated in the questionnaire survey. These students were taking a compulsory college English course. The participants’ ages ranged from 16 to 21 years (M = 18.31, SD = .647).

Instrument

To capture quantitative data on the variables of interest, a composite questionnaire was administered. This questionnaire encompassed language mindset, achievement goals, and two L2 emotions – enjoyment and anxiety. Additionally, participants’ background information such as gender, age, and education level was collected. To minimise potential cognitive burden on the participants, we utilised a 6-point Likert scale ranging from ‘1 (strongly disagree)’ to ‘6 (strongly agree)’ in all the scales. The scales were translated into Chinese by the first author. A pilot study was conducted among two applied linguists and 10 university students to ascertain the questionnaire’s facial validity. Adjustments were made based on their feedback. All scales demonstrated high reliability, as indicated by the high value of Cronbach’s (α) (see ). The complete composite questionnaire in both Chinese and English can be found in the Appendix.

Table 1. Descriptive analysis of all the variables (N = 392).

Language mindset inventory (LMI)

The second language aptitude (L2B) section of Lou and Noels’ (Citation2019) LMI was employed to assess students’ language mindsets. The inventory consists of 6 items that reflect beliefs concerning second language aptitude beliefs. Sample items include: ‘It is difficult to change how good you are at foreign languages’ (fixed language mindset); ‘You can always change your foreign language ability.’ (growth language mindset). The Cronbach’s (α) of the subscale is .857. The structural validity was confirmed with satisfactory CFA results (χ2/df = 12.559/5, p = .028; CFI = .990; TLI = .970; RMSEA = .063) in the present study. All item parameter estimates were significant (p < .001), and the standardised loadings were >.597, indicating acceptable convergent validity (Stevens Citation2002).

Achievement goal questionnaire-revised (AGQR)

Elliot and Murayama’s (Citation2008) AGQR was used to assess students’ achievement goals. The questionnaire items were slightly adapted to suit the context of English learning. Three items assessed each type of achievement goal. Example items include ‘My goal is to learn as much as possible in my English classes’ (mastery-approach); ‘I am afraid I won’t learn everything I need to learn in my English classes’ (mastery- avoidance); ‘I strive to do well compared to other students in my English class’ (performance-approach) and ‘My goal is to avoid performing worse than other students in my English class’ (performance-avoidance). Cronbach’s α values for the global AGQR, the subscales of the performance-avoidance goal, mastery-approach goal, mastery-avoidance goal, and performance-approach goal were .880, .804, .792, .872 and .792, respectively. The validity is also good as indicated by CFA results (χ2/df = 121.799/48, p < .001; CFI = .963; TLI = .949; RMSEA = .063; SRMR = .041). All item parameter estimates were significant (p < .001), and the standardised loadings were > .443.

Foreign language enjoyment scale

The Chinese version of the Foreign Language Enjoyment Scale (CFLES) (Li, Jiang, and Dewaele Citation2018) with 11 items was employed to gauge students’ L2 enjoyment. The scale has three factors: Foreign Language Enjoyment (FLE)-Private, FLE-Teacher and FLE-Atmosphere. The scale has demonstrated high reliability and validity in previous studies (e.g. Li, Huang, and Li Citation2021). In the current study, Cronbach’s α values for the global CFLES, the subscales of FLE – Private, FLE-Teacher and FLE-Atmosphere were .865, .855, .874, and .770, respectively, indicating high internal consistencies. The validity is also good as indicated by CFA results (χ2/df = 114.359/31, p < .001; CFI = .963; TLI = .934; RMSEA = .080; SRMR = .067). All item parameter estimates were significant (p < .001), and the standardised loadings were > .401.

Foreign language classroom anxiety scale (FLCAS)

A reduced scale of the FLCAS (Dewaele et al. Citation2017) was utilised to measure students’ L2 anxiety. The scale comprises eight items that reflect physical symptoms of anxiety, nervousness and lack of confidence. The scale demonstrated good internal reliability (Cronbach α = .842, n = 8) and construct validity (χ2/df = 45.023/18, p < .001; CFI = .977; TLI = .964; RMSEA = .062; SRMR = .032) in the present study. All item parameter estimates were significant (p < .001), and the standardised loadings were >.40.

Data collection

This study was approved by the human ethics review committee of the university that the first two researchers are affiliated to. Convenience sampling was adopted. Data collection was conducted by the first author, with the assistance of her colleagues. During class breaks, the researcher visited her colleagues’ classes and shared an online questionnaire through the class WeChat group, a social networking platform. Before they filled out the questionnaire, participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of their participation, and the anonymity of their responses. Subsequently, red packets with random amounts of cash value were distributed as tokens of appreciation. Originally, a total of 413 students participated in this study. However, 21 participants’ responses (5.08%) were excluded as invalid data due to their inattentiveness, as evidenced by a failure rate exceeding 80% on trap questions (Liu and Wronski Citation2018). The final dataset thus consisted of 392 participants.

Data analysis

Before data analysis, we adopted a meticulous screening process for assessing data suitability by examining normality, outliers, and missing data. The skewness and kurtosis values of the variables were examined to assess normality.

The data analysis utilised Mplus 7.0 software with Robust Maximum Likelihood Estimator (MLR). Path analysis modelling was employed due to its inherent capability to construct and evaluate complex causal relationships between variables (Kline Citation2016).

To assess the adequacy of the model, a set of established fit statistics were employed. The fit statistics considered were: Chi-square (p > .05 is a good fit), the comparative fit index (CFI > .95 is good fit), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI > .95 is good fit) (Hu and Bentler Citation1999; Marsh, Hau, and Wen Citation2004), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .08 is good fit), and standardised root mean square residual (SRMR < .08) (Kline Citation2016).

Results

Preliminary results

As delineated in , most variables demonstrated acceptable univariate normality, with skewness and kurtosis values ranged between −2 and 2 (George and Mallery Citation2010). However, the mastery-approach goal had a kurtosis value of 2.327, slightly exceeding the value of 2. To address this minor departure from normality, we employed the Robust Maximum Likelihood estimation for path analysis, chosen for its ability to provide unbiased estimates even with slight non-normal variables (Bentler Citation2006).

displays Spearman’s rank correlation among the variables. Notably, a significant negative correlation emerges between growth and fixed language mindset. A growth language mindset exhibits a positive correlation with L2 enjoyment and a negative correlation with L2 anxiety. Conversely, fixed language mindset correlates negatively with L2 enjoyment and positively with L2 anxiety. Regarding language mindsets and achievement goals, growth language mindset correlates significantly with the mastery-approach and mastery-avoidance goals but not with performance goals. In contrast, a fixed language mindset negatively correlates with the mastery-approach goal and positively with the performance-avoidance goal. Additionally, L2 enjoyment correlates positively with both mastery goals and the performance-approach goal, whereas L2 anxiety negatively correlates with the mastery-approach goal and positively with performance-avoidance and mastery-avoidance goals.

Table 2. Correlation coefficients among all the variables.

Path analysis

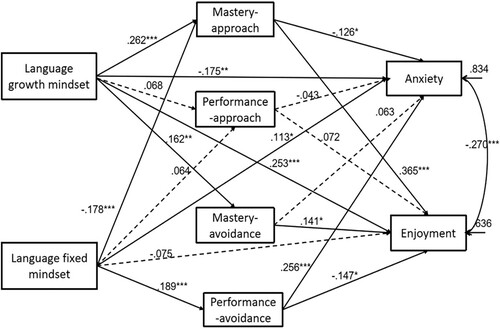

We used path analysis to test the hypothesised theoretical model (see ). Although there were six non-significant paths (i.e. paths from growth and fixed language mindsets to performance-approach goal, from fixed language mindset and performance-approach goal to enjoyment, and from performance-approach goal and mastery-avoidance goal to anxiety) (see ), the results showed that this model provided a robust fit to the data (χ2 = 3.963, df = 2, p = .1379, CFI = .996, TLI = .947, RMSEA = .05, and SRMR = .023, AIC = 5966.174, BIC = 6113.111). Thus, we accepted the theoretical model as our final model (see ).

Figure 2. Theoretical model with standard estimated coefficients.

Note: All coefficients are consistently put at the upper of the corresponding path. For clearer vision, the correlation and coefficients between the achievement goals were not presented. The dotted arrows represent the insignificant paths; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Direct effects

provides a more comprehensive view of the direct path coefficients. In support of H1a and H1b, a growth language mindset demonstrated strong and moderate positive predictions for both the mastery-approach goal (β = .262, t = 5.270, p < .001) and the mastery-avoidance goal (β = .162, t = .3272, p < .01), respectively, as per Keith’s (Citation2006) thresholds: β < .10 indicating a small effect, .10 < β < .25 indicating a moderate effect, and β > .25 indicating a large effect. Rejecting H1c growth language mindset’s association with the performance-approach goal was not significant. In support of H1e and H1f, a fixed language mindset moderately predicted the performance-avoidance goal (β = .189, t = 4.186, p < .001) positively and the mastery-approach goal (β = −.178, t = −3.939, p < .001) negatively, but its prediction on performance-approach goal was also not significant (β = .048, t = .363, p < .05), rejecting H1d.

Table 3. Robust maximum likelihood estimates for direct effects.

In congruence with H2a and H2b, growth language mindset exhibited a strong positive effect on enjoyment (β = .253, t = 5.410, p < .001) and a moderate negative influence on anxiety (β = −.175, t = −3.368, p < .01). Conversely, fixed language mindset showed a moderate positive effect on anxiety (β = .113, t = 2.103, p < .05), supporting H2d, but its relationship with enjoyment was not significant (β = −.075, t = −1.834, p > .05), rejecting H2c.

Mediating effect of achievement goals

Hypotheses concerning the mediating effects of achievement goals are partially supported (see ). As depicted in , four out of the six anticipated paths from the two mindsets to the four achievement goals proved statistically significant, with the exception of the paths from both fixed and growth language mindsets to the performance-approach goal. Among the four achievement goals, five out of eight paths exhibited significant effects on the two emotions, except for the paths from the performance-approach goal to anxiety and enjoyment, as well as from the mastery-avoidance goal to anxiety. This implies that the two mindsets exerted indirect effects on achievement emotions via mastery-approach, mastery-avoidance and performance-avoidance goals among Chinese EFL learners.

Table 4. Robust maximum likelihood estimates for the indirect effects.

More specifically, in support of H3a, growth mindset yielded small positive indirect effects on enjoyment (β = .095, 95% CI = [.045, .130]) and and small negative indirect effects on anxiety (β = −.033, 95% CI = [−.079, −.003]) through the mastery-approach goal. The mediating role of both mastery-avoidance and performance approach goals were not significant, rejecting H3b and H3c.

For fixed language mindset, partially in support of H3d, it produced small negative indirect effects on enjoyment (β = −.028, 95% CI = [−.044, −.007]) and a small positive indirect effect on anxiety (β = .048, 95% CI = [.017, .080]) through the performance-avoidance goal, supporting H3d. Partially in support of H3f the fixed language mindset produced a small negative effect on enjoyment through the mastery-approach (β = −.065, 95% CI = [−.087, −.024]). The mediating role of performance-approach goal was not significant, rejecting H3e.

Discussion

The present study delved into the associations between Chinese EFL learners’ language mindset, achievement goals, and the two L2 emotions and extended the LMMS framework by incorporating the mastery-avoidance goal. The mediation model proposed in this study received partial support, offering both theoretical insights into, and practical implications for, L2 researchers and educators.

Direct effects of language mindsets on achievement goals

Consistent with the theoretical LMMS framework, our findings corroborated findings that a growth language mindset positively predicted the mastery-approach and mastery-avoidance goals supporting H1a and H1b, but its prediction of the performance-approach goal was not significant. This resonates with previous research indicating that individuals with a growth mindset on average prefer to adopt goals centred around learning and mastery (Lou and Noels Citation2016, Citation2017; Papi et al. Citation2019). Although some with a growth mindset would also set the performance-approach goal (Yu and McLellan Citation2020), our finding indicates that this might not occur to individuals on average. Conversely, a fixed language mindset positively predicts the performance-avoidance goal and negatively predicts the mastery-approach goal, supporting H1e and H1f. These observations align with the notion that individuals endorsing a fixed mindset prefer to set performance goals that are concerned with avoiding revealing their incompetence over genuine learning (De Castella and Byrne Citation2015; Dweck Citation1999). The finding also provides evidence that a fixed mindset would lead to a lower level of mastery-approach goal, especially when coupled with low perceived language ability (Yu and McLellan Citation2020). These findings collectively underscore the influential roles that growth and fixed language mindsets play in shaping learners’ goal pursuits.

It was unexpected that neither a fixed nor a growth language mindset significantly predicted performance-approach goal, rejecting both H1c and H1d. This lack of association might be influenced by the cultural context of the present study. In China, the predominant goal for high school students is to achieve a high score in the National College Entrance Exam (NCEE, also known as Gaokao) to secure an ideal university (Kirkpatrick and Zang Citation2011). However, once students enter university, the Gaokao objective is no longer applicable. Chinese university students typically exhibit a moderate level of performance-approach goal (e.g. Li et al. Citation2022), as supported by the present study, where the performance-approach goal also garnered the lowest mean score (M = 3.137, SD = 1.064) among the four achievement goals.

Direct effects of language mindsets on L2 enjoyment and anxiety

In consonance with prior investigations (Lou and Noels Citation2020; Wang, Peng, and Patterson Citation2021), our study further validated the association between language mindsets and emotions. Specifically, it was reaffirmed that a growth language mindset positively affects L2 enjoyment and negatively affects L2 anxiety, supporting H2a and H2b. In contrast, a fixed language mindset exhibited a positive prediction on anxiety, supporting H2b. These findings support the LMMS framework (Lou and Noels Citation2019), meaning that individuals with a growth language mindset value effort in language learning, thereby enjoying the learning process while having a better sense of control towards success and experiencing lower anxiety. Conversely, individuals with a fixed language mindset tend to perceive language learning ability as innate, thereby anchoring their self-perception to test outcomes or performance, which can elicit feelings of anxiety. The relationship between a fixed language mindset and enjoyment, on the other hand, follows a more nuanced trajectory. Previous research has suggested that learners with a fixed language mindset may perceive their efforts as less productive (Zarrinabadi et al. Citation2022), potentially impacting their capacity to derive pleasure from the learning process. This notion is substantiated by the negative correlation between fixed mindset and enjoyment identified in our study. However, the association was not statistically significant in the path analysis, rejecting H2c. This divergence could potentially be attributed to the interplay with the specific achievement goals that participants set for English learning, a facet that warrants further exploration. The subsequent discussion shifts to exploring the nuanced connections between language mindset, achievement goals, and L2 emotions.

Mediating role of achievement goals

Generally aligning with the LMMS framework, we found language mindsets shape learners’ adoption of different types of achievement goals, which, in turn, affect learners’ L2 emotions. Specifically, supporting H3a, we found that a growth language mindset predicted mastery-approach goal, subsequently leading to lower anxiety and heightened enjoyment. These findings mirror previous studies (Papi et al. Citation2019; Yao et al. Citation2021). The convergence of a growth mindset and mastery-approach goal imbues learners with optimism, motivation and a propensity to view setbacks as opportunities for personal growth, leading to heightened enjoyment and lower anxiety.

Partially in support of H3b, our findings demonstrated that a growth language mindset also significantly fostered enjoyment through the mastery-avoidance goal, but the mediation role of mastery-avoidance on anxiety was not significant, as the predictive link from the mastery-avoidance goal to anxiety did not attain significance. These findings diverge from prior assumptions that a mastery-avoidance goal would diminish enjoyment (Elliot and Pekrun Citation2007) and are contradictory to previous empirical findings that the mastery-avoidance would amplify anxiety (Li and Li Citation2024). This apparent contradiction might be attributed to the intricate conceptual composition of the mastery-avoidance goal. The mastery-avoidance goal has a composite structure (Huang Citation2011). This structure encompasses both an optional mastery component, involving the use of relatively stable self-referent criteria for competence evaluation, and a non-optimal avoidance component that focuses on evading negative possibilities. This confluence of optimal and non-optimal components might potentially yield an offsetting effect on emotions (Elliot and McGregor Citation2001). This nuanced profile might contribute to the varying impact observed on levels of L2 enjoyment and anxiety. Future studies could gain deeper insight by exploring the role of the mastery-avoidance goal in more comprehensive ways, taking into account its interaction with various mediators like control-value appraisals (Li and Li Citation2024).

Supporting H3d, our study substantiated that a fixed language mindset negatively affected enjoyment and positively affected anxiety through performance-avoidance. Furthermore, partially supporting H3f, our study revealed that a fixed language mindset also had a negative impact on enjoyment through the mastery-approach goal. These findings align with prior research illustrating that students with a fixed language mindset tend to set goals aimed at avoiding revealing their incompetence rather than pursuing genuine learning (De Castella and Byrne Citation2015; Yao et al. Citation2021). This tendecy subsequently contributes to negative emotions and undermining positive emotions (Dong Citation2022). Performance-avoidance goal, in sharp contrast to mastery-approach goal, has consistently demonstrated predictive power in eliciting negative emotions and diminished positive emotions (Feng, Wang, and King Citation2023). This reveals that students holding a fixed language mindset, coupled with a high performance-avoidance goal and low mastery-approach goal, tend to interpret failures as indicators of limited ability, resulting in heightened vulnerability in self-perception which leads to anxiety and decreased enjoyment in language learning (Lou and Noels Citation2020).

In contradiction to H3c and H3e, the performance-approach goal did not mediate the relationship between growth or fixed mindset and the two L2 emotions, as both language mindsets did not predict the performance-approach goal significantly. We further found that this goal was not significantly predictive of either enjoyment or anxiety. These findings contradict prior research that indicates the performance-approach goal’s positive association with enjoyment and negative association with anxiety (Feng, Wang, and King Citation2023) but align with Li and Li’s (Citation2024) finding that the performance-approach goal was not directly predictive of enjoyment or anxiety. Apart from the possible moderating cultural background as discussed in the previous section, there is another noteworthy explanation for the unstable and controversial role of the performance-approach goal. Research found that when students hold this goal autonomously, it can be adaptive; however, when driven by controlled reasons, students become less adaptive (Li et al. Citation2022). There can be other moderating factors affecting the role of the performance-approach goal, for example, Li and Li (Citation2024) found that the impact of the performance-approach goal on enjoyment and anxiety was fully mediated by learners’ control-value appraisals. Our findings provide further evidence of the unstable impact of the performance-approach goal on achievement emotions (Hall et al. Citation2016). This volatility might also arise from the nuanced conceptual composition of the performance-approach goal. Similar to the mastery-avoidance goal, it might involve offsetting effect from the positive component of approach (i.e. directing behaviour towards positive stimuli, Elliot and Murayama Citation2008) and the negative component of performance, which guides the individuals to use unstable normative referent such as outperforming others to evaluate success and to put their sense of self on the line (Linnenbrink-Garcia and Barger Citation2014).

Generally, our findings validated the applicability of the framework of LMMS among Chinese tertiary EFL learners. Through our exploration, we can also see the unique role of the mastery-avoidance goal in predicting L2 anxiety and L2 enjoyment, as well as its mediating role between a growth mindset and the two emotions. Therefore, future research in SLA should not only differentiate between approach and avoidance orientations for performance goals but also for mastery goals, recognising the distinct impact of each on learners’ emotional experiences and goal pursuits.

Pedagogical implications and limitations

Given the importance of language learners’ emotional experience in L2 learning (Dewaele and Li Citation2022), the present findings yield some important implications for educational practitioners. First, this research highlighted the profound impact of a growth mindset on fostering the adoption of mastery goals and nurturing positive emotional experiences among language learners. Language educators can strategically integrate mindset-related tasks and activities into the L2 lesson plans, effectively conveying the malleability of language learning ability through compelling examples as used in Lou and Noels (Citation2016; Citation2019). This approach not only creates engaging learning experiences but also promotes a growth mindset that positively influences the adoption of achievement goal and emotional well-being (Lou and Noels Citation2019). Second, our findings emphasised the significance of the mastery-approach goal in mediating the impact of both language mindsets on L2 anxiety and enjoyment. A mastery-oriented learning environment, accentuating in-depth learning and recognising learners’ efforts, can effectively nurture a mastery-approach goal orientation (Miller and Murdock Citation2007).

Several limitations warrant consideration with regard to the present study. First, the utilisation of convenience sampling and the relatively small sample size raise concerns about the generalizability of our findings. Second, the cross-sectional design, reliant on quantitative data, inherently limits the depth and breadth of insights into the intricate relationships among language mindsets, achievement goals and L2 emotions. Further research endeavours could be enriched by incorporating qualitative methods such as interview and classroom observation, offering a more nuanced picture of such relationships and their potential underlying mechanisms. Lastly, the present study focused exclusively on L2 enjoyment and anxiety as outcomes of language mindset and achievement goals, thereby leaving unexplored a multitude of other emotions commonly experienced by language learners, such as boredom, hope, pride, and shame. Future investigations into these emotions within the framework of LMMS in L2 learning could yield more valuable insights.

Conclusion

Our research enhances the LMMS framework through the integration of the mastery-avoidance goal and verifies its applicability in the Chinese EFL context. Our study further clarifies the links between language mindsets and achievement goals and deepens the comprehension of the relationship between language mindsets, achievement goals, L2 enjoyment, and L2 anxiety within the realm of EFL learning in China. By shedding light on how language mindsets influence the adoption of achievement goals, subsequently shaping language learners’ L2 enjoyment and anxiety, we contribute to the ongoing exploration of the impact of achievement goals on L2 emotions and the influence of language mindsets on L2 emotions, and the instigation mechanism of L2 enjoyment and anxiety. These insights hold practical implications for educational practitioners seeking to enhance learners’ emotional well-being. By incorporating mindset-related materials and cultivating a mastery-oriented classroom environment that values deep learning and efforts, educators can foster a conducive atmosphere for cultivating positive emotional experiences among learners.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baranik, L. E., L. J. Stanley, B. H. Bynum, and C. E. Lance. 2010. “Examining the Construct Validity of Mastery-Avoidance Achievement Goals: A Meta-Analysis.” Human Performance 23 (3): 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2010.488463.

- Bentler, P. M. 2006. EQS 6 Structural Equations Program Manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software.

- Botes, E., J. M. Dewaele, and S. Greiff. 2020. “The Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale and Academic Achievement: An Overview of the Prevailing Literature and a Meta-Analysis.” Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning 2 (1): 26–56. https://doi.org/10.52598/jpll/2/1/3.

- Burnette, J. L., E. H. O'Boyle, E. M. VanEpps, J. M. Pollack, and E. J. Finkel. 2013. “Mind-sets Matter: A Meta-Analytic Review of Implicit Theories and Self-Regulation.” Psychological Bulletin 139 (3): 655–701. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029531.

- Cai, E. Y. L., and G. A. D. Liem. 2017. “‘Why do I Study and What do I Want to Achieve by Studying?’ Understanding the Reasons and the Aims of Student Engagement.” School Psychology International 38 (2): 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034316686399.

- Csikszentmihalhi, M. 1997. Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books.

- Daniels, L. M., R. H. Stupnisky, R. Pekrun, T. L. Haynes, R. P. Perry, and N. E. Newall. 2009. “A Longitudinal Analysis of Achievement Goals: From Affective Antecedents to Emotional Effects and Achievement Outcomes.” Journal of Educational Psychology 101 (4): 948–963. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016096.

- De Castella, K., and D. Byrne. 2015. “My Intelligence may be More Malleable than Yours: The Revised Implicit Theories of Intelligence (Self-Theory) Scale is a Better Predictor of Achievement, Motivation, and Student Disengagement.” European Journal of Psychology of Education 30 (3): 245–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-015-0244-y.

- Deemer, E. D., M. P. Martens, and E. J. Podchaski. 2007. “Counseling Psychology Students’ Interest in Research: Examining the Contribution of Achievement Goals.” Training and Education in Professional Psychology 1:193–203.

- Derakhshan, A., and J. Fathi. 2024. “Growth Mindset, Self-Efficacy, and Self-Regulation: A Symphony of Success in L2 Speaking.” System 123:103320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2024.103320.

- Derakhshan, A., and H. Yin. 2024. “Do Positive Emotions Prompt Students to be More Active? Unraveling the Role of Hope, Pride, and Enjoyment in Predicting Chinese and Iranian EFL Students' Academic Engagement.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2024.2329166.

- Dewaele, J. M., E. Botes, and S. Greiff. 2023. “Sources and Effects of Foreign Language Enjoyment, Anxiety, and Boredom: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition 45: 461–479.

- Dewaele, J. M., and C. Li. 2022. “Foreign Language Enjoyment and Anxiety: Associations with General and Domain-Specific English Achievement.” Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics 45 (1): 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1515/CJAL-2022-0104.

- Dewaele, J. M., and P. D. MacIntyre. 2014. “The two Faces of Janus? Anxiety and Enjoyment in the Foreign Language Classroom.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 4: 237–274.

- Dewaele, J. M., and P. D. MacIntyre. 2016. “Foreign Language Enjoyment and Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety. The Right and Left Feet of FL Learning?” In Positive Psychology in SLA, edited by P. D. MacIntyre, T. Gregersen, and S. Mercer, 215–236. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Dewaele, J., J. Witney, K. Saito, and L. Dewaele. 2017. “Foreign Language Enjoyment and Anxiety: The Effect of Teacher and Learner Variables.” Language Teaching Research 22 (6): 676–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817692161.

- Dong, L. 2022. “Mindsets as Predictors for Chinese Young Language Learners’ Negative Emotions in Online Language Classes During the Pandemic: Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2159032.

- Dweck, C. S. 1999. Self-theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development. Hove: Psychology Press.

- Dweck, C. S., and D. C. Molden. 2017. “Mindsets: Their Impact on Competence Motivation and Acquisition.” In Handbook of Competence and Motivation: Theory and Application, 2nd ed., edited by A. J. Elliot, C. S. Dweck, and D. S. Yeager, 135–154. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Elliot, A. J., and M. A. Church. 1997. “A Hierarchical Model of Approach and Avoidance Achievement Motivation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 72 (1): 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.218.

- Elliot, A. J., and J. M. Harackiewicz. 1996. “Approach and Avoidance Achievement Goals and Intrinsic Motivation: A Mediational Analysis.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70: 461–475.

- Elliot, A. J., and H. A. McGregor. 2001. “A 2 × 2 Achievement Goal Framework.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 80:501–519.

- Elliot, A. J., and K. Murayama. 2008. “On the Measurement of Achievement Goals: Critique, Illustration, and Application.” Journal of Educational Psychology 100 (3): 613–628. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.3.613.

- Elliot, A. J., and R. Pekrun. 2007. “Emotion in the Hierarchical Model of Approach-Avoidance Achievement Motivation.” In Emotion in Education, edited by P. A. Schutz and R. Pekrun, 57–73. Burlington: Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012372545-5/50005-8.

- Feng, E., Y. Wang, and R. B. King. 2023. “Achievement Goals, Emotions and Willingness to Communicate in EFL Learning: Combining Variable and Person-Centered Approaches.” Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221146887.

- George, D., and M. Mallery. 2010. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 17.0 Update. 10th Edition. Boston: Pearson.

- Hall, N. C., L. Sampasivam, K. R. Muis, and J. Ranellucci. 2016. “Achievement Goals and Emotions: The Mediational Roles of Perceived Progress, Control, and Value.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 86 (2): 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12108.

- Harackiewicz, J. M., K. E. Barron, J. M. Tauer, and A. J. Elliot. 2002. “Predicting Success in College: A Longitudinal Study of Achievement Goals and Ability Measures as Predictors of Interest and Performance from Freshman Year Through Graduation.” Journal of Educational Psychology 94 (3): 562–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.3.562.

- Hu, L., and P. M. Bentler. 1999. “Cutoff Criteria for fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus new Alternatives.” Structural Equation Modeling 6 (1): 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Huang, C. 2011. “Achievement Goals and Achievement Emotions: A Meta-Analysis.” Educational Psychology Review 23 (3): 359–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9155-x.

- Keith, T. Z. 2006. Multiple Regression and Beyond. New York: Pearson Education.

- Khajavy, G. H., F. Pourtahmasb, and C. Li. 2022. “Examining the Domain-Specificity of Language Mindset: A Case of L2 Reading Comprehension.” Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 16 (3): 208–220.

- Kirkpatrick, R., and Y. Zang. 2011. “The Negative Influences of Exam-Oriented Education on Chinese High School Students: Backwash from Classroom to Child.” Language Testing in Asia 1 (3): 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1186/2229-0443-1-3-36.

- Kline, R. B. 2016. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 4th ed. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Li, B., and C. Li. 2024. “Achievement Goals and Emotions of Chinese EFL Students: A Control- Value Theory Approach.” System https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2024.103335.

- Li, B., and J. Xu. 2014. “Achievement Goals Orientation and Autonomous English Learning Ability: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy.” Foreign Languages in China 11 (3): 59–68. https://doi.org/10.13564/j.cnki.issn.1672-9382.2014.03.009.

- Li, B., J. E. Turner, J. Xue, and J. Liu. 2022. “When are Performance-Approach Goals More Adaptive? It Depends on Their Underlying Reasons.” International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 61 (4): 1607–1638. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2021-0208.

- Li, B., L. Ma, Y. Zeng, and J. Zhang. 2023. “Latent Profile Analysis of the Relationship Between Second Language Mindset and Foreign Language Emotions.” Modern Foreign Languages 46 (4): 527–539.

- Li, C., G. Jiang, and J.-M. Dewaele. 2018. “Understanding Chinese High School Students’ Foreign Language Enjoyment: Validation of the Chinese Version of the Foreign Language Enjoyment Scale.” System 76:183–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.06.004.

- Li, C., J. Huang, and B. Li. 2021. “The Predictive Effects of Classroom Environment and Trait Emotional Intelligence on Foreign Language Enjoyment and Anxiety.” System 96:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102393.

- Li, C., J. M. Dewaele, and G. Jiang. 2020. “The Complex Relationship Between Classroom Emotions and EFL Achievement in China.” Applied Linguistics Review 11:485–510.

- Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., and M. M. Barger. 2014. “Achievement Goals and Emotions.” In Handbook of Emotions in Education, edited by R. Pekrun and L. Linnenbrink-Garcia, 142–161. New York: Taylor& Francis.

- Liu, M., and L. Wronski. 2018. “Trap Questions in Online Surveys: Results from Three web Survey Experiments.” International Journal of Market Research 60 (1): 32–49.

- Lou, N. M., and K. A. Noels. 2016. “Changing Language Mindsets: Implications for Goal Orientations and Responses to Failure in and Outside the Second Language Classroom.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 46: 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.03.004.

- Lou, N. M., and K. A. Noels. 2017. “Measuring Language Mindsets and Modeling Their Relations with Goal Orientations and Emotional and Behavioral Responses in Failure Situations.” The Modern Language Journal 101 (1): 214–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12380.

- Lou, N. M., and K. A. Noels. 2019. “Promoting Growth in Foreign and Second Language Education: A Research Agenda for Mindsets in Language Learning and Teaching.” System, 86, 102126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.102-126.

- Lou, N. M., and K. A. Noels. 2020. “Language Mindsets, Meaning-Making, and Motivation.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Motivation for Language Learning, edited by M. Lamb, K. Csizér, A. Henry, and S. Ryan, 537–559. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- MacIntyre, P. D. 1999. “Language Anxiety: A Review of the Research for Language Teachers.” In Affect in Foreign Language and Second Language Learning, edited by D. Young, 24–46. Boston: MacGraw-Hill College.

- MacIntyre, P. D. 2017. “2. An Overview of Language Anxiety Research and Trends in its Development.” In New Insights into Language Anxiety: Theory, Research and Educational Implications, edited by C. Gkonou, M. Daubney, and J. Dewaele, 11–30. Blue Ridge Summit. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783097722-003.

- MacIntyre, P. D., and T. Gregersen. 2012. “Emotions That Facilitate Language Learning: The Positive-Broadening Power of the Imagination.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 2: 193–213. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2012.2.2.4.

- Marsh, H. W., K. T. Hau, and Z. Wen. 2004. “In Search of Golden Rules: Comment on Hypothesis-Testing Approaches to Setting Cutoff Values for fit Indexes and Dangers in Overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler's (1999) Findings.” Structural Equation Modeling 11 (3): 320–341. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2.

- Miller, A. D., and T. B. Murdock. 2007. “Modeling Latent True Scores to Determine the Utility of Aggregate Student Perceptions as Classroom Indicators in HLM: The Case of Classroom Goal Structures.” Contemporary Education Psychology 32:83–104.

- Ozdemir, E., and M. Papi. 2021. “Mindsets as Sources of L2 Speaking Anxiety and Self-Confidence: The Case of International Teaching Assistants in the US.” Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 16(3): 234–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2021.1907750.

- Papi, M., A. Rios, H. Pelt, and E. Ozdemir. 2019. “Feedback-seeking Behavior in Language Learning: Basic Components and Motivational Antecedents.” Modern Language Journal 103 (1): 205–226.

- Pekrun, R., A. J. Elliot, and M. A. Maier. 2006. “Achievement Goals and Discrete Achievement Emotions: A Theoretical Model and Prospective Test.” Journal of Educational Psychology 98: 583–597.

- Pekrun, R., M. A. Maier, and A. J. Elliot. 2009. “Achievement Goals and Achievement Emotions: Testing a Model of Their Relations with Academic Performance.” Journal of Educational Psychology 100 (1): 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013383.

- Peng, J. 2014. Willingness to Communicate in the Chinese EFL University Classroom: An Ecological Perspective. Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters.

- Putwain, D. W., P. Sander, and D. Larkin. 2013. “Using the 2×2 Framework of Achievement Goals to Predict Achievement Emotions and Academic Performance.” Learning and Individual Differences 25: 80–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2013.01.006.

- Seligman, M. E. P., and M. Csikszentmihalyi. 2000. “Positive Psychology: An Introduction.” American Psychologist 55:5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5.

- Stankov, L. 2010. “Unforgiving Confucian Culture: A Breeding Ground for High Academic Achievement, Test Anxiety and Self-Doubt?” Learning and Individual Differences 20 (6): 555–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2010.05.003.

- Stevens, J. P. 2002. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences. 4th ed. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Teimouri, Y., J. Goetze, and L. Plonsky. 2019. “Second Language Anxiety and Achievement.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition 41 (2): 363–387. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263118000311.

- Turner, J. E., B. Li, and M. Wei. 2021. “Exploring Effects of Culture on Students’ Achievement Motives and Goals, Self-Efficacy, and Willingness for Public Performances: The Case of Chinese Students’ Speaking English in Class.” Learning and Individual Differences 85: 101–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101943.

- Wang, Y., A. Derakhshan, and L. J. Zhang. 2021. “Researching and Practicing Positive Psychology in Second/Foreign Language Learning and Teaching: The Past, Current Status and Future Directions.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721.

- Wang, H., A. Peng, and M. M. Patterson. 2021. “The Roles of Class Social Climate, Language Mindset, and Emotions in Predicting Willingness to Communicate in a Foreign Language.” System 99:102–529.

- Yao, Y., N. S. Guo, W. Wang, and J. Yu. 2021. “Measuring Chinese Junior High School Students’ Language Mindsets: What Can We Learn from Young EFL Learners’ Beliefs in Their Language Ability?” System 101:102–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102577.

- Yu, J., and R. McLellan. 2020. “Same Mindset, Different Goals and Motivational Frameworks: Profiles of Mindset-Based Meaning Systems.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 62: 101901.

- Zarrinabadi, N., M. Rezazadeh, M. Karimi, and N. M. Lou. 2022. “Why Do Growth Mindsets Make you Feel Better About Learning and Your Selves? The Mediating Role of Adaptability.” Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 16 (3): 249–264.

- Zhang, L. J. 2001. “Exploring Variability in Language Anxiety: Two Groups of PRC Students Learning ESL in Singapore.” RELC Journal 32 (1): 73–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/003368820103200105.