Abstract

The acknowledgement of politics and institutions in developing countries is well in line with debates not only in the area of development effectiveness but also regarding new public management. Results-Based Approaches (RBApps), conceptually framed within these two debates, are designed to support outcome- and impact-oriented development goals. They link the achievement of results to monetary and/or non-monetary reward mechanisms. However, so far, development cooperation partners have mainly applied RBApps in the form of Results-Based Finance and Results-Based Aid. Through the provision of a conceptual framework, this paper embeds RBApps between different tiers of government within the discussion and applies Rwanda as a case study to it. Along the lines of Rwanda’s Domestic Performance Approach Imihigo, the article argues that development co-operation should be more proactive in considering these approaches, as they might be crucial in terms of sustainability and serve as a promising entry point for programmes supported by development partners.

Introduction

The way the public sector is organised is a key aspect of all states in developing and developed regions alike. States are thus reflecting on the best ways to improve public sector performance. Though there is consensus regarding the importance of a functioning public sector for sustainable development, achieving results has proven to be difficult. So far, research on public sector reform efforts in developing countries, and especially on New Public Management (NPM) reforms, is limited and if available has yielded only mixed results.1

In a number of developing countries, not least in sub-Saharan Africa, states do not have a long tradition of public sector approaches. Faced with the increasing pressure placed on ‘value for money’, policymakers and researchers alike are therefore intensively engaged in developing innovative concepts for public sector reforms. Post-NPM approaches provide thereby a wealth of possibilities for experimentation and discovery.2 Moving the discourse to post-NPM approaches, this article argues that among those possibilities are Results-Based Approaches (RBApps) and the extension of the concept towards the inclusion of Domestic Performance Approaches (DPAs).3

RBApps can be defined as the connection of results to successive allocations of rewards.4 Their aim is to improve the public sector’s effectiveness and efficiency through the establishment of results-based reward modalities. The modalities set incentives and ideally steer public sector organisations towards the achievement of results that are beneficial to the public.

This article uses RBApps as a key term and concept and provides a theoretical framework to analyse RBApps based on actor constellations and common characteristics. It aims at broadening the definition of RBApps through the inclusion of DPAs, thereby addressing the aspect of contextual fit – a topic of great importance in post-NPM approaches and discussions on development effectiveness.5

Especially in the context of development co-operation debates, the application of RBApps has gained increasing levels of attention. Several development partners have started to pilot RBApps in the form of results-based aid (RBA) or results-based finance (RBF).6 However, these debates often neglect a domestic perspective and do not take the existence of DPAs into account.

Rwanda, a country that has made substantial progress in economic and social spheres, has introduced a DPA called Imihigo.7 Through the establishment of a conceptual and theoretical framework for DPAs, Imihigo serves as a case study to argue that development co-operation debates should be more proactive in considering these approaches.8 They might be crucial in terms of sustainability aspects and serve as a promising entry point for development co-operation, for example in the form of RBA and RBF.

Brief overview of conceptual debates

The concept of RBApps and the implied focus on performance can be framed in terms of public sector reform debates and in particular in relation to the application of NPM approaches. Public sector reforms relate to changes of government structures and processes in order to improve the functioning of public sector organisations.9 There have been various ideas and approaches as to how public sector organisations should be reformed to improve their performance, efficiency and effectiveness. These ideas are mainly derived from three intellectual threads: the movement away from structural adjustment programmes, the transition from central planning to market economies as well as from single-party systems to multi-party democracies, and most importantly the increasing usage of NPM approaches in the public sector.10

NPM approaches emerged in the early 1980s in the Anglo-Saxon context and introduced a performance component to the debate on public sector reforms.11 Performance is thereby understood as a concept encompassing the efficiency and effectiveness of a project.12 NPM approaches aim at improving service delivery by applying private sector management principles to government organisations.13 Through the lens of NPM approaches, government is increasingly embedding business aspects, focussing on being profitable where possible and cost conscious where not.14 Citizens are treated as customers and clients. Instead of focussing on inputs, public sector agencies and organisations are encouraged to focus on outputs and outcomes. Decentralisation is thereby seen as a means to achieve development goals and to improve the state’s performance – empowered local governments are expected to deliver basic public services in a more efficient, equitable and accountable fashion, as compared to central government agencies.15

Following the paths of developed countries coupled with international pressure led to the introduction of NPM approaches into developing countries in the 1990s.16 Their language and principles continue to inform current thinking about public sector reform.17 Therefore, performance nowadays is the core concern of public institutions and development partners in developing and developed countries alike.18

However, challenges to reform the public sector and improve its performance continue to exist in relation to the reform elements and the way they are arranged as well as the extent to which they facilitate culture or incentive changes and have spurred the consideration of post-NPM reform approaches.19 A key component is the consideration of the country’s political economy and institutions and thereby the ‘context-specific adaptations taking into account country capacities’.20 Goddard and Mkasiwa even argue that local ownership is key for the successful implementation of NPM rules and regulations.21

Conceptually based on NPM, the focus on the term ‘results’ emerged in debates revolving around development co-operation and aid effectiveness. Since the beginning of the 2000s, development partners faced an increasing pressure to be accountable, not only towards their partner countries but also towards their countries’ citizens. This intensified the need to present results and fostered the creation of concepts focussing on results.

The United Nations Millennium Declaration and the Millennium Development Goals were a first step towards a results orientation – they proclaimed a goal of development instead of offering the tools and instruments that needed to be taken up by governments in order to achieve it. As a result, one element that has been widely adopted within development co-operation is the logic model of a results chain.22 The results chain serves as a tool for planning, monitoring and evaluation with a focus on development outcomes and impacts. It defines the steps that have to be taken to achieve the desired results, with the purpose of improving efficiency and effectiveness.

In this context, aid effectiveness gained momentum. The movement towards delivering aid more effectively and the achievement of results reached a crucial milestone with the adoption of the Paris Declaration in 2005. The Paris Declaration affirmed the restructuring and improvement of international co-operation according to five core principles: ownership, alignment, harmonisation, managing for results and mutual accountability. It provided an innovative way to monitor progress of partner countries and development partners by establishing a set of principles and standards, building on lessons learnt in the past and promoting national ownership.23 Debates focussing on results reached their peak at the High Level Forum in Busan in 2011. Although good progress was made with regard to strengthening the partners’ accountability to manage aid for results, significantly less progress was made regarding the accountability mechanisms towards parliament and citizens.

Since Busan, the focus has shifted from aid effectiveness to development effectiveness, and fostered a re-orientation of development policies and politics towards the achievement and measurement of results instead of a focus on inputs and processes. Although the Aid Effectiveness Agenda lost its momentum, the introduced focus on performance and results continues to exist.24 Against this background, development partners developed and piloted RBApps, as they serve as an important instrument to account for results in times of economic crises and are used as a way to show that development co-operation is ‘value for money’: funds are only spent if results are achieved.25 Moreover, RBApps create the incentive to produce reliable performance information and help development partners to show measurable results to their citizens.26

RBApps: definition, actor constellations and characteristics

In defining RBApps, two relevant aspects provide the basis for the theoretical framework used in this article. First, RBApps can exist with different actor constellations.27 Second, RBApps share several common characteristics: they are based on a contract that entails agreement on the results to be achieved and the monitoring, evaluation and verification processes as well as the reward modalities.

Actor constellation

The first actor constellation is based on a contract between a national government and a development partner and is, as such, an aid modality. This form of RBApp is called RBA.28 Gaining popularity in the mid-2000s, RBA is innovative when compared to other forms of development aid, as rewards in the form of financial means are typically being disbursed ex post, upon the successful achievement of predefined targets, instead of being disbursed ex ante. Monetary incentive schemes are set up to help achieve key results. RBA defines the division of labour and responsibilities between the implementing partners differently when compared to several other development co-operation approaches. Ideally, it is a ‘hands-off’ approach for development partners (no or little direct implementing role), as it is the partner country that determines how to implement activities to achieve the results agreed upon and the capacities and means that are necessary to do so.29 RBA is rather new. So far, the concept has mainly been applied in pilot projects. Until now, no rigorous impact evaluations on RBA have been available.30 Some scholars thus question the effectiveness of these approaches.31

The second actor constellation refers to RBApps within a country and is based on a contract between different government entities, for example between national and sub-national government entities. Similar to RBA, rewards are typically disbursed ex post. Key results are achieved through monetary and/or non-monetary incentive schemes. This actor constellation differs from the previous one, as development partners are not involved, either in the development of the approach or in relation to the funding of the rewards. As such, the approach is not linked to development co-operation, but rather is a national approach used to improve public sector performance within a country. In the present article, this mechanism is referred to as a DPA.

Furthermore, international debates on RBApps identify a third constellation, which is based on a contract between a funder and a service provider. These approaches are referred to as RBF. The funder can be – but does not have to be – a development partner. On the one hand, RBF can thus be linked to development co-operation and exist as an aid modality. On the other hand, it can also exist as a national approach. Sub-national governments can thereby also act as service providers for the national government. Whereas RBA is a relatively new instrument and approach, RBF has existed in various countries since the 1980s, especially in the social sectors.32

Preferably, RBA and RBF should be based on country systems of partner countries.33 The use of country systems ideally encompasses the use of DPAs, if available. The embedment within the local context addresses criticism of NPM approaches and supports the fact that in the outcome document of the High Level Forum in Busan, the signing parties committed themselves to using country systems as the default approach to strengthen the partner’s ownership and sustainability.34 The advantage of using country systems, if they are available, lies essentially in the avoidance of building parallel structures, as they can carry the problem of insufficient country ownership and accountability.35

Characteristics

Regardless of their actor constellation, RBApps share several common characteristics, which are derived from the principles of NPM. These are visualised in and discussed in the following paragraphs.

Figure 1. “Results-Based Approaches (RBApps)” shared characteristics.

Source: Authors’ own compilation.

A pre-condition for the establishment of a RBApp is a contract between the two involved actors (a recipient and a funder). The contract outlines the actors’ responsibilities to reach the agreed-upon results and covers all administrative aspects, including, for example, the duration of the contract and the results to be achieved, as well as the evaluation approach and reward mechanism used. Ideally, the contract is transparent and publicly accessible to increase credibility and accountability of the agreement.

The contract defines the results to be achieved over a specific period in order to receive pre-identified rewards. Results therefore refer to the achievement of goals on the output, outcome and/or impact level.36 The achievement of results is then measured and rewarded, for example based on the achievement of planned targets and the progress made. The results need to be quantifiable and, ideally, achievable in incremental steps and monitored regularly (for example, annually) through appropriate indicators.37 Hence, the agreed-upon results need to be well integrated within a performance measurement system.

The contract thus also defines monitoring and evaluation processes to measure progress and entails an agreement with regard to the verification of progress presented.38 At the beginning of the evaluation period, baseline data has to be available and/or needs to be collected regarding the results to be achieved and the related performance indicators.

The recipient is usually responsible for collecting and reporting data on the progress of results, whereas the funder is responsible for arranging an independent audit to verify the data. The regular independent verification of data is crucial to ensure high-quality and incontestable data. The verification by a third party ensures that both actors involved in the contract have confidence in the progress presented and in the performance indicators used to measure progress and reward the achievement of results. As such, the credibility of the agreement is established. Ideally, the funder is not involved in the process of data collection, monitoring or evaluation. However, as the independent verification often has to rely on information that may not be available in the monitoring and evaluation system of the recipient, funders often carry out accompanying data collection activities.

Lastly, the contract defines the reward mechanisms. Within international debates, RBApps have mainly been linked to monetary reward mechanisms. However, this article argues that RBApps can also entail non-monetary reward mechanisms.

Generally, reward mechanisms are based on incentive schemes that link performance and the achievement of results. An incentive is therefore defined as ‘that which incites or encourages; a motive [and/or] a stimulus’.39 Performance and the achievement of results can be rewarded explicitly with a financial reward to an individual, a subgroup or the whole organisation (explicit incentive scheme).40 Rewards can also be distributed implicitly. For example, organisations can receive financial rewards because of the response of others to the performance measured. Alternatively, service providers who perform well or better than others can be rewarded for their good performance with more contracts in the future.41

Even when there is no implicit or explicit incentive scheme in place, performance and the achievement of results can be rewarded if the collected information is made public through individuals or organisations taking pride in their lead position or trying to avoid the label of being a failure. This ‘naming and shaming’ mechanism, which is linked to reputation, honour and pride, can also serve as an incentive scheme that affects and rewards performance.42

The reward mechanism of RBApps can hence include monetary or non-monetary rewards. Monetary reward mechanisms identify a ‘price per unit of progress’ at the beginning of the period that is to be evaluated. Non-monetary reward mechanisms link the achievement of results to, for example, honour and pride.

Case study: Imihigo – a traditional Rwandan concept as a RBApp

The achievement of results is the core concern of stakeholders in Rwanda. The Government of Rwanda (GoR) has a specific interest in using the country’s resources effectively as it legitimises itself by ensuring security, reducing poverty and strengthening development. As such, it has experimented with several innovative approaches that include a results orientation. Moreover, it has established its own DPA, Imihigo.

In 2000, the GoR began to reform its public sector with the implementation of the National Decentralization Policy (NDP). The policy is seen as an institutional arrangement for addressing key issues such as high levels of poverty and insufficient service delivery.43 Decentralisation is seen as a means to contribute towards the achievement of development goals by increasing participation levels and improving service delivery at the local level. As such, Rwanda’s sub-national governments, especially the districts, play a crucial role in achieving the country’s development goals. In line with the NDP, the GoR introduced concepts to strengthen public sector performance and the achievement of results at the sub-national level. The GoR drew on aspects of the country’s own history and culture as part of its efforts to reconstruct Rwanda and nurture a shared national identity.44 A set of ‘Home Grown Solutions’, including Imihigo, was introduced and translated into sustainable development programmes.45

Imihigo is a cultural practice in the ancient tradition of Rwanda in which an individual sets himself targets to be achieved within a specific period. These commitments needed to be ambitious and transformational and are not supposed to relate to routine activities. In 2006, the concept of Imihigo was translated into performance contracts at all levels of society and government, from the household to the village, cell, sector (Umurenge), district and province, and up to the national level. The performance contracts include targets that require commitments on implementation, personal responsibility, reciprocity of obligations and mutual respect between higher and lower ranks. Furthermore, the contracts emphasise high moral values, competition to achieve the best results and an evaluation of outcomes.46

As the sub-national level is crucial for achieving Rwanda’s development goals, the Imihigo contracts between the President of the Republic and the districts play a central role.47 Imihigo and the NDP are seen as complementary tools.48 Within the first Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy (EDPRS), from 2008 to 2012, the Imihigo contracts were identified as ‘the way in which national priorities would be driven through local governments, with all levels of government being held accountable to citizens’.49

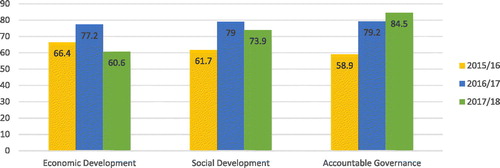

Since their introduction, Imihigo contracts have been derived from strategic policy documents across three pillars: economic development, social development and transformational governance.50 The President of the Republic and the districts’ mayors sign the contracts on an annual basis. presents the districts’ performance for each of the three pillars in the three latest Imihigo evaluations (2015/2016, 2016/2017 and 2017/2018).

Figure 2. Districts’ performance by pillar, 2015/2016–2017/2018 (%), Imihigo evaluation findings (2015/2016, 2016/2017 and 2017/2018).

Source: Data from National Institute of Statistics Rwanda (NISR), Imihigo Evaluation Report 2017/18 (2018, p. 19).

Actor constellation

The theoretical framework developed in the previous sections is applied to the Rwandan context to analyse the DPA, Imihigo. Research on Imihigo is limited – currently, only a few studies are available that provide further insights into the approach.51

Imihigo, as an RBApp, can be defined as a Domestic Performance Approach, as the concept is based on contracts between different Rwandan government entities: the national and sub-national governments, namely the President of the Republic and the districts. A number of actors significantly influence the formulation, implementation, monitoring and evaluation processes of the Imihigo contracts. These actors are crucial for determining the political economy within which the approach is embedded.

At the central level, five actors play an important role and influence the Imihigo contracts at different stages. The President’s Office and its Strategic Planning Unit coordinate the planning process for Imihigo contracts and provide strategic advice. In general, the Prime Minister’s Office is responsible for coordinating government activities and monitoring the implementation of government policies and programmes. Hence, it oversees all Imihigo activities on the national and sub-national levels. The Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MINECOFIN) – together with the Ministry of Local Government (MINALOC) and the Local Administrative Entities Development Agency (LODA) – is responsible for the disbursement of intergovernmental fiscal transfers to the district level. MINALOC has therefore the political responsibility for the implementation of the NDP and related processes. LODA is a government agency and is subordinated to MINALOC. It establishes the link between the national and sub-national governments by coordinating the entire development process at the local level. As such, both ministries play a crucial role not only during the planning and budgeting process, but also during the implementation of Imihigo contracts.

The Quality Assurance Team is composed of the four aforementioned institutions: the President’s Office, the Prime Minister’s Office, MINECOFIN and MINALOC/LODA. It ensures the quality of Imihigo contracts by controlling their alignment with national development objectives, such as the former Vision 2020, EDPRS 2 (2013–2018) and the only recently developed Vision 2050 and National Strategy for Transformation.52 The team also has a relevant role in monitoring and evaluation.

The fifth actor comprises line ministries, such as the Ministry of Education (MINEDUC). Line ministries decisively influence the Imihigo contracts through their sector policies and priorities, as these need to be well integrated within the Imihigo contracts.

At the district level, the main entities influencing the Imihigo contracts are the District Executive Committee, the District Council and the Joint Action Development Forum (JADF). Each District Executive Committee coordinates the planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation processes within its respective district.

Before Imihigo contracts are finalised, signed and set in place for the upcoming fiscal year, an extensive consultation process between the District Executive Committee, members of the JADF and the District Council takes place.53 The JADF has the legal mandate to promote co-operation between the district and the local population as well as other actors in development and social welfare. It hence serves as a platform to incorporate national and international non-governmental organisations, private sector entities, churches and civil society organisations.54 The District Council represents the population and each sector and ensures the incorporation of local priorities in Imihigo contracts. It adopts an advocacy role for the population and is responsible for approving the final contracts. The implementation of the targets is executed by the districts themselves as well as by the sub-district level, meaning the sectors, cells, villages and households.

Although the district and the sub-district levels are responsible for the implementation of Imihigo activities, they are highly dependent on fiscal transfers from the central government, local development partners and the contributions provided by their local populations. The successful implementation of Imihigo targets thus depends on the capacity of the districts to mobilise contributions from their local populations, their capacities with regard to the size of their budgets and staff, and their co-operation with partners.

The actor constellation reveals that the decision-making power with regard to the target setting, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of Imihigo contracts lies essentially with the central government. Through the concept of Imihigo, the central government exercises control over the local level to oversee and guarantee the implementation of national strategies and policies. This is in line with the mode of decentralisation pursued by the GoR: de-concentration. However, as the sub-national level is the entity responsible for the implementation of Imihigo targets, and thus plays a crucial role in achieving Rwanda’s development goals, the successful implementation of Imihigo targets often depends on how well all levels cooperate. Imihigo targets have to be aligned with national priorities, leaving only limited room for districts to incorporate local contexts and needs. As districts are highly dependent on fiscal transfers from the central government, development partners and contributions of the local population, issues of co-responsibilities and accountability for the districts’ performance arise.

Characteristics

The Imihigo concept complies with the characteristics identified in the theoretical framework: the concept is based on contracts that entail agreements about the results to be achieved, the monitoring, evaluation and verification processes to be followed, and the rewards to be distributed.

The contracts include targets to be achieved over the course of one fiscal year that aim at improving the lives of the local population. In the context of Imihigo contracts, the term ‘targets’ corresponds with ‘results’ in the theoretical framework.

Imihigo can be conceptualised as a tool to create progress and contribute towards achieving Rwanda’s development goals.55 The way targets are set with regard to their content is crucially influenced by the culture of Imihigo. The culture of Imihigo aims at setting ambitious and transformative targets that do not relate to routine activities. The inclusion of outcome and impact targets thus serves as an important criterion for targets to be included in the contracts. In this context, districts often named job creation or the stimulation of economic growth as relevant aspects.

However, the Imihigo contracts reveal that most targets focus on core activities at the output level, such as the construction of new schools and classrooms, that are repeatedly incorporated. So far, innovative and transformative targets have rarely been found and the focus is stronger on output than on outcome and impact targets. This could be reinforced because Imihigo targets are formulated for one fiscal year only, which impedes planning and implementation of mid- and long-term goals. Though mid- and long-term planning is possible through breaking down targets into annual phases, setting relevant indicators and estimating annual achievements proves to be challenging at the sub-national level. Therefore, districts often avoid multi-phase projects to reduce potential negative impacts of multi-year projects on annual performance.

The target-setting process contains top-down as well as bottom-up elements. Ideally, Imihigo contracts include a synthesis of both. However, in practice, top-down elements dominate target setting and challenge stakeholder participation.56

The first step of the target-setting process is the identification of national priorities by the GoR, followed by the communication of priorities to the sub-national government. The identification of local priorities comes afterwards, followed by the preparation of the districts’ Imihigo contracts and final approval by the GoR.57 As such, the Imihigo targets are aligned to national goals. Local priorities are incorporated at a later point in time and adjusted to the existing national framework.

Furthermore, special initiatives by line ministries influence the target-setting process. Often, these targets are part of the Imihigo contracts of the line ministries, which pass the responsibility for their implementation on to the districts. Districts are then obliged to include these targets into their Imihigo contracts and to implement them, regardless of local capacities, such as staff or budget, and local priorities.58

Nevertheless, the target setting theoretically also includes bottom-up elements to some extent, through the inclusion of needs and priorities of the local population. At the household, village, cell and sector levels, the local population is invited to develop suggestions and name priorities based on local needs, together with the respective administrative staff. These needs and priorities are then analysed and harmonised at the next administrative level. Finally, the district develops a draft Imihigo contract, which is assessed by the Quality Assurance Team with respect to its alignment with national goals and policies and finalised with the signature of the President of the Republic.59

The bottom-up approach for selecting new activities has several advantages: different capacities and needs are taken into account, annual feedback on priorities is received and trust between the population and the district authorities is created. However, participation mechanisms guaranteeing the inclusion of the local population in planning and decision-making processes are vague or, often, missing. The influence of the local population on the target-setting process and downward accountability hence remains limited.

The Imihigo contracts include regular monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to examine the districts’ performance. The concept thus leads to increased transparency and accountability of government activities, which is supported by the fact that the contracts are accessible to the public in Kinyarwanda and English.

For each target, there are specific performance indicators to collect data, and monitor and evaluate the progress made. An assessment of the progress is done after the first six months of each fiscal year. The data for the progress reports is collected by the sectors, which transfer the data to their respective district planner.

This method of data collection is not unproblematic, as the data provided sometimes may not be accurate. Occasionally, the high levels of pressure to perform can encourage individuals to focus only on supportive data or even to falsify data. Moreover, there is a bias at the district level regarding data collection, as district officials who are involved in the implementation of Imihigo targets are often also responsible for monitoring the progress and compiling progress reports. Since only some of the data is verified by the districts due to low and limited statistical capacities, the quality of the data thus proves to be challenging to uphold and is not sufficient in some areas.

At the end of each fiscal year, a verification of the progress made is presented. In the District Imihigo Evaluations, the results presented in the progress reports are verified and the districts are ranked based on their overall performance as well as on their performance in the three priority areas of the GoR, as presented in .60

Before the fiscal year 2013/2014, the GoR conducted the District Imihigo Evaluation itself. The personal and professional relations between government officials at the national and sub-national levels limited the transparency and independence of the verification process and its results and created a bias. Beginning in 2013/2014, the GoR commissioned the Institute of Policy Analysis and Research (IPAR) Rwanda as an external evaluator to ensure independent verification of the results. Moreover, the evaluation approach was reformed to improve the methodology, include an outcome dimension and ensure the objectivity of the process.

The methods used for data collection were adjusted: data collection was based on a combination of methods including desk research, audits, perception and satisfaction surveys in the form of Citizen Report Cards, interviews with key experts and field visits.61 The performance indicators that were used focused not ony on the planned outputs achieved but also on the extent to which the districts’ Imihigo targets were aligned with national strategies and policies. Furthermore, the evaluation also aimed at addressing the extent to which the outputs achieved have the potential for transformation as well as whether they are innovative enough to achieve meaningful outcomes.62

Beginning in 2017/2018, however, the GoR commissioned the National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) to further adjust the methodology and conduct the evaluation.63 While commissioning a government institution again might support strengthening statistical capacities, independence and objectivity need to be questioned once more.

Irrespective of the entity conducting the evaluation, one additional challenge relates to the difficulty of ranking districts and comparing their performances. The local contexts and circumstances vary significantly in Rwanda. Whereas some districts are rather rural and face high poverty rates, other districts are urban and have the possibility of collecting more of their own revenues, and thus increase their available district budgets to implement Imihigo targets. As the starting points and contexts for districts differ, the question arises as to whether – and to what extent – the districts’ performance can actually be compared, ranked and rewarded.

Lastly, the Imihigo contracts entail a non-monetary reward mechanism based on honour and pride, which reinforces and strengthens the focus on performance and results at the sub-national level. If districts rank among the first three in the annual District Imihigo Evaluation, they receive a certificate and trophy and get the chance to shake hands with the President of the Republic. This is reported nationwide and provides honour and pride to the citizens within the respective district.

Some informal reward mechanisms are also in place. At the district level, good performance by a district can lead to higher levels of trust of the central government in the districts’ capacities, and can thus lead to a better bargaining position in the budget allocation negotiations for the Imihigo contracts of the following fiscal year. In addition, some districts also evaluate and rank the performance of their sectors and reward the first three. Sectors then receive, for example, financial rewards as a top-up for their budget for the next fiscal year, or trophies and certificates from the District Mayor in a public ceremony. In some districts, reward mechanisms are also in place to create competition among schools and teachers. One school that was visited received a new car as a reward for having the best school performance in the district over a couple of years. In another district, the best-ranked teachers were given new laptops.

The reward mechanisms, formal or informal, reinforce and strengthen the focus on performance, as they serve as motivation for district officials to work hard and do their best to achieve the targets set in Imihigo contracts. However, the existence of different types of rewards is not unproblematic: the variety of informal monetary and non-monetary rewards reduces the transparency of the reward mechanism in general, thereby creating opportunities for corruption. Reduced transparency also limits the effectiveness of the reward mechanisms, as, for example, all individuals competing might not fully know the conditions for reward disbursements.

Additionally, the reward mechanisms can also create adverse incentives. The rewards promised upon the successful implementation of Imihigo targets can reinforce the ‘time-shortening disease’, whereby district officials focus on short- instead of medium- and long-term targets. Furthermore, chances are high that officials only focus on targets that are specifically included in the Imihigo contracts. Targets which are not included in the contracts run the risk of receiving lower priority or even being neglected. In addition, the promise of rewards can increase the risk of data falsification. At the sub-district levels, false data has been provided to the district levels in order for the sub-district in question to receive better rankings in the sector Imihigo evaluations and reap the financial rewards.

Against this background, the existing non-monetary incentives are believed to be sufficient to serve as formal rewards by districts to create incentives to improve performance and achieve the agreed upon targets. A hypothetical linkage of the District Imihigo Evaluation with financial rewards is being regarded with caution, as some district officials fear the risk of intensifying adverse incentives. Moreover, financial rewards might compromise the effectiveness of the non-financial reward mechanism and possibly overload the incentive system.

Discussion, conclusions and recommendations

Based on the principles of NPM, the concept of RBApps has gained increasing levels of attention in recent years. There is a growing interest in the application of RBApps in all regions and across different policy fields, including development co-operation. Several development partners have developed and piloted RBApps to trigger innovation and push for reforms in developing countries. RBApps are thereby used as an instrument to account for results and show that development co-operation is ‘value for money’.

However, these debates often neglect the domestic perspective. So far, discussions on DPAs and RBApps have been poorly linked. Yet a conceptual framework encompassing both approaches exists. Considering the lessons learnt from past NPM reforms and taking into account movements towards a post-NPM approach, the extension of the concept towards the inclusion of the DPA provides possibilities for experimentation and discovery.

These possibilities and the need to better align the donors’ and partner countries’ efforts support the argument for using DPAs as an entry point for development co-operation. Rwanda’s DPA, Imihigo, entails an extensive performance measurement system that aims at fostering the achievement of Rwanda’s development goals. Using the country system, parallel structures could be avoided, harmonisation facilitated and cost-effectiveness increased. In addition, transaction costs for development aid could be reduced, as fewer reporting processes would be needed.64 Additional advantages could be an improved alignment of development partners with Rwanda’s policies, and improved domestic accountability as well as a strengthened country system, including a more stable macroeconomic framework and higher efficiency levels in public expenditure. Finally, yet importantly, using Imihigo could increase Rwandan ownership, as development partners would directly support the country’s policies, which are broken down into annual performance contracts. As Imihigo is well respected at all government levels as well as by the local population, an increased level of ownership of – and identification with – local development processes by the Rwandan population could furthermore help to ensure the sustainability of development co-operation and the investments made.

However, the requirements for a DPA to be a suitable entry point for development co-operation are high, as all processes (for example, procurement, monitoring and evaluation, data management) are managed by country systems. Looking at the Rwandan example, various challenges, of which some are common within the context of NPM reforms, remain. The targets set in Imihigo and the performance indicators used are mainly output oriented. As development partners face increasing pressure to present the impact and sustainability of aid delivered, this output orientation constitutes an issue with regard to the use of Imihigo for development co-operation. Focussing merely on outputs might encourage adverse incentives by contributing to – and reinforcing the focus on – short-term instead of medium- and long-term goals. Only the inclusion of outcome and impact targets and indicators in the contracts will ensure that medium- and long-term goals are achieved. An additional challenge is the quality and quantity of data.

In the Rwandan case, the data provided may sometimes not be accurate, as only some data is verified by the districts due to low and limited statistical capacities of the districts. The high levels of pressure to perform may encourage individuals to focus only on supportive data, or even to falsify data. The quality of data thus proves to be challenging to uphold and is not sufficient in several areas. This constitutes an issue with regard to using Imihigo for applying RBA and/or RBF. High data quality levels and a strong and independent monitoring, evaluation and verification system are crucial for development partners, since the achievement of results is directly linked with monetary rewards.

A third challenge is that development partners often face a lack of understanding of the DPAs themselves. In relation to Imihigo, uncertainty exists, for example in terms of what the concept means and what it is composed of. This uncertainty translates into questions regarding the purpose of Imihigo. Imihigo cannot be regarded only as a general management tool but must be seen also as a policy management tool. As a policy management tool, Imihigo ensures the implementation of national policies at the district level, by introducing top-down accountability and control mechanisms between the national and sub-national levels. In that sense, Imihigo can be regarded as a tool for the country’s high commitment to development and its ‘developmental’ approach.65 Conceptually, Rwanda might be seen as being a special case for successful socio-economic development in sub-Saharan Africa. However, scholars and several actors in the governance field have criticized the quality of democracy in Rwanda and argue that Imihigo might be used as a tool to strengthen the control system of an autocratic regime.66 Such an argument might disincentivize engagement by development partners.

Lastly, it also needs to be debated whether successes of Imihigo might be overstated. Imihigo strengthened a performance culture and the achievement of results, and since its introduction, Rwanda has made remarkable progress on a wide range of development indicators.67 As presented in the section ‘Characteristics’ of the ‘Case study: Imihigo – a traditional Rwandan concept as a RBApp’, though, district officials may have falsified data and inflated results.

It thus does not come as a surprise that the quality of country systems serves as a key determinant for their use by development partners. The perceived trustworthiness of the partners’ country systems therefore plays a central role in the decision of development partners regarding what system to use to manage aid.68 Partner countries are hence often asked to strengthen their country systems, in particular their public financial management systems as well as the capacities of their civil servants.69 The weaknesses of the partners’ country systems, missing capacities, a lack of trust and the need for external verification might sometimes justify the decision of development partners to bypass them to avoid reputational and fiduciary risks on their side.70 In this context, new performance measurement systems with new performance indicators for RBA and RBF may be unavoidable. This might not necessarily be a disadvantage, as the newly introduced performance indicators could prove useful for the partner country.

Nevertheless, using these country systems in the meantime, despite potential flaws, helps to strengthen them in the medium and long term: ‘donors can help build capacity and trust by using country systems to the fullest extent possible, while accepting and managing the risks involved’.71 In the case of Imihigo, this means, for example, that development partners can strengthen capacities and trust by using the country system through a conceptual engagement.72 In order to effectively manage risks and strengthen Rwanda’s capacities at the national and subnational level, analytical tools are crucial. In this regard, the Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability results for the subnational level (published in 2017), as well as the results from the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation Monitoring Round, are important foundations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stephan Klingebiel

Stephan Klingebiel is Head of the Programme Inter- and Transnational Cooperation with the Global South at the German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) and a regular guest professor at Stanford University. His research focuses on political economy of aid, aid and development effectiveness, political economy and governance issues in sub-Saharan Africa, and crisis prevention and conflict management.

Victoria Gonsior

Victoria Gonsior is a researcher within the Programme Inter- and Transnational Cooperation with the Global South at the German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE). She completed the Postgraduate Training Programme there and her research concentrates on development effectiveness, the political economy of development policy, global cooperation for sustainable development and public finance.

Franziska Jakobs

Franziska Jakobs is an advisor for governance. She completed the Postgraduate Training Programme at the German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) and worked as a researcher there. Her work and research mainly focus on good governance issues, in particular decentralisation, public service delivery and local governance.

Miriam Nikitka

Miriam Nikitka is a consultant in the Monitoring & Evaluation Unit at GFA Consulting Group. She completed the Postgraduate Training Programme at the German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE). Her research concentrates on results-based approaches, results-oriented monitoring, strategic evaluations and evaluation management.

Notes

1 Goddard and Mkasiwa, “New Public Management,” 334.

2 Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff, “Public Sector Management Reform,” 235.

3 Different terms are used as a generic term for this new approach: performance-based aid, cash on delivery, results-based aid, results-based funding, payment by results, etc. In this study, the term ‘RBApp’ is used to describe all results-related approaches.

4 Keijzer and Janus. Linking Results-Based Aid, 3; Klingebiel, Results-Based Aid (RBA), 3.

5 Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff, “Public Sector Management Reform,” 235.

6 See eg World Bank, Programme-for-Results.

7 GoR, Rwanda Poverty Profile Report.

8 The results presented in the subsequent sections were obtained during a research study that was conducted between November 2014 and May 2015. The study also included a three-month field trip to Rwanda from mid-February to the end of April 2015. For further information on the case selection and study design refer to Klingebiel et al., Public Sector Performance, 4–10.

9 Economic and Social Council, Definition of Basic Concepts, 7; OECD/DAC, EIP Country Dialogues, 14; Ayeni, Public Sector Reform, 1.

10 UNDP, Public Administration Reform, 2.

11 Bach and Bordogna, “Varieties of New Public Management.”

12 Mackay, Public Sector Performance.

13 Saltmarshe, Ireland and McGregor, “Performance Framework.”

14 Scott and Thynne, Public Sector Reform.

15 Smoke, “Decentralisation in Africa”; McCourt and Minogue, Internationalization of Public Management.

16 Goddard and Mkasiwa, “New Public Management,” 363.

17 Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff, “Public Sector Management Reform.”

18 See eg Morse, Outcome-Based Payment Schemes.

19 Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff, “Public Sector Management Reform”; Shah and Andrews, Handbook on Public Sector Performance Reviews, 224.

20 Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff, “Public Sector Management Reform.”

21 Goddard and Mkasiwa, “New Public Management,” 363.

22 Holzapfel, Boosting or Hindering Aid Effectiveness, 19.

23 Hayman, “From Rome to Accra,” 593; Hyden, “After the Paris Declaration.”

24 Guijt, “Playing the Rules of the Game,” 193.

25 Paul, “Performance-Based Aid.”

26 Birdsall et al., Cash on Delivery, 21.

27 For further information on the different types of actor constellations and a graphical representation refer to Klingebiel et al., Public Sector Performance, 21.

28 Klingebiel and Janus, “Results-Based Aid,” 4–6.

29 Birdsall et al., Cash on Delivery, 3; Klingebiel, Results-Based Aid (RBA), 10.

30 Keijzer and Janus, Linking Results-Based Aid, 3–5; Paul, “Performance-Based Aid,” 315.

31 See eg Paul, “Performance-Based Aid.”

32 Pearson, Johnson and Allison, Review of Major Results Based Aid, 50.

33 Country systems are defined ‘as national arrangements and procedures for Public Financial Management [PFM], procurement, audit, monitoring and evaluation as well as social and environmental procedures’. See OECD/DAC, EIP Country Dialogues, 1.

34 OECD/DAC, Busan Partnership, 5.

35 World Bank, “Expanding the Use of Country Systems,” 2–4.

36 OECD, Evaluation and Aid Effectiveness, 33.

37 Keijzer and Janus, Linking Results-Based Aid.

38 Birdsall et al., Cash on Delivery, 3.

39 Ostrom et al., Aid, Incentives, and Sustainability, 6.

40 Wilson and Propper, Use and Usefulness of Performance Measures, 3.

41 Burgess, Propper and Wilson, Does Performance Monitoring Work?, 5.

42 Wilson and Propper, Use and Usefulness of Performance Measures, 4.

43 Prior to 1994, decentralisation efforts failed, as the political, financial and administrative requirements were not met. The centralised structure led to weak service delivery as well as social unrest. See Andrews, Limits of Institutional Reform, 163; Klingebiel et al., Public Sector Performance, 44.

44 ADB, Performance Contracts and Social Service Delivery, 7.

45 The GoR presents Imihigo as ‘home-grown solutions’ that is based on traditional practices and cultural beliefs. Within this article, we do not examine the history of the concept or to what extent it can be traced back. Besides Imihigo, these ‘home-grown solutions’ were Ubudehe (custom of collective action for community development), Umugoroba w’Ababyeyi (‘parents’ evening forum), and Umuganda (tradition of voluntary work in the common interest). See MIGEPROF, Umugoroba w’Ababyeyi Strategy; RGB, Sectoral Decentralization in Rwanda; RGB, Assessment of the Impact; Hasselskog, “Rwandan ‘Home Grown Initiatives’”; Hasselskog and Schierenbeck, “National Policy in Local Practice.”

46 Rwiyereka, “Using Rwandan Traditions,” 688.

47 The performance contracts (Imihigos) exist between different government entities; see NISR, Imihigo Evaluation Report. Hereafter, the term ‘Imihigo’ refers to the annual performance contracts between the district mayors and the President of the Republic.

48 NISR, Imihigo Evaluation Report, 3.

49 Andrews, Limits of Institutional Reform, 167.

50 The Imihigo evaluation report 2017/2018 provides further insights on each of the three pillars and their linkage to the NDP. See NISR, Imihigo Evaluation Report, 3.

51 Chemouni, “Explaining the Design of the Rwandan Decentralization”; Scher, The Promise of Imihigo; Hasselskog, “Rwandan ‘Home Grown Initiatives’”; Rwiyereka, “Using Rwandan Traditions”; Versailles, Rwanda: Performance Contracts; Beschel et al., Improving Public Sector Performance; Ndahiro, Explaining Imihigo Performance.

52 NISR, Imihigo Evaluation Report, 2.

53 Scher, The Promise of Imihigo, 5–6.

54 Klingebiel and Mahn, Public Financial Management, 22.

55 NISR, Imihigo Evaluation Report, 3.

56 Beschel et al., Improving Public Sector Performance, 56.

57 RGB, Assessment of the Impact, 6; GoR, Imihigo Evaluation, 89.

58 One example for a special initiative is the one adopted by the Ministry of Education in fiscal year 2012/2013, which required all districts to include the target ‘construct one teacher hostel per sector’ in their Imihigo contracts. For further information on the special initiative, refer to Klingebiel et al., Public Sector Performance, 52.

59 Besides the Imihigo contract between the district and the President of the Republic, every level has its own Imihigo contracts: that is, a sector (Umurenge) signs a performance contract with its district. Ideally, all contracts are based on one another to ensure there exists a division of labour for achieving the targets on each level, and, ideally, each actor is aware of his role in the development process and is accountable to the next higher decentralised level. See RGB, Assessment of the Impact, 86.

60 NISR, Imihigo Evaluation Report, 20.

61 GoR, Imihigo Evaluation, 10–12.

62 Ibid., 12.

63 NISR, Imihigo Evaluation Report, ix.

64 Klingebiel, Results-Based Aid (RBA).

65 Keijzer et al., Seeking Balanced Ownership, 91.

66 See eg Purdeková, “Even if I Am Not Here.”

67 Beschel et al., Improving Public Sector Performance, 55.

68 Knack, When Do Donors Trust, 5.

69 Booth, “Aid, Institutions and Governance,” 12.

70 Knack, When Do Donors Trust, 5.

71 OECD/DAC, Aid Effectiveness: A Progress Report, 27.

72 For a more detailed discussion of using the country system Imihigo and the conceptual engagement, refer to Klingebiel et al., Public Sector Performance, 77–83.

Bibliography

- ADB (African Development Bank). Performance Contracts and Social Service Delivery – Lessons from Rwanda. Policy Brief. Kigali, Rwanda: African Development Bank, 2012.

- Andrews, M. The Limits of Institutional Reform in Development: Changing Rules for Realistic Solutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Ayeni, V. Public Sector Reform in Developing Countries: A Handbook of Commonwealth Experiences. London: Commonwealth Secretariat, 2002.

- Bach, S., and L. Bordogna. “Varieties of New Public Management or Alternative Models? The Reform of Public Service Employment Relations in Industrialized Democracies.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 22 (2011): 2281–2294. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2011.584391

- Beschel, R., B. Cameron, J. Kunicova, and B. Myers. Improving Public Sector Performance through Innovation and Inter-Agency Coordination. Global Report Public Sector Performance. Washington, DC: World Bank Group, 2018.

- Birdsall, N., W. D. Savedoff, A. Mahgoub and K. Vyborny. Cash on Delivery: A New Approach to Foreign Aid. Washington, DC: Centre for Global Development, 2010.

- Booth, D. “Aid, Institutions and Governance: What Have We Learned?” Development Policy Review 29, no. 1 (2011): 5–26.

- Brinkerhoff, D. W., and J. M. Brinkerhoff. “Public Sector Management Reform in Developing Countries: Perspectives Beyond NPM Orthodoxy.” Public Administration and Development 35, no. 4 (2015): 222–237. doi: 10.1002/pad.1739

- Burgess, S., Propper, C., and Wilson, D. Does Performance Monitoring Work? A Review of the Evidence from the UK Public Sector, Excluding Health Care. Bristol: University of Bristol, Centre for Market and Public Organisation, 2002.

- Chemouni, B. “Explaining the Design of the Rwandan Decentralization: Elite Vulnerability and the Territorial Repartition of Power.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 8, no. 2 (2014): 246–262. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2014.891800

- Economic and Social Council. Definition of Basic Concepts and Terminologies in Governance and Public Administration. New York: United Nations Economic and Social Council, 2006.

- Goddard, A., and T. A. Mkasiwa. “New Public Management and Budgeting Practices in Tanzanian Central Government: ‘Struggling for Conformance.’” Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 6, no. 4 (2016): 340–371. doi: 10.1108/JAEE-03-2014-0018

- GoR (Government of Rwanda). Imihigo Evaluation FY 2013/14. Final Report. Kigali, Rwanda: Government of Rwanda, 2014.

- GoR (Government of Rwanda). Rwanda Poverty Profile Report 2013/2014. Results of Integrated Household Living Conditions Survey (EICV). Kigali, Rwanda: Government of Rwanda, 2015.

- Guijt, I. “Playing the Rules of the Game and Other Strategies.” In The Politics of Evidence and Results in International Development: Playing the Game to Change the Rules? edited by R. Eyben, I. Guijt, C. Roche, and C. Shutt, 193–210. Rugby: Practical Action Publishing, 2015.

- Hasselskog, M. “Rwandan ‘Home Grown Initiatives’: Illustrating Inherent Contradictions of the Democratic Developmental State.” Development Policy Review 36, no. 3 (2017): 309–328. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12217.

- Hasselskog, M., and I. Schierenbeck. “National Policy in Local Practice: The Case of Rwanda.” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 5 (2015): 950–966. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1030386

- Hayman, R. “From Rome to Accra via Kigali: ‘Aid Effectiveness’ in Rwanda.” Development Policy Review 27 (2009): 581–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7679.2009.00460.x

- Holzapfel, S. Boosting or Hindering Aid Effectiveness? An Assessment of Systems for Measuring Agency Results. Bonn: German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, 2014.

- Hyden, G. “After the Paris Declaration: Taking on the Issue of Power.” Development Policy Review 26 (2008): 259–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7679.2008.00410.x

- Keijzer, N., and H. Janus. Linking Results-Based Aid and Capacity Development Support. Conceptual and Practical Challenges. Bonn: German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, 2014.

- Keijzer, Niels, Stephan Klingebiel, Charlotte Örnemark, and Fabian Scholtes. Seeking Balanced Ownership in Changing Development Cooperation Relationships. Stockholm, Sweden: Expert Group for Aid Studies (EBA), 2018.

- Klingebiel, S. Results-Based Aid (RBA): New Aid Approaches, Limitations and the Application to Promote Good Governance. Bonn: German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, 2012.

- Klingebiel, S., V. Gonsior, F. Jakobs, and M. Nikitka. Public Sector Performance and Development Cooperation in Rwanda – Results-Based Approaches. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Klingebiel, S., and H. Janus. “Results-Based Aid: Potential and Limits of an Innovative Modality in Development Cooperation.” International Development Policy 5, no. 2 (2014). http://journals.openedition.org/poldev/1746

- Klingebiel, S., and T. Mahn. Public Financial Management at the Sub-National Level in Sub-Saharan Africa. Bonn: German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, 2014.

- Knack, S. When Do Donors Trust Recipient Country Systems? Washington DC: World Bank Group, 2012.

- Mackay, K. Public Sector Performance – The Critical Role of Evaluation. Washington DC: World Bank Group, 1998.

- McCourt, W., and M. Minogue. The Internationalization of Public Management: Reinventing the Third World State. New Horizons for Public Policy. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2001.

- MIGEPROF (Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion). Umugoroba w’Ababyeyi Strategy. Kigali, Rwanda: MIGEPROF, 2014.

- Morse, A. Outcome-Based Payment Schemes: Government’s Use of Payment by Results. London: National Audit Office, 2015.

- Ndahiro, Innocent. Explaining Imihigo Performance in Gicumbi District, Rwanda: The Role of Citizen Participation and Accountability (2009–2014). The Hague, the Netherlands: International Institute of Social Studies, 2015.

- NISR (National Institute of Statistics Rwanda). Imihigo Evaluation Report 2017/2018. Kigali, Rwanda: National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, 2018.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Evaluation and Aid Effectiveness No. 6 – Glossary of Key Terms in Evaluation and Results-Based Management. Paris: OECD, 2002.

- OECD/DAC (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development/Development Assistance Committee). Aid Effectiveness: A Progress Report on Implementing the Paris Declaration. Better Aid Series. Paris: OECD, 2009.

- OECD/DAC (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development/Development Assistance Committee). The Busan Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation. Paris: OECD, 2011.

- OECD/DAC (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development/Development Assistance Committee). EIP Country Dialogues on Using and Strengthening Local Systems. Paris: OECD, 2014.

- Ostrom, E., Gibson, C., Shivakumar, S., and Andersson, K. 2001. Aid, Incentives, and Sustainability. An Institutional Analysis of Development Cooperation. Main Report: Sida Studies in Evaluation 02/01. Stockholm: Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

- Paul, E. “Performance-Based Aid: Why It Will Probably Not Meet its Promises.” Development Policy Review 33 (2015): 313–323. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12115.

- Pearson, M., Johnson, M., and Ellison, R. Review of Major Results Based Aid (RBA) and Results Based Financing (RBF) Schemes. Final Report. London: DfID Human Development Resource Centre, 2010.

- Purdeková A. “Even if I Am Not Here, There Are So Many Eyes: Surveillance and State Reach in Rwanda.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 49, no. 3 (2011): 475–497. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X11000292

- RGB (Rwandan Governance Board). The Assessment of the Impact of Home Grown Initiatives. Kigali, Rwanda: Rwandan Governance Board, 2014.

- RGB (Rwandan Governance Board). Sectoral Decentralization in Rwanda. Kigali, Rwanda: Rwandan Governance Board, 2012.

- Rwiyereka, A. K. “Using Rwandan Traditions to Strengthen Programme and Policy Implementation.” Development in Practice 24 (2014): 686–692. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2014.936366

- Saltmarshe, D., M. Ireland, and J. A. McGregor. “The Performance Framework: A Systems Approach to Understanding Performance Management.” Public Administration and Development 23 (2003): 445–456. doi: 10.1002/pad.292.

- Scher, D. The Promise of Imihigo: Decentralized Service Delivery in Rwanda, 2006–2010. Innovations for Successful Societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 2010.

- Scott, I., and I. Thynne. Public Sector Reform: Critical Issues and Perspectives. Hong Kong: AJPA, 1994.

- Shah, A., and M. Andrews. Handbook on Public Sector Performance Reviews. Bringing Civility in Governance. Washington DC: World Bank, 2003.

- Smoke, P. “Decentralisation in Africa: Goals, Dimensions, Myths and Challenges.” Public Administration and Development 23 (2003): 7–16. doi: 10.1002/pad.255

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). Public Administration Reform. Practice Note. New York: UNDP, 2003.

- Versailles, B. Rwanda: Performance Contracts (Imihigo). ODI Budget Strengthening Initiative. London: Overseas Development Institute, 2012.

- Wilson, D., and C. Propper. The Use and Usefulness of Performance Measures in the Public Sector. Bristol: Department of Economics, University of Bristol, 2003.

- World Bank. Expanding the Use of Country Systems in Bank-Supported Operations: Issues and Proposals (English). Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/856881468780905107/Expanding-the-use-of-country-systems-in-Bank-supported-operations-issues-and-proposals

- World Bank. Programme-for-Results Two-Year Review. Washington DC: World Bank Group, 2013.