Abstract

Does a proliferation of activist or advocacy non-governmental organisations (NGOs) indicate greater power to pressure multinationals to behave responsibly? This paper answers this question by exploring how multinational oil companies deploy corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a tool to shape the nature of resistance to their disruptive impacts on extractive contexts in Africa. It focusses in particular on their role in building NGO networks and uses evidence from the activities of Chevron in Nigeria’s Niger Delta to show how these networks have become new sites through which multinational corporations exercise hegemonic power over the resistance landscape in the region. It concludes that NGO density – in spite of its appearance of facilitating greater participation – has little impact on the power dynamics in extractive contexts, on the logics of extraction and on the medium-term stability of the sector. What it does achieve is the construction of a gentrified ‘resistance and engagement’ landscape that is bureaucratised and middle-class driven, that excludes key actors and that is inevitably sympathetic to the oil industry.

Introduction

Resistance to the disruptive impacts of multinational capital is evident in volatile extractive contexts across the world (Alao Citation1999; Cilliers and Dietrich Citation2000). From armed insurrections in Nigeria’s Niger Delta (Watts Citation2008; Obi Citation2009) and the DRC’s Northern Katanga (de Koning Citation2013), to social movements in Latin America (Furnaro Citation2019), and to everyday resistance across many other contexts (Johansson and Vinthagen Citation2016), it is apparent that communities are exercising counterhegemonic agency and trying hard to shape the debates about how natural resources should be managed, and how the accompanying gains and pains should be distributed. While these patterns of resistance suggest deepening consensus against the neoliberal logics of resource extraction and ownership, they sometimes hide the growing ability of multinational corporations to adapt to these challenges to their power and, perhaps more crucially, their ability to conceal this adaptive power in profoundly effective ways.

This paper explores one such adaptive strategy of multinational corporations and the interesting ways in which the politics of corporate social responsibility (CSR) is implicated in this process. In particular, it examines the role that multinational companies play in building non-governmental organisation (NGO) coalitions that are ostensibly developed to challenge these very same firms or, at the very least, to confront the adverse implications of extraction. Drawing insights from the Nigerian oil sector, the paper teases out the subtle construction of hegemonic relations between multinationals and local NGOs and the implications this has for the ability of local communities to challenge the contradictions of neoliberal extraction.

The main argument made in this paper is that whereas the emergence of dense NGO networks would suggest a coalescing of local resistance against the disruptive impacts of multinationals in extractive sectors, the reality is often more nuanced, such that the subtle influences that are co-applied between these actors can often be lost to observers. In essence, multinationals are appropriating ‘dissidence’ and ‘resistance’ in meaningful ways, by aiding the creation of NGO networks. NGO networks are thus emerging as new sites through which multinational corporations exercise power over a postcolonial state in retreat. To make this argument, the paper draws on case study data generated from Nigeria’s oil delta. Oil is a particularly useful entry point into understanding the politics of CSR in the extractive sector for a number of reasons.

First, oil represents arguably the most profitable global natural resource in Africa. The Energy Intelligence Administration forecasted, for instance, that by 2020 total daily global oil production would be around 115 million barrels (Arezki and Gylfason Citation2013). At the USD 70 price in July 2018, this amounted to about eight billion US dollars’ worth of oil every day. Africa’s biggest oil producers – Nigeria, Angola, Algeria, Egypt and Libya – contribute a daily production of about nine million barrels with a value of around 630 million USD. In 2020, Africa contributed around 15% of global oil production, thus retaining its place as a major source of this globally relevant resource. The constant geostrategic instabilities in the Middle East amplify the relevance of Africa’s oil resources, thereby helping to draw disproportionate attention from multinational capital.

Second, oil – as well as other resources like diamonds – has been implicated in multiple eruptions of violence over the last three decades, costing lives in the thousands (Le Billon Citation2010). The Niger Delta region of Nigeria is a good example of the violent impact that oil extraction can have on postcolonial societies. Decades of oil extraction have, according to Iwilade (Citation2014), socialised a whole generation of young people into violent resistance to authority. This violent sociality has not occurred in a vacuum but is directly connected to the nature of the exercise of state power and the distortions caused by oil extraction in the region. Watts (Citation2003, 5089) puts it quite poignantly when he notes that oil’s history in Nigeria is that of an ‘uninterrupted chronicle of naked aggression, genocide and violent law of the corporate frontier’. This bleak discussion of the impact of oil on social order in Nigeria’s Niger Delta is supported by many other studies, both academic and popular, which point to the role of the oil industry in the creation of a violent universe that has drawn in youth gangs, a repressive state and militarised society (Nwajiaku-Dahou Citation2012). This violence has had major implications for the global energy market, as it threatens supply security. It has also been used as a pretext for the militarisation of the Gulf of Guinea, with all its implications for geopolitical stability (Onuoha Citation2010). Over the last two decades, in particular the years between 2003 and 2007, there have been tens of cases of kidnap of oil sector workers, multiple bombings of oil installations and state property and attacks on the Nigerian armed forces (Oriola, Haggerty, and Knight Citation2013). Until the Boko Haram crisis erupted in 2009, the Niger Delta was the single most potent challenge to the authority of the Nigerian state since its civil war between 1967 and 1970.

Third, in the light of this global relevance and susceptibility of oil to violent conflict, there has been a dense presence of social movements and NGOs, which are simultaneously contesting and facilitating the dominant neoliberal logic of oil extraction in the Delta. Watts (Citation2004, 198) describes this as multinationals and social movements working ‘with and against one another in complex and contradictory ways’. To be sure, the density of the Niger Delta’s advocacy map must be seen within the context of the global popularity of NGOs as vehicles for social action as well as local histories of oppression that forced underserved groups into the margins of state politics (Hilhorst Citation2003; Obi Citation2009). In the context of a globalisation movement that sought to shift the locus of power to privatised social forces, NGOs were both products and agents of neoliberal capital (Mittelman Citation2011).

NGOs are also increasingly driven by the language of constructive engagement that encourages a gradualist and non-confrontational approach to politics (Brass Citation2012). This inevitably makes it possible for them to work collaboratively with the very same multinationals that they purportedly challenge. For instance, a detailed analysis of the relationship between Shell Petroleum and Living Earth International, an NGO based in Port Harcourt, by Heap (Citation2000), highlights the ways in which well-meaning NGOs can be inadvertently incorporated into the CSR agenda of oil multinationals. Similar questions have been raised about such collaborative stakeholder ‘partnerships’ between NGOs and corporations in other places including Finland’s lumber industry (Lawrence Citation2007), business parks in Brazil and the Philippines (Gold Citation2004), and in South Africa (Mueller-Hirth Citation2009). As will be shown later, this collaborative relationship between oil multinationals and NGOs in the Niger Delta is one of the key drivers of the network-building trends in the region.

The paper is structured around five sections, the first of which is this introduction. In the next section, I ask what conditions currently prevail in Africa’s extractive sectors and how CSR is being deployed to respond to it. The section that follows then explores the politics of CSR in the light of Gramsci’s hegemonic theory of civil society. Here, theoretical entry points into hegemonic network-building are explored in order to understand how the diffusion of neoliberal values is being accomplished through CSR projects. I ask what are the conditions in which hegemonic forces can shape the nature of resistance to their activities and in which they can effectively reconstitute the logic of legitimacy in ways that blunt resistance? The point here is to use Gramsci as a framework for a background discussion into the impacts of neoliberal logics on labour practices, livelihoods and social stability and how, combined with state weakness, these have generated specific types of vibrant advocacies and sometimes violent social resistance. The fourth section draws on research conducted on the current CSR practices of one of Nigeria’s oil majors – Chevron. In particular, it examines the shift from individual memoranda of understanding (MoU) which Chevron used to sign with host communities to what it now calls global MoUs. These GMoUs have expanded the actors involved in the negotiations and have, in particular, created a space in which various parts of the Delta civil society now circulate. This space is conceptualised as a site through which and within which oil capital is able to exert hegemonic control over the social space, allowing it to effectively re-invent the very nature of dissidence and resistance. The concluding section brings the arguments together and highlights how these can help us think more critically about the implications of NGO homogenisation in Africa’s extractive sector.

Doing good in marketplaces? Extraction, violence and the politics of CSR

The growing investment of multinational corporations in CSR suggests a new wave of corporate conscience in which calls like Bill Gates’ 2008 suggestion of a ‘creative capitalism’ are being heeded. Speaking at the World Economic Forum at Davos, Gates called for companies to align their self-interest with the public good and thus gain more legitimacy (O’Laughlin Citation2008). If this is the case, then CSR can be seen as a key strategy designed to promote corporate innovation, responsibility and citizenship (Blowfield Citation2007; Aaron Citation2012). This also fits the developmental, philanthropic and interventionist posture that multinationals construct around their work in local communities which sees them building schools, hospitals and roads and offering scholarships to indigent students (Sharp Citation2006). Within the Niger Delta, many of the critics of oil multinationals have had to at least concede that their CSR investments have offered significant palliative development support in many places where the state has been absent as a socially responsible force (Aaron and Patrick Citation2013; Adeola and Adeola Citation2019).

These positive interventions notwithstanding, many critics have pointed to fundamental issues with the very notion of CSR, and have cast doubt on its overall potential for aligning with the public good. Shamir (Citation2004), for instance, dismisses all the investments that multinationals make in CSR as simply cynical public relations. This implies that CSR is little more than a tool for reputational management by multinationals according to Porter and Kramer (Citation2002). In a world where the public image is easily constructed (and destroyed) through a ‘democratised’ social media, multinationals have become as vulnerable as they are powerful in controlling how their publics see them. These publics are not just local communities but – crucially – shareholders, business associates and customers who can significantly impact on profits. Multinationals therefore consider CSR critical to justifying market penetration and profit maximisation. According to Orock (Citation2013), this is a new way of expressing neoliberal capitalism in a language that effectively conceals its most destructive impacts, thereby guaranteeing its continued toleration by the subaltern class.

Embedding itself within an increasingly fractured social environment, CSR in many of Africa’s extractive contexts becomes what Orock (Citation2013) called a ‘new discursive arena’ in which an astute new face is being given to global capital (Sharp Citation2006) in ways that are capable of exerting subtle influences on everyday resistance to its most adverse effects. Critical scholars who draw the link between CSR and advocacy and/or resistance efforts point out the ways in which social investments by multinationals can become a part of the architecture of resistance created by business to counter, disperse or dilute opposition to harmful extractive practices (Doane Citation2005; Wall Citation2008).

In spite of these efforts, however, the true power of CSR is derived not so much from multinationals’ ability to claim to have done specific good in needy communities as from the fact that that ‘doing good’ is backed up by a global meta narrative which, according to Orock (Citation2013), is reconstructing notions of responsibility in ways that conceal the negative impacts of business. This meta narrative is headlined by major initiatives like the United Nations (UN)’s Global Compact (Kell Citation2003). This ambitious UN programme, launched by the late Secretary General Koffi Annan, purports to be a ‘call to companies to align strategies and operations with universal principles on human rights, labor, environment and anti-corruption, and take actions that advance societal goals’ (UN Global Compact Citation1999). It is ‘a multi-stakeholder initiative involving diverse actors such as governments, companies, labor and civil society organizations, and the UN’ (Deva Citation2006, 115). By co-locating profit-making and social goals, and business and civil society, the Global Compact allows multinationals to project the narrative of a common goal set in a common global future, thus obscuring the underlining exploitative power relations that underpin global profit-making, whether in labour practices or in environmental policies. Nowhere is this calculated obscurantism more potent than in the extractive sector, where the very process of value production is steeped in exploitation and power.

The critical views about CSR discussed above are connected to misgivings held by many communities about a long history of corporate irresponsibility in Africa’s extractive sector and its correlation with violent conflict on the continent (Alao Citation1999; Maconachie Citation2014). For instance, between 1997 and 2014, there were about 888 conflicts, each involving at least 25 deaths, that can be linked to resources in Africa (ACLED Data Citation2014). Many analysts have directly linked resource-driven violent conflicts in Africa to the economic distortions, competition and corruption that large-scale extraction introduces into fragile economies (Felbab-Brown and Forest Citation2012). Arezki and Gylfason (Citation2013) argue, for instance, that higher resource rents accruing to countries without strong democratic institutions generates higher levels of corruption and thus disproportionately low levels of state investment in social services. This lack of investment, when combined with competition for access to patronage systems (Oppong Citation2020), often results in the collapse or re-shaping of state authority and ultimately in violent insurgencies. This is the case with Nigeria’s Niger Delta as well as other resource-rich sites like the DRC’s diamond-rich Kivu region.

In response to these conditions and the suspicion with which traditional philanthropic models of CSR are viewed, advocacy groups across the world now call for new forms of interaction as well as new sites for that interaction with business (Blowfield Citation2007; O’Laughlin Citation2008; Aaron Citation2012). These calls have translated into new CSR models that encourage a collapse of the barriers between business and advocacies (Idemudia and Osayande Citation2016) – or, in UN language, the creation of a compact that is fundamentally transactional.

Hegemonic incorporation and the business–NGO relationship

The transactional compact between business and NGOs provides significant benefits for both. For businesses, it can offer a protective layer of legitimacy that allows harmful social and environmental practices to continue or, in best cases, it improves the relationship with communities living around extraction sites (Coumans Citation2011; Egbon, Idemudia, and Amaeshi Citation2018). For NGOs, however, the funding received from businesses is often critical for organisational survival, and the relationships that they enter into with multinationals within the framework of multistakeholder CSR projects can sometimes disproportionately increase their visibility and reach.

Many analysts recognise the impacts that donor funding can have on NGOs with regard to accountability (Moncrieffe Citation1998; Martens Citation2001), voice and legitimacy (Guo and Musso Citation2007), and organisational survival (Cooley and Ron Citation2002). How the funds are accessed, mobilised and evaluated can, however, also have significant implications for NGOs. Cooley and Ron (2012) draw on the new economics of organisation (NEO) theory to show that incentives created by contractual relations, transaction costs, property rights and competition for funds could have wide-ranging impacts on the organisational behaviour of civil society groups. They provide an interesting analysis of this problematic in their study of the impact of market-based funding policies on transnational organisations. They note that attempts by international organisations and NGOs to reconcile material pressures, created by market incentives, with normative motivations often end in outcomes that are ‘dramatically at odds with liberal expectations’ (Cooley and Ron Citation2002, 6).

The implications of this are that marketisation policies like competitive bidding and renewable contracting can, by their very presence, significantly undermine the long-term stability of NGOs. While this is itself potentially damaging for the ability or even willingness of NGOs to maintain a normative agenda, the hegemonic incorporation emerging out of the co-location of extractive multinationals and NGOs within CSR networks is perhaps even more so. It fits what Tvedt (Citation2004, 140) described as an aid channel that serves as ‘the transmission belt of a dominant discourse tied to western notions of development’.

Gramsci’s work on hegemony provides us with a useful way to think about the role of multinationals in NGO network-building and how CSR is deployed to achieve this role. He argues, for instance, that hegemony is obtained through the cooptation of civil society, who can then be deployed to obtain the acquiescence of other parts of society (Gramsci Citation1971; Katz Citation2006). He notes, however, that civil society can also be central to resistance because they – as Sassoon (Citation1982) puts it – are the ‘creative space’ of resistance where subaltern groups can coalesce and engage in counterhegemonic action. This counterhegemonic action, Cox (Citation2002) figures, occurs within the context of a global civil society.

This view of civil society as bastions of resistance is increasingly being undermined by the incorporation of NGOs into the orbit of capital through multi-stakeholder networks being created to facilitate CSR agendas. That ‘creative space of resistance’ that Sassoon (Citation1982) refers to is thus being structured by the very forces that civil society attempts to challenge. This represents a weakening of counterhegemonic forces not by their evisceration, but by their incorporation. One can, of course, convincingly refer to multi-stakeholder networks involving NGOs, businesses, governments and international organisations as essential spaces within which the less powerful can have their voices heard (Aaron Citation2012; Wall Citation2008; Doane Citation2005). This is what Keck and Sikkink (Citation1998) described as NGOs playing leverage politics by using networks to exert pressure on more powerful actors like multinationals and states.

Yet there is a lot to be said for thinking about the NGO networks built in the context of multinational CSR as adverse incorporation rather than ‘engagement’, ‘participation’ or ‘cooperation’. Writing about marginality, inclusion and chronic poverty, du Toit argues that the fact of participation does not automatically mean that all actors do so on terms favourable to them. As Du Toit (Citation2004, 1001) puts it, ‘what defines marginality is not exclusion (or even imperfect inclusion) but the terms and conditions of incorporation’. It is in this sense that Gramsci’s point about civil society being a part of the architecture of hegemony becomes relevant.

In many ways, the bureaucratisation and/or corporatisation of civil society fits into a broader movement that one might tie to the emergence of a middle class for whom the incorporation of moral panics (about issues as diverse as the environment, racism, corruption, bad governance, or nationalism) is essentially more than an ideologically engagement with the world, but something very much a part of the requirements for participating in the neoliberal world. In essence, capital is responding – for good or bad – to the very implications of its accumulative and distributive logics but doing so in a way that privileges economic incentives as well as a gradualist approach. Many scholars have provided powerful commentaries of this market trend, from how it affects feminist movements (Zeisler Citation2017) to its impact on local environmental movements (Iwilade Citation2012). Dauvergne and LeBaron (Citation2014) offer an exceptionally incisive critique of what they call the ‘corporatisation of activism’ and point in particular at the way corporations are pumping money into institution-building in the voluntary sector, thereby essentially constructing a non-profit industrial complex in which, rather than challenging the establishment, NGOs seek to accommodate it.

Oiling civil society: the case of Chevron’s GMoU in Nigeria’s Niger Delta

The hegemonic relations that emerge from the partnership of powerful multinational oil companies and adversely incorporated NGOs is not all that surprising. Indeed, the survival of many advocacy groups, if one is to take the counsel of Cooley and Ron (Citation2002), is linked precisely to their ability to function within these sorts of relationships, and how well they are able to leverage these to construct and maintain a veneer of social legitimacy with local communities. This balancing act between Gramsci’s two ‘blocs’ of historical action – one as tools (witting or otherwise) of global capital and the other as forces of resistance and reform – is made possible by the careful structuring and posturing deployed by multinationals as well as the gentrification of the resistance landscape in ways that delegitimise disruptive social relations. The case selected here is particularly useful to illustrate the innovative ways in which multinationals are able to (re)invent the very nature of dissidence and the unwitting complicity of a generally well-meaning civil society.

Before talking about Chevron, it is useful to provide a very brief contextual description of the Niger Delta. This will allow readers unfamiliar with the region to situate the discussion in context. The Niger Delta is Nigeria’s oil-producing region. It is a complex and biodiverse ecosystem that supports a thriving agrarian and fishing economy. Hanging over the lives of its 30 million plus people, however, is the highly lucrative oil economy from which an average of 1.8 million barrels are extracted every day and inserted into the global energy market. At the core of the Niger Delta’s violent landscape is a resentment of the inequities associated with the distribution of the wealth extracted by the oil industry (Idemudia Citation2011) and the high-handed treatment the state routinely metes out to individuals and groups that demand redress (Ugor Citation2013).

Discontent over the impact of the oil industry on livelihoods, social life and political life in the Niger Delta is driven by several key factors. These include the environmental devastation that decades of oil spills, gas flares and excavation have inflicted on the delicate biodiversity of the delta (Okonta and Douglas Citation2001), resentment of the perceived unfairness of the distributive logics of resources accruing from oil (Orogun Citation2010), widespread economic distortion and livelihood devaluation (Ikelegbe Citation2006), routine and systematic repression by the armed services (Ifeka Citation2004), and the creation of a general climate of instability and fear in the region. All these issues have created a climate of distrust and resentment that is directed at oil multinationals, the Nigerian state, and national and local elite coalitions, but also at rival communities and social groups within the region. Detailed discussion of the various ways in which the oil sector has structured social, economic and political life in the Niger Delta can be found in the rich literature on the subject headlined in part by the works of Watts (Citation2008), Okwechime (Citation2011), Nwajiaku-Dahou (Citation2012), Umejesi and Akpan (Citation2013), Obi (Citation2014) and Adunbi (Citation2015).

Chevron is one of the major oil multinationals in the Niger Delta and it operates a joint venture agreement with the Nigeria National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC). As of 2015, the company produced a daily average of about 224,000 barrels of oil, 246 million cubic feet of natural gas and 6000 barrels of liquefied petroleum gas (Chevron Nigeria Limited Citation2016). This massive extraction operation spans parts of the main Niger Delta states Delta, Bayelsa and Rivers and covers the territory of some 420 communities. The company also has large interests in the Agbami field – an offshore oil field measuring 182 square kilometres that produces about 129,000 barrels of oil per day – as well as in other large oil fields in the central and eastern parts of the Delta region.

As was the practice of most of the oil majors operating in the Niger Delta, Chevron used to base its CSR projects on individual MOUs signed with the various communities who held claims to the lands in which the company did business (Hoben et al. Citation2012). For instance, as the result of a peaceful but tenacious protest by the community’s women, Chevron signed an MoU with the town of Ugborodo in Nigeria’s Delta State on 17 July 2002, which included a commitment to infrastructure investments like the sandfilling of Ugborodo New Town, the connection of Ode-Ugborodo to Chevron’s electrical grid, the provision of scholarships and educational bursaries, employment of indigenes and the award of supply contracts to indigenous companies.

But, as many of the oil majors in the Niger Delta quickly realised, it became apparent that these MoUs were not only divisive but were actually ineffective models through which the oil multinationals could show good faith to communities that had become immensely cynical about ‘development interventions’ framed by corporate profit motives. For instance, in the Ugborodo case noted above, rather than becoming a source of stability, dissatisfaction with the implementation of this hard-fought MoU later became the source of violent protests in 2005 which resulted in fatalities and effectively disrupted Chevron’s operations, costing the company millions of US dollars (Ukeje Citation2004).

In response to an outbreak of violence in many of the communities in which Chevron operated, and the consequent increase in attacks on its facilities as well as against the schools, hospitals and other such similar social projects the company had provided as CSR, the company began to rethink its CSR strategy. This became especially urgent by March 2003, when major violence erupted in and around Warri in Delta State, mainly between various Ijaw and Itshekiri communities. Details of this particular outbreak of violence can be found in Watts (Citation2004). It suffices to note here that Chevron was accused by the Ijaw militia of aiding the Itshekiri as a part of its broader divide-and-rule strategy of domination in the region. Chevron’s terminal at Escravos was consequently attacked and the company reportedly lost about 440,000 barrels of crude oil production as a result of the violence. Flow stations belonging to Chevron were also destroyed at Olero and Dibi in violence that claimed over a hundred lives and injured and displaced thousands (Human Rights Watch Citation2003).

As a result of this violence, Chevron was forced to pull out of the Niger Delta and declare force majeure on its exports, losing more than USD 1 billion in the process (Human Rights Watch Citation2003). Later that year, the company drew up a GMoU that had, among other things, the explicit goals of promoting ‘unity rather than competition among communities’ and reducing ‘400 individual agreements to a more manageable set of relationships’ (Chevron Nigeria Limited Citation2016). With this, Chevron began to harmonise and consolidate its CSR infrastructure.

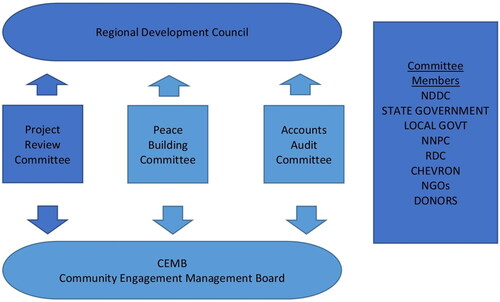

It started by encouraging the formation of what it referred to as Regional Development Councils (RDCs). These were to act as representatives of clusters of communities hosting Chevron installations and were grouped by region and ethnicity. Eight such RDCs were formed across the five core Niger Delta states of Bayelsa, Rivers, Delta, Cross River and Akwa Ibom. These RDCs were helped in their ‘development work’ by project review, peacebuilding and accounts audit committees. shows the way Chevron’s GMoU works.

Figure 1. Chevron Nigeria Limited GMoU model.

Abbreviations. NDDC, Niger Delta Development Council; NNPC, Nigeria National Petroleum Company; RDC, Regional Development Council; NGOs, Non Governmental Organisations.

This deliberate harmonisation of Chevron’s CSR programme had the impact of streamlining the company’s funding agenda to its host communities and ostensibly increased both their participation and their sense of ownership in the interventions funded by Chevron. Three issues are particularly relevant here. The first is the question of why Chevron shifted its strategy from individual MoUs to the GMoUs. The second is what impact this shift had on NGO networks and relationships. The third is how Chevron’s relationship with communities changed in the areas where the GMoUs were operational.

To understand the institutional reasons behind the movement towards GMoUs, it is useful to turn once again to the Ugborodo case. Explaining its shift from individual MoUs in Ugborodo, Chevron, (in a presentation made to Amnesty International and cited in Amnesty International Citation2005), stated that ‘The new MoU provides several avenues for seeking third party mediation and resolutions to disagreements other than employing threats and the force of violence’. This ‘third party mediation’ meant that actors who were previously outside of the MoUs that communities agreed with Chevron were brought in, in a move that significantly increased the number of ‘stakeholders’ involved in the negotiation and implementation of agreements between the company and communities. The implication of this expansion was a dilution of the militant voice of communities and the creation of a system of exchange that was bureaucratic, ‘civil’ and ultimately conducive to extraction activities. The logic of the new system was to build safeguards into the exchange between Chevron and the communities, which ensured that dissatisfaction with the company did not necessarily lead to the breakdown of the compact and thus the disruption of oil extraction.

It is particularly interesting to note that NGOs that played a role in Chevron’s GMoUs from across the Niger Delta were either directly nominated by Chevron itself or are sub-grantees funded by NGOs funded by Chevron. This meant that the ‘third party mediators’ referenced by Chevron above were effectively selected and paid for by the company whose activities and intervention was to be audited. The case of the Egbema-Gbaramatu Communities Development Fund supported by Chevron in 2005 is instructive here. For instance, The New Nigeria Foundation, an NGO that was central to the Egbema-Gbaramatu GMoU, had a long running partnership with Chevron, including for staff training, before it was nominated to serve as a ‘third party’ in the negotiations with the communities. The local community initially rejected this NGO on the basis that allowing Chevron to nominate the mediator amounted to granting the company even more powers than it currently had in relation to communities. This raises the familiar question about where NGO accountability ultimately rests in contexts such as this. Gray, Bebbington, and Collison (Citation2006), for instance, described the NGO accountability pathway as ultimately, or perhaps inevitably, leading towards the ‘colonisation’ of NGOs by corporate capital as a direct consequence of their dependence on the goodwill of capital or of individuals whose wealth is dependent on firms. Many other scholars have come to similar conclusions on the subject in varied contexts (O’Dwyer and Boomsma Citation2015). It is difficult to come to a different conclusion when one assesses the relationships constructed by Chevron’s GMoUs.

While the GMoUs created a dependent relationship between civil society and Chevron, perhaps their most salient impact was how they shaped the nature of the relationship between key parts of the civil society in Chevron’s areas of operation. Reflecting in 2012 on the 2008 renegotiation process for the company’s GMoU in Egbema-Gbaramatu, a Chevron staff involved in the process, Deji Haastrup (Harvard University Citation2012), noted:

What’s been surprising is how well things have turned out. When we were doing the facilitation for renegotiating the GMoU after the first three years, we actually had, for the first time, groups sitting in the same room that had never spoken to each other for several months, even years. Groups that had been involved in destroying each other’s homes, in burning down whole communities, were sitting at the table and talking about one subject and that subject is something we put on the table – it was the GMoU.

Haastrup’s point that the GMoUs created opportunities for multiple voices to connect within a space effectively funded and controlled by the company is instructive and fits with my earlier argument that they were sites for hegemonic control of capital in spite of the rhetoric of participation and ownership around which this process is sold to the public. Indeed, NGOs recognise this influence and the ways in which it impacts on how advocacies are done and who is included in that process. By bringing the different NGOs under a single funding and operational structure, Chevron inadvertently increased interaction between many of the participating NGOs at a time when competition for donor funding was especially intense. Loye (Citation2014), who was a staff of the Foundation for Partnership Initiative in the Niger Delta (PIND), which was one of the key partners tasked with deploying this NGO network infrastructure in the region, described it thus:

The Chevron project was good for everyone. It came around the time we were all working on our own community development foundations, I think that was sometime in 2004 or ‘5. They had this idea of improving [Civil Society Organisation] CSO participation in their CSR projects, they even involved communities in picking projects. It was also good to see different NGOs working together for a change. You know sometimes this grant race gets hot? After all, we seek the same funds from the same people. But what can we do? The Chevron project was well resourced, so many NGOs, especially the small ones, even made it their main full-time gig. We all worked together thanks to Chevron. Many of the networks I built at that stage were through the Chevron RDCs. Some of those networks still remain good friends today and we work together on projects, we share consulting information and invite each other to programmes. That’s the way this thing works.

One important example of how Chevron’s GMoU manufactures consent through the creation of aligned NGOs and activist networks was the funding of an organisation called Partners for Peace (P4P) as a sub-grantee of PIND. This network claims a membership of more than 10,000 activists and organisations across the nine states of the Niger Delta. Many of these activists operate as peace volunteers who focus on supporting mediation efforts in their communities. It is important to note that these volunteers are not necessarily willing tools of multinational capital. To the contrary, some are in fact driven by an idealistic wish to support mediation and conflict-resolution efforts in their communities and are blissfully unaware that their work is being funded by the very multinationals that they regard as central to conflict in the region. Some, of course, also have more personal motives, including using their volunteer work to gain access to ‘economic empowerment’ programmes that are designed to provide them with capital for business, or to gain training in specific economic skills, or simply consider themselves workers. None of these motives suggests that members of P4P are willing tools of capital. In fact, it appears that many of the members at the grassroots seem to be blissfully unaware of precisely where funding actually comes from. They regard P4P and PIND as their funders and therefore see no contradiction between their generally held resentment of oil multinationals and the financial thread that links back to them. But the personal motive of the volunteers and their being unaware of the funding thread is irrelevant to how the normative hegemonies constructed by Chevron impacts on their behaviour within the social landscape of the delta.

It is more important to imagine the sheer scale of this operation and the subtle but far-reaching influences it exerts on the politics of resistance in the Niger Delta. P4P is part of a growing network of NGOs that promote a gentrified and bureaucratic peacebuilding project that funnels legitimacy through networks of capacity-building and training programmes and away from social actions like mass protests that challenge power and undermine corporate profits. These programmes are aimed at building a sense of community among the ‘peace volunteers’, effectively binding them to a shared understanding of peace and to shared norms of acceptable conduct within the landscape of resistance. This conduct is, of course, principally invested in an aversion to disruption and in the creation of social incentives that encourage a ritual of engagement that is neither confrontational nor fundamentally questioning of the logics of oil extraction.

The P4P officially declares one of its goals as fostering collaboration around the idea of peacebuilding across various stakeholder groups in the Niger Delta. It also aims to ‘proactively identify and reach out to prospective partners within and outside Nigeria that share the same objectives as the P4P Network, to establish strategic and constructive working relationships necessary to better equip and sustain its work’ (P4P 2021). While these goals are innocent enough, the emphasis on building a network of ‘positive actors’ through ‘facilitation, small grants and capacity building’ (P4P 2021) highlights the focus on a gentrified pseudo-resistance landscape that does little to unsettle oil multinationals or indeed the Nigerian state itself. It is no wonder, then, that whereas organisations like the Movement of the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) in the time of Saro Wiwa, or more recently the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) and the Niger Delta People’s Volunteer’s Force (NDPVF), face brutal military responses, the state and oil multinationals are generally comfortable with and supportive of the work of networks like P4P.

It is important to note that this Chevron model is not unusual, as many of the oil majors now have similar arrangements. One other example is the Akassa Development Foundation (ADF) which was conceived and funded by Statoil/BP (Kimenyi et al. Citation2014). Scholars like Idemudia (Citation2017), Idemudia and Osayande (Citation2016), Aaron (Citation2012) and Egbon, Idemudia, and Amaeshi (Citation2018) have provided excellent analyses of the deployment of the GMoU model by various other companies operating within the Niger Delta. The scale of the Chevron GMoU is, however, significantly larger than that of most other oil multinationals operating in the Niger Delta and thus has far-reaching implications for the landscape of resistance.

demonstrates the institutional breadth of the Chevron operation but does little to capture the sheer number of activists who get caught in its net, many of them unknowingly. But perhaps more importantly, it does not show how positive (or at least accommodating) attitudes to oil multinationals are cultivated by the networks of relationships and norms built by participation in the GMoU.

Table 1. Some NGOs involved in Chevron’s General Memorandum of Understanding (GMoUs), 2008–2021.

It should be noted that even though violent resentment to Chevron has fallen dramatically in the last decade and a half, its GMoU approach has not rendered it immune to violent disruptions of its extractive activities. In 2016, for instance, as the compact between Niger Delta militant groups and the federal government began to break down over how the 2009 Presidential Amnesty Programme should be run, Chevron’s installations in Escravos were attacked, causing the company to lose production capacity of around 35,000 bpd (The Guardian Citation2016). Why would this kind of breakdown happen in spite of the company’s best efforts to cultivate relationships across the region that should normally set it apart and build its image as a positive force in the Delta? It appears that because the GMoU is built around the gentrification of resistance, it has become a victim of its own success. The actors that a civil dialogic landscape incorporates are not necessarily those most likely to violently challenge perceived exclusions in the oil economy. By framing peace around civil behaviour, and delegitimising disruption, Chevron’s GMoU is captive to its own structures and inevitably engages with organised and ‘recognised’ actors. The very fluid nature of social relations in the region, with actors straddling multiple identity spaces and constantly recalibrating relationships, makes it apparent that this rigid and structured model is unlikely to be nimble enough to vaccinate the company against violent action should the political climate shift towards such. It also appears that the reduction in violence has more to do with the amnesty programme that was launched by the federal government and was essentially a very wide-ranging programme that targeted the violent disruptors in a deliberate way.

Conclusion

What I have done in this paper is to explore how oil multinationals attempt to shape the landscape of resistance to the impacts of their activities in extractive contexts. Using Chevron’s GMoU in the Niger Delta of Nigeria as an entry point, I highlighted the subtle ways in which the company is able to encourage the construction of a shared notion of peace within civil society and use this desire for peace to constitute NGO coalitions and networks that inevitably protect its interests.

While negotiating interview access with a senior member of P4P, they told me pointedly that ‘I do not want my donor to be written about in a bad light’ (Kemi, Interview, Citation2021). When I asked why they felt the need to protect Chevron, when they had expressed views critical of the conditions in the Niger Delta and of the general approach of oil multinationals, the response was that without peace there could be no economic development and that people’s lives depended on ‘economic empowerment’. I then asked, ‘What about justice and equity?’ I was told ‘peace is more important’. In many ways, this retort by my interlocutor captures the logic of peacebuilding in the Niger Delta. This idea that peace is an aspirational end for and to which all sacrifices must be made fundamentally misreads the universe of grievances that animate violence in the Delta region. It does not, for instance, account for actors for whom peace essentially represents a profound questioning of their very sense of being (Iwilade Citation2019), or those whose distorted livelihoods cannot necessarily be reconstituted by peace. It also does not support a system of power relations in which social movements and civil society are able to resist incorporation or cooption by corporate entities.

While the proliferation of NGOs in the Delta has no doubt created a shared notion that legitimate ‘resistance’ is fundamentally peaceful and receptive to the inevitability of extraction, the case of Chevron’s GMoU shows that this notion is only prevalent within civic circles in which institutional survival and social mobility are dependent on connection to the landscape of extraction itself. The reality that Chevron, despite its much larger investment in its GMoU, has not appeared to fare much better than other oil majors during major violent breakdowns, highlights the ineffectiveness of a business–NGO compact that excludes disruptive actors like the militants of the Niger Delta. The gentrification of the civic landscape – that is, the rendering it civil – might naturally appear to support goals of minimal disruption for oil multinationals, but it does little to insert actors for whom disruption is key to how they imagine their role in the region.

As the above demonstrates, the Niger Delta offers useful insights into how we might think about broader questions of NGO accountability and about the cautionary lessons that must be drawn from a conception of the expansion of civil society as necessarily democratic, especially when it focusses on density rather than on relative power. Bush and Hadden (Citation2019) have argued convincingly that NGO density encourages competition rather than cooperation between NGOs and that this undermines the power that they have relative to donors or, indeed, to the issues they work in. Yet the case of the Chevron GMoU in the Niger Delta suggests that even where density generates cooperation rather than competition, it still does not improve the relative position and/or ability of NGOs to effectively represent marginal voices. Because NGOs are implicated in broader CSR agendas, like the UN’s Global Compact, which proceed from the assumption that business/capital is a public good, they are increasingly comfortable with the language of ‘constructive engagement’ that inevitably subjects them to rules of behaviour that avoid disruption. This does little to unsettle or trouble power and provides little incentive for major shifts in business practices in places like Africa.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Sola Obisesan for his assistance with data collection during research for this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Akin Iwilade

Akin Iwilade is Lecturer of African studies at The University of Edinburgh. He has previously held faculty positions at the University of Leeds, UK, and the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria, and currently serves as Editor for the Canadian Journal of African Studies and Reviews Editor for African Affairs. His research interests include the social anthropology of youth in Africa, the making and aesthetics of gangs and crowds within postcolonial cities, and the politics of oil extraction in contexts like the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. His ongoing work in these areas is funded by the British Academy and the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Bibliography

- Aaron, K. 2012. “New Corporate Social Responsibility Models for Oil Companies in Nigeria’s Delta Region: What Challenges for Sustainability?” Progress in Development Studies 12 (4): 259–273. doi:10.1177/146499341201200401.

- Aaron, K., and J. M. Patrick. 2013. “Corporate Social Responsibility Patterns and Conflicts in Nigeria’s Oil-Rich Region.” International Area Studies Review 16 (4): 341–356. doi:10.1177/2233865913507573.

- ACLED Data. 2014. “Resource Related Conflicts in Africa.” https://www.crisis.acleddata.com/resource-related-conflict-in-africa/

- Adeola, D., and O. Adeola. 2019. “The Extractive Sector and Corporate Social Responsibility: A Case of Chevron Nigeria.” Communicatio 45 (3): 40–66. doi:10.1080/02500167.2019.1639783.

- Adunbi, O. 2015. Oil Wealth and Insurgency in the Niger Delta. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Alao, A. 1999. “Diamonds Are Forever … but So Also Are Controversies: Diamonds and the Actors in the Sierra Leone Civil War.” Civil Wars 2 (3): 43–64. doi:10.1080/13698249908402414.

- Amnesty International. 2005. “Nigeria: Ten Years on, Injustice and Violence Haunt the Oil Delta.” https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/afr440222005en.pdf

- Arezki, R., and T. Gylfason. 2013. “Resource Rents, Democracy, Corruption and Conflict: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of African Economies 22 (4): 552–569. doi:10.1093/jae/ejs036.

- Blowfield, M. 2007. “Reasons to Be Cheerful? What We Know about CSR’s Impact.” Third World Quarterly 28 (4): 683–695. doi:10.1080/01436590701336523.

- Brass, J. N. 2012. “Blurring Boundaries: The Integration of NGOs into Governance in Kenya.” Governance 25 (2): 209–235. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2011.01553.x.

- Bush, S. S., and J. Hadden. 2019. “Density and Decline in the Founding of International NGOs in the United States.” International Studies Quarterly 63 (4): 1133–1146. doi:10.1093/isq/sqz061.

- Chevron Nigeria Limited. 2016. “Highlights of Operations.” https://www.chevron.com/worldwide/nigeria#highlightsofoperations

- Cilliers, J., and C. Dietrich. 2000. Angola’s War Economy: The Role of Oil and Diamonds. Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies.

- Cooley, A., and J. Ron. 2002. “The NGO Scramble: Organizational Insecurity and the Political Economy of Transnational Action.” International Security 27 (1): 5–39. doi:10.1162/016228802320231217.

- Coumans, C. 2011. “Occupying Spaces Created by Conflict.” Current Anthropology 52 (S3): S29–S43. doi:10.1086/656473.

- Cox, R. W. 2002. The Political Economy of a Plural World: Globalization and Civilization. New York: Cambridge: Routledge.

- Dauvergne, P., and G. LeBaron. 2014. Protest Inc: The Corporatization of Activism. Cambridge: Polity.

- de Koning, R. 2013. “Conflict between Industrial and Artisanal Mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC): Case Studies from Katanga, Ituri and Kivu.” Africa for Sale? 29: 181–200. doi:10.1163/9789004252646_009.

- Deva, S. 2006. “Global Compact: A Critique of the U.N.'s. “Public-Private” Partnership for Promoting Corporate Citizenship.” Syracuse Journal of International Law and Commerce 34 (1): 4.

- Doane, D. 2005. “Beyond Corporate Social Responsibility: Minnows, Mammoths and Markets.” Futures 37 (2-3): 215–229. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2004.03.028.

- Du Toit, A. 2004. ““Social Exclusion” Discourse and Chronic Poverty: A South African Case Study.” Development and Change 35 (5): 987–1010. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2004.00389.x.

- Egbon, O., U. Idemudia, and K. Amaeshi. 2018. “Shell Nigeria’s Global Memorandum of Understanding and Corporate-Community Accountability Relations: A Critical Appraisal.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 31 (1): 51–74. doi:10.1108/AAAJ-04-2016-2531.

- Felbab-Brown, V., and J. F. Forest. 2012. “Political Violence and the Illicit Economies of West Africa.” Terrorism and Political Violence 24 (5): 787–806. doi:10.1080/09546553.2011.644098.

- Furnaro, A. 2019. “Hegemony and Passivity in Mining Regions: Containing Dissent in North-Central Chile.” The Extractive Industries and Society 6 (1): 215–222. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2018.07.009.

- Gold, L. 2004. “The ‘Economy of Communion’: A Case Study of Business and Civil Society in Partnership for Change.” Development in Practice 14 (5): 633–644. doi:10.1080/0961452042000239788.

- Gramsci, A. 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

- Gray, R., J. Bebbington, and D. Collison. 2006. “NGOs, Civil Society and Accountability: Making the People Accountable to Capital.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 19 (3): 319–348. doi:10.1108/09513570610670325.

- Guo, C., and J. A. Musso. 2007. “Representation in Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations: A Conceptual Framework.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36 (2): 308–326. doi:10.1177/0899764006289764.

- Harvard University. 2012. “The Only Government We See: Building Company/Community Dialogue in Nigeria.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZibwGOWHVIA

- Heap, S. 2000. NGOs Engaging with Business: A World of Difference and a Difference to the World. Oxford: INTRAC.

- Hilhorst, D. 2003. The real world of NGOs: discourses, diversity and development. London: Zed Books.

- Hoben, M., D. Kovick, D. Plumb, and J. Wright. 2012. Corporate and Community Engagement in the Niger Delta: Lessons learnt from Chevron Nigeria Limited’s GMoU, Washington: CBI, available via: https://www.cbi.org/assets/files/Corporate%20and%20Community%20Engagement%20in%20the%20Niger%20Delta_Lessons%20Learned.pdf

- Human Rights Watch. 2003, December 17. “Nigeria: The Warri Crisis: Fueling Violence.” A1518. Accessed April 26, 2022. https://www.refworld.org/docid/402f6e7d4.html

- Idemudia, U. 2011. “Corporate Social Responsibility and the Niger Delta Conflict: Issues and Prospects.” In Oil and Insurgency in the Niger Delta: Managing the Complex Politics of Petro-Violence, edited by C. Obi and S. Rustad, 167–183. London: Nordic Africa Institute/Zed Books.

- Idemudia, U. 2017. “Business and Peace in the Niger Delta: What We Know and What We Need to Know.” African Security Review 26 (1): 41–61. doi:10.1080/10246029.2016.1264439.

- Idemudia, U., and N. Osayande. 2016. “Assessing the Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Community Development in the Niger Delta: A Corporate Perspective.” Community Development Journal 53 (1): 155–172. doi:10.1093/cdj/bsw019.

- Ifeka, C. 2004. “Violence, Market Forces and Militarisation in the Niger Delta.” Review of African Political Economy 31: 144–150.

- Ikelegbe, A. 2006. “The Economy of Conflict in the Oil Rich Niger Delta Region of Nigeria.” African and Asian Studies 5 (1): 23–56. doi:10.1163/156920906775768291.

- Iwilade, A. 2012. ““Green” or “Red”? Reframing the Environmental Discourse in Nigeria.” Africa Spectrum 47 (2-3): 157–166. doi:10.1177/000203971204702-309.

- Iwilade, A. 2014. “Networks of Violence and Becoming: Youth and the Politics of Patronage in Nigeria’s Oil-Rich Delta.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 52 (4): 571–595. doi:10.1017/S0022278X14000603.

- Iwilade, A. 2019. “Temporalities of ‘Doing’: The over-Youth and Their Navigations of Post-Violence Contexts in Africa.” In Youth Inequality and Social Change in the Global South, Springer Series Perspectives on Children and Youth, edited by H. Cuervo and A. Miranda, 85–98, Singapore: Springer.

- Johansson, A., and S. Vinthagen. 2016. “Dimensions of Everyday Resistance: An Analytical Framework.” Critical Sociology 42 (3): 417–435. doi:10.1177/0896920514524604.

- Katz, H. 2006. “Gramsci, Hegemony, and Global Civil Society Networks.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 17 (4): 332–347. doi:10.1007/s11266-006-9022-4.

- Keck, M. E., and K. Sikkink. 1998. Activists beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/j.ctt5hh13f.

- Kell, G. 2003. “The Global Compact: Origins, Operations, Progress, Challenges.” Journal of Corporate Citizenship 2003 (11): 35–49. doi:10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2003.au.00007.

- Kemi. 2021. (Pseudonym), Staff of Partnership for Peace, a Sub-Grantee of PIND, Which Is a Network of Multiple NGOs and Thousands of ‘Peace Activists’ Working in the Niger Delta.

- Kimenyi, M., Temesgen, T. Deressa, J. E. Pugliese, A. Onwuemele, and M. Mendie. 2014. “Analysis of Community-Driven Development in Nigeria’s Niger Delta Region: Use of the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) Framework.” Africa Growth Initiative Working Paper, No. 14, AGI, PIND & NISER, 1–44.

- Lawrence, R. 2007. “Corporate Social Responsibility, Supply-Chains and Saami Claims: Tracing the Political in the Finnish Forestry Industry.” Geographical Research 45 (2): 167–176. doi:10.1111/j.1745-5871.2007.00448.x.

- Le Billon, P. 2010. “Oil and Armed Conflicts in Africa.” African Geographical Review 29 (1): 63–90. doi:10.1080/19376812.2010.9756226.

- Loye. (Pseudonym) 2014. Staff of Foundation for Partnership Initiatives in the Niger Delta (PIND), Major CSR Vehicle Funded by Chevron with an Initial Endowment of 50 Million USD; interview 2014.

- Maconachie, R. 2014. “Dispossession, Exploitation or Employment? Youth Livelihoods and Extractive Industry Investment in Sierra Leone.” Futures 62: 75–82. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2013.08.003.

- Martens, K. 2001. “Non-Governmental Organisations as Corporatist Mediator? An Analysis of NGOs in the UNESCO System.” Global Society 15 (4): 387–404. doi:10.1080/13600820120090909.

- Mittelman, J. H. 2011. Contesting Global Order: Development, Global Governance, and Globalization. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203836668.

- Moncrieffe, J. 1998. “Reconceptualizing Political Accountability.” International Political Science Review 19 (4): 387–406. doi:10.1177/019251298019004004.

- Mueller-Hirth, N. 2009. “South African NGOs and the Public Sphere: Between Popular Movements and Partnerships for Development.” Social Dynamics 35 (2): 423–435. doi:10.1080/02533950903076568.

- Nwajiaku-Dahou, K. 2012. “The Political Economy of Oil and ‘Rebellion’ in Nigeria’s Niger Delta.” Review of African Political Economy 39 (132): 295–313. doi:10.1080/03056244.2012.688805.

- O’Dwyer, B., and R. Boomsma. 2015. “The Co-Construction of NGO Accountability: Aligning Imposed and Felt Accountability in NGO-Funder Accountability Relationships.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability 28 (1): 36–68.

- O’Laughlin, B. 2008. “Governing Capital? Corporate Social Responsibility and the Limits of Regulation.” Development and Change 39 (6): 945–957. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2008.00522.x.

- Obi, C. 2009. “Nigeria’s Niger Delta: Understanding the Complex Drivers of Violent Oil-Related Conflict.” African Development 34 (2): 103–128.

- Obi, C. 2014. “Oil and Conflict in Nigeria’s Niger Delta Region: Between the Barrel and the Trigger.” The Extractive Industries and Society 1 (2): 147–153. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2014.03.001.

- Okonta, I., and O. Douglas. 2001. Where Vultures Feast: Shell, Human Rights, and Oil in the Niger Delta. Sierra Club Books.

- Okwechime, I. 2011. “Oil Multinationals and the Politics of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Niger Delta.” In Perspectives on African Studies: Essays in Honour of Toyin Falola, edited by A. Alao and R. Taiwo, 2–38. Munich: Lincom Publishers.

- Onuoha, F. 2010. “The Geo-Strategy of Oil in the Gulf of Guinea: Implications for Regional Stability.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 45 (3): 369–384. doi:10.1177/0021909610364779.

- Oppong, N. 2020. “Between Elite Reflexes and Deliberative Impulses: Oil and the Landscape of Contentious Politics in Ghana.” Oxford Development Studies 48 (4): 329–344. doi:10.1080/13600818.2020.1844879.

- Oriola, T., K. D. Haggerty, and A. W. Knight. 2013. “Car Bombing “With Due Respect”: The Niger Delta Insurgency and the Idea Called MEND.” African Security 6 (1): 67–96. doi:10.1080/19392206.2013.759477.

- Orock, R. 2013. “Less-Told Stories about Corporate Globalization: Transnational Corporations and CSR as the Politics of (Ir)responsibility in Africa.” Dialectical Anthropology 37, no. (1): 27–50. doi:10.1007/s10624-013-9293-2.

- Orogun, P. 2010. “Resource Control, Revenue Allocation and Petroleum Politics in Nigeria: The Niger Delta Question.” GeoJournal 75, no. (5): 459–507. doi:10.1007/s10708-009-9320-7.

- Partners for Peace. 2021. “About Us.” https://p4p-nigerdelta.org/aboutp4p/

- Porter, M. E, and M. R. Kramer. 2002. “The Competitive Advantage of Corporate Philanthropy.” Harvard Business Review 80 (12): 5–16.

- Sassoon, A. S. 1982. “Hegemony, War of Position, and Political Intervention.” In Approaches to Gramsci, edited by A. S. Sassoon, 94–115. London: Writers and Readers.

- Shamir, R. 2004. “The De-Radicalization of Corporate Social Responsibility.” Critical Sociology 30 (3): 669–689. doi:10.1163/1569163042119831.

- Sharp, J. 2006. “Corporate Social Responsibility and Development: An Anthropological Perspective.” Development Southern Africa 23 (2): 213–222. doi:10.1080/03768350600707892.

- The Guardian. 2016. “Militants Blow Up Chevron Oil Facility, Vow More Attacks.” https://guardian.ng/news/militants-blow-up-chevron-oil-facility-vow-more-attacks/

- Tvedt, T. 2004. “Development NGOs: Actors in a Global Civil Society or in a New International Social System?.” In Creating a Better World: Interpreting Global Civil Society, edited by R. Taylor, 133–146. Bloomfield CT: Kumarian Press.

- Ugor, P. W. 2013. “Survival Strategies and Citizenship Claims: Youth and the Underground Oil Economy in Post-Amnesty Niger Delta.” Africa 83 (2): 270–292. doi:10.1017/S0001972013000041.

- Ukeje, C. U. 2004. “From Aba to Ugborodo: Gender Identity and Alternative Discourse of Social Protest among Women in the Oil Delta of Nigeria.” Oxford Development Studies 32 (4): 605–617. doi:10.1080/1360081042000293362.

- Umejesi, I., and W. Akpan. 2013. “Oil Exploration and Local Opposition in Colonial Nigeria: Understanding the Roots of Contemporary State-Community Conflict in the Niger Delta.” South African Review of Sociology 44 (1): 111–130. doi:10.1080/21528586.2013.784452.

- UN Global Compact. 1999. “UN Global Compact.” https://www.unglobalcompact.org/

- Wall, C. 2008. Buried Treasure: Discovering and Implementing the Value of Corporate Social Responsibility. Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing.

- Watts, M. 2003. “Economies of Violence: More Oil, More Blood.” Economic and Political Weekly 38 (48): 5089–5099. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4414347.

- Watts, M. J. 2004. “Antimonies of Community: Some Thoughts of Geography, Resources and Empire.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 29 (2): 195–216. doi:10.1111/j.0020-2754.2004.00125.x.

- Watts, M. 2008. “Blood Oil: The Anatomy of a Petro-Insurgency in the Niger Delta.” Focaal 2008 (52): 18–38. doi:10.3167/fcl.2008.520102.

- Zeisler, A. 2017. We Were Feminists Once: From Riot Grrrl to CoverGirl, the Buying and Selling of a Political Movement. Philadelphia: Perseus Book Group.