Abstract

The present study investigates the effects of different kinds of praise on 108 students in vocational education, using a similar design as the original mindset studies. Students worked on a set of Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices and either received praise for effort, received praise for intelligence, or were in the control group. Results were not in line with mindset theory. We expected differences in goal choice and performance after experiencing setbacks between students who were praised for effort or who were praised for intelligence, but both groups reacted in the same way. Our results are in line with previous studies that also did not succeed in finding a relation between mindset and academic performance. This study shows that even when the original procedure used in Mueller and Dweck’s experiments was followed, vocational education students were not influenced by the type of praise (i.e. mindset) to which they were exposed.

Dweck and colleagues’ puzzle experiments can be considered as the starting point of mindset theory. They offered children problems that were hard to solve, and wondered why some children perceived the problems as a challenge, whereas other children viewed them as evidence of their own lack of ability (Diener & Dweck, Citation1978, Diener & Dweck, Citation1980). Remarkable differences were found in the way children reacted to different kinds of praise in this situation. Children who received praise about their ability (e.g. ‘You must be smart to have solved this problem’.) showed a more helpless response to failure; they focused on the cause of their failure, such as concluding that they did not think themselves smart enough. On the other hand, children who received process praise (e.g. ‘You must have worked hard to solve this problem’.) showed a more mastery-oriented response. They focused on remedies for failure, such as looking for new strategies for solving the problems (Mueller & Dweck, Citation1998).

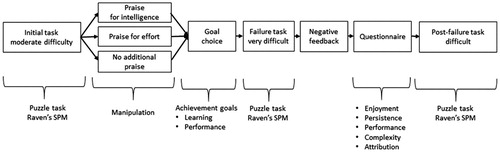

To gain a better understanding of this phenomenon, Mueller and Dweck (Citation1998) asked a group of fifth graders (ages 10–12 years) first to perform a task consisting of completing ten problems from the Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices (SPM; Raven, Raven, & Court, Citation2004), of moderate difficulty. After completing the problem all children were told that they performed well (e.g. ‘You did very well on these problems’.). Some children received additional praise for effort (e.g. ‘You must have worked hard’.), some received additional praise for intelligence (e.g. ‘You must be smart’.), and some received no additional praise (control group). After the initial praise, children were asked whether they preferred to continue with problems that were not so hard, so they could show how smart they were (performance goals) or with problems from which they could learn a lot (learning goals). The initial task was followed by a more difficult task from Raven’s SPM, to induce failure. After their poor performance on this task, all children received negative feedback and were asked to complete a questionnaire including questions about their desire to persist with the task of working on such problems, their task enjoyment, the quality of their performance, and attributions for their failure. Finally, the children received the third set of 10 problems from Raven’s SPM. Mueller and Dweck (Citation1998) found that the children who were praised for effort after the initial task chose more often problems that were framed as fulfilling learning goals, while children who were praised for intelligence chose more often problems that were framed as fulfilling performance goals. Furthermore, children who were praised for effort showed greater task persistence, greater task enjoyment, fewer low ability attributions, and better post-failure task performance compared to the children who were praised for their intelligence after the initial task. The results of the children in the control group, who received no additional praise, fell for all previous outcomes mentioned exactly in-between of those of the effort group and the intelligence group.

After Mueller and Dweck (Citation1998) had found these remarkable differences in the way children reacted to different kinds of praise, these findings formed the basis for the incremental and entity theory of intelligence or mindset theory. Furthermore, a distinction was made between growth and a fixed mindset (Dweck, Citation2006). When one believes that intelligence is malleable and can be developed by learning; one has a growth mindset or an incremental theory of intelligence. Alternatively, if one believes that intelligence is something that is possessed and cannot be changed, one has a fixed mindset or an entity theory of intelligence. People with a growth mindset attach more value to learning than to appearing smart, adopt learning goals, like to work harder, see setbacks as a challenge to cope with and are more motivated to persevere. In contrast, people with a fixed mindset prefer to look smart, adopt more performance goals, work as little as possible, and often have a helpless response to setbacks (Dweck & Leggett, Citation1988). Several studies have shown important consequences of adopting a growth mindset compared to a fixed mindset, such as enhanced academic performance over time (Blackwell, Trzesniewski, & Dweck, Citation2007), especially when students face challenging tasks (Davis, Burnette, Allison, & Stone, Citation2011; Mueller & Dweck, Citation1998), and for underperforming students (Paunesku et al., Citation2015; Rattan, Savani, Chugh, & Dweck, Citation2015).

The type of mindset one adopts is determined by prior experiences in the environment in which people grew up and is influenced by parents, siblings, peers, or teachers at school (Dweck, Citation2006; Pomerantz & Kempner, Citation2013; Rattan, Good, & Dweck, Citation2012). Therefore, psychological interventions have been developed to promote a growth mindset. Initially, these were small-scale personal interventions (Blackwell et al., Citation2007; Mueller & Dweck, Citation1998) that then evolved into classroom interventions supported by interactive computer programmes such as Brainology (https://www.mindsetworks.com/). To make these programmes more widely available, interactive online programmes were developed (Paunesku et al., Citation2015; Yeager et al., Citation2016). All of these programmes incorporate findings from recent neuroscience studies, such as the brain’s ability to grow. In most programmes, students learn that they can develop their brain by studying hard, in the same way as athletes engage in training to develop their muscles.

Due to the positive effects of mindset interventions, many schools have introduced programs to foster a growth mindset, like Brainology and PERTS (https://www.mindsetworks.com/; https://www.perts.net/orientation/hg). This is reinforced by the fact that mindset interventions are quite easy to implement and are rather cheap (less than $1 per student) or even free (Dweck, Citation2018). However, evidence that a mindset intervention is effective in a particular educational context (in this study in vocational education), is necessary before proceeding with its implementation. Therefore, mindset researchers have recommended piloting and refining mindset interventions before introducing them to other situations (Yeager & Walton, Citation2011).

Notwithstanding the fact that many mindset interventions have been shown to be effective, there is an increasing body of evidence concerning these interventions that does not support mindset theory, failing to find a statistically significant relation between mindset and academic performance (Bahník & Vranka, Citation2017; Bates, Citation2015; Chivers, Citation2017; Glerum, Loyens, & Rikers, Citation2018; Orosz, Péter-Szarka, Bőthe, Tóth-Király, & Berger, Citation2017). A recent pair of meta-analyses demonstrated weak effects of mindset interventions on academic achievement (Sisk, Burgoyne, Sun, Butler, & Macnamara, Citation2018). However, the results of the meta-analysis did show that students with low socioeconomic status, or students who are academically at risk, can benefit from mindset interventions. Researchers have also questioned the statistical methods that have been used in prior studies, the replicability of the mindset studies, and the small effect sizes that have been found (Chivers, Citation2017; Hattie, Citation2017). All these concerns are part of the discussion on the applicability of the mindset theory.

Dweck (Citation2017a, Citation2017b) has addressed the recently raised issues concerning mindset theory. Her response can be categorised into three types of explanations for the non-results found. First, mindset theory is often misinterpreted; it is considered to be a rather simple concept that can easily be passed on from parents or teachers to children or students. Although many parents or teachers claim to have a growth mindset, this does not automatically result in the corresponding behaviour towards their children or students; many people with a growth mindset fail to use process praise (Gunderson et al., Citation2013). Second, mindset interventions might have been applied by simply transferring them from one situation to another (e.g. an intervention that works for fifth graders simply being copied for undergraduate math students) without reproducing the intended psychological or educational experience, resulting in suboptimal interventions (Yeager et al., Citation2016; Yeager & Walton, Citation2011). Thirdly, fostering a growth mindset is especially beneficial for underperforming students and in difficult situations such as the transition from elementary to secondary school or difficult courses such as mathematics (Aronson, Fried, & Good, Citation2002; Burnette, O’Boyle, VanEpps, Pollack, & Finkel, Citation2012; Davis et al., Citation2011; Yeager & Dweck, Citation2012). As Dweck noted, ‘However, we are still working to understand who is not benefiting from the programmes and how we can make them more effective for more students’ (Dweck, Citation2017c, p. 141).

The present study addresses the issue of why some students are not benefiting from mindset interventions. It took Dweck and her colleagues several decades to develop mindset theory and to design the mindset interventions (Dweck, Citation2017c), and as Yeager and Walton (Citation2011) postulated, such psychological interventions are not quick fixes; they must be developed step-by-step and need careful evaluation. In fact, some recent studies that found effects of mindset interventions (e.g. Paunesku et al., Citation2015; Yeager et al., Citation2016) included clear descriptions of how their interventions were adjusted or refined based on mindset research. For instance, they shortened a two-session intervention into a single session and tested this in a pilot group to ensure that the intended effects remained intact. Or they altered the content based on feedback from the participants (e.g. examples of animals and people were replaced by examples of peers). In contrast, other recent studies (e.g. Donohoe, Topping, & Hannah, Citation2012; Orosz et al., Citation2017) that did not find a beneficial effect of mindset interventions or did not find a relation between mindset and academic achievement lacked a clear description of these adjustments. It seems that the materials and methods were just adopted from prior research without adjustments (e.g. materials used in primary schools in the United States were also used in a secondary school in Scotland, Donohoe et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, it appears that many researchers who have indicated that mindset interventions have beneficial effects on students first examined whether praise for effort had beneficial effects in the target population under study. However, researchers who did not find beneficial effects of mindset interventions, started directly with examining these interventions, without first testing the effect of different kinds of praise on performance (Bahník & Vranka, Citation2017; Orosz et al., Citation2017; Paunesku et al., Citation2015; Yeager et al., Citation2016). With this study, we aim to address Dweck’s question mentioned in the previous paragraph and to determine whether or not praise for effort might be beneficial for students within Vocational Education and Training. The results of our study will be beneficial not only for VET but also for education in general and can help to clarify why mindset interventions are not effective in certain settings. When the method we used shows success, investigating the effect of different kinds of praise can be used before schools start implementing mindset interventions.

In a previous study with VET students, we failed to find a positive relationship between mindset and academic performance (Glerum et al., Citation2018). In that study, we tested psychological interventions analogous to the Brainology programme and the interactive online programmes developed by Paunesku et al. (Citation2015) and Yeager et al. (Citation2016). However, in this present study, we build on the original mindset theory studies and investigate the main hypothesis of the study by Mueller and Dweck (Citation1998) with first-year VET students. We aim to investigate the previously mentioned issues addressed by Dweck (Citation2017a, Citation2017b), and, in particular, whether praise for effort might be beneficial for VET students. These students are especially expected to benefit from mindset interventions because they have just undergone a transition from a school for primary vocational education to a school for secondary vocational education (Dweck Citation2017a, Citation2017b). In the Dutch school system, after elementary school, students can go on to the general education track, but only if they perform well enough and meet the requirements; otherwise, they have to go on to primary vocational education. In their last year of primary vocational education, students can also make a transition to the general education track, but only if they perform well enough and meet the requirements. The VET students involved in the present study did not perform well enough to make the transition to the general education track. For students, this can be a disappointment that can negatively influence their motivation.

The Inspectorate of Education has stated in their annual report (Inspectorate of Education, Citation2014) that improving Dutch VET students’ motivation is an important challenge for VET. Compared to students in other countries Dutch students are ‘less willing to work through problems that are difficult, they do not remain interested in the tasks they start, and more than in other countries, they are likely to shy away from complex problems’ (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Citation2016, p. 84). Both the disappointment of not being able to follow the general education track and the lack of motivation are reasons why these students have a greater risk of dropping out. In line with the results of the earlier mentioned meta-analyses (Sisk et al., Citation2018), we expect VET students to benefit from mindset interventions.

The present study

Mueller and Dweck (Citation1998) postulated that praise for intelligence has more negative consequences for children’s motivation and achievement compared with praise for effort. By going back to this original hypothesis, instead of testing the effectiveness of a specific mindset intervention, the present study examined whether VET students respond differently to different types of praise. The effect of the different types of praise is the basis of mindset theory and mindset interventions. If this principle does not work in this population, it is unlikely that a classroom-level intervention will have an effect. By replicating the original praise procedures in a different student population, we go back to the effects of attribution, just as with the children in Mueller and Dweck’s (Citation1998) study. We want to investigate whether our students also show a mastery response when they attribute their failure to something they can influence (e.g. their effort) and whether they also show a more helpless response when they attribute their failure to something they cannot influence (e.g. their intelligence). These starting points are the basis for mindset interventions, so that if we do not succeed in validating this connection, then we certainly cannot expect that mindset interventions would be effective.

Our main hypothesis is similar to that in the original experiments by Dweck and Mueller: praise for intelligence has more negative consequences for students’ motivation and achievement compared with praise for effort. We expect that students who get praised for intelligence will prefer to choose tasks that ensure good performance and will, therefore, choose performance goal tasks, while students who get praised for effort will see their hard work as an opportunity to learn and will, therefore, choose learning goal tasks (Hypothesis 1). Students who are praised for their intelligence will attribute failure to (lack of) ability, whereas students who are praised for their effort, will attribute failure to (lack of) effort (Hypothesis 2). Furthermore, we expect that students who are praised for their intelligence will have more negative responses such as less persistence, less perceived enjoyment, lower perceived performance, and higher perceptions of complexity after setbacks (Hypothesis 3). Finally, we expect that students who are praised for their intelligence will have worse performance after setbacks, compared with students who are praised for their effort (Hypothesis 4). We also included a control group in this study to check the manipulation. These students received no additional praise. Because their reactions will not be influenced by praise for intelligence or praise for effort, we expect that their results will fall between those of both groups described above.

Method

Participants

Participants were 108 students (60 males, Mage = 17.20 years, SD = 1.81) at a school for Adult and Secondary Vocational Education in the southwest of the Netherlands. Students’ participation was completely voluntary, there was no selection by the researchers. All participants gave informed consent, for minors their parents gave consent as well.

Materials

Both the materials and procedure were based on the first study in the article by Mueller and Dweck (Citation1998).

Problem task

All students received three sets of 10 problems from Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices (Raven et al., Citation2004). Each correctly solved problem yielded one point. The score (0–10) for each set was calculated as the sum of the number of correctly solved problems in that set.

Achievement goals

Students’ achievement goals were measured as a nominal variable with a question on a response sheet where students could choose one out of four tasks expressing different goals (Mueller & Dweck, Citation1998). Three choices represented different variations of performance goals that focused on students’ ability: ‘Problems that are not too hard, so I do not get many wrong’, ‘Problems that are pretty easy, so I will do well’, and ‘Problems that I am pretty good at, so I can show that I am smart’. The fourth choice represented a learning goal: ‘Problems that I can learn a lot from, even if it looks like I am not that smart’. Just as in the original study by Mueller and Dweck (Citation1998) we used three performance goals and one learning goal to offset the possible preference of the student for a learning goal (Leggett, Citation1986).

Perception of the task and persistence

We used a questionnaire to ask students to respond to a number of questions that explored their enjoyment of the problems (‘Did you like to work on these tasks?’), their desire to persist in working on the problems (‘How much would you like to work on more of these tasks?’), their perception of the quality of their performance (‘How well did you do on the problems overall?’) and their perceived performance (complexity) (‘Did you find the tasks difficult?’) All of these questions were scored on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (‘not at all’) to 6 (‘very much’) (Mueller & Dweck, Citation1998).

Attribution

The attribution for their poor performance after the second set of problem task (failure task) was assessed with a circle with 60 segments, just like a clock. This circle was a replacement for the ‘disk device’ described in prior research (Diener & Dweck, Citation1980). The disk device consisted of four coloured circles that each represented an attribution. The circles can be shuffled over each other, so that the quantity of each colour corresponds to the indicated attribution. In a pilot, we tried out this disk device, but the VET students reported that they perceived this as a rather childish instrument, so we followed the recommendations by Yeager et al. (Citation2016) and developed the circle with 60 segments. Students were asked to divide the circle into four parts, each part representing an ability statement regarding their poor performance on the second set of problem task (failure task). Students could choose out of four presented statements, representing three possible explanations for their poor performance (Mueller & Dweck, Citation1998): lack of effort (‘I did not work hard enough’), lack of ability (‘I am not good enough at these problems’ and ‘I am not smart enough’), and lack of time (‘I did not have enough time’). As in previous research, two ability attributions were included to increase the perceived acceptability of this choice. The time attribution was added to take into account the limited amount of time students were allowed to work on the set of problems (Mueller & Dweck, Citation1998). The four attribution statements were scored on a scale from 0–60, with a total of 60 points for the four statements.

Procedure

The researchers visited classes and gave information about the study (‘We are conducting research to investigate in what way teachers can better support your learning’). After students had agreed to participate in the study, they were invited one by one by the experimenter to come to a separate room and were introduced to the task. The experimenter gave a brief tutorial on the tasks, as presented in .

Thereafter, the experimenter asked the participants to work on the first task: a set of 10 progressive matrices problems of moderate difficulty. The experimenter told participants that there was a limited amount of time (4 min) to work on the set of problems.

After completion or after the 4 min had passed, all participants received praise. Regardless of their score, all students received the same praise at this point: ‘Wow, that is really a high score, you solved at least 80% of the problems.’ Some students (n = 39) were praised for their intelligence after the initial praise (‘You must be smart at these problems’), some students (n = 37) were praised for their effort (‘You must have worked hard on these problems’). The remaining students (n = 32) were in the control group and did not get any additional praise. Students were randomly assigned to receive different forms of praise.

After students were praised, they had to indicate on a response sheet what kind of problems they would like to work on next. The choices represented either learning goals or performance goals, as described above. Students were asked to put the completed response sheet upside-down on the table so that the experimenter did not know the student’s goal choice. After choosing their goal, analogous to previous research, students were told that their choice would be granted if there was extra time at the end of the session, but that they first had to work on the predetermined tasks. The experimenter gave this explanation to prevent the possibility that a different choice might lead to different expectations about the difficulty and nature of the following tasks. Next, students were asked to work on the second task, a set of very difficult progressive matrices problems. After completion or after the 4 min were over, all students received the same feedback; ‘This went a lot worse, you scored less than 50% correct.’ After this negative feedback, students were asked to complete the questionnaire measuring enjoyment, their desire to persist, their perceived performance, and the perceived complexity of the problems. Furthermore, they had to divide the circle into four parts representing their attribution for poor performance on the second task. Finally, students were asked to work on the third task: a set of problems of moderate difficulty. This set provided a measure of post-failure performance.

After completing this set, all students were debriefed. Students were informed that the second set of problems was actually too difficult for them; ‘Even students from a higher level would have trouble in giving the right answers.’ Thereafter, they were told that they performed rather well on all three sets of problems. This was done to ensure that all students would leave the room with a good degree of confidence in their performance.

Results

Preliminary analyses

We conducted some preliminary analyses. First, we calculated the mean scores on the first task (M = 9.22, SD = 0.85), the second task, (M = 3.81, SD = 2.00), and the third task (M = 7.42, SD = 1.81). All scores could range from 0 to 10. Second, we examined the effect of the students’ task ability (as shown by their scores on the first set of problems) on the dependent variables (goal choice, task enjoyment, task persistence, task performance, perceived complexity, and failure attributions). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) by type of praise and initial task performance (on the first task) showed no significant interaction effects that influenced the interpretation of our findings. With a moderator analysis using the PROCESSv3.0 plugin by Hayes in IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (Hayes & Preacher, Citation2014) we examined whether task performance on the first set of problems moderated the effect of type of praise on the dependent variables (i.e. goal choice, task perception, task persistence, and failure attributions). Results indicated that task performance on the first set of problems did not moderate these effects. Therefore, we can conclude that students’ initial performance did not influence the way they reacted to the different kinds of praise.

Hypothesis 1: Students who get praised for intelligence will prefer to choose tasks that ensure good performance and will therefore choose performance goal tasks, while students who get praised for effort will see their hard work as an opportunity to learn and will therefore choose learning goal tasks.

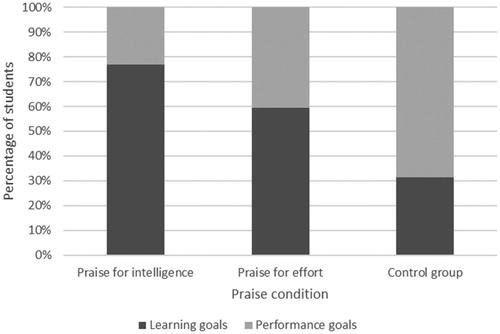

A chi-square analysis showed a significant difference in students’ goal choice after praise, χ2(2, n = 108) = 15.01, p < .001. As shown in , the majority of students who received additional praise for intelligence (76.9%) or additional praise for effort (59.5%) chose learning goals, so they preferred learning new things above looking smart.

This finding supports part of our first hypothesis, where we expected that students who received additional praise for effort would choose learning goals. However, in contrast to our first hypothesis, participants who received additional praise for intelligence were not more likely to choose the performance goal tasks. The majority of students in the control group (68.8%), who did not get any additional praise, chose performance goal tasks and hence, preferred looking smart above learning new things. This is in contrast to Mueller and Dweck’s (Citation1998) findings and to our first hypothesis, because we expected that in the control group the learning goals and performance goals would be evenly distributed.

Hypothesis 2: Students who are praised for their intelligence will attribute failure to lack of ability, whereas students who are praised for their effort, will attribute failure to (lack of) effort.

Students had to apportion their overall attribution among four attribution statements: one statement on low effort, two statements on low ability, and one statement on lack of time. The scores on the two low ability statements were averaged into one score for low ability. Using a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), statistically significant differences between conditions were found in students’ attributions for their poor performance, F(4, 208) = 2.71, p = .031, Wilks’ Λ = 0.903, ηp2 = 0.050. These differences were found in effort attributions, F(2, 105) = 2.27, p = .0423, ηp2 = 0.059, and in ability attributions, F(2, 105) = 3.72, p = .028, ηp2 = 0.066, but not in attributions related to lack of time, F(2, 105) = 1.25, p = .292, ηp2 = 0.023. A Tukey post-hoc test demonstrated that students who were praised for intelligence (Meffort attribution = 11.95, SD = 7.71) were more likely to attribute poor performance to effort compared to students who were praised for effort (Meffort attribution = 7.54, SD = 5.83), p = .012. Neither group significantly differed from the control group (Meffort attribution = 10.00, SD = 8.90). A second Tukey post-hoc test revealed that students who were praised for intelligence (Mability attribution = 13.60, SD = 6.01), were less likely to attribute poor performance to their ability compared to students who were praised for effort (Mability attribution = 16.96, SD = 6.34), p = .043. Again, neither group significantly differed from the control group (Mability attribution = 16.78, SD = 5.57). These findings are in contrast to our second hypothesis. In fact, our results showed an opposite pattern for effort attributions; VET students who received praise for intelligence attributed their lower performance to lower effort and students who received praise for effort attributed their lower performance to lower ability.

Hypothesis 3: We expect that students who are praised for their intelligence will have more negative responses such as less persistence, l perceived enjoyment, lower perceived performance, and higher perceptions of complexity after setbacks.

To test this hypothesis, we conducted a MANOVA to investigate whether the different forms of praise would have an effect on students’ post-failure task experience (i.e. enjoyment, persistence, etc.). Using Wilks’ lambda, there was no statistically significant difference among the three groups, Λ = 0.911, F(8, 204) = 1.22, p = .287, ηp2 = 0.046, ns. Therefore, our third hypothesis was rejected.

Hypothesis 4: We expect that students who are praised for their intelligence will have worse performance after setbacks, compared with students who are praised for their effort.

To test this hypothesis, we first calculated the differences among all three forms of praise on task performance (i.e. all three tasks). A one-way ANOVA revealed no statistically significant differences on the first problem set, F(2, 105) = 1.53, p = .222, η2 = 0.03, ns., on the second problem set, F(2, 105) = 0.56, p = .574, η2 = 0.01, ns and on the third problem set, F(2, 105) = 2.15, p = .121, η2 = 0.04, ns. The lack of difference in performance on the first set of problems indicates that all three groups performed equally well at the start of the experiment, which confirms a random distribution of the students. As shown in we found an overall decline in performance on the second, most difficult problem set of (failure performance) (Mdifference = −5.42, SD = 2.18). Similarly, an overall decline of performance (Mdifference = −1.81, SD = 1.95) could be observed between the first and the third set of problems.

Table 1. Performance change on sets of problem task.

A one-way ANOVA showed no statistically significant difference in performance decline from the first to the second set of problems for the three types of praise, F(2, 105) = 1.10, p = .336, η2 = 0.02, ns. This indicates that students in all three conditions reacted in a similar manner to the second most difficult set of problems, their decline in performance was similar in all three groups. With a one-way ANOVA, we revealed a significant difference in performance decline by condition, F(2, 105) = 3.24, p = .043, η2 = 0.06 between the first and third set of problems. A Tukey post-hoc test showed that students who were praised for effort had a significantly smaller decline (M = −1.30, SD = 1.76) than students in the control group (M = −2.47, SD = 2.21). But there were no differences between students who were praised for intelligence (M = −1.74, SD = 1.79) and students who were praised for effort, or between students who were praised for intelligence and students in the control group (p = .256). These findings are partly in support of our fourth hypothesis. Our expectation that students in the control group would have lower performance after setbacks when compared to students who were praised for their effort was confirmed. However, our expectations that students who were praised for intelligence would have the greatest post-setback decline in performance, was not confirmed.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effects of different kinds of praise on VET students. In line with previous studies conducted by Dweck and colleagues (Diener & Dweck, Citation1978; Diener & Dweck, Citation1980; Mueller & Dweck, Citation1998), we expected praise for intelligence to have more negative consequences for students’ goal choice and achievement when compared to praise for effort. Some of our findings supported our hypotheses, while others did not. We first discuss our findings for each hypothesis separately, followed by a general discussion.

The analysis of our first hypothesis, related to goal choice, showed that it was not the different types (intelligence or effort) of praise, but the amount of praise that affected students’ goal choice. Students in the control group, who did not receive additional praise, were more likely to choose performance goal tasks, whereas students who received additional praise (for intelligence or effort) were more likely to choose learning goal tasks. These findings are in contrast to Mueller and Dweck’s (Citation1998) findings that children who were praised for intelligence were more likely to choose performance goal tasks and children who were praised for effort were more likely to choose learning goal tasks. Apparently, a larger, more specific amount of praise in our study led to a learning goal orientation. The effect of the amount and specificity of praise instead of the content of praise can be explained by assuming that mindset cannot be easily changed (Dweck, Citation2008). If a students’ mindset is rather stable it will be more difficult to change and a stronger mindset manipulation (i.e. delivery of praise) might be necessary. Another explanation can be that the mindset of VET students is less sensitive to the effect of the interventions because they are older and are more advanced students (i.e. have experienced more years of education). Therefore, the kind of praise these students receive, will not lead to differences in goal choice. This is in line with previous findings where mindset interventions did not have the intended effect, possibly due to the age of the students (Glerum et al., Citation2018; Orosz et al., Citation2017).

For our second hypothesis, we expected that the way students used ability and effort attributions to justify their lower performance would be related to the praise they had received. Our findings are in contrast to previous research where students who received praise for intelligence attributed their lower performance to lower ability and students who received praise for effort attributed their lower performance to the lower effort (Mueller & Dweck, Citation1998). Surprisingly, our students who received praise for intelligence attributed their lower performance to lower effort and students who received praise for effort attributed their lower performance to lower ability. It actually remains unclear why our students showed a contrasting pattern of attributions. Although it seems to be a counterintuitive pattern, it could be that students who were just praised for intelligence would have a hard time explaining failures as due to lack of intelligence and would have to fall back on lack of effort as an explanation, and vice versa for those just praised for effort. But, in line with our first hypothesis, if there are no differences in the type of praise the students received, the opposite findings can be based on coincidence, or, due to the missing effect of praise on attributions. In this study, we investigated the different effects of praise on holding an entity or incremental belief about intelligence. The model of the entity and incremental beliefs has been extended to include several other characteristics, such as motivation, morality, and personality (Dweck, Chiu, & Hong, Citation1995). They found the same effect of the entity and incremental beliefs about these characteristics as for intelligence. However, a recent study with adults by Preißinger and Schoen (Citation2018) did not find systematic evidence for effects of the entity or incremental beliefs about personality on attributions. Further research could examine if the same applies to the different kinds of praise as far as attributions related to intelligence.

With regard to the effects of types of praise on students’ post-failure task experience (Hypothesis 3), our findings were again not in support of our expectations. Similar to Hypothesis 1, we again did not find a difference between the students who were praised for intelligence and those who were praised for effort. Although students in the control group showed a statistically significant difference in goal choice relative to the praise for effort and intelligence groups, the three groups did not have statistically significant differences in their post-failure task experiences. It seems that type of praise and post-failure task experience are not associated, which also corresponds to the explanation of our first hypothesis. Apparently, the different types of praise do not influence the post-failure task experiences of VET students.

Our fourth hypothesis was partially confirmed. Confirming our hypothesis and in line with previous research, students who were praised for effort had a significantly lower decline in performance on the post-setback problem tasks than students who were in the control group (e.g. Mueller & Dweck, Citation1998). Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find a significant difference in decline in performance on the third problem task between students who were praised for effort and those who were praised for intelligence, nor for students who were praised for intelligence and students in the control group. The (lack of) relationship between different kinds of praise and post-failure task performance is somewhat bewildering. However, it is in line with previous studies that did not find a clear relation between mindset and academic performance (Bahník & Vranka, Citation2017; Bates, Citation2015; Chivers, Citation2017; Glerum et al., Citation2018; Orosz et al., Citation2017).

Overall, in our present study, where we went back to the origins of mindset theory and investigated the effects of different kinds of praise, we did not find substantiation of the study by Mueller and Dweck (Citation1998) regarding the effect of praise. Although we found some similarities, none of our hypotheses could be fully confirmed. For the parts of our hypotheses that were confirmed, some limitations must be acknowledged due to the small effect sizes we found. All analyses of variance yielded only small effects (all ηp2 < 0.1 and all η2 < 0.1). In their review, Yeager and Walton (Citation2011) addressed possible explanations for the different effects of mindset interventions in experimental and in classroom settings. Mindset interventions with positive effects in experimental settings can be disturbed in classroom settings by unmeasured factors such as the way teachers implement the intervention. This suppresses the outcomes. Hence, it is plausible that the small effects we found would fade out if this intervention were implemented in a classroom setting, in line with one of our previous studies (Glerum et al., Citation2018). Our findings with VET students and their performance on problem tasks are in line with the recent meta-analysis on the mindset that showed only weak associations between mindset and academic achievement (Sisk et al., Citation2018). The average effect size reported in their meta-analysis of the effects of mindset interventions on academic performance was lower than the average effect size for the impact of effective educational interventions on academic performance (Hattie, Citation2008).

In the present study we empirically investigated one of Dweck’s explanations for null findings, namely that the lack of effects of mindset on academic performance could be ascribed to suboptimal enactment of the intervention. The results of this study seem to point out that the problem is not so much in carefully duplicating the interventions, but more in the reproducibility of the effects of praise on performance. Admittedly, differences exist between our participants and those in the study by Mueller and Dweck (Citation1998). First, our participants (Mage = 17.20 years) are ∼7 years older. However, despite this difference, age is generally not a contributing factor in mindset outcomes (Burnette et al., Citation2012; Sisk et al., Citation2018). Second, compared to the study by Mueller and Dweck (Citation1998) and despite careful piloting beforehand, the scores of our participants on the first set of Raven’s problems were substantially higher, which can be explained by the age of our students. However, this does not have to be problematic, because there was still a sharp drop in performance from set 1 to set 3 (larger than the drop that was found by Mueller & Dweck, Citation1998) and a substantial improvement from the second set to the third set of Raven’s problems. Because we had the same pattern of failure and post-failure performance, the problem scores were not necessarily determinative for our results. Other possible differences between our study and theirs can be found in the national and cultural contexts and the educational context (elementary school versus VET). For this last factor, we expected the opposite of what we saw because VET students were expected to benefit from mindset interventions; in general, they have had a difficult school career in both elementary school and primary vocational education. The main limitation of our present study, however, is that we did not check whether our students really had experienced difficulties or were underperforming in their prior education.

In their recent meta-analyses, Sisk et al. (Citation2018) suggested that a growth mindset is not very important for academic achievement, except for students at risk and students with low socioeconomic status (SES). Although we did not explicitly measure SES, we have no indication that our sample consisted of more students with a lower than average SES. The number of dropouts is higher in Dutch vocational education than in the general education track (https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/vsv). Therefore, we expected positive effects of praise for effort with our participants. But, although our students may have experienced difficulties or showed underperformance, we do not know if our students were really ‘at risk’. Further research with VET students at risk or with low SES can clarify whether or not the different types of praise do influence these students’ performance.

Future directions and conclusions

Further investigations of potential aspects that influence the effects of praise and mindset on academic performance need to provide more insight into why the different types of praise and mindset interventions are effective in one situation and not in another situation. As we did in a VET context, replicating the study by Mueller and Dweck (Citation1998) in other educational contexts can add greater insight into the applicability of mindset interventions. In line with Dweck (Citation2017b), we must conclude that it remains unclear why not all students benefit from mindset interventions. This study gave the first indication, but not a complete answer to this question. We found that one of the basic assumptions of mindset theory (different kinds of praise leads to different performances) does not apply to all VET students. This can be a confirmation of the findings by Sisk et al. (Citation2018), who found that mindset is not very important for academic achievement. So, although mindset interventions are cheap and easy to implement, it is necessary to first consider whether these interventions are effective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Aronson, J., Fried, C., & Good, C. (2002). Reducing the effects of stereotype threat on African American college students by shaping theories of intelligence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 113–125. doi:10.1006/jestp.2001.1491

- Bahník, Š., & Vranka, M. A. (2017). Growth mindset is not associated with scholastic aptitude in a large sample of university applicants. Personality and Individual Differences, 117, 139–143. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.05.046

- Bates, T. (2015, September). Testing alternatives to trait-IQ: Dweck’s Mindset, Woolley’s Emotional Collective; and Baumeister’s Depleted Will models. Paper presented at the 15th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Intelligence Research, Albuquerque, USA.

- Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78, 246–263. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00995.x

- Burnette, J. L., O’Boyle, E. H., VanEpps, E. M., Pollack, J. M., & Finkel, E. J. (2012). Mind-sets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 139, 655–701. doi:10.1037/a0029531

- Chivers, T. (2017, January 14). A mindset “revolution” sweeping Britain’s classrooms may be based on shaky science. BuzzFeed News. Retrieved from https://www.buzzfeed.com/tomchivers/what-is-your-mindset?utm_term=.glKevaA3wb#.ioX9mKraDG

- Davis, J. L., Burnette, J. L., Allison, S. T., & Stone, H. (2011). Against the odds: Academic underdogs benefit from incremental theories. Social Psychology of Education, 14, 331–346. doi:10.1007/s11218-010-9147-6

- Diener, C. I., & Dweck, C. S. (1978). An analysis of learned helplessness: Continuous changes in performance, strategy, and achievement cognitions following failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36, 451–462. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.36.5.451

- Diener, C. I., & Dweck, C. S. (1980). An analysis of learned helplessness: II. The processing of success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 940–952. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.39.5.940

- Donohoe, C., Topping, K., & Hannah, E. (2012). The impact of an online intervention (Brainology) on the mindset and resiliency of secondary school pupils: A preliminary mixed methods study. Educational Psychology, 32, 641–655. doi:10.1080/01443410.2012.675646

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY: Random House Publishing Group.

- Dweck, C. S. (2008). Can personality be changed? The role of beliefs in personality and change. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 391–394. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00612.x

- Dweck, C. S. (2017a, September 22). Carol Dweck revisits the “Growth Mindset”. Education Week. Retrieved from http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2015/09/23/carol-dweck-revisits-the-growth-mindset.html?cmp=eml-eb-wnbk1.3

- Dweck, C. S. (2017b). From needs to goals and representations: Foundations for a unified theory of motivation, personality, and development. Psychological Review, 124, 689–719. doi:10.1037/rev0000082

- Dweck, C. S. (2017c). The journey to children’s mindsets-and beyond. Child Development Perspectives, 11, 139–144. doi:10.1111/cdep.12225

- Dweck, C. S. (2018, June 26). Growth mindset interventions yield impressive results. The Conversation. Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/growth-mindset-interventions-yield-impressive-results-97423

- Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C., & Hong, Y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A world from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 6, 267–285. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0604_1

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256–273. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

- Glerum, J., Loyens, S. M. M., & Rikers, R. M. J. P. (2018). Is an online mindset intervention effective in vocational education? Interactive Learning Environments. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/10494820.2018.1552877

- Gunderson, E. A., Gripshover, S. J., Romero, C., Dweck, C. S., Goldin-Meadow, S., & Levine, S. C. (2013). Parent praise to 1- to 3-year-olds predicts children’s motivational frameworks 5 years later. Child Development, 84, 1526–1541. doi:10.1111/cdev.12064

- Hattie, J. (2008). Visible Learning. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203887332

- Hattie, J. (2017, May 29). Misinterpreting the growth mindset: Why we’re doing students a disservice [Guest Web log post - Finding common ground]. Education Week. Retrieved from http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/finding_common_ground/2017/06/misinterpreting_the_growth_mindset_why_were_doing_students_a_disservice.html

- Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67, 451–470. doi:10.1111/bmsp.12028

- Inspectorate of Education. (2014). De Staat van het Onderwijs: Onderwijsverslag 2012/2013 (Rapport). The Netherlands: Inspectie van het onderwijs. Retrieved from https://www.onderwijsinspectie.nl/documenten/publicaties/2014/04/16/de-staat-van-het-onderwijs-onderwijsverslag-2012-2013

- Leggett, E. L. (1986). Individual differences in effort/ability inference rules and goals: Implications for causual judgements (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

- Mueller, C. M., & Dweck, C. S. (1998). Praise for intelligence can undermine children’s motivation and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 33–52. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.75.1.33

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2016). Netherlands 2016: Foundations for the Future. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

- Orosz, G., Péter-Szarka, S., Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., & Berger, R. (2017). How not to do a mindset intervention: Learning from a mindset intervention among students with good grades. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 311. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00311

- Paunesku, D., Walton, G. M., Romero, C., Smith, E. N., Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2015). Mind-set interventions are a scalable treatment for academic underachievement. Psychological Science, 26, 784–93. doi:10.1177/0956797615571017

- Pomerantz, E. M., & Kempner, S. G. (2013). Mothers’ daily person and process praise: Implications for children’s theory of intelligence and motivation. Developmental Psychology, 49, 2040–2046. doi:10.1037/a0031840

- Preißinger, M., & Schoen, H. (2018). Entity and incremental theory of personality: Revisiting the validity of indicators. Personality and Individual Differences, 130, 21–25. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.03.042

- Rattan, A., Good, C., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). “It’s ok — Not everyone can be good at math”: Instructors with an entity theory comfort (and demotivate) students. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 731–737. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.12.012

- Rattan, A., Savani, K., Chugh, D., & Dweck, C. S. (2015). Leveraging mindsets to promote academic achievement: Policy recommendations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 721–726. doi:10.1177/1745691615599383

- Raven, J., Raven, J. C., & Court, J. H. (2004). Standard progressive matrices. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment.

- Sisk, V. F., Burgoyne, A. P., Sun, J., Butler, J. L., & Macnamara, B. N. (2018). To what extent and under which circumstances are growth mind-sets important to academic achievement? Two meta-analyses. Psychological Science, 29, 549–579. doi:10.1177/0956797617739704

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47, 302–314. doi:10.1080/00461520.2012.722805

- Yeager, D. S., Romero, C., Paunesku, D., Hulleman, C. S., Schneider, B., Hinojosa, C., … Dweck, C. S. (2016). Using design thinking to improve psychological interventions: The case of the growth mindset during the transition to high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108, 374–391. doi:10.1037/edu0000098

- Yeager, D. S., & Walton, G. M. (2011). Social-psychological interventions in education: they’re not magic. Review of Educational Research, 81, 267–301. doi:10.3102/0034654311405999