Abstract

We examined university students’ experiences of remote teaching and learning, how the experiences are associated with well-being, and whether those associations differ according to motivation. Using latent variable modelling, we classified Finnish university students (N = 2686) based on their expectancy-value-cost profiles, compared latent means, and tested whether the predictions varied across profiles. Six expectancy-value-cost profiles were identified: moderately motivated, utility-oriented, disengaged, indifferent, positively ambitious, and struggling ambitious. Overall, positively ambitious students seemed most adaptive in terms of their study experiences and well-being. Similarly across the profiles, engagement was predicted positively by the evaluation of remote teaching and negatively by experienced strain, exhaustion positively by the evaluation of teaching and strain, and depressive symptoms positively by strain and sense of alienation. Findings suggest that subjective experiences of remote teaching and learning during the pandemic contribute to students’ well-being in unique ways and that distinct motivational mindsets may buffer against the negative outcomes.

Introduction

Higher education institutes were forced to rapidly transition to online teaching due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which drastically influenced teaching and study practices and students’ possibilities to interact with their peers and the academic community. As universities are currently reforming their practices and even the future of higher education, it is vital to understand how students experience these immense changes, and what kind of impact they have on students’ motivation and well-being. In this study, we investigated how Finnish university students experience the transition to remote teaching and learning, how those experiences are moderated by motivation, and how they are associated with psychological well-being.

Students’ study-related experiences during the pandemic

Despite some generally positive experiences with diverse online learning environments (see Ebner & Gegenfurtner, Citation2019; Means et al., Citation2013), the sudden transition to remote teaching and learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic challenged both teachers and students. Many teachers were unfamiliar with the digital teaching environments and technologies, had difficulties in converting their courses to the online form, and struggled with managing the pedagogical practices for remote teaching, maintaining interaction, and promoting peer support (e.g. König et al., Citation2020). Concurrently, students had to adapt quickly to studying more independently, whilst lacking the immediate support from face-to-face classes, and many struggled with studying from home (e.g. Ewing & Cooper, Citation2021).

Remote teaching and learning, and the increased social isolation, also drastically changed peer interactions, thus likely promoting students’ sense of alienation from others. Such a negative emotional response to perceived social isolation (Hawkley & Cacioppo, Citation2010), has been found to be predictive of anxiety, stress, and depression (Richardson et al., Citation2017). Initial studies among university students suggest this to be the case during the pandemic as well; evidence has shown a decrease in mental well-being and an increase in stress, loneliness, anxiety, and depressive symptoms (Elmer et al., Citation2020; Meda et al., Citation2021; Savage et al., Citation2020). However, while the negative impact of the pandemic is undeniable, we should not neglect potential positive experiences either (Lee et al., Citation2021). For example, Elmer et al. (Citation2020) found a decrease in competition among the students, which may benefit particularly those who do not thrive in a competitive environment.

The above implies individual differences in how the drastic changes are perceived and coped with. These differences may be partly due to the variance in motivational mindsets. For example, Daumiller et al. (Citation2021) found university teachers’ achievement goals to predict whether they perceived the transition to remote teaching as a positive challenge or threatening. Teachers’ learning-focussed goals were associated with the view of positive challenge, while performance- and avoidance-focussed goals with the view of threat, which, in turn, predicted burnout symptoms. Interestingly, these different views were also translated into student evaluations, so that teachers perceiving the situation as a threat received worse ratings. These findings imply that just like teachers, also differently motivated students would seem likely to differ in how they perceive transition. Thus, the transition could be experienced more positively by students who emphasise high success expectancies and view their studies as interesting, meaningful, and useful, as these students are likely to strive for gaining competence. In contrast, the transition could be experienced negatively by students who see studies as costly and express lower expectancies.

Students’ psychological well-being

Although studies have demonstrated changes in students’ well-being due to the abruptions caused by the pandemic, the links between subjective experiences of the transition and well-being are still scarcely investigated. Some evidence has, however, suggested an association between perceived study conditions and depressive symptoms during the pandemic (Matos Fialho et al., Citation2021).

The transition to remote teaching and learning has also blurred the lines between studying and personal life, which likely results in a stronger interconnection between academic and general well-being. Derived from the demands-resources models (e.g. Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, Citation2014), engagement and emotional exhaustion represent important positive and negative aspects of academic well-being that are pertinent in the demanding context of higher education (Salmela-Aro & Read, Citation2017). Engagement refers to students’ enthusiasm towards, and being absorbed in, studying (Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, Citation2012), while exhaustion, one of the core dimensions of burnout, reflects a severe loss of physical and mental energy (Schaufeli et al., Citation2020). These two widely studied constructs have been shown to be negatively associated with each other and linked with important educational outcomes, such as achievement, aspirations, and attainment (e.g. Fiorilli et al., Citation2017; Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, Citation2012; Tuominen-Soini et al., Citation2012; Tuominen-Soini & Salmela-Aro, Citation2014), and here, taken to reflect both the eagerness and the fatigue experienced in studies during the pandemic.

Depressive symptoms, in contrast, reflect students’ psychological well-being beyond studies, although connected with academic performance (Hysenbegasi et al., Citation2005) and motivation (Watt et al., Citation2019). Depressive symptoms are characterised by a loss of self-esteem and incentive (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995), and are also associated with social isolation (Elmer & Stadtfeld, Citation2020). Thus, taking into account the connections with diminished engagement and elevated exhaustion, the combined effect of these constructs on achievement (Fiorilli et al., Citation2017), and the associations with social isolation, investigating depressive symptoms together with engagement and exhaustion seems highly relevant in the present context.

Students’ motivation: the expectancy-value-cost framework

Students’ well-being is also associated with their motivation (e.g. Tuominen et al., Citation2020; Tuominen-Soini et al., Citation2012). This connection is partly inherent in one of the most prominent approaches to student motivation, the expectancy-value theory (Eccles et al., Citation1983; Wigfield & Eccles, Citation2020), which incorporates three types of motivational constructs. Expectancies refer to subjective beliefs about how well one will succeed, while value can be divided into intrinsic value (the enjoyment derived from an activity or interest in a task), attainment value (personal importance of succeeding in a task), and utility value (perceived usefulness of success in a task). Cost, in contrast, describes the perceived negative consequences of engaging in a task. Recent advancements in the conceptualisation and operationalisation of cost have resulted in facets that resemble measures of well-being. For example, the emotional cost has been measured with items referring to perceived exhaustion and stress associated with a subject (e.g. Gaspard et al., Citation2015). Although it would seem sensible to differentiate cost from well-being, the definition of cost as the complementary counterpart of effort investment nevertheless discloses its motivational relevance, and also suggests that a relative emphasis on the different components of expectancy, value, and cost might result in distinct motivational configurations with implications for other academic and educational outcomes, including well-being.

Indeed, Watt et al. (Citation2019) identified three expectancy-value-cost profiles, positively engaged (high on expectancy, intrinsic and utility values, low on costs), disengaged (low on expectancy and intrinsic value, high on utility value and costs), and struggling ambitious (high on all) that all differently predicted well-being. Struggling ambitious students scored highest on depression, anxiety, and stress, while positively engaged showed the most adaptive well-being. Thus, given the relevance of expectancies, values, and cost in predicting students’ commitment, engagement, and performance in academic settings (e.g. Gaspard et al., Citation2019; Schnettler et al., Citation2020), as well as its connection with well-being, it seems reasonable to assume that students with different expectancy-value-cost profiles also differ in how they experience the transition to remote teaching and learning, and how it influenced their well-being.

This study expands on previous research on expectancy-value-cost motivation in higher education by examining through a person-oriented approach how differently motivated Finnish university students experienced the transition to remote teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, and how those experiences were linked with their psychological well-being.

Present study

In this study, we explored the patterning of students’ expectancies, values, and costs, as this approach provides a way to acknowledge students’ relative emphasis on the different key motivational constructs, and thereby to understand better the connections between motivation and other educationally relevant outcomes. Students’ experiences of remote teaching and learning were addressed in terms of how they evaluated the transition to remote teaching, how taxing they experienced the transition to be, and how the situation influenced their social connections. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of how these experiences contributed to students’ well-being, we focussed on both positive (engagement) and negative (exhaustion) aspects of academic well-being and general psychological well-being (depressive symptoms). Our research questions were:

What kind of expectancy-value-cost profiles can be identified among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic?

How do the profiles differ in terms of remote teaching and learning experiences (evaluation of remote teaching, strain of remote learning, and sense of alienation) and psychological well-being (engagement, exhaustion, and depressive symptoms)?

How do students’ remote teaching and learning experiences predict concurrent psychological well-being?

Do the associations between remote teaching and learning experiences and well-being vary as a function of students’ motivational profiles?

Based on theoretical considerations and prior research (Perez et al., Citation2019; Watt et al., Citation2019), we expected to identify at least three kinds of expectancy-value-cost profiles: profiles with high values and low costs, profiles with relatively high values and costs, and profiles low on intrinsic value but high on utility value and costs.

We expected the profiles to differ in remote teaching and learning experiences. Profiles with high values and low costs were expected to show more positive experiences (higher evaluations of teaching, lower strain, and sense of alienation), whereas profiles with both high values and costs were expected to show more mixed experiences (relatively high evaluations of teaching, but high strain and moderate sense of alienation). Profiles with low intrinsic and high utility and cost were expected to report the most negative experiences (low evaluations of teaching, relatively high strain, and sense of alienation).

We further expected the profiles to differ in terms of well-being. Mainly drawing from Watt et al. (Citation2019) and similar studies combining achievement goal and expectancy-value theories (Tuominen et al., Citation2020), profiles with high values and low costs were expected to demonstrate the most adaptive well-being (high engagement, low exhaustion, and depressive symptoms), profiles with both high values and costs to demonstrate both adaptive and maladaptive well-being (high engagement but high exhaustion and depressive symptoms), and profiles with low intrinsic and high utility and cost to demonstrate moderate well-being (mediocre engagement, mediocre exhaustion, and high depressive symptoms).

Based on a study investigating the associations between perceived study conditions and depressive symptoms (Matos Fialho et al., Citation2021), and some indirect evidence of students’ well-being during the pandemic (Elmer et al., Citation2020; Larcombe et al., Citation2022), we expected evaluations of remote teaching to predict engagement positively and exhaustion and depressive symptoms negatively, perceived strain to predict engagement negatively and exhaustion and depressive symptoms positively, and sense of alienation to predict exhaustion and depressive symptoms. However, we did not have any grounds to assume the predictions, and hence the processes underlying the expected effects, to vary across the profiles.

Methods

Participants and procedure

In Finland, higher education that leads to a degree is tuition-free. Students are selected for the university based on the national matriculation examination or the university’s entrance exam. Competition is rather fierce, as only one-third of the students are admitted (OECD, Citation2019).

In March 2020, following the relatively strict national policy, universities in Finland shifted to remote teaching, and this was continued throughout the academic year 2020–2021. Therefore, at the time of the data collection, December 2020–January 2021, the students had not participated in face-to-face teaching in 9–10 months. Note, however, that, compared to many other countries, the readiness and resources for remote teaching were rather high already before the pandemic (EDUFI, Citation2021), and online courses were quite extensively implemented.

A total of 2686 students from three universities in Southern, Western, and Eastern Finland voluntarily participated in the study. On average, the students were 26.45 years old (SD = 7.2), 75% of them were female, and 21% were male. The students were from different years of university studies (1st = 27%, 2nd = 19%, 3rd = 16%, 4th = 15%, 5th = 12%, 6th or more = 11%) and varied fields (e.g. Science = 20%, Arts and humanities = 16%, Educational sciences = 15%, Medical sciences = 15%, Social sciences = 13%).

The data collection followed the ethical guidelines of the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity and the given universities and complied with the GDPR requirements within the EU. All data were handled anonymously and confidentially.

Measures

Expectancy-value-cost motivation

Students’ expectancies were measured with three items (e.g. ‘I expect to do well in my studies’) drawn from Bong (Citation2008; also Jiang et al., Citation2018). Students’ values and costs were assessed by utilising an instrument by Gaspard et al. (Citation2015). Here, we measured intrinsic value (e.g. ‘I simply like my studies’), importance of achievement (e.g. ‘Performing well in my studies is important to me’), personal importance (e.g. ‘The subject matter of my studies is meaningful to me’), utility for job (e.g. ‘Subject knowledge of my studies will be useful for my future career’), and effort (e.g. ‘Doing well in my studies requires more effort than I want to put into it’) and opportunity (e.g. ‘To do well in my studies requires that I give up other activities I enjoy’) cost facets. Each subfacet was measured with three items on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (completely true). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the data showed a good fit after minor modifications (i.e. three pairs of similarly worded items were let to correlate), χ2 (165) = 1636.574, p < .001, CFI = .950, RMSEA = .057, SRMR = .063.

Remote teaching and learning experiences

Drawn from a survey included in a national evaluation of upper secondary students’ experiences of remote teaching and learning during the pandemic (The Union of Upper Secondary School Students in Finland, n.d.), we measured evaluations of remote teaching (‘the transition to remote teaching went smoothly’, ‘teachers have had adequate resources to implement remote teaching’, and ‘remote teaching has offered versatile enough support for my study habits’) and strain of remote learning (‘I find remote teaching and independent studying emotionally taxing’, ‘I need more support for studying than I am getting’, and ‘I have difficulties combining studies and the rest of my life’). Sense of alienation was measured with three items (e.g. ‘I feel isolated from others’) from the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., Citation1980). The guiding question for perceptions of remote teaching was ‘All in all, the corona pandemic has caused big changes in how studying has been arranged. What do you think of them?’, and for the associated experiences of strain and sense of alienation ‘How have you experienced the situation from the point of view of studying?’. The scale ranged from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (completely true).

Psychological well-being

The engagement was measured with three items (e.g. ‘When studying, I am full of energy’) from the Schoolwork Engagement Inventory (EDA; Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, Citation2012), exhaustion with three items (e.g. ‘While studying, I feel mentally exhausted’) from the short version of Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT-12; Schaufeli et al., Citation2020), and depressive symptoms with four items (e.g. ‘I felt down-hearted and blue’) from the depression subscale of DASS21 (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995). The scale ranged from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (completely true). A joint CFA on the measures of remote teaching and learning experiences and well-being indicated a good fit to the data after some minor modifications (i.e. error covariances between three pairs of items were freed), χ2 (134) = 1238.277, p < .001, CFI = .958, RMSEA = .054, SRMR = .036.

Descriptive statistics and correlations for all variables are shown in and factor loadings are in the Supplementary Material.

Table 1. Bivariate correlations, descriptive statistics, and internal consistencies for all variables.

Data analyses

The study combined variable- and person-oriented analyses within the latent variable modelling framework to describe both the differences and similarities across groups of individuals (i.e. differently motivated students) and the relations between constructs (i.e. remote teaching and learning experiences and well-being) in accordance with the research aims. First, students were classified into distinct motivational groups based on the expectancy-value-cost measures using latent class clustering (LCCA). Then, after ensuring measurement equivalence across the identified profiles, latent means and predictions of remote teaching and learning experiences on well-being were compared between the groups using multi-group structural equation modelling (SEM).

We used model-based LCCA, which seeks to identify meaningful patterns representing the mixture of underlying probability distributions in the data, and uses various statistical criteria for deciding the number of classes that fit the data best (Vermunt & Magidson, Citation2002). For this, we used Classification Log-likelihood (CL), Entropy, Classification Likelihood Criterion (CLC), Approximate Weight of Evidence (AWE), and a version of the Integrated Classification Likelihood called ICL-BIC, along with standard and entropy R2, as implemented in the Latent GOLD 5.1 statistics software (Vermunt & Magidson, Citation2005). CL and Entropy are quantities needed to compute the other three. CLC indicates how well a model performs in terms of fit and classification performance. The AWE and ICL-BIC statistics add a third dimension to the information criteria described above; they weigh fit, parsimony, and the performance of the classification (Vermunt & Magidson, Citation2016). Generally, the smaller the estimate, the better the fit of the model, except for the indices of R2, where a higher proportion represents a better explanation. The classification was followed by a series of ANOVAs to examine group differences in the clustering variables.

In all SEM models, maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard error estimation (MLR) as implemented in the Mplus statistics software (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2017, Version 8.5) was used to obtain robust estimates with missing data. For evaluating model fit, we used the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) with respective cut-off values of ≥.90, <.08, and <.08 for adequate fit (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999), along with the chi-square statistics.

Measurement invariance across the groups was tested in a stepwise manner by increasingly adding restrictions to the model (see Supplementary Material). Given a sufficient level of measurement invariance, latent means across the groups were compared by alternately fixing the means of one group to zero and estimating the latent means of the other groups freely. Finally, a structural model was specified where the latent factors representing well-being were regressed on the latent factors representing remote teaching and learning experiences, and the equality of predictive relations across the groups was assessed by imposing restrictions on the structural parameters. Model fit was evaluated as described above.

Results

Expectancy-value-cost profiles

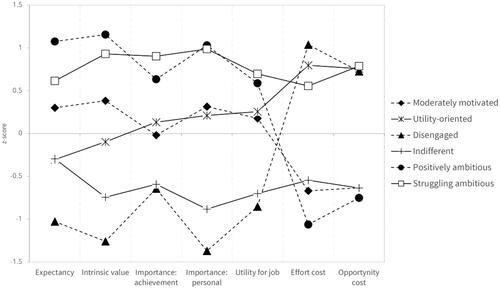

To answer the first research question, we examined what kinds of expectancy-value-cost profiles can be identified among the students. Virtually all statistical criteria from a series of LCCAs supported the six-class solution (see ). As the group sizes were reasonable, and profiles qualitatively informative and theoretically meaningful, we extracted six groups and labelled them according to the mean score profiles: moderately motivated, utility-oriented, disengaged, indifferent, positively ambitious, and struggling ambitious (see ).

Figure 1. Students’ standardised mean scores on expectancy-value-cost scales as a function of a group membership.

Table 2. Model fit and information criteria values for different cluster solutions.

The six identified groups differed significantly on all expectancy-value-cost variables with explained variance ranging from 25 to 68% (). Moderately motivated students (25%) scored relatively high on expectancy and values and low on costs. Utility-oriented students (22%) emphasised the utility value and scored relatively high also on personal importance and the importance of achievement. This group reported moderate expectancy and intrinsic value, and relatively high costs. Disengaged students (16%) scored relatively low on expectancy and values and reported rather high costs. Indifferent students (15%) reported moderate expectancy and values, and rather low costs. Positively ambitious students (13%) reported high expectancy and values, and low costs. Finally, struggling ambitious students (9%) reported both high expectancy and values and high costs.

Table 3. Group differences in expectancies, values, and costs.

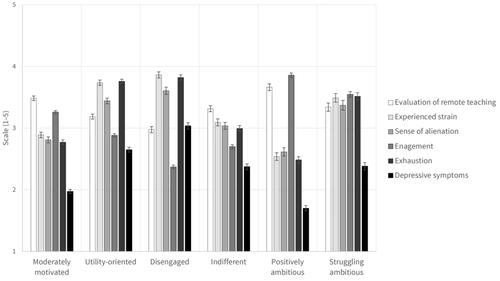

Group differences in remote teaching and learning experiences and psychological well-being

Tests of measurement invariance indicated sufficient invariance across groups (see Supplementary Material), thus enabling a valid comparison of latent means across the groups. The results showed positive evaluations of teaching to be rather high in the positively ambitious and moderately motivated students, and lowest in the disengaged group ( and ). The utility-oriented and disengaged students scored the highest and the positively ambitious the lowest in perceived strain. Sense of alienation was rather high in the utility-oriented, disengaged, and struggling ambitious students, and quite low in moderately motivated and positively ambitious students.

Figure 2. Students’ mean scores in remote teaching and learning experiences and psychological well-being.

Note. For the purposes of illustration, group differences are depicted using composite score means.

Table 4. Standardised latent mean differences in remote teaching and learning experiences and psychological well-being between expectancy-value-cost groups.

The engagement was highest in the positively ambitious and struggling ambitious students and lowest in the disengaged and indifferent students, whereas exhaustion was highest in the utility-oriented and disengaged groups, and lowest in the positively ambitious and moderately motivated students. The disengaged students also reported the most depressive symptoms, while positively ambitious students were the least.

Predictive relations between remote teaching and learning experiences and well-being

To see whether the predictive relations varied between the groups, we constrained the effects to be equal between groups. Since the resulting model fit the data well, χ2 (999) = 2258.16, p < .001, CFI = .940, RMSEA = .053, SRMR = .072, and was no worse than a model with freely estimated predictions, χ2 (954) = 2197.15, p < .001, CFI = .941, RMSEA = .054, SRMR = .062; Δχ2 (45) = 563.62, p = .035; ΔCFI = −.001; ΔRMSEA = .001; ΔSRMR = .010, we concluded the predictions to be similar across the groups. An inspection of significant effects () showed engagement to be positively predicted by evaluations of teaching and negatively by experienced strain, exhaustion to be positively predicted by strain and evaluation of teaching. Depressive symptoms were positively predicted by strain and a sense of alienation. The explained variances were around 26% for engagement, 42% for exhaustion, and 33% for depressive symptoms.

Table 5. Standardised effects of remote teaching and learning experiences on well-being.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated how Finnish university students with different motivational profiles experienced the transition to remote teaching and learning, and how these experiences contributed to students’ well-being. We identified six different motivational profiles that also differed in their experiences and well-being. We found that the remote teaching and learning experiences predicted well-being in distinct ways. Yet, the predictions were identical across the groups.

Expectancy-value-cost profiles, remote teaching and learning experiences, and well-being

As hypothesised, we identified a group high on values and low on costs (positively ambitious), a group high on both values and costs (struggling ambitious), and a group low on intrinsic value but high on utility value and costs (utility-oriented). Additionally, we found a profile with moderately high values and low costs (moderately motivated), a profile low on values and high on costs (disengaged), and a profile with moderate values and rather low costs (indifferent).

The positively ambitious and struggling ambitious students both demonstrated high expectancy, and viewed their studies as interesting, meaningful, and useful but differed significantly in their emphasis on costs. The positively ambitious students did not perceive studying as costly, whereas the struggling ambitious students perceived their studies as energy-draining and requiring giving up other activities. The differences between these groups are similar to those found in the Watt et al. (Citation2019) study, where struggling ambitious students, compared to positively engaged students, reported higher costs along with inferior psychological well-being. Also, these findings resemble the differences between mastery- and success-oriented students; the former displaying low costs and adaptive academic well-being, and the latter characterised by elevated costs and high levels of both positive and negative well-being (Tuominen et al., Citation2020).

Two profiles demonstrated moderate values. The moderately motivated and the utility-oriented students seemed to consider their studies as rather meaningful and valuable in terms of their future careers. However, the moderately motivated found their studies somewhat more interesting, less costly, and felt more efficacious. The moderately motivated students also resembled the positively motivated profile identified by Watt et al. (Citation2019) and showed slightly lower mean levels of expectancies and values and higher costs than the otherwise similar positively ambitious group. Overall, the utility-oriented profile demonstrated more extrinsic motivation, and as expected, felt remote learning as strenuous, similarly to the disengaged group identified by Watt et al. (Citation2019). Consequently, compared to the utility-oriented students, the moderately motivated students reported stronger engagement and lower exhaustion and depressive symptoms.

Both the indifferent and disengaged students seemed to struggle in finding interest and meaning in their studies. Like previous groups, these profiles differed in costs; compared to indifferent students, who were relatively low on all motivation variables, the disengaged students emphasised high costs, and thus demonstrated overall the most maladaptive motivational pattern. This group resembles the avoidance-oriented profile identified in previous achievement goal orientation research (e.g. Tuominen et al., Citation2020; Tuominen-Soini et al., Citation2012), the weakly engaged in engagement research (Korhonen et al., Citation2017), and the disengaged group in the study by Watt et al. (Citation2019). The disengaged group was also high in strain and sense of alienation, which was further reflected in their higher exhaustion and depressive symptoms.

Overall, the identified profiles somewhat overlapped with those identified in previous studies (Perez et al., Citation2019; Watt et al., Citation2019) but there were also some differences. For example, there was a higher variation in the raw scores between the profiles in the study by Watt et al. (Citation2019). As concluded by Perez et al. (Citation2019), university students have been self-selected into their studies and, thus, may be typically more motivated. Here, the generally rather high scores in motivation could particularly reflect the nature of the Finnish university context, where the admitted students have applied for their chosen major subject and received a place through very selective admissions. Also, it must be noted that the variables included in the prior studies have slightly differed and thus the profiles are not directly comparable.

Taken together, the positively ambitious students seemed to have the most adaptive overall profile, and the disengaged students were the most maladaptive. The cost was clearly a significant factor as all students, who perceived their studies as costly, seemed to have some unfavourable concomitants of their motivational strivings; whether it was strain and exhaustion experienced by the utility-oriented and the struggling ambitious students or the strain and vulnerability to emotional distress expressed by the disengaged students. For these students, the social aspect of studying may be especially crucial, as they also demonstrated a rather high sense of alienation. These findings further demonstrate how the person-oriented approach can enable identifying qualitative differences in students’ motivational patterns and their implications (see Niemivirta et al., Citation2019).

Remote teaching and learning experiences and students’ well-being during the pandemic

Our findings demonstrated the evaluations of remote teaching to be positively predictive of engagement and, interestingly, also exhaustion. That is, a more positive experience of the transition to remote teaching was associated with feeling both energetic and excited, and (although to a lesser extent) mentally and physically weary. Perhaps this is an indication of conscientiousness on the one hand, and commitment, on the other hand, thus reflecting a combination of academic pressure and a sense of duty in a new demanding situation. This would be in line with prior findings showing how engaged students with performance concerns are particularly susceptible to emotional exhaustion (e.g. Tuominen et al., Citation2020), and also concurs with the demands-resources model (e.g. Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, Citation2014).

The perceived strain of remote learning negatively predicted engagement and positively exhaustion and depressive symptoms, suggesting that the increased burden of remote learning significantly affected students’ study-related and more general well-being. The particularly strong predictive role of strain may be because, from the students’ viewpoint, the transition was not voluntary but compulsory. Lastly, the sense of alienation was the major predictor of depressive symptoms, which is in line with previous studies demonstrating the importance of social contact and interaction in higher education (Elmer et al., Citation2020; Richardson et al., Citation2017). During the pandemic, students’ social life changed dramatically also outside academia, which may have accentuated the prevalence and role of the sense of alienation. Given its strong association with the other remote teaching and learning experiences as well as well-being, social isolation may well be one of the most important factors to address when planning new remote teaching practices and environments.

Although the motivational profiles differed on remote teaching and learning experiences and well-being, the predictions from the experiences on well-being were comparable. This implies that the processes underlying the given effects are similar in all groups, but that the configuration of different motivational factors moderates its impact on students. For example, the more positive motivational mindsets (e.g. moderate or high expectancy together with high values and low costs) might buffer against the negative changes associated with the transition. Perhaps those holding a more adaptive motivational mindset may experience the change more as a challenge instead of a threat, as shown by Daumiller et al. (Citation2021), which then translates into more positive evaluations and a lesser impact on well-being.

Practical implications

Despite the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the altered situation offers an opportunity to learn more about students’ needs in remote teaching and learning, and to improve digital or blended practices. Our findings demonstrate that how students experience the changing learning conditions influences their well-being, and that qualitatively different motivational patterns play an important role in those experiences. This suggests that when planning and implementing new teaching practices, the awareness of students’ diverse motivational mindsets and how they contribute to a variety of study-related experiences would seem particularly beneficial.

The associations between students’ sense of alienation and depressive symptoms emphasise the importance of promoting students’ sense of belonging and peer support both during and beyond the pandemic. Also, since viewing studies as costly is related to inferior well-being, it is important to ensure that the academic demands during novel circumstances are reasonable and scaled to the given situation, and that sufficient support is available. Emphasising utility more than intrinsic value was accompanied by finding remote learning as taxing and experiencing emotional distress. This may be because remote learning is seen as a hindrance to completing studies. It would seem important to support students in finding intrinsic value in their studies, especially among these students emphasising more extrinsic outcomes.

University is a demanding phase in education and an important social context for students. Thus, it is vital that during and after the pandemic, activities are organised in a way that minimises the loss of social contacts, supports the monitoring of motivation and well-being, provides forums for students to engage in on- and off-task interaction, helps to identify students at risk, and allocates human resources targeted at students in need. Although minimising the loss of social contact during remote teaching and learning can be challenging, some significant strategies may be encouraging collaborative and small group working also in the context of remote studying and enabling students to connect with each other more freely. It may be valuable to encourage students to be responsive to and supportive of their peers, and teachers may consider reserving free time during lessons for student interaction by reducing the content to only the core issues.

Limitations and future directions

The study was cross-sectional due to which other types of predictions could be specified with the equally good model fit. While acknowledging the limitations of using cross-sectional data for such a design, we consider it useful for extracting the independent effects of remote teaching and learning experiences on well-being. Hence, we did not argue for strict causal relations between remote teaching experiences and well-being, but rather considered theoretical justifications, specificity, and time frame when specifying the models (i.e. measures of remote teaching and learning experiences explicitly referred to the transition and reflected factors that were directly influenced by the new situation). Longitudinal data would be needed to address the likely reciprocal relations over time.

Also, as the measures and their operationalisations were limited to the specific context and followed both the national discourse and already implemented surveys on the theme, we acknowledge that the coverage of remote teaching and learning experiences as well as well-being is limited. A broader set of variables reflecting different aspects and consequences of the exceptional situation would provide a more comprehensive view of its impact on students.

It was necessary to minimise the strain of completing the questionnaire for the participant,Footnote1 especially during the demanding time of the pandemic, while still gaining valuable information on the students’ experiences. Thus, we aimed to choose the most relevant items of each construct based on previous studies and the context. However, we acknowledge that the chosen items cannot represent the breadth of the full measures.

Naturally, the generalisation of our findings to other educational systems is limited, as the national guidelines for and implementation of remote teaching vary from country to country, despite the global nature of the pandemic. However, we would expect the findings on the patterning of motivation and its role in students’ experiences to have broader relevance and to provide a benchmark for similar studies in different educational settings. A related issue is our focus on students’ perceptions of the transition instead of the implemented practices. Although we consider students’ experiences particularly important, especially in connection with motivation and well-being, this perspective would likely benefit from a complementary approach charting the pedagogical solutions.

Conclusion

The findings of this study showed that students’ experiences of remote teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic were partly dependent on their motivation, but the way those experiences were linked with well-being was not. This implies that some students may be more susceptible to the negative consequences of remote teaching and learning than some others, but that the impact of certain experiences on well-being applies to all students. Consequently, practices to support students and help them cope with the challenging situation could be targeted at both motivation (e.g. promoting intrinsic value and reducing costs) and learning experiences (e.g. reducing strain by recalibrating demands and alleviating social isolation through new ways of interacting formally and informally). Given the disparity of students’ experiences, universities should now critically reflect on their policies, and evaluate the purposes and potential of both face-to-face classes as well as remote teaching and learning, in this unprecedented situation and beyond.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (97 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 As the survey included several other themes beyond this study, it was necessary to optimise the length of the survey. For this, we needed to minimise the number of items in our measures without sacrificing the sufficient conceptual scope of the underlying constructs.

References

- Bong, M. (2008). Effects of parent-child relationships and classroom goal structures on motivation, help-seeking avoidance, and cheating. The Journal of Experimental Education, 76(2), 191–217. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.76.2.191-217

- Daumiller, M., Rinas, R., Hein, J., Janke, S., Dickhäuser, O., & Dresel, M. (2021). Shifting from face-to-face to online teaching during COVID-19: The role of university faculty achievement goals for attitudes towards this sudden change, and their relevance for burnout/engagement and student evaluations of teaching quality. Computers in Human Behavior, 118, 106677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106677

- Ebner, C., & Gegenfurtner, A. (2019). Learning and satisfaction in webinar, online, and face-to-face instruction: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Education, 4, 92. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00092

- Eccles, J. S., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., & Midgley, C. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motivation (pp. 75–146). Freeman.

- EDUFI (2021). Etäopetuksen tilannekuva koronapandemiassa vuonna 2020 [Situation report of remote teaching during coronavirus pandemic in 2020]. Finnish National Agency of Education. https://www.oph.fi/fi/tilastot-ja-julkaisut/julkaisut/etaopetuksen-tilannekuva-koronapandemiassa-vuonna-2020

- Elmer, T., Mepham, K., & Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLOS One, 15(7), e0236337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337

- Elmer, T., & Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Depressive symptoms are associated with social isolation in face-to-face interaction networks. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58297-9

- Ewing, L., & Cooper, H. B. (2021). Technology-enabled remote learning during COVID-19: Perspectives of Australian teachers, students and parents. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 30(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2020.1868562

- Fiorilli, C., De Stasio, S., Di Chiacchio, C., Pepe, A., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2017). School burnout, depressive symptoms and engagement: Their combined effect on student achievement. International Journal of Educational Research, 84, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2017.04.001

- Gaspard, H., Dicke, A.-L., Flunger, B., Schreier, B., Häfner, I., Trautwein, U., & Nagengast, B. (2015). More value through greater differentiation: Gender differences in value beliefs about math. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(3), 663–677. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000003

- Gaspard, H., Wille, E., Wormington, S. V., & Hulleman, C. S. (2019). How are upper secondary school students’ expectancy-value profiles associated with achievement and university STEM major? A cross-domain comparison. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 58, 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.02.005

- Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hysenbegasi, A., Hass, S. L., & Rowland, C. R. (2005). The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 8(3), 145–151.

- Jiang, Y., Rosenzweig, E. Q., & Gaspard, H. (2018). An expectancy-value-cost approach in predicting adolescent students’ academic motivation and achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 54, 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.06.005

- König, J., Jäger-Biela, D. J., & Glutsch, N. (2020). Adapting to online teaching during COVID-19 school closure: Teacher education and teacher competence effects among early career teachers in Germany. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 608–622. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1809650

- Korhonen, V., Inkinen, M., Mattsson, M., & Toom, A. (2017). Student engagement and the transition from the first to second year in higher education. In E. Kyndt, V. Donche, K. Trigwell, & S. Lindblom-Ylänne (Eds.), Higher education transitions: Theory and research (pp. 113–134). Routledge.

- Larcombe, W., Baik, C., & Finch, S. (2022). Exploring course experiences that predict psychological distress and mental wellbeing in Australian undergraduate and graduate coursework students. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(2), 420–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1865284

- Lee, K., Fanguy, M., Lu, X. S., & Bligh, B. (2021). Student learning during COVID-19: It was not as bad as we feared. Distance Education, 42(1), 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1869529

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

- Matos Fialho, P. M., Spatafora, F., Kühne, L., Busse, H., Helmer, S. M., Zeeb, H., Stock, C., Wendt, C., & Pischke, C. R. (2021). Perceptions of study conditions and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic among university students in Germany: Results of the international COVID-19 student well-being study. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 674665. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.674665

- Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., & Baki, M. (2013). The effectiveness of online and blended learning: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 115(3), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811311500307

- Meda, N., Pardini, S., Slongo, I., Bodini, L., Zordan, M. A., Rigobello, P., Visioli, F., & Novara, C. (2021). Students’ mental health problems before, during, and after COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 134, 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.045

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

- Niemivirta, M., Pulkka, A.-T., Tapola, A., & Tuominen, H. (2019). Achievement goal orientations: A person-oriented approach. In K. A. Renninger, & S. E. Hidi (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of motivation and learning (pp. 566–616). Cambridge University Press.

- OECD (2019). Education at a glance 2019: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/da02f560-en

- Perez, T., Wormington, S. V., Barger, M. M., Schwartz‐Bloom, R. D., Lee, Y., & Linnenbrink‐Garcia, L. (2019). Science expectancy, value, and cost profiles and their proximal and distal relations to undergraduate science, technology, engineering, and math persistence. Science Education, 103(2), 264–286. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21490

- Richardson, T., Elliott, P., Roberts, R., & Jansen, M. (2017). A longitudinal study of financial difficulties and mental health in a national sample of British undergraduate students. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(3), 344–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-016-0052-0

- Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 472–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

- Salmela-Aro, K., & Read, S. (2017). Study engagement and burnout profiles among Finnish higher education students. Burnout Research, 7, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2017.11.001

- Salmela-Aro, K., & Upadyaya, K. (2012). The Schoolwork Engagement Inventory: Energy, dedication, and absorption (EDA). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28(1), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000091

- Salmela‐Aro, K., & Upadyaya, K. (2014). School burnout and engagement in the context of demands–resources model. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(1), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12018

- Savage, M. J., James, R., Magistro, D., Donaldson, J., Healy, L. C., Nevill, M., & Hennis, P. J. (2020). Mental health and movement behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic in UK university students: Prospective cohort study. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 19, 100357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2020.100357

- Schaufeli, W. B., Desart, S., & De Witte, H. (2020). Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT)—Development, validity, and reliability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249495

- Schnettler, T., Bobe, J., Scheunemann, A., Fries, S., & Grunschel, C. (2020). Is it still worth it? Applying expectancy-value theory to investigate the intraindividual motivational process of forming intentions to drop out from university. Motivation and Emotion, 44(4), 491–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-020-09822-w

- The Union of Upper Secondary School Students in Finland (n.d.). Lukiolaisten koronakyselyn tulokset [Results of the upper secondary school students’ Covid-19-survey]. Retrieved May 24, 2021, from https://lukio.fi/app/uploads/2020/04/Lukiolaisten-koronakyselyn-tulokset.pdf

- Tuominen, H., Juntunen, H., & Niemivirta, M. (2020). Striving for success but at what cost? Subject-specific achievement goal orientation profiles, perceived cost, and academic well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 557445. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.557445

- Tuominen-Soini, H., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2014). Schoolwork engagement and burnout among Finnish high school students and young adults: Profiles, progressions, and educational outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 50(3), 649–662. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033898

- Tuominen-Soini, H., Salmela-Aro, K., & Niemivirta, M. (2012). Achievement goal orientations and academic well-being across the transition to upper secondary education. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(3), 290–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.01.002

- Vermunt, J. K., & Magidson, J. (2002). Latent class cluster analysis. In J. A. Hagenaars, & A. L. McCutcheon (Eds.), Applied latent class analysis (pp. 89–106). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511499531.004

- Vermunt, J. K., & Magidson, J. (2005). Technical guide for Latent Gold Choice 4.0: Basic and advanced. Statistical Innovations Inc.

- Vermunt, J. K., & Magidson, J. (2016). Upgrade manual for Latent GOLD 5.1. Statistical Innovations Inc.

- Watt, H. M. G., Bucich, M., & Dacosta, L. (2019). Adolescents’ motivational profiles in mathematics and science: Associations with achievement striving, career aspirations and psychological wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 990. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00990

- Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2020). 35 Years of research on students’ subjective task values and motivation: A look back and a look forward. Advances in Motivation Science, 7, 161–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adms.2019.05.002