Abstract

As a part of supply chain management (SCM) initiatives to improve performance and productivity in construction projects, the use of construction logistics setups (CLSs) operated by third-party logistics (TPL) providers have increased. CLSs are often used in complex multi-project contexts, such as urban development districts, where extensive coordination of actors, resources, and activities is needed. The purpose of this paper is twofold: to investigate how main contractors engage in horizontal relationships with each other when coordinating activities and resources within and across projects in a multi-project context, and to investigate what role a TPL provider assumes when engaging in relationships with main contractors in a multi-project context. The findings are based on a case study of an urban development district with a mandatory TPL-operated CLS, and we apply the industrial network approach. In this multi-project context, the main contractors engage in coopetitive relationships, coordinating activities and resources within and across projects. The TPL provider coordinates actors, resources, and activities, facilitating smoother production by managing logistics and mediating coopetitive relationships. This can be understood as a multi-project coordination role and extends the role SCM can play in construction. In that role, a TPL provider can minimise tensions between coopetitive actors across a multitude of horizontal relationships and projects.

Introduction

Supply chain management (SCM) is claimed to improve logistics, performance and productivity in construction (Vrijhoef and Koskela Citation2000, Thunberg et al. Citation2017). One example of this is Vrijhoef and Koskela (Citation2000) work, which outlines the four roles that SCM can play in construction: (1) improving the interface between the supply chain and the construction site, (2) improving the supply chain, (3) transferring activities from the construction site to the supply chain, and (4) integrating the management of the supply chain with that of the construction site. Recent empirical studies add two new roles: (5) focussing on construction site logistics (Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016), and (6) coordinating logistics between the construction project and the local community (Fredriksson et al. Citation2021).

Another example of how SCM may improve performance and productivity in construction is the development of construction logistics setups (CLSs), which are increasingly used in large and complex construction projects (Fredriksson et al. Citation2021). A CLS is defined as “a governance structure for a construction project that has been agreed on to control, manage, and follow up the flow of materials, waste, machinery and personnel to, from and on the construction site” (Fredriksson et al. Citation2021, p. 327) and is often operated by a third-party logistics (TPL) provider. A CLS can vary from a checkpoint-based setup in which the TPL provider handles all the logistics onsite (Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016, Sundquist et al. Citation2018), to a terminal-based setup where the contractors have the ability to store materials for a limited period of time (Janné and Fredriksson Citation2019). Contracting a TPL provider is a new strategy in construction that affects roles, interactions and responsibilities (Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016, Karrbom Gustavsson Citation2018).

Most studies of TPL-operated CLSs focus on logistics management, project performance and productivity (Lindén and Josephson Citation2013, Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016, Sundquist et al. Citation2018) but there are also studies focussing on organisational issues such as the interface between the supply chain and the construction site (Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016) and how a TPL-operated CLS can support SCM in construction (Janné and Rudberg Citation2020). However, these studies mainly apply a single project perspective and do not acknowledge multi-project contexts. Bygballe et al. (Citation2013) conclude that SCM governs interdependencies between vertically connected actors, but it remains unclear what role SCM can play in a multi-project context with horizontal relationships.

Urban development districts are empirical examples of multi-project contexts where several construction project organisations operate, and where there are logistical and organisational challenges due to a multitude of actors (Hedborg et al. Citation2020). The coordination of various actors within and across projects in multi-project contexts is challenging (Engwall and Jerbrant Citation2003) and there are special demands on managing and organising logistics in urban development districts – both onsite and offsite (Sundquist et al. Citation2018, Janné and Fredriksson Citation2019).

TPL-operated CLSs are often mandatory for contractors to use in multi-project contexts. As such, a mandatory CLS is a CLS where the client (or the municipality) demands all contractors e.g. by contract, to use the same CLS for managing logistics. Such mandatory setup challenges the responsibility of the main contractor, who is used to managing and controlling logistics without being forced to adapt to the needs of others (Karrbom Gustavsson Citation2018, Fredriksson et al. Citation2021). A mandatory CLS also induces changes to activities and resources in the construction supply chain that pose challenges to contractors (Sundquist et al. Citation2018). As construction is a competitive industry (Keung and Shen Citation2017), main contractors are not used to cooperating with other main contractors, i.e. they are not used to engaging in horizontal relationships. However, in a multi-project context, cooperating with your competitors, or practicing coopetition (Bengtsson and Kock Citation2014), is a necessity.

Despite the growing use of mandatory CLSs, there is still a lack of knowledge about how a TPL-operated CLS influences interorganisational and interproject coordination in multi-project contexts, as well as how main contractors are affected by forced interorganisational relationships (Sundquist et al. Citation2018). In this paper, we take the main contractor perspective on a TPL-operated CLS in an urban development district to further the understanding of the evolving role of SCM in construction. To do this we investigate how interorganisational and interproject coordination among contractors are influenced by a TPL-operated CLS and the multi-project context. As such, the purpose of the paper is twofold: First we investigate how main contractors engage in horizontal relationships with each other when coordinating activities and resources within and across projects in a multi-project context, and second, we investigate what role a TPL provider assumes when engaging in relationships with main contractors in a multi-project context.

We go beyond the traditional “upstream” or “downstream” dyadic buyer-supplier relationship of SCM (Bygballe et al. Citation2010, Citation2013), investigating the horizontal relationships between main contractors, as well as indirect relationships (e.g. the involvement of third parties). We apply the industrial network approach (Håkansson and Snehota Citation1995, Håkansson et al. Citation2009), where the construction project is a temporary network of actors, resources and activities within “permanent” networks to which the various project actors are related, and which affect the activities and resources of the individual projects (Dubois and Gadde Citation2000). Even if the term “network” is also used in the SCM literature, the focus is usually on vertical relationships with sequential interdependencies. In contrast, the industrial network approach sees both direct and indirect relationships and the “pooled” interdependencies across the entire network that affect individual relationships (Bygballe et al. Citation2013).

The paper starts with a literature overview of: (1) construction SCM and TPL-operated CLSs, (2) coopetition in horizontal interorganisational relationships in the project context, and (3) an outline of the industrial network approach and the analytical model applied. The abductive method of the case study is then described, followed by the empirical findings, which are discussed in relation to analytical dimensions of the industrial network approach and the concept of coopetition. The paper concludes with an outline of its contribution to the literature and managerial implications, as well as ideas for further research.

Literature overview

Construction SCM

Construction projects are performed by temporary organisations at unique sites and can be compared to a temporary factory that evolves together with its product (Bygballe and Ingemansson Citation2014). From an SCM perspective, such projects induce temporary supply networks and project-specific logistics (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002a, Behera et al. Citation2015). However, multiple supply networks are involved when the delivery of construction materials needs to be coordinated with labour, equipment and machinery (Cox and Ireland Citation2002). A construction project includes different contractors and subcontractors – each with their own supply chains – which calls for extensive coordination between actors, resources and activities (Behera et al. Citation2015, Fadiya et al. Citation2015). Despite this, contractors have been slow in adopting SCM compared to other industries and tend to focus on upstream relationships with construction clients (Akintoye et al. Citation2000, Arantes et al. Citation2015).

Construction logistics management practices are described as “uncontrolled, disruptive and uncoordinated” due to the industry being project-oriented (Ying et al. Citation2018, p. 1931) and materials management in construction projects is often described as “ad hoc and intuitive” (Fadiya et al. Citation2015, p. 261). Consequently, deliveries are often late or inadequate, which negatively impacts production (Agapiou et al. Citation1998). Problems that occur on construction sites can be traced back to the supply chain and early project processes, although they can be mitigated by improved planning (Thunberg et al. Citation2017). A CLS can help by coordinating logistics and improving efficiency (Dubois et al. Citation2019).

A CLS can be initiated by construction clients or public actors such as regions or municipalities (Fredriksson et al. Citation2021). In most cases, a CLS is mandatory for all contractors and subcontractors to coordinate deliveries, increase project performance, reduce costs, and have a positive impact on the surrounding area by, for example, reducing traffic (Sundquist et al. Citation2018, Janné and Fredriksson Citation2019). A CLS can be internally developed or contracted to an external actor (Fredriksson et al. Citation2021) – typically a TPL provider who performs all or part of a contractor’s logistics function (Marasco Citation2008). However, since CLSs generally go beyond traditional TPL and provide additional services (e.g. planning systems), they can be considered fourth-party logistics setups (Fredriksson et al. Citation2021).

While it is common for construction clients to use consultants and contractors for certain activities (e.g. planning, design and construction), logistics have traditionally been performed by contractors (Miller et al. Citation2002). Consequently, all project actors, including the TPL provider, challenge ways of working. Hence, the CLS and TPL provider are threats to the contractors’ business model (Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016, Janné and Rudberg Citation2020).

A TPL-operated CLS may reduce project costs (Lindén and Josephson Citation2013), improve contractor performance and productivity (Sundquist et al. Citation2018), reduce environmental impact (Allen et al. Citation2014), and facilitate consolidation of deliveries (Dubois et al. Citation2019, Janné and Fredriksson Citation2019). Fredriksson et al. (Citation2021) conclude that business relationships are a vital part of CLSs and depend on the actors involved. The business relationships are also more complex compared to other TPL setups due to the many actors involved, and this complexity increases in a multi-project context. A mandatory project-specific CLS requires all actors to interact and coordinate their activities and resources (Havenvid et al. Citation2016a). However, more interaction may also lead to increased interorganisational tensions – especially in coopetitive horizontal relationships (Hedborg Bengtsson Citation2019, Hedborg et al. Citation2020).

In a multi-project context, contractors are forced to coordinate logistics, production and resources with contractors in other projects. However, most previous studies focus on SCM efforts in single projects (cf. Lindén and Josephson Citation2013, Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016, Janné and Rudberg Citation2020). There are studies who address multi-project contexts and to some extent acknowledge the connections of the involved projects (cf. Dubois et al. Citation2019, Janné and Fredriksson Citation2019). However, the coopetitive relationships between contractors and the TPL provider’s responsibility to manage interorganisational relationships has been overlooked.

Coopetition

Inter- and intra-organisational relationships that involve simultaneous cooperation and competition are referred to as “coopetitive” relationships (Brandenburger and Nalebuff Citation1996, Bengtsson and Kock Citation2000). Bengtsson and Kock (Citation2014, p. 182) define coopetition as “a paradoxical relationship between two or more actors simultaneously involved in cooperative and competitive interactions regardless of whether their relationship is horizontal or vertical”. Vertical coopetition is exemplified by the relationship between clients and contractors within a single construction project (Eriksson Citation2008), while horizontal coopetition can involve cooperation between actors who compete through the services or products they offer, e.g. material suppliers or contractors across multiple projects.

Coopetitive horizontal relationships are generally voluntary, and both actors benefit (Bengtsson and Kock Citation2000). However, there are also examples of forced horizontal coopetition, such as when a client or authority forces two competing suppliers to work together (Raza-Ullah et al. Citation2014). It can also occur as a consequence of emergent circumstances and does not have to be intentional (Tidström Citation2008).

Coopetition is often described as a paradox of two contradictory forces (Chen Citation2008, Raza-Ullah Citation2020) that induce tension (Fernandez et al. Citation2014, Raza-Ullah et al. Citation2014), which has to be managed. The context in which coopetitive relationships occur influences this tension. For instance, in a project where the actors have to work together intensively under time pressure, the tension might be more apparent compared to a more stable context (Fernandez et al. Citation2014, Raza-Ullah et al. Citation2014). Furthermore, forced coopetitive relationships are at higher risk of tension and need greater management (Mariani Citation2007).

Cooperative strategies have the most positive outcomes when managing tensions in coopetitive relationships (Tidström Citation2014). To support cooperation in a coopetitive relationship, a third party, acting as a mediator, can help manage tensions between the actors (Bengtsson and Kock Citation2000). However, such a third party requires legitimacy and may actually cause further tensions (Fernandez et al. Citation2014). There is some research on who may serve as such a mediator and how they can help manage coopetitive tensions. TPL providers can assume a mediating role in vertical relationships (Sundquist et al. Citation2018), though this has not been studied in depth and not in horizontal relationships.

Industrial network approach

The industrial network approach, or IMP perspective (Industrial Marketing and Purchasing), is an interorganisational perspective based on empirical studies of long-term business relationships and the key role they play in the operations of the firm (Håkansson et al. Citation2009, Håkansson and Snehota Citation2017). It is based on, and has mostly been applied to, the study of stable relationships in traditional manufacturing industries such as the automotive industry (e.g. Dubois and Fredriksson Citation2008). However, it has also been applied to relationships in the construction industry, which commonly are more adversarial and project-based (Havenvid Citation2015). There are several IMP-based studies on how actors organise in relation to each other in this setting (e.g. Dubois and Gadde Citation2002a, Havenvid et al. Citation2016b), and what the effects are, for instance, on logistics (Sundquist et al. Citation2018, Dubois et al. Citation2019). While the project-based aspect of construction creates a loosely coupled system over time (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002a), studies show there are efforts to connect organisations and projects to improve innovation, learning and efficiency (e.g. Havenvid et al. Citation2019). Despite these loose couplings between firms, structural changes can be difficult and costly due to firms engaging in standardisation and adaptation, and forming “heavy” technical and organisational structures, i.e. interdependencies across firms (Håkansson et al. Citation1999). One example is the re-introduction of wooden frames in houses in Sweden, which turned out to be difficult and costly due to interorganisational investments over time in relation to other materials (Bengtson and Håkansson Citation2007).

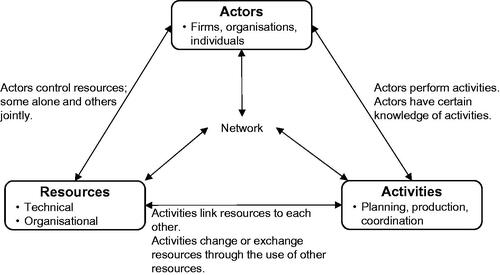

The ARA (Activities-Resources-Actors) model is a three-dimensional analytical framework developed within the industrial network approach for analysing business relationships in terms of the adaptations made between actors, their activities and resources over time (Håkansson Citation1987). Actors can be organisations with social sentiments representing technical (e.g. materials and machines) and organisational (e.g. competences, skills and routines) resources used in activities such as planning, production or coordination. shows how actors, resources and activities are interrelated in that actors control resources, alone or jointly, and perform activities in which they have particular expertise. The performance of these activities depends on access to and exchange of resources, which might develop because of adaptation processes between actors. The model also demonstrates the interconnectedness of actors, resources and activities in networks of interdependent relationships, i.e. business relationships depend on and affect other business relationships.

Figure 1. The ARA Model, adapted from Håkansson (Citation1987).

According to the industrial network approach, firms are dependent on other firms (e.g. key suppliers and customers, partners and competitors) to run and develop their operations. No single actor can control all activities and resources, and all are dependent on other actors for access to, as well as coordination, integration and development of key activities and resources (Håkansson and Snehota Citation1995, Gadde et al. Citation2003, Håkansson et al. Citation2009). As such, firms need to build interdependencies with other actors in a systematic way, making interaction an essential business activity.

The choice of the industrial network approach was motivated by our focus on the content or substance of interorganisational relationships in an industrial setting, for which this approach is particularly well-suited. Selviaridis and Spring (Citation2007) and Marasco (Citation2008) recommend the industrial network approach for further studies of TPL. They argue not only that TPL arrangements are part of the supply chain network (Marasco Citation2008), but also that these arrangements have mainly been studied through a dyadic relationships approach (Selviaridis and Spring Citation2007). In addition, the ARA model is particularly well-suited to map interactions and adaptations between actors, activities and resources, and how they are interrelated in a network of relationships. As such, it can be used to elucidate how interaction between any two actors affects other actors in the network (Marasco Citation2008). Furthermore, by applying the concept of coopetition, the cooperative and competitive elements of those interactions can be revealed. Furthermore, a recent study by Sundquist et al. (Citation2018) concludes that establishing a TPL-operated CLS is significant and may result in a reorganisation of actors, resources and activities, as well as a reorientation of the entire network.

Method

Research approach and case selection

An abductive research approach called “systematic combining” (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002b) was adopted, implying an iterative process of moving between data collection and literature to grasp the empirical phenomenon and how it can be analysed. During the data collection and initial analysis, it became clear that the main contractors were both competitors and co-operators. Coopetition was therefore added as an analytical concept to better understand these relationships.

A case study approach was chosen because it allowed the study of complex organisational contexts and interactions (Flyvbjerg Citation2006). Case studies also allow the study of interorganisational relationships in industrial networks (Halinen and Törnroos Citation2005, Easton Citation2010). The case in focus was the Stockholm Royal Seaport (SRS) – an urban development district in Stockholm, where a multitude of construction projects were being managed by various construction clients and their main contractors utilising a TPL-operated CLS.

Data collection

The empirical data were mainly collected by one of the authors between November 2018 and November 2019 and included semi-structured interviews, observations and a large number of documents such as meeting minutes, work disposition plans, the City’s evaluation report of the CLS, and descriptions of services and resources provided by the CLS. Two of the co-authors participated in some interviews to minimise potential bias. The data collection and analysis began by studying documents to gain a better understanding of the development of the SRS and more specifically the TPL-operated CLS.

In total, 11 semi-structured interviews were conducted with the main contractors’ site managers and supervisors, the TPL provider’s representatives and a local government representative (i.e. the City) (see ). All the contractors listed in were asked to participate but some of them declined and others did not reply. The interviews were recorded and transcribed. The interview guides with the contractors and stage coordinators were based on the three dimensions of the ARA model, and respondents were asked how they interacted with other actors in terms of resources and activities. They were also asked how interactions were initiated, how the TPL provider influenced these interactions, about their previous experiences of CLSs and interactions with main contractors from other projects, their perception of the SRS and the CLS, and about cooperation and competition onsite. During the interviews, the respondents were also asked to comment on the observations of coordination meetings and site visits.

Table 1. Summary of interviews.

Table 2. Description of construction projects and main contractors in the studied stage.

The observations were done at coordination meetings between the TPL provider and the main contractors. In total, 22 coordination meetings were observed and hand written notes taken, which were later typed up. These observations facilitated a deeper understanding of how the TPL provider was coordinating the actors, resources and activities. Observations were also conducted during several site visits and safety inspections at the construction sites.

Data analysis

The interviews and notes were analysed according to the ARA model, focussing on how the actors interacted with each other, what they interacted about (resources and activities) and how the interactions were governed and coordinated. The data were first sorted according to the ARA dimensions and then by the type of interaction, e.g. interactions between main contractors, interactions between the TPL provider and main contractors, whether they were cooperative or competitive, the effects of interactions, etc. Illustrative quotes were selected when writing the narratives.

Case description

The SRS comprised several sequential stages – each stage including a multitude of construction projects executed side by side in a designated area. Typically, five to ten construction clients and their main contractors and subcontractors were involved in each stage. Already in the early planning stage of SRS, the City of Stockholm decided to use a CLS (Bygglogistikcenter [BLC] in Swedish) for the whole district. The case study focussed on one of the stages of the SRS, which included nine housing projects.

Based on the expert recommendations of a logistics consultant, the City designed the BLC and procured a TPL provider to operate it. The City wanted the BLC to “be on the cutting edge of construction logistics” and “promote construction logistics research with the aim of using the [BLC] to generate growth in the construction industry” (Exploateringskontoret Citation2016). The logistics at all stages of the SRS were managed and governed through the BLC, which had an office with a terminal for short-term storage of materials. All the clients and main contractors had to use the BLC and there were contractual arrangements stipulating the conditions of use. The BLC was also responsible for recycling waste materials, erecting gates and fences, road maintenance, surveillance, and providing additional services such as machines, logistics consultants and inward transportation of materials. When the case study began, the BLC had just been reformed in terms of business and price models, the mandate of the TPL provider, and a replacement TPL provider had just been brought in.

Studied actors

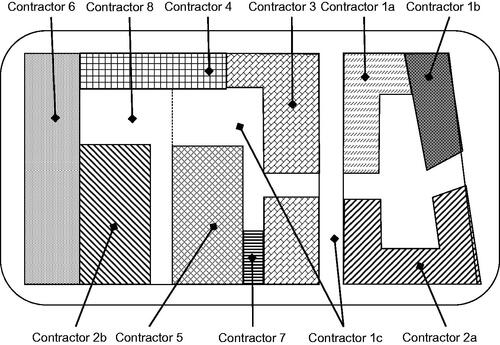

This study is about interaction containing both cooperative and competitive elements, i.e. coopetition. The focus is only on the main contractors and not contractors in general. There were eight main contractor firms operating in the studied stage (see ). Contractors 1a to 1c were different site organisations from the same main contractor firm, as were contractors 2a and 2b. All the site organisations had site managers, some of whom had experience from previous stages of SRS.

The disposition plan of the studied stage (see ) illustrates how the different projects related to each other geographically. All the construction projects were in their late stages and were performing interior works and frame completion, except for contractor 2b, who had already finished by the time the case study began.

Another important actor was the TPL provider, which was a consultancy firm specialising in construction logistics. It was procured by the City to operate the BLC, i.e. to manage all the resources (e.g. terminal, stage coordinators, disposition plans, and coordination meetings) and activities (e.g. storing materials, coordination of deliveries and production activities between projects, and waste management) associated with and provided by the BLC as a representative of the City. The TPL provider made decisions on the City’s behalf regarding various issues that arose in the different stages. It also contributed competences and experienced staff, such as stage coordinators who coordinated activities, such as large deliveries, and resources, such as coordination meetings and disposition plans. The stage coordinators also served as the contractors’ point of contact at the BLC. Although the stage coordinators worked for the TPL provider, the City was involved in their initial selection process because they had to make decisions on the City’s behalf – something that had been missing in the previous version of the BLC.

Findings

Activity dimension

Horizontal interaction among contractors

When main contractors proactively interacted with other main contractors, it was usually to benefit the progress of their own project. These interactions mostly involved the coordination of logistics to minimise disturbance to production. The contractors also did extensive planning to minimise the need for coordination and interaction with other contractors.

If I want to book a mobile crane that might block [Contractor 6] further away, it is my role to contact him. (Site manager, Contractor 4)

However, working in cramped conditions with shared courtyards meant that, for certain activities, workers had to pass through or even work at a different contractor’s site. This required special coordination since the contractors were responsible for the health and safety of all construction workers on their site, including those from other contractors.

The coordination of production between the different projects was done by the contractors themselves, since the TPL provider did not have the power to decide whether one contractor’s work should have priority over another’s. One example of this extensive coordination was the work done in the courtyard by Contractor 8, who had to coordinate with contractors 1c, 2b, 4, 5 and 6 (see ). However, the limited working space also provided opportunities, for example when two main contractors coordinated their procurement, which went beyond the site organisations and involved both their purchasing departments.

Between us and [Contractor 1a], I would say there has been some [cooperation]. We have tried, for example, to procure a landscaping contractor because our projects are connected to each other with a courtyard. (Site manager, Contractor 2a)

TPL provider and contractor interactions

The TPL provider toured the site several times a day to interact with the main contractors, follow up on production and logistics issues, and plan activities such as coordination of cranes and deliveries. During these tours, the TPL provider informally met with main contractors to discuss production or logistics issues or concerns.

The contractors were obliged to coordinate large deliveries, and the use of equipment that might block access routes, with the TPL provider and other contractors nearby. The TPL provider usually followed up with the contractor either by email or phone or, for larger enquiries, by meeting onsite with the contractor. The TPL provider then communicated this information to the other contractors through weekly meetings, which were also a forum for other contractors to provide input on production and planning. However, the TPL provider stressed that it only had the mandate to coordinate activities in shared spaces and not on construction sites.

The extent of interactions between the TPL provider and the main contractors varied between the different projects. While some had minimal interaction with the TPL provider, others interacted regularly. The need for interaction fluctuated depending on where in the production cycle the contractors were.

The main contractors that required minimal interaction with the TPL provider typically managed projects that did not physically interfere with other projects, but there were also contractors that managed to coordinate their work without involving the TPL provider. Those having minimal interaction followed the regulations of the BLC and got their subcontractors to do the same. Having fewer interactions with the TPL provider was also the result of low activity in the project, such as when a client had not sold enough apartments to begin production.

Extensive interactions between main contractors and the TPL provider were due to various problems in the projects, or to the fact that residents had already moved into their new homes. For instance, Contractor 1a had problems with the frame, forcing them to rebuild it. This work was noisy and required large machines for an extended period of time. During this time, contractors 2a and 3 were almost finished and some residents had already moved in. This situation was handled by the TPL provider, who coordinated traffic routes so that deliveries and other traffic were able to pass by, while Contractor 2a had to coordinate with contractors 1a and 3 to install decibel metres in the apartments where residents had moved in.

Furthermore, some contractors and subcontractors regularly ignored BLC regulations, for instance by opening the gates for unscheduled deliveries. Ignoring the regulations was often due to pressure to finish the projects on time and on budget. In those cases, the TPL provider first contacted the construction client to get the attention of a main contractor, or sometimes mediated between main contractors and construction clients. The stage coordinators described some of the interactions with the contractors as a “poker game”.

I have nothing to do with the project, but I try to help them with their progress. And if the client says that some of the parts of this meeting are not for others, then it is not for others. Then, it is between us. In the end, I make a plan in order for [Contractor 6] to get it right in the end, and if they don’t give me the correct information, then it will only hit them at a later stage. I have it like this with several contractors. (Stage coordinator)

There were occasions when all the main contractors came together to speak with a unified voice, such as when they complained to the City about the previous TPL provider and the whole setup of the BLC, which led the City to terminate the contract with the previous TPL provider and procure a new one.

Finally, the TPL provider gathered information on the overall progress of the stage, as well as statistics regarding deliveries and collected waste. This was all reported to the City and the main contractors via, for example, the stage disposition plan or the BLC webpage. The TPL provider was thus an important part of maintaining the project network.

This network is kept together by the City, or by the BLC really. […] After all, we hold these coordination meetings and site manager meetings […], all of this. So, it is the BLC that keeps this together so that it becomes one. Because I do not believe [the contractors] have any cooperation of their own. (BLC manager)

Resource dimension

Horizontal interaction among contractors

There were several joint facilities in the stage, such as underground garages and courtyards, which were constructed by several main contractors. Each client was responsible for a percentage of the garages, and the construction of the joint facilities sometimes interfered with the construction projects. To coordinate logistics and production and reduce delays to the projects, the main contractors initiated their own coordination meetings, which tended to focus on who was responsible for what.

[W]e had a joint facility [when I worked for] [Contractor 3] as an example, then we had our own coordination meetings. […]. Then it was [Contractor 1c] who was the landscaping contractor, and if they are hindered, then everyone must be involved and pay. And no one is interested in that, so then it is important to be proactive in ensuring that, e.g., a basement wall is finished and such things. (Site manager, Contractor 6)

Joint utilisation of resources occurred, but was not done on a regular basis. One example was when Contractor 2a needed an additional crane and contacted Contractor 1a in order to borrow theirs. Another example was when Contractor 1b offered the other contractors to rent their portacabins for a period when Contractor 1b did not need them. They were rented by a contractor in a nearby stage, which was made possible by the TPL provider’s overview of SRS. However, information and knowledge were the most common resources exchanged between contractors. For example, when several construction projects were being executed next to each other, the main contractors became aware of each other’s subcontractors working in other parts of the stage, and asked each other for references, as it was preferable to use a subcontractor that was already present and familiar with the BLC.

Main contractors from the same firms acting in projects with different budgets and accounts, i.e. contractors 1a, 1b, 1c, 2a and 2b, had closer cooperation, e.g. borrowing construction workers from each other instead of using subcontractors.

TPL provider and contractor interactions

The stage coordinators were the TPL provider’s most important resource for coordinating actors, resources and activities within and across projects. The stage coordinators were the TPL provider’s “eyes and ears” in each stage, regularly doing site tours and interacting in a spontaneous way with contractors onsite. In addition, they coordinated production between different stages of SRS and one of them also acted as “coordinating stage coordinator”, with the responsibility for coordinating logistics and production activities between stages on an aggregated level.

Meetings were important forums for the joint planning and coordination of activities, resources and actors in the stage. The TPL provider initiated weekly and monthly stage coordination meetings, led by the stage coordinators and attended by the site managers and/or supervisors from the main contractors. The weekly meetings focussed on the overall progress of the projects, and the contractors informed attendees of upcoming activities that may affect other projects, such as large deliveries or a crane assembly.

The monthly meetings were arranged by the TPL provider together with the City’s coordinator for health and safety. Attendees at these meetings included the main contractors’ site managers, the City’s construction manager for civil work and stage project manager, and representatives from the fire department, police and security company working in the stage. These meetings had a wider and more long-term focus on the progress of the stage, including planning of phases and finishing dates when residents would move in. These meetings had a strong focus on health and safety and always ended with a health and safety inspection of the entire stage.

A stage disposition plan was handed out to the main contractors at each meeting that contained the latest information about access routes, gates, cranes, projects and loading areas. The information shared at the meetings was essential for the TPL provider to update disposition plans and activity schedules. The main contractors could also raise questions or concerns with the stage coordinators and other main contractors.

Actor dimension

Horizontal interaction among contractors

Based on the interviews and observations, the main contractors did not consider each other as direct competitors in the stage, despite being from different firms. However, neither did they cooperate unless it was absolutely necessary or could lead to direct benefits, such as when producing joint facilities or initiating joint procurement. Spatial and temporal placement in the stage and personal relationships helped initiate interaction when it did occur. When the main contractors needed to deal with each other, they often did so by reaching out directly to one another; only in rare cases did they go via the TPL provider.

Seeking cooperation with another contractor was, however, not considered the normal thing to do. The main contractors prioritised relationships within their projects (e.g. with subcontractors), rather than across projects. The organisational and economic boundaries of firms and projects decreased cooperation – even between contractors from the same firm (contractors 1a, 1b, 1c, 2a and 2b); as the projects had different clients, they were organised as separate business units with separate activities and resources. However, contractors belonging to the same firm appear to have had a greater inclination to seek cooperation, as in the case of borrowing workers from each other.

We have tried to find cooperation when we have been in need of double cranes, so we have talked to each other and been able to solve it together. But when it comes to cooperation in general, for us it is above all the cooperation we have with our subcontractors. This is where our main focus is, I must say. (Site manager, Contractor 2a)

TPL provider and contractor interactions

Through the stage coordinators, the TPL provider interacted with individual contractors to solve problems that affected various projects of the stage. This was a common type of interaction. The different coordination meetings, on the other hand, represented interaction between the TPL and multiple contractors. During the weekly and monthly coordination meetings, all contractors and the TPL provider interacted with each other. This was appreciated by the contractors as most of them only interacted with contractors from adjacent projects.

Sometimes I do not believe the content of the coordination meetings is necessarily the most important thing, but to have a forum where everyone meets and says hello. It becomes a little easier to pick up the phone when you need something or if something hassles you. So, I believe they have been very important to create a team spirit within the stage. (Site manager, Contractor 2a)

While the contractors thought the BLC had been forced upon them and increased the production costs, the TPL provider was considered to be a neutral party, having no interests of its own besides focussing on the overall progress of the stage. Its main function was to coordinate logistics and material flows in SRS, and maintain production in all projects of the stage. To do so, the TPL provider needed to coordinate the different actors with their different resources and activities. Occasionally, this required interacting with contractors, as indicated above, but overall, it was about facilitating a “self-playing piano” of contractors coordinating themselves through regulations, instructions and meetings.

The task of a construction logistics centre is to safeguard everyone’s accessibility and safety. There, you have to have someone who can go in and make decisions that may be a bit uncomfortable for the moment, but you do it for the good of the collective. And I have a hard time seeing that happen if you do not have a [coordinating] function added. […] But someone has to take that role and work with stage planning and take on that whole coordination role. (BLC Manager)

Discussion

Returning to the twofold purpose of this paper, the discussion will first address how the main contractors interacted with each other in the multi-project context, and secondly how the TPL provider engaged in relationships with these contractors for the sake of multi-project coordination. The discussion will conclude by asking what this means for the evolving role of SCM in construction, based on the roles of SCM described by Vrijhoef and Koskela (Citation2000), Ekeskär and Rudberg (Citation2016) and Fredriksson et al. (Citation2021).

Horizontal interaction among contractors

The type of main contractors involved in the SRS do not usually engage in cooperation in relation to individual projects. Generally, they can be considered competitors in the sense of competing for contracts (Keung and Shen Citation2017). In the SRS, they operated in separate projects with separate clients and there were no client-driven incentives to cooperate (as in a shared contract). Despite these conditions, the study shows several examples of contractors practicing coopetition, i.e. cooperating despite being competitors (Bengtsson and Kock Citation2014). In terms of activities, the study shows how contractors needed to interact amongst themselves on matters such as logistics and production to avoid disturbance and delays in their plans. The multi-project context meant that they could be working right next to each other or even on each other’s sites (cf. Hedborg and Karrbom Gustavsson, Citation2020), which calls for extraordinary interaction and coordination of various types. There were also examples of interorganisational interaction spreading beyond the site organisations, as in the case of joint procurement involving the purchasing departments of two contractor firms. As the TPL provider did not have the power to make decisions on individual contractors’ operations, the contractors dealt directly with each other.

In terms of resources, the study shows that contractors needed to interact when involved in producing joint facilities, such as garages and courtyards, which led them to initiate their own coordination meetings. In exchange for economic compensation, they also made various resources available to each other, such as cranes, portacabins and workers. Sharing resources was thus seen as economically beneficial and helped build productive relationships with their temporary “neighbours” (Hedborg et al. Citation2020, Hedborg and Karrbom Gustavsson Citation2020).

However, as actors operating within separate projects with their own organisational and economic boundaries, the contractors only sought cooperation when necessary. In cases where the contractor site organisations belonged to the same contractor firm, they shared human resources across projects. Although the TPL provider was not involved in most of these interactions, the regular meetings they provided facilitated interactions by providing a social forum where they could initiate a dialogue. Indirectly through the regulatory framework of the BLC, the TPL provider also regulated how contractors should operate.

TPL and contractor interactions

In this multi-project context, the TPL provider needed to interact with both separate contractors in single projects and several contractors on a multi-project level. When the contractors needed to coordinate their large deliveries and production activities, the TPL provider communicated this to the other contractors, who then could provide further input. Thus, the concept of BLC, which the TPL provider executed, made the activities of the single project visible on the multi-project level so that activities could be coordinated also from a multi-project perspective. There were three main resources the TPL provider used to enable this multi-project coordination role: (1) the regulatory framework of the BLC, (2) stage coordinators, and (3) coordination meetings with all contractors across the stage. The TPL provider, as a coordinating actor, interacted with separate contractors in relation to various problems that needed to be solved – in which case, the stage coordinators were essential – or when contractors did not comply with BLC regulations. Less interaction was needed if the regulations were complied with, things ran smoothly or the contractor was in a less intense production phase. This implies that the TPL provider had a set of resources (cf. Fredriksson et al. Citation2021) that were used to facilitate interaction processes, such as the continuous coordination meetings, and that could be “activated” when needed to ensure that projects across the stage ran smoothly, such as the stage coordinators.

Regarding the forced nature relationship between the TPL provider and contractors, as well as the TPL provider taking on activities traditionally handled by contractors, such as receiving deliveries and coordination activities between neighbouring projects, both parties appeared to see mutual benefits of basing their coopetitive relationship mostly on cooperation, which is necessary to manage tension (Tidström Citation2014). Having the TPL provider as a coordinator allowed for the main contractors to focus on their own projects. The increased production costs associated with the BLC was attributed to the setup of the BLC, and by extension the City, rather than the TPL provider. This contributed to the contractors’ perception of the TPL provider as a neutral party. Having a coordinating function in single projects and on the multi-project level seems to have strengthened the contractors’ view of the TPL provider (cf. Fernandez et al. Citation2014) as a mediating actor.

The evolving role of SCM in construction – a seventh role in a multi-project context

The role that SCM played in the SRS through the BLC concept was not only to manage logistics and facilitate production in line with established roles that SCM plays in construction (Vrijhoef and Koskela Citation2000, Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016, Fredriksson et al. Citation2021), but also to act directly and indirectly as a mediator between the main contractors in a multi-project context; directly by engaging in dyadic interactions with separate contractors and projects of the stage and indirectly through the BLC’s regulatory framework and meetings to facilitate interaction among contractors. The TPL provider also acted as mediator between the main contractors and the City by implementing the regulatory framework of the BLC. In addition, although not part of this study, it also acted as mediator between the main contractors and their clients. In this way, the TPL provider coordinated not only each individual project but also the whole stage from a multi-project perspective.

As such, the TPL provider did not only provide “traditional” logistic services (Janné and Fredriksson Citation2019) and coordinate logistic management (Ying et al. Citation2018), but was instigating activities and using its resources to coordinate several projects across an urban development district in a multi-project context. This included managing coopetitive tensions among the main contractors across projects. This multi-project context involved a number of different main contractor organisations that needed to co-exist during the stage, which sometimes led to tense relationships when coordinating amongst themselves. The study shows that the TPL provider provided forums for easing and preventing such tensions via meetings and stage coordinators. Thus, the TPL provider had the legitimacy to act as a mediating third party between contractors (Bengtsson and Kock Citation2000, Fernandez et al. Citation2014). This wider role included coordination on single-project and multi-project levels and, as such, brought different projects together in the multi-project context (Hedborg et al. Citation2020).

The wider responsibility of the BLC through the TPL provider was a result of the multi-project context where merely logistical competence (Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016) was not enough. Coordinating activities and resources in a multi-project context was more complex than in a single project in that it required coordinating interorganisational interaction across projects, which included horizontal interaction among contractors. The multi-project context thus required a different set of activities and resources managed and coordinated by the BLC through the TPL provider.

In relation to the four roles of SCM addressed by Vrijhoef and Koskela (Citation2000), the role played by the TPL provider in this multi-project context most closely resembles the fourth role, i.e. integrated management of the supply chain and the construction site. However, this fourth role does not fully acknowledge the multi-project level. When acknowledging a multi-project level, it seems that, in addition to the fifth and sixth roles introduced by Ekeskär and Rudberg (Citation2016) and Fredriksson et al. (Citation2021) respectively, with the development of a mandatory TPL-operated CLS in a multi-project context, a seventh role of SCM in construction can be identified. This role is here termed a multi-project coordination role.

When describing the four roles of SCM in construction, Vrijhoef and Koskela (Citation2000) distinguish between the supply chain and the construction site. However, in the multi-project context of SRS, there were several construction sites managed by different contractor organisations. While the contractor organisations were to a degree interdependent, all of them were responsible for managing their own supply chains. The main contractors did some coordination of logistics and production activities, when necessary, but none of them had a full overview of the multi-project context. The overview was realised by the TPL provider on behalf of the City. This is in line with the benefits of a coordinating role across projects discussed by Dubois et al. (Citation2019).

Furthermore, the seventh role of SCM in construction does not exclude the six previously described roles. How the individual construction projects worked with SCM is beyond the scope of this study, though all of them used prefabricated materials, such as concrete elements, thereby moving production from the construction site to the supply chain (third role). Furthermore, the BLC provided a structured interface between the construction sites and the supply chains (first role), as well as improved logistics in the construction projects (fifth role).

The common denominator between the fifth, sixth and seventh roles of SCM in construction is that they all focus on the construction site. All three roles have also been described in studies of TPL-operated CLSs, which might be due to TPL-operated CLSs often being initiated by clients or municipalities (Hedborg Bengtsson Citation2019, Fredriksson et al. Citation2021) whose focus is on the construction project and not the supply chain. By introducing a TPL-operated CLS, the initiator can improve logistics on the construction site (fifth role), reduce disturbance to the surrounding society (sixth role), and coordinate between projects and stages in a multi-project context (seventh role).

This is similar to an additional role mentioned but not explored by Vrijhoef and Koskela (Citation2000, pp. 171-172): “management of the construction supply chain by facility or real estate owners”. The setup of a TPL-operated CLS is in line with this additional role of SCM in construction. In the case of SRS, the City managed the construction supply network vertically and horizontally by setting up the BLC, which allowed the City to monitor and manage progress and coordinate the different stages of the project. The City’s schedule for upcoming stages relied on the progress of previous stages, so coordinating interactions in the multi-project context was vital for the overall progress of the urban development district.

Conclusions

The main contributions of this study relate to the evolving role of SCM in construction, and specifically the coordinating role of a TPL-operated CLS in a multi-project context. Through an investigation of how main contractors engaged with each other in such a context, and examining the role of a TPL provider in a multi-project coordination effort, this study’s contribution covers three main areas, which are outlined below.

First, by investigating a multi-project context, this study provides insight into the horizontal dimension of SCM in construction, i.e. horizontal relationships between main contractors. This was enabled by applying IMP as analytical framework, more specifically the ARA model (e.g. Håkansson et al. Citation2009). The analysis of activities, resources and actors in relation to contractor relationships shows that, while main contractors generally competed for contracts, they also cooperated with each other on interproject issues to facilitate production. Although their cooperation efforts mainly involved dyadic and reactive interactions such as coordinating logistics and production, there were also examples of temporary relationships that evolved beyond the site organisations. Thus, despite highly competitive and adversarial contractor relationships (Miller et al. Citation2002, Keung and Shen Citation2017), several contractors managed to develop coopetitive relationships. Our study indicates that this would have created more tensions if there had not been a third party acting as a mediator and facilitator in both direct and indirect ways. This indicates the importance of going beyond the traditional focus on dyadic buyer-supplier relationships in construction SCM research. From a network perspective, it is revealed that a multi-project context cannot be treated as a series of projects, but needs to be viewed as a network of interdependent projects. The study shows that horizontal interactions are important and that the coordination of those interactions, benefitting not only the multi-project context but also the individual projects, is a highly meaningful activity.

Secondly, the study provides insight into the role of the logistics coordinator within such a context, in this case a TPL provider operating a CLS. We identify this as the seventh role of SCM in construction. Within this multi-project context, the TPL provider took on a role that went beyond traditional logistics management. It had an overview of the multi-project context and provided resources in the form of regulations, coordination meetings and stage coordinators to help contractors coordinate activities and resources amongst themselves and across projects. Thus, the role of the TPL provider as a third-party mediator of horizontal relationships expands the responsibility of a CLS in a multi-project context (Sundquist et al. Citation2018, Fredriksson et al. Citation2021) and indicates how a CLS may be utilised. By addressing the complexity of relationships among interdependent actors in a multi-project context, a TPL provider can widen its focus from traditional logistics management to interproject coordination. This echoes earlier findings claiming that one objective of a TPL provider, besides coordinating logistics, can be to facilitate interorganisational cooperation (Behera et al. Citation2015, Hedborg Bengtsson Citation2019). While earlier studies show that a TPL provider should be given authority to govern operations (Janné and Fredriksson Citation2019), our study shows that, from a coopetition perspective, a TPL provider may adopt the role of a third-party mediator of horizontal coopetitive tensions (Bengtsson and Kock Citation2000, Fernandez et al. Citation2014).

Thus, when a TPL provider is not limited to providing logistical competence in single construction projects (Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016, Sundquist et al. Citation2018), but also takes on the role of coordinator, this evolves the role of SCM in construction. We view this as SCM’s seventh role, extending the work of Vrijhoef and Koskela (Citation2000), Ekeskär and Rudberg (Citation2016) and Fredriksson et al. (Citation2021). In that role, a TPL provider can minimise tensions between coopetitive actors across a multitude of horizontal relationships and projects, i.e. SCM includes a multi-project coordination role. This furthers the understanding of SCM in construction – in particular the function of a TPL-operated CLS in multi-project contexts (Ekeskär and Rudberg Citation2016, Janné and Rudberg Citation2020, Fredriksson et al. Citation2021).

Thirdly, the abovementioned insights have implications for how to apply SCM managerially – specifically TPL-operated CLSs in multi-project contexts. The multi-project coordination role requires a set of competences that actors initiating a TPL-operated CLS need to consider when specifying procurement criteria. Since the role of the CLS may be much wider in a multi-project context than in a single project context, the contractual and organisational setup needs to incorporate interorganisational and interproject coordination. As shown by this study, this requires competences related to acting as a mediator and providing resources that facilitate both single and multi-project coordination among main contractors. Another managerial implication is that initiators of a TPL-operated CLS need to be aware of the coopetitive tensions that arise in multi-project contexts and how they may manifest in horizontal relationships.

In this study, the IMP perspective – specifically the ARA model – was an appropriate analytical tool to capture the ways in which contractors engaged in horizontal relationships, and in relationships with the TPL provider. This was done by tracing the activities and resources to which their interactions related, where coordination of logistics and production activities are examples of the latter and coordination meetings and stage coordinators examples of the former, which in turn signified their relationships. In addition, the concept of coopetition assisted in arguing for both the competitive and cooperative elements of those interactions.

This study is limited to a single case study and only analyses a late phase of a stage that consisted mostly of interior works, during which the main contractors interacted with each other (and other projects) less compared to earlier phases. Further studies of how main contractors in a multi-project context interact and how TPL providers influence interorganisational relationships are therefore needed. We suggest that such studies follow a stage from the beginning, when foundations and frames are being built and the contractors and TPL provider have to coordinate large deliveries and production processes daily. This would permit a much greater insight into how interorganisational relationships evolve over the course of the project. Furthermore, studies on coopetitive tensions between contractors and TPL providers are needed. While most previous studies indicate that there are large tensions in such forced relationships, this study indicates that it is possible to have a rather neutral relationship between contractors and TPL providers. An interesting aspect to further investigate is what implications this has on the benefits and success of a CLS.

References

- Agapiou, A., et al., 1998. The role of logistics in the materials flow control process. Construction management and economics, 16 (2), 131–137.

- Akintoye, A., McIntosh, G., and Fitzgerald, E., 2000. A survey of supply chain collaboration and management in the UK construction industry. European journal of purchasing & supply management, 6 (3–4), 159–168.

- Allen, J., et al., 2014. A review of urban consolidation centres in the supply chain based on a case study approach. Supply chain forum: an international journal, 15 (4), 100–112.

- Arantes, A., Ferreira, L.M.D.F., and Costa, A.A., 2015. Is the construction industry aware of supply chain management? The Portuguese contractors’ perspective. Supply chain management: an international journal, 20 (4), 404–414.

- Behera, P., Mohanty, R.P., and Prakash, A., 2015. Understanding construction supply chain management. Production planning & control, 26 (16), 1332–1350.

- Bengtson, A., and Håkansson, H., 2007. Introducing “old” knowledge in an established user context: How to use wood in the construction industry. In: H. Håkansson, ed. Knowledge and innovation in business and industry: the importance of using others. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 54–78.

- Bengtsson, M., and Kock, S., 2000. “Coopetition” in business networks—to cooperate and compete simultaneously. Industrial marketing management, 29 (5), 411–426.

- Bengtsson, M., and Kock, S., 2014. Coopetition—Quo vadis? Past accomplishments and future challenges. Industrial marketing management, 43 (2), 180–188.

- Brandenburger, A.M., and Nalebuff, B.J., 1996. Co-opetition. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group.

- Bygballe, L.E., Håkansson, H., and Jahre, M., 2013. A critical discussion of models for conceptualizing the economic logic of construction. Construction management and economics, 31 (2), 104–118.

- Bygballe, L.E., and Ingemansson, M., 2014. The logic of innovation in construction. Industrial marketing management, 43 (3), 512–524.

- Bygballe, L.E., Jahre, M., and Swärd, A., 2010. Partnering relationships in construction: a literature review. Journal of purchasing and supply management, 16 (4), 239–253.

- Chen, M.-J., 2008. Reconceptualizing the competition— cooperation relationship: a transparadox perspective. Journal of management inquiry, 17 (4), 288–304.

- Cox, A., and Ireland, P., 2002. Managing construction supply chains: the common sense approach. Engineering, construction and architectural management, 9 (5/6), 409–418.

- Dubois, A., and Fredriksson, P., 2008. Cooperating and competing in supply networks: making sense of a triadic sourcing strategy. Journal of purchasing and supply management, 14 (3), 170–179.

- Dubois, A., and Gadde, L.-E., 2000. Supply strategy and network effects — purchasing behaviour in the construction industry. European journal of purchasing & supply management, 6 (3–4), 207–215.

- Dubois, A., and Gadde, L.-E., 2002a. The construction industry as a loosely coupled system: implications for productivity and innovation. Construction management and economics, 20 (7), 621–631.

- Dubois, A., and Gadde, L.-E., 2002b. Systematic combining: an abductive approach to case research. Journal of business research, 55 (7), 553–560.

- Dubois, A., Hulthén, K., and Sundquist, V., 2019. Organising logistics and transport activities in construction. The international journal of logistics management, 30 (2), 620–640.

- Easton, G., 2010. Critical realism in case study research. Industrial marketing management, 39 (1), 118–128.

- Ekeskär, A., and Rudberg, M., 2016. Third-party logistics in construction: the case of a large hospital project. Construction management and economics, 34 (3), 174–191.

- Engwall, M., and Jerbrant, A., 2003. The resource allocation syndrome: the prime challenge of multi-project management? International journal of project management, 21 (6), 403–409.

- Eriksson, P.E., 2008. Procurement effects on coopetition in client-contractor relationships. Journal of Construction engineering and management, 134 (2), 103–111.

- Exploateringskontoret, 2016. Bygglogistikcenter i Norra Djurgårdsstaden – delavstämning, Stockholm: Exploateringskontoret Stockholm stad.

- Fadiya, O., et al., 2015. Decision-making framework for selecting ICT-based construction logistics systems. Journal of engineering, design and technology, 13 (2), 260–281.

- Fernandez, A.-S., Le Roy, F., and Gnyawali, D.R., 2014. Sources and management of tension in co-opetition case evidence from telecommunications satellites manufacturing in Europe. Industrial marketing management, 43 (2), 222–235.

- Flyvbjerg, B., 2006. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative inquiry, 12 (2), 219–245.

- Fredriksson, A., Janné, M., and Rudberg, M., 2021. Characterizing third-party logistics setups in the context of construction. International journal of physical distribution & logistics management, 51 (4), 325–349.

- Gadde, L.-E., Huemer, L., and Håkansson, H., 2003. Strategizing in industrial networks. Industrial marketing management, 32 (5), 357–364.

- Håkansson, H., 1987. Industrial technological development: a network approach. New York: Croom Helm.

- Håkansson, H., et al., 2009. Business in networks. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Håkansson, H., Havila, V., and Pedersen, A.-C., 1999. Learning in networks. Industrial marketing management, 28 (5), 443–452.

- Håkansson, H., and Snehota, I., 1995. Developing relationships in business networks. London: Routledge.

- Håkansson, H., and Snehota, I., 2017. No business is an island: making sense of the interactive business world. Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

- Halinen, A., and Törnroos, J., Å 2005. Using case methods in the study of contemporary business networks. Journal of business research, 58 (9), 1285–1297.

- Havenvid, M.I., 2015. Competition versus interaction as a way to promote innovation in the construction industry. IMP journal, 9 (1), 46–63.

- Havenvid, M. I., Bygballe, L. E., and Håkansson, H., 2019. Innovation among project islands: a question of handling interdependencies through bridging. In: M.I. Havenvid, Å. Linné, L.E. Bygballe and C. Harty, eds. The connectivity of innovation in the construction industry. London: Routledge.

- Havenvid, M.I., Håkansson, H., and Linné, Å. 2016b. Managing renewal in fragmented business networks. IMP journal, 10 (1), 81–106.

- Havenvid, M.I., et al., 2016a. Renewal in construction projects: tracing effects of client requirements. Construction management and economics, 34 (11), 790–807.

- Hedborg Bengtsson, S., 2019. Coordinated construction logistics: an innovation perspective. Construction management and economics, 37 (5), 294–307.

- Hedborg, S., Eriksson, P.-E., and Karrbom Gustavsson, T., 2020. Organisational routines in multi-project contexts: coordinating in an urban development project ecology. International journal of project management, 38 (7), 394–404.

- Hedborg, S., and Karrbom Gustavsson, T. 2020. Developing a neighbourhood: exploring construction projects from a project ecology perspective. Construction management and economics, 38 (10), 964–976.

- Janné, M., and Fredriksson, A., 2019. Construction logistics governing guidelines in urban development projects. Construction innovation, 19 (1), 89–109.

- Janné, M., and Rudberg, M., 2020. Effects of employing third-party logistics arrangements in construction projects. Production planning & control, 1–13.

- Karrbom Gustavsson, T., 2018. Liminal roles in construction project practice: exploring change through the roles of partnering manager, building logistic specialist and BIM coordinator. Construction management and economics, 36 (11), 599–610.

- Keung, C., and Shen, L., 2017. Network strategy for contractors’ business competitiveness. Construction management and economics, 35 (8–9), 482–497.

- Lindén, S., and Josephson, P.E., 2013. In-housing or out-sourcing on-site materials handling in housing? Journal of engineering, design and technology, 11 (1), 90–106.

- Marasco, A., 2008. Third-party logistics: a literature review. International journal of production economics, 113 (1), 127–147.

- Mariani, M.M., 2007. Coopetition as an emergent strategy: empirical evidence from an Italian consortium of opera houses. International studies of management & organization, 37 (2), 97–126.

- Miller, C.J.M., Packham, G.A., and Thomas, B.C., 2002. Harmonization between main contractors and subcontractors: a prerequisite for lean construction? Journal of construction research, 3 (1), 67–82.

- Raza-Ullah, T., 2020. Experiencing the paradox of coopetition: a moderated mediation framework explaining the paradoxical tension–performance relationship. Long range planning, 53 (1), 101863.

- Raza-Ullah, T., Bengtsson, M., and Kock, S., 2014. The coopetition paradox and tension in coopetition at multiple levels. Industrial marketing management, 43 (2), 189–198.

- Selviaridis, K., and Spring, M., 2007. Third party logistics: a literature review and research agenda. The international journal of logistics management, 18 (1), 125–150.

- Sundquist, V., Gadde, L.-E., and Hulthén, K., 2018. Reorganizing construction logistics for improved performance. Construction management and economics, 36 (1), 49–65.

- Thunberg, M., Rudberg, M., and Karrbom Gustavsson, T., 2017. Categorising on-site problems: a supply chain management perspective on construction projects. Construction innovation, 17 (1), 90–111.

- Tidström, A., 2008. Perspectives on coopetition on actor and operational levels. Management research: journal of the Iberoamerican academy of management, 6 (3), 207–217.

- Tidström, A., 2014. Managing tensions in coopetition. Industrial marketing management, 43 (2), 261–271.

- Vrijhoef, R., and Koskela, L., 2000. The four roles of supply chain management in construction. European journal of purchasing & supply management, 6 (3–4), 169–178.

- Ying, F., Tookey, J., and Seadon, J., 2018. Measuring the invisible. Benchmarking: an international journal, 25 (6), 1921–1934.