Abstract

This paper examines the gap between macro-level calls for innovation and the micro-level enactment, by exploring the discrepancies between a public client’s pursuit of innovation and the actions taken at the project level. Through empirical analysis of four infrastructure operation and maintenance projects, we identify discrepancies within and between procurement strategies and project-level practices. Taking a strategy-as-practice perspective, our study shows how procurement strategies are adapted and enacted by inter-organizational project actors, shedding light on why macro-level innovation intent may not translate into expected outcomes at the project level. Our findings underscore the importance of aligning macro-level directives with micro-level actions to drive innovation in construction projects effectively. This research contributes to a better understanding of the dynamics shaping innovation in construction projects, highlighting the critical role of procurement strategies in bridging macro and micro contexts to achieve sustainable development goals.

Introduction

Innovation has an important role to play in European efforts to address societal challenges, such as climate change (European Commission, Citation2022). Therefore, the European Union (EU) is calling for its member states to use public procurement to stimulate innovation (European Commission, Citation2021). Every year, approximately €2 trillion is spent on public procurement of works, goods, and services in the EU, corresponding to about 14% of the gross domestic product of the EU’s member states (European Court of Auditors, Citation2023). Due to its significance in managing public resources, public procurement is seen as a strategic and powerful tool to drive innovation for sustainable development and to handle other societal challenges (OECD, Citation2023).

Public procurement rules are designed by the EU and implemented by the public agencies of its member states. Therefore, public organizations within the EU face political pressure to drive sustainable development through innovation (Hartmann et al., Citation2008; Hjelmar, Citation2021). Since the construction industry accounts for approximately 40% of global energy and process-related CO2 emissions (United Nations Environment Programme, Citation2022) public construction clients are important actors in efforts to reach sustainability goals.

Indeed, prior research has highlighted the important role of public clients as promotors of innovation in construction (e.g. Håkansson and Ingemansson, Citation2013; Vass and Karrbom Gustavsson, Citation2017; Kuitert et al., Citation2019; Lindblad and Karrbom Gustavsson, Citation2021; Larsson et al., Citation2022). Public construction clients develop strategies to promote innovation at the project level. Top-down strategies that client parent organizations apply to foster innovation in inter-organizational construction projects are exercised through procurement (Blayse and Manley, Citation2004; Leiringer et al., Citation2009; Eriksson, Citation2017; Hedborg Bengtsson et al., Citation2018; Carbonara and Pellegrino, Citation2020), providing project managers with formal tools to promote supplier-led innovation.

Over the last decades, the process of projectification (Midler, Citation1995) has had major impacts on public sectors (Godenhjelm et al., Citation2015; Fred, Citation2020), outsourcing work and turning public agencies into clients managing inter-organizational projects. Through public sector projectification and outsourcing, work that was once performed in a continuous fashion with in-house resources of the public agency is now organized into projects with public clients and private suppliers. One such example is the operation and maintenance (O&M) of public infrastructure (Nilsson Vestola et al., Citation2021). Outsourcing work through public procurement is expected to increase efficiency, effectiveness, and potentially innovation (Håkansson and Axelsson, Citation2020). However, since public procurement is regulated by laws, such as the Swedish Public Procurement Act (see Konkurrensverket, Citation2017), strategic public outsourcing is challenging (Håkansson and Axelsson, Citation2020).

Since projects are organizationally embedded (Engwall, Citation2003), innovation in project-based contexts relies on processes within the parent organizations as well as at the project level (Gann and Salter, Citation2000). The parent organizations are permanent structures in the project’s macro context, where the client parent organization governs and finances the project while the contractor parent organization provides it with human and material resources (Winch, Citation2014). This linkage between the project and its parent organizations complicates innovation in construction (Dubois and Gadde, Citation2002; Crespin-Mazet et al., Citation2021).

By applying a strategy-as-practice perspective, strategic management scholars have increasingly viewed strategies as something that an organization’s members do, instead of something that the organization has (Jarzabkowski, Citation2004; Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2007). This doing of strategy occurs through situated practice in micro-contexts, positioned in a macro-context that provides shared structures of action (Jarzabkowski, Citation2004). In a strategy-as-practice approach, micro (e.g. project) and macro (e.g. parent organizations, governmental, EU) strategy levels are regarded as interrelated, connecting the doings of individuals with wider organizational structures (Whittington, Citation2006; Vaara and Whittington, Citation2012). In their situated doing of strategy, actors may adapt available practices to the circumstances of their micro context (Jarzabkowski, Citation2004).

Based on the above line of reasoning, our premise is that there is a need to integrate strategic intent and execution in project-based settings (Artto et al., Citation2008a; Söderlund and Maylor, Citation2012). We argue that there is a gap in the construction innovation literature regarding how construction clients’ pursuit of innovation is enacted at the project level. Increasing this understanding is especially important for public clients, given their role in promoting innovation to contribute to sustainable development. Therefore, our purpose is to bridge the gap between the macro-level call for innovation and the micro-level enactment. By choosing infrastructure operation and maintenance as the empirical context, we gain a better understanding of how project organizing of continuous work affects public clients’ abilities to enhance innovation. The research has been guided by the following research question: What discrepancies can be found between the public client parent organization’s pursuit of innovation and the project-level enactment, and what are the reasons behind these discrepancies?

This paper is based on a longitudinal qualitative case study of four road O&M projects procured by Sweden’s largest infrastructure client: the Swedish Transport Administration (STA). For two of the studied projects, the STA developed and implemented a new procurement strategy, explicitly aiming to foster innovation. O&M projects represent a continuous type of project in the construction industry, partly because their goal is to preserve assets rather than transition and partly because of their process-like routinized tasks and long-term relations (Nilsson Vestola et al., Citation2021; Nilsson Vestola and Eriksson, Citation2023). Their continuity creates favourable conditions for longitudinal strategizing activities at the project level, and thus beneficial contexts for studying the process of micro-level adaption and enactment of macro-intended practices.

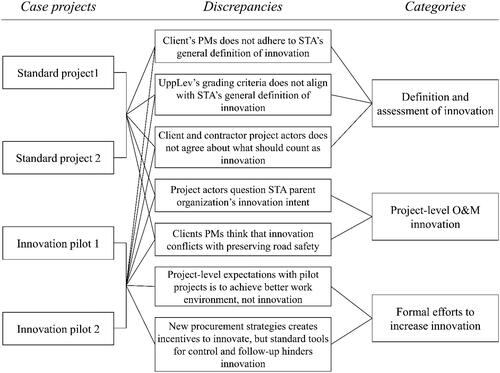

Calls have been made to further integrate social science with construction management, both to add value to our complex research field and to extend the impact of our research by deepening its connections with the world outside (Koch et al., Citation2019; Volker, Citation2019). We respond to this call by taking a practice approach (e.g. Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2007; Feldman and Orlikowski, Citation2011; Vaara and Whittington, Citation2012). This approach enables identifying discrepancies between macro-level calls for innovation and micro-level enactment, and analyzing the reasons behind them. In total, seven discrepancies were identified, related to the three categories of Definition and assessment of innovation, Project-level O&M innovation, and Formal efforts to increase innovation. The article’s key contribution is demonstrating how a public client’s innovation strategies are interpreted across different parts of the client organization including the project level. This article adds to the construction innovation literature by highlighting the critical importance of aligning procurement strategies with one another as well as with the everyday work in project contexts.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. First, we introduce the theoretical background of our study, presenting our strategy-as-practice perspective on innovation in the project-based context of construction, ending with a summary of previous research on the organizational form of O&M projects. The research methods as well as an overview of the empirical context are described. Then we go on to present the client parent organization, before describing our empirical findings, focusing on the macro-micro discrepancies and the reasons behind them. In the discussion section, the empirical findings are interpreted and described in relation to prior literature. In the last section of the paper, conclusions are drawn regarding the article’s theoretical and practical implications, as well as limitations and suggestions for further research.

Theoretical background

A strategy-as-practice perspective in project-based contexts

Through the work of Mintzberg (Citation1978) and Mintzberg and Waters (Citation1985), strategic management scholars began to problematize the view that strategy solely consists of top managements’ deliberate strategic plans. Mintzberg (Citation1978) introduced the concept of emerging strategies, which are not planned and realized despite, or in the absence of, intentions (Mintzberg and Waters, Citation1985). This fostered interest in more peripheral parts of organizations’ strategic activities, a tradition that has continued through strategy-as-practice.

In a strategy-as-practice approach, strategy is defined as a “situated, socially accomplished activity” (Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2007, p. 7) and viewed as something that an organization’s members do, rather than something that the organization has (Jarzabkowski, Citation2004; Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2007). Thus, the process of strategizing is important. Vaara and Whittington (Citation2012) define this as all activities “that lead to the emergence of organizational strategies, conscious or not” (p. 287), created through the actions and interactions of practitioners and the practices that they draw upon (Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2007).

Practice theory rejects dualisms, instead encouraging the integration of polarized concepts (Feldman and Orlikowski, Citation2011). Hence, a strategy-as-practice perspective facilitates analysis of connections between micro- and macro-level strategizing (Whittington, Citation2006; Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2007). While the macro-level strategizing involves activities in high-level structures or systems, the micro-level captures the importance of lower-level human agency (Johnson et al., Citation2007; Seidl and Whittington, Citation2014).

From a planning perspective, projects are means through which the parent organization can implement its strategies (Artto et al., Citation2008b). However, viewing projects as temporary organizations instead of plans (Lundin and Söderholm, Citation1995; Packendorff, Citation1995) attributes projects with the characteristics of other types of organizations. Hence, a stream of project research has contested the purely top-down perspective of strategy in which a project is viewed as the “parent organization’s obedient servant” (Artto et al., Citation2008a, p. 4) and as a site where strategy is only executed (Söderlund and Maylor, Citation2012). A top-down perspective implicitly neglects how strategies are implemented and adapted at the project level. To increase the chances of the macro-practices being enacted as anticipated at the project level, project practices need to be acknowledged and the top-down initiatives need to be aligned with project practices (Löwstedt et al., Citation2018).

Taking a project perspective on strategic intent, the parent organizations of the involved project actors must be regarded as part of the project’s external environment (Artto et al., Citation2008a). Strategy implementation between different organizational levels has inherent tensions (Weiser et al., Citation2020) and in their local adoption, practitioners may adapt the macro practices in ways that diverge from the parent organization’s intentions (Jarzabkowski, Citation2004). In project-based contexts, there is thus a need to integrate strategy intention with strategy execution (Artto et al., Citation2008a; Söderlund and Maylor, Citation2012). This will further the understanding of how strategy implementation processes unfold as a result of the interplay between strategy conceptualizing and enactment between different organizational levels (Weiser et al, Citation2020). A strategy-as-practice perspective may contribute to the understanding of innovation as the doings of individuals in a project-level micro context, in relation to macro-context intentions and expected outcomes.

A strategy-as-practice approach to innovation in construction projects

The top level of the macro-context of innovation strategies for construction projects managed by public clients encompasses supranational goals and regulations, which are expressed in European contexts in EU Directives. The EU public procurement directive defines innovation as helping to solve societal challenges through:

the implementation of a new or significantly improved product, service or process, including but not limited to production, building or construction processes, a new marketing method, or a new organisational method in business practices, workplace organisation or external relations inter alia with the purpose of helping to solve societal challenges

(EU Directive 2014/24, p. 11).

In construction, public clients can shape both formal and informal innovation practices of the actors (Vass and Karrbom Gustavsson, Citation2017). However, the literature on public procurement and innovation has downplayed the multi-dimensional and complex nature of both project-level innovation and public procurement, thereby limiting the possibilities to meaningfully inform public procurement strategies in practice (Uyarra and Flanagan, Citation2010). Bygballe and Ingemansson (Citation2011) concluded that there is a gap between public policy and industry views on innovation in Swedish construction settings, implying a need for further exploration of public construction client’s strategies (e.g. procurement strategy) to increase innovation.

Loosemore (Citation2015) notes that despite a widespread belief that the construction industry is not highly innovative, actors involved in construction projects participate in creative problem-solving activities on a daily basis. These incremental types of creative processes are often reactive responses to unanticipated situations. This has been highlighted as the clearest source of innovation in the construction industry, due to the uncertainty and complex nature of each unique solution (Ozorhon, Citation2013; Loosemore, Citation2015; Eriksson et al., Citation2019). Hence, there are discrepancies between organizational-level calls for proactive innovation and a project-level focus on reactive incremental innovation (Eriksson et al., Citation2017). Partly because the linkage between the project’s permanent and temporary contexts offers a problematic situation for innovation in construction (Dubois and Gadde, Citation2002; Crespin-Mazet et al., Citation2021).

Operation & maintenance projects within the construction industry

In the construction industry, O&M activities consist of ongoing processes throughout the life cycle of a building or infrastructure asset. Historically, the Swedish Road Administration (which later merged with the Swedish Rail Administration, forming the STA) was responsible for the operation and maintenance of the Swedish public road system, using in-house resources in a process-like manner. In accordance with the broader projectification of public administration (Sjöblom et al., Citation2013; Fred, Citation2015) these activities have been outsourced through time-limited contracts that are open for competition and organized as projects including both client and contractor representatives. Thus, projectification has not only affected time-limited, specific efforts.

Nilsson Vestola et al. (Citation2021) presented an overview of the temporary and permanent aspects of project organizing in road O&M projects, applying the concepts (time, task, team, and transition) proposed by Lundin and Söderholm (Citation1995). The authors found that O&M projects include a mixture of both temporary and permanent aspects of organizing. The O&M projects thereby represent organizational units with resemblance to both short-term new-build projects and more ongoing and long-term procedures. In a study of outcomes of partnering on various types of maintenance projects, Nyström (Citation2008) did not consider the variable of time to be applicable for O&M projects, illustrating their high degree of temporal continuity. The tasks of O&M projects create continuity since they are mostly repetitive and performed in an ongoing process aiming for preservation of assets, thereby offering better opportunities to reuse and diffuse innovation than in new-build projects (Nilsson Vestola et al., Citation2021). Through O&M projects, the inter-organizational project team members can develop long-term relationships due to participation in multiple common projects (Nilsson Vestola et al., Citation2021; Nilsson Vestola and Eriksson, Citation2023).

Since O&M projects have a more continuous nature than new-build projects, they may enable more longitudinal strategy emergence at the project level than one-off construction projects (Nilsson Vestola and Eriksson, Citation2023). Therefore, they provide a highly suitable context for fulfilling our aim of increasing the understanding of the gap between the macro-level pursuit of innovation and the micro-level enactment.

Research method

Case study selection and description

To explore the discrepancies between a public construction client’s pursuit of innovation and the actions taken in the project’s micro context, we draw on a longitudinal case study of four O&M projects. O&M projects are carried out through contracts that are four to six years long (four years with one or two option years) and include, for example, winter maintenance (e.g. snow ploughing), maintenance of paved and unpaved roads, and exchanging damaged road equipment. The Swedish public road system is divided into approximately 110 geographical areas, each outsourced to an external contractor with the responsibility of carrying out the prescribed O&M activities.

To further develop innovation possibilities in its road O&M projects, the STA procured two “innovation pilots” in the winter of 2017/2018. The innovation pilots were formulated by the STA to encourage project-level innovation through a new development-promoting procurement strategy. The longitudinal case study of four O&M projects includes the two innovation pilot projects (IP1 and IP2) and also two comparable standard road O&M projects (SP1 and SP2) in order to increase the study’s analytical power and thereby enable more robust theoretical implications (Eisenhardt and Graebner, Citation2007). Including both the pair of innovation pilot projects and the pair of standard projects in the study enabled us to capture STA’s increased and clarified innovation intent in the innovation pilots, and the related project-level actions, compared to “standard conditions.”

O&M projects have beneficial conditions for longitudinal strategy emergence at the project level (Nilsson Vestola and Eriksson, Citation2023), and the two innovation pilots (IP1 and IP2) were also subject to stronger top-down pressure. Thus, the latter were extreme cases (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006) that could potentially provide new insights and abundant information about the interrelations between construction clients’ pursuit of innovation and project-level enactment.

Data collection

The four projects were followed through a longitudinal case study during the years 2018–2022. The O&M projects all started in 2018, thus we had the chance to follow them in real-time from the beginning. Empirical data were gathered through interviews, observations, and document studies. The individuals participating in the research are viewed as informants of how a construction client’s pursuit of innovation is enacted at the project level. The study is therefore not on the individuals per se, but rather their patterned activities about innovation. Thus, adhering to the Swedish law on ethics in research on human beings, the study has not been subject to an ethical review. The primary data collection was three rounds of semi-structured interviews (30 interviews in total), with managers from both the client organization (regional and project managers from the maintenance department) and contractor organizations (regional and site managers), see for interviewees.

Table 1. Summary of interviewees.

The three rounds of interviews focused on different themes. The first round focused on the nature of the O&M projects (e.g. content, organization, complexity), since we understood them as being a quite different type of project (compared to new-built) in the construction context. In the second round, we sought to capture how the project teams addressed innovation (e.g. methods, collaboration). Finally, in the third round, the focus was on innovation outcomes and assessment (e.g. type of innovation, purpose of innovation). All interviews were semi-structured, allowing the respondents to elaborate on their answers. With permission from the interviewees, the interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The research focus evolved as the study progressed, which is reflected in the different focuses of the interview rounds as well as in the number of interviews performed in each round. Another reason for the lower number of interviews in the third interview round was the exclusion of regional managers. The regional managers had given their view of the nature of the O&M projects and their conditions for innovation, in the first and second rounds of interviews. As they did not operate in the projects on a daily basis, it was considered rather redundant to include them in the third round of interviews as well.

Further, observations were recorded by taking continuous field notes during collaboration and site meetings (15 meetings in total). Through the observations of project team members’ actions and interactions, we obtained firsthand information about the project-level activities. This enabled us to record practices as patterns of action. These activities and practices of interest were then included in the interview guide. Thus, while the observations provided an understanding of what the project team members were doing, the interviews provided deeper explanations of their actions and interactions.

As a complement to the interviews and observations, documents were collected and studied. The documents included various kinds of texts related to STA’s overall missions, organization, management, strategies, and directives as well as documents specifically related to the four projects, e.g. protocols from meetings, specifications, procurement documents and contracts. The documents provided additional knowledge about the client organization’s macro-level strategizing (expressed explicitly and formally) as well as a retrospective understanding of the doings in the studied projects, i.e. the tacit and informal innovation practices that evolved in the projects.

Data analysis

We began our analysis by applying the descriptive narrative approach proposed by Langley (Citation1999), constructing detailed case stories from the raw data. The interview transcripts, field notes and document material were used to create chronologies for each of the four case projects separately. The objective was to structure and summarize our gathered data on how the discrepancies between the client parent organization’s pursuit of innovation and the project-level enactment unfolded.

In the first round of coding, we aimed to identify how the public client parent organization’s pursuit of innovation was manifested (document material) and interpreted (interview transcripts and field notes) at the project level. In the second round of coding, we focused on identifying the project-level actions associated with innovation. The actions discerned were the actions of innovation related to the formally expressed definition in the document material. This also included actions that were intended for innovation but that failed to be realized. The interview transcripts and meeting protocols provided us with retrospective second-hand accounts of these actions, while our field notes had captured the project actors’ actions in real-time. We then analyzed these codes, looking for discrepancies between intent and enactment. This resulted in seven identified discrepancies, as shown in . In a third round of coding, we identified the reasons behind these discrepancies, realizing that some of the reasons were rooted in discrepancies within the same organizational level. To explain the discrepancies between the public client parent organization’s pursuit of innovation and the project-level enactment, our analysis needed to include discrepancies related to innovation both within and between organizational levels. Having identified the reason behind the seven discrepancies, these reasons were used to group the discrepancies into the three categories of Definition and assessment of innovation, Project-level O&M innovation, and Formal efforts to increase innovation. The findings section of this paper is structured according to these three categories.

Description of the client parent organization and its strategies for innovation

Since Sweden is a member of the EU, the policies of the Swedish government and parliament are influenced by the EU. In turn, the decisions of the Swedish government and parliament affect STA’s explicit and formal innovation strategies. Early in the 2000s, the EU advanced its focus on public affairs as a means to increase innovation in Europe. For example, the European Council (Citation2005) and the European Commission (Citation2006) called on member states to renew their focus on public procurement for innovation. As the state is a major client in construction, construction was identified as one of the key industries.

Due to its large procurement volume, accounting for roughly 30% of the demand in the Swedish construction industry, STA has an important mission “in its role as client” to “increase productivity, efficiency and innovation in the markets for new-build, operations and maintenance” (SFS 2010:185, 2 § 10). In 2016, the Swedish government introduced a National Public Procurement Strategy (Regeringskansliet, Citation2016), reinforcing the EU’s and Swedish government’s top-down governance of STA, which included directives to use procurement to increase innovation in the construction markets. Since the Swedish government has given STA directives to use procurement to increase innovation in the supplier market, the STA parent organization aims for an increased rate of innovation at the project level.

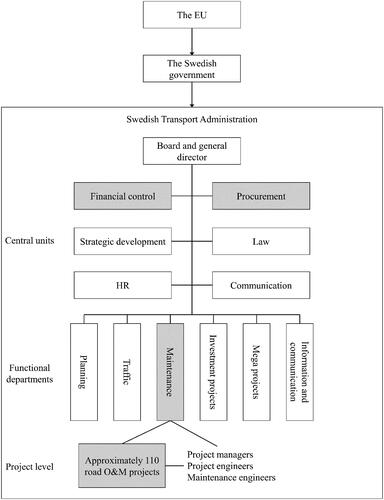

Since 2014, STA has initiated several activities to promote innovation in the supplier market. In , we have illustrated the organizational schedule of STA, highlighting the organizational units of interest in this study. The Procurement unit has introduced an assessment tool (UppLev) to assess suppliers’ project-level performance. The grading criteria for assessing innovation refers to “the use of new innovative methods that significantly improves time, cost and quality” and that are “judged to become new practice in the area and…in the industry” and “lead to great improvement in productivity”. Moreover, in 2016, the Procurement unit established a new organization-wide guideline for creating innovation-promoting projects, including the use of innovation-promoting measures in procurement and contract implementation. This guideline contains STA’s general definition of innovation which reads: “The use of a new or developed process, method, product, technical solution, service, model, etc. that creates added value” (Trafikverket, Citation2016). However, not all of the central units are focused on promoting innovation. The Financial control unit is responsible for the strategies for the financial governance of the projects. This unit’s focus is on time and costs, obliging the projects to act within annual budgetary constraints.

Figure 2. Organization schedule of STA.

Due to STA’s mission and long-term goal to develop strategies that promote supplier-led innovation, the Maintenance department initiated the two studied innovation pilot projects in their procurement of O&M projects in 2017, with contracts starting in 2018. The Maintenance department aimed to increase innovation through a development-promoting procurement strategy, with innovation goals defined in the innovation pilots’ contracts “to stimulate the use of innovative methods that improve, for example, security, time, costs, quality and accessibility”. The procurement strategy for the innovation pilots included three development-promoting aspects:

an innovation bonus, of (up to) 500 000 SEK/year, offered from year two of the contracts

a reward system based on the combination of a fixed price and cost reimbursement with a painshare/gainshare arrangement connected to a target cost

an extended version of the STA’s basic collaboration model, including co-location, open books, and collaboration workshops in the establishment phase.

The basic collaboration model, including the formation of a document with common measurable goals, plans for the collaboration process and conflict management, risk analysis, and continuous follow-up of the set goals, are set to be used in all STA’s projects including SP1 And SP2. The extended version of the collaboration model represented a large part of the development-promoting procurement strategy that was developed and implemented in IP1 and IP2.

It is important to note that the Maintenance department did not make any other changes in the innovation pilot projects’ contracts. For example, the pilot projects still had the same strict production requirements as all other of STA’s O&M projects. These requirements are strict with many detailed instructions for how the tasks should be conducted.

At the O&M project level, the client’s representative included a project manager, a project engineer, and a maintenance engineer, all belong to the Maintenance department. The project manager and project engineer were responsible for 1–3 O&M projects simultaneously, while the maintenance engineer supported all O&M projects within their region.

Findings

Definition and assessment of innovation

STA’s general definition of innovation (Trafikverket, Citation2016) allows for all types of developments, from incremental to more radical, to be viewed as innovations if they lead to added value. Adhering to this definition, we recorded examples of innovation in all four studied projects. Some were reactive solutions to deal with unanticipated situations such as extreme weather, others were incremental proactive developments to increase work safety and/or cost efficiency. We also recorded the spread of new technical solutions in multiple O&M projects as they were adopted by several contractors. However, in the case projects, these types of developments were not in general regarded as innovations by the project team members, mainly because the client’s project managers did not perceive them as innovations. The client’s project managers seemed to believe that an idea was not innovative if it had been previously implemented in O&M work, even if its use had not been previously proposed in their specific O&M project. They thought that it would have to be new to STA as a whole to be considered innovative, illustrating a discrepancy between the parent organization’s definition and the interpretation at the project level.

When comparing STA’s general definition of innovation with the grading criteria in UppLev, we can see that these do not fully align. While the definition allows for developed, as well as new, processes, methods, etc., the narrower grading criteria for innovation in UppLev require the use of new methods and are judged by their implication for the industry. UppLev’s grading criteria thereby excludes incremental innovations that only have effects on the ongoing project. Since UppLev is a tool for supplier assessment used by the client’s project managers annually, the grading criteria related to innovation is something that they come across and relate to in their role as project managers. Even though they might have seen the Procurement unit’s definition of innovation at some point, our findings show that the project managers did not work according to this definition. Hence, the client parent organization created a discrepancy between their general definition of innovation and the work carried out by their project managers, by being inconsistent in its definition of innovation.

The diverging definitions of innovation from the client parent organization led to confusion and a source of conflict between the project actors (client and contractor) at the project level. In IP2, efforts to innovate faltered during the project and the contractor did not receive any innovation bonuses. The client’s project manager thought that one reason for the innovation difficulties in the project was a lack of agreement between the client and contractor project team members regarding what innovation entailed:

But I don’t think we have a consensus about what innovation is. And actually, I have not really known either. Honestly, I still don’t know what is expected of this contract.

We’ve presented some innovations and after quite a long time we’ve been compensated for it. So we’ve worked some with that bit. … I guess I think it [the innovation bonus] is a good thing. But I think it’s somewhat fuzzy about what innovation actually is.

Project-level O&M innovation

The client project members seemed to think that their parent organization’s overall concept of innovation had been developed for temporary new-build projects, where the conditions for innovation greatly differed from those in the more continuous O&M conditions. Because of the differences between these two types of projects, the client’s representatives expressed that the parent organization’s directives had to be adjusted in accordance with the nature and everyday work of O&M. This was noted by the client’s regional manager in SP2:

We’re using a concept and that concept is the same from the government and out to our projects, there are no specifications along the way. Maybe there are some descriptions and explanations for what innovation means to STA but what innovation means for operation and maintenance… There’s no one who can say that it’s these kinds of things’ or “we imagine that it should be something like this.” It’s usually only a concept – “figure it out yourselves!,” and then it’s too difficult.

We’ve been operating and maintaining the roads for many, many, many years. And the contractors as well. … There aren’t a lot of time-saving things you can do.

I think it’s good to have pilot contracts where you test things, instead of just imposing them widely because then it all might go pear-shaped. We have a lot of contracts, and they are vital for society.

Formal efforts to increase innovation

Even though the Maintenance department initiated the innovation pilots with the aim of increasing project-level innovation, the project team members did not view production-related innovation as their primary aim when adopting the new ways of working. Rather, the project-level respondents saw these new types of contracts as a good effort by the client parent organization to introduce changes that could potentially reduce conflicts and improve the psychosocial work environment. This was noted by the client’s first regional manager for the innovation pilots:

From the management side [within the client parent organization], the aim was absolutely to try and come up with innovation and do different sorts of tests, while the contractors and project managers thought there had been a lot of conflicts and wanted to find ways of working that would not only lead to conflicts and arguments.

In this type of contract, it should be clearly stipulated that we’re allowed to depart from our standard production requirements. … But we haven’t changed anything because we aren’t allowed to. We have requirements to follow, standard requirements, so we get confined to the same thing. A bit more freedom in the contract – then, perhaps, there would be innovative ideas.

Discussion

The client’s pursuit of innovation is a result of the EU pushing for public clients to contribute to the solution of societal challenges by stimulating innovation through their procurements (EU Directive 2014/24). The types of innovation that the inter-organizational O&M project actors thought of as possible to achieve at the project level were reactive solutions and incremental proactive developments. This is in line with prior research noting that the most common source of innovation in construction is creative processes to solve unanticipated situations in daily work (Loosemore, Citation2015). Even though STA’s overall definition of innovation allowed these developments to be considered innovations, the client did not apply any strategies to utilize this innovation in any systematic way. Rather, the new ideas stayed within the project, or in some cases were spread between different geographical O&M areas by individual project managers, or by the contractors procured to conduct the O&M activities.

The EU public procurement directive defines innovation as “the implementation of a new or significantly improved product, service or process” (EU Directive 2014/24, p. 11). The project-bound innovations in the O&M projects may not be included in this definition. However, as a public client with nationwide responsibility for the operation and maintenance of Sweden’s public road system, STA has the ability to spread innovations across its O&M projects. As the O&M projects represent a more continuous type of project organizing, than short-term (new-built) construction projects, STA has the opportunity to work with continuous incremental developments towards highly set goals. Rather than expecting the development of innovations with industry implications in single O&M projects (as stated in the criteria for innovation in UppLev), the public client could strive for industry development through its procurements to develop the O&M work by systematically including incremental innovations.

Public clients are continuously recognized as important for innovation in construction (e.g. Håkansson and Ingemansson, Citation2013; Vass and Karrbom Gustavsson, Citation2017; Kuitert et al., Citation2019; Lindblad and Karrbom Gustavsson, Citation2021; Larsson et al., Citation2022). Our findings agree and contribute to this view by illustrating the role of public clients as recipients and carriers of innovation. This study highlights the possibilities of public clients to continuously build upon their contractor’s innovations, accumulating the effects.

The findings from the two standard O&M projects show how the client and contractor project actors considered it impossible to achieve substantial changes at the project level in standard O&M projects, and that radical innovations would have to be developed and tested in pilot projects. This supports prior research recognizing the conflicts between an organizational-level call for proactive innovation and the project-level focus on reactive innovation (Eriksson et al., Citation2017). Our findings provide a perspective on this, explaining that this project-level focus on reactive innovation is partly due to discrepancies between the public client parent organization’s different strategies for its projects. Our findings from the two pilot projects show how the client parent organization managed to create incentives for proactive innovation at the project level, but that these incentives were rather futile since the pilot projects still had the same barriers for innovation as standard projects. Thus, the findings show how investing in pilot projects will not be fruitful unless the public client manages to create a holistic strategy for proactive project-level innovation.

Comparing the standard O&M projects with the pilot projects, the findings from the pilot projects show how procurement practices may create incentives for innovation (Blayse and Manley, Citation2004; Eriksson, Citation2017; Hedborg Bengtsson et al., Citation2018; Carbonara and Pellegrino, Citation2020), but also highlight the importance of the client parent organization aligning its tools for control and follow-up with its aim of achieving supplier-led project-level innovation. While prior research has indicated that long maintenance responsibilities tend to spur contractors to engage in long-term innovation for sustainable development (Larsson et al., Citation2022), our findings show how the discrepancies between the client parent organization’s pursuit of innovation and project-level enactment can hamper the possibilities for inter-organizational project actors to innovate for long-term development.

For public clients, the linkage between projects and their parent organizations is central for outcomes of macro-level calls for innovation. With a strategy-as-practice approach, we acknowledge the everyday practices of the project actors as strategic, as they adapt the strategic intentions of the parent organizations (Jarzabkowski, Citation2004), thereby constructing innovation work and outcomes. An integrative view of strategy intention and enactment (Artto et al., Citation2008a; Söderlund and Maylor, Citation2012; Weiser et al., Citation2020) suggests that the process of strategy implementation should not be treated as a one-way mechanism. Our findings show the micro-level enactment of innovation in the light of the macro-level calls for innovation of societal meaning. A top-down perspective on this could have suggested project-level failure in answering the macro-level call. However, drawing on an integrative view, we recognize that the public client parent organization should adapt its strategies for innovation in response to the project-level enactment. This integrative view also acknowledges that parent clients’ innovation strategies may always be implemented and adapted in the local context of the project, thus complicating the possibility of foreseeing their outcomes. However, the first step of the client should be to ascertain that there are no top-down strategies that implicitly hinder innovation. For example, drawing on the findings of this study, public clients should ensure that tools for control and follow-up are aligned with their aim for innovation.

Conclusions

This paper offers insights into the gap between the macro-level call for innovation and micro-level enactment by analyzing the discrepancies between a public construction client’s pursuit of innovation and the actions taken at the project level. A strategy-as-practice approach (e.g. Jarzabkowski, Citation2004; Whittington, Citation2006; Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2007) enabled us to focus on the doings of the project actors, taking place in a context with macro-level intentions.

Our study adds to prior research on the role of public procurement for innovation in construction projects (Blayse and Manley, Citation2004; Leiringer et al., Citation2009; Eriksson, Citation2017; Hedborg Bengtsson et al., Citation2018; Carbonara and Pellegrino, Citation2020) by providing a project-level perspective of how procurement strategies are adapted and enacted by the inter-organizational project actors. This is a topic of both theoretical and practical relevance as it leads to a better understanding of why macro-level innovation intent by e.g. EU and public clients, does not necessarily lead to anticipated actions and outcomes in the micro project levels. We add to the knowledge of procurement and contracting strategies in the construction innovation literature by illustrating the values of an integrative view between parent organization procurement and project-level actions. At policy level, we suggest that the STA and other public clients should adjust their strategies to capture and spread the innovations taking place at the project level. Our findings also highlight the importance of ensuring that all procurement strategies that affect the possibilities for innovation align with each other.

This study has had a client perspective, by confining the analyzed macro-practices to the top-down initiatives of the client. However, parent organizational-level practices of contractor organizations also undoubtedly play an important role for innovation in construction. Thus, a potentially fruitful avenue for future research is to study the effects of contractors’ macro-practices, including contractor parent organization directives, on project-level innovation. Future research could also explore public clients’ role in spreading innovations across their projects, as this study has indicated the spreading of innovations as a potential way for public clients to work towards the macro-level call for innovation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editor and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments that guided the revisions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

There are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Data availability statement

Data associated with this paper cannot be made open due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy and confidentiality of research participants.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Artto, K., et al., 2008a. What is project strategy? International journal of project management, 26 (1), 4–12.

- Artto, K., et al., 2008b. Project strategy: strategy types and their contents in innovation projects. International journal of managing projects in business, 1 (1), 49–70.

- Blayse, A., and Manley, K., 2004. Key influences on construction innovation. Construction innovation, 4 (3), 143–154.

- Bygballe, L.E., and Ingemansson, M., 2011. Public policy and industry views on innovation in construction. The IMP journal, 5 (3), 157–171.

- Carbonara, N., and Pellegrino, R., 2020. The role of public private partnerships in fostering innovation. Construction management and economics, 38 (2), 140–156.

- Crespin-Mazet, F., et al., 2021. The diffusion of innovation in project-based firms – linking the temporary and permanent levels of organisation. Journal of business & industrial marketing, 36 (9), 1692–1705.

- Dubois, A., and Gadde, L.E., 2002. The construction industry as a loosely coupled system: implications for productivity and innovation. Construction management and economics, 20 (7), 621–631.

- Eisenhardt, K.M., and Graebner, M.E., 2007. Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Academy of management journal, 50 (1), 25–32.

- Engwall, M., 2003. No project is an island: linking projects to history and context. Research policy, 32 (5), 789–808.

- Eriksson, P.E., 2017. Procurement strategies for enhancing exploration and exploitation in construction projects. Journal of financial management of property and construction, 22 (2), 211–230.

- Eriksson, P.E., Larsson, J., and Szentes, H., 2019. Reactive problem solving and proactive development in infrastructure projects. Current trends in civil & structural engineering, 3 (2).

- Eriksson, P.E., Leiringer, R., and Szentes, H., 2017. The role of co-creation in enhancing explorative and exploitative learning in project-based settings. Project management journal, 48 (4), 22–38.

- EU Directive, 2014. Directive 2014/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on public procurement and repealing Directive 2004/18/EC. Available from: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2014/24/2024-01-01

- European Commission, 2006. Putting Knowledge into Practice: A broad-based Innovation Strategy for the EU [online] Available from: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/36fac83c-e34a-42fd-b5f9-71c5cd69240c

- European Commission, 2021. The strategic use of public procurement for innovation in the digital economy SMART 2016/0040 – Final Report. [online] Available from: https://www.euriphi.eu/wp-content/uploads/kk0221251enn.en_.pdf

- European Commission, 2022. A New European Innovation Agenda. [online] Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52022DC0332

- European Council, 2005. Brussels European Council 22 and 23 March 2005, Presidency Conclusions [online] Available from: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/84335.pdf

- European Court of Auditors, 2023. Public procurement in the EU: less competition for contracts awarded for works, goods and services in the 10 years up to 2021. Special report 28, 2023, Publications Office of the European Union. [online] Available from: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2865/04787

- Feldman, M., and Orlikowski, W., 2011. Theorizing practice and practicing theory. Organization science, 22 (5), 1240–1253.

- Flyvbjerg, B., 2006. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative inquiry, 12 (2), 219–245.

- Fred, M., 2015. Projectification in Swedish municipalities: a case of porous organizations. Scandinavian journal of public administration, 19 (2), 49–68.

- Fred, M., 2020. Local government projectification in practice – a multiple institutional logic perspective. Local government studies, 46 (3), 351–370.

- Gann, D.M., and Salter, A.J., 2000. Innovation in project based, service enhanced firms: the construction of complex products and systems. Research policy, 29 (7–8), 955–972.

- Godenhjelm, S., Lundin, R.A., and Sjöblom, S., 2015. Projectification in the public sector–the case of the European Union. International journal of managing projects in business, 8 (2), 324–348.

- Håkansson, H., and Axelsson, B., 2020. What is so special with outsourcing in the public sector? Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 35 (12), 2011–2021.

- Håkansson, H., and Ingemansson, M., 2013. Industrial renewal within the construction network. Construction management and economics, 31 (1), 40–61.

- Hartmann, A., Reymen, I.M.M.J., and van Oosterom, G., 2008. Factors constituting the innovation adoption environment of public clients. Building research & information, 36 (5), 436–449.

- Hedborg Bengtsson, S., Karrbom Gustavsson, T., and Eriksson, P.E., 2018. Users’ influence on inter-organizational innovation: mapping the receptive context. Construction innovation, 18 (4), 488–504.

- Hjelmar, U., 2021. The institutionalization of public sector innovation. Public management review, 23 (1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1665702

- Ingemansson Havenvid, M., et al., 2016. Renewal in construction projects: tracing effects of client requirements. Construction management and economics, 34 (11), 790–807.

- Jarzabkowski, P., 2004. Strategy as practice: recursiveness, adaptation and practices-in-use. Organization studies, 25 (4), 529–560.

- Jarzabkowski, P., Balogun, J., and Seidl, D., 2007. Strategizing: the challenges of a practice perspective. Human relations, 60 (1), 5–27.

- Johnson, G., et al., 2007. Strategy as practice – research directions and resources. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Koch, C., Paavola, S., and Buhl, H., 2019. Social science and construction – an uneasy and underused relation. Construction management and economics, 37 (6), 309–316.

- Konkurrensverket, 2017. Swedish public procurement act. [online] Available from: https://www.konkurrensverket.se/globalassets/dokument/informationsmaterial/rapporter-och-broschyrer/informationsmaterial/swedish-public-procurement-act.pdf

- Kuitert, L., Volker, L., and Hermans, M.H., 2019. Taking on a wider view: Public value interests of construction clients in a changing construction industry. Construction management and economics, 37 (5), 257–277.

- Langley, A., 1999. Strategies for theorizing from process data. Academy of management review, 24 (4), 691–710.

- Larsson, J., et al., 2022. Innovation outcomes and processes in infrastructure projects: a comparative study of design-build and design-build-maintenance contracts. Construction management and economics, 40 (2), 142–156.

- Leiringer, R., Green, S.D., and Raja, J.Z., 2009. Living up to the value agenda: the empirical realities of through‐life value creation in construction. Construction management and economics, 27 (3), 271–285.

- Lindblad, H., and Karrbom Gustavsson, T., 2021. Public clients ability to drive industry change: the case of implementing BIM. Construction management and economics, 39 (1), 21–35.

- Loosemore, M., 2015. Construction innovation: fifth generation perspective. Journal of management in engineering, 31 (6), 04015012.

- Löwstedt, M., Räisänen, C., and Leiringer, R., 2018. Doing strategy in project-based organizations: actors and patterns of action. International journal of project management, 36 (6), 889–898.

- Lundin, R.A., and Söderholm, A., 1995. A theory of the temporary organization. Scandinavian journal of management, 11 (4), 437–455.

- Midler, C., 1995. “Projectification” of the firm: the Renault case. Scandinavian journal of management, 11 (4), 363–375.

- Mintzberg, H., 1978. Patterns in strategy formation. Management science, 24 (9), 934–948.

- Mintzberg, H., and Waters, J., 1985. Of strategies, deliberate and emergent. Strategic management journal, 6 (3), 257–272.

- Nilsson Vestola, E., et al., 2021. Temporary and permanent aspects of project organizing. International journal of managing projects in business, 14 (7), 1444–1462.

- Nilsson Vestola, E., and Eriksson, P.E., 2023. Engineered and emerged collaboration: vicious and virtuous cycles. Construction management and economics, 41 (1), 79–96.

- Nyström, J., 2008. A quasi‐experimental evaluation of partnering. Construction management and economics, 26 (5), 531–541.

- OECD, 2023. Public procurement performance: a framework for measuring efficiency, compliance and strategic goals. OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 36. Paris: OECD Publishing. [online] Available from:

- Ozorhon, B., 2013. Analysis of construction innovation process at project level. Journal of management in engineering, 29 (4), 455–463.

- Ozorhon, B., Oral, K., and Demirkesen, S., 2016. Investigating the components of innovation in construction projects. Journal of management in engineering, 32 (3), 04015052.

- Packendorff, J., 1995. Inquiring into the temporary organization: new directions for project management research. Scandinavian journal of management, 11 (4), 319–333.

- Regeringskansliet, 2016. Nationella upphandlingsstrategin. Stockholm: Finansdepartementet. [online] Available from: https://www.regeringen.se/globalassets/regeringen/dokument/finansdepartementet/pdf/2016/upphandlingsstrategin/nationella-upphandlingsstrategin.pdf

- Seidl, D., and Whittington, R., 2014. Enlarging the strategy-as-practice research agenda: towards taller and flatter ontologies. Organization Studies, 35 (10), 1407–1421.

- SFS 2010:185, Förordning med instruktion för Trafikverket. [online] Available from: http://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svenskforfattningssamling/forordning-2010185-med-instruktionfor_sfs-2010-185

- Sjöblom, S., Löfgren, K., and Godenhjelm, S., 2013. Projectified politics – temporary organisations in a public context. Scandinavian journal of public administration, 17 (2), 3–12.

- Söderlund, J., and Maylor, H., 2012. Project management scholarship: Relevance, impact and five integrative challenges for business and management schools. International journal of project management, 30 (6), 686–696.

- Trafikverket, 2016. Riktlinje utvecklingsfrämjande åtgärder. TDOK, 2016, 0073.

- United Nations Environment Programme, 2022. Global status report for buildings and construction: towards a zero‑emission, efficient and resilient buildings and construction sector Nairobi.

- Uyarra, E., and Flanagan, K., 2010. Understanding the innovation impacts of public procurement. European planning studies, 18 (1), 123–143.

- Vaara, E., and Whittington, R., 2012. Strategy-as-practice: taking social practices seriously. The academy of management annals, 6 (1), 285–336.

- Vass, S., and Karrbom Gustavsson, T., 2017. Challenges when implementing BIM for industry change. Construction management and economics, 35 (10), 597–610.

- Volker, L., 2019. Looking out to look in: inspiration from social sciences for construction management research. Construction management and economics, 37 (1), 13–23.

- Weiser, A.K., Jarzabkowski, P., and Laamanen, T., 2020. Completing the adaptive turn: an integrative view of strategy implementation. Academy of management annals, 14 (2), 969–1031.

- Whittington, R., 2006. Completing the practice turn in strategy research. Organization studies, 27 (5), 613–634.

- Winch, G.M., 2014. Three domains of project organizing. International journal of project management, 32 (5), 721–731.