ABSTRACT

In this article we explore Covid-19 riskscapes across the African Great Lakes region. Drawing on fieldwork across Uganda and Malawi, our analysis centers around how two mobile, trans-border figures – truck drivers and migrant traders – came to be understood as shifting, yet central loci of perceived viral risk. We argue that political decision-making processes, with specific reference to the influence of Covid-19 testing regimes and reported disease metrics, aggravated antecedent geographies of blame targeted at mobile “others”. We find that using grounded riskscapes to examine localised renditions of risk reveals otherwise neglected forms of discriminatory discourse and practice.

KEYWORDS:

COVID-19 has scripted the globe as a space of risk, resembling what Beck (Citation1998) famously designates as “world risk society.” Lockdowns, masks, vaccination passes, and rapid testing have become universal strategies through which global society has attempted to navigate the risks of a contagious, planetary virus. Yet, despite the worldwide proliferation of these strategies, such practices have varied, generating particular impacts as they become embedded in heterogeneous cultures, politics and ecologies. Here, we take this heterogeneity seriously, moving beyond a reading of global risk, to consider risk perception in towns and cities within the African Great Lakes Region. In doing so, we work with the concept of “riskscapes” as a framework to understand localised COVID-19 responses. Accordingly, we offer both original empirical material from Uganda and Malawi, and an example of how riskscapes might be used to understand previously unexplored local responses to COVID-19.

Riskscapes can be understood as shifting landscapes of networked risk – both individual and collective – that shape the way people act (Müller-Mahn et al. Citation2020) Riskscapes shift over time, bring into play multiple histories, ideas and materialities and entangle local to global scales (Müller-Mahn Citation2015) Critically, riskscapes are never neutral, objectively defined, landscapes of risk perception, but are produced when both individuals and societies “inscribe knowledge and perception of potential risks and opportunities in space, and act accordingly” (Müller-Mahn et al. Citation2018:2) Working with COVID-19 riskscapes invites us to understand risk perceptions of a global pandemic as at once grounded in particular places, while operating across multiple geographies. Crucially, we argue for an appreciation of how data and statistics, which have dominated government mapping of COVID-19, interact with local politics of interpretation, serving to reproduce discriminatory discourse and exclusionary practice. Through this enquiry, we ultimately connect riskscapes to the production of “geographies of blame” – spatialised renditions of uneven accusation for viral spread and origins – which have so far received limited attention in COVID-19 analysis (Farmer Citation2006)

Examining the production of COVID-19 riskscapes in the African Great Lakes Region, we engage with an established network of researchers formed through a preexisting research project to produce local data from seven locations in Malawi and Uganda, stretching across a time-period of ten months from April 2020 to February 2021. Our study locations included dominant cities, secondary cities, border towns and rural villages, generating a rich, variegated geography of riskscape data in the region. Across these diverse places, we trace parallel exercises to integrate statistical and scientific data into local moral worlds, and memories of previous disease outbreaks. Cautious of homogenising diverse voices, we recognise that epidemiologists use the Great Lakes Region as a point of departure for its distinct ecological and socio-economic disease transmission dynamics.

The article is structured as follows. Firstly, we discuss the shift from global risk to grounded riskscapes. We then present our methodology, detailing the dynamics of our “remote” approach. Drawing on data from Uganda and Malawi, we then analyze how truck drivers and migrant traders emerged as central loci of perceived viral risk in a context of heterogeneous movement restrictions. We argue that such perceptions of risky sub-groups were produced at the intersection of national policies, including containment approaches, decisions around diagnostic testing and subsequent dissemination of statistics. As we show, these perceptions resonate with dynamics of previous viral riskscapes active in the region, thus re-activating geographies of blame and stigmatisation.

(Re) onstructing African Covid-19 riskscapes

COVID-19 and its accompanying sense of world risk has prompted an incessant tracking and tracing of pathogens and people, amounting to what Everts denotes as “the dashboard pandemic” – a view of the world shaped by “heat maps and aggregated numbers” (Citation2020:260) The World Health Organisation’s Coronavirus Disease Dashboard, with cases depicted on choropleth maps for the quick visual consumption of vast amounts of data, is perhaps the most-often referenced. This approach has enabled the rapid mapping of territories according to risk, orienting governmental action and containment at the national scale (Radil et al. Citation2021)

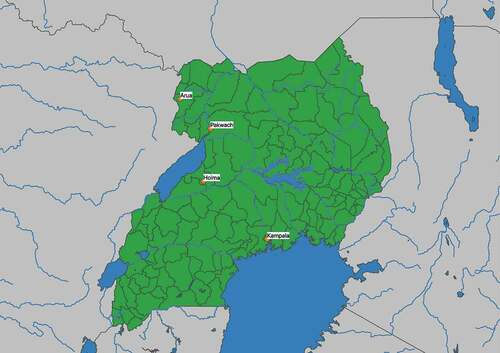

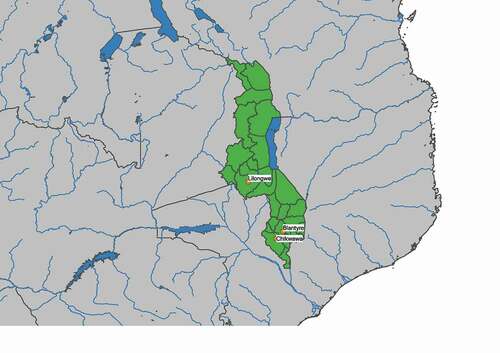

Yet, as elsewhere, in the countries that comprise the African Great Lakes region () health statistics are contested sets of information. Throughout 2020, COVID-19 surveillance was an expression of the political and economic challenges which structured its data collection, driven by shortages in diagnostic tests, testing sites and laboratory facilities (Renzaho Citation2021) The roll-out of COVID-19 testing was spatially uneven, initially often confined to airports and capital cities, and later border points and elected District Health Centers. As an indication, as of December 2020, of African’s 1.2 billion population, just 2.4 million had taken a COVID-test (Chitungo et al. Citation2020) In Uganda and Malawi, throughout this research period, COVID-19 tests were not cheaply available. International commentators were divided as to whether this was indicative of a “silent epidemic” or reflected actual realities of case numbers (Houreld and Lewis Citation2020)

Despite recognition of the partial view provided by statistics, popular discourses to explain COVID-19’s presence or absence in African countries readily circulated across the global riskscape. Continental generalisations commit the common error of homogenising Africa as a single space upon which discourses based on assumption, rather than evidence, can be merely projected. Scholars have highlighted the sensational and indeed, colonial construction that presented Africa as “disease-ridden” during the West African Ebola epidemic (Benton and Dionne Citation2015:223) In the time of COVID-19, dehumanising ideas about African “immunity” provide a similarly striking reproduction of what Mudimbe terms the “colonial library” – a set of representational orders that produce Africa as a “sign of absolute Otherness” (Citation1988:38)

Indeed, as the African continent seemingly avoided the impacts of COVID-19, which devastated European health systems in early-mid 2020, international forecasters invoked older Afropessimist tropes to explain this “good news.” Whilst COVID-19 was attached to Asian or Caucasian people in the global media, Africans were presupposed to be immune to the virus (Mock Citation2020) Embedded in a long history of the oppression of Black people, this kind of scientific racism, Vaughn et al. point out, is founded on the perception of ‘either racial propensity or “magical” immunity for illnesses due to [defective] biological differences’ (Citation2020:11) and ultimately reproduces a dynamic of Othering that has remained central to questions of Africa and disease. Alternative global discourses to explain COVID-19 risk in Africa have ranged from oversimplified predictions of complete collapse, fears of variants reported to have emerged in African countries, to surprise at the apparent adeptness of African governments to manage a novel virus (Gilbert et al. Citation2020).

Such explanations do damage by removing the possibility of discussing, for example, demographic factors, or the effects of decisive regional and national governance from African states in the face of a novel threat (Rosenthal et al. Citation2020) Like epidemiological data, generalisations obscure too an engagement with diverse realities of place-based riskscapes through which people themselves understand and respond to viral risk. Whilst dominant global tropes circulate around media outlets accessed across the continent, it would be strange if Africans understood COVID-19 solely through tropes which replicated Euro-American discourses. We thus argue that engaging with the notion of riskscapes allows us to challenge the views of both dashboard data and immunity discourses. As a framework which brings to bear multiple risks – viral and otherwise – each with their own rich histories and geographies, the notion of riskscapes offers a way of working against a tendency to write African perceptions of risk as simply a reproduction of global discourses (often emerging in Euro-America.) At the same time, it guards against a rendition which would suggest that risk perceptions of African citizens are totally different, thereby setting Africa apart from the world, as something Other (Mbembe Citation2001)

As risk perceptions unfolded in the borderscapes of the African Great Lakes Region, mobility emerged as a central way of designating risk. Our study thus speaks to a plethora of recent studies in Europe which have centered questions of mobility in their analyses of multi-scalar viral governance, impacts and inequalities (Bonaccorsi et al. Citation2020; Borkowski et al. Citation2021; Carteni et al. Citation2020; Glaeser et al. Citation2020; Lunstrum et al. Citation2021; Martin and Bergmann Citation2021; Montacute Citation2020; Shokouhyar et al. Citation1999) Whilst fear of mobility was an anxiety that characterised COVID-19 globally, concern was inflected by governmental policies which allowed certain people to continue particular types of work in medical and economic frontlines (Cevik et al. Citation2021; Taylor et al. Citation2020) Studies have linked European governments’ differential movement restrictions to the reproduction of viral risk along raced and classed lines, often serving to widen preexisting inequalities (Dobusch and Kreissl Citation2020) Yet, continental abstractions, rather than regionally specific portraits of risk, have pervaded analyses of COVID-19 risk throughout the African continent. Across our research sites in Uganda and Malawi, particular classes of people continued to engage in mobile, insecure forms of work at state peripheries throughout COVID-19 and its lockdowns. As in Europe, viral risk was unevenly distributed.

Many studies which focus on health risks fail to explore the social processes through which risk is calculated and how mobility is ascribed meaning in populations’ strategies of protection. In their differential implications, we find that movement restrictions were connected to both exposure of some to risk, and the production of fear of particular mobile classes, among those relatively fixed in space during lockdowns. Whilst the allocation of blame may be a feature of any epidemic/pandemic emergency, we are particularly interested in how citizens interpret evidence and calculate risk to produce “others”. If, as Adams (Citation2016) argues, data collection in emergency-mode tends to replicate existing social biases in data collection decisions, how do communities and local authorities engage with this data in politicised and divided contexts? If historical blame for affliction is reactivated (or evaded) we are interested in humanising the complex social processes through which populations make sense of evolving crisis, often through drawing on available science.

Through employing the notion of riskscapes, we offer space to consider such neglected understandings and practices central to COVID-19 viral risk perception, in turn re-centering meanings and practice, as global discourses are reworked locally. Whilst the concept of riskscapes has received limited application with reference to HIV/AIDS (Braun Citation2020) and Ebola (Ali et al. Citation2016; Gee and Skovdal Citation2017) it has not been applied to an analysis of COVID-19 perceptions in African countries. As a generative way of dealing with local specificity, shifting meanings and histories of diverse risk, the riskscape framework is brought into a cross-border region of Africa, with our findings grounded in various towns and cities where viral risk perceptions are produced and enacted in particular ways. Acknowledging the anxiety that often surrounds the movement of things, people and pathogens in any viral outbreak, we instead draw attention to the ways in which this anxiety plays in out in particular places, and the processes through which it becomes embedded in national politics, testing regimes and viral histories.

Remote research in the time of COVID-19

COVID-19 has demanded new ways of conducting research (Hensen et al. Citation2021; Richardson et al. Citation2021; Saberi Citation2020) The notion of remote research has emerged as the de facto reality for many, with scholars often tapping into official COVID-19 response activities. Yet, given the aforementioned contestations in the African Great Lakes region, there is a risk that research replicates the social biases within government-led data collections.

Significantly, any kind of employment of a riskscape framework requires engagement with particular places in-situ. In this way, we faced a significant challenge in reconciling our commitment to grounded specificity with the necessity of remote research. Inspired by this insistence on local meanings, we built on prior connections within the Localised Evidence and Decision-making (LEAD) project. We engaged with these preexisting networks creatively and pragmatically, in ways that were permitted through established institutional research clearance, and with respect to ethical considerations specific to a pandemic.

LEAD was a two-year project (2019–2021) driven by the need for localised evidence to support public health practitioners to deliver place-based, meaningful decisions. The project’s original focus was the transmission and control of schistosomiasis in the African Great Lakes Region. The project involved workshops with health practitioners, working at village, district and national levels across Malawi and Uganda, to build understandings of local evidence needs. When COVID-19 restrictions made further engagement impossible, we drew upon a network of established contacts, whose networks provided rich data from the various spaces in which they worked and lived.

Our method, in the first instance, included two extended questionnaires administered by research assistants who either lived or worked in the study sites in Uganda, (Kampala, Hoima, Pakwach and Arua) () and in Malawi, (Chikwawa, Blantyre and Lilongwe) () Research assistants administered the survey in their respective locations, engaging with their social and professional networks, thus ensuring that views were obtained from both communities and health workers. Recruitment was pragmatic, based on the freedoms allowed within contemporary movement/social distancing restrictions. The questionnaires thus included teachers, traders, healthcare providers, elderly populations and youth, as they could be accessed primarily as family, colleagues and neighbors.

The questions formed a tool to systemise the shifting landscape of interpretation, fears and evidence related to COVID −19. It consisted of 25 open-ended questions that sought to build local perspectives of COVID-19, covering care-seeking behaviors, community and personal protections, health information, access and provision of health services, and disease perceptions. The researchers administering the questionnaires offered their individual interpretations of local sentiments alongside specific quotes from community engagements. To capture changes over time, questionnaires were administered twice, at four- to six-week intervals between April and August 2020. Where possible, researchers engaged with the same sample of people at both intervals. Whilst this replication was not intended to produce comparable quantitative data, it was intended to capture changing perceptions among groups who had experienced common policy and viral shifts.

The questionnaire data were supplemented with in-depth phone interviews, which took place between November 2020 and February 2021. These reflected on existing research findings – which were both auto-ethnographic and community-based – and attempted to understand further shifts in perceptions within respective communities. We also engaged with social media and newspaper sources, to provide an overview of the public discourse operating both nationally and within localities.

Thus, data collected at two intervals, across seven spaces in Uganda and Malawi, alongside follow-up in-depth interviews, constituted the data used for the analyses presented here. Working in places at the margins of government-led public health, in the midst of movement restrictions, required creative ways of working with researchers. Whilst the viewpoint we provide is partial, it nonetheless offers a perspective on the COVID-19 pandemic which has thus far largely been side-lined in scholarship on experiences in African countries. In this way, our findings are not a definitive theorisation, but are a set of interpretive narratives that bring into view localised perceptions of pandemic risk.

As we elaborate below, our findings show that as cases were recorded in Uganda and Malawi, specific groups of people were inscribed with increased perceptions of viral risk, due in large part to their specific form of labor: truck drivers, migrant traders, sex workers, healers and health workers. Whilst many of these individuals were made vulnerable through their participation in uneven capitalist systems, they were understood as bringing COVID-19 into communities.

Uganda: truck drivers and risk

The Ugandan government’s response to COVID-19 was one of the most stringent on the continent (Haider et al. Citation2020; Parker et al. Citation2020) Prior to the first case being reported there on 22 March 2020, the central government had undertaken multiple cautionary measures: it enforced mandatory screening and testing at land borders, restricted international travel, developed quarantine facilities for returning Ugandans, prohibited public gatherings,]and closed educational institutions (Parkes et al. Citation2020) Reproducing global manifestations of Sinophobia, many Ugandans avoided foreign travelers and Asian contract workers, as well as those who had traveled abroad. In Kampala, one respondent noted the heckling of white expatriates and Asian workers, since they were inscribed with the threat of infection. Early fears were most acute in the capital, Kampala, connected by air to China and Europe. But in peripheral towns too, Asian people were stigmatised. In Arua, a Chinese road-worker was evicted from a hotel in efforts to control viral spread in the region. Ugandans improvised forms of contact tracing, whereby those known to have traveled internationally were avoided.

After Uganda reported its first case, all non-Ugandan citizens were banned from entering the country: Entebbe International Airport was closed, public transport was suspended and only the sale of essential commodities was permitted. These measures were followed by wider restrictions on movement: a national nighttime curfew, stay-at-home directives, closure of non-food businesses, and restrictions on gatherings exceeding five persons. These restrictions had profound effects on everyday life. Lockdowns were policed by the military, with violations subject to sporadic, severe punishment. These measures continued until early June 2020, and for much longer in some “high risk” border districts, including our case study sites. Commentators feared neglecting economic security by prioritising health could bring widespread food shortages to the country’s poor (UNDP Citation2020a)

Noting the timing of the measures with the national election (held on 14 January 2021) observers drew connections between the stringency of measures and attempts by the ruling party to subdue political dissent (HRW Citation2020; Parker et al. Citation2020) Restrictions upon the entry of international reporters provided a stage for the longstanding National Resistance Movement (NRM) government to extend its tenure, away from international scrutiny. Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni boosted his own popularity as national protector in regular televised addresses, where his increasingly authoritarian tactics were transformed “into a caring grandpa who tenderly addresses his audience as bazzukulu, the Luganda word for grandchildren” (Anguyo Citation2020) Politics played out in other ways: the allocation of food relief designated as the sole purview of the ruling party and the distribution of face masks adorned with party emblems. Indeed, the politicisation of Uganda’s pandemic was not lost on the general population, many of whom initially equated COVID-19 to an artful “political manipulation.”

In our research sites – Kampala, the national capital, and the towns of Hoima, Pakwach and Arua – which lie on Uganda’s western border with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) – residents deployed localised nuances to comprehend COVID-19, prior to the first official documentation of cases. Initially, many residents of Pakwach, which borders Lake Albert and is separated from the rest of Uganda by the River Nile, enculturated ideas of immunity to the specifics of local geography, explaining, for instance, that “this place along the lake/river is too hot, Corona cannot survive” (Ukumu Citation2020a) Such perceptions replicated colonial tropes of racial immunity, in which Africans are designated as immune to particular kinds of diseases (Espinosa Citation2015) Yet rather than simply reproduce racialised narratives, residents in Pakwach localised immunity ideas to the specificities of local ecologies.

As cases were registered in Uganda, new logics were required to explain why and how COVID-19 spread. For local populations, this demanded a reassessment of who was crossing internal borders, which came to be seen as the “first line of defense” against a virus from outside (Sebba Citation2020) As with other Great Lakes countries, substantial volumes of regional freight are transported along Uganda’s roads. Our research sites, which punctuate the spinal road from Uganda’s border – where goods are transported from Kenya and Tanzania into DRC and South Sudan – have become stop-over points for truck drivers. Residents in these border towns are often engaged in small-scale trade in foodstuffs or the provision of lodging for drivers. COVID-19 would bring new resonance to these connections.

Truck drivers provided a ready target to explain the spread of viral risk. Those passing through Uganda (often migrants from Kenya, Tanzania, Somalia or Ethiopia) exhibit an obvious alterity to local populations. In towns along Uganda’s western border, the “foreignness” of truck drivers and traders is made evident through personal encounters taking place in Kiswahili rather than local dialects, in addition to the ways in which workers frequent eateries and “hotels” considered to be “immoral” places by the majority Christian population.

Yet truck drivers became entangled with viral risk not simply because of their inherent difference, but because government COVID-19 responses brought new attention to the implications of their mobility. Across the Great Lakes region, from an early stage, regional and national attempts to fight COVID-19 was waged by stopping – or heavily monitoring – truck drivers entering countries at international land borders. Indeed, several heads of East African Community (EAC) bloc countries agreed to the double testing of truck drivers, and only after receiving a negative test were drivers allowed to pass. Zambia closed its borders after Tanzanian drivers, sex workers and immigration officers tested positive in May 2020. Yet in Uganda, whilst national “stay-at-home orders” fixed local populations in space, freight was permitted to move along Uganda’s roads to international border points.

The fear of truck drivers as viral agents has an important history in the Great Lakes region (Setel Citation1999) Truck drivers were directly implicated in the spread of HIV/AIDS in the 1990s, as were the sex workers, or “barmaids,” who were associated with them at these stop-over points. Such ideas were deeply related to who was tested. In Uganda, findings from an early study in Rakai (Carswell et al. Citation1989) which found a sample of truck drivers to be 33% positive and barmaids to be 67% positive, were extrapolated (in lieu of alternative evidence) to the rest of the country. Yet, as Allen (Citation2006:12) notes, data on rates among drivers and sex workers in wider Uganda remained “sparse”. Whilst scholars codified these assumptions into research across Great Lakes countries, exploring knowledge, attitudes and practices among risk groups (Kohli et al. Citation2017; Morris and Ferguson Citation2006) other populations were simply ignored (Sileo et al. Citation2019) On the one hand the individuation of risk occluded considerations for capitalist inequalities which produced vulnerabilities associated with the spread of HIV. In equal measure, the construction of this risk group served to assuage fears among the community, particularly during the early years of the epidemic (Akwara et al. Citation2003; Smith Citation2003)

As in the history of HIV/AIDS, approaches to COVID-19 testing produced the social realities they described. In Pakwach, where, from April 2020 onward, testing was implemented for migrants crossing the border, it was truck drivers who were tested, and so made up the first confirmed cases. This reflected wider patterns across Uganda. Based on an analysis of official press releases from the Ugandan government, Bajunirwe et al. (Citation2020) noted that by June 2020, of 442 positive tests administered, 317, or 71.8%, were truck drivers. Whilst statistics reflect testing strategies, these approaches quickly became expressed in local notions of viral risk. At that point, few members of the resident population had received a COVID-19 test.

Ugandan leaders too played a significant role in stoking public fears of truck drivers as intermediate viral threats. For instance, in April 2020, in Arua District, leaders refused to treat a Kenyan truck driver who had tested positive. Following the case, Dr Ruth Aceng, the Ugandan Minister for Health, warned Ugandans that “you need to prepare your minds that any cargo truck coming to your border points of entry, is a potential source of infection” (Ukumu Citation2020b) In response to these fears, a group of Pakwach residents demanded of the drivers, “Let them just pass, let them not stop here”. The Local Council Chairperson petitioned the COVID-19 Task Force to prohibit the stopping of truck drivers altogether. When these campaigns were ignored, borderland residents improvised their own solutions, which often involved avoidance or stigmatisation. Many locals sacrificed trade for safety, and no longer sold goods or offered shelter to drivers. Some landlords threatened to evict those who continued to have direct contact with truck drivers. Thus, local fears of truck drivers as COVID-19 carriers were accentuated by a wider politics of managing cases – in turn aggravating preexisting ideas about blame for the spread of disease.

Over time, fears of truck drivers were transposed onto selected groups of residents – such as the local sex workers who serviced them – who interacted with them. In Pakwach, residents reportedly heckled sex workers with “don’t bring us the Corona!”, forcing several women to flee to the neighboring District.

Whilst these fears illustrate the longstanding marginal position of sex workers in Ugandan society, as well as the accusation of those with “immoral” habits for the earlier spread of HIV/AIDS, fears also responded to changing local evidence. On 24 April 2020, four Tanzanian truck drivers destined for DRC tested positive for COVID-19 at the Mutukulua border (Uganda/Tanzania) Test results were not released until the drivers had traveled for a subsequent day into the district, when contact tracing revealed they had interacted with nine sex workers after testing. The truck drivers and sex workers were subsequently quarantined together at a local school. As the news of cases spread, the infectious nature of other social groups of people were debated.

Sex workers and Ugandan traders occupied a liminal status: both were connected to risky outsiders but also remained as riskless insiders, and critically, this status transposed onto claims of environmental immunity. Thus, when it was later discovered that the sex workers who had quarantined with the truck-drivers tested negative, some concluded: “You see! The high temperatures of Pakwach burnt the corona on those that slept with the drivers” (Ukumu Citation2020b) Official evidence was negotiated within local moral words – being a powerful tool with which to both insist upon, as well as debunk viral risk.

It is important to highlight that while Ugandans along the western border discussed risk in locally specific terms, such comments were inherently political. In commenting on those who moved around for work, homebound residents lamented a President who prioritised national wealth and freight movement, whilst ordinary Ugandans faced destitution under restriction, saying: “We are here struggling, yet their [Museveni’s] business is moving on,” and “Our businesses can’t be done because movement is hard, yet theirs can’t be stopped.” Yet, political woes were translated into risk through the labeling of particular groups through testing strategies and contact tracing by District Health Teams. Here, risk was apportioned to evolving social categories, not just to outsiders, but later to insiders who associated with them.

Malawi: migrant traders

As in Uganda, many Malawians understood COVID-19 to come from people who resided outside national boundaries, in China or Europe. In Blantyre, many residents became increasingly panicked after images of Europeans dying in hospitals spread through social media. As was summarised by one researcher: “it was seen to belong to non-African races – anyone seen to be of a different color was seen to be a potential carrier of the virus.” Since COVID-19 appeared to be undermining health systems in European countries – where Malawians believed provision was adequate – there was heightened concern about the fate of Malawians should COVID-19 enter the country. Yet, at this stage, many emphasised the impermeability of African bodies to risk: “this virus cannot come here, it cannot enter African bodies.” Such comments reflect a sentiment that more clearly aligns with colonial tropes of racial difference, shifting focus onto the immunity of the body more specifically, as opposed to the environmental conditions of heat.

Accordingly, in March 2020, before cases were registered, fears of contact were primarily related to Asian people, particularly development workers within the country. While Malawians looked to the government to act, an increasingly unpopular regime was deemed at failing to regulate its borders. A high-profile failure occurred on 23 March 2020, when the government ordered the deportation of 14 incoming Chinese nationals from Chileka International Airport. Since only 10 were in possession of return tickets, the remaining four were ordered to quarantine. When the Chinese nationals’ lawyers obtained a court injunction against the order and the individuals were freed, the impotency of the government was highlighted. The associations between COVID-19 and outsiders were further confirmed when the first three cases of COVID-19 documented in Malawi, registered on 2 April 2020, were found in the household of a resident who had traveled from India, and who had subsequently infected his relative and a domestic worker.

Fears were further heightened when neighboring South Africa and Zambia reported cases in early April. It is important to note that the Malawian economy is heavily dependent on labor migration to these countries. Some work is facilitated through government agreements, while other traders move commodities over the border informally, along unmonitored roads. Thus, in ordinary times, the Malawian economy feeds into differential movement: those who move for trade, and those who remain occupied by agriculture, trade or other employment at home. In a crude sense, the economy is bifurcated between migrants and those who stay. During COVID-19, those who stayed were deeply worried about their livelihoods, should strict lockdown measures be imposed. Similar to Ugandans, whilst Malawians feared the health impacts of a new virus, many also feared the economic devastation that stay-at-home orders could bring. Thus, when on 18 April 2020, then-President Mutharika announced a 21-day lockdown that mandated the closure of schools and businesses, the move was deeply unpopular.

Fears were expressed locally and in political protest: manifesting simultaneously in avoidance of migrants and vociferous critiques of government policy. For example, in the city of Mzuzu in Malawi’s Northern region, residents opposed the establishment of an isolation unit, burning mattresses and beds during an open protest in May 2020. According to the Nyasa Times, one protestor explained: “we cannot allow COVID-19 patients near us.” Civil society groups instigated protests in major cities and petitioned the supreme court of Malawi to overthrow the lockdown. Coinciding with party campaigns in the run-up to the scheduled national election in July 2020, COVID-19 mitigation measures were drawn into party politicking. The then-opposition government, the United Transformation Movement (UTM) overtly challenged the government restrictions on internal movements in order to garner public support. At a political rally held in the capital, Lilongwe, in May, Dr Saulos Chilima, the then-vice-president and opposition leader instructed the public to ignore social distancing rules and “embrace” members of the party (Masina Citation2020)

As opposition to the lockdown grew, the government continued to pursue public health policies restricting movement, which was perceived to be bringing COVID-19 into Malawi. In Chikwawa, these policies were particularly unpopular with informal traders, who crossed borders into Mozambique and South Africa to purchase cheap goods for import. Whilst the livelihoods of traders, who feared to cross, were deeply affected, the government was seen as facilitating the return of registered migrants, and thereby bringing COVID-19 into the country. At the same time, there was no routine testing in place for those who returned. Amidst the lockdown, during the early months of the pandemic, efforts were made to repatriate migrant workers stranded in South Africa. On 12 May 2020, the Malawian government sent buses to a COVID-19 “red zone” in South Africa to bring home stranded citizens. This move was widely opposed, particularly when returnee cases, which numbered 134 at the time, almost doubled the total number of confirmed cases in the country. At the intersection of government policies, in Blantyre and Chikwawa, Covid-19 was understood as tied to migrant workers. Commentary on government policies came to focus on whether these policies prevented the movement of outsider/border migrants.

Cross-border migrants also bear historical associations with purported responsibility for sickness. As with truck drivers, labor migrants offer a similarly uneasy position in the social fabric of rural African societies. Whilst family members are often reliant upon remittances and support from (usually male) traders, their mobility has long intersected with fears of bringing harm to relatives left behind. Such fears have long legacies in Malawi. During colonial rule, patterns of migration engendered new patterns of witchcraft accusation in rural-returnee communities (Englund Citation1996) Returnees were believed to have been corrupted by modernity, and were sometimes accused of witchcraft amidst health crises after return. Such fears as to the hidden potential of outsiders have prevailed in the postcolonial period, and have become linked to public health concerns. Chirwa (Citation1998) documents how HIV/AIDS was used as a “smokescreen” to permit the repatriation of Malawian miners working as migrant laborers in South Africa between 1988–92. Yet, such measures served to stigmatise Malawian workers, presenting them as carriers of the virus within the public imagination. For migrants, the exclusionary dynamics of capitalism within state peripheries necessitates migration to survive, in turn, producing particular vulnerabilities – and these are further exacerbated as they are placed outside the socio-moral fabric of communities. As in Uganda, the approach of the Malawian government re-activated preexisting geographies of blame.

This unpopularity of government measures helped to account for the election of a new leader, President Lazarus Chakwera, on 28 June 2020. Departing from his predecessor’s example, in a public address shortly after his election, Chakwera explained that “People have to accept COVID-19, that it is a new reality they have to live with, but be cautious at the same time” (Kaponda Citation2020) In mid-July, the Presidential Task-Force on COVID-19 introduced new measures including the mandatory wearing of face masks in public (including fines) but did not insist upon nationwide lockdowns. Mimicking the approach of the late Tanzanian President, John Magafuli, Chakwera invoked divine intervention in the face of the virus, hosting a National Day of Thanksgiving on 19 July 2020, preceded by three days of fasting and prayer. In October, he visited Tanzania and was photographed without a face mask. Whilst the virtual denialism of COVID-19 by the new President troubled many, the relief from lockdowns proved popular as reported caseloads remained low. By the end of October, just four cases had been reported from Chikwawa District, though rates were higher in Blantyre, the business center of the country, which registered a cumulative case load exceeding 1,500 cases, and a death toll of 75 by this time.

Attitudes changed from mid-December 2020 on, with the arrival of the Beta variant. Around the same time that international media reported the spread of a “new strain” across the border, cases began to rise in Malawi. By January 2021, people were dying on a daily basis in both urban and rural areas, with an interlocutor in Blantyre reporting, “There was fear – people can see death, so they fear.” Given these perceptions of mortality, many Chikwawa and Blantyre residents believed official statistics were much lower than actual rates of transmission. Fear was bolstered, moreover, by the death and public coverage of several high-profile government officials. In contrast to the first wave, this same interlocutor continued: “They are now showing they are serious, people believe there is COVID-19 and it is killing people, there is no doubt.” On 12 January 2021, the new administration declared a National State of Emergency, which included a partial lockdown and saw the police enforcing mask-wearing and sanitation measures.

The new government continued to facilitate the return of Malawian migrants via buses, and to allow citizens to cross the border using their own means. Reportedly, this led some to discredit the new regime: “Politicians are the same, this is the way of politicians, we cannot take them seriously.” Unlike the administration of President Mutharika, however, Chakwera’s government instigated measures to test returnees at the border. According to an interlocutor in Chikwawa, many locals trusted the screening process: if community members had returned from South Africa and had received a negative test result at the border, their return was not stigmatised by relatives or neighbors.

With cases remaining high, however, some skepticism remained. In Chikwawa, rumors circulated regarding disparities on the bus manifest lists between the numbers of returning migrants and the actual number of passengers. It was thought that unregistered passengers may have evaded testing, and were responsible for the cases imported into communities. Knowing of the expense of testing in South Africa, other rumors circulated around fake COVID-19 certificates being purchased in South Africa to allow migrants to return home: “How many had come with fake certificates from abroad?” Given these fears, many reported a reluctance to engage with returnees, and the urban elite opposed the government’s policies that facilitated return. In Blantyre, a theory circulated that the government had continued to allow returnees to keep numbers of positive cases high, thereby retaining international donations for COVID-19: “The guys on the task force, they knew if Malawi was declared free, they will lose their jobs.”

Riskscapes rapidly evolved as cases remained high in early 2021. With partial trust in border testing maintained, health workers became associated with spreading COVID-19. Whilst traders and health workers may present as distant social categories, Luedke and West (Citation2006) note that health workers too transgress borders, serving as an embodiment of the ambiguity between different therapeutic systems. Indeed, if migrant traders had been thought to bring back the virus unwittingly as they moved physically across the border, more insidious claims were levied at health-workers. In Blantyre, rumors spread that medical personnel (who received allowances for treating COVID-19 patients) were intentionally injecting people with COVID-19 to maintain their salaries. These theories were only confirmed for their adherents when health workers were designated as the first category to receive vaccines (whilst administering jabs to the general population) in March 2020. Reportedly, health workers were chased away from COVID-19 funerals on charges that “you are killing our relatives.” Geographies of blame adapted to new landscapes of grief and panic, with new “others” being reified through shifts in the landscape of national data and government policy.

Discussion: producing mobile ‘others’

Ultimately, we have demonstrated that viral threats do not reach a population unmediated. Embedded in the borderscapes of the African Great Lakes region, our research coalesced around movement. Manderson and Levine (Citation2020:367) note that, by contrast to coverage of Ebola, COVID-19 appears to be beyond the specifics of culture. Whilst mobility, intensified at borders, is a feature of any viral outbreak, it is important that we unpack the grounded dynamics through which particular groups of mobile people become perceived as central nodes of risk. A grasp of this risk-perception allows us to make better sense of blame narratives.

We position risk perceptions as social processes, structured by viral histories, economic relations, health metrics, government (in) ction, and testing practices. During a crisis such as COVID-19, everyday attempts to make sense of uncertainty involve engaging, reinterpreting and localising “threats” made present internationally and nationally through Presidential declarations, World Health Organisation and government statistics and public health messages of local health teams. Riskscapes render themselves to encapsulate populations’ assessment of “scientific” evidence, whilst simultaneously and sensitively attending to local histories of viral blame.

Using this approach, we avoid collapsing variegated riskscapes into mere “conspiracy theories” or forms of “misinformation,” a designation which has been readily applied to encompass threads of the COVID-19 “infodemic” – understood as a parallel realm to formal scientific practice (Lancet Infectious Diseases Citation2020) However, it is false to suggest a dichotomy between practices deemed scientific and social. Indeed, such scripts have long been merged. Anthropologists have shown how biomedicine has become subsumed in forms of knowledge and rumor, which, whilst seemingly “irrational,” are given life through the opacities and illegitimacy of clinical practices in colonial and post-colonial contexts (for example, White Citation2000) Simultaneously, the social and political biases entangled in the production of so-called objective statistics, have been subject to ethnographic exploration (Biruk Citation2018)

In Uganda and Malawi, the immediate juxtaposition of COVID-19 with national elections, layered with everyday mistrust in leaders, led many to question how health measures were connected to struggles for power, and open to manipulation by zealous leaders seeking to avoid scrutiny or steal elections (Mwine-Kyarimpa 2021; Parker et al. Citation2020) Overt political calculations, manifesting as COVID-19 denialism or a rejection of efforts to control the virus, have been well documented in citizen’s responses to COVID-19 across Africa (Sabiti Citation2021; Vaughn et al. Citation2020) Yet, this mistrust plays out in other ways with respect to peoples’ assessment of risk. Peoples’ proactive search to obtain and apply information in contexts of flux and uncertainty, remains entangled with locally-specific drivers of risk (Müller-Mahn et al. Citation2020)

Our empirical analysis has highlighted the continuities in regionally specific forms of disease surveillance. This evidence contributes to a portrait hidden by the processes used to track and describe COVID-19 based on the collection of apparently objective epidemiological data. Whilst scholars have noted the shortcomings of “crisis” data collection in most national contexts, such limitations may be more acute in countries without robust routine disease surveillance systems in place, such as those in the African Great Lakes region. The “crisis” testing regimes set up in these contexts, accompanied by limited diagnostic resources, reproduce existing notions of “others” by targeting specific populations for testing and reporting on disease transmission within these groups – in turn, presenting the untested general population as (initially) free from infection.

As elsewhere, across the many communities of the African Great Lakes region, data collection and health metrics (as well as their reporting through the media) are not objective, but are shaped by, and shape ideas of, who engenders the most risk (Biruk Citation2018) Initial limitations in diagnostic resources meant that widespread testing was not available or accessible to the entire population. The designations of testing priority groups were political decisions based largely on existing disease mitigation strategies of predefined “at-risk” populations, and a government’s desire to secure their borders to “control the virus.” Testing strategies became synonymous with border control, and thus (particularly when mortality rates remained low) the burden of the virus among general populations remained largely unknown, extrapolated as it was from very specific sub-groups.

In Uganda, testing efforts were focused at international and internal borders – rendering a focus on truck drivers. This was compounded as local sex workers who serviced them were also tested and quarantined. In Malawi, fears arose regarding unregistered returnees or returnees using falsified negative test certificates, highlighting how the very notion of testing was contested and continued to shape perceptions of viral risk. Whilst borders, as a real and imagined space, can reify boundaries between those inside and those outside, providing a medium to visibilise and produce the Other (Laine Citation2016) in contexts of limited information and panic, testing processes intensify the production of difference across borders.

Though partial, testing statistics during COVID-19 are often treated as absolute, and objective facts (Caduff Citation2021) Our evidence shows how the selective nature of national policy decisions regarding testing eligibility (according to mobility) was erased when testing figures became incorporated within local formulations of risk. These were ideas which shifted with the localisation of testing – for example, after suspected cases were registered and contacts were chased. Crucially too, statistics became drawn into a social-moral world where risk was related to prior histories of blame activated by previous and existing health crises (notably HIV/AIDS) where the infectivity of particular sub-groups has been reified through testing. In this way, COVID-19 testing regimes aggravated preexisting processes of othering.

In many ways, these findings dialogue with an existing and more substantive body of work exploring social processes of risk and blame in Europe and the US. As has become clear throughout the pandemic, viral blame has been as unequal as viral transmission and forms of globalised Othering have been prominent throughout the pandemic (Ross Citation2020; Wald Citation2020) As Dionne argues in an analysis of “Pandemic Othering,” migrants and marginal groups have long been targets for blame and scapegoating during health crises, where ‘in-groups create the “other” as targets of blame and to build boundaries between groups, stigmatizing migrants and other marginal groups as “disease breeders”” (Dionne and Turkmen Citation2020, pp. 215–216) COVID-19 has seen accusations and attacks toward Asian people in the West, drawing on racist tropes and exoticisation tactics (Hasunuma Citation2020; Renny and Barreto Citation2021; Roberto et al. Citation2020; Sparke and Anguelov Citation2020) While not necessarily operating through the same logics, our data reveals localised geographies of blame. Such dynamics are critical in that they reveal potentially damaging incidences of exclusion and marginalisation. This can have significant bearings on health-seeking practices, as well as mental wellbeing and access to livelihoods.

In our study sites, fear of viral risk has been linked to moments of profound exclusion for particular social groups. At Uganda and Malawi’s borders, geographies of blame have been linked historically to draconian surveillance of outsiders, as well as improvised forms of quarantine. Such approaches to disease containment have compromised the rights of those deemed at “risk,” to “preserve the health” of the majority. Whilst containment strategies differed radically between communities, stigma was often weaponised to ostracise. For example, in North-Western Uganda during the 1990s HIV/AIDS crisis, elders publicly prohibited sexual intercourse outside of marriage, but also directly intervened to prevent marriages with women believed to be HIV-positive, and encouraged people to avoid contact with households associated with the virus (Allen and Storm Citation2012) This was a form of social quarantine derived when populations had been exposed to testing, but not treatment through anti-retroviral drugs. During the Congolese Ebola epidemic (2018–19) too, families, elders and local councillors were involved in scrutinising movement of traders, to ensure Ugandans did not cross over the border to Congo, potentially contracting the virus. Covid-19, known by many as the disease with “no cure”, ushered in a moment when survival was understood to rely on social vigilance.

While further work would be required to understand the links between health outcomes and viral risk perceptions, repeated and reactivated stigmatisation is certainly an important area of future enquiry. Indeed, the implications are significant, given that fears of being targeted, quarantined and marginalised during epidemic crises deeply influences health-seeking behavior. Such concerns are particularly acute given emerging evidence which suggests that social groups who anticipate stigma may be less likely to access COVID-19 tests, and latterly, vaccines (Earnshaw et al. Citation2021; Ferree et al. Citation2021)

Concluding remarks

To conclude, the data reveal how the perception of viral risk and geographies of accusation draw not just on continental demarcations, but also upon place-specific inequalities, viral pasts, histories of blame and public health policies. Through an analysis of grounded riskscapes in seven locations across Uganda and Malawi, our data show that as cases in local communities of Uganda and Malawi were registered, COVID-19 riskscapes were re-orientated in relation to internal and external borders. In this respect, bordered spaces acted as a prism through which mobility was made visible, testing was concentrated and risk perception manifest. It is within this landscape of risk that mobile others became central nodes of risk perception – thus producing and reenacting geographies of blame. In this respect, we argue that examining grounded riskscapes reveals otherwise neglected forms of discriminatory discourse and practice that remain out of view in the broader landscapes of pandemic geography and dashboard statistics.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the editors and reviewers for their engagement and assistance with developing this article. We are sincerely grateful to all research participants in Uganda and Malawi, and to all LEAD collaborators: Innocent Anguyo, Noah Ukumu, Jimmy Osuta, Chikondi Kaponda, Steve Kaunga, Alex Ayoyi, Halfan Hashim Magani, Duncan Njue, Shauji Saidi Mpota and Thomson Isingoma. Thanks go to Laurence Radford for his editorial work in relation to the Shifting Spaces blog. We also thank Professor Tim Allen and Professor Melissa Parker for their guidance and input through the LEAD Project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s)

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elizabeth Storer

Dr Elizabeth Storer is a post-doctoral researcher at the Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, U.K.

Kate Dawson

Dr Kate Dawson is a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Geography and Environment and Researcher with the Localised Evidence and Decision-making (LEAD) Project in the Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa at the London School of Economics and Political Science

Cristin A. Fergus

Cristin A. Fergus is a doctoral researcher in the Department of International Development and Lead Investigator of the Localised Evidence and Decision-making (LEAD) Project in the Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa at the London School of Economics and Political Science

References

- Adams, V 2016 Metrics: What Counts in Global Health. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Akwara, P, N Madise, and A Hinde 2003 Perception of risk of HIV/AIDS and sexual behaviour in Kenya. Journal of Biosocial Science 35(3):385–411. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932003003857.

- Ali, H, B Dumbuya, M Hynie, P Idahosa, R Keil, and P Perkins 2016 The social and political dimensions of the Ebola response: Global inequality, climate change, and infectious disease. Climate Change and Health. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24660-4_10.

- Allen, T 2006 AIDS and evidence: Interrogating [correcting] some Ugandan myths. Journal of Biosocial Science 38(1):7–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932005001008.

- Allen, T, and L Storm 2012 Quests for therapy in northern Uganda: Healing at Laropi revisited. Journal of Eastern African Studies 6(1):22–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2012.664702.

- Anguyo, I 2020 The politics of food relief in Uganda’s COVID-19 era. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2020/07/01/politics-food-relief-aid-uganda-covid19/.

- Bajunirwe, F, and J Izudi. S Asiimwe 2020 Long-Distance truck drivers and the increasing risk of COVID-19 spread in Uganda. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 98:191–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.085.

- Beck, U 1998 World at Risk. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Benton, A, and K.Y Dionne 2015 International Political Economy and the 2014 West African Ebola Outbreak. African Studies Association 58(1):223–36.

- Biruk, C 2018 Cooking Data: Culture and Politics in an African Research World. Duke: University Press.

- Bonaccorsi, G, G Pierri, M Cinelli, A Flori, A Galeazzi, F Porcelli, A Schmidt, C Valenssie, A Scala, and F Pammolli 2020 Economic and social consequences of human mobility restrictions under COVID-19. Pnas 117(27):15530–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2007658117.

- Borkowski, P, A Szmelter-Jarosz, and M Jażdżewska-Gutta 2021 Lockdowned: Everyday mobility changes in response to COVID-19. Journal of Transport Geography 90:102906. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102906.

- Braun, Y A. 2020 Environmental change, risk and vulnerability: Poverty, food security and HIV/AIDS amid infrastructural development and climate change in Southern Africa. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 13(2):267–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsaa008.

- Caduff, C 2021 what went wrong: Corona and the world after the full stop. Medical Anthropology Quarterly:1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12599.

- Carswell, J W., G Lloyd, and J Howells 1989 Prevalence of HIV-1 in East African lorry drivers. Aids 3(11):759–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00002030-198911000-00013.

- Carteni, A, L Francesco, and M Martino 2020 How mobility habits influenced the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from the Italian case study. The Science of the Total Environment 1(741). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140489.

- Cevik, M, S D. Baral, A Crozier, and J A. Cassell 2021 Support for self-isolation is critical in covid-19 response. The BMJ 372:n224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n224.

- Chirwa, WC. 1998 Aliens and AIDS in Southern Africa: The Malawi-South Africa Debate. African Affairs 97(386):53–79.

- Chitungo, I, M Dzobo, M Hlongwa, and T Dzinamarira 2020 COVID-19: Unpacking the low number of cases in Africa. Public Health in Practice (Oxford, England) 1:100038. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhip.2020.100038.

- Dionne, K, and F Turkmen 2020 The Politics of Pandemic Othering: Putting COVID-19 in Global and Historical Context. International Organization 74(s1):213–230.

- Dobusch, L, and K Kreissl 2020 Privilege and burden of im-/mobility governance: On the reinforcement of inequalities during a pandemic lockdown. Feminist Frontiers 27(5):709–16.

- Earnshaw, VA., NM. Brousseau, E Carly Hill, SC. Kalichman, and LA. Eaton 2021 Anticipated Stigma, Stereotypes, and COVID-19 Testing. Stigma and Health 5(4):390–93.

- Englund, H 1996 Witchcraft, Modernity and the Person: The morality of accumulation in Central Malawi. Critique of Anthropology 16(3):257–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X9601600303.

- Espinosa, M 2015 The Question of Racial Immunity to Yellow Fever in History and Historiography. Social Science History 38(3–4):437–53.

- Everts, J 2020 The dashboard pandemic. Dialogues in Human Geography 10(2):260–264.

- Farmer, P 2006 AIDS and Accusation: Haiti and the Geography of Blame. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Ferree, KE., AS. Harris, B Dulani, K Kao, E Lust, and E Metheney 2021 Stigma, trust, and procedural integrity: Covid-19 testing in Malawi. World Development 141:1–6.

- Gee, S, and M Skovdal 2017 Navigating ‘riskscapes’: The experiences of international health care workers responding to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Health & Place 45:173–80. Epub 2017 Apr 6. PMID: 28391128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.03.016.

- Gilbert, M, G Pullano, F Pinotti, E Valdano, C Poletto, and P Boëlle 2020 ‘Preparedness and vulnerability of African countries against importations of COVID-19:A modelling study’. The Lancet 395(10227):871–77.

- Glaeser, EL., C Gorback, and SJ. Redding 2020 JUE insight: How much does COVID-19 increase with mobility? Evidence from New York and four other US cities. Journal of Urban Economics 127:103292.

- Haider, N, AY Osman, and A Gadzekpo, et al. 2020 Lockdown measures in response to COVID-19 in nine sub-Saharan African countries. BMJ Global Health 5:e003319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003319.

- Hasunuma, L 2020 We are All Chinese Now: COVID-19 and Anti-Asian Racism in the United States. The Asia-Pacific Journal 18(15):1–8.

- Hensen, B, C R S Mackworth-Young, M Simwinga, N Abdelmagid, J Banda, A Mavodza, A.M Doyle, C Bonell, and H.A Weiss 2021 Remote data collection for public health research in a COVID-19 era: Ethical implications, challenges and opportunities. Health Policy and Planning 36(3):360–68.

- Houreld, K, and D Lewis 2020 In Africa, lack of coronavirus data raises fears of ‘silent epidemic’, Reuters, July 8th 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-africa-data-insigh-idUSKBN24910L.

- HRW 2020 Uganda: Authorities Weaponize Covid-19 for Repression: Investigate Killing, End Arbitrary Detention, Allow Peaceful Gatherings. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/11/20/uganda-authorities-weaponize-covid-19-repression.

- Kaponda, C 2020 No COVID-19 lockdown still threatens livelihoods and trade in Malawi. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2020/09/25/no-covid19-lockdown-threatens-livelihoods-trade-trust-malawi/, accessed April 23, 2021.

- Kohli, A, D Kerrigan, H Brahmbhatt, S Likindikoki, J Beckham, A Mwampashi, J Mbwambo, and CE. Kennedy 2017 Social and structural factors related to HIV risk among truck drivers passing through the Iringa region of Tanzania. AIDS Care 29(8):957–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2017.1280127.

- Laine, J 2016 The Multiscalar Production of Borders. Geopolitics 21(3):465–482.

- Lancet Infectious Diseases 2020 The COVID-19 infodemic. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 20(8):875. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30565-X.

- Luedke, TJ., and H West 2006 Introduction: healing divides: therapeutic border work in Southeast. In Borders and Healers: Brokering Therapeutic Resources in Southeast Africa, T. J. Luedke and H. G. West, ed. Pp. 1–20. Indiana: University Press.

- Lunstrum, E, N Ahuja, B Braun, R Collard, PJ. Lopez, and RW. Wong 2021 More‐than‐human and deeply human perspectives on COVID‐19. Antipode 53(5): 1503–1525.

- Manderson, L, and S Levine 2020 COVID-19, risk, fear, and fall-out. Medical Anthropology 39(5):367–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2020.1746301.

- Martin, S, and J Bergmann 2021 Im)mobility in the Age of COVID-19'. The International Migration Review. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918320984104.

- Masina, L 2020 Malawi Top Court upholds Presidential election re-run. Voice of America. May 9. https://www.voanews.com/africa/malawi-top-court-upholds-presidential-election-re-run.

- Mbembe, A 2001 On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Mock, B 2020 No Black People Aren’t Immune to Covid-19. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-14/no-black-people-aren-t-immune-to-covid-19.

- Montacute, R 2020 Social Mobility and COVID-19: Implications of the COVID-19 Crisis for Educational Inequality. UK: Sutton Trust.

- Morris, C N, and A G Ferguson 2006 Estimation of the sexual transmission of HIV in Kenya and Uganda on the trans-Africa highway: The continuing role for prevention in high risk groups. Sexually Transmitted Infections 82(5):368–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2006.020933.

- Mudimbe, VY. 1988 The Invention of Africa. Bloomington: India University Press.

- Müller-Mahn, D 2015 The Spatial Dimension of Risk: How Geography Shapes the Emergence of Riskscapes. Oxon: Routledge.

- Müller-Mahn, D, J Everts, and C Stephan 2018 Riskscapes revisited – exploring the relationship between risk, space and practice. Erdkunde 72(2):197–213.

- Müller-Mahn, D, and E Kioko 2021 Rethinking African futures after COVID-19. Africa Spectrum 56(2):216–27.

- Müller-Mahn, D, M Moure, and M Gebreyes 2020 Climate change, politics of anticipation, and the emergence of environmental riskscapes in Africa. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy, and Society 13(2): 343–362.

- Parker, M, TM. Hanson, V Vandi, L Sao Babawo, and T Allen 2019 Ebola and public authority: Saving loved ones in Sierra Leone. Medical Anthropology 38(5):440–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2019.1609472.

- Parker, M, H MacGregor, and G Akello 2020 COVID-19, public authority and enforcement. Medical Anthropology 39(8):666–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2020.1822833.

- Parkes, J, S Datzberger, C Howell, J Kasidi, T Kiwanuka, and L Knight. R Nagawa D Naker. K Devries 2020 Young People, Inequality and Violence during the COVID -19 lockdown in Uganda. CoVAC Working Paper. https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/2p6hx/, accessed February 13, 2021.

- Radil SM, Castan Pinos J and Ptak T. 2021. Borders resurgent: towards a post-Covid-19 global border regime? Space and Polity 25(1):132–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2020.1773254

- Renny, T, and M Barreto 2020 Xenophobia in the time of the pandemic: Othering, anti-Asian attitudes, and COVID-19' politics. Groups, and Identities. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2020.1769693.

- Renzaho, AM. 2021 Challenges associated with the response to the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic in Africa—An African Diaspora perspective. Risk Analysis 41(5):831–36.

- Richardson, J, B Godfery, and S Walklate 2021 Rapid, remote and responsible research during COVID-19'. Methodological Innovations 14(1):1–9.

- Roberto, K, A Johnson, and B Rauhaus 2020 Stigmatization and prejudice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Administrative Theory & Praxis 42(3):364–378.

- Rosenthal, P J., J G. Breman, A A. Djimde, C C. John, M R. Kamya, R Leke, M R. Moeti, J Nkengasong, and D G. Bausch 2020 COVID-19: Shining the light on Africa. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 102(6):1145–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0380.

- Ross, J 2020. Coronavirus outbreak revives dangerous race myths and pseudoscience. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/coronavirus-outbreak-revives-dangerous-race-myths-pseudoscience-n1162326.

- Saberi, P 2020 Research in the time of Coronavirus: Continuing ongoing studies in the Midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. AIDS and Behaviour 24:2232–2235.

- Sabiti, B 2021. The data politics of pandemics: The cost of Covid-19 denialism CIPESA https://cipesa.org/2021/04/the-data-politics-of-pandemics-the-cost-of-covid-19-denialism/, accessed September 29, 2021.

- Sebba, KR. 2020 Mobility and COVID-19: A case study of Uganda. https://blogs.soas.ac.uk/ref-hornresearch/2020/08/07/mobility-and-covid-19-a-case-study-of-uganda/, accessed March 29, 2020).

- Setel, P 1999 A Plague of Paradoxes AIDS, Culture, and Demography in Northern Tanzania. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Shokouhyar, S, S Shokoohyar, and A Sobhani 2021 Shared mobility in Post-COVID Era: New challenges and opportunities. Sustainable Cities and Society 67(1):102714. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.102714.

- Sileo, K, W Kizito, RK. Wanyenze, H Chemusto, W Musoke, B Mukasa, and SM. Kiene 2019 A qualitative study on alcohol consumption and HIV treatment adherence among men living with HIV in Ugandan fishing communities. AIDS Care 31(1):35–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2018.1524564.

- Smith, J 2003 Imagining HIV/AIDS: Morality and perceptions of personal risk in Nigeria. Medical Anthropology 22(4):343–372.

- Sparke, M, and D Anguelov 2020 Contextualising coronavirus geographically. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 45(3):498–508.

- Taylor, C, C Boulos, and D Almond 2020 Livestock plants and COVID-19 transmission. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(50):31706–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2010115117.

- Ukumu, N 2020a Dispelling COVID-19 rumours at local levels in Pakwach, Uganda. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2020/09/09/covid19-rumours-conspiracy-local-level-pakwach-uganda/, accessed April 21, 2020b.

- Ukumu, N 2020b Truck drivers raise fears over COVID-19 and testing in Uganda’s Pakwach District. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2020/06/28/truck-drivers-fears-covid19-testing-infection-uganda-pakwach/.

- UNDP 2020 Socio-Economic Impact of COVID-19 in Uganda – UNDP. https://www.undp.org/content/dam/rba/docs/COVID-19-CO-Response/Socio-Economic-Impact-COVID-19-Uganda-Brief-1-UNDP-Uganda-April-2020.pdf, accessed February 28, 2021.

- Vaughn, L, A Kiconco, N Quartey, C Smith, and I Ziz 2020 ’COLONIAL VIRUS’? Covid-19 and Racialised Risk Narratives in South Africa, Ghana and Kenya. University of Liverpool. https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/media/livacuk/humanitiesampsocialsciences/documents/COVID-19,and,Racialised,Risk,Narratives,in,South,Africa,Ghana,and,Kenya.pdf

- Wald, P 2008 Contagious: Cultures, Carriers, and the Outbreak Narrative. Durham: Duke University Press.

- White, L 2000 Speaking with Vampires: Rumor and History in Colonial Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- WHO 2021 WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/, accessed April 14, 2021.