ABSTRACT

Learning processes have an impact on both specific problems and provide wider knowledge of different work processes. For this, managerial work has been identified as crucial. Managerial work is ad hoc and full of daily disturbances, and as learning in organisations often occurs unplanned, it is of interest to study learning processes during unplanned managerial work. A theoretical framework with two learning logics, developmental and executional learning were used. These logics are interpreted as an interdependent duality and not only as two equally important entities. The purpose of this study is to understand learning processes during unplanned managerial work in practice, from an ambidextrous perspective. An in-depth qualitative approach was used, where four learning processes were identified and analysed. We identify two ambidextrous learning logics, within complex work processes, based on either the executional or developmental mode, as a complement to existing knowledge on learning in organisations.

Introduction

The nature of work has gradually changed due to new knowledge of economics (Dixon Citation2017) and globalisation (Goh Yuen Sze Citation2019). Mass production and standardised work processes have been challenged by customised production and flexible work processes (Cressey, Boud, and Docherty Citation2006). Interest in learning in organisations has increased (Dixon Citation2017), and there is a move towards creating learning organisations for innovative production at work. During this change, learning at work has also transformed from being a formal training activity to the notion of informal productive reflection. Productive reflection is situational and produces actions in real situations at work (Cressey, Boud, and Docherty Citation2006). The need for research on learning in organisations in practice has been acknowledged by several scholars (Berends, Boersma, and Weggeman Citation2003; Örtenblad Citation2018), to which this paper will respond.

Learning occurs while working (Boud and Hager Citation2012; Ellström, Ekholm, and Ellström Citation2008); thus, learning and work are interrelated and should be investigated as such. Lizier and Reich (Citation2020) investigated professionals’ work in complex organisational contexts and identified learning through fluid work. Fluid means unstructured and unplanned; fluid work means ‘the experience of work that emerged from the day-to-day tasks encountered by participating professionals’ (7). Learning is often informal and unplanned, with processes and structures that the organisation is unaware of (Eraut Citation2004). The learning process has an impact on a specific problem in a specific situation, and provides wider knowledge of an organisation’s work processes (Cressey, Boud, and Docherty Citation2006), where managerial work has been identified as crucial (Wallo, Ellström, and Kock Citation2013).

Managerial work appears as complex, ad hoc social processes (Alvesson and Spicer Citation2011) that are needed to handle both uncertainty and ambiguity (Sayles Citation1964), with various daily disturbances (Mintzberg Citation1973), including emotions and interplay in human relations (Tengblad Citation2012). In managerial work, time-pressure tends to favour non-reflective actions (Knipfer et al. Citation2013); thus, reflection needs time (Ellström Citation2002): time to observe, think, and exchange ideas with others. Moqvist (Citation2005) noticed a discrepancy between managers’ notion of developmental work (learning) and empirical findings from observations of their work in practice. She concluded that developmental work often occurred spontaneously in daily work through interaction with others, and as something that emerged from existing practice. Contrarily, managers’ perceptions included the opposite – that developmental work occurs at specifically planned situations, by individuals when they are reflecting by themselves, leading to something radically new. In this paper, ad hoc, spontaneous work (Moqvist Citation2005), and unstructured and unplanned work processes (Lizier and Reich Citation2020) describe unplanned work, which seems to be common in managerial work, even though managers seem to be unaware of it nor take it into account (Antonacopoulou Citation2006). The definition of managerial work has changed over time from focussing on planning, coordinating, organising, commanding, and controlling (Fayol Citation1916) to including an important function for balancing resources in learning processes (Birkinshaw and Gupta Citation2013). We also define it as a social process, and managers as people in an organisation who have formal positions and responsibility for resources in managerial work processes, as the link between individuals and the organisation (Antonacopoulou Citation2006). We define unplanned managerial work as unstructured, ad hoc, spontaneous managerial work.

Several researchers (Edmondson Citation2012; Senge Citation1990) have agreed that learning in organisations is largely decided by interactions among individuals at the group level, which is the most important level in research on learning in organisations (Santa Citation2015). Knipfer et al. (Citation2013) concluded that individual and collective reflection processes from bottom-up learning are key. There are two models that have had a major impact on research investigating learning in organisations using different perspectives. One, posited by Nonaka and Takeuchi (Citation1995), uses a SECI-model for innovative learning with a cognitive perspective; the second, by Engeström (Citation1999), utilises an expansive learning cycle with a contextual perspective. Both focus on the developmental side of learning. When comparing the two in an analysis of meetings, surprisingly, Engeström (Citation1999) found that innovative meetings included non-expansive phases, which was not supported by any of the models. He concluded that ‘processes of innovation knowledge creation are not pure. They contain both expansive and non-expansive phases; both steps forward and digressions’ (391). Other studies on how cognition and context are tightly bound, (Engström Citation2014; Ellström Citation2001) correspond to this and have identified two different logics of learning: executional, (Engström and Wikner Citation2017) developed from the concept of adaptive learning, (Ellström Citation2001) and developmental learning (Engström and Wikner Citation2017; Ellström Citation2001). These two logics need to be balanced (Wallo, Ellström, and Kock Citation2013). Even though both logics have been interpreted as equally important, their relationship is often treated as two entities – incompatible and mutually exclusive in learning research – similar to how stability and change can mistakenly be viewed (Farjoun Citation2010). In this study, we follow Farjoun’s (Citation2010) recommendation and interpret these two logics of learning as a duality – contradictory in nature but mutually enabling and interdependent – as a potential ambidextrous learning process (Engström and Wikner Citation2017).

This paper’s contribution is to empirically demonstrate how learning during unplanned managerial work practices occur, and discuss the need of an ambidextrous learning perspective in integrating contradictory and independent learning logics at work. The purpose is to understand learning processes during unplanned managerial work in practice, from an ambidextrous perspective. Data were collected through shadowing and interviews with managers in small- and medium-sized manufacturing companies in Sweden.

Actions and two learning logics

Managerial work concerns numerous complex and interconnected problems. It is sometimes a chaotic work situation, including many disruptions, making the workday complex and difficult to plan (Florén Citation2005). It can be described as a smorgasbord of tasks (Tengblad Citation2012, 1455). For tasks to be accomplished, some kind of action is needed, likened to the delicacies actually eaten in a smorgasbord. Succinctly, tasks need actions in order to be performed.

Nonaka and Takeuchi (Citation1995) concluded that learning takes place when the tacit knowledge of the individual starts and spans the silent and explicit knowledge used in the work. Criticism of Nonaka and Takeuchi’s model is rooted in the separation of problem construction from problem-solving, as it is unrealistic, since the ones solving the problem will creatively reconstruct problems based on their own interpretation. According to Engeström (Citation1999), problem construction often involves communicative actions as questioning, debating, and confronting at the team level. Ellström’s (Citation1992) perspective on learning in organisations is based on similar reasoning as Nonaka and Takeuchi (Citation1995) – that organisations are composed of individuals who learn by interacting with each other according to the task at hand. Thus, similar to Engeström (Citation1999), Ellström (Citation1992) adds important context and mentions that the content, that is, what is learnt, is crucial. As a consequence of the learning process, behavioural changes can be identified at different levels within the organisation (Ellström Citation1992). Nonaka and Takeuchi (Citation1995) model focusses on implicit and explicit knowledge; Ellström (Citation2006) focusses on implicit and explicit work processes and on actions.

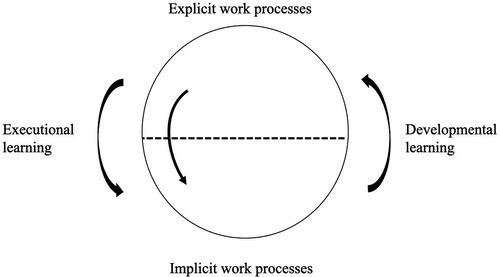

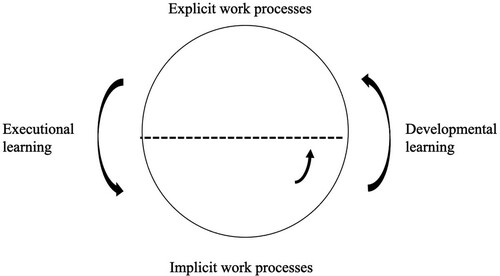

There are different levels of actions in organisational work processes (Ellström Citation2006), which sets the basis for a theoretical model in understanding how learning occurs (). In implicit work processes, there are routines, interpretations, values, and tacit knowledge that form the basis of the work actually being performed. Here, expressions of power and contradictions are implicit, diffuse, and hidden. Skill-based actions are usually performed routinely, without effort, and automatically. The learner knows exactly what to do, has probably done it many times, and knows what the results will be. Routinised or automated actions can be performed without much conscious attention. The knowledge required already exists in the organisation (Ellström Citation2011). Rule-based actions are performed more consciously and are more time-consuming. The learner needs to evaluate the outcomes and possibly make minor adjustments to the methods used, which can be viewed as a process of improvement. It includes tasks without instructions on how the works should be performed and can be done in many different ways. It might even be that the same person performs it differently over time. This facet of work processes is difficult to examine as they are difficult to read and interpret (Ellström Citation2006). Problematically, routinised work is often self-reinforcing (March Citation1991).

Figure 1. How learning in organisations takes place in the interaction between two operating parts: explicit and implicit processes (Ellström Citation2006; Engström and Wikner Citation2017).

Explicit work processes, that is, visible work, include reflected duties and procedures that are often available in business policies and routine instructions in the framework of the work, rules, and procedures to be followed. This side of work processes is official, open, and fairly easy to grasp (Ellström Citation2006). Knowledge and reflection-based actions are performed with a higher level of consciousness, demanding time and effort. The learner needs to question established definitions of problems or solutions, retrospectively reflect on and evaluate existing knowledge, and engage in problem-solving through experimentation to create new knowledge. Ellström (Citation2006) argues that to reach this level, explicit knowledge about the task and its complexities is important. Awareness and the ability to reflect and analyse the situation are crucial. Boud, Cressey, and Docherty (Citation2006) used the term productive reflection, which they define as something that leads to, rather than concludes, action in real situations at work, producing a learning outcome needed for work processes and wider learning among people.

The outcome of how learning can be viewed as an interaction between explicit and implicit work processes in an organisation is illustrated in . When disturbances occur in the implicit work processes, there is potential for developmental learning (exploration), which occurs when groups (or individuals) within the organisation start to question established perspectives and explore new ways of working. Developmental learning, focussing on flexibility, variation, and experimentation (Ellström Citation2006) is related to the concept of exploration: ‘the use of existing knowledge’ (Adler, Goldoftas, and Levine Citation1999, 44), with a focus on flexibility, discovery, and innovation (March Citation1991).

Characteristics of this concept are variations and diversity in thought and action that promote heterogeneity. Taking risks and accepting failures – a capacity for critical reflection – along with sufficient scope and resources for experimenting with and testing alternative ways of acting in different situations also support these logics of learning. Depending on organisational actions according to disturbances and problems, learning might be stimulated or hindered by either facilitative and open-minded behaviour or neglective and ‘shutting-down’ behaviour. Executional learning (exploitation) occurs when actions in the organisation are characterised by following rules and formal procedures. To accomplish this, it is necessary to reduce variations in thought and action and promote homogeneity (Ellström Citation2006). Executional learning, (Engström and Wikner Citation2017) comparable to the adaptive learning of Ellström (Citation2006), focusses on goal consensus, standardisation, stability, and avoidance of uncertainty, and is related to the concept of exploitation, ‘the search for new knowledge’ (Adler, Goldoftas, and Levine Citation1999, 44), characterised by a focus on refinement, production, and efficiency (March Citation1991)

Engström (Citation2016) identified specific communication patterns in work groups related to particular learning logics. When exploiting knowledge, communicative actions such as instructing, finding solutions, ordering, and agreeing were frequently used. Communicative actions for exploring knowledge involved asking exploratory and critical questions, generating ideas, and building on other people’s ideas (Engström Citation2016). Positive communicative actions for increased knowledge served to share information and experiences, and to listen to and receive information, while negative communicative actions, not answering questions and withholding information, prevented learning. According to Argyris (Citation2010), it is common for groups and individuals to resist learning and engage in defensive routines such as blocking conversations, blaming others, or foreclosing on others and their reasoning to avoid critical reflection.

Ambidexterity in learning processes at work

To strengthen the work processes, learning for execution and development need to be emphasised and further understood as the concept of ambidexterity (Gibson and Birkinshaw Citation2004; Engström and Wikner Citation2017). These two learning logics often compete for resources (Smith and Tushman Citation2005; March Citation1991; Ellström Citation2011) while supporting each other in learning (Gibson and Birkinshaw Citation2004). According to March (Citation1991), exploitative and explorative activities are equally important for organisational learning, but are also mutually incompatible, representing self-reinforcing patterns of learning. Many organisations overinvest in exploitation (Levinthal and March Citation1993) at the expense of exploration (Eisenhardt, Furr, and Bingham Citation2010). These patterns are possible to overcome, but the quality of managerial work is key. Managers have a certain responsibility in managerial work and must help organisations undertake tasks that do not come naturally to them, instead of taking ‘the easy way out’. Thus, managerial work plays an important role in balancing resources and engagement for both logics. Challenging the self-reinforcement of exploration and exploitation within operations is the most important aspect of managerial work to strengthen ambidexterity in organisations (Birkinshaw and Gupta Citation2013). No single function is only explorative or exploitative; instead, even research and development departments and production units need a focus on both.

Methodology

To study learning processes in unplanned managerial work, the context of manufacturing small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) seems to be a good breeding ground due to their flat organisations, high levels of flexibility, and ad hoc work. Managerial work in these organisations is often tacit and based on experience strongly connected to single individuals (Ates et al. Citation2013). Manufacturing SMEs also lack resources to split development and executional work through separate divisions or roles. Instead, the humans working in this context need to work with both logics (Engström Citation2014; Lubatkin et al. Citation2006).

Two manufacturing SMEs, Mercury and Hydrogen, were selected based on their participation in a research project focussing on the balance between execution and development (organisational ambidexterity) ().

Table 1. Company descriptions.

A qualitative in-depth approach was applied, suitable when closely investigating a phenomenon (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, and Jackson Citation2015). Shadowing was chosen as a useful method as it provides a rich, dense, and comprehensive data set, capturing a detailed, multidimensional picture of practice (McDonald Citation2005). Interviews were used to complement shadowing. The respondents were selected based on their positions as leaders within the production unit and willingness to participate. At Mercury, data collection took place through the production manager, Arthur, and the production coordinator, Peter (with managerial work responsibilities). At Hydrogen, there was only one respondent available, the production manager, Samuel, because of the small size of the company. Pseudonyms were used to protect the participants’ identities.

The study was inspired by Mintzberg’s (Citation1973) principle of data collection. To get to know the respondents and the company, half a day was spent with each respondent before starting the three-day data collection process. To capture what was planned and unplanned, the respondents were interviewed using follow-up questions in the morning and in the afternoon. These interviews were audio-recorded (Barley and Kunda Citation2001). All activities observed during shadowing were written in a notebook to capture quotes from the managers, and their actions. A new activity was noted when the respondent changed rooms, medium, or when a new person arrived. Each activity contained tasks and actions. When the workday was over, the researcher recorded spoken thoughts on audio with an uninformed scholar. This type of work process is suitable for addressing the challenges of shadowing (McDonald Citation2005). In total, there were two days of contextual understanding and nine days of shadowing, leading to 22 voice-recorded interviews ().

Table 2. Shadowing.

After shadowing was completed a feedback session was held with the respondents. Results of the shadowing were presented and discussed to validate and deepen the understanding of the data.

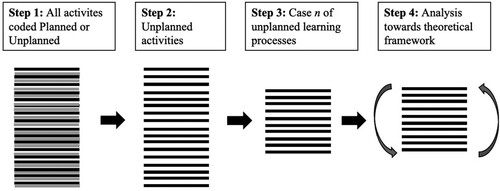

The data analysis had four steps (). In step 1, the collected activities were coded in NVivo as planned (scheduled in the respondents’ physical or mental calendar at the day’s start) or unplanned (not scheduled) with the aid of the interviews. On average, managerial work involved 102 and 108 activities per day at Hydrogen and Mercury, respectively, of which about 56% (Hydrogen) to 80% (Mercury) were unplanned. In step 2, the unplanned activities were separated from the planned activities and analysed to identify learning processes. In step 3, four different learning processes were selected because they included a number of activities and conversations with more people than just the respondent himself. Finally, in step 4, the four cases of the learning processes were analysed with assistance from the theoretical framework by analysing the actions performed in the separate activities of the managerial work.

Four cases of learning processes during unplanned managerial work

This section presents results from Hydrogen and Mercury. Within each SME, information about the production-related managerial work is first presented, followed by two cases of unplanned activities, exemplifying learning processes.

Hydrogen

Hydrogen specialises in sheet metal machining, providing their own products and customised solutions for customers. Both manufacturing and development of products is done in-house. As a strategy for change, Hydrogen identifies key issues, prioritising a few at a time, and allocates resources accordingly. Hydrogen’s core values towards customers are flexibility, speed, and user focus. Within their operations, Hydrogen uses four keywords that serve as prioritisation: safety, quality, delivery, and price.

Managerial work at Hydrogen

At Hydrogen, the CEO is the top manager, and one step down in the hierarchy is the production manager (Samuel). Samuel’s main responsibilities are to maintain production while handling employment, quality issues, and workers’ safety. To plan his day, Samuel had a calendar for meetings and he always carried a notebook to write down tasks that should be done. The notebook was constantly updated, and tasks re-prioritised.

Case 1 (transport)

This case pertains to inventory and concerns the transportation of finished goods and execution. Main participants are Samuel, an inventory worker (Jacob), and a salesperson (Lisa).

Samuel passes by inventory on his way to production, when he sees Lisa discussing something with Jacob. Samuel, unplanned, decides to join the discussion. Normally, two trucks leave Hydrogen per day, one in the morning and one after 14:00. Following the company’s strategy, customers are promised that orders of stocked goods placed before 14:00 should be shipped the same day. Jacob explains that because of the past weeks of low orders, they were usually able to ship everything in the morning lorry; therefore, he felt it unnecessary for the truck to return. Thus, he would have a daily talk with the truck driver to explain whether the second round was necessary. Earlier in the week, when Jacob cancelled the second round, Lisa, who was unaware of this, promised a quick delivery of stocked goods, which then got delayed because the driver was unavailable. Samuel, worried about what he hears, listens as Lisa and Jacob discuss possible solutions with internal communication. Jacob and Lisa summarise that she should first call him to ask whether the second lorry is available. Samuel interrupts, ‘Your solution means that we will decrease our possibility to deliver to the customer, we need to ensure that we can always deliver until 14:00. Remember our internal strategy’.

Jacob argues, ‘This is just a short-term solution. When we receive more orders, we will need both lorries again’. Samuel insists that they should follow the strategy – they cannot compromise on the promise of fast delivery. The three discuss and identify a possible solution.

Later, Samuel expresses satisfaction that he listened to the discussion, even if it was unplanned. ‘We reached a good solution; however, I fear that without me, they would have found a solution that would have deteriorated the service towards our customers’.

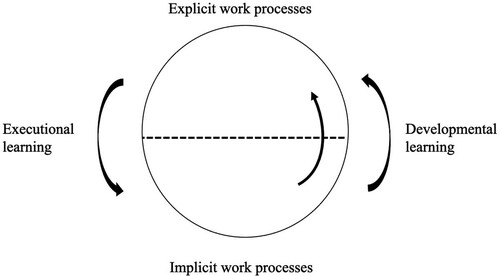

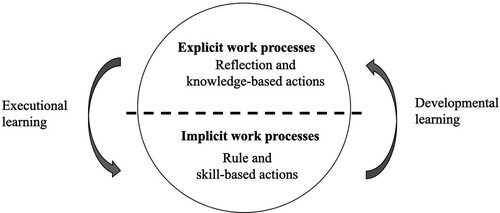

Analysis of case 1. This case illustrates the process of executional learning. The learning process was initiated when Jacob and Lisa were solving a problem, with a solution that contradicted the organisational strategy. Samuel, supported by the explications in the strategy, instructs his colleagues to act in line with the explicit rules. Such a solution-oriented communication pattern is typical of executional learning. This example shows that despite Hydrogen’s efforts to extensively work towards strategy implementation, Samuel realises that the two colleagues would have solved the problem without consulting the strategic dimension to which a solution relates. To the observer, it seems that Samuel continuously needs to be observant regarding executional learning in the organisation. The executional learning process of implementing explicit routines seems to be fulfilled, for now ().

This example indicates that executional learning is something that the organisation can never completely finish as it is necessary for the manager to urge those performing tasks to follow routines and formal processes (Ellström Citation2006), an important part of managerial work (Wallo, Ellström, and Kock Citation2013).

Case 2 (steel grilles)

This case relates to specific customer solutions, outsourcing as part of the production process, thus, development. Participants are Samuel and a steelworker (Roy).

At the daily morning meeting, Samuel shares information about a customer’s special request of 13 steel grilles. Some planning needs to be done quickly to decide which workers should produce them. The steelworkers start to discuss how the steel grilles could be produced. One of the more experienced steelworkers, Roy, asks: ‘Is it not better that MESSMO [figurative company name] produce them? They have more suitable machinery for this and could probably produce it both more cheaply and better’. Samuel, interested, answers that it could be a good idea and suggests they should continue discussing it after the meeting. Later, Samuel and Roy discuss the case and decide that Samuel should solicit an offer from MESSMO, embracing the upcoming unplanned activities. Samuel says, ‘Let us give it a try; make an experiment’, and sends the request. Shortly after, he receives an offer, reviews it, and is surprised by how beneficial it is. There is a time constraint, but Samuel completes the order and asks for expedient delivery. MESSMO answers quickly – they should have the steel grilles by the following afternoon.

The delivery of the steel grilles is partly delayed, but Hydrogen still delivered to the customer in time. Samuel is satisfied; he explains this as innovation by Hydrogen. In discussion, Roy and Samuel conclude that it is impossible for Hydrogen to have all necessary machinery; instead, Hydrogen should consider what machinery surrounding plants have and make use of them.

Analysis of case 2. This case illustrates developmental learning. The learning process was initiated when an experienced worker questioned the standard procedure. Samuel explored the idea further, with what he called an ‘experiment’. By questioning and performing the experiment, they went from an implicit work process to a reflective and conscious, explicit work process. In the future, Samuel wants to make it routine to investigate whether this type of product should be sourced or manufactured. In this example, this developmental learning process seems to be fulfilled, but not yet routinised ().

It was necessary for the manager to capture the idea and switch focus from mainly planning the operation towards trying out something new. The encouragement of reflection, critical questioning, and generation of ideas – by reflection and knowledge-based actions – is an important part of managerial work.

Mercury

Mercury specialises in metal cutting with a highly advanced machine park and customers in defence and medical technology, with extreme demands of quality. The incoming materials can be expensive, so wrongly produced pieces can be costly for the company. The operator’s work consists of registering details in the machines, waiting until the machine is ready, performing quality control on the piece by measuring it, changing the tooling in the machines, and starting the next order. Production runs day and night and during weekends, so there are four alternating shifts.

Managerial work at Mercury

The managers talked about Mercury as being in constant change. They want their managerial work to be explorative to find ways of working to standardise production. For problem identification, they often use a concept called the ‘5 Whys’ to identify the root cause of a problem by repeating the question, ‘Why?’ High in hierarchy is the plant manager, Simon, followed by Arthur, the production manager. Arthur is responsible for the production, including master planning, ensuring that the inventory is sufficient and that orders are produced in time for shipping. Arthur had numerous ongoing projects for production improvement. To plan his days, Arthur used his calendar. During the shadowed days, cancelled meetings were common, resulting in new or rescheduled meetings. The next step in the hierarchy is the production coordinator, Peter. Peter’s main responsibility is to make a more detailed production plan, solve imminent problems within production, attend meetings, prioritise and allocate resources, and repair broken machines. His responsibility was also developmental work, but he seldom found time for it.

Case 3 (measurements)

This case occurs in production and concerns quality issues, a common challenge for Mercury, and execution. Participants are Peter, operator R (Richard) from the day shift, operator I (Isaac) and operator W (Wilfred) from the evening shift, and Simon.

Richard, unplanned, approaches Peter with concerning news regarding quality. Richard explains the work he had done the day before, starting a new order with a special, expensive material, with long machine time per piece. The machine itself was bottlenecked and highly prioritised. After setting up the machine, Richard ran five pieces whose measurements were inspected, and when his shift was over, he handed the machine over to the evening shift and went home. When Richard started his shift this morning, he noticed wrongly produced pieces at the machine. The fault was so evident that he did not need to measure the pieces. Therefore, during the evening and night shifts, the machining had performed incorrectly.

Peter realises that this is serious, ‘We need to do a 5 Whys on this. The pieces need to be measured and controlled’.

Richard explains, ‘It is because the operator who ran the machine didn’t know what he was doing’.

Peter says, ‘You should have shown him; that is part of your job’.

Richard replies, ‘I did show Wilfred, but from what I can see, Isaac ran it’.

The discussion ends by both men agreeing that they should bring it up at the morning meeting. Later at the meeting, Simon is informed about the pieces. He emphasises, ‘This needs to be handled’. That afternoon, Simon, Richard, and Peter gather with the operators, Isaac and Wilfred, from the evening shift to find out what happened. Richard explains; Isaac and Wilfred stay silent. Simon listens to Richard’s explanation, but instructs him to provide a better handover. After Simon leaves, Isaac asks what the problem was with the detail – he did not really understand the issue. Together, Peter, Richard, and Isaac walk to the machine to inspect the details. The fault is clearly visible, but Isaac still looks confused. Peter asks Isaac and Wilfred how often they measure the details. They avoid answering, and the silence is broken by Richard, who explains what the measurements should be.

Peter leaves them, stressed by all the work that he had to put aside. Later, Isaac approaches and asks, ‘How was it again with the measurements regarding the detail?’ Peter answers, frustrated that he does not know, and that it is important that the operator listens carefully during the handovers.

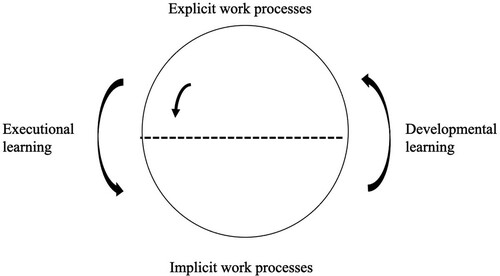

Analysis of case 3. The measurement example illustrates a company stuck in an explicit work process, not moving towards the implicit. The learning process was initiated by a discrepancy between the actions of the operators – likely rule- or skill-based – who did not follow the explicit work process (the instructions) set by Mercury. This discrepancy between implicit and explicit work processes appeared as a learning potential. Simon blamed Richard, who identified the problem, and Isaac, who caused the problem, stayed silent. This behaviour of hiding information and staying silent, hindered developmental learning. The behaviour also seemed to hinder the movement from making the explicit work process implicit, hindering executional learning. As the example evolves, Richard is blamed and told that he should have done a better handover to the next person – a defensive act by Simon to avoid critical reflection (Argyris Citation2010). Instead, Richard’s handover is a work process that is not explicit but rather skill- or rule-based, thus, implicit. The handover is also not something that Simon or Peter focus on in development. Neither Simon nor Peter used this event as a learning opportunity to increase the operators’ competence in learning how to read and follow explicit instructions. They shut down Richards’s reasoning, blocking learning, and no further reflection was done. When Simon left, Isaac asked what the problem was with the pieces. Even after the new instructions from Richard, Isaac approached Peter to ask about the instructions. Peter, who appeared stressed, answered in frustration. It seems as if executional learning process was hindered for the moment, resulting in frustration ().

The managerial work failed to capture the opportunity for executional learning

Case 4 (machine collision)

This case occurs in production and concerns the problem of machine collisions and development. Participants are Arthur, Peter, Simon, a technician (James), a programmer (Daniel), and three operators (Tom, Nick, and John) from the day shift.

The highly automated machines are sensitive to incorrect programming by the operators. Operators need to change programmes during setups, daily, by putting numbers into the machine system. The machine moves its tools with great force and resetting the machine after a collision takes many hours of work by the most skilled technicians. During an informal morning meeting, Peter informs Arthur about a few minor accidents and problematises the setup. Peter says, ‘It is problematic with numbers. If the operators write the wrong numbers, the machine collides. How can we handle this better?’ Before rushing away, Arthur asks Peter to continue to think about it. Later, when Arthur and Peter have another informal meeting, Peter pushes for a formal meeting on the matter. Arthur is positive and asks if Peter could be responsible for it. Peter, who already has much to do, sighs, but does not explicitly disagree.

During the formal morning meeting the next day, Arthur is informed that a machine collided on the night shift. Simon, in attendance, is calm but firm when he says, ‘This is very serious! Arthur, you collect the concerned group and perform a 5 Whys. We must solve this!’ This led to a number of unplanned activities for Arthur. When the meeting is finished, Arthur, Peter, and Daniel discuss the collision.

‘No one told me about the collision. However, it seems like someone mixed up the codes during setup’.

‘We have to solve this; will we really get anywhere with the 5 Whys? We already know what the problem is; the operators need to learn’.

The ‘5 Whys’ meeting starts at 9:30 – participants are Arthur, Peter, James, and operators Tom, Nick, and John. Arthur explains that they should perform a ‘5 Whys’, but that he has not done so before. The team defines the problem: they crashed a machine. They then struggle when working through the 5 Whys. Why 1: Tom explained that they believe that the wrong order was scanned into the machine system. Why 2: Tom said, ‘Well, they had to change order, because the order before was completed’. The group is caught in a discussion regarding why the orders need to be changed. Peter asks, ‘How do other companies change orders?’ The focus suddenly changes. The group concludes that Why 2 is carelessness from the operators. Peter says, ‘We need to ask those who did it’. John adds, ‘Should we change orders during the night shift [to account for tiredness]?’ James asks, ‘Can we limit the options in the software?’ They identify Why 3: human error. Peter raises the question of competence: are the operators on the nightshift trained to do setups? If not, it is serious. Peter says, ‘By the information I had, it is unclear who made the change of the order since it was two operators working on the machine’. The 25-minute-long meeting ends since Arthur has to attend another meeting.

When Arthur meets Simon, he expresses the 5 Whys meeting’s difficulties. Simon asks if anything can be done with the software. Later, Arthur tries to summarise the 5 Whys meeting and creates some diffuse and abstract activities. He sighs and says, ‘I am not sure that this is right, but it is at least something, instead of nothing’. In the afternoon, Arthur, Peter, and an operator from the evening shift discuss the machine collision. The operator is sure: ‘It is carelessness’. They all nod in agreement.

Analysis of case 4. This example illustrates being stuck in an implicit work process hindering moving towards an explicit work process. Mercury has explicit routines of how to make the setup, but the process does not work. Peter, who was aware of the problem, had started a discussion to focus on it. He intended to make the implicit work process more explicit, identifying the opportunity for developmental learning, thereby, initiating developmental learning. However, both managers appeared busy and seemed to hope that the other one would start a project about it. It seemed as if they were stuck in exploitation – something common for managers. Arthur and Peter blamed the operators’ incompetence, an expression of their interpretations and values that stops them from reflecting, hindering developmental learning. During the 5 Whys meeting, the group reaches for developmental learning when they give examples of things they should explore. However, after the meeting ends, they relapse into ‘what they already knew’, and instead of continuing to ask questions and building on each other’s ideas, they fell into a defensive routine, blaming the operators – something that is common for groups when there is resistance to learning. This resistance could also stem from the stress all the individuals were under, stuck in all the other exploitative work they had, and not finding the time to reflect. The developmental learning processes are currently on hold ().

Summary

The two cases at Hydrogen were both fairly delimited concerning rather uncomplicated work processes, including few employees, and both learning processes appeared to have been fulfilled, at least temporarily. The unplanned managerial work played a critical role in Hydrogen’s learning processes, especially in deciding or encouraging what should be reflected on – the developmental mode – and what should be implemented – the executional mode. If the manager would have neglected or turned down the unplanned managerial work, the learning processes would likely never have occurred, and the outcome would have been different, deteriorating service to the customer (case 1) and less profit (case 2).

The two cases at Mercury contained more complex work processes, including more roles and humans, and the learning process was often hindered by defensive actions. This could relate to the fact that these activities were unplanned, interrupting other things that the managers felt the need to do in an already stressful workplace, hindering their reflections. The cases also indicate that the managers appear to be stagnated within one logic of learning, to either encourage the operators to follow set instructions (case 3) or to try to develop a non-functioning process (case 4). These complex, unplanned learning processes could indicate that separating the learning logics does not work, and instead, a dualistic view, appropriate when having intricate and complex problems, could be more suitable (Farjoun Citation2010).

Ambidextrous learning in complex unplanned managerial work

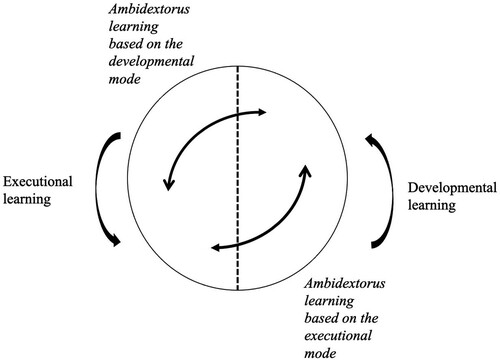

The results from cases 3 and 4 show that in unplanned managerial work, when part of complex work processes, the approach of only focussing on one logic of learning is dysfunctional, instead, a dualistic view is needed. Thus, we identify a vertical line () between the two logics of learning rather than between the explicit and implicit processes. In case 3, the learning processes are stagnated in the executional learning mode but would benefit from including the developmental learning mode. In this executional mode, the existing work processes need to be highlighted within managerial work to support developmental learning and productive reflection (Boud, Cressey, and Docherty Citation2006), and to search for new knowledge (Adler, Goldoftas, and Levine Citation1999) – a series of movements we call ambidextrous learning based on the executional mode.

In case 4, the learning process is stuck in the developmental learning mode but would benefit by including the executional learning mode. In this developmental mode, the complex work processes need to be highlighted in the managerial work to support executional learning, continuously encouraging the organisation and the individuals to increase their competence by using existing knowledge (Adler, Goldoftas, and Levine Citation1999) – a series of moves which we call ambidextrous learning based on the developmental mode ().

As Birkinshaw and Gupta (Citation2013) suggest, managerial work is essential for challenging the organisation. During complex work processes, unplanned managerial work is a potential to identify needs for new and existing learning areas, moving between the two logics of developmental and executional learning as an ambidextrous learning process. Our findings show that unplanned managerial work can act as a potential for ambidextrous learning in organisations; thus, unplanned managerial work needs to be valued in fostering learning in an organisation as a whole (Lam Citation2019). Our findings identify two ambidextrous learning logics suitable when unplanned managerial work is part of complex work processes.

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to understand learning processes during unplanned managerial work in practice, from an ambidextrous perspective. We investigated unplanned managerial work in manufacturing SMEs and analysed four different learning processes. Despite the small sample and choice of one sector industry, we believe that professionals in other domains could relate to our cases, and that other researchers would recognise the patterns as we did. Using observation through shadowing in combination with interviews, high quality data were collected which reduced the ‘risk’ of data being biased by only leaning on managers’ own experience, which could be problematic (Moqvist Citation2005). With increasing interest in learning in organisations (Dixon Citation2017), we encourage other researchers to join us in studying unplanned work in complex work processes, from an ambidextrous learning perspective with a dualistic approach (Farjoun Citation2010), thus, connecting learning with work (Lizier and Reich Citation2020).

Our results involve developmental and executional learning, and they appear as processes, as opposed to a one-time activity. Managers needed to encourage and remind the people in the organisation to take small steps to learn – through work. Our findings support Wallo, Ellström, and Kock (Citation2013) in that managerial work is important for learning in organisations and plays an important role in balancing resources and engagement (Birkinshaw and Gupta Citation2013). They also validate Antonacopoulou (Citation2006), in that managerial work is a collective process which acts as a link between the organisation and the individual. When unplanned managerial work is part of complex work processes, we suggest a merged learning approach where both logics of learning are involved. As Engeström (Citation1999) noted, expansive learning is not purely expansive, which we confirmed here, and executional learning could have traces of or be triggered by developmental learning. Our result shows two ambidextrous learning logics as a duality (Farjoun Citation2010) in complex work processes, complimenting Ellström’s (Citation2006) learning logics.

Our results confirm that learning processes occur in unstructured, unplanned, and informal work processes, thereby, strengthening the conclusions of Eraut’s (Citation2004) and Moqvist’s (Citation2005) work. This fluid work setting appears to be a challenge but a good source of learning potential, according to what Lizier and Reich (Citation2020) also identified. We highlight the importance of managers to explicitly value these unplanned learning processes, especially considering the discrepancy identified by Moqvist (Citation2005). By assenting to and valuing unplanned work, both research and practice could benefit from its learning outcomes. In line with Eraut (Citation2004), our results support the idea that learning occurs in unplanned processes, and we highlight the discrepancy between a planned organisation (Slack and Brandon-Jones Citation2018) and unplanned managerial work. An area that could benefit from more research.

Our results also show that when managers appeared to be stressed – reflective learning (Knipfer et al. Citation2013) and productive reflection (Boud, Cressey, and Docherty Citation2006) were hindered – teams seemed to arrive at rushed conclusions, creating defensive routines; this hinders learning in organisations. Organisations need to take this negative learning seriously (Argyris Citation2010), which further underscores the need for more studies on these kind of learning processes. As a practical implication, we encourage managers to embrace unplanned managerial work processes. Further, when dealing with complex work processes, they should be viewed in light of the two contradictory but interdependent learning logics.

Conclusion

Managerial work is an important part of learning in organisations, where a great deal of learning occurs during unplanned work. This paper has its starting point in two existing logics of learning, executional and developmental. By studying the unplanned managerial work, we identified a need for two ambidextrous learning logics, based on either the executional or developmental mode, within complex work processes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Knowledge Foundation under Grant number KK20170312, and was part of the research project, Innovate.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adler, Paul, Barbara Goldoftas, and David Levine. 1999. “Flexibility Versus Efficiency? A Case Study of Model Changeovers in the Toyota Production System.” Organization Science 10 (1): 43–68. doi:10.1287/orsc.10.1.43.

- Alvesson, Mats, and André Spicer. 2011. “Once Again: The (Un) Bearable Slipperiness of Leadership.” In Metaphors We Lead By: Understanding Leadership in the Real World, edited by Mats Alvesson, and André Spicer, 194–205. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Antonacopoulou, Elena P. 2006. “The Relationship Between Individual and Organizational Learning: New Evidence from Managerial Learning Practices.” Management Learning 37 (4): 455–473.

- Argyris, Chris. 2010. Organizational Traps. Leadership, Culture, Organizational Design. New York: Oxford University Press Inc.

- Ates, Aylin, Patrizia Garengo, Paola Cocca, and Umit Bititci. 2013. “The Development of SME Managerial Practice for Effective Performance Management.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 20 (1): 28–54.

- Barley, Stephen R., and Gideon Kunda. 2001. “Bringing Work Back In.” Organization Science 12 (1): 76–95.

- Berends, Hans, Kees Boersma, and Mathieu Weggeman. 2003. “The Structuration of Organizational Learning.” Human Relations 56 (9): 1035–1056.

- Birkinshaw, Julian, and Kamini Gupta. 2013. “Clarifying the Distinctive Contribution of Ambidexterity to the Field of Organization Studies.” Academy of Management Perspectives 27 (4): 287–298.

- Boud, David, Peter Cressey, and Peter Docherty. 2006. Productive Reflection at Work: Learning for Changing Organizations. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Boud, David, and Paul Hager. 2012. “Re-thinking Continuing Professional Development Through Changing Metaphors and Location in Professional Practices.” Studies in Continuing Education 34 (1): 17–30.

- Cressey, Peter, David Boud, and Peter Docherty. 2006. “The Emergence of Productive Reflection.” In Productive Reflection at Work: Learning for Changing Organizations, edited by David Boud, Peter Cressey and Peter Docherty. 11–26. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Dixon, Nancy M. 2017. The Organizational Learning Cycle: How We Can Learn Collectively. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Easterby-Smith, Mark, Richard Thorpe, and Paul R Jackson. 2015. Management and Business Research. London: Sage.

- Edmondson, Amy. 2012. “Teamwork on the Fly.” Harvard Business Review 90 (4): 72–80.

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M., Nathan R. Furr, and Christopher B. Bingham. 2010. “Microfoundations of Performance: Balancing Efficiency and Flexibility in Dynamic Environments.” Organization Science 21 (6): 1263–1273. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0564.

- Ellström, Per-Erik. 1992. Kompetens, utbildning och lärande i arbetslivet. Problem, begrepp och teoretiska perspektiv. Stockholm: Norstedts Juridik AB.

- Ellström, Per-Erik. 2001. “Integrating Learning and Work: Problems and Prospects.” Human Resource Development Quarterly 12 (4): 421–430.

- Ellström, Per-Erik. 2002. “Time and the Logics of Learning.” Lifelong Learning in Europe 7 (2): 86–93.

- Ellström, Per-Erik. 2006. “The Meaning and Role of Reflection in Informal Learning at Work.” In Productive Reflection at Work, edited by David Boud, Peter Cressey, and Peter Docherty. 43-53. New York: Routledge.

- Ellström, Per-Erik. 2011. “Informal Learning at Work: Conditions, Processes and Logics.” In The Sage Handbook of Workplace Learning, edited by Margaret Malloch, Len Cairns, Karen Evans, Bridget N O′Connor. 105–119. London: Sage.

- Ellström, Eva, Bodil Ekholm, and Per-Erik Ellström. 2008. “Two Types of Learning Environment.” Journal of Workplace Learning 20 (2): 84–97.

- Engeström, Yrjo. 1999. “Innovative Learning in Work Teams: Analyzing Cycles of Knowledge Creation in Practice.” In Perspectives on Activity Theory, edited by Yrjö Engeström, Reijo Miettinen, Raija-Leena Punamäki. 377–404. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Engström, Annika. 2014. Lärande samspel för effektivitet: En studie av arbetsgrupper i ett mindre industriföretag. Linköping: Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Engström, Annika. 2016. “Arbetsmöten-arenor för samspel och lärande.” Pedagogisk Forskning i Sverige 21 (3–4): 283–305.

- Engström, Annika, and Joakim Wikner. 2017. “Identifying Scenarios for Ambidextrous Learning in a Decoupling Thinking Context.” Paper presented at the IFIP International Conference on Advances in Production Management Systems.

- Eraut, Michael. 2004. “Informal Learning in the Workplace.” Studies in Continuing Education 26 (2): 247–273.

- Farjoun, Moshe. 2010. “Beyond Dualism: Stability and Change as a Duality.” Academy of Management Review 35 (2): 202–225.

- Fayol, Henri. 1916. General and Industrial Management. London: Pitman.

- Florén, Henrik. 2005. “Managerial Work and Learning in Small Firms.” PhD thesis, Chalmers University of Technology.

- Gibson, Cristina B, and Julian Birkinshaw. 2004. “The Antecedents, Consequences, and Mediating Role of Organizational Ambidexterity.” Academy of Management Journal 47 (2): 209–226.

- Goh Yuen Sze, Adeline. 2019. “Rethinking Reflective Practice in Professional Lifelong Learning Using Learning Metaphors.” Studies in Continuing Education 41 (1): 1–16.

- Knipfer, Kristin, Barbara Kump, Daniel Wessel, and Ulrike Cress. 2013. “Reflection as a Catalyst for Organisational Learning.” Studies in Continuing Education 35 (1): 30–48.

- Lam, Alice. 2019. “Ambidextrous Learning Organizations.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Learning Organization, edited by Örtenblad Anders, 163–180. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Levinthal, Daniel A, and James G. March. 1993. “The Myopia of Learning.” Strategic Management Journal 14 (S2): 95–112. doi:10.1002/smj.4250141009.

- Lizier, Amanda L, and Ann Reich. 2020. “Learning Through Work and Structured Learning and Development Systems in Complex Adaptive Organisations: Ongoing Disconnections.” Studies in Continuing Education, 1–16. doi:10.1080/0158037X.2020.1814714

- Lubatkin, Michael H, Zeki Simsek, Yan Ling, and John F. Veiga. 2006. “Ambidexterity and Performance in Small-to Medium-Sized Firms: The Pivotal Role of Top Management Team Behavioral Integration.” Journal of Management 32 (5): 646–672.

- March, James G. 1991. “Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning.” Organization Science 2 (1): 71–87.

- McDonald, Seonaidh. 2005. “Studying Actions in Context: A Qualitative Shadowing Method for Organizational Research.” Qualitative Research 5 (4): 455–473.

- Mintzberg, Henry. 1973. The Nature of Managerial Work. New York: Harper & Row.

- Moqvist, Louise. 2005. Ledarskap i vardagsarbetet: en studie av högre chefer i statsförvaltningen. Institutionen för beteendevetenskap. Linköping: UniTryck.

- Nonaka, Ikujiro, and Hirotaka Takeuchi. 1995. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Create the Dynamics of Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Örtenblad, Anders. 2018. “What Does “Learning Organization” Mean?” The Learning Organization 25 (3): 150–158.

- Santa, Mijalce. 2015. “Learning Organisation Review – A “Good” Theory Perspective.” The Learning Organization 22 (5): 242–270.

- Sayles, Leonard R. 1964. Managerial Behavior: Administration in Complex Organizations. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Senge, Peter. M. 1990. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Bantam Doubleday.

- Slack, Nigel, and Alistair Brandon-Jones. 2018. Operations and Process Management: Principles and Practice for Strategic Impact. Harlow: Pearson UK.

- Smith, Wendy K, and Michael L. Tushman. 2005. “Managing Strategic Contradictions: A Top Management Model for Managing Innovation Streams.” Organization Science 16 (5): 522–536.

- Tengblad, Stefan. 2012. The Work of Managers: Towards a Practice Theory of Management. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wallo, Andreas, Per-Erik Ellström, and Henrik Kock. 2013. “Leadership as a Balancing Act Between Performance-and Development-Orientation.” Leadership & Organization Development Journal 34 (3): 222–237.