ABSTRACT

This article illustrates how schooling Innovative Learning Environments (ILE) deploy a future-focused imaginary for a perfectly self-managing society. New building design, coupled with this imaginary, creates possibilities for new ecologies of practices in which there are reframed relationships and pedagogical opportunities. We use the theory of practice architectures to demonstrate how practices in ILE are shaped through discourses, workplace activities, and power relations. We report data from a qualitative case study investigating the implementation of ILE in Aotearoa New Zealand. Interviews were conducted with four principals leading pedagogical transitions in newly built ILE. Data were categorised to explore changes in the cultural-discursive, material-economic, and social-political arrangements of the built spaces in which educators work and students learn. The data paint a vision of a ‘perfectly self-managing society’ where learners and teachers enact subjectivities immersed in pastoral forms of control. There is manufactured uncertainty (where technical solutions are constantly called for to ensure ‘progress’) and this ongoing variation and change destabilise prior practices. This article has relevance to those who work in contexts beyond education – where built spaces and the associated discourses of collaboration, agility and flexibility are elements of transitions to a new imaginary in the workplace.

Introduction

New generation learning spaces or innovative learning environments (ILE) are premised on a future focused imaginary, which incorporate an expectation that leaders address a shift in teacher pedagogy to embrace a set of new practices. Not only do these environments provide settings for educational policy enactment, but they play an active role in operationalising policy (Wood Citation2019). A twenty-first century learning imaginary is premised on a political economy discourse, which produces a focus on ongoing change and ‘manufactured uncertainty’ in the interests of the transformation of work (Scott and Marshall Citation2009, 638). To effect the required changes for migration to ILE, school leaders are charged with leading this transition. This is particularly the case in Aotearoa New Zealand where ILE building design has been mandated by the government (Ministry of Education Citation2011).

Drawing data from principal interviews, we address the specific ways in which the built spaces of new and refurbished school buildings contribute to changing patterns of educators’ work and the subsequent implications for workplace learning. We explore the practice architectures (Kemmis and Grootenboer Citation2008; Kemmis et al. Citation2014) described by school leaders working in newly built or refurbished schooling spaces to consider how practices in these ‘new generation spaces’ are shaped through discourses, workplace activities, and power relations. Using a practice theory framework, we examine the nexus of progressive and instrumentalist approaches to different dimensions of schooling (e.g. leading, professional learning, teaching, student practices, and reflection) (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). This article specifically addresses the power and politics of leadership, not leading pedagogy. Leadership is seen as practice that ‘emerges and unfolds through day-to-day experiences such that its material and social conditions’ and these elements are seen to ‘constitute leadership rather than to predict it’ (Raelin Citation2016, 134). That said, leaders have a pivotal role in ‘changing practice and ensuring change is sustained’ (Wylie et al. Citation2018, 82).

A range of terms is used to describe the socio-material dynamics of learning spaces developed to address the envisaged pedagogical epoch of the twenty-first century. These environments are purposely designed to foster flexibility in pedagogical approach, deprivatised practice, professional collaboration, and visibility. These designs incorporate a sense of openness with a range of purpose built spaces in proximity to a large central hub. There is extensive use of glass, flexible furniture, and an emphasis on ‘agility’, in that spaces can be created as needed for various purposes. Although there are a range of terms in use that include ‘new generation learning environments’, ‘flexible learning spaces’, and ‘non-traditional environments’, the OECD (Citation2013, Citation2017) have curated policy and research to frame them as ecosystems of educators, learners, policies, resources, and social interactions. ‘Innovative Learning Environments’ are ‘an organic, holistic concept—an eco-system that includes the activity and the outcomes of the learning’ (OECD Citation2013, 11). In these ecosystems, teaching and learning are re-imagined along progressive lines for a new age.

In the last ten years, twenty-first century learning discourse has become a powerful influence in NZ schools (Charteris, Smardon, and Nelson Citation2016). We commence this article by conceptualising reflexive modernity, pastoral control, and how the twenty-first century learning imaginary relates to the practices associated with ILE. We outline the theory of practice architectures and the qualitative study undertaken with Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) principals. Detailing features of the transition from the twentieth to the twenty-first century imaginary, we consider leader practices in managing this transition that are associated with leading, professional learning, teaching, student learning and reflection in ILE. The article concludes with a discussion on the contradictions associated with the transition to ‘modern learning practices’ in ILE (Benade Citation2017, 32). The article contributes to extant literature through providing an account of how practices in ILE are shaped through discourses, workplace activities, and power relations, with the recognition that waves of innovation are inherently political.

Reflexive modernity and the ‘Velvet Cage’

‘Reflexive modernity’ pertains to an ‘epochal differentiation between different stages in the process of modernisation’ (Rasborg Citation2012, 14). Reflexive modernity is premised on the notion of continuous improvement and the demarcation between contemporary society and the ‘classic industrial society’ (Rasborg Citation2012, 4) with its associated model of multi-classroom, multi-teacher schools. Conceptually, ‘reflexive modernity’ enables us to understand how leaders today work in an era characterised by uncertainty and meta-change with an emphasis on re-structuring and re-conceptualising what came before (Beck, Bonss, and Lau Citation2003). Principals face both uncertainty and radical indeterminacy, where decisions to mitigate risk, that used to be linear and determinate, are no longer so.

The nature of principals’ professional work has changed over the last 30 years with the encroachment of market logics. This move is aligned with evolving forms of public management and governance (Connolly and Hughes-Stanton Citation2020; Lingard and Sellar Citation2012). Market logic is inherent in learning practices that focus on personalising learning, self-regulation, student agency, and student voice work for school improvement. These practices are intended to engender what we describe as the ‘perfectly self-managing society’. Learners and teachers engage in producing forms of collective, pastoral control where peers (teachers and students) are able to hold each other to account through social processes of learning and teaching. Linked with Foucault’s (Citation1977) panoptic metaphor, this hypervisibility has been described by Schutz (Citation2004) as a ‘velvet cage’. While disciplinary forms of control engender resistance, subtle forms of pastoral power bring people into line through workplace practices where colleagues work in close proximity in order to surveil each other. Pastoral power operates ‘subversively and indirectly’ (Schutz Citation2004, 15). Pastoral power saturates ILE and coheres in discourses of progressivism and neoliberalism which are articulated in the pedagogical imaginary.

Progressive education and twenty-first century learning

Over the last two decades there has been international interest in ensuring that school building reflects the perceived twenty-first century epoch and aspirations for learners. For example, the ‘Building Schools for the Future’ (BSF) programme in the United Kingdom reflected this worldwide interest in educational building (Mahony, Hextall, and Richardson Citation2011). The programme aimed BSF at rebuilding and refurbishing all 3500 secondary schools in England between 2005 and 2020 and ‘the use of high quality information and communications technology (ICT) in these new bespoke schools was seen as a means of transforming the learning experience of students and raising attainment’ (House of Commons: Education and Skills Select Committee Citation2007, 12). This reflects a conceptualised relationship between school design and pedagogic practices (Tse et al. Citation2015).

In NZ the strong tradition of progressive education has had a focus on ‘child-centredness, experiential learning, an emergent curriculum, a holistic pedagogy and the fostering of creativity’ (Mutch Citation2013, 99). Progressivist discourse which has its roots in the work of John Dewey locates the learner as agentic, where there is an ‘activist relationships with the natural world’ and ‘risky experimentation and creativity’ (Kalantzis and Cope Citation2012, 45). Although the ‘21st century learning’ rhetoric around ‘21st century skills’ has become a creedal mantra with its emphasis on digital technologies, and modern pedagogical practices, the term is a placeholder that is used to ‘idealize abstract future skills’ that are ‘devoid of the realities of lived experiences in educational contexts’ (Mehta, Creely, and Henriksen Citation2020, 360). The rationale for ‘21st century learning’ is driven by a conception that schools need to respond to forces of globalisation and the associated rapid advances in technology, where new sorts of learning and forms of knowledge are required for students as citizens and future potential workers (Mishra and Mehta Citation2017). In short, ‘21st century learning’ becomes a proxy for an uncertain and unknown future.

Educators envisage the future of an ideal society that correspond with discourses that stem from the OECD literature on ILE (Citation2013, Citation2015). Thus in their practices, educators fashion a microcosm of the society that they anticipate will come to be. Previously, the vision for schooling (and associated policy and practices) responded to the current needs of the society in which it was embedded. Now however, with the exponential change that has become accepted and expected within education systems, there is a zealotry around the conception that we are preparing students for an unknown future. Through the socio-material structuring of practices in ILE, a vision for education is promoted that hybridises discourses of progressive education with neoliberalism. As Couch (Citation2018, 128) observes, ‘New Zealand’s traditionally progressivist tendencies in education have cloaked a neoliberalist undercurrent at work within this ILE imaginary.’

Innovative learning environments in Aotearoa

In NZ there has been a need for large scale building development due to significant earthquake damage and widespread issues with poorly constructed leaky buildings. The Ministry of Education (Citation2015) mandated an expectation that all school-based learning environments address the ILE criteria in their design. Designing Schools in New Zealand – Requirements and Guidelines (DSN) (Ministry of Education Citation2015) is a document that guides school decision making and serves as a powerful policy lever to shift practices in Aotearoa New Zealand schools. It explicitly links building design and pedagogy in ILE, with an emphasis on teachers’ collaboration and co-teaching. Learning spaces are to be designed to promote a wide range of teaching strategies including collaborative teaching with groups of up to five teachers. There is an emphasis on how ‘effective spaces’ permit teachers to offer learners choices, pertaining to what, how, where, why, and with whom they are learning (Ministry of Education Citation2015, 33).

Leaders work from New Zealand education policy documents to design schools that afford specific types of practices associated with ‘modern learning pedagogy’ (Ministry of Education Citation2015, Citation2020). This combines elements of: increased collaboration within and across schools, students’ use of technologies, engagement of student voice, with emphasis placed on learner agency, and the explicit use of Assessment for Learning (Charteris, Smardon, and Nelson Citation2017, 810). Blackmore et al. (Citation2011) argue that the transformation of school building design creates possibilities for new partnerships and pedagogical opportunities. Changes in ‘spatial, temporal, cultural, structural, communicative, social and semiotic practices’ in school communities mobilise discourses of reform (Blackmore et al. Citation2011, 3).

The move to ILE ideology has seen: the redesign of classrooms with walls knocked down; classes of up to 90–120 students grouped together in open spaces; an emphasis placed on team and collaborative teaching; importance placed on the seamless use of technologies; the valuing of student voice and learner agency; the strategic use of formative assessment practices to foster student self-management, engagement, and learning; and the ‘de-siloing’ of discipline boundaries with the integration of curriculum (Charteris, Smardon, and Nelson Citation2017). Taken together, these elements can be seen as a means to reshape teaching practice and even the identity of teachers as they rethink their pedagogical work in these spaces (Charteris and Smardon Citation2018a).

The move to ILE in NZ brings the prefigurings of site ontologies into sharp relief. There is a conjuncture between ILE and traditional designs of classroom spaces with different conceptions of: how knowledge is transmitted or co-produced; notions of what constitutes desirable pedagogy; and how power dynamics between students and teachers are conceptualised and produced within the dynamics of classroom relations. It is in this conjuncture that leaders develop leading practices that support transitions in other practices (professional learning, pedagogy, student learning and reflection) to align with a twenty-first century imaginary.

The study

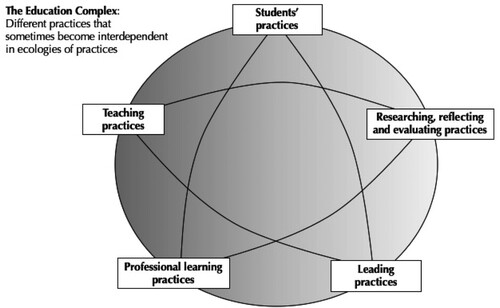

The theory of practice architectures and the concept of ecologies of practices () (Kemmis et al. Citation2014) inform this research. Practices are the human activities which emerge amidst the materiality of sites. Sites are intersubjective spaces that create the enabling and/or constraining conditions through which practices of leading and teaching are produced (Wilkinson and Kemmis Citation2015). Practices are cooperative human activities that are sustained through combinations of arrangements that form practice architectures (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). Practices comprise the sayings (and thinking), doings, and relatings that hang together when people engage in workplace projects. Sayings involve discourse and are produced in semantic space when people engage in intersubjective encounters. Doings are enacted in material space–time as people engage in activities in the physical locations of workplaces. Relatings are produced in social space when people cohere around a project and negotiate power relationships and affective encounters. Sayings, doings and relatings are held in place by the interrelated cultural-discursive, material-economic and social-political arrangements of situated settings. These practice dimensions make practices possible.

Cultural-discursive arrangements are the resources … that prefigure and make possible particular sayings in a practice, for example, languages and discourses used in and about a practice …

Material-economic arrangements are resources … that make possible, or shape the doings of a practice by affecting what, when, how, and by whom something can be done …

Social-political arrangements are the arrangements or resources … that shape how people relate in a practice to other people and to non-human objects; they enable and constrain the relatings of a practice. (Mahon et al., Citation2017, 9–10)

The leaders’ articulation reflected the Education Complex which can be seen as ecologies of practices in ILE (). This ecological focus implies that changing practices need to be “analysed and understood in relation to a set of interrelated practices that together compose what we refer to as the Education Complex, namely leading … professional learning … teaching, student learning, and researching and reflecting on practices” (Wilkinson and Kemmis Citation2015, 344). These practices can be ecological, although the degree to which this is so does depend on the educational context. We use these interrelated practices leading, professional learning, teaching, student learning, and reflecting (taken together as the Education Complex) as a conceptual framework for analysing the interviews of the four school leaders who work in Innovative Learning Environments. We reviewed transcripts of interviews with school leaders to theme for initial codes to reach an ontological understanding. We then analysed the practices in greater detail using the table of invention.

Table 1. Details of participants.

We took a three step approach to analysis. In the first layer of analysis we took a thematic approach. Initially we coded the transcribed interviews with the four principals in NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software programme. This enabled us to locate samples of data that we considered reflected references to sayings, doings, and relatings associated with various practices in ILE. In the second layer, the pages of coded NVivo data were inductively analysed by two of us separately, looking at the data with the question ‘What do the sayings in the interview indicate about the past that is meant to be left behind and the future that is called into being?’ We examined the Education Complex of leading, professional learning, pedagogy, student learning, and research and reflection practices (Kemmis et al. Citation2014) in relation to this temporal transition. Scrutinising the sayings, doings, and relatings data categories, we considered the changing cultural-discursive, material-economic and social-political arrangements of the built spaces in which the educators work and students learn, as articulated by the school leaders. We noted where there were transitions profiled in the data, where leaders spoke about the less valued practices that they wanted to transition out of in their schools. We also looked for the ‘21st century learning practices’ that the leaders aspired to introduce in their schools and gave consideration to how the principals thought that this transition could be made. In this analytical process we looked in the shadows of the transcribed text to seek nuances around the articulated shifts in vision for education.

In a third layer of analysis, we use ‘tables of invention’, initially developed by Kemmis et al. (Citation2014) for analysing practices. These analytic tables provide a heuristic that support the systematic mapping of existing practices in specific parts of the ecology. They are helpful in mapping practices of leading, professional learning, pedagogy, student learning, and reflecting. We developed five ‘tables of invention’ for analysing learning in relation to ecologies of practices () which comprise leading, professional learning, pedagogy, student practices and research and reflection (Kemmis et al. Citation2014) (See leading example in ). As new practices usually, but not always, involve the modification of existing practices, a table of invention can help us to understand how people come to practice differently. These tables were helpful for us in analysing learning as the ‘reproduction with variation’ of the sayings, doings, and relatings of practices to mesh with new or changed arrangements in an ILE. We carefully examined the ‘sayings’, ‘doings’ and ‘relatings’ using the table of invention to analyse how the principals described the intersubjective spaces of leading, professional learning, pedagogy, student learning, and reflecting.

Table 2. Leading practices in the transition to ILE.

Our analytical process allowed us to understand the particular transitional practices that leaders identified were taking place in ILE (how the C21 imaginary can be realised) and what learning is required in relation to the various practices of the Education Complex.

Realising the twenty-first century imaginary in ILE

The future-focused imaginary of twenty-first century learning was implicit in the interviews as the principals spoke about how to achieve the aspirational change. We use samples of interview data to reveal how leaders talked about the different aspects of the Education Complex, how they described the transition between the past and a desired future, and how they envisage the transition will be made. These data reveal forms of pastoral power.

Principals’ perceptions of leading practice in the transition from C20 to C21 Century teaching

There was a stance taken among the leaders to shape the workforce through both building design and their strategic management of teachers’ work. In this way, there would be fewer ‘kings and queens in their castle running things how they like’ (Dana). The principals signalled that they can future proof teaching practice through creating fixed open spaces in schools that prevent teachers from ‘revert[ing] back to a form of single cell teaching’ (Rod). Staffing decisions are based on how well teachers adapt to desired pedagogy. Those who align with the twenty-first century imaginary, as articulated by the principal, are rewarded with ‘high powered positions of significance … ’ (Sam). Teacher control of learning spaces is deliberately decentred so that responsibility can be distributed. It is ‘a hard thing to do for a teacher … who has been in control of their environment’ (Sam). The leaders acknowledge the fatigue experienced by teachers who are engaging in continuous improvement and therefore saw the need to put ‘supports in place to allow staff to make those changes’ … [and how] to support them too’ (Nigel).

Principals’ perceptions of leading professional learning in the transition from C20 to C21 Century learning

The principals make time and space for professional learning in order to create relationships and shape the perspectives of teachers. They foster transitions in teacher identities and relationships and work with teacher mindsets to facilitate teacher collaboration and team teaching. This can ‘help teachers to understand the importance of collaborating to make the biggest difference for learners … [where they engage in] multiple relationships to enhance learning’ (Nigel). With the magnitude of change, leaders manage the challenges around ‘time, space and [opportunities for] strategic planning to enable teachers to make a transition to these spaces’ (Nigel). The focus on ‘de-siloing’ disciplines (especially for the secondary leaders) supports an emphasis on creating spaces for cross-disciplinary talk and relationships. To foster cross-disciplinary collaboration among teachers, leaders ‘mix them up [and] bring them together [and] put them around tables or circles’ (Sam). There were aspirations expressed for sleek systems of continuous improvement and flexibility in resourcing and staffing. However, as Sam points out, ‘it’s like this massive game of chess [and to] increase the outcomes that we actually want the players within it and the resources within it need to be malleable enough to be able to do that.’ Sam’s comment reflects a belief that leaders have the capacity to manipulate teachers as players in a system, yet this depends on teacher mindsets. Moreover, schooling environments can be structured to support a collaboration and common goals, with the flexibility of ILE spaces strategically used to collapse barriers between people. As Sam observes, ‘you do those things that will promote, push together, mould, or direct [teachers] and make it easier for people to collaborate.’

Principals’ perceptions of leading pedagogy in the transition from C20 to C21 Century learning

The transition from 20th to twenty-first century learning can be achieved by creating opportunities for teachers to practice in new ways. The leaders described how they sought to ensure that student participation in classrooms is not tokenistic. They assist teachers to understand classroom dynamics that enable students to be authentic decision makers. Nigel suggested that ‘most teachers don’t understand that their student centred environment is [not one].’ This implies that while teachers may target the needs of the various groups and individuals in their classroom, they may not foster a shift in power relations where students are able to resist or contribute to decisions beyond simplistic and tokenistic conceptions of ‘choice and voice’ (Miliband Citation2006).

Work with teachers involves assisting them to differentiate for various student levels of achievement and providing opportunities for student decision making where there is ‘true personalised learning’ (Sam). Sam notes the affective dimension associated with leading pedagogical shift, pointing out that teachers need opportunities to experience positive close collegial collaboration so that ‘box and corridor’ environments are seen as ‘lonely’ places. Leaders work with staff to develop protocols around use of space and ways of working as ‘the space will define certain activities or challenge certain activities’ (Sam). Working with teachers to be ‘much more collaborative’ it is helpful for leaders to understand the progression of team development, with teachers at ‘various points on their journey with it’ (Dana).

The leaders describe how teachers share responsibility for curriculum areas, where there is team planning and individual responsibilities within the group. There is distributed expertise as teachers learn alongside each other as they are ‘doing team planning’ and take responsibility for programmes across classes (Dana). Leaders understand that pedagogical practice is more time consuming and there is an increased workload. Teachers have to ‘consult with other people and [they] need to come up with a consensus’ [as] the workload increases immeasurably’ (Nigel). When there are problems within teams, leaders need to understand how to trouble shoot. They have ‘to go in and see what [and] why’, so that they can provide support (Dana). Dana also notes that leaders can find ways for teachers to have their space when they need it, so that they do not ‘throw out the baby with the bathwater … [and] still retain the option to sometimes be in [their] own space’ (Dana).

Principals’ perceptions of leading student learning in the transition from C20 to C21 Century learning

The principals articulated a vision for student learning to be fostered through pastoral forms of control. This is where students are positioned as self-managing and self-regulating individuals. Their learning processes and, where possible, content, is personalised and negotiated with them to ensure that they are motivated and the programme addresses their point of need. Mechanisms associated with formative assessment are used to support students’ personal learning goals, address their needs at different levels, and foster engagement with their academic passions. Student sovereignty is valued and prioritised and some students are permitted licence to make decisions around how they use the space. This agency is the domain of some children and not others. Students are carefully supported with their transition into open spaces, as some may not manage the self-regulation required to operate effectively. I could think of a couple of kids that we’ve actually had to put desks in for because the whole choice thing is just a bit overwhelming (Rod).

Leaders note that specific guidance is needed if teachers are to work with students so that they are self-managing in their use of space and understand how they can use spaces for different pedagogical purposes. ‘So initially the teacher actually taught the children very specifically how to move from space to space and put some strategies and guidelines around that’ (Dana). Leaders observed how the use of space is surveilled by teachers and in some instances there is a tiered approach to permission around its use. ‘[Teachers indicated] whether or not they could [move], when was it appropriate to move, when it wasn’t, who needed permission and who didn’t’ (Dana). The leaders articulated a focus on learner agency where learners initiate learning, determine who they work with, and create spaces to work in. However, as Dana indicates, teachers still determine which students can be flexible in decision making and which need to closely follow the guidelines set by the teacher.

Principals’ perceptions of leading teacher reflection in the transition from C20 to C21 Century learning

The leaders observed how the structure of the ILE and the associated reconstituted relationships affords a transition in professional reflection. They described the need to develop a culture where teachers undertake ongoing practice analysis, where they ‘deconstruct and reflect on their practice’ (Nigel) through reflecting on the teaching that occurs in the collaborative spaces. This culture involves risk-taking and openness about professional practice. Nigel described how teachers work within a system that supports them to become self-managing learners in ILE. ‘[There needs to be] an expectation that [teachers] have some pretty open and honest conversations about experiences that happened within [the] space’. There is a move from ‘mulling it over in your head … to come up with your own ideas. … in a traditional classroom’ (Nigel), to deprivatised practice and the associated intensification of professional learning. There are many eyes on the practice with ‘multiple perspectives and a number of people’ (Nigel). The transition involves setting up a parallel with student learning in the ILE. Sam notes that spaces need to be set up so that ‘[teachers are] learner[s] just like the students are learners in this space.’ Reflective practice is structured in the same way student learning is managed, with teachers encouraged to be ‘an effective learner’ through ‘reflecting and thinking and setting goals’. The Principals use ILE spaces to set up the transition for reflective practice seeing that it ‘should aid this notion of social learning and learning with others and connecting and communicating’ (Sam). The structure of socially constituted space is a means of prefiguring new work practices, relationships, and identities, as it ‘shapes it quite directly, if you take walls out’ (Sam).

Now we have set out the Education Complex as described by the principals in their transition toward their aspirational vision for twenty-first century learning, we next consider the practice architectures that ‘hang together’ and hold new practices in place or provide constraints to the transition process.

Coming to practice differently in ILE

The practices which were described by the principals that support transitions to ILE are embedded in assumptions about how school cultures operate (both visibly and invisibly). The principals described themselves as change agents, making unidirectional assumptions that their impact can change teacher mindsets. This is a dominant discourse in schools where leaders are expected to facilitate transformative change in teacher practice through their engagement with teachers (Tuytens and Devos Citation2011).

In , we illustrate how we used tables of invention to illustrate the learnings to be gained through coming to practice differently in the practice ecologies (Education Complex) of ILE. The table exemplifies how we analysed different leading practices and examined the variance between Time 1 (T1) twentieth century learning to Time 2 (T2) and twenty-first century learning. The principals leading this transition from twentieth to twenty-first century learning are changing how they lead through the language they use (sayings), what they do (doings), and how they relate (relatings). The linked practice architecture arrangements are listed down the right side of .

Our findings suggest that leaders’ existing ways of practising (T1) are not in alignment with what is required to address the articulated aspiration for twenty-first century learning in ILE. In response, leaders shift (reproduce with variation) existing ways of practising to come to practise differently (at T2). Although some practices can be seen in single cell classrooms, and translated to ILE, what is required of leaders, teachers and students morphs to create different practice iterations within the ecologies of ILE.

Although we only include ‘Leading practices in the transition to ILE’ here, we used all of the tables of invention to provide commentary on the described ecologies of practice (professional learning, pedagogy, student practices, and reflection). This heuristic enables us to describe how practices are reproduced during this transition period for leaders and teachers as they come to practice differently in the changing practice architectures of ILE.

Coming to lead differently

illustrates the practices of leading and practice architectures associated with the transition to twenty-first century learning in ILE. As principals learn to lead differently in ILE, they indicate that they reframe language around what constitutes professionalism, and invoke a discourse around collaboration and trust that is different to the existing emphasis on teacher individualism with its corresponding emphasis on the autonomous teacher professional (cultural-discursive). Taking action, principals state that they dissuade teachers from solitary single cell teaching practices through implementing policy to deliberately future proof through designing non-traditional spaces in the new buildings (material-economic). Relationships are reconfigured with a focus on student/student, teacher/student, and teacher/teacher collaborations. The principal suggest that they deprivatise practice through the redistribution of responsibility. They reframe the school culture to promote interdependence with a focus on structuring teams of compatible colleagues (social-political).

Coming to undertake professional learning differently

Principals articulated that they learn to lead professional learning by shaping teachers’ understandings that they are not autonomous practitioners and learn together on site in the ILE. This involves managing teacher mindsets about individual practice, reframing the language around professional practice, and emphasising the value of collaboration (cultural-discursive). Through strategic planning and making time for specific learning, principals make space for organisation systems for continuous improvement. Resources and staff are manipulated in the interest of improved outcomes (material-economic). Principals said that they recruit and manage staff differently, so that teachers with pertinent skills can enhance the capability of their colleagues in the ILE. Relationships are legitimated across disciplines through the provision of structures to enable them. Teachers are encouraged to enhance each other’s learning. Spaces are created for new forms of relationships where there is professional learning through ‘de-siloed’ practice. Attitudes are fostered so that colleagues learn from each other (social-political).

Coming to teach differently

Principals articulated that they practice differently through encouraging pedagogy that ensures teachers provide students with opportunities for input in classrooms. This is a student-centred teaching discourse. They work with teachers to build expertise so that they can address student diversity and provide opportunities for student decision making (cultural-discursive). Principals said that they encourage the explicit actions around Assessment for Learning, co-teaching, and intensive use of digital technologies (material-economic). Teachers are supported to rethink power relationship in their practice in order to promote student voice and learner agency. Principals indicated that they foster classroom dynamics that enable students to be decision makers in the classroom. They ensure that student engagement is not tokenistic nor merely about arbitrary teacher-defined choice (social-political).

Coming to learn differently

Principals articulated that they practice differently through supporting teachers to work with children to personalise their learning. They develop a language around the ‘responsibilised’ student. An agency discourse is promoted by the principal, where students have their own personal goals and their unique personal needs are met. Principals said that they encouraged a culture where students have both ownership and accountability for their own learning (cultural-discursive). Students (those sanctioned by the teacher) are able to move freely in the learning spaces to determine which spaces best meet their needs as they learn (material-economic). Students collaborate with peers and work with different teachers in the ILE, instead of just having one teacher exclusively (social-political). We offer a caveat here that although leaders work closely with teachers to foster shifts in teaching to align with the twenty-first century imaginary, their work can only have an indirect influence on changes to practices of student learning.

Coming to reflect differently

Principals articulated that they promote a shift in teacher reflective practices where the use of specific language and terminology is used to frame learners and their learning within the new expectation that teacher collaborate reflectively to develop new ways of talking together. This is a reinvented language of learning (cultural-discursive). Principals said that they encourage a deprivatisation of practice through teacher peer observations, where there is potential for constant collegial surveillance and an expectation of reflective conversations around each other’s practices (material-economic). Principals indicated that they actively encourage teachers to draw from their reflection in their collaborative decision making and incorporate new ideas into the ways they work, both individually and collectively, to grow a collaborative culture of learning (social-political).

Discussion

The practice architectures described by the principals reflect an underlying discourse of reflexive modernity (Beck, Giddens, and Lash Citation1994; Beck, Bonss, and Lau Citation2003), where ‘manufactured uncertainty’ is generated so that technical solutions can be legitimated and called for to ensure ‘progress’ (Scott and Marshall Citation2009, 638). This whitewater of change provides a rationale for new practices and the destabilisation of prior practices. This pressure to embrace change is a key driver in the argument to reshape practices through moving to an ILE model. However, the pace and speed of change expected can be overwhelming, with an expectation that knowledge is revised on an ongoing basis. Giddens (Citation1991, 37) observed that when chaos threatens, people experience a sense of ‘dread’ where ‘prospects of being overwhelmed by anxieties … reach to the very roots of our coherent sense of being in the world’.

The prefigurings of practice architectures may be a comfortable fit when teacher identities and practices align with aspirational twenty-first century practices. However, they may cause deep discomfort, particularly when individuals’ sayings, doings, and relatings clash with site based cultural-discursive, material-economic and social-political arrangements in ILE. We see this when teachers who have a preference for single cell teaching, are individualistic in their thinking, see themselves as autonomous practitioners, and find themselves in changed arrangements where there are open plan settings. Their views are not aligned with the professional learning in their school, the suite of new expected pedagogical practices, nor the changed power relationships between teachers, and between teachers and students. The move to ILE contributes to changing patterns of educators’ work and we have identified a range of contradictions for workplace learning.

Contradiction 1: destabilisation and ontological security

It is a contradiction that leaders support the destabilisation of some teaching practices while fostering a sense of cohesion and stability for teachers to work effectively. Leaders carefully strategise ‘set ups’ in ILE so that ecologies of practices ‘hang together’ (Kemmis et al. Citation2014, 31). For instance, in prompting teachers to embrace change, which can be confusing, uncomfortable, or even ‘dread’-ful, leaders deliberately decentre individual teacher control of learning spaces, through the redesign of buildings. Destabilising practices include ‘de-siloing’ the curriculum, redesigning teaching and meeting spaces, and physically collapsing discipline spaces into each other (secondary settings). Through destabilising teacher control, leaders can catalyse teacher collaboration and distributed responsibility. The discourse of manufactured uncertainly is mobilised to support this destabilisation.

When leaders build a case for change (Kotter Citation2012), teachers see ILE as a solution for a problem that is shaped through a narrative of meeting the unknown requirements of the twenty-first century future (which ironically is already well upon us). However, there is a paradox here in that there is also an expectation that teachers are self-managing and are able to exercise some degree of control over their teaching spaces, the direction of their teaching practices, and professional learning. For this reason, there is a need for leaders leading pedagogical transitions to also foster an ontological security, which is a way of being that is premised on trust and predictability (Kenway and Bullen Citation2000). There is a sense that although a storm may be ranging at a metalevel, the cohesion around a vision for twenty-first century learning at school level provides safe harbour. For this reason, leaders leading pedagogical transitions can use the discourse of manufactured uncertainty to prompt a rationale and an impetus for change, while also fostering an ontological security in school level interpersonal relationships (Kenway and Bullen Citation2000).

Contradiction 2: teacher wellbeing and expendability

Contradiction occurs within the notion of care and the opportunity for growth and enhancement for those aligned with the goals of the institution. In order to cope with manufactured uncertainty, leaders work with teachers to develop ‘change mindsets.’ This is a mindset which allows leaders and teachers to work responsively with the expectation that they address the impetus for ongoing change, as demanded by twenty-first century schooling discourse (Charteris, Smardon, and Nelson Citation2016, 43). Teachers who can manage uncertainty and work closely with others are sought after to staff ILE and in schools where there are refurbishments these teachers are provided with opportunities to advance quickly in their careers. It is an irony that although wellbeing and pastoral care is a feature of Aotearoa New Zealand schools, teachers can be expendable when they do not have a change mindset and/or future focused practices that are aligned with the ones valued in their schools. Teachers can be silenced if their perspective contradicts the leader’s ‘vision’ (Courtney and Gunter Citation2015).

Contradiction 3: self-management and the ‘Velvet Cage’

There is a contradiction between the focus on agency and self-management, and the collective goals of institutions. The ecologies of practices that cohere to support twenty-first century learning in ILE can be seen as a velvet cage (Schutz Citation2004), in that leading, professional learning, teaching, student learning, and reflecting practices are premised on all stakeholders accepting, trusting and committing to the goals and values of the organisational system. There is an emphasis on eliminating ‘manifestations of power’ that can be contested (e.g. though facilitating teacher agency, student agency and distributed leadership to align with the goals of the organisation) in order to ‘co-opt the creativity of participants by recruiting their desires and motivations’ (Schutz Citation2004, 17). At a macro level, the data in this study illustrate a vision of a ‘perfectly self-managing society’, where leaders, teachers, and students enact subjectivities immersed in ‘pastoral’ forms of control. In ILE pastoral forms of control replace the emphasis on ordered discipline, as teachers and students are seen as self-managing. This disposition is scaffolded through the physicality of ILE spaces, where students demonstrate agency as decision makers in the spaces and teachers work with students and between themselves as colleagues to promote self-regulating and self-managing learners (Charteris and Smardon Citation2018b).

Contradiction 4: individual agency and collaboration

It is a contradiction that leaders exert influence on teachers to be both accountable as individuals and also function in collaborative teams. Teachers are sovereign agents, often individually held accountable for practice through the use of student achievement data and professional learning processes (e.g. classroom observations or student voice data). Yet, in ILE they work closely with others through co-planning, co-teaching, deprivatising practice, continuously engaging in professional learning, and negotiating the use of space on an ongoing basis. The way that students and teachers are required to take responsibility and ownership for their own teaching and learning practices in ILE reflects an aspiration for a ‘perfectly self-managing society’. Teachers are expected to work together in their decision making to enact teacher agency in executing the goals of the organisation. Yet they have to give away some degree of individual agency and sovereignty to work in ILE.

The shifts to ILE both significantly change patterns of educators’ work and reshape the identities of teachers who, in accordance with market logic, are ‘perfectly self-managing.’ We concur with Couch (Citation2018) who notes that progressive discourse has been adopted for neoliberal purposes in ILE. He observes that ‘the meaning behind terms such as “learner-centred”, “self-managing” and “innovative” are all being continuously redrawn and repurposed’ (30) and ‘a critical exploration … exposes a deeper undercurrent of instrumentalism at play which dramatically reorients the term [progressivism] from its humanist foundations towards a neoliberal philosophical anchor’ (131).

Conclusion

The interrelated arrangements of practice architectures are so naturalised in our day to day existence that they are often invisible. Moreover the structural arrangements that create site ontologies in workplaces prefigure ways of being and practicing (Kemmis and Grootenboer Citation2008). Leading practices are an important part of practice architectures, where there is a project to transition other practices associated with the Education Complex in ILE. Leaders play ‘a significant role in orchestrating the preconditions that enable and constrain transformations to teaching and learning practices within schools’ (Wilkinson and Kemmis Citation2015, 349). Put simply, leading is both a practice and conduit for the other practices in the Education Complex.

In this article we have explored contradictions associated with leaders work to transition practices to a vision for twenty-first century learning in ILE. This vision is embedded in discourses of manufactured uncertainty, progressivism, and neoliberalism. A manufactured sense of fear and anxiety about failure is routinely used to leverage education reform (Sullivan Citation2018) and this can influence the work of school leaders and teachers. Leader practices are influenced by technologies of leading (sayings, doings, and relatings) that enable them to work on the practice set ups. In our analysis, we observed how management technologies were deployed by leaders to ensure continuous improvement of teacher practice, the reshaping of student learning in ILE, and a shift in practice traditions. In providing this critique of twenty-first century learning in ILE we do not advocate that the factory model of schooling has more integrity, because the power structures are explicit to all participants, nor that the industrial ‘egg crates’ Lortie’s (Citation1975) of single cell classrooms necessarily means that teachers are professionally isolated. In this article our focus is on critiquing naïve notions of progress through giving account of the practices that we recognised in the data and analysing them in terms of neoliberal discourse.

Through moulding the social and material affordances of ILE spaces, leaders prefigure new work practices, relationships, and conceptions of themselves as leaders, and teacher and student identities. This work, in accordance with practice theory is undertaken in contexts where practice architectures are established on site ontologies. Therefore practices are both open-ended and stable, and are not commensurate with an entitative ontology of understanding leadership. Although we have focused on leaders and leading practices, we acknowledge that we only have four leader perspectives of the various ILE sites, and this is a limitation in the study. The findings are based on principal perspectives and assumptions of practice, not on teacher and student experiences of practices. There is scope for further research that triangulates perspectives of leaders with those of teachers, students, and communities.

The practice landscape described in this article suggests a vision for a perfectly self-managing society or ‘velvet cage’ (Schutz Citation2004), where learners and teachers engage in new forms of pastoral control that comply with market logic. In ILE, past progressive constructions of pedagogy become new again where there is a new practice tradition. ‘New’ ideals are framed by the aforementioned discourses (material- discursive arrangements) that conjure up conceptions of teacher professionalism and the positioning of students as active agents. Thus the new pedagogical imaginary and associated conception of professionalism reveal a hegemony of collegial surveilling, self-managing arrangements, and a reinvented language of learning. This imaginary, while echoing progressive views, appropriates and is compromised by neoliberal discourses, work activities, and social-political imperatives. Thus these neo-progressive aspirations for education in ILE shape leaders, teachers, and students to be self-managers par excellence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Beck, Ulrich, Wolfgang Bonss, and Christoph Lau. 2003. “The Theory of Reflexive Modernization: Problematic, Hypotheses and Research Programme.” Theory, Culture & Society 20 (2): 1–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276403020002001.

- Beck, Ulrich, Anthony Giddens, and Scott Lash. 1994. “Preface.” In Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order, edited by Ulrich Beck, Anthony Giddens, and Scott Lash, vi–viii. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Benade, Leon. 2017. Being a Teacher in the 21st Century. Singapore: Springer.

- Blackmore, Jill, Debra Bateman, Anne Cloonan, M. Dixon, J. Loughlin, Joanne O’Mara, and Kim Senior. 2011. Innovative Learning Environments Research Study. Melbourne, Victoria: Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

- Charteris, Jennifer, and Dianne Smardon. 2018a. “‘Professional Learning on Steroids’: Implications for Teacher Learning Through Spatialised Practice in New Generation Learning Environments.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 43 (12). Accessed July 25, 2020. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ajte/vol43/iss12/2.

- Charteris, Jennifer, and Dianne Smardon. 2018b. “A Typology of Agency in New Generation Learning Environments: Emerging Relational, Ecological and New Material Considerations.” Pedagogy, Culture and Society 26 (1): 51–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2017.1345975.

- Charteris, Jennifer, Dianne Smardon, and Emily Nelson. 2016. “Innovative Learning Environments and Discourses of Leadership: Is Physical Change Out of Step with Pedagogical Development?” Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice 31 (1/2): 33–47.

- Charteris, Jennifer, Dianne Smardon, and Emily Nelson. 2017. “Innovative Learning Environments and New Materialism: A Conjunctural Analysis of Pedagogic Spaces.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 49 (8): 808–821. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2017.1298035.

- Connolly, Mark, and Joe Hughes-Stanton. 2020. “The Professional Role and Identity of Teachers in the Private and State Education Sectors.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2020.1764333.

- Couch, Daniel. 2018. “From Progressivism to Instrumentalism: Innovative Learning Environments According to New Zealand’s Ministry of Education.” In Transforming Education: Design, Technology, Government, edited by Leon Benade, and Mark Jackson, 121–133. Singapore: Springer.

- Courtney, S. J., and H. M. Gunter. 2015. “‘Get Off My Bus!’ School Leaders, Vision Work and the Elimination of Teachers.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 18 (4): 395–417. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2014.992476.

- Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin Books.

- Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- House of Commons: Education and Skills Select Committee. 2007. Sustainable Schools: Are We Building Schools for the Future? Seventh Report of Session 2006–07. London: Stationery Office.

- Kalantzis, Mary, and Bill Cope. 2012. “Histories of Pedagogy, Cultures of Schooling.” In The Powers of Literacy (RLE Edu I): A Genre Approach to Teaching Writing, edited by Bill Cope, and Mary Kalantzis, 38–62. London: Routledge.

- Kemmis, Stephen, and Peter Grootenboer. 2008. “Situating Praxis in Practice: Practice Architectures and the Cultural, Social and Material Conditions for Practice.” In Enabling Praxis: Challenges for Education, edited by Stephen Kemmis, and Tracey Smith, 37–62. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Kemmis, Stephen, Jane Wilkinson, Christine Edwards-Groves, Ian Hardy, Peter Grootenboer, and Laurette Bristol. 2014. Changing Practices, Changing Education. Singapore: Springer.

- Kenway, Jane, and Elizabeth Bullen. 2000. “Education in the Age of Uncertainty: An Eagle's Eye-View.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 30 (3): 265–273. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/713657463.

- Kotter, John. 2012. Leading Change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review.

- Lingard, Bob, and Sam Sellar. 2012. “A Policy Sociology Reflection on School Reform in England: From the ‘Third Way’ to the ‘Big Society’.” Journal of Educational Administration and History 44 (1): 43–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2011.634498.

- Lortie, D. 1975. Schoolteacher: A Sociological Inquiry. New York: John Wiley.

- Mahon, Kathleen, Stephen Kemmis, Susanne Francisco, and Annemaree Lloyd. 2017. “Introduction: Practice Theory and the Theory of Practice Architectures.” In Exploring Education and Professional Practice, edited by Kathleen Mahon, Susanne Francisco, and Stephen Kemmis, 1–30. Singapore: Springer.

- Mahony, Pat, Ian Hextall, and Malcolm Richardson. 2011. “‘Building Schools for the Future’: Reflections on a New Social Architecture.” Journal of Education Policy 26 (3): 341–360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2010.513741.

- Mehta, Rohit, Edwin Creely, and Danah Henriksen. 2020. “A Profitable Education: Countering Neoliberalism in 21st Century Skills Discourses.” In Handbook of Research on Literacy and Digital Technology Integration in Teacher Education, edited by Jared Keengwe, and Grace Onchwari, 359–381. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Miliband, D. 2006. “Choice and Voice in Personalised Learning.” In Schooling for Tomorrow: Personalising Education, edited by OECD, 21–30. Paris: OECD. https://www.oecd.org/site/schoolingfortomorrowknowledgebase/ … /41175554.pdf.

- Ministry of Education. 2011. “The New Zealand School Property Strategy 2011–2021.” Accessed July 20, 2020. http://www.minedu.govt.nz/NZEducation/EducationPolicies/Schools/SchoolOperations/~/media/MinEdu/Files/EducationSectors/PrimarySecondary/PropertyToolbox/StateSchools/SchoolPropertyStrategy201121.pdf.

- Ministry of Education. 2015. “Designing Schools in New Zealand. Requirements and Guidelines.” Accessed July 20, 2020. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/the-oecd-handbook-for-innovative-learning-environments/the-principles-of-learning-to-design-learning-environments_9789264277274-5-en.

- Ministry of Education. 2020. “Education Infrastructure Design Guidance Documents.” Accessed July 20, 2020. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/the-oecd-handbook-for-innovative-learning-environments/the-principles-of-learning-to-design-learning-environments_9789264277274-5-en.

- Mishra, Punya, and Rohit Mehta. 2017. “What We Educators Get Wrong About 21st-Century Learning: Results of a Survey.” Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education 33 (1): 6–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2016.1242392.

- Mutch, Carol. 2013. “Progressive Education in New Zealand: a Revered Past, a Contested Present and an Uncertain Future.” International Journal of Progressive Education 9 (2): 98–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2013. “Innovative Learning Environments.” Accessed July 25, 2020. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/the-oecd-handbook-for-innovative-learning-environments/the-principles-of-learning-to-design-learning-environments_9789264277274-5-en.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2015. “Schooling Redesigned: Towards Innovative Learning Systems.” Accessed 25 July 2020. https://www.oecd.org/education/schooling-redesigned-9789264245914-en.htm.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2017. “The OECD Handbook for Innovative Learning Environments.” Accessed July 25, 2020. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/the-oecd-handbook-for-innovative-learning-environments/the-principles-of-learning-to-design-learning-environments_9789264277274-5-en.

- Raelin, Joseph. 2016. “Imagine There are No Leaders: Reframing Leadership as Collaborative Agency.” Leadership 12 (2): 131–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715014558076.

- Rasborg, Klaus. 2012. “‘(World) Risk Society’ or ‘New Rationalities of Risk’? A Critical Discussion of Ulrich Beck’s Theory of Reflexive Modernity.” Thesis Eleven 108 (1): 3–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513611421479.

- Schutz, Aaron. 2004. “Rethinking Domination and Resistance: Challenging Postmodernism.” Educational Researcher 33 (1): 15–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033001015.

- Scott, John, and Gordon Marshall. 2009. A Dictionary of Sociology. 4th Revised Ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sullivan, Teresa L. 2018. The Educationalization of Student Emotional and Behavioral Health: Alternative Truth. Cham: Springer.

- Tse, Hau Ming, Susannah Learoyd-Smith, Andrew Stables, and Harry Daniels. 2015. “Continuity and Conflict in School Design: A Case Study from Building Schools for the Future.” Intelligent Buildings International 7 (2-3): 64–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17508975.2014.927349.

- Tuytens, Melissa, and Geert Devos. 2011. “Stimulating Professional Learning Through Teacher Evaluation: An Impossible Task for the School Leader?” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (5): 891–899. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.02.004.

- Wilkinson, Jane, and Stephen Kemmis. 2015. “Practice Theory: Viewing Leadership as Leading.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 47 (4): 342–358. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2014.976928.

- Wood, Adam. 2019. “Built Policy: School-Building and Architecture as Policy Instrument.” Journal of Education Policy, 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1578901.

- Wylie, Cathy, Sue McDowall, Hilary Ferral, Rachel Felgate, and Heleen Visser. 2018. Teaching Practices, School Practices, and Principal Leadership: The First National Picture. Wellington: NZCER.

- Yin, Robert K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 4th Ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.