ABSTRACT

Soft skills have been increasingly recognised as important in the workplace. They have been incorporated, moreover, in education and training curricula internationally. However, their conceptualisation lacks in theoretical grounding. This study fills this gap by taking a skills-utilisation approach (rather than a skills-requirements approach) and studying communication skills in the Human Resource function of two organisations, Flow and Energy. Key informants were participants in the events that were theoretically sampled (e.g. employees, candidates). Observations of interactions between HR professionals and their interlocutors, combined with conversations, interviews and organisational documents provided the data corpus. The analysis combined the key mechanics of grounded theory and discourse analysis. The conceptual framework drew on situated learning. Results indicate that communication skills should not be seen as decontextualised communication behaviours. Instead, communication skills require constant manoeuvring and alignment of communication behaviour (what people do) with the following three factors: the aim of the communication encounter, the actors’ positional identities and the various forms of knowing they bring to the practice. This view unveils the tentative and elusive (rather than transferrable and universally applicable) nature of communication skills. Such an evidence-driven conceptualisation has implications for how soft skills should be researched, understood and developed/accredited.

Introduction

Increasing skills supply among students, apprentices and incumbents have formed a significant priority internationally for policymakers, educational stakeholders, and organisations (Burke et al. Citation2020; LINCS Citation2020; OECD Citation2016; WEF Citation2015); in higher education and more recently in continuing professional education (Andrews and Higson Citation2008; Anthony and Garner Citation2016; Fixsen, Cranfield, and Ridge Citation2018; Succi and Canovi Citation2020; Tseng, Yi, and Yeh Citation2019). The primacy of skills, as a key determinant of economic growth and economic redistribution, could be attributed, at least in part, to the assumption of a strong linear correlation between increased skills supply and productivity of individuals and organisations, leading to economic wealth creation and growth (indicatively Madsen and Murtin Citation2017; Mori and Stroud Citation2021; Wolf Citation2009). The primacy of skills is, furthermore, reflected in the continuous preoccupation with the identification of skills essential for an individual’ s employability and subsequent success in the labour market (indicatively Constable and Touloumakos Citation2009; Cacciolatti, Lee, and Molinero Citation2017; Hurrell, Scholarios, and Thompson Citation2013; Finch et al. Citation2013; Remedios Citation2012; Succi and Canovi Citation2020).

The mainstream approach towards identifying skills important for work can be found in the literature spanning from education, training, and workplace learning, career development, policymaking, human resource, economics, labour market to management but also to medicine and engineering (see also Touloumakos Citation2020). This approach in identifying skills important for work is a de-contextualised skills-requirements approach, whereby jobs are broken down to tasks that then are broken down to behaviours called skills and lists of different sets of skills get constantly updated to incorporate ‘new’ skills (Nickson et al. Citation2012). Emphasis is clearly on skills that are non-technical and are believed to be necessary for all jobs – often referred to as employability or soft skills (Handel Citation2012). Taxonomies presenting different sets of such skills emerge through the typical employers’ surveys or other research with employers –for example, the National Employers Skills Surveys (Constable and Touloumakos Citation2009; Winterbotham et al. Citation2020), bodies looking to accredit soft skills such as the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, and policy documents (indicatively the OECD (Martin Citation2018) document on ‘Skills for the 21st Century’, or the US Department of Labour document on ‘Soft Skills that pay the bills’). Rarely taxonomies in such documents are evidence-based. Typical skills categories included in the soft skills literature encompass communication skills, teamwork, problem-solving and more (Touloumakos Citation2020). Communication skills, the focus of this study, are reported typically as lists of behaviours learnt in a classroom, acquired by students (also in Anju Citation2009; Attewell Citation1990; Touloumakos Citation2011; Jain and Anjuman Citation2013; Matteson, Anderson, and Boyden Citation2016) and transferred and applied from classroom to practice but also from one workplace to another, or from one work episode to another.

This conceptualisation of communication skills (and soft skills in general) is important because it impacts directly on the design and implementation of policies, programmes, and curricula for soft skills development in higher and continuing education and in organisations. Following this mainstream individualistic view learning communication behaviours – that corresponds typically to a transmission model of education (Saavedra and Opfer Citation2012) is seen, as the single most important factor in becoming a skilful communicator. After three decades of educational policiesFootnote1 following this premise and with the aim to inject soft skills in the labour market what has the outcome been? Skills gaps and shortages persist alongside the gradually increasing numbers of people completing qualifications and graduate or professional development programmes and in progressively higher levels (see for skills gaps and shortages Cappelli Citation2015; Cunningham and Villaseñor Citation2014; Hurrell Citation2016; for numbers of people with skills training Capsada-Munsech Citation2017; Sutherland Citation2012).

Against this background, arguably, one should take a step back from a cognitive/individualistic view of learning and skills and more towards a situated or developmental view (see Konkola et al. Citation2007). In this paper the focus is on communication skills specifically (as an example of soft skills) employing a situated perspective. Accordingly, it is proposed that communication skills can be best understood through a skills-utilisation approach (rather than a skills-requirements approach) that allows studying them in practice, where they accrue their value and meaning.

It is posited here that studying what counts as skills in communication practice and what determines skill in information-rich environments can advance our understanding about communication skills and the best approach to develop and accredit them – an approach different to what has been employed so far (Touloumakos Citation2011). With the aim to understand communication skills in practice two research questions were devised:

What counts as communication skills as human resource (HR) professionals engage in their practice?

What are the characteristics of communication skills in use, which can inform curriculum development?

Methodology

This work draws on data generated and analysis conducted for the purposes of a doctoral research in a UK University, in two large organisations (over 10000 employees each). The stance taken in this study towards understanding communication skills was explorative using an in-depth qualitative approach, involving spending extended times within the organisations and using flexibly individual and combinations of qualitative methods (observations, interviews, etc.) to ensure richness and detail of data generated. The openness and flexibility such an approach offers, however, was not meant to be at the expense of research rigour.

Sampling

Human resource was thought to provide a rich and, therefore, instrumental environment in which to study and understand communication skills. In Stake’s (Citation2000) terms, an instrumental case is a study of a case (person, department etc.) that is deemed instrumental in gaining an insight into a particular issue and building theory. The HR environment, in this study, was thought to provide this instrumental space (Stake refers to it as an instrumental case) to enable insights and building theory around what counts as communication skills and what are their characteristics. Accordingly, the HR functions of two organisations, Flow and Energy, had been purposefully selected (Patton Citation2002) ensuring the variation of HR practices sought (see ). The two organisations did business in different sectors, had internal, active, well-organised, and very diverse (between them) human resource functions.

Table 1. Events/Activities observed and key informants’ information.

Accessing Flow and Energy was the outcome of a 10-month process where numerous email-invitations were sent, and meetings were held with different ‘gatekeepers’ (Andoh-Arthur Citation2019) such as the head of HR or the head of the apprentices’ programme in different organisations. Gatekeepers were drawn primarily from the list of collaborators of the research centre in which this study was conducted. Understandably, gatekeepers’ reactions to having an outsider observer in their workplace ranged in most cases from hesitant to negative. Flow and Energy were willing to participate and allow observations for long periods of time and interviewing – conversing with the key informants during these times.

Discussions with the head of HR function in each organisation lead to the selection of events/activities to be observed (for example, assessment centres, training modules, etc.) following the premises of theoretical sampling (Eisenhardt and Graebner Citation2007). Multiple short meetings with the head of HR in each organisation at different points in time during data generation allowed sampling the events/activities that best served the research needs at the time; it also allowed recalibrating the research approach to ensure that work in both organisations went uninterrupted. Key informants in each organisation were the people who participated in the selected events/activities and included the gatekeepers, HR managers, trainers, candidates for the graduate programmes, apprentices, employees or other (see for more details).

Data generation

Methods of data generation were used in combination and independently in response to fieldwork needs. ObservationsFootnote2 were primarily used and thought to give access to knowledge HR practitioners hold about communication skills and which was reflected in their work (in this paper I focus on such observations). Interviews revealed crucial personal and contextual background information (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007). Conversational interviewing (Given Citation2008) proved a valuable method in clarifying issues about preceding or imminent observations. Documents used in different events such as meetings or training sessions, alongside interviews and conversations prior or after the observations provided context and useful information about how work was organised. Data were recorded through extensive and detailed field notes and accounts during or following the observations.

Ethics

The project was reviewed and did receive full ethical approval (Ref. No: SSD/CUREC1/08-066). Matters of confidentiality and anonymity were discussed and decided on an individual basis with each organisation. British Educational Research Association codes of ethical research (BERA Citation2004) served as a platform in making all decisions.

Analysis

Conceptual framework

Employing a constructivist approach, this study sought to identify communication skills in use and understand their characteristics. Situated learning theory (SLT) offered a valuable conceptual framework for this investigation, because it shifts the focus of learning, thinking, and acting from the individual mental level to the relational level – stressing the role of the community, participation, and working together (Anderson, Reder, and Simon Citation1996; Stein Citation1998). Accordingly, this approach allows to consider expertise and knowledgeable skill not as a matter of personal capability but as a matter of transformation through membership in a community of practice (Lave Citation1991; Lave and Wenger Citation1991). This view highlights the social aspects of competence. In this study, this framework is used to capture what and how communication skills are enacted in the context of HR practice that involves specific routines, norms, tools, rules and criteria for skill and expertise. Factors that can help identify and characterise communication skills are thought to lie in the interactions and transactions among agents and agents and the context.

Analytic methods

Data generated were treated as an integrated whole (Cunningham Citation2004), and analysis balanced between ‘what the data were telling me’ and ‘what was it that I wanted to know’ (Srivastava and Hopwood Citation2009, 78). This approach was inductive (Patton Citation2002; Znaniechi Citation1934). An iterative process took place, between immersing with/analysing the data and subsequent engagement and use of the theoretical concepts. Theory helped focusing on how to make meaning of the data and backed up most of the codes and definitions under development (Touloumakos Citation2011).The approach followed in the analysis integrated line-by-line coding and the basic steps of the constant comparative method (Glaser Citation1965; Glaser and Strauss Citation1967) with discourse analysis (Fairhurst and Putnam Citation2019). Steps taken were as follows:

Categories were generated (for example, actions or arguments) through comparing chunks of the data – the emphasis was on what was done by HR professionals’ sayings and what these doings were doing (Gherardi Citation2010);

Properties and characteristics of categories were developed and delineated (a set of rules was devised and guided this process); and

Categories were linked to explore plausible answers to the research questions.

Quality, authenticity, and credibility

The data-derived understanding of communication skills in practice in a quality, authentic and credible manner sought required in turn ‘closeness to’ and ‘participating in the social reality’ (Hammersley Citation1995, p.195) of the HR functions. Closeness was pursued through participating in various activities in multiple roles and for long periods in Flow and Energy (8 and 10 months, respectively). These activities were social dinners, informal HR meetings, or off the record conversations about the introduction and implementation of new policies. Quality was ensured, furthermore, using multiple methods of data generation that enabled ‘triangulation’ (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007) of both the data generated and the themes emerging through the first stages of this analysis. Finally, seeking and obtaining substantial agreement between two different coders assigning codes to a section of the data corpus (following McHugh Citation2012) was thought to add to the credibility and quality sought.

Analytic process

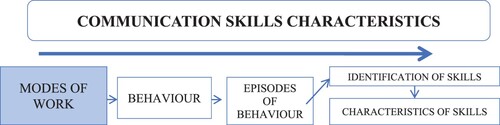

Analysis for this project was conducted along two interdependent levels: one focusing on developing an account of HR practice that featured communication skills; and a second one focusing on identifying and understanding the characteristics of communication skills as used by HR professionals in practice. The analysis at the second level becomes the focus of this paper. The two dimensions were interdependent: the completion of the analysis of HR practice (analysis at the first level) was required for the analysis of communication skills and their characteristics (analysis at the second level) to take place. The analysis at the first level finished with the identification of ‘modes of work’ (see ) in HR practice, with ‘face-to-face communication’ being recognised as ubiquitous. In line with this, communication is seen as part of and therefore, as embedded in HR practice.

The starting point of the analysis at the second level was, therefore, communication between HR practitioners and interlocutors (communication in HR practice) and led to the organisation of ‘episodes of behaviour’ defined in terms of the aims HR professionals sought to achieve in their interactions. Moreover, through this analysis emerged the main category code, namely, ‘behaviour’(/what people do)Footnote3. Finally, through this analysis emerged the key factors determining what counts as communication skill in practice and helping understand communication skills’ characteristics (two final steps in ).

Results

Code key

The analysis produced, in the end, the categories presented in the Code Key summarised in below (of note that the list of behaviours/what people do unpicked from context are indicative and not exhaustive). Code key categories, examples from the data, and theoretical concepts are combined and presented next, to address the two research questions.

Table 2. Code key: identification/characterization of communication skills.

RQ1. What counts as communication skill as HR professionals engage in their practice?

HR practitioners during their communications engage in behaviours (verbal and non-verbal) that fit under the five broad and general terms: ‘exchanging utterances’, ‘questioning’, ‘gesturing’ ‘grimacing’ and ‘listening’ (see . Column on Behaviours/What people do). However, focusing on the specific behaviours (what people do) presented in (e.g. explaining, elaborating, confronting, validating, reiterating) and calling them communication skills arbitrarily is meaningless, as evidence from this analysis suggests. Instead, understanding communication skill lies with understanding communication behaviour (what people’s sayings do) as situated action; therefore action that is emergent, aligns with practice aims, enables HR professionals’ positional identities, and is informed by the different forms of knowing available to them – whether context dependent or not. Each of these factors identifying communication skills are elaborated and supported with data examples next. For each factor, the presentation starts with some context and a brief description of the illustrative example of the excerpt that comes next. A summary of the analytic categories illustrated in the example presented and a conclusive comment follows the excerpt.

‘Aims’

The aims pursued through the various communication episodes emerged as having a key role in identifying communication skills. During the first day of the assessment centre for the apprentices’ program in Energy, Lucia the recruitment consultant leads the group exercise session. Before the candidates enter the room Lucia briefs assessors on the rules and procedures for this session as defined by the company recruitment protocols. Lucia first welcomes assessors participating in the selection of the new apprentices in lines 1–2, and then engages in explaining to them how the groups are separated (lines 2–3), and then she organises work, and delegates (line 3). Much of what she does involves giving directions, such as in lines 4–6 (instructing the assessors to first make notes and then complete the assessment forms) and questioning/seeking validation and feedback from assessors that they are clear about her instructions.

Example 1:

(1) Lucia: Hello all, thank you again for being here helping Energy in selecting the new

(2) group of apprentices. As you can see in your forms for this exercise candidates are

(3) separated into two groups of six candidates. You are responsible for two of them; in

(4) your files [pointing at the file] you can find the candidates’ names. Please make sure (5) that you first observe them and then make notes. Once you have done this, then please (6) fill in the assessment form. Is that clear? [She pauses and looks around. When no one

(7) responds she carries on:]. […]

Summary and conclusion:

Aim of episode of behaviour: managing work (by informing the assessors/candidates on procedures, rules, use of tools, etc, in an Assessment Centre).

Behaviours identified: welcoming, explaining, organising, delegating, giving instructions, seeking validation.

Although this is not the unique repertoire of behaviours that one could mobilise with the aim of managing work, all the behaviours mobilised here are oriented towards serving the purpose of managing work. In line with the proposed conceptualisation in this work, this alinement is one key factor in identifying communication skill in this context. One could potentially find a different set of behaviours (what people’s sayings do) that could be identified as communication skills in a different episode, even with the same aim.

‘Positional Identities’

The role of positional identity (Holland et al. Citation1998, p. 26), the relational aspect of agency ‘that makes claims about who we are relative to one another and the nature of our relationships’, emerged as a key factor in identifying communication skills. In the example that follows both the aims, and positional identities are unpicked to argue their determining role in recognising skill; emphasis is placed on positional identity. This second example comes from a meeting held in the headquarters of Energy between Jason, one of the apprentice programmes team leaders and advisors, and Matt, an apprentice. This is a progress review meeting held regularly between team-leaders/advisors and apprentices. Jason believes that team-leaders/advisors ought (FN, 23.02):

to provide them [the apprentices] with some stability and a sense of belonging. And we found having these regular meetings [progress review meetings] can help accomplish that. They come to us and seek our advice, they expect we will help them, we will discuss their progress, their concerns about their progress, their plans, what potentials there are here in Energy for them. We can’t let them down; it is our role and duty as team leaders to provide this.

For Jason updating/supporting people’s learning and not letting his apprentices down as a (career counsellor/)advisor is enacted through: factual questioning regarding, for example, what particular training section Matt is currently at (line 2), the section coming up (line 4) and the plan for the following step (line 9); advising/guiding Matt to allow enough time to the people who will allocate him in a work group; clarifying issues that seem to be misunderstood by Matt (line 11).

Example 2:

(1) ((After warmly greeting each other …))

(2) Jason: Which section are you at right now? ((He smiles.))

(3) Matt: ‘Milling’

(4) Jason: And where are you going next?

(5) Matt: ‘Fitting’ but I don’t know how and when (.),as there is a hu::ge waiting list I hear.

(6) Jason: Right. Okay. Before you work to the workshop let people know that you are

(7) heading there, yes? >They need to know so that they can assign you to a group.<

(8) Matt: Yep, I am aware, I will talk to a leader next week.

(9) Jason: Which skills have you got to do?

(10) Matt: All of them and 11 weeks of fitting.

(11) Jason: Fitting is a 5-week deal.

(12) …

Summary and conclusion:

Aim of episode of behaviour: engaging & supporting people.

Positional Identity of the actor: advisor/career consultant.

Behaviours identified: factual questioning, advising/guiding, clarifying.

In line with the argument put forward so far, behaviours (what people do) aligning with the aim of the episode and the actor’s positional identity are construed as communication skills in this instance. Arguably, selecting a different repertoire of behaviours such as commanding/directing, or pausing and gesturing intensely (picking a fight) would not have enabled an advisor positional identity or the aim to engage support people’s learning, as these specific behaviours (/what people did) did.

‘Forms of knowing’

Understanding behaviour and recognising skill cannot be done unless considering them as the practical achievements shaped by different forms of knowing (see in Example 3) such as relational knowing (Edwards Citation2010). The example presented next features parts of a ‘selection interview’ held on the second day of the graduate assessment centre in Flow. Two assessors (A1 and A2) participate in the interview with the candidate (C1). At one point during the interview the discussion focused on the candidate’s previous work experience. Early in this interview, the candidate, most probably unintentionally, (line 2) states that one thing that he finds challenging is managing people. While for a moment, A1 moves on to a new issue (line 4), he comes back to it in lines 6–7 by rephrasing C1’s point and probing. And he persists further, as shown next: by rephrasing/reiteration (lines 26–27), probing (lines 27, 31) and pursuing elaboration/justification (lines 20, 23–24, 27), combined with factual questioning (lines 34–35).

Example 3:

(1) …

(2) C1: I found challenging to have to manage people.

(3) A2: Right …

(4) A1: How did you find about Lean?

(5) C1: I heard and learned initially about it in company X.

(6) A1: You said before that you found challenging managing people. Can you talk

(7) a bit more about this? WHAT WAS THE CHALLENGE? ((He seemed really intrigued

(8) indeed to pursue this further.))

…

(19) ((Assessors look at each other briefly. They seem sceptical.))

(20) A1: Can you give us an example of having a problem with someone you worked

(21) with and how you dealt with it?

(22) … ((after a couple of other questions))

(23) A2: How would you describe your relationship with the people you were working

(24) with? ((Back to this again …))

(25) C1: Typical, good.

(26) A1: You mentioned that in a couple of cases where you had problems with

(27) colleagues you went back to either your or their manager. WHY? ((… and again. They

(28) persist, there seems to be something they are not happy about(?) or …))

…

(34) A2: You have worked in and led teams in the past (0.2) do you prefer working in

(35) teams or individually? ((They are for the third time on the matter of how he works

(36) alone and with others …))

Summary and conclusion:

Aim of episode of behaviour: gathering information and forming judgement.

Positional Identity of actor: examiner.

Form of knowing: personal and cultural.

Behaviour identified: rephrasing, probing, pursing elaboration/justification, factual questioning.

As suggested so far, the repeated revisiting of the same issue with the candidate, is about putting a form of knowing about the culture into action – but also realising the examiner identity and the aim of gathering information and forming judgment. Putting his knowing about the culture into action here means understanding the characteristics of people that are good at what they do. Indeed, according to the assessment forms available ‘managing people’ and ‘continuous improvement’ are the two key competencies that the interview is designed to assess, in addition to aspects such as attitudes and personality traits (OD, 31.07). In addition to that, it is experience or knowing about personal attitudes and values – a form of personal knowing that underlines practitioner’s approach in their interview and behaviour(/what they do) (FN, 01.08, post interview with the candidate):

[…]

A1: Such attitude towards working with and leading others won’t get him far, I guarantee you that … the question is will he get better with some training?

A2: That’s the question … I really can’t think of anyone with his profile that we have actually gotten in, can you?

[…]

While a form of personal knowing that helps assessors make such decisions involves experience gained both within and beyond the workplace environment of Flow, knowing about the culture is embodied in this decision and it is tightly linked to the environment in Flow. Arguably, both condition and shape assessors’ behaviour (what they do) towards candidates.

RQ2. What are the characteristics of communication skills in use, which can inform curriculum development?

Identifying skills in relation to elements of communication in HR practice (encapsulated here by the categories of aims, positional identities and forms of knowing) is a very different process to breaking down jobs and task to behaviours then called skills – the skills requirement approach. The latter approach and following the premises of the cognitivist/individualistic view of skill implies that soft skills are behaviours learnt, carried as toolboxes, and applied across contexts. However, as evidence from their study as part of practice suggests, communication skills are doings that align to communication aims and the way people understand themselves in relation to their interlocutors (positional identities) and shaped often by practice-dependent (as well as independent) forms of knowing. This requires doing considerably more than having available a wide gamut of communication behaviours from a repository. It requires balancing between a constant awareness of contextual cues and a decision-making process as to ‘what is the appropriate action’ to best meet the situational requirements (Touloumakos Citation2011); this, as argued here, is where skill lies.

An emergent repertoire of actions is, therefore, appropriate for each individual occasion, and for this reason, these count as ‘skills’ exclusively within this specific context – right there and then. This, in turn, identifies the following characteristics about communication skills:

they are highly contextualised: can be understood and recognised as skills only within the specific episode of interaction,

they are transient in nature: any specific action can be potentially construed as a communication skill in a given situation, and

they are elusive: a doing that can be construed as skill in one instance will not be construed necessarily as a skill in a second instance.

The embeddedness, transience, and fleetingness of communication skills is what makes it meaningless to think of them in terms of set lists of de-contextualised behaviours (that break down work activities), and what forces us to rethink the meaning of soft skills, and with them issues of abstraction and transfer. In turn, the understanding of communication skills as instances of practice in this work is key when thinking about policies and future research in this area.

Discussion

In this paper, a paradox is recognised by juxtaposing the increasing numbers of people being trained and holding qualifications on soft skills with the recurrent demand and the current gap in soft skills reported in the labour market. This paradox is attributed, at least partly in this work, to the mainstream approach to identifying soft skills in need and the associated approach to their development – the skills-requirements approach. Against this cognitivist/individualistic view, this work proposes the use of an evidence-based situated view of skills – the skills-utilisation approach to their study (skills as situated actions), taking the first step, a step back rather, towards moving forward in the study of soft skills.

This situated approach reveals that communication skills cannot be recognised simply by identifying a set of decontextualised behaviours employed in the various instances and arbitrarily calling them communication skills. Communication skills, in this view, can be understood best as situated actions and, therefore, as part of practice(s), the HR practice(s) in this work. HR practices in this study involved specific routines, norms, rules for activity. It is argued here that participation in these practices meant shaping them but also understanding the different elements of practice, and that this was what enabled practitioners to navigate straightforwardly communication encounters from different positions, for different purposes and bringing into their practice their experience and various forms of knowing.

The role of purpose in human action can be traced back to Tolman (Citation1928), and later to the work of Leont’ev (Citation1974, Citation1978) and Engeström (Citation1999) and the object as that which motivates and determines the direction of human activity, and that which distinguishes between different activities. Similarly, positional identity directs us to consider the relational aspect in the process of evaluating desires, reflecting on the potential ramifications of choices and enacting their final choice enacting their agency (Taylor Citation1985). Given that agency is shaped by but also produces practice (Feldman and Orlikowski Citation2011), positional identity also directs us to consider that how one is and sees oneself in relation to others is embodied in how one communicates as engaging with various HR practices, and therefore, it is central and inseparable from the enactment of communication skills. Finally, various forms of knowing are produced by and realised in communication skills too (for example, knowing about the HR scientific methodology, epistemic knowing by Knorr Cetina (Citation1991), or knowing about others (Edwards Citation2010)). This reciprocal relationship between knowing and doing underlies communication skill, and it is reflected in the much improvising, revising, amending, and refining HR professionals engage in as part of their communication.

Taken together, these three factors were found to be key in recognising communication skills and their characteristics in this study. Because HR practitioners have experience in conducting Assessment Centres (as an example of HR practices), appreciate what the organisation looks for in a candidate, understand how to work with each other, they can work with their aim to gather information about candidates, alone examining the candidate in one instance and but also in collaboration with other HR members to form judgments about candidates. Membership in this practice, moreover, enables them to communicate as an employee-employer mediator in one instance and as an advisor in the next instance, and moving from looking to update people, to looking to support, or to manage people, often in successive encounters. This constant manoeuvering between different tasks embodies who they are and what they bring to their practice, but most importantly, it encapsulates being a member of this practice and putting knowing about the idiosyncrasies of the tasks at hand, the job, the people involved, the organisation, every time, into action. Accordingly, it encapsulates what is going on at the individual level but goes considerably beyond it.

The approach taken in this study is novel and has implications at the policy and research levels. At the policy level, an alternative research-driven understanding of communication skills is proposed (Touloumakos, Citationunder review). Against a background of studies that lead to communication skills taxonomies, this study proposes studying skills as part of communication encounters in HR practice that helps rendering intelligible where skill lies in a way that can inform how to best develop such skill, and accredit it (indicatively Ingols and Shapiro Citation2014; Kantrowitz Citation2005; Weber et al. Citation2013). At the research level, important is the generation of the analytic categories identifying communication skills. Clearly more research is needed to claim a robust and tested framework of the most important contextual categories/factors in identifying communication skills as part of practice. An additional study would allow solidifying these or other/more contextual aspects of practice that contribute towards understanding the nature of skill. The validation of the properties and functionality of the analytic categories developed would be valuable too, with different practices and in different contexts (national or other).

Supplementary_Material_final.docx

Download MS Word (29.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr Eleni Stamou and Dr Alexia Barrable for their insightful comments on this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Examples are the SCANS in the US, or the Key Skills Qualifications in the UK.

2 Observation of various events/activities in the two organisations was primarily as a non-participant observer. In some cases, such as for example during some training courses, participant observations were used. The material presented here derives exclusively from non-participant observations.

3 While it is acknowledged that the term ‘behaviour’ resides more with an individualistic view of skills, it was maintained as an analytic category in this study, to denote a decontextualised view of what people do that needs to become contextualised before we can understand communication skills enactment and their characteristics. To highlight the need for this shift a parenthesis with the phrase ‘what people do’ will follow the term ‘behaviour’ from this point onwards.

References

- Anderson, J., L. M. Reder, and H. A. Simon. 1996. “Situated Learning and Education.” Educational Research 25 (4): 5–11. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X025004005.

- Andoh-Arthur, J. 2019. “Gatekeepers in Qualitative Research.” In SAGE Research Methods Foundations (Encyclopedia Project), edited by P. Atkinson, S. Delamont, A. Cernat, J. W. Sakshaug, and R. A. Williams, 1–15. London: SAGE Publications.

- Andrews, J., and H. Higson. 2008. “Graduate Employability, ‘Soft Skills’ Versus ‘Hard’ Business Knowledge: A European Study.” Higher Education in Europe 33 (4): 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/03797720802522627.

- Anju, A. 2009. “A Holistic Approach to Soft Skills Training.” IUP Journal of Soft Skills 3 (3/4): 7–11.

- Anthony, S., and B. Garner. 2016. “Teaching Soft Skills to Business Students: An Analysis of Multiple Pedagogical Methods.” Business and Professional Communication Quarterly 79 (3): 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329490616642247.

- Attewell, P. 1990. “What Is Skill?” Work and Occupations 17 (4): 422–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888490017004003.

- Bereiter, C. 2002. Education and Mind in the Knowledge Age. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence.

- British Educational Research Association. 2004. “Revised ethical guidelines for educational research.” Accessed September 29, 2021. https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/revised-ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2004.

- Burke, M. A., A. Sasser, S. Sadighi, R. B. Sederberg, and B. Taska. 2020. No Longer Qualified? Changes in the Supply and Demand for Skills Within Occupations (No. 20-3). Working Papers.

- Cacciolatti, L., S. H. Lee, and C. M. Molinero. 2017. “Clashing Institutional Interests in Skills Between Government and Industry: An Analysis of Demand for Technical and Soft Skills of Graduates in the UK.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 119: 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.03.024.

- Cappelli, P. H. 2015. “Skill Gaps, Skill Shortages, and Skill Mismatches: Evidence and Arguments for the United States.” ILR Review 68 (2): 251–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793914564961.

- Capsada-Munsech, Q. 2017. “Overeducation: Concept, Theories, and Empirical Evidence.” Sociology Compass 11 (10): e12518. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12518.

- Constable, S., and A. K. Touloumakos. 2009. Satisfying Employer Demands for Skills. London: The Work Foundation.

- Cunningham, D. 2004. "Professional Practice and Perspectives in the Teaching of Historical Empathy." DPhil Thesis, Oxford: Department of Educational Studies.

- Cunningham, W., and P. Villaseñor. 2014, May. Employer Voices, Employer Demands, and Implications for Public Skills Development Policy. The World Bank. Research Working Paper No. 6853. Available at SSRN:https://ssrn.com/abstract=2433321

- Edwards, A. 2010. Being an Expert Professional Practitioner: The Relational Turn in Expertise. Dordrecht: Springe.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., and M. E. Graebner. 2007. “Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges.” The Academy of Management Journal 50 (1): 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888.

- Engeström, Y. 1999. “Activity Theory and Individual and Social Transformation.” In Perspectives on Activity Theory, edited by Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, and R.-L. Punamäki, 19–30. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Eraut, M. 1994. Developing Professional Knowledge and Competence. London: Falmer.

- Eraut, M., and W. Hirsch. 2007. The Significance of Workplace Learning for Individuals, Groups and Organisations (Monograph). Oxford: ESRC Centre on Skills, Knowledge and Organisational Performance, Oxford and Cardiff Universities.

- Fairhurst, G. T., and L. L. Putnam. 2019. “An Integrative Methodology for Organizational Oppositions: Aligning Grounded Theory and Discourse Analysis.” Organizational Research Methods 22 (4): 917-940.

- Feldman, M. S., and W. J. Orlikowski. 2011. “Theorizing Practice and Practicing Theory.” Organization Science 22 (5): 1240–1253. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0612.

- Finch, D. J., L. K. Hamilton, R. Baldwin, and M. Zehner. 2013. “An Exploratory Study of Factors Affecting Undergraduate Employability.” Education+ Training 55 (7): 681–704. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-07-2012-0077.

- Fixsen, A., S. Cranfield, and D. Ridge. 2018. “Self-Care and Entrepreneurism: An Ethnography of Soft Skills Development for Higher Education Staff.” Studies in Continuing Education 40 (2): 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2017.1418308.

- Gherardi, S. 2010. “Telemedicine: A Practice-Based Approach to Technology.” Human Relations 63 (4): 501–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709339096.

- Given, L. M., ed. 2008. The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963909.

- Glaser, B. G. 1965. “The Constant Comparative Method of Qualitative Analysis.” Social Problems 12: 436–445. http://doi.org/10.2307/798843.

- Glaser, B. G., and A. L. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

- Hammersley, M. 1995. “Theory and Evidence in Qualitative Research.” Quality and Quantity 29 (1): 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01107983.

- Hammersley, M., and P. Atkinson. 2007. Ethnography: Principles in Practice. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

- Handel, M. J. 2012. Trends in Job Skill Demands in OECD Countries. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No, 120–120.

- Holland, D., W. Lachicotte, D. Skinner, and C. Cain. 1998. Identity and Agency in Cultural Worlds. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hurrell, S. A. 2016. “Rethinking the Soft Skills Deficit Blame Game: Employers, Skills Withdrawal and the Reporting of Soft Skills Gaps.” Human Relations 69 (3): 605–628. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715591636.

- Hurrell, S. A., D. Scholarios, and P. Thompson. 2013. “More Than a ‘Humpty Dumpty’ Term: Strengthening the Conceptualization of Soft Skills.” Economic and Industrial Democracy 34 (1): 161–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X12444934.

- Ingols, C., and M. Shapiro. 2014. “Concrete Steps for Assessing the “Soft Skills” in an MBA Program.” Journal of Management Education 38 (3): 412–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562913489029.

- Jain, S., and A. S. S. Anjuman. 2013. “Facilitating the Acquisition of Soft Skills Through Training.” IUP Journal of Soft Skills 7 (2): 32.

- Kantrowitz, T. M. 2005. “Development and Construct Validation of a Measure of Soft Skills Performance.” PhD thesis, Department of Psychology, Georgia Institute of Technology – Atlanta, US.

- Knorr Cetina, K. 1991. “Epistemic Cultures: Forms of Reason in Science.” History of Political Economy 23: 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1215/00182702-23-1-105.

- Konkola, R., T. Tuomi-Gröhn, P. Lambert, and S. Ludvigsen. 2007. “Promoting Learning and Transfer Between School and Workplace.” Journal of Education and Work 20 (3): 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080701464483.

- Lave, J. 1991. “Situated Learning in Communities of Practice.” In Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition, edited by L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, and S. D. Teasley, 63–82. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leont'ev, A. N. 1974. “The Problem of Activity in Psychology.” Soviet Psychology 13 (2): 4–33. https://doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-040513024.

- Leont'ev, A. N. 1978. Activity, Consciousness, and Personality. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- LINCS. 2020. “There is Nothing Soft About Soft Skills.” Accessed May 26. https://community.lincs.ed.gov/discussion/theres-nothing-soft-about-soft-skills.

- Madsen, J. B., and F. Murtin. 2017. “British Economic Growth Since 1270: The Role of Education.” Journal of Economic Growth 22 (3): 229–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-017-9145-z.

- Martin, John P. 2018. Skills for the 21st Century: Findings and Policy Lessons from the OECD Survey of Adult Skills, IZA Policy Paper, No. 138, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Bonn.

- Matteson, M. L., L. Anderson, and C. Boyden. 2016. “‘Soft Skills’: A Phrase in Search of Meaning.” Portal: Libraries and the Academy 16 (1): 71–88. http://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2016.0009.

- McHugh, M. L. 2012. “Interrater Reliability: The Kappa Statistic.” Biochemica Medica 22 (3): 277–282. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2012.031.

- Mori, J., and D. Stroud. 2021. “Skills Policy for Growth and Development: The Merits of Local Approaches in Vietnam.” International Journal of Educational Development 83: 102386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102386.

- Nickson, D., C. Warhurst, J. Commander, S. A. Hurrell, and A. M. Cullen. 2012. “Soft Skills and Employability: Evidence from UK Retail.” Economic and Industrial Democracy 33 (1): 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X11427589.

- OECD. 2016. Employment and Skills Strategies in Saskatchewan and the Yukon, OCED Reviews of Local Job Creation. Paris: OECD Publishing. http://doi.org/10.1787/9789264259225-en

- Patton, M. Q. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Polanyi, M. (1958) 1962. Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Remedios, R. 2012. “The Role of Soft Skills in Employability.” International Journal of Management Research and Reviews 2 (7)): 1285.

- Saavedra, A. R., and V. D. Opfer. 2012. “Learning 21st-Century Skills Requires 21st-Century Teaching.” Phi Delta Kappan 94 (2): 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171209400203.

- Srivastava, P., and N. Hopwood. 2009. “A Practical Iterative Framework for Qualitative Data Analysis.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8 (1): 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800107.

- Stake, R. E. 2000. “Case Studies.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin, and Y. S. Lincoln, 2nd ed., 435–454. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Stein, D. 1998. Situated Learning in Adult Education, 640–646. ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education, Center on Education and Training for Employment, College of Education, the Ohio State University.

- Succi, C., and M. Canovi. 2020. “Soft Skills to Enhance Graduate Employability: Comparing Students and Employers’ Perceptions.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (9): 1834–1847. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1585420.

- Sutherland, J. 2012. “Qualifications Mismatch and Skills Mismatch.” Education + Training 54 (7): 619–632. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911211265666.

- Taylor, C. 1985. Human Agency and Language: Philosophical Papers 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tolman, E. C. 1928. “Purposive Behavior.” Psychological Review 35: 524–530. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0070770.

- Touloumakos, A. K. 2011. “Now You See it, Now You Don’t: The Gap Between the Characteristics of Soft Skills in Policy and in Practice.” Ph.D. thesis, Oxford University, Oxford.

- Touloumakos, A. K. 2020. “Expanded Yet Restricted: A Mini Review of the Soft Skills Literature.” Frontiers in Psychology 11: 2207. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02207.

- Touloumakos, A. K. under review. Soft Skills Curriculum Revisited: The Importance of Immersion With the Context, Metacognitive Awareness, and Guidance, submitted to Educational Studies (Manuscript ID: HEDS-2021-0201).

- Tseng, H., X. Yi, and H. T. Yeh. 2019. “Learning-Related Soft Skills Among Online Business Students in Higher Education: Grade Level and Managerial Role Differences in Self-Regulation, Motivation, and Social Skill.” Computers in Human Behavior 95: 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.035.

- Weber, M. R., A. Crawford, J. Lee, and D. Dennison. 2013. “An Exploratory Analysis of Soft Skill Competencies Needed for the Hospitality Industry.” Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism 12 (4): 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2013.790245.

- WEF/World Economic Forum. 2015. New Vision for Education: Unlocking the Potential of Technology. New York, NY: Author. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEFUSA_NewVisionforEducation_Report2015.pdf.

- Winterbotham, M., G. Kik, S. Selner, S. Whittaker, and J. H. Hewitt. 2020. Employer skills survey 2019. Research Report. Department for Education.

- Wolf, A. 2009. “Misunderstanding Education.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 41 (4): 10–17. https://doi.org/10.3200/CHNG.41.4.10-17.

- Znaniechi, F. 1934. The Method of Sociology. New York: Farrar & Rinehart.