ABSTRACT

There has been little research into the impact of textbook costs on higher education in the United Kingdom. To better understand textbook use patterns and the issues faced by UK students and educators the UK Open Textbooks Project (2017–2018, http://ukopentextbooks.org/)) conducted quantitative survey research with United Kingdom educators in September 2018. This article reports on the findings of this survey, which focussed on awareness of open educational resources; textbook use and rationale; awareness and use of open textbooks; and open licensing. Results reveal fertile ground for open textbook adoption with potential to support a wide range of open educational practices. The findings indicate strategies for supporting pedagogical innovation and student access through the mainstream adoption of open textbooks.

Introduction

Open textbooks have dominated the mainstreaming of open educational resources (OER) in North America (Pitt, Citation2015). The Hewlett Foundation–funded United Kingdom Open Textbooks Project (2017–2018) (UKOTB, http://ukopentextbooks.org/) had two aims: firstly, and primarily, to evaluate in the UK context two highly successful and contrasting approaches to raising awareness and encouraging the adoption of open textbooks; secondly, to investigate awareness and use of (open) textbooks within UK higher education (HE).

Survey results provide much needed insights into current UK educator experiences and their awareness of textbooks and open licensing. This article presents and contextualizes these results within existing research (see also Rolfe & Pitt, Citation2019; Farrow et al., Citationin press; and the main report on the project, which includes provisional findings from this survey, Pitt et al., Citation2019).

By examining the survey findings through the lens of open educational practices (OEP), the findings contribute to the emerging field of UK-specific research on OER and OEP and provide recommendations for increasing the visibility of open approaches.

OER and OEP

UKOTB utilized the Hewlett Foundation definition of OER:

OER are teaching, learning and research resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under an intellectual property license that permits their free use and re-purposing by others. (Hewlett Foundation, Citationn.d.)

The term open textbook refers to a particular type of OER. A textbook is “a book that contains detailed information about a subject for people who are studying that subject” (Cambridge Dictionary, Citationn.d.). An open version of a textbook has an open license which (minimally) enables the book to be shared without restriction or seeking additional permissions. The license may also allow for the content to be modified or used commercially, enabling the textbook to be better adapted for specific contexts (Wiley, Citation2014).

As Cronin (Citation2017) and Cronin and MacLaren (Citation2018) observed, definitions of open education (and OER) have constantly developed to accurately capture what is meant by open within particular contexts. Within this endeavor, there has also been the relatively recent emergence of the term OEP, which emphasizes open types of practice (Cronin & MacLaren, Citation2018, p. 128). Broadly speaking, the current literature offers two approaches to defining OEP (see also Cronin, Citation2017).

The first is based around Wiley’s (Citation2014) 5Rs (retain, reuse, revise, remix, redistribute), which Wiley (Citation2013, Citation2017) argued enable the possibility of OEP. In other words, the characteristics of OER (as defined by the 5Rs) are a precondition of OEP. To cite Wiley: “open pedagogy is that set of teaching and learning practices only possible in the context of the free access and 4R [now 5R] permissions characteristic of open educational resources” (Wiley, Citation2013, Citation2017). More recently, Wiley and Hilton (Citation2018, p. 135) have developed the term OER-enabled pedagogy “in many ways a combination of openness as characterized by the 5Rs and Papert’s (1991) notion of constructivism.” The more narrowly focussed term OER-enabled pedagogy complements “expansive definitions of OEP” (Cronin & MacLaren, Citation2018, p. 128) while providing clear parameters for OER and/or OEP impact research, supported by tools such as the COUP (cost, outcomes, usage and perceptions) framework (Open Education Group, Citationn.d.).

The second, broader definition of OEP recognizes the creation and use of OER but does not exclude activities or resources that are not directly linked to or derived from OER. This inclusive definition comprises any activities that could broadly be described as open (Beetham et al., Citation2012; Hegarty, Citation2015; Nascimbeni & Burgos, Citation2016). Nascimbeni and Burgos (Citation2016) observed that, while definitions like Wiley’s (Citation2013) imply a linear progression from using OER to developing OEP, there are many attitudes or activities that can be described as open and that do not involve openly licensed materials. For example, Lalonde (Citation2017) described open sharing on the Web by students without the use of open licenses, which fulfils all but one—the open licensed asset—aspect of OER-enabled pedagogy criteria set out by Wiley and Hilton (Citation2018).

Discussions of OEP similarly indicate that certain values or attitudes are potentially important. Hegarty (Citation2015, p. 3) noted: “Immersion in using and creating OER requires a significant change in practice and the development of specific attributes, such as openness, connectedness, trust, and innovation.” While incentivization and support at an institutional level might encourage the use of OER and/or OEP and contribute toward this transformation, there could be other factors that influence receptiveness to open such as attitude or disposition (Jhangiani et al., Citation2016). However, research into the attitude or disposition of OER and/or OEP adopters remains limited.

The North American context

There has been an increase in North American educators and students engaging with OER as a result of legislation and advocacy to promote the use of open textbooks. In the United States of America (USA) groups such as the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC) and Student Public Interest Research Groups (PIRGs) have coordinated actions nationally and at state level. USA educator use and awareness of OER rose steadily over between 2014 and 2018. The “Babson Report” (which regularly surveys US HE educators) reported in 2018 that 46% of a sample of 4000 respondents had varying degrees of awareness of OER compared with 34% for the 2013–2014 period (Seaman & Seaman, Citation2018, pp. 7–8). Federal support for open textbooks was achieved in 2018 when $5 million funding was allocated for the development of open textbooks by individual institutions (Allen, Citation2018).

The uptake of open textbooks has been supported by arguments for increased access to resources, increased participation, and the cost of textbooks. In early 2019, total student debt in USA stood at $1.5 trillion (Cilluffo, Citation2019) with students graduating in 2018 owing $29,200 on average (The Institute for College Access and Success, Citation2019). It is these levels of debt, coupled with the contribution of high textbook costs, which impact directly on student choice of course, behavior, and attainment (Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition, n.d.).

Open textbooks have proved a particularly effective introduction to OER as educators can easily swap proprietary textbooks for an open alternative, particularly as in the USA college and university educators typically develop courses based around specific textbooks. Increases in open textbook use has been supported by the provision of materials aligned with the scope and sequence of a whole course such as OpenStax (https://openstax.org) and membership initiatives such as the Open Textbook Library (https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/).

There has simultaneously been a concerted effort to increase the amount of peer-reviewed research on OER impact. In North America, initiatives such the Open Education Group’s OER Research Fellowships scheme developed the COUP framework to support the production of OER impact research (Open Education Group, Citationn.d.). Their fellowship scheme and support for individual researchers has resulted in “a rapid rise in research related to OER efficacy and perceptions with more published studies in the past 3 years than the previous fifteen” (Hilton, Citation2019).

In Canada, the province-wide British Columbia Open Textbook project is supporting educators to create a range of open textbooks in core subjects (BCcampus, Citationn.d.), while eCampusOntario is funding the development of curriculum-aligned open textbooks in the province (eCampusOntario, Citationn.d.). Jhangiani and Jhangiani (Citation2017) were the first to report on Canadian student experiences of open textbooks, and there is a growing body of open textbook impact research in the Canadian context (e.g., see Hendricks et al., Citation2017; Jhangiani et al., Citation2018; Jhangiani et al., Citation2016; Ross et al., Citation2018).

Open textbooks in the UK

There is also a growing number of open textbook initiatives and research outside of the USA. For instance, in South Africa, Jimes et al. (Citation2013) and Pitt and Beckett (Citation2014) explored the use of Siyavula open textbooks (https://www.siyavula.com/). The Digital Open Textbooks for Development project (http://www.dot4d.uct.ac.za/about-32) aims to increase the amount of research on open textbook use in South Africa. However, awareness and use of open textbooks are typically low outside North America, including the UK.

Course reading lists are a staple of study in UK HE (Stokes & Martin, Citation2008). Consequently, in relation to OER and open textbooks, the swapping of proprietary resources for open versions is less applicable in the UK context, and nuanced arguments for ease of use are needed (Pitt et al., Citation2019).

There are a range of financial pressures on UK students, including tuition fees and rising accommodation costs (Packham & Hall, Citation2019). UK tuition fees were introduced in 1998 and capped at £1000 (Wikipedia, Citationn.d.) but have risen steadily to be capped at £9250 for the 2019–2020 academic year (Universities and Colleges Admissions Service, Citation2020). While the UK has different fee and funding mechanisms in place across the four regions (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland) (see Universities and Colleges Admissions Service, Citation2020), graduates from English universities have been described by the Institute of Fiscal Studies as “having the highest student debts in the developed world” (Belfield et al., Citation2017). A House of Commons Library Briefing Paper noted that 2012 graduates owed an average of £36,000 (Bolton, Citation2019, p. 3), the change in policy in 2015 has resulted in graduates having “average debts of £50,000” with low income students hit hardest (Belfield et al., Citation2017).

In the UK, reports on the cost of materials such as textbooks are limited and do not distinguish between discipline (see Kernohan & Rolfe, Citation2017). Students are dissatisfied with the cost of course materials and the hidden participation costs of university study, which include the cost of materials for their studies (Office for Students, Citation2018). Of the 1652 students surveyed by CourseSmart and NUS in 2012, 81% “felt that universities should be offering textbooks free, as part of their fees” (NUS, Citation2012). In a minority of institutions, student dissatisfaction has resulted in a change of approach. At The University of Essex, for example, potential students are advised that “core textbooks are always provided free of charge to our students, included within the course fees” (University of Essex, Citation2016).

Rolfe (Citation2018) surveyed two cohorts of science students (N = 69) at De Montfort University and University of the West of England. This survey focussed on students’ experiences of textbooks, finding that respondents at various stages of study spend an average of £187.30 on materials per year. Of particular note is Rolfe’s finding that “high textbook prices influence student behaviour … Similar observations have been reported in the US with students not purchasing required texts or altering their choice of classes (modules) (Senack, 2014)” (Rolfe, Citation2018, p.11). Given the significant parallels with the North American context regarding cost and publisher practices, Rolfe’s study also reveals student concerns with more UK-specific practices, highlighting the need for course reading lists to be clearer on “what was meant by recommended/core and essential reading, and what was expected of [students]” (Rolfe, Citation2018, p. 11). Similar concerns were raised by Stokes and Martin (Citation2008, especially p. 21), who surveyed the limited research into the role of such lists at different stages of study.

There is currently very little available research on educator or student perceptions of OER or open textbooks within the UK context (Pitt et al., Citation2019; Rolfe, Citation2018). OER impact research conducted by major initiatives such as the UK-based OER Hub (http://oerhub.net) had a largely North American focus during its initial phases. Initiatives such as JISC and the Higher Education Academy’s UKOER program focussed on supporting and understanding OER use and OEP and a range of outputs including case studies, tools, and reports (see, e.g., JISC, n.d; McGill et al., Citation2013) rather than promotion, or research into the impact, of specific types of OER. Impact research on such cases is sparse: there are currently no efficacy studies, and research into UK educator levels of OER awareness similarly remains limited (see, e.g., the survey of Scottish educators by de los Arcos et al., Citation2016). However, despite pedagogical differences and the difference in maturity of the OER landscapes under discussion, UK educators have reported similar concerns regarding OER to those described by USA educators (e.g., visibility/findability of OER and quality) (de los Arcos et al., Citation2016; de los Arcos et al., Citation2014; Seaman & Seaman, Citation2017).

Methods

The UKOTB survey was divided into two sections and comprised 25 questions. The first part of the survey focussed on demographic questions such as location, age, employment sector (e.g., further education or HE), and employment status with an additional set of questions focussed on respondent teaching practices and experiences. Data points included role, years of experience, discipline, and instructional preferences.

The second half of the survey focussed on textbook use and rationale. Textbook users were asked about how they recommend resources: formats; the way decisions about student resources are made; expectations regarding student use and purchase of books; and the factors that influence the inclusion of textbooks in teaching. All respondents, whether current textbook users or not, were asked about their awareness of open licensing, OER, and open textbooks. The final survey question asked respondents to share any experiences or thoughts regarding textbook use.

The UKOTB survey drew on a number of questions from Seaman and Seaman (Citation2017, Citation2018), including those on instructional preferences (e.g., print or digital, use of own or others’ material, style of delivery), teaching status and years of experience, age, licensing, and OER awareness. Modified versions of questions on respondent involvement in textbook selection and the types of course taught by respondents were also included. A number of questions were also drawn from Rolfe’s (Citation2018) survey of UK students at two English universities.

Over 4000 UK educators were invited via email to participate during September 2018. The survey was open for 3 weeks and was facilitated by a commercial company. To increase the number of responses, the survey was incentivized, and participants could opt to be entered into a prize draw for £100.

Results

Demographics and teaching experience

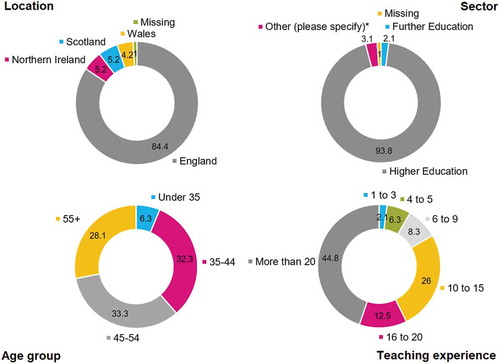

A total of 96 UK academics from a range of disciplines completed the survey during September 2018. The majority of respondents self-reported as being based in England (n = 81) and worked full-time in the HE context (n = 84 and n = 90 respectively). Current reported teaching roles were largely split across three groups, with respondents who were teachers, tutors, or instructors (31.3%, n = 30), module leads with teaching (26%, n = 25) and course or program leaders (26%, n = 25). Respondents came from three main age groups, with equal representation of the 35–44, 45–54, and 55+ age groups (32.3%, 33.3%, and 28.1% respectively). Of the sample, 57.3% (n = 55) had more than 16 years of teaching experience, with 44.8% (n = 43) of the survey’s total respondents reporting more than 20 years’ experience in educational settings. shows the demographic profile of the sample.

Respondents came from a diverse range of disciplines with more than 50% of the sample from the biological, mathematical and physical sciences (26%, n = 25) or humanities, language-based studies and archaeology (25%, n = 24). A multiple-choice question regarding types of teaching undertaken in the current academic year revealed that most respondents (78.1%, n = 75) had taught only face-to-face during that period. The remaining respondents, while also teaching online and/or blended/hybrid courses, also taught face-to-face courses.

Responses to a set of three sliding scale questions drawn from Seaman and Seaman (Citation2017) revealed that respondents had a strong preference for developing and designing their own courses and resources for teaching in comparison to making use of third-party content. There was an evenly balanced distribution of responses to a scale that asked respondents whether they preferred to teach via lectures or a more active “facilitated exploration of content” with students actively engaging with subject material. The final sliding scale question examined what kinds of media types, if any, participants preferred using in their teaching. Overall responses were fairly balanced between preference for print and preference for digital. However, a slight preference toward digital materials was observed.

Use of textbooks

Of the respondents, 81.9% (n = 77) reported using textbooks in whole or part in their teaching. Out of these 77 textbook users, 72 responded to a series of follow-up questions which examined textbooks use in more depth. The following results relate to this subsample.

A total of 61.1% (n = 44) of educators utilizing textbooks in their teaching recommended one or more key textbooks with additional readings. A total of 27.8% (n = 20) of respondents advised that they “recommend one or more core textbooks for essential reading,” while the remainder of respondents using textbooks reported either providing a reading list with no indication of priority of resources listed (9.7%, n = 7) or not giving much thought to what books are recommended (1.4%, n = 1).

Half of the educators (n = 36) in this subsample recommended a mix of print and online resources to their students, with a third (32%, n = 23) recommending textbooks in print format. A total of 16.7% (n = 12) recommended mainly digital and downloadable resources, with one respondent (1.4%) advising they recommended mainly non-downloadable digital resources to students.

Just over half of the respondents (52.8%, n = 38) had no expectation that students would purchase course materials. A total of 25% (n = 18) of educators assumed that learners would buy one book, with the remaining 22.2% (n = 16) expecting that students would purchase more than two books for a course.

Respondents reported a high degree of autonomy in their choice of materials, with 72.2% (n = 52) of respondents being solely responsible for choosing resources used in their teaching. A total of 20.8% of respondents are involved in or lead collective decision-making regarding textbooks (13.9%, n = 10 and 6.9%, n = 9 respectively). A minority of respondents (6.9%) reported having no or a noncritical role in the choice of materials.

Textbooks are integrated into teaching to varying degrees. While a minority of respondents base course content around specific textbooks (5.6%, n = 4) or make use of all the ancillary materials (1.4%, n = 1), just over 85% of respondents either flag resources as appropriate during their teaching or produce module reading lists which students should consult (31.9%, n = 23 and 54.2%, n = 39 respectively). Free-text comments received for this question reinforced the sense of diverse use and expectations.

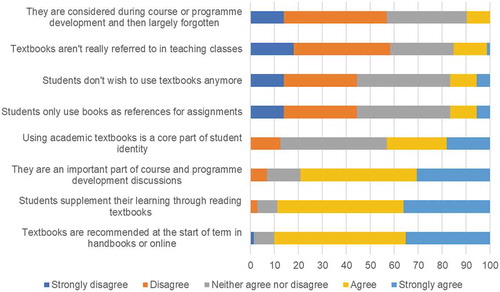

Participants were presented with a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree and a set of possible factors which might influence the materials they selected for use in their teaching (see ). Availability of resources in an institution’s library was by far the most important factor with 83.3% (n = 60) of our textbook user subsample reporting they strongly agreed or agreed with this statement. Of particular note is that 56.9% (n = 41) of all respondents strongly agreed that the library stocking the book was important to making a decision about whether to use it. Ensuring that materials are accessible in different formats was also an important consideration with nearly 70% (n = 53) of respondents strongly agreeing or agreeing with this influencing their selection, followed by a textbook offering “comprehensive content and learning activities” (69.4%, n = 50). Cost to students was also an important consideration although a small number of respondents did advise that cost was not a consideration when choosing materials for teaching. Familiarity with authors and publishers was considered important for respondents, as well as recommendations by colleagues.

Figure 2. Responses to survey question 18: Which of the following would influence your selection of textbooks to use in your teaching?

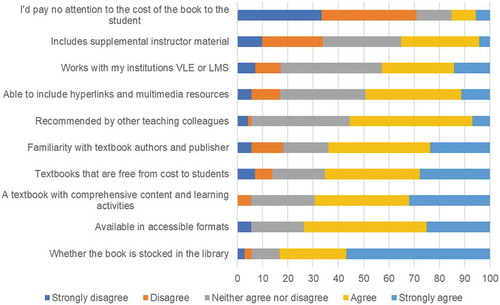

Finally, textbook users were asked to rank agreement with a series of more general statements regarding textbook use or perceptions of their use (see ). A total of 90.1% of respondents strongly agreed or agreed that course material recommendations were made at the start of term (n = 25 and n = 39, respectively). A total of 79.2% of educators strongly agreed or agreed with the statement that textbooks “are an important part of course and programme development discussions” (n = 22 and n = 35 respectively). Textbooks were also viewed as an important function outside of the virtual or face-to-face classroom with their role as “supplement[ing]” learning confirmed.

Awareness of open

Respondents were asked about awareness of different “licensing mechanisms.” A total of 57.3% of respondents advised that they were very aware or aware of Creative Commons (CC) licensing, with 27% (n = 24) being very aware and 30.3% (n = 27) aware. In contrast, 20.2% (n = 18) of educators advised they were unaware of CC, while around 5% of respondents reported either no awareness of copyright (4.5%, n = 4) or of public domain licensing (5.6%, n = 5). The majority of responses reported familiarity with CC, although in response to a subsequent question 42.7% (n = 38) of respondents advised they were “not aware of OER,” with a further 40.5% (n = 36) reporting limited awareness of OER.

Open textbook awareness and use were low. The percentage of respondents who were very aware or aware of open textbooks and their use was around 12% (3.4%, n = 3 and 9%, n = 8 respectively). A total of 47.2% (n = 42) of respondents had no awareness of open textbooks, with the remainder having minimal levels of awareness about their potential use. While the vast majority (82%, n = 73) of respondents reported using no open textbooks in their teaching, a tenth (10.1%, n = 9) of respondents expressed uncertainty about whether they were already using open textbooks in their teaching.

Of the 8% (n = 7) of respondents who reported using open textbooks for their teaching, there were varying levels of understanding of CC licensing. Of note is that two respondents advised they had no knowledge of OER. As might be expected, all respondents in this subsample reported awareness or strong awareness of open textbooks.

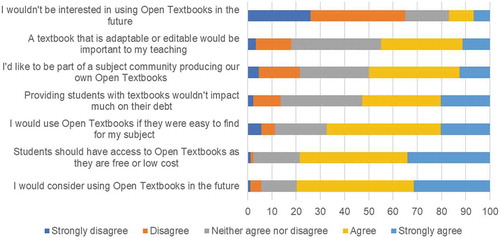

Finally, respondents were presented with a series of statements (see ) about open textbooks. Nearly 80% of respondents strongly agreed or agreed with the statement “I would consider using Open Textbooks in the future” (31.5%, n = 28 and 48.3%, n = 43 respectively). There was an awareness of cost and debt for students, with over 74.4% of respondents strongly agreeing or agreeing that students should have access to low-cost or no-cost open textbooks (34%, n = 30 and 44.3%, n = 39 respectively). However, a more mixed picture emerges in relation to textbooks and the impact on student debt, with 52.8% of respondents strongly agreeing or agreeing that providing students with textbooks would not impact much on their debt (20.2%, n = 18 and 32.6%, n = 29 respectively). Significantly, a third of respondents (33.7%, n = 30) were unsure about the impact of textbook costs.

Figure 4. Responses to survey question 24: Thinking about Open Textbooks, please indicate how you feel about the following statements.

A number of factors to encourage the use of OER and open textbooks were identified. Visibility of resources was key to respondents, with 67.3% advising that they “would use open textbooks if they were easy to find for [their] subject” (20.2%, n = 18 strongly agreed and 47.2%, n = 42 agreed). Although not explicitly listed, it was of note that 7 out of the 24 respondents who provided substantive responses (e.g., excluding “no” or similar responses) to the open question at the end of the survey (Q25) regarded the quality of a resource to be critical.

Half of the respondents were keen to be involved in the production of open textbooks as part of a “subject community” (12.5%, n = 11 strongly agreed and 37.5%, n = 33 agreed); and 44.9% of respondents indicated that the opportunity to revise material was important to their teaching (11.2%, n = 10 strongly agreed and 33.7%, n = 30 agreed).

While 65.2% of educators disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement of having no interest in using open textbooks in the future (39.3%, n = 35 and 25.8%, n = 23 respectively) a not insignificant minority of respondents (16.9%) advised that they had no interest in using open textbooks (6.7%, n = 6 strongly agreed and 10.1%, n = 9 agreed). Although the reasons for this are largely unknown, reviewing Q25 reveals that where participants did leave a comment, those who agreed or strongly agreed with this statement were more concerned with other factors, for example, “academic excellence” and more general “low student engagement with textbooks” than with reasons typically used to support the use of open textbooks (e.g., cost and the ability to reversion content). This may indicate further investigation is needed to generate relevant and compelling arguments to support the use of OER. Support from educator institutions was also a factor for over 45% of respondents (12.4%, n = 11 strongly agreed and 34.8%, n = 31 agreed) although a significant number (41.6%, n = 37) neither agreed nor disagreed that institutional support would influence their decision to use open textbooks.

Discussion

This sample group was comprised of experienced educators, with over 80% of the sample reporting more than 10 years’ teaching experience. There was a very strong preference for developing one’s “own curriculum” and autonomy for course design, and 70% of the sample reporting they were “solely responsible” for the choice of books they used. In terms of OEP and OER, the high level of autonomy among UK HE educators seems to have critical potential as an enabler. As Nascimbeni and Burgos (Citation2016) noted, there has been long-term recognition of the role of the individual educator as being central and key to open practice. How best to raise awareness of and support educators in their use of OER and/or OEP is likely to require a multifaceted approach, however, particularly as the perceived importance of institutional support for such endeavors varied among respondents. The importance of “local champions” within institutions could potentially provide one approach (Nascimbeni et al., Citation2018, p. 511).

As the subsample of educators who have little or no responsibility for resource choice is small, further research is required to examine whether length of teaching experience or working patterns are factors (although there appears to be no relation to full- or part-time status, it does appear that most of these respondents had fewer than 15 years’ teaching experience). Moreover, whether staff are employed on permanent contracts is an important factor in relation to autonomy. In the USA, community colleges are often dependent on short-term contracted staff who lack this autonomy since teaching materials are selected by colleagues on permanent contracts (see, e.g., Iuzzini et al., Citation2017). Across UK HE, there are growing levels of casualisation and “atypical contracts” (Higher Education Policy Institute, Citation2019). It therefore seems pertinent to examine the impact structural changes are having on practitioner autonomy.

Few of the educators surveyed choose to base their courses around specific textbooks. Where participants commented on how they recommended reading, responses varied. Several respondents highlighted that while textbooks were useful early on, it was anticipated that students would consult a wider range of reading as they progressed through their studies.

A total of 79.2% of textbooks users strongly agreed or agreed with the claim that textbooks were “an important part of course and programme development discussions.” Similarly, many respondents anticipated that students would consult textbooks as part of their learning. It is of note that respondents using textbooks in their teaching appear to provide clear guidance for the priority of reading materials; a total of 88.9% recommend core textbooks either as essential reading or as core material with additional readings. The range of textbooks that can be highlighted by reading lists and, arguably, educator awareness of cost and availability of resources in the library (the latter being a key factor for the majority of respondents) may be the reason why there is a fairly even split between those who have no expectation that students will purchase any materials and those who expect students to buy at least one book.

In contrast to the NUS and CourseSmart survey in 2012, where the majority of student respondents reported using Internet-enabled devices for study, around a third of our respondents reported recommending only print textbooks. However, 50% of educators mainly recommend both print and online materials to their students.

Although this study reveals low levels of OER awareness similar to those in previous UK HE studies (e.g., de los Arcos et al., Citation2016), there remains potential for open textbooks. Lack of familiarity with OER and open textbooks appear not to be a barrier to future use in this sample. As seen in other UK surveys (e.g. de los Arcos et al., Citation2016) and within the US context (Seaman & Seaman, Citation2017), similar levels of disconnect between recognition of CC licensing and OER have been observed. However, whether a CC licensed resource is an OER may depend on license type. For example, NoDerivatives-licensed resources do not enable remix or revision and are therefore not classified as OER (see Green, Citation2014)—a key aspect of the 5Rs which are often used to characterize OER (Wiley, Citation2014).

Recommendations

The survey findings highlight key areas on which to focus efforts. The high level of interest in co-authoring material with others working in the same or similar disciplines may provide one gateway to engaging educators with OEP and OER. It also potentially highlights the foregrounding of remix in introductory discussions (Pitt et al., Citation2019), particularly if this sample’s autonomy with regard to resource choice is representative. Visibility of resources and comments regarding quality support research findings in both the UK and USA contexts regarding the importance of these factors when choosing OER (e.g., Seaman & Seaman, Citation2017). The importance of these factors to survey respondents also indicates the need to clarify what role open textbooks could play. Sufficient local information (e.g., around funding and quality) is required alongside more established advice (such as where to find OER).

Access and accessibility were highlighted as important to educators, both in terms of a resource being available in the library and/or in relation to cost or format. Familiarity with a resource or recommendations from others were also important for this sample. These factors indicate potential tipping points for mainstreaming use of OER and/or open textbooks and are broadly similar to those noted in other contexts (see Seaman & Seaman, Citation2017, Citation2018). A total of 83.3% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that course material being available in the library (and therefore accessible to students) was an important consideration. This arguably highlights the important role of librarians and subject specialists in selecting relevant stock and working with faculty to ensure materials are available.

Finally, with a third of respondents seemingly unsure about whether the provision of textbooks would reduce student debt, more research is needed to help evidence any claims made regarding cost savings. Respondents were keen to reduce student debt. Two respondents advised that their institution was already providing textbooks to their students, while another noted:

This is a great initiative! Student poverty is a great concern for me. To have something like this in place means they can focus a little more on their learning, rather than having to worry about how to feed themselves, pay rent AND buy books. Thank you!!!

Conclusion

This article has presented the results of a survey with UK HE educators on the existing and potential use of open textbooks. Findings indicate several strategies to facilitate the use and adoption of such resources for pedagogical innovation. The adoption of open textbooks is enabling and supporting a wide range of OEP; the results presented here provide endorsement for the use of open textbooks as a vector for innovation.

Engaging with individual educators and providing a multifaceted approach to supporting engagement with OER and/or OEP are key to innovating practice around curriculum provision and delivery. Further research and a deeper understanding of both the student and educator experience and certain aspects of the UK education system are required, but there is much potential for open textbooks in UK HE and further education. Raising awareness remains critical to OER-enabled pedagogy (Wiley & Hilton (Citation2018) and OEP. This can be approached through focussing discussion on factors that are considered important by UK educators (such as the visibility of open materials). Open textbook initiatives in Europe should reflect differences between education systems, such as the degree to which educator curriculum choices are autonomous.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this work would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Hewlett Foundation for funding the UK Open Textbook Project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rebecca (Beck) Pitt

Rebecca (Beck) Pitt is a research fellow in the Institute of Educational Technology at The Open University (UK). She is a member of the OER Hub, which works collaboratively to investigate the impact of open education. Her research interests include open textbooks, informal learning, and widening participation.

Katy Jordan

Katy Jordan is a research associate with the EdTech Hub, based at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. Her research interests broadly focus on the impact of the Internet and digital technologies on education, with specific interests in social media, educational technology, and open education.

Beatriz de los Arcos

Beatriz de los Arcos holds a PhD in education (The Open University, UK). She is a learning developer for open, online, and blended courses, and open education process manager at the Extension School in Delft Technical University (The Netherlands).

Robert Farrow

Robert Farrow is a research fellow in the Institute of Educational Technology at The Open University (UK) and has led and contributed to research projects in open education, accessibility, mobile learning, and digital scholarship. He has research interests in evidence; decision-making and policy formation; ethics; and ideology in educational technology.

Martin Weller

Martin Weller is director of the OER Hub and GO-GN network. Weller chaired The Open University’s first major online e-learning course in 1999, which attracted 15,000 students. He is the author of the openly licensed The Battle for Open (2014) and 25 Years of Ed Tech (2020).

References

- Allen, N. (2018, March 20). Congress funds $5 million open textbook grant program in 2018 spending bill. Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition. https://sparcopen.org/news/2018/open-textbooks-fy18/

- BCcampus. (n.d.). Open textbooks. https://open.bccampus.ca/open-textbook-101/

- Beetham, H., Falconer, I., McGill, L., & Littlejohn, A. (2012). Open practices: A briefing paper. JISC. https://oersynth.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/58444186/Open%20Practices%20briefing%20paper.pdf

- Belfield, C. Britton, J. Dearden, L., & van der Erve, L. (2017, July 5). Higher education in England: Past, present and options for the future (Briefing note). Institute for Fiscal Studies. https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/9334

- Bolton, P. (2019). Student loan statistics (Briefing Paper no. 1079). House of Commons. https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN01079#fullreport

- Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.). Textbook. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/textbook

- Cilluffo, A. (2019, August 13). Five facts about student loans. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/08/13/facts-about-student-loans/

- Cronin, C. (2017). Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5), 1–21. 10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096

- Cronin, C., & MacLaren, I. (2018). Conceptualising OEP: A review of theoretical and empirical literature in open educational practices. Open Praxis, 10(2), 127–143. 10.5944/openpraxis.10.2.825

- de los Arcos, B. Cannell, P., & McIlwhan, R. (2016). Awareness of open educational resources (OER) and open educational practices (OEP) in Scottish Higher education institutions survey results: Interim report. https://www.slideshare.net/OEPScotland/awareness-of-oer-and-oep-in-scottish-higher-education-institutions-survey-results

- de los Arcos, B., Farrow, R., Perryman, L.-A., Pitt, R., & Weller, M. (2014). OER evidence report 2013-2014. OER Research Hub. http://oro.open.ac.uk/41866/

- eCampusOntario. (n.d.). Open textbook initiative. https://www.ecampusontario.ca/open-textbook-funding/

- Farrow, R., Pitt, B., & Weller, M. (in press). Open textbooks as an innovation route for open science pedagogy. Engaging with Open Science in Learning and Teaching.

- Green, C. (2014). Open education: The moral, business & policy case for OER. https://www.slideshare.net/cgreen/updated-keynote-slides-october-2014

- Hegarty, B. (2015). Attributes of open pedagogy: A model for using open educational resources. Educational Technology, 3–13. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/ca/Ed_Tech_Hegarty_2015_article_attributes_of_open_pedagogy.pdf

- Hendricks, C., Reinsberg, S. A., & Rieger, G. W. (2017). The adoption of an open textbook in a large physics course: An analysis of cost, outcomes, use and perceptions. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning,18(4). 10.19173/irrodl.v18i4.3006

- Hewlett Foundation. (n.d.). Open educational resources. William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. https://hewlett.org/strategy/open-educational-resources/

- Higher Education Policy Institute. (2019, January 29). New data show complexities around casualisation. https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2019/01/29/new-data-shows-complexities-around-casualisation/

- Hilton, J. (2019). Open educational resources, student efficacy, and user perceptions: A synthesis of research published between 2015 and 2018. Education Technology Research Development. 10.1007/s11423-019-09700-4

- The Institute for College Access and Success. (2019). Student debt and the class of 2018. The Institute for College Access and Success. https://ticas.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/classof2018.pdf

- Iuzzini, J., Ayres, T., Dulaney, C., & Daly, U. (2017). Essential role of adjuncts in OER adoption and degrees. https://www.slideshare.net/UnaDaly/essential-role-of-adjuncts-role-of-adjuncts-in-oer-adoption-and-degrees

- Jhangiani, R., Dastur, F. N., Le Grand, R., & Penner, K. (2018). As good or better than commerical textbooks: Students’ perceptions and outcomes from using open digital and open print textbooks. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 9 (1).10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2018.1.5

- Jhangiani, R. S., & Jhangiani, S. (2017). Investigating the perceptions, use, and impact of open textbooks: A survey of post-secondary students in British Columbia. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(4), 172–192. 10.19173/irrodl.v18i4.3012

- Jhangiani, R. S., Pitt, R., Hendricks, C., Key. J., & Lalonde, C. (2016). Exploring faculty use of open educational resources at British Columbia post-secondary institutions (BCcampus Research Report). BCcampus. https://bccampus.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/BCFacultyUseOfOER_final.pdf

- Jimes, C., Weiss, S., & Keep, R. (2013). Addressing the local in localization: A case study of open textbook adoption by three South African teachers. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 17 (2).10.24059/olj.v17i2.359

- JISC. (n.d.). Open education: Enabling free and open access to learning and teaching resources licensed in ways that permit reuse and repurposing in the UK and worldwide. https://www.jisc.ac.uk/rd/projects/open-education

- Kernohan, D., & Rolfe, V. (2017, December 8). Opening textbooks. Wonkhe. https://wonkhe.com/blogs/textbooks-a-tipping-point/

- Lalonde, C. (2017, February 4). Does open pedagogy require OER? EdTech. http://clintlalonde.net/2017/02/04/does-open-pedagogy-require-oer/

- McGill, L., Falconer, I., Littlejohn, A., & Beetham, H. (2013). JISC/HE Academy OER Programme: Phase 3 Synthesis and Evaluation Report. JISC. https://oersynth.pbworks.com/w/page/59707964/ukoer3FinalSynthesisReport

- Nascimbeni, F., & Burgos, D. (2016). In search for the open educator: Proposal of a definition and a framework to increase openness adoption among university educators. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(6), 1–17. 10.19173/irrodl.v17i6.2736

- Nascimbeni, F., Burgos, D., Campbell, L. M., & Tabacco, A. (2018). Institutional mapping of open educational practices beyond use of open educational resources. Distance Education, 39(4), 511–527. 10.1080/01587919.2018.1520040

- National Union of Students. (2012, September 27). 81 per cent of students want textbooks included in tuition fees. NUS News. https://www.nus.org.uk/en/news/81-per-cent-of-students-want-textbooks-included-in-tuition-fees/

- Office for Students. (2018). Value for money: The student perspective. https://studentsunionresearch.files.wordpress.com/2018/03/value-for-money-the-student-perspective-final-final-final.pdf

- Open Education Group. (n.d.). The COUP framework. https://openedgroup.org/coup

- Packham, A., & Hall, R. (2019, July 15). Students struggle to support themselves as university rent costs rise. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2019/jul/15/students-struggle-to-support-themselves-as-university-rent-costs-rise

- Pitt, R. (2015). Mainstreaming of open textbooks: Educator perspectives on the impact of OpenStax College Open Textbooks. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(4), 133–155. 10.19173/irrodl.v16i4.2381

- Pitt, R., & Beckett, M. (2014, July 4). Siyavula Educator Survey Results: Impact of using Siyavula (Part IV). OER Hub. http://oerhub.net/collaboration-2/siyavula-educator-survey-results-impact-of-using-siyavula-part-iv/

- Pitt, R., Farrow, R., Jordan, K., de los Arcos, B., Weller, M., Kernohan, D., & Rolfe, V. (2019). The UK Open Textbook Report 2019. The Open University. http://ukopentextbooks.org/uk-open-textbooks/uk-open-textbooks-report/

- Rolfe, V. (2018). Student expectations and perceptions of university textbooks: Is there a role for open textbooks? figshare. 10.6084/m9.figshare.6062948.v1

- Rolfe, V., & Pitt, B. (2018). Open textbooks: An untapped opportunity for universities, colleges and schools. Insights, 31(30). 10.1629/uksg.427

- Ross, H., Hendricks, C., & Mowat, V. (2018). Open textbooks in an introductory sociology course in Canada: Student views and completion rates. Open Praxis, 10(4), 393–403. 10.5944/openpraxis.10.4.892

- Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition. (n.d.). The Affordable College Textbook Act. https://sparcopen.org/our-work/affordable-college-textbook-act/

- Seaman, J. E., & Seaman, J. (2017). Opening the textbook: Educational resources in U.S. higher education, 2017. Babson Survey Research Group. https://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/openingthetextbook2017.pdf

- Seaman, J. E., & Seaman, J. (2018). Opening the textbook: Educational resources in U.S. Higher Education, 2018. Babson Survey Research Group. https://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/freeingthetextbook2018.pdf

- Stokes, P., & Martin, L. (2008). Reading lists: A study of tutor and student perceptions, expectations and realities. Studies in Higher Education, 33(2), 113–125. 10.1080/03075070801915874

- Universities and Colleges Admissions Service. (2020). Undergraduate tuition fees and student loans. https://www.ucas.com/finance/undergraduate-tuition-fees-and-student-loans

- University of Essex. (2016, March 18). £630 per student: The cost of paper textbooks. https://online.essex.ac.uk/blog/630-per-student-the-cost-of-paper-textbooks/

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Timeline of tuition fees in the United Kingdom. Retrieved April 3, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_tuition_fees_in_the_United_Kingdom

- Wiley, D. (2013, October 21). What is open pedagogy? Iterating toward Openness: Pragmatism before Zeal. https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/2975

- Wiley, D. (2014, March 5). The access compromise and the 5th R. Iterating toward Openness: Pragmatism before Zeal. https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/3221

- Wiley, D. (2017, February 23). Quick thoughts on open pedagogy. Iterating toward Openness: Pragmatism before Zeal. https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/4921

- Wiley, D., & Hilton, J. (2018). Defining OER-enabled pedagogy. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(4), 133–147. 10.19173/irrodl.v19i4.3601