Abstract

Online postgraduate courses for professionals often use discussion forums to promote engagement and interaction. Equivalency theorem suggests that student-student interaction may increase satisfaction but is not necessary for achieving desired learning outcomes. Therefore, costs, as well as benefits, should be ascertained. We used data from student feedback and interviews to assess the perceptions of part-time postgraduate distance learners, and analyze their views of the role, benefits, and drawbacks of discussion forums. The aim was to assess forum efficacy in the context of the specific needs of these learners, to inform forum use and design. Thematic analysis revealed complex interactions between student context and experience, forum design and management. Structurally tweaking forums to control engagement may be particularly ineffective, stimulating unhelpful grade-focused participation and highlighting forum opportunity costs. The study revealed the importance of designing and managing forums, with direct reference to their costs and benefits for specific student groups.

Introduction

Distance learning (DL) has rapidly expanded in the higher education sector (Wang et al., Citation2019), and is selected by students looking for flexibility, convenience, and rapid access to learning materials (Harris & Martin, Citation2012; Mashithoh et al., Citation2014). Technological developments mean that DL can offer multiple advanced, interactive teaching and learning options, overcoming some of the historical stigma associated with this medium (J. L. Moore et al., Citation2011).

Discussion forums have been recognized as an important tool to enable student-student interaction in asynchronous online DL (Ghosh & Kleinberg, Citation2013). Given that such interactions are likely to have costs (time costs, opportunity costs, and financial costs) as well as benefits for educators and students, it is important that their design and application are optimized to maximize student gain and satisfaction. Achieving such optimization entails a good awareness of the requirements and constraints likely to face students undertaking particular types (e.g., online, part-time DL) and levels (e.g., postgraduate) of education. In this context, the research questions addressed by this study were:

How do students undertaking postgraduate-level part-time online courses perceive forums, their role, benefits, and costs?

How can the student costs of forum engagement be minimized, and the benefits be maximized, through improved forum design and management?

The study presented here applied a grounded theory approach to the analysis of qualitative data, in which analysis aims to reveal themes in the data, rather than applying pre-determined themes to them. This article is structured in line with this approach: a brief literature review provides an overview of the study topic, with further exploration of previous work presented alongside the findings in the Results and discussion section.

Literature review

Background

This brief review of the literature focuses on three aspects relevant to the research questions described:

• the importance of student-student interactions to learning

• how learners view student-student interactions

• online forums and their roles.

The aspects detailed above define the theory and experience around the use of student-student interactions to promote learning and boost student satisfaction. They also highlight how learners can find such interactions challenging and consider how forums take on the role of providing student-student interaction in non-synchronous online courses, identifying some of the challenges to this role and the approaches that have been explored to enhance it.

The importance of student-student interactions to learning

It has been shown that effective learning is associated with three student interaction areas: student-student, student-instructor, and student-content (Bernard et al., Citation2009; M. G. Moore, Citation1989). In online learning, interpersonal interactions pose particular challenges, as students are geographically remote from each other and from educators. Overcoming these issues is essential in light of constructivist theories of education, which focus on learning as a communal and collaborative process (Mehall, Citation2020; Parker, Citation1999).

Despite the perceived importance of interpersonal interactions in DL courses, interaction equivalency (EQuiv) theorem suggests that by providing a high level of one of the three forms of interaction, courses can achieve good learning outcomes without the need for the other forms. Therefore, the provision of multiple forms of interaction, while improving student satisfaction, may not be efficient in terms of time and resources (Anderson, Citation2003). According to this theory, if DL courses are able to provide student-instructor and/or student-content interactions effectively, student-student interactions are not necessarily required for positive learning outcomes. Against this, even if the EQuiv theorem is accepted, the provision of multiple forms of interaction may still be justified, given that increasing student satisfaction remains an important goal for DL programs, in which attrition rates can be considerably higher (around 10%–20%) than for traditional higher education (Hobson & Puruhito, Citation2018). This high rate of attrition is caused by a combination of internal student factors (such as self-efficacy, self-determination, autonomy, and time management) and external factors, including family constraints, organizational, and technical support (Street, Citation2010). As a result, including student-student interactions in online courses is often used to engage students more effectively in learning.

Although student-teacher and student-student interaction can occur either synchronously (e.g., video conferencing) or asynchronously (e.g., emails, discussion boards) (Abrami et al., Citation2012), they require purposeful application to give positive educational outcomes (Kirschner & Erkens, Citation2013). Borokhovski et al. (Citation2012) showed that student-student interaction improved most in situations when the treatment was designed specifically for facilitating collaboration between students, rather than treatments that provided the means for student interaction, but not the framework for meaningful collaboration. Establishing pedagogical interventions, which elevate student interaction to a state of collaboration, allowing peer-to-peer learning is an essential strategy for increasing positive student outcomes (Borokhovski et al., Citation2016). These interventions are varied and include actions such as student-student peer review and mentorship (Madland & Richards, Citation2016), and the use of online discussion forums (Koskey & Benson, Citation2017).

How learners view student-student interactions

From a student’s perspective, while learners may often accept the premise that student-student interaction can enhance learning, there is variation in their perception of the value of collaboration despite the pedagogical imperative (Hamann et al., Citation2012; Ward et al., Citation2010). Research has highlighted that some distance learners demonstrate a stronger preference for lone working over collaboration (Lambert & Fisher, Citation2013; Martin & Bolliger, Citation2018) and can find forced interactions challenging, such as when discussion forums are assessed (Birch, Citation2004; Hamann et al., Citation2012). Other studies have found that student satisfaction with interactions is mediated by the quality and speed of feedback and the amount of interaction with instructors, the ease of use and availability of necessary technology, and the amount of student-student interactivity (Bolliger & Martindale, Citation2004; Sher, Citation2009; Wang et al., Citation2019).

These relationships between student satisfaction with interactions and the characteristics of such interactions highlight student costs relating to forums and other interactive approaches. Miyazoe and Anderson (Citation2013) identified invisible costs for students around the addition of different forms of interaction to online teaching programs. These could be direct time costs for students or opportunity costs relating to other academic tasks or wider professional or personal commitments that students could otherwise spend their time on. Such costs are considered invisible in comparison to visible costs, which refer to the monetary price paid by students or borne by institutions providing an activity.

Online forums and their roles

Discussion forums are particularly widely used as asynchronous learning tools in online and blended courses (Ghosh & Kleinberg, Citation2013), introducing student-student interaction. In the specific case of online-only modules, forums can foster the engagement and interactivity that would occur naturally in in-person settings, while providing an opportunity for assessment (Anderson, Citation2003). The social aspect of asynchronous forums provides a flexible, anytime platform for communication, which can improve the potential for student-student interaction (Koskey & Benson, Citation2017), and manage the effect of isolation or lack of motivation reported by DL students (Adraoui et al., Citation2017).

Forums can also encourage conversational or collaborative learning (Dommett, Citation2019), promote Bloom’s higher levels of learning (analyzing and evaluating), and stimulate critical thinking (Laurillard, Citation2013). Furthermore, Lewis (Citation2002) suggests that to be truly effective, forums must reach a certain intensity, with a significant level of commitment from participants required for effective learning.

The main function of discussion forums can vary depending on the context in which they are employed. In the case of massive open online courses, they are almost exclusively used as collaborative spaces, where students assist each other in the teaching and learning process (Sharif & Magrill, Citation2015). Forums can also be used for summative assessment for undergraduate and postgraduate courses. This may add variety to the student’s tasks, feeding into motivation and the development of more diverse writing skills (Nunes et al., Citation2015). Assessment of forums has been shown to increase student engagement, positively affecting the depth of discussion and outcomes in terms of marks awarded (Alzahrani, Citation2017; Beuchot & Bullen, Citation2005; Shaw, Citation2012). Assessment can also incentivize engagement with the marking criteria, which is considered essential to productive discussions (Mokoena, Citation2013; Rovai, Citation2007; Scherer Bassani, Citation2011). Conversely, assessment of forums may adversely modify student motives for engagement (Palmer et al., Citation2008)—learners’ perceptions of discussion forums as an assessment tool can affect both their motivation to engage and, subsequently, their learning outcomes. The variation in students’ perceptions of assessed discussion forums depends upon factors described by Gerbic (Citation2006) as environmental, curriculum, and student, and by Jahnke (Citation2010) as emotional, social, and intellectual.

The review of literature presented highlights that, while student-student interactions in online forums can provide a range of pedagogical benefits and theoretically increase student satisfaction, such forums also carry costs, for students and teaching staff, in terms of time and opportunity cost. Meanwhile, Anderson’s (Citation2003) EQuiv theorem suggests that student-student interactions may not always be necessary in terms of improving learning outcomes. Further, the needs, challenges and perspectives of students are likely to vary, so that one group might perceive some approaches as more beneficial than another group. The study presented here explored these issues by addressing the two research questions defined above for students undertaking online, part-time postgraduate-level courses provided by two universities in Wales (United Kingdom).

Methods

The assessed forums studied are provided within postgraduate DL modules delivered by teaching teams at Aberystwyth and Bangor Universities since 2012. The modules cover agriculture and environmental topics and are aimed at professionals in the agri-food sector in Wales. Modules can be taken individually, or students can undertake multiple modules to attain a postgraduate certificate, diploma, or master’s qualification. The modules are accredited at postgraduate level by the universities. In line with the focus on the Welsh agri-food sector, individuals without an undergraduate degree but with 2 or more years of experience in a relevant professional role are able to join. Demographic data collected on the student population for reporting purposes showed that 42% of students were male and 58% female, with 92% holding a previous qualification at degree level or above. Ages ranged from 22 to 73 with an average age of 41.

A database of 5 years (2015–2020) of feedback from students undertaking the courses described above at Aberystwyth and Bangor Universities was examined, in order to analyze the extent to which students valued assessed forums, and the nature of such value. The database is a repository of anonymous feedback, which all students are invited to provide on completion of a module, using a survey link. Students receive the link in the final week of study, via the learning platform and email. The database provided both quantitative (multiple-choice responses) and qualitative (free text responses) data which included students’ experience of the assessed forums. Over the 5-year period, there were 291 enrollments on modules where forums were part of the assessment; they returned 193 module feedback surveys, representing all modules and years, which were included in this study.

Multiple-choice answers relating to students’ experience of forums were assessed to give an overview of forum performance in terms of the aims defined by teaching staff. These answers were responses to questions, which asked respondents to agree, disagree, or state they had no view, on whether the forums were a positive part of the (learning) experience; helped them feel connected to other students; were well structured; and taught them a lot about the subjects covered.

Free-text responses within the feedback database related to three questions, asking the students to comment on the most enjoyable and least enjoyable aspects of studying the module, and any additional thoughts/experiences relating to the modules. A manual search of the responses identified any answers that explicitly mentioned forums. A grounded theory approach (Bryant & Charmaz, Citation2007) was used in a thematic analysis of these data (Ritchie et al., Citation2014)—that is, data were coded line by line to reveal themes in the responses, using constant comparison between themes and data to ensure the former stayed grounded in the latter. This approach avoids forcing data into predefined themes. The literature is reviewed following (rather than before) analysis to explore how the findings of a particular study fit into (and/or add to) previous findings and theory. Emerging themes from the survey analysis were explored and enriched using five semi-structured one-to-one interviews (Appendix A) with past and current students. Interviewees were recruited from students who attended a discussion convened in 2020 to evaluate the whole program, and from a list of students who had indicated that they were willing to be contacted for further information on their module feedback form. The ratio of female to male interviewees (3:2) reflected the figures for the student population, and those recruited ensured a sample with experience of engaging in forums, across multiple modules, in different years, within the study period.

The interviews took place in 2020 via online video calls. They lasted between 30 and 40 minutes and were analyzed in the same way as the survey responses. Gathering data using two methods (survey and interview) allowed the triangulation of findings, with the aim of increasing the robustness of the study (Noble & Heale, Citation2019). Identified themes reached saturation (no new themes emerging from additional survey responses or interviews), although particular aspects of some themes and interactions require further investigation.

The study was approved by the Aberystwyth University Ethics Committee to ensure good practice. The course feedback survey was anonymous (although students could choose to leave their name if they wished to be contacted). However, respondents were asked if they consented to the wider use and analysis of their feedback. The safeguards of anonymity, and of this consent, were deemed sufficient, given the nature of the topic, and the way data were used in the study. Interviewees read and signed a consent form, prior to the interviews taking place, stating that they were happy for their answers to be used anonymously for this research. The interviewer reiterated and confirmed this consent verbally immediately before starting the interviews.

Results and discussion

Forum aims and development

The aim of the forums, as described by staff interviewed, was to stimulate student-student interaction in debates around module topics. Forum assessment aimed to ensure engagement, providing students with an incentive to be active in discussions and to post well-referenced, considered contributions.

The teaching teams at Aberystwyth and Bangor Universities have used forums since 2012 (see Appendix B for details of forum development). During this time, marking criteria have been altered three times, adjusting a rigid rubric, shifting to a more flexible set of criteria, and finally defining a 75%/25% split between marks available for content and interaction (this version of the marking criteria can be found in Appendix C). Assessed forums were introduced in 2013, with one forum (available for 9 days) provided for each of the nine module units. Later in 2013, in response to student feedback, Aberystwyth University shifted to a block release system, with assessed forums made available over three to four units (weeks) for each of three module blocks. Bangor University retained the one forum per unit model.

Forum performance

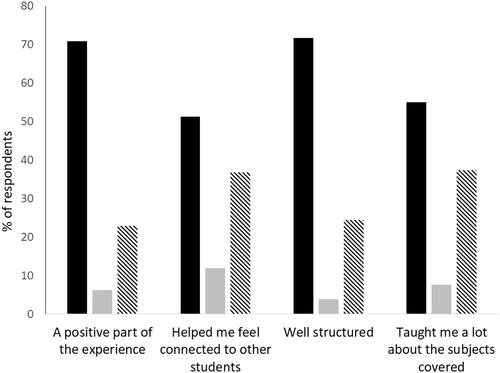

Analysis of multiple-choice questions included in student feedback forms showed () that over 70% of the 193 respondents believed that the forums were well structured and a positive part of the [module] experience, with around 30% neither, agreeing or disagreeing, or actively disagreeing with the statements in each case. Only 51% and 55% respectively felt that they helped them feel connected to other students or taught them a lot about the subjects covered—though only 12% and 8% of respondents indicated that they disagreed with the statements on connectivity and teaching value.

Figure 1. Student responses to multiple choice feedback questions about their experience of the forums: the percentage of 193 respondents who agreed with each statement (black), disagreed with each statement (grey), or neither agreed or disagreed (diagonal stripes).

Findings are comparable with Birch’s (Citation2004) online forum study, which found that a third of students felt negatively about forums at the outset and retained these feelings at the end of the course. That a substantial minority of students did not actively agree that the forums are a positive part of the course, or that they met two key intended purposes (student-student interaction and learning about the topic), suggests that the forums are not performing ideally in terms of benefits to students (Research Question 1). This applies to both increasing student satisfaction and meeting the aims of educators.

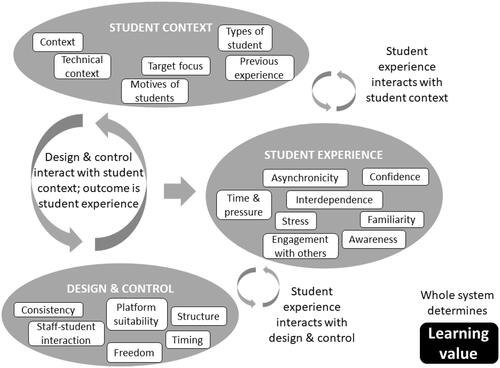

Thematic analysis

Analysis of the open-text questionnaire responses identified 68 responses relating to forums, and the content of these responses grouped into seven themes. Analysis of the five semi-structured interview transcripts revealed a total of 21 themes (see Appendix 4), including developments of the seven themes arising from the questionnaire response data. These themes grouped into three underlying categories (student context, design and control, and student experience) described below in relation to Research Question 1 (How do students undertaking postgraduate level part-time online courses perceive forums, their role, benefits, and costs?).

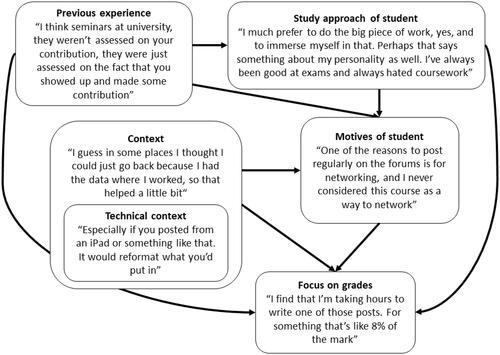

Student context

Key parameters that seem to influence student engagement in forums include their current situation, previous experience, and personality and outlook (). These factors influenced the perception of forums and of whether the time and opportunity costs of engagement were balanced by perceived benefits. Some viewed their experience of forums through the lens of previous live interactions on traditional courses or virtual interactions on other online modules.

Figure 2. Themes within the category of student context and (in quotation marks) examples of interview and feedback responses representative of each.

Other responses suggested that differences in perceptions of forums sometimes arose from personality rather than from forum design, consistent with previous findings (Chen & Caropreso, Citation2004): “Not the setup or anything, or the format. I found it very difficult, just having to read around other people’s interests and things like that”. Previous studies have recognized the importance of personality to perceptions of online forums; for example, Chen and Caropreso found that learners with low scores for extroversion, agreeableness, and openness tended to contribute one-way posts less conducive to discussion. The influence of personality types may be modified by prior experience (Menchaca & Bekele, Citation2008), the prior existence of peer relationships or community, group size (Kim, Citation2013), and other psychosocial barriers (S.S. Ho & McLeod, Citation2008).

Students also had a range of motives for taking online modules, from professional development, to improving job chances, to general interest, and these differences in background sometimes affected their perspective on whether the benefits of forums were important to them. For example, while some often saw interaction as valuable, some also viewed it as time-consuming for the proportion of marks gained—engagement was pleasant but their focus was on outcomes (grades). In this, student views reflected existing literature on the influence of goals on perceived value (Birch, Citation2004).

In line with previous research into online learning (Street, Citation2010), the pressure of work and home life, manifesting itself as a concern about time, was an important topic, although alignment of module topics with work eased engagement for some. Responses indicated expectations that learning should fit around other commitments, rather than vice versa:

It helps when you have a longer period to be able to put your postings in because you can then fit it around your life. At the end of the day a lot of people doing this, the learning is secondary to their main work life.

These results highlight the importance of invisible (time) costs (Miyazoe & Anderson, Citation2013) to time-poor DL students on part-time, online postgraduate courses, who have to juggle studies with professional and personal activities (Rizvi et al., Citation2019). Although DL provides flexibility, allowing courses to be undertaken alongside existing professional and family commitments, previous work has shown that this flexibility and accessibility can come at the cost of reduced cohort interaction and institutional support (Markova et al., Citation2017).

A final aspect of student context related to the forum in the context of the wider teaching module. In particular, students who were pressed for time or focused on outcomes had a negative view of forums that forced them to read on topics away from those covered in other assignments or at a tangent to the module as a whole, for example:

I was posting, I just listened to this webinar or read this newspaper article, but I was a bit worried that was taking my focus away from the more specialist reading in the core unit, if that makes sense.

The comments associated with student experience highlight the invisible costs (Miyazoe & Anderson, Citation2013) associated with adding different forms of interaction into online teaching programs. The context of students’ personality, previous experience, and current situation shapes these costs, as do students’ motivations for taking the course. Professionals undertaking postgraduate level learning are likely to have a clear idea of what they want to achieve (the benefits they require and those they do not) and are perhaps less likely, than undergraduates may be, to feel that they need to work on generic skills such as networking.

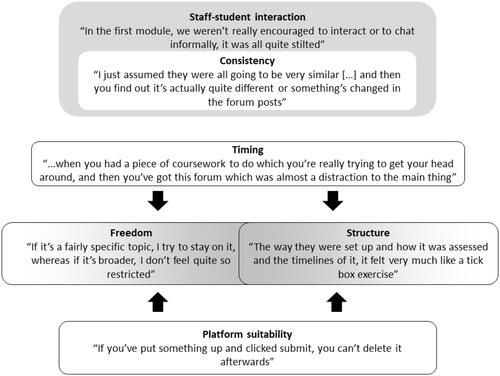

Design and control

Association to forum design and control linked many student comments (). There was a continuum of levels of control over the forum, from tight structure and detailed instructions, through to increasing freedom for students to engage when and how they wanted to. Negative views were associated with both extremes (over-detailed structural rules curtailing engagement, or the stifling of discussion by over-long posts when word counts were not imposed). Between those extremes, some students commented favorably on a shift from weekly forum deadlines to forums open for a whole block of (three or four) weekly module units, while at the same time there were positive comments on the inclusion of a question to focus forum discussion (rather than an open forum on a given topic). These responses indicate the need to maintain a balance between structure and freedom across aspects such as forum length, question type (general to narrow), post criteria (length, rules around referencing, etc.) and requirements for interaction. Students viewed the present form of the forums favorably in terms of their length and post size limitations, for example:

Figure 3. Themes within the category of design and control and (in quotation marks) examples of the interview and feedback responses representative of each.

I think 150–200 words is a really good word limit. In the beginning, I was on some modules that were going for 250-300 and that was more like little mini abstract if you know what I mean. It didn’t encourage postings.

However, more mixed views were expressed about question focus and referencing rules, for example:

I think the referencing side of things makes it difficult because you have to think well, have I referenced this right? Sometimes you may have picked up something either from a lecture or maybe you don’t necessarily remember where you got it from, just through some of the reading, and then having to go back and do a Google search something that you’ve said to find out where it came up. Things like that can take time as well then.

Beyond forum structure and management, issues with the platform hosting the forums created a simple and practical limitation on the freedom of engagement, as did the timing of the forums relative to other module deadlines.

As highlighted in the literature (Bolliger & Martindale, Citation2004; Sher, Citation2009; Wang et al., Citation2019), interactions between staff and students, including consistency in the approaches of different lecturers, were revealed as important mediators of how the students experienced forum design and control. Although one comment suggested that student cohort, rather than lecturer influence, was most important in determining how forums performed, others highlighted, as more important, the impacts of teacher-student interactions. A focus on structural detail expressed by teaching staff may in some cases move students toward tick-box and grade focused approaches to posting, supporting the finding of Hamann et al. (Citation2012) that forced interaction in assessed forums can be difficult for students:

Sometimes you get up to the 200 [word limit] and I think I did 160 once and they said I hadn’t written enough, but the extra point I wanted to put would have taken me over so I didn’t put it in.

At the other extreme, one student perceived the advice to engage in informal exchanges on the forum as added pressure:

We were being encouraged to post generally and respond to other people’s posts, and I can see that it’s nice to interact with other people when you start to learn a bit more about the places where they work etc., but I found it a bit overwhelming in terms of time.

The responses indicate that forum control and design that is either over-prescriptive or too unfocused can increase perceived student time and opportunity costs, and reduce perceived benefits, as students respectively have to meet multiple criteria or struggle to understand what is asked of them, or how it benefits them. In relation to consistency, some students highlighted the danger of only noticing tweaks to marking criteria or format after receiving assessment feedback. In terms of costs and benefits, detailed rules and instructions, changes to these or a lack of guidance, as well as problems with the learning platform, added to the time and opportunity costs for students as well as negatively altering the quality of engagement.

Student experience

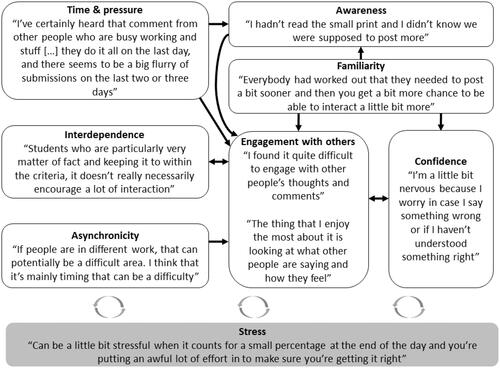

Student experience centers on what actually happened within the forums, rather than comments about their structure or context (). The asynchronous nature of forum posting, arising from the work-life context of engagement, was felt to undermine interaction quality, in line with other studies (McBrien et al., Citation2009; Perveen, Citation2016), as were pressures limiting the time spent on the forums overall. This suggests that, for the students interviewed, the impact of asynchronous use of discussion boards in reducing student feelings of connectivity and collaboration (McBrien et al., Citation2009; Perveen, Citation2016), may outweigh the benefits of asynchronous affordance (the ability to consider and reflect on posts and responses and to consult other sources during discussions) (Jahnke, Citation2010). Affecting engagement, these factors can be associated with the timing, content, and amount of posting by others, which was recognized as key to forum success. Indeed, comments grouped under the themes interdependence and engagement with others suggested that the activity level and approach of others could lead to a successful (or unsuccessful) forum irrespective of the number of students, in line with previous studies which focus on the intensity and frequency of posting as the most important factors underlying learning outcomes (Lewis, Citation2002). Stress or tension was evident as a theme when posting produced conflicts between different motives or concerns. This included a student feeling the need to spend a long time working on posts due to concern about sharing them with other students, while at the same feeling that the reward, in terms of the final grade, was small compared to other uses of their time. These tensions link through to issues of design and control, such as the timing of forum assignments relative to other assessment deadlines.

Figure 4. Themes within the category of student experience and (in quotation marks) examples of interview and feedback responses representative of each.

While marginal in the responses, some students highlighted a lack of awareness of changes in forum structure—for example, in required posts or marking criteria—this sometimes arose from familiarity with previous modules (an expectation of consistency) or from a lack of time. This lack of awareness of structure and expectations could potentially affect forum interactions, while undermining the efficacy of structural tweaks used by educators to improve forum performance.

The role of students already familiar with forum posting was highlighted, echoing Jahnke (Citation2010) who reported students taking up the role of peer mentors during online discussions. However, the relationship between familiarity and confidence was not always positive, as some students described feeling intimidated by high quality posts from others, reflecting previous work suggesting that students can be reluctant to share views on topics they do not feel they have expertise in (Mazzolini & Maddison, Citation2003, Citation2007). Several responses indicated that confidence affected the proactiveness with which students posted, the time taken to post, and the content of posts. The fact that posts stay visible to others (versus the transience of the spoken word) made them more problematic for some. Responses in this category demonstrate that students’ experience of forums and their benefits were affected not only by their own costs of engagement, but also by the time limitations faced by others. Comments indicating emotional costs in terms of stress and the effort of connecting with others highlight that invisible costs relate to effort as well as time.

Synthesis

The categories derived from the data form an interacting system, which determines the perceived costs and benefits of the studied online forums for professional students on postgraduate level courses (). In line with previous literature, the conceptual framework demonstrates that multiple factors affect these forums, reflecting the categories identified by Gerbic (Citation2006) (environmental, student, and curriculum-based influences). In terms of how these factors interacted for professional students on postgraduate-level courses, the data analyzed here highlighted several topics from the literature. Instrumental (grade-focused, ) thinking among students lead them to treat the forums as noticeboards for the posting of considered positions, rather than collaborative knowledge creation. The balance of the different roles of students, with some acting as peer mentors (Jahnke, Citation2010) and others as non-contributing lurkers (due to confidence or information technology issues) (Salmon, Citation2003), can influence forum engagement and perceptions of benefits. Tensions can arise from external commitments, which increase students’ opportunity cost of engagement, perspectives on the benefits of interaction (among cohorts of mature students with experience of more traditional learning environments), and module design and control (Gerbic, Citation2006).

Figure 5. Relationships between categories (grey ovals) and themes (white rectangles) drawn from analysis of data.

The issues revealed suggested a disconnect between, on one hand, teaching staff focused on the pedagogical benefits of interaction considered in constructivist approaches to teaching (Lombardi & McCahill, Citation2004) and the need for students to develop the interactive skills valuable in the modern world, and on the other mature students likely to have gained such skills through professional experience. Such students may appreciate the importance and value of interaction, but not feel that these courses should play the role of providing it. Research to inform teaching for part-time professional students at post-graduate level has previously highlighted their specific needs, especially in terms of their better-defined goals and expectations versus undergraduates (A. Ho & Kember, Citation2018).

The data highlighted how tensions between forum use and student expectations can heighten instrumental approaches to engagement, which may in turn be encouraged by forum assessment (Ottewill, Citation2003) and the focus of educators on forum structure. Adjusting forum structure may be the easiest option for educators to improve performance (e.g., rules on interaction and referencing). However, professional students taking online courses at post-graduate level, have expectations of flexibility and freedom in learning, alongside preexisting professional skills, which may jar with such micromanagement. Through the lens of the EQuiv theorem (Anderson, Citation2003), the invisible costs of student-student interaction in discussion forums are numerous and include emotional costs and effort, not just time and opportunity costs. Time-poor postgraduate distance learners feel these costs more keenly, while the focus of many on content and/or achieving academic grades means that they often do not value student-student interactions highly. Authors have noted that the accessibility of open educational resources and informal learning opportunities online means that the costs of additional forms of interaction (represented here by discussion forums) may fall on students, institutions, or both (Miyazoe & Anderson, Citation2013). Educators considering adding forms of interaction to their course (e.g., student-student interaction within a discussion forum) must take into account the trade-off between the value of student satisfaction provided by such interactions, and the described costs faced by staff and students in delivering and engaging with it.

Insights for forum improvement

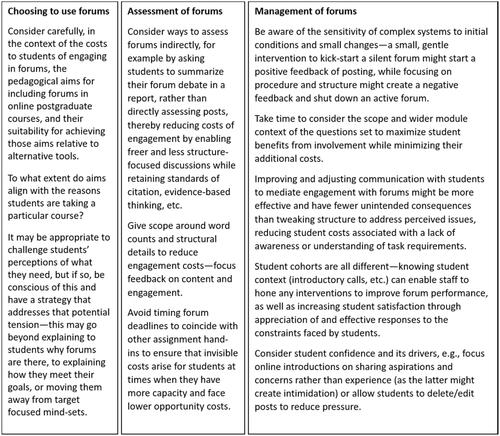

In relation to Research Question 2 (How can the student costs of forum engagement be minimized, and the benefits be maximized through improved forum design and management?) lessons for the use of forums for students on postgraduate level online courses can be drawn from the analysis presented (). These lessons focus on forum design and control, as the category on which teaching staff have power to act directly.

Limitations

While the feedback survey provided a large sample of student views to analyze, it was anonymous and therefore prevented further insight in terms of how identified costs and benefits were associated with factors such as student gender, age, and educational background. As the questions were not designed specifically for this study, the open-text responses relating to the best and worst parts of modules could have led to an overly critical overview of the forums studied. However, as the purpose was not to evaluate these forums but to draw out issues associated with this approach to student-student interaction, this limitation may in fact have aided the identification of all issues faced by students. Finally, although the depth of information provided by the five interviews added greatly to the themes identified in the dataset, further interviews would allow for further exploration of the aspects within these themes. Research to explore the themes identified in more depth, to consider their association with specific student demographic groups, and to quantify the prevalence of the themes mapped are important next steps.

In general, more research could further enhance the capacity of teaching staff to design and manage forums when dealing with professional students taking postgraduate-level courses, who have learning requirements, expectations, and skillsets very different from those of undergraduate learners.

Conclusions

Analysis of the views of postgraduate students engaging in forums used for assessment and interaction in online DL, revealed a complex ecosystem of interacting processes and factors. In terms of the first research question (How do students undertaking postgraduate-level part-time online courses perceive forums, their role, benefits, and costs?), postgraduate students undertaking DL courses were found to face high invisible costs—these costs may be emotional or relate to expenditure of effort as well as time. The external commitments of these time-poor students are likely to accentuate such costs, while their professional status and life stage may make the developmental benefits of student-student interactions less relevant to them than to undergraduate students. Forum design and control can ameliorate or heighten these issues. Depending on specific circumstances, improvements in this respect may tip the student cost-benefit balance in favor of retaining the use of forums, given the importance of student satisfaction in a competitive DL environment.

In line with literature on discussion forums in other contexts, the quality and level of engagement in forums, as well as how such engagement was perceived, depended on feedbacks between how the forums were structured, controlled, and timed and their context in terms of the wider commitments and interests of students, their previous experience, personal preferences and outlooks, and their motivations for studying. These factors affect the roles that different students expect course materials to play and, therefore, how they perceive the benefits delivered by forums. In addition, the value of forums for learning can be highly sensitive to small changes in either student context or forum design and control. The interplay of these factors makes the task of choosing how to improve forums challenging.

Research Question 2 asked how the student costs of forum engagement can be minimized and the benefits be maximized through improved forum design and management. The findings presented demonstrate how challenging this task is, highlighting how the learning context of each student will affect what benefits they require and perceive, and which types of cost are most challenging for them. For professional students studying at postgraduate level, who have clear aims for taking a particular course, focus on structure and control (rather than content) in the changes made to forums by staff, and in the interaction between staff and students, may heighten a tendency toward means-to-an-end approaches with negative consequences for student experience and learning.

For discussion forums for professional students, studying at postgraduate level, there is a need for awareness of the balance between the level of control used to focus student engagement and the vital role of freedom for students to shape such interactions in line with the benefits they are looking to gain and the costs to engagement they face. Care in planning the timing of forum contributions and assessments relative to other course tasks and assignments, is essential to preventing the development of a grade-focused approach to forum contributions. The findings also highlight the importance of using staff-student interactions to mediate the design and control of forums to suit the needs of specific groups of students. This suggests that providing one form of interaction may sometimes support, add value to and reduce the student costs associated with engagement in another form of interaction; in terms of the EQuiv theorem, this represents an additional student benefit (beyond increasing student satisfaction) to devoting resources to more than one form of interaction in course design and management.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the students who participated in the interviews and shared their valuable insights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was declared by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Richard P. Kipling

Richard P. Kipling is an ecologist with expertise in sustainable food and farming systems. He was a lecturer in sustainable systems at Aberystwyth University from 2019 to 2022 and is now head of research at the Sustainable Food Trust.

William A. V. Stiles

William A. V. Stiles is a lecturer at Aberystwyth University and has a research background in soil science, biogeochemistry, and ecology. His research looks for ways to reduce the environmental impact of agriculture, to make farming and food production more sustainable.

Micael de Andrade-Lima

Micael de Andrade-Lima is a lecturer in food innovation at the Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich and an associate fellow of the Higher Education Academy. His main research interests include the extraction and purification of valuable biomolecules from food waste, but he also has a passion for learning and teaching-enhancing methodologies.

Neil MacKintosh

Neil MacKintosh is a lecturer in animal science with the IBERS distance learning team at Aberystwyth University and a fellow of the Higher Education Academy. His lecturing focuses on livestock production, food sustainability, and business entrepreneurship. His research has focused around livestock nutrition, livestock disease control, and their financial impacts.

Meirion W. Roberts

Meirion W. Roberts is a physics graduate from Cardiff University and a fellow of the Higher Education Academy. He worked in the food industry and was a food business operator before working as a lecturer in food science for BioInnovation Wales at Aberystwyth University.

Cate L. Williams

Cate L. Williams is a postdoctoral research associate at the Centre of Excellence for Bovine Tuberculosis at Aberystwyth University. Her project focuses on the population genetics of Mycobacterium bovis in Wales and the genetic manipulation of mycobacteria for the functional characterization of single nucleotide polymorphisms.

Peter C. Wootton-Beard

Peter C. Wootton-Beard is a lecturer in agritechnology at Aberystwyth University. He also coordinates postgraduate research and research methods training for the IBERS distance learning team and is a fellow of the Higher Education Academy.

Sarah J. Watson-Jones

Sarah J. Watson-Jones is a lecturer with IBERS distance learning team at Aberystwyth University and a fellow of the Higher Education Academy. She coordinates modules relating to agro-environment, plant science, and behavior change, and is interested in how these topics interrelate in food and farming systems.

References

- Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Bures, E. M., Borokhovski, E., & Tamim, R. M. (2012). Interaction in distance education and online learning: Using evidence and theory to improve practice. In L. Moller & J. B. Huett (Eds.), The next generation of distance education: Unconstrained learning (pp. 49–69). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-1785-9_4

- Adraoui, M., Retbi, A., Idrissi, M. K., & Bennani, S. (2017). Social learning analytics to describe the learners’ interaction in online discussion forum in Moodle. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (pp. 1–6). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITHET.2017.8067817

- Alzahrani, M. G. (2017). The effect of using online discussion forums on students’ learning. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 16(1), 164–176. http://www.tojet.net/articles/v16i1/16115.pdf

- Anderson, T. (2003). Getting the mix right again: An updated and theoretical rationale for interaction. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v4i2.149

- Bernard, R. M., Abrami, P. C., Borokhovski, E., Wade, C. A., Tamim, R. M., Surkes, M. A., & Bethel, E. C. (2009). A meta-analysis of three types of interaction treatments in distance education. Review of Educational Research, 79(3), 1243–1289. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654309333844

- Beuchot, A., & Bullen, M. (2005). Interaction and interpersonality in online discussion forums. Distance Education, 26(1), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910500081285

- Birch, D. (2004). Participation in asynchronous online discussions for student assessment. In J. Wiley & P. Thirkell (Eds.), Marketing Accountabilities and Responsibilities—Proceedings of the 2004 Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference (pp. 1–7). Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy.

- Bolliger, D. U., & Martindale, T. (2004). Key factors for determining student satisfaction in online courses. International Journal on E-Learning, 3(1), 61–67. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/2226/

- Borokhovski, E., Bernard, R. M., Tamim, R. M., Schmid, R. F., & Sokolovskaya, A. (2016). Technology-supported student interaction in post-secondary education: A meta-analysis of designed versus contextual treatments. Computers & Education, 96, 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.11.004

- Borokhovski, E., Tamim, R., Bernard, R. M., Abrami, P. C., & Sokolovskaya, A. (2012). Are contextual and designed student–student interaction treatments equally effective in distance education? Distance Education, 33(3), 311–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2012.723162

- Bryant, A., & Charmaz, K. (Eds.) (2007). The SAGE Handbook of grounded theory. SAGE.

- Chen, S. J., & Caropreso, E. J. (2004). Influence of personality on online discussion. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 3(2), 1–17. http://www.ncolr.org/issues/jiol/v3/n2/influence-of-personality-on-online-discussion.html

- Dommett, E. (2019). Understanding student use of twitter and online forums in higher education. Education and Information Technologies, 24, 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-9776-5

- Gerbic, P. (2006). To post or not to post: Undergraduate student perceptions about participating in online discussions. In L. Markauskaite, P. Goodyear, & P. Reimann (Eds.), Who’s learning? Whose technology?—Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Conference of the Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education (pp. 271–281). Sydney University Press. https://www.ascilite.org/conferences/sydney06/proceeding/html_abstracts/124.html

- Ghosh, A., & Kleinberg, J. (2013). Incentivizing participation in online forums for education. In EC’13—Proceedings of the 14th ACM Conference on Electronic Commerce (pp. 525–542). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2482540.2482587

- Hamann, K., Pollock, P. H., & Wilson, B. M. (2012). Assessing student perceptions of the benefits of discussions in small-group, large-class, and online learning contexts. College Teaching, 60(2), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2011.633407

- Harris, H. S., & Martin W. E. (2012). Student motivations for choosing online classes. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 6(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2012.060211

- Ho, A., & Kember, D. (2018). Motivating the learning of part-time taught-postgraduate students through pedagogy and curriculum design: Are there differences in undergraduate teaching? International Journal of Lifelong Education, 37(3), 315–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2018.1470115

- Ho, S. S., & McLeod, D. M. (2008). Social-psychological influences on opinion expression in face-to-face and computer-mediated communication. Communication Research, 35(2), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650207313159

- Hobson, T. D., & Puruhito, K. K. (2018). Going the distance: Online course performance and motivation of distance learning students. Online Learning, 22(4), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i4.1516

- Jahnke, J. (2010). Student perceptions of the impact of online discussion forum participation on learning outcomes. Journal of Learning Design, 3(2), 27–34. https://doi.org/10.5204/jld.v3i2.48

- Kim, J. (2013). Influence of group size on students’ participation in online discussion forums. Computers & Education, 62, 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.025

- Kirschner, P. A., & Erkens, G. (2013). Toward a framework for CSCL research. Educational Psychologist, 48(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2012.750227

- Koskey, K. L., & Benson, S. N. K. (2017). A review of literature and a model for scaffolding asynchronous student-student interaction in online discussion forums. In P. Vu, S. Fredrickson, & C. Moore (Eds.), Handbook of research on innovative pedagogies and technologies for online learning in higher education (pp. 263–280). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-1851-8

- Lambert, J. L., & Fisher, J. L. (2013). Community of Inquiry Framework: Establishing Community in an Online Course. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 12(1), 1–16. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/153507/

- Laurillard, D. (2013). Re-thinking university teaching: A conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies. Routledge.

- Lewis, B. A. (2002). The effectiveness of discussion forums in on-line learning. Revista Brasileira de Aprendizagem Aberta e a Distância, 1. https://doi.org/10.17143/rbaad.v1i0.112

- Lombardi, J., & McCahill, M. P. (2004). Enabling social dimensions of learning through a persistent, unified, massively multi-user, and self-organizing virtual environment. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Creating, Connecting and Collaborating through Computing (pp. 166–172). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. https://doi.org/10.1109/c5.2004.1314386

- Madland, C., & Richards, G. (2016). Enhancing student-student online interaction: Exploring the study buddy peer review activity. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(3), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v17i3.2179

- Markova, T., Glazkova, I., & Zaborova, E. (2017). Quality issues of online distance learning. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 237, 685–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2017.02.043

- Martin, F., & Bolliger, D. U. (2018). Engagement matters: Student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learning, 22(1), 205–222. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/189535/ https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i1.1092

- Mashithoh, H., Harsasi, M., & Muzammil, M. (2014). Factors affecting student’s decision to choose accounting through distance learning system. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, 3(2), 313–320. http://buscompress.com/uploads/3/4/9/8/34980536/riber_b14-149__313-320_.pdf

- Mazzolini, M., & Maddison, S. (2003). Sage, guide or ghost? The effect of instructor intervention on student participation in online discussion forums. Computers & Education, 40(3), 237–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-1315(02)00129-X

- Mazzolini, M., & Maddison, S. (2007). When to jump in: The role of the instructor in online discussion forums. Computers & Education, 49(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2005.06.011

- McBrien, J. L., Cheng, R., & Jones, P. (2009). Virtual spaces: Employing a synchronous online classroom to facilitate student engagement in online learning. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(3). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v10i3.605

- Mehall, S. (2020). Purposeful interpersonal interaction in online learning: What is it and how is it measured? Online Learning, 24(1), 182–204. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v24i1.2002

- Menchaca, M. P., & Bekele, T. A. (2008). Learner and instructor identified success factors in distance education. Distance Education, 29(3), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910802395771

- Miyazoe, T., & Anderson, T. (2013). Interaction equivalency in an OER, MOOCS and informal learning era. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 13(2), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.5334/2013-09

- Mokoena, S. (2013). Engagement with and participation in online discussion forums. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 12(2), 97–105. http://www.tojet.net/articles/v12i2/1229.pdf

- Moore, J. L., Dickson-Deane, C., & Galyen, K. (2011). E-Learning, online learning, and DL environments: Are they the same? The Internet and Higher Education, 14(2), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.10.001

- Moore, M. G. (1989). Three types of interaction. American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923648909526659

- Noble, H., & Heale, R. (2019). Triangulation in research, with examples. Evidence Based Nursing, 22(3), 67–68. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2019-103145

- Nunes, B. P., Tyler-Jones, M., de Campos, G. H., Siqueira, S. W. M., & Casanova, M. A. (2015). FAT: A real-time (F)orum (A)ssessment (T)ool to assist tutors with discussion forums assessment. In D. Shin (Ed.), Proceedings of the 30th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing (pp. 254–260). Association for Computing Machinery.

- Ottewill, R. M. (2003). What’s wrong with instrumental learning? The case of business and management. Education + Training, 45(4), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910310478111

- Palmer, S., Holt, D., & Bray, S. (2008). Does the discussion help? The impact of a formally assessed online discussion on final student results. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39(5), 847–858. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00780.x

- Parker, A. (1999). Interaction in distance education: The critical conversation. AACE Journal, 1(12), 13–17. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/8117/

- Perveen, A. (2016). Synchronous and asynchronous e-language learning: A case study of virtual University of Pakistan. Open Praxis, 8(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.8.1.212

- Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., McNaughton Nicholls, C., & Ormston, R. (Eds.). (2014). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Rizvi, S., Rienties, B., & Khoja, S. A. (2019). The role of demographics in online learning: A decision tree based approach. Computers & Education, 137, 32–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.04.001

- Rovai, A. P. (2007). Facilitating online discussions effectively. The Internet and Higher Education, 10(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2006.10.001

- Salmon, G. (2003). E-moderating: The key to teaching and learning online. Taylor & Francis.

- Scherer Bassani, P. B. (2011). Interpersonal exchanges in discussion forums: A study of learning communities in distance learning settings. Computers & Education, 56(4), 931–938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.11.009

- Sharif, A., & Magrill, B. (2015). Discussion forums in MOOCs. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 12(1), 119–132. https://www.ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter/article/view/368

- Shaw, R. S. (2012). A study of the relationships among learning styles, participation types, and performance in programming language learning supported by online forums. Computers & Education, 58(1), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.013

- Sher, A. (2009). Assessing the relationship of student-instructor and student-student interaction to student learning and satisfaction in web-based online learning environment. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 8(2), 102–120. http://www.ncolr.org/jiol/issues/pdf/8.2.1.pdf

- Street, H. (2010). Factors influencing a learner’s decision to drop-out or persist in higher education distance learning. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 13(4), 1–5. https://ojdla.com/archive/winter134/street134.pdf

- Wang, W., Peslak, A., Kovacs, P., & Kovalchick, L. (2019). What really matters in online education? Issues in Information Systems, 20(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.48009/1_iis_2019_40-48

- Ward, M. E., Peters, G., & Shelley, K. (2010). Student and faculty perceptions of the quality of online learning experiences. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 11(3), 57–77. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v11i3.867

Appendix A

Semi-structured interview guide

(This was used as a guide by the interviewer to ensure the topics of interest were covered with each interviewee and that interviews were comparable.)

Start with disclaimers and confidentiality statements, then general questions to relax interviewee:

• How long have you been a student with us and/or how many modules have you taken?

• Why did you choose to take these modules?

• What are your motivations for choosing distance learning?

• Did you have any previous experience of higher education?

More specifically about assessed forums…

• What do you think the purpose of the assessed forums is?

• Have the assessed forums you’ve used changed over time, and if so in what ways?

• If not:

• What do you like about the assessed forums?

• What don’t you like about the assessed forums?

• Have you had any challenges or issues around engaging with the forums? (including things external to the course, your other activities, etc. as well as forum design etc. – and/or save the latter for later)

If yes:

• What did you like about the assessed forums before the changes?

• What didn’t you like about the assessed forums before the changes?

• Did you have any challenges or issues around engaging with the forums before the changes? (including things external to the course, your other activities, etc. as well as forum design etc. – and/or save the latter for later)

• Can you describe the differences/changes made to the forums? How have the changes affected the forums from your perspective (focus on likes/dislikes and challenges/issues)

For all (end of split questions):

How did you feel about sharing your views with other students on the forums?

What do you think about the forum questions that are set? What sorts of questions do you feel work better?

Has the style or framing of the question or discussion topic changed? And, if yes, describe… (Do you have a preference? if that hasn’t already become apparent…)

• How have you found the information and assessment criteria for the forums?

• Have the assessment criteria for the forums changed as far as you know? IF YES: How do you feel about any changes in the assessment criteria? How have they affected you

How do you feel about the assessed forums overall?

How do you feel about them relative to the other course material?

• Has your opinion about the purpose of the assessed forums changed over time? And if so, why?

Is there much difference in the way the different tutors approach the forums, or in the information they give you about them?

• How has this affected your engagement (if at all)?

Any last comments/thoughts about forums that we haven’t covered that you’d like to share?

Appendix B

Timeline of module and forum development

2012

• In 2012 the first online distance learning module, Sustainable Grassland Systems, was launched by Aberystwyth and Bangor Universities. Module content was made available in full for 6 months, including a formative forum, without restriction.

2013

• From January 2013, a new batch of modules were released. In order to smooth student engagement over the time available, new modules were released one weekly unit at a time. An assessed forum was made available alongside each unit for 9 days only. Marking criteria were relatively rigid, with posts judged using a matrix covering Quality, Quantity, Relevance and Manner.

• Later in 2013, in response to student feedback, Aberystwyth University shifted to a system in which one assessed forum was made available for each of three blocks of three or four weekly units, providing more flexibility for student engagement, while Bangor University retained the 9-day model of forum timelines.

2014

• In 2014 an annual learning and teaching meeting between Bangor and Aberystwyth was established to ensure approaches to marking were aligned between the institutes.

2016

• As a result of these meetings, in 2016, marking criteria were altered to replace “Manner” with “Interaction” in the matrix, and a 200-word limit for posts was established.

2018

• The matrix marking system was replaced in September 2018 with the adoption of Aberystwyth University’s central teaching marking criteria, to align with modules delivered by other teaching teams and to provide more flexibility in the marking process.

2019

• In September 2019 marking criteria were amended to define a 75%/25% split between content and interaction.

Appendix C

Assessed forum marking criteria 2019–2020

(Prior to 2019, content and interaction were both assessed but were not separately weighted criteria.)