Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, significant focus was placed on the benefits and challenges of online versus traditional face-to-face learning. This paper presents the findings from a project which paints a more complex picture. Differing Perceptions of Quality of Learning, a collaborative project between four United Kingdom universities, investigated student perceptions of teaching and learning during the pandemic. Mixed methods using survey and focus groups to collect data were used. Analysis was conducted on the overall sample, by subject area, and by ethnicity. Findings indicated that the focus in universities should be shifted from the dichotomy of face-to-face or online learning toward flexible and scaffolded modes and approaches that lead to quality learning and progressively help students to move appropriately between lecturer-led learning and independent learning. Implications for the sector include a focus on pedagogical principles and ensuring the quality of any medium and environment used. The priority recommendation is to provide scaffolding for independent distance learning.

Introduction

The pandemic changed the higher education (HE) landscape overnight. Although Nerantzi (Citation2017) reported that the technology and evidence-based pedagogical models and frameworks, as well as the digital technologies, tools, and platforms for online and blended learning had been with us for some time, the vast majority of institutions were campus-based institutions around the globe and their move to fully online provision was experienced as a seismic shift for staff and students and the HE sector as a whole (Stracke et al., Citation2022). Despite these rapid and enormous changes, the transition to HE, as well as studying and graduating, were accomplished notwithstanding multiple challenges. These included particularly accessibility, digital inequality, inclusion, loneliness, well-being, and staff development (Stracke et al., Citation2022). Alongside this, HE institutions have made efforts to become more inclusionary, as evidence suggests that they remain exclusionary by marginalizing students from minoritized ethnicities through White-centered curricula, inadequate student engagement, and support for students from Black and minoritized ethnicities, and insufficiently longstanding equality interventions to change racial discrimination (Arday et al., Citation2022).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, institutions rapidly developed a shift to their learning and teaching provision for 2020–2021. Educators, academic developers, learning technologists, and all those supporting student learning, together with senior leaders and decision-makers, were resourceful and fast in making decisions to transition in most cases to a fully online offer, which became known as “emergency remote teaching” (Bozkurt & Sharma, Citation2020) for at least the first year of the pandemic. Many moved then to blended and hybrid models, a mix of online and face-to-face, synchronous, and asynchronous, learning and teaching, across all their provision for 2021–2022. These curriculum interventions provided increased flexibility and choice to students to fully participate in their program of study (Kukulska-Hulme et al., Citation2022; Turan et al., Citation2022). As a result of the changes implemented, it seems that the use of technology has now been largely normalized, and educators are reported to be more ready than ever before to experiment with digital pedagogies and tools (Association for Learning Technology, Citation2021; College Innovation Network, Citation2022). This journey for students and educators was rather complex: “from the instrumentalisation of technology, to the ontological isolation of the human from its material contexts, to a broadening of those concerns from educational technology to education itself” (Bayne, Citation2015, p. 18).

University students are expected to be or become independent learners. These expectations may be more obvious when students are distance and/or online learners, because online or virtual environments may be less lecturer-led, as reported by Turan et al. (Citation2022). A support scaffold aids this process and helps students build learner competencies and self-efficacy. Kukulska-Hulme et al. (Citation2022) talked about the pedagogy of autonomy and stated:

The pedagogy of autonomy does not mean that students study alone; teacher support plays an important part in developing the necessary skills. The intention is to provide learners with resources, strategies and the confidence to face any difficult situations they may encounter during their learning journey. (Kukulska-Hulme et al., Citation2022, p. 29)

Barnett (Citation2022) talked about students’ loneliness and anxiety as something that is part of HE and acknowledged that students:

As an intelligent person, and having concerns about the world, [feel] the crises of the world and the turbulence of their own lives conspire to heighten natural anxieties about their being as such. And it is a function of a genuine higher education to add to these anxieties. (Barnett, Citation2022, p. 3)

A truly valuable and meaningful experience for students and educators alike, is not one that prioritises belonging to the university, but one that sees the university as an emergent construct growing out of and existing through the interrelationships of those involved in the ecosystems and communities associated with our praxis. (p. 13)

A literature review on evidence-based pedagogical frameworks and models for fully online and blended learning in a range of HE settings and beyond indicated that there are four key features that play a key role in digital learning: facilitator support, choice, activities, and community (Nerantzi, Citation2017). These illustrate clearly that a more holistic, active, and open approach to curriculum design in technology-enabled settings can make a real difference to students’ engagement, active participation, success, well-being, and control of their own learning.

This paper presents the findings of a collaborative project Differing Perceptions of Quality of Learning between four United Kingdom (UK) universities. A mixed methods approach (surveys and semi-structured focus groups) was used to investigate student perceptions of teaching and learning of ethnically diverse first- and second-year undergraduate students in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Internal data analysis at one of the project partner institutions, prior to this project, had shown that students of different ethnicities have differing expectations of HE outcomes. Thus, the project was designed to determine whether students more widely in the HE sector have other differing expectations, related to the pandemic learning experience, which differ by ethnicity.

The intention was that, if differing perceptions of learning by ethnicity were found, through student feedback on their perceptions of the quality of learning, steps could be taken to ensure that blended learning approaches were designed not to adversely affect any groups of students or to increase awarding gaps. The project was also intended to provide mechanisms to identify staff development needs and to support staff to adjust their teaching and engagement with students about learning.

Particularly, the project aimed to answer the following research questions:

How was the students’ experience of learning and teaching during the academic year 2020–2021?

What are students’ teaching and learning expectations for the next academic year?

Are there any statistically significant differences in the answers of students of different ethnicities?

After setting out our methodology, we will present student feedback that indicates mixed emotions related to various elements of learning at a distance that could be termed challenging. We will show that the experience of the 2020–2021 academic year and preferences varied considerably by ethnicity. As we will show, there is not a simple divide between online versus traditional face-to-face learning. We will present potential reasons for such results by exploring factors affecting students' experiences and preferences such as accessibility, resources, and the nature and place of independent learning. We will then discuss how the distance between online and face-to-face learning can be minimized in order to maximize independent learning, followed by some recommendations.

Method

Participation in the research required participants from the four participant universities (the University of Portsmouth, Manchester Metropolitan University, Solent University, and the University of Nottingham) representing different types of institution, to complete a survey questionnaire and/or attend an online focus group. Ethical approval was granted by the University of Portsmouth on May 10, 2021.

Primarily, first-year and second-year undergraduate students of the participating courses in the four universities were invited to participate voluntarily in the project by completing the online questionnaire and attending an online focus group, both of which would allow them to share their perceptions of the quality of learning. Participating courses were from the following three subject areas: Health Sciences, Business, and Other Sciences. The rationale for choosing the particular courses in those subject areas was that they had comparatively good diversity in terms of student ethnic backgrounds, and they could be compared between the participating collaborative partners (this factor was necessary for data comparability purposes). All first- and second-year students on the agreed upon, and common, set of courses could complete the survey and volunteer for the focus groups. A random process was designed to select participants from the pool of volunteers; however, all volunteers were selected to take part in focus groups. Post-hoc analysis showed that the final distribution of participants was representative of the different courses and ethnicities or backgrounds. In order to ensure that the requirements of informed consent were met, the invitation email had a reference link to a dedicated webpage with extensive information regarding the project and a reference link to a data protection statement, in addition to the link to the survey.

Instruments

The survey was designed to complement existing tools in use at the partnership institutions and to collect a demographically stratified sample. Its development took into account existing partner research and evaluation. It probed students’ perceptions of the quality of the learning and teaching they had experienced, drawing on and learning from the internal surveys that had been undertaken by some of the partners and the partners’ students’ unions in recent months. The University of Portsmouth engaged their students and student representatives with a pilot survey to ensure that the survey tool had been appropriately designed to capture the student voice. The pilot test survey was completed by 12 students or student ambassadors from minoritized ethnicities. Their feedback was positive and did not result in major structure or content changes.

The survey comprised 32 core questions covering the following themes: demographic information; teaching and learning, accessibility, engagement and expectations, assessment and feedback, and general questions about learning. Overall, questions examined: the students' learning experience (quality of teaching and quality of learning) during the academic year 2020–2021; what students’ teaching and learning expectations were for 2021–2022; any statistically significant differences in the answers of students of different subject areas; and any statistically significant differences in the answers of students of different ethnicities. The survey was open from May 10 to June 9, 2021.

Nine focus groups and one interview were conducted across the four universities. The intention was to conduct focus groups only, but due to unforeseen circumstances, when some students did not attend one of the focus groups, this resulted in a focus group of one being run and included in the analysis as an interview. We then decided to include the voice of the one student who participated. The focus groups and the interview were semi-structured. They were designed to follow up on the questions and information gathered by the survey. Each focus group lasted 45–60 minutes. The collected data were transcribed by someone external to the project and professionally unrelated to those involved (a sample was checked by the research team for accuracy), fully anonymized, and thematically analyzed in NVivo. Core themes in the main focus group questions were quality teaching, quality learning, teaching methods, background as a resource, independent learning, summative and formative assessment, and key recommendations for next year.

Data analysis and sample

Following the completion of the questionnaires and cleaning of the data, the validity of the survey was checked; then, the questionnaire data were (a) presented to each participating university in summary reports, for an overview of the results; and (b) analyzed using SPSS and Python (quantitative data) and NVivo (qualitative data) by the University of Portsmouth research team for all partners, for a more in-depth analysis and to develop the focus group questions.

The Cronbach's alpha coefficient as an internal consistency reliability assessment tool for each scale was employed. All the values of Cronbach’s alpha were found to be greater than 0.7, showing internal consistency.

The survey sample consisted of 835 undergraduate students (98% first- and second-year students) from the four universities. The sample demographics show a fairly even distribution of the sample regarding gender, first and second year of study, and Black and minority ethnicities (BAME), and White students. Students with home (UK) fee status were significantly greater in number than students with other status. Students self-reported their ethnicity by choosing from a list of 18 ethnicities, which, for the purposes of analysis, were aggregated into six categories. Among the BAME students, 52% were Asian, 24% were Black, 12% were Arab, and 8% were of mixed ethnicity. Asian students were further split into two groups: Chinese and Indian (CHN/IND) and Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and other Asian (BAN/PAK/OTH) students. This was due to the number of students in the Asian category, and based on prior evidence that there tends to be a difference between the two groups of students within that category regarding the proportion of certain degrees that are awarded. Therefore, we wished to investigate if there were other differences between the two groupings, which were large enough for useful analysis and approximately equal in size. Follow-up focus groups were conducted during June 2021 to gain a deeper understanding of the survey results. The survey questionnaire had asked students if they would like to participate in the focus groups. There were 33 focus group participants in total (10 White students, 17 BAME students, and six students who did not disclose their ethnic background; and the participants were divided by subject area as follows: 12 Business Studies students, 10 Health Sciences students, and 11 Other Science students).

Spearman’s rho, chi-square, Kruskal-Wallis, and Dunn’s tests were used, among other statistical tests, depending on the nature of the question, for comparisons of answers to questions between different groups. When testing for significant differences between grouped responder means for question groups, statistical testing was undertaken as follows: the responder means for each question and question group were grouped by ethnicity (or subject area), and each group of means was tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. P values were generally less than 0.05, and there were no questions for which all ethnicity p values were greater than 0.05; therefore, the data was deemed to be non-normally distributed. Bartle's test was also applied to test for homoscedasticity, and where this was confirmed, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Where statistically significant differences were found between medians (of responder means, grouped by ethnicity), Dunn's test was applied—with Bonferroni's correction—to determine which group’s medians were statistically different from each other. The analysis explored correlations between experience, perceptions, and expectations regarding quality of learning and teaching. In addition to thematic analysis, frequencies and correlations were explored by ethnicity and subject area.

Data analysis from the survey and the focus groups highlighted trends for the whole sample overall, by ethnicity, and by subject area. For the purposes of this paper, we will focus on the findings related to distance learning in order to make recommendations for practice. The full project report provides our data collection and analysis in full (Dunbar-Morris et al., Citation2021).

Results

In this section, we will present overarching findings linked to the study and study participants, including demographics and specific findings that provide insights into how (in)dependent learning was perceived through the survey instrument and focus groups. The Differing Perceptions of Quality of Learning survey and follow-up focus groups show considerable difference, and some similarities, in perceptions and experiences between different ethnic groups in the context of the pandemic.

Mutual themes raised for all ethnic groups were the appeal of blended learning; opportunities to engage and interact with others (face-to-face); recorded material; the availability of online resources; the ability to review material at will and the ability to learn at one's own pace; and the convenience, comfort, flexibility, and time economy of online teaching.

Appeal of blended learning

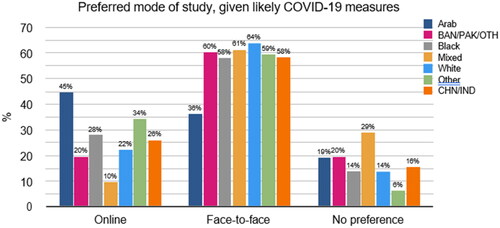

While the majority in all ethnic groups said at the time—when teaching was still largely being carried out online only due to English government regulations—that they preferred face-to-face teaching, the proportions ranged from 64% of White respondents to 58% of both Black and CHN/IND students only. Furthermore, there was not much appetite for online-only learning, with only 22% of White students having a preference for it, dropping to 20% for BAN/PAK/OTH students, and rising only slightly for Chinese and Indian students (26%) and Black students (28%). However, 45% of Arab students preferred online-only studying.

shows the percentage of each ethnicity expressing a preference for each mode of study.

Indeed, students seemed to appreciate the benefits of both of these elements of blended learning if they had been able to access the planned face-to-face aspects:

I liked the mixture of both online and face-to-face. The online saved time in terms of travel to and from university [which is] approx. 2 hours. However, the face-to-face was good for group discussions and having debates. After the pandemic and going forward, it would be beneficial to students and teachers to continue with both teaching methods. (Survey response)

Recorded material

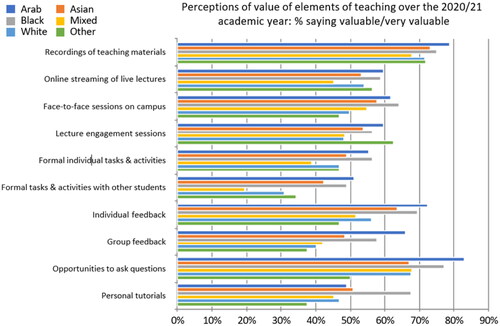

A total of 73% of respondents regarded the recording of teaching materials as the most valuable element of teaching at that time. In addition, they highlighted the importance of engaging with these and other online resources before attending sense-making sessions with peers.

For me it [the key factor of the year] was the huge amount of information and lecture recordings and tasks and quizzes and material for study. The availability of it. It was all online so I could access anything I wanted, whenever I wanted, so it was fairly easy to get access to study materials. (Student S, Black African, Other Sciences, focus group)

Students from all ethnicities mentioned the benefits of recorded material, which allowed them to study at their own pace and review content at will including for revision:

For me personally that [recorded material] was extremely helpful, and to be honest if they didn't do that, I probably wouldn't have made it through first year. People like me and maybe other people who have any type of mental disability, being able to go back and learn things at our own pace and put it on our own schedule is very helpful. (Student H, Black Other, Health Sciences, focus group)

Opportunities to engage with and interact with others

The full report of the findings of our project indicated that during the pandemic students were almost exclusively looking toward their tutor to provide resources and support for their learning and often felt lonely (Dunbar-Morris et al., Citation2021).

Formal tasks and activities with other students were among the aspects of teaching over the 2020–2021 academic year that students felt contributed the least to their experience. This finding is concerning, considering that collaborative group work is a key professional activity. Focus group and open question analysis indicates that the negative view of group work is mainly associated with the difficulty of conducting it remotely and online. The lack of quality interaction resulted in this negative view. For example, students commented on other students not taking part in online discussions and break-out groups. Comments also related to staff who did not use technology and online tools appropriately or creatively, some merely using a tool in order to use the tool rather than to enhance interaction by its use. Examples from students include:

The lecturer didn't really know how to use Zoom. Most people were just talking and stuff and he didn't know how to mute them and stuff like that. So, I feel like if things were going to be online things should have been prepared properly, so that affected the quality of teaching I feel. (Student T, Arab, Other Sciences, focus group)

Right now it is just you watch them on a screen, but you cannot ask questions because it is a video playing. At the end of the day it is as good as watching something on YouTube. If you change that up a little in terms of delivery, I feel like engagement would go up. (Student E, Asian Indian, Business Studies, focus group)

Quality teaching is presented well for all levels […] delivered by tutors who have enthusiasm for the subject and a sound knowledge to engage the learning process. […] delivered in various mediums such as PowerPoint, videos and should contain interactive sections to underpin that understanding has been achieved. There would be opportunities to discuss any part of the subject that has not been understood or that inspires debate. […] there should definitely be elements that both challenge and encourage participants to research and discover the subject outside of the [timetable]. (Student X, ethnicity not known, Health Sciences, focus group)

Availability of online resources

A diversity in responses was reported when students were asked what the university could do in terms of helping them better access the resources they need for their learning. shows the different approaches by ethnicity, when it came to the most frequently mentioned resources.

Table 1. Expressed support requirements regarding resources for learning by ethnicity.

Students from all ethnicities frequently mentioned that the following are crucial: the restructuring of online resources or the virtual learning environment (VLE), to improve clarity and user-friendliness; the need for how-to videos or extra workshops and classes detailing how to access and use online resources (less so for Black students); more, or more easily accessible online resources (except White and Other students). The ethnically diverse students appear to have relied more on resources from educators, while White and Other students were perhaps more confident and more independent in this respect. Additional attention is required, therefore, on scaffolding understanding and building capacity and capabilities to develop their potential for independent learning and developing a personal learning ecology as part of a diverse learning and academic community.

The proportion of all ethnic groups who had the time, space, and resources to engage in independent learning was approximately the same, except for Other students, a lower proportion of whom frequently engaged in independent learning. Arab and Mixed students were the two ethnic groups who most frequently used their university’s online library resources. However, in terms of using the time, space, and resources to engage in independent learning, Mixed students were the least confident of all ethnic groups, while Black students were the most confident. Mixed students were also the least confident using the VLE, and reported not having a reliable and adequate Internet connection. Compared to other ethnic groups, Black students consistently expressed a good degree of confidence using many of the listed resources, especially those related to independent learning, online library resources, the VLE, adequate computing hardware, a microphone or camera. However, they were less confident using the required software. Asian students, while not the least confident in the use of any one resource, were consistently among the least confident ethnic groups for many of the resources. White students most frequently have access to a reliable Internet connection, adequate software, and camera or microphone. Confidence and frequency of use when needed were also explored. Correlations between the two of these variables were reported and such correlations may underline the need for scaffolding once again, for the sake of confidence-building and more frequent use. For most aspects and most ethnicities, correlations between responses to how frequently they used the resource when needed and how confident they were when using the resource were moderate and positive, with a few exceptions. Correlations were also tested between the average scores for expected frequency of online engagement and the average score of expectations having been met for teaching and learning, to see if there was a correlation between expected online engagement and satisfaction with teaching and learning overall. While some weak and moderate correlations do exist, they are far from overwhelming and they do not necessarily imply causation. Practically, this may suggest that students do engage online, regardless of their satisfaction with the quality of teaching and learning, even though the aforementioned correlations about confidence and frequency of use of resources indicates that they may not engage with confidence or with the appropriate use of resources.

Ability to learn at own pace

Another theme in the findings was the relationship between independent learning and quality learning and teaching. When asked to define independent learning, also in relation to what was required during the pandemic, students frequently mentioned the importance of working alone, outside of timetabled classes, and/or revision. Students felt that teaching staff may guide students in their independent learning, recommend credible sources or further reading, or help students with the transition from the way of working in school to that of university. Some of the partner institutions in the project used a flipped pedagogical approach to learning and teaching, which required the students to do some independent work before joining synchronous sense-making sessions with staff. Some of the student feedback highlights dissatisfaction with independent learning, or a misunderstanding of the approach, as well as difficulties in implementation:

This year has been entirely independent learning, more or less, effectively. I feel like in first year especially, it needs to be a lot more guided because in first year […] you are not used to the idea of having to read around the subject, because you do not have to do that in A-level. [At] A-level you can just go into all the lessons and you will be fine. (Student AC, White, Other Sciences, focus group)

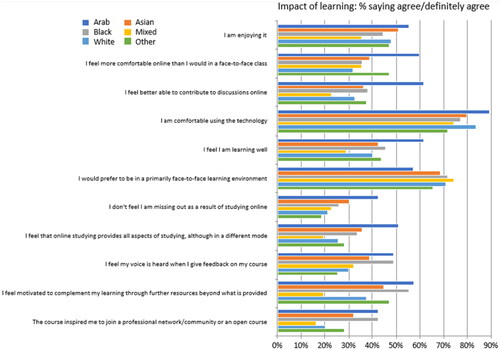

Students’ perceptions of quality of learning differed by ethnicity; however, all ethnicities highlighted elements of pedagogical value. Overall, the results from the survey and focus groups in this project indicated that students from all ethnicities appreciated various benefits of both online and face-to-face teaching, although different ethnicities may have their preferred elements and resources, and varying levels of confidence with learning and use of resources. Furthermore, significant differences in needs for additional support were reported, for example, students from minoritized ethnicities seem to rely more on resources from educators, while White and Other students were more confident and more independent in this respect. Nevertheless, students from all ethnicities appreciated the benefits of recorded material, studying at their own pace, and an enhanced VLE. The findings show mixed student understanding of independent learning, but a strong perception from some students that they did all their studying alone during the pandemic. Students reported a negative view of group work due to lack of quality interaction with distance learning, but there was a general consensus that quality learning should be interactive, both in terms of staff-student interactions and among students.

Discussion

The discussion of findings linked to (in)dependent learning from our collaborative study follows. The section is organized using the four key features that emerged through an earlier review of established and widely used digital conceptual and empirical pedagogic frameworks (Nerantzi, Citation2017): facilitator support, choice, activities, and community. Discussing our findings using these as a scaffold will be a more systematic and evidence-based approach to evaluation. It will help provide new insights based on what the literature suggests to contribute to effective learning and teaching in fully online and blended modes that is relevant in the context of (in)dependent learning, which is the focus of this paper.

Facilitator support: Findings of our study relating to facilitator support strongly suggest that students value, appreciate, and expect the support from educators and recognize how this helps them progress with their studies. While the literature recognizes the important role the facilitator, educator, or personal tutor plays in scaffolding learning and helping students become more confident to engage in the learning process and feel part of a learning community (Armellini et al., Citation2021), we need to be mindful that the facilitator-student relationship does not become a relationship of dependency. It must truly lead to independence and have a positive impact on well-being, while also broadening the learning horizon and possibilities for students (Murray, Citation2014). Our findings particularly indicate that the tutor-student relationship is expected to be extremely strong from a student perspective, at the expense of learning relationships with others, such as peers, friends, and individuals outside the boundaries of the module or course. Black students, for example, attribute the most value to personal tutorials, and part of their characterization of quality teaching is that it provides opportunities to interact with staff. Having said that, the Black students in our study attribute importance to, and report good experience of, all the elements related to learning, including studying with fellow students, discussing academic work with other students, and developing a sense of belonging with peers on the course. Therefore, greater care needs to be taken when designing for learning to take into consideration a wider spectrum of others who can play a vital role and broaden learning relationships that can lead to greater independence and empowerment. The reliance on the facilitator also hinders good pedagogical practice such as co-creation and collaboration between staff and students to co-design the learning experience. We recommend providing support to both staff and students regarding the skills needed for the challenging aspects of learning. Both staff and students need support to develop skills for online engagement, for example. This would include improving the delivery and implementation of remote or online formal group activities and giving students the skills they need to effectively engage with these activities.

Choice: Findings relating to choice suggest that students across all ethnicities welcome the flexibility of online and blended learning as it translates as choice to engage with the resources provided at a time and location that works for the students. Mixed students, among other ethnic groups, in our study characterizse quality teaching as teaching that occurs face-to-face or on campus and is inclusive of all students’ abilities and needs. The asynchronicity of the educational offer enabled by online learning, beyond the synchronous or live engagement, is welcomed by students, and increases their perception of choice. Therefore, choice brings new freedoms in time, pace and place, and also limits in many cases the financial burden of travel, thereby reducing the cost of studying, and enables some students to look after family members and take up work, as we note in our findings. Despite these new opportunities provided by online and blended learning, our findings indicate that the majority of students seemed to miss campus-based teaching and learning. This has been consistently reported during the pandemic (Kukulska-Hulme et al., Citation2022; Turan et al., Citation2022) and seems to be connected to feelings of loneliness and isolation we also reported in our study (Dunbar-Morris et al., Citation2021) and in the literature (Barnett, Citation2022). Mixed students in our study have a particularly negative view of the teaching on their course regarding engagement and sense of belonging among students. However, campus-based provision was not something that could be reinstated by institutions independently due to local and national lockdowns and social distancing measures imposed by the government in the UK and other countries around the world (Stracke et al., Citation2022). Therefore, the mode of study, fully online, blended, or on campus, was not a choice for students, at least for the first year of the pandemic during which this research project was conducted. However, that Arab students especially seemed to prefer studying online, in contrast to a high percentage of White students who prefer face-to-face, is surprising. This is not something we anticipated and should be investigated further in order to gain more conclusive insights for designing pedagogical interventions that are more inclusive and flexible. We see opportunities for choice to be considered pedagogically by educators, more than just giving students the freedom to decide when to study and engage with their course. Building in choice in the context of learning, teaching, and assessment that will enable students to feel more connected to their studies and to others, and to pursue their own interests and aspirations, has benefits. It can increase participation, help students take ownership of their own learning, and therefore become more independent, while also considering learning opportunities that sit outside their module, course, or institution, including accessing open educational resources and participating in open practices, networks, and communities (Stracke et al., Citation2022), which we do not observe to a large extent in our findings. There is a need to harness such opportunities more in the context of any educational offer to widen and diversify learning and teaching and connect education more with local and global communities and society. We recommend enabling the student voice to be heard and also to feed into decision-making about teaching practice by gathering student feedback on distance learning. For example, our open access survey tool can be employed to conduct local research to make decisions about how to offer distance learning to students in a local context. Students can be asked about how we can value their backgrounds in teaching to get their ideas to use in our classrooms and online teaching spaces. These ideas could be gathered anonymously online. Taking including the student voice a step further, students can also be involved in collaborating in the learning design activities or in the co-creation of them.

Activities: Our findings suggest that while students recognize the importance of interactive ways of learning, including learning with peers in groups, they experience real challenges in this area and feel that working with peers is largely problematic especially because of the online mode of learning. They also state that they missed learning with their peers on campus. Interactions and relationships with peers were minimal and often seemed to lead to feelings of loneliness. There is evidence that negative emotions can lead to less learning and engagement, as a recent study has shown (Harkin et al., Citation2022). Some students also noted that they did not have any friends. In our study, feeling isolated, lonely and suffering from lack of interaction with others was raised by Asian, Arab, and Other students. Our findings indicate that students value the resources provided by educators and often want more. Many seem to lack the confidence to use other resources externally. Arab and Mixed students, however, more than students from different ethnicities, did reach out to available online library resources without being prompted. Students use, especially, video recordings in ways that help them learn in a more active way. While video might be seen as a passive way of learning, our findings suggest that students find ways to actively engage with it and complement their learning. Arab students also identify that online course forums work well and create some opportunities for interaction. We know that educators more than ever before engage in digital learning and teaching, and experiment with relevant technologies and tools to create opportunities for more active and activity-based learning in online and blended modes of learning (Association for Learning Technology, Citation2021; College Innovation Network, Citation2022). The pandemic has brought to the forefront digital inequalities and accessibility issues that often became barriers to engagement and learning (Bozkurt & Sharma, Citation2020). These are important areas that need to be investigated carefully, and institutions need to create equitable support systems for all students. Our study indicates that more needs to be done in this area to make learning more active and activity-based for students. There are many pedagogical benefits of working in groups. Using a collaborative framework may be helpful to design group activities that are meaningful, add value, help students learn with their peers in flexible and inclusive ways, and harness the power of collaborative learning that can lead to greater independence. We also recommend providing options during remote lectures for anonymous questions to be asked in the session chat to increase student engagement. In addition, we recommend exploration of the role of students as both users and creators of recorded material. Students, as makers of recordings, is a practical example of authentic, active, collaborative and inquiry-based learning strategies—including problem-based learning. EVOLI, a video tagging tool, for example, may also open up new opportunities for students to engage with video resources in a more focused and interactive way with peers and tutors.

Community: Our findings suggest that there is a lack of community, and a lack of a sense of belonging, among students more generally. Students seem to be engaged in their learning primarily through the resources that were made available to them and targeted interactions with educators. The vast majority of Arab students in our study, for example, think that time spent communicating with academic staff online is important or very important, while both White and Black students also attribute very high importance to this. This seems to have been the nucleus of their learning. This way of learning seems to have created feelings of loneliness and isolation as we report in the findings and is consistent with other studies conducted during the pandemic (e.g., Harkin et al., Citation2022). Personal tutors can be an influencing factor that encourages students to engage with their courses and beyond, and with the community (Armellini et al., Citation2021). While a sense of community and belonging is often discussed, at least in the UK HE context, as something that is important for students, especially in relation to their course and the university, Barnett (Citation2022) reminds us of the need to adopt a wider view on community that is boundary-crossing and links up university and the outside world. Graham and Moir (Citation2022) note that it may be problematic if institutions focus exclusively on creating a sense of community and belonging that is solely inward-facing and ignores the outside world. The inward-facing nature of learning and the lack of a wider community is something that stands out in our findings; notably the findings around the tutor and student relationship, and indeed dependency, at least in some cases, and the lack of interactions with peers and others outside the module, course, or the institution. This indicates a need to rethink curriculum design and to identify opportunities for educators to harness community in more boundary-crossing and lifewide-learning terms (Nerantzi, Citation2017). This also links with our earlier point about scaffolding students to develop a personal learning ecology as part of a diverse learning and academic community. Ensuring that students develop a deeper understanding of wider learning opportunities within more ecological approaches to learning would be beneficial and help them to become progressively more independent. We recommend incorporating the use of external facilitators and mentors and providing opportunities for project work to be undertaken with external input via online mechanisms associated with wider local, regional or global objectives. Educators could also consider connecting with another course or module in another institution in other parts of the world to create opportunities for students to experience collaborative online learning. This could also include encouraging students to use open educational resources and linking up with professional communities linked to their studies.

Conclusions

This paper presents a complex picture of (in)dependent learning which goes beyond simple dichotomies such as online versus traditional face-to-face learning, both of which all students in our study appreciate, although students of different ethnicities have different preferences for which elements and resources they find beneficial, which appear to be based on levels of confidence. Drawing on the results from a mixed methods research project Differing Perceptions of Quality of Learning, which sought to investigate student perceptions of teaching and learning from ethnically diverse undergraduate students in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, we show that the learning experiences in the pandemic vary greatly by ethnicity. In addition, where we find that students do not appreciate elements, this appears to be an indication of fertile ground for scaffolding within the context of independent and distance learning in order for students to better understand the pedagogical value of certain practices and tools and processes, engage adequately, and to benefit from them.

Noting that recorded materials, self-paced study, and an interactive learning environment are found to be of value for all students, the primary recommendation we make is for educators to provide scaffolding for independent distance learning, that is, support to develop progressively independent learning and understanding of when to make use of lecturer-led learning and independent learning. We see this including consideration of open learning, that is learning together beyond institutional boundaries and making use of participatory technologies and social networks (Cronin, Citation2017). This brings opportunities to extend not just learning but also to diversify students’ experiences in boundary-crossing settings beyond the course and institution and to harness the power of professional networks and communities. A starting point is skill enhancement for staff and students to manage the challenge of independent learning. For students, this means providing them with access to the skills needed to learn independently and understand the pedagogic value of group work. An authentic way for this to be of value to students is for them to co-create and collaborate with educators to design curricula, make recordings, and use the richness of their ethnicity and background to enhance the quality of learning. Co-creation has the added value of improving student engagement and well-being that can come with independent and distance learning. While co-creation and collaboration are often undertaken in person, many tools enable these to happen online and for distance learners to engage in fruitful conversations with staff using shared online documents and interactive tools, such as padlets and jamboards in virtual design sessions.

In spite of the contradictory findings, such as a general dissatisfaction with group work, students nevertheless agree that good quality interactions between students and staff and with peers enhances their learning experience, and we therefore make some additional recommendations. For example, where students are unable to appreciate valuable elements of teaching, there is scope and opportunity for further research with students of all ethnicities to better understand the pedagogical value of certain teaching practices, such as group work.

We also recommend educators enhance the learning experience for all students through developing skills to improve and design a range of authentic, collaborative, and inquiry-based learning strategies. Understanding the experience for students is crucial, and we recommend that the student voice and feedback are heard and responded to regarding their learning experience. One of the project objectives is to strengthen the voices of students whose feedback may be overlooked in curriculum design, and the framework (Nerantzi, Citation2017) we use in this paper highlights the need to provide choice, hence our recommendation to co-create and collaborate on designing elements of the curriculum, such as open learning and boundary-crossing, using online mechanisms. The important point is to provide a range and choice rather than try to accommodate all the feedback with a one-size-fits-all approach.

Our findings indicate that educators and universities should move away from the dichotomy of online and face-to-face learning. They should embrace the scaffolding which provides support to students to progressively develop familiarity with modes of teaching and learning that lead to quality learning experiences that in turn help students navigate from lecturer-led learning to independent learning.

Acknowledgments

We would like to record our thanks to all project collaborators from the University of Portsmouth, Manchester Metropolitan University, Solent University, and the University of Nottingham and all students and staff of the following courses at the partner institutions for taking part in the project:

University of Portsmouth: BA (Hons) Accounting with Finance, BA (Hons) Business and Management, BEng (Hons) Civil Engineering, BEng (Hons) Mechanical Engineering, BN (Hons) Nursing (Adult), BSc (Hons) Computer Science, MPharm (Hons) Pharmacy

Manchester Metropolitan University: BEng (Hons) Mechanical Engineering, BSc (Hons) Computer Science, BA (Hons) Business Management, BSc (Hons) Accounting with Finance, BSc (Hons) Adult Nursing

Solent University: BEng (Hons) Mechanical Engineering, BSc (Hons) Adult Nursing, BA (Hons) Business Management.

University of Nottingham: BSc (Hons) Management, BSc (Hons) Finance, Accounting and Management, BSc (Hons) Industrial Economics, BSc (Hons) Computer Science, BSc (Hons) Nursing (Adult).

We would also like to thank Margy MacMillan, our very first critical reader, for her constructive feedback and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was declared by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Harriet Dunbar-Morris

Harriet Dunbar-Morris is responsible for providing leadership in the enhancement of the student experience at the University of Portsmouth. She champions the student voice, ensuring student engagement is central to the university's activities.

Chrissi Nerantzi

Chrissi Nerantzi is an associate professor in education in the School of Education at the University of Leeds. Her research interests include creativity, open education, collaborative learning, networks and communities. Chrissi has initiated many open professional development projects that bring educators, students and the public together.

Melita Panagiota Sidiropoulou

Μelita Panagiota Sidiropoulou has been working for the University of Portsmouth since 2013, initially as a lecturer for the School of Education and Sociology and currently as a senior researcher involved in or leading a variety of student experience surveys, projects, and academic development programs.

Lucy Sharp

Lucy Sharp is the director of the Department for Curriculum Quality and Enhancement at the University of Portsmouth. She leads a diverse portfolio that is dedicated to enhancing the student experience through inclusive learning, innovative learning technologies, and teaching excellence. Lucy is a strategic lead for student well-being.

References

- Association for Learning Technology. (2021). Trends in Learning Technology: Key findings from the 2021 Annual Survey 2021. https://bit.ly/40iERUj

- Arday, J., Branchu, C., & Boliver, V. (2022). What do we know about black and minority ethnic (BAME) participation in UK higher education? Social Policy and Society, 21(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746421000579

- Armellini, C. A., Teixeira Antunes, V., & Howe, R. (2021). Student perspectives on learning experiences in a higher education active blended learning context. TechTrends, 65, 433–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00593-w

- Barnett, R. (2022). The homeless student – and recovering a sense of belonging. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 19(4). https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol19/iss4/02

- Bayne, S. (2015). What's the matter with ‘technology-enhanced learning’? Learning, Media and Technology, 40(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2014.915851

- Bozkurt, A., & Sharma, R. C. (2020). Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to coronavirus pandemic. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), i–vi. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3778083

- College Innovation Network. (2022). Faculty as edtech innovators: Moving beyond stereotypes to promote institutional change. CIN EdTech Survey Series. https://wgulabs.org/cin-edtech-faculty-survey-may-2022/

- Cronin, C. (2017). Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096

- Dunbar-Morris, H., Ali, M., Brindley, N., Farrell-Savage, K., Sharp, L., Sidiropoulou, M. P., Heard-Laureote, K., Lymath, D., Nawaz, R., Nerantzi, C., Prathap, V., Reeves, A., Speight, S., & Tomas, C. (2021). Analysis of 2021 Differing perceptions of quality of learning (Final report). University of Portsmouth. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16892494.v1

- Graham, C. W., & Moir, Z. (2022). Belonging to the university or being in the world: From belonging to relational being. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 19(4). https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol19/iss4/04

- Harkin, B., Yates, A., Wright, L. & Nerantzi, C. (2022). The impact of physical, mental, social and emotional dimensions of digital learning spaces on student’s depth of learning: The quantification of an extended Lefebvrian model. International Journal of Management and Applied Research, 9(1), 50–73. https://doi.org/10.18646/2056.91.22-003

- Jackson, N. (2021). Enriching and vivifying the concept of lifelong learning through lifewide learning and ecologies for learning & practice [White paper]. Lifewide Education. https://www.lifewideeducation.uk/uploads/1/3/5/4/13542890/white_paper_.pdf

- Jackson, N., & Barnett, R. (2019). Introduction. Steps to ecologies for learning and practice. In R. Barnett & N. Jackson (Eds.), Emerging ideas, sightings, and possibilities: Ecologies for learning and practice (pp. 1–16). Routledge.

- Kukulska-Hulme, A., Bossu, C., Charitonos, K., Coughlan, T., Ferguson, R., FitzGerald, E., Gaved, M., Guitert, M., Herodotou, C., Maina, M., Prieto-Blázquez, J., Rienties, B., Sangrà, A., Sargent, J., Scanlon, E., & Whitelock, D. (2022). Innovating pedagogy 2022: Exploring new forms of teaching, learning and assessment, to guide educators and policy makers (Open University Innovation Report 10). The Open University. https://bit.ly/3FCw1bU

- Murray, G. (2014). The social dimensions of learner autonomy and self-regulated learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(4), 320–341. http://sisaljournal.org/archives/dec14/ murray

- Nerantzi, C. (2017). Towards a framework for cross-boundary collaborative open learning for cross-institutional academic development [Doctoral thesis, Edinburgh Napier University]. https://bit.ly/3lsL4yg

- Nerantzi, C., Sidiropoulou, M. P., Dunbar-Morris, H., Sharp, L., Farrell-Savage, K., Heard-Lauréote, K., Speight, S., Nawaz, R. & Ali, M. (2023) Activation: There are other fish in the sea: Open-up and connect. In M. Harrison, M. Paskevicious, & I. DeVries (Eds.), Rethink learning design. Rethink Learning Design. https://rethinkld.trubox.ca/chapter/activation-there-are-other-fish-in-the-sea-open-up-and-connect/

- Stracke, C. M., Burgos, D., Santos-Hermosa, G., Bozkurt, A., Sharma, R. C., Cassafieres, C. S., dos Santos, A. I., Mason, J., Ossiannilsson, E., Shon, J. G., Wan, M., Agbu, J.-F., Farrow, R., Karakaya, Ö., Nerantzi, C., Ramírez Montoya, M. S., Conole, G., Cox, G., & Truong, V. (2022). Responding to the initial challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic: Analysis of international responses and impact in school and higher education. Sustainability, 14(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031876

- Teece, D., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3088148

- Turan, Z., Kucuk, S., & Cilligol Karabey, S. (2022). The university students’ self-regulated effort, flexibility and satisfaction in distance education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19, Article 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00342-w