Abstract

Higher education institutions are increasingly looking to implement online and distance learning (ODL) options for students. Professional development for the design of ODL is needed to support these strategies. This study explores how, in what ways, and to what extent, design for ODL approaches from a series of Learning Design & Course Creation (LDCC) Workshops were implemented. The LDCC Workshop is a mature and substantial professional development activity which adopts a constructivist and student-focused pedagogy and is based on design for ODL approaches embedded at the Open University (UK). Fourteen semi-structured interviews were conducted with participating staff from five Chinese Open Universities. Data was analysed using the Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA) approach. As a result, six “LDCC impact narratives” were identified and are discussed in terms of learning design being implemented in three orientations: product, practice, and process. The findings illustrate that design for ODL approaches were implemented in all three orientations, but the extent to which they were implemented was dependent on certain institutional enablers being present and/or staff being given opportunities to put into practice what they learnt.

Introduction and context

An increasing percentage of educators and executive leaders in higher education (HE) believe online and distance learning (ODL) will be a fundamental component of their future teaching and learning offerings (JISC, Citation2020) but research also suggests that substantial gaps exist between the perceived skills and competencies of educators to design and implement ODL approaches, and the professional development (PD) available to them (JISC, Citation2020; Olney et al., Citation2021; Roberts, Citation2018). For example, in a 2018 study of distance educators, staff at a leading ODL higher education institution, the University of South Africa (UNISA), perceived themselves as having low levels of competency in the roles of technology expert and instructional designer (when compared with other roles such as knowledge expert), and self-identified a need for increased levels of future PD to support these roles (Roberts, Citation2018). However, such PD must be designed carefully to mitigate high levels of educator anxiety (JISC, Citation2020), support changing professional teaching identities (Karunanayaka & Naidu, Citation2020; Philipsen et al., Citation2019) and improve perceptions of quality (Li & Chen, Citation2019; Olney et al., Citation2021).

Rapidly growing student numbers and an increasing demand for quality ODL teaching in Chinese HE is driving rapid educational change (Li & Chen, Citation2019; Qi & Li, Citation2018; Zhang & Li, Citation2019) and a need for PD for the effective design of ODL has been identified in order to help manage this change (Guan & Meng, Citation2007; Olney et al., Citation2021; Zhu & Liu, Citation2020). Analysis of the five-year (2016-2020) development plans of 75 top Chinese HEIs indicated that 50 planned to deliver student-focused and innovative pedagogies through the introduction of digital technologies. However, only eleven also mentioned plans for PD and capacity building of teachers in ODL to support this significant change (Xiao, Citation2019).

The Learning Design & Course Creation (LDCC) Workshop is a model of professional development that has been specifically developed to support the ODL education community in China. It synthesises ODL learning design principles and examples of practice currently in use at the Open University (UK) to address the kinds of challenges and changes identified above.

Since around 2010, learning design has been in use in UK, European and Australian HE educational settings for designing ODL and whilst specific implementations vary depending on context, the three principles of guidance, representation and sharing remain consistent (Dalziel et al., Citation2016). The interpretation of learning design that is currently in practice at the Open University (UK), and reflected in the LDCC Workshop, has its foundation in the findings from the OU Learning Design Initiative (OULDI) which ran from 2007 to 2012. The Open University (UK) and thirteen other higher education institutions participated in the Institutional Approaches to Curriculum Design and Delivery programme which was co-funded by JISC and the European Union (Conole & Wills, Citation2013). Wide ranging interviews with staff at these institutions revealed a multitude of design practices. As a consequence of the OULDI, since 2012 learning design practitioners at the Open University (UK) have sought to embed constructivist approaches that are student- focused and based around the three principles of:

encouraging design conversations and collaboration in design

using tools, instruments, and activities to describe and share designs

developing learning analytics (LA) approaches to support and guide decision-making

The OULDI approach requires consideration of learning design as occupying separate but linked orientations. In the context of the Open University (UK) (UKOU) the term Learning Design can be used to describe a product, (i.e. “a” learning design – a plan or recorded sequence of teaching and learning activities), a practice (i.e. the action of applying Learning Design concepts to the creation and implementation of a piece of teaching and learning) and/or as a process (i.e.one or more events or stages that are attended or completed to assist in the development of a piece of teaching and learning) (Dalziel et al., Citation2016).

In the daily life of the UKOU, learning design workshops provide a mechanism for bringing together multi-disciplinary staff in teams to design new curriculum. Outputs from these workshops are then recognised as key components in an internal quality assurance process (Galley, Citation2015).

A recent comprehensive literature review by Philipsen et al. (Citation2019) of fifteen articles written between 2005 and 2014 on PD programs that target approaches to distance education highlighted a scarcity of relevant research. It found that whilst there is a great deal of research on delivering PD online, PD for the design of blended and online distance education was not well represented in the literature (Philipsen et al., Citation2019). Despite this, the authors developed a professional development framework that consisted of six components based on the synthesised findings of the fifteen studies. The framework identified these components as: (1) developing supportive environments, (2) acknowledging existing contexts, (3) determining clear and relevant goals, (4) adopting strategies to encourage reflection, active learning, and peer support, (5) establishing ongoing evaluation, and (6) addressing changes to the professional identity and educational beliefs of teachers.

The pedagogy of the LDCC Workshop draws on these components and provides a structured way to present design for ODL educational principles, tools, activities, and examples of practice currently in use at the UKOU. For simplicity, these are referred to collectively as LDCC approaches (for a detailed description of LDCC approaches, see Olney et al., Citation2023). By November 2022 around 850 Chinese staff, from at least eight different institutions, had participated in 33 instances of the LDCC Workshop. Through a series of structured, collaborative activities it challenges participants to design an ODL course of their own in a compressed timeframe and offers opportunities for a re-examination of their own design practices. This model has been adopted to maximise support for, and manage changes to, the professional teaching identities of participants who may be required to adapt from designing traditional education to ODL.

Prework and Research Question

In a study by Olney and Piashkun (Citation2021), feedback from the LDCC Workshop was used to demonstrate impact on 5 Belarussian ODL design teams tasked with creating five ODL courses as part of the Enhancement of Lifelong Learning in Belarus (BELL) Project. The study used the Academic Professional Development Effectiveness Framework (APDEF) indicators (Chalmers & Gardiner, Citation2015) as part of a deductive and essentialist methodology to demonstrate that the pedagogy and content of the LDCC Workshop was effective in preparing the design teams to design and create their chosen modules (Olney & Piashkun, Citation2021). Another study (Olney et al., Citation2021), mapped feedback from 220 LDCC Workshop participants from three Chinese OUs against the Instructional Design Competencies Framework provided by the International Board of Standards for Training, Performance, and Instruction (IBSTPI) to demonstrate how learning design could enhance quality. Based on this analysis, the study suggested conceptualising competencies required for Chinese ODL designers around being a professional, a collaborator, a communicator, and a student-focused educator (Olney et al., Citation2021). Using the results from an impact survey of 134 Chinese LDCC Workshop participants, and a detailed exploration of the LDCC Workshop pedagogy, a further study contended that past participants were able to successfully implement LDCC approaches when they were presented as a set of normative practices in a constructivist environment which allowed for consideration, debate, adaptation, and modelling of student-focused learning (Olney et al., Citation2023). However, limitations in the survey instrument were evident and the study recommended that detail of the ways and extent of implementation could be revealed by follow-up qualitative interviews.

This recommendation led to the development of the research question (RQ) that guides this study, which is:

RQ: How, in what ways, and to what extent, were LDCC approaches implemented by the participants?

Materials and methods

Ethics approval for this study was secured from the UKOU Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC). Previous participants were approached by their institutions and information and consent forms were provided. In total, 14 previous participants from five different OUs agreed to take part in the study. The interview instrument focused on four areas of interest: a. establishing identity, b. implementation, c. institutional context & support and, d. impact on professional identity, and was shared with the interviewees prior to interview. The interviews were semi-structured allowing for the interviewees to share and explore whatever themes or examples were most meaningful for them. Interviews were facilitated by Author2 & Author3 in a mixture of English and Mandarin using MS Teams software. The interviews ranged in length from 1 to 2 hours. Interview audio/visual files were downloaded to a secure MS Teams site along with automatically generated initial transcripts. The original audio/visual files were securely shared with professional translators hired for the purpose and based in China, who checked the transcription and completed full translations into English. These English transcriptions were anonymised then checked for accuracy and nuanced meaning by an interpreter who had previously worked as a translator during the LDCC Workshop, and Author3.

Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA) is a widely recognised approach to qualitative analysis in education developed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2019). RTA offers a-six phase approach to analysis which includes the adoption of coding techniques in which the researcher “must actively construe the relationship among the different codes and examine how this relationship may inform the narrative of a given theme” (Byrne, Citation2022, p. 1403). RTA allows for the adoption of different underpinning theoretical assumptions which should be acknowledged as being most appropriate for the data set and research question. This study adopted an inductive and constructionist epistemology in which codes were generated because of the data generated and that meaningfulness was reported independently of recurrence (Byrne, Citation2022). The six-phases were employed by Author1 and the other UKOU researchers to ensure consistency of analysis as appropriate. The electronically produced transcriptions were imported into NVivo 12 software to assist in the reliable production of codes and themes.

The use of this version of RTA also allows for an evaluation of both direct and indirect, intended and unintended, effects of the PD and to present evidence on the difference the LDCC Workshop makes inside and outside of the explicit objectives. This is reflected in the use of the word “impact,” rather than “effectiveness” in the RQ (OECD, Citation2019).

Results

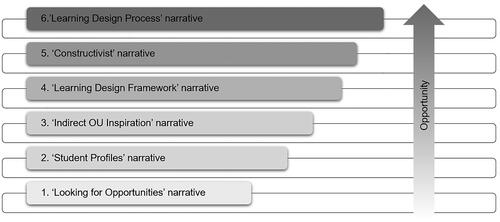

The analysis allowed for the identification of six “LDCC impact narratives” which are visualised in according to the extent of opportunity expressed in the interviews. The narratives are not exclusive, meaning that interviewees may appear in more than one. Interviewees are identified by a number, e.g. #01, and institution, e.g. OUZ, and square brackets, [#01-OUZ] where direct reference is required.

1. “Looking for opportunities” narrative

This narrative was evidenced in the interviews with #05-OUY, #06-OUV, #08-OUV and #10-OUY. It is characterised by these interviewees being motivated to implement at least one LDCC approach into their practical work, which they describe as “necessary” [#10-OUY], “very good” [#08-OUV], “excellent” [#06-OUV] and “rich” [#05-OUY], but also expressing that they did not have the agency to do so. As #08-OUV said, “Maybe I want to implement it, but to be honest, I lack the conditions to implement.” However, these interviewees identified certain enablers that they felt, if introduced, might help them to implement.

Improved cooperation within the OU system and between departments was identified as such an enabler. #06-OUV described their role as being like a “layer” or a “bridge,” “…just a part in the middle” of a much larger system which left them without, “…too many spaces for us to adapt or change” and saying implementation “…needs a process.” #08-OUV highlighted the investment their HEI was making in producing new learning resources but called for “the active support from other departments” to ensure they would be used to implement LDCC approaches and “build high quality courses in the future.” For this interviewee, some “follow-up practice,” “further application” or “reflection” facilitated by “a leader” was important but missing. For the other two interviewees, institutional “guidance of quality when designing courses” [#05-OUY] and “institutional support from the university” [#10-OUY] were identified as enablers they felt they wanted to see introduced.

Another enabler was the improvement and development of educational technologies. Primarily these were required to help overcome the challenge of supporting large volumes of students, whilst also introducing student-focused learning methods which “we think…cost us much[sic] energies because we only have limited supporting tools” [#10-OUY]. #08-OUV also linked “technical limits and the reality in China” as constraints on implementation. For #05-OUY, an improved communication platform was an enabler, since “sometimes we say we want to communicate more with our students, but the fact is there are so many students, even if you spend 5 minutes with one student, there are thousands of students. So, I was thinking can we change the way we communicate, this is just an idea, I want to change it, but I have no clue about how to change it.”

2. “Student profiles” narrative

This narrative was evidenced in the interviews with #03-OUV, #07-OUY and #09-OUY. It is characterised by the interviewees making changes to their practice to get to know their students better as inspired by the student profiles activity in the LDCC Workshop. These interviewees indicated they had started scholarship initiatives to enable the adjustment of learning designs based on data and student feedback. What is common to these teaching reforms is a mutual understanding of the necessity to build collaborative networks with technical specialists in other universities [#03-OUV], internal departments [#07-OUY] and/or professional external companies [#09-OUY] to collect, classify, sort and display learning analytics in meaningful ways. All three interviewees interpreted these initiatives as being closely associated with the more general student-focused pedagogy discussed in the LDCC Workshop. Despite these proposed reforms being complicated and requiring coordination of others #09-OUY described the value they placed on a feedback implementation that resulted in substantial data-driven adjustments to the way video assets were organised on a module saying “in these interactions [with students] I can realize what is being student-first…changing my teaching design focusing on them. With their feedback we can achieve our respective goals together. I am satisfied, so they are satisfied.”

3. “Indirect UKOU inspiration” narrative

This narrative was evidenced in the interviews with #09-OUY, #11-OUY and #12-OUV. It is characterised by the interviewees making changes to their practice as inspired by ODL approaches not necessarily core to the LDCC Workshop but referred to in passing, or inspired by other parts of the UKOU, or in conversations with UKOU staff. However, these initiatives were design based and included, for example, the development of introductory module videos, a screen reader for visually impaired students, audio texts for commuters, case studies, animations, and a mobile learning app. As one interviewee put it, “every time I was awarded or being acknowledged, I got the idea from the [UK]OU” [#11-OUY]. In general, interviewees in this narrative were motivated by a desire to improve the experience of study and were able to exhibit some agency over the design of their module in implementing these improvements.

4. “Learning design framework” narrative

This narrative was evidenced in the interviews with #11-OUY and #13-OUW. It is characterised by the interviewees organising the learning design of a module around the concept of time. #11-OUY highlighted that what the LDCC Workshop and subsequent practice had taught them is that “classes without design and courses without design, they are destined to fail.” For them, “the schedule for one semester is fixed. Therefore, especially when teaching remotely, I think the ability to arrange the time is very important. You have to design everything step by step, every step counts.” This design principle approach avoids the common problem of “teachers who have explained things in a very detailed way with clear content at the beginning, but then later they don’t pay that much attention to the key points due to a lack of time.”

#13-OUW explained how they had learnt about this approach from a previous LDCC Workshop but did not have the opportunity at that point in time to implement it. However, several years later, when the opportunity to restructure a very large compulsory English language course which was required for the continuation of students onto majors arose, they were able to implement it using their notes and the collaborative experience of designing from the LDCC Workshop. The problem with the course was identified that “students are not worried about the lack of resources…they are lost about which ones they have to learn, and which ones are for supplementary learning.” In fact, the previous learning design was “that we simply offer them [students] the universal teaching materials and resources platform and ask them to arrange the study themselves” and this approach was leading to demotivation and poor retention [#13-OUW]. The solution: “we thought of the study calendar [from the LDCC Workshop], about the activities, so we said how about we arrange the daily tasks for the students?” and “…turn each unit into a to-do list like a study calendar. I will fix the study task for them and the recommended time to do this task” [#13-OUW].

The success of this teaching reform resulted in the publishing of “some thesis” and “an article about how does the experience of OU enlighten us [sic]” comparing “what we learnt from OU with our previous work practice.” For #13-OUW, “many things [from OU] we haven’t put them into practice right away, but when there is an occasion, you will see that your accumulation of knowledge is very important. You use it, and you will feel rewarded.”

5. “Constructivist” narrative

This narrative was evidenced in the interview with #14-OUX. It is characterised by the interviewee adopting the constructivist LDCC pedagogy into the internal teacher professional development and training approach in their institution. In this implementation #14-OUX was able to design teacher training that was activity-based and outcome-orientated in which, “teachers are more like a guide…rather than simply passing on the knowledge” explaining that “before I just knew that teachers should play such roles, to guide the students, but the [LDCC] workshop showed me how to play this role and achieve the goal” and that “I think we learned more than the content of the workshop, but also the workshop itself as a form of training.” Importantly, #14-OUX also explained how they leveraged the constructivist experience of other teachers to support them in designing training activities in areas such as the application of AI, saying “…together we used a set of concepts introduced in the LDCC workshop for teachers to develop courses to design a training for our teachers.”

For #14-OUX, this implementation was driven by a motivation to enhance the quality of the education provided and was enabled by the “leaders of the department” being “very supportive” and providing “development funds.” However, they also highlighted how the support of teachers taking on the design of the training “through cooperation, that we learn from each other” to “transfer their skills” was crucial to success and resulted in them winning “the good remarks of the teachers” [#14-OUX].

6. “Learning design process” narrative

This narrative was evidenced in interviews with #01-OUZ, #02-OUZ, #04-OUZ and #09-OUY. It is characterised by the mandated implementation of LDCC approaches into curriculum standards “following the process of UKOU…from learning outcomes to analysis of each module” [#02-OUZ]. For OUZ, LDCC approaches constitute the teaching and learning design part of their wider quality enhancement strategy, which also includes the embedding and reporting of technical and academic standards. As #02-OUZ explains, “ever since we launched the LDCC workshop, we have applied a series of tools from OU, so from the perspective of design, if you are to carry out the design of a course, there isn't much difference [with the OU approach].” In line with the LDCC Workshop pedagogy, LDCC approaches such as vision statement, learning outcomes, student profiles and activity type classifications have been “adapted…,” so that they, “…are easier for teachers from our school to understand and apply” [#04-OUZ] and are included in a module specification report for which institutional approval is required. #09-OUY also references the introduction of a “detailed project creation report for each of our new courses” from 2020 from which “the university will carry out several evaluations.”

This structured implementation of LDCC approaches has been driven by a desire to enhance the quality of the ODL provided and gain future awarding accreditation. As #01-OUZ explains, “whether you study in full-time university, or study in [OUZ] for undergraduate study, we should make the public think these are the same. The educations are of same quality. I think this is very important.” For #02-OUZ, an important part of the value of LDCC approaches is that they are specifically suitable to ODL, explaining that “previously we notice that our teachers copy the teaching plan of the face-to-face course and then turn it into a video course, which is not so right.”

To realise educational change on this scale OUZ have leveraged several enablers. At an individual level, between 2019 and 2021, 330 staff have attended and completed the LDCC Workshop with internal feedback indicating at least “60% of the teachers have applied the knowledge they have learned to their daily teaching”…and… “almost 90% of teachers feel that they can accept and grasp the theories” [#04-OUZ]. Individual teachers are often required to write reports about their experiences, especially when travelling abroad and are incentivised with bonuses for completing the production of new modules on time and meeting the quality standards [#02-OUZ]. Entering and winning teaching competitions are popular and, “in the teaching competition, we noticed that when our teachers answered questions about educational design, they could follow the ideas of LDCC” which resulted in “quite some effects” [#02-OUZ].

At a wider college level, LDCC participants are supported to present and discuss and adapt LDCC approaches in seminars or PD activities with their colleagues and peers. A coordinated course production process in which “many efforts have been taken by many departments jointly” has been developed in which a teacher must submit a LDCC approaches course design plan, which is reviewed and approved by “special experts,” then revisited midway through creation, and once completed [#04-OUZ].

Institutionally, there is also a commitment to future developments from OUZ with the LDCC Workshops included “in the university’s entire plan” [#01-OUZ]. For #02-OUZ, a primary reason why their institution keeps supporting and financing this implementation is because of the “follow-up reports [and] interviews with the participants” that are conducted, and the positive evidence base they have collected. Also, OUZ has “won many awards every year” from this work and offers the only national first-class undergraduate degree awarded by the Open University of China [#02-OUZ].

Discussion

In line with the research question, the six “LDCC impact narratives” provide valuable insight into the ways, and extent to which, the LDCC approaches were implemented. In order to discuss these narratives in context they are grouped below according to the three roles of learning design described in the introduction, that is, as: product, practice, and process:

Learning design as product

In the “Learning Design Framework” narrative the previous participants described their implementation in terms of an actual module learning design being shaped as a result of LDCC approaches. In this narrative it is clear that the participants spent considerable time and effort planning the learning design with a student-focused view taking care to present the learning materials in a coherent structure and consider the time allocation of activities in order to design a deliberate student experience. What is clear is that a learning design was produced as a result that attempts to “captures the pedagogical intent of a unit of study” (Lockyer et al., Citation2013, p. 1442) For Dalziel et al. (Citation2016) this product is the basic building block in the conceptual idea of a Learning Design Framework (LD-F) that calls for a visual language or notational system for describing teaching and learning activities based on different pedagogical approaches. This has also been described as building pedagogical patterns (Laurillard, Citation2012). At the UKOU the LD-F incorporates the allocation of a modified version of the Activity Type Classification Types (Conole, Citation2013) and expected student time to learning designs which can then be captured in an online Learning Design Tool and analysed to improve learning and the environments in which it occurs (Olney et al., Citation2019; Toetenel & Rienties, Citation2016). In recent years there have been multiple calls for PD to support the alignment of learning design work with learning analytics and embed the representation, reusability and sharing of teaching and learning in ways such as this (Laurillard, Citation2012; Mor et al., Citation2015; Rienties et al., Citation2018).

Learning design as practice

Participants also described implementing learning design as practice in several of the impact narratives. In Learning Design Practice (LD-P) learning design is used as a verb and described as “the day-to-day practices of educators as they design for learning” (Dalziel et al., Citation2016, p. 21). The intention to incorporate LDCC approaches into daily practice was prevalent in the “Looking for Opportunities” narrative. Realisation of this intent was evidenced in the “Student Profiles” narrative (where participants detailed how they were focused on building collaborative networks and establishing feedback cycles into their daily practice) and the “Indirect OU Inspiration” narrative (where a variety of implementations were detailed) primarily in order to implement student-focused learning. This finding is supported by the results from a separate survey instrument that found that, when asked about implementing LDCC approaches, 50 from 119 responses grouped practice approaches together and referenced them as student-focused learning (Olney et al., Citation2023). Further, by far the largest response to a question about the perceived benefits of implementing LDCC approaches was to “design student-focused learning” (for example, twice as many as “describe and share teaching and learning” see product above) (Olney et al., Citation2023). Given that the participants were mostly teachers and academics engaged with the practical work of supporting students and tasked with design questions on a daily basis this is not surprising. The tools and activities presented as components of the LDCC approaches are adaptable and accessible in all contexts and facilitate the production of many smaller design artefacts (vision statement, student profile, learning outcomes) that build towards the creation of a final learning design product described above.

However, what these impact narratives also highlight is the challenges experienced by these participants and the restraints they felt as a result of the institutional systems and sites in which their practice was situated. In many cases these arrangements did not allow for agency and opportunity to adapt and implement learning design as practice. A literature review of the barriers to the adoption of learning design methods and tools highlighted that “focus on the usability of specific tools may distract the attention away from factors that are tool-independent” such as the importance of building peer communities and teams, lack of institutional support and teacher motivation (Dagnino et al., Citation2018). Further, Agostinho, Lockyer & Bennett call for institutions to support teachers and academics design work and the implementation of learning design practice by facilitating networks that are “inherently social” (Agostinho et al., Citation2018, p. 9). What these narratives highlight is that several participants suggested they needed more institutional support in order to implement LDCC approaches. The first step to this could be mapping current learning design practice utilising the “theory of practice architectures” as a theoretical methodology in order to identify gaps and review supporting arrangements (Bennett et al., Citation2018).

Learning design as process

The “Learning Design Process” narrative detailed how teachers and academics at one HEI in particular (OUZ) had been able to implement LDCC approaches in a way that drew together all three of the orientations of learning design into a complete process. Crucial to this was aligning learning design with teaching and learning quality assurance and/or enhancement approaches. As has been previously described, implementing both learning design as practice and as product results in the creation of artefacts which can be documented and shared with other teachers and academics. Learning design as a process encourages the further sharing of these with administrators and managers tasked with monitoring and assuring quality. Dalziel et al. (Citation2016) call for the creation of a Learning Design Conceptual Map (LD-CM) that details the wider educational landscape into which the specific learning design fits and relates to other core learning design concepts in a visual way. In the context of the UKOU this idea has proved difficult to implement as described but is in some way replaced by a module specification report which serves a similar purpose and includes an intended learning design product. Examples of learning design as process with improvements to quality as a goal in HEI include, but are not limited to, the stage-gate OULDI process (Galley, Citation2015), The Design Develop Implement process (Seeto & Vlachopoulos, Citation2015), the Design for Learning process (Ghislandi & Raffaghelli, Citation2015) and the Scaffolded TPACK Lesson Design Model (Chai & Koh, Citation2017).

The implementation of LDCC approaches as the basis for the teaching and learning quality assurance strategy at OUZ represents the remarkable impact of the LDCC Workshop and suggest the potential for further implementation at other HEI. What is clear from the evidence collected in the “Learning Design Process” narrative is that PD can play a substantial role in the implementation of learning design as process when coupled with institutional support and mechanisms for encouraging peer support and teacher motivation as suggested by Dagnino et al. (Citation2018) and Agostinho et al. (Citation2018).

Unintended implementation

In contrast to the deductive and essentialist methodology employed by Olney and Piashkun (Citation2021) the RTA evaluation methodology employed here allowed for a broad, long-term, contextualised interpretation of impact which could capture both intended and unintended impacts to address the RQ. A good example of such an unintended impact is captured in the “Constructivist” narrative whereby the interviewee reported that rather than implementing any LDCC approaches directly, attending the LDCC Workshop enabled them to participate in a social-constructivist environment and go on to apply this in their own internal PD offerings. This narrative provides evidence of the value of utilising a research methodology such as RTA in order to identify and surface examples of “shadow practices” (McCoy & Rosenbaum, Citation2019).

Limitations and future work

The limited sample of fourteen interviews used in this study means that the experiences of many of the past participants are unable to be included. The interviewees were also largely self-selecting, and it is possible this has led to some unrepresentative bias of the cohort as a whole. However, the scope and depth of the detailed interview technique adopted here meant that any increased numbers of interviews would have made the research workload unfeasible. Further interviews with members of staff mentioned by interviewees but not taken further might illuminate the findings further.

The interview instrument used for this study focused on four areas of interest: a. establishing identity, b. implementation, c. institutional context & support and, d. impact on professional identity. The findings reported here have been drawn primarily from areas b and c. Questions of impact on professional identity are out of scope for this paper but are intended to be reported separately. The professional identity of teachers has been highlighted as an underrepresented concern of PD for the design of ODL (Karunanayaka & Naidu, Citation2020; Philipsen et al., Citation2019) and future work will, therefore, involve the analysis of areas a. and d. in the interviews in order to explore this in detail and uncover further narratives.

Conclusion

The lessons learnt from the six LDCC impact narratives revealed that the participants from Chinese OU implemented LDCC approaches to support design for ODL work in a variety of ways that included considering learning design in all three of its orientations: product, practice, and process. For many of the participants LDCC approaches represented a very different way of thinking about design for ODL. The practice orientation was most commonly evidenced, yet limitations in opportunity meant in several cases it remained as an intention only. The extent of implementation was evidenced most extensively when learning design was considered in the process orientation, although this was only recorded in the case of OUZ, which took a far more holistic, institutional approach to implementation than the other OU.

For Chinese OU faced with the challenges of guiding and supporting their staff in designing quality ODL as part of a digital transformation strategy, the LDCC Workshop should be viewed as providing a valuable model. The use of RTA as a methodology allowed for the interviews to also surface an unintended implementation in the form of a pedagogical shift towards constructivism as guiding the design of internal PD. Taken together, the narratives suggest that the way, and extent to which, implementation took place in terms of learning design as product, practice or process was heavily dependent on the opportunity the participants experienced, and appropriate institutional enablers being in place to support implementation.

Disclosure statement

Tom Olney was employed as a consultant to develop and facilitate some of the instances of the LDCC Workshop referred to in the study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and or analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tom Olney

Tom Olney is Senior Manager Learning & Teaching in the Faculty of STEM at the UKOU. He has a background in teaching and global politics. His research interests include the implementation of learning design and learning analytics approaches in the higher education sector.

Daphne Chang

Daphne Chang is a Senior Lecturer and Staff Tutor in the Engineering and Innovation School in the Faculty of STEM at the UKOU. She has a background in anthropology. Her research interests include international development and the scholarship of education.

Lin Lin

Lin Lin is a Visiting Fellow in the Faculty of STEM at the UKOU. She has a background in sociology and managing international higher education partnerships. Her research interests include professional development approaches in the Chinese OU sector.

References

- Agostinho, S., Lockyer, L., & Bennett, S. (2018). Identifying the characteristics of support Australian university teachers use in their design work: Implications for the learning design field. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3776

- Bennett, S., Lockyer, L., & Agostinho, S. (2018). Towards sustainable technology-enhanced innovation in higher education: Advancing learning design by understanding and supporting teacher design practice. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(6), 1014–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12683

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & quantity, 56(3), 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

- Chai, C. S., & Koh, J. H. L. (2017). Changing teachers’ TPACK and design beliefs through the Scaffolded TPACK Lesson Design Model (STLDM). Learning: Research and Practice, 3(2), 114–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2017.1360506

- Chalmers, D. & Gardiner, D. (2015). An evaluation framework for identifying the effectiveness and impact of teacher development programmes. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 46, 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.02.002

- Conole, G. (2013) Designing for learning in an open world. In Explorations in the learning sciences, instructional systems and performance technologies (Vol. 4). New York: Springer.

- Conole, G & Wills, S. (2013). Representing learning designs – Making design explicit and shareable. Education Media International, 50(1), 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2013.777184

- Dagnino, F. M., Dimitriadis, Y. A., Pozzi, F., Asensio-Pérez, J. I., & Rubia-Avi, B. (2018). Exploring teachers’ needs and the existing barriers to the adoption of Learning Design methods and tools: A literature survey. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(6), 998–1013. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12695

- Dalziel, J., Conole, G., Wills, S., Walker, S., Bennett, S., Dobozy, E., Cameron, L., Badilescu-Buga, E. & Bower, M. (2016) The larnaca declaration on learning design. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 1(7), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.407

- Galley, R. (2015). Learning Design at the Open University: introducing methods for enhancing curriculum innovation and quality. Quality Enhancement Report Series (1), Institute of Educational Technology (IET), The Open University. Retrieved from http://article.iet.open.ac.uk/Q/QE%20report%20series/2015-QE-learning-design.pdf

- Ghislandi, P. M., & Raffaghelli, J. E. (2015). Forward-oriented designing for learning as a means to achieve educational quality. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(2), 280–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12257

- Guan, Q., & Meng, W. (2007). China’s new national curriculum reform: Innovation, challenges, and strategies. Frontiers of Education in China, 2(4), 579–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11516-007-0043-6

- JISC. (2020) Learning and teaching reimagined: Synthesis of audience surveys. Retrieved from https://repository.jisc.ac.uk/8153/1/learning-and-teaching-reimagined-synthesis-of-audience-surveys.pdf

- Karunanayaka, S. P., & Naidu, S. (2020). Ascertaining impacts of capacity building in open educational practices. Distance Education, 41(2), 279–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1757406

- Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as a design science: Building pedagogical patterns for learning and technology (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203125083

- Li, W. and Chen, N. (2019) Chapter 2: China. In O. Zawacki-Richter, & A. Qayyum (Eds.), Open and distance education in Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Singapore: Springer Briefs in Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-5787-9

- Lockyer, L., Heathcote, E., & Dawson, S. (2013). Informing pedagogical action: Aligning learning analytics with learning design. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(10), 1439–1459. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213479367

- McCoy, C., & Rosenbaum, H. (2019). Uncovering unintended and shadow practices of users of decision support system dashboards in higher education institutions. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 70(4), 370–384. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24131

- Mor, Y., Ferguson, R., & Wasson, B. (2015). Learning design, teacher inquiry into student learning and learning analytics: A call for action. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(2), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12273

- OECD. (2019) Better criteria for better evaluation: revised evaluation criteria definitions and principles for use. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/revised-evaluation-criteria-dec-2019.pdf

- Olney, T., Li, C. & Luo, J. (2021) Enhancing the quality of open and distance learning in China through the identification and development of learning design skills and competencies. Asian Association of Open Universities Journal, 16(1), 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAOUJ-11-2020-0097

- Olney, T. & Piashkun, S. (2021). Professional development for sustaining the ‘pivot’: the impact of the Learning Design and Course Creation Workshop on six Belarusian HEIs. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2021(1), 10. https://jime.open.ac.uk/articles/10.5334/jime.639/ https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.639

- Olney, T., Rienties, B., Chang. D. & Banks, D. (2023) The Learning Design & Course Creation Workshop: Impact of a professional development model for training designers and creators of online and distance learning. Technology, Knowledge & Learning, 29(1), 45–63. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10758-022-09639-1 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-022-09639-1

- Olney T, Rienties B & Toetenel L. (2019). Chapter 6: Gathering, visualising and interpreting learning design analytics to inform classroom practice and curriculum design. In J. Lodge, J. Horvath, & L. Corrin (Eds.), Learning analytics in the classroom: Translating learning analytics for teachers (pp. 71–92). Routledge Press. ISSN 1351113011.

- Philipsen, B., Tondeur, J., Pareja-Roblin, N., Vanslambrouck, S., Zhu, C. (2019) Improving teacher professional development for online and blended learning: A systematic meta-aggregative review. Educational Technology and Research Development, 67, 1145–1174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09645-8

- Qi, Y & Li, W (2018) The Open University of China and Chinese approach to a sustainable and learning society. In Exploring the Micro, Meso and Macro: Proceedings of the European Distance and E-Learning Network (EDEN) 2018 Annual Conference, Genova, 17–20 June 2018. https://doi.org/10.38069/edenconf-2018-ac-0067

- Rienties, B., Herodotou, C., Olney, T., Schencks, M., & Boroowa, A. (2018) Making sense of learning analytics dashboards: A technology acceptance perspective of 95 teachers. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(5), 186–202. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i5.3493

- Roberts, J. (2018) Future and changing roles of staff in distance education: A study to identify training and professional development needs. Distance Education, 39 (1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2017.1419818

- Seeto, D., & Vlachopoulos, P. (2015) Design develop implement (DDI)—A team-based approach to learning design. In THETA 2015 Conference, Gold Coast, Australia.

- Toetenel, L., & Rienties, B. (2016). Analysing 157 learning designs using learning analytic approaches as a means to evaluate the impact of pedagogical decision making. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(5), 981–992. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12423

- Xiao, J. (2019) Digital transformation in higher education: critiquing the five-year development plans (2016-2020) of 75 Chinese universities. Distance Education, 40:4, 515–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2019.1680272

- Zhang, W., & Li, W. (2019) Transformation from RTVUs to Open Universities in China: current state and challenges. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 20(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v20i4.4076

- Zhu, X. & Liu, J. (2020) Education in and after Covid-19: Immediate responses and long-term visions. Postdigital Science & Education, 2, 695–699. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00126-3