Abstract

Flexibility in distance education is often regarded as an inherently positive concept. Taking a more critical approach, this article distinguishes between temporal-spatial flexibility, defined as enabling students to choose the time, pace and place of their studies, and pedagogical flexibility, defined as offering education that is tailored to the pedagogical needs and preferences of students. This study aims to investigate pedagogical flexibility in distance education characterized by a high degree of temporal-spatial flexibility. Focus group interviews with 46 adult distance educators were conducted. Themes that explained reasons for lower and higher degrees of pedagogical flexibility were identified. It was found that pedagogical flexibility was challenging to achieve in a setting characterized by high temporal-spatial flexibility. In conclusion, a model of temporal-spatial and pedagogical flexibility is discussed. It can be used to guide research and practice in understanding flexibility in distance education as a complex and nuanced concept.

Introduction

Flexible distance education is the result of a long history of efforts to make education more inclusive for students. It is commonly defined in terms of the pace, place and mode of delivery (Lockee & Clark-Stallkamp, Citation2022). Unpacking some of the many dimensions of flexible education, Collis (Citation1998) suggests that flexibility can be improved in relation to 1) location: students can influence where their studies take place; 2) program: students can choose courses based on their needs and interests; 3) interaction: students have the opportunity to study individually or in groups based on need; 4) communication: students can communicate with students and teachers in different ways; and 5) study materials: students can influence and contribute to the study materials used. Moreover, flexibility can be related to student-centeredness, where the teacher or educational institution does not design a course or program in advance, but gives students the opportunity to influence learning material, activities, and course structure (Collis & Moonen, Citation2002).

While flexible education is often defined in inherently positive ways, there are structural factors that influence the degree to which flexibility can be achieved. Such factors include the educators’ workload and competence, the resources available at the educational institution (Collis & Moonen, Citation2002) and the characteristics of student groups, such as the extent to which students are self-directed and self-motivated (Samarawickrema, Citation2005). Flexibility might sometimes need to be compromised for pedagogical reasons (Collis, Citation1998).

Although the term flexible education has different meanings in the literature, it is commonly defined as allowing students to choose the time, pace and place of their studies (Lockee & Clark-Stallkamp, Citation2022), a type of approach which can be labeled temporal-spatial flexibility. While flexible education is often described as liberatory, questions of who it makes free and in what ways are rarely asked. The extent to which the affordances of flexible education meet the needs of different students, in essence, subjected to “the freedom to take responsibility for oneself” (Houlden & Veletsianos, Citation2021, p. 144), can be questioned. There are also concerns about the kinds of work that adult students, who might have work and family commitments, are required to demonstrate if they are to succeed in flexible education (Houlden & Veletsianos, Citation2019). Heavy demands are often placed on these students to be self-directed, self-motivated (Samarawickrema, Citation2005), digitally competent and in possession of the technology needed to benefit from flexible distance education (Gärdén, Citation2010). As researchers and practitioners, we need to ask: Which students benefit from certain flexible distance education designs? For example, an adult student who works full-time might prefer independent study, but it might not necessarily be the best decision from a pedagogical point of view. Likewise, an education provider might prefer to offer flexible distance education so they can manage continuous enrollments or increase profits. Many such courses are based on self-study materials rather than meeting students’ actual pedagogical needs (Mufic, Citation2023). The type of education which is tailored to meet the actual pedagogical needs of students can be called pedagogical flexibility.

Temporal-spatial flexibility

Temporal-spatial flexibility can be defined as enabling students to choose the time, pace and place of their studies. Time is about being able to start studying flexibly. Attending class synchronously and at specific times may be a constraint for some students. Asynchronous education is more flexible but requires students to be self-regulated and motivated with procrastination and noncompletion as associated challenges (Lockee & Clark-Stallkamp, Citation2022). The pace of study can also increase flexibility by giving students control over when to complete assignments and courses. However, in order to complete a course, students need to be motivated. Equally, it can be a challenge to support collaborative learning (Chen, Citation2003). Place refers to the student’s ability to choose their study location, or to choose different locations during a course, such as studying from home or at school.

While many students prefer distance education that is flexible in regards to the time, pace and place of studies, this choice has an impact on both educators and students. For educators, it can be time-consuming to flexibly meet the needs of different students at different stages in a course. For students, flexibility can have a negative impact on student learning and retention, especially if they are not self-regulated and motivated (Lockee & Clark-Stallkamp, Citation2022). Too much independence can isolate students from other educators, their peers, and the educational institution itself, which can lead to procrastination, delay, and attrition (Naidu, Citation2017). Since different students have different needs, distance education should be sufficiently pedagogically flexible so as to accommodate their needs.

Pedagogical flexibility

Pedagogical flexibility can be defined as offering education that is tailored to the pedagogical needs and preferences of students. Working as a distance educator requires a willingness to adapt to the constraints of flexible distance education, a skill in adopting flexible teaching methodologies (Veletsianos & Houlden, Citation2019) and a willingness to meet students where they are (Valcke & Martens, Citation1997). Educators need to become facilitators. They need to become “more like an advisor, coach, guide or mentor who not only presents concepts and organizes the learning environment but also helps learners study, question, reflect on and relate their experiences to others” (Naidu, Citation1997, p. 259). Individual tutoring, for example, is commonly needed when students study at their own time and pace. Thus, designing and teaching in flexible ways can require more time than conventional teaching (James & Beattie, Citation1996).

Significant pedagogical scaffolding is required to support student learning in courses with continuous enrollment and where progression occurs at different paces. Study material can be made flexible by allowing students to select their own materials and giving them choice over how to engage with that material (Valcke & Martens, Citation1997). Further, content in different media formats, such as text, audio and video, can be used to support student accessibility and personal study preference. For self-paced content, flexibility might mean allowing content to be completed in smaller segments or shorter sequences, thus allowing students to decide according to their personal study preferences (Lockee & Clark-Stallkamp, Citation2022). For collaborative learning, alternative approaches might need to be supported, such as the cooperative freedom model (Paulsen, Citation1992). Dalsgaard and Paulsen (Citation2009) suggest supporting cooperative freedom and transparency defined as “students’ and teachers’ insight into each other’s activities and resources … to enable students and teachers to see and follow the work of fellow students and teachers within a learning environment and in that sense to make participants available to each other as resources for their learning activities” (p. 2). Even learning outcomes and how to assess these can be negotiated (James & Beattie, Citation1996).

Developing pedagogically flexible distance education requires development time, technological skills, and the production and provision of clear guidance and support for students (Lockee & Clark-Stallkamp, Citation2022). “[F]lexible learning is only flexible insofar as it can be adapted to by learners, and this process is not necessarily easy or intuitive” (Veletsianos & Houlden, Citation2019, p. 460). Students need to be prepared for flexible adult education and supported while doing it (Brewer & Yucedag-Ozcan Citation2013).

A model of temporal-spatial and pedagogical flexibility

Moore’s theory of transactional distance (1997) is useful for understanding the opportunities and challenges of temporal-spatial and pedagogical flexibility in distance education. Three variables control transactional distance: dialogue, structure and student autonomy. For example, if students prefer or need to work independently, a course can be designed to give them more temporal-spatial freedom. The course could have less dialogue and be more structured, which would increase the transactional distance between educators and students. However, for other students who need dialogue to succeed in their studies, putting less emphasis on dialogue would decrease the pedagogical quality of the course.

Drawing on the literature reviewed above, a course design can be characterized by a lower or higher degree of temporal-spatial flexibility, and a lower or higher degree of pedagogical flexibility. A model is suggested that can support reflection on distance education course designs and their potential benefits and limitations (see ). The model illustrates that it is not enough to offer courses that are flexible only with regard to time, pace and place of studies. To meet the needs of students, such courses also need to be pedagogically flexible, i.e., being positioned in the first quadrant. For example, if students are not self-regulated there might be a need to provide frequent tutoring and scaffolding. Sometimes it might be decided to reduce the temporal-spatial flexibility for pedagogical reasons by providing scheduled teaching according to the fourth quadrant.

Aim and research questions

While a hallmark of flexible distance education is that it is flexible in terms of time, pace and place of study, there is a more limited understanding of the interplay between temporal-spatial and pedagogical flexibility in distance education. This study aims to investigate pedagogical flexibility in distance education characterized by a high degree of temporal-spatial flexibility. More specifically, the following research questions are addressed:

What are the pedagogical challenges in distance education characterized by a high degree of temporal-spatial flexibility?

How do distance educators navigate tensions between temporal-spatial and pedagogical flexibility?

Methodology

This study is based on the municipal adult distance education provision in six Swedish municipalities (Sw. kommuner) that participate in a three-year research and development program (2022-2025). In the Swedish Education Act, municipal adult education is described as follows:

The goal of municipal adult education is for adults to be supported and stimulated in their learning. They must be given the opportunity to develop their knowledge and competence to strengthen their position in work and social life and to promote their personal development. The starting point for the education must be the individual’s needs and conditions. Those who have received the least education must be prioritized. (SFS., Citation2010:800, our translation)

The adult education providers examined in this study are located in different parts of Sweden. Forty-six participants from the six municipalities were interviewed via a video conferencing tool in seven focus groups. One benefit of using focus groups is the potential for group interaction to produce data and insights that would not occur otherwise (Morgan, Citation1997). Homogeneous focus groups allow for free-flowing conversations among participants with similar backgrounds (Morgan, Citation1997), while heterogeneous groups can often produce more unique and creative ideas (Fern, Citation2001). Our focus groups attempted to combine the benefits of both homogeneous and heterogeneous group composition. They were homogeneous because distance educators from a particular school were included in each focus group, but they were also heterogeneous because the work experience of the educators varied greatly and they taught different school subjects. The participants were working in different parts of the adult education program: at primary and secondary levels, upper secondary level in both vocational and academic subjects, and Swedish for Immigrants (SFI).

A guide for the focus groups was constructed and contained the following topics: the history of distance education at the school, how the school is organized, being a distance educator, teaching in distance education, the educational environment and areas for development. The guide was co-constructed by the three authors. Two authors participated in each focus group. One author moderated the discussion while the other assisted by asking follow-up questions and taking notes. After each focus group, the authors reflected on the discussions during the focus group. These steps were taken as a way to ensure the quality of the research (Krueger, Citation1993; Tracy, Citation2010). Each focus group lasted between 74 and 100 minutes and included between four and eight educators. The focus groups were recorded and transcribed. The selected quotes have been translated from Swedish to English.

We conducted a theoretical thematic analysis (Braun & Clark, 2006) focusing on temporal-spatial and pedagogical flexibility in distance education. This type of analysis is driven by our research questions and provides a detailed analysis of these specific aspects of the data rather than a comprehensive description of the data as a whole. Following the six phases described by Braun and Clark (2006) the empirical material was re-read several times to get familiar with the material and to start identifying initial patterns. Then we coded how flexibility was manifested in the educational practice. The initial codes were then compiled into themes that were reviewed and discussed. During the work we engaged in joint discussions on several occasions to validate the initial codes and later the themes. During these occasions, we identified and reviewed the codes, themes and discussed how these should be presented. Furthermore, the themes – both while in development and later as presented in this article – have been presented to the participants at the research and development project’s seminars, thus providing opportunities for member reflections (Tracy, Citation2010).

The participants in this study received information about the implications of taking part in the research project. This information was communicated to them both verbally and in writing to ensure that they had the opportunity to understand the information and ask questions. The researchers stressed that participation in a focus group was voluntary and could be withdrawn at any time.

Results

Pedagogical challenges

In this section, themes describing the reasons why it is difficult to achieve pedagogical flexibility in distance education courses characterized by high temporal-spatial flexibility are described.

Continuous admission and flexible study pace

The focus group discussions revealed how courses with continuous admission can present pedagogical challenges. Educators felt they needed to be flexible with their planning “day by day” because they did not know in advance what their groups would look like.

And this group composition can change a lot in two weeks, so you kind of… Actually, it’s a bit like waiting and seeing in the morning, who will come today. Okay, today there are three … students gone. Then we have to do this. Today I have two new ones to be introduced. All my time is spent on that… (School F)

The successful working of a flexible continuous admissions policy was seen to be linked to the conditions of different school subjects. It seemed more challenging to cater for flexibility in some school subjects than in others.

I can say, in science it is a little easier because I can have that one group started after the other. Then they can jump [into] the course where the other group is and do the other one. It is very easy with certain subjects, I think, to puzzle it out … But mathematics doesn’t work that way because it is built … You pile on knowledge, so you can’t do it that way. (School D)

At some schools, students are also allowed to study at different paces. Thus, some students were studying part-time and others full-time. Within a single class students could therefore be at many different stages of knowledge development. Continuous admission combined with variable study pace made it challenging to adapt teaching to the students in the group and their individual needs. Time was simply not available to provide individual tutoring for those students who needed it.

You have several different … people who are studying over 10 weeks, 15 weeks, and 20 weeks and who have started at different times as well. So it’s a bit like trying to piece it together, and that’s what I’m still struggling with anyway, trying to get some good order on that, make it work a bit. (School D)

Unrealistic student expectations and unfavorable conditions

Many adult students request distance education studies because they think it will be easier to combine with work and/or family life. However, the educators in this study believed that students often do not have a realistic picture of the effort distance education studies require. Some students have not set aside enough time for their studies nor do they have access to a suitable study environment. For example, some adults have difficulties studying at home because of the many domestic distractions there can be. The educators highlighted that students are often not aware that distance education courses require as much work as classroom-based courses. Distance education is often designed in such a way that students need to study on their own and study without the same level of support they would get in the classroom. Some educators argued that it is easier to meet and get support from fellow students on-site. In some ways, distance education courses are actually less flexible for students because the only available means of communication is digital and is often restricted to regular office hours. The educators felt that it needed to be clearer for students what is required in distance education.

So, the students have the desire, and many want to study because they work, but it was a bit difficult to always be realistic, how much they could work and study at the same time. (School C)

Related to the challenge of unrealistic time expectations was the obstacle presented by digital competence and accessibility. Many students taking distance courses lacked basic computer skills and access to a computer. Some tried to participate using their mobile phone.

The family might have a computer, but then there might be seven or eight people who have to share it and then there won’t be much [time] left for mother. That could be a problem. The second is with internet connection, what kind of wifi do you have. So, it is something that we are still struggling with, how we should be able to … that it should be equal. (School D)

Unfavorable conditions for teaching

Many educators argued that they did not have enough time for competence development. Educators were faced with new forms of teaching, which required them to have the skills to use digital technology and teach in flexible ways. Some educators taught both conventional and distance courses in parallel but felt that they did not have sufficient time to develop the content so it fit the delivery method.

… that’s what we were told from the beginning. “No, you just run the same course plan as you run during the day, but it won’t take any more time. It shouldn’t take more time.” But what kind of distance [education] do we offer then? It is not quality, if it is not allowed to take some time. So, it’s impossible. It’s an impossible equation… (School C)

This could lead to classroom teaching “being copied” into distance education courses, although the educators wished they had enough time to create courses based on the premises of distance education.

The thing is, when a term is coming to an end, for example on a Friday… The following Monday the next term begins and that means you’re finishing a course with all that entails with retests, completions, all sorts of stuff, grading and joint assessment and everything else while planning the next course that starts the following week. And I feel that is a big problem, that we don’t have time to develop it… because we could have some type of more interactive distance learning, something else that could make it better. But when can we do it? (School C)

Often, economic conditions set the boundaries for how flexibility takes shape. Some education providers were pressured for economic reasons to adopt continuous admission and accept new students throughout the duration of a course. Such economic rationalities led some education providers to offer forms of distance education that met different student needs.

A year ago, we received a very clear demand on us, that we can’t have it this way. We can’t have so few in the classrooms… But we learned that we need to think differently, plan for a more flexible arrangement, use more of the digital and so on. And that’s what we’ve struggled with this year, I feel. To try to pick up all possible different variants and flexible arrangements and to use even more digital technology. (School D)

One of the educators summarized the competence needed to be a good distance educator:

[Y]ou need to be extremely clear and well-articulated, you need to have clear language, you need to be able to express yourself both in text and … yes, in text above all and have a sense of structure and layout and so on when preparing your digital courses and so on. You need to be able to be a bit flexible and quick-footed and be able to switch between different tasks, different students, different courses, different examinations. And I don’t know how you’re supposed to teach it, but I think these are qualities that are valuable if you want to enjoy working as a distance educator. (School G)

Flexible assessment perceived as not legally secure and time-consuming

The educators described the ways they carried out assessment. Most of them chose to conduct tests at the school even though they would have liked to have used other forms of more flexible assessment. They argued that they could not be sure who was doing the student’s homework. Several educators reflected on the dilemma that even though it is a distance education course, for them to grade in a legally secure way, tests need to be carried out on-site. Often the tests cannot be held when it suits the students but are organized based on what is possible at the school.

I’ve also had the idea myself, that as this is a distance education course, of course the students should be able to … watch short films, make submissions whenever they want, but as it’s become today, it is so incredibly difficult… It’s an exercise of legal authority to award grades, and I have to be sure… I think it’s a big challenge today when it comes to distance courses. (School B)

Another suggested that one way to conduct flexible yet secure assessment might be through requiring many small individual assessments. Cheating might be less likely if students are required to submit a number of different assignments, although marking these can be time-consuming for educators.

Those who study a course remotely, then they don’t have the opportunity to come to school to do that group work or to be part of a seminar or lecture. Then they have to do an individual assignment [in lieu] and this means that I receive 20 extra assignments from this distance learning course every week. And it doesn’t show up anywhere in my schedule, but the school management says “Yes, but you have the same course, it’s just that 20 of them are studying remotely”. (School C)

Navigating tensions between temporal-spatial and pedagogical flexibility

In this section, themes describing how distance educators attempt to achieve pedagogical flexibility in distance education courses characterized by high temporal-spatial flexibility are described.

Meeting student needs

While some distance educators argued that distance education is not appropriate for some students, others argued that distance education needs to be developed to better meet student needs.

But we need to develop a distance education mechanism for [Swedish for Immigrants] students who don’t have it, because it’s also in demand by those students who don’t have the digital competence. So, we need to find new ways, other ways, to also ensure that they can study remotely. (School G)

The educators raised questions about how they can shape a course structure and content that works for students who study within the same course but who study at different levels, have different needs or study at different paces.

Then it’s very important to develop a way to make the information flow for people who are at many different stages in a course. (School D)

Social learning

A desire among educators was to establish more interaction with students, and among them. This aspiration is linked to the fact that much of the distance education is mainly organized as independent study. More interaction was highlighted as a means to develop distance education courses that were more engaging.

And I think we could do better at making these courses more interactive and then we always need to have the student perspective in mind. “When does the student get bored? What could we do then, so that they don’t actually drop out?” (School C)

A commonly suggested way to support students is to encourage them to come to school. Then students can get support from other students at the school.

We often encourage students to go to school, to the Learning Center, if they have the opportunity, and study there. After all, they have their [study] booths to sit in during class time, but they can sit together during breaks, do homework together after our teaching hours, after twelve o’clock. And it contributes as [name] said to their social interaction with each other and integration with other students at school. (School F)

It is evident that some educators seemed to believe that distance education has to be conducted on an individual basis, while classroom teaching is more social.

When solving a problem in a whole classroom… Someone asks a question that many people share. You answer the question. Then the problem is solved instead of receiving 15 emails dealing with the same question… (School C)

However, it is possible to support social learning in a distance education context. One way would be by answering and discussing questions in a joint digital environment, such as a learning management system. However, while some educators believed that distance education courses needed to become more social others believed that social learning occurs in a classroom.

Individual tutoring

The importance of following students’ development and intervening to ensure they follow the study plan was brought up by several of the educators. They encourage students to get in touch when they need support. The educators dealt with many students who request individual guidance and support.

[S]ome say “No, but now I need … can you help me with this?” or “Can you call me?” And I think that’s actually the best way… Then there’s the problem of getting the time together, to fit together, when can I, when can the student? And so on. It’s worked well with people who are … when they’ve been at home… But for those who work, then it’s more difficult to put it together and create that relationship… (School D)

In the focus group discussions, the question of the extent to which educators should be available outside regular office hours was brought up, specifically, whether or not educators need to be available at evenings and weekends. There were different opinions. While most educators prefer to work regular weekdays and are not obliged to work evenings and weekends, because many adults study at evenings and weekends, their needs are not then flexibly met.

Flexible assessment

Although some educators argued that flexible assessment is not legally secure, others highlighted how they tried to be flexible, for example, by allowing their students to take a test when it suited them.

But now I write that “Come here and write the test whenever it suits you” … [T]he student has a plan to follow. But there is nothing that says they must follow it. I got a question the other week, “Can I take this course faster?” “Absolutely,” I said, “It’s up to you to go as fast as you want. For me, it doesn’t matter which way you do it”. (School B)

Some courses are asynchronous and based on written communication with continuous and formative assessments.

Then you become more like an administrator, almost. Sure, you can have a lot of communication with the students too, but it’s … well, it’s written communication and it’s asynchronous and … for the most part, for it to work, you probably have to like that way of working. It’s not the traditional way of teaching, perhaps, or the way many people think. When you think "I’m going to become a teacher", it’s not sitting at home and grading exams on a conveyor belt and sending e-mails to students. (School G)

Discussion

This study investigated pedagogical flexibility in distance education characterized by a high degree of temporal-spatial flexibility. Overall, the results show that educators are often obliged to solve challenges of high temporal-spatial flexibility in their teaching. A constantly changing student group means that the teacher must be prepared to continuously rethink their planning and adapt their teaching to new conditions and group configurations.

The first research question focused on identifying pedagogical challenges in distance education courses characterized by a high degree of temporal-spatial flexibility. While giving students the opportunity to enroll in a course when it suits them and study at a pace according to individual preference is a common defining characteristic of flexible distance education (Lockee & Clark-Stallkamp, Citation2022), it is evident that such flexibility contributes to a series of pedagogical challenges. For educators, it is stressful to constantly revise their teaching when students continuously enroll in a course. While this might be easier to accommodate in asynchronous distance education, students who are not self-regulated might require synchronous teaching (Lockee & Clark-Stallkamp, Citation2022). Thus, in some courses, it might be advisable to reduce temporal or even spatial flexibility by offering scheduled, cohort-based teaching. The educators argue that it is more manageable to accommodate continuous admission and flexible study paces in subject disciplines that are not dependent on sequencing education activities in a particular order.

The findings suggest that there is a tension between the design of distance education courses and student expectations. On the one hand, some distance education courses are not designed in ways that meet student preferences or needs. The educators argue that, for students who need to study independently, they cannot get as much support as they would in a conventional classroom setting. These educators believe that it is not possible to design distance education for student interaction despite the fact that such interaction has been a key part of the distance education literature for decades (Moore, Citation1989). On the other hand, many students prefer flexible distance over conventional education because of their lack of time, even though it is well known that studying of any kind puts considerable demands on students (Houlden & Veletsianos, Citation2019; Samarawickrema, Citation2005). Other problems students have with flexible distance learning is an appropriate home study environment, access to a computer and sufficient computer skills. Some education providers try to tackle these issues by offering study spaces at school, access to computers and computer courses. However, many students, even those who might benefit the most, do not take advantage of such opportunities.

Many educators teach both classroom-based and distance courses but feel they lack the necessary time or competence to teach effectively in a distance education setting. Some education providers regularly develop new flexible distance education formats to meet student preferences and needs. The educators find it challenging to keep up with these developments. Paradoxically, distance education seems to have pushed some adult educators in a more conservative direction regarding assessment. This might be related to the stressful nature of their work environment. Continuous admission, self-directed pace and a lack of time means few opportunities to get to know students in person and engage in more time-consuming formative assessments. These findings emphasize the need to develop and prepare educators for the professional role of being a distance educator (Moore, Citation2001) and to provide them with work conditions in line with the demand for developing and coping with pedagogical flexibility.

The second research question focused on how distance educators navigate tensions between temporal-spatial and pedagogical flexibility. Some educators argued that distance education needs to better meet student needs. Examples include providing teaching at evenings and weekends and efforts to manage communication with students at different levels, with different needs and studying at different paces. Some educators encourage students to study together, often by encouraging them to come to school. However, many of the adult educators seemed to feel that it is not possible to combine more social learning and temporal-spatial flexibility.

Another way to offer pedagogical flexibility is to provide individual tutoring, although some educators seem to wait for students to get in touch first, rather than proactively initiating contact with them. Other educators are aware that some students who need help do not get in touch. This relationship is made additionally complicated when students request help when the educator is not available, like at evenings and weekends. There seems to be differences of opinion among educators about their availability outside of regular working hours. Education providers and the educators they employ could come to an agreement about the amount of time they have to offer individual tutoring, which this time might be available, and how to communicate this clearly to students. If there are discrepancies within and between education providers, there is a risk that not all students will be provided with equitable and high quality education, a requirement of the Swedish Education Act (SFS., Citation2010:800). As noted above, some educators worry that online assignments and examinations are not legally secure and insist upon in-person assessment forms. However, some educators still attempt to maintain flexibility by, for example, allowing students to do tests at school, to create their own deadlines, or by conducting frequent assessments, which can be assumed to reduce the risk of cheating. However, this means that educators spend considerable time grading assessments rather than teaching and communicating with students.

Further research and implications for practice

This study was conducted in a Swedish setting offering municipal adult distance education at primary and secondary school levels. Further research is suggested to explore the relationship between temporal-spatial and pedagogical flexibility in other settings. There is a need to further explore different dimensions of flexibility in distance education. As a starting point, Veletsianos and Houlden (Citation2019) suggest future research might ask the following questions:

What aspects of education can be made more flexible, and how can they be made more flexible? Which ones benefit learners the most? Who benefits from further flexibility and why? What are the limits of flexibility? Is flexibility the future of educational provision as emerging narratives suggest? To what degree [do] current instructional design models fit with providing flexible approaches to education? (p. 462).

Revisiting the model of temporal-spatial and pedagogical flexibility

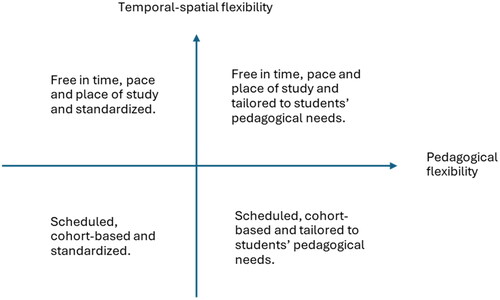

To conclude, the model of temporal-spatial and pedagogical flexibility that was suggested previously is revisited (see ). Examples are provided to illustrate how different distance education configurations relate to temporal-spatial and pedagogical flexibility. Scheduled, cohort-based and standardized distance education is characterized by low temporal-spatial and low pedagogical flexibility. This configuration can be illustrated by scheduled video conference teaching in which educators make limited attempts to adapt their teaching to the particular and continuously varying needs of students. This approach is similar to the emergency remote teaching that was common during the COVID pandemic (Hodges et al., Citation2020).

Figure 2. Examples of distance education course designs in relation to temporal-spatial and pedagogical flexibility.

Distance education that is free in time, pace and place of study and standardized is characterized by high temporal-spatial and low pedagogical flexibility. A typical example is asynchronous distance education based on independent study and a one-size-fits-all course model. This approach can be suitable for self-directed students (Lockee & Clark-Stallkamp, Citation2022) but not for those who need extra help or prefer interaction with educators or other students (Moore, Citation1997).

Distance education that is scheduled, cohort-based and tailored to students’ pedagogical needs is characterized by low temporal-spatial and high pedagogical flexibility. Such distance education might include synchronous video conference teaching with a schedule that students are required to follow. The educator can achieve pedagogical flexibility by regularly adapting the teaching based on students’ needs. The flipped classroom model is a good example of this approach, where scheduled teaching is commonly adapted to focus on what students find challenging (Van Alten et al., Citation2019).

Finally, distance education that is free in time, pace and place of study and tailored to students’ pedagogical needs is characterized by high temporal-spatial and high pedagogical flexibility. One example is asynchronous distance education where teaching material is adapted to the needs of the student and in which opportunities for individual tutoring and collaborative learning with peers are provided in flexible ways (Paulsen, Citation1992).

This proposed model of temporal-spatial and pedagogical flexibility contributes to the growing awareness that flexibility in distance education is a complex and nuanced concept. This model can be used both in practice and in further research when analyzing and developing flexible distance education designs. Most importantly, it implies that there is not one ‘ideal’ type of flexibility in distance education. Both spatial-temporal and pedagogical flexibility need to be considered when trying to meet student needs and balance them with the practical constraints that educators and education providers are facing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data used in the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Stefan Hrastinski

Stefan Hrastinski is a professor at the Division of Digital Learning, KTH Royal Institute of Technology. His research interests include emerging methods and technologies for learning, online collaborative learning, distance education and education futures.

Enni Paul

Enni Paul is a senior lecturer at the Department of Education, Stockholm University. Her research interests concern students with migration background(-s), their experience of language learning, and afforded opportunities in different educational contexts.

Anna Åkerfeldt

Anna Åkerfeldt is a researcher at the Department of Teaching and Learning, Stockholm University. Her research interests are learning and teaching with technologies, more specifically online learning, assessment of multimodal representations and computational thinking.

References

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brewer, S. A., & Yucedag-Ozcan, A. (2013). Educational persistence: Self-efficacy and topics in a college orientation course. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 14(4), 451–465. https://doi.org/10.2190/CS.14.4.b

- Chen, D.-T. (2003). Uncovering the provisos behind flexible learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 6(2), 25–30. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/jeductechsoci.6.2.25.pdf

- Collis, B. (1998). New didactics in university instruction: why and how. Computers & Education, 31(4), 373–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-1315(98)00040-2

- Collis, B., & Moonen, J. (2002). Flexible learning in a digital world. Open learning. The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 17(3), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268051022000048228

- Dalsgaard, C., & Paulsen, M. F. (2009). Transparency in cooperative online education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(3). Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v10i3.671

- Fern, E. F. (2001). Advanced focus group research. Sage.

- Gärdén, C. (2010). Verktyg för lärande: informationssökning och informationsanvändning i kommunal vuxenutbildning [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Borås and Gothenburg University.

- Hodges, C. B., Moore, S., Lockee, B. B., Trust, T., & Bond, M. A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

- Holmqvist, D., Fejes, A., & Nylander, E. (2021). Auctioning out education: On exogenous privatization through public procurement. European Educational Research Journal, 20(1), 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904120953281

- Houlden, S., & Veletsianos, G. (2019). A posthumanist critique of flexible online learning and its “anytime anyplace” claims. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(3), 1005–1018. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12779

- Houlden, S., & Veletsianos, G. (2021). The problem with flexible learning: Neoliberalism, freedom, and learner subjectivities. Learning, Media and Technology, 46(2), 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1833920

- James, R., & Beattie, K. (1996). Postgraduate coursework beyond the classroom: Issues in implementing flexible delivery. Distance Education, 17(2), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158791960170209

- Krueger, R. (1993). Quality control in focus group research. In: D. L. Morgan (Ed.), Successful Focus Groups: Advancing the State of the Art (pp. 65–86). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483349008

- Lockee, B. B., & Clark-Stallkamp, R. (2022). Pressure on the system: Increasing flexible learning through distance education. Distance Education, 43(2), 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2022.2064829

- Moore, M. G. (1989). Editorial: Three types of interaction. American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923648909526659

- Moore, M. G. (1997). Theory of transactional distance. In D. Keegan (Ed.), Theoretical Principles of Distance Education (pp. 22–38). Routledge.

- Moore, M. G. (2001). Editorial: Surviving as a distance teacher. American Journal of Distance Education, 15(2), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923640109527080

- Morgan, D. L. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research. Sage.

- Mufic, J. (2023). ‘And suddenly it’s not so flexible anymore!’ Discursive effects in comments from school leaders and staff about distance education. Studies in the Education of Adults, 56(1), 102–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2023.2249141

- Muhrman, K., & Andersson, P. (2022). Adult education in Sweden in the wake of marketisation. Studies in the Education of Adults, 54(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2021.1984060

- Naidu, S. (2017). Openness and flexibility are the norm, but what are the challenges? Distance Education, 38(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2017.1297185

- Naidu, S. (1997). Collaborative reflective practice: An instructional design architecture for the internet. Distance Education, 18(2), 257–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158791970180206

- Paulsen, M. F. (1992). From bulletin boards to electronic universities: Distance education, computer-mediated communication, and online education. The American Center for the Study of Distance Education, Pennsylvania State University.

- Samarawickrema, R. G. (2005). Determinants of student readiness for flexible learning: Some preliminary findings. Distance Education, 26(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910500081277

- SFS. (2010:800). Skollag [Education act]. Utbildningsdepartementet [Ministry of Education]. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800/

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2017). Läroplan för vuxenutbildningen [Curriculum for adult education]. https://www.skolverket.se/undervisning/vuxenutbildningen/komvux-gymnasial/laroplan-for-vux-och-amnesplaner-for-komvux-gymnasial/laroplan-lvux12-for-vuxenutbildningen

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- Valcke, M. M. A., & Martens, R. L. (1997). An interactive learning and course development environment: Context, theoretical and empirical considerations. Distance Education, 18(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158791970180103

- Van Alten, D. C., Phielix, C., Janssen, J., & Kester, L. (2019). Effects of flipping the classroom on learning outcomes and satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 28, 100281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.05.003

- Veletsianos, G., & Houlden, S. (2019). An analysis of flexible learning and flexibility over the last 40 years of Distance Education. Distance Education, 40(4), 454–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2019.1681893