ABSTRACT

This article considers relations between inheritance, disobedience and speculation in art practice and art education in schools and other sites of teaching and learning. In recent decades educational practices such locations have been subject to doctrinal cultures of audit, standardisation and competences, invoking what Michael Hampe terms the homogenization of the interpretation of experience. In contrast the article advocates the idea of speculative pedagogies that remain open to the unknown potentialities of students’ and teachers’ learning encounters and invent a future when such a future, demands thought. Speculative practice and the idea of disobedience are elaborated through contemporary art practices, then applied to pedagogical contexts and processes of learning. Focusing upon the relevance of how a learning encounter matters for a student and the obligations required of a teacher, the article then considers an ethics and politics of pedagogical work through the idea of idiotic events and Isabelle Stengers’ notion of the cosmopolitical proposal.

Introduction

In educational contexts such as schools in recent decades there has been an increasing shift towards the centralisation and standardisation of knowledge and practice; this includes modes of assessment, competences, standards, teaching methodologies and, in many countries, the regimentation of teacher education. These have become prescribed entities and processes that have defined educational policy in our epoch. Such stipulation constitutes a rigorous doctrinal attitude to impose uniformity upon the purpose of education and its pedagogical processes. These processes of standardisation can be equated with the forces of professionalisation, of professional method. Whitehead (Citation1997) referred to the development of professional method as the ‘training of minds in a groove’ (p. 205). Isabelle Stengers (Citation2014) makes the point that what was new in the development of professional training, to which Whitehead referred, was the fact that it became synonymous with the idea of progress and improvement. Stengers argues that, ‘The method produces not routine minds but inventive, entrepreneurial, conquering ones’ (p. 197) – a kind of colonising of knowledge and practice. Harney and Moten (Citation2013) in their text The Undercommons, writing from the context of the radical Black tradition, inquire into the process whereby professionalisation brings with it a negligence of that which lies outside or beyond. And what lies outside, for example, can be equated with those singularities of experience in a learning encounter that become subsumed under the umbrella of measurement and quantification and flattened according to its register.

The push for standardisation and comparison in the form of competency criteria, for example, presupposes a pedagogy of the known and its normative inheritance. In contrast, I want to advocate the notion of speculative pedagogies that are not controlled by the ground of pre-established templates of knowledge, values and pedagogical expectations that lead to already specified endpoints. Such pedagogies, also advocated by Kuby and Christ (Citation2020), Carstens (Citation2020) and others, would adopt a more open, less prescribed approach to respond to the different and singular ways in which students learn, to their different relational proclivities, aptitudes, aspirations, dispositions, values and interests. We might say that speculative pedagogies are more ‘reactive’, responsive, generative or improvisational in relation to how something in a learning encounter matters for a learner and how the potentialities of such mattering can be developed. Speculative pedagogies therefore evoke what Susan Buck-Morss (Citation2010) terms a pragmatics of the suddenly possible, which I would like to extend to a politics, ethics and aesthetics of the suddenly possible. I want to consider speculative pedagogies therefore in relation to the notion of inheritance, that is to say the values and traditions of practice that form the established grounds of practice, that are inherited and which ‘inform’ practice. But I also want to consider the notion of inheritance in relation to that which disturbs or which is disobedient to its ground, in other words how we might inherit that which disturbs and which may lead to an expansion or transformation of practice.

Inheritance

In pedagogic work how do we inherit the art practices of children and older students? How is this inheriting structured, according to what criteria, what values? How do we inherit these practices when they cannot be accommodated or homogenised within, and thus consequently disturb established frameworks of understanding? The latter question of inheritance is not uncommon when we are confronted with some contemporary art practices that challenge understanding or even provoke bewilderment; that appear heterogeneous to our frameworks of understanding. I am using the notion of inheritance in two ways – first, in relation to events or entities that we are able to assimilate through established values and criteria, and second, in relation to events that cannot be assimilated or that disturb our frameworks of comprehension. How do we then inherit the disturbance? And how does inheriting the disturbance then change the ground it disturbs? I am using the notion of inheritance in this latter sense therefore not to refer to a simple act of reception but to those affective, cognitive, practical or other frameworks, that facilitate (or do not) how we receive, how we inherit something that does not fit.

As a humorous aside, I am reminded of a comedy sketch by the English comedy duo, Morecombe and Wise who are joined by the internationally renowned pianist and composer Andre Previn. Previn is conducting the orchestra to play Grieg’s piano concerto and Eric Morecombe is at the piano. After a bit of fooling around Previn eventually calls the orchestra to attention and they begin the concerto. When it is Morecombe’s time to come in on the piano, he plays a series of jumbled and incoherent notes. Previn stops the orchestra immediately and looks towards the pianist in astonishment. Mystified, he walks over to Morecombe and asks what on earth he is playing, the latter replies ‘Grieg’s Piano Concerto’. ‘But’, says Previn, ‘you are playing all the wrong notes!’ Morecombe taking great offence stands up and grabs hold of Previn’s coat lapels so that they are nose to nose, and says ‘No! I am playing the right notes but not necessarily in the right order!’

Such questions concerning inheritance seem important today in a pedagogical context in which inheritance, that is to say how we inherit children’s or older students’ work, has already been decided by government in some countries by the establishment of national standards and competences. These relate to national curricula or to international standards of assessment as demonstrated by PISA. This seems close to the idea of homogenisation, the homogenisation of knowledge.

We can also witness what the German philosopher, Michael Hampe (Citation2018) calls homogenizing the interpretation of experience (p. 14) in philosophical, pedagogical and other kinds of discourses that construct general schemas of concepts to capture concrete experience in order to produce a system of understanding. Even though such schemas, like that, for example, developed by Alfred North Whitehead who invented a series of concepts to describe processes of becoming, admit that fallibility and revision are part of the process. As Hampe states, ‘the need for a system arises whenever the world’s particulars apparently do not of themselves amount to a sufficient coherence or where this coherence appears to be unclear’ (p. 14). Such constructions can lead to the formation of a grand or transcendent narrative through a unified or unifying terminology, but then, Hampe asks, ‘why should many experiencing subjects try or be expected to understand their experiences (or those of others) in one single (transcendent) language?’ (p. 15, my brackets).

I remember many years ago my struggles with Piagetian ‘stages of development’, a discourse that formulated general schemas of development which was applied to a range of practices including drawing. Though one could detect general schemas or syntactical structures in children’s drawings, for me the developmental stages discourse failed to engage with the semantics of a child’s drawing practices, how a drawing mattered for a child in its specific context of production. In Europe currently there exists an international network for visual literacy (ENVIL) to construct a series of generic competencies in visual literacy education for school students studying art and design. Such competencies aim to develop understanding of how images are produced and received in order to improve social cohesion, civic engagement, personal unfolding and employability. But do the conceptual and practical frameworks that are established by such competencies totalise or territorialise practice, so that modes of practice, understanding, and the affective flows that animate and inflect them, and which ‘do not fit’, are marginalised or go unnoticed? We might ask this question more generally in the field of education in which competencies or standards have become benchmarks through which to define practice and ascertain its levels/abilities. What other kinds of competencies and their affective/cognitive/embodied materialities exist beyond or before the standardised competencies?

The interpretation of experience through a particular conceptual, philosophical, scientific or pedagogical system constitutes therefore a transcendent form of inheritance and it becomes doctrinal when priority is given to the conceptualising structures that act as a hylomorphic forming of experience. This is one manifestation of the practice that Whitehead (Citation1997) called the fallacy of misplaced concreteness (p. 52). Whitehead was referring to the use of conceptual abstractions that become substituted for concrete or real events or entities or, put simply, the mistaking of models for reality. We require abstractions for the process of inquiry, abstractions vectorise experience, but we have to try to be conscious of their limitations; to civilise our abstractions. One consequence of the fallacy is that we inquire and live with ‘inadequate abstractions and insufficient concreteness’ (see Thompson, Citation1997, p. 221). Concreteness for Whitehead refers to the immediacy and fullness of what is uniquely individual, the particularity of experiencing, of an actual occasion or situation composed of actual and virtual flows. Another aspect of the fallacy is that though we gain some security through abstractions or territorialisations, their hardening and rigidifying forces can inhibit sensibilities to the cost of neglecting responsibility and openness towards ‘other’ sensoriums of affects and intensities of experiencing, that in an important sense nourish us. Put differently, such hardening forces may prevent us from receiving the gift of otherness (Atkinson, Citationforthcoming). For Stengers (Citation2005b) the notion of cosmos refers to the unknown as constituted by divergent worlds, divergent sensoriums we might say, and what they may be capable of. Taking this idea of cosmos on board, along with an openness towards its divergences and potentials, what I have called elsewhere a pedagogy of ‘taking care’ (Atkinson, Citationforthcoming) demands that pedagogic work requires an acute vigilance towards the inevitability of pedagogic prejudices that perpetuate particular values, practices and traditions that may occlude or marginalise those practices that ‘do not fit’.

However, if we are able to avoid such prejudices and attend to and inherit from the particularity of a disturbance, emerging from the immanence of a learner’s situated specificity of practice and which does not fit our interpretational frameworks, if we can enter into a critical dialogue with the way in which we frame our experiences, we may be able to reconfigure or invent new modes of interpretational practices that invoke ethical, political and aesthetic reconfigurations that expand our capacities to think and act. (Another way of putting this might be to think of such disturbances leading to a reconfiguring of affective and cognitive cartographies of experiencing in pedagogic practice.)

The point of raising this issue of inheritance concerns trying to develop pedagogical discourses and practices that try to engage with and inherit the different ways in which children and students learn not by beginning with established/inherited narratives from which to interpret but, as far as one can, from the local functioning realities of each student. This approach might fit with the idea of pedagogical practice developing what Joe Gerlach (Citation2014) calls an ontogenesis of ‘vernacular mapping’:

Vernacular mappings are cartographies that in their ethos and practice are more vulnerable and susceptible to change and perturbation; cartographies that perform the unsettling of epistemological and representational certainties while affirming spaces for inhabiting and navigating the world otherwise. (p. 31)

Is it possible to engage with what we might call the ‘vernacular immanence’ of a learner’s practice so as to make such immanence accessible? I use the term immanence to refer to local relations and values of modes of existence, to those flows of experiencing through which someone makes sense, conceives, feels or develops particular capacities to act. I will come back to this notion in relation to the idea of local ecologies of practice. Obviously a teacher initiating learning encounters with his or her students will proceed from particular practices (drawing, painting, 3D work, video, performance, collage, printmaking, digital) to tackle the encounter, but the pedagogical task, from a non-doctrinal perspective, ‘without criteria’ (Shaviro, Citation2009) would be to try to engage with how a particular learning encounter matters for a learner in his or her situated specificity of learning and how this mattering becomes inherited by the teacher. Equally, extending this point on inheritance in the context of art and design education, how might teachers adjust their pedagogical practices through their inheritance of the disturbance of new forms of art practice, that in turn, disturbs how such practice is understood?

The pedagogical approach that I want to advocate is what can be termed speculative pedagogy. Speculative pedagogies try to avoid homogenising the interpretation of experience in pedagogical work by attempting to work from the immanence of a learning encounter as experienced within the situated specificity of events of learning. In attempting this an aesthetics, ethics and politics of speculative pedagogy attempts to avoid transcendent forms of assessment, evaluation or other discourses that homogenise the interpretation of experience and try to engage with or ‘invent’ narratives which reflect the diversity of situated specificities of learning encounters that demand immanent evaluations (ethics) and experimentations or speculations. The notion of the situated specificity of learning encounters does not refer to ‘situated knowledge’, an important term developed by Donna Haraway (Citation1988) and others, but to a more fundamental domain, prior to knowledge, of (relational) affects that are engendered (or not) by an encounter and which may precipitate new or modified modes (rhythms) of practice (which includes thinking) that lead to new or modified knowledge. Deleuze (Citation2004) expresses this affective domain that is prior to thought through the idea of encounter, ‘something in the world forces us to think. This something is an object not of recognition but of a fundamental encounter’ (p. 176). How might pedagogic work engage with these flows and ecologies of affect that compose how an encounter matters for a learner? And how might we try to maximise their potentials for study and practice? Such questions seem almost entirely absent from current ‘thinking’ about pedagogical practice as set out by government policy. The idea of encounter about which Deleuze writes can be witnessed in encounters with participatory art practices though it is not exclusive to them.

Participatory art practices, disobedience and the force of art

Since the rise of conceptual art in the 1960s and 1970s, and tracing back to Duchamp we have seen art practice mutate into practices or encounters that are often difficult to differentiate from everyday social situations. Joseph Beuys’ Bureau for Direct Democracy at Documenta 5 in Kassel 1972, where he discussed political and other matters with the public, can be viewed as an organised encounter to generate feeling, thinking and linguistic expression. This practice of connecting with others on both conceptual and emotional planes in open debate was, for Beuys, both a political and artistic encounter in which language is viewed as a kind of sculptural medium that might contribute to forming new relations that initiate social change. Here the boundaries between art and everyday reality seem to disappear as such, the two morph into each other. The key point, as we know, is that art practice is always expanding the boundaries of what constitutes art even to the point, in some practices, where art seems to disappear. We know that some artists produce works that challenge our hermeneutic frameworks of understanding of art practice, of what it is to be an artist, of what constitutes an art work, of what it is to be a spectator. We might say that in such encounters the vital force of art practice constitutes a kind of affective disobedience, resisting and reforming previous conceptions of practice, a disobedience that testifies to the versatility, plasticity and inventiveness for reconceiving and reconfiguring established modes and conceptualisations of practice. In a similar sense can we think about pedagogic encounters as events through which pedagogic practice continually expands the boundaries of what constitutes pedagogic work?

One art practice that has informed my thinking along these lines is the Rogue Game, a project developed by the Turkish artist Can Altay (Citation2014) in collaboration with Sophie Warren and Jonathan Mosley from Spike Island in Bristol. I often use this project to reflect upon the uncertainty of how to proceed effectively in situations where our established parameters and ecologies of practice seem to fail us. Rogue Game raises for me a number of issues including: the tensionalities between the known and the not-known, identity, the tactics, politics and ethics of becoming-with. The work takes place in a sports centre, outside area or a gallery, where the markings that designate different games such as badminton, basketball, or five-a-side soccer overlap. Participants for three or four games are asked to play their respective game simultaneously on the overlapping game areas. They have to negotiate playing their game while trying to manage interruptions and interventions from the other games that inevitably invade their territory, this management of disruption constitutes the Rogue Game.

Each game abides by its rules and habits of practice through which player identities are constituted. Each game is prescribed by a designated playing area that regulates the space of play. In the Rogue Game however players also need to respond to the intermittent disruptions from other games. Thus, in the Rogue Game, players’ identities are less well defined, there are no rules or conventions. Players’ habits are disrupted, their identities become reconfigured according to the new relationalities and tactics that emerge as the Rogue Game develops. The Rogue Game forces constant territorialisings and reterritorialisations of practice; it involves collisions and negotiations of space and rules, whereby the games interweave. It is as though new rhythms of play emerge and re-configure through shifting corporeal and incorporeal materialities, those relations of bodies, flows of sense and virtual potentials that make it possible to view the playing area according to new horizons of playing together. As Can Altay (Citation2014) states, ‘Rogue Game posits the struggle of a “social body” within a set of boundaries that are being challenged’ (p. 208). To be a player in the milieu of the Rogue Game is to learn how to become in a rather uncertain world of becoming, where individual (psychic) and social becomings are entwined, where the relations between ‘I’ and ‘we’ are precarious and constantly being renegotiated but also where the horizons of cohabitation may be expanded. Subjectivity is therefore composed of a flux of evolving relational affects and dispositions as they emerge in the haecceities of practice.

The pedagogical aspect of Rogue Game concerning its dissensual dynamics, a term from Jacques Ranciere (Citation2010) referring to the rupturing of frameworks of understanding and representation, whereby heterogeneous games collide in the same space, might encourage us to reflect upon the architectures, divisions, regulations and boundaries of pedagogical spaces. To consider the ‘rules and relations of existence’ that regulate and legitimate particular epistemologies and ontologies. In education the ‘games’ or dispositifs, of subject discourses and practices and their specific organisation and regulation of knowledge, can be contrasted with the collection of heterogeneous ontological worlds of students and their respective ways of thinking, feeling, seeing and doing. The homogeneous organisation of knowledge and curriculum content can be contrasted with the heterogeneity of the living realities of students. In passing, we might wish to consider a pedagogical site according to what De La Cadena and Blaser (Citation2018) call an Uncommons, a heterogeneous collective that values working together whilst respecting difference (p. 18).

What interests me in the artifice of Rogue Game are the evolving issues of relevance and obligation for each player as a player within an evolving milieu, in which the idea of practice or of a player mutates or changes. We might draw some parallels here with the dynamics of classroom or studio practice and how what it means to be a teacher or a learner changes as issues of relevance and obligation change. (This of course brings in the notion of a subject as an on-going composition of forces and relations rather than the idea of a unified and autonomous self). I am thinking of the relevance a learning encounter has for a learner and how teachers inherit this relevance, how they are obligated to it. The art project Rogue Game is concerned with what Donna Haraway (Citation2016) calls staying with the trouble and trying to develop ‘sym-poiesis’, a making-with; trying to cope with and respond to events of disobedience, that which is unexpected, that which runs counter to established framings of experience in particular situations, but also that which may open up a potential for new modes of practice and social engagement. New modes that will develop their own forms of obedience which in turn become challenged.Footnote1

Speculative pedagogies

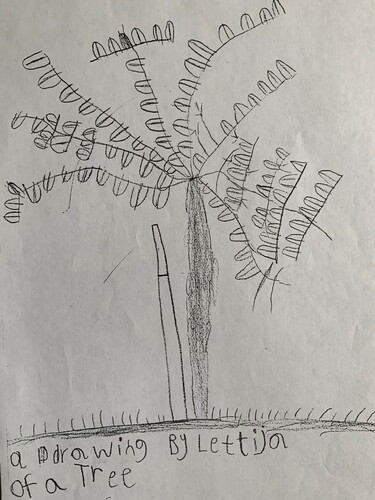

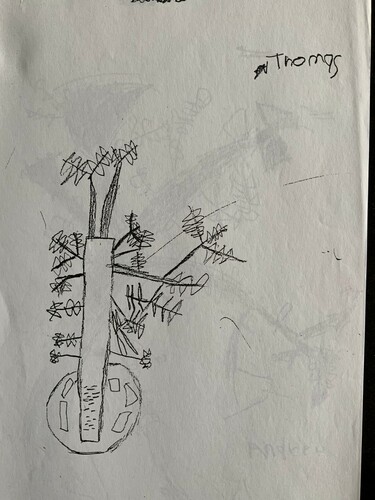

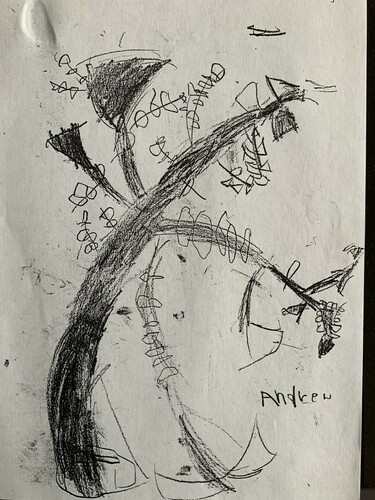

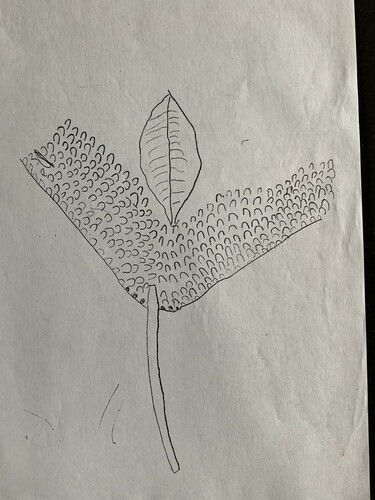

Can we use the idea of disobedient events, of art’s affective force of disobedience to engender feeling and thought in order to reflect on this notion in the context of pedagogic work in art? Or other domains of education where we can sometimes experience processes of learning that lie beyond established grammars or logics of practice and comprehension? In other words, although such processes are not, on the student’s or child’s behalf intentionally disobedient, they are disobedient to the pedagogical parameters of a teacher’s understanding. Children’s drawing practices is one domain of practice where this point was brought home to me. In this context we might view the event of disobedience for a teacher confronted by a child’s drawing that ‘does not fit’ his or her parameters, engendering or precipitating (but not always), a possible transformation of the learner and the teacher. An important contention therefore is that the ‘disobedient’ form that confronts a teacher is immanent to the ethology and ecology of a student’s events of learning. And such events that might lead to the building of a life may not ‘respond’ to established parameters because such parameters will ‘miss’ the event. Let me try to give an illustration of what I mean here by considering some drawings made by six year old children who were discussing with their teacher the structure of trees as they observed them in their playground. Without going into the individual semiotic differences, semiotic technologies, of the visual graphemes of each drawing, which are important and constitute value for the child, the first three drawings, although quite different could be said to depict what we might call a prototypical tree form in terms of our everyday view of trees (). An interpretation subject to the force of hylomorphism. The fourth drawing however seems to be disobedient to this prototypicality. And yet if we think about the idea of structure that the children are asked to depict then we might see this drawing as legitimate, in that we can interpret the notion of structure according to a different logic, a different disposition, to that with which we interpret the other drawings. It is not a drawing depicting a view but perhaps we might see it as emerging from the child-tree-drawing relation, as a ‘percept’, as described by Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1994, p. 169); a creative abstraction or individuation from the temporal flows of perception. The hylomorphic logic used to interpret the first three drawings, variations on a prototypical view (a kind of transcendent arbiter) can easily discard the relevance of the fourth drawing for its maker.

Having made this reading I might then retrace my steps by abandoning any notion of prototypicality or hylomorphic modelling and then view each drawing through Deleuze and Guattari’s (Citation1988) notion of the ritornello (p. 311). Ritornellos concern initial processes of territorialisation, of structuring a world through modes of expressivity that compose a becoming-with a world; the creation of manners that facilitate a capacity for practice. In each of the drawings discussed we might view their local graphic schemas and forms of composition as a territorialising process: an evolving aesthetic compositional holding together of a world, a holding that is always open to new or modified territorialisings. The task then for the teacher is to try to become attuned to the worlding process of the ritornellos, the immanent infrastucturings of each drawing … not to analyse ‘according to’ but to ‘compose with’ or be attuned to how the process of worlding takes shape. Different infrastructures of sensing, of practice, might be viewed as emerging from unformed (preindividual) circumstantial clouds or envelopes of experiencing … a cloud of conditions that might precipitate new individuations.

Stengers (Citation2011) idea of practice argues against the imposition of a ‘comparative’ criterion that is applied across practices so as to define practice. For Stengers, practice ‘denotes any form of life that is bound to be destroyed by the imperative of comparison and the imposition of a standard ensuring equivalency, because what makes each practice exist is also what makes it diverge’ (p. 59). Each practice has its distinct way of paying ‘due attention’ to how something matters, each practice has its own line of divergence.

Divergence is not between practices; it is not relational. It is constitutive. A practice does not define itself in terms of its divergence from others. Each does have its own positive and distinct way of paying due attention; that is, of having things and situations matter. Each produces its own line of divergence, as it likewise produces itself. (p. 59)

Taking a more provocative and speculative stance, in contrast to these regulatory forces and the imposition of competences or standards, can we view the practice of pedagogic work as a process of adventure? Can we conceive it as a process of experimentation without criteria, that attempts to draw alongside the immanence and difference of ways in which learners learn, some of which often lie beyond or are disobedient to our established parameters of pedagogic and artistic practice? It seems to me that the challenge when facing such uncertainty is to view it as an opportunity to experiment, to try to develop what I have called pedagogies against the state, that is to say the state of being, the state of knowledge and the state of political control (Atkinson, Citation2011). Another way of conceiving this is to think of such pedagogies as speculative pedagogies – speculative in terms of adopting an experimental mode of practice/thinking that through the invention of imaginative propositions seeks to challenge and thus create a transformation of a learner’s (and thus a teacher’s) experience. In other words, speculative pedagogies in the form of imaginative and experimental propositions or questions (propositioning) aiming to construct a future whose efficacy and relevance will have to be negotiated. We can think of speculation as a kind of wager, propositioning or mode of questioning on an unfinished present whose potential is the invention of strategies, operations or ideas, that are capable of provoking in a child, student or teacher, a transition into a future and into novel situations.

Without directly contradicting the idea of a pedagogy ‘without criteria’, a valuable guiding light to such a speculative pedagogy might be to adopt as a pedagogical imperative the advice given by Alfred North Whitehead (Citation1938) from his last book Modes of Thought:

Our enjoyment of actuality is a realization of worth, good or bad. It is a value experience. Its basic expression is – Have a care, here is something that matters! Yes – that is the best phrase – the primary glimmering of consciousness reveals, something that matters. (p. 116, emphasis added)

As mentioned earlier, I am not speaking here about ‘situated knowledge’ as developed by Donna Haraway and in education by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger (Citation1990) and others. The idea of the situated specificity of learning refers to relationalities that arise prior to knowledge, relationalities that generate an ecology of affects and feelings or ‘matterings’ prior to the formation of knowledge. This would constitute what we might call a sensing, perhaps a germinal speculating, emerging within learning encounters that precedes and exceeds cognition. In other words, when directed at practices of learning and teaching these questions about mattering are concerned with local etho-ecologies of practice, their ethos (the way of behaving of a particular being) and oikos (the habitat of that being and the way in which the habitat satisfies or opposes the demands associated with the ethos, or affords an ethos to risk itself). In his Ethics, Part III, proposition II, Spinoza (Citation1996) intimated that, We don’t know what a being is capable of or can become capable, he writes, ‘For indeed, no one has yet determined what a body can do’. We might view a learning encounter as a ‘proposition’ that confronts the etho-ecology of each learner and, therefore, pedagogic work demands a thinking, feeling, experimenting ‘in the presence’ of such ecologies (Stengers, Citation2005b).

This raises the point I mentioned in my introduction from Michael Hampe (Citation2018) concerning homogenizing the interpretation of experience in discourses that construct general schemas or concepts to capture concrete experience in order to produce a system of understanding. The interpretation of a learner’s experience through a particular pedagogical system constitutes therefore a transcendent form of inheritance which might be considered dogmatic if priority is given to the conceptualising structures that act as a hylomorphic forming of experience. However, if we can set aside this form of inheritance and attend to and inherit instead those disturbances, those experiences, those differences, that do not fit our interpretational frameworks, or/and if we can enter into a critical dialogue with the way in which we frame our experiences, we may be able to reconfigure or invent new, perhaps more insightful modes of interpretational practices that invoke ethical, political and aesthetic reconfigurations.

But speculative practice, or to borrow a term from Martin Savransky (Citation2017), ‘speculative pragmatism’ (p. 32), involves more than critical reflection in that, it requires a speculative sensibility, which, on encountering or feeling a problem, or feeling a need to comprehend a situation in more depth, attempts to cultivate imaginative propositions that invoke a future which itself depends upon the propositions that can be constructed for it. Savransky states: ‘Speculative pragmatism, then, designates an experimental mode of harnessing experience such that new intelligent connections among things may become possible’ (p. 30). We can view speculative thought therefore as a ‘pragmatics of thought’ where thought invents a future when such a future, that of a student’s learning encounter or a teacher’s practice, demands thought. To speculate is therefore to make a wager on the incompleteness or the uncertainties of the present based upon what confronts us, the material for speculation, a wager that detects a possibility for creative experimentation and transformation.

Though it is important for pedagogical practices to introduce learners to established forms of practice and knowledge that constitute the ‘known world’, how such traditions are inherited and iterated by students suggests that both students and teachers are viewed as both critical inquirers and speculative innovators enabling potentials for a world to come, a world that is not yet known and which cannot, in the didactic sense of prescription, be fully controlled or predicted, nor fully accommodated by established orders.

Ecology of practices

I turn now to consider some of the above points through the idea of an ecology of practices in the work of Isabelle Stengers (Citation2005a). She uses this term as a tool for inquiry, a tool to make us think and explore what might be happening in a specific situation, particularly when confronted with something that does not fit, but also as a device not to take things for granted. She writes:

Approaching a practice means approaching it as it diverges, that is, feeling its borders, experimenting with questions which practitioners may accept as relevant, even if they are not their own questions … rather than posing questions that precipitate them mobilising and transforming the border into a defence against the outside. (p. 184)

Hopefully our pedagogical practice facilitates learning but, perhaps unconsciously, it can also impose values that might disqualify or marginalise forms of learning that ‘do not fit’, so as to ‘bully’ such practices into its frame (Stengers, Citation2005b, p. 1000; see also Bell, Citation2017, p. 187). This is not to argue for trying to think in the place of others but to ‘look to a future, [to create the possibilities] where they will take their place’ (Stengers, Citation2010; see also Bell, Citation2017, p. 192). It is developing a case for modes of attentiveness to the potential violence of our questions, our pedagogical orientations and values, that may prevent or disqualify ‘other’ modes of practice; a case for a speculative ethics in pedagogic work. The notion of looking to the future or thinking and acting pedagogically for a future, and not about the future, is central to the notion of speculative inquiry with which I am concerned. The difference in thinking for a future from thinking about the future concerns inventing modes of thought that construct a future as opposed to applying established modes of thought to re-present the future. It may be that if the notions of ‘learner’ or ‘teacher’ are tied too closely with the idea and representation of a prior world then we need to find another term that embraces both the inheritance of practice but equally a potential for invention. Here perhaps, in a speculative mode, we might then see learning and teaching in this light as an aporia, a process that undermines or is disobedient to its own inheritance, its own established premises – a practice of internal insurgency.

Speculative practice is inherent to art practice in the sense of inventing new relationalities, sensibilities, materialities, spatialities, temporalities, collectives. We might think of speculative pedagogies as processes in which new futures, new modes of becoming are invented and explored. Viewed in this light art practices (or other practices) in schools and elsewhere are therefore not concerned with the representation of a world but with the invention of worlds, the ontogenesis of worlds as they emerge within the situated specificities and matterings of practice. Equally then pedagogic work becomes an aesthetic process in which life itself is conceived as an ethico-political challenge.

How might we conceive an ethics and politics of speculative pedagogies that are devoted to trying to negotiate and inherit how something matters for a learner in the singularity of an event of a learning encounter? By engaging in a process of negotiation with the immanence of each singular case of learning/practice, we are in a sense inventing a future which is not yet known, thus, although we may consult, we cannot rely upon a kind of static inheritance of established codes or institutionalised apparatuses such as competencies or standards by imposing these upon the singularities of practice. This would be to resort to homogenising the interpreting of experience that Michael Hampe warns us against. Such negotiations and inheritances ‘in practice’ give rise to aesthetic, ethical and political questions as such negotiations approach the boundaries and divergence of each student’s practice and its potentialities … that potentially may evoke new questions, uncertainties and possibilities. Such negotiations in the here and now of diverse matterings of practice evoke an ethics of practice in its situated specificities, an ethics that is conscious of its fallibility, as suggested by William James (Citation1897/Citation1956): ‘The highest ethical life – however few may be called to bear its burdens – consists at all times in breaking the rules which have grown too narrow for the actual case’ (p. 209).

To echo James’ words, we might argue that pedagogical ethics has to be prepared to put aside forms of practice that are too narrow for responding to the situated specificities of a student’s learning encounter. It involves an ethics of the not-yet-known open to the situated and virtual potentialities of becoming, not a prescribed code for action. In pedagogic work therefore a teacher has to acquire, in Donna Haraway’s (Citation2016) terminology, a response-ability (p. 28) to local events of learning. This suggests, in relation to pedagogical relations, an ethics that is cultivated in the process of learning how to think and act in a particular pedagogical situation. These ethical considerations also involve or require a politics close to what Isabelle Stengers develops in her cosmopolitical proposal in which initially she draws our attention to the reference made by Deleuze and Guattari to the idea of the idiot found in Dostoyevsky.

Idiotic events and the cosmopolitical proposal

Stengers (Citation2004) tells us that in ancient Greek the idiot (p. 2) is the one who does not speak the Greek language or share established customs. For Deleuze and Guattari, the idiot, as a conceptual character, is the ‘one who slows the others down’ by resisting or interrupting established orders and customs, not because these are wrong but because there is something more important (which he or she does not know). This idea of ‘something more important’ resonates with Whitehead’s (Citation1938) advice, ‘have a care, here is something that matters’ (p. 116). The idiot, or more appropriate for my pedagogical purposes, an idiotic event, produces a gap, an interstice. We might say that the idiotic event is a provocation for thought and practice, a questioning presence. It does not tell us how to proceed but confers on a situation the power, the challenge, to make us think, as do some art practices produced, performed or orchestrated by artists, or some art practices of children or students.

An idiotic event is one that may have the power to make us think or act differently, but it does not offer criteria or guidance by which to do so. It punctures established procedures and produces the potential for a space of speculation in which we might conceive practice beyond the rules and grammars of established practices, a speculative space in which practice can be re-imagined and reconstructed beyond the borders of established thinking and making.

Stengers’ notion of the cosmopolitical proposal is aimed at giving priority for the power of a particular situation to provoke thought into new ways of thinking or making and how we might inherit such provocations. It does not seek general solutions or prescriptions and reduces the transcendence of authority or authoritative discourse. It refers to the creation of a space or process, a conjunction, in which each person has particular attachments and respective constraints. We are thus concerned with the idea of an etho-ecology with no transcendent position but an equalisation of presence and voice. This equalisation does not suggest that everyone is equal but respects the notion of divergent attachments, diverging morphologies of becoming and belonging. There is some affinity here with John Dewey’s (Citation1916) democratic project, that values and depends upon difference and responsibility; where all who participate develop a confidence in their individual abilities to be discerning and insightful. The term ‘cosmos’ does not refer to the universe but to the unknown as constituted by divergent worlds and what they may be capable of. In pedagogic work it refers to the not-known constituted by the divergent worlds of learners and teachers and to what they may be capable of. A cosmopolitical proposal for pedagogic work therefore suggests an ethics, politics and aesthetics by which such work is informed by a feeling that it cannot ‘master’ the situated specificities of a learner’s experience but nevertheless faces the challenge of how it might inherit from such situations. This ‘insistence’ of the not-known is part of pedagogic work and research. Do we allow it to ‘matter’ or do we anaesthetize it away (for example, through what Hampe terms homogenising the interpretation of experience in the form of assessment criteria, competences, etc.)? Thus, the cosmopolitical proposal as relating to pedagogic work concerns how we deal with the insistence of the not-known, how we inherit from it. This raises the inseparability, mentioned earlier, of the ethos from its oikos and the point that we don’t know what a being is capable of or can become capable of.

The cosmopolitical proposal is the one that is ‘idiotic’, that disturbs our foundations by a presence that invokes an etho-ecological ‘question’, and which demands a new etho-ecological signification that disturbs our stable acceptance of established orders. It asks us to consider and reflect upon how, in our domains of practice, we might or can inherit such disturbances and questions. Here, taking a cue from Stengers, we might consider both politics and ethics as an ‘art’ in the sense that art, not Art, or research, not Research, has no ground to demand compliance from what it deals with … it has to create the manners, to artefactualise, that will allow it to deal with what it deals with. How can we artfully ‘become-with’ and create the manners in pedagogic practice or in research practice, that allow us to respond effectively and commensurably with those encounters that confront us?

The cosmopolitical proposal is thus concerned with the becoming of relationalities in their various domains of practice, a process of composing with others without imposing established orders, a proposal that implies no transcendence but one where the need to pay due attention is crucial.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In a similar vein, Lauren Berlant’s (Citation2016) article, The commons: Infrastructures for troubling times, raises the notion of infrastructure as, ‘the patterning of social form, the living mediation that organises life (p. 393)’. Infrastructures include conceptual and affective processes. She is interested in those glitches, disturbances, or troubling times that reveal infrastructural failure and how we might proceed to repair such failures and what that repair might look like. What kind of conceptual infrastructures do we require to construct an imaginary that allows us to manage troubling times? She writes:

Rather than thinking of the ‘freedom from’ constraint that makes subjects of democracy value sovereignty and autonomy, and rather than spending much time defining the sovereign-who-is-never-a-sovereign (Agamben, Citation1998; Mbembe, Citation2003), this project looks to non-sovereign relationality as the foundational quality of being in common. (p. 394)

She seeks to ‘extend the commons concept’s pedagogy of learning to live with messed up yet shared and ongoing infrastructures of experience’ (p. 395). In querying the notion of the commons she asks:

… visceral questions about how the commons as an idea about infrastructure can provide a pedagogy of unlearning while living with the malfunctioning world, vulnerable confidence, and the rolling ordinary. (p. 396)

References

- Agamben, G. (1998). Homo sacer: Sovereign power and bare life. Stanford: Stanford UP.

- Altay, C. (2014). Rogue game: An architecture of transgression. In L. Rice, & D. Littlefield (Eds.), Transgression: Towards and expanded field of architecture (pp. 207–213). London: Routledge.

- Atkinson, D. (2011). Art, equality and learning: Pedagogies against the state. Rotterdam, Boston: Sense Publishers.

- Atkinson, D. (forthcoming book). Pedagogies of taking care: Art, pedagogy and the gift of otherness.

- Bell, V. (2017). On Isabelle Stengers’ cosmopolitics: A speculative adventure. In A. Wilkie, M. Savransky, & M. Rosengarten (Eds.), Speculative research: The lure of possible futures (pp. 187–197). London & New York: Routledge.

- Berlant, L. (2016). The commons: Infrastructures for troubling times. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 34(3), 393–419.

- Buck-Morss, S. (2010). The second time as farce … historical pragmatics and the untimely present. In C. Douzinas, & S. Zizek (Eds.), The idea of communism (pp. 67–80). London, New York: Verso.

- Carstens, D. (2020). Toward a speculative pedagogy. CriSTaL Critical Studies in Teaching & Learning, 8(SI), 75–91.

- De La Cadena, M., & Blaser, M. (Eds.). (2018). A world of many worlds. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Deleuze, G. (2004). Difference and repetition. London: Continuum.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1988). A thousand plateaus. London: Athlone Press.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1994). What is philosophy? London and New York: Verso.

- Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: Macmillan.

- Gerlach, J. (2014). Lines, contours and legends. Coordinates for vernacular mapping. Progress in Human Geography, 38(1), 22–39.

- Hampe, M. (2018). What philosophy is for. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspectives. Feminist Studies, 14, 575–599.

- Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Harney, S., & Moten, F. (2013). The undercommons, fugitive planning and black study. New York: Minor Compositions.

- James, W. (1897/1956). The will to believe, and other essays in popular philosophy. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

- Kuby, C. R., & Christ, C. C. (2020). Speculative pedagogies of qualitative inquiry. London: Routledge.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1990). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Mbembe, A. (2003). Necropolitics (translated by libby meintjes). Public Culture, 15(1), 11–40.

- Ranciere, J. (2010). Dissensus: On politics and aesthetics. London: Continuum.

- Savransky, M. (2017). The wager of an unfinished present. In A. Wilkie, M. Savransky, & M. Rosengarten (Eds.), Speculative research: The lure of possible futures (pp. 25–38). London & New York: Routledge.

- Shaviro, S. (2009). Without criteria: Kant, whitehead, deleuze, and aesthetics. Cambridge Mas: MIT Press.

- Spinoza, B. (1996). Ethics. London: Penguin.

- Stengers, I. (2004). The cosmopolitical proposal. Wordpress, on-line.

- Stengers, I. (2005a). An ecology of practices. Cultural Studies Review, 11(1), 183–196.

- Stengers, I. (2005b). The cosmopolitical proposal. In B. Latour & P. Weibel (Eds.), Making things public: Atmospheres of democracy (pp. 994–1003). Cambridge, MA: London: MIT Press.

- Stengers, I. (2010). The care of the possible. Interview by Bordeleau, E. In SCAPEGOAT: Architecture/Landscape/Political Economy, Issue 1, ‘Service’, pp. 12–17.

- Stengers, I. (2011). Comparison as a matter of concern. Common Knowledge, 17(1), 48–63.

- Stengers, I. (2014). Speculative philosophy and the art of dramatization. In R. Faber & A. Goffey (Eds.), The allure of things: Process and object in contemporary philosophy (pp. 188–217). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Thompson, H. E. (1997). The fallacy of misplaced concreteness: Its importance of critical and creative inquiry. Interchange, 28(2), 219–230.

- Whitehead, A. N. (1938). Modes of thought. New York: Free Press.

- Whitehead, A. N. (1997). Science and the modern world. New York: Free Press.