Abstract

Nurses in psychiatric inpatient care spend less time than desired with patients and investigation of the nature of nursing in this setting is needed. This study explores how nursing activities in psychiatric inpatient wards is distributed over time, and with a time-geographic perspective show how this relates to places. Observations were used to register place, activity, and time. A constructed time-geographic chart mapped the nurses’ path which showed that nurses spent little time in places where patients are. There might be constraints that affect nursing. Nurses need to evaluate where time is spent and interventions that facilitate relationships are needed.

Introduction

Mental health services have changed considerably during the last 100 years. Not only has there been a change from institutionalised care towards community-based services in Sweden, but psychiatric and mental health nursing itself has been questioned (Gabrielsson et al., Citation2020). At the same time, Söderberg et al. (Citation2022) described nursing as being constrained and lacking clarity regarding roles and responsibilities. Medicalisation of mental illness has also had a role in affecting nursing in the psychiatric context, but Gabrielsson et al., (Citation2020) argue for a separation from a medically oriented nursing towards a recovery-oriented, person-centred practice.

The caring perspective of psychiatric and mental health nursing as we know it today challenge the dominant medical focus of the psychiatric nursing care. It is suggested that psychiatric and mental health nurses need to overcome challenges posed by the dominant medical paradigm, to shape their own future, and to contribute to a more person-centred practice. (Gabrielsson et al., Citation2020). To promote a recovery-oriented and therapeutic practice the time spent with the patient needs to be increased. The patients need time to talk through their problems, therefore time is a prerequisite for mental health nursing (Jackson & Stevenson, Citation1998). Unfortunately, today’s psychiatry is lacking the time needed (Gabrielsson et al., Citation2020).

Spending time with the patient and building trusting relationships are often defined as important components in good psychiatric care regardless of setting (Bacha et al., Citation2020; Barker & Buchanan-Barker, Citation2004). The existence of therapeutic relationships between psychiatric care nurses and patients in an inpatient setting has been shown to be important in order for patients to experience meaning (Johansson & Eklund, Citation2003). According to a narrative review, nurses working in inpatient psychiatric care describe a therapeutic relationship as an interaction between the nurse and the patient based on trust, and patients also expect a care that is respectful, personalised and empowering (Moreno-Poyato et al., Citation2016). Qualities that the patients expect from nurses include empathy and understanding, listening and accessibility as well as authenticity and honesty. This is in keeping with the concept of person-centred care in the psychiatric context (Gabrielsson et al., Citation2015).

As nursing research is expanding and extending its horizons, new perspectives are being explored. One of these perspectives includes geography and certain research has taken on a decidedly geographical orientation (Andrews et al., Citation2013; Andrews & Shaw, Citation2008). Health geography has until fairly recently had a quantitative focus, but Andrews (Citation2003) claims that in recent years a more qualitative approach, focussing on the dynamic between health and place, has also emerged. Malone (Citation2003) argues that nursing practice has spatial aspects and since the relationship to the patient is central for this practice, sustaining a meaningful proximity to the patient is at least in part something nursing practice is dependent upon. This makes the geographical aspect of nursing research an interesting area of exploration.

Time-geography is a concept that emphasises time, space, and the interplay between these dimensions (Ellegård, Citation2018b). First developed by Hägerstrand (Citation1985), time-geography assumes that there is a geographic location tied to everything that happens and that this location reveals the context of a phenomenon at a certain time (Ellegård, Citation2018b). Time-geography combines spatio-temporal perspectives to describe important events in relation to spaces in time and can offer a structured image of, for instance, the life course of a person (Sunnqvist et al., Citation2020). Time-geography has been used to gain new perspectives in different disciplines such as geography, history, and psychiatric and mental health nursing.

Nurses working in psychiatric inpatient and forensic settings highlight the importance of having enough time to establish relationships and being present with patients (Gabrielsson et al., Citation2016; Salzmann‐Erikson et al., Citation2016). Although there are a number of different models and perspectives regarding the content of the therapeutic relationship, nurses find that a lack of time is a barrier for creating and maintaining these relationships (Moreno-Poyato et al., Citation2016). Likewise, patients agree that a lack of time is the main reason limiting the establishment of therapeutic relationships (Moreno-Poyato et al., Citation2016).

Nurses working in a psychiatric inpatient context appear to be working mostly with activities related to medication, planning, and reporting (Abt et al., Citation2022; Glantz et al., Citation2019). Although results and methods for activity classification differ, studies show that nurses in psychiatric inpatient care spend comparatively little time with patients (Abt et al., Citation2022; Glantz et al., Citation2019; Seed et al., Citation2010). There are few studies detailing the time psychiatric and mental health nurses in inpatient care spend with patients. Research shows varying results, ranging from 1 to 41% (Furåker, Citation2009; Glantz et al., Citation2019; Sharac et al., Citation2010). It is unclear how much of that time is spent on therapeutic activities (Sharac et al., Citation2010).

The importance of places in relation to psychiatric and mental health inpatient nursing has not been widely explored. In a study by Zhou and Rosenberg (Citation2021) the facilitation of both spatial and temporal settings in regard to doctors’ and patients’ transitions between relationships was explored. It showed that the relationship was affected by the place in which the meeting between patient and doctor occurred but also the time afforded the meeting, as well as the discourse during the meeting. Andes and Shattell (Citation2006) discussed that psychiatric patients have little control over space, and the space they occupy is constantly being invaded by health care staff and other patients. They also discussed that nursing stations are off limits to patients with looked doors and Plexiglas and this of course affect the relationship. However, as shown in for instance Glantz et al. (Citation2019), nurses in this context spend their working time at a large variety of places. It is reasonable that different places and time spent at these places affect the relationship between nurses and patients. There is a need to further explore the nature of psychiatric and mental health nursing activities in relation to time and place in an inpatient context as relatively few studies are concerned with this subject. This will provide a foundational knowledge regarding which activities are carried out where and for what amount of time. This foundation can further be built upon with research regarding for example the content of nursing activities and how they are affected by time and place.

Considering the desire for patients and nurses to spend time together in meaningful activities and the fact that there still is limited knowledge of how time is actually spent in psychiatric inpatient care, there is a need to further explore nurses’ activity time and place distribution. This will aid an understanding of psychiatric and mental health nursing. There are, as far as the authors can tell, no examples of time-geography being used as a tool in psychiatric and mental health nursing research for the purpose of gaining a perspective on nurses’ activity, time and place distribution in an inpatient setting. This study aimed to explore how nurses in psychiatric inpatient wards spend their time and how their activities are distributed over time, and to show, applying a time-geographic perspective, how these two variables relate to places.

Methods

The concept of time and motion studies was introduced by Frederick Taylor, who is associated with the scientific management movement (Taylor, Citation1911). At their core, time and motion studies seek to measure the time spent on activities or tasks as well as the motion required to perform them (Lopetegui et al., Citation2014). This can be carried out with a simple tool such as a stopwatch and an observer measuring the time needed to complete a task.

The time and motion design has been used in other similar studies aiming to describe hospital staff’s task time distribution (Abt et al., Citation2022; Altiner et al., Citation2020; Glantz et al., Citation2019; Westbrook et al., Citation2011). Structured observations are useful for recording actions, events, or behaviours using protocols specifying what is being observed (Polit & Beck, Citation2021). The observation protocol used in this study was based on the Work Observation Method By Activity Timing (WOMBAT) protocol (Westbrook & Ampt, Citation2009). In this study, the time and motion were measured by an observer performing structured observations and measuring the time used by nurses carrying out activities at a ward, as well as registering the geographic locations involved.

Settings and participants

In all, four registered nurses from three wards specialised in general psychiatry volunteered to participate. These wards were chosen for their similarities to achieve a level of homogeneity between the different wards. These general psychiatry wards typically care for patients with affective, personality or neuropsychiatric disorders. Patients at these wards are admitted either voluntarily or compulsory. One of the nurses included was a specialist, which means a registered nurse with an additional one-year university training in psychiatric and mental health nursing and a one-year master’s degree. This convenience sample was drawn from two psychiatric clinics in southern Sweden. There are five eligible general psychiatry wards at these clinics, and all were contacted to recruit participants. Nurses at these wards worked slightly different hours but were generally scheduled for either a morning/day shift or afternoon/evening shift. The hours included ranged from 7 am to 9 pm all days of the week, including weekends. Nurses working night shifts were excluded due to the different nature of the activities performed during nights compared to the activities carried out during the day. See for demographic data.

Table 1. Demographic data, n = 4.

When the heads of clinics had given their permission, heads of units were contacted, and oral and written information was provided. At three of the wards the information about the study was then passed on to all eligible nurses by the heads of units. At the two other wards, the first author also visited the wards and provided further oral and written information to the heads of units and nurses. Nurses who expressed interest were provided with further written information as well as giving oral and written consent. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Reg. no. 2019-00061).

Data collection

The observer (author 1) is a registered nurse with specialist training in psychiatric and mental health nursing. At the time of observation, the author did not work at nor had any affiliation with the wards included in this study.

Data was collected through the use of TimeCaT 3.9, a web-based time and motion tool developed by Lopetegui et al. (Citation2012). This tool allows for on-the-go capture of activities, time, and place via for, example, a tablet-based device. Not only does the tool collect data but it also provides the user with descriptive data analysis and visualisation. This open-source software has previously been used in several time and motion studies and has specifically been tested for validity and reliability with the Omaha System (Altiner et al., Citation2020; Schenk et al., Citation2017; Yen et al., Citation2018; Citation2019). The web application ran on an Apple iPad that the observer carried with him.

Previous to the commencement of observations, the categories of nursing activities based on the WOMBAT protocol (Westbrook & Ampt, Citation2009) were entered into the TimeCaT software as well as common places at a psychiatric inpatient ward, based on the observer’s exploration of the wards previous to the actual observations taking place. These categories were the same as the categories used in Glantz et al. (Citation2019). See for activity categories and definitions.

Table 2. Activity categories and definitions.

Three preparatory pilot observations, totalling 2 hours and 34 minutes, were carried out at a different ward than the ones included. The purpose of this was for the observer to practise using the time capture tool, identify any possible obstacles, and identify the possible places at the wards. These observations were not included in the result.

The total time observed during the eight non-pilot observations of the study amounted to 30 hours and 47 minutes. The identified places were the medicine room, the nurses’ station, the hallways, the dining area, the doctor’s office, the kitchen, the common area, the patient rooms, the conversation rooms, the supply room, the treatment room, the rounds room, and off ward spaces.

The observations were carried out during October and November 2020 as well as November 2021. The interruption in observations was due to the ongoing covid-19 pandemic. During observations, the observer followed the nurse and registered the nurse’s activity and place. The observer maintained a distance to avoid interference or intrusiveness. The software had sections for registering both the places and the activities. A continuously running stopwatch, integrated into the software, kept track of the time during which these two variables were active. Each observation lasted for approximately four hours, or the equivalent of half a working shift. These observations were evenly distributed over weekdays and weekends and covered the hours of 7 am to 11 am, 11 am to 3 pm, 1 pm to 5 pm and 5 pm to 9 pm. Each nurse was observed twice, resulting in a total of eight observations.

Analysis

The percentage of observed time spent on specific activities and in specific places was calculated. All data was processed using descriptive statistical analysis in Microsoft Excel 16.59 and TimeCaT 3.9. This analysis is presented by activity as well as by place, with the three most common activity categories in each place.

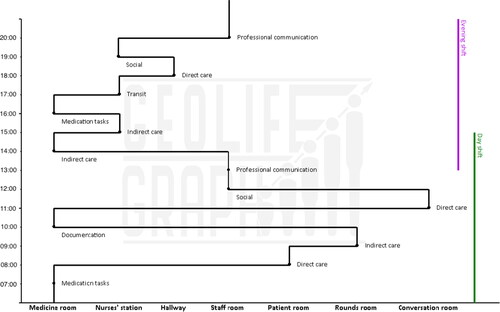

To gain a time-geographic perspective, all the data from all observations were sorted using pivot tables in Microsoft Excel. This made it possible to, out of the total number of observations, find the most common place by percentage during each whole hour between 7 am and 9 pm as well as the most common activity by percentage performed in that place during each hour. Using data calculated in this manner, a time-geographic overview chart was constructed in the time-geography charting software GeoLife Graph®. The chart contains a path showing the most common places and activities for all the nurses throughout all the hours included in the observations. The X-axis represents the places, while the Y-axis represents the hours. The most common activity category by percentage in each place and during each hour is represented by a dot and the name of the activity category. The resulting constructed chart was further supported with the visual aid of two coloured vertical lines, dividing the chart into day and evening shifts, consisting of the time slots 7 am to 3 pm and 1 pm to 9 pm, respectively. The constructed path is a cognitive aid to increase visual understanding of the observed nurses’ activities in time and place.

Results

The constructed time-geography chart presented visualises the place that the nurses most commonly occupied at each hour of the working day and it is divided in two by means of coloured vertical lines indicating work shifts. There was an overlap between shifts of approximately two hours during which there was a larger staff working. At each hour and in each place, the most common activity performed there by the observed nurses is indicated. The most common place at each hour by percentage and the corresponding activity in that place and at that time can be found in .

Table 3. Percentage of places and activities in the time-geography chart.

Day shifts

As seen in , between 7 am and 8 am during day shifts, the most common place was the medicine room and the most common activity medication. The nurses then carried out direct and indirect care activities as well as documentation during the mornings while moving between patients’ rooms, the rounds room, and the medicine room. There was also during one observation a longer conversation between a nurse and a patient in one of the conversation rooms, which influenced the outcome between 11 am and noon. At noon and for two hours onward, the most common place during the observations was the staff room, with both social and professional communication activities. Between 1 pm and 3 pm, while there were two staff working, the most common places were the staff room and the medicine room, where professional communication and indirect care activities were being carried out.

Figure 1. The X-axis represents the places nurses most commonly occupied during the observed hours. The Y-axis represents the hours of the working day. The dots at each hour represents the most common activity during that time and one hour on. The green vertical line indicates the day shift, while the purple vertical line indicates the evening shift.

Evening shifts

Evening shifts began at 1 pm with professional communication activities in the staff room. Between 2 pm and 6 pm, the places the nurses occupied were the medicine room and the nurses’ station, with indirect care, medication, and transit being the most common activities. The only instance where direct care was the most common activity category at the most common place, was in the hallway between 6 and 7 pm. Between 7 pm and 9 pm the nurses’ activities were social activities and professional communication at the nurses’ station and in the staff room. The most common place during the entire evening shift was the nurses’ station.

Activities in time and place

The overall results show that nurses on average spent 22.5% of the observed period on indirect care activities. The second largest activity category was medication tasks, accounting for 18.2% of the observed time. Direct care activities, excluding medication activities but including activities such as direct communication, nursing procedures, or other activities with the patient present, came in third with 17.1% of the observed time. summarises the time and activity distribution.

Table 4. Overview of activity-time distribution.

The nurses included in this study spent most of their time, 28.6%, in the medicine room. The second most common place was the nurses’ station with 18.8%. At 14.7%, the staff room was the third most common place. In total, about 62% of the total observed time was spent in these three places. outlines all the places where activities took place and the most common activities in these places.

Table 5. Overview of places and activity distributions.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore how nurses in psychiatric inpatient wards spend their time and how their activities are distributed over time, and to show, applying a time-geographic perspective, how these two variables relate to places. The novel use of time-geography in this study helps anchor the nurses’ activities to certain places in time. As shown, nurses in the day shift occupy several different places and this is also the shift where, in two places, direct care activities are the most common. It is, furthermore, notable that there is only one occasion throughout the day where the patient room is the most common place for the nurse to occupy. This could correlate with patients’ experiences of being invisible to the staff or of staff prioritising activities that do not involve the patients (Molin et al., Citation2016). It is also in line with nurses’ experiences of an unsatisfactory work situation where they experience a lack of time to spend with patients (Graneheim et al., Citation2014).

The geographic places of the psychiatric wards included in this study all consists of areas which Salzmann-Erikson and Eriksson (Citation2012) characterise as staff spaces. These spaces, unlike neutral or patient’s spaces, are places the nursing staff always has access to. Even the patient rooms are staff spaces since they are always accessible to the staff. Patients, however, do not necessarily always have access to all the places at a ward and there are often restrictions in place, such as locked doors, to prevent access. The time-geographic chart highlights the fact that the medicine room is the most common place overall in this study. During the evening shift, there is only one occurrence where the most common place is not the medicine room, the nurses’ station, or the staff room. These places are staff spaces where access is typically restricted. This begs the question whether it is possible to build sustainable, therapeutic relationships when so much time is spent in places that patients typically cannot access. Nursing tasks in these places would most likely be restricted to medication, documentation and possibly surveillance related tasks, which are tasks that are necessary but perhaps not to the extent demonstrated in this study. Spending time in places restricted to staff access is not conducive to a psychiatric and mental health nursing that is a positive force for patients’ change and recovery. It is difficult to draw conclusions as to why so little time is spent performing direct care activities, or why the nurses in this study spent most of their time in places away from the patients; however, the time-geography concept of constraints might offer a perspective on this (Ellegård, Citation2018a). Constraints are obstacles that stop the human individual from performing activities in order to achieve the goals of their projects and can be of three types: capacity, authority and coupling constraints. Capacity constraints are related to the individual’s abilities, knowledge, or tools, while authority constraints are related to rules, laws, or agreements that individuals in an organisation are to follow. The term ‘coupling’ refers to the necessity of individuals to be coupled to each other in the time-space dimension in order to carry out an activity (Ellegård, Citation2018a), and coupling constraints are obstacles to this togetherness.

It is possible that these constraints come into play when shaping the nurses’ working days. At a higher level, the individual’s personal projects might clash with organisational projects. If, for instance, the individual nurse’s project includes more activities such as are described in the direct care category to reach a goal of person-centred care, while the organisational projects favour efficiency and management of a lack of staff, this might lead to constraints. Indeed, nurses express an inability to live up to their own ideals due to unsatisfactory work situations (Graneheim et al., Citation2014). Capacity constraints might include a lack of knowledge or training, which in turn might alter the focus of the individual away from activities such as direct care towards more clearly defined activities like the preparation and administration of medicine or reporting. Authority constraints might also come into play if these are based on projects whose goal is efficiency. Capacity and authority constraints are, furthermore, affected by and interact with coupling constraints. If the coupling of the nurse and the patient is restricted due to capacity and/or authority constraints, the direct care activities that might contribute to a therapeutic relationship-building and further a person-centred care, will not be realised. The implementation of an intervention such as ‘Time Together’ (Molin et al., Citation2018) might be one way to reduce coupling constraints. This intervention, based on the ‘Protected Engagement Time’ nursing intervention (Kent, Citation2005), aims at being a foundation for enabling and encouraging interaction between patients and staff by arranging for a specific time each day being set aside for joint activities (Molin et al., Citation2018).

It is also worth noting that during the hours between 1 pm and 3 pm, when there is typically a larger staff than during other hours of the day, most of the nurses’ time was spent either in the staff room carrying out professional communication activities, such as handover, or in the medicine room performing indirect care activities. This is a time when it seems as if there would be an opportunity to plan the work at the ward in such a way that more direct care activities could be carried out and hence more time be spent together with patients. Indeed, these hours also correspond to the time slot when two of the wards included in a study by Molin et al. (Citation2018) implemented the previously described intervention ‘Time Together’.

The nurses observed in this study spent most of their time on indirect care activities as well as on medication activities, with direct care activities coming in third. These three activity categories are the same as the most common categories observed in a study with a similar method and setting (Glantz et al., Citation2019), although further conclusions about similarities are difficult to draw. It is nevertheless noteworthy that nurses spend a great deal of time on medication and indirect care activities, where there are minimal opportunities for nurse-patient interactions beyond administering medication. This seems to correlate with a study showing that nurses tend to distance themselves from patients (Moyle, Citation2003). The time spent on direct care activities in this study amounted to 17.1%, which, considering the attempts to further person-centred care in psychiatric and mental health nursing, must be considered low. It would appear that nurses spend a far greater deal of their time than desired talking about patients rather than with patients. It may be argued that medication activities include direct care aspects during the administration of medicine. Even so, the combined time spent performing professional communication and indirect care activities is almost the same amount of time as is spent performing direct care and medication activities. This contradicts the expectations of patients, where a wish for helping relationships is central, while nurses’ lack of time is expressed as contributing to feelings of remoteness (Johansson & Eklund, Citation2003; Moreno-Poyato et al., Citation2016).

Nurses in this study spent 17.1% of their time on direct care activities, which would seem far from ideal when developing relationships. Even though other professions might of course also spend time with patients, this was not investigated in this study. Psychiatric and mental health nurses’ practice however is poised as something that is quite distinctive and special (Santangelo et al., Citation2018). This distinctive and special practice contains, among other things, care that is present, personal and takes on a form of active participation that leads to therapeutic engagement. That makes psychiatric and mental health nursing a practice that cannot easily be replaced by other professions’ practices. Since this study did not specifically investigate the content of the direct nursing tasks nor what was said between nurses and patients, it’s difficult to draw conclusions about the meaningfulness of these encounters. Further in-depth observations of interaction or interviews with patients and nurses might have brought important realisations about the quality of interactions.

Another factor worth considering is the relationship between places and the balance of power between the nursing staff and patients. This study shows that there are several places where nurses spend time and where patients generally aren’t allowed access. As discussed by Andes and Shattell (Citation2006), such places, like the nurses’ station, might contribute to alienation of nurses from patients and vice versa, possibly contributing to a power imbalance in the nurse-patient relationship. Further research into how nurses’ and patients’ identities might be shaped by the different places in a psychiatric inpatient setting would be valuable.

This study used observations with a time and motion method for capturing data. Another common data capture strategy is self-reporting. The use of observations rather than self-reporting has several advantages, however. Complex observations such as the ones carried out in this study, with both time, activity, and place being registered, would have been very difficult to self-report, especially with the level of detail that was allowed using TimeCaT. It is also not unlikely that, for various reasons, mistakes or failure to self-report would have occurred more frequently than with a dedicated observer. The use of observations increases the validity of the results in this study compared to other methods. This has been shown in previous comparisons between observations and self-reporting (Ampt et al., Citation2007; Finkler et al., Citation1993).

The basis for the observational protocol was WOMBAT, which has proven reliable and valid (Ballermann et al., Citation2011) and has been used in a number of observational studies. The observer in this study was a registered nurse specialist with experience from inpatient psychiatric care, which meant that there was a familiarity with the observed activities, decreasing the risk of mistakes in registering the proper activity.

The time-geography perspective used in this study highlights the distribution of time, the places in psychiatric inpatient wards, and the activities that nurses perform there. The constructed chart shows the observed nurses not as single individuals but as a whole, and how the activities carried out relate to different places in time. The coloured vertical lines used in the chart make it clear that there should be even more possibilities for nurse-patient couplings with activities that are beneficial for the patients. Using this kind of notation offers a unique perspective on nurses’ working days and opens the door for further exploration, like making charts on even smaller scales with individual nurses and possibly for shorter periods of time. This perspective brings further insight to the field of psychiatric and mental health nursing.

Use of the time capture tool TimeCaT proved successful and made the simultaneous registration of activities and places feasible. Since TimeCaT is a web application, there is a risk of either loss of connectivity or the website being inaccessible during observation. Indeed, at one point during one of the observations, the website became unresponsive, which resulted in the loss of several minutes of data. This is something which has been previously discussed by Lopetegui et al. (Citation2012) and could be remedied with offline support.

Direct observations are in their nature prone to what is called the Hawthorne effect, where the observed participants alter their behaviour due to being aware of the observer’s presence. To combat this, the observations lasted for an extended period of approximately four hours, decreasing the risk of the participants changing behaviour in the long term. Nevertheless, this effect cannot be completely ruled out. However, at least one study showed that there might in fact be little reactivity to direct observations (Schnelle et al., Citation2006).

Since only four nurses at three wards were recruited, there is a risk of recruitment bias and that the nurses included in this study were less representative compared to other nurses in the field. The relatively limited number (30) of hours of observational data collected in this study also makes it difficult to draw far-reaching conclusions. However, as previously noted, the results of this study point to similarities to, for instance, Glantz et al. (Citation2019). Ellegård (Citation2018b) also describes how time-geography can function at both micro and macro levels. This study shows time-geography on a micro level, although this could be even further scaled down to an analysis on an hourly level rather than a full day. Further studies with more observational data are needed, however, to confirm both the time and place aspects of this study.

Relevance for clinical practice

The findings in this study suggest that nurses are spending relatively little time together with patients or in places that patients have access to. This knowledge highlights the need for interventions that enable the establishment and development of the nurse-patient relationship, such as Protected Engagement Time (Kent, Citation2005), Time Together (Molin et al., Citation2018) Daily Conversations (Molin & Hällgren Graneheim, Citation2022) or Star Wards (Janner, Citation2007). It could also be of interest for managers when planning the structure and staffing needs in inpatient psychiatric care.

The time observed at the wards shows that indirect care and medication activities were the most common categories measured, with direct care coming in third. The reasons for this are unclear, and the present study does not seek to explain this. It does however correlate with the findings showing that the most common places that the nurses occupied were the medicine room, the nurses’ station, and the staff room, places where patients will normally not be found. Another finding was that even when both the day and evening shift were working at the same time, the nurses spent most of their time in the staff room or the medicine room. This begs the question whether capacity or authority constraints contributed to the missed opportunities for direct care.

Suggestions for future research

Future research could further investigate constraints through for instance exploring the nurses’ expectations, and how the available time and expected activities might be affected by both the geographical layout of the wards as well as by the aforementioned constraints.

The time-geographic perspective helps visualise where nurses carry out their activities during their working days and anchors these activities to places in time. By further exploring the use of a time-geography perspective in quantitative psychiatric and mental health nursing research, a deeper understanding can be gained about the nurses’ place, time, and activity distribution. This could aid in developing interventions to increase the time nurses spend with patients and be used as a tool to evaluate these interventions.

Furthermore, the result of this study implies that comparatively little time is spent with patients. This also calls into question whether the care could be considered person-centred. A concept analysis by Gabrielsson et al. (Citation2015) defined person-centred care specifically in the psychiatric setting as cultural, relational, and recovery-oriented. In order for psychiatric and mental health nursing to move in the direction of being relational and recovery-oriented, the time spent with patients is a factor that needs to be further evaluated.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the nurses who participated in this study. We would also like to acknowledge Fredrik Merell for his statistics support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data is available upon reasonable request. This research adhered to the STROBE reporting checklist (von Elm et al., Citation2008).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abt, M., Lequin, P., Bobo, M. L., Vispo Cid Perrottet, T., Pasquier, J., & Ortoleva Bucher, C. (2022). The scope of nursing practice in a psychiatric unit: A time and motion study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 29(2), 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12790

- Altiner, M., Secginli, S., & Kang, Y. J. (2020). Refinement, reliability and validity of the Time Capture Tool (TimeCaT) using the Omaha System to support data capture for time motion studies. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 17(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/jjns.12296

- Ampt, A., Westbrook, J., Creswick, N., & Mallock, N. (2007). A comparison of self-reported and observational work sampling techniques for measuring time in nursing tasks. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 12(1), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.1258/135581907779497576

- Andes, M., & Shattell, M. M. (2006). An exploration of the meanings of space and place in acute psychiatric care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 27(6), 699–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840600643057

- Andrews, G. J. (2003). Locating a geography of nursing: Space, place and the progress of geographical thought. Nursing Philosophy: An International Journal for Healthcare Professionals, 4(3), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1466-769x.2003.00140.x

- Andrews, G. J., Hall, L. M., Price, S., Lalonde, M., Harris, A., & Macdonald-Rencz, S. (2013). Mapping nurse mobility in Canada with GIS: Career movements from two Canadian provinces. Nursing Leadership, 26(sp), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.12927/cjnl.2013.23249

- Andrews, G. J., & Shaw, D. (2008). Clinical geography: Nursing practice and the (re)making of institutional space. Journal of Nursing Management, 16(4), 463–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00866.x

- Bacha, K., Hanley, T., & Winter, L. A. (2020). ‘Like a human being, I was an equal, I wasn’t just a patient’: Service users’ perspectives on their experiences of relationships with staff in mental health services. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 93(2), 367–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12218

- Ballermann, M. A., Shaw, N. T., Mayes, D. C., Gibney, R. T. N., & Westbrook, J. I. (2011). Validation of the Work Observation Method By Activity Timing (WOMBAT) method of conducting time-motion observations in critical care settings: An observational study. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 11(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-11-32

- Barker, P. P. J., & Buchanan-Barker, P. (2004). The tidal model (1st ed.). Routledge Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203340172

- Ellegård, K. (2018a). Introduction - The roots and diffusion of time-geography. In K. Ellegård (Ed.), Time geography in the global context (pp. 1–18). Routledge.

- Ellegård, K. (2018b). Thinking time geography. Routledge.

- Finkler, S. A., Knickman, J. R., Hendrickson, G., Lipkin, M., Jr., & Thompson, W. G. (1993). A comparison of work-sampling and time-and-motion techniques for studies in health services research. Health Services Research, 28(5), 577–597.

- Furåker, C. (2009). Nurses’ everyday activities in hospital care. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(3), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00832.x

- Gabrielsson, S., Sävenstedt, S., & Olsson, M. (2016). Taking personal responsibility: Nurses’ and assistant nurses’ experiences of good nursing practice in psychiatric inpatient care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(5), 434–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12230

- Gabrielsson, S., Sävenstedt, S., & Zingmark, K. (2015). Person-centred care: Clarifying the concept in the context of inpatient psychiatry. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 29(3), 555–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12189

- Gabrielsson, S., Tuvesson, H., Wiklund Gustin, L., & Jormfeldt, H. (2020). Positioning psychiatric and mental health nursing as a transformative force in health care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41(11), 976–984. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2020.1756009

- Glantz, A., Örmon, K., & Sandström, B. (2019). “How do we use the time?” – An observational study measuring the task time distribution of nurses in psychiatric care. BMC Nursing, 18(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-019-0386-3

- Graneheim, U. H., Slotte, A., Säfsten, H. M., & Lindgren, B.-M. (2014). Contradictions between ideals and reality: Swedish registered nurses’ experiences of dialogues with inpatients in psychiatric care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35(5), 395–402. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2013.876133

- Hägerstrand, T. (1985). Time-geography: Focus on the corporeality of man, society and environment. The Science and Praxis of Complexity, 3, 193–216.

- Jackson, S., & Stevenson, C. (1998). The gift of time from the friendly professional. Nursing Standard, 12(51), 31–33. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.12.51.31.s44

- Janner, M. (2007). From the inside out: Star Wards – Lessons from within acute in-patient wards. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 3(02), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646407001136

- Johansson, H., & Eklund, M. (2003). Patients’ opinion on what constitutes good psychiatric care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 17(4), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0283-9318.2003.00233.x

- Kent, M. (2005). My mental health. Mental Health Practice, 8(8), 22–22. https://doi.org/10.7748/mhp.8.8.22.s15

- Lopetegui, M., Yen, P. Y., Lai, A. M., Embi, P. J., & Payne, P. R. (2012). Time Capture Tool (TimeCaT): Development of a comprehensive application to support data capture for Time Motion Studies. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings Archive, 2012, 596–605.

- Lopetegui, M., Yen, P.-Y., Lai, A., Jeffries, J., Embi, P., & Payne, P. (2014). Time motion studies in healthcare: What are we talking about? Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 49, 292–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2014.02.017

- Malone, R. E. (2003). Distal nursing. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 56(11), 2317–2326. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00230-7

- Molin, J., Graneheim, U. H., & Lindgren, B.-M. (2016). Quality of interactions influences everyday life in psychiatric inpatient care—Patients’ perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 11(1), 29897–29811. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v11.29897

- Molin, J., & Hällgren Graneheim, U. (2022). Participation, confirmation and challenges: How nursing staff experience the daily conversations nursing intervention in psychiatric inpatient care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 43(11), 1056–1063. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2022.2116135

- Molin, J., Lindgren, B. M., Graneheim, U. H., & Ringnér, A. (2018). Time together: A nursing intervention in psychiatric inpatient care: Feasibility and effects. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(6), 1698–1708. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12468

- Moreno-Poyato, A. R., Montesó-Curto, P., Delgado-Hito, P., Suárez-Pérez, R., Aceña-Domínguez, R., Carreras-Salvador, R., Leyva-Moral, J. M., Lluch-Canut, T., & Roldán-Merino, J. F. (2016). The therapeutic relationship in inpatient psychiatric care: A narrative review of the perspective of nurses and patients. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 30(6), 782–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2016.03.001

- Moyle, W. (2003). Nurse-patient relationship: A dichotomy of expectations. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 12(2), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-0979.2003.00276.x

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2021). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (11th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- Salzmann-Erikson, M., & Eriksson, H. (2012). Panoptic power and mental health nursing—Space and surveillance in relation to staff, patients, and neutral places. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(8), 500–504. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2012.682326

- Salzmann‐Erikson, M., Rydlo, C., & Wiklund Gustin, L. (2016). Getting to know the person behind the illness – The significance of interacting with patients hospitalised in forensic psychiatric settings. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(9–10), 1426–1434. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13252

- Santangelo, P., Procter, N., & Fassett, D. (2018). Mental health nursing: Daring to be different, special and leading recovery-focused care? International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(1), 258–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12316

- Schenk, E., Schleyer, R., Jones, C. R., Fincham, S., Daratha, K. B., & Monsen, K. A. (2017). Time motion analysis of nursing work in ICU, telemetry and medical-surgical units. Journal of Nursing Management, 25(8), 640–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12502

- Schnelle, J. F., Ouslander, J. G., & Simmons, S. F. (2006). Direct observations of nursing home care quality: Does care change when observed? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 7(9), 541–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2006.03.009

- Seed, M. S., Torkelson, D. J., & Alnatour, R. (2010). The role of the inpatient psychiatric nurse and its effect on job satisfaction. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31(3), 160–170. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840903168729

- Sharac, J., McCrone, P., Sabes-Figuera, R., Csipke, E., Wood, A., & Wykes, T. (2010). Nurse and patient activities and interaction on psychiatric inpatients wards: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(7), 909–917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.03.012

- Söderberg, A., Ejneborn Looi, G.-M., & Gabrielsson, S. (2022). Constrained nursing: Nurses’ and assistant nurses’ experiences working in a child and adolescent psychiatric ward. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 31(1), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12949

- Sunnqvist, C., Rämgård, M., & Örmon, K. (2020). Time geography, a method in psychiatric nursing care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41(11), 1004–1010. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2020.1757795

- Taylor, F. W. (1911). The principles of scientific management. Harper & Brothers Publishers.

- von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2008). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(4), 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

- Westbrook, J. I., & Ampt, A. (2009). Design, application and testing of the Work Observation Method by Activity Timing (WOMBAT) to measure clinicians’ patterns of work and communication. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 78, S25–S33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.09.003

- Westbrook, J. I., Duffield, C., Li, L., & Creswick, N. J. (2011). How much time do nurses have for patients? A longitudinal study quantifying hospital nurses’ patterns of task time distribution and interactions with health professionals. BMC Health Services Research, 11(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-319

- Yen, P. Y., Kellye, M., Lopetegui, M., Saha, A., Loversidge, J., Chipps, E. M., Gallagher-Ford, L., Buck, J. (2018). Nurses’ time allocation and multitasking of nursing activities: A time motion study. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings Archive, 2018, 1137–-1146.

- Yen, P. Y., Pearl, N., Jethro, C., Cooney, E., McNeil, B., Chen, L., Lopetegui, M., Maddox, T. M., & Schallom, M. (2019). Nurses’ stress associated with nursing activities and electronic health records: Data triangulation from continuous stress monitoring, perceived workload, and a time motion study. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings Archive, 2019, 952–961.

- Zhou, P., & Rosenberg, M. W. (2021). “Old friend and powerful cadre”: Doctor-patient relationships and multi-dimensional therapeutic landscapes in China’s primary hospitals. Health & Place, 72, 102708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102708