Abstract

The undergraduate mental health nursing course is an optimal time to address stigma and prejudice, while developing positive student attitudes toward those who live with mental health conditions. A quasi-experimental, pretest-posttest, nonequivalent-group study with a sample of undergraduate nursing students in New York City (N = 126) was conducted to determine the impact of an undergraduate mental health nursing course on attitudes toward people living with a general mental illness, depression, or schizophrenia. The intervention resulted in a significant reduction in total prejudice scores toward those with a general mental illness when compared to the control (p = 0.033, partial η2 = 0.062). The intervention had no significant impact on total prejudice scores regarding those with depression, or schizophrenia. Subscale analysis revealed the intervention significantly reduced attitudes of fear/avoidance regarding general mental illness (p = 0.040, partial η2 = 0.058) and schizophrenia (p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.164). There was no impact on authoritarian or malevolent attitudes. Though some attitudes were not amenable to change, this study provides evidence that positive attitudes can be cultivated through undergraduate nursing education. Curricular reform is needed to reduce all facets of prejudice and best prepare future nurses to care for those with mental health conditions.

Introduction

Multiple orderlies would throw me down and give me shots. I genuinely thought the staff were trying to kill me when they grabbed me and injected me. I had no idea at all what they were injecting, and it absolutely terrified me each time…Sometimes they injected me in the calf, and it was very painful. One nurse said to me, ‘I’m purposely hurting you so you’ll cooperate next time.’—Eleanor (Miller & Hanson, Citation2016, p. 114)

The stigma attached to mental illness

Stigma has been considered a disgraceful social marking, a deprecating label, and a dehumanizing theft of personhood (Yanos, Citation2018). Stigma is not inherent in mental illness but is attached to mental illness. The stigma attached to mental illness is an encompassing lens through which those experiencing a mental illness are devalued and discredited (Goffman, Citation1963). Such individuals are viewed as “dangerous, unpredictable, incompetent, and unable to function in society” (Yanos, Citation2018, p. 4). Stigma creates many deleterious avenues for those who experience a mental illness including inferior healthcare for various issues from cardiovascular disease (Solmi et al., Citation2021), to cancer screening (Mitchell et al., Citation2014). When such individuals do receive treatment, it can be involuntary, authoritarian, and widely coercive in nature, limiting the patients’ rights and freedoms (Sugiura et al., Citation2020). The repercussions from stigma have been expressed as being more harmful than the illnesses themselves (Thornicroft et al., Citation2016, p. 1123).

Nurses have attached stigma to mental illness to varying degrees, with their attitudes at times being more negative than those of the general public and other healthcare professionals (de Jacq et al., Citation2016). Nursing students have also been shown to share some of these negative attitudes (Poreddi et al., Citation2014), including authoritarian and socially restrictive attitudes (Palou et al., Citation2021), and attitudes that are also more pessimistic than those of the general public (Ewalds-Kvist et al., Citation2013). Such stigma among nurses can result in discriminatory practices such as diminished quality of, and even detrimental, nursing care (Thornicroft et al., Citation2007a). Given the ubiquity of mental health challenges, nurses in every specialty will meet patients who live with mental health conditions and in need of high-quality nursing care (Bingham & O'Brien, Citation2018). Undergraduate nursing education is an opportune time to positively influence students’ attitudes toward people experiencing a mental illness (Happell et al., Citation2019a). Rather than not acknowledging and not preventing the harmful, discriminatory, and dehumanizing practices like the one mentioned in the epigraph, undergraduate nursing education must cultivate nurses who actively destigmatize (Ross & Goldner, Citation2009).

Theoretical framework

Fox et al. (Citation2018) synthesized decades’ worth of stigma research to create the Mental Illness Stigma Framework (MISF). From the stigmatizers’ perspective, the MISF defines the mechanisms of stigma as stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination, which can be thought of as cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses. Prejudice has been theorized to be a stronger predictor of discrimination, even more than stereotypes (Thornicroft et al., Citation2007b). Therefore, this study focuses on the stigmatizers’ perspective and prejudice as the mechanism of stigma, because the centrality of prejudice makes it suitable for measurement and modification (Kenny et al., Citation2018).

Stigma and the nursing knowledge perspective

Willis et al. (Citation2008) stated that nursing is a process of humanization. Humanization is defined in the context of nursing as, “an open-minded, caring, intentional, thoughtful, and responsible unconditional acceptance and awareness of human beings as they are” (Willis et al., Citation2008, p. E33–E34). If stigma is dehumanization (Yanos, Citation2018), stigmatization can be considered the antithesis of nursing.

Undergraduate nursing education interventions

A review of studies measuring the impact of undergraduate nursing education interventions on the stigma attached to mental illness from 2000–2022 was conducted in preparation for the current study. Of the 37 studies found, nine included classroom interventions (24.3%), 18 included clinical interventions (48.6%), and 10 included both (27%). Since the interventions were diverse and 25 different instruments were used to measure stigma levels, results were varied and difficult to compare. Some research has shown that undergraduate mental health nursing courses have had a positive impact on students’ attitudes toward people living with a mental illness (Arbanas et al., Citation2018; Ciydem & Avci, Citation2022; İnan et al., Citation2019; Palou et al., Citation2021). Some clinical interventions, including traditional clinical rotations on acute hospital-based psychiatric units, were found to decrease stigmatizing attitudes (Bingham & O'Brien, Citation2018; Foster et al., Citation2019). Not all the results were positive with some traditional clinical rotations in psychiatric settings having no measurable impact on stigma (Çingöl et al., Citation2020; Stuhlmiller & Tolchard, Citation2019). Others found no significant impact of interventions that had a combination of classroom and clinical components (Martin et al., Citation2020; Tambag, Citation2018).

Gaps in the research and goals of the current study

Past research on nurses’ attitudes toward people living with a mental illness have made limited use of theoretical frameworks (de Jacq, Citation2018). Furthermore, a vast majority of the instruments used in stigma research lack psychometric validation (Fox et al., Citation2018). This lack can be seen in research conducted with nursing student samples as well (Palou et al., Citation2019). Additionally, of the 37 studies mentioned earlier, only 10 included a control group (27%) and four were conducted in the United States (10.8%). Only one study was specifically designed to measure prejudice against people with mental illness (Choi et al., Citation2016).

The current study aimed to address these gaps by applying a clear conceptual framework, reliable and valid instruments, a control group, and a sample located in the United States to assess the impact of an undergraduate mental health nursing course on students’ prejudice toward people living with a mental illness.

Methods

Study design

This study used a quasi-experimental, pretest-posttest, nonequivalent-groups design.

Ethical considerations

The Institutional Review Board of Teachers College, Columbia University granted approval for this study, protocol number 21–371. The dean of the nursing school granted study approval and the participants provided informed consent. Participants who completed both the pretest and the posttest were given a $10 gift card. This manuscript was written in compliance with the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) checklist.

Sample size

A power analysis was conducted using G*Power (Faul et al. Citation2007). For the two-way mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA), a power of 0.80, a small effect size of 0.15 and alpha level of 0.05 set the sample size at 90. The goal sample size was therefore set at 45 for the intervention group and 45 for the control group.

Participants and setting

This study used a convenience sample of undergraduate nursing students attending an accelerated bachelor of science in nursing (ABSN) program in New York City. The ABSN program requires that students have an earned bachelor’s degree in a non-nursing field. The sample consisted of two different cohorts of second semester students who were recruited in fall 2021 and spring 2022. The students were enrolled in either a mental health nursing course or a pediatric/maternal health nursing course alphabetically, using their last name. Students in the former course were assigned to the intervention group and those in the latter course to the control group.

Inclusion criteria were the ability to provide legal consent, voluntary participation, and enrollment in the program’s second term. Exclusion criteria included students who were absent from 30% or more of classroom lectures and students who missed clinical experiences. Exclusion criteria because of classroom absences were only applied to the intervention group as it cannot be said that absent students received the intervention as intended.

Procedure

Pretest data were collected on the first day of each course before any course content was presented. Posttest data were collected at the end of the semester after all classroom and clinical activities had been completed. All data were collected using an online questionnaire.

Interventions

Both 14-week courses had a classroom component held on Zoom due to the COVID-19 pandemic and a clinical component held in person. The pediatric/maternal health nursing course was chosen for the control group as it occurs at the same point in the ABSN program as the mental health nursing course. Up until that time, students in both groups had completed the exact same nursing courses. However, the pediatric/maternal health nursing course required a total of 60 classroom hours and 60 clinical hours versus the mental health course, which required 45 classroom and 30 clinical hours. The classroom portion of the mental health nursing course was co-taught by the first author. All other educational interventions were led by experienced ABSN educators.

Intervention group

Students were taught all chapters of the required text (Videbeck, Citation2020). The concept of stigma attached to mental illness was introduced in the first class and repeated throughout the course. Students were periodically asked to examine their own attitudes toward those who live with a mental illness. Individuals with a lived experience of a mental illness were always discussed using person-first language. Signs and symptoms of mental illnesses were approached with the utmost sensitivity and respect. Additionally, the idea of nursing as a process of humanization (Willis et al., Citation2008) with unconditional positive regard (Rogers, Citation1995) and radical acceptance (Linehan, Citation2021) was discussed at length and periodically. Videos and vignettes of individuals with a lived experience of a mental illness were utilized as a form of indirect contact; evidence has shown this is an effective way of reducing stigma (Corrigan et al., Citation2007). These first-person accounts shared the impact that stigma had on their lives and the resultant discrimination they experienced, at times from nurses.

Biomedical and psychosocial perspectives were presented for the etiology of each disorder studied in the course. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), was used to explore diagnostic criteria. Pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions were presented in tandem as treatment options. Though both biomedical and psychosocial perspectives were provided, it can be said that the biomedical model was the dominant model presented in the course as professional nurses need to be aware of numerous psychotropic medications, medication classes, mechanisms of action, intended effects, side effects, and pertinent interventions surrounding medication administration.

The students completed 30 h of clinical practice in hospital-based, locked, acute inpatient psychiatric units. Students set daily goals such as communicating therapeutically, attempting to adopt others’ perspectives, and providing compassionate nursing care. Students were given the opportunity to go on patient rounds and attend group therapy and were encouraged to engage with patients throughout their time on the unit. Students shadowed psychiatric nurses and took part in patients’ nursing care. Post-clinical conferences were used to debrief, share experiences, and address concerns that may have arisen.

Control group

The classroom component of the pediatric/maternal health nursing course used diverse teaching strategies through Zoom including lectures, case studies, research publications, and group discussions. There was very little overlap in the classroom content taught in both courses. However, postpartum depression was primarily taught here and was only discussed within the broader category of mood disorders in the mental health nursing course.

Clinical placements occurred within hospital-based pediatric, neonatal, and labor and delivery units. Clinical placements provided students the opportunity to interact, assess, perform nursing interventions, and conduct evaluations under the guidance of clinical instructors and unit staff nurses.

Instruments

Three shortened versions of the Prejudice toward People with Mental Illness (PPMI; Kenny et al., Citation2018) scale were used as created by Bizumic et al. (Citation2022): Prejudice toward People with Mental Illness, Shortened Version (PPMI-SV); Prejudice toward People with Depression, Shortened Version (PPD-SV); and Prejudice toward People with Schizophrenia, Shortened Version (PPS-SV). Each instrument contains 16 items rated on a 9-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating more self-reported prejudice. Each instrument yields a total score and four subscale scores. The instruments contain an almost equal number of positively phrased and negatively phrased items. Positively phrased items were reverse-scored.

Each instrument contains four facets of prejudice as subscales: fear/avoidance, unpredictability, authoritarianism, and malevolence. Fear/avoidance addresses the desire to socially distance and limit interaction because of a belief in the dangerousness of those experiencing a mental illness. Unpredictability measures the attitudes of uncertainty regarding the behavior of those living with a mental illness that limits desired interaction and perceived trustworthiness. Authoritarianism comprises attitudes about coercive control and the limitation of rights of those experiencing a mental illness. Finally, malevolence explores the beliefs of inferiority of those who experience a mental illness as well as a lack of compassion toward them. The full instruments as well as scoring instructions can be found in Bizumic et al. (Citation2022). Example items can be found in .

Table 1. Example instruments items concerning prejudice.

Reliability and validity

Bizumic et al. (Citation2022) demonstrated the convergent validity of the three instruments with moderate to strong correlations to known antecedents of prejudice: social dominance orientation, right-wing authoritarianism, and ethnocentrism. The shortened PPMI versions showed good reliability in a previous study (Richards et al., Citation2023), α = 0.73 − .85. They also showed very good reliability for the current study, α = 0.85 − .89. Detailed Cronbach’s alpha coefficients can be found in Supplementary Information, Table S1.

Data analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 26) was used to analyze the data. Two analyses were conducted, a per-protocol analysis that included participants who met inclusion criteria and avoided exclusion criteria; and an intent-to-treat analysis that included all participants with pretest and posttest data regardless of exclusion criteria. Using the general linear model approach, two-way mixed ANOVAs were used to assess differences in prejudice over time in both analyses.

Results

In total, 137 (84%) participants out of 163 completed both the pretest and posttest. There were 11 participants in the intervention group who were excluded from the per-protocol analysis as they missed 30% or more of the classroom lectures. As a result, 54 participants in the control group and 72 participants in the intervention were included in the per-protocol analysis.

Demographic characteristics

Ages ranged from 20 to 45. A majority of participants identified as women and the sample was multicultural with seven different ethnicities being reported. Demographic characteristics are summarized in .

Table 2. Demographic characteristics.

Preliminary assumptions checks

All assumptions for the two-way mixed ANOVAs were met and a detailed description of the assumptions checks can be found in Supplementary Information, Appendix S2.

Protocol for conducting two-way mixed ANOVAs

If a statistically significant two-way interaction between group and time was found, the simple main effects of group at both pretest and posttest are conducted, followed by an evaluation of the simple main effects of time for both groups. If a nonsignificant two-way interaction between group and time was found, only the main effect of time and main effect of group are conducted.

Total score results

Mental illness

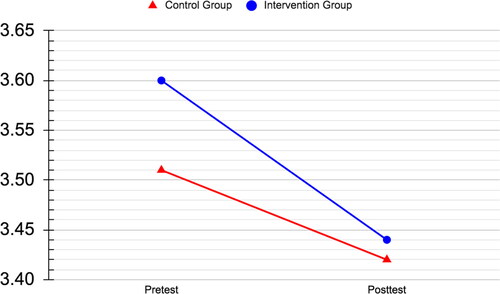

A statistically significant interaction was found between group and time in the self-reported prejudicial attitudes toward people living with a general mental illness, F(1, 124) = 4.97, p = 0.028, partial η2 = .038. No significant differences were found between the intervention and control groups at either pretest, posttest, or in the control group over time. However, a statistically significant decrease in the intervention group scores was noted over time, F(1, 71) = 4.72, p = 0.033, partial η2 = .062. Therefore, the intervention succeeded in reducing prejudicial attitudes toward the condition of general mental illness.

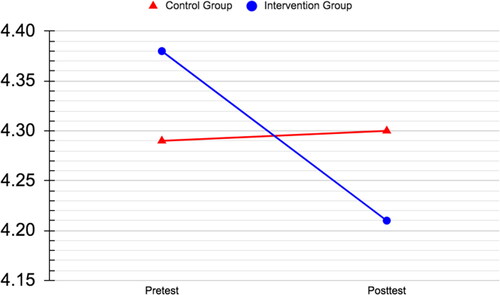

Depression

No statistically significant interaction was found between group and time in prejudicial attitudes toward people living with depression. The main effect of time showed a statistically significant decrease in prejudice, F(1, 124) = 7.29, p = 0.008, partial η2 = .056. Therefore, study participants showed a significant reduction in prejudice scores for depression over time, but no significant difference was found between the groups.

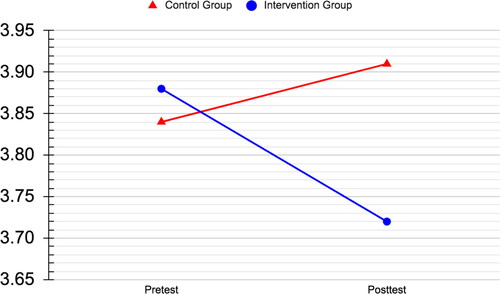

Schizophrenia

No statistically significant results were found in prejudicial attitudes toward people living with schizophrenia.

The two-way mixed ANOVA results are summarized in , (Figures 1–3).

Table 3. Two-way mixed ANOVAs for prejudice toward people living with general mental illness, depression, or schizophrenia: Total scores.

Subscale results: Fear/avoidance, unpredictability, authoritarianism, and malevolence

Only two subscales showed statistically significant interaction effects: fear/avoidance of individuals living with general mental illness, F(1, 124) = 9.68, p = 0.002, partial η2 = 0.072; and fear/avoidance of individuals living with schizophrenia, F(1, 124) = 9.16, p = 0.003, partial η2 = .069. In both cases, the intervention group showed statistically significant reductions in prejudice over time, general mental illness, F(1, 71) = 4.36, p = 0.040, partial η2 = 0.058; and schizophrenia, F(1, 71) = 13.94, p < 0.001, partial η2 = .164. Therefore, the intervention succeeded in reducing prejudicial attitudes of fear and avoidance toward the conditions of general mental illness and schizophrenia.

The main effect of time showed statistically significant decreases in prejudice scores realated to fear/avoidance of those living with depression, F(1, 124) = 9.37, p = 0.003, partial η2 = 0.070; the unpredictability of those living with depression, F(1, 124) = 12.41, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.091; and the unpredictability of those living with a general mental illness, F(1, 124) = 6.84, p = 0.010, partial η2 = .052. Therefore, study participants showed a significant reduction in prejudice over time, but no significant difference was found between groups.

Notably, no statistically significant results were found concerning authoritarianism or malevolence.

The subscales data are reported in Supplementary Information, Tables S3–S6.

A summary of subscale results can be found in .

Table 4. Summary of subscale results.

Intention-to-treat analysis

Two differences were found in the intention-to-treat analysis that were not present in the per-protocol analysis. Both differences resulted in higher prejudice scores for the intervention group providing evidence that the intervention had a meaningful impact when received as intended. A thorough description of the results can be found in Supplementary Information, Appendix S7.

Discussion

The study results show that an undergraduate mental health nursing course had a positive impact on nursing students’ attitudes toward people living with a general mental illness. However, prejudice toward people living with depression decreased in both groups from pre to posttest, and therefore cannot be attributed solely to the intervention. The highest degree of negative attitudes was found toward people living with schizophrenia, yet no significant impact of the intervention was found. Where the intervention of the undergraduate mental health nursing course was impactful, the reasons may be due to the students’ exposure to new knowledge including the concepts, mechanisms, and first-person accounts of the negative impact of stigma.

In the clinical rotations, opportunities to interact with individuals living with a mental health condition may have decreased unsubstantiated prejudicial attitudes. The students interacted with those who were experiencing acute mental health conditions with the goal of using therapeutic communication to help that individual be seen, heard, and empathized with. These interactions may have served to deconstruct pejorative narratives associated with mental illness, challenging perceptions of dangerousness and advocating for empathetic engagement over fearful avoidance.

In a previous quasi-experimental single-group study (Richards et al., Citation2023), a significant decrease in student prejudice for all three conditions was found after completing the same intervention. In the current study, which included a nonequivalent control group, the significant decrease was limited to general mental illness. However, similar to the previous study’s results, paired-samples t tests of the current intervention group revealed a significant decrease between pretest and posttest scores for all three mental health conditions (Supplemental Information, Table S8). Thus, the stronger design did not alter statistical significance, but revealed a more accurate finding.

This study’s varied findings are not consistent with previous research that found a largely positive impact of undergraduate mental health nursing courses on students’ attitudes toward people living with a mental illness (Arbanas et al., Citation2018; Chan & Cheng, Citation2001; Ciydem & Avci, Citation2022; İnan et al., Citation2019; Madianos et al., Citation2005; Markström et al., Citation2009; Palou et al., Citation2021). However, none of those studies used a control group. This study’s findings are in partial agreement with three similar studies that had a limited or no impact on student attitudes (Martin et al., Citation2020; O’Ferrall-González et al., Citation2020; Tambag, Citation2018).

As O’Ferrall-González et al. (Citation2020) suggested, it is possible that registered nurses teach stigmatizing ideas, passively or actively, to students in clinical settings. Nurses who work in acute inpatient psychiatric settings, like those in the current study, frequently had more stigmatizing attitudes than those who worked in community mental health settings (de Jacq et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, research by Moxham et al. (Citation2016) suggests that nontraditional clinical sites outside of acute inpatient units, such as recovery camps, are associated with significantly lower levels of fear-based prejudice toward individuals with mental illness compared to traditional hospital-based acute inpatient psychiatric settings like the one utilized in the present study. These community mental health settings could expose students to professional nurses who have more positive attitudes than their inpatient counterparts. To understand these results, a closer look at the subscales is needed.

Fear/avoidance

Undergraduate mental health nursing courses have been found to decrease the fear of and desire for social distance from those living with a mental illness (Foster et al., Citation2019). This is reflected in the current study as two out three fear/avoidance scores, general mental illness and schizophrenia, were significantly lower in the intervention group. This may be due to the classroom content aimed at demystifying the experience of mental illness and humanizing those who experience it. Additionally, videos of first-hand accounts of those with lived experience of a mental health condition were shown throughout the classroom portion of the intervention and served as a form of indirect contact, which has been shown to decrease the desire for avoidance (Corrigan et al., Citation2007). This was paired with the direct contact on the acute inpatient psychiatric units, which has also been shown to decrease fear in nursing students (Bingham & O'Brien, Citation2018).

There was a significant reduction in the fear/avoidance score in the condition of depression for both groups over time that was not attributable specifically to the intervention. It is possible that this decrease may be attributed to the control group being taught about postpartum depression, and increased classroom time and clinical experiences.

Unpredictability

Unpredictability scores were the highest of all the subscales, yet there was no decrease in prejudice specific to the intervention group. There was a significant reduction in scores over time for the general mental illness and depression conditions. It is possible that the increased classroom and clinical experiences of the control group had an impact here. Registered nurses have reported beliefs in the unpredictability of those who have a mental illness (de Jacq et al., Citation2016). The acute inpatient psychiatric units may not have positively impacted students’ attitudes as much as a community mental health setting would. There, students would interact with individuals who are further along in their recovery while being exposed to the more positive attitudes of registered nurses working in the community.

Authoritarianism and malevolence

The intervention had no measurable impact on attitudes of authoritarianism or malevolence. This is in alignment with a previous study, where the same course had no measurable impact on nursing students from the same nursing school (Richards et al., Citation2023). However, this study’s findings do not support previous research, none of which used a control group, that showed that students’ authoritarian attitudes decreased after a mental health nursing course (Chan & Cheng, Citation2001; Madianos et al., Citation2005; Palou et al., Citation2021).

Students in the intervention group may have adopted some of the authoritarian attitudes of professional nurses in the acute inpatient mental health clinical environment. Professional nurses have self-reported authoritarian attitudes, and nurses in acute inpatient psychiatric settings have reported higher levels of stigmatizing attitudes than nurses who worked in community mental health settings (de Jacq et al., Citation2016). Of the data available from 25 states, involuntary commitment has increased at three times the rate of the population’s increase from 2011–2018 (Lee & Cohen, Citation2021). Anecdotally, the principal researcher has led clinical groups on the acute inpatient psychiatric units that were used in the current study. It was not a rare occasion for the majority of patients on the unit to be involuntarily committed. It is possible that the authoritarian attitudes of the intervention group remained unchallenged as the clinical settings reinforced them through the use of authoritarian interventions.

Scholars have criticized biomedical-oriented education for not only being ineffectual in addressing stigmatizing attitudes but also promoting stigmatizing attitudes while decreasing belief in recovery (Lebowitz & Appelbaum, Citation2019). It has also been suggested that the stigmatizing attitudes of professional nurses are fueled by the nursing field’s adoption of the biomedical model (O’Ferrall-González et al., Citation2020).

Lakeman and Cutcliffe (Citation2009) proposed that nursing education must provide students with different forms of knowledge without relying solely on a biomedical-centric curriculum. A balanced and holistic nursing education begets balanced and holistic nursing care. Promoting autonomy and humanization while rejecting authoritarian and coercive nursing practices is largely “an appeal to values and ethics” (Lakeman & Cutcliffe, Citation2009, p. 203). Barbara Carper (Citation1978) posited that there are four forms of nursing knowledge: empirics, esthetics, personal knowledge, and ethics. Nursing schools, despite being aware of the shortcomings of empirical biomedical-oriented education, still teach this approach to students with “insufficient levels of criticality” (Grant, Citation2015, p. e52). Though it is challenging to precisely gauge, it is possible that an over-representation of empirical biomedical knowledge in the current intervention may have crowded out other forms of knowledge, such as esthetical, ethical, and personal knowledge, and allowed the stigmatizing authoritarian and malevolent ideals to remain unchallenged.

The prejudice levels for malevolence were lower than that of the other subscales. Considering the possibility that these lower scores might reflect limitations in a self-report instrument, the current data were compared to past research (Bizumic et al., Citation2022) that used the same instruments. Notably, mental health professionals scored significantly lower (p < 0.001) on all malevolence measures compared to the posttest intervention group scores in this study. Likewise, untrained individuals in the general population displayed some lower malevolence and authoritarianism scores compared to the post-intervention group (Supplemental Information, Table S9). This provides evidence that there is ample opportunity to decrease authoritarian and malevolent facets of prejudice. An elaborate description of the findings can be found in Supplemental Information, Appendix S10.

Intention-to-treat

The two differences in the intention-to-treat analysis resulted in higher levels of prejudice when those who did not receive the complete intervention were included. This provides evidence that receiving the intervention as intended had a meaningful impact in reducing prejudice.

Limitations

First, this study did not use randomization. Second, all study instruments were self-report measures and findings could be impacted by a response bias. Third, due to the COVID-19 the classroom portions of the intervention which would normally be held in person were conducted over Zoom. Lastly, the convenience sample of undergraduate nursing students in New York City limits generalizability.

Implications for nursing education and future research

To address the stigma attached to mental illness, its presence within the curriculum must first be acknowledged through deep collaborative discussion, exploration, and contemplation with students. Curriculum revisions should consider a balanced epistemology, moving beyond a purely biomedical focus to incorporate diverse perspectives on causes and treatments of mental illness. Additionally, expanding clinical placements beyond acute inpatient settings to include recovery-oriented environments may cultivate a deeper understanding of the recovery process. Measuring the impact of the course on student attitudes as part of each semester’s curriculum would be invaluable to tracking progress.

Moreover, curricula that have been created and presented in collaboration between nurse educators and those who have lived experience of mental health conditions have been shown to decrease stigma both quantitatively (Byrne et al., Citation2014; Happell et al., Citation2019b) and qualitatively (Happell et al., Citation2019c). These collaborative initiatives can be adapted to any undergraduate mental health nursing course and have the benefit of authenticity and empowerment. This approach not only provides unique and invaluable perspectives and teaching methods, but also demonstrably diminishes stigmatizing attitudes.

Future research must strongly consider the inclusion of control groups in their study designs; the current study has shown the importance of stronger design compared to what has been used historically. It is not possible to demonstrate that the positive results of such studies are because of the intervention or the maturation effects, threat of testing, or response bias. Without a control group, effect sizes may also be falsely inflated.

Replication studies are needed in order to verify the current findings. Causal studies that examine the relationship between the biomedical explanations of mental illness and prejudice are required to explore the impact of biomedical-centric curricula. Additionally, studies need to explore the degree to which prejudice translates to discrimination in nursing.

Conclusion

The current study has provided evidence that prejudicial attitudes are not unchangeable and positive attitudes can be cultivated. The undergraduate mental health nursing course decreased prejudice toward people living with a general mental illness. However, there was no significant reduction in prejudice for the condition of depression that was specific to the intervention; and schizophrenia, which was viewed most negatively, saw no significant reduction of prejudice in the overall measure. Distinct components of prejudice that are amenable to change including fear/avoidance have been identified as well as those that are resistant to present interventions including authoritarian and malevolent attitudes.

Hinshaw and Stier (Citation2008) poignantly stated, “Even a small amount of stigma among professionals will translate into many thousands of negative social interactions” (p. 384). Undoubtedly, there is much progress to be made and undergraduate nursing education has the great opportunity to create many thousands of positive interactions, promote wellbeing, facilitate humanization, and challenge the stigma attached to mental illness.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (55 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Michele L. Roberts, and Dr. Ann Marie P. Mauro for scholarly guidance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no competing interests to declare and that there is no funding associated with the research presented in this article. The authors confirm that all authors meet ICMJE criteria for authorship credit (www.icmje.org).

Figure 1. Interaction of group and time for prejudice toward people living with mental illness.

Note: N = 126. Figure zoomed in to show trend.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Arbanas, G., Bosnjak, D., & Sabo, T. (2018). Impact of a nursing in psychiatry course on students’ attitudes toward mental health disorders. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 56(3), 45–51. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20171024-01

- Bingham, H., & O'Brien, A. J. (2018). Educational intervention to decrease stigmatizing attitudes of undergraduate nurses towards people with mental illness. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(1), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12322

- Bizumic, B., Gunningham, B., & Christensen, B. K. (2022). Prejudice towards people with mental illness, schizophrenia, and depression among mental health professionals and the general population. Psychiatry Research, 317, 114817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114817

- Byrne, L., Platania-Phung, C., Happell, B., Harris, S., Sci, D. H., Hlth Nurs, M. M., & Bradshaw, J. (2014). Changing nursing students’ attitudes to consumer participation in mental health services: A survey study of traditional and lived experience-led education. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35(9), 704–712. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2014.888604

- Carper, B. (1978). Fundamental patterns of knowing in nursing. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science, 1(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-197810000-00004

- Chan, S., & Cheng, B. S. (2001). Creating positive attitudes: The effects of knowledge and clinical experience of psychiatry in student nurse education. Nurse Education Today, 21(6), 434–443. https://doi.org/10.1054/nedt.2001.0570

- Choi, H., Hwang, B., Kim, S., Ko, H., Kim, S., & Kim, C. (2016). Clinical education in psychiatric mental health nursing: Overcoming current challenges. Nurse Education Today, 39, 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.01.021

- Çingöl, N., Karakaş, M., Zengin, S., & Çelebi, E. (2020). The effect of psychiatric nursing students’ internships on their beliefs about and attitudes toward mental health problems; a single-group experimental study. Nurse Education Today, 84, 104243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104243

- Ciydem, E., & Avci, D. (2022). Effects of the psychiatric nursing course on students’ beliefs toward mental illness and psychiatric nursing perceptions in Turkey. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 58(1), 348–354. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12796

- Corrigan, P. W., Larson, J., Sells, M., Niessen, N., & Watson, A. C. (2007). Will filmed presentations of education and contact diminish mental illness stigma? Community Mental Health Journal, 43(2), 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-006-9061-8

- de Jacq, K., Norful, A. A., & Larson, E. (2016). The variability of nursing attitudes toward mental illness: An integrative review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 30(6), 788–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2016.07.004

- de Jacq, K. (2018). Nurses’ attitudes toward mental illness (Publication No. 10746094). [Doctoral dissertation, Columbia University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

- Ewalds-Kvist, B., Högberg, T., & Lützén, K. (2013). Student nurses and the general population in Sweden: Trends in attitudes towards mental illness. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 67(3), 164–170. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2012.694145

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193146

- Foster, K., Withers, E., Blanco, T., Lupson, C., Steele, M., Giandinoto, J. A., & Furness, T. (2019). Undergraduate nursing students’ stigma and recovery attitudes during mental health clinical placement: A pre/post-test survey study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(5), 1065–1077. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12634

- Fox, A. B., Earnshaw, V. A., Taverna, E. C., & Vogt, D. (2018). Conceptualizing and measuring mental illness stigma: The mental illness stigma framework and critical review of measures. Stigma and Health, 3(4), 348–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000104

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Simon & Schuster.

- Grant, A. (2015). Demedicalising misery: Welcoming the human paradigm in mental health nurse education. Nurse Education Today, 35(9), e50–e53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.05.022

- Happell, B., Platania-Phung, C., Scholz, B., Bocking, J., Horgan, A., Manning, F., Doody, R., Hals, E., Granerud, A., Lahti, M., Pullo, J., Vatula, A., Ellilä, H., van der Vaart, K. J., Allon, J., Griffin, M., Russell, S., MacGabhann, L., Bjornsson, E., & Biering, P. (2019a). Nursing student attitudes to people labeled with “mental illness” and consumer participation: A survey-based analysis of findings and psychometric properties. Nurse Education Today, 76, 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.02.003

- Happell, B., Platania-Phung, C., Scholz, B., Bocking, J., Horgan, A., Manning, A., Doody, R., Hals, E., Granerud, A., Lahti, M., Pullo, J., Vatula, A., Koski, J., van der Vaart, K. J., Allon, J., Griffin, M., Russell, S., MacGabhann, L., Bjornnson, E., & Biering, P. (2019b). Changing attitudes: The impact of expert by experience involvement in mental health nursing education: An international survey study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(2), 480–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12551

- Happell, B., Waks, S., Bocking, J., Horgan, A., Manning, F., Greaney, S., Goodwin, J., Scholz, B., van der Vaart, K. J., Allon, J., Hals, E., Granerud, A., Doody, R., MacGabhann, L., Russell, S., Griffin, M., Lahti, M., Ellilä, H., Pulli, J., … Biering, P. (2019c). I felt some prejudice in the back of my head: Nursing students’ perspective on learning about mental health from Experts by Experience. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 26(7–8), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12540

- Hinshaw, S. P., & Stier, A. (2008). Stigma as related to mental disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4(1), 367–393. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141245

- İnan, F. Ş., Günüşen, N., Duman, Z. Ç., & Ertem, M. Y. (2019). The impact of mental health nursing module, clinical practice and an anti-stigma program on nursing students’ attitudes toward mental illness: A quasi-experimental study. Journal of Professional Nursing: Official Journal of the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 35(3), 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2018.10.001

- Kenny, A., Bizumic, B., & Griffiths, K. M. (2018). The Prejudice towards people with mental illness (PPMI) scale: Structure and validity. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 293. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1871-z

- Lakeman, R., & Cutcliffe, J. R. (2009). Misplaced epistemological certainty and pharmaco-centrism in mental health nursing. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16(2), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01362.x

- Lebowitz, M. S., & Appelbaum, P. S. (2019). Biomedical explanations of psychopathology and their implications for attitudes and beliefs about mental disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15(1), 555–577. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095416

- Lee, G., & Cohen, D. (2021). Incidences of involuntary psychiatric detentions in 25 US states. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 72(1), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900477

- Linehan, M. M. (2021). Building a life worth living: A memoir. Random House Trade Paperbacks.

- Madianos, M. G., Priami, M., Alevisopoulos, G., Koukia, E., & Rogakou, E. (2005). Nursing students’ attitude change towards mental illness and psychiatric case recognition after a clerkship in psychiatry. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 26(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840590901635

- Markström, U., Gyllensten, A. L., Bejerholm, U., Björkman, T., Brunt, D., Hansson, L., Leufstadius, C., Sandlund, M., Svensson, B., Ostman, M., & Eklund, M. (2009). Attitudes towards mental illness among health care students at Swedish universities – A follow-up study after completed clinical placement. Nurse Education Today, 29(6), 660–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2009.02.006

- Martin, A., Krause, R., Chilton, J., Jacobs, A., & Amsalem, D. (2020). Attitudes to psychiatry and to mental illness among nursing students: Adaptation and use of two validated instruments in preclinical education. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 27(3), 308–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12580

- Miller, D., & Hanson, A. (2016). Committed: The battle over involuntary psychiatric care. John Hopkins University Press.

- Mitchell, A. J., Santo Pereira, I. E., Yadegarfar, M., Pepereke, S., Mugadza, V., & Stubbs, B. (2014). Breast cancer screening in women with mental illness: Comparative meta-analysis of mammography uptake. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 205(6), 428–435. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147629

- Moxham, L., Taylor, E., Patterson, C., Perlman, D., Brighton, R., Sumskis, S., Keough, E., & Heffernan, T. (2016). Can a clinical placement influence stigma? An analysis of measures of social distance. Nurse Education Today, 44, 170–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.06.003

- O’Ferrall-González, C., Almenara-Barrios, J., García-Carretero, M. Á., Salazar-Couso, A., Almenara-Abellán, J. L., & Lagares-Franco, C. (2020). Factors associated with the evolution of attitudes towards mental illness in a cohort of nursing students. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 27(3), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12572

- Palou, R. G., Prat Vigué, G., Torà Suarez, N., Romeu Labayen, M., & Tort Nasarre, G. (2021). The development of positive attitudes toward mental health among university nursing students: Countering the role of social desirability. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 58(4), 1680–1690. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12976

- Palou, R. G., Prat Vigué, G., & Tort Nasarre, G. (2019). Attitudes and stigma toward mental health in nursing students: A systematic review. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 56(2), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12419

- Poreddi, V., Thimmaiah, R., Pashupu, D. R., Badamath, S., Ramachandra, (2014). Undergraduate nursing students’ attitudes towards mental illness: Implications for specific academic education. Indian Journal of Psychological medicine, 36(4), 368–372. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.140701

- Richards, S. J., O'Connell, K. A., & Dickinson, J. K. (2023). Acknowledging stigma: Levels of prejudice among undergraduate nursing students toward people living with a mental illness – A quasi-experimental single-group study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 44(8), 778–786. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2023.2229438

- Rogers, C. R. (1995). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Ross, C. A., & Goldner, E. M. (2009). Stigma, negative attitudes and discrimination towards mental illness within the nursing profession: A review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16(6), 558–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01399.x

- Solmi, M., Fiedorowicz, J., Poddighe, L., Delogu, M., Miola, A., Høye, A., Heiberg, I. H., Stubbs, B., Smith, L., Larsson, H., Attar, R., Nielsen, R. E., Cortese, S., Shin, J. I., Fusar-Poli, P., Firth, J., Yatham, L. N., Carvalho, A. F., Castle, D. J., Seeman, M. V., & Correll, C. U. (2021). Disparities in screening and treatment of cardiovascular diseases in patients with mental disorders across the world: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 47 observational studies. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(9), 793–803. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010031

- Stuhlmiller, C., & Tolchard, B. (2019). Understanding the impact of mental health placements on student nurses’ attitudes towards mental illness. Nurse Education in Practice, 34, 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.06.004

- Sugiura, K., Mahomed, F., Saxena, S., & Patel, V. (2020). An end to coercion: Rights and decision-making in mental health care. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 98(1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.19.234906

- Tambag, H. (2018). Effects of a psychiatric nursing course on beliefs and attitudes about mental illness. International Journal of Caring Sciences, 11(1), 420–426.

- Thornicroft, G., Mehta, N., Clement, S., Evans-Lacko, S., Doherty, M., Rose, D., Koschorke, M., Shidhaye, R., O'Reilly, C., & Henderson, C. (2016). Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. Lancet (London, England), 387(10023), 1123–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00298-6

- Thornicroft, G., Rose, D., & Kassam, A. (2007a). Discrimination in health care against people with mental illness. International Review of Psychiatry (Abingdon, England), 19(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260701278937

- Thornicroft, G., Rose, D., Kassam, A., & Sartorius, N. (2007b). Stigma: Ignorance, prejudice or discrimination? The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 190(3), 192–193. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025791

- Videbeck, S. L. (2020). Psychiatric-mental health nursing (8th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Willis, D. G., Grace, P. J., & Roy, C. (2008). A central unifying focus for the discipline, facilitating humanization, meaning, choice, quality of life, and healing in living and dying. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science, 31(1), E28–E40. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ANS.0000311534.04059.d9

- Yanos, P. T. (2018). Written-off: Mental health stigma and the loss of human potential. Cambridge University Press.