Abstract

Safewards reduces conflict and containment on adult inpatient wards but there is limited research exploring the model in Children and Young People (CYP) mental health services. We investigated whether Safewards can be successfully implemented on twenty CYP wards across England. A process and outcomes evaluation was employed, utilizing the Integrated Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Sciences (i-PARiHS) framework. Existing knowledge and use of Safewards was recorded via a self-report benchmarking exercise, verified during visits. Implementation of the 10 Safewards components on each ward was recorded using the Safewards Organizational Fidelity measure. Data from 11 surveys and 17 interviews with ward staff and four interviews with project workers were subject to thematic analysis and mapped against the four i-PARiHS constructs. Twelve of the 20 wards implemented at least half of the Safewards interventions in 12 months, with two wards delivering all 10 interventions. Facilitators and barriers are described. Results demonstrated Safewards is acceptable to a range of CYP services. Whilst implementation was hindered by difficulties outlined, wards with capacity were able and willing to implement the interventions. Results support the commissioning of a study to evaluate the implementation and outcomes of Safewards in CYP units.

Introduction

Relative to other healthcare settings, psychiatric inpatient wards can present unique challenges and frequently report higher levels of conflict behaviors by patients (e.g. verbal aggression, suicide attempts, alcohol use, and absconding), and use of containment measures by staff (often called restrictive practices including coerced medication, seclusion, and restraint) to maintain safety (CQC, Citation2017; Thibaut et al., Citation2019).

There are recognized negative consequences with the use of containment, including disturbance of the therapeutic environment and relationships between patients and ward staff, as well as a negative influence on patients’ decisions to seek subsequent health care (Butterworth et al., Citation2022). Moreover, the practice of physical restraint has warranted global concern due to the associated physical and psychological trauma for both patients and staff (Cusack et al., Citation2018), and, at worst, fatalities (Duxbury et al., Citation2011; INQUEST, Citation2017). Good practice guidelines suggest the use of restrictive practices should be a last resort for staff (Department of Health, Citation2014). There is a need for evidence-based interventions to reduce rates of conflict and containment within inpatient wards and numerous interventions have been developed to address this need (Baker et al., Citation2021), including Safewards (Bowers et al., Citation2014).

Safewards

Safewards has been shown to reduce conflict and containment on younger adult wards (Bowers et al., Citation2015; Dickens et al., Citation2020; Nawaz et al., Citation2021). Within Safewards, “conflict” is defined as patient behaviors that could harm staff and/or patients, and “containment” as staff measures to prevent, manage and reduce conflict that also have the potential to cause harm (Bowers, Citation2014). Safewards is built from a theoretical and explanatory model of the generation and maintenance of conflict and containment (Bowers et al., Citation2014). This model maps six areas of potential flashpoint-originating factors within wards including (1) staff team, (2) physical environment, (3) patient community, (4) patient characteristics, (5) outside hospital, and (6) regulatory framework (7). These six domains may trigger “flashpoints” for staff and patients that can increase the probability of conflict and/or containment behaviors. The model also identifies staff and patient modifiers that can increase or decrease the likelihood of conflict and/or containment.

Safewards incorporates 10 interventions for wards that collectively aim to reduce or manage these “flashpoints” in such a way as to reduce the probability of conflict or containment (see ). The initial randomized controlled trial of the model demonstrated reduced rates of containment across inpatient wards by 26.4% and conflict by 15% relative to a control intervention (Bowers et al., Citation2015). These findings led to recognition of the model within UK guidelines for reducing restrictive practices (NICE, Citation2015).

Table 1. The 10 Safewards interventions (from www.safewards.net).

The free dissemination of Safewards via virtual platforms (www.safewards.net) and recognition that implementation requires minimum training for experienced staff, has led to global interest and roll-out of the model. As a result, Safewards has been translated into at least 10 languages and implemented in various mental healthcare settings and countries. Three independent systematic reviews have reported largely positive findings. Finch et al. (Citation2021), reviewed 13 studies and concluded that Safewards generally has a positive effect and can help reduce conflict and containment in acute ward settings, whilst recognizing the need for more high-quality research. Ward-Stockham et al. (Citation2022) included 14 studies that evaluated effectiveness as well as staff and service users’ perceptions, and found that Safewards improved cohesion, therapeutic relationships, and ward atmosphere. Mullen et al. (Citation2022) conducted an integrative literature review of Safewards within inpatient and forensic mental health units and included 19 papers. They concluded that Safewards can be effective in reducing containment and conflict within inpatient mental health and forensic mental health units, although this outcome varied across the literature. This review also revealed the limitations of fidelity measures, the importance of involving staff in implementation and the need for greater inclusion of patient perspectives.

Despite growing evidence for the use of Safewards within mental health settings, there is a scarcity of literature exploring the application of the model in Children and Young People (CYP) mental health services (Baker et al., Citation2022). Fletcher et al. (Citation2017) demonstrated successful implementation on adolescent psychiatric wards in Victoria, Australia, however, subsequent research remains limited to small studies (Hottinen et al., Citation2020; Yates & Lathlean, Citation2022).

Children and young people’s services

Reports indicate that, retrospectively, at least half of adults with severe mental health problems experienced their first symptoms by the age of 18 (Jones, Citation2013). Psychiatric inpatient wards for children and young people (CYP) are an integral component of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) in many developed countries and can be viewed as proactively working to reduce mental health problems in future adults.

The last two decades have witnessed an expansion of available CAMHS beds within services in England, rising from 844 to 1,368 beds across 115 wards. This growth in capacity coincides with reports showing a 35% increase in admission rates within CAMHS in 2019/2022 relative to 2018/2019 (Hayes et al., Citation2022). Given the known effects on children and young people following the recent pandemic (Panda et al., Citation2021), the demand for care in inpatient wards looks set to continue.

All psychiatric service providers have concerns about providing safe care, including those for young people. Yet inpatient care often results in high levels of “conflict” behaviors (e.g. verbal aggression, suicide attempts, absconding) exhibited by patients, but also high levels of staff “containment” behaviors (e.g. extra or coerced medication, seclusion, and restraint) (Baker et al., Citation2022). These containment behaviors are often collectively described as “restrictive practices”.

The United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNICEF, Citation1990) states that deprivation of a child’s liberty is only acceptable as: a last resort, for the minimal time needed, suitable to their well-being, and proportionate to the circumstances. Yet global figures reported in Baker et al. (Citation2022) review show high use of restrictive practices in various CYP services, with between a quarter and a half of residents experiencing restrictive practices including seclusion and restraint. In the UK, national data reported that use of restraint on CYP wards was notably higher than reported by adult inpatient mental health wards (NHS Benchmarking, Citation2018).

In response, in October 2019, NHS England/Improvement (NHSE/I) announced the launch of a Quality Improvement Taskforce for inpatient CYP mental health related services. One aim of the taskforce was to support wards to explore how to reduce the use of restrictive practices. As part of this, NHSE/I commissioned an 18-month service improvement project to assist 20 inpatient CYP wards to implement Safewards. This paper reports on the evaluation of the implementation of Safewards in CYPMH inpatient wards across England.

Methods

Aims/objectives

To explore whether and how Safewards can be successfully implemented on CYP wards.

To identify whether the ideas and theories underpinning the Safewards model and interventions are relevant when applied to CYP wards and to identify any revisions required.

To collect and analyze mixed methods data including benchmarking and fidelity measures, survey data and interviews with ward staff implementing Safewards, and interviews with Safewards project workers supporting the implementation.

Study design

A mixed method process and outcomes evaluation was adopted, informed by the integrated-Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (i-PARIHS) framework (Harvey & Kitson, Citation2015), with 20 Children and Young People Mental Health (CYPMH) inpatient wards across England.

Various approaches exist to assist planning, guiding, and evaluating implementation efforts with more than 170 being mentioned within recent research (Birken et al., Citation2017). The i-PARIHS is a conceptual framework characterized by interplaying factors that impact successful implementation. It has been used for retrospective and prospective implementation evaluations (Hill et al., Citation2017) and focuses on five key aspects of research implementation in health services: (1) the characteristics of the innovation; (2) the context or settings for the innovation; (3) the level and nature of engagement of the recipients implementing the innovation; (4) the facilitation provided to support implementation; and (5) the outcomes of the implementation.

Participants

Twenty CYPMH inpatient wards across England were selected by NHSE/I as suitable for the project. Further screening measures were applied by the Safewards implementation team. To be eligible to participate, wards were required to have a core set of identified permanent staff and clear leadership. The selected wards were split across five specialities that included:

Ten general acute child and adolescent units,

Three psychiatric intensive care units (PICU),

Three specialist eating disorder units,

Three secure units (one low secure, two medium secure)

One specialist unit caring for children under 13 years of age.

The wards were geographically spread across England. Due to the commissioning and provision of CYPMH inpatient services in England, the wards were run by a mixture of National Health Service (NHS) and independent providers. Details of the twenty sites are outlined in .

Table 2. Wards selected for the Safewards implementation project.

At the start of the project, three of the 10 general acute units and the unit for children under the age of 13 were effectively working as eating disorder units due to the identified needs of the young people admitted and the care being provided. Only one unit was single sex. The number of commissioned beds on each ward varied from nine to 28, however, during the implementation period four wards experienced long term increases and/or decreases in bed numbers while others experienced temporary reductions due to lack of staff or outbreaks of COVID-19.

Seven wards were identified as effectively providing an eating disorder service. This included three specialized units, three general adolescent units whose patients were all or predominantly being treated for an eating disorder, and the under 13s ward. Consequently, the project was able to see this group as a sub-set of the 20 wards and we conducted a separate analysis of Safewards in CYP eating disorder wards. This analysis will be presented as a separate paper.

Implementation team

A Safewards Implementation Team based at a university provided support to staff on each of the CYP units to implement Safewards, and a second team conducted an evaluation of the CYP Safewards implementation project. The implementation team consisted of a Clinical Supervisor (CS) and four project workers. GB, a nurse and part of the original Safewards research team, has assisted the implementation of Safewards in numerous hospitals and wards in the UK and internationally. He was appointed to lead and oversee implementation of Safewards across the 20 wards and to provide support to four project workers. Tasks included: (1) Initial design and set up of project (2) Organization of advisory groups (3) Selection and screening of participating wards in conjunction with NHSE/I Head of CYP taskforce (4) Design and delivery of Project Worker training (5) Supervision of project workers (6) Facilitation of external events and report writing.

Four mental health nurse project workers were recruited who had previous experience of the implementation of Safewards within adult services. The Safewards project workers were each employed for 11 hours a week for 12 months under the supervision of the CS and allocated to four regional clusters of five wards each to provide support and advice. The original design of the project workers’ role with wards was to:

Deliver Safewards information/training to ward leads and staff.

Assist the ward to develop a Safewards development plan.

Provide feedback to the organizational lead.

Support and monitor progress of the Safewards Development Plan

There were several barriers to this design, which will be discussed below. Subsequently, each project worker had to adapt the original plan to best suit the needs of the individual wards, given the pressures and barriers to implementation the wards experienced.

Project steering group

A Steering Group was convened to support, guide, and oversee the development of the project with representatives from major stakeholders including: (a) NHSE/I representative (specific to the CYP taskforce) (Chair) and an NHSE project manager, (b) Two Parents of CYP who have experienced restrictive practices, (c) CAMHS Clinical Reference Group representative, (d) Specialist advisor for autism, (e) Specialist advisor for learning disabilities, (f) Specialist advisor for mental health (g) Specialist advisor for secure settings, and (h) Four CYP with lived experience of CAMHS inpatient services.

The Steering Group met with the Project Lead, the CS and research assistant remotely five times during the project to provide advice, help resolve any issues of access to services, and to support dissemination of outcomes.

Evaluation team

Overall project management was provided by AS, a co-investigator on the original Safewards trial, who led on the design and conduct of the evaluation.

A research assistant (MC, followed by RA) was appointed to undertake the evaluation of the project. Duties included preparing data collection materials, conducting interviews, collating, inputting, checking, cleaning, and analyzing data from the participating sites and staff, drafting progress and final reports, presentations, and paper(s) for publication as well as providing administrative support for the project. Additional support was provided by another researcher (UF).

Implementation process

The first 12 months provided an intensive implementation programme led by the project workers, followed by a six-month package of lower-level support by the CS to embed practice and culture change. All wards in the programme received the following:

Safewards information and support for ward leads. This included information on the model and the 10 interventions, planning the engagement of both staff and young people, and the development of an initial Safewards Development Plan for the ward.

Monthly follow-up visits. Project Workers visited the ward leads virtually or on site to review Implementation Plans and advise.

Access to two Community of Practice Days. These were meetings where wards were invited to get together in regional clusters (five wards in four clusters) to share progress and provide peer support.

Intermittent supervision. Negotiated between the ward leads and project workers to offer supportive supervision of the project between support visits.

In the following six-month period, participating wards had access to:

Follow-up visit at 15 and 18 months to monitor and support progress.

Third Community of Practice Day/Celebration Event.

Data collection

Benchmarking and fidelity measure data

Prior to implementation, preexisting knowledge and use of Safewards within wards was identified and recorded via a self-report benchmarking exercise completed by ward leads. This data was then verified during visits by the Safewards project workers/clinical supervisor. Subsequent implementation of Safewards was charted against this initial data.

Within each ward, Safewards Organizational Fidelity checks were conducted across the implementation period to measure the degree of implementation of the 10 interventions. A combination of self-report and ward visits by the project team to verify fidelity using the Safewards Fidelity Checklist was employed (James et al., Citation2017). Completing the checklist alongside skilled observation described the different ways in which the intervention was implemented and allowed exploration of the contextual factors moderating the quality of intervention delivery, to inform ‘real world’ implementation of the intervention.

Staff survey data

A ward staff qualitative questionnaire was employed that was informed by the i-PARIHS framework and incorporated a range of open and closed questions asking about the staff’s experience of implementing each of the ten Safewards interventions on their ward, the enablers and barriers experienced, the support received from project workers, as well as demographic factors. The survey was completed online using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) by a ward staff member involved in Safewards prior to interviews and was used to inform the interviews (see Appendix 1).

Staff interview data

Interviews were conducted by a research assistant with the Safewards project workers and ward staff across the 20 units to explore people’s experiences and perspectives on introducing and implementing Safewards. Semi-structured interview schedules were developed in collaboration with the project team and the steering group and were informed by the i-PARIHS framework (see Appendix 2). The project workers were invited to be interviewed toward the end of their 12-month involvement in the project. On each ward, key ward staff directly involved in Safewards implementation were identified by the clinical supervisor and invited to be interviewed by one of the research assistants. Prior to conducting the interviews, the researcher read the ward survey response where available, to inform the interview and provide additional prompts to explore key issues highlighted. All interviews were conducted remotely using MS Teams.

Data analysis

Fidelity data

Wards were visited by project workers and/or the clinical supervisor. An intervention was within fidelity if it was implemented as prescribed by the Safewards website or the staff could give a rationale for an adaption that showed fidelity to the original (Safewards, Citation2023). Some interventions were in the process of being implemented during a fidelity visit but had not reached full fidelity. These were measured as half completed—for example, if staff had completed Know Each Other, but the young people had yet to be included, or where there was evidence of Clear Mutual Expectations being negotiated, but not yet finalized. As there are 10 interventions, one complete intervention showing fidelity is marked as 10% where semi-complete are marked as 5%. This data was charted against the initial benchmarking data to measure change across the duration of the project.

Conducting ward visits and fidelity checks proved difficult due to COVID-19 restrictions and difficulties in planning visits due to changes in staff and acuity of wards. In the final stages of the project two wards had to drop out due to organizational difficulties and reported no further progress and were not visited to complete a final fidelity check. However, all remaining wards had both benchmarking and final fidelity visits.

Staff and project worker interviews

Thematic analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data, following the initial phases outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) and informed by the constructs of the i-PARIHS framework (Hill et al., Citation2017). This analysis aimed to develop an understanding of staff’s experiences and views through the identification of key themes. All interviews were professionally transcribed, checked for accuracy and re-read to increase familiarity with the data. Transcripts were imported into QSR NVivo V14 (Lumivero, Citation2023) to aid analysis. Initial codes were generated that identified staff experiences and views on implementing Safewards and the impact on the CYP, staff and the ward, enactors that facilitated or challenged the implementation and sustainability of the Safewards CYP programme. These themes were discussed with other members of the evaluation team then plotted against the key constructs of the i-PARIHS framework.

Ethics

The Heath Research Authority (HRA) decision tool was completed, which determined that this was a service evaluation. Good practice ethical procedures for evaluations in health and social care were followed (NIHR, 2017/2020). All potential participants were provided with written participation information sheets about the evaluation and given an opportunity to ask questions prior to interview. A minimum 24-hour ‘cooling-off’ period was provided before informed consent was obtained and the interview took place. All data were stored securely, and confidentiality maintained. Any identifying information has been removed.

Results

The level and spread of the implementation of Safewards across the 20 CYP wards will be presented, drawing on the benchmark and fidelity data. This will then be followed by exploration of the interview data, organized under the i-PARIHS framework.

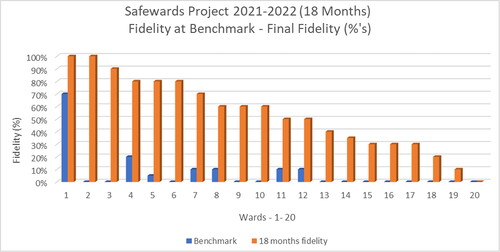

Level of implementation and fidelity

shows the progress of Safewards implementation across the 20 wards, from benchmark data at the start to fidelity data after completion of the 18 months project (final fidelity). Of the 20 wards, 12 achieved 50% fidelity or higher with two wards implementing all 10 interventions to high fidelity. Previous knowledge and implementation of Safewards proved a positive contributor to wards progressing, particularly if the ward manager and/or previous Safewards leads had been retained by the ward. However, two wards that had no previous exposure to Safewards achieved good progress, and this included the specialist unit caring for children under 13 years of age.

The biggest challenge faced by all wards was shortage or turnover of staff, particularly in key roles such as ward managers or Safewards leads. While all the wards faced such issues, those wards least affected were able to progress faster. The wards with no or little progress were those most affected by these issues.

Interview data

Invitations to be interviewed were sent to 27 ward staff who had been ward leads for the project and the 4 project workers. All 4 project workers were interviewed alongside 17 (63%) ward staff invited. Several ward staff involved in implementing Safewards had moved on to other jobs and staff on two wards where Safewards could not be delivered were unable to be interviewed. Overall, five staff did not respond to emails, two declined and three agreed but did not attend their interviews and did not respond to further emails. Staff survey data on implementation were obtained from 11 wards and informed the interviews on those wards. Data were mapped onto the i-PARIHS framework constructs to examine factors contributing to the success and challenges of the process of implementation. Within the i-PARIHS framework, characteristics of the innovation (Safewards), facilitation (by CS and project workers), engagement of recipients (staff and patients), and context for the innovation (staffing, organizational leadership) are considered (see ).

Table 3. Summary of Safewards CYP implementation mapped against the i-PARIHS framework.

The key facilitators and barriers to implementing Safewards are mapped against the four constructs within the i-PARIHS framework in .

Table 4. Summary of facilitators and barriers to implementation mapped against four constructs within the i-PARIHS framework.

Following that, a more detailed breakdown of the fifth construct of the i-PARIHS framework identifying outcomes, successes and challenges against each of the constructs is presented, drawing on the thematic analysis with illustrative anonymised quotations provided (see ).

Table 5. Successful implementation and adaptation of Safewards interventions.

Theme 1: Innovation

Successful implementation and adaptations

Participants were asked to share the interventions that were most successful to implement and whether any adaptations were required that contributed to this success. These are summarized in .

“So as you walk onto the ward, there’s this board about Safewards for young people, and it’s kind of first thing you see as you walk onto the ward. And then you kind of see … there’s a discharge message tree when you walk on. And then in the office, there’s a big display about all the different 10 interventions about Safewards, and it’s kind of spoken about every day in our safety huddle in the morning, and there’s kind of a lot of different bits of posters and things all over about it. Really amazing.” (SWC211)

Interventions likely to be used in 12 months’ time

Participants were asked to identify interventions they were most likely or unlikely to be utilizing in 12 months’ time. All but two participants articulated that they aimed to implement all 10 interventions within the next 12 months. Participants said that despite challenges, they believed all 10 interventions could be adapted to suit the needs of the wards. Two participants relayed that bad news mitigation, mutual help meetings, and mutual expectations may not be implemented in 12 months’ time due to lack of suitability to CYP wards. It should be noted that this perspective is not reflected in the actual implementation as all three interventions were implemented in the project with some adaption and other interviews reflected positive views on the suitability of the interventions (see ). There were, however recognized organizational difficulties with implementing mutual help meetings, and these are discussed below.

Challenges

Most participants said that they saw all of the 10 Safewards interventions as viable and that failure to implement was due to operational factors, such as staff turnover. Furthermore, there was a shared view across participants that all interventions could be adapted to be successful upon implementation. Some articulated that a failure to implement specific interventions could be due to a failure to thoroughly understand the associated theory, hence difficulties arising when put into practice.

“I think we’d aimed to get all of them, I don’t think there’s any that we wouldn’t be able to use, I think we just need to adapt some of them. And we’ve been given ideas of how to adapt. So, I would like to say that we’d have them all in place. (SWN408)

Discharge messages was mentioned a few times as being challenging for differing reasons. These included: (i) the ward transitioning to a new location, (ii) wards having long admissions so fewer discharges, (iii) the designated staff discharge champion leaving hence an absence of staff to keep track of implementation, (iv) CYP going on extended leave before discharge, (v) smaller units so fewer discharges.

Despite its success in most wards, the “know each other” intervention was not implemented in one ward due to high staff turnover and issues with getting staff members to complete the profiles in time.

A couple of participants relayed that some CYP did not respond well to “soft words” as they interpreted them as patronizing. Furthermore, some participants felt that “soft words” was not relevant for the age group or was too prescriptive, hence some staff deemed it “unnatural” bringing these into conversation. One participant said that success of the intervention was also dependant on the cohort of young people and their efforts to engage. However, other wards created their own soft word examples in a collaboration between young people and staff.

Implementation of mutual help meetings was difficult on some wards, as indicated above. The main reasons were said to be organizational as it proved difficult to have “another meeting” in a busy schedule alongside school lessons and therapies. Some wards saw the solution as adapting an existing meeting to incorporate the mutual help meeting agenda items.

Theme 2: Facilitation

Enablers

All participants emphasized the value of receiving training and resources from their allocated Project Worker. Participants said that the project workers supported them in finding innovative solutions to adapt interventions to best meet the needs of the ward specialty. Contact with project worker also provided a reflective space to consider the process of implementation as well as an open discussion and problem solving of difficulties. Furthermore, participants found regular check-ins from project workers provided motivation and kept Safewards at the forefront of the minds of staff amidst competing priorities.

“The project workers were fantastic. So, [name] was in regular contact, and there was a point where we had to kind of pause in our engagement just because of other priorities. Very understanding of that, looking at how we can continue to be involved, but lessening the demands, and then when we were in a position to pick it back up, absolutely, can step back up. [Name] is obviously a Safewards guru, he kind of knows everything there is to know about Safewards, so just having him as a point of contact and him sharing his knowledge, and certainly when we have met, it’s been really valuable where, when we met across services. And that’s been difficult to, I know, to organise and people to commit time to doing that. Certainly, when I've been able to attend, it’s, the value has been massive.” (SWC510)

Additional support from the Clinical Supervisor was also valued.

“We’ve had a member of the group come in called [Clinical Supervisor], who has been involved in implementing it in other services. He’s been really helpful in really explaining what it is to both the young people and staff and its purpose and what it’s there for, so having someone like that has been really helpful as well, to explain it, who’s been there, done it, and then has seen kind what the outcomes can be, it’s definitely helped.” (SWC306)

Staff also benefited from the Safewards community of practice meetings with other wards in their clusters, facilitated by the project team. Participants said that connecting and networking with other wards provided a reflective space to share common successes and barriers to implementation. Furthermore, it provided a sense of reassurance that many wards experienced similar challenges and individual wards were able to learn from each other.

“Meeting other units, I think provided some validation at times that we were doing a good job because sometimes you benchmark yourself against being perfect, where the reality is to be perfect is almost an imperfect aim.” (SWS507)

Challenges

While all respondents were happy with the support and guidance from the Project Workers and the Clinical Supervisor, support within the organization and ward was frequently affected by frequent staff turnover.

“I think we’ve had a good kind of three or four managers in post. That’s definitely affected it every time it started, it’s then kind of stopped and needed to be revamped again.” (SWC306)

“It was mainly staffing, a lack of time to look at research of different ways, places, of implementing it. And we had plans of doing multiple sessions with staff to give them a bit of training on Safewards and give them more information. And we just haven’t been able to do it, yeah. So the issue’s really been staffing, we just haven’t had the staff time to even meet up as a project team.” (SWN212).

Due to COVID-19, some participants struggled with online as opposed to in-person training and the inability of people to visit the ward.

“It would probably have been easier if we’d been able to go to other places, if like project workers had been able to come here and look around earlier and get more of a, like, in person view of things, and then the, like, lack of families being able to be on the ward to engage in things as well, I think a bit of an impact.” (SWN212)

Theme 3: Recipients

Enablers

A major enabler was recruiting a motivated cohort of ward staff to lead the ward implementation. Enthusiasm from staff members was reflected in higher fidelity of interventions as these staff were able to see the long-term benefits of interventions and enthusiastically promote them within the ward communities.

“Yeah, they, I think once you’ve got the right people on board, they feel that they’re responsible for something, which is always good, and want to spread and kind of drive it forward. The challenge, I think, they sometimes experience is around their conflict in priorities. So, wanting some protected time to commit to Safewards, but perhaps also needed to be providing direct patient care.” (SWS507)

Participants relayed that staff members recognized ‘positive words’ and ‘talk down’’ tips as inherent to good practice. The interventions allowed staff to develop and refine existing skills during implementation. Improving the handovers between staff received positive feedback as it supported staff in reflecting on and planning the day.

“I think some of the stuff, especially, sort of, around the ones that probably more directly affect us, like, the Soft Words and Talk Down stuff. People, you know, people are really skilled at those here. I think it’s helped with the Know Each Other and the Mutual Expectations, having those really visual on the ward.” (SWN214)

All participants communicated that delays in implementation resulted in an absence of or limited feedback from CYP regarding the 10 interventions. Participants who did provide feedback from CYP said that CYP found the interventions that they had direct involvement in, for example, ‘know each other’ and ‘mutual expectations’ to be the most beneficial and enjoyed these most.

No participant communicated receiving negative feedback from parents/carers. The interventions most commonly mentioned by parents/carers were visual interventions that included: (i) ‘know each other’ (ii) ‘discharge messages’ (iii) ‘calm down’ methods (self-soothe boxes). One participant said that “know each other” was a great icebreaker between parents/carers and staff members and fostered greater comfort for parents/carers as they became more familiar with the cohort of staff caring for their child.

Challenges

Some negative staff attitudes were expressed toward Safewards with staff feeling that specific interventions were already on their wards, with the occasional consequence that some staff believed their practice was being scrutinized during the implementation of Safewards. Some felt existing practices were being “rebranded”, resulting in a lack of motivation and enthusiasm during implementation. One person said that staff struggled with the administrative tasks related to the interventions and documenting evidence for its practice.

“Um, I think people always get their back up when it comes to things like Talk Down or Soft Words because, like, we do that all the time, Why do we need a thing for it? Or that’s just what we do. And I think whenever it’s something that we already do, um, they’re like we don’t need a name for it because sometimes people can be a bit annoyed about things like that, and they don’t kind of see that these things already do.” (SWC211)

There was a mixed CYP attitude toward the ‘mutual help meetings’ when they were seen as another meeting to add to busy daily schedules, whereas CYP in other wards enjoyed participating in and attending the meetings.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions on wards, all participants said that the lack of parents/carers’ physical presence on the wards had resulted in limited to no feedback on Safewards so far. Some participants rightly observed that that parents/carers could not provide feedback on interventions they would not see, such as ‘positive words’ in handover.

One of the project workers also relayed some resistance from staff as:

“In this project, wards were chosen and didn’t have a say [in participating], therefore they might have been resistant; and they were ‘struggling’ therefore challenges were already in place.” (Safewards Project Worker 1)

Theme 4: Context

Enablers

Participants said setting aside allocated time for implementation was a major contributor to success. Participants from wards that had previous knowledge of Safewards also said that the current implementation of Safewards was more successful than previous attempts, due to an increase of protected time for the implementation. The use of allocated time allowed staff to comprehend interventions in more depth, subsequently improving putting intervention theory into practice. Support for Safewards from more senior staff was also important.

“But again, very positive in relation to the clinical manager was saying she would make sure that the Safewards project is included within their adolescent governance meetings. So, it is on the agenda and sort of it is a standard agenda item and that keeps the momentum going. And again, I think those governance structures and those frameworks of meetings and protected time or motivation to keep those meetings going, does make a big difference, as it did do on the [name] unit.” (Safewards Project Worker 3).

Some significant ward changes identified by participants included greater communication between staff during handovers as well as improved relationships between staff and patients due to greater awareness of language used. Participants also articulated that the presence of Safewards helped to reinforce and develop existing practices. Additionally, a few participants recognized improvements in junior staff practice from observing more experienced senior staff modeling Safewards interventions.

Challenges

Staff shortage was the most common barrier voiced by participants. The lack of available staff left little capacity to implement all 10 interventions as ward staff were handling a range of other priorities with unmanageable workloads. Another barrier was the high acuity within the wards during the project. At times, the intense combined workload pressures led to a lack of energy amongst staff.

“I think it was just mainly lack of staff… I think staff have been quite burnout with shortages and the acuity. So, I think trying to implement something just felt a bit like just another thing to add to their workload… I think it’s difficult to implement changes, isn’t it, when staff are just completely overwhelmed with things already?” (SWS309)

Participants also reflected on the high staff turnover in wards and resulting reliance on agency/bank staff in the absence of regular, core ward staff. They felt this consequently impacted on the fidelity levels of interventions as newer staff required training and monitoring. High staff turnover in leadership positions on some wards, particularly at ward manager levels, also created delays to progress, through a lack of central and authoritative leadership of the implementation. On one ward, this was acutely felt as they had four ward managers during the 18-month project. This feedback correlated with the progress that wards made as those that achieved less final fidelity were those that were most affected by these issues.

“But since around January, [name], who I would say was the most biggest influence, the senior OT, left the service. Since then, the psychologist had left the service. The consultant psychiatrist had left the service and their ward lead team, but also their multidisciplinary team became totally dismantled. Which, given the pressures that the nursing team are already experienced in that I've described place is a lot more focused on the nursing team just from a care perspective, keeping the ward safe and providing a good standard of care.” (Safewards project Worker 3)

Most participants articulated that it was too early to determine whether Safewards had a significant impact on rates of conflict and restrictive practices, largely due to delays in implementation. Furthermore, a few participants deemed it difficult to appropriately measure and quantify whether Safewards has been effective in reducing rates due to the multi-dimensional nature of wards and additional interventions occurring simultaneously. Others relayed that it was hard to measure as conflict was dependant on the cohort of CYP and restrictive practices were not commonly used within their associated wards.

“I would like to hope so. It’s difficult to quantify, because the wards are so dynamic, we have so many things happening, so many individualised interventions alongside kind of more ward or community-based interventions. It’s hard to say confidently that, you know, these Safewards intervention or collection of interventions resorted in this output.” (SWC510)

There was a mixed response from participants regarding the impact of Safewards on the organization, staff working and atmosphere of wards. Responses that Safewards produced little to no significant changes within wards derived from two main reasons including (i) a delay in implementation hence more time is required to observe significant changes and (ii) a belief that the Safewards interventions preexisted and have already been embedded into ward culture.

“Safewards works alongside so many other areas of focus and projects that generally the teams are working on. So, if you’re looking at projects around reducing restrictive practise, Safewards just slots into that. If you’re looking at projects around improving patient engagement, Safewards fits into that. If you’re looking at how you’re developing the therapeutic milieu, Safewards just fits into that.” (SWC510)

Most participants suggested that COVID-19 did not directly affect the implementation of Safewards. Instead, COVID-19 heightened ward issues such as staffing and high staff turnover that preexisted prior to the pandemic. One participant said that the uncertainty around the pandemic ignited anxieties amongst ward staff which affected the mental capacity of staff and subsequently negatively affected implementation. Another participant communicated that COVID-19 aided the implementation of Safewards as they had more protected time to dedicate toward the interventions. However, the project workers reported that the restrictions on ward visits in the early stages of the project, affected their ability to carry out effective preparation and education about Safewards.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore whether and how Safewards can be successfully implemented on CYP wards and to identify whether the ideas and theories underpinning the Safewards model and interventions are relevant when applied to CYP and identify any revisions required.

Utilizing adult health-related research and interventions to guide practice with CYP may be problematic if differing factors influence the implementation and relevance of those approaches. Essentially, CAMHS is a specialist area deserving discrete attention (Baker et al., Citation2022). Hence, this evaluative project has allowed a deep dive into how Safewards operates within CYP services, in several specialities across areas of England.

Safewards itself is a complex programme consisting of ten interventions that, when implemented together, is designed to improve the experience of patients (in this case young people) by reducing the number of conflict and containment (restrictive practice) behaviors (Bowers, Citation2014). It helps improve therapeutic relationships between staff and patients through magnifying staff practices known to make wards calmer and safer (Ward-Stockham et al., Citation2022).

The results of this study demonstrated that there is clear evidence that Safewards is acceptable to CYP services. Whilst wards were hindered in the implementation due to the difficulties described, wards with capacity were able to understand and implement the interventions with two wards implementing all 10 interventions and 18 of the 20 wards striving to and implementing many of the interventions. All specialist CYP services (General Adolescent Units, PICUs, Secure, Eating Disorder and the service for under 13s) participated and were able to implement Safewards. The fidelity visits to wards showed that CYP wards can implement the interventions with fidelity to the original design of Safewards interventions. The ‘Know Each Other’’ and Calm Down Methods’ interventions may even fit better within the existing culture of CYP services.

While all the interventions are acceptable and achievable in CYP services, wards did make adaptations to make interventions work within the specialist nature of their service. This included simplifying language in the case of ‘Clear Mutual Expectations’, adapting the intervention to fit within the packed CYP ward schedule in the case of ‘Mutual Help Meetings’, developing specific ‘Soft Words’ in collaboration with young people, or more focus on individual resources for ‘Calm Down Methods’. Similar adaptations were reported by Yates and Lathlean (Citation2022) in their study on an acute adolescent ward. As with implementation in adult services, secure CYP services carried out risk assessments with ‘Calm Down Methods’, and wards that had long patient stays made adaptions to ‘Discharge Messages’, employing the language of ‘Recovery messages’. This has also been seen when implemented in adult services with similar lengths of stay, such as secure units (Maguire et al., Citation2023).

In terms of facilitation, wards that had previous knowledge and experience of Safewards and ward leads who were knowledgeable and committed to the project were influential in positive implementation. Support from the Project Workers in terms of assisting wards while helping keep them on track, was also beneficial. Ward staff engaged with the project team and gave what they could, dependant on their capacity considering the difficulties mentioned. Staff interviewed found the Project Workers to be proficient and useful in terms of providing education and information, developing and sharing resources to assist the implementation of individual interventions and problem solving with Safewards leads during regular check-ins. This is a useful finding given the relatively little time each project worker had for each ward. The staff also greatly valued the opportunity to network with other wards during the project.

The biggest factor to hinder implementation was the level of challenges outside of Safewards such as staff shortages, staff turnover, a lack of support from some senior staff, a perceived (and probable) increase in acuity and the lingering restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Aside from the pandemic, similar challenges have been reported in adult mental healthcare (Fletcher et al., Citation2017; Higgins et al., Citation2018; James et al., Citation2017; Price et al., Citation2016) and in acute adolescent ward introducing Safewards (Yates & Lathlean, Citation2022). A few wards were so hindered by these issues that they were able to achieve little or no progress, despite having committed staff who wanted to implement Safewards.

Many staff interviewed were confident about continuing implementation of other Safewards interventions and sustaining change. However, given the support being provided by dedicated Project Workers and the added motivation of participating in a targeted implementation project, it may be questionable whether such change can be maintained once the project ends if the staffing and related pressures continue. There are few signs currently of the staffing cavalry coming to the rescue (Gilbert & Mallorie, Citation2024).

Other studies, reviewed in a scoping review by Lawrence at al. (Citation2021), have reported other barriers to the implementation of Safewards including resistance to change, prevailing organizational priorities, staff skepticism or ambivalence, and less of a recovery-orientation or greater concern about patient acuity or risk. Whilst there was little evidence of these issues explicitly reported in our study, we welcome Kipping et al. (Citation2019) suggestion for greater co-production with staff (and patients) in implementation strategies designed to maximize uptake.

While we are confident that Safewards is acceptable to CYP services, we should be as cautious as staff participating in the project about inferring results when it comes to reducing conflict and containment. The project did look at whether this could be analyzed using organizational data, but this proved not to be possible as the wards were spread across 16 separate organizations that collated different data in varied formats. Also, considering the COVID-19 restrictions we were unable to arrange frequent researcher visits to wards and, with staff shortages, wanted to minimize demands on staff, such as collecting new data. Finally, to prove effectiveness, the wards would first have to be actively using the Safewards interventions. As can be seen by the results of implementation, this is varied across the 20 wards, which would limit analysis. Many staff interviewed felt that Safewards had a positive effect on ward culture, as reported elsewhere (Hottinen et al., Citation2020), and that they would continue with the interventions. A lengthier, more detailed and costly research project would be required to obtain quantitative data to test whether Safewards reduced conflict and containment in CYP services. We do hope, however, that this project indicates that such a research project is viable.

In interviews with staff, we heard of positive engagement and innovative contributions to various Safewards interventions by the CYP, including ‘Know Each Other’ and ‘Discharge Messages’ as reported above. The interviews are not homogeneous, however, and there are differing views about specific interventions which make us cautious about strongly recommending any intervention above another. Future studies of Safewards in CYP units should be co-produced and include tailored methods for obtaining the views and experiences of CYP and family members.

As many staff told us, CYP services are as much for families and carers as they are for the young people admitted. We saw this in the project when families and carers were involved in interventions such as leaving a ‘Discharge Message’ or when staff created the folder of ‘Thank You’ messages from family members whose young person had been discharged to further support other families and carers at the time of admission. Although by the end of the project wards felt they were “returning to normal” with the lifting of restrictions imposed during the pandemic, one area that we were told had yet to improve was family and carer visiting. There is an open question, therefore, as to what further adjustments could be made to make Safewards more inclusive for families and carers.

Limitations

Due to COVID-19 and increased pressures on wards, we aimed to undertake a light-touch evaluation that did not place undue pressure on ward staff. This meant that we were unable to collect quantitative data on levels of conflict and containment on the wards, using tailored measures (Safewards, Citation2023), on the possible impact of the new interventions or on the attitudes of staff toward attempts to reduce restrictive practices, which can be found to be defensive. Also, well-developed plans to include feedback from CYP had to be shelved as it required significant support from staff. Staff shortages/turnover also meant that some planned interviews could not happen.

Conclusions

Safewards is an acceptable and attractive intervention to staff working in CYP mental health units and can help create a more positive culture. Most of the 10 interventions are seen as suitable for CYP although some required slight adaptations for use with young people and/or certain mental health services, such as secure services or eating disorders. However, staff were keen and able to make and share those adaptations. Engaging with the project and implementation was subjected to significant difficulties created through low staffing numbers in units, constant turnover of staff and loss of key ward leaders.

The results of this evaluation would support the commissioning of a large-scale study to evaluate the implementation of Safewards and outcomes for CYP and staff in CYP units over a longer period. Such a study should ensure the involvement of CYP in the design and implementation of the study and ensure their perspectives of Safewards interventions are captured. Future studies should also include a health economic analysis to inform future commissioning decisions.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge and thank the staff and young people on wards that contributed to implementing Safewards and evaluating the project. Thanks also to members of the Project Advisory Group, including the young people with lived experience. Finally, huge thanks to the four Safewards project workers: Nick Horne (North Cluster), Marcia Tharp (South Cluster), Giselle Cope (Middle Cluster), Catherine Gilliver (Southeast Cluster).

Disclosure statement

AS and GB were involved in the development and trial of Safewards and maintain the Safewards website. GB also manages Safewards social media platforms. We have no financial interests.

Data availability statement

Data is not available for this project.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baker, J., Berzins, K., Canvin, K., Benson, I., Kellar, I., Wright, J., Lopez, R. R., Duxbury, J., Kendall, T., Stewart, D. (2021). Non-pharmacological interventions to reduce restrictive practices in adult mental health inpatient settings: the COMPARE systematic mapping review. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hsdr/hsdr09050#/abstract https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr09050

- Baker, J., Berzins, K., Canvin, K., Kendal, S., Branthonne-Foster, S., Wright, J., McDougall, T., Goldson, B., Kellar, I., & Duxbury, J. (2022). Components of interventions to reduce restrictive practices with children and young people in institutional settings: The Contrast systematic mapping review. Health and Social Care Delivery Research, 10(8), 1–180. https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3154885/1/3039569.pdf https://doi.org/10.3310/YVKT5692

- Birken, S. A., Powell, B. J., Shea, C. M., Haines, E. R., Kirk, M. A., Leeman, J., Rohweder, C., Damschroder, L., & Presseau, J. (2017). Criteria for selecting implementation science theories and frameworks: Results from an international survey. Implementation Science, 12(1), 124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0656-y

- Bowers, L. (2014). Safewards: A new model of conflict and containment on psychiatric wards. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21(6), 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12129

- Bowers, L., Alexander, J., Bilgin, H., Botha, M., Dack, C., James, K., Jarrett, M., Jeffery, D., Nijman, H., Owiti, J. A., Papadopoulos, C., Ross, J., Wright, S., & Stewart, D. (2014). Safewards: The empirical basis of the model and a critical appraisal. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21(4), 354–364. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jpm.12085 https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12085

- Bowers, L., James, K., Quirk, A., Simpson, A., Sugar, Stewart, D., & Hodsoll, J. (2015). Safewards: A cluster randomised controlled trial of a complex intervention to reduce conflict and containment rates on acute psychiatric wards. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 52, 1412–1422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.05.001

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Butterworth, H., Wood, L., & Rowe, S. (2022). Patients’ and staff members’ experiences of restrictive practices in acute mental health in-patient settings: Systematic review and thematic synthesis. BJPsych Open, 8(6), E178. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.574

- CQC. (2017). The state of care in mental health services 2014 to 2017: Findings from CQC's programme of comprehensive inspections of specialist mental health services. London, Care Quality Commission. https://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/major-report/state-care-mental-health-services-2014-2017

- Cusack, P., Cusack, F. P., McAndrew, S., McKeown, M., & Duxbury, J. (2018). An integrative review exploring the physical and psychological harm inherent in using restraint in mental health inpatient settings. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(3), 1162–1176. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12432

- Department of Health. (2014). Positive and Proactive Care: reducing the need for restrictive interventions. London, Department of Health. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/300293/JRA_DoH_Guidance_on_RP_web_accessible.pdf#:∼:text=The%20guidance%20makes%20clear%20that%20restrictive%20interventions%20may,or%20as%20part%20of%20an%20agreed%20care%20plan.

- Dickens, G. L., Tabvuma, T., & Frost, S. A. (2020). Safewards: Changes in conflict, containment, and violence prevention climate during implementation. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(6), 1230–1240. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12762

- Duxbury, J., Aiken, F., & Dale, C. (2011). Deaths in custody: The role of restraint. Journal of Learning Disabilities and Offending Behaviour, 2(4), 178–189. https://doi.org/10.1108/20420921111207873

- Finch, K., Lawrence, D., Williams, M., Thompson, A., & Hartwright, C. (2021). A systematic review of the effectiveness of Safewards: Has enthusiasm exceeded evidence? Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 43(2), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2021.1967533

- Fletcher, J., Spittal, M., Brophy, L., Tibble, H., Kinner, S., Elsom, S., & Hamilton, B. (2017). Outcomes of the Victorian Safewards trial in 13 wards: Impact on seclusion rates and fidelity measurement. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 26(5), 461–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12380

- Gilbert, H., Mallorie, S. (2024). Mental health 360: workforce. London, King’s Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/long-reads/mental-health-360-workforce

- Harvey, G., & Kitson, A. (2015). PARIHS revisited: From heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implementation Science, 11(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0398-2

- Hayes, D., Thievendran, J., & Kyriakopoulos, M. (2022). Adolescent inpatient mental health services in the UK. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 107(5), 427–430. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2020-321442

- Higgins, N., Meehan, T., Dart, N., Kilshaw, M., & Fawcett, L. (2018). Implementation of the Safewards model in public mental health facilities: A qualitative evaluation of staff perceptions. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 88, 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.08.008

- Hill, J. N., Guihan, M., Hogan, T. P., Smith, B. M., LaVela, S. L., Weaver, F. M., Anaya, H. D., & Evans, C. T. (2017). Use of the PARIHS framework for retrospective and prospective implementation evaluations. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 14(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12211

- Hottinen, A., Rytilä-Manninen, M., Laurén, J., Autio, S., Laiho, T., & Lindberg, N. (2020). Impact of the implementation of the safewards model on the social climate on adolescent psychiatric wards. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(3), 399–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12674

- INQUEST. (2017). Jury condemns police restraint of young black man in mental health hospital whilst medical staff looked on. https://www.inquest.org.uk/seni-lewis-conclusion

- James, K., Quirk, A., Patterson, S., Brennan, G., & Stewart, D. (2017). Quality of intervention delivery in a cluster randomised controlled trial: A qualitative observational study with lessons for fidelity. Trials, 18(1), 548. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2189-8

- Jones, P. B. (2013). Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. The British Journal of Psychiatry. Supplement, 54(s54), S5–S10. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119164

- Kipping, S. M., De Souza, J. L., & Marshall, L. A. (2019). Co-creation of the Safewards Model in a forensic mental health care facility. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(1), 2–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2018.1481472

- Lawrence, D., Bagshaw, R., Stubbings, D., & Watt, A. (2021). Restrictive practices in adult secure mental health services: A scoping review. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 21(1), 68–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2021.1887978

- Lumivero. (2023). NVivo (Version 14). www.lumivero.com

- Maguire, T., Harrison, M., Ryan, J., Lang, R., & McKenna, B. (2023). A Nominal Group Technique to finalise Safewards Secure model and interventions for forensic mental health services. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 00, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.13006

- Mullen, A., Browne, G., Hamilton, B., Skinner, S., & Happell, B. (2022). Safewards: An integrative review of the literature within inpatient and forensic mental health units. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 31(5), 1090–1108. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/inm.13001 https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13001

- Nawaz, R., Reen, G., Bloodworth, N., Maughan, D., & Vincent, C. (2021). Interventions to reduce self-harm on in-patient wards: Systematic review. BJPsych Open, 7(3), E80. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bjpsych-open/article/interventions-to-reduce-selfharm-on-inpatient-wards-systematic-review/45D158CCE75BD49345BD7822A4CA387B https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.41

- NHS Benchmarking. (2018). 2018 CAMHS Project – Results published. Manchester, NHS Benchmarking. https://www.nhsbenchmarking.nhs.uk/news/2018-camhs-project-results-published

- NICE. (2015). Guideline NG10: Violence and aggression: short-term management in mental health, health and community settings. London, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng10

- NIHR. (2017/2022). Best practice in the ethics and governance of service evaluation. NIHR Applied Research Collaboration West. https://arc-w.nihr.ac.uk/Wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Full-ethics-guidelines-revised-Nov-2020.pdf

- Panda, P., K., Gupta, J., Chowdhury, S. R., Kumar, R., Meena, A. K., Madaan, P., Sharawat, I. K., & Gulati, S. (2021). Psychological and behavioral impact of lockdown and quarantine measures for COVID-19 pandemic on children, adolescents and caregivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 67(1), fmaa122. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmaa122

- Price, O., Burbery, P., Leonard, S., & Doyle, M. (2016). Evaluation of Safewards in forensic mental health. Mental Health Practice, 19(8), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.7748/mhp.19.8.14.s17

- Safewards. (2023). Evaluation methods. https://www.safewards.net/managers/evaluation-methods

- Thibaut, B., Dewa, L. H., Ramtale, S. C., D'Lima, D., Adam, S., Ashrafian, H., Darzi, A., & Archer, S. (2019). Patient safety in inpatient mental health settings: A systematic review. BMJ Open, 9(12), e030230. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/9/12/e030230 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030230

- UNICEF. (1990). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. London, UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/unicef-convention-rights-child-uncrc.pdf

- Ward-Stockham, K., Kapp, S., Jarden, R., Gerdtz, M., & Daniel, C. (2022). Effect of Safewards on reducing conflict and containment and the experiences of staff and consumers: A mixed-methods systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 31(1), 199–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12950

- Yates, N. J., & Lathlean, J. (2022). Exploring factors that influence success when introducing “The Safewards Model” to an acute adolescent ward: A qualitative study of staff perceptions. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing: Official Publication of the Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nurses, Inc, 35(3), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12365

Appendix 1:

Safewards Staff Questionnaire

Implementing Safewards on Children’s and Young People’s Wards - Staff Survey

Thank you for agreeing to complete our short survey about the implementation of Safewards on your ward!

As you know, Safewards is a model that involves 10 interventions designed to reduce conflict and containment on inpatient mental health wards for working-age adults. By completing this survey, you are helping us understand how Safewards is working on your ward for children and young people. The survey should take less than 10 min to complete.

Your responses will be kept confidential and will not be shared outside the research team. To find out more about how we will use your data please refer to information sheet sent to you via email. If you have any questions about this questionnaire or the project, please contact the Project Manager Prof Alan Simpson ([email protected]) or Research Assistant Madeleine Ellis ([email protected]).

Thanks again you for your support!

About you and your ward

What is your name?

![]()

Which organization do you work for?

![]()

Which ward do you work on?

What is your role(s)

on ${q://QID3/ChoiceGroup/SelectedChoices}?

(e.g. Staff Nurse, Healthcare Assistant, Ward Manager etc.)

![]()

How long have you worked on

${q://QID3/ChoiceGroup/SelectedChoices}?

○ Less than 1 month

○ Between 1 and 5 months

○ Between 6 months and 1 year

○ More than 1 year but less than 5 years

○ 5 years or more

If you are a Safewards ward champion on

${q://QID3/ChoiceGroup/SelectedChoices}, please tell us which interventions you are champion for?(please tick all that apply)

□ N/A - I am not a Safewards champion

□ Clear Mutual Expectations

□ Soft Words

□ Talk Down

□ Positive Words

□ Bad News Mitigation

□ Know Each Other

□ Mutual Help Meeting

□ Calm Down Methods

□ Reassurance

□ Discharge Messages

About Safewards On Your Ward

To what extent has your ward implemented each of the following Safewards interventions…?

How frequently have you noticed the Safewards interventions being used on

${q://QID3/ChoiceGroup/SelectedChoices}…?

As you know, the Safewards interventions were originally developed for wards for working-age adults.

Has your ward made any changes to the interventions, to make them more suitable for your ward or the young people on your ward?

You told us that you have made changes to one or more of the Safewards interventions. Please briefly explain what changes you made to the intervention(s) and why…

![]()

Support for implementing Safewards

Overall, how would you rate the support you/your ward received from the Safewards project team/workers for implementing Safewards on

${q://QID3/ChoiceGroup/SelectedChoices}…?

Please tell us anything that could have been improved about the support you received from the Safewards project team/workers for implementing Safewards?

By telling us this you can help us to help other wards to successfully implement Safewards.

Please tell us anything that was particularly helpful about the support you received from the Safewards project team/workers for implementing Safewards?

By telling us this you can help us to help other wards to successfully implement Safewards.

To what extent (if any), do you feel that Covid-19 has impacted on your ward’s ability to implement the Safewards interventions?

Please briefly explain how Covid-19 impacted the implementation of this/these Safewards intervention(s) on ${q://QID3/ChoiceGroup/SelectedChoices}…?

Using Safewards in the future

Overall, how likely is it that your ward will be using all 10 of the Safewards interventions in 12 months time?

Which of the Safewards interventions do you think it is unlikely that you will be using in 12 months time.? (please tick all interventions that apply)

□ Clear Mutual Expectations

□ Soft Words

□ Talk Down

□ Positive Words

□ Bed News Mitigation

□ Know Each Other

□ Mutual Help Meetings

□ Calm Down Methods

□ Reassurance

□ Discharge Messages

Please briefly explain why you think it is unlikely that you will be using ${q://QID58/ChoiceGroup/SelectedChoices} in 12 months time…?

![]()

Is there anything else you would like to tell us about implementing the Safewards interventions on your ward?

Demographics

To help us understand how different peoples’ experiences of Safewards vary, please tell us a bit more about you.

If you do not feel comfortable answering a particular question, please select the ‘prefer not to say’ option.

About you…

1. How old are you?

○ 18–25

○ 26–35

○ 36–45

○ 46–55

○ 56–65

○ 66–75

○ 76 or older

2. What is your sex?

○ Male

○ Female

○ Prefer not to say

○ Prefer to self describe (please use the box below)

2. Does your gender identity differ from the sex you were assigned at birth?

○ Yes

○ No

○ Prefer not to say

3. Please describe your gender identity in the box below?

○ Please describe your gender identity here.

○ Prefer not to say

4. Please choose the option that best describes your ethnic group or background?

5. Do you have any long-term physical or mental health condition or disabilities?

○ Yes

○ No

○ Prefer not to say

6. Please tell us more about you condition or disability? (Please select all that apply)

□ I have a visual impairment (e.g. I'm blind or partially sighted)

□ I have a hearing impairment (e.g. I'm deaf or hearing impaired)

□ I have a mobility impairment (my condition affects my ability to move around)

□ I have a dexterity impairment (e.g. my condition affects my ability to lift or hold objects)

□ I have a mental health condition (e.g. depression, anxiety or bipolar disorder)

□ I have a learning disability (e.g. Downs Syndrome)

□ I am autistic or have a autism spectrum disorder

□ I have a specific learning difficulty (e.g. dyslexia, dyspraxia)

□ I have another condition or disability (please explain)

□ Prefer not to say

Interview Invite

Thank you for completing the Implementing Safewards on CYP Wards Staff Survey, we really appreciate it! As part of this study, we would like to invite you take part in an online follow-on interview with a member of the research team. This is help us understand more about staff experiences of Safewards and whether it had helped make your ward a safer place.

If you would be happy to hear more about taking part in an online interview, please fill out the details below. We will then get in touch to tell you a bit about the interview process and what taking part will involve.

Please tell us how we can contact you.:

Name: ![]()

Email address:

Telephone number 1 (mobile number):

Telephone number 2 (ward telephone number):

Any days/times that would be most convenient for us to contact you?

If you do not want to be contacted about the follow-on interview, please indicate below.

○ I do not wish to be contacted