Abstract

Semantically enriched historical newspapers offer a multitude of opportunities for data-driven exploration and analysis. In this paper we introduce the impresso interface which integrates several types of semantic enrichments and data visualization and thereby supports new exploratory workflows and the critical assessment of large-scale digitized source collections. The interface targets historians and integrates search, filtering, comparison, and recommendation based on automatically detected topics, linked named entities, text reuse, n-grams, image similarity, language, and OCR quality. We introduce the theoretical principles which guided interface development and reflect on the user requirements gathering process together with a case-study driven exemplification of novel workflows facilitated by the interface. We conclude with an overview of accompanying educational materials and discuss results from a user evaluation.

1. Introduction

In this paper we reflect on the design process and the capabilities of the impresso user interfaceFootnote1 for the exploration of semantically enriched historical newspapers.Footnote2 The interface combines data visualization with a variety of semantic enrichments and offers new workflows for search, comparison, content recommendation, term frequency and text reuse detection. It was developed with historians in mindFootnote3 who wish to explore newspaper collections from many different perspectives by seamlessly shifting between distant and close reading. impresso also serves as a capable tool for the curation of research data for further analysis outside the interface. The interface is designed to open and combine multiple entry points into historical newspaper corpora whilst keeping the learning curve as gentle as possible by providing relevant educational materials and documentation on the corpus and tools. This in awareness of the fine line between, on the one hand, oversimplification and the obfuscation of critical information concerning processing and modeling choices and, on the other, the risk of overwhelming users with overly complex interfaces.

The impresso interface was produced by the interdisciplinary research project Media Monitoring of the PastFootnote4 which compiled a corpus of Swiss and Luxembourgish newspapers and developed a technical infrastructure which facilitates data storage, semantic enrichment, and access to the data. The project identified and addressed five challengesFootnote5: First, newspapers are stored in institutional silos caused by legal restrictions and policy constraints, hampering both (free) access, discoverability, and comparability of relevant content. Second, newspaper data is available in huge volumes but also messy and often characterized by incompleteness, inconsistencies, and duplicates. This creates confusion regarding the overall availability of sources and their representativity of the historical record. Third, preceding processing and evolving technical progress produced variations in OCR and article segmentation availability and quality but also a lack of appropriate linguistic resources for historical text. This causes a hard-to-assess variability in what content can be retrieved, at least from a user perspective. All these idiosyncrasies have turned digitized newspapers into overly complex and heterogeneous data which is characterized by multiple layers of processing. Fourth, there is a lack of public-facing interfaces and knowledge to harness new opportunities for search and discovery of enriched historical sources within large and heterogeneous corpora. And finally, fifth, researchers and their peers require information regarding the above-mentioned opportunities and caveats inherent in data processing and modeling (Hoekstra and Koolen Citation2019) and interfaces which shed light on their concrete implications.

In general, historical newspapers are popular with researchers. As products of publishers and journalists, they preserve evolving norms, values, and historical knowledge horizons of those who created them following political, religious, or other editorial lines. Their value is evidenced by large-scale digitization efforts over the past decades: regional and national libraries as well as transnational bodies and commercial operators have made considerable investments in their digitization both with the ambition to make them available to larger audiences and to ensure the preservation of sometimes fragile paper originals. In 2015, a report by the International Coalition on Newspapers (ICON) estimated the number of digitized newspapers titles worldwide to be ca. 45,000 with 24,000 titles stemming from Europe and peak availability for the late nineteenth century until the end of the First World War mostly due to copyright restrictions (Center for Research Libraries Citation2015). The report indicates that outside Europe and the United States, “the number of large-scale, sustained programs of newspaper digitization is relatively small, but continues to grow with each passing year”. The relevance of commercial actors such as ProQuest and East View Information Service is highlighted, as well as efforts by the World Newspaper Archive which has succeeded in digitizing between 25 and 30% percent of US-based collections stemming from Africa and South America.Footnote6

The increasing availability of digitized historical sources and new methods for their data-driven analysis inspired a multitude of historical reflections and the identification of a “digital turn” in media history (Nicholson Citation2013). Newspapers constitute large and relatively homogenous bodies of text and therefore – in principle – lend themselves well for the application of natural language processing (NLP) techniques. Recent research demonstrates this potential for the conduct of original historical research. Computationally literate scholars such as Turunen Citation2020; Turunen Citation2021; Marjanen et al. Citation2019; Hengchen et al. Citation2021 have connected NLP methods to the history of ideas and concepts at scale. Other research projects focused on the flow of content at (trans-) national scale using text reuse detection, e.g. Oceanic Exchanges Project Team (Citation2017), Viral Texts (Citation2016), still others focused on the evolution of press coverage of migration using n-gram frequencies, topic modeling, word embeddings and classifiers (NewsEye Citation2019) or the evolution of newspaper layout, structure, and genres (Numapresse Citation2021). An early example of combining topic modeling of historical newspapers with user-facing interfaces is Robert Nelson’s Mining the Dispatch project (Nelson Citation2024). Most of these projects have developed applications which were tailored directly to the underlying research questions.

The vast majority of public facing newspaper interfaces, however, still restrict their users to basic interactions. In a review of 24 contemporary user interfaces for historical newspaper collections we found that most of them are limited to keyword search and metadata filters as the main means of interaction (Ehrmann, Bunout, and Düring Citation2017). More recent interfaces such as RetroNewsFootnote7, represent a trend toward personalization, e.g., in the form of user curated collections, frequency analyses, links to external knowledge repositories and semantic enrichments for exploration in the form of named entity recognition or topic modeling.

The goal of the impresso interface is to advance the capabilities of generic historical newspaper interfaces for researchers. Its development was driven by two high-level questions:

First, how can semantic enrichments in conjunction with visualization and design improve exploratory workflows for the study of historical newspapers and offer new perspectives on these sources? This ambition has been captured by Whitelaw Citation2015 with his demand for “generous interfaces”. Multiperspectivity, more generally, has already been identified as a key requirement for data-driven humanities on multiple occasions (Sinclair, Ruecker, and Radzikowska Citation2013; Jänicke Citation2016; Hinrichs et al., Citationn.d.; Drucker Citation2011). We follow Whitelaw’s call and use the term “generosity” to describe exploratory techniques which "open up" collections, allow users to explore multiple perspectives and help them discover relevant content they could not anticipate to find or know how to search for, in our case with the aid of semantic enrichments, data visualization and interface design.

Second, we ask: What do historians and other researchers with commonly lower degrees of digital literacyFootnote8 need to understand about digitized and enriched sources and tools for their processing and exploration? How can a public-facing interface best serve these needs? Generally, the integration of tools in (humanist) research practice raises significant epistemological and methodological challenges: Regarding digitization policies, Putnam (Citation2016) and Milligan (Citation2013) stressed the risk of an underrepresentation of non-digitized sources, but also of a de-contextualization caused by the reliance on keyword search. In other words, we need to think of available data as a “digital sample” (Beelen et al. Citation2022) in awareness of its limited representativity of past media landscapes. Hitchcock Citation2013 highlights the often-overlooked impact of poor OCR and simplistic keyword searches and demands “a much clearer understanding (…) of what precisely we think we are doing with the sources, and how they map onto what we are producing as scholars”. Scholars in information science, the digital humanities and computer science call for a more reflexive-critical engagement with digitized sources themselves, the tools for their exploration, analysis and presentation and the interfaces through which they are consulted (Abel Citation2013; Fickers Citation2020; Upchurch Citation2012). Koolen, van Gorp, and van Ossenbruggen Citation2019 stress that these tools and research data are not neutral but ought to be understood as intertwined and subject to rigorous questioning. This demand for critical reflection has recently been summarized by Hoekstra and Koolen Citation2019 who offer a theoretical framework for historical data analysis which emphasizes the need for documenting decision-making processes in the creation, transformation, and analysis of data. Oberbichler et al. Citation2021 have mapped corresponding research workflows for historians.

In summary, we identify three main requirements for interfaces to meet these objectives: 1) information on the provenance, representativity and quality of digitized sources to help assess their value for research, 2) information which enables researchers to integrate semantic enrichments in their research workflows and 3) information which documents the tools and methods used during the creation of such enrichments and their representation in the interface. We subsume these objectives under the term “transparency”.

The term “Transparent generosity” in the title of this paper points to our efforts to merge both principles, i.e., to facilitate effective exploration based on semantically enriched sources even under the imperfect conditions posed by digitized historical newspapers.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses our user requirements gathering process and introduces five focus areas for interface development, section 3 exemplifies their practical implementation in the interface based on five high-level operations and a case study. Section 4 presents results in form of insights gathered from a first user review study and analysis of usage data followed by section 5 and a discussion and outlook on future work.

2. Co-designed user requirements

In this section we reflect on our approach to translate impresso’s high-level objectives into concrete interactions with the interface. Our target audience are historians with little to no experience with NLP and data-driven research but the willingness to leave their comfort zones and to acquire new knowledge in these domains. The impresso app has three main benefits for its users: It integrates collections which are usually spread across several institutions, it offers access to semantic enrichments on a large corpus which exceeds the capacities of contemporary personal computing equipment and it offers a range of basic tools for the analysis of this data together with the option to export research datasets for further processing elsewhere.

The design of the impresso interface was in equal parts informed by the research practices of historians and inspired by novel opportunities offered by NLP, interface design and data visualization. In the beginning this constituted a void with historians not knowing what was feasible, and NLP researchers not knowing what was needed. Overcoming this void required close and continued cooperation and close exchange between representatives of these disciplines and the prospective users.

The practice to integrate experts from different disciplines throughout the design process, in decision-making and problem-solving is commonly referred to as “co-design”, “participatory design” or “co-creation”.Footnote9 Peter Galison’s analysis of trading zones in science matches our experience: the “thinness of interpretation” is preferable to the “thickness of consensus” (Galison and Galison Citation2010). In other words, there is more circulation between disciplines when exchanges are not dominated by the sharing of a single interpretation and the creation of common knowledge as a prerequisite. Rather, interdisciplinary exchanges should open the door for appropriation of the traded item from each participating partner. For example, there is little overlap between the notions of “similarity”, “event” or “topics” in history and computer science. A computed similarity measure must not match a human perception of similarity, the same goes for the output of topic modeling and themes identified by a human reader. Still, computed topics and similarity measures can be a stimulating starting point for historical source exploration and lead to meaningful insights.

Within the impresso team, historical interests gravitated toward search, discovery, comparison, and a sufficient degree of transparency. These were complemented by the research interests of the computer scientists in the project which focused on the improvement of existing tools for the processing of historical text, the generation of ground truth data and advances in multilingual text processing in general.

Between historical research practices on one side and natural language processing research interests on the other, the co-design approach opened a space for the joint development of exploratory tools for historical newspaper data: Through the lenses of their disciplinary backgrounds, team members identified challenges. These initial propositions took shape during intensive interdisciplinary discussions which considered their added value for historians, technical feasibility, and integration into the interface.

The decision which propositions to focus on was made within the impresso core team which consisted of three scholars with backgrounds in computational linguistics, two historians and three designers/developers. These decisions were guided by the transpositions of established historical research practices (e.g., searching, reading, browsing, skim-reading) and inspired by the opportunities inherent in NLP methods (e.g., n-grams, topic models to group semantically coherent texts, text reuse detection).

It is important to highlight the iterative and open nature of the underlying processes. Through experiments, disciplinary-specific methodological ideals transformed into practical and relevant features for the interface. This prompts us to speak of “co-designed user requirements”, a continuous “push-pull” interaction during which historians’ needs evolved following exposure to prototypes and enrichments.Footnote10 Such exchanges took place on multiple levels throughout the project as outlined in . On a day-to-day basis, two historians within the core team provided input for design and data modeling questions. Throughout the project, we organized ten user workshops and similar events with the goal to present opportunities from a natural language processing and design perspective and to receive feedback from historians and library professionals within and beyond the project consortium.Footnote11 Among the consortium were five historical advisors and associated researchersFootnote12 as well as invited external researchers with a looser affiliation to the project based on their interest in the corpus. This group of researchers had early and continued access to the evolving impresso app and offered feedback which helped to transform our high-level objectives into concrete user requirements for the interface. We obtained further feedback through academic teaching in graduate seminars and summer schools and regular live demos for groups and individuals. Of particular value were individual demo sessions in the presence of impresso team members to gather insights following the think-aloud principle. Feedback from users of the impresso app tends to point to minor problems with the UX design but most crucially revealed user misunderstandings, e.g., of the significance of filters (topics, named entities) and data visualizations (absolute and relative frequencies) which guided the development of the educational materials.Footnote13

Table 1. impresso’s user requirements gathering process. Overview of the involvement and contributions of stakeholders in history and libraries.

The overall success of this interdisciplinary collaboration can be attributed to a number of factors: The impresso app served as a common goal above the domain-specific research objectives. Equally important and challenging was the balance between original research in NLP and often invisible engineering tasks to process and enrich the newspaper data. Finally, experience in interdisciplinary collaboration among the consortium was a crucial prerequisite to identify opportunities provided by the data and translate them into interactions in the interface.

From a high-level perspective, our exchanges with users match the observations of van der Zwaan et al. Citation2016 who assert that (visualization) tools for humanists need to “deal with the observer dependency, heterogeneity, uncertainty and provenance of data and the complexity of humanities research questions”. Stemming from our two points of departure, the question of opportunities offered by semantic enrichments and transparency needs, codesign has revealed five focus areas: Content retrieval, high-level overviews, comparison, externalization and transparency.

The description of each focus area below includes a table with an overview of the main contributions from each discipline together with the corresponding implementations in the interface. Note that such overviews do not adequately reflect the dynamics of such interactions, their initiation, and their temporal scope. They do illustrate, however, how historians, designers and NLP experts have each made contributions to the design and functionalities of the interface from their perspectives, how these contributions evolved as part of an interdisciplinary exchange and finally manifested themselves in the interface. In section 3 we illustrate the implementation of each focus area using a case study.

2.1. Retrieve relevant content: search, filter, and discover

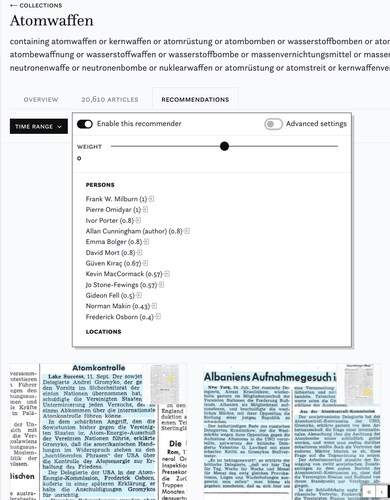

Content retrieval was a central first requirement for historians and search and filtering are obvious features for newspaper interfaces. We have advanced both functionalities through the integration of semantic enrichments such as word embeddings, linked named entities, topic modeling, ngrams, image similarity detection. Their free combination in search and filtering operations together with insights gained during the usage of other interface components constitutes the basis for iterative exploration workflows. Users also have the option to create their own filters and to store up to 10,000 articles in impresso Collections which constitute personalized research corpora and can be searched, filtered, compared, and exported. Finally, recommender systems support content retrieval beyond known-item searches based on topics, named entities and text reuse ().

Table 2. Retrieve relevant content: Search, filter, and discover.

2.2. Understand what is there: aggregate, document, and contextualize

Even though current collections of digitized newspapers only represent a fraction of all newspapers ever printed, and only a small part of all those which were preserved, they constitute a large amount of data which cannot be analyzed by close reading techniques alone. Digital collections are also inevitably imperfect and characterized by variations in data availability and data quality. Interfaces and data visualizations can all too quickly obscure these imperfections and lure scholars to draw unsubstantiated conclusions. To counter this problem, we use data visualizations of the distribution of our data and semantic enrichments in particular to reveal patterns which would remain invisible using close-reading techniques alone. Dedicated overview pages for our corpus, individual, newspapers, persons, locations, topics, and languages in the corpus display how their distributions correlate with each other. Each of these overview pages also displays the distribution of country of publication, content types, partner institutions such as libraries and access rights ().

Table 3. Understand what is there: Aggregate, document, and contextualize.

2.3. Compare and assess significance

Comparisons are a crucial technique to assess the significance of insights obtained during exploration and to iteratively test and improve queries (Düring et al. Citation2021; Huijnen Citation2019). impresso offers contrastive views through dedicated components (Inspect&Compare, n-gram explorer) ().

Table 4. Compare and assess significance.

2.4. Externalize: export, link, and embed

It is a widespread practice for historians to download individual newspaper articles and to thereby preserve them for further analysis outside the interface. impresso advances this practice and lets users export data for further processing outside the interface in accordance with copyright restrictions. To allow future referencing, users can also save queries, link to them and to embed impresso content in the public domain via a widget feature ().

Table 5. Externalize: Export, link, and embed.

2.5. Create transparency through documentation and educational materials

The sense of authority, homogeneity and comprehensiveness which radiates from data displayed in the form of lists and visualizations easily obscures variations in the nature and provenance of sources but also in the quality of their processing (OCR, article segmentation, metadata standards). This has in our experience regularly tempted well trained historians to jump to conclusions which matched their expectations. In response to our transparency objective, we have developed a variety of educational materials targeting researchers at various levels of digital literacy. These materials cover digitized newspapers as a distinct type of source, the processing undertaken during the impresso project as well as the functionalities of the interface ().

Table 6. Create transparency through documentation and educational materials.

3. The impresso interface

In this section we focus on the implementation of the components we introduced above. As a case study we will compare the press coverage of civil and military usages of nuclear power technologies in Switzerland and Luxembourg.Footnote14

3.1. Retrieve relevant content: search, filter, and discover

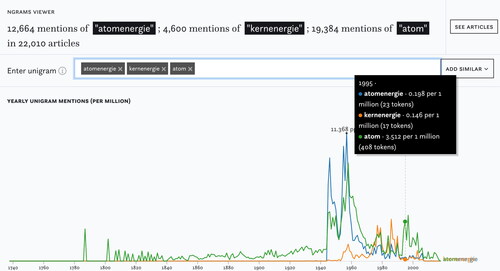

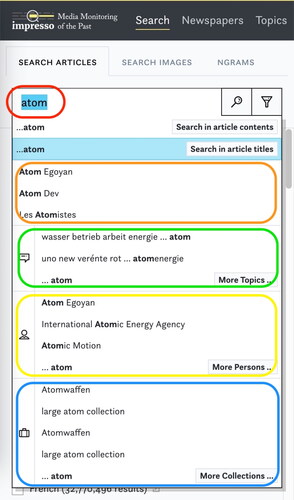

Following the order of components listed in , we begin with the introduction of the Search pill (#R1) and enter the keyword “atom” (). The Search pill opens as we type and offers information on related content in the collection to broaden the potential search space beyond keyword search. This includes the options to search in article titles only, to discover relevant named entities (e.g., “International Atomic Energy Agency”), topics mentioning the keyword (e.g., “wasser betrieb arbeit.” [water operation work]), and user-generated article collections which match the query (e.g., “Atomwaffen” [nuclear weapons]). Once a query is executed, a human readable summary (#U2) of the query is displayed on top of the result list and helps users keep an overview of their actions. Each snippet preview lists detected linked entities alongside miniatures of the page facsimile and newspaper metadata and copyright status to allow quick judgment of the relevance of search results. Analogue to common advanced search functions, the search pill can include multiple keywords to generate an OR query. Alternatively, adding another search pill constitutes an AND query. In we have searched for articles which contain the string “atom” and the linked entity “Otto Hahn”.

Figure 1. Search pill with suggestions for the keyword “atom” (blue) including entity mentions (orange), topics (green) linked named entities (yellow), user-created collections (blue).

Figure 2. A Query for “atom” and the linked entity “Otto Hahn” with suggested keywords based on word embeddings (left), the human readable summary of the executed query (centre top, highlighted) and snippet previews of search results (centre).

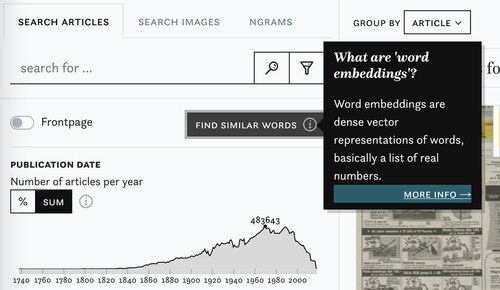

During user workshops, historians described the problem that slightly tweaked keyword searches regularly yielded vastly different results. In addition, they reported that their repertoire of suitable keywords grew whilst close reading the articles discovered during initial searches. To remedy this problem, keyword suggestions are a highly effective way to broaden the search scope, especially when dealing with imperfect OCR and historical text which is subject to semantic shifts. impresso relies on word embeddings based on our historical newspaper corpus.Footnote15 By clicking on “Add similar” in the search pill, or in “Find similar” in Search (#R1), word embeddings are retrieved for a given keyword in either French, German, or Luxembourgish (). Word embeddings support exploratory research in multiple ways and reveal:

semantically related terms, e.g., input “atom” and output “kernkraftwerk”, “wasserstoffbombe” [nuclear power plant, hydrogen bomb],

synonyms or (historical) spelling variations and semantic shifts, e.g., input “kernenergie” and output “atomenergie” [nuclear energy],

the polysemy of keywords, e.g., input “bikini” and output “atombombenversuch”, “bademode” [nuclear testing, swimwear] and

frequent OCR mistakes, e.g., “nuclöaire”, “atorniques”) which constitute an effective workaround to compensate for poor OCR quality.

For now, we cast a wide net and add all suggestions in German, French and Luxembourgish which appear relevant to the topic of nuclear power. This boosts the initial result list from 13,000 to some 154,000 articles. The Search page further offers a variety of filters based on either preexisting metadata (e.g. publication date, newspaper title, copyright status) or newly generated data such as language, content type, named entity, topic or content length (#R2-4). We will take a closer look at some of these filters further down. In a forthcoming release, impresso will allow users to filter results based on OCR quality to gain an overview of the quality distribution within a set of articles and to exclude articles with poor legibility (#T1).

One of the most frequent user requests was the ability to store a set of articles for future analysis and to limit the exploration to a relevant subset of the corpus (#R4). As we will show below, Collections can also be set as a filter to effectively focus the exploratory process on a specific set of relevant articles.

We move to the next entry point to the corpus: Image search (#R6). Images and their interplay with the text in which they are embedded constitute an important part of newspapers as a medium but are for the most part beyond the reach of researchers: they cannot be directly searched for or linked to each other. To address this challenge, impresso offers an experimental image similarity search based on novel deep learning techniques which generates visual signatures for individual images.Footnote16 There are two ways to integrate images in the exploration process: First by keyword search in image captions in conjunction with filters. Alternatively, users can select a given image in the article viewer and search for similar instances in the corpus. shows the result of a similarity ranking for an image of a nuclear power plant which was first published in 1984 by Journal de Genève and then re-used at different points in time (images blurred for copyright reasons).

Figure 3. Image similarity ranking reveals image reuse between 1984 and 1996 (images blurred for copyright reasons).

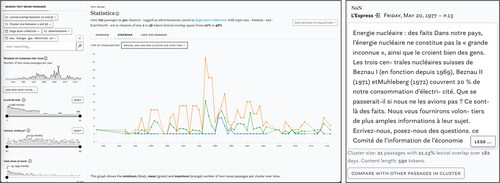

The distribution of press agency outputs and content reuse gives important insight into the functioning of past media ecosystems but is hard to trace using conventional search strategies. Text reuse detection has proven to be a highly effective solution to this problem. Using passimFootnote17, impresso NLP experts detected more than 6 million text reuse clusters in our newspaper corpus which also include recurrent content items such as weekly repeated adverts. illustrates how text reuse data in conjunction with filters for content types and topics can reveal patterns in media collections (#R7) – in this case a coordinated PR campaign in French-language newspapers to advertise the civil usage nuclear power. The corresponding passages are also highlighted in the article viewer and link back to the explorer for closer inspection. Queries for text reuse instances can be refined further, for example by lexical overlap (the similarity between two passages), the time span between two occurrences, cluster size as well as all other filters of the Search component. For an in-depth discussion of the value of text reuse data for historical research and the design of the impresso text reuse explorer see Düring et al. Citation2023.

Figure 4. Searching for instances of text reuse in the nuclear power collection revealed a pro-nuclear PR campaign published between May and November 1977 in Swiss French-language newspapers.

While search and filters are highly effective ways to separate irrelevant from relevant content, they also carry a risk: Too restrictive actions can obscure relevant content and lead to unwanted filter bubbles. To counteract this risk, impresso contains an experimental recommender system (#R8, see ). For a given collection of articles, the recommender suggests articles outside the collection based on publication date, entity or topic overlap and detected text reuse.

3.2. Understand what is there: zoom, document, and contextualize

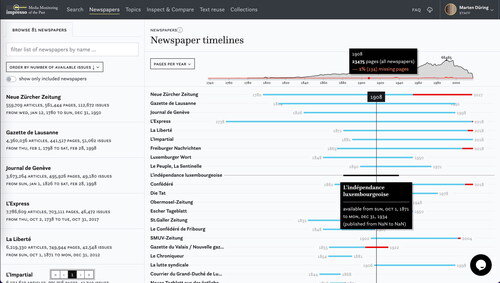

The Newspaper page (#U1) gives an overview of the distribution of available content over time, the degree of known-to-be-missing data and for each title a detailed overview of available metadata and information on the technical processing (). This reveals, e.g., the uneven distribution over time and the particularly short publication spans of newspaper titles published in the nineteenth century, which would otherwise be easily overlooked.

Figure 6. Newspaper page with information on publication periods, available issues, and indication of missing pages.

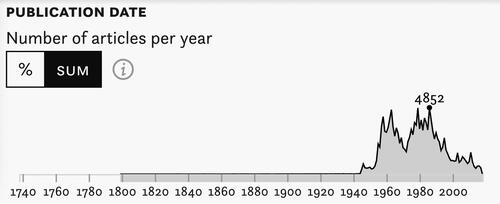

We come back to our case study. So far, our broad query for articles surrounding nuclear power has yielded ca. 154,000 articles. An inspection of the number of retrieved articles over time relative to the total number of articles in the corpus reveals four peaks (): A first in the year 1946, a second between the mid-1950s and early 1960s, a third between the mid-1970s and mid-1980s and a fourth in the year 2011. At first sight we might be tempted to link the 1946 peak to nuclear tests in the Bikini atoll, the second to the global excitement about the seamlessly endless opportunities offered by nuclear power (“energy too cheap to measure”), the third to the time when nuclear power plants were being built and opposition against them rose and the fourth to the Fukushima accident. impresso offers multiple opportunities to confirm these hypotheses using semantic enrichments.

We now return to the filters we have introduced above (#R2-4). In impresso we found topics to be particularly useful means to identify and zoom into different facets in large document collections inasmuch as they help to group semantically similar articles. For the time being we work with 100 topics per language and do not discriminate by time period to be able to compare content over time.Footnote18

We now take a closer look at and the peak in the year 1946, which, with 740 articles, is much smaller than the other ones we have observed. Once we set a date filter for 1946, the filter facets update and the list of most frequently detected person entities points to state leaders, diplomats and negotiators. The most prominent topic “regierung afp sowjetunion…” [government afp soviet union] (412 articles), which is associated with foreign policy content, points in the same direction.Footnote19 We add the topic as a second filter and now find articles which cover a scandal surrounding Soviet espionage on nuclear technology in Canada as well as articles which refer to the tensions following US nuclear testing. But once we shift our attention to other topics such as “wasser betrieb arbeit energie” [water operation work] and “wirtschaft entwicklung industrie” [economy development industry] (together 274 articles), we discover different types of articles: now we find early visions of the future impact of nuclear power on civilian life. Nobel prize winner Lawrence Bragg, for example, claimed that nuclear technology will inevitably lead to the creation of a single state within the next thousand years.Footnote20 Considering their publication one year after the detonation of the first nuclear bombs and in light of the nuclear testing at Bikini, this can be interpreted as an early indication that discourses surrounding the military and civilian usage of nuclear power evolved in separate spheres.

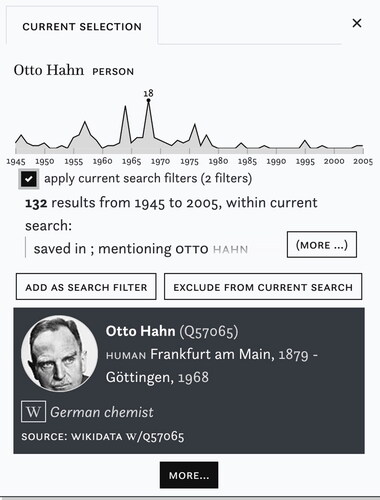

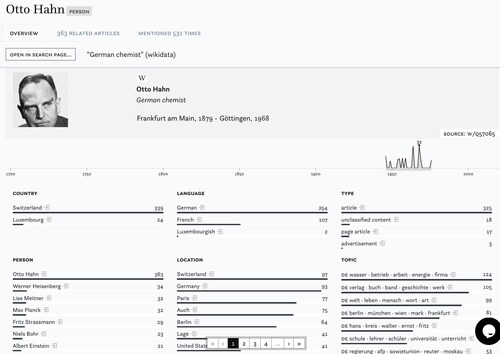

Linked named entities constitute another entry point into the result list (#R2).Footnote21 They allow us to map their occurrences across the corpus, to link information from external knowledge bases such as Wikidata, to compensate for spelling variations (“Gorbatschow”, “Gorbachev”) and to relate them to other enrichments. From the search filters we have selected German scientist Otto Hahn and inspect how often he is mentioned in our query by clicking on the icon next to his name which provides a preview of his distribution in the corpus together with basic biographical information derived from Wikidata (). With a click on “More” () we move to his entity page. Entity pages (#U4) offer additional contextual information. Here e.g., with whom he most frequently was mentioned (scientists Werner Heisenberg, Lise Meitner, and Fritz Strassmann) and which topics are linked to him: (“wasser betrieb arbeit” [water operation work] which captures science, technology, and engineering content and more surprisingly “verlag buch band” [publisher book volume] which appears to link articles focus more on Hahn as a celebrity scientist than the specifics of his research). To complement this distant reading perspective, users can further inspect snippet previews of articles which mention an entity.

Figure 9. Overview of the distribution of a linked named entity in the corpus and contexts in which it appears.

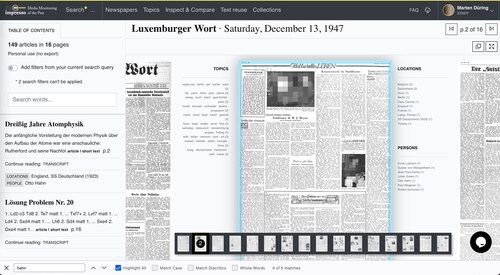

We now move to impresso’s close reading views (#U3). The article viewer displays both full page facsimile views and transcript views for more convenient reading experience (). A table of content generated from issue metadata offers a parallel entry point: It lets users browse the list of articles and perform searches within an issue. Again, in line with the principle of generosity, the article viewer displays detected semantic enrichments (e.g., named entities, topics, or text reuse passages) and related content alongside a given article and thereby opens additional entry points for further exploration and contextualization.

3.3. Compare and assess significance

Up to this point we have highlighted the diverse ways in which impresso supports the identification of relevant content. We will now focus on how impresso helps make sense of the data it outputs through comparative views (). Data analyses per se are often not sufficient to gain historical insights but become more meaningful once regarded in comparative perspective. Are, for example, our 154,000 articles related to nuclear power a lot in relation to our corpus? How are they distributed across the countries, newspapers titles, languages, over time and rubrics?

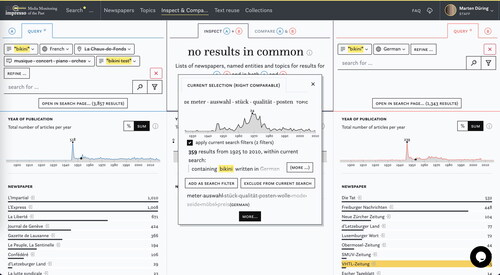

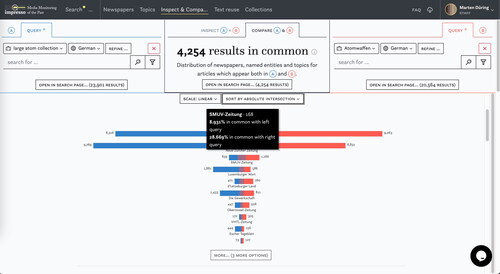

Inspect & Compare (#C1) offers a bird’s-eye-perspective on queries and search collections by displaying distributions of preexisting metadata (e.g., newspaper titles, date, and country of publication) and semantic enrichments (e.g., named entities and topics). It has been designed to observe how queries and collections relate to each other, where they overlap and differ. Two visualizations support these comparisons: Inspect reveals similarities based on small multiples of bar charts and Compare uses diverging bar charts to highlight the discrepancies and proportions between two sets. To increase legibility for highly divergent values, users can choose square root scale over the default linear scale. Bars can be sorted by largest overlap in percent or by absolute number of articles. The two views complement each other: Inspect offers overviews of the distribution of enrichments and metadata and their intersection, while Compare informs of the relative proportions of value distributions.Footnote22

For an example of such comparisons, we come back to the 1946 nuclear bomb testing at the Bikini atoll and the piece of swimwear which was named after it. In we explore the different contexts in which “Bikini” was used in German and French speaking communities. Two queries (A: French, B: German) reveal expected peaks in the year 1946. But whereas the term is increasingly frequently used in the French-speaking press after 1992, its usage seems to decline in the German-speaking press. Can this be explained with the French announcement to pause nuclear testing in 1992 (Teaiwa Citation1994) and the continuation of such tests at Mururoa atoll in 1995? Scrolling down we can inspect the topics which are prominent for the German query and the articles which are linked to them. Except for the topic “meter auswahl stück” [meter selection piece], all point to content about the nuclear tests at Bikini and their political and ecological impact. In contrast, topics in the French query point to leisure time activities, festivities, theater, and culture.Footnote23 Upon closer inspection, we learn that regional news is responsible for the pattern we observed: the opening of a club named “Bikini Test” in La-Chaud-de-Fonds, Switzerland has skewed the result list. After excluding “bikini test”, the location entity “La-Chaud-de-Fonds” and music-related topics from the results, the frequency distribution for French content follows the same pattern as the German, only the topic distribution remains different: foreign policy dominates German content, fashion-related topics the French. This is an example of how impresso allows users to investigate patterns they observe with the help of semantic enrichments. In this instance we took a closer look at what makes a keyword peak and reminded us about the idiosyncrasies of the source we are using: newspapers contain not only news or scientific articles but a lot of advertisement and other types of content and reflect events on a local, national, and international scale.

Figure 11. Using the Inspect component to contrast the distribution of “bikini” in French and German language content.

illustrates how we can use the Compare function to get a sense of how differently nuclear power was covered compared to nuclear weapons. We selected a collection which contains the results from our large nuclear power query in A and compared it to a previously created collection of articles on nuclear weapons written in German. Two Swiss newspapers stand out in terms of sheer volume of coverage: Die Tat and Freiburger Nachrichten. In we focus on the union newspaper SMUV. Upon mouseover, the black popup informs that 168 articles appear in both collections. These 168 overlapping articles constitute a mere 8.9% of the 1881 SMUV articles in the nuclear power collection on the left and 26.8% of the nuclear weapons collection on the right. In other words, the coverage of SMUV was heavily skewed toward nuclear power as opposed to nuclear weapons. A similar overrepresentation we observe for another Swiss union newspaper, VHTL Zeitung and D’Letzebuerger Land. Overall, we observe that Swiss newspapers were circa five times more likely to report on nuclear power (0.41% of the total number of articles) compared to Luxembourgish newspapers in our corpus (0.075%).

Figure 12. Using the Compare component to assess the proportion of content related to nuclear power and nuclear weapons in German-language newspapers.

Apart from such direct comparisons, Inspect & Compare can also be used to compare and thereby iteratively improve variations of a query, reveal changes over time and to assess the quality of semantic enrichments across the corpus. We have already described these usages in a dedicated paper in greater detail (Düring et al. Citation2021).

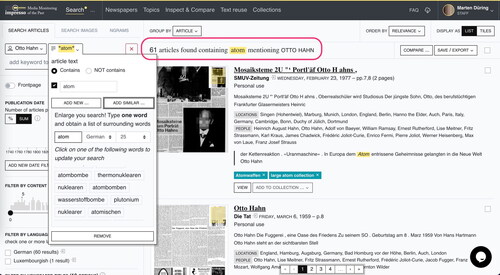

Another means for comparison are n-gram frequencies (#C2) which offer insights into the distribution of keywords within our corpus over time.Footnote24 N-grams complement article frequency charts since they reflect the total number of occurrences of a term relative to the corpus and allow easy comparisons of such frequencies. The n-gram graph represents the number of tokens per 1 million to accommodate for the variations in the size of our corpus over time. We can learn that the once common term “atomenergie” was commonly used in the 1950s but then fell out of favor and was replaced by “kernenergie” ().

3.4. Export and reference research datasets for further analysis

These and the other insights we have gained before are necessarily preliminary, they provoke new questions and further exploration within or outside the interface. Finally, search results and Collections can be exported in csv file format including selected newspaper metadata and selected semantic enrichments and full text where permitted by copyright (#E1).

impresso has the ambition to integrate different components during exploratory workflows. Two main principles enable this integration: First, queries developed in the Search component “follow” the user whenever technically possible and remain available for either further adjustments in other components or to simply gather additional perspectives, e.g., in n-grams or Inspect & Compare (see ). Second, across the interface, “Open in Search” buttons allow users to switch back to the result list for closer inspection, thereby facilitating easy shifts between close and distant reading, a key feature that helps manage the otherwise extensive list of results.

Table 7. Overview of the integration of main semantic enrichments in impresso Search page, Inspect & Compare and availability of dedicated components for exploration.

3.5. Create transparency through documentation and educational materials

We come back to the focus area transparency, here understood as the need to convey accessible information about the idiosyncrasies of historical newspapers, their processing by the impresso team, and the functioning of the interface. The educational resources we present in this segment have as their target audience again historians with little to no digital literacy. They can be considered as a first proposal to define which knowledge and skills are sufficient without any claim to perfection or comprehensiveness. Still, these resources – in our minds – offer key information to support the methodologically reflected usage of the app by explicitly pointing to the limitations of our data and by empowering users to gain insights through the different components the app provides.

We convey essential knowledge about newspaper digitization, text recognition and semantic enrichment and their implications for historical research in form of tutorials (#T2). Two lessons on the digital learning platform Ranke2 target mostly student audiences (Bunout and Düring Citation2019; Düring and Bunout Citation2021). A tutorial published on the PARTHENOS platform gives a more in-depth perspective on the challenges surrounding digitized newspapers as objects for academic research (Bunout and Düring Citation2019).

We introduce semantic enrichments and document our decisions for the processing of our data (#T3) in a series of blog posts which focus on named entity recognition, topic modeling, text reuse.Footnote25 Each individual component of the interface is further documented in form of FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions) entries, which offer additional explanation and documentation of the process of generating enrichments within the impresso project.Footnote26 They were co-written by historians, experts in natural language processing, and designers to make relevant technical knowledge understandable for non-specialists. FAQ entries are also accessible from within the interface via information buttons ().

In addition, advanced exploratory workflows are exemplified in the “impresso challenges”, learning materials with step-by-step introductions for advanced workflows which are structured thematically and grow in complexity: A first challenge introduces the functionalities, a second guides toward a critical assessment of the source material via the interface and finally, the third exemplifies the operationalization of a research question into queries to the app.Footnote27 Finally, impresso’s YouTube channel offers a variety of interface walkthroughs alongside lectures about the creation of the data and the impresso project itself.Footnote28

4. Results

As discussed in the previous sections, the impresso app offers a multitude of exploratory paths through the newspaper corpus. A precise evaluation of its added value is, however, complicated: There is no scale and no easy comparative element to measure the efficiency of exploratory activities using A/B testing and users require time to familiarize themselves with the software and data and to identify matches between its capabilities and their needs. We therefore present results from a qualitative evaluation of the app.

For the qualitative evaluation we identified a group of users with diverse backgrounds and levels of digital skills who could identify the strengths and weaknesses of the interface based on their own research interests. We selected 10 reviewers, 8 were historians who had previously worked with different interfaces for digitized historical newspapers for their research. Two reviewers were themselves involved in projects like impresso, and had a more specific interest for the development of such a tool.

To ensure sufficient time for familiarization and realistic conditions for testing, all reviewers were asked to test the app in their own time using a topic they were familiar with and to document their experiences while doing so. They were provided with a form which listed the main interface components and briefly explained their functionality together with illustrations of their intended usage, links with example queries and links to all available educational materials. For each component, reviewers were encouraged to answer questions on perceived relevance, validity of results obtained, improvements and to mention the research topic they chose to test it.

Testing took place in spring 2020 before work on the interface was completed to be able to consider any feedback. This means that the interface has undergone minor changes since the review, also in response to the critical feedback. Several components were not ready in time and require a review in the future, this includes the recommendation system, and the entity page.

Below we provide summaries of positive and negative feedback as well as suggestions received by interface components.

Search: Reviewers appreciated the value of combined filters, frequency distributions and the human readable search summary. Critiques addressed UX-related problems, e.g., the display of search results, hidden advanced features together with requests for more user-facing information on the component’s functionality (updated since) and additional filters, such as political orientation of newspaper titles.

N-grams: Reviewers appear to have been familiar with Google’s n-gram viewer and confirmed its usefulness, flagged missing integration in the overall interface and suggested a smoothing function and higher granularity in the display of dates.

Word embeddings: Some reviewers struggled to find this component in the interface, others how to make use of it. Suggestions included a translation function or an equivalent tool for named entities (added since) as well as the computation of word embeddings for subsets of the corpus as well as more advanced visualization of their distribution.

Topics: Most reviewers appear to have struggled to integrate them into their research workflows. Critiques addressed an overall opaqueness, a perceived lack of relevance but also the need for further guidance on their usage.

Newspapers: Reviewers appreciated its usefulness and requested additional metadata fields (e.g., print-run, or political orientation).

Inspect & Compare: Reviewers overall praised the component but flagged limited value due to at the time poor named entity quality and suggested additional options for comparison.

Text reuse: Reviewers praised the functionality and suggested deeper integration in Search, additional documentation, and passage-based text reuse detection.

Collections: Reviewers appreciated them as an especially useful feature despite some UX concerns regarding the editing of collections. Suggestions focused on the comparison of tweaked versions of collections (already supported by Inspect & Compare) and on more options to customize data export.

Overall, reviewers considered the interface to be well designed, to allow fluid navigation and to provide efficient support for research. One reviewer with a library background considered it as an additional step between mainstream search interfaces and APIs. Reviewers furthermore validated our high-level objective to integrate all components in the interface and flagged instances where this remains incomplete. As we expected, the reviews also revealed heterogeneous historical research needs and variations in the digital skills among the reviewers: Whereas some criticized the complexity of the interface and asked for a more “Google-like”, keyword search-focused design, others requested, for example, more fine-grained filter configurations, more technical documentation, and the integration of regular expressions in the interface. We have observed similarly mixed feedback alternating between requests for either more or less features during the evaluation of a revised version of the text reuse explorer (Düring et al. Citation2023).

The review attests almost unanimous appreciation of our implementation of Search, the Newspapers page, Collections as well as Inspect & Compare, and Text reuse and confirms that the topic modeling page does not meet our expectation to offer an additional layer for the exploration of the corpus and will be removed from the main navigation menu. Word embeddings and Ngrams remained mostly obscure to the less digitally skilled reviewers whereas those with more digital skills provided nuanced feedback with concrete suggestions for improvement.

At the time of writing, more than 1000 researchers signed a non-disclosure agreement to access the app and have the possibility to give feedback via email or a dedicated Slack group. Without registration, the app only gives access to content with a public domain license.

We plan a follow-up evaluation on a future release of the interface which will factor in the effect of having consulted the various interface-related educational materials.

5. Discussion and future work

In this paper we have presented the impresso user interface. We have shown that automatic semantic enrichment of historical newspapers in conjunction with data visualization and interface design offers novel search/discovery workflows and valuable insights for the critical exploration and assessment of large-scale corpora.

The interface lets users build queries and gather insights based on the free combination of multiple semantic enrichments such as automatically detected topics, linked named entities, text reuse, n-grams, image similarity, language, or OCR quality. Together with exploratory data visualizations, the interface encourages constant shifts between distant and close reading by combining the components we have introduced above (see ).

These new interactions are inspired by established research practices (e.g., searching, reading, collecting) and enrich them with new, data-driven perspectives on the sources (e.g., comparison, recommendations, additional search facets).

In close collaboration between historians, designers and NLP specialists and following the principles of generous and transparent interface design we bridged the gap between opportunities offered by technology and corresponding historical needs. To ensure informed usage of digitized and semantically enriched historical newspapers in general and the impresso app, we have developed educational materials for students and researchers. A first review by a group of 10 researchers has revealed overall positive and encouraging feedback and stressed the need for versatile interfaces which can accommodate a variety of research interests.

An ongoing second impresso project (2023–2027) builds on the system architecture and interface of the first project but expands its scope significantly: The project will compile and semantically enrich a corpus of Western European newspaper and radio collections and attempt their integration across modalities, languages, national borders and time on the basis of dense vector representations. Alongside a revised version of the impresso app, the new project will allow researchers to access its enriched metadata via a dedicated API in line with copyright restrictions. A forthcoming impresso data lab will allow users to generate their own analyses, e.g. of spatial relations, using interactive notebooks. In this context the team actively explores opportunities for the integration of large language models (LLMs) for both the enrichment and the analysis of the data.

The user evaluation, individual feedback, user workshops and academic teaching consistently indicate that the opportunities offered by semantic enrichment in conjunction with interface design and data visualizations are very much appreciated by our target audience. At the same time, an understanding of their advantages and relevance for the research process requires active learning. In this sense, we do not strive to reflect the existing needs of our target audience, but to explore opportunities beyond current research practices in history. Against this background, we expect the impresso interface to develop new research workflows and hope to serve as a source of inspiration for future interfaces for historical newspaper collections.

Against this background we consider interfaces like the impresso app to remain significant parallel to the rise of interactive notebooks as an increasingly popular means to conduct and document data-driven research. For less digitally literate scholars such interfaces constitute a relatively easy entry point, for those who are comfortable working with data, they serve as a convenient means to explore the available data and to compile research datasets.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the rest of the impresso team, in particular Thijs van Beek, Simon Clematide, Maud Ehrmann, Roman Kalyakin, Matteo Romanello, Paul Schroeder, Philip Ströbel as well as supervisors Andreas Fickers, Frédéric Kaplan, Martin Volk and Lars Wieneke and all associated partners for their contributions to the design and creation of the impresso app.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 https://v1.impresso-project.ch/. This article refers to work done by the first impresso project (2017-2020). Furthermore, we would like to express our gratitude towards two anonymous reviewers and Pim Huijnen for their thoughtful and constructive feedback and suggestions during the review process.

2 The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

3 For a detailed analysis of researcher personas, we refer to Bunout Citation2022.

4 impresso. Media Monitoring of the Past. Supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation under grant CR- SII5_173719, 2019. https://impresso-project.ch.

5 The project itself and an in-depth discussion of these challenges will be discussed in a forthcoming publication.

6 At the time of writing, there is no updated version of the report which forces us to rely on the status quo of 2015.

7 The interface was first published in 2016, https://www.retronews.fr/.

8 Our understanding of digital literacy follows that of the American Library Association who define it as “the ability to use information and communication technologies to find, evaluate, create, and communicate information, requiring both cognitive and technical skills”. In the context of impresso, this implies that scholars need to be able to critically reflect on newspapers as sources, the process of digitisation and enrichment as well as the representation of this data in user interfaces.

9 For an overview see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Participatory_design.

10 A more detailed analysis of the dynamics of the co-design process across all stakeholders is beyond the scope of this paper and will be developed in a future publication.

11 An overview of all workshops can be found here: https://impresso-project.ch/activities/timeline/.

12 An overview of the consortium can be found here: https://impresso-project.ch/consortium/contributors/.

13 A more detailed discussion of the process of user requirements gathering would be beyond the scope of this paper but will be addressed in a separate, forthcoming publication by the authors.

14 Other examples are available in the impresso challenges, part of the educational materials which accompany the interface: https://impresso-project.ch/assets/impresso-challenges-1.2.3.pdf

15 Word embeddings were generated using a workflow consisting of tokenisation, sentence segmentation and an alignment with SOLR tokens. Calculations were done using fastText using word-n-gram features to accommodate for the specificities of morphologically rich languages and error-prone texts. See also: https://impresso-project.ch/app/faq#how-are-word-embeddings-generated.

16 For more information see: https://impresso-project.ch/app/faq#how-search-images-work-with-search-filters.

18 For more information on topic modelling in impresso: https://impresso-project.ch/news/2018/09/07/tradingzone-tm.html.

19 It is in the probabilistic nature of topic models that they serve such exploratory purposes well and point researchers in new directions. They cannot, however, offer precise categorisation or produce exact measures. Consequently, the number of articles linked to the two topics we describe above must be seen as rough approximations of the proportions.

22 For a more detailed description of the component, see: Düring et al. Citation2021.

23 This distribution is also observable in the word embeddings: German embeddings show a mixture of terms linked to leisure time and nuclear warfare whereas French embeddings only cover the former.

24 For more information see: https://impresso-project.ch/app/faq?p=69891.

25 An overview of all materials can be found here: https://impresso-project.ch/theapp/usage/.

References

- Abel, Richard. 2013. The pleasures and perils of big data in digitized newspapers. Film History 25 (1-2): 1–10. doi: 10.2979/filmhistory.25.1-2.1.

- Beelen, K., J. Lawrence, D. C. S. Wilson, and D. Beavan. 2022. Bias and representativeness in digitized newspaper collections: introducing the environmental scan. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 38 July, (1):1–22. doi: 10.1093/llc/fqac037.

- Bunout, E. 2022. Contextualising queries: guidance for research using current collections of digitised newspapers. In Digitised Newspapers – a New Eldorado for Historians? Tools, Methodology, Epistemology, and the Changing Practices of Writing History in the Context of Historical Newspapers Mass Digitization, ed. Estelle Bunout, Maud Ehrmann, and Frédéric Clavert. Studies in Digital History and Hermeneutics. Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter.

- Bunout, E., and M. Düring. 2019. Collections of Digitised Newspapers as Historical Sources – Parthenos Training. https://training.parthenos-project.eu/sample-page/digital-humanities-research-questions-and-methods/collections-of-digital-newspapers-as-historical-sources/.

- Bunout, E., and M. Düring. 2019. The digitisation of newspapers: how to turn a page. In From the Archival to the Digital Turn Ranke.2. https://ranke2.uni.lu/u/archival-digital-turn/.

- Center for Research Libraries. 2015. The State of the Art. A Comparative Analysis of Newspaper Digitization to Date. http://www.crl.edu/sites/default/files/d6/attachments/events/ICON_Report-State_of_Digitization_final.pdf.

- Drucker, J. 2011. Humanities approaches to graphical display. Digital Humanities Quarterly 005 (1).

- Düring, M., and E. Bunout. 2021. From the shelf to the web, exploring historical newspapers in the digital age. Ranke2. Source Criticism in the Digital Age. https://ranke2.uni.lu/u/exploring-historical-newspapers/.

- Düring, M., R. Kalyakin, E. Bunout, and D. Guido. 2021. Impresso Inspect and Compare. Visual comparison of semantically enriched historical newspaper articles. Information 12 (9):348. doi: 10.3390/info12090348.

- Düring, M., M. Romanello, M. Ehrmann, K. Beelen, D. Guido, B. Deseure, E. Bunout, J. Keck, and P. Apostolopoulos. 2023. Impresso text reuse at scale. An interface for the exploration of text reuse data in semantically enriched historical newspapers. Frontiers in Big Data 6:1249469. doi: 10.3389/fdata.2023.1249469.

- Ehrmann, M., E. Bunout, and M. Düring. 2017. Historical newspaper user interfaces: A review. In IFLA WLIC 2019. Athens, Greece. http://library.ifla.org/2578/.

- Fickers, A. 2020. Update für die Hermeneutik. Geschichtswissenschaft auf dem Weg zur digitalen Forensik? Zeithistorische Forschungen 17 (1):157–68.

- Galison, P. 2010. Trading with the Enemy. In Trading Zones and Interactional Expertise: Creating New Kinds of Collaboration, ed. Matthew Mehalik, Braden R. Allenby, and Erik Fisher, 25–52. Cambridge: MIT Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unilu-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3339175.

- Hengchen, S., R. Ros, J. Marjanen, and M. Tolonen. 2021. A data-driven approach to studying changing vocabularies in historical newspaper collections. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 36 (Supplement_2):ii109–ii126. doi: 10.1093/llc/fqab032.

- Hinrichs, U., M. El-Assady, A. J. Bradley, S. Forlini, and C. Collins. 2017. Risk the drift! Stretching disciplinary boundaries through critical collaborations between the humanities and visualization.

- Hitchcock, T. 2013. Confronting the digital: Or how academic history writing lost the plot. Cultural and Social History 10 (1):9–23. doi: 10.2752/147800413X13515292098070.

- Hoekstra, R., and M. Koolen. 2019. Data scopes for digital history research. Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 52 (2):79–94. doi: 10.1080/01615440.2018.1484676.

- Huijnen, P. 2019. Digital history and the study of modernity. International Journal for History, Culture and Modernity 7 (1):991–1007. doi: 10.18352/hcm.591.

- Jänicke, S. 2016. Valuable research for visualization and digital humanities: A balancing act. In Workshop on Visualization for the Digital Humanities. Baltimore: IEEE. https://imada.sdu.dk/∼stjaenicke/data/papers/balancing.pdf.

- Koolen, M., J. van Gorp, and J. van Ossenbruggen. 2019. Toward a model for digital tool criticism: reflection as integrative practice. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 34 (2):368–85. doi: 10.1093/llc/fqy048.

- Marjanen, J., L. Pivovarova, E. Zosa, and J. Kurunmäki. 2019. Clustering ideological terms in historical newspaper data with diachronic word embeddings: histoinformatics2019 - the 5th international workshop on computational History. In HistoInformatics 2019 : International Workshop on Computational History 2019, CEUR Workshop Proceedings, ed. Melvin Wevers, Mohammed Hasanuzzaman, Gaël Dias, Marten Düring, and Adam Jatowt, 21–9. Aachen: Rheinisch-Westfaelische Technische Hochschule Aachen.

- Milligan, I. 2013. Illusionary order: Online databases, optical character recognition, and Canadian history, 1997–2010. Canadian Historical Review 94 (4):540–69. doi: 10.3138/chr.694.

- Nelson, R. K. 2024. Mining the Dispatch. Mining the Dispatch. https://dsl.richmond.edu/dispatch/.

- NewsEye. 2019. https://www.newseye.eu/.

- Nicholson, B. 2013. The digital turn. Media History 19 (1):59–73. doi: 10.1080/13688804.2012.752963.

- Numapresse. 2021. Numapresse. http://www.numapresse.org/.

- Oberbichler, S., E. Boroş, A. Doucet, J. Marjanen, E. Pfanzelter, J. Rautiainen, H. Toivonen, and M. Tolonen. 2021. Integrated interdisciplinary workflows for research on historical newspapers: perspectives from humanities scholars, computer scientists, and librarians. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 73 (2):225–39. doi: 10.1002/asi.24565.

- Oceanic Exchanges Project Team. 2017. Oceanic exchanges: Tracing global information networks in historical newspaper repositories, 1840-1914. Web Page. doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/WA94S.

- Putnam, L. 2016. The Transnational and the Text-Searchable: Digitized Sources and the Shadows They Cast. The American Historical Review 121 (2):377–402. doi: 10.1093/ahr/121.2.377.

- Sinclair, S., S. Ruecker, and M. Radzikowska. 2013. Information visualization for humanities scholars. Literary Studies in the Digital Age-An Evolving Anthology. https://dlsanthology.mla.hcommons.org/information-visualization-for-humanities-scholars/.

- Teaiwa, T. K. 1994. Bikinis and Other s/Pacific n/Oceans. The Contemporary Pacific 6 (1):87–109.

- Turunen, R. 2020. Macroscoping the sun of socialism: Distant readings of temporality in finnish labour newspapers, 1895–1917. In Digital Histories, ed. Mats Fridlund, Mila Oiva, and Petri Paju, 303–24. Emergent Approaches within the New Digital History. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1c9hpt8.22.

- Turunen, R. 2021. Shades of Red. Työväen historian ja perinteen tutkimuksen seura. https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/336197.

- Upchurch, C. 2012. Full-text databases and historical research: Cautionary results from a ten-year study. Journal of Social History 46 (1):89–105. doi: 10.1093/jsh/shs035.

- van der Zwaan, J. M., M. van Meersbergen, A. Fokkens, S. ter Braake, I. Leemans, E. Kuijpers, P. Vossen, and I. Maks. 2016. Storyteller: Visualizing perspectives in digital humanities projects. In Computational history and data-driven humanities, ed. Bojan Bozic, Gavin Mendel-Gleason, Christophe Debruyne, and Declan O’Sullivan, 78–90. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-46224-0_8.

- Viral Texts. 2016. Mapping Networks of Reprinting in 19th-Century Newspapers and Magazines. http://viraltexts.org/

- Whitelaw, M. 2015. Generous interfaces for digital cultural collections. Digital Humanities Quarterly 9 (1) http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/9/1/000205/000205.html.