ABSTRACT

This study investigates the practice of “sounding for others,” wherein one person vocalizes to enact someone else’s putatively ongoing bodily sensation. We argue that it constitutes a collaborative way of performing sensorial experiences. Examples include producing cries with others’ strain or pain and parents sounding an mmm of gustatory pleasure on their infant’s behalf. Vocal sounds, their loudness, and duration are specifically deployed for instructing bodily experiences during novices’ real-time performance of various activities, such as tasting food for the first time or straining during a Pilates exercise. Vocalizations that are indexically tied to the body provide immediate displays of understanding and empathy that may be explicated further through lexicon. The existence of this practice challenges the conceptualization of communication as a transfer of information from an individual agent – even regarding assumedly individual body sensations – instead providing evidence of the joint nature of action and supporting dialogic theories of communication, including when language-marginal vocalizations are used.

Evidence of communication being essentially dialogic is continuously emerging not only in interaction studies (Goodwin, Citation2018; Mondada, Citation2019a) and linguistic anthropology (Nakassis, Citation2018), but also in linguistic theory (Du Bois, Citation2014; Linell, Citation2009) and cognitive science (Di Paolo et al., Citation2018; Varela et al., Citation1993). This paper sets out to explore a communicative practice – sounding for others – that demonstrates how parties in social interaction rely on an assumption of mutual access and coordination, and how vocal resources and bodily events are not individual, but available to be used in a distributed and dialogic manner. The practice involves humans vocalizing with other participants who are evidently engaging in various kinds of sensing, including proprioception. The sounders use vocal resources to enact, instruct, empathize with,Footnote1 and performatively co-experience the events occurring that involve another’s embodiment. By deploying the rigorously empirical interaction analytic method of studying participants’ manifest behavior as captured on video (Goodwin, Citation1993; Mondada, Citation2014b), we will show that: (a) this is a practice used in a variety of activities and languages, (b) it showcases the communicative power of voice to build bridges to others’ bodies, thus joint sensing and action, and (c) through temporal coproduction, sound choice, and prosodic variation, it achieves social adhesion, intersubjectivity, and empathy. In short, the practice of sounding for others’ sensations demonstrates the dialogic and collaborative nature of vocal-bodily action as distributed across individuals. Our aim is to document the general features, as well as existence, of this hitherto undescribed practice that is specialized for solving the challenges inherent in having individual bodies while engaging with others.

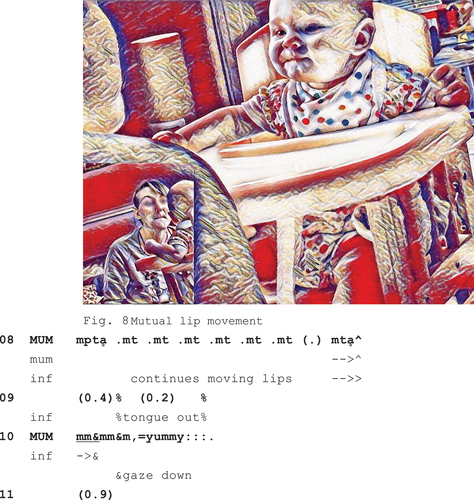

Consider the following instance () from a primary care visit, where a doctor collaboratively vocalizes the pain of the patient (Weatherall et al., Citation2021). The patient (PAT) has a sore arm and the general practitioner (GP) is palpating the patient’s elbow. His turn in lines 01–02 assumes a no-pain response, however, the patient displays pain, through a recoil in line 02, a sharp inbreath in line 03, and the formulation “that is very painful” in lines 03–05.

Transcription conventions according to Mondada (Citation2019b).

Extract 1. Tennis Elbow; TS-GP03-17 (analyzed in detail as )

Immediately latched to the patient’s inbreath, the doctor produces a sound that qualifies as a pain cry, uuuw (line 04). The sound is temporally tied to the patient’s recoil and inbreath – features that amount to a typical beginning of a pain display, fitted to what a pain expression by the patient at this very moment might sound like, and uttered very high in the pitch range of the doctor, thus further underlining the extremeness of the putative experience of the other.

It is these kinds of moments, which involve a sensational experience of one person that is vocally communicated by another, that are explored as the sounding for others practice in the current study. Specifically, we focus on sounds that are not immediately connectable to lexical content or are marginally lexicalized (i.e., non-lexical vocalizations, Keevallik & Ogden, Citation2020), which are arguably more intimately tied to the body than regular lexicon and that are here used in relation to someone else’s sensorial event. These sounds are systematically positioned at the earliest possible moment after the occurrence of initial features of a display of sensation on the other’s body (as above) or alongside putative sensations, emerging as temporally coproduced with another’s bodily events. We will present examples of different occasions in which sounding for others is used, and discuss how the practice demonstrates the thoroughly distributed, nonindividual organization of vocal production as well as the achievement of sensoriality across bodies.

Background

A relevant starting point for the sounding for others practice would be the dialogic theories of language. These theories stipulate that linguistic systematicity emerges out of interaction with others (Du Bois, Citation2014; Linell, Citation2009) and that vocal practices are but one aspect of communication that is better accounted for in relation to their embeddedness in multimodal coordinated action (Goodwin, Citation2018). The dialogic perspective has been most strongly developed in interactional studies (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, Citation2017; Ochs et al., Citation1996) that have argued for language’s role as a medium for collaborative action. In this paper, we will look at one way of using vocal resources to establish intersubjectivity in real-time copresent interaction.

Sounding for others has, to date, been investigated as a matter of speaking on behalf of someone else: reported speech (e.g., Holt & Clift, Citation2007) whereby a stretch of talk is presented as if originating from another person or oneself on a different occasion, and lexical formulations of others’ experiences, such as in in psychotherapy, customer service, and veterinary clinics (e.g., Gibson & Vom Lehn, Citation2020; Ironside, Citation2018; Jenkins, Citation2015; MacMartin et al., Citation2014; Peräkylä & Silverman, Citation1991; Throop, Citation2010: Citation2010; Weatherall & Keevallik, Citation2016). This reporting of others’ talk (or footing change, Goffman, Citation1981) or formulation of their experiences concerns the representation of someone else’s potential or prior events through verbal (and prosodic) expression, sometimes immediately after their turn at talk, sometimes when the represented speaker is not even present, but always constituting sequential action. Depictions (Clark, Citation2016), reenactments (Sidnell, Citation2006), or animations (Cantarutti, Citation2020), terms for presenting an event as if it is happening in the current moment, have furthermore focused on representing other people holistically (i.e. when vocally depicting a musical performance, the body is also done by the depicter), rather than distributing different modalities among copresent participants, which will be shown here. It has hardly been examined how bodily sensations may be communicated by other participants who are not undergoing the sensation. Past research has looked at gestural mimicking of what the others may just have gone through (Bavelas et al., Citation1986) while the current study targets sounding.

Sounding practices

Due to a broader emphasis on verbal resources across linguistic and interactional research, very little is known about how non-lexical vocalizations are used to portray experiences, let alone those beyond the self (Wiggins & Keevallik, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). A recent surge of interest in so-called “marginally linguistic” tokens (Dingemanse, Citation2020), such as onomatopoeia, ideophones, and non-lexical vocalizations has demonstrated that these sounds, though phonetically diverse, have systematic uses in interaction (Keevallik & Ogden, Citation2020). Some of these tokens are particularly useful for displays of bodily events within specific contexts, such as expressing pain at doctor’s appointments (La & Weatherall, Citation2020), exhaustion during running (Pehkonen, Citation2020), and emotional reactions during board games (Hofstetter, Citation2020), or instructing movement in dance classes (Keevallik, Citation2021). They are particularly suited for framing responses to events as spontaneous and genuine (Wiggins, Citation2002, Citation2013) or potentially accountable or delicate (Hofstetter, Citation2020; Ogden, Citation2020). Much of this work is a continuation of the argument by Goffman (Citation1978, p. 800) that these are presented as if they were “natural overflowings” of the body. Unsurprisingly, then, these kinds of marginal tokens are extensively used in the sounding for others practice, which involves the delicate accountability of representing another person as well as vocalizing a bodily event. By analyzing how participants attribute experiential phenomena to each other, and how coparticipants involve themselves in putatively inaccessible events in others’ bodies, we can examine how the body and language are intertwined, and how sensorial experiences emerge through joint participation in interaction.

Temporality of interaction

Temporality is a foundational feature of interaction (Deppermann & Günthner, Citation2015). Overwhelmingly, interaction research has focused on the order of talk and the one-at-a-time organization of verbal interaction (Sacks et al., Citation1974; Sidnell & Stivers, Citation2013). While it was one of the earliest findings that affiliative conversational moves are performed early or in overlap with current talk (Jefferson, Citation1986; Pomerantz, Citation1984), the interest in choral speech (Lerner, Citation2002), nodding during other’s storytelling (Stivers, Citation2008), early onset (Goodwin, Citation1986; Vatanen, Citation2018) and other overlap issues have appeared sporadically and have only recently been theorized into a coherent account of “early responses” that feature specific social meaning (Deppermann et al., Citation2021). In instructional settings, for example, repetitive imperatives have been shown to occur in parallel with or even after student actions (Mondada, Citation2017; Okada, Citation2018), and thereby affirm the student’s action, thus synchronizing instruction and compliance. This study will provide further illustration of how participants coproduce sensoriality in a near-synchronous manner.

Joint action and entitlement

Temporally tight collaboration acutely raises issues of agency: who is (accountably) a speaker and contributor to a turn or utterance. Interaction analytic work provides evidence that grammatical resources may be distributed across copresent individuals, such as in coconstruction of linguistic units (Lerner, Citation1996, Citation2002). The notion of “speaker” as relying on a single physical body was prominently problematized by Goffman (Citation1981). These analyses demonstrate that utterances are not only metaphorically constructed by multiple participants, via being embedded in long-term relations and histories (as argued in theories of polyphony, Bakhtin, Citation1981), but moreover that utterances are formed of components contributed by multiple participants in situ, forming coherent actions jointly.

Past studies in interaction have shown that speaking on others’ behalf can enact empathy but simultaneously risks inhibition of agency (Goodwin, Citation2004; Norén et al., Citation2013; Robillard, Citation1996; Throop, Citation2010). Participants in interaction must manage the accountability of how they enact and distribute agency – both their own and that of others – as the interaction unfolds (Enfield, Citation2017). Studies of different activities and interactional settings show substantial variability in speakers’ rights to be the sole expressors of their thoughts, emotions, and bodily experiences (Cekaite, Citation2016, p. 20; Heritage & Raymond, Citation2005; Jenkins, Citation2015; Stevanovic & Peräkylä, Citation2012; Wiggins, Citation2013). At the same time, speaking on others’ behalf occurs frequently in instructional settings. Earlier research has established how, during instruction, grammatical structures emerge in the form of incrementally produced clauses (Lindström et al., Citation2020) or locally established formulas to accompany repetitive moves (Keevallik, Citation2020a). One can also instruct someone else to play an instrument by “singing” the sounds in nonsense syllables (Clark, Citation2016; Haviland, Citation2007; Tolins, Citation2013; Weeks, Citation1996, Citation2002), but in that case it is the sound itself that is the objective of the activity rather than it being in the service of bodily concerns (concerning the paradigmatic difference of sounding for bodies vs. sounding for music, see Keevallik, Citation2021). In this paper, we show a number of ways to vocally represent the current experience of others’ bodies, both for instructing and empathizing purposes, in particular indexing it through sounds that ostensibly emanate from a particular bodily event, thereby jointly performing the experience through distributed vocal and bodily resources.

Sensing in interaction

The jointness of bodily experience that sounding for others both indexes and achieves can be seen as an instantiation of intercorporeality, wherein bodies are taken to be constituted by their relations with other bodies and socialities, and thus not separate (Merleau-Ponty, Citation1964b, p. 168). Particularly relevant to this study is Merleau-Ponty’s idea of “compresence,” which refers to the way participants embody each other, and can use their own bodily experiences as a guide to ongoing experiences in others’ bodies. Sounding for others would seem to rely on such an ability, however, as we show below, compresence is not only a precondition, but is also achieved through this practice. Within studies of interaction, the use of these concepts has only recently begun to be developed (see Meyer et al., Citation2017). However, the interactional organization of sensation more broadly, not just through the perspective of intercorporeality, has been observed since the 1980s; pain is displayed in an institutionally relevant manner at specific moments in doctor–patient interaction (Heath, Citation1989), seeing relevant details can be accomplished through professional training (Goodwin, Citation1994; Mondada, Citation2004; Nishizaka, Citation2017), tasting and smelling are collaborative actions (Mondada, Citation2018, Citation2020). While we have also found similar examples of senses being expressed with fully lexicalized items, the current study is delimited to non-lexical, or marginally linguistic, vocalizations.

Considering the variable entitlements involved in different embodied activities, we illustrate the locally contingent details of the practice in professional, everyday, as well as pedagogical environments, and then discuss the features of the practice as a whole, dissecting its theoretical consequences for the conceptualization of joint sensing, coproduction of action, and dialogicity.

The method and data

The study uses multimodal interaction analysis for documenting systematicity and accountability in participants’ behaviors, based on video-recordings of interactional events, which enables scrutiny of the mutual coordination of otherwise fleeting, real-time practices (Broth & Keevallik, Citation2020; Goodwin, Citation2018; Mondada, Citation2019a). Crucially, the analysis involves the observation of participants’ displayed sense-making of each other’s behavior, which reveals the participant’s role in organizing ongoing events, while avoiding the memory bias inherent when people are asked to account for their vocalizations in interviews as well as the ecological unnaturalness of experimentation with sounds performed by actors (Anikin & Lima, Citation2018). In order to document the practice, the data for this study come from a variety of activities: doctor–patient interaction, infant feeding, Pilates classes and dance lessons. The sensory phenomena found in these sources include pain, taste, and proprioception. We remain agnostic regarding which other senses or activities can be involved in the practice, as this is ultimately an empirical question of working through a broad variety of data. Our collection of instances is built opportunistically, through several years of data analysis within different projects.

Sounding the other’s pain was detected in medical contexts. The doctor–patient interactions were drawn from The Applied Research on Communication in Health (ARCH) Corpus of Health Interactions held at Wellington School of Medicine, Otago University, New Zealand. It currently consists of English language data from nine separate studies with a total of 478 audio-video recorded health interactions involving 533 participants, all of whom provided their consent for their data to be used for future research. In this corpus, 30 sequences were identified in which patients sounded their pain rather than merely describing it (from six different visits, see, Weatherall et al., Citation2021) and, surprisingly, in two of the visits the doctor also did so.

Numerous instances of sounding for another person’s proprioception were found in instructive settings, where the focus was on transferring bodily skills. The dance class data come from 38 h of video recorded group classes in Estonia and Sweden. Three of the 17 teachers speak Estonian (9 h), six Swedish (13 h), and 10 English (15 h). All the teachers signed their consent for research purposes; the students were informed orally about the study and of their right to opt out at the beginning of every class. In these data 20 strain sounds were identified. The Pilates data come from video-recordings of four classes given by one instructor in Estonian (total duration 4 h), where strained voice occurs at least five times per class (see an example in Hofstetter & Keevallik, Citation2023, pp. 65–67). All the participants agreed to the use of the recordings for research purposes and the teacher agreed to be non-anonymized in publications.

Sounding someone else’s taste experience has to date only been found with infants and their caregivers. The infant mealtimes data comprise 66 video-recorded mealtimes recorded in Scotland (around 19 h of data). The parents, who were all white and spoke English as their first language, were given two cameras to record the meals with their 5-to-8-month old infants, and consented for the data to be used. The study was granted ethical approval by the University of Strathclyde. All families gave consent for disguised images to be used in research publications. 66 meals in five families resulted in 273 instances of gustatory mmms (Wiggins, Citation2019) and 391 lip-smack chains (Wiggins & Keevallik, Citation2021b).

Sounding for others being a relatively rare occurrence in most activities, our collection of these particular settings where they are reasonably common, allows us to point at its existence and its main defining features.

Analysis: collaborating in the expression of others

In this section we examine instances where one participant sounds for copresent others through vocal resources tied to the others’ accountable sensory experiences, including pain, strain, and taste. Through vocalizing during the coparticipant’s bodily events, the speaker claims access to their body and experience, and displays themselves as co-experiencing. To be clear, this is not to suggest that the speaker is claiming to be undergoing the same experiential or sensational events, but rather that the speaker uses their vocalizing to enact the event as one to which the speaker has access, thus displaying embodied understanding. It is one way to publicly accomplish Merleau-Ponty’s (Citation1964a) “compresence”. In particular, we aim to demonstrate that the participants connectFootnote2 the vocalizations to others’ bodies through temporal coproduction, that this connection enacts a distributed speakership concerning the ostensible experience, and that in doing this sounding for the other’s experience the speakers undertake certain actions, such as empathizing and instructing.

Sounding other’s pain

Let us first return to our above case where the display of pain is jointly accomplished during a visit to a doctor’s office, occasioned by a sore arm, which eventually gets diagnosed as a tennis elbow. As the extract (represented below as 2) begins, the doctor and the patient are sitting facing each other. The patient’s arm is outstretched, and the doctor is holding her hand in his. He has been testing a few positions of the underarm that have not yet turned out to be painful. The doctor launches a new so-prefaced diagnostic question (lines 01–02) which marks it as being generated through inference (Bolden, Citation2006) and simultaneously moves his other hand to the patient’s elbow and palpates it (see, Figure 1). His turn assumes a no pain response, which turns out not to be the case, as the patient displays pain (lines 02–03).

Extract 2. Tennis Elbow; TS-GP03-17 (, expanded)

As the doctor palpates the patient’s elbow, the patient’s upper torso makes a small jerking movement backward, during which she takes a sharp in-breath (lines 02–03), which amounts to the beginning of an embodied pain display (Weatherall et al., Citation2021). Immediately latched to this, the doctor’s uuuw (line 04) responds to the patient’s display. The patient and doctor each further verbalize that the palpated spot is painful (lines 03–09), treating the pain as belonging to the patient’s body. In-breaths have been associated with pain responses in experimental research (Jafari et al., Citation2017). Although not a typical response cry for pain under Goffman’s rubric (Goffman, Citation1978), the patient’s sharp intake of breath has similar relevant features: it demonstrates the pain with immediacy, which is helpful for pinpointing a diagnostically relevant spot on the body; and it “floods out,” or is produced in a particular moment of the interaction that enacts spontaneity and genuineness. The doctor’s vocalization similarly does this immediacy, albeit just after the patient. The uuuw documents the doctor observing (Figure 2) and possibly feeling the other’s pain through the recoil, ratifying the precise timing (and thus bodily location) of the pain expression. It also puts the doctor’s empathetic stance on record right away by prioritizing a conventionally emotion-relevant vocalization over further diagnostic inquiry (indeed, this kind of sound has been noted for its rarity in prior literature on diagnosis, which normally finds doctors prioritizing an analytic, noninvolved stance; Heath, Citation1989, Citation2002; Heritage & Stivers, Citation1999). These sounds not only note the presence of the pain and its bodily trigger location, but they also transform the investigation of the elbow into a jointly achieved sensory occurrence. The doctor does more than inquire about or observe the pain, but participates in its expression. The uuuw sounds on the patient’s behalf (and we have another instance with a different doctor producing a similar sound). Together, the doctor and patient organize a joint expression of the putative pain experience, even though their sensorial access to it is clearly different and treated as different, since the pain is located by both parties as in the patient’s body. A pain experience is constructed jointly through the precise temporal placement of the sound, while the sounder implicitly claims entitlement to coparticipate in its enactment.

Sounding other’s strain

Sounding for others can be especially useful in the instruction of proprioception in synchronously moving bodies. In dance classes, for example, teachers regularly vocalize strain at the precise moments when strain is due in students’ ongoing performance, such as when needing to create tension or sharp moves. is taken from a class where a Charleston combination is being taught. The lead dancers in the dancing couples need to bring their partners from their side to the front and back again, which requires some well-timed energy twice during the pattern (during beats 1, 2, and 5). Specifically, the lead dancers must create sufficient tension between the partners to reverse the follow dancers’ movement trajectory. During the extract the teacher is not dancing herself but observing the students and providing the Charleston rhythm with vocalizations (Keevallik, Citation2021). The vocalizations sound not only for the timing, but also the quality of the movement, and specifically enact the strain that ought to occur in the lead dancers’ bodies on beats 1, 2, and 5 in line 02. In line 03 the teacher then praises one of the couples for their improved performance. The transcript features beat numbers as danced by the students, aligned with teacher’s vocalized syllables.

Extract 3. Tension between dance partners (in Swedish); Höst 2, klipp 01 16:00

In line 01 the students are supposed to dance a basic Charleston step, side-by-side, in a rhythmical but relaxed manner, which is also reflected in the teacher’s relatively immobile body (Figure 3; the teacher in yellow, unfortunately behind her partner) as well as in the simple open syllables that often provide the baseline rhythm at dance classes. In line 02, however, the first syllable KRRhahh is qualitatively different: it features a lengthened trill that extends across the two first beats of the step pattern, and a heavy outbreath at the end. It is also louder than the previous syllables. During that time the leads are supposed to redirect the follows’ energy so that they move forward, and to do that they need to build tension between them. During the next two beats the forward movement is again relaxed, which is reflected in the quieter open syllables chaga. Then, on beat 5 (line 02), the follows should end up in the front of the leads and their movement energy needs to be reversed again. This is accompanied by a markedly louder voice and a long syllable featuring higher vowels in the form of a diphthong uo (as opposed to the open back vowels used for the rest of the sequence). The vocalization QUOO is furthermore uttered with tense glottis, with the air barely seeping through, and with a clear glottal stop syllable onset (marked with “Q”). In addition, or perhaps in order to produce that tense sound, the teacher is also herself straining her body in parallel to the dancing leads (see, Figure 4). This is thus an instance where the teacher is not actually performing the strenuous dance move (she is not moving a partner) but chooses to accompany the motion in real time by vocalizing and embodying extreme strain at the very moment when the dancers’ bodies should be experiencing it (see, for example, the rightmost person in Figure 4). Thus, the teacher vocalizes not only to provide rhythmic beats and coordinate the class, but uses the opportunity given by the vocalizations to additionally perform the embodied phenomena the students should undergo – in this case, enacting peaks of strain in real time. The sounding both empathizes with and instructs the students regarding the proprioceptive aspects of the synchronous move, as well as displays a co-experiencing of the strain through the embodied enactment. The teacher thereby accomplishes compresence in the dance and entitlement to sound the strain that is synchronously supposed to be present in the lead students’ bodies.

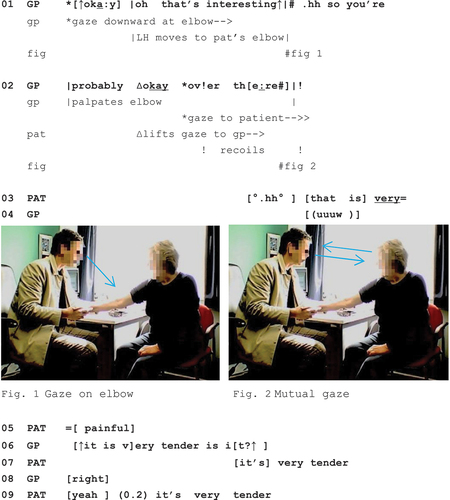

In another instructive context, Pilates classes, we can likewise find displays of strain where the strain does not originate in the speaker’s own body, but is or should be present in the bodies of others (this happens repeatedly during every class, see another example of the teacher sounding for a “boat pose” in Hofstetter & Keevallik, Citation2023). is taken from a Pilates class where the teacher has just demonstrated a new exercise called helicopter that implies moving legs and hands in a circular motion but to opposite sides while balancing on the buttocks. This is the very first time that the students try it out and the teacher uses a large gesture and a strain sound to accompany the exercise.

Extract 4. Helicopter (in Estonian); 2018 c2

The teacher times the beginning of the exercise by uttering a slightly lengthened ja “and” (which is characteristic of this activity, Keevallik, Citation2020b). She simultaneously launches a two-hand gesture that iconically shows the required circular movement of the legs (Figures 5,6). As she dips into the shape, she produces a strain sound, a nasal vocalization with a glottal onset and narrow glottis throughout (see about similar use of voice for incitement of others in various sports in Reynolds (Citation2021)). The vocalization ends in a very high pitch, iconically marking the legs’ arrival back at the top position together with the arms arriving in the upward position (Figure 7). The teacher’s bodily- vocal performance makes the exercise visually and audibly available, highlighting the shape, trajectory, and most relevantly for this paper, the ostensible proprioceptive experience of the exercise and its inherent strain throughout the trajectory. The strain sound further extends over a reasonable time frame of the complete move, and the gesture and sound are instructive, indicating how long the exercise should extend. The multimodal display is also empathetic with the struggling students, thus achieving compresence in the exercise as well as entitlement to vocalize the experience even while not under strain herself. However, at this particular instance the vocally performed strain is not quite synchronous with what all the other bodies are undergoing, as the students are each toiling with their own tempo (see the variable leg heights in Figure 6), even though everybody is coordinated to try out the same move. The bodilyvocal production is thus also prospectively instructive, the experience is displayed to ease not only ongoing, but also upcoming attempts at performing the exercise.

Instructors across activities sound when others need scaffolding, marking matters that need attention. While this makes the sounding practice useful for demonstration (Keevallik, Citation2021; Tolins, Citation2013), in the above examples, the referents emerge near-synchronously and in a separate body from the instructor. The instructor relies on, and enacts, rights to sound on behalf of student bodies, apparently drawing on her own embodied experiences to highlight qualities and sensations useful for proper performance. Real-time scaffolding and correcting of bodily moves thus emerges as one major affordance of the sounding for others practice.

Sounding other’s tasting

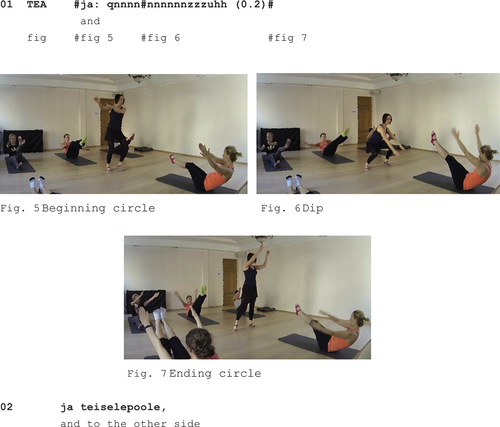

We now move on to a different sense, that of taste, and explore how sounding for others can display coparticipation in a sensing event while maintaining ambiguity as to whether the sounding is an instruction or an (empathetic) acknowledgment. In our chosen setting, parents are sounding for their infants during a meal. We specifically selected moments when the parents are not eating and hence their vocalizations are apparent as sounding for the infant who is eating. In , Mum uses various sounds when their 5-month-old infant appears distracted while eating a new food. Earlier in this episode, Mum demonstrated concern that the infant might be disinterested in eating (asking “you not sure?,” “do you not like it?,” see also line 01 in ). The mother sounds with lip-smacks (transcribed as (.)m(p)t(ḁ) to render the exact phonetic qualities) and gustatory mmms that work to enact the infant’s experience of eating and tasting (see detailed arguments in Wiggins & Keevallik, Citation2021a, Citation2021b), as well as encourage the relevant eating practices: chewing and swallowing the food. They involve distinct sequential, temporal, articulatory, and, crucially, embodied features that accomplish the sounds as for another.

Extract 5. Yummy; McD003_0424

The sequence begins with a question about whether the infant likes the food (line 01) and Mum’s attention moves soon after (line 03) to check as to whether the infant still has food in their mouth. The request to “see” inside the infant’s mouth is followed immediately by a series of lip-smacks (line 04), which model the opening-and-closing movement that would both facilitate chewing and enable visibility of food in the mouth. The focus here is thus not only on tasting (and “liking”), but also on chewing food. The infant then opens their mouth while also turning their eye gaze to Mum. Perhaps ironically, this movement then results in some food falling out, though this at least provides evidence that there was actually food in the mouth.

The mutual eye gaze that is achieved in line 04 (and continues to line 10) provides the right conditions for a gustatory mmm (Wiggins & Keevallik, Citation2021a) soon after on line 06, which re-emphasizes the tasting event that is ongoing with the chewing. This is produced with Mum’s lips tightly pressed together and head slightly raised back (Figure 8) and thus features visual as well as auditory elements. The close physical proximity of the participants and the exaggerated closing and opening of the mouth – both with the gustatory mmms and the lip-smacks (see also line 08) – may encourage the infant to mirror the mouth movements and certainly there is evidence of this on lines 04 to 09. Regardless of whether these displays actually encourage the infant, the sounding practices of Mum, combined with facial gestures, leaning in, and positioning her face close to the infant, work to enact tasting and eating on behalf of the infant. The mmm in line 10 is prosodically upgraded through a pitch change from prior mmms (e.g., line 06) and the following yummy lexically formulates and makes explicit the pleasurable orientation of the mmm; combined with the preceding sequence of mouth movements and sound objects, the ongoing sensory experience is thereby constructed as assessment-relevant for the infant (see, Wiggins & Keevallik, Citation2021a). This assessment is only relevant when some eating and tasting has occurred, processes which required the infant to have followed along with Mum’s enactments. The two coordinate together in this respect, as Mum’s sounds have been precisely coordinated with the events of the infant’s mouth. Through continual bodily mirroring and sounding, there is abundant evidence of the two participants being highly attuned to each others’ bodies.

With this extract, we have demonstrated how parental sounding practices can both chime in with the infant’s sensory experience while it is supposed to be ongoing, and also be tailored to instruct the relevant moves required for eating solid foods. The highly salient vocal and embodied production of lip-smack particles and mmms, featuring extended sounds, rhythmicity, and extreme pitch movements, allow the parent to draw attention to specific, currently-relevant sensations and movements in the infant’s own body. Through smiles, Mum’s laughter, raised eyebrows and subsequent lexical items such as yummy, the eating experience is furthermore framed as a pleasant one. The observing, empathetic and instructive aspects of sounding for others are here intertwined in the real-time achievement of the sensoriality of taste and the proprioception of jaw movements. Concerning sounding for others more generally, this analysis exemplifies how participants can remain ambivalent about whether they are empathizing, instructing, or both; most critical is that the sounding for others practice permits co-participation in sensory-relevant activities.

Discussion

In this paper, we have shown examples of one person sounding for others, using the voice, in particular non-lexical vocalizations, to capture some aspect of the others’ bodily experience. The practice is used across activities for tasks including coproducing sensations, expressing empathy, coordinating multiple bodies together, and instructing. Through the temporal positioning in immediate relation to the experiencing and moving bodies — in other words, by temporally fitting the vocalization to another’s bodily event — these vocalizations achieve their meaning and legitimacy as “expressing that very experience”. Likewise, the qualitative fitting of the vocalizations with others’ sensory events binds the participants’ experiences and vocalizations into one whole. In the following, we will discuss the contribution of this study with respect to the broader array of non-lexical vocalizations, the temporal coproduction of the practice, the joint accomplishment of sensorial events, as well as the actions carried out through its use.

Non-lexical vocalizations used for coproduction of sensation

While research on non-lexical vocalizations is scarce (Dingemanse, Citation2018, Citation2020; Keevallik & Ogden, Citation2020; Reber, Citation2012), most of the existing work targets onomatopoeia and recently ideophones – words that depict sensory experience, used in regular conversation (Dingemanse, Citation2017). The sounding for others practice, however, does not depict, since the event being sounded for is occurring almost at the same moment; the referent is not removed by time or place as in Clark’s (Citation2016) framework for depictions. This study instead broadens the horizon of vocalization studies by targeting sounds emanating from current sensory experiences: the pain sounds enact ongoing pain, the strained voice vocalizes right now the strain happening in the students’ bodies, and the gustatory mmms and lip-smacks enact current tasting. This is a specific body-based subset of all non-lexical vocalizations, characterized by the immediate representation of the bodily sensation and reflective of the bodily contingencies of production, such as the mmm being producible with a closed mouth full of food. In the case of strain, this representation is furthermore impossible to perform without employing muscular strain in the vocal apparatus as well as the abdomen, thus creating the necessary bodily bases that the sound indexes (Hagins & Lamberg, Citation2006; Massery et al., Citation2013; Tammany et al., Citation2021; Welch & Tschampl, Citation2012). It is precisely this bodily immediacy that makes these kinds of vocalizations useful in the sounding for others practice. While adjacent talk may provide lexical specification of the sounds’ local meaning (e.g., “it is sore,” “yummy”), the non-lexical elements allow for highly context-specific modifications in production. Prosody alterations can suggest suitable intensity, sharpness or severity of the current bodily experience while length can be modified, respective to the event sounded for, to suggest intimate connections between the sensation and the vocalization. The sounds are accountable and recognizable indices of bodily events. They may feature a degree of conventionalization but are most probably less language specific than, e.g., ideophones (Dingemanse, Citation2018) or surprise tokens.

Close temporal coproduction of (individual) sensations

The mechanisms that connect one person’s voice to another’s body are the temporal placement of the sound at the exact moments when the other is assumedly sensing pain, taste, or strain and fitting the sound choice for the kind of embodied experience underway. Broadly speaking, the sounding is synchronous with those experiences, which is in contrast to most vocal behavior (talk) being sequentially organized into one-at-a-time speaker turns. However, there are also fine differences in the temporal organization of the beginning and the end of the sounds identified: while the doctor’s pain cry responds with immediacy to the patient’s recoil and in-breath (initial phases of a pain display, Weatherall et al., Citation2021), the parent’s mmm is timed to be simultaneous with the putative taste emerging in the infant’s mouth, and the instructor’s strained qnnnnnnnnnnmmmuhh is launched slightly before most students have started the strenuous move. We thus documented three slightly different organizations of the sounding practice: instances of responsive sounding by the doctor (even though the sound is uttered at the exact moment when it could also have been said by the patient), synchronous sounding with the taste and the precise strained moment in the dance, as well as anticipatory sounding that features micro-sequentiality (Mondada, Citation2021a) and emerges as instructive (such as in the lip-smacks and the Pilates move). The sounding makes both empathizing and instructing potentially relevant, and thus the vocalizer is vulnerable to being seen as doing either or both. The relative anticipatory timing in instructional contexts may lean into claiming stronger rights to know and access the sensation, and thereby do instruction more obviously. In contrast, the relative delay in the doctor’s pain cry for the patient backs away from such a claim, which may be diagnostically relevant. Further investigations can elucidate the different contingencies and results of these timings. Intersubjectivity is achieved near-synchronously, by one person sounding the other’s current sensory experience, as opposed to producing consecutive actions in interactional sequences, such as instructing in advance of the event what the sensation is going to be (e.g., in classes of professional tasting skills, Mondada, Citation2021b).

Joint performance of a sensation

Through the temporally precise implementation of a suitable vocalization with the ostensible experience by other, the emerging action as well as compresence is achieved across different participants: one undergoing an experience (such as the infant or the lead dancer in the couple) and the other sounding that very experience, thus distributing the resources to perform the action. The practice thereby fundamentally undermines the conceptualization of action and speakership as tied to an individual body and voice deployed by one person at a time. The role of a sensing and expressing agent in interaction is here assembled across participants, further problematizing the conduit-metaphor conceptualization of what it means to communicate, and to be a speaker or a receiver. An agent is not an individual sender of information but an assembly of bodily and vocal resources that may be variably distributed across participants.

Functions of the sounding for others practice

The two main functions emerging from the above collection of cases are the performance of empathy and instruction. While empathy has been explored as a sequential phenomenon (Heritage, Citation2011; Ruusuvuori, Citation2005), it has also been shown that affiliative responses are regularly launched early in relation to the prior turn (Pomerantz, Citation1984; Vatanen et al. Citation2021). The sounding for others practice is extreme in that it vocalizes the ongoing experience in another, not as an onlooker, but as a coproducer of that very experience, thus emerging as highly empathetic. Sounding for others permits a “being with” that is attuned (both in the lay sense and in the phenomenological sense, Merleau-Ponty (Citation2002) to coparticipants. Along similar lines, Bavelas et al. (Citation1986) showed that the mimicked gestures on behalf of another were distinctly interactional, in that their frequency increased when the other was visually available.

The practice also involves the participants instructing various bodily skills in real time, such as tasting and performing strenuous moves. Instruction and compliance have been shown to occur in overlap in a range of human activities (Deppermann et al., Citation2021; Mondada, Citation2014a), especially in series of instructions emerging across time. Time-critical instruction of strain, however, can be provided entirely synchronously with, e.g., dancing bodies, if only because its precise timing ultimately needs to be acquired in consecutive occasions of practice. Instructors, doctors, and other experts (such as grown-up eaters) furthermore exert their entitlement to sound those experiences for non-experts in a manner that is strikingly intimate, being an immediate representation of their bodies, as opposed to most verbal instruction and formulations of others.

Conclusion

Occurring in a close temporal fit with others’ bodily engagements, the sounding for others practice illustrates how we give voice to each others’ sensorial experiences, including proprioception, and thereby jointly produce sensation as social. Instead of formulating those activities purely through words, non-lexical vocalization practices seem especially fitted to join in others’ bodily lives in real time. The connection between specific sounding practices and bodies was first impressionistically described by Goffman (Citation1978) as being “response cries” to ostensible bodily events, often unexpected ones. Several of these “cries” have since been described as semi-conventionalized items used for specific communicative purposes, such as sharing the experience of being out-of-breath with your jogging partner (Pehkonen, Citation2020) or voicing strain to coordinate a lift (Keevallik & Ogden, Citation2020). As the other-oriented vocalizations discussed in the current paper are something that the other could have uttered themselves at those very moments (and sometimes actually do so), they illustrate the social and distributed nature of not only actions and resources, but also sensoriality. In other words, they demonstrably achieve compresence – one participant using their own previous bodily experiences as a guide to current sensations in others’ bodies and claiming entitlement to those by producing relevant sounds.

By establishing how vocal practices, including language-marginal vocalizations, are lodged in the minute coordination of bodies in real time, we can ultimately arrive at a more ecologically valid understanding of human vocal behavior as inherently dialogic and distributed, rather than monologic and individual. A spotlight on sounding practices enables us to target central issues in linguistics, such as what the limits of language are and what kinds of tasks can be accomplished through vocally joining in others’ moves or experiences. By making use of the specific affordances of voice, intonation, loudness, and sound quality, vocalizations constitute a specific means of accomplishing sociality that has so far flown below the radar of studies in communication, having been treated as perhaps too subtle and evasive, or too chaotic. This paper provided examples of the systematic deployment and shared understanding of sounds for specific tasks, thereby also demonstrating that the boundary between language and non-language is fuzzy: minimally conventionalized vocalizations still provide a means of immediate and even synchronous displays of intersubjectivity. The practice of sounding for others thus constitutes yet another empirical finding in support of the dialogic theories of language and communication, where utterances are understood to be intersubjective accomplishments (Du Bois, Citation2014; Linell, Citation2009), and human sociality to be inherently dialogic, with every single move reflexively anchored in the ongoing interpretation by the other.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for discussions with Agnes Löfgren and Hannah Pelikan, the advice by an anonymous reviewer, and guidance by the journal editor.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. By empathizing we mean providing “an affective response that stems from the apprehension or comprehension of another’s emotional state or condition, and that is similar to what the other person is feeling or would be expected to feel” (Eisenberg & Fabes Citation1990).

2. In Sacks’ terminology, this would be a form of tying procedure, see Sacks (Citation1992:150) et passim, see Küttner (Citation2020) for discussion of tying procedures beyond sequentiality.

References

- Anikin, A., & Lima, C. F. (2018). Perceptual and acoustic differences between authentic and acted nonverbal emotional vocalizations. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 71(3), 622–641. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2016.1270976

- Bakhtin, M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays (M. Holquist, ed. Trans. C Emerson & M Holquist). University of Texas Press.

- Bavelas, J. B., Black, A., Lemery, C. R., & Mullett, J. (1986). ‘I show how you feel’: Motor mimicry as a communicative act. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(2), 322–329. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.2.322

- Bolden, G. B. (2006). Little words that matter: Discourse markers “so” and “oh” and the doing of other-attentiveness in social interaction. Journal of Communication, 56(4), 661–688. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00314.x

- Broth, M., & Keevallik, L. (eds). (2020). Multimodal Interaktionsanalys. Studentliterattur.

- Cantarutti, M. (2020) The Multimodal and Sequential Design of Co-Animation as a Practice for Association in English Interaction. Doctoral thesis. University of York.

- Cekaite, A. (2016). Touch as social control: Haptic organization of attention in adult–child interactions. Journal of Pragmatics, 92, 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2015.11.003

- Clark, H. (2016). Depicting as a method of communication. Psychological Review, 123(3), 324–347. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000026

- Couper-Kuhlen, E., & Selting, M. (2017). Interactional linguistics: Studying language in social interaction. Cambridge University Press.

- Deppermann, A., & Günthner, S. (eds). (2015). Temporality in Interaction. John Benjamins.

- Deppermann, A., Mondada, L., & Doehler, S. P. (2021). Early responses: An introduction. Discourse Processes, 58(4), 293–307. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2021.1877516

- Dingemanse, M. (2017). Brain-to-brain interfaces and the role of language in distributing agency. In N. J. Enfield & P. Kockelman (Eds.) Distributed Agency (pp. 59–66). Oxford University Press.

- Dingemanse, M. (2018). Redrawing the margins of language: Lessons from research on ideophones. Glossa: a Journal of General Linguistics, 3(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.444

- Dingemanse, M. (2020). Between sound and speech: Liminal signs in interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1),188–196. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1712967

- Di Paolo, E. A., Cuffari, E. C., & De Jaegher, H. (2018) Linguistic bodies: The continuity between life and language. MIT Press. Retrieved October 29, 2020, from https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/linguistic-bodies

- Du Bois, J. W. (2014). Towards a dialogic syntax. Cognitive Linguistics, 25(3),359–410. De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2014-0024

- Eisenberg, N., & Fabes, R. A. (1990). Empathy: Conceptualization, measurement, and relation to prosocial behavior. Motivation and Emotion, 14(2), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00991640

- Enfield N. J. (2017). Elements of agency. In N. J. Enfield & P. Kockelman (Eds.), Distributed agency (p. 3-8). Oxford University Press. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190457204.001.0001/acprof-9780190457204

- Gibson, W., & Vom Lehn, D. (2020). Seeing as accountable action: The interactional accomplishment of sensorial work. Current Sociology, 68(1), 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392119857460

- Goffman, E. (1978). Response cries. Language, 54(4), 787. https://doi.org/10.2307/413235

- Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of Talk. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Goodwin, C. (1986). Between and within: Alternative sequential treatments of continuers and assessments. Human Studies, 9(2), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00148127

- Goodwin, C. (1993). Recording human interaction in natural settings. Pragmatics, 3(2), 181–209. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.3.2.05goo

- Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional vision. American Anthropologist, 96(3), 606–633. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1994.96.3.02a00100

- Goodwin, C. (2004). A competent speaker who can’t speak: The social life of Aphasia. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 14(2), 151–170. https://doi.org/10.1525/jlin.2004.14.2.151

- Goodwin, C. (2018). Co-Operative Action. Cambridge University Press.

- Hagins, M., & Lamberg, E. M. (2006). Natural breath control during lifting tasks: Effect of load. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 96(4), 453–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-005-0097-1

- Haviland, J. (2007). Master speakers, master gesturers: A string quartet master class. In S. Duncan, E. Levy, & J. Cassell (Eds.), Gesture and the dynamic dimension of language: Essays in honor of David McNeill (pp. 147–172). John Benjamins.

- Heath, C. (1989). Pain talk: The expression of suffering in the medical consultation. Social Psychology Quarterly, 52(2), 113. https://doi.org/10.2307/2786911

- Heath, C. (2002). Demonstrative suffering: The gestural (re)embodiment of symptoms. Journal of Communication, 52(3), 597–616. Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2002.tb02564.x

- Heritage, J., & Raymond, G. (2005). The terms of agreement: Indexing epistemic authority and subordination in talk-in-interaction. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68(1), 15–38. SAGE Publications Inc. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250506800103

- Heritage, J., & Stivers, T. (1999). Online commentary in acute medical visits: A method of shaping patient expectations. Social Science & Medicine, 49(11), 1501–1517. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00219-1

- Heritage, J. (2011). Territories of knowledge, territories of experience: Empathic moments in interaction. In T. Stivers, L. Mondada, & J. Steensig (Eds.), The morality of knowledge in conversation (pp. 159–183). Cambridge University Press.

- Hofstetter, E. (2020). Nonlexical “moans”: Response cries in board game interactions. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 42–65. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1712964

- Hofstetter, E., & Keevallik, L. (2023). Prosody is used for real-time exercising of other bodies. Language & Communication, 88, 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2022.11.002

- Holt, E., & Clift, R. (eds) (2007) Reporting talk: Reported speech in interaction. Cambridge University Press.

- Ironside, R. (2018). Feeling spirits: Sharing subjective paranormal experience through embodied talk and action. Text & Talk, 38(6), 705–728. https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2018-0020

- Jafari, H., Courtois, I., Van den Bergh, O., Vlaeyen, J. W. S., & Van Diest, I. (2017). Pain and respiration: A systematic review. Pain, 158(6), 995–1006. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000865

- Jefferson, G. (1986). Notes on ‘latency’ in overlap onset. Human Studies, 9(2), 153–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00148125

- Jenkins, L. (2015). Negotiating pain: The joint construction of a child’s bodily sensation. Sociology of Health & Illness, 37(2), 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12207

- Keevallik, L. (2021). Vocalizations in dance classes teach body knowledge. Linguistics Vanguard, 7(s4), De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2020-0098

- Keevallik, L. (2020b). Grammatical coordination of an embodied action: The Estonian ja ‘and’ as a temporal coordinator of pilates moves. In Y. Maschler, S. Pekarek Doehler, & J. Lindström (Eds.), Emergent syntax for conversation: Clausal patterns and the organization of action (pp. 221–244). John Benjamins.

- Keevallik, L., & Ogden, R. (2020). Sounds on the margins of language at the heart of interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 1–18. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1712961

- Keevallik, L. (2020a). Linguistic structures emerging in the synchronization of a pilates class. In C. Taleghani-Nikazm, E. Betz, & P. Golato (Eds.), Mobilizing others: Grammar and lexi within larger activities (pp. 147–173). John Benjamins.

- Küttner, U. -A. (2020). Tying sequences together with the [That’s + Wh-Clause] format: On (retro-) sequential junctures in conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(2), 247–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1739422

- La, J., & Weatherall, A. (2020). Pain displays as embodied activity in medical interactions. In S. Wiggins & K. O. Cromdal (Eds.), Discursive psychology and embodiment: Beyond subject-object binaries (pp. 197–220). Springer Nature.

- Lerner, G. H. (2002). Turn-sharing: The choral co-production of talk-in-interaction. In C. E. Ford, B. A. Fox, & S. A. Thompson (Eds.), The Language of Turn and Sequence (pp. 225–256). Oxford University Press.

- Lerner, G. H. (1996). On the ‘semi-permeable’ character of grammatical units in conversation: Conditional entry into the turn space of another speaker. In E. Ochs, E. A. Schegloff, & S. A. Thompson (Eds.), Interaction and grammar (pp. 238–276). Cambridge University Press.

- Lindström, J., Lindholm, C., Grahn, I. L., Keevallik, L. (2020). Consecutive clause combinations in instructing activities: Directives and accounts in the context of physical training. In Y. Maschler, S. Pekarek Doehler, J. Lindström (Eds.), Emergent syntax for conversation: Clausal patterns and the organization of action (pp. 245–274). John Benjamins.

- Linell, P. (2009). Rethinking language, mind, and world dialogically: Interactional and contextual theories of human sense-making. Information Age Publishing.

- MacMartin, C., Coe, J. B., & Adams, C. L. (2014). Treating distressed animals as participants: I know responses in veterinarians’ pet-directed talk. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 47(2), 151–174. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2014.900219

- Massery, M., Hagins, M., Stafford, R., Moerchen, V., & Hodges, P. W. (2013). Effect of airway control by glottal structures on postural stability. Journal of Applied Physiology, 115(4), 483–490. American Physiological Society. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01226.2012

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1964a). Signs ( Tran. R. C. McCleary). Northwestern University Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1964b). The philosopher and his shadow. In R. C. McCleary (Eds.), Signs (pp. 159–181). Northwestern University Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (2002). The phenomemology of perception ( Tran. C. Smith). Routledge.

- Meyer, C., Streeck, J., & Jordan, J. S. (Eds). (2017). Intercorporeality: Emerging socialities in interaction. Oxford University Press.

- Mondada, L. (2018). The multimodal interactional organization of tasting: Practices of tasting cheese in gourmet shops. Discourse Studies, 20(6), 743–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445618793439

- Mondada, L. (2019a). Contemporary issues in conversation analysis: Embodiment and materiality, multimodality and multisensoriality in social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 145, 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2019.01.016

- Mondada, L. (2019b). Transcribing silent actions: A multimodal approach of sequence organization. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 2(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v2i1.113150

- Mondada, L. (2020). Audible sniffs: Smelling-in-interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 140–163. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1716592

- Mondada, L. (2021a). How early can embodied responses be? Issues in time and sequentiality. Discourse Processes, 58(4), 397–418. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2020.1871561

- Mondada, L. (2021b). Orchestrating multi-sensoriality in tasting sessions: Sensing bodies, normativity, and language. Symbolic Interaction, 44(1), 63–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/symb.472

- Mondada, L. (2004). ’You see here ?’: Voir, pointer, dire. Contribution à une approche interactionnelle de la référence. In A. Auchlin (Ed.), Structures et Discours. Mélanges Offerts à Eddy Roulet (pp. 433–454). Nota Bene.

- Mondada, L. (2014b). Shooting as a research activity: The embodied production of video data. In M. Broth, E. Laurier, & L. Mondada (Eds.), Studies of video practices: Video at work (pp. 33–62). Routledge.

- Mondada, L. (2014a). Requesting immediate action in the surgical operating room: Time, embodied resources and praxeological embeddedness. In P. Drew & E. Couper-Kuhlen (Eds.), Requesting in Social Interaction. Studies in Language and Social Interaction (SLSI) (Vol. 26, pp. 269–302). John Benjamins.

- Mondada, L. (2017). Precision timing and timed embeddedness of imperatives in embodied courses of action: Examples from French. In M.-L. Sorjonen, L. Raevaara, & E. Couper-Kuhlen (Eds.), Imperative turns at talk (pp. 65–101). John Benjamins Publishing. Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.jbe-platform.com/content/books/9789027265524-slsi.30.03mon

- Nakassis, C. V. (2018). Indexicality’s ambivalent ground. Signs and Society, 6(1), 281–304. The University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.1086/694753

- Nishizaka, A. (2017). The perceived body and embodied vision in interaction. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 24(2), 110–128. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2017.1296465

- Norén, N., Svensson, E., & Telford, J. (2013). Participants’ dynamic orientation to folder navigation when using a VOCA with a touch screen in talk-in-interaction. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 29(1), 20–36. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2013.767555

- Ochs, E., Schegloff, E. A., & Thompson, S. A. (eds). (1996). Interaction and grammar. Cambridge University Press.

- Ogden, R. (2020). Audibly not saying something with clicks. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 66–89. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1712960

- Okada, M. (2018). Imperative actions in boxing sparring sessions. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2017.1375798

- Pehkonen, S. (2020). Response cries inviting an alignment: Finnish huh huh. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 19–41. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1712965

- Peräkylä, A., & Silverman, D. (1991). Owning experience: Describing the experience of other persons. Text & Talk, 11(3), 441–480. De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/text.1.1991.11.3.441

- Pomerantz, A. (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 57–101). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511665868

- Reber, E. (2012). Affectivity in interaction: Sound objects in English. In Pragmatics & beyond new series (Vol. 215). John Benjamins.

- Reynolds, E. (2021). Emotional intensity as a resource for moral assessments: The action of ‘incitement’ in sports settings. In J. S. Robles & A. Weatherall (Eds.), How emotions are made in talk (pp. 27–50). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Robillard, A. B. (1996). Anger In-the-Social-Order. Body & Society, 2(1), 17–30. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X96002001002

- Ruusuvuori, J. (2005). “Empathy” and “sympathy” in action: Attending to patients’ troubles in finnish homeopathic and general practice consultations. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68(3), 204–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250506800302

- Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on Conversation (G. Jefferson & E. A. Schegloff, Eds. Vol. 1-2). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696. https://doi.org/10.2307/412243

- Sidnell, J. (2006). Coordinating gesture, talk, and gaze in reenactments. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 39(4), 377–409. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi3904_2

- Sidnell, J., & Stivers, T. (eds). (2013). The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

- Stevanovic, M., & Peräkylä, A. (2012). Deontic authority in interaction: The right to announce, propose, and decide. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 45(3), 297–321. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.699260

- Stivers, T. (2008). Stance, alignment, and affiliation during storytelling: When nodding is a token of affiliation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 41(1), 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810701691123

- Tammany, J. E., O’Connell, D. G., Latham, S. E., Rogers, J. A., Sugar, T. S. (2021). The effect of grunting on overhead throwing velocity in collegiate baseball pitchers. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 17479541211005360. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541211005359

- Throop, C. J. (2010). Suffering and sentiment: Exploring the vicissitudes of experience and pain in yap. University of California Press.

- Tolins, J. (2013). Assessment and direction through nonlexical vocalizations in music instruction. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 46(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2013.753721

- Varela, F. J., Rosch, E., & Thompson, E. (1993). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience. MIT Press.

- Vatanen, A. (2018). Responding in early overlap: Recognitional onsets in assertion sequences. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(2), 107–126. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1413894

- Vatanen, A., Endo, T., & Yokomori, D. (2021). Cross-linguistic investigation of projection in overlapping agreements to assertions: Stance-taking as a resource for projection. Discourse processes, 58(4), 308–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2020.1801317

- Weatherall, A., & Keevallik, L. (2016). When claims of understanding are less than affiliative. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(3), 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2016.1196544

- Weatherall, A., Keevallik, L., La, J., Dowell, T., & Stubbe, M. (2021). The multimodality and temporality of pain displays. Language & Communication, 80, 56–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2021.05.008

- Weeks, P. (1996). A rehearsal of a beethoven passage: An analysis of correction talk. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 29(3), 247–290. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi2903_3

- Weeks, P. (2002). Performative error-correction in music: A problem for ethnomethodological description. Human Studies, 25(3), 359–385. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020182018989

- Welch, A. S., & Tschampl, M. (2012). Something to shout about: A simple, quick performance enhancement technique improved strength in both experts and novices. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 24(4), 418–428. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2012.688787

- Wiggins, S. (2002). Talking with your mouth full: Gustatory Mmms and the embodiment of pleasure. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 35(3), 311–336. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327973RLSI3503_3

- Wiggins, S. (2013). The social life of ‘eugh’: Disgust as assessment in family mealtimes: Disgust as assessment in family mealtimes. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(3), 489–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2012.02106.x

- Wiggins, S. (2019). Moments of pleasure: A preliminary classification of gustatory mmms and the enactment of enjoyment during infant mealtimes. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01404

- Wiggins, S., & Keevallik, L. (2021a). Enacting gustatory pleasure on behalf of another: The multimodal coordination of infant tasting practices. Symbolic Interaction, 44(1), 87–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/symb.527

- Wiggins, S., & Keevallik, L. (2021b). Parental lip-smacks during infant mealtimes: Multimodal features and social functions. Interactional Linguistics, 1(2), 241–272. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/il.21006.wig