ABSTRACT

This manuscript maps the modes of dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic by two public organizations in the Czech Republic from its beginning to the present day to identify the final form of their organizational resilience and key factors that influenced it. The Nograšek and Vintar organizational model, which relies on the crucial role of ICT and its dependence on people, processes, structure, and culture, was utilized to achieve this objective. Data were gathered from interviews, organizations’ websites, and internal statistics. The results show both organizations are characterized by “bounce forward” resilience influenced by a high level of digitization, democratic/emancipatory leadership style, professional staff, and supportive organizational culture.

Introduction

In recent decades, the governments of many countries have faced numerous crises and challenges impacting the population and economy and often disrupting the functioning of public administration represented by state organizations. These include terrorist attacks, natural disasters, political instability, economic and financial crises and especially recent socio-economic and health crises caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Some of these social problems, including the COVID-19 pandemic, are problematic because they represent a so-called “black swan:” an unusual, unpredictable and rare event with severe widespread impacts (Alam, Citation2020; Taleb, Citation2007). In connection with the methods by which state and non-state organizations deal with these situations, the concepts of resilience and organizational resilience drew the attention of contemporary scientists. This concept is usually understood as the manner or ability to face these crises while ensuring these organizations’ functioning (Clement et al., Citation2023), or a strategy for its management (Boin & Lodge, Citation2016; Wildavsky, Citation1988). The result can be the organization functioning identically to the way it had before the crisis or the organizational transformation. In the case of the resilience of public organizations, which is the focus of this article, these crises may not only be a test for their survival, but can also be a trigger for opening a “window of opportunity for their change” (T.Kim et al., Citation2021), ideally for their improved functioning.

Following the above, in this article we present the experience of selected public organizations before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, and its effect on their organizational resilience. It’s crucial to highlight that we selected organizations with non-bureaucratic structures and management styles, as well as a high level of digitization. Recent studies have conclusively demonstrated that increased digitization significantly improves the resilience of both governmental and non-governmental organizations. This improvement is primarily achieved by enhancing the agility of their processes and their ability to effectively respond to unforeseen situations, thereby strengthening their overall sustainability (Miceli et al., Citation2021). Additionally, in order to accomplish the majority of the objectives of these organizations, a significant number of employees with flexible and innovative skills, and the ability to apply them, are required. As a result, it can be assumed that they will be better prepared to handle unexpected situations brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, our objective is to map the modes of dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic in two public organizations in the Czech Republic from its beginning to the present day to identify the final form of their organizational resilience and key factors that influenced it. In these situations, public organizations are logically forced to manage the crisis and ensure the continuation of their operations. We focus on individual periods to compare the external pressures caused by the pandemic and the internal organizational changes as a response to them. In this context, it has been proven that the timing of resilience, meaning before, during, or after a crisis, is very important (Clement et al., Citation2023; Meerow et al., Citation2016; Therrien et al., Citation2021).

To achieve this goal, we used the model of Nograšek and Vintar (Citation2014), which enables the examination of organizational transformation in the current era of the growing use of digital technologies. It views the organization as a system composed of five interrelated elements (technology/ICT, people, processes, culture, and structure), where ICT is dependent on the remaining elements and plays a key role as a trigger and driver of organizational transformation. The key reason for choosing this model is that its elements have a relatively general nature (except ICT), and within them it is possible to identify the absolute majority of all relevant and specific factors that can influence organizational resilience. We primarily use this model to assess the significance of all the variables and their interdependence in terms of direction, ways, and strength.

The following text is divided into four parts. In the first part we define resilience, organizational resilience, forms and levels of resilience, and characterize the resilience of public organizations and the possibilities of their investigation. Subsequently, we present key information about the method of data collection and analysis and then our findings, which we summarize and compare with the results of previous studies in the conclusion.

Literature review

Resilience and organizational resilience, forms, and levels of resilience

Authors usually put resilience in the context of a response to crises, disasters, and their management. It represents historically the central concept in understanding complex and interconnected systems across different academic disciplines such as geography, urban planning, environmental studies since the mid-1970s and in public management and administration since the end of the 1980s (e.g., Chelleri & Baravikova, Citation2021; MacKinnon & Derickson, Citation2013; Meerow et al., Citation2016; Wildavsky, Citation1988). The problem is that there is no agreement as to whether resilience represents “the ability to deal with a crisis,” “the process of managing it,” or “an outcome of successful crisis handling” (Boin et al., Citation2013).

In general, resilience is not well and clearly defined in the existing literature because scholars cannot agree on what resilience means, and therefore there is a large number of diverse and highly contested definitions (see Meerow et al., Citation2016; Raetze et al., Citation2022; Shen et al., Citation2023). Logically, this is also the case of organizational resilience.

In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of studies dealing with organizational resilience, especially of public organizations, in response to the shock caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 (e.g., Fischer et al., Citation2022; Plimmer et al., Citation2022; Rajala & Jalonen, Citation2022). The problem is that there is a lack of a standard definition of organizational resilience. According to Paeffgen, (Citation2023), six different definitions of organizational resilience can be identified—“the ability to cope with adversity,” “the ability to adapt to changes or crises,” “a set of organizational capabilities,” “recovering from shocks and stresses,” “the capacity to prepare for or overcome stresses,” and “responding to changes and emergencies.” The studies above define organizational resilience mostly as “the ability to absorb shock and adapt to the new normal.” These authors claim that the benefits of resilient organizations include either their reduced signs of decline and faster recovery, the ability to redistribute resources during turbulent events efficiently, or the capacity to identify the changes that matter most and effectively prioritize them, including resource reallocation. Resilient organizations thus have the ability for continuous, positive, and dynamic adaptation and can transform faster than those lacking these capabilities (Butkus et al., Citation2024). The reason is that the essential element of organizational resilience rests in organizations’ ability to utilize the knowledge and experience gained while dealing with crises caused by unusual, unpredictable and rare events (Butkus et al., Citation2023).

Following the above, two different conceptualizations (forms, pathways) of resilience are usually used in the existing literature: “bounce back” or “bounce forward” (also called “engineering” or “recovery” resilience in the first case and “ecological” or “transformative” resilience in the second) (Bartuseviciene et al., Citation2022; Mihotić et al., Citation2023). The core distinction between them is whether the new equilibrium is the same as the status quo or whether new structures emerged during the response to the crisis. In this context, Clement et al. (Citation2023) identified a third form (pathway) of resilience labeled “bounce beyond”. While “bounce forward” leads to the improvement of the functioning of the system, “bounce beyond” represents the implementation of improvements and at the same time the increase of capacity to manage difficult situations through newly adopted solutions and practices. According to these authors, the “bounce forward” strategy is in the case of organizational resilience more focused on the re-organization of work and work from home (WFH), and the “bounce beyond” strategy is more focused on digitalization in general.

In addition to different forms of resilience, it is possible to distinguish “multi-level” and “single-level” resilience (Linnenluecke & Griffiths, Citation2010), which are significant with regard to whether the object of investigation is an organization (in the first case) or an individual (in the second case). In this context, Fischer et al. (Citation2022) recommend combining both these approaches because they believe that an organization can only be as resilient as its staff, but organizational resilience can also foster individual resilience.

Factors influencing organizational resilience during a crisis and gaps in current literature

The studies published so far that deal with factors affecting the resilience of organizations during a crisis can be categorized into two streams, depending on whether they focus on factors influencing “organizational resilience” or “social resilience.” In this context, Keck and Sakdapolrak (Citation2013) defined “social resilience” as consisting of the following three dimensions:„coping capacities“as the ability of social actors to cope with and overcome all kinds of adversities, „adaptive capacities“as their ability to learn from past experiences and adjust themselves to future challenges in their everyday lives, and „transformative capacities“as their ability to craft sets of institutions that foster individual welfare and sustainable societal robustness toward future crises. Social resilience is often represented by “individual resilience” and “resilience of teams” within an organization, which are also known as “psychological” resilience and “collective” resilience (f.e. Sommer et al., Citation2016; Raetze et al., Citation2021; Mokline & Abdallah Citation2022). Both organizational and social resilience depend, among other things, on the type and method of communication, organizational learning ability, and agility (f.e. Y. Kim, Citation2021; Orth & Schuldis, Citation2021; Yağmur & Myrvang, Citation2023).

A closer look at these studies reveals that important factors affecting organizational resilience and social resilience during crises include personality traits, developmental skills and competencies, positive attitudes, emotions, and age at the individual level. At the collective level, interactions and communication, the role of leaders and managers, and organizational learning also play a significant role (see in more detail).

Figure 1. Key factors affecting the resilience of organizations classified according to whether they are part of individual/psychological or team/collective resilience.

In this context, there are numerous studies that primarily focus on the influence of digitization (Burlacu et al., Citation2022; Fischer et al., Citation2022; Profiroiu et al., Citation2024), organizational culture and leadership (Madi Odeh et al., Citation2023; Plimmer et al., Citation2022), and crisis management (Boin & Lodge, Citation2016; Eckhard et al., Citation2021; Lenz & Eckhard, Citation2023) on the resilience of public administration organizations. The second type of studies often reveal “hidden” findings about the characteristics of individual types of public administration employees, and the third type of studies focus on the effect of communication on resilience (the exception is Roeder & Bisel, Citation2023). At the same time, there is limited and under-explored research on the relationship between risk management and change management on one side and organizational resilience on the other side (Mhlanga & Dzingirai, Citation2024).

In the presence of a specific combination of factors shaping individual and collective resilience as listed in within an organization, the concept of “collective mindfulness” can be achieved. It represents a capability that involves unique processes of idiosyncratic organizing (Weick et al., Citation2008). These processes occur through extensive social interactions and the actions of individuals within organizations, countering the tendency toward inertia, and supporting the elements of anticipation, detection, and response to unexpected events (Paul & Perwez, Citation2023; Petitta & Martínez-Córcoles, Citation2023). In other words, it is a microfoundation level capability by which organizational resources can be used to develop and sustain the collective capability of organizational resilience (Shela et al., Citation2024).

The resilience of public organizations and the potential for their investigation

As mentioned above, the large number of studies dealing with the resilience of public organizations has grown significantly in recent years. These studies often considered resilience as a “strategy” for dealing with risk and the unanticipated problems it may cause (Ansell et al., Citation2021), and their goal is to explain how administrations manage crises or extreme events (Boin et al., Citation2010; Duit, Citation2016). At the same time, strategies in the public sector can be seen as a means to improve public service performance and ultimately administer better services (Clement et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, these strategies are significantly influenced by the “context” of the given organization (Janssen & van der Voort, Citation2020). The reason is the fact that public organizations represent public policymakers and/or their implementors that do not only respond to external shocks: these policies are embedded in policy processes and dynamics subjected to path dependence, agency and power and “by attaching new (identity) rules to existing ones, the original rules that structured actors’ behaviors across the subsystem are gradually adjusted to consider emerging circumstances” (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2009, p. 16).

In this literature, resilient public administration is often defined as administration “able to adapt to the new circumstances and, in some cases, able to learn from the difficulties experienced to innovate and improve for the future” (Clement et al., Citation2023, p. 21). In this context, resilience has become a central concept when analyzing complex public governance systems (Boin et al., Citation2010 ; Boin & Lodge, Citation2016; Capano & Woo, Citation2017). The reason for the emergence of these studies is the fact that contemporary governments are increasingly facing turbulent problems that require robust governance solutions/strategies that represent “the ability of one or more decision-makers to uphold or realise a public agenda, function, or value in the face of the challenge and stress from turbulent events and processes through the flexible adaptation, agile modification, and pragmatic redirection of governance solutions” (Ansell et al., Citation2021, p. 952). According to these authors, enhancing the future capacity to respond to turbulent problems by means of designing, combining, and executing robust governance strategies requires both administrative reform and reinvention of public leaders on several dimensions.

Organizational resilience has been studied under various theoretical perspectives that emphasize different factors that influence it, which are often present in their naming—“the (tangible and intangible) resource-based view,” “the dynamic capability perspective,” “theory on organizational ambidexterity” based on the ability to pursue incremental improvements and discontinuous innovation simultaneously, “social-capital theory” focused on social relationships within and outside the organization, and “upper echelons theory” that emphasize top managers’ decisions grounded in their traits and behavior (see more closely Su & Junge, Citation2023).

Existing studies dealing with organizational resilience use different analytical approaches and tools to examine it. One of them is, for example, “The Framework of Adaptive Action” developed by Reichenbach et al. (Citation2021). It enables the exploration of the organizational capacity to adapt and learn through the interrelation of three queries: “What” happened and did not happen that was expected to happen, “Now What” to find the implications of the insights gleaned, and “So What?” to examine the meaningfulness of the experience and the lessons learned that might be useful for the future. Another approach uses the three-dimensional “Organizational Resilience Framework of Public Sector Organizations” created by Butkus et al. (Citation2024). It examines the interrelationships between “planning,” “adaptation,” and “enhanced learning,” where “planning” is acknowledged as an organizational capacity that enables preparation for unknown unknowns, “adaptation” signifies the organizational capacity to respond and adapt during or after crises, and “enhanced learning” reflects the organizational capability to absorb and leverage the new knowledge accumulated during crises. At the same time, many other analytical tools are widely used, including “The Dynamic Capabilities Framework,” “Complexity Theory,” “Organizational Learning Theory,” and, in recent years, especially the theoretical framework of the link between diversity (in culture, unit conditions, and leadership) and resilience in organizations, anticipation, coping, and adaptation capabilities (see Mhlanga & Dzingirai, Citation2024 for details).

With regard to the above definitions, forms and levels of resilience and possibilities of their investigation, in our analysis presented in this article: (1) we perceive organizational resilience as an organization’s ability to react to unusual, unpredictable and rare events so that its functioning is preserved and possibly even improved and the experience of handling past events leads to better handling of them in the future, (2) we investigate resilience both as the ability to deal with a crisis, as the process of managing it, and also as an outcome of successful crisis handling, (3) we find out whether the organizations were able to resist changes, whether they returned to the preexisting equilibria or whether they transformed and reached a new equilibrium after the crisis, (4) we use both multi-level and single-level analytical perspectives on resilience, and (5) we apply Nograšek and Vintar model of organizational transformation presented below to identify the factors that influenced the final form of organizational resilience of the two organizations examined. The reason for selecting this model is that it enables us to encompass all the factors found in the literature and mentioned above within the organization that impact its resilience, and to explore the connections between them.

Materials and methods

As already mentioned in the introduction, in this paper we try to map the modes of dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic in two public organizations in the Czech Republic from the pre-pandemic period in March 2018 to the present day to identify the final form of their organizational resilience and key factors that influenced it. The first of the two investigated organizations represents an independent administrative body and an organizational component of the state (“Deconcentrate”) with a nationwide scope responsible for activities in the area of education. It represents an administrative body and an organizational component of the state accountable for evaluating, monitoring, and controlling conditions and quality of the educational system in the Czech Republic. The second organization (“the Agency”) is a state strategic partner that provides information and communication services for the rescue service, security forces, and the public administration. Both organizations are relatively robust medium-sized and characterized by a higher degree of digitization, efficient management, and professional staff long before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the introduction, it was mentioned that both of these organizations are primarily non-bureaucratic and have a higher degree of digitization. Furthermore, a large portion of their employees possess flexible and innovative skills, which they can apply effectively. For this reason, we chose them for our research, assuming that they will be more flexible and resilient and better equipped to handle unexpected situations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic compared to purely bureaucratic organizations.

These organizations thus stand out from the vast majority of public administration organizations in the Czech Republic, which have had an unchanged form for decades, historically influenced by administrative developments in neighboring Austria and Germany. The Czech state administration is highly centralized and employs a top-down policy style in many areas. However, it is relatively fragmented, and the coordination quality is often at a medium to lower level, with limited opportunities for citizen participation. The administrative culture prioritizes justice and integrity, but places less emphasis on the public interest. The public sector is moderately open to citizens depending on the type and layer of public administration. Key values include efficiency, openness, and transparency. Management is mostly mixed or procedural, bureaucracy is relatively high in some areas and discretion is low to medium. The level of digitization of services is below the EU average. Although societal consultations are utilized at an average level in policy-making, there is better coordination and implementation as well as a higher use of evidence-based instruments, improved regulatory quality, and adherence to the rule of law. However, citizens’ trust in the government is low due to decreased transparency in government activities and a lack of control over corruption (Nemec & Špaček, Citation2018).

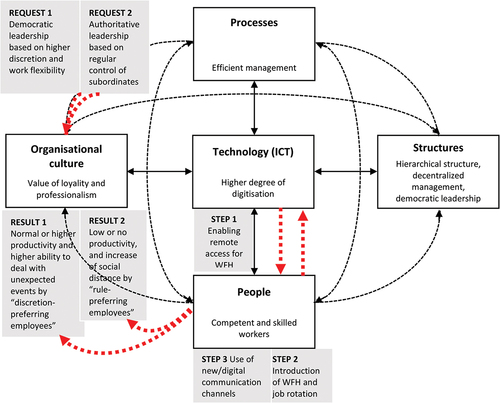

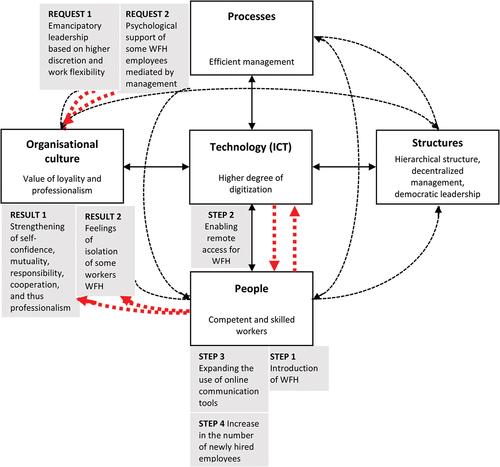

To achieve our goal, we used the Nograšek and Vintar (Citation2014) model, an upgrade of Leavitt’s (Citation1964) well-known Diamond Model, often used to analyze the influence of technologies upon organizational change. Specifically, these authors added the element of organizational culture to Leavitt’s model of an organization as a system of four elements (people, structure, tasks, and technology) and rearranged it. Moreover, they emphasized the crucial role of ICT as a trigger and driver of organizational transformation dependent on the remaining elements of the organization (see ). This assumption makes it possible to formulate the hypothesis that the greater the degree of digitization of organizational processes, the more successfully the organization will react to unusual, unpredictable and rare events (for example, by using information technologies that enable WHF). Using this model, we identify the specific factors that influenced organizations’ resulting resilience, including their extent, order, and interdependence in direction, ways, and strength. Given that both organizations were highly digitized before the pandemic, we are interested in what other key factors influenced the resilience of these organizations and whether they differed from each other.

Figure 2. The Nograšek and Vintar model presumed the central role of technology in organizational transformation.

For the needs of our research, we operationalized the Nograšek and Vintar model to the form shown in .

Figure 3. Analytical framework of monitored organizational elements and their attributes related to change.

We obtained the specific data needed to achieve our goal from three sources. First of all, from October to December 2022 we conducted 11 semi-structured deep interviews with respondents from both organizations (two top managers, seven middle managers and two public servants) based on a predefined questionnaire. The interviews were conducted following a prepared script, which allowed for gathering detailed information about the characteristics and connections of the specific factors in the Nograšek and Vintar model before, during, and after the pandemic. Individual interviews were recorded, transcribed into MS Word, and analyzed using the Atlas.ti program. The information gathered from these interviews was analyzed using the open inductive coding method. During this process, the variables mentioned earlier were identified, named, and examined for their mutual relations and connections in the interviews. We also utilized the websites of these organizations, as well as internal documents and statistics provided by their leaders. These data sources allowed us to gather crucial information about the goals of both organizations, their structures, job content of individual positions, internal and external interaction and communication processes, as well as the number and types of employees.

Results

The situation before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in the “technology” element

As already mentioned, both organizations are characterized by a higher level of digitisation many years before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, even compared to the situation in the private sector. More specifically, almost all employees in both organizations had landlines, mobile phones, laptops, and remote access through VPN, enabling connection to internal organization software and common software used for daily work. Compared to Deconcentrate, the Agency was more digitized (it owned its own certified, robust, and high-quality software system, electronic signatures, and software tools for working from any location, including from a car).

During the crisis, none of the organizations experienced major disruptions caused by moving the agendas to the digital realm, as they had been ready since before the pandemic. The move to new ways of online communication caused by the introduction of WFH for almost all employees required the increased involvement of IT staff, rapid purchase of new software, and employee training. The staff training went smoothly because most of the employees of both organizations had already been trained. The only novelty was the introduction of video conferences. IT workers had to ensure the functionality and sufficient capacity of the information technologies needed for the performance of WFH. In the case of Deconcentrate, there was a shift in the digitization of internal organizational operational processes during the crisis that completely replaced “paperwork.” But these were not caused by the pandemic, as they had already started earlier as a natural organizational development process.

An analysis of the impact of the pandemic on technology in both organizations showed that the “digital maturity” of both organizations in the pre-pandemic period minimized the long-term influence of the pandemic on technology. Perhaps the only thing that the pandemic caused in both organizations was online training of employees, the possibility of using remote access and home offices, and continued use of online video-conferencing software with external actors and WFH employees. All the above key findings are summarized in .

The situation before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in the “people” element

Both organizations are characterised by professional staff that is mostly stable in turnover: most employees are highly qualified long-term, with sufficient competencies and expertise corresponding to their work positions. All managers, as well as many ordinary officials, have relatively high levels of discretion. On the other hand, the two organizations have long-term and permanent differences in their staff structure. While Deconcentrate preferred mainly younger workers who are flexible, “create changes” and are characterised by high competence and a demand for higher discretion, in the Agency, only half the workers fit this description. The other half consists of middle-aged and older workers who prefer predefined work tasks defined by rules because of their previous experience with employment in state bureaucratic organizations.

In both organizations, job rotation for a few employees and home offices for almost all employees were introduced at the beginning of the pandemic as a response to the government’s decision to implement a lockdown (except for directors and other key workers ensuring the organization’s functioning). This circumstance led to the replacement of the current face-to-face communication between employees within the organization and between the organization and external actors through digital communication channels. The new way of working using online tools has led to workers gaining new experiences and expanding their existing digital skill sets.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the Agency has also gradually massively increased the number of newly hired employees, because it had to provide many new services. The consequence was a massive increase in work activities and the related workload of most employees compared to Deconcentrate, where workers in some workplaces, in contrast, had a light workload. Furthermore, WFH required the application of adequate managerial competencies by managers in both organizations to lead remote teams because different management methods had to be used for employees with different personality traits. Specifically, workers accustomed to physical presence at work and compliance with rules were often less productive than workers performing jobs requiring extensive discretion and innovative thinking.

In the post-pandemic period, the number and structure of employees of both organizations remained stable and unchanged. At the same time, we identified three areas where the pandemic had an impact. First, there was the development of competencies and acquisition of digital skills by employees in both organizations and managerial skills by top- and middle managers in Deconcentrate. In this context, it has been shown that applying an ”emancipatory leadership” style in the Agency, which gives workers enough autonomy to solve complex tasks, often leads to better performance. Furthermore, online communication with remote workers and external actors has been shown to be equally or even more time- and economically- effective than face-to-face meetings („Work teams have learnt to cooperate more even across different departments, for example, network infrastructure and server infrastructure workers‘). Finally, WFH remained widely used by many workers in both organizations, and in some workplaces, their use has even increased compared to the pre-pandemic period (’Workers have learnt to work from home, use all communication technologies, and I think there is nothing that can catch them by surprise”). All the key information is presented in .

The situation before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in the “processes” element

In the period before the COVID-19 pandemic, the regulation of processes within both organizations took place centrally based on the decisions of the headquarters and the heads of organizational units in accordance with laws, internal regulations, and organizational rules. Key activities within the organization were secured through face-to-face meetings of top and middle-level managers, which were often of long duration. Middle-level managers subsequently communicated with their subordinate employees through personal meetings and e-mail communication. In the Agency’s workplaces focused on IT development, lower-level managers had significant autonomy in decision-making, control and management of processes compared to Deconcentrate.

At the beginning of the pandemic, both organizations faced the challenge of responding appropriately to the government’s declaration of a state of emergency and a curfew. Their top management responded to this request by introducing a mandatory home office for almost all employees and a remote communication system for internal employees and external actors. The only exception was a limited number of management staff who ensured normal operations, and staff from the communication and marketing department. Several employees of selected workplaces of Deconcentrate used job rotation. Information flows and information sharing were therefore moved to an online mode. At the same time, both organizations successfully ensured the testing of employees present at the workplace, the provision of masks, hand disinfectant, and workplace ionization. The activities mentioned above required the establishment of processes related to the creation of documents and measures that enabled WFH and job rotation, on the one hand, and the purchase of equipment and the organization of testing, on the other.

However, both organizations struggled with the fact that their existing crisis management plans were not well suited to dealing with a pandemic. At the same time, the organization’s management started to hold regular and frequent meetings (usually several times a day). Problems also occurred with the unexpected consequences of impersonal online communication with existing and newly acquired workers working at home-office in the Agency. In the first case, some home office workers were initially less efficient, deliberately did not use cameras, and did not perform according to their managers’ expectations (e.g., some payroll workers). In the second case, new employees who only knew each other through e-mail communication were recruited.

After the end of the pandemic, personnel meetings began to be reintroduced in both organizations, but only between top and middle management and with less frequency than before the pandemic. At the same time, hybrid meetings with internal employees and external actors were more frequently used in both organizations. This made internal organizational processes more efficient, especially in Deconcentrate, where this form of communication had not existed before the pandemic ().

The situation before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in the “structure” element

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, both organizations were characterized by a linear hierarchical structure consisting of a central organization and regional units. While the top management of the organizations used hierarchical management, subordinate workplaces used decentralised management. Matrix management was used in the Agency, which consisted of a predominantly democratic style of leadership based on partnership, which was fully in the hands of the middle- and line managers. In both organizations, many different organizational units cooperated, forming permanent networks based on flexibility and knowledge shared among workers from these workplaces.

The structure of both organizations did not cause significant problems after the pandemic and their key elements remained unchanged. While the role of the Agency management increased during the pandemic, leading to a more top-down approach to tasks, the structure and decision-making procedures in Deconcentrate remained unchanged.

It was the same even after the end of the pandemic, when no major adaptations were made in the area of organizational structure in either organization().

The situation before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in the “culture” element

From before the COVID-19 pandemic to the present, the culture of most workplaces in both organizations has been characterized by openness, loyalty, and friendliness. Employees adhere to the values of mutual trust and respect, personal responsibility and professionalism based, among other things, on relevant skills, objectivity, and impartiality. Relations with external actors are also professional. These values are found to a large extent, especially among employees in workplaces that require complex thinking and flexible task-solving.

As mentioned in the section focused on the people element, two groups of employees in the Agency have different and, to an extent, even opposite organizational values. From this perspective, the Agency is a hybrid organization in which one-half represents the nature of the state sector with a “culture of people from offices” with “tunnel vision” (we label them “rule-preferring employees”). These employees prefer hierarchical management, compliance with established rules, the structuring of work activities, and the location where they are performed. (Respondents stated that “They are not willing to solve things in a different way than they are used to,” and at the same time, “these workers are usually nice, do work as a mission, perceive a sense of importance, and need praise for doing a good job”). The second half represents a “culture of people from big corporations” with “flexible and innovative skills” (we label them “discretion-preferring employees”). These employees require democratic management, broader discretion, and flexibility concerning working conditions. Although the first group of workers is unwilling and often unable to perform sudden, uncertain, and unplanned tasks (such as those caused by a pandemic), this does not cause problems for the second group because it is often a welcome challenge for them.

During the crisis, the original cultural values promoted before the pandemic were preserved, and some of them increased in both organizations. In the Agency, there was an increase in group responsibility and togetherness, especially among employees with “flexible and innovative skills.” In Deconcentrate, there was an increase in trust due to people having to work together within and across different teams and an increase in the sense of belonging and attachment to the organization (“A new team was formed, its members got to know each other, there was a strengthening of mutual trust associated with knowing one’s own limits and the ability to rely on other workers in the department”).

However, three types of problems occurred during the pandemic. The first was the frequent complaints of Deconcentrate employees about the fact that some workers at WFH worked little or not at all, and some even stopped communicating with their superiors (“Some employees confused working from home with being on vacation, making it difficult to reach, manage and control them”). This problem was quickly solved by introducing regular monitoring of the work performance of these employees and the quality of the work performed. The other two problems concerned the employees’ fear of COVID-19 infection and the feelings of isolation of some WFH workers due to the absence of social contacts (which was manifested in their being less helpful and more irritable). In both cases, the management strongly supported these employees by offering professional psychological help.

The need to often quickly and effectively deal with the large shared workload of the managers and their employees of both organizations WFH through online communication channels led to several positive and negative impacts that persisted after the end of the pandemic. These impacts specifically relate (1) to the improvement of interpersonal communication between workers in the same workplace and across different workplaces; (2) to the strengthening of their mutual trust, respect, importance of togetherness and corporate identity; (3) to employees’ willingness to continue using ICT, and (4) to the alienation of some employees who avoid others and show little interest in informal communication with them. The positives mentioned above tested employees’ abilities to deal with unexpected situations and strengthened their professionalism and awareness that they are able to face possible future crises. In other words, workers have become more resilient, especially those of the Agency with “flexible and innovative skills.”

In this context, it was essential to find that even in challenging situations that cannot be dealt with in advance but at the same time require a quick solution, the managers and other employees of the Agency were able to effectively solve problems and learn new ways of working in a short time (“Employees have started cooperating more, showing an increased interest in each other, and noticing each other’s efforts,” “They are now better prepared to face potential crises, as they have gained experience in handling crisis situations and have recognized the need to implement emergency mode”). At the same time, returning to face-to-face meetings led workers to realize the importance of social relationships, especially social communication between workers, which is more effective today because they can act faster and more flexibly().

Summary of main findings

From the above findings, it follows that both organizations are characterized by a higher degree of digitization, efficient management, and professional staff long before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the COVID-19 pandemic, while Deconcentrate was able to provide good quality services, the Agency was even more efficient than before the pandemic. According to the Norgašek and Vintar model, the changes occurred mainly in the elements of “people,” “culture,” and “technology” in both organizations. The element “processes” faced only temporary adaptations, and the element “structure” remained unchanged. The influence of “technology” and “people” areas on organizational “culture” can be considered an essential process. In this context, many interviews showed the strengthening of employees’ self-confidence, mutuality, responsibility, cooperation, and thus their common value of professionalism due to their higher ability to perform tasks successfully in an uncertain environment. This experience strengthened the ability of workers to deal with unexpected situations flexibly and thus face possible future crises.

Both organizations’ individual, successive and mutually similar responses to the COVID-19 pandemic are illustrated in detail in below.

Conclusion

Our analysis shows that both organizations examined are characterized by resilience of the “bounce forward” type. While Deconcentrate has demonstrated the ability to function smoothly during and after the pandemic, the Agency has even seen an increase in the productivity of their employees due to the rise in work agendas during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic contributed to an increase in IT security and the acceleration of the digitization process within the organization. But these were already at a high level in both organizations several years before the pandemic. This is because both types of organizations have historically pursued agendas that require a high degree of digitization. Although half of the agency’s agendas are bureaucratic and are carried out by employees who prefer following the rules, the other half requires innovative types of employees who prefer having more discretion. The hypothesis formulated in the methodological part, which claims that the greater the degree of digitization of organizational processes, the more successfully the organization will react to unexpected and uncertain events, proved valid. We have thus confirmed the findings of many previous studies conducted, especially for private sector organizations, that digital maturity significantly increases organizational resilience (e.g., Forliano et al., Citation2023; Rotem & Fisher, Citation2022).

At the same time, digital technologies were not the only key factor that contributed to the ability of both organizations to function smoothly during the pandemic, as e.g., Nograšek and Vintar (Citation2014) or Clement et al. (Citation2023) assume. We specifically identified five other key factors that contributed to the successful functioning of both organizations and thus supported their ultimate resilience, which previous studies have already confirmed (we refer to the individual factors mentioned below).

The first factor is “organizational management” both focused on the recruitment and employment of exclusively professional workers and able and willing to flexibly set management processes and working conditions that reflect the diversity of organizational workplaces and personalities of individual employees. In existing studies, this factor tends to be part of the “strategic planning” process (Butkus et al., Citation2024; Sellberg et al., Citation2018). The second, directly related factor concerns “professionally educated and trained employees” for specific job positions able and willing to further train and educate themselves and fulfil their work tasks one hundred per cent (cf. Stone-Johnson & Weiner, Citation2020; Uhomoibhi et al., Citation2022). The following two factors include “decentralised management” and “leadership skills” related to the democratic and emancipatory “leadership style” of middle- and line managers based on their ability to flexibly lead/manage different types of employees (innovative “discretion-preferring employees” requiring freedom and autonomy vs bureaucratic “rule-preferring employees” requiring rules and clear order) through tools that strengthen their motivation and thus work productivity (cf. Lundqvist & Wallo, Citation2023; Madi Odeh et al., Citation2023; Rodrigues et al., Citation2022). This type of leadership is also labeled as “dynamic” (Tucker & Lam, Citation2014) or “professional development” (Grøn et al., Citation2019). In the last case, it is “organizational culture” characterized by the ability and willingness of employees to share information and experience, support each other and cooperate in solving both daily expected and new and unexpected tasks, events and problems through mutually effective communication (cf. Bui et al., Citation2019; Sapta et al., Citation2021).

Our research also shows that, although many public administration organizations may function in a purely bureaucratic manner, having adaptable and innovative employees with high individual resilience is essential. These employees are highly capable of being socially resilient, especially when working together as a collective.

The findings above confirmed the assumption of the theoretical resilience model proposed by Buktus et al. (Citation2024), which assumes mutual relations between planning, adaptation, and enhanced learning. Experience of employees with unexpected and uncertain events and crises and the need to adapt to them namely leads to the acquisition of new knowledge and skills that can be used for planning solutions to potential situations of this nature in the future. Our findings thus show that it is crucial to pay attention to and develop all the factors mentioned above to increase the organizational resilience (not only) of public organizations and thus increase the probability of their successful handling of various unusual, unpredictable and rare events in the future. This finding also concerns the need to examine how the diversity within an organization, including both observable and unobservable heterogeneity of its members, impacts the development of resilience in organizations, as highlighted by Duchek et al. (Citation2020).

In this context, we acknowledge that our research was conducted on only two case studies with a limited number of employees. Therefore, we believe that future research should be more comprehensive. Specifically, we recommend conducting more in-depth investigations, especially focusing on the influence of organizational culture, particularly the concept of “collective mindfulness” mentioned in the literature review section, in a wider range of public administration organizations and the various personality types of public administration workers on its resilience. It is important to compare these factors carefully, as very few studies have explored this area so far (for example, Sakikawa, Citation2022; Zhu & Li, Citation2021). Additionally, it would be beneficial to conduct similar research in different types of state organizations and compare the results thoroughly.

Ethics approval

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alam, M. (2020). Organizational processes and COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for job design. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 16(4), 599–606. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-08-2020-0121

- Ansell, C., Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic as a game changer for public administration and leadership? The need for robust governance responses to turbulent problems. Public Management Review, 23(7), 949–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1820272

- Bartuseviciene, I., Butkus, M., & Schiuma, G. (2022). Modelling organizational resilience structure: Insights to assess resilience integrating bounce-back and bounce-forward. European Journal of Innovation Management, 27(1), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-04-2022-0180

- Boin, A., Comfort, L., & Demchak, C. (2010). The rise of resilience. In L. Comfort, A. Boin, & C. Demchak (Eds.), Designing resilience: Preparing for extreme events (pp. 1–12). University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Boin, A., & Lodge, M. (2016). Designing resilient institutions for transboundary crisis management: A time for public administration. Public Administration, 94(2), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12264

- Boin, A., Michel, J. G., & van Eeten. (2013). The resilient organization. Public Management Review, 15(3), 429–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.769856

- Bui, H., Chau, V. S., Degl’innocenti, M., Leone, L., & Vicentini, F. (2019). The resilient organization: A meta‐analysis of the effect of communication on team diversity and team performance. Applied Psychology, 68(4), 621–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12203

- Burlacu, S., Pargaru, I., Iacob, O. C., & Gombos, S. P. (2022). Digital public administration and the perspectives of sustainable development in Romania. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 11(4), 230–230. https://doi.org/10.14207/ejsd.2022.v11n4p230

- Butkus, M., Schiuma, G., Bartuševičienė, I., Rakauskiene, O. G., Volodzkiene, L., & Dargenyte-Kacileviciene, L. (2023). The impact of organizational resilience on the quality of public services: Application of structural equation modelling. Equilibrium Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy, 18(2), 461–489. https://doi.org/10.24136/eq.2023.014

- Butkus, M., Schiuma, G., Bartuseviciene, I., Volodzkiene, L., Rakauskiene, O. G., & Dargenyte-Kacileviciene, L. (2024). Modelling organizational resilience of public sector organizations to navigate complexity: Empirical insights from Lithuania. Journal of Economic Interaction and Coordination, 19(2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11403-023-00403-x

- Capano, G., & Woo, J. J. (2017). Resilience and robustness in policy design: A critical appraisal. Policy Sciences, 50(3), 399–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-016-9273-x

- Chelleri, L., & Baravikova, A. (2021). Understandings of urban resilience meanings and principles across Europe. Cities, 108, 102985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102985

- Clement, J., Esposito, G., & Crutzen, N. (2023). Municipal pathways in response to COVID-19: A strategic management perspective on local public administration resilience. Administration and Society, 55(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/00953997221100382

- Duchek, S., Raetze, S., & Scheuch, I. (2020). The role of diversity in organizational resilience: A theoretical framework. Business Research, 13(2), 387–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-019-0084-8

- Duit, A. (2016). Resilience thinking: Lessons for public administration. The Public, 94(2), 364–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12182

- Eckhard, S., Lenz, A., Seibel, W., Roth, F., & Fatke, M. (2021). Latent hybridity in administrative crisis management: The German refugee crisis of 2015/16. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 31(2), 416–433. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muaa039

- Fischer, V., Siegel, J., Proeller, I., & Drathschmidt, N. (2022). Resilience through digitalisation: How individual and organizational resources affect public employees working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Management Review, 25(4), 808–835. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2022.2037014

- Forliano, C., Orlandi, L. B., Zardini, A., & Rossignoli, C. (2023). Technological orientation and organizational resilience to COVID-19: The mediating role of strategy’s digital maturity. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 188, 122288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122288

- Grøn, C. H., Bro, L. L., & Andersen, L. B. (2019). Public managers’ leadership identity: Concept, causes, and consequences. Public Management Review, 22(11), 1696–1716. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1645875

- Janssen, M., & van der Voort, H. (2020). Agile and adaptive governance in crisis response: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Information Management, 55, 102180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102180

- Keck, M., & Sakdapolrak, P. (2013). What is social resilience? Lessons learned and ways forward. ERDKUNDE, 67(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.2013.01.02

- Kim, T., Mullins, L. B., & Yoon, T. (2021). Supervision of telework: A key to organizational performance. The American Review of Public Administration, 51(4), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074021992058

- Kim, Y. (2021). Building organizational resilience through strategic internal communication and organization–employee relationships. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 49(5), 589–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2021.1910856

- Leavitt, H. J. (1964). Applied organization change in industry: Structural, technical, and human approaches. In S. Cooper & H. J. Leavitt. & K. Shelly (Eds.), New perspectives in organizational research (pp. 55–71). Wiley.

- Lenz, A., & Eckhard, S. (2023). Conceptualizing and explaining flexibility in administrative crisis management: A cross-district analysis in Germany. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 33(3), 485–497. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muac038

- Linnenluecke, M., & Griffiths, A. (2010). Beyond adaptation: Resilience for business in light of climate change and weather extremes. Business and Society, 49(3), 477–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650310368814

- Lundqvist, D., & Wallo, A. (2023). Leadership and employee well-being and work performance when working from home: A systematic literature review. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.16993/sjwop.199

- MacKinnon, D., & Derickson, K. D. (2013). From resilience to resourcefulness: A critique of resilience policy and activism. Progress in Human Geography, 37(2), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512454775

- Madi Odeh, R. B., Obeidat, B. Y., Jaradat, M. O., Masa’deh, R. E., & Alshurideh, M. T. (2023). The transformational leadership role in achieving organizational resilience through adaptive cultures: The case of Dubai service sector. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 72(2), 440–468. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-02-2021-0093

- Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (Eds.). (2009). Explaining institutional change: Ambiguity, agency, and power. Cambridge University Press.

- Meerow, S., Newell, J. P., & Stults, M. (2016). Defining urban resilience: A review. Landscape and Urban Planning, 147, 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.11.011

- Mhlanga, D., & Dzingirai, M. (2024). Bibliometric study on organizational resilience: Trends and future research agenda. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 9(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-024-00098-8

- Miceli, A., Hagen, B., Riccardi, M. P., Sotti, F., & Settembre-Blundo, D. (2021). Thriving, not just surviving in changing times: How sustainability, agility and digitalization intertwine with organizational resilience. Sustainability, 13(4), 2052. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042052

- Mihotić, L., Raynard, M., & Sinčić Ćorić, D. (2023). Bouncing forward or bouncing back? How family firms enact resilience in times of crisis. Journal of Family Business Management, 13(1), 68–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-03-2022-0047

- Mokline, B., & Ben Abdallah, M. A. (2022). The mechanisms of collective resilience in a crisis context: The case of the ‘COVID-19’ crisis. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 23(1), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-021-00293-7

- Monternel, B., Kilag, O. K., & Restauro, G. (2023). Crisis response and employee engagement: The dynamics of organizational resilience with fink’s model. Excellencia: International Multi-Disciplinary Journal of Education (2994-9521), 1(5), 279–291. https://multijournals.org/index.php/excellencia-imje/article/view/58

- Nemec, J., & Špaček, D. (2018). Public administration characteristics and performance in EU28: The Czech Republic. European Commission.

- Nograšek, J., & Vintar, M. (2014). E-government and organizational transformation of government: Black box revisited? Government Information Quarterly, 31(1), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.07.006

- Orth, D., & Schuldis, P. M. (2021). Organizational learning and unlearning capabilities for resilience during COVID-19. The Learning Organization, 28(6), 509–522. https://doi.org/10.1108/TLO-07-2020-0130

- Paeffgen, T. (2023). Organizational resilience during COVID-19 times: A bibliometric literature review. Sustainability, 15(1), 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010367

- Paul, G. R., & Perwez, S. K. (2023). Mindful organizations: A bibliometric study to provide insights into the interplay between mindfulness and psychological capital in the workplace. International Journal of Professional Business Review: International Journal of Professional Business Review, 8(3), 12. https://doi.org/10.26668/businessreview/2023.v8i3.1367

- Petitta, L., & Martínez-Córcoles, M. (2023). A conceptual model of mindful organizing for effective safety and crisis management. The role of organizational culture. Current Psychology, 42(29), 25773–25792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03702-x

- Plimmer, G., Berman, E. M., Malinen, S., Franken, E., Naswall, K., Kuntz, J., & Löfgren, K. (2022). Resilience in public sector managers. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 42(2), 338–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X20985105

- Profiroiu, C. M., Negoiță, C. I., & Costea, A. V. (2024). Digitalization of public administration in EU member states in times of crisis: The contributions of the national recovery and resilience plans. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 90(2), 336–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/00208523231177554

- Raetze, S., Duchek, S., Maynard, M. T., & Kirkman, B. L. (2021). Resilience in organizations: An integrative multilevel review and editorial introduction. Group & Organization Management, 46(4), 607–656. https://doi.org/10.1177/10596011211032129

- Raetze, S., Duchek, S., Maynard, M. T., & Wohlgemuth, M. (2022). Resilience in organization-related research: An integrative conceptual review across disciplines and levels of analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(6), 867–897. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000952

- Rajala, T., & Jalonen, H. (2022). Stress tests for public service resilience: Introducing the possible-worlds thinking. Public Management Review, 25(4), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2022.2048686

- Reichenbach, R., Lynn, J., & Heeg J. (2021). Learning amid disruption: Bouncing forward into a changed world. The Foundation Review, 13(3). https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1577

- Rodrigues, E. A., Rampasso, I. S., Pavan Serafim, M., Filho, W. L., & Anholon, R. (2022). Difficulties experienced by managers in the coordination of teams working from home: An exploratory study considering the COVID-19 pandemic. Information Technology & People, 36(5), 1870–1893. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-01-2021-0034

- Roeder, A. C., & Bisel, R. S. (2023). Managing disruption(s) at work: A longitudinal study of communicative resilience and high-reliability organizing. Communication Monographs, 91(1), 56–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2023.2242918

- Rotem, D., & Fisher, E. (2022). The digital maturity as a predictor of organizational resilience during a severe crisis. Business and Economic Research, 12(4), 143–167. https://doi.org/10.5296/ber.v12i4.20507

- Sakikawa, T. (2022). Organizational resilience and organizational culture. Journal of Strategic Management Studies, 13(2), 89–101. https://doi.org/10.24760/iasme.13.2_89

- Sapta, I., Muafi, M., & Setini, N. M. (2021). The role of technology, organizational culture, and job satisfaction in improving employee performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics & Business, 8(1), 495–505. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no1.495

- Scheibe, S., De Bloom, J., & Modderman, T. (2022). Resilience during crisis and the role of age: Involuntary telework during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031762

- Sellberg, M. M., Ryan, P., Borgström, S. T., Norström, A. V., & Peterson, G. D. (2018). From resilience thinking to resilience planning: Lessons from practice. Journal of Environmental Management, 217, 906–918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.04.012

- Shela, V., Danks, N. P., Ramayah, T., & Ahmad, N. H. (2024). An application of the COA framework: Building a sound foundation for organizational resilience. Journal of Business Research, 179, 114702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.114702

- Shen, Y., Cheng, Y., & Yu, J. (2023). From recovery resilience to transformative resilience: How digital platforms reshape public service provision during and post COVID-19. Public Management Review, 25(4), 710–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2022.2033052

- Sommer, S. A., Howell, J. M., & Hadley, C. N. (2016). Keeping positive and building strength: The role of affect and team leadership in developing resilience during an organizational crisis. Group & Organization Management, 41(2), 172–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601115578027

- Stone-Johnson, C., & Weiner, J. M. (2020). Principal professionalism in the time of COVID-19. Journal of Professional Capital & Community, 5(3/4), 367–374. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-05-2020-0020

- Su, W., & Junge, S. (2023). Unlocking the recipe for organizational resilience: A review and future research directions. European Management Journal, 41(6), 1086–1105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2023.03.002

- Taleb, N. N. (2007). Black swans and the domains of statistics. The American, 61(3), 198–200. https://doi.org/10.1198/000313007X219996

- Therrien, M. C., Normandin, J. M., Paterson, S., & Pelling, M. (2021). Mapping and weaving for urban resilience implementation: A tale of two cities. Cities, 108, 102931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102931

- Tucker, E., & Lam, S. (2014). Dynamic leadership – AA leadership shortage solution. Strategic HR Review, 13(4/5), 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1108/shr-06-2014-0035

- Uhomoibhi, J., Hooper, L. O., Ghallab, S., Ross, M., & Staples, G. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on professionalism in practice and future directions. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 39(5), 480–495. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-05-2022-0098

- Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Obstfeld, D. (2008). Organizing for high reliability: Processes of collective mindfulness. Crisis Management, 3(1), 81–123.

- Wildavsky, A. (1988). Searching for safety. Transaction Publishers.

- Yağmur, Ö. B., & Myrvang, N. A. (2023). The effect of organizational agility on crisis management process and organizational resilience: Health sector example. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 96, 103955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103955

- Zhu, Y., & Li, W. (2021). Proactive personality triggers employee resilience: A dual-pathway model. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 49(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.9632