Abstract

Political representation lies at the heart of representative democracy. In order to signal their connection to the people they are representing, politicians often refer to “the people.” In this study, we focus on how politicians refer to the people and how this varies across three main platforms of communication differing in access and formality: news media, social media, and the parliament. Through an in-depth content analysis of news articles, politicians’ social media posts and parliamentary speeches (N = 1668), we examine how Dutch politicians address the people in terms of “advocacy” for the people and in “opposition” to other actors; which politicians most commonly refer to the people; which communication platforms are predominantly used for this, and whether these references to the people vary across time. We find that references to the people did not differ between election and non-election years. Yet, parties and communication platform both play important roles: references to the people manifest themselves more frequently in social media and in communication from politicians from parties on the left as well as those scoring higher on the populism scale. We also find that there is little variation in advocative references to the people, while communication that includes oppositional references is more prominent among populist actors and those positioned on the political left.

Introduction

Political representation is an inherent feature of democracy. While politicians act independently, they are trusted to do so in a way that is best for the people they represent. In order to demonstrate their responsiveness to the electorate, politicians often reference “the people”. They use appeals to the people as a communicative construction of trust and closeness to their constituents (Moffitt and Tormey Citation2014; Pitkin 1967). Some argue that such references are deliberately vague (Taggart Citation2004), acting as empty signifiers of an ambiguous mass so that everyone can feel addressed (Laclau Citation2005; Mény and Surel Citation2002).

Often, people-centric communication is equated to populist communication because references to the people are seen to be the minimal defining element of populism (de Vreese et al. Citation2018). Jagers and Walgrave’s (Citation2007) define “thin” populism as a political communication style that merely refers to the people, while “thick” populism adds the element of exclusivity and anti-elitism. Their theory informs our empirical research on the relation between appeals to the people and populism: while the “thin” conceptualization of populism serves as the base for “advocative” references to the people, as examined in this study, their “thick” conceptualization motivates our reasoning for “oppositional” references to the people.

However, referring to the people is not a communication strategy reserved for populist actors. Studies of populist communication styles frequently find politicians’ reference to the people across the political spectrum (e.g., Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007; Rooduijn Citation2014). Recent research has shown that because politicians from all parties use references to the people and public opinion—a key component of populist communication—in their communication strategies, “normal” political communication might appear populist (Strikovic et al. Citation2020). These references are originally rooted in theories of public opinion and representation where this communicative strategy is used for its effectiveness in winning over voters and shaping audiences’ perceptions: it serves as a crucial tool for persuasion. This has shown to be an especially powerful tactic in election times because it prompts support from a wide section of the population (Bos, van der Brug, and de Vreese Citation2013). Therefore, it is worthwhile to further explore how manifestations of people-centric communication such as references to the people are utilized by politicians.

In order for politicians to be able to persuade the people and voice their opinions to them, their messages have to be mediated through available communication platforms. They include the traditional media, social media, and the parliament itself (parliamentary speeches and debates are nowadays easily accessible for the ordinary voter online). Previous studies have looked at the way political communication is being adapted to fit a media logic (Altheide Citation2004; Brants and van Praag Citation2006; Mazzoleni Citation2014), the relationship between what politicians discuss in parliament and what is reported in the media (Van Aelst and Vliegenthart Citation2014), and the way social media restructured political power by providing the possibility of unmediated, direct, and personalized communication between citizens and politicians (Blumler and Gurevitch Citation2001; Engesser, Fawzi, and Larsson Citation2017; Golbeck, Grimes, and Rogers Citation2010; Kruikemeier Citation2014; Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan Citation2013). While early studies focused on traditional media and later ones on social media, the way in which references to the people take form in parliamentary debates and speeches has so far received little attention. There are also only very few studies that look at more than one platform (see Kang et al. Citation2018; Kruikemeier, Gattermann and Vliegenthart Citation2018) or considering the differences between election years and non-election years. We know from previous research that has looked into context-dependency of populist communication that different platforms influence populist communication differently (Cranmer Citation2011) and that populist communication is not restricted to populist parties (Cranmer Citation2011; Ernst, Engesser, and Esser Citation2017). We contribute to the literature by singling out appeals to the people as a communicative strategy, rather than look at populist communication as a whole, and compare the use of this across communication platforms. We provide novel insights into how politicians refer to the people, who refers most commonly to them, when those references vary, and which communication platforms are predominantly used for this.

Our overarching research question is as follows: How are politicians’ references to the people reflected in parliamentary speeches and debates, news media, and social media?

We consider this question in the Dutch context. Because it is a multi-party system, it provides diversity in the make-up of politicians and allows for the comparison between a greater range of party-level variables than, for example, a two-party system would. Through a three-folded content analysis of Dutch parliamentary (i.e., parliamentary speeches and debates), traditional media (i.e., related political media coverage by five major national newspapers), and social media (i.e., politicians’ Twitter and Facebook accounts) data, we investigate when and how political elites communicate about the people.

Theoretical framework

Our starting point for this study is politicians’ references to the people, which signal a responsiveness to the people and their input, communicating an acknowledgement that power is derived from the constituents (Moffitt and Tormey Citation2014; Pitkin 1967). This reflects the notion of collective correspondence in political representation, wherein the parliament as a whole is seen as representing the electorate (and their opinions and needs) as a whole (Dalton Citation2013).

Politicians making references to the people is by no means a new phenomenon. More recently, this communication style has re-surfaced in populist communication, where the communicative construction of the people is “at the very core, the minimal defining element” (de Vreese et al. Citation2018, 427). In the populist communication framework, the homogenous in-group of the people is seen as pure and ordinary (Canovan Citation1999; Mudde Citation2004). What helps set it apart from politicians merely addressing the wider electorate is that populist rhetoric also creates antagonism between the people and other groups. Jagers and Walgrave’s (Citation2007) distinction between a “thin” and a “thick” populism as a communication style is a helpful here. The “thin” conceptualization refers to a political communication style that merely refers to the people; the “thick” conceptualization adds content that is explicitly anti-elitist and exclusionary in nature (Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007). Opposed to the pure and hardworking people are other out-groups such as the corrupt elites (Mudde Citation2004; Taggart Citation2004) whose privilege detaches them from the ordinary people (Abts and Rummens Citation2007). They include political as well as economic elites, corporations, and the media (Canovan Citation1999; Hameleers Citation2018; Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007; Taggart Citation2000; Zaccaria Citation2018). The people are also commonly pitted against supposed outsiders within their own strata of society, such as immigrants and ethnic minorities (Hameleers Citation2018; Schmuck, Matthes, and Boomgaarden Citation2016).

In further examining political representation, we loosely follow this “thin” and “thick” approach to explore how politicians refer to the people in their communication: primarily, we examine what Jagers and Walgrave (Citation2007) call “thin” populism—advocative references made to the people; secondarily, we also explore “thick” populism by scrutinizing whether the people are put in opposition with the (political) elites or pitted against outsiders. While we do not strictly adhere to the “thin” and “thick” populism categories of Jagers and Walgrave (Citation2007), we do take on their rationale for distinguishing between the two gradations of references to the people and adapt it to a more general communication frame. Specifically, we examine two aspects of communications that carry references to the people—advocative references to the people (pro-people), and oppositional references to the people (in addition to being pro-people, pit the people against elites or other actors).

While other scholars examine solely the presence of references to the people in political communication (e.g., Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007; Rooduijn Citation2014), as mentioned above, we first and foremost look for advocative references to the people. When speaking on behalf of (and in their efforts to connect with) the people, it is favorable for politicians across the political spectrum to put the people in a positive light in order to win over the people’s confidence—and ultimately their votes. This is also the case for oppositional references to the people, where pitting the people against out-groups positions politicians on the side of the people. References to the people and attacks against elites are known to lead to more political engagement (Hameleers et al. Citation2018), more political cynicism (Rooduijn et al. Citation2017), and affect vote intention (Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart Citation2007).

We are mindful that appeals to the people in and of themselves are not restricted to the populist domain. Since having a genuine understanding of their constituents’ needs is essential for representative democracy, politicians across the political spectrum might strive to portray themselves as belonging to the people (Rooduijn, De Lange, and Van der Brug Citation2014; Strikovic et al. Citation2020; Zulianello, Albertini and Ceccobelli Citation2018). Consequently, these communication strategies are used by politicians across the political spectrum (Strikovic et al. Citation2020). Against this backdrop of general understanding, we examine at a more granular level to the politicians’ use of advocative and oppositional references to the people.

RQ1: How are advocative and oppositional references to the people manifested on media platforms?

Communication platforms

Media are an important factor in the success of political parties (Esser, Stępińska, and Hopmann Citation2016; Krämer Citation2014). There is evidence that politicians across all parties feel the pressure to cater to the media’s needs (Mazzoleni Citation2014; Strikovic et al. Citation2020). While traditional media have served as the connectors between politicians and the people for decades (Esser, Stępińska, and Hopmann Citation2016), social media changed the dynamics by providing the possibility of unmediated, direct, and personalized communication between citizens and politicians (Engesser, Fawzi, and Larsson Citation2017). Within this broader context, parliamentary debates are also affected by the media and in turn affect the media (Van Aelst and Vliegenthart Citation2014; Walgrave, Soroka, and Nuytemans Citation2007). For example, politicians know that a strong statement in a parliamentary debate could gain traction outside of the institutional realm. In effect, even though parliamentary speeches are not often streamed or watched in full, politicians are aware of the potential attention their parliamentary speech might attract from the media.Footnote1

These three communication platforms—traditional media, social media, and the parliament—provide varying degrees of formality and access to the people, allowing for an interesting comparative study. In earlier comparative studies, Newhagen and Nass (Citation1989) found that respondents evaluate the credibility of messages on different platforms according to criteria specific to them, and Cranmer (Citation2011) found that populist communication varies with the level of publicity of a platform—it tends to be more prominent on public platforms.

Communication through social media is direct, without the gatekeeping processes of traditional media (e.g., Shoemaker et al. Citation2001; Soroka Citation2012). Correspondingly, politicians acknowledge using social media, which unlike traditional media and the parliament are facilitative of reciprocity, for feeling the pulse of the nation and as a source for feedback, suggestions, and ideas from the citizens (Coleman Citation2005; Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan Citation2013; Strikovic et al. Citation2020). Consequently, they are used by politicians to invoke the people directly. We therefore hypothesize that, when addressing the people in the most direct way, politicians will use social media in a strategic way such that advocative references either alone or combined with oppositional references are more likely to appear on their social media than in traditional news media or their parliamentary speeches.

H1: People-centric communication, in terms of both (H1a) advocative and (H1b) oppositional references to the people, will be higher on social media than in traditional news media and parliamentary speeches.

Actors

While some researchers (Bos and Brants Citation2014; Rooduijn Citation2014) have found no empirical support for the claim that populist communication is being used by all politicians, other researchers have found that politicians across the ideological spectrum engage in people-centric communication (Ernst, Engesser, and Esser Citation2017; Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007; Strikovic et al. Citation2020). In this context, even non-populist politicians may refer to the people to demonstrate their closeness to citizens. The effectiveness this communication strategy may prompted politicians from all parties to utilize them (Rooduijn, De Lange, and Van der Brug Citation2014; Zulianello, Albertini, and Ceccobelli Citation2018).

Since references to the people are still anchored in the tradition of populist communication, politicians from populist parties have more ownership of them. When asked to reflect on the use of the term “the people” in political communication, politicians themselves are quick to steer the conversation toward populism, without being prompted to (Strikovic et al. Citation2020). We therefore hypothesize that we are more likely to find this type of communication within populist parties than those that are not.

H2: The more populist a politician, the more likely (s)he is to engage in communication that refers to the people in terms of both (H2a) advocative and (H2b) oppositional references to the people.

Further, communication referring to the people can point to a vertical divide—between elites and ordinary people—or horizontal divide—between groups of ordinary people.

In a country-level study in Switzerland, Cranmer (Citation2011) found that left-leaning parties are more likely to use advocative references, which may be due to the left’s emancipatory ideals. Correspondingly, they also distance the people from power structures created by corporations, globalization, and unregulated financial markets. Specifically, left-wing populists traditionally put elites, such as the “extreme” rich minority, CEOs of large corporations, or banks (Hameleers and Vliegenthart Citation2020) in opposition to the ordinary people. In this case, communication referring to the people points to the vertical divide (e.g., Canovan Citation1999; Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2017)—between the powerful elite at the (economic) top and the deprived people at the bottom.

Alternatively, communication referring to the people could point to the horizontal divide. This type of communication is associated with the populist right, in that the people are put in opposition to the supposed outsiders such as immigrants, minorities, and welfare-state profiteers (Hameleers Citation2018). Some argue, however, that right-wing parties, not unlike the left, are also critical of any type of elites: political, legal, media, and cultural (Ernst, Engesser, and Esser Citation2017).

The theory of exclusionary and inclusionary populism (Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2012) provides another lens for developing a nuanced understanding of the differences between the left and right: while the left has an inclusionary and emancipatory view of the people, the right has a limited view of the people, including only the country’s “own people”, who are given priority over outsiders such as immigrants (Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2013). While these exclusionary criteria of the right are based on cultural elements, radical right-wing populist rhetoric also excludes elite actors, conceptualizing the people as “everyone but the elite” (Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2013). Hence, there is no clear agreement on how left and right populist rhetoric differs substantially in its use of oppositional references to specific other actors. Based on the above, we ask:

RQ2: How is people-centric communication containing (a) advocative references to the people and (b) oppositional references to other actors utilized differently by left-wing and right-wing politicians?

Time

References to the people can be seen as a cue to public opinion (Lewis, Inthorn, and Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2005). If public opinion is the people’s input in political decision making (Abts and Rummens Citation2007), it can be used as a measure of the people’s will and consent. This is important to consider with regards to the effectiveness of these cues and what that means for those who listen to them. Gaining electoral support is especially important in the run-up to elections. Since mere references to the people can be used strategically to generate support from a wide part of the population (Bos, van Der Brug, and de Vreese Citation2013), and these references stress the sovereignty of the popular will (Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007), we predict the following:

H3: Overall, the frequency of communication strategies aligned with people-centrism in terms of both (H3a) advocative and (H3b) oppositional references to the people is higher in election years than in non-election years.

Methodology

We conducted a content analysis of newspaper articles in five major Dutch newspapers that included a reference to the people and political parties. They were selected on the basis of two criteria: (1) they feature a direct quote from a current or former Dutch politician, and (2) the featured quote includes a reference to the people. The politician could be directly addressing the people, talking about the people, or identifying him/herself with the people.

The search was conducted in Spring 2019 using a search string in LexisNexis that included all major Dutch political party names, names of prominent politicians (in case they are cited without their affiliate party), and various terms for the people, such as “ordinary people”, “hardworking folk,” and “voters”Footnote2. It covered the last four years, February 7, 2014–March 3, 2019. It yielded 494 relevant articles in five of the most widely read Dutch newspapers: Algemeen Dagblad (N = 155 articles), Trouw (N = 132 articles), NRC Handelsblad (N = 82 articles), De Telegraaf (N = 72 articles), and de Volkskrant (N = 55 articles). Proceedings in the online parliamentary database were searched using similar keywords (e.g., “people”, “citizens”, “folk”) over a four-year period (January 14, 2014–June 12, 2019). This yielded over 3000 results. Every fourth result was downloaded and presented to the coders to determine whether it was suitable. This, in turn, yielded 7 parliamentary speeches, 68 questions, and 561 debates. For social media, relevant posts from Twitter (N = 440 tweets between October 26, 2017 and April 21, 2019) and Facebook (N = 173 posts between July 2, 2016 and January 31, 2019) were collected from politicians’ social media pages. Limitations in the data scraping tool limited the collection of Twitter data to a period of only three years. The design of the script allowed for the scraping of the most recent 3000 tweets, which in practice accounted for the time period between October 2017 and April 2019. Facebook data were collected and analyzed manually, resulting in the coverage of the same time frame to the Twitter data. This resulted in a shorter time frame for social media data than parliamentary data. A robustness check was run with a smaller sample of parliamentary data, corresponding to the time frame of the social media data, and the results remained similar. Coders manually searched all politicians’ social media pages and selected posts that included references to the people.

Two coders who were Dutch native speakers conducted the coding. The unit of analysis and coding was a single quote from a politician or representative of a political party, marked by quotation marks in news articles or up to one paragraph of uninterrupted speaking in parliamentary materials. For social media, posts from politicians on Facebook and Twitter were coded if they contained direct references to the people. This included only original content posted by the politicians and excluded images, re-tweets, shared posts, and quoted content that was not created by the owner of the social media profile. Intercoder reliability between the coders and the researcher was high for both dependent variables (Krippendorff’s alpha coefficient = 0.71 for the variable “Advocacy”; α = 0.81 for “Opposition”).

Measures

Independent variables

Descriptive variables included the date of the item and the politician’s name or affiliated party. For our independent variables, left-right alignment and populism scale of the political parties that politicians belonged to, we relied on the 2017 Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Polk et al. Citation2017). In the survey, left/right positioning was measured on a 10-point scale (0 = extreme left, 10 = extreme right); populism was also coded on a 10-point scale, indicating whether politicians preferred elected office holders to make important decisions (0) or whether those decisions should be made by “the people” (10). We also created a dummy variable that indicated whether the specific statement was from the 2017 election year (1) or not (0).

Dependent variables

We coded items for the presence of advocative references to the people (Advocacy) by asking whether overall, the content of the statement is positive toward the people and coded neutral references as “0”. We coded our second dependent variable (Opposition) by asking whether any other actors are mentioned and, if so, whether the content is oppositional toward the actors, i.e., whether the people are put in opposition to these actors.

The variable indicating opposition to the people was computed using two variables: (1) whether the people are put in opposition with other actors (immigrants, elites, corporations and politicians) and/or (2) whether negative sentiment is used toward those actors.

Results

In this section, we will proceed as follows: First, we will make overall qualitative observations about the data. We will draw on politicians’ quotes to illustrate how our dependent variables manifest themselves on our the three communication platforms we studied. We will then look at main effects across all communication forms, as well as differences between news media, parliamentary data, and social media.

To indicate the effect size, we will report odds ratios. This is particularly useful when describing relationships between binary variables. Odds ratios in a logistic regression indicate the ratio of the odds of the dependent variable being present as a result of variance in the independent variable. An odds ratio value greater than one (OR > 1) indicates an increased likelihood of the dependent variable being present, while the opposite is true for odds ratios less than one (OR < 1). Effect sizes in odds ratios are interpreted as probabilities of the dependent variable being present with the independent variable. If the dependent variable increases by one (1), the odds ratio indicates by how much the probability of the dependent variable being present increases.

General observations

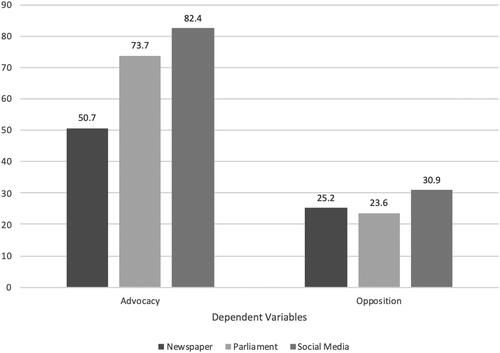

shows descriptive statistics for the three communication platforms and the dependent variables examined in this study. While most of the data did include references to the people, these references were not always explicitly positive. Out of all items that mention the people, people were referenced in an advocative manner and/or put in opposition with other actors as indicated in .

Figure 1. Percentage of items in news, parliamentary and social media data containing the relevant dependent variables.

Note. Total sample of items that refer to the people: N = 1668.

Our first research question addressed how statements that are classified as “advocacy” or “opposition” are manifested on communication platforms. In order to answer this question, we have selected some samples from our data to illustrate these indicators with.

Advocative references to the people were classified by politicians using positive sentiment when speaking to or about the people. Politicians who refer to the people this way make statements that suggest the people are good in some way, suggesting that they work hard and have good intentions.

“The People are everyone who works hard, wants to work hard or ever has ever worked hard.” (Arno Rutte, VVD)

“The people are those that work really hard and are decent tax payers.” (Omtzigt, CDA)

“The people are the ordinary men and women.” (Geert Wilders, PVV)

In addition, they might add that the people have been wronged in some way and that this has to be rectified (presumably through voting for them):

“The hardworking Dutch people are the victims of fraudulent parties.” (Helma Nepperus, VVD)

“While entrepreneurs and employees in the Netherlands created a lot of prosperity in 2018, the vast majority of this went to investors and shareholders … not to the workers, the hardworking men and women in the workplace.” (Mahir Alkaya, SP)

“Where politicians and climate gurus think they can save the globe, millions of ordinary Dutch people do not even save the end of the month financially.” (Geert Wilders, PVV)

“Rutte’s empty promises have sparked cynicism. The hard-working Dutch people feel betrayed.” (Pieter Heerma, CDA)

“If you thought that [the FVD] cares about the ordinary men and women: this infamous case of mass terminations in the Reagan era is what they view as the ideal [link to Reagan dismissing 11.000 striking workers]!” (Zihini Ozdil, GL)

“I really wonder if hardworking Dutch people find it acceptable that their tax money is spent in this way by GroenLinks ….’ (Wybren van Haga, VVD)

While it seems that there is agreement on the people being pious, hard-working and well-deserving citizens that need protection from the ill-intent of other parties and politicians, we examined under what circumstances this communication varied.

Hypotheses

To test our first two hypotheses, which posited that references to the people in terms of (H1a) advocacy and (H1b) opposition will be higher in social media than in traditional news media and parliamentary data, we first looked at the percentages of communication that entailed advocative references to the people across all three communication platforms. shows that social media displays the highest percentage of positive references to the people: 82.4% of all people-centric communication referred to the people in an advocative way. We used chi-square tests to determine that the differences in advocative references to the people between social media and both traditional media and parliamentary data are statistically significant (X2(2, N = 1223)=95.1, p<.01). We can therefore confirm Hypothesis 1a.

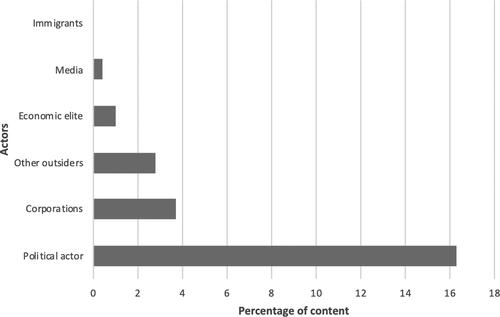

also shows that the ratio of communication pitting the people against other actors is slightly higher in social media (30.9%) than in the news (25.2%) or in parliamentary data (23.6%). These differences are statistically significant only between social media and parliamentary data (X2(2, N = 306) =15.8, p<.01), however not between social media and traditional media providing only partial support for hypothesis 1b. When examined closer, the actors that are most commonly pitted against the people are other politicians (see ).

Table 1. Parties’ mean score for left/right alignment and populism according to the 2017 Chapel Hill Expert Survey.

Hypothesis 2a and Hypothesis 2b posited that politicians who belong to populist parties are more likely to engage in communication that is indicative of both advocative and oppositional references to the people. To test these hypotheses, we ran logistic regressions with our independent variables for each of the examined dependent variables. shows main effects of the independent variables for both dependent variables aggregated for all forms of communication. Content across all forms of communication taken together tends to have a higher probability of including advocative references to the people if the politicians belong to a populist party. This confirms hypothesis 2a showing that the likelihood of politicians referencing the people in a positive way increases with their party’s score on the populism scale—at least when scores are aggregated for all three platforms . However, when looking at the three platforms separately, only one platform drives the results of the aggregated model: examining the three communication platforms separately, populist alignment relates to a higher probability of the use of advocative references to the people only for communication items that stem from parliamentary data. Within social media and news items, this correlation is not significant.

Table 2. Main effects of election year, populism, ideological positioning, and communication platform.

Moreover, higher scores of the populism scale also yield a higher probability that communication showed an opposition between the people and other actors. We can therefore confirm hypothesis 2b. These results hold for each of the separate communication platforms (see ), indicating populist parties’ higher probability of the use of oppositional references to the people on social media, newspapers, as well as within parliamentary setting. The odds ratio for social media is especially high and differs significantly from those of the parliamentary and news data. The odds ratio here is OR = 1.93, showing that as the populism score increases by one, the probability that the dependent variable (opposition) being present increases by 1.93 (or 93%). As odds of the dependent variable being present are expressed as a proportion of the odds that the dependent variable will not be present, the greater the numerical distance is from one, the greater the effect. For this particular result, the effect size is large, suggesting that the level of populism of the politicians’ party has a far greater impact on the dependent variables within social media than in the news or parliament.Footnote3

As far as advocacy within news media and social media, no significant effect of parties’ populism scores on their use of these references was present. In light of the results shown in , where both dependent variables were present mostly in social media, this indicates that while that is true for politicians across the board, the level of populism of the politicians’ party has a greater impact within the parliament.

Insignificant results for social media may be explained by the frequency of the use of advocative references to the people on them: social media may not be affected by variances in our independent variables because positive references to the people are simply the norm. Insignificant results for news media are more surprising. This might be explained by negative news biases because news consumers are more interested in and reactive to negative political news content rather than positive appeals (Soroka and McAdams Citation2015). We can observe that in general, within traditional news, the independent variables have little impact, which may point to journalistic selection procedures that are at work, here.

Our second research question asked how people-centric communication containing (a) advocative references to the people and (b) oppositional references to other actors is utilized differently by left-wing and right-wing politicians. Our data provide sufficient support to answer this question: shows that content from politicians aligned on the left tends to have a higher probability of using advocative references to the people and oppositional references to the people including other actors than politicians on the right. When we examined communication platforms separately, these results for advocacy stayed significant for parliamentary communication, while opposition was only significant on social media (see and ).

Table 3. Main effects of independent variables on positive references to the people across different communication forms (N = 1223).

Table 4. Main effects of independent variables on data containing opposition between the people and other actors across different communication forms (N = 463).

Moreover, when referencing other (elite) actors, politicians on the left most often invoke politicians. While politicians from the right also favor politicians over other actors, politicians on the left overall invoke them more often (see ). Other notable differences lie in references to corporations and the economic elite, which are also invoked more frequently by left-wing politicians than right-wing politicians. This fittingly illustrates the horizontal/vertical divide in which left-wing politicians distance themselves and the people from the economic and powerful elite from the top (Hameleers and Vliegenthart Citation2020), while right-wing politicians reference threats from within society, such as immigrants and asylum seekers (Hameleers Citation2018; Schmuck, Matthes, and Boomgaarden Citation2016).

Figure 3. Percentage of content from left wing/right wing sources pitting the people against other actors.

Hypothesis 3a, focusing on variances in time (i.e., election year vs. non-election year), posited that the frequency of communication strategies aligned with advocative references to the people is higher in election years than in non-election years. We expected that favorable communication intended for the people would significantly increase in election years, as politicians appear more frequently and prominently in the news. Results of the logistic regression show that there is no significant difference in positive references to the people between election years and non-election years. Hence, there is no support for our hypothesis. In Hypothesis 3b, we also expected that in election years, campaigning turns negative, i.e., that politicians focus more on the opposition’s perceived failings rather than their own accomplishments or policy plans. However, there is also no support for this hypothesis in our data. Insignificant results point to interesting implications about the invocation of the people in election times. In fact, when tested for the different communication platforms separately, shows that the opposite is the case for parliamentary data, where advocative and oppositional references to the people significantly decrease in election years.

Conclusion

In this study, our aim was to provide insights into how politicians utilize three communication platforms—traditional media, social media and the parliament—to address the people and how their references to the people vary across them. In order to do so, we categorized references to the people into advocative references and oppositional references, and examined what variances in actor, platform, and time had an effect on them.

Qualitative data in our study shows that advocative references to the people often come in the form of attributions of virtuousness, loyalty, and a good work ethic. Echoing populist perceptions of the people (Canovan Citation1999; Taggart Citation2004), politicians portray the people as hardworking, well-meaning, and often falling victim to other actors. In this way they signal their advocacy and closeness to them, as if to say “I listen to you because I talk about you” (Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007, 323). The data also show that actors the politicians by far most often put in opposition to the people are other political actors. This aids the politicians in two ways: Firstly, it separates them from the pack of politicians, communicating that they are different from the rest and connected to the people in a way that other politicians are somehow not. Secondly, it signals a responsiveness to a seemingly perceived threat to the people, offering not only political representation through responsiveness, but also a solution to it.

We also found support for hypotheses (H1a and H1b) about communication platforms, indicating that communication strategies that include advocative and oppositional references to the people are indeed most likely to be displayed on social media. This may not be surprising, given that social media are free of gatekeeping restrictions, they provide direct reach to the people, and lack formal boundaries. This also has implications for the politicians’ representation of, and closeness to, the people. The interactive nature of social media suggests a mutuality to this connection: direct communication between the people and politicians is (in principle) possible and has a positive impact on the public’s political involvement and vote allocation (Kruikemeier Citation2014; Kruikemeier et al. Citation2013). Politicians who use social media and appear accessible and in touch are less likely to be perceived as disconnected than detached representatives (Coleman Citation2005).

We also hypothesized that politicians from populist parties scoring high on populism are more likely to utilize communication strategies that include advocative and oppositional references to the people (H2a and H2b) and examined the effect of politicians’ left/right alignment on their use of them (RQ2). Our key findings confirm that politicians’ populism scores are the strongest predictors of communication that include advocative and oppositional references to the people. While we did not examine these references within a populist framework, our findings raise the question whether they speak of politicians’ communications strategies or of fragmented populism (Engesser et al. Citation2017). A closer look into the findings provides a nuanced answer. Populism scores of the politicians’ party was only a predictor for advocative references to the people in parliamentary speeches. This is in line with research on the public nature of parliamentary speeches that identifies the potential reach of a large audience as a key contributing factor for the prevalence of populist communication in them (Cranmer Citation2011). One could argue that because politicians know that the stakes of parliamentary speeches are rather high, as their speeches will be disseminated by the media and have a bearing on decision making (van der Valk 2003; van Dijk 2000), their incentives to use persuasive communication strategies rooted in populist rhetoric are rather high (Cranmer Citation2011). In the Dutch context, parties also often share parliamentary speeches on social media directly, getting around their dependency on journalists to disseminate parts of the speeches. This might mean that the social media platform (and its reach) is taken into account when these speeches are written.

Another explanation for the difference in communication between populist and non-populist parties in parliamentary data could be that politicians use news and social media to communicate more strategically (i.e., utilize communication strategies that have persuasive effects, such as those rooted in populist communication), while, in parliamentary speeches references to the people are motivated by policy considerations. Hence, politicians from populist parties would be more likely to use communication tied to the ideology of their party than those from non-populist parties. However, overall and consistently, populist politicians are more likely to engage in communication that pits people against other actors, in keeping with the scholarship on “thick” populism (Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007). Further, this is in line with Engesser et al.’s (Citation2017) findings, which shows that on social media populism appears in a fragmented form, often consisting of advocacy for the people and opposition to other actors.

In answer to our second research question, our findings show that, contrary to what headlines of political coverage may suggest, it is not the extreme right-wing politicians but rather those aligned on the left of the political spectrum who engage in communication that is more likely to use advocative and oppositional references to the people. Again, these results are not consistent across all communication platforms: just as with populism scores, advocative references to the people are only significantly higher for left-wing politicians in parliamentary data. When it comes to oppositional rhetoric, the same is the case for social media. This may be explained by the left’s emphasis on the socio-economic divide between the people and other actors, meaning that attacks on the elite are preferred by left-wing politicians (Engesser et al. Citation2017). Other politicians are also folded into this category of “elites”, being portrayed as out of touch with the people. This is compatible with the ideologies of the left-wing, as they signal a closeness to the people and distance themselves from the elite political pack.

Lastly, we theorized that election years would display more frequent use of communicative strategies aligned with both advocacy and opposition (H3a and H3b). Despite our expectations, we discovered that election years had no effect on either of those communication strategies. This might be explained by the apparent ubiquity of references to the people and their opposition to others, so that even if it does increase in election years, this does not happen at a significant level. This is in line with studies that have shown that negative campaigning is highly dependent on communication platform (Walter and Vliegenthart Citation2010) and that negative campaigning overall has not increased (Walter Citation2013).

On a critical note, we would like to reflect on some limitations to this study. The first limitation is that the analyzed sample yielded a relatively small proportion of items where the dependent variable “opposition” was present. Political actors as outgroups were mentioned in around 16% of the coded items, while other actors were mentioned in less than 5%. This is important to consider, especially in light of the resulting lack of detailed analyses and insights with regards to these other actors: the data included too few cases of actors other than politicians being put in opposition with the people, we were not able to assess the circumstances around these other actors being pitted against the people. It would be beneficial to investigate these other actors more closely with a larger sample. Sufficient data might lead to more precise conclusions about how and when immigrants, the economic elite, the media and other outside actors are invoked in people-centric communication.

The lack of data about other actors leads to a second limitation. Our conceptualization of oppositional references to the people does not reflect any gradients of this variable. For the current article, it sufficed for one actor to be present. If more extensive data were available, it may be interesting to analyze this variable on a scale, assessing whether the degree of oppositional communication varies with different actors, platforms or time. It may also be insightful to examine whether these variations have different effects on the population. As discussed above, it has been argued by many scholars that left-wing politicians are prone to attack the economic elite (Hameleers and Vliegenthart Citation2020), while right-wing politicians are more likely to attack the media and political elite (Ernst et al. Citation2017; Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2013), as well as immigrants (Hameleers Citation2018; Schmuck, Matthes, and Boomgaarden Citation2016). Thus, we advise future research to look into more specific notions of “other actors” and develop different sub-hypotheses for these.

The sampling strategy is a third limitation, leaving room for further research. Firstly, only explicit, direct quotes were analyzed. News websites often have embedded videoclips as supplementary footage. This is even more so the case for social media, where images, videos, re-tweets, and shares are as much a part of communication as personal posts. Secondly, these quotes were specifically selected based on the strict criteria that they include references to the people. This specific communication element is still relatively rare, compared to the overall communication of politicians. For the scope of this article, as it analyses the variances in references to the people, sampling only quotes with references to the people was legitimate. However, it may be insightful for future research to examine the overall prevalence of this communication strategy, i.e., to embed the analyses in the larger context of political communication. While our results drew conclusions about three different platforms—social media, news media and the parliament, the data came from individual politician’s communications on them. With this comes the inherent risk of confounding actor and platform, attributing results to platform characteristics rather than personal preferences in communication style of these specific politicians. Future research could therefore track specific actors across platforms in order to disentangle whether effects are tied to the platform or whether they are actor specific—in other words, the question becomes to what extent platform (and thus context) dictates communication styles and consequently, the same actor uses different ways of communication across social media, news media, and the parliamentary setting. Adding such messages to the analysis could provide more thorough and complete insights into the ways that appeals to the people are utilized in communication strategies by politicians.

The study sheds light on how politicians refer to the people, the variation in the presence of references to the people, which actors are put in opposition with the people and how different communication platforms are used for this. We suggest that future research focuses on the effectiveness of these messages. Studies should not only investigate this on the level of populist communication as a whole, but look at its fragments individually and examine the effectiveness of different types of references to the people in political communication.

Notes

1 The parliamentary setting also allows for a comparison between messages that are explicitly intended for the public (newspapers and social media) and those that are, for the most part, internal in nature (albeit with anticipated/possible public attention).

2 For full search string, see Appendix A.

3 When we tested the effect of coalition/opposition parties on the dependent variables, the effects were significant but disappeared when the populism variable was added.

References

- Abts, K., and S. Rummens. 2007. Populism versus democracy. Political Studies 55 (2):405–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00657.x.

- Altheide, D. L. 2004. Media logic and political communication. Political Communication 21 (3):293–6. doi: 10.1080/10584600490481307.

- Blumler, J. G., and M. Gurevitch. 2001. The new media and our political communication discontents: Democratizing cyberspace. Information, Communication & Society 4 (1):1–13. doi: 10.1080/713768514.

- Boomgaarden, H. G., and R. Vliegenthart. 2007. Explaining the rise of anti-immigrant parties: The role of news media content. Electoral Studies 26 (2):404–17. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2006.10.018.

- Bos, L., and K. Brants. 2014. Populist rhetoric in politics and media: A longitudinal study of the Netherlands. European Journal of Communication 29 (6):703–19. doi: 10.1177/0267323114545709.

- Bos, L., W. van Der Brug, and C. H. de Vreese. 2013. An experimental test of the impact of style and rhetoric on the perception of right-wing populist and mainstream party leaders. Acta Politica 48 (2):192–208. doi: 10.1057/ap.2012.27.

- Brants, K., and P. Van Praag. 2006. Signs of media logic half a century of political communication in the Netherlands. Javnost – The Public 13 (1):25–40. doi: 10.1080/13183222.2006.11008905.

- Canovan, M. 1999. Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies 47 (1):2–16. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.00184.

- Coleman, S. 2005. The lonely citizen: Indirect representation in an age of networks. Political Communication 22 (2):197–214. doi: 10.1080/10584600590933197.

- Cranmer, M. 2011. Populist communication and publicity: An empirical study of contextual differences in Switzerland. Swiss Political Science Review 17 (3):286–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1662-6370.2011.02019.x.

- de Vreese, C. H., F. Esser, T. Aalberg, C. Reinemann, and J. Stanyer. 2018. Populism as an expression of political communication content and style: A new perspective. The International Journal of Press/Politics 23 (4):423–38. doi: 10.1177/1940161218790035.

- Dalton, R. J. 2013. Citizen politics: Public opinion and political parties in advanced industrial democracies. London: Sage.

- Engesser, S., N. Fawzi, and A. O. Larsson. 2017. Populist online communication: Introduction to the special issue. Information, Communication & Society 20 (9):1279–92. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328525.

- Engesser, S., N. Ernst, F. Esser, and F. Büchel. 2017. Populism and social media: How politicians spread a fragmented ideology. Information, Communication & Society 20 (8):1109–26. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2016.1207697.

- Esser, F., A. Stępińska, and D. N. Hopmann. 2016. Populism and the media: Cross-national findings and perspectives. In Populist political communication in Europe, eds. T. Aalberg, F. Esser, C. Reinemann, J. Strömbäck, and C. H. de Vreese, 365–80. New York: Routledge.

- Ernst, N., S. Engesser, and F. Esser. 2017. Bipolar populism? The use of anti-elitism and people-centrism by Swiss parties on social media. Swiss Political Science Review 23 (3):253–61. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12264.

- Golbeck, J., J. M. Grimes, and A. Rogers. 2010. Twitter use by the US Congress. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 61 (8):1612–21.

- Hameleers, M. 2018. A typology of populism: Toward a revised theoretical framework on the sender side and receiver side of communication. International Journal of Communication 12:2171–90.

- Hameleers, M., L. Bos, N. Fawzi, C. Reinemann, I. Andreadis, N. Corbu, C. Schemer, A. Schulz, T. Shaefer, T. Aalberg, et al. 2018. Start spreading the news: A comparative experiment on the effects of populist communication on political engagement in sixteen European countries. The International Journal of Press/Politics 23 (4):517–38. doi: 10.1177/1940161218786786.

- Hameleers, M., and R. Vliegenthart. 2020. The rise of a populist zeitgeist? A content analysis of populist media coverage in newspapers published between 1990 and 2017. Journalism Studies 21 (1):19–36. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2019.1620114.

- Jagers, J., and S. Walgrave. 2007. Populism as political communication style: An empirical study of political parties’ discourse in Belgium. European Journal of Political Research 46 (3):319–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x.

- Kang, T., E. F. Fowler, M. M. Franz, and T. N. Ridout. 2018. Issue consistency? Comparing television advertising, tweets, and e-mail in the 2014 senate campaigns. Political Communication 35 (1):32–49. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2017.1334729.

- Krämer, B. 2014. Media populism: A conceptual clarification and some theses on its effects. Communication Theory 24 (1):42–60. doi: 10.1111/comt.12029.

- Kruikemeier, S. 2014. How political candidates use Twitter and the impact on votes. Computers in Human Behavior 34:131–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.025.

- Kruikemeier, S., K. Gattermann, and R. Vliegenthart. 2018. Understanding the dynamics of politicians’ visibility in traditional and social media. The Information Society 34 (4):215–28. doi: 10.1080/01972243.2018.1463334.

- Kruikemeier, S., G. Van Noort, R. Vliegenthart, and C. H. De Vreese. 2013. Getting closer: The effects of personalized and interactive online political communication. European Journal of Communication 28 (1):53–66. doi: 10.1177/0267323112464837.

- Laclau, E. 2005. On populist reason. London: Verso.

- Lewis, J., S. Inthorn, and K. Wahl-Jorgensen. 2005. Citizens or consumers? What the media tell us about political participation. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press.

- Mazzoleni, G. 2014. Mediatization and political populism. In Mediatization of politics: Understandinig the transformation oof western democracries, 42–56. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mény, Y., and Y. Surel. 2002. The constitutive ambiguity of populism. In Democracies and the populist challenge, eds. F. Esser and J. Strömbäck, 1–21. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Moffitt, B., and S. Tormey. 2014. Rethinking populism: Politics, mediatisation and political style. Political Studies 62 (2):381–97. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12032.

- Mudde, C. 2004. The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition 39 (4):541–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x.

- Mudde, C., and C. R. Kaltwasser. 2012. Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or corrective for democracy? Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, C., and C. R. Kaltwasser. 2013. Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism: Comparing contemporary Europe and Latin America. Government and Opposition 48 (2):147–174.

- Mudde, C., and C. R. Kaltwasser. 2017. Populism: A very short introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Newhagen, J. E., and C. Nass. 1989. Differential criteria for evaluating credibility of newspapers and TV news. Journalism Quarterly 66 (2):277–84. doi: 10.1177/107769908906600202.

- Polk, J., J. Rovny, R. Bakker, E. Edwards, L. Hooghe, S. Jolly, J. Koedam, F. Kostelka, G. Marks, G. Schumacher, et al. 2017. Explaining the salience of anti-elitism and reducing political corruption for political parties in Europe with the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey data. Research & Politics 4 (1):205316801668691. doi: 10.1177/2053168016686915.

- Rooduijn, M. 2014. The nucleus of populism: In search of the lowest common denominator. Government and Opposition 49 (4):573–99. doi: 10.1017/gov.2013.30.

- Rooduijn, M., S. L. De Lange, and W. Van der Brug. 2014. A populist Zeitgeist? Programmatic contagion by populist parties in Western Europe. Party Politics 20 (4):563–75. doi: 10.1177/1354068811436065.

- Rooduijn, M., W. Van der Brug, S. L. De Lange, and J. Parlevliet. 2017. Persuasive populism? Estimating the effect of populist messages on political cynicism. Politics and Governance 5 (4):136–45. doi: 10.17645/pag.v5i4.1124.

- Schmuck, D., J. Matthes, and H. Boomgaarden. 2016. Candidate-Centered and Anti-Immigrant Right-Wing Populism. Aalberg, T., Esser, F. Reinemann, C., Stromback, & J. De Vreese, C. (Hrsg.) Populist political communication in Europe, 85–102.

- Shoemaker, P. J., M. Eichholz, E. Kim, and B. Wrigley. 2001. Individual and routine forces in gatekeeping. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 78 (2):233–46. doi: 10.1177/107769900107800202.

- Soroka, S. N. 2012. The gatekeeping function: Distributions of information in media and the real world. The Journal of Politics 74 (2):514–28. doi: 10.1017/S002238161100171X.

- Soroka, S. N., and S. McAdams. 2015. News, politics, and negativity. Political Communication 32 (1):1–22. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2014.881942.

- Stieglitz, S., and L. Dang-Xuan. 2013. Social media and political communication: A social media analytics framework. Social Network Analysis and Mining 3 (4):1277–91. doi: 10.1007/s13278-012-0079-3.

- Strikovic, E., T. G. L. A. van der Meer, E. van der Goot, L. Bos, and R. Vliegenthart. 2020. On behalf of the people: The use of public opinion and the perception of “the people” in political communication strategies of Dutch MPs. The International Journal of Press/Politics 25 (1):135–57. doi: 10.1177/1940161219864297.

- Taggart, P. A. 2000. Populism. Open University Press.

- Taggart, P. 2004. Populism and representative politics in contemporary Europe. Journal of Political Ideologies 9 (3):269–88. doi: 10.1080/1356931042000263528.

- Van Aelst, P., and R. Vliegenthart. 2014. Studying the tango: An analysis of parliamentary questions and press coverage in the Netherlands. Journalism Studies 15 (4):392–410.

- Walgrave, S., S. Soroka, and M. Nuytemans. 2007. The mass media’s political agenda-setting power: A longitudinal analysis of media, parliament, and government in Belgium (1993 to 2000). Comparative Political Studies 41 (6):814–836.

- Walter, A. S. 2013. Women on the battleground: Does gender condition the use of negative campaigning? Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties 23 (2):154–176.

- Walter, A. S., and R. Vliegenthart. 2010. Negative campaigning across different communication channels: Different ball games? The International Journal of Press/Politics 15 (4):441–461.

- Zaccaria, G. 2018. The People and Populism. Ratio Juris 31 (1):33–48.

- Zulianello, M., A. Albertini, and D. Ceccobelli. 2018. A populist zeitgeist? The communication strategies of Western and Latin American political leaders on Facebook. The International Journal of Press/Politics 23 (4):439–57. doi: 10.1177/1940161218783836.

Appendix A:

Search strings

Search-string for mentions of people in parliamentary data

“mensen” OR “burgers” OR “burger” OR “Nederlander” OR “Nederlanders” OR “volk” OR “electoraat” OR “stemmer” OR “stemmers”

Search-string for people-centrism in the media (LexisNexis)

gewone Nederlander! OR stille motor OR de hardwerkende burger! OR hardwerkende burgers OR de gewone burger! OR gewone burgers OR de normale Nederlander! OR de normale burger! OR normale mens* OR hardwerkende Nederlander! OR de hardwerkende belastingbetaler! OR ons eigen volk OR het gewone volk OR ons eigen land OR onze eigen cultuur OR de gewone man OR de gewone vrouw OR (Henk en Ingrid) OR (Jan met de Pet) OR de modale man OR (Jip en Janneke) OR Kiezers OR burger* OR electoraat OR stemmer* OR volk OR (Jan Modaal) AND (PvdA OR PvdD OR Partij voor de Dieren OR Partij van de Arbeid OR GroenLinks OR GL OR SGP OR ChristenUnie OR CU OR PVV OR Partij voor de Vrijheid OR VVD OR Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie OR CDA OR D66 OR Democraten 66 OR SP OR Mark Rutte OR FvD OR Geert Wilders) AND NOT SECTION (Buitenland OR Sport OR Kunst)