ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly impacted higher education (HE) globally, causing students to feel disconnected and burdened with online learning. In response, many institutions have adopted a hybrid approach to teaching and learning (T-L) to mitigate future outbreaks. However, the impact of hybrid T-L on students’ experiences remains underexplored. This study aims to investigate the impact of hybrid T-L on students’ experiences post-pandemic, including satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy, and to identify areas for pedagogical improvement. This mixed-methods study of 246 students from six HEs in Malaysia found that hybrid learning (HL) was associated with positive student experiences, high satisfaction, self-efficacy, and engagement, which was attributed to students’ efficacy with online learning during the pandemic and the flexibility afforded by HL, highlighting the need for pedagogy that supports engagement and builds resilience in the post-pandemic setting in HE. Overall, the study contributes to the literature on HL in the post-COVID era by shedding light on how students navigated the rapid educational shifts caused by the pandemic. It provides insights into how HL can be optimized for effective and engaging learning and highlights the importance of continuous professional development to ensure teachers are equipped with the necessary skills for HL.

Introduction

As we are gradually unearthing the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on higher education (HE), numerous studies are unravelling the magnitude of disruption on students, teachers, and institutions globally (Ndzinisa & Dlamini, Citation2022). Though the continuity of teaching and learning (T-L) was maintained through online learning, the sudden pivot was reported to result in students “feeling disconnected, discordant, and distracted; struggling to engage amid lost autonomy and personal stressors; experiencing academic burden and burnout; and encountering both caring and disregard from instructors” (Hensley et al., Citation2022, p. 208). Studies found psychological stress affected students’ engagement and academic performance (Chiu, Citation2022).

Post-pandemic, many HE institutions opted for hybrid T-L to mitigate any possible event of another outbreak (Ndzinisa & Dlamini, Citation2022). As with the sudden pivot to online learning during the pandemic, the hybrid approach remains underexplored within the post-pandemic setting. Though it is argued to be the panacea in the current education setting, Hybrid learning (HL) is not simply a fusing of online and face-to-face (f2f) instructions (Singh et al., Citation2021). The basic principle of hybrid T-L is that it is optimally integrated to leverage on strengths of online and f2f, integrated into a distinctive learning experience congruent with the circumstances and planned educational outcomes (Raes, Citation2022). This is based on the premise that when the two environments are thoughtfully integrated, the educational possibilities are logically multiplied (Zhao et al., Citation2022).

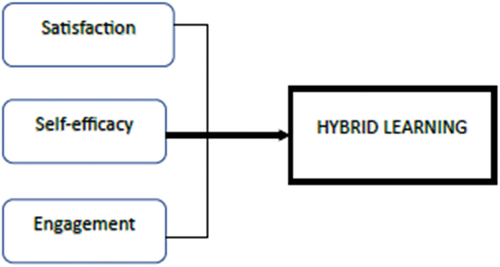

It is acknowledged that HL experiences for students in post-pandemic times are challenging and under-researched (Singh et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, studies have consistently shown that student perceptions are an important determinant of student behaviour. Since perceptions are likely to affect students’ attitudes towards learning and, consequently, influence their performance, it is critical that we have an understanding of hybrid learning (HL) from the student’s perspective. For this reason, the proposed study aims to: (i) investigate students’ experiences with HL (self-satisfaction, self-efficacy, and engagement), (ii) identify issues associated with a hybrid pedagogy, and (iii) identify areas for improvement in the hybrid delivery in the HE setting.

Literature review

Defining hybrid learning

HL has been defined as a mixed mode of instruction, formally combining traditional f2f and pure online learning. HL has been theorized as complex, requiring the optimization of online and f2f instructions (Linder, Citation2017). Flexibility in HL allows students to engage in courses independent of space and time, with interactions unattainable in traditional classrooms realizable (Bouilheres et al., Citation2020). As a means of sustaining education, many HEs invest in technology-enhanced learning spaces (Weilage & Stumpfegger, Citation2022) wherein on-scene and offsite students can concurrently partake in educational activities (Bustamante et al., Citation2022). In this paper, HL refers to the “mixed mode of instruction, which formally combines f2f learning and distance learning by incorporating technology to facilitate the learning process” (Olapiriyakul & Scher, Citation2006, p. 288). There are currently different HL designs implemented in higher learning institutions. Some defined HL as a teaching approach in a blended environment, where the learning instructions combines in-person teaching with asynchronous online learning (Gleason & Greenhow, Citation2017; Hall & Mooney, Citation2010). Others designed HL which involves in-person and remote learners, taught synchronously using technology (Raes et al., Citation2020; Zydney et al., Citation2019). The main difference between these two designs lies in whether students are required to participate in the course in real-time (synchronously) or complete course components on their own time (asynchronously). In our study, the type of HL we focused on combines traditional face-to-face instruction (synchronous) with online learning activities (asynchronous).

Student experiences of hybrid learning

Studies on HL have reported many benefits. By offering a HL option, students enjoy the flexibility to study remotely (Jo, Citation2022; Lin, Citation2014; Q. Wang et al., Citation2017). This approach thus ensures continuity of instruction and promotes student retention (Jo, Citation2022; Lakhal et al., Citation2017; Q. Wang et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, HL caters for the various learning styles of students with diverse backgrounds (Wiles & Ball, Citation2013). Students can take advantage of the in-person interactions during class and utilize the enriched educational guidance available online.

Although HL was reported to offer many advantages (Nikolopoulou, Citation2022), existing studies highlight numerous challenges in implementation (Raes, Citation2022). These challenges include infrastructure and technological challenges (i.e., environment, machine, material) and pedagogical challenges (i.e., faculty readiness, acceptance, student engagement), which are further compounded by the disparate needs of a diverse university community.

As infrastructure differs within institutions, it is understandable that the accessibility of functional connectivity remains the primary challenge for learners’ engagement (Roshid et al., Citation2022; Zahra & Sheshasaayee, Citation2021). This is particularly true in developing nations (Khlaif et al., Citation2021; Roshid et al., Citation2022). Apart from a stable Internet connection, hardware and easy-to-use software are also essential. An example of technical issues is the audio and video issues hindering discussion communication. The various issues encountered negatively affect the learning experience (Marey et al., Citation2022), as reported in their lack of engagement (Chiu, Citation2022) and low self-efficacy (Guoyan et al., Citation2021).

Remote and on-site learners experience the class differently (Nikolopoulou, Citation2022). Studies have revealed that implementing HL can foster unsatisfactory views regarding the student learning experience due to the lack of social presence (Gleason & Greenhow, Citation2017; Phan et al., Citation2023; Yuan, Citation2023). A few contributing factors to this dissatisfaction are a lack of communication between facilitators and learners and the lack of innovation in how learning technologies foster an engaging learning experience for students. Many studies found that offsite learners feel detached from facilitators and f2f peers (Y. Huang et al., Citation2017; Y.-C. Huang et al., Citation2019; Ramsey et al., Citation2016) as they may be bereft of human interaction (Gagnon et al., Citation2020). Learners in remote classes were also reported to be distracted during class and lose focus on the class’s continuity (Abuhassna et al., Citation2022). A synchronous HL environment also means greater self-discipline is vital for offsite students (Velamazán et al., Citation2022). As facilitator presence is somewhat limited, there is less control over students’ engagement, which may also shape HL effectiveness for students (Raes, Citation2022; Raes et al., Citation2020).

Satisfaction, self-efficacy and engagement in hybrid learning

Learning satisfaction refers to the level of contentment or fulfilment a learner experiences in the learning process. It is the perception of how well the learning experience meets the expectations and needs of the learner, including the quality of the instruction, materials, resources, and support provided. High levels of learning satisfaction may lead to increased motivation, engagement, and retention of the learned material (Hew et al., Citation2020; She et al., Citation2021). In addition, it has been reported that a high level of learning satisfaction results in a continued interest in learning and ultimately improves student retention (Gopal et al., Citation2021; Wu et al., Citation2015).

Self-efficacy in learning refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to successfully perform a learning task or achieve a learning goal (Bandura et al., Citation1999). It is the confidence one has in their abilities to acquire, comprehend, and apply knowledge and skills effectively. Self-efficacy can influence a learner’s motivation, persistence, and performance and can be influenced by various factors such as past experiences, feedback, and social comparison. High self-efficacy in learning can lead to increased engagement, a positive attitude towards learning, and a higher likelihood of achieving learning goals (Rorimpandey & Midun, Citation2021; Shea & Bidjerano, Citation2010).

Engagement is a multifaceted construct that involves cognitive, behavioural and affective involvement in traditional and online learning environments (Kuh, Citation2009). Astin (Citation1999) defined engagement as the behavioural component related to students’ investment in their learning experience. Schlechty (Citation2011) viewed student engagement as the effort students put into tasks with persistence and commitment, regardless of how tedious and repetitive they may be.

However, online learning may present challenges regarding emotional engagement due to the limited inclusion of visual communication cues, such as gestures, smiles, or tone of voice. If students exhibit low engagement during the learning process, including in-class activities and online discussions, the benefits of HL might be less apparent (Hara et al., Citation2000). Low levels of engagement with academic activities can lead to dissatisfaction, negative experiences, underachievement, and dropping out of courses (Finn & Rock, Citation1997; Fredricks et al., Citation2004; Kuh, Citation2009; Skinner & Pitzer, Citation2012). Therefore, promoting and sustaining engagement in the learning process is essential for academic success.

Overall, high levels of self-efficacy, engagement, and satisfaction with HL can result in improved motivation, knowledge retention, learning attitudes, and academic success (Carini et al., Citation2006). Low levels of participation, however, can lead to discontent, unpleasant experiences, underachievement, and course abandonment. Therefore, in HL environments, encouraging and maintaining involvement in learning is essential for academic achievement.

Extant gap

Although HL holds numerous benefits, research-based documentation is mixed (Aristika & Juandi, Citation2021). Many HEs have opted for HL as a way forward despite not fully understanding hybridity and risk falling into another panic-gogy (Kamanetz, Citation2020). Fullan (Citation2001) reminds us that in educational change, meaning must be accomplished at every level of the system, but if it is not done at the level of the students, all is lost. Accordingly, this study endeavours to understand the post-pandemic HE student experiences with HL at a deeper level. Such insights provide empirical evidence and form a basis for targeted policy and practical implications to further enhance hybrid T-L practices.

Research questions

Main Research Question:

What are HE students’ overall experiences with HL in the post-pandemic setting?

Supporting Research Questions:

RQ1.1

What is the level of satisfaction among students with HL?

RQ1.2

What is the level of self-efficacy reported by students in their HL experiences?

RQ1.3

To what extent do students report engagement with HL?

RQ1.4

What are the perceived benefits and drawbacks of HL according to students?

Methodology

The study adopts a sequential mixed methods approach (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2010) to answer the research questions. illustrates the sequential progression of the study.

Upon receiving ethical clearance on 21 July 2022 (SUHREC 20,226,596–10251), recruitment emails were sent to students in six main HE institutions in Sarawak, Malaysia, from August 2022 to November 2022.

Data collection

Phase one instrument: questionnaire

The first phase utilized an online questionnaire. Cohen et al. (Citation2007, p. 207) confirm the application of questionnaires in the initial phase of a study in that they “can be exploratory, in which no assumptions or models are postulated, and in which relationship and patterns are explored”. In this study, the questionnaire provides a systematic approach for the initial exploration of emerging themes of students’ experiences with HL. The questionnaire’s design was adapted from an extensively used instrument by Zimmerman and Kulikowich (Citation2016) on self-efficacy and Y. Wang (Citation2003) on e-learning satisfaction, which also contained items on student engagement. The reliability results of the scale revealed a Cronbach alpha of 0.95 for learning satisfaction, 0.95 for student engagement, and 0.93 for the self-efficacy subscale (See Appendix for instruments).

Questionnaire procedure

The questionnaire was distributed to six HE institutions (public n = 3; and private n = 3) in various divisions in Sarawak by partner researcher-practitioners within their institutions in August 2022. The participants were selected through opportunity and convenience (Bryman, Citation2008). The students consisted of those in various stages of their academic studies (i.e., 1st year, 2nd year, 3rd year, final year of degree) and various academic disciplines (i.e., science, humanities) to ensure good HE representation. Phase One took place from August to September 2022.

Phase two instrument: semi-structured interviews

Phase Two utilized semi-structured interviews (Bogdan & Biklen, Citation2007). This interpretive orientation is intended to gain insights into how students view HL, particularly on self-satisfaction, self-efficacy, and engagement. Semi-structured interviews will provide depth to the quantitative results and clarify results emerging from the questionnaire data (Janesick, Citation2000). The interview guide was designed based on questionnaire findings and piloted on three HE students who helped further refine the interview questions.

Semi-structured interview procedure

Only students who provided consent were chosen to be involved in the interviews. It was important that interview participants have experienced offsite and in-class parts of HL. Interview participants were contacted through details provided in a form attached to the questionnaire in Phase One. They were given the information sheet and consent form via email and signed on the day of the interview. A neutral and non-threatening meeting time and location were set up. The interviews took no longer than an hour and were audio-recorded. Anonymity was maintained with pseudonyms. Phase Two was conducted from 10 to 20 October 2022.

Data analysis

Questionnaire analysis

SPSS25.0 was utilized in analysing questionnaire data. Two primary forms of statistical analysis were conducted: (i) descriptive statistics to unveil arising tendencies and population descriptions, and (ii) a Spearman’s rank-order correlation to determine the relationship between students’ learning satisfaction, self-efficacy, and engagement.

Semi-structured interview analysis

Data analysis from the semi-structured interviews involved several steps: transcription, coding, analysis, and interpretation. Through NVivo 11, interview data were systematically analysed by grouping coding strips (coded parts) into themes in the project database, each representing a category. Coding categories were revised rigorously to ensure no redundancies (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990). Coding was subjected to several rounds of iteration, and the meaning units used were that “preserve the psychological integrity of the idea being expressed” and “neither fragment the idea into meaningless truncated segments nor confuse it with other ideas that express different themes” (Ratner, Citation2002, p. 169).

Phase one results

In total, 246 students responded to the survey, where 102 (41.50%) were male and 144 (58.50%) female. The majority of respondents, 219 (89.02%), were aged 18–24, followed by those aged 24–35 (9.76%). A significant proportion of respondents were local students, 218 (88.60%), and the remaining 28 (11.40%) were international students. The demographic breakdown is presented in below:

Table 1. Demographic breakdown of questionnaire respondents.

Just over half were undergraduate students, 140 (56.91%), with the remaining being diploma students, 71 (28.86%), pre-university students, 25 (10.16%) and 10 (4.07%) postgraduate students. Students’ disciplines were almost equally distributed, with 122 (49.59%) from HSS and 124 (50.41%) from STEM. Most respondents were from Private HE institutions, 156 (63.40%), with just over a third from Public HE institutions, 90 (36.60%).

Satisfaction with hybrid learning

A descriptive analysis was conducted to capture students’ HL satisfaction. All the items analysed have a mean of around “4”, representing “Agree” on the five-point Likert scale. With the majority of items averaging a mean of 4.12, it can be concluded that respondents mostly agree that their HL experience is satisfactory. “ … easy access to the virtual classroom and online communication platforms” is rated the highest (4.30) for HL satisfaction, followed by “ … access to IT resources (e.g., laptops, tablets)” (4.23). Statements that were rated the lowest were “ … easy access to relevant learning resources” (3.93) and “ … my academic achievement in HL” (3.99). The standard deviation (SD) for all items is less than 1, signifying majority of respondents indeed rated the statements as agreeable with a “4” on the five-point Likert scale (see below).

Table 2. Descriptive analysis of students’ satisfaction in HL.

Self-efficacy with hybrid learning

A descriptive analysis was conducted on items to capture students’ self-efficacy in HL. The statement with the highest rating is “ … increases my knowledge of online resources available” (4.21), followed by “ … I can understand the basic concepts taught in HL courses” (4.16). The lowest-rating statement is “ … HL helps me build strong social connections with others” (3.71), followed by “ … I will receive an excellent grade(s) with HL” (3.78). The SD for all items is less than 1, signifying majority of respondents indeed rated the statements as agreeable with a “4” on the five-point Likert scale (see below).

Table 3. Descriptive analysis of students’ self-efficacy in HL.

Student engagement with hybrid learning

A descriptive analysis was conducted to examine students’ engagement in HL. The statements with the highest mean are “Electronic communication with the lecturer is productive” (4.01), “Every student could contribute and/or speak up without interruption” (4.01), and “There is adequate opportunity to discuss with lecturers’ (4.00). The statement with the lowest mean is “I find my classmates more empathetic towards my struggle to learn” (3.65), followed by “I have a strong rapport with lecturers.” (3.71). However, “It is easy and convenient to interact with other students in HL” and “I can overcome barriers that prevent me from building friendships with classmates despite our locality” have a SD of more than “1”. This indicates that the ratings received may vary more widely from 3.73 and 3.78, respectively (see below).

Table 4. Descriptive analysis of students’ engagement in HL.

Relationship between satisfaction, self-efficacy, and engagement with hybrid learning

A Spearman’s rank-order correlation was conducted to determine the relationship between students’ learning satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy. There was a strong, positive correlation between students’ learning satisfaction and engagement, which was statistically significant (rs = .759, p < .001). The correlation between students’ learning satisfaction and self-efficacy was also strong, positive, and statistically significant (rs = .776, p < .001). A strong, positive correlation was also found between student engagement and self-efficacy, which was statistically significant (rs = .773, p < .001) (See ).

Table 5. Correlation between self-efficacy, engagement and learning satisfaction.

Connecting phase one and phase two

Phase One revealed an overall positive experience with HL in HE, highlighting strong links between self-efficacy, satisfaction and engagement (See ). Challenges linked to the social aspects of HL (i.e., the social interaction between peers and their lecturers) were also identified. These findings warranted further examination in Phase Two (See ).

Questions were curated to elicit information about their experience with HL (positive and negative), activities and aspects of HL, which made them feel confident, satisfied and engaged in their learning.

Phase two results

Nine students agreed to participate in this phase. The demographic breakdown is as follows (see ):

Table 6. Demographic breakdown of phase two participants.

Most interview respondents were male, 7 (77.8%) with 2 (22.2%) female students. A large number of respondents were aged 18–24, 7 (77.8%), and only one each aged 25–34 (11.1%) and 35–44 (11.1%). The majority were local students, 7 (77.8%), and 2 (22.2%) were international students. More than half were undergraduates, 5 (55.6%), followed by 3 (33.3%) respondents at the diploma level, and only 1 (11.1%) postgraduate student. Just over half were in their 3rd or final year, 5 (55.6%), followed by 2 in their 1st year (22.2%) and one each in their 4th or final year (11.1%) and postgraduate (11.1%). The emerging themes from students’ positive HL experiences include flexibility, self-regulation, enhanced engagement, satisfaction and self-efficacy. Negative HL experiences were impacted by a lack of social interaction, technological impediments, and teachers’ competence. The summary of themes, sub-themes and illustrative quotes are presented in .

Table 7. Emerging themes from qualitative analysis.

Learning opportunities afforded by hybrid learning

Like Phase One findings, all students reported high levels of satisfaction, self-efficacy and engagement with HL. Though there were nuances in students’ responses, their reported experience with HL has been mitigated by their remote learning experience during the pandemic. With the student demographic made up of 3rd year (n = 5), 4th year(n = 1) and Postgraduate; (n = 1) students, it is understandable that students had mixed reactions when HL was implemented. This anxiety was aptly captured by Monica’s response when asked about her initial reaction to transitioning to HL. She reported:

Oh no, here we go again. With online [in 2020 and 2021], I struggled, you know, communicating with groupmates. So, that was already an issue. Now with hybrid, it’s sort of like the same thing again. You must go through the same processes and try to get used to it.

Liam reported similar sentiments when asked about his experience with HL; “when online happened, I told myself, ‘Let’s just get through this’. Then when hybrid came, my initial concern was the technology limitations, but at the end of the day, I was like, ‘Let’s just see how things go’”.

Nonetheless, all students agreed that hybrid afforded a more flexible approach to learning, thus influencing their satisfaction with HL. The combination of digital and f2f content delivery was perceived to be beneficial, providing them with the best facets of each approach. Samuel explained this:

I love the hybrid implementation because it brought in the best of both worlds. There are students like myself, who were so eager to go back to normal, and that’s where the physical aspects of hybrid came in. We get to go back to campus, see other students in real life … see our lecturers.

In particular, students reported that their HL experience was significantly enhanced when both aspects (f2f and online) were utilized effectively. According to Daniel, in addition to the engaging physical classroom, “the educator was very enlightened using HL … I could see that she invested a lot to improve the online learning experience”. For Elias, the autonomy provided through recorded videos was beneficial. This experience was further augmented by the physical classes whereby he could “ask some questions physically, to get a better understanding of the unit”. The positive HL experience, thus, shaped their engagement. This is because when students are satisfied with the learning experience, they are more motivated in the course, which increases engagement. HL also afforded more opportunities for students’ self-regulated online and offsite learning. To illustrate, Elias reported that HL “allowed me to learn to work from home, as well as to be more independent to perform my own study”. There were also cases whereby students who struggled in online learning during the pandemic could be more engaged academically in the physical aspects of HL. One case which exemplified this was Richard. He explained:

It was my first physical class I went to after all those years of being in the pandemic. So, it was like going to a new class like on the first day of my university life… and the lecturer was very supportive, and everything was in order. So, it was a great experience from that perspective.

In the same manner for those who struggled with f2f classes, students like Elias leveraged the advantages of online learning, “The good thing is I can listen on the go because there is always recorded sessions. So, I can reflect back on what I learnt. In f2f sessions, we don’t have that feature”. This increased flexibility provides opportunities for students to be more self-directed and manage their time effectively.

In this study, students’ online learning experience during the pandemic was reported to be key in aiding students’ transition into HL. Consequently, the high level of self-efficacy (realized through the online mode during the pandemic) allowed students to be more engaged and perform better academically. To illustrate, Harrison attributed the success of his hybrid experience: “I had confidence in the facilities that the university has provided for me, and I had confidence in the lecturers”. Similarly, Samuel’s self-efficacy in HL was evident: “It was my best performing semester. Yeah, for two of those units that I took last semester, I was awarded Top Scorer. So, I would have to say that it was a very successful learning method for me”.

In this phase, it can be surmised that when students have a positive experience with HL, they become more engaged and motivated to learn. Their ability to self-regulate and feel confident in their ability to succeed in HL impacts positively on their academic performance.

Challenges faced in the hybrid environment

In the same manner, when aspects of HL were not leveraged effectively, students became disengaged, affecting their self-efficacy. Elias laments, “the business unit was a bit vague, because of that I had, perform my own self-study even more. Even though there was recorded sessions, but then it was more of a one-way communication. I was honestly worried for the outcome of the unit”. Furthermore, there were cases where students reported that educators who are not “tech-savvy” caused students to disengage:

… some of my subjects had un-tech savvy educators … I guess, having a hard time trying to educate via online without the proper tools, just simply via Google Meet and explain via slides. It’s very unentertaining for the student part. (Daniel)

There were also issues reported with the online component as not having optimal learning conditions ranging from audio quality and Internet connection to unfamiliarity with the learning management system (LMS). As a result, students concluded that “one of the biggest disadvantages of HL is that while you are bringing the good of both worlds, you’re also bringing the bad of both worlds” (Liam). It can be observed that students who are dissatisfied with their HL experience may have lower self-efficacy and be less engaged. This is because when students are dissatisfied, they may feel frustrated, disengaged, and less confident in their ability to succeed, as revealed by the interviewees.

Nonetheless, all students believed that HL, in time, could be an optimum mode of learning if issues pertaining to the teacher, technology, and infrastructure can be addressed. Therefore, in this phase, it can be surmised that this new approach requires students to adapt to new technical and pedagogical approaches, and HL was a positive experience when the facets of f2f and online learning were leveraged optimally.

Discussion

The best of both worlds

The findings indicate how the challenges and benefits of hybrid pedagogy contribute to students’ satisfaction, self-efficacy, and engagement. Our findings support that of others (see Bustamante et al., Citation2022; Detyna et al., Citation2022; Munday, Citation2022) in which HL benefits include increased engagement, flexibility, heightened online learning experience, and enhanced self-regulation (Bouilheres et al., Citation2020; Q. Li et al., Citation2021). Specifically, students’ perceived HL benefits are associated with a positive blend of f2f and online education benefits (i.e., socializing in class and more regulated learning online), which aligns with recent research (Bustamante et al., Citation2022; D. Li, Citation2022; Pischetola, Citation2022).

The challenge of curating a social presence within this hybrid approach reverberated across the two phases. Like other studies (Aristika & Juandi, Citation2021; Lapitan et al., Citation2021; Lorenzo-Lledó et al., Citation2021), our findings revealed that students were discontented when (i) instructor facilitation was unavailable, (ii) there were unequal interaction or engagement opportunities, and (iii) online students were unresponsive. Our finding lends support to Pischetola (Citation2022), who maintains that while teacher-learner interaction has become progressively automated, students’ sense of belonging within HE is increasingly dependent upon “human touch” (Cureton et al., Citation2021), affectivity (Hickey-Moody, Citation2013), and teachers’ care-filled receptiveness (Dall’Alba, Citation2020) (as cited in Pischetola, Citation2022, p. 71). Our study thus confirms that teachers’ role is paramount in hybrid delivery. Teachers’ role is heightened, requiring various teaching competencies and strategies (Badiozaman, Citation2021; Badiozaman et al., Citation2021; Lim et al., Citation2022; Müller et al., Citation2021) to cope with rapid technological changes.

Our findings also highlighted how students navigated the accelerated educational shift due to COVID-19. That students had positive student engagement, satisfaction, and self-efficacy with HL despite academic disruptions demonstrates their adaptability and resilience. Like other studies that highlight the role of self-efficacy in HL (see Acosta-Gonzaga & Ruiz-Ledesma, Citation2022; Martin et al., Citation2023), students were able to navigate HL due to their efficacy with online learning during the pandemic and the flexibility offered by this pedagogy. In this study, flexibility also promoted self-regulation, highlighting the importance of self-regulation training in HE students.

The link between satisfaction, engagement and self-efficacy in hybrid learning

Based on the data, a positive relationship exists between these constructs, and satisfaction, engagement and self-efficacy in HL are mutually reinforcing and can enhance each other. Our findings affirmed that in prolonged experiences with HL when students are satisfied with their learning experience, they are more likely to be engaged and motivated to learn. This engagement can lead to a sense of accomplishment and increased self-efficacy, which can further enhance satisfaction. Our finding thus resonates with Shea and Bidjerano (Citation2010), who maintains that students’ efficacy belief can boost their intrinsic motivation to learn, promote effective learning strategies, and further enhance their engagement.

Satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy are three important factors influencing students’ success in a HL environment. When students are satisfied with their learning experience, they are more likely to be engaged and motivated, which can lead to higher levels of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy, in turn, can further enhance engagement and satisfaction. When students are satisfied with their learning experience in a HL environment, they are more likely to be engaged and motivated to learn. This engagement can lead to a sense of accomplishment and increased self-efficacy, which can further enhance satisfaction.

The active roles of hybrid learners have contributed to a more thorough account of knowledge construction in technology-mediated environments expanding the descriptive and explanatory power of satisfaction, self-efficacy and engagement. Overall, the link between satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy in HL is that they work together to create a positive and effective learning experience. By enhancing each other, these factors can contribute to greater student success and achievement in HL environments. HL, which combines online and f2f instruction, has given rise to new pedagogical approaches and strategies that take advantage of the unique opportunities and challenges presented by this mode of instruction. Our findings also indicate that since HL offers flexibility, to experience satisfying learning, students need not have specific competencies but self-regulatory skills and the ability to figure out the right mix of learning options. This echoes Xiao et al. (Citation2020)’s study whereby learners’ satisfaction and experience in HL are contingent on their ability to identify the space and pace of learning that empowers them.

Overall, HL reflects a shift towards more student-centred and interactive learning environments and a greater focus on using technology and data to personalize instruction and support student learning.

Conclusion

Given today’s uncertainties, gaining a nuanced understanding of students’ HL experience during the COVID-19 pandemic is vital. The findings of this study have addressed the gap in the literature on HL during Covid times and unmasked how students navigated accelerated educational shifts. The study revealed positive experiences with HL due to students’ efficacy with remote learning during the pandemic and the flexibility offered by this mode. The study confirms that social presence remains crucial for student engagement, and the flexibility afforded by HL promotes self-regulated learning.

Implications

In the context of HE, hybrid T-L is a complex endeavour that requires careful planning and implementation. Teachers must curate engagement and participatory strategies to leverage the optimal benefits of the online and f2f components for positive student experiences. The role of teachers in safeguarding students’ positive HL experience is pivotal, and HEs must provide continuous professional development support to prepare teachers with the skills and knowledge necessary for HL.

The study’s findings emphasize how the transition to various new learning modes can impact students’ experiences negatively or positively. While HL has helped students build resilience and self-regulation by providing opportunities to take ownership of their learning, develop time management, and adapt to different learning environments, teachers must be aware of the challenges students face in a hybrid setting.

Thus, pedagogy cannot be confined to traditional T-L activities in the HE post-pandemic setting. Instead, it needs to be curated in such a way that it supports engagement and builds resilience. With the proper support and guidance, HL has the potential to provide students with a high-quality learning experience that promotes their academic and personal growth.

Limitations and areas for further research

We remain mindful that our findings may not be generalizable to other HEs, and that hybrid teaching may be attempted differently in other contexts. Though the study focuses on students from various academic years and different institutions, it has yielded rich data on HL through examining the complex issues in-depth, within their specific context, and using various data sources. Based on the emergent insights in the study, future studies would benefit from longitudinal studies tracing students’ transition to HL. Additionally, it is useful to examine teachers as agents of change in hybrid pedagogy and explore the effective integration of digital and pedagogical resources into new practices.

Authors’ contributions

IFAB designed the study, conceptualized the work, and wrote the initial draft. AN and VML acquired the data, provided critical feedback and edited the manuscript. AN and VML analysed and interpreted the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ida Fatimawati Adi Badiozaman

Ida Fatimawati heads the School of Research in Swinburne Sarawak. An award-winning multidisciplinary researcher who is driven by issues of equity and access, she has been involved in transformative and impactful research projects with government, industry and HE partners. Ida is part of the team for the “Building Connections for Enterprising Women” project, a project that received ‘Highly Commended’ for the Vice-Chancellor’s Research Excellence Award 2018, ranked First Place for the Swinburne Research Impact Award 2019 and ‘Highly Commended’ for Emerald Interdisciplinary Impact Grant in 2019. In 2020 she won the UN Women Malaysia WEP’s Award for the Community and Industry Engagement Category.

Adeline Ng

Adeline Ng is currently a Senior Lecturer and Associate Dean (Academic Practice) for the Faculty of Engineering, Computing and Science at the Swinburne Sarawak. She is a Professional Engineer with Practicing Certificate (PEPC) with the Board of Engineers, Malaysia, and a member of the Malaysian Cold-formed Steel Institute (MyCSI). She obtained her Bachelor and Master of Engineering in Civil Engineering from Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai, in 2001 and 2002, respectively, and Doctor of Philosophy in Civil Engineering in 2008 at the Oxford Brookes University, UK. In her earlier career, Adeline has practiced as a design engineer in the industry and was also a product and development engineer in a company that specialized in steel structures.

Voon Mung Ling

Voon Mung Ling teaches units in Economics, Human Resource Management and Management. Apart from teaching, she has also published several research articles in journals and a book chapter.

References

- Abuhassna, H., Awae, F., Al Zitawi, D.U.D., Bayoumi, K., & Alsharif, A.H. (2022). Hybrid learning for practical-based courses in higher education organisations: A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 11(1), 1055–1064. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARPED/v11-i1/12861

- Acosta-Gonzaga, E., & Ruiz-Ledesma, E.F. (2022). Students’ emotions and engagement in the emerging hybrid learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 14(16), 10236. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610236

- Aristika, A., & Juandi, D., (2021). The effectiveness of hybrid learning in improving of teacher-student relationship in terms of learning motivation. Emerging Science Journal, 5(4), 443–456. https://doi.org/10.28991/esj-2021-01288

- Astin, A.W. (1999). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Development, 40(5), 518–529.

- Badiozaman, I. (2021). Exploring online readiness in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Teaching in Higher Education, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1943654

- Badiozaman, I., Segar, A.R., & Iah, D. (2021). Examining faculty’s online teaching competence during crisis: One semester on. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-11-2020-0381

- Bandura, A., Freeman, W.H., & Lightsey, R. (1999). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 13(2), 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.13.2.158

- Bogdan, R.C., & Biklen, S.K. (2007). Qualitative research in education: An introduction to theory and methods (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

- Bouilheres, F., Le, L.T.V.H., McDonald, S., Nkhoma, C., & Jandug-Montera, L. (2020). Defining student learning experience through blended learning. Education and Information Technologies, 25(4), 3049–3069. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10100-y

- Bryman, A. (2008). The end of the paradigm wars?. In P. Alasuutari, L. Bickman, & J. Brannen (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social research methods (pp. 13–25). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Bustamante, J.C., Segura-Berges, M., Lizalde Gil, M., & Peñarrubia-Lozano, C. (2022). Qualitative analyses of e-learning implementation and hybrid teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic at Spanish universities. Sustainability, 14(19), 12003. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912003

- Carini, R.M., Kuh, G.D., & Klein, S.P. (2006). Student engagement and student learning: Testing the linkages. Research in Higher Education, 47(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-005-8150-9

- Chiu, T.K. (2022). Applying the self-determination theory (SDT) to explain student engagement in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(sup1), S14–S30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1891998

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education (6th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203029053

- Creswell, J.W., & Plano Clark, V. (2010). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Cureton, D., Jones, J., & Hughes, J. (2021). The Postdigital University: Do We Still Need Just a Little of That Human Touch?. Postdigit Sci Educ, 3, 223–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00204-6

- Dall’alba, G. (2020). Toward a Pedagogy of Responsive Attunement for Higher Education. Philosophy & Theory in Higher Education, 2(2), 21–43. https://doi.org/10.3726/PTIHE022020.0002

- Detyna, M., Sanchez-Pizani, R., Giampietro, V., Dommett, E.J., & Dyer, K. (2022). Hybrid flexible (HyFlex) teaching and learning: Climbing the mountain of implementation challenges for synchronous online and face-to-face seminars during a pandemic. Learning Environments Research, 26(1), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-022-09408-y

- Finn, J.D., & Rock, D.A. (1997). Academic success among students at risk for school failure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(2), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.221

- Fredricks, J.A., Blumenfeld, P.C., & Paris, A.H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

- Fullan, M. (2001). The new meaning of educational change (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203986561

- Gagnon, K., Young, B., Bachman, T., Longbottom, T., Severin, R., & Walker, M.J. (2020). Doctor of physical therapy education in a hybrid learning environment: Reimagining the possibilities and navigating a “new normal”. Physical Therapy, 100(8), 1268–1277. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzaa096

- Gleason, B., & Greenhow, C. (2017). Hybrid education: The potential of teaching and learning with robot-mediated communication. Online Learning Journal, 21(4), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v21i4.1276

- Gopal, R., Singh, V., & Aggarwal, A. (2021). Impact of online classes on the satisfaction and performance of students during the pandemic period of COVID 19. Education and Information Technologies (Dordr), 26(6), 6923–6947. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10523-1

- Guoyan, S., Khaskheli, A., Raza, S.A., Khan, K.A., & Hakim, F. (2021). Teachers’ self-efficacy, mental well-being and continuance commitment of using learning management system during COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative study of Pakistan and Malaysia. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2021.1978503

- Hall, O.P., Jr., & Mooney, J.G. (2010). Hybrid learning systems: Meeting the challenges of graduate management education. In P. Tsang, S.K.S. Cheung, V.S.K. Lee, & R. Huang (Eds.), International Conference on Hybrid Learning 2010: Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Vol. 6248, pp. 35–48). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-14657-2_5

- Hara, N., Bonk, C.J., & Angeli, C. (2000). Content analysis of online discussion in an applied educational psychology course. Instructional Science, 28(2), 115–152. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003764722829

- Hensley, L.C., Iaconelli, R., & Wolters, C.A. (2022). “This weird time we’re in”: How a sudden change to remote education impacted college students’ self-regulated learning. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(sup1), S203–S218. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1916414

- Hew, K.F., Hu, X., Qiao, C., & Tang, Y. (2020). What predicts student satisfaction with MOOCs: A gradient boosting trees supervised machine learning and sentiment analysis approach. Computers & Education, 145, 145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103724

- Hickey-Moody, A. (2013). Affect as Method: Feelings, Aesthetics and Affective Pedagogy. In R. Coleman & J. Ringrose (Eds.), Deleuze and Research Methodologies (pp. 79–95). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Huang, Y.-C., Backman, S.J., Backman, K.F., McGuire, F.A., & Moore, D. (2019). An investigation of motivation and experience in virtual learning environments: A self-determination theory. Education and Information Technologies, 24(1), 591–611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-9784-5

- Huang, Y., Zhao, C., Shu, F., & Huang, J. (2017). Investigating and analysing teaching effect of blended synchronous classroom. 2017 International Conference of Educational Innovation through Technology (EITT) (pp. 134–135). https://doi.org/10.1109/EITT.2017.40

- Janesick, V.J. (2000). The choreography of qualitative research design. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The handbook of qualitative research (2nd edn ed., pp. 379–399). Sage.

- Jo, H. (2022). Determinants of continuance intention towards e-learning during COVID-19: An extended expectation-confirmation model. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2022.2140645

- Kamanetz, A. (2020, March 19). Teaching online classes during the coronavirus pandemic. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/03/19/817885991/panic-gogy-teaching-online-classes-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic

- Khlaif, Z.N., Salha, S., Affouneh, S., Rashed, H., & ElKimishy, L.A. (2021). The covid-19 epidemic: Teachers’ responses to school closure in developing countries. Technology, Pedagogy & Education, 30(1), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2020.1851752

- Kuh, G.D. (2009). The national survey of student engagement: Conceptual and empirical foundations. New Directions for Institutional Research, (141), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.283

- Lakhal, S., Bateman, D., & Bédard, J. (2017). Blended synchronous delivery modes in graduate programs: A literature review and how it is implemented in the master teacher program. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 10, 47–60. https://doi.org/10.22329/celt.v10i0.4747

- Lapitan, L.D.S., Tiangco, C.E., Sumalinog, D.A.G., Sabarillo, N.S., & Diaz, J.M. (2021). An effective blended online teaching and learning strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education for Chemical Engineers, 35, 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ece.2021.01.012

- Li, D. (2022). The shift to online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic: Benefits, challenges, and required improvements from the students’ perspective. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 20(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.34190/ejel.20.1.2106

- Li, Q., Li, Z., & Han, J. (2021). A hybrid learning pedagogy for surmounting the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic in the performing arts education. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 7635–7655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10612-1

- Lim, W.M., Adi Badiozaman, I.F., & Leong, H.J. (2022). Unravelling the expectation-performance gaps in teacher behaviour: A student engagement perspective. Quality in Higher Education, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2022.2090746

- Lin, O. (2014). Student views of hybrid learning. Journal of Computing in Teacher Education, 25(2), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402454.2008.10784610

- Linder, K. (2017). Fundamentals of hybrid teaching and learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2017(149), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20222

- Lorenzo-Lledó, A., Lledó, A., Gilabert-Cerdá, A., & Lorenzo, G. (2021). The pedagogical model of hybrid teaching: Difficulties of university students in the context of COVID-19. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 11(4), 1320–1332. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040096

- Marey, A., Goubran, S., & Tarabieh, K. (2022). Refurbishing classrooms for hybrid learning: Balancing between infrastructure and technology improvements. Buildings, 12(6), 738. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12060738

- Martin, A.J., Ginns, P., & Collie, R.J. (2023). University students in COVID-19 lockdown: The role of adaptability and fluid reasoning in supporting their academic motivation and engagement. Learning and Instruction, 83(6), 101712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101712

- Müller, A.M., Goh, C., Lim, L.Z., & Gao, X. (2021). COVID-19 emergency e-learning and beyond: Experiences and perspectives of university educators. Education Sciences, 11(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11010019

- Munday, D. (2022). Hybrid pedagogy and learning design influences in a higher education context. Studies in Technology Enhanced Learning, 2(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.21428/8c225f6e.b5af8bae

- Ndzinisa, N., & Dlamini, R. (2022). Responsiveness vs. accessibility: Pandemic-driven shift to remote teaching and online learning. Higher Education Research and Development, 41(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.2019199

- Nikolopoulou, K. (2022). Face-to-face, online and hybrid education: University students’ opinions and preferences. Journal of Digital Education Technology, 2(2), ep2206. https://doi.org/10.30935/jdet/12384

- Olapiriyakul, K., & Scher, J.M. (2006). A guide to establishing hybrid learning courses: Employing information technology to create a new learning experience, and a case study. The Internet and Higher Education, 9(4), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2006.08.001

- Phan, A.N.Q., Pham, L.T.T., & Ngo, H.N. (2023). Countering stuckness: International doctoral students’ experiences of disrupted mobility amidst COVID-19. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2023.2175349

- Pischetola, M. (2022). Teaching novice teachers to enhance learning in the hybrid university. Postdigital Science & Education, 4(1), 70–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-021-00257-1

- Raes, A. (2022). Exploring student and teacher experiences in hybrid learning environments: Does presence matter? Postdigital Science & Education, 4(1), 138–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-021-00274-0

- Raes, A., Detienne, L., Windey, I., & Depaepe, F. (2020). A systematic literature review on synchronous hybrid learning: Gaps identified. Learning Environments Research, 23(3), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-019-09303-z

- Ramsey, D., Evans, J., & Levy, M. (2016). Preserving the seminar experience. Journal of Political Science Education, 12(3), 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2015.1077713

- Ratner, C. (2002). Cultural psychology: Theory and method. Plenum. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0677-5

- Rorimpandey, W.H.F., & Midun, H. (2021). Effect of hybrid learning strategy and self-efficacy on learning outcomes. Journal of Hunan University (Natural Sciences), 48(8), 181–189.

- Roshid, M.M., Sultana, S., Kabir, M.M.N., Jahan, A., Khan, R., & Haider, M.D. (2022). Equity, fairness, and social justice in teaching and learning in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2022.2122024

- Schlechty, P.C. (2011). Engaging students: The next level of working on the work. John Wiley & Sons.

- Shea, P., & Bidjerano, T. (2010). Learning presence: Towards a theory of self-efficacy, self-regulation, and the development of a communities of inquiry in online and blended learning environments. Computers & Education, 55(4), 1721–1731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.07.017

- She, L., Ma, L., Jan, A., Sharif Nia, H., & Rahmatpour, P. (2021). Online learning satisfaction during COVID-19 pandemic among Chinese university students: The serial mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(743936). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.743936

- Singh, J., Steele, K., & Singh, L. (2021). Combining the best of online and face-to-face learning: Hybrid and blended learning approach for COVID-19, post vaccine and post-pandemic world. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 50(2), 140–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472395211047865

- Skinner, E.A., & Pitzer, J.R. (2012). Developmental dynamics of student engagement, coping, and everyday resilience. In S.L. Christenson, A.L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 21–44). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_2

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory – procedures and techniques. Sage Publications.

- Velamazán, M., Santos, P., & Hernández-Leo, D. (2022). Socio-emotional regulation in collaborative hybrid learning spaces of formal–informal learning. In E. Gil, Y. Mor, Y. Dimitriadis, & C. Köppe (Eds.), Hybrid learning spaces: Understanding teaching-learning practice (pp. 95–111). Springer International Publishing.

- Wang, Y. (2003). Assessment of learner satisfaction with asynchronous electronic learning systems. Information & Management, 41(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7206(03)00028-4

- Wang, Q., Quek, C.L., & Hu, X. (2017). Designing and improving a blended synchronous learning environment_An educational design research. International Review of Research in Open & Distributed Learning, 18(3). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i3.3034

- Weilage, C., & Stumpfegger, E. (2022). Technology acceptance by university lecturers: A reflection on the future of online and hybrid teaching. On the Horizon: The International Journal of Learning Futures, 30(2), 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/OTH-09-2021-0110

- Wiles, G.L., & Ball, T.R. (2013, June 23–26). The converged classroom [Paper presentation]. 2013 ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Atlanta, Georgia. https://doi.org/10.18260/1-2–22561

- Wu, Y.-C., Hsieh, L.-F., & Lu, J.-J. (2015). What’s the relationship between learning satisfaction and continuing learning intention? Procedia - Social & Behavioral Sciences, 191, 2849–2854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.148

- Xiao, J., Sun-Lin, H., Lin, T., Li, M., Pan, Z., & Cheng, H. (2020). What makes learners a good fit for hybrid learning? Learning competences as predictors of experience and satisfaction in hybrid learning space. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(4), 1203–1219. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12949

- Yuan, R. (2023). Chinese university EFL learners’ foreign language classroom anxiety and enjoyment in an online learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2023.2165036

- Zahra, R., & Sheshasaayee, A. (2021, December 3–4). Challenges identified for the efficient implementation of the hybrid e-learning model during COVID-19. Paper presented at the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Mobile Networks and Wireless Communications (ICMNWC). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMNWC52512.2021.9688533

- Zhao, F., Fashola, O., Olarewaju, T., Moran, F., Dobson, P., Reszka, M., & Mitchell, K. (2022). How hybrid learning can enhance the student experience and teaching outcomes in the wake of COVID-19: A case study of a business school in the United Kingdom. In M.H. Bilgin, H. Danis, E. Demir, & G. Mustafa (Eds.), Eurasian business and economics Perspectives (pp. 69–89). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94672-2_5

- Zimmerman, W.A., & Kulikowich, J.M. (2016). Online learning self-efficacy in students with and without online learning experience. American Journal of Distance Education, 30(3), 180–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2016.1193801

- Zydney, J.M., McKimm, P., Lindberg, R., & Schmidt, M. (2019). Here or there instruction lessons learned in implementing innovative approaches to blended synchronous learning. Tech Trends, 63(2), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0344-z

Appendices Appendix A:

Questionnaire Sample Items

A1: Students’ Demographic Information

Please indicate your gender.

Please indicate your age range.

Please indicate your academic level.

Please indicate your faculty division.

Please indicate your preferred learning style.

A2: Students’ Technological Experience

1. Please indicate whether you access the Internet during the pandemic for purposes relevant to your higher education context.

Yes, I connect to the Internet

No, I do not connect to the Internet

2. Please rate your proficiency with each of the following technological tools. (1 =Strongly disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = No opinion; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly agree)

1. I am proficient at typing and keyboarding.

2. I am proficient in Microsoft Word.

3. I am proficient in WWW and Internet search.

4. I am proficient in communication platforms and software.

5. I am comfortable with technology in general.

3. Please rate your learning experience towards each of the following LMS tools. (1=This tool is detrimental to my learning experience; 2=This tool did not enhance my learning experience; 3=This tool was not used in this course; 4=This tool enhanced my learning experience; 5=This tool enhanced my learning experience greatly)

1. Course Documents

2. Assignments

3. Discussion Board

4. Learning Materials

5. Recorded Lectures

A3: Students’ Preference with Learning Modes

Please rate your degree of preference in the learning modes pre-pandemic, during endemic, and post-pandemic. (1 = Not preferred at all, 2 = Not preferred, 3 = No opinion, 4 = Preferred, 5 = Highly preferred)

1. E-learning

2. F2F learning

3. HL

B1: Students’ HL Experience

Please rate how well you agree or disagree with the following statements in your overall HL experience. (1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = No opinion; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly agree).

I can study anytime, anywhere, and at my own pace with HL.

I find HL caters better to my (various) learning style(s).

I am more responsive to lecturers’ questions with HL classes.

Students’ ideas and suggestions are used during classes.

Lecturers’ expectations of students’ participation and output from studying online is clear.

B2: Students’ HL Satisfaction

Please rate how well you agree or disagree with the following statements on your overall HL satisfaction. (1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = No opinion/Not applicable; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly agree).

I am satisfied with the lecturer’s skills and knowledge in HL pedagogy (i.e., teaching strategies).

I am satisfied with the lecturer’s skills and knowledge in HL educational technology.

I am satisfied with the use of appropriate educational technology tools employed in HL for various course contents (e.g., the use of virtual and augmented reality or games for practical or lab sessions, internships, or practicums).

I am satisfied with the easy access to the virtual classroom and online communication platforms (e.g., MS Teams, Meet, Zoom, and etc.).

I am satisfied with all HL sessions.

B3: Students’ Engagement in HL

Please rate how well you agree or disagree with the following statements about your engagement with educators and classmates in HL. (1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = No opinion; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly agree).

I have a strong rapport with lecturers.

There is adequate opportunity to establish peer support.

I feel like I am a part of a group of students and teachers committed to learning.

I regularly and confidently express and share my ideas and thoughts with other classmates.

I frequently come up with responses that are reflective and well thought out.

B4: Students’ Self-efficacy in HL

Please rate how well you agree or disagree with the following statements about your self-efficacy in HL. (1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = No opinion; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly agree).

I’m confident I will receive excellent grade(s) with HL.

I’m confident in my ability to apply what I’ve learnt with HL to solve practical problems.

I’m confident HL helps me build strong social connections with others.

I’m confident HL helps build my soft skills (e.g., communication skills, teamwork skills, leadership skills, problem-solving skills, critical-thinking skills, reflective-thinking skills, self-learning skills, and etc.).

I’m confident HL helps expand my English vocabulary and reading capabilities.

We would like to invite you to attend an interview session to further discuss your HL experiences.

Please indicate your interest to attend the interview.

Yes, I am interested.

No, I am not interested.

Thank you for agreeing to attend the interview session.

Please include your name and email in the space below.

Appendix B:

Interview Guide

How do you describe HL?

Tell me about your experiences with HL courses (satisfaction, engagement, confidence). Can you elaborate on the experience by relating it to a particular activity?

Tell me about any challenges you expect in a hybrid course? How would you overcome these challenges?

What feelings or thoughts were generated by the experience of HL?

What specific HL activities do you feel confident participating in? What specific HL activities do you not feel confident participating in?

What kind of technology is used in your HL? Describe your experiences using this technology.

Based on your experience, what are the benefits of HL? Can you expand on the experience by relating it to a particular activity?

What advice would you provide to a new student about to embark on HL?