ABSTRACT

This article examines the regulatory, political and financial context for global justice advocacy by Canadian civil society organisations (CSOs). We find that federal regulations have constrained these organisations’ capacity for advocacy, and that CSOs themselves restrict their advocacy work beyond regulatory requirements due to risk aversion and funding challenges. Our study draws on tax data and other publicly available information, and on interviews with CSO staff and board members. Canada’s regulations on policy advocacy by CSOs changed in early 2019, but the previous legal framework continues to shape their work. To better engage Canadians in their cause, CSOs need to revisit their advocacy practice.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article examine le contexte réglementaire, politique et financier dans lequel les organisations de la société civile (OSC) canadiennes font la promotion de la justice globale. Nous constatons que la réglementation fédérale a effectivement limité la capacité de plaidoyer de ces organisations, mais aussi que les OSC limitent elles-mêmes leurs activités en deçà de ce que permet la réglementation à cause de leur aversion pour le risque et des difficultés de financement. Notre étude s’appuie sur des données fiscales et sur d’autres informations publiques, ainsi que sur des entretiens avec des membres du personnel et des conseils d’administration de différentes OSC. La réglementation canadienne a été modifiée au début de 2019, mais le cadre juridique précédent continue de façonner les pratiques des OSC en matière de plaidoyer politique. Pour mieux mobiliser les Canadiens en appui aux causes qu’elles défendent, les OSC doivent revoir leurs pratiques.

The idea that government policy and legal changes in the global North and South are essential for sustainable development and improvements in human well-being should not be controversial. Civil Society activists, theorists of global justice and government leaders all agree in principle that legal and policy change is crucial to promote international development and respect for human rights, and that civil society organisations (CSOs) should play important roles in public policy making and legislative reform. However, in Canada advocacy for global justice by most civil society organisations is highly constrained. Until 2019, not only have federal regulations seriously limited the capacity of charitable organisations to advocate legal and policy change in Canada and globally, but Canadian charities themselves have also demonstrated a high level of risk aversion towards advocacy work. The results are an impoverishment of global policy making in Canada, weak public understanding of roles of legal and policy change in efforts to achieve global justice, and a failure to adequately support struggles for legal and policy reform in other parts of the world where that support is urgently needed. In late 2018, the federal Liberal government made significant legal changes that give charitable organisations much greater freedom to engage in public policy advocacy (Carter and Prendergast Citation2019; CRA Citation2019). However, deeper changes are needed within Canadian charities and in public understanding of the relationships between advocacy, charity and social justice to contribute seriously to struggles for global well-being.

This examination of the regulatory, political and financial context for global justice advocacy focuses particularly on Canadian civil society organisations (CSOs) with registered charity status. We focus on organisations with charity status, rather than nonprofit organisations, for reasons explained in detail below. Nonprofits without charity status are completely free to engage in public policy debates and do not face the complex federal regulations that apply to charities, but they cannot issue tax deduction receipts for donations. Very few nonprofits in Canada have been able to generate significant funding to support public policy engagement. The big money, relatively speaking, is in charity status, so that is where we focus attention. The article argues that federal regulations and policy practice have seriously constrained advocacy capacity within Canadian CSOs, but also that CSOs themselves restrict their advocacy work well beyond what federal regulations allow due to risk aversion and funding challenges. Now that the legal regulations for Canadian charities have changed to allow a much broader range of public policy action, Canadian CSOs will need to make important strategic decisions about whether and how to engage more deeply in public policy debates.

The article develops this argument in five parts. First, we examine the meaning of advocacy in the contemporary Canadian legal context. Then we analyse the importance of advocacy from the perspectives of CSO organisational mandates, public policy making and public engagement. A brief history of federal regulation of CSO advocacy is followed by an examination of empirical evidence of CSO advocacy in Canada, drawing on data from the Canada Revenue Agency, the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying, the Canadian Council of International Cooperation (CCIC) and interviews with CSO staff and board members. The final article section discusses economic factors that have shaped CSO advocacy, with an emphasis on the challenges that CSOs face to generate funding for policy advocacy work.

What is public policy advocacy?

In 1999 the Government of Canada and the Voluntary Sector Task Force defined advocacy as “the act of speaking or of disseminating information intended to influence individual behaviour or opinion, corporate conduct, or public policy and law” (Citation1999, 50). Advocacy can include a wide range of specific tactics ranging from street protests to social media campaigns to quiet backroom lobbying as well as combinations of these approaches. However, in the Canadian context, it is most useful to understand advocacy in relation to the Canada Revenue Agency’s (CRA) regulations on “political activities” by charities, in effect until December 2018, as this definition lies at the centre of recent debates about CSO advocacy. While the law on public policy advocacy by CSOs changed in late 2018, the previous legal framework will likely shape the internal culture and organisational behaviour of Canadian CSOs for many more years, and so is important to understand. The CRA’s definition of “political activities” was misleading as it was used to distinguish policy advocacy that engaged Canadian citizens in public calls to action from advocacy that did not involve calls to public action – which does not reflect common understandings of the term “political”. For this reason, we use the term “political activities” in quotation marks to clarify that it was a specific regulatory concept.

The pursuit of funding through individual private donations leads many CSOs to seek charity status, as the opportunity to issue tax receipts provides a significant incentive to donors and is often a requirement for funding from philanthropic foundations (Harvie Citation2002, 10–11). Charitable status requires CSOs to comply with a complex range of federal regulations, which the government justifies as conditions for the de facto subsidy that charitable donations represent in terms of lost tax revenue. While charitable activity is provincial jurisdiction in Canada, the federal jurisdiction over income tax has become the most important component of the regulatory regime for charities, which are carefully monitored by the CRA’s Charities Directorate. Most importantly, the CRA regulates the allowable “purposes” of registered charities, which include four categories that were established in the 1891 Pemsel caseFootnote1 in England:

The relief of poverty

The advancement of education

The advancement of religion

Other purposes beneficial to the community as a whole that courts have identified as charitable, which courts and the CRA have interpreted to include protection of the environment, upholding human rights, promoting health, promoting racial equality and a range of other purposes (CRA Citation2013; CRA Citation2019; Elson Citation2007, 42–43; Harvie Citation2002, 12).

The basis for these four categories and for determining whether a charity’s purposes are “beneficial to the community” (the “public benefits test”) is the preamble to the English Charitable Uses Act of 1601, commonly referred to as The Statute of Elizabeth (CRA Citation2006). In 1917 the English House of Lords ruled that advocacy for legal and policy change was not a valid charitable purpose because “the Court has no means of judging whether a proposed change in the law will or will not be for the public benefit” (cited in Harvie Citation2002, 12). While this judgement has been widely criticised by legal scholars, until very recently Canadian courts cited the decision to uphold restrictions on policy engagement by charities (Harvie Citation2002, 12; Biehler Citation2013; Parachin Citation2008). Canadian courts interpreted the spirit of the 1601 Charitable Uses Act and subsequent case law to include charitable purposes that promote widely-accepted public benefits, but not purposes or activities that question public benefits and how they can best be achieved (CRA Citation2003, Section 4). For example, the provision of medical assistance to the ill is an allowable charitable purpose, but advocacy to change policies to prevent disease and physical injury is not.

However, Canadian charity law makes an important legal distinction between charitable “purposes” and charitable “activities” (CRA Citation2003, Citation2019). In the late 1980s, Canadian courts and later the CRA recognised that charitable purposes can sometimes be achieved most effectively through advocacy and allowed charitable organisations to engage in limited “political activities” aimed at changing laws and policies, with several key conditions. The CRA identified three sets of activities that relate to advocacy: partisan activities – which were and remain prohibited, “political activities” – which the CRA required to be “connected” and “subordinate” to a charity’s purpose, and charitable activities – which were and remain unrestricted. The definition and prohibition of partisan activities by charities is straightforward and generally uncontroversial. Charities cannot directly or indirectly support or criticise political parties, politicians or electoral candidates (CRA Citation2003, Citation2019). Until 2019, Canadian law allowed charities to engage in so-called non-partisan “political activities” as long as they were connected to the charity’s stated purposes and did not consume more than 10 per cent of the charity’s expenditures, with slightly higher limits for small organisations (CRA Citation2003). The CRA defined “political activities” as those that involved public communication with the goal of retaining, opposing or changing “the law, policy, or decision of any level of government in Canada or a foreign country” (CRA Citation2003). The specification of “public” communications is crucial, because efforts by charities to change government laws and policies that were not communicated publicly were not defined as “political” and were categorised as allowable charitable activities. This meant that charities could engage in extensive lobbying efforts to influence government decisions, unmonitored and unrestricted by the CRA. However, any communication to the public that involved a call to action to change government policies was deemed “political activity” and was subject to CRA audits and the 10 per cent spending limit. In addition to lobbying, allowable charitable activities also included awareness raising, public education, conducting and publishing policy research, and hosting all-candidates meetings on policy issues – as long as these activities did not include calls for public action (CRA Citation2003). In sum, charities were free to publicise their perspectives on public policy issues but restricted in their capacity to call on the public to take action on those issues.

The CRA policy on “political activities” thus distinguished between two forms of advocacy in Canada: public and private, also frequently referred to as “outsider” and “insider” advocacy (Freiler and Clutterbuck Citation2017, 187–189; Lang Citation2013). While advocacy that occurred privately with government officials was unrestricted, public advocacy was restricted, monitored, audited and ultimately discouraged. Many CSOs not only avoided public advocacy, but also came to understand the concept of advocacy itself primarily in terms of private efforts to influence governments, which they distinguished from political activism – which took place in public. For example, the senior leader of a CSO involved in efforts to influence Canadian foreign aid policies distinguished between “advocacy” – which she characterised as working with government officials to change policies – and “tilling the fields” which she described as public awareness raising and campaigning (Interview, February 17, 2017). While private forms of advocacy may be an effective tactic for policy change, the absence of public engagement has two important impacts. First, CSO encouragement for the public to engage in public policy debates is very weak. Second, public understandings of international development and global justice remain grounded in depoliticised perspectives in which charitable action does not include struggles for legal and policy change.

In late 2018 the federal Liberal government amended the Income Tax Act to remove all references to “political activities” and in January 2019 the CRA introduced new guidelines which allow charities to spend 100 per cent of their resources on what it calls “Public Policy Development and Dialogue Activities” (PPDDAS) (CRA Citation2019; Government of Canada Citation2018). These changes follow reforms that were already introduced in other countries operating within the English traditions of charity law, most notably England and Wales, Scotland, Australia and the United States (see McGregor-Lowndes and Wyatt Citation2017). The regulations on public policy engagement by charities had been debated in Canada since the 1970s, with multiple reports calling for legal reforms, but it was the Conservative Harper government’s crack-down on “political activities” by charities that finally triggered legal change. In the 2015 federal election campaign, the Liberal party committed to changing the laws to support public policy action by charities and after the election Prime Minister Trudeau included specific instructions in the Mandate Letter to the Minister of National Revenue (responsible for the CRA) to reform federal law and regulations “to allow charities to do their work on behalf of Canadians free from political harassment … with an understanding that charities make an important contribution to public debate and public policy” (Trudeau Citation2015, 2). In 2016 the federal government appointed a panel to carry out a national consultation on the rules for “political activities” by charities. The panel’s report made four recommendations to increase the scope for public advocacy by Canadian charities including a specific recommendation “to enable charities to fully participate in public policy dialogue and development” (Consultation Panel on the Political Activities of Charities Citation2017, 17).

In July 2018, in response to a constitutional challenge from the small charity Canada Without Poverty, Justice Morgan of the Ontario Superior Court ruled “unconstitutional” the provisions of the federal Income Tax Act that prevent registered charities from spending more than 10 per cent of their expenditures on “political activities” on the grounds that the Act restricts the constitutional right to freedom of expression (Beeby Citation2018). The federal government responded in September and October 2018 with proposed legal and regulatory changes, which resulted in substantial changes to the proposed legislation and CRA regulations. In December 2018, the federal Liberal government introduced amendments to the Income Tax Act to remove all restrictions on “political activities” by charities and to allow charities to engage in unlimited “public policy dialogue and development activities”, provided that they serve the charity’s official “charitable purposes” and are non-partisan (Government of Canada Citation2018, 50–51). Finally, in January 2019, the CRA issued new guidelines on “Public Policy Development and Dialogue Activities” (PPDDAs) by charities, which replace the previous guidelines on “political activities”. While the new guidelines were open for public consultation until April 23, 2019, it is unlikely that they will change substantially. The second paragraphs of the new CRA guidance clearly states:

As long as a charity’s PPDDAs are carried on in furtherance of its stated charitable purpose(s), the Income Tax Act places no limits on the amount of PPDDAs a charity can engage in. In this context, a charity may devote up to 100% of its total resources to PPDDAs that further its stated charitable purpose. (CRA Citation2019)

In this new legal context, the misleading concept of “political activities” no longer defines public policy advocacy in Canada. Charities will still need to demonstrate that they do not engage in partisan activities, but they will be free to engage in public policy activities that serve their charitable purposes, including calling on Canadians to pressure governments to change laws and policies and to provide funding to international partner organisations to do the same in their home countries. While these changes mark a sea-change in the legal environment for CSO public policy advocacy in Canada, as we argue further below, there are also powerful financial constraints on CSO public policy engagement. Now that the legal restrictions are gone, Canadian CSOs will need to grapple seriously with questions about how to finance public policy work and whether they are willing to take the risks associated with speaking out against government funders.

Why CSO advocacy matters

Gibbons (Citation2016) asserts that charities have a “moral imperative” to engage in policy advocacy. The core challenge, he argues, is that the primary benefits of policy advocacy by charities are public, diffuse and difficult to measure, while the primary risks – including the loss of government funding, CRA audits and the loss of charitable status – are borne by individual organisations and are easy to measure (2016). Nevertheless, Gibbons argues that both individual charities and the broader public benefit from advocacy through better public policy and a more engaged public sphere. The wealth of practical experience and close connections with groups that lack a voice in policy debates enables many charities to bring ideas and evidence that would otherwise not enter the policy-making process.

There are other important reasons for charities to engage in policy advocacy. First, the mission statements of many charities, particularly in the international development sector, highlight the goal of global justiceFootnote2 which implicitly requires advocacy to improve government laws and policies in Canada and globally (see Harvie Citation2002, 4). It is difficult to imagine a theory of social change in which the goals of global justice are achieved only through the delivery of projects without changes in laws and government policies. Evidence indicates that Canadian CSOs recognise the need for advocacy to achieve their mandates; in response to a 2016 survey conducted by the CCIC, 52 out of 66 (78%) organisational members indicated that they believed that “social justice and the well-being of poor and marginalised people in developing countries” requires changes in government laws and policies in Canada and in the global South (CCIC Citation2016).

Explicitly public forms of advocacy are important for public understandings of global poverty and injustice. Advocacy practitioners make persuasive arguments that private, insider advocacy is more effective at generating policy change because it does not embarrass or threaten the government (Sussman Citation2007; Steele Citation2017). However, from the perspective of public understandings of global poverty, the decisions to keep advocacy work quiet means that the “public face” of development work by charities consists almost entirely of service delivery projects to “help” people living in poverty, as this is the work that is primarily featured in CSO communications. When advocacy remains private, it also remains largely hidden from the public, thus fostering perceptions that the reduction of global poverty is primarily a matter of charitable “helping” and that legal and policy reform is neither relevant nor necessary.

The legal and political context for advocacy by charities in Canada

The pre-2019 legal framework will continue shaping activities of Canadian charities, despite changes in the 2019 federal regulations that allow unrestricted non-partisan public policy advocacy by charities. Much of the recent debate about advocacy by charitable organisations in Canada was sparked by the “advocacy chill” under the Conservative Harper government (2006–2015) (Kirby Citation2014; Toronto Star Citation2016). However, policy advocacy by charities in Canada was legally constrained for more than 100 years. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries English and Canadian courts established the “doctrine of political purposes” that put legal and policy advocacy outside the scope of allowable charitable purposes. The 1917 Bowman vs. Secular Society case in England – in which the presiding judge observed that “a trust [charity] for the attainment of political purposes has always been invalid” (cited in Parachin Citation2017, 38) – became the legal foundation for the conclusion by Canadian courts and the CRA that charities cannot pursue political purposes and for the CRA’s regulations that restricted “political activities” to 10 per cent of an organisation’s annual expenditures.

Contemporary efforts to reform the legal and regulatory framework for advocacy by charities began during the 1970s in the context of the Liberal government’s promises for a “just society” and federal funding increases for charitable organisations (Elson Citation2007, 59–87). Since then, charity and nonprofit sector leaders, academics, lawyers, Members of Parliament, and federal judges repeatedly called for reforms to the legislation and regulations on advocacy by charities. Every decade there were “eerily familiar” calls to modernise the definition of charity (Elson Citation2011, 62; Drache Citation2002; IMPACS Citation2002; Laforest Citation2013; Levasseur Citation2012; National Advisory Council on Voluntary Action. Citation1977; Watson Citation1985). As the federally appointed Consultation Panel on the Political Activities of Charities” asserted in its 2017 report, “problems with the legislative framework and its administration have left the [charitable] sector and its regulator stuck on a merry-go-round of consultation, clarification, and concern for nearly four decades” (Citation2017, 10).

At the same time, despite the CRA rules, some branches of the federal government at least tolerated advocacy by charities, including those that received state funding. As Laforest (Citation2011, 28) notes, through the 1970s and 1980s, “advocacy was considered a legitimate activity” by many federal agencies and many charities used core funding provided by the federal government to pay for advocacy work (Citation2011, 28). In this context, many international development charities ignored the formal regulations on “political activity” and engaged in public advocacy targeted at the federal government – including the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and the Department of Foreign Affairs (now Global Affairs Canada) (Ian Smillie and Brian Tomlinson, personal correspondence).

Following the 2006 federal election, the Conservative Harper government sought to restrain advocacy by Canadian charities in ways that many in the sector had not previously experienced (Kirby Citation2014). CBC reporter Brian Stewart wrote in 2010: “For decades, I have covered human rights and aid groups here and around the world and have never seen such a chill as what is happening now in our own country” (Stewart Citation2010). The Harper government used two main strategies to silence charitable organisations: funding cuts and heightened enforcement of CRA regulations. Within the international development sector, the government sent a clear message that it would not tolerate criticism by cutting most or all funding to several prominent organisations, including Kairos and Match International in 2009, and the CCIC in 2010 (Beeby Citation2014a; Stewart Citation2010). In 2012, the government increased the CRA budget by $13 millionFootnote3 to conduct sixty in-depth “political activities” audits of Canadian charities over four years (Beeby Citation2014b). While the Director General of the CRA Charities Directorate claimed that its selection criteria for the audits were entirely objective (Hawara Citation2014), a review of the organisations selected indicates a disproportionately large number of environmental, international development and human rights charities (Beeby Citation2014b; Kirby Citation2014). The fear of the audits – which were extremely time and resource intensive for many charities – in addition to the fear of losing charitable status was a powerful motive to refrain from any forms of policy engagement that might be perceived as “political activity”. Moreover, indications from the Conservative government that it was not interested in CSO perspectives no matter how they were voiced led many international development CSOs to withdraw from advocacy activities altogether, viewing them as both risky and ineffective.

The long-term context of legal, regulatory and political constraints on public policy advocacy shaped the operations and strategy of Canadian CSOs significantly. It shaped their decisions to disengage from public policy advocacy, and decisions about board member recruitment, fundraising, and human resource development. Most importantly, because public policy advocacy was legally-restricted and widely perceived as risky, CSOs hired few staff members to conduct policy research and advocacy and dedicated little attention to raising funds to pay for it. As of early 2019, the entire cohort of policy research and advocacy staff within CCIC member organisations is approximately 20 people, although there are others who occasionally engage in advocacy work away from their desks.

That said, actual changes to the ways Canadian charities engage with public policy issues will require more than just legal reform. They will also require changes in the policies and practices of charities themselves and changes in public attitudes towards charities. Even with a more enabling legal environment for policy advocacy, Canadian charities will need to overcome deeply rooted internal constraints that have developed through more than 40 years of regulatory limits and risk aversion. In the short term, policy advocacy will continue to face serious internal human resource limitations as Canadian charities do not have the staff to carry out extensive advocacy work. More importantly, the internal political culture and resource allocation decisions of charities will need to overcome the aversion towards advocacy that is engrained in decades of hiring decisions and nominations to boards of directors (Geller and Salamon Citation2009, 2; Lang Citation2013, 113). Relationships with individual donors and institutional funders will also need to change, as will the ways in which charities communicate with the public. Now that the legal framework has changed, charities will need to make difficult internal decisions about whether and how to increase their policy advocacy work. These changes are not impossible and have been confronted by charities in other countries where charity laws have been reformed, such as the UK and Australia (McGregor-Lowndes and Wyatt Citation2017; International Center for Not-for-Profit Law Citation2009), but change will not be easy and many charities may choose not to pursue it (see Lang Citation2013). Moreover, other factors also limit the capacity of charities to engage in advocacy, most notably the lack of funding to support it from individual donors and philanthropic foundations as well as government.

Empirical evidence on CSO advocacy in Canada

Evidence suggests that relatively few Canadian international development CSOs engage in serious efforts to influence government policy and laws in Canada or to support efforts by partner organisations to influence legal and policy debates in their home countries. Canadian international development charities allocate few resources to advocacy work, despite recognising in principle that policy advocacy is crucial for the achievement of global justice. Evidence also supports the claims of an “advocacy chill” under the Harper government in terms of CRA-defined “political activities”, but only in the context of very low overall levels of policy engagement before and after the Harper “chill”. Canadian CSO leaders explain that they prefer to support coalition organisations to carry out advocacy on their behalf, partly to increase the effectiveness of advocacy efforts and partly as a risk aversion strategy, but the amounts of funding transferred to coalition organisations are very small. As a result, the efforts to influence public policy of most Canadian CSOs are not easily visible to the public and are generally disconnected from the efforts of the same organisations to engage Canadians with international development issues, creating an implicit message that advocacy for legal and policy change is not important for international development. The avoidance of policy advocacy cannot be explained simply in terms of the political and ideological orientation of charity leaders or their lack of moral courage, as some critics have argued (Barry-Shaw and Jay Citation2012). Rather, the legal, political, social and funding environment in which CSOs operate has shaped strategic decisions, often implicitly, to avoid engagement in policy advocacy. This trend exists among CSOs throughout the global North. As Lang observes in her analysis of CSO advocacy in the US, UK and Germany, “legal regulatory frameworks incentivise constraint and avoidance … [and] make public policy advocacy a potentially hazardous activity for NGOs” (2013, 103).

This section examines the publicly available data on CSO advocacy from three sources: (1) the CRA’s T-3010 information return form, which all charities must submit annually; (2) the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada’s registry of lobbying activity; and (3) a 2016 survey by the CCIC of its member organisations on the CRA’s rules for “political activities” by charities (CCIC Citation2016). Each data source provides only a partial view of the policy advocacy work of Canadian international development CSOs but examined together the data does provide a consistent quantitative picture. We have supplemented the numerical data with interviews with more than 50 staff members of 35 Canadian international development CSOs between 2014 and 2018 as well as three charity lawyers.

CRA data on “political activities” by charities

Canadian CSOs with charitable status are carefully monitored by the CRA and required to submit annual information returns on finances, staffing, fundraising, “political activities” and other aspects of their operations, which the CRA makes public on its website. The CRA is the most comprehensive single source of information on Canadian charities and provides data that charities do not typically include in their annual reports. Nonprofit CSOs without charitable status are regulated provincially, not by the CRA, and little data is available about them (Sharpe Citation2001, 13). Of the roughly 170,000 legally registered CSOs in Canada, approximately 85,000 are registered charities and the remainder are provincially registered nonprofit organisations (Imagine Canada Citationn.d.). Within the CCIC membership, which includes most of the medium and large international development CSOs in Canada, 58 out of 84 organisational members (69%) as well as the CCIC itself were registered as charities in 2017. As a result, the CRA data set does not include 26 CCIC member organisations with nonprofit status. Because these organisations are not required to submit information on their “political activities” they quite understandably do not collect it or make it available. Nevertheless, as we explain in the next section, the financial benefits of charity status in Canada mean both that almost all medium and large international development CSOs are registered as charities and that nonprofit CSOs typically have much smaller budgets. As a result, while nonprofits are free from the restrictions on “political activities”, with few exceptions they also lack the resources to invest in efforts to influence public policy.

It is important to note that the CRA data is prone to inaccuracies and must be interpreted with caution, particularly regarding “political activities”. The data submitted by charities is not independently verified by the CRA. CRA data prior to 1997 is inconsistent and incomplete, so we have chosen not to analyse it. Moreover, research indicates that many charitable organisations in Canada have under-reported or not reported their expenditures on “political activities” in the context of uncertainty and fear about the rules (Blumberg Citation2012; Imagine Canada Citation2010; Consultation Panel on the Rules for Political Activities by Charities Citation2017, 12). This article summarises CRA data for the period 1997–2016 that was provided to us by the CRA in response to an information request. The full data set and more detailed methodological notes are available on the website for this project (https://johndcameron.com/advocacy-lab/).

How many CCIC charities report “political activities”?

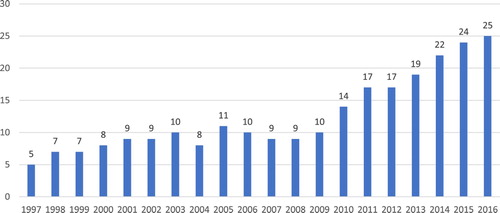

CRA data indicates that the number of CCIC member charities that report “political activity” to the CRA increased significantly from five in 1997–25 in 2016, representing just under one third of the CCIC’s membership (see ). The growth in the number of organisations likely indicates increased rates of reporting more than increased levels of “political activity”, particularly following the expanded efforts of the CRA to inform Canadian charities of the rules on “political activities” after 2003 and the increased funding for “political activities” audits provided by the Harper government in 2012.

How much do CCIC charities invest in “political activities”?

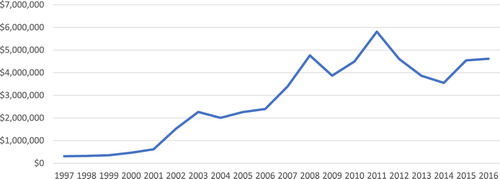

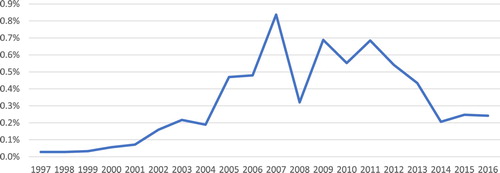

CRA data indicates a steady increase in spending on “political activities” by CCIC charities from a total of less than $500,000 in 1997 to a high of $5.8 million in 2011, followed by a decline to $3.5 million in 2014 and cautious growth back to $4.6 million in 2016 (see ). These dollar amounts represent a tiny percentage of the total expenditures of CCIC member charities (see ). Collectively, the highest level of spending by CCIC charities on “political activities” as a percentage of total expenditures was 0.83 per cent in 2007, which dropped to 0.20 per cent in 2014 and increased only slightly to 0.24 per cent in 2016. This means that as a group, CCIC charities could have increased their investments in “political activities” by more than 40 times in 2016 without exceeding the CRA’s 10 per cent limit. Nevertheless, while these figures may suggest a low commitment to “political activities”, CRA data for 2016 indicates that CCIC charities invested more than twenty times the proportion of resources in “political activities” than Canadian charities as a whole, which spent an average of 0.009 per cent of expenditures on “political activities” in 2016 (see Figure A1 in this article’s online Appendix).

Figure 2. Total expenditures of CCIC charities on political activities, CAD, 1997–2016. Source: Data provided by the Canada Revenue Agency, figure elaborated by the authors.

Figure 3. Expenditures of CCIC charities on political activities, as percentage of total expenditures, 1997–2016. Source: Data provided by the Canada Revenue Agency, figure elaborated by the authors.

The levels of investment in “political activities” by the CCIC charities that report them typically hover around 1 per cent of total expenditures. Significantly, during the first three of the four years in which the CRA conducted special “political activities” audits (2012–2016), the highest proportion of total expenditures on “political activities” reported by any CCIC charity was 4.45 per cent, less than half of the legal limit of 10 per cent. The anomaly in this pattern was Engineers Without Borders, which substantially increased its reported spending on “political activities” to 8.13 per cent of total expenditures in 2015 and 7.62 per cent in 2016. This data suggests that the CRA’s 10 per cent cap is not what inhibited investments by charities in “political activities”. The question is, what other factors do influence the low spending on “political activities” by Canadian charities.

How often do CCIC charities engage in public policy advocacy?

In the fall of 2016 the CCIC surveyed its member organisations to collect data to present to the federally appointed Consultation Panel on the Political Activities of Charities. Of the 66 organisations that responded to the survey 52 (78%) affirmed that social justice and improvements in the well-being of poor and marginalised people require legal and policy changes in both Canada and the Global South. However, only 21 out of 70 organisations (30%) actually reported any “political activities” to the CRA and just 47 per cent reported support for coalitions that engage in “political activities” (CCIC Citation2016), suggesting a misalignment between organisational values and activities.

The CCIC survey data generally corroborates our analysis of the CRA data on “political activities” but also adds valuable insights on the other efforts by international development CSOs to advocate policy change that fit within the CRA’s category of allowable charitable activities (see ). Over two-thirds of CCIC charities engaged in some form of public policy work, such as conducting and publishing policy-related research, which the CRA considered to be a legitimate charitable activity. Far fewer reported engaging in policy work on a monthly or more frequent basis. Notably, 31 out of 70 organisations indicated that they never “encourage the public to contact government representatives” (CCIC Citation2016, 13). The CCIC data points to a similar conclusion as the CRA data on “political activities”: there are 20–25 international development charities in Canada that invest in public policy advocacy, about ten of which invest more than 1 per cent of total expenditures in CRA-defined “political activities” and engage in policy advocacy on a regular basis (monthly or weekly).

Table 1. Frequency of international development CSO activities to influence public policy in Canada.

How often do Canadian international development charities lobby the Canadian government?

The Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada has collected data on the lobbying activities of Canadian businesses and CSOs since 2008 (Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada Citation2009, 2). As with the CRA data, the data from the Commissioner of Lobbying provides only a partial picture of efforts by Canadian CSOs to influence federal policy. The Federal Lobbying Act does not require organisations to register communications with government officials unless “the cumulative lobbying activities of all employees … constitute 20% or more of one person’s duties over a period of a month” (Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying. Citationn.d.: “Ten Things”). Given the relatively low number of communication reports submitted by CCIC member organisations, few would be legally required to report their lobbying activities. However, registration with the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying is understood to be a good practice by organisations that seek to influence federal decision-making – and so provides some indication of the organisations that view public policy engagement as an important part of their activities.Footnote4 Figure A2 (online Appendix) indicates that since 2011 between 19 and 22 international development CSOs reported lobby activities to the Commissioner of Lobbying each year, but that fewer than 10 lobbied the government on a regular basis (more than 20 times per year). The data for 2016 points toward a modest increase in both the total number of organisations reporting to the Commissioner of Lobbying and the number of lobbying reports that they submitted, suggesting a possible pattern towards increased lobbying by Canadian international development CSOs under the Liberal government. Nevertheless, the data on lobbying reinforces the general conclusions that can be drawn from the CRA data and the CCIC survey: most national-level international development organisations in Canada do not engage in public policy advocacy in a substantive way and only a handful of organisations make serious investments in public policy work. Viewed in comparison with the lobby activities of all CSOs in Canada, however, CCIC organisations are much more active. For example, in 2016 out of the total of 540 Canadian CSOs that registered lobby reports, 22 of them (4%) were CCIC member organisations (Figure A2).

The political economy of public policy advocacy in Canada

In additional to the regulatory constraints on advocacy, both charitable and nonprofit organisations in Canada face serious challenges in financing advocacy work. As a staff member responsible for policy research and advocacy in one large CSO stated with frustration, advocacy work “is not funded” (Interview, 06/12/16). For most international development CSOs in Canada, funding comes from a mix of three sources: federal government grants and project agreements, charitable contributions from individual donors and grants from private Canadian philanthropic foundations. A few organisations also receive project funding from international philanthropic foundations– such as the Gates Foundation – and a very small number generate funds through social enterprises or other profit-generation activities, but they are exceptions. None of the three primary sources of CSO funding in Canada is supportive of policy advocacy work. As Lang explains in her global analysis of CSO advocacy, “governments and foundations as well as many private donors do not like to fund it” (Citation2013, 132; see also Burrowes and Laforest Citation2017).

Since the 1960s many Canadian international development CSOs have become heavily dependent on federal funding for significant proportions of their revenue (Broadhead, Herbert-Copley, and Lambert Citation1988, 64–70; Munro Citation2015). As Ian Smillie (Citation2012) noted aptly, very few organisations are willing to take the risk of biting the hand that feeds them (see also Harvie Citation2002, 8; Hulme and Edwards Citation1997), particularly after CIDA made significant or total funding cuts to several prominent CSOs under the Harper government in 2009 and 2010. Moreover, for over two decades, very little federal funding has been available that could be used to support advocacy. Until 1995, CIDA funding rules allowed CSOs to spend up to 10% of project funding on “public engagement” work in Canada, which some organisations stretched to include advocacy, but since then there has been no stand-alone source of federal funding to support policy research, public engagement or advocacy by CSOs. Moreover, federal government project grants and contribution agreements typically allow for maximum expenditures on overhead expenses of 12 per cent. For most CSOs, this amount is insufficient to cover their basic administrative expenses (Smillie Citation2017, 115), let alone draw from government overhead funds to pay for policy research and advocacy work.

Individual charitable donations do not represent a panacea for funding advocacy either. First, all charitable and nonprofit organisations face heavy self-imposed pressure to keep their overhead expenses as low as possible. In the context of prevalent public perceptions that organisational effectiveness equates with low administrative costs, it can be challenging for proponents within CSOs to make the case to allocate resources to advocacy and thus to increase overhead spending. Most CSOs also feel a strong self-imposed pressure to be at least relatively transparent in using donor funds for the purposes advertised in fundraising appeals. Since most charitable fundraising focuses on projects in the global South, some CSOs feel that they cannot divert funds to advocacy campaigns in Canada (Interview, 07/12/16). CSO leaders also emphasise that it is very difficult to raise funds for advocacy from individual donors, who – CSOs perceive – prefer to contribute to poverty reduction projects in the Global South that have short-term measurable impacts. As one advocacy officer explained, “It’s really hard to make [advocacy] seem interesting and immediate to donors. Policy changes can take decades and most people won’t give money for hypothetical wins that are decades down the road” (Interview, 24/01/18). The relatively small budgets of the Canadian CSOs that do focus on policy research and advocacy provides further evidence of the challenges across the political spectrum of funding this work.Footnote5

The legal restrictions on “political activities” by charities in Canada also meant that many organisations with “political” purposes of potential benefit to the public (such as poverty relief, health and safety, environmental policy change) have not qualified for charitable status or have simply chosen not to apply for it, and so have not been able to issue tax receipts as an incentive to attract donations. While nonprofits are free of all the regulations that inhibit charities from engaging in advocacy, with only a few exceptions such as Greenpeace, they have proven unable to generate significant funds to invest in advocacy and to engage the Canadian public in advocacy efforts. Typically, advocacy organisations in Canada have few staff members and little money to pursue their goals. Organisations such as Change.org and Avaaz do provide low-cost mechanisms to generate petitions on policy issues, but they do not provide funding for research or for sustained advocacy campaigns. Those organisations that do get involved tend to engage primarily in private forms of “institutional” advocacy that relies on expert knowledge of government relations rather than popular mobilisation and that focuses on highly pragmatic, specific winnable issues rather than long-term principled struggles based on values for social justice and human rights (Burrowes and Laforest Citation2017; Freiler and Clutterbuck Citation2017; Lang Citation2013; Mulé and DeSantis Citation2017).

Conclusion

The legal, regulatory and funding environment for public policy advocacy by CSOs in Canada has been highly constrained for many decades. As a result of those constraints combined with the fear that criticising government policy might jeopardise the government funding on which many charitable organisations rely, Canadian CSOs invest very few resources in public policy advocacy. Moreover, the small number of organisations that do invest in advocacy reflect a trend towards private forms of insider or institutional advocacy rather than public forms of advocacy that engage Canadian citizens, a trend also observed in other countries of the global North (Lang Citation2013). While the insider advocacy strategies may be more effective to achieve specific public policy “wins”, they also fail to engage Canadians in public policy debates and to challenge popular perceptions that international development simply requires more charity and not also social and political struggle. Decades of restrictive laws and policies have fostered an organisational culture of risk aversion towards advocacy within many CSOs.

Now that the federal regulations have changed, CSOs will need to decide whether and how to expand their involvement in public policy debates. They will also need to find new ways to engage Canadians with public policy issues that relate to international development and global justice, and to generate financial support to expand the public policy work that is essential to fulfilling their mandates to reduce poverty, protect human rights and promote global social justice.

Online appendix

Download PDF (196.2 KB)Notes on contributors

John D. Cameron is Associate Professor in the Department of International Development Studies at Dalhousie University. His research focuses on struggles over Indigenous autonomy in Bolivia, representations of global poverty in NGO marketing, cosmopolitan ethics and advocacy by international development civil society organisations (see https://johndcameron.com/).

Olivia Kwiecien is a student in the MA programme in International Development Studies at Dalhousie University. Her MA thesis examines the tensions between effectiveness and ethics in the communications and marketing strategies of Canadian international development non-governmental organisations.

ORCID

John D. Cameron http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3389-9732

Olivia Kwiecien http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7949-7969

Notes

1 The Commissioners for the Special Purposes of Income Tax v Pemsel AC 531 [1891].

2 A review of the mission statements of the 87 organisational members of the Canadian Council for International Cooperation (CCIC) indicates that 60 of them include the following among their goals: global justice, justice, social justice, ending poverty, achieving sustainable development, human rights.

3 All dollar figures in this article refer to CAD.

4 The full data set on CCIC member reports to the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying for 2008–2016 as well as more detailed analysis of methodological considerations on the use of the data are available on the research website for this project (https://johndcameron.com/advocacy-lab/).

5 The 2016 annual reports of seven of the largest public policy organisations in Canada present the following figures for total revenue: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives ($5.7 million); Council of Canadians ($4.7 million); C.D. Howe Institute ($6.2 million); Environmental Defense ($2.7 million); Fraser Institute ($10.8 million); Pembina Institute ($4.6 million); and Results Canada ($1.0 million).

References

- Barry-Shaw, Nikolas, and Dru Oja Jay. 2012. Paved with Good Intentions: Canada’s Development NGOs from Idealism to Imperialism. Halifax and Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing.

- Beeby, Dean. 2014a. “Canadian Charities Feel ‘Chill’ as Tax Audits Widen into Political Activities.” Toronto Star. July 10.

- Beeby, Dean. 2014b. “Timeline: Canada Revenue Agency’s Political-Activity Audits of Charities.” CBC News. August 5.

- Beeby, Dean. 2018. “CRA Loses Court Challenge to its Political-Activity Audits of Charities.” CBC News. July 17.

- Biehler, H. 2013. “The Political Purposes Exception – Is There a Future for a Doctrine Built on Foundations of Sand?” Trust Law International 29 (3): 97–113.

- Blumberg, Mark. 2012. “How Accurate Are the T3010 Charity Returns When It Comes to ‘Political Activities’?” Accessed May 23, 2019. https://www.canadiancharitylaw.ca/blog/how_accurate_are_the_t3010_registered_charity_information_returns/.

- Broadhead, Tim, Brent Herbert-Copley, and Anne-Marie Lambert. 1988. Bridges of Hope: Canadian Voluntary Agencies and the Third World. Ottawa: North-South Institute.

- Burrowes, Anna, and Rachel Laforest. 2017. “Advocates Anonymous: A Study of Advocacy Coalitions in Ontario.” In The Shifting Terrain: Non-profit policy Advocacy in Canada, edited by Nick Mulé, and Gloria DeSantis, 63–81. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Canadian Council for International Co-operation (CCIC). 2016. Modern Charities, Ancient Rules: Public Policy Activities and Canada’s Global Development Sector. Ottawa: CCIC.

- Carter, Terrance, and Ryan M. Prendergast. 2019. “PPDDA In, ‘Political Activities’ Out: CRA’s New Draft Guidance on PPDDA Open for Comment.” Charity and NFP Law Bulletin No. 438: 1-6. Accessed June 3, 2019. http://www.carters.ca/index.php?page_id=93.

- Consultation Panel on the Political Activities of Charities. 2017. Report of the Consultation Panel on the Political Activities of Charities. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

- CRA (Canada Revenue Agency). 2003. Political Activities. Policy Statement CPS-022. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

- CRA. 2006. Guidelines for Registering a Charity: Meeting the Public Benefit Test. Policy statement CPS-024. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

- CRA. 2013. How to Draft Purposes for Charitable Registration. Guidance CG-019. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

- CRA. 2019. Public Policy Dialogue and Development Activities by Charities. Guidance CG-027. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

- Drache, Arthur. 2002. “Hostage to History: The Canadian Struggle to Modernise the Meaning of Charity.” Third Sector Review 8 (1): 39–65.

- Elson, Peter. 2007. “A Short History of Voluntary Sector-Government Relations in Canada.” The Philanthropist 21 (1): 36–74.

- Elson, Peter. 2011. High Ideals and Noble Intentions: Voluntary Sector-Government Relations in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Freiler, Christa, and Peter Clutterbuck. 2017. “Poverty Free Ontario: Cross-Community Advocacy for Social Justice.” In The Shifting Terrain: Non-Profit Policy Advocacy in Canada, edited by Nick Mulé, and Gloria Desantis, 172–199. Montreal and Kingston: McGill Queen’s University Press.

- Geller, Stephanie, and Lester Salamon. 2009. Listening Post Project Roundtable on Nonprofit Advocacy and Lobbying. Communique No. 13. Washington, DC: John Hopkins Institute for Policy Studies.

- Gibbons, Roger. 2016. “The Moral Imperative for Policy Advocacy.” The Philanthropist. February 1.

- Government of Canada. 2018. “A second Act to implement certain provisions of the budget tabled in Parliament on February 27, 2018 and other measures.” SC 28, c 27. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

- Government of Canada. 2019. Bill C-86. A Second Act to Implement Certain Provisions of the Budget Tabled in Parliament on February 27, 2018 and Other Measures. December 13. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

- Harvie, Betsy. 2002. Regulation of Advocacy in the Voluntary Sector: Current Challenges and Some Responses. Voluntary Sector Initiative Report. Ottawa: Voluntary Sector Initiative.

- Hawara, Cathy. 2014. “The Importance of an Independent and Effective Charities Regulator in Canada.” Accessed May 23, 2019. http://www.cra-arc.gc.ca/chrts-gvng/chrts/bt/2014-lwsympsm-eng.html.

- Hulme, David, and Michael Edwards, eds. 1997. NGOs, States and Donors: Too Close for Comfort? New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Imagine Canada. n.d. Accessed May 23, 2019. “Sector Impact.” http://sectorsource.ca/research-and-impact/sector-impact.

- Imagine Canada. 2010. “Public Awareness and Policy Activity.” Sector Monitor 1 (3): 1–2.

- IMPACS (Institute for Media, Policy and Civil Society) and Canadian Centre for Philanthropy. 2002. Let Charities Speak: Report of the Charities and Advocacy Dialogue. Accessed June 3, 2019. https://www.charitycentral.ca/book/export/html/209.

- International Center for Not-for-Profit Law. 2009. “Political Activities of NGOs: International Law and Best Practices.” The International Journal of Not-for-Profit Law 12 (1), Accessed June 3, 2019. http://www.icnl.org/research/journal/vol12iss1/special_1.htm.

- Kirby, Gareth. 2014. “An Uncharitable Chill: A Critical Exploration of How Changes in Federal Policy and Political Climate are Affecting Advocacy-Oriented Charities.” MA Thesis, Royal Roads University.

- Laforest, Rachel. 2011. Voluntary Sector Organizations and the State: Building New Relations. Vancouver and Toronto: UBC Press.

- Laforest, Rachel. 2013. “Muddling through Government-Nonprofit Relations in Canada.” In Government-Nonprofit Relations in Times of Recession, edited by Rachel Laforest, 9–18. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Lang, Sabine. 2013. NGOs, Civil Society and the Public Sphere. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Levasseur, Karine. 2012. “In the Name of Charity: Institutional Support for and Resistance to Redefining the Meaning of Charity in Canada.” Canadian Public Administration 55 (2): 181–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-7121.2012.00214.x

- McGregor-Lowndes, Myles, and Bob Wyatt, eds. 2017. Regulating Charities: The Inside Story. London: Routledge.

- Mulé, Nick, and Gloria DeSantis, eds. 2017. The Shifting Terrain: Non-profit Policy Advocacy in Canada. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Munro, Lauchlan. 2015. “Getting (un)Comfortable: A 50-year Perspective on How Canada’s Development NGOs Got So Dependent on Federal Government Funding.” Paper presented to the Canadian Association of International Development Studies Annual Conference. Ottawa, June 3–5.

- National Advisory Council on Voluntary Action. 1977. People in Action: Report of the National Advisory Council on Voluntary Action to the Government of Canada. Ottawa: Secretary of State, Government of Canada.

- Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada. 2009. Annual Report 2008–2009. Accessed May 23, 2019. https://lobbycanada.gc.ca/eic/site/012.nsf/eng/h_00032.html.

- Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada. n.d. “Ten Things You Should Know About Lobbying: A Practical Guide for Federal Public Office Holders.” Accessed May 23, 2019. https://lobbycanada.gc.ca/eic/site/012.nsf/eng/00403.html.

- Parachin, Adam. 2008. “Distinguishing Charity and Politics: The Judicial Thinking behind the Doctrine of Political Purposes.” Alberta Law Review 45: 871–879.

- Parachin, Adam. 2017. “Shifting Legal Terrain: Legal and Regulatory Restrictions on Political Advocacy by Charities.” In The Shifting Terrain: Non-profit Policy Advocacy in Canada, edited by Nick Mulé and Gloria DeSantis, 33–62. The Shifting Terrain: Non-profit Policy Advocacy in Canada. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Sharpe, David. 2001. “The Canadian Charitable Sector: An Overview.” In Between State and Market: Essays on Charities Law and Policy in Canada, edited by Bruce Chapman, Jim Philips, and David Stevens, 13–50. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Smillie, Ian. 2012. “Tying up the Cow: CIDA, Advocacy and Public Engagement.” In Struggling for Aid Effectiveness: CIDA and Canadian Foreign Aid, edited by Stephen Brown, 269–286. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Smillie, Ian. 2017. “A Death on Chapel Street: Anatomy of an NGO Collapse.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies 38 (1): 111–124. doi: 10.1080/02255189.2016.1224970

- Steele, Graham. 2017. The Effective Citizen: How to Make Politicians Work for You. Halifax: Nimbus Publishing.

- Stewart, Brian. 2010. “Another Critical Group Feels Ottawa's Axe.” CBC News. July 23.

- Sussman, Amanda. 2007. The Art of the Possible: A Handbook for Political Activism. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

- Toronto Star. 2016. “Liberals Should Put an End to Harper’s Charity Chill [Editorial]” December 6.

- Trudeau, Justin. 2015. Minister of National Revenue Mandate Letter. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

- Voluntary Sector Task Force and Government of Canada. 1999. Working Together: A Government of Canada / Voluntary Sector Joint Initiative – Report of the Joint Tables. Ottawa: Voluntary Sector Task Force and Government of Canada.

- Watson, Rod. 1985. “Charity and the Canadian Income Tax: An Erratic History.” The Philanthropist 5 (1): 3–21.